Nutrient State-Dependent Ascarosides and Nematode Immune Response Limit the Predation of Arthrobotrys oligospora

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains

2.2. Worm Starvation Treatment

2.3. Predation Assay

2.4. Relative Quantitative Analysis of Ascarosides in Worms

2.5. RNA Interference

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Survival Assays

2.8. Fluorescence Microscopic Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

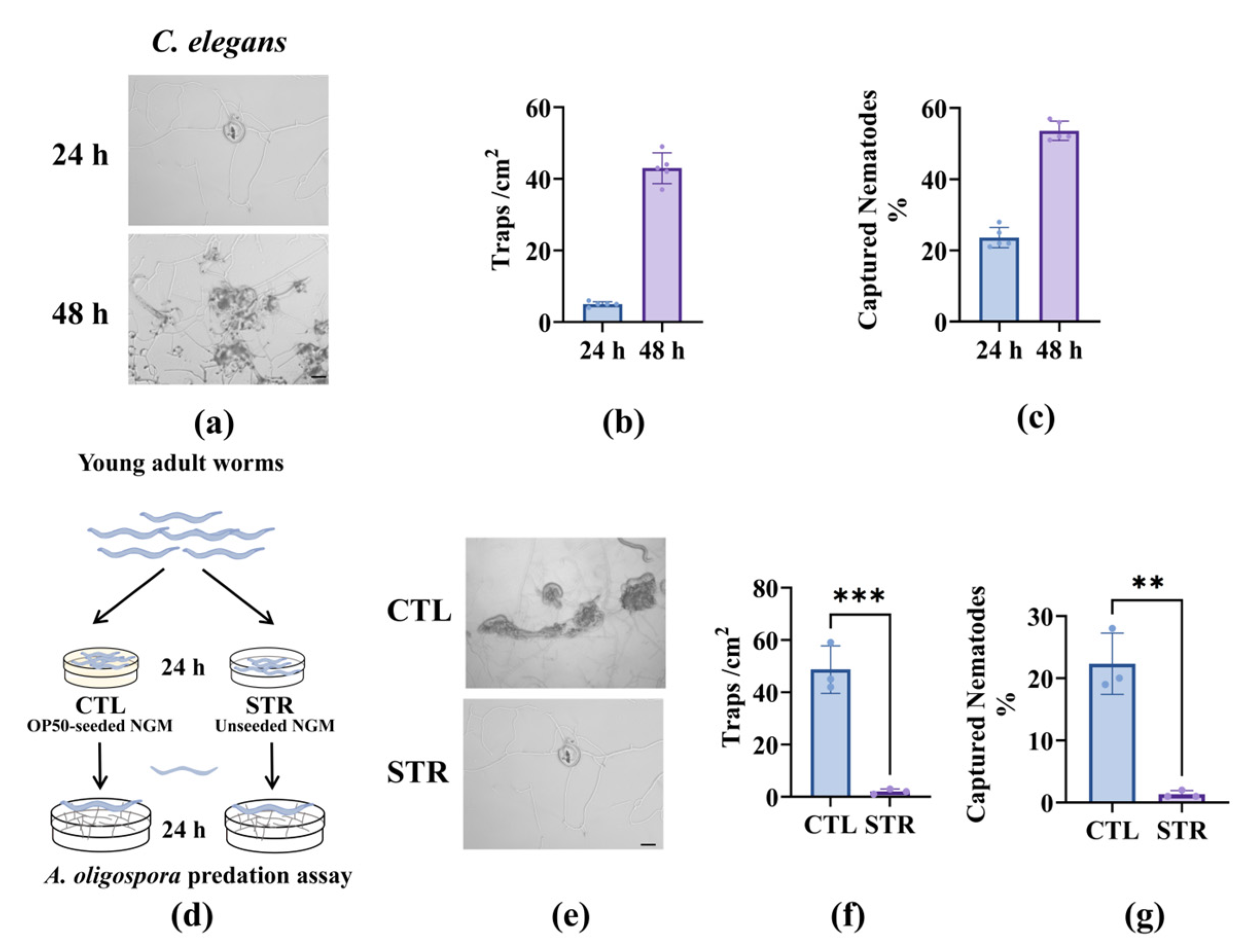

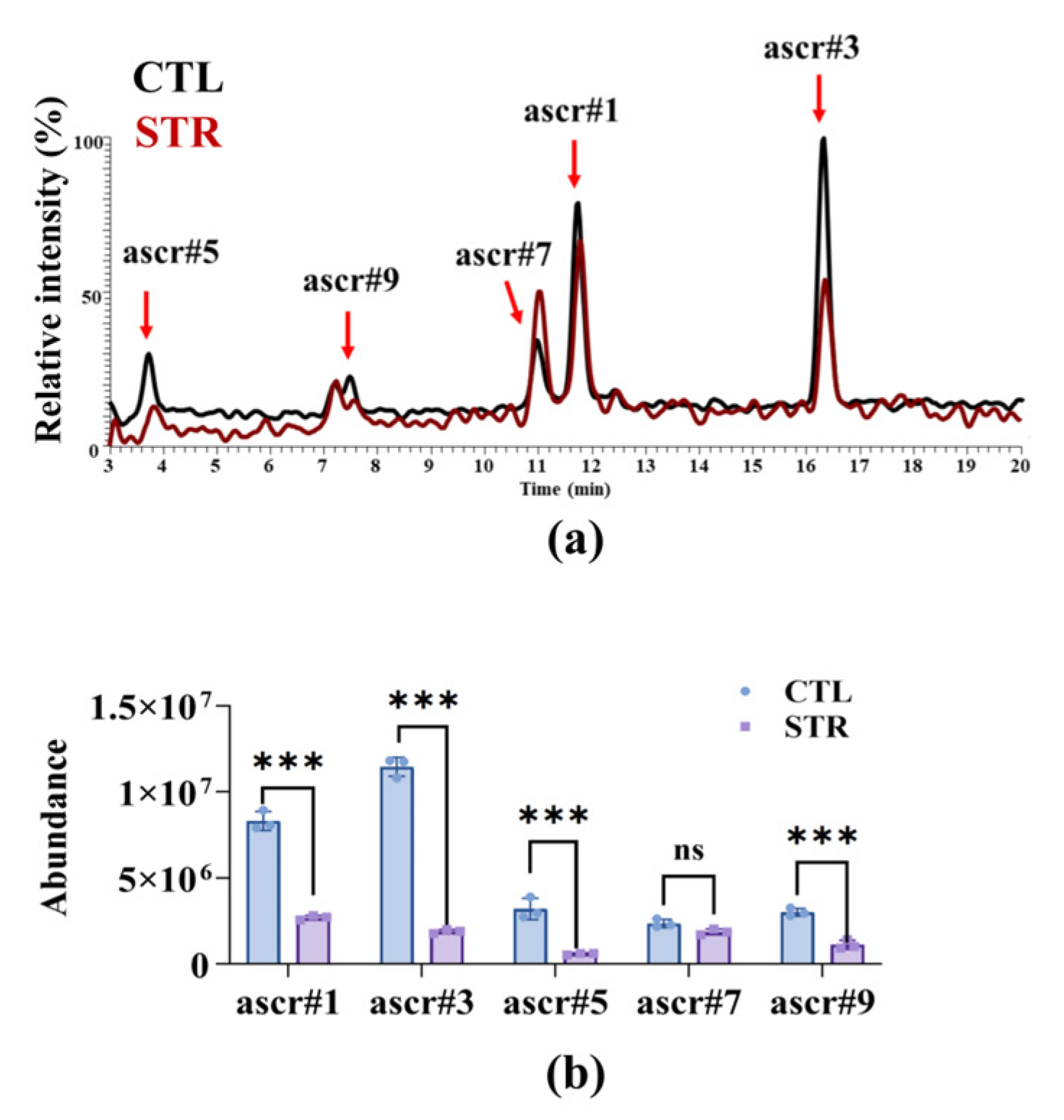

3.1. Starvation-Induced Ascaroside Reduction in Nematodes Impairs A. oligospora Predation

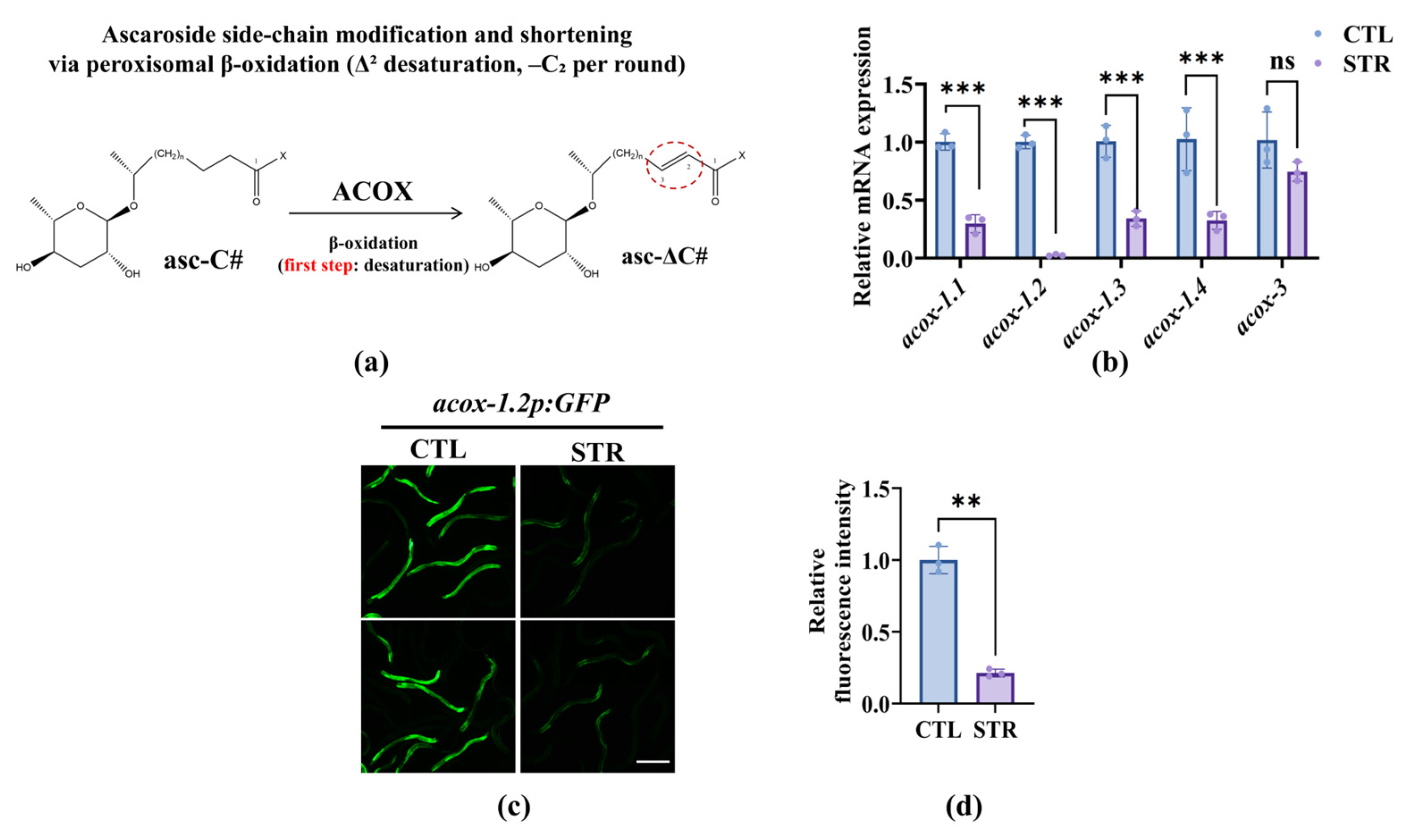

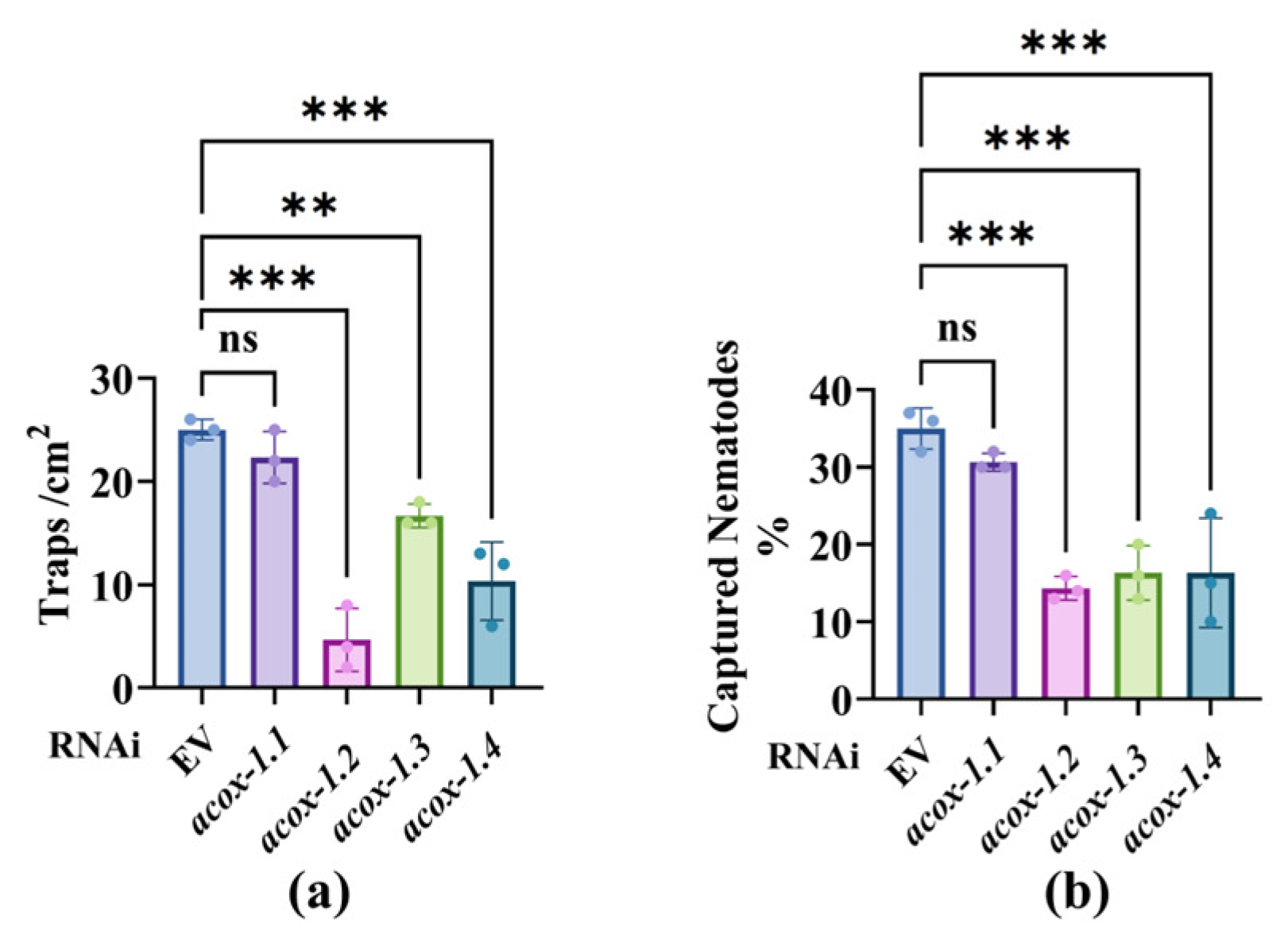

3.2. Starvation Downregulation of the ACOX Genes in Nematodes Reduces the Predation Efficiency of A. oligospora

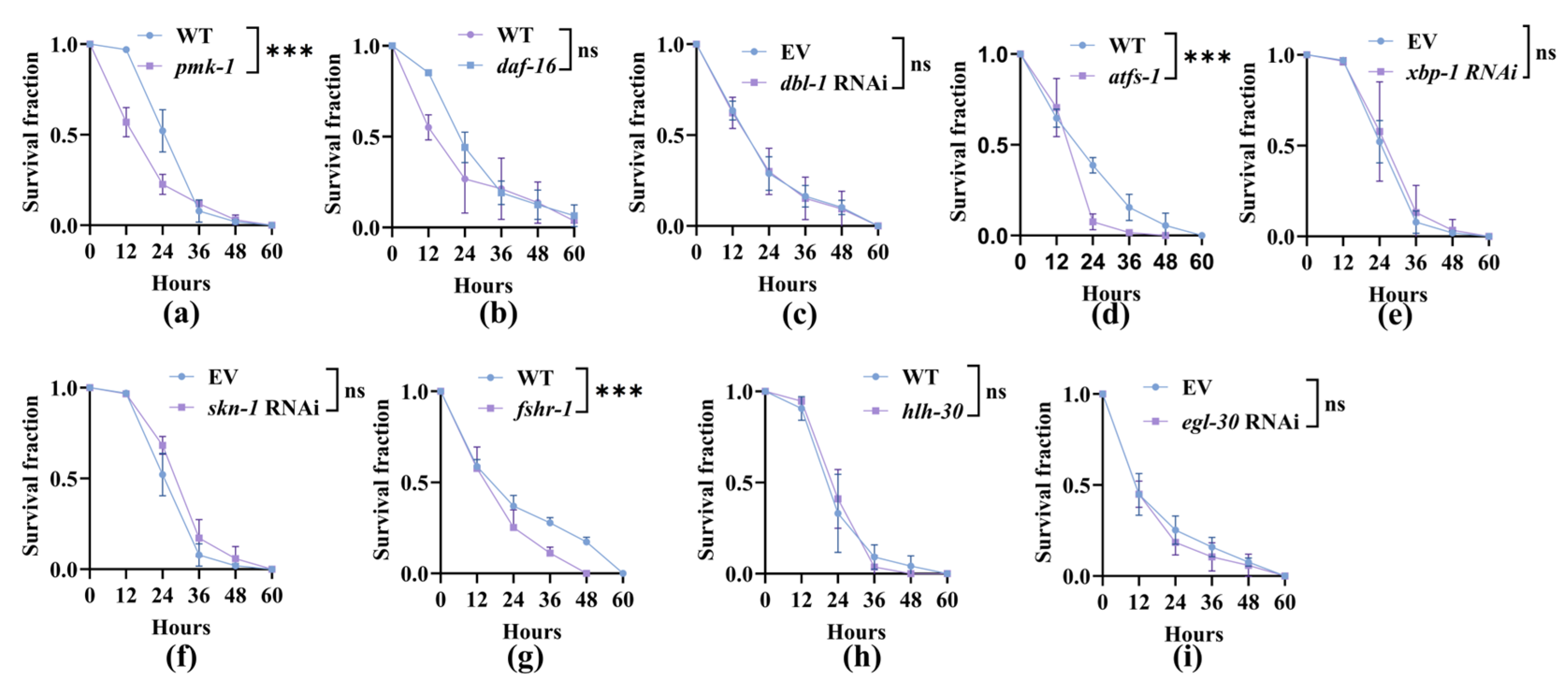

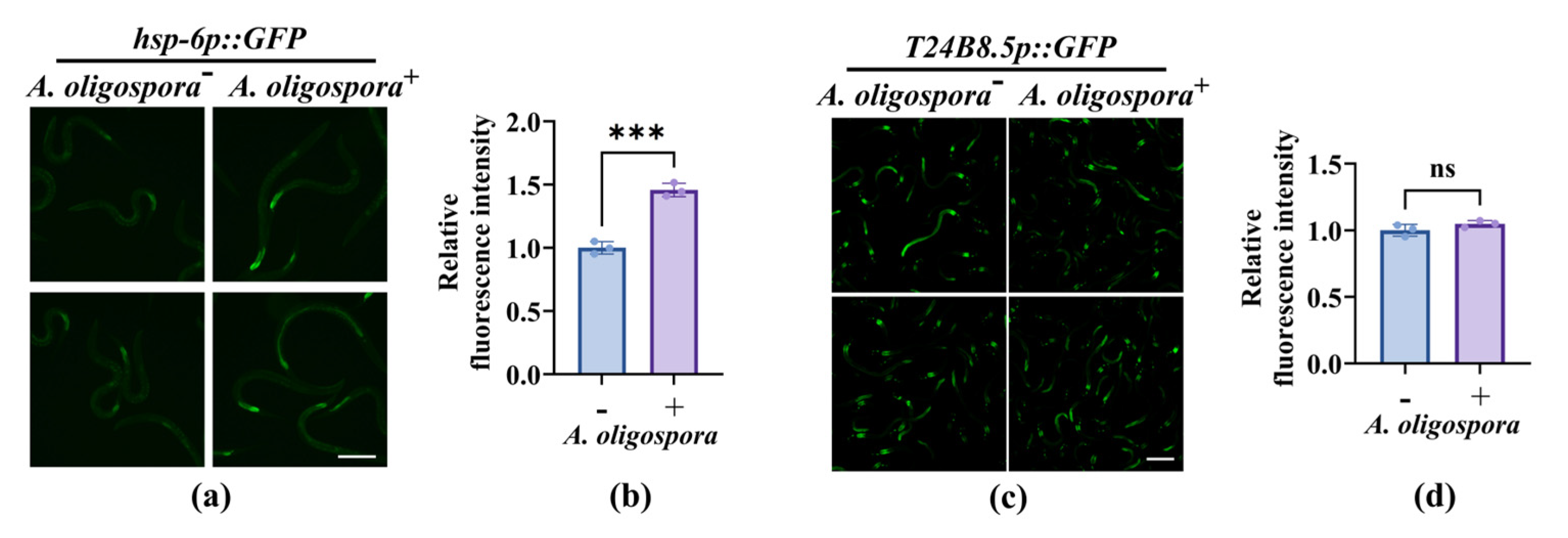

3.3. Nematodes Rely on Canonical Innate Immune Pathways to Improve Their Survival After the Capture by A. oligospora

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, X.; Hu, X.; Pop, M.; Wernet, N.; Kirschhöfer, F.; Brenner-Weiß, G.; Keller, J.; Bunzel, M.; Fischer, R. Fatal attraction of Caenorhabditis elegans to predatory fungi through 6-methyl-salicylic acid. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5462, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.H.; Chang, H.W.; Tay, R.J.; Hsueh, Y.P. Predation by nematode-trapping fungus triggers mechanosensory-dependent quiescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. iScience 2025, 28, 112792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.W.; Lin, H.C.; Yang, C.T.; Tay, R.J.; Chang, D.M.; Tung, Y.C.; Hsueh, Y.P. Cuticular collagens mediate cross-kingdom predator-prey interactions between trapping fungi and nematodes. