Deciphering the Post-Operative Dynamics of Opportunistic Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Fecal Sample Collection

2.2. Bacterial DNA Extraction from Fecal Samples

2.3. Bacterial Detection by Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of CRC-Associated Gut Microbiota

2.5. Metagenomic Sequencing and Raw Data Processing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Cohort

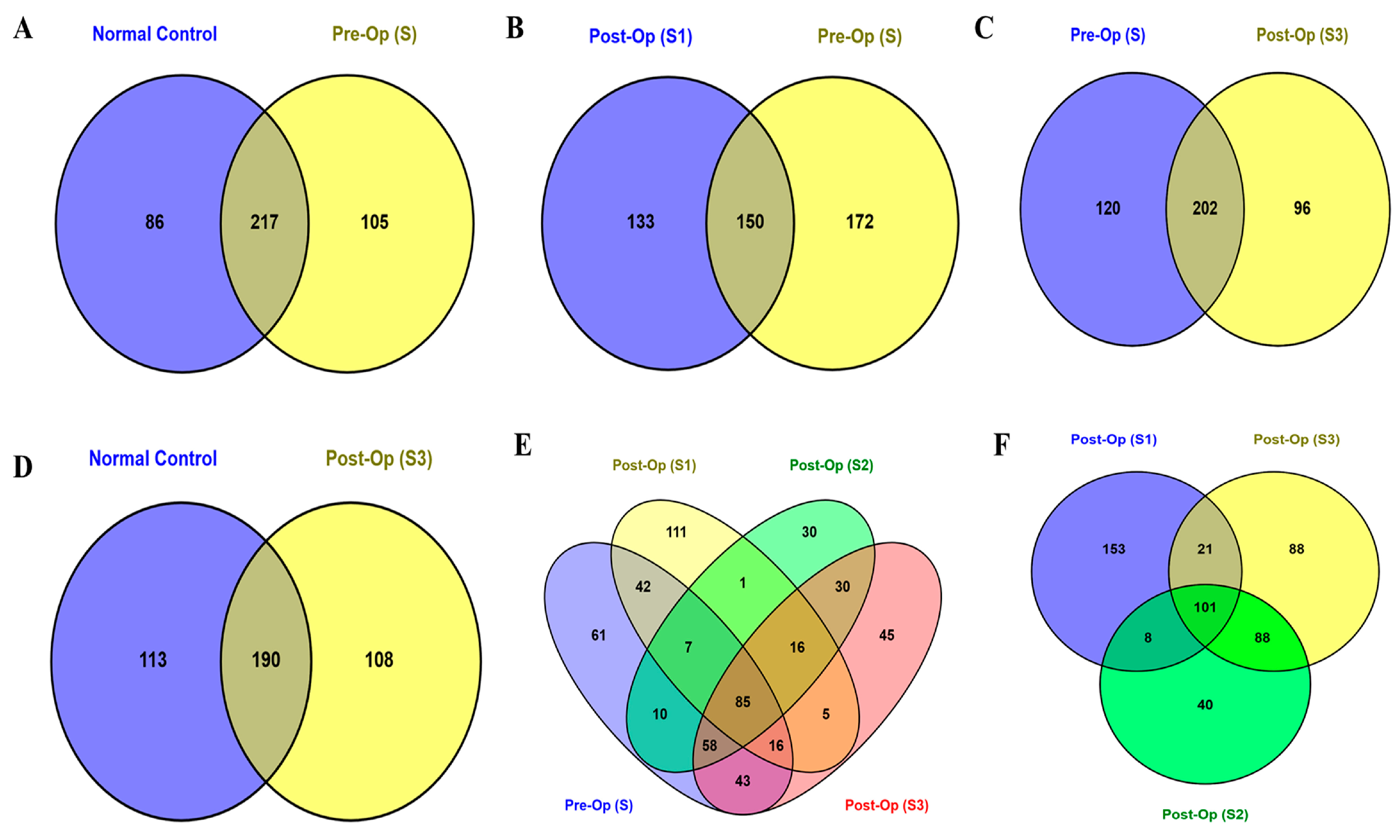

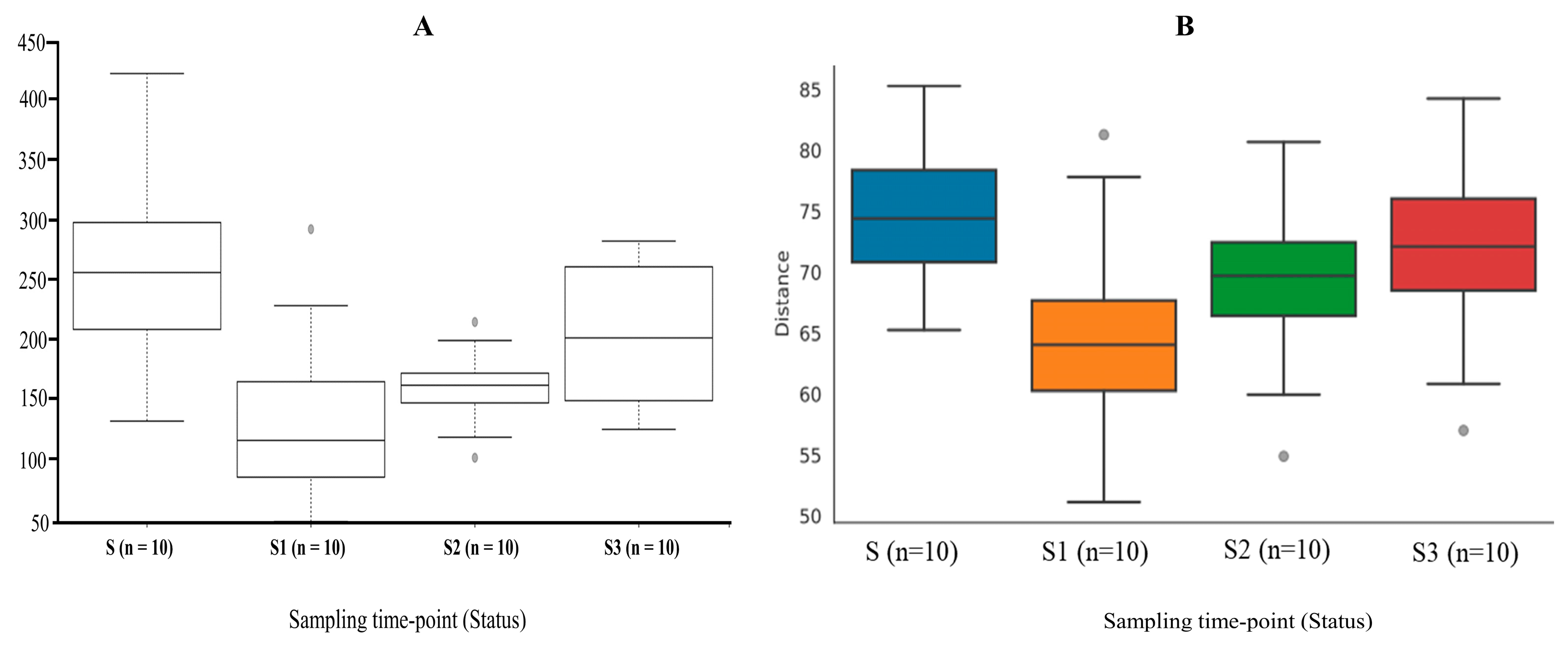

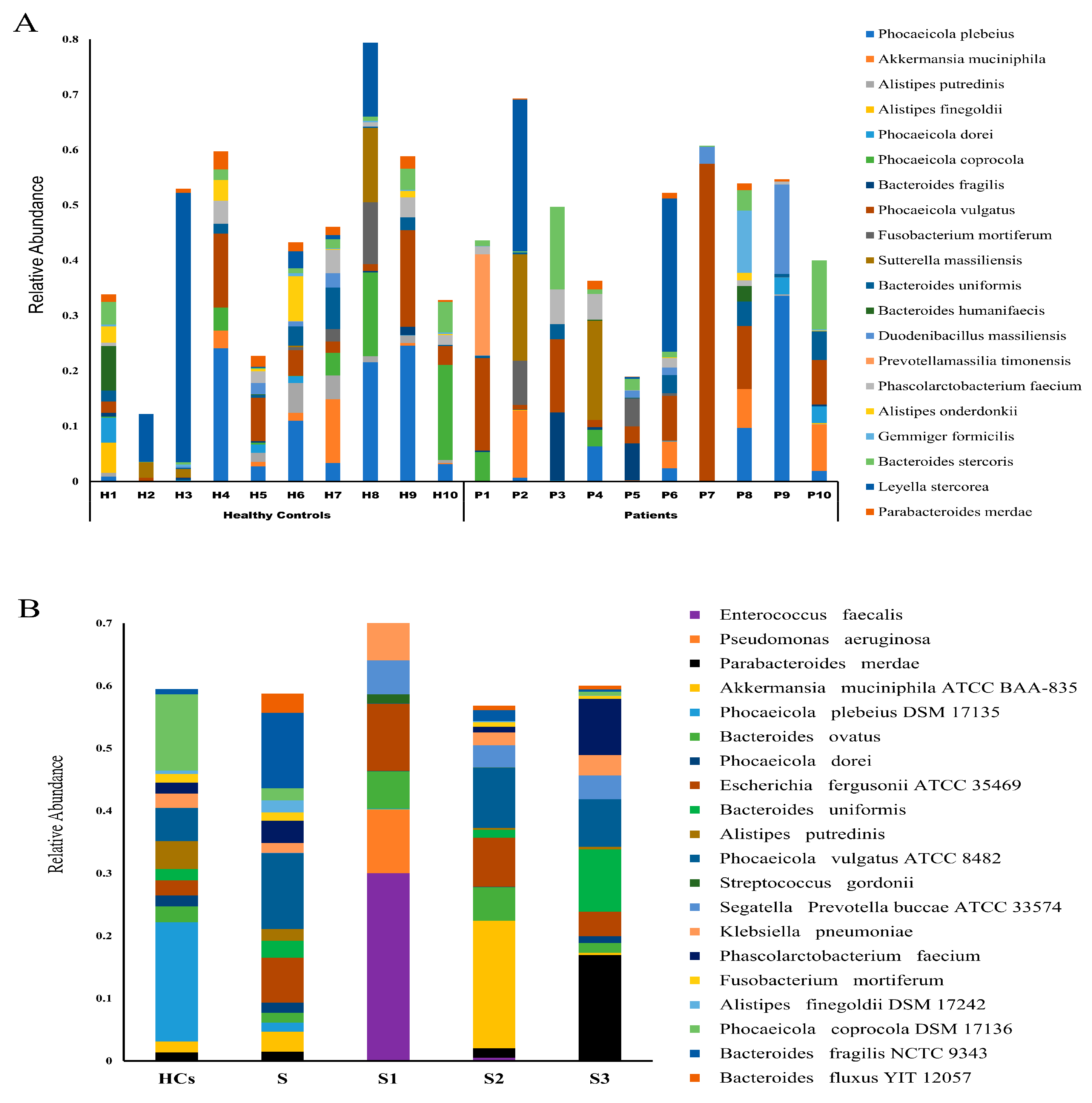

3.2. Microbial Community Composition and Diversity

3.3. The Shift in the Gut Microbial Diversity and Richness in Response to Colorectal Resection

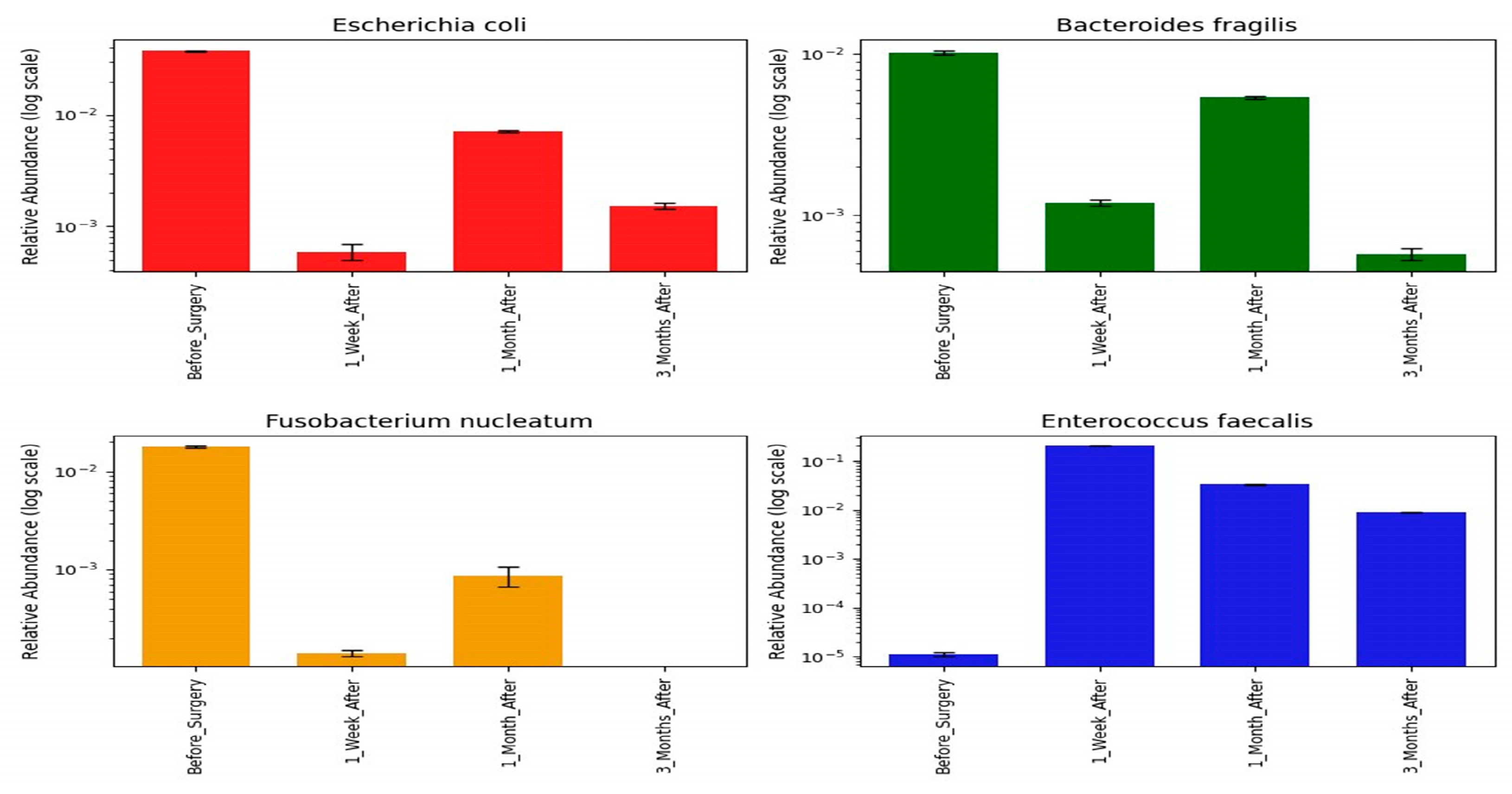

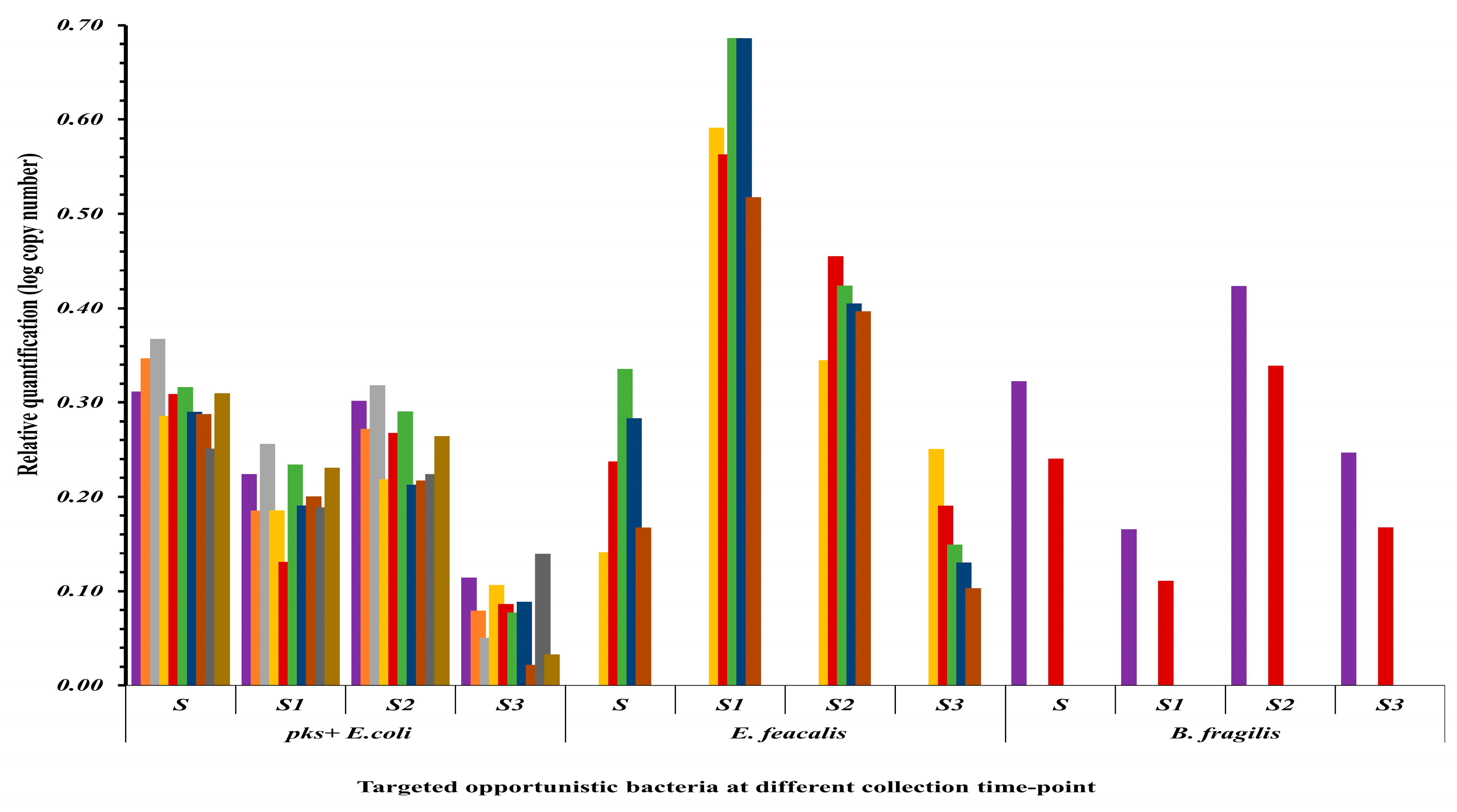

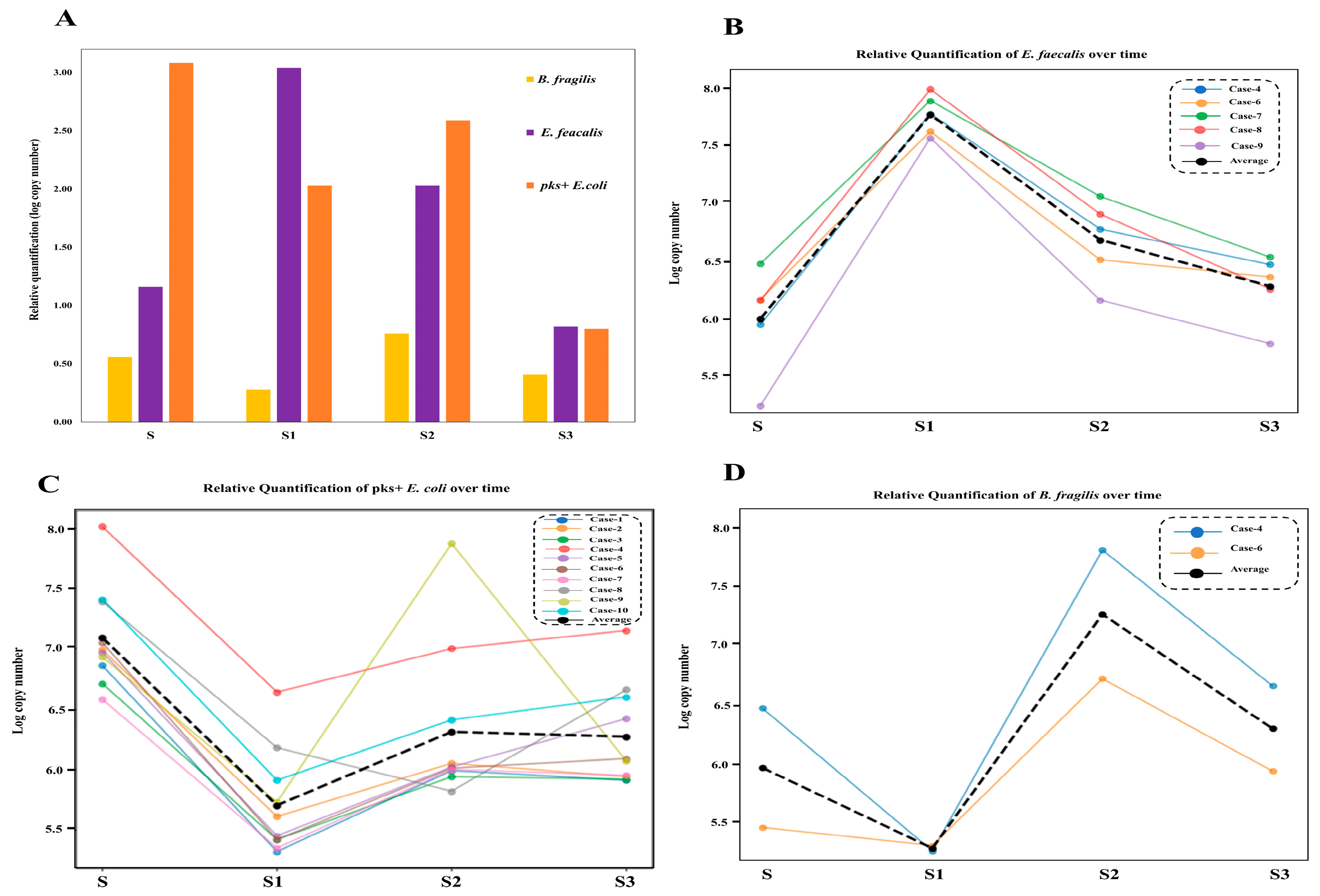

3.4. Shifts in Opportunistic Gut Microbiota Following CRC Surgery

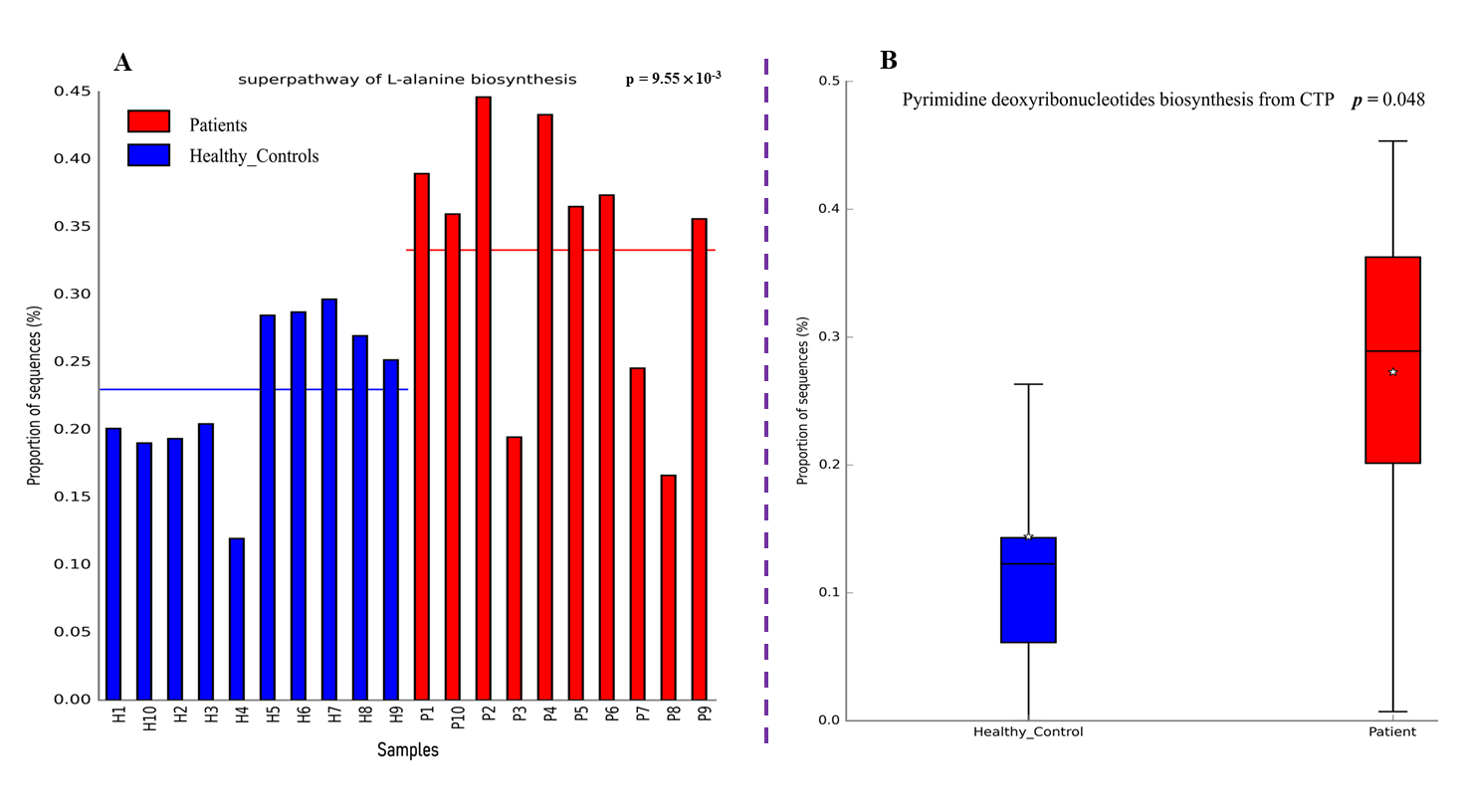

3.5. Functional and Metabolic Analysis of the Gut Microbiota

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matsuda, T.; Fujimoto, A.; Igarashi, Y. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Public Health Strategies. Digestion 2025, 106, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukanov, V.V.; Vasyutin, A.V.; Tonkikh, J.L. Risk factors, prevention and screening of colorectal cancer: A rising problem. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 98629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, R.; Yang, Y.; Jobin, C. Western diet influences on microbiome and carcinogenesis. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 67, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papier, K.; Bradbury, K.E.; Balkwill, A.; Barnes, I.; Smith-Byrne, K.; Gunter, M.J.; Berndt, S.I.; Le Marchand, L.; Wu, A.H.; Peters, U. Diet-wide analyses for risk of colorectal cancer: Prospective study of 12,251 incident cases among 542,778 women in the UK. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, K.L.; Frugé, A.D.; Heslin, M.J.; Lipke, E.A.; Greene, M.W. Diet as a risk factor for early-onset colorectal adenoma and carcinoma: A systematic review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 896330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, G.G.; Trevaskis, N.L.; Murphy, A.J.; Febbraio, M.A. Diet-induced gut dysbiosis and inflammation: Key drivers of obesity-driven NASH. iScience 2023, 26, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, R.J.; Pazienza, V. Impact of different types of diet on gut microbiota profiles and cancer prevention and treatment. Medicina 2019, 55, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Mestivier, D.; Sobhani, I. Contribution of pks+ Escherichia coli (E. coli) to Colon Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Wang, H.; Tao, Y.; Luo, K.; Ye, J.; Ran, S.; Guan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Huang, R. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: From phenomenon to mechanism. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1020583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgar-Zankbar, L.; Shariati, A.; Bostanghadiri, N.; Elahi, Z.; Mirkalantari, S.; Razavi, S.; Kamali, F.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Evaluation of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis correlation with the expression of cellular signaling pathway genes in Iranian patients with colorectal cancer. Infect. Agents Cancer 2023, 18, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Deng, M.; Chen, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Tao, L.; Yu, W.; Qiu, Y. Enterococcus faecalis promotes the progression of colorectal cancer via its metabolite: Biliverdin. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameni, F.; Elkhichi, P.A.; Dadashi, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Goudarzi, M.; Eshkalak, M.P.; Dadashi, M. Global prevalence of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Bacteroides fragilis in patients with colorectal cancer: An overview of case reports/case series and meta-analysis of prevalence studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.E.; Chu, Y.L.; Georgeson, P.; Walker, R.; Mahmood, K.; Clendenning, M.; Meyers, A.L.; Como, J.; Joseland, S.; Preston, S.G.; et al. Intratumoral presence of the genotoxic gut bacteria pks(+) E. coli, Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum and their association with clinicopathological and molecular features of colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Ramazzotti, D.; Heide, T.; Spiteri, I.; Fernandez-Mateos, J.; James, C.; Magnani, L.; Graham, T.A.; Sottoriva, A. Contribution of pks+ E. coli mutations to colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Puschhof, J.; Rosendahl Huber, A.; van Hoeck, A.; Wood, H.M.; Nomburg, J.; Gurjao, C.; Manders, F.; Dalmasso, G.; Stege, P.B. Mutational signature in colorectal cancer caused by genotoxic pks+ E. coli. Nature 2020, 580, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, A.I.; Hill, C.M.; Lin, G.; Malen, R.C.; Reedy, A.M.; Kahsai, O.; Ammar, H.; Curtis, K.; Ma, N.; Randolph, T.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum enrichment in colorectal tumor tissue: Associations with tumor characteristics and survival outcomes. Gastro Hep Adv. 2025, 4, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Guo, F.; Yu, Y.; Sun, T.; Ma, D.; Han, J.; Qian, Y.; Kryczek, I.; Sun, D.; Nagarsheth, N.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell 2017, 170, 548–563.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Leng, X.X.; Xie, Y.L.; Kang, Z.R.; Zhao, L.C.; Song, L.H.; Zhou, C.B.; Fang, J.Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by inhibiting pyroptosis via the Hippo pathway. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2333790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Wang, C.; Yu, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. Streptococcus bovis Contributes to the Development of Colorectal Cancer via Recruiting CD11b⁺TLR-4⁺ Cells. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e921886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.I.; Keskey, R.; Ackerman, M.T.; Zaborina, O.; Hyman, N.; Alverdy, J.C.; Shogan, B.D. Enterococcus faecalis Is Associated with Anastomotic Leak in Patients Undergoing Colorectal Surgery. Surg. Infect. 2021, 22, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Ting, N.L.; Wong, C.C.; Huang, P.; Jiang, L.; Liu, C.; Lin, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Xie, M.; et al. Bacteroides fragilis promotes chemoresistance in colorectal cancer, and its elimination by phage VA7 restores chemosensitivity. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 941–956.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, K.; Kasprzyk, P.; Nowicka, Z.; Noriko, S.; Herreros-de-Tejada, A.; Spychalski, M. Resection of Early Colorectal Neoplasms Using Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: A Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, A.L.; Green, H.; Monlezun, D.J.; Beck, D.; Kann, B.; Vargas, H.D.; Whitlow, C.; Margolin, D. The Role of Bowel Preparation in Colorectal Surgery: Results of the 2012-2015 ACS-NSQIP Data. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, J.W.T.; Chen, G.; Yang, P.; Reza, F.; Pathmanathan, N.; El Khoury, T.; Smith, S.; Engel, A.; Rickard, M.; Keshava, A. Bowel preparation and oral antibiotic agents for selective decontamination in colorectal surgery: Current practice, perspectives, and trends in Australia and New Zealand, 2019–2020. Surg. Infect. 2021, 22, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigalou, C.; Paraschaki, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Aftzoglou, K.; Stavropoulou, E.; Tsakris, Z.; Vradelis, S.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Alterations of gut microbiome following gastrointestinal surgical procedures and their potential complications. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1191126, Erratum in Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1281527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, L.; Troester, A.; Jahansouz, C. The Impact of Surgical Bowel Preparation on the Microbiome in Colon and Rectal Surgery. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R.; Leonard, D.; Delzenne, N.; Kartheuser, A.; Cani, P.D. Novel insight into the role of microbiota in colorectal surgery. Gut 2017, 66, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Png, C.-W.; Chua, Y.-K.; Law, J.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, K.-K. Alterations in co-abundant bacteriome in colorectal cancer and its persistence after surgery: A pilot study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.X.; Law, J.-H.; Png, C.-W.; Alberts, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, J.J.H.; Tan, K.-K. Alterations in colorectal cancer virome and its persistence after surgery. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.K.; Lin, W.C.; Huang, S.W.; Pan, Y.C.; Hu, C.W.; Mou, C.Y.; Hu, C.J.; Mou, K.Y. Bacteria colonization in tumor microenvironment creates a favorable niche for immunogenic chemotherapy. EMBO Mol. Med. 2024, 16, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yang, Z.; Dai, J.; Wu, T.; Jiao, Z.; Yu, Y.; Ning, K.; Chen, W.; Yang, A. Intratumor microbiome: Selective colonization in the tumor microenvironment and a vital regulator of tumor biology. MedComm 2023, 4, e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S.; Kim, B.; Kim, M.J.; Roh, S.J.; Park, S.C.; Kim, B.C.; Han, K.S.; Hong, C.W.; Sohn, D.K.; Oh, J.H. The effect of curative resection on fecal microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer: A prospective pilot study. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2020, 99, 44–51, Erratum in Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2021, 100, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serna, G.; Ruiz-Pace, F.; Hernando, J.; Alonso, L.; Fasani, R.; Landolfi, S.; Comas, R.; Jimenez, J.; Elez, E.; Bullman, S.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum persistence and risk of recurrence after preoperative treatment in locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigematsu, Y.; Saito, R.; Kanda, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Takeuchi, K.; Takahashi, S.; Inamura, K. Inverse Correlation between pks-Carrying Escherichia coli Abundance in Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases and the Number of Organs Involved in Recurrence. Cancers 2024, 16, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Dunn, L. The Declaration of Helsinki on Medical Research involving Human Subjects: A Review of Seventh Revision. J. Nepal. Health Res. Counc. 