The Synergistic Effects of Jasmonic Acid and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Enhancing the Herbicide Resistance of an Invasive Weed Sphagneticola trilobata

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test of Plant Tolerance to Herbicide

2.2. Field Sampling for AMF Diversity Response to Herbicide

2.3. Assessment of AMF Colonization

2.4. Analysis of AMF Diversity

2.5. Metabolomics Analysis of the Effect of AMF on the Growth of S. trilobata

2.6. Role of Jasmonate Acid and AMF in Enhancing Herbicide Resistance of S. trilobata

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

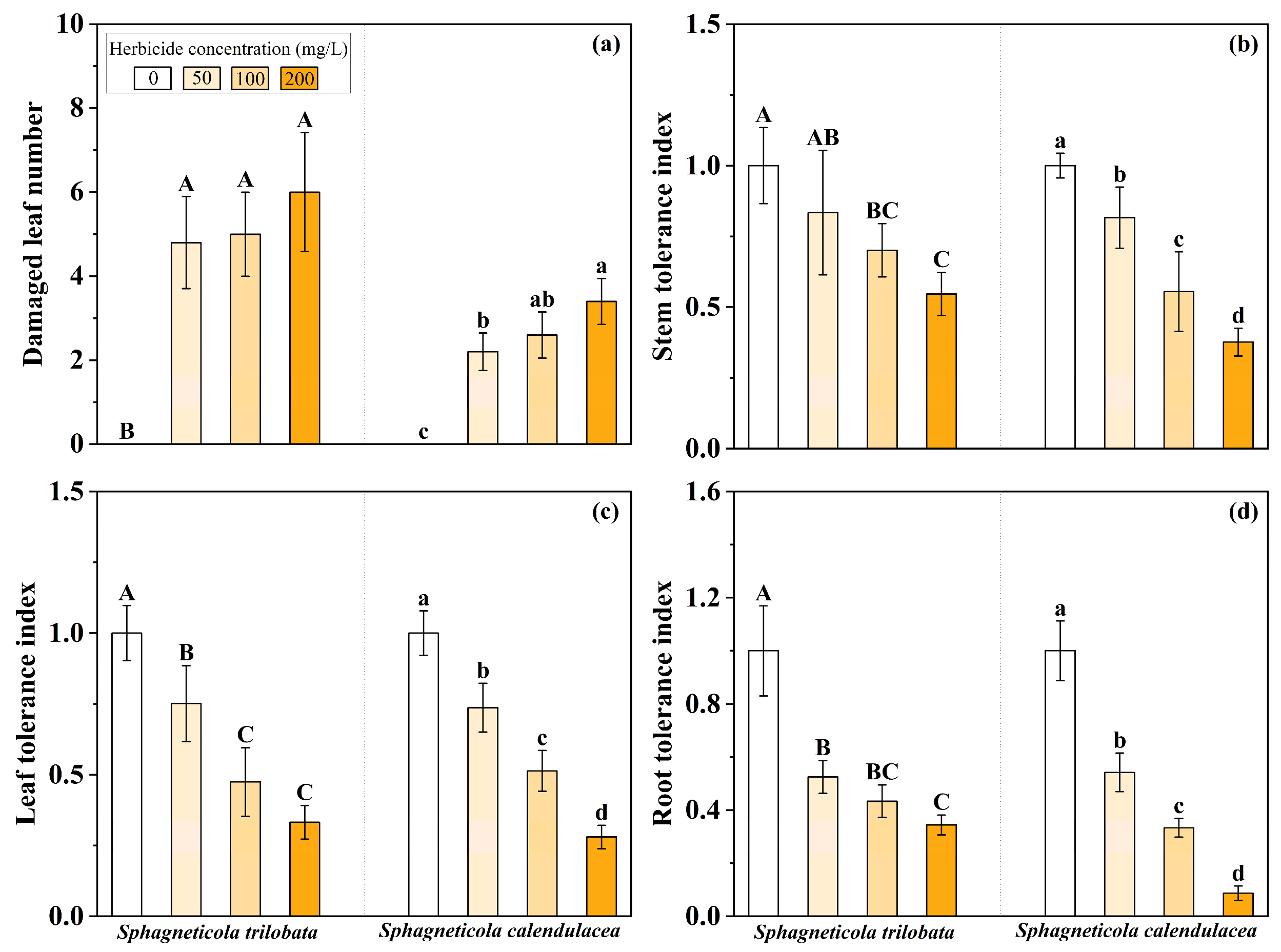

3.1. Plant Tolerance to Herbicide Concentration Gradients

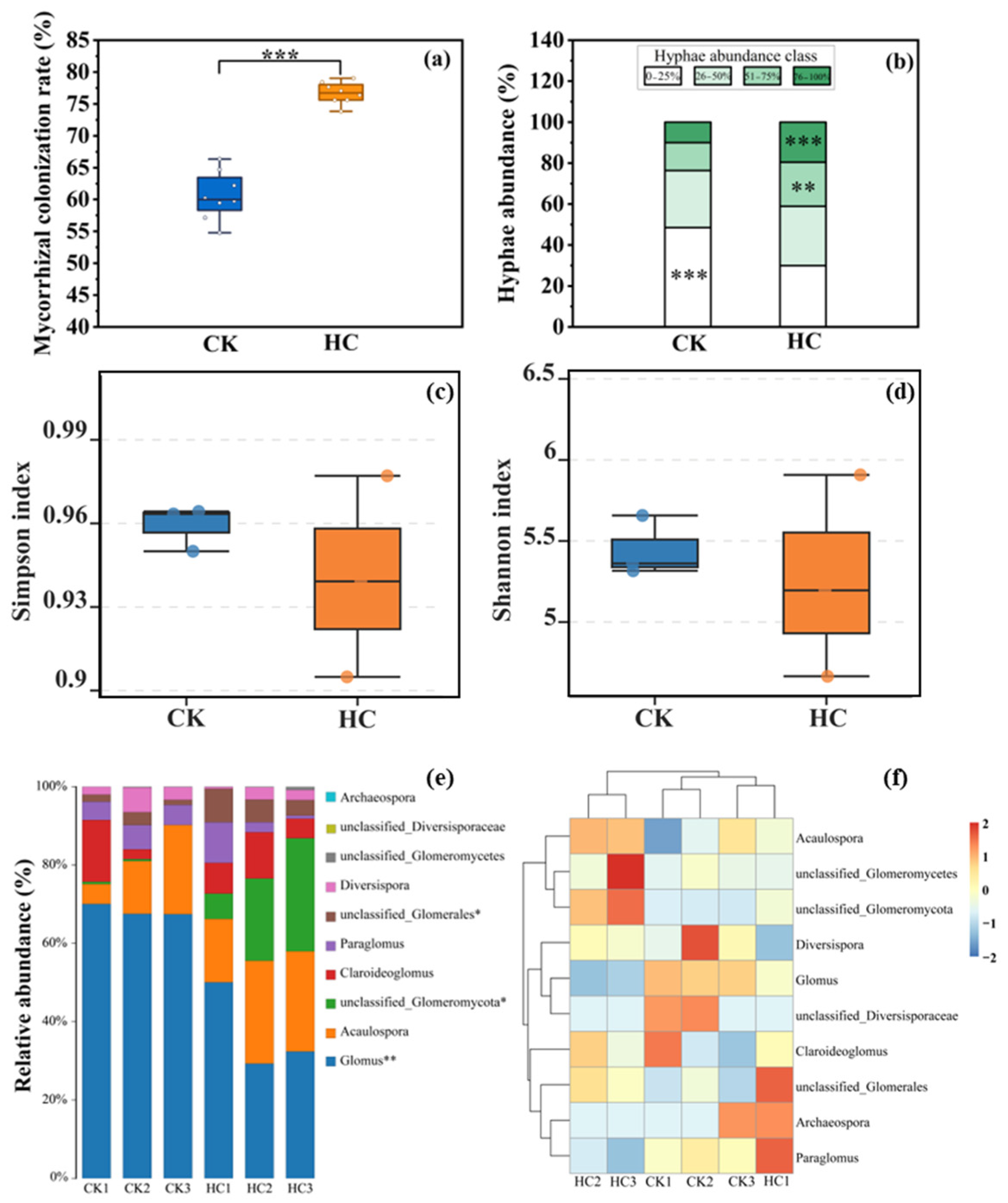

3.2. The Effects of Herbicide on the AMF Community of S. trilobata

3.3. Metabolomics Analysis of the Effects of AMF on S. trilobata

3.4. Effects of JA and AMF on the Growth of S. trilobata Under Herbicide Application

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of AMF in Plant Resistance to Herbicides