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3003178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenburg, H.; Félix, M.A. The Natural Biotic Environment of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2017, 206, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.P.; Zhang, X.; Fornacca, D.; Yang, X.Y.; Xiao, W. Uncovering the biogeographic pattern of the widespread nematode-trapping fungi Arthrobotrys oligospora: Watershed is the key. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1152751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Xu, J. Fungi–Nematode Interactions: Diversity, Ecology, and Biocontrol Prospects in Agriculture. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-T.; Vidal-Diez de Ulzurrun, G.; Gonçalves, A.P.; Lin, H.-C.; Chang, C.-W.; Huang, T.-Y.; Chen, S.-A.; Lai, C.-K.; Tsai, I.J.; Schroeder, F.C.; et al. Natural diversity in the predatory behavior facilitates the establishment of a robust model strain for nematode-trapping fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 6762–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Xiang, M.; Liu, X. Nematode-Trapping Fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, W.; Qin, P.; Chinta, S.; Kong, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; et al. Ascarosides coordinate the dispersal of a plant-parasitic nematode with the metamorphosis of its vector beetle. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinoda, K.; Choe, A.; Hirahara, K.; Kiuchi, M.; Kokubo, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Hoki, J.S.; Suzuki, A.S.; Bose, N.; Appleton, J.A.; et al. Nematode ascarosides attenuate mammalian type 2 inflammatory responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2108686119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Tay, R.J.; Lin, H.C.; Juan, S.C.; Vidal-Diez de Ulzurrun, G.; Chang, Y.C.; Hoki, J.; Schroeder, F.C.; Hsueh, Y.P. The nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora detects prey pheromones via G protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1738–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Reuss, S.H.; Schroeder, F.C. Combinatorial chemistry in nematodes: Modular assembly of primary metabolism-derived building blocks. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Perez, D.H.; Jones Lipinski, R.A.; Butcher, R.A. Acyl-CoA Oxidases Fine-Tune the Production of Ascaroside Pheromones with Specific Side Chain Lengths. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhar, S.; Prajapati, D.V.; Gonzalez, M.S.; Yoon, C.S.; Mai, K.; Bailey, L.S.; Basso, K.B.; Butcher, R.A. Comparative Metabolomics Identifies the Roles of Acyl-CoA Oxidases in the Biosynthesis of Ascarosides and a Complex Family of Secreted N-Acylethanolamines. ACS Chem. Biol. 2025, 20, 1298–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bhar, S.; Jones Lipinski, R.A.; Han, J.; Feng, L.; Butcher, R.A. Biosynthetic tailoring of existing ascaroside pheromones alters their biological function in C. elegans. eLife 2018, 7, e33286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, L.; Chinta, S.; Singh, P.; Wang, Y.; Nunnery, J.K.; Butcher, R.A. Acyl-CoA oxidase complexes control the chemical message produced by Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3955–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambold, A.S.; Cohen, S.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Fatty acid trafficking in starved cells: Regulation by lipid droplet lipolysis, autophagy, and mitochondrial fusion dynamics. Dev. Cell 2015, 32, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zheng, D.; Liu, P.S.; Wang, S.; Xie, X. Peroxisomal homeostasis in metabolic diseases and its implication in ferroptosis. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2024, 22, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Blagodatskaya, E. Microbial hotspots and hot moments in soil: Concept & review. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2015, 83, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.K.; Yadav, M.R.; Mahala, D.M.