2020, 17, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Tohya, M.; Fukuda, S.; Suda, W.; Nishijima, S.; Takeuchi, F.; Ohsugi, M.; Tsujimoto, T.; Nakamura, T.; Shimomura, A. Effects of bowel preparation on the human gut microbiome and metabolome. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isokääntä, H.; Tomnikov, N.; Vanhatalo, S.; Munukka, E.; Huovinen, P.; Hakanen, A.J.; Kallonen, T. High-throughput DNA extraction strategy for fecal microbiome studies. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0293223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, D.; Li, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Lv, H.; Liu, K.; Hao, C.; Tian, Z.; et al. A Pilot Study: Changes of Gut Microbiota in Post-surgery Colorectal Cancer Patients. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, M.; Park, S.-J. Identification of microbial profiles in heavy-metal-contaminated soil from full-length 16s rRNA reads sequenced by a pacbio system. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, A.; Koner, S.; Chen, J.-S.; Hussain, A.; Huang, S.-W.; Hussain, B.; Hsu, B.-M. Uncovering the microbial community structure and physiological profiles of terrestrial mud volcanoes: A comprehensive metagenomic insight towards their trichloroethylene biodegradation potentiality. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avril, M.; DePaolo, R.W. “Driver-passenger” bacteria and their metabolites in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1941710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, T.N.; Le Huy, H.; Thanh, Q.Đ.; Thi, H.N.; Minh, H.N.T.; Dang, M.N.; Le Huu, S.; Tat, T.N. Association between Bacteroides fragilis and Fusobacterium nucleatum infection and colorectal cancer in Vietnamese patients. Anaerobe 2024, 88, 102880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.; Easwaran, H. Genetic and epigenetic dependencies in colorectal cancer development. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2022, 10, goac035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, N.; Zhuang, L. Development and validation of epigenetic modification-related signals for the diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal cancer. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Jin, Y.; Chen, G.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L. Gut microbiota dysbiosis drives the development of colorectal cancer. Digestion 2021, 102, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Du, L.; Shi, D.; Kong, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Ma, Y. Dysbiosis of human gut microbiome in young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulack, B.C.; Nussbaum, D.P.; Keenan, J.E.; Ganapathi, A.M.; Sun, Z.; Worni, M.; Migaly, J.; Mantyh, C.R. Surgical Resection of the Primary Tumor in Stage IV Colorectal Cancer Without Metastasectomy is Associated With Improved Overall Survival Compared With Chemotherapy/Radiation Therapy Alone. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2016, 59, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Han, D.; Zhu, Y. Colorectal cancer: Highlight the clinical research current progress. Holist. Integr. Oncol. 