4.2. Role of JA and Its Interaction with AMF in Plant Resistance to Herbicides

4.3. Ecological Implications of AMF Symbiosis in Invasive Weed Resistance to Herbicide

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yadav, S.P.S.; Mehata, D.K.; Pokhrel, S.; Ghimire, N.P.; Gyawali, P.; Katel, S.; Timsina, U. Invasive alien plant species (Banmara): Investigating its invasive potential, ecological consequences on biodiversity, and management strategies. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Dai, Z.; Li, F.; Liu, Y. How will global environmental changes affect the growth of alien plants? Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Oduor, A.M.O.; Yan, Y.; Yu, W.; Chao, C.; Dong, L.; Jin, S.; Li, F. Nutrient enrichment, propagule pressure, and herbivory interactively influence the competitive ability of an invasive alien macrophyte Myriophyllum aquaticum. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1411767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebret, K.; Kritzberg, E.S.; Rengefors, K. Population genetic structure of a microalgal species under expansion. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez-Mir, G.C.; McCary, M.A. Invasive plants and their root traits are linked to the homogenization of soil microbial communities across the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2418632121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yu, H.; Yang, K.; Chen, L.; Yin, W.; Ding, J. Latitudinal and longitudinal trends of seed traits indicate adaptive strategies of an invasive plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 657813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngondya, I.B.; Treydte, A.C.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Munishi, L.K. Can Cynodon dactylon suppress the growth and development of the invasive weeds Tagetes minuta and Gutenbergia cordifolia? Plants 2019, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgal, G.; Kaur, J.; Chand, K.; Parashar, M.; Dhar, S.K.; Singh, G.B.; Gururani, M.A. Mitigating the mistletoe menace: Biotechnological and smart management approaches. Biology 2022, 11, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Lin, X.; Peng, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Huang, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, F.; Ding, W.; Peng, C. Why is the invasive plant Sphagneticola trilobata more resistant to high temperature than its native congener? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Weng, Z.; Chen, G.; Peng, C. Adaptation of the invasive plant Sphagneticola trilobata (L.) Pruski to drought stress. Plants 2024, 13, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Rutherford, S.; Saif Ullah, M.; Ullah, I.; Javed, Q.; Rasool, G.; Ajmal, M.; Azeem, A.; Nazir, M.J.; Du, D. Plant–soil feedback during biological invasions: Effect of litter decomposition from an invasive plant (Sphagneticola trilobata) on its native congener (S. calendulacea). J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, V.E.; Larran, A.S.; Palmieri, V.E.; Martinatto, A.K.; Permingeat, H.R. Herbicide resistant weeds: A call to integrate conventional agricultural practices, molecular biology knowledge and new technologies. Plant Sci. 2020, 290, 110255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, T.A.; Slavov, G.T.; Hughes, D.; Küpper, A.; Sparks, C.D.; Oliva, J.; Vila-Aiub, M.M.; Garcia, M.A.; Merotto, A., Jr; Neve, P. Investigating the origins and evolution of a glyphosate-resistant weed invasion in South America. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 5360–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.A.; Morgado, C.S.; Gomes, A.K.C.; Gomes, A.C.C.; Simas, N.K. Asteraceae family: A review of its allelopathic potential and the case of Acmella oleracea and Sphagneticola trilobata. Rodriguésia 2021, 72, e01622020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.R.; Naz, M.; Wan, J.; Dai, Z.; Ullah, R.; Rehman, S.U.; Du, D. Insights into the mechanisms involved in lead (Pb) tolerance in invasive plants—The current status of understanding. Plants 2023, 12, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Travlos, I.; Qi, L.; Kanatas, P.; Wang, P. Optimization of herbicide use: Study on spreading and evaporation characteristics of glyphosate-organic silicone mixture droplets on weed leaves. Agronomy 2019, 9, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Fan, F.; Tao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Yang, J. Creating a novel herbicide-tolerance OsALS allele using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. Crop J. 2021, 9, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, B.; Saikkonen, K.; Helander, M. Glyphosate-modulated biosynthesis driving plant defense and species interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.-S.; Manoharan, B.; Dhandapani, V.; Jegadeesan, S.; Rutherford, S.; Wan, J.S.; Huang, P.; Dai, Z.-C.; Du, D.-L. Pathogen resistance in Sphagneticola trilobata (Singapore daisy): Molecular associations and differentially expressed genes in response to disease from a widespread fungus. Genetica 2022, 150, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusthy, S.; Nizam, A.; Kumar, A. The diversity, drivers, consequences and management of plant invasions in the mangrove ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 173851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Brestic, M.; Bhadra, P.; Shankar, T.; Praharaj, S.; Palai, J.B.; Shah, M.M.R.; Barek, V.; Ondrisik, P.; Skalický, M. Bioinoculants—Natural biological resources for sustainable plant production. Microorganisms 2021, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.; Perveen, S.; Alamer, K.H.; Zia Ul Haq, M.; Rafique, Z.; Alsudays, I.M.; Althobaiti, A.T.; Saleh, M.A.; Hussain, S.; Attia, H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi symbiosis to enhance plant–soil interaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortas, I.; Rafique, M.; Çekiç, F. Do Mycorrhizal Fungi enable plants to cope with abiotic stresses by overcoming the detrimental effects of salinity and improving drought tolerance? In Symbiotic Soil Microorganisms. Soil Biology; Shrivastava, N., Mahajan, S., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Rabara, R.C.; Negi, S. AMF: The future prospect for sustainable agriculture. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 102, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Y.; Ye, M.; Li, C.Y.; Wang, R.L.; Wei, X.C.; Luo, S.M.; Zeng, R.S. Priming of anti-herbivore defense in tomato by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and involvement of the jasmonate pathway. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 39, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Song, F. Responses of nonenzymatic antioxidants to atrazine in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots of Medicago sativa L. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wu, W.W.; Qi, S.S.; Cheng, H.; Li, Q.; Ran, Q.; Dai, Z.C.; Du, D.L.; Egan, S.; Thomas, T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve the growth and disease resistance of the invasive plant Wedelia trilobata. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Gao, S.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, B.; Wang, Y. Exogenous methyl jasmonate promotes salt stress-induced growth inhibition and prioritizes defense response of Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, B.; Qi, S.-S.; Dhandapani, V.; Chen, Q.; Rutherford, S.; Wan, J.S.; Jegadeesan, S.; Yang, H.-Y.; Li, Q.; Li, J. Gene expression profiling reveals enhanced defense responses in an invasive weed compared to its native congener during pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, S.; Shukla, M.; Murch, S.; Bernier, L.; Saxena, P. Simultaneous induction of jasmonic acid and disease-responsive genes signifies tolerance of American elm to Dutch elm disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, E.; Breen, S. Interplay between phytohormone signalling pathways in plant defence–other than salicylic acid and jasmonic acid. Essays Biochem. 2022, 66, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-X.; J Ahammed, G.; Wu, C.; Fan, S.-y.; Zhou, Y.-H. Crosstalk among jasmonate, salicylate and ethylene signaling pathways in plant disease and immune responses. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2015, 16, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Shafi, Z.; Ilyas, T.; Singh, U.B.; Pichtel, J. Crosstalk between phytohormones and pesticides: Insights into unravelling the crucial roles of plant growth regulators in improving crop resilience to pesticide stress. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Malangisha, G.K.; Yang, H.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Mahmoud, A.; Khan, J.; Yang, J.; Hu, Z. Strigolactone alleviates herbicide toxicity via maintaining antioxidant homeostasis in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Agriculture 2021, 11, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zou, Y.-N.; Wu, Q.-S.; Kuča, K. Mycorrhiza-induced plant defence responses in trifoliate orange infected by Phytophthora parasitica. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2021, 43, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Lin, Z.; Ke, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, F.; Ru, D.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inhibit necrotrophic, but not biotrophic, aboveground plant pathogens: A meta-analysis and experimental study. New Phytol. 2024, 241, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, X.; Li, J.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Li, H.; Khashi u Rahman, M.; Du, M.; Wu, F.; Wei, Z.; Zhou, X.; et al. Common mycorrhizal networks facilitate plant disease resistance by altering rhizosphere microbiome assembly. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1765–1778.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhan, B.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y. JA signaling inhibitor JAZ is involved in regulation of AM symbiosis with Cassava, including symbiosis establishment and Cassava growth. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Suseela, V. Unraveling arbuscular mycorrhiza-induced changes in plant primary and secondary metabolome. Metabolites 2020, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, L.; Rasmann, S. Mycorrhizal fungi enhance resistance to herbivores in tomato plants with reduced jasmonic acid production. Agronomy 2019, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrín Dastis, J.O.; McGuinness, B.; Tadiri, C.P.; Yargeau, V.; Gonzalez, A. Connectivity mediates the spatial ecological impacts of a glyphosate-based herbicide in experimental metaecosystems. Oecologia 2024, 205, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, U.; Straube, G. Influence of substrate concentration on the induction of amidases in herbicide degradation. Z. Allg. Mikrobiol. 1984, 24, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Du, D. The invasive plant Amaranthus spinosus L. exhibits a stronger resistance to drought than the native plant A. tricolor L. under co-cultivation conditions when treated with light drought. Plants 2024, 13, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Jiang, X.; Dai, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, S.; Du, D. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance the capacity of invasive Sphagneticola trilobata to tolerate herbicides. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 48, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Wang, J.; Wan, L.; Dai, Z.; da Silva Matos, D.M.; Du, D.; Egan, S.; Bonser, S.P.; Thomas, T.; Moles, A.T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi contribute to phosphorous uptake and allocation strategies of Solidago canadensis in a phosphorous-deficient environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 831654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.; Chen, D.; Yan, M.; Huang, Z.; Yu, H.; Ren, G.; Xiong, H.a.; Fu, W.; Zhao, B.; Dai, Z.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance glyphosate resistance in an invasive weed: Implications for eco-environmental risks. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 212, 106203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geel, M.; Busschaert, P.; Honnay, O.; Lievens, B. Evaluation of six primer pairs targeting the nuclear rRNA operon for characterization of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal (AMF) communities using 454 pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. Methods 2014, 106, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, F.; Xia, W.K.; He, M.; Qi, S.S.; Dai, Z.C.; Du, D.L. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria alleviates competition between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Solidago canadensis for nutrients under nitrogen limitation. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2020, 44, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, N.; Boccard, J.; Lang, G.; Grömping, U.; Fischer, R.; Goepfert, S.; Rudaz, S.; Schillberg, S. Structured plant metabolomics for the simultaneous exploration of multiple factors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.J.; Van Loon, L.C.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Jasmonates—Signals in plant-microbe interactions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2004, 23, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, D.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Gao, W. Jasmonic acid and methyl dihydrojasmonate enhance saponin biosynthesis as well as expression of functional genes in adventitious roots of Panax notoginseng FH Chen. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2017, 64, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Zhu, C.; Xia, K.; Gan, L. Effects of methyl dihydrojasmonate on seedling growth and drought resistance in tall fescue. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2009, 32, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, B.; Ji, J.; Yu, L. Effects of methyl jasmonate and methyl dihydrojasmonate on the cell growth and flavonoids accumulation in cell suspension culture of Glycyrrhiza inflata Bat. Plant Physiol. J. 2008, 5, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Tian, M.; Tian, W.; Tian, W.; Li, J. Integrated analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveal the enhancement of methyl dihydrojasmonate on physiological indicators and polyphyllins biosynthesis in Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 4517–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Cheng, H.; Li, Q.; He, F.; Wu, W.; Qi, S.; Dai, Z.; Du, D. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi promote the growth of Wedelia trilobata under low phosphorus environment. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2020, 48, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, I.; Murmann, L.M.; Rosendahl, S. Hormetic responses in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 159, 108299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Benitez, S.; Navarro-Torre, S.; Caballero, P.; Martín, L.; Revilla, E.; Castaño, A.; Parrado, J. Biostimulant capacity of an enzymatic extract from rice bran against ozone-induced damage in Capsicum annum. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 749422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Kaur, N.; Vadhel, A.; Verma, A.K.; Girdhar, M.; Malik, T.; Kumar, A.; Mohan, A. Unravelling herbicide stress and its impact on metabolite profiling in Cannabis sativa: An investigative study. J. Cannabis Res. 2025, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Gu, Y.; Xiao, M.; Chen, J.; Li, B. The history of Solidago canadensis invasion and the development of its mycorrhizal associations in newly-reclaimed land. Funct. Plant Biol. 2004, 31, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Ortiz, P.; Tapia-Torres, Y.; Larsen, J.; García-Oliva, F. Glyphosate-based herbicides alter soil carbon and phosphorus dynamics and microbial activity. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 169, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, Y.; Shi, G.; Li, J.; Fan, G.; Yang, C.; Wang, B.; Tong, F.; Li, Y. Enhanced degradation of fomesafen by a rhizobial strain Sinorhizobium sp. W16 in symbiotic association with soybean. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 187, 104847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, F.; Tang, M. Transcriptome analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal Casuarina glauca in damage mitigation of roots on NaCl stress. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wei, H.; Chen, H.; Hu, W.; Tang, M. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the growth and root cell ultrastructure of Eucalyptus grandis under cadmium stress. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Fang, C.; Zhu, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, Z. Soil types create different rhizosphere ecosystems and profoundly affect the growth characteristics of ratoon sugarcane. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1541329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Zheng, M.; Dong, W.; Xu, P.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, W.; Luo, Y.; Guo, J.; Niu, D.; Yu, Y.; et al. Plant disease resistance-related pathways recruit beneficial bacteria by remodeling root exudates upon Bacillus cereus AR156 treatment. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03611-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, L. Root exudates and chemotactic strains mediate bacterial community assembly in the rhizosphere soil of Casuarina equisetifolia L. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 988442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.F.d.; Gomes, E.W.F.; Oliveira, J.P.; Fernandes, J.G.; Messias, A.S. Analysis of the atriplex subjected to Claroideoglomus etunicatum and to the desalinator reject. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaffari, W.; Boutasknit, A.; Anli, M.; Ait-El-Mokhtar, M.; Ait-Rahou, Y.; Ben-Laouane, R.; Ben Ahmed, H.; Mitsui, T.; Baslam, M.; Meddich, A. The native arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and vermicompost-based organic amendments enhance soil fertility, growth performance, and the drought stress tolerance of quinoa. Plants 2022, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhaddou, R.; Meddich, A.; Ikan, C.; Lahlali, R.; Ait Barka, E.; Hajirezaei, M.-R.; Duponnois, R.; Baslam, M. Enhancing maize productivity and soil health under salt stress through physiological adaptation and metabolic regulation using indigenous biostimulants. Plants 2023, 12, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chafai, W.; Gabardi, S.E.; Douira, A.; Khalid, A. Diversity and mycorrhizal potential of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in two natural soils in the eastern region of Morocco. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2022, 2, 202102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.; Santos-Villalobos, S.D.; Santoyo, G.; Babalola, O.O. Recent developments in the application of plant growth-promoting drought adaptive rhizobacteria for drought mitigation. Plants 2022, 11, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Rodríguez, A.; Rangseekaew, P.; Lasudee, K.; Pathom-aree, W.; Manzanera, M. Impacts of agriculture on the environment and soil microbial biodiversity. Plants 2021, 10, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degani, O.; Gordani, A.; Becher, P.; Chen, A.; Rabinovitz, O. Crop rotation and minimal tillage selectively affect maize growth promotion under late wilt disease stress. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, F.A.; Nafady, N.A.; Abdel-Wahab, D.A. The efficiency of arbuscular mycorrhiza in increasing tolerance of Triticum aestivum L. to alkaline stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Pan, L.; Zipori, I.; Mao, J.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Jing, Y.; Chen, H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhanced the growth, phosphorus uptake and Pht expression of olive (Olea europaea L.) plantlets. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, A.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Wirth, S.; Egamberdieva, D. Comparing symbiotic performance and physiological responses of two soybean cultivars to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under salt stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Long, S.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.-H.; Zhu, G.; Feng, B.; Qin, S.; et al. Dictyophora indusiata and Bacillus aryabhattai improve sugarcane yield by endogenously associating with the root and regulating flavonoid metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1326917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Su, Y.; Ye, C.; Zuo, D.; Wang, L.; Mei, X.; Deng, W.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Hao, J.; et al. Nucleotides enriched under heat stress recruit beneficial rhizomicrobes to protect plants from heat and root-rot stresses. Microbiome 2025, 13, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsheikh, E.A.E.; El-Keblawy, A.; Mosa, K.A.; Okoh, A.I.; Saadoun, I. Role of endophytes and rhizosphere microbes in promoting the invasion of exotic plants in arid and semi-arid areas: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Yan, J.; Zhou, M.; Yao, X.; Gao, A.; Ma, C.; Cheng, J.; Ruan, J. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as a biocontrol agent in the control of plant diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaffari, W.; Soussani, F.-E.; Boutasknit, A.; Toubali, S.; Hassine, A.B.; Ahmed, H.B.; Lahlali, R.; Meddich, A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve drought tolerance of quinoa grown in compost-amended soils by altering primary and secondary metabolite levels. Phyton Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 2285–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BÁRzana, G.; Aroca, R.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M. Localized and non-localized effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis on accumulation of osmolytes and aquaporins and on antioxidant systems in maize plants subjected to total or partial root drying. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1613–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; Chen, R.; Li, T.; Zou, B.; Geng, G.; Xu, Y.; Stevanato, P.; Yu, L.; Nurminsky, V.N.; Liu, J.