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, D.; Yadav, N.; Yadav, S.L.; Sharma, V.K.; Yadav, S. Soil Microbial Hotspots and Hot Moments: Management vis-a-vis Soil Biodiversity. In Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Agricultural Sustainability: From Theory to Practices; Kumar, A., Meena, V.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ettema, C.H.; Wardle, D.A. Spatial soil ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002, 17, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, K.C.; Garsin, D.A. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Modulating the Caenorhabditis elegans Immune Response. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, N.; Zugasti, O.; Wong, D.; Couillault, C.; Kurz, C.L.; Schulenburg, H.; Ewbank, J.J. Anti-fungal innate immunity in C. elegans is enhanced by evolutionary diversification of antimicrobial peptides. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.C.; Dai, L.L.; Qiu, B.B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Ran, Y.; Zhang, K.Q.; Zou, C.G. TOR functions as a molecular switch connecting an iron cue with host innate defense against bacterial infection. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.G.; Ma, Y.C.; Dai, L.L.; Zhang, K.Q. Autophagy protects C. elegans against necrosis during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12480–12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.R.; Kim, D.H.; Ausubel, F.M. The G protein-coupled receptor FSHR-1 is required for the Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2782–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Sieburth, D. FSHR-1/GPCR Regulates the Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2020, 214, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N.D.; Icso, J.D.; Salisbury, J.E.; Rodríguez, T.; Thompson, P.R.; Pukkila-Worley, R. Pathogen infection and cholesterol