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, F.C.; Schneider, M.; Mathejczyk, W.; Weigand, M.A.; Figueiredo, J.C.; Li, C.I.; Shibata, D.; Siegel, E.M.; Toriola, A.T.; Ulrich, C.M. Postoperative complications are associated with long-term changes in the gut microbiota following colorectal cancer surgery. Life 2021, 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, A.; Maruyama, H.; Akagi, S.; Inoue, T.; Uemura, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Shiomi, H.; Watanabe, M.; Arai, H.; Kojima, Y.; et al. Do postoperative infectious complications really affect long-term survival in colorectal cancer surgery? A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2023, 7, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tang, J.; Xu, W.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, W. The implication of gut microbiota in recovery from gastrointestinal surgery. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsli, D.S.; Tbahriti, H.F.; Rahli, F.; Mahammi, F.Z.; Nagdalian, A.; Hemeg, H.A.; Imran, M.; Rauf, A.; Shariati, M.A. Probiotics in colorectal cancer prevention and therapy: Mechanisms, benefits, and challenges. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Kesika, P.; Chaiyasut, C. The Role of Probiotics in Colorectal Cancer Management. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 3535982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalluri-Butz, H.; Bobel, M.C.; Nugent, J.; Boatman, S.; Emanuelson, R.; Melton-Meaux, G.; Madoff, R.D.; Jahansouz, C.; Staley, C.; Gaertner, W.B. A pilot study demonstrating the impact of surgical bowel preparation on intestinal microbiota composition following colon and rectal surgery. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Ren, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Fu, W.; Wang, J.; Du, G. Tumorigenic bacteria in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms and treatments. Cancer Biol. Med. 2021, 19, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Rêgo, A.C.M.; Araújo-Filho, I. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Tumor Recurrence and Therapy Resistance in Colorectal Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. J. Surg. Postoper. Care 2024, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhadi, V.; Lahti, L.; Saberi, F.; Youssef, O.; Kokkola, A.; Karla, T.; Tikkanen, M.; Rautelin, H.; Puolakkainen, P.; Salehi, R. Gut microbiota and host gene mutations in colorectal cancer patients and controls of Iranian and Finnish origin. Anticancer. Res. 2020, 40, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Davenport, E.R.; Beaumont, M.; Jackson, M.A.; Knight, R.; Ober, C.; Spector, T.D.; Bell, J.T.; Clark, A.G.; Ley, R.E. Genetic Determinants of the Gut Microbiome in UK Twins. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.A.; Bashir, H.; Zeng, M.Y. Lifelong partners: Gut microbiota-immune cell interactions from infancy to old age. Mucosal Immunol. 2025, 18, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.-Y.; Ning, M.-X.; Chen, D.-K.; Ma, W.-T. Interactions between the gut microbiota and the host innate immune response against pathogens. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoue, T.; Umesaki, Y.; Honda, K. Immune responses to gut microbiota-commensals and pathogens. Gut Microbes 2010, 1, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Vogelzang, A.; Maruya, M.; Miyajima, M.; Murata, M.; Son, A.; Kuwahara, T.; Tsuruyama, T.; Yamada, S.; Matsuura, M.; et al. IgA regulates the composition and metabolic function of gut microbiota by promoting symbiosis between bacteria. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 2019–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzi, F.; Bianchi, P.; Malesci, A.; Laghi, L. Prognostic value of innate and adaptive immunity in colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Văcărean-Trandafir, I.C.; Amărandi, R.