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance tolerance to drought stress by altering the physiological and biochemical characteristics of sugar beet. Sugar Tech 2024, 26, 1377–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsis, J.A.; Boateng, G.G.; Seo, L.M.; Petersen, C.L.; Fortuna, K.L.; Wechsler, E.V.; Peterson, R.J.; Cook, S.B.; Pidgeon, D.; Dokko, R.S.; et al. Development and usability assessment of a connected resistance exercise band application for strength-monitoring. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 13, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Su, J.; Yang, T.; Liu, B.; Ma, B.; Ma, F.; Li, M.; Zhang, M. Transcriptomics and metabolomics reveal effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and development of apple plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1052464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Pei, Y.; Huang, W.; Ding, J.; Siemann, E. Increasing flavonoid concentrations in root exudates enhance associations between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and an invasive plant. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, L.; Fu, C.; Zhang, T.; Ding, W.; Yang, C. Genotype-environment interaction of crocin in Gardenia jasminoides by AMMI and GGE biplot analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 4080–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, T.M. Synthesis versus degradation: Directions of amino acid metabolism during Arabidopsis abiotic stress response. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018, 98, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragić, S.; Dahija, S.; Karalija, E. The good, the bad, and the epigenetic: Stress-induced metabolite regulation and transgenerational effects. Epigenomes 2025, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Sun, C.; Zhu, Z.; Deng, L.; Yu, F.; Xie, Q.; Li, C. A multiprotein regulatory module, MED16–MBR1&2, controls MED25 homeostasis during jasmonate signaling. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.; Doganlar, Z.B. Exogenous jasmonic acid induces stress tolerance in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) exposed to imazapic. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 124, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Xuan, X.; Xu, D.; Wen, Y. Mechanisms underlying allelopathic disturbance of herbicide imazethapyr on wheat and its neighboring ryegrass (Lolium perenne). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 3445–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J.; Peng, Q.; Yang, X.; Yang, Q.; Bai, L.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Zhang, Z.C.; Gu, T. Differences in exogenous methyl jasmonate-induced quinclorac resistance between resistant and sensitive barnyardgrass and the underlying mechanism. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 31, 2293–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cheng, L.; Long, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Pu, H.; Hu, M. Synergistic mutations of two rapeseed AHAS genes confer high resistance to sulfonylurea herbicides for weed control. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 2811–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinrücken, H.C.; Amrhein, N. The herbicide glyphosate is a potent inhibitor of 5-enolpyruvylshikimic acid-3-phosphate synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1980, 94, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinrücken, H.C.; Amrhein, N. 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase of Klebsiella pneumoniae. 1. Purification and properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984, 143, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.P.; Smedbol, E.; Chalifour, A.; Hénault-Ethier, L.; Labrecque, M.; Lepage, L.; Lucotte, M.; Juneau, P. Alteration of plant physiology by glyphosate and its by-product aminomethylphosphonic acid: An overview. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4691–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, J.; Dong, Y.; Kistler, H.C. Fusarium graminearum Tri12p influences virulence to wheat and trichothecene accumulation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25, 1408–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.-Y.; Hong, Y.-Q.; Chen, G.-H. Review on analysis methodology of phenoxy acid herbicide residues. Food Anal. Methods 2016, 9, 1532–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, M.; Jiang, P.; Zeng, L. Functioning mechanism of plant signal substances generated in mycorrhizal symbionts. J. Huaqiao Univ. Nat. Sci. 2012, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Guo, H.; Duan, G.; Wang, Z.; Fan, G.; Li, J. Role and mechanism of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in enhancing plant stress resistance and soil improvement: A review. China Powder Sci. Technol. 2024, 30, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowarah, B.; Gill, S.S.; Agarwala, N. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in conferring tolerance to biotic stresses in plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Xie, W.; Chen, B. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis affects plant immunity to viral infection and accumulation. Viruses 2019, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedini, A.; Mercy, L.; Schneider, C.; Franken, P.; Lucic-Mercy, E. Unraveling the initial plant hormone signaling, metabolic mechanisms and plant defense triggering the endomycorrhizal symbiosis behavior. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, S.; Biswal, B.; Bhakuni, K.; Ali, G.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Yadav, M.R.; Kumar, R. Chapter 20—Amelioration of abiotic stresses in forage crop production using microbial stimulants: An overview. In Microbial Biostimulants for Plant Growth and Abiotic Stress Amelioration; Chauhan, P.S., Bisht, N., Agarwal, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 397–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Lin, R.; Tan, M.; Yan, J.; Yan, S. The mycorrhizal-induced growth promotion and insect resistance reduction in Populus alba × P. berolinensis seedlings: A multi-omics study. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Mostofa, M.G.; Keya, S.S.; Ghosh, P.K.; Abdelrahman, M.; Anik, T.R.; Gupta, A.; Tran, L.-S.P. Jasmonic acid priming augments antioxidant defense and photosynthesis in soybean to alleviate combined heat and drought stress effects. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Liu, X.-Y.; Jiang, S.-Y.; Guo, S.-X.; Wang, J.-F.; Hu, Y.; Li, S.-M.; Li, H.-M.; Wang, T.; Sun, Y.-K.; et al. Allelopathy and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi interactions shape plant invasion outcomes. NeoBiota 2023, 89, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwampashi, L.L.; Magubika, A.J.; Ringo, J.F.; Theonest, D.J.; Tryphone, G.M.; Chilagane, L.A.; Nassary, E.K. Exploring agro-ecological significance, knowledge gaps, and research priorities in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1491861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Swarupa, P.; Kesari, K.K.; Kumar, A. Microbial inoculants as plant biostimulants: A review on risk status. Life 2022, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liao, X.; Yan, Q.; Xie, Y.; Chen, J.; Liang, G.; Chen, M.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve the growth, water status, and nutrient uptake of Cinnamomum migao and the soil nutrient stoichiometry under drought stress and recovery. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Liu, P.; Wu, A.; Dong, L.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, M.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y. Resistance of mycorrhizal Cinnamomum camphora seedlings to salt spray depends on K+ and P uptake. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Gao, Y.; Han, L.; Chu, H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi contribute to reactive oxygen species homeostasis of Bombax ceiba L. under drought stress. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 991781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Siemann, E.; Tian, B.; Ding, J. Root flavonoids are related to enhanced AMF colonization of an invasive tree. AoB Plants 2020, 12, plaa002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, R.; Wan, F.; Li, M. Functions and mechanisms of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in succession of exotic invasive plants. Plant Physiol. J. 2013, 49, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Du, E.; Meng, Y.; Sang, X.; Zhang, F. Effects of invasive plants interacting with native plants on colonization of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycosystema 2019, 38, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujvári, G.; Turrini, A.; Avio, L.; Agnolucci, M. Possible role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and associated bacteria in the recruitment of endophytic bacterial communities by plant roots. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Panneerselvam, P.; Chidambaranathan, P.; Nayak, A.K.; Priyadarshini, A.; Senapati, A.; Mohapatra, P.K.D. Strigolactone GR24-mediated mitigation of phosphorus deficiency through mycorrhization in aerobic rice. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 6, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Long, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Pu, H.; Hu, M. Development and molecular analysis of a novel acetohydroxyacid synthase rapeseed mutant with high resistance to sulfonylurea herbicides. Crop J. 2022, 10, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Rehman, T.; Young, J.; Johnson, W.G.; Yokoo, T.; Young, B.; Jin, J. Hyperspectral analysis for discriminating herbicide site of action: A novel approach for accelerating herbicide research. Sensors 2023, 23, 9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Beres, Z.T.; Jin, L.; Parrish, J.T.; Zhao, W.; Mackey, D.; Snow, A.A. Effects of over-expressing a native gene encoding 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) on glyphosate resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, H.; Naz, M.; Chen, R.; Yan, M.; Gong, Z.; Shu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ren, G.; Qi, S.; Dai, Z.; et al. The Synergistic Effects of Jasmonic Acid and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Enhancing the Herbicide Resistance of an Invasive Weed Sphagneticola trilobata. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122817

Xiong H, Naz M, Chen R, Yan M, Gong Z, Shu Z, Zhang R, Ren G, Qi S, Dai Z, et al. The Synergistic Effects of Jasmonic Acid and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Enhancing the Herbicide Resistance of an Invasive Weed Sphagneticola trilobata. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122817

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Hu’anhe, Misbah Naz, Rui Chen, Mengting Yan, Zongzhi Gong, Zhixiang Shu, Ruike Zhang, Guangqian Ren, Shanshan Qi, Zhicong Dai, and et al. 2025. "The Synergistic Effects of Jasmonic Acid and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Enhancing the Herbicide Resistance of an Invasive Weed Sphagneticola trilobata" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122817

APA StyleXiong, H., Naz, M., Chen, R., Yan, M., Gong, Z., Shu, Z., Zhang, R., Ren, G., Qi, S., Dai, Z., & Du, D. (2025). The Synergistic Effects of Jasmonic Acid and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Enhancing the Herbicide Resistance of an Invasive Weed Sphagneticola trilobata. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122817