deficiency activate the C. elegans p38 immune pathway through a TIR-1/SARM1 phase transition. eLife 2022, 11, e74206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpilka, T.; Du, Y.; Yang, Q.; Melber, A.; Uma Naresh, N.; Lavelle, J.; Kim, S.; Liu, P.; Weidberg, H.; Li, R.; et al. UPRmt scales mitochondrial network expansion with protein synthesis via mitochondrial import in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, J. The Arf-GAP Proteins AoGcs1 and AoGts1 Regulate Mycelial Development, Endocytosis, and Pathogenicity in Arthrobotrys oligospora. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xie, M.; Bai, N.; Yang, L.; Zhang, K.Q.; Yang, J. The Autophagy-Related Gene Aolatg4 Regulates Hyphal Growth, Sporulation, Autophagosome Formation, and Pathogenicity in Arthrobotrys oligospora. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 592524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, N.; Xie, M.; Zhang, K.Q.; Yang, J. Aolatg1 and Aolatg13 Regulate Autophagy and Play Different Roles in Conidiation, Trap Formation, and Pathogenicity in the Nematode-Trapping Fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 824407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.T.; Hsu, A.L. Solid plate-based dietary restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2011, 28, e2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petratou, D.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Lionaki, E.; Tavernarakis, N. Assessing locomotory rate in response to food for the identification of neuronal and muscular defects in C. elegans. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, R.S.; Ahringer, J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 2003, 30, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Y.P.; Mahanti, P.; Schroeder, F.C.; Sternberg, P.W. Nematode-trapping fungi eavesdrop on nematode pheromones. Curr. Biol. CB 2013, 23, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Joo, H.J.; Park, S.; Paik, Y.K. Ascaroside Pheromones: Chemical Biology and Pleiotropic Neuronal Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, K.; Kurz, C.L.; Cypowyj, S.; Couillault, C.; Pophillat, M.; Pujol, N.; Ewbank, J.J. Antifungal innate immunity in C. elegans: PKCdelta links G protein signaling and a conserved p38 MAPK cascade. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugasti, O.; Thakur, N.; Belougne, J.; Squiban, B.; Kurz, C.L.; Soulé, J.; Omi, S.; Tichit, L.; Pujol, N.; Ewbank, J.J. A quantitative genome-wide RNAi screen in C. elegans for antifungal innate immunity genes. BMC Biol. 2016, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, I.; Zhou, X.; Chernobrovkin, A.; Puerta-Cavanzo, N.; Kanno, T.; Salignon, J.; Stoehr, A.; Lin, X.X.; Baskaner, B.; Brandenburg, S.; et al. DAF-16/FOXO requires Protein Phosphatase 4 to initiate transcription of stress resistance and longevity promoting genes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, S.K.; Van Raamsdonk, J.M. High confidence ATFS-1 target genes for quantifying activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Micropublication Biol. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanmohammadi, N.; Wang, S.; Schumacher, B. Somatic PMK-1/p38 signaling links environmental stress to germ cell apoptosis and heritable euploidy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 701, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.E.; Lee, Y.; Ham, S.; Lee, D.; Kwon, S.; Park, H.H.; Hwang, S.Y.; Yoo, J.Y.; Roh, T.Y.; Lee, S.V. Inhibition of the oligosaccharyl transferase in Caenorhabditis elegans that compromises ER proteostasis suppresses p38-dependent protection against pathogenic bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.S.; Brown, M.; Dobosiewicz, M.; Ishida, I.G.; Macosko, E.Z.; Zhang, X.; Butcher, R.A.; Cline, D.J.; McGrath, P.T.; Bargmann, C.I. Balancing selection shapes density-dependent foraging behaviour. Nature 2016, 539, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, O.; Akagi, A.E.; Artyukhin, A.B.; Judkins, J.C.; Le, H.H.; Mahanti, P.; Cohen, S.M.; Sternberg, P.W.; Schroeder, F.C. Biosynthesis of Modular Ascarosides in C. elegans. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 4729–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.B.; Sahu, A.; Sahu, N.; Singh, R.K.; Renu, S.; Singh, D.P.; Manna, M.C.; Sarma, B.K.; Singh, H.B.; Singh, K.P. Arthrobotrys oligospora-mediated biological control of diseases of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) caused by Meloidogyne incognita and Rhizoctonia solani. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, L.K.T.; Soares, F.E.F.; Sharma, A.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Valdivia-Padilla, A.V.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. Strategy of Nematophagous Fungi in Determining the Activity of Plant Parasitic Nematodes and Their Prospective Role in Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 863198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers, R.P.; Pagano, D.J.; Kooistra, T.; Richardson, C.E.; Reddy, K.C.; Whitney, J.K.; Kamanzi, O.; Matsumoto, K.; Hisamoto, N.; Kim, D.H. Phosphorylation of the Conserved Transcription Factor ATF-7 by PMK-1 p38 MAPK Regulates Innate Immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, M.W.; Nargund, A.M.; Kirienko, N.V.; Gillis, R.; Fiorese, C.J.; Haynes, C.M. Mitochondrial UPR-regulated innate immunity provides resistance to pathogen infection. Nature 2014, 516, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.D.; Kao, C.Y.; Liu, B.Y.; Huang, S.W.; Kuo, C.J.; Ruan, J.W.; Lin, Y.H.; Huang, C.R.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, H.D.; et al. HLH-30/TFEB-mediated autophagy functions in a cell-autonomous manner for epithelium intrinsic cellular defense against bacterial pore-forming toxin in C. elegans. Autophagy 2017, 13, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, D.; Csermely, P.; Sőti, C. A Role for SKN-1/Nrf in Pathogen Resistance and Immunosenescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.