-M.; Ivanov, I.C.; Dragoș, L.M.; Mențel, M.; Iacob, Ş.; Muşină, A.-M.; Bărgăoanu, E.-R.; Roată, C.E.; Morărașu, Ș. Impact of antibiotic prophylaxis on gut microbiota in colorectal surgery: Insights from an Eastern European stewardship study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 14, 1468645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogan, B.D.; Belogortseva, N.; Luong, P.M.; Zaborin, A.; Lax, S.; Bethel, C.; Ward, M.; Muldoon, J.P.; Singer, M.; An, G.; et al. Collagen degradation and MMP9 activation by Enterococcus faecalis contribute to intestinal anastomotic leak. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 286ra268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomila, A.; Carratalà, J.; Badia, J.M.; Camprubí, D.; Piriz, M.; Shaw, E.; Diaz-Brito, V.; Espejo, E.; Nicolas, C.; Brugués, M. Preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa surgical site infections after elective colorectal surgery: A multicenter prospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Lou, X.; Xue, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, G. The influence of Akkermansia muciniphila on intestinal barrier function. Gut Pathog. 2024, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, T.; Zhou, X.; Qian, M.; Yang, Z.; Han, X. Akkermansia muciniphila identified as key strain to alleviate gut barrier injury through Wnt signaling pathway. eLife 2025, 12, RP92906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R.; Van Hul, M.; Baldin, P.; Léonard, D.; Delzenne, N.M.; Belzer, C.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Repsilber, D.; Rangel, I.; Kartheuser, A.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila Reduces Peritonitis and Improves Intestinal Tissue Wound Healing after a Colonic Transmural Defect by a MyD88-Dependent Mechanism. Cells 2022, 11, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, M.C.; Belda, E.; Prifti, E.; Everard, A.; Kayser, B.D.; Bouillot, J.L.; Chevallier, J.M.; Pons, N.; Le Chatelier, E.; Ehrlich, S.D.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila abundance is lower in severe obesity, but its increased level after bariatric surgery is not associated with metabolic health improvement. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 317, E446–E459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Yang, H.; Chen, C.; Qin, M.; Wen, Z.; He, Z.; Xu, L. Akkermansia muciniphila: A potential target and pending issues for oncotherapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 196, 106916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, P.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X. Function and therapeutic prospects of next-generation probiotic Akkermansia muciniphila in infectious diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1354447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Ou, Z.; Peng, Y. Phascolarctobacterium faecium abundant colonization in human gastrointestinal tract. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 3122–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquer-Esteban, S.; Ruiz-Ruiz, S.; Arnau, V.; Diaz, W.; Moya, A. Exploring the universal healthy human gut microbiota around the World. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Fujii, T.; Takahashi, H.; Kuramitsu, K.; Funasaka, K.; Ohno, E.; Akimoto, S.; Nakauchi, M.; Shibasaki, S.; Uyama, I.; et al. Association between Microbiome Dysbiosis and Postoperative Disorders before and after Gastrectomy. Digestion 2025, 106, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.; Gao, R.; Yan, X.; Huang, L.; He, J.; Li, H.; You, J.; Qin, H. Alterations in intestinal microbiota of colorectal cancer patients receiving radical surgery combined with adjuvant CapeOx therapy. Sci. China Life Sci. 2019, 62, 1178–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Yang, X.; Zeng, M.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, J.; He, P.; Sun, J.; Xie, Q.; Chang, X.; Zhang, S. The role of fecal Fusobacterium nucleatum and pks+ Escherichia coli as early diagnostic markers of colorectal cancer. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 1171239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Razavi, S.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E.; Jahanbin, B.; Akbari, A.; Norzaee, S.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Association between colorectal cancer and Fusobacterium nucleatum and Bacteroides fragilis bacteria in Iranian patients: A preliminary study. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2021, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández--González, P.I.; Barquín, J.; Ortega--Ferrete, A.; Patón, V.; Ponce-Alonso, M.; Romero-Hernández, B.; Ocaña, J.; Caminoa, A.; Conde-Moreno, E.; Galeano, J. Anastomotic leak in colorectal cancer surgery: Contribution of gut microbiota and prediction approaches. Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 2187–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.A.; Wienholts, K.; Williamson, A.J.; Gaines, S.; Hyoju, S.; van Goor, H.; Zaborin, A.; Shogan, B.D.; Zaborina, O.; Alverdy, J.C. Enterococcus faecalis exploits the human fibrinolytic system to drive excess collagenolysis: Implications in gut healing and identification of druggable targets. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2020, 318, G1–G9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, S.; Sharma, D.; Bisht, D.; Khan, A.U. Identification of factors involved in Enterococcus faecalis biofilm under quercetin stress. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 126, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, C.V.; Taddei, A.; Amedei, A. The controversial role of Enterococcus faecalis in colorectal cancer. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1756284818783606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.J.; Jacobson, R.; van Praagh, J.; Gaines, S.; Koo, H.Y.; Lee, B.; Chan, W.-C.; Weichselbaum, R.; Alverdy, J.C.; Zaborina, O. Enterococcus faecalis promotes a migratory and invasive phenotype in colon cancer cells. Neoplasia 2022, 27, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Rocha, E.R.; Smith, C.J. Efficient utilization of complex N-linked glycans is a selective advantage for Bacteroides fragilis in extraintestinal infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12901–12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, J.; Geng, F.; Nie, S. Bacteroides utilization for dietary polysaccharides and their beneficial effects on gut health. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Tan, B. The role of glycosylated mucins in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and gut health. Anim. Nutr. 2025, 21, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, J.; Hayakawa, Y.; Tateno, H.; Fujiwara, H.; Kasuga, M.; Fujishiro, M. The role of gastric mucins and mucin-related glycans in gastric cancers. Cancer Sci. 2024, 115, 2853–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, A.-K.; Pisarski, P.; Kousoulas, L.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Hess, C.; Huber, R. Postoperative changes of the microbiome: Are surgical complications related to the gut flora? A systematic review. BMC Surg. 2017, 17, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazi, M.; Jamel, S.; Mullish, B.H.; Markar, S.R.; Hanna, G.B. Impact of gastrointestinal surgery upon the gut microbiome: A systematic review. Surgery 2022, 171, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Li, F.; Yang, R. The roles of gut microbiota metabolites in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer: Multiple insights for potential clinical applications. Gastro Hep Adv. 2024, 3, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, M.; Rossi, E.; Landini, P. The pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthetic pathway modulates production of biofilm determinants in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.E.; Weinberg, B.A.; Xiu, J.; El-Deiry, W.S.; Hwang, J.J.; Gatalica, Z.; Philip, P.A.; Shields, A.F.; Lenz, H.J.; Marshall, J.L. Comparative molecular analyses of left-sided colon, right-sided colon, and rectal cancers. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 86356–86368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. Influence of Foods and Nutrition on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Intestinal Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklu-Mensah, G.; Gilbert, J.; Devkota, S. Dietary selection pressures and their impact on the gut microbiome. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 13, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyadorai, T.; Mariappan, V.; Vellasamy, K.M.; Wanyiri, J.W.; Roslani, A.C.; Lee, G.K.; Sears, C.; Vadivelu, J. Prevalence and association of pks+ Escherichia coli with colorectal cancer in patients at the University Malaya Medical Centre, Malaysia. PloS ONE 2020, 15, e0228217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geravand, M.; Fallah, P.; Yaghoobi, M.H.; Soleimanifar, F.; Farid, M.; Zinatizadeh, N.; Yaslianifard, S. Investigation of enterococcus faecalis population in patients with polyp and colorectal cancer in comparison of healthy individuals. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2019, 56, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenneth, M.J.; Fang, C.-Y.; Wu, C.-C.; Hsieh, M.-C.; Lai, M.-L.; Hsu, B.-M. Deciphering the Post-Operative Dynamics of Opportunistic Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2818. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122818

Kenneth MJ, Fang C-Y, Wu C-C, Hsieh M-C, Lai M-L, Hsu B-M. Deciphering the Post-Operative Dynamics of Opportunistic Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2818. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122818

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenneth, Mutebi John, Chuan-Yin Fang, Chin-Chia Wu, Ming-Chih Hsieh, Ming-Liang Lai, and Bing-Mu Hsu. 2025. "Deciphering the Post-Operative Dynamics of Opportunistic Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Patients" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2818. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122818

APA StyleKenneth, M. J., Fang, C.-Y., Wu, C.-C., Hsieh, M.-C., Lai, M.-L., & Hsu, B.-M. (2025). Deciphering the Post-Operative Dynamics of Opportunistic Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2818. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122818