-G.; Tu, Q.; Niu, J.; Ji, X.-L.; Zhang, K.-Q. The DAF-16/FOXO Transcription Factor Functions as a Regulator of Epidermal Innate Immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zugasti, O.; Ewbank, J.J. Neuroimmune regulation of antimicrobial peptide expression by a noncanonical TGF-beta signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans epidermis. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, J.-H.; He, Z.-K.; Gong, X.-Q.; Zhao, Q.; Tang, X.-Y.; Zou, C.-G.; Ma, Y.-C. Nutrient State-Dependent Ascarosides and Nematode Immune Response Limit the Predation of Arthrobotrys oligospora. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2816. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122816

Duan J-H, He Z-K, Gong X-Q, Zhao Q, Tang X-Y, Zou C-G, Ma Y-C. Nutrient State-Dependent Ascarosides and Nematode Immune Response Limit the Predation of Arthrobotrys oligospora. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2816. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122816

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Jia-Hong, Zhong-Kan He, Xin-Qian Gong, Qiu Zhao, Xin-Yue Tang, Cheng-Gang Zou, and Yi-Cheng Ma. 2025. "Nutrient State-Dependent Ascarosides and Nematode Immune Response Limit the Predation of Arthrobotrys oligospora" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2816. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122816

APA StyleDuan, J.-H., He, Z.-K., Gong, X.-Q., Zhao, Q., Tang, X.-Y., Zou, C.-G., & Ma, Y.-C. (2025). Nutrient State-Dependent Ascarosides and Nematode Immune Response Limit the Predation of Arthrobotrys oligospora. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2816. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122816