Metabolomic Analysis of Antifungal Secondary Metabolites from Achaetomium sophora HY17 in Co-Culture with Botrytis cinerea HM1

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Strain and Standard Substances

2.2. Evaluation of Antifungal Activity

2.3. Classification Status Identification of Strain HY17

2.4. Co-Culture Sample Collection

2.5. UPLC-MS/MS Detection and Analysis

2.5.1. Sample Extraction

2.5.2. UPLC-MS/MS Detection

2.5.3. Statistical Data Analysis

2.6. Determination of the Inhibitory Activity of Differential Metabolites

2.7. A. sophora HY17 Extraction and Determination of Alkaloids and Flavonoids

2.7.1. Extraction of Alkaloids and Flavonoids from Samples

2.7.2. Detection of Alkaloids by HPLC

2.7.3. Detection of Flavonoids by HPLC

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Antifungal Activity of Achaetomium sp. HY17

3.2. Classification and Identification of Achaetomium sp. HY17

3.3. Morphological Alterations of Co-Cultivated Fungal Mycelia

3.4. Quality Control of Metabolomic Samples and Comprehensive Sample Analysis

3.5. Dynamic Analysis of Differential Metabolites in A. sophora HY17 Monocultures

3.6. Metabolic Dynamics During the Interaction Between A. sophora HY17 and B. cinerea HM1

3.7. Quantitative Analysis of Differential Metabolites

3.8. Enrichment Analysis of Differential Metabolites Performed Using the KEGG Database

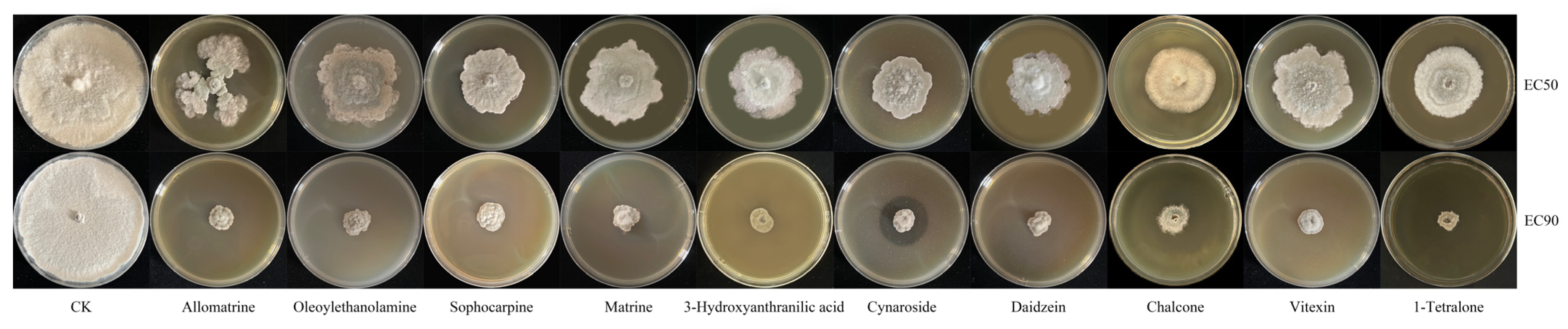

3.9. Verification of Antifungal Activity of Different Metabolites and Determination of Their Sources

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dinglasan, J.L.N.; Otani, H.; Doering, D.T.; Udwary, D.; Mouncey, N.J. Microbial secondary metabolites: Advancements to accelerate discovery towards application. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kumar, S.; Darokar, M.P.; Shanker, K. Novel bioactive compound from the bark of Putranjiva roxburghii Wall. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 35, 1738–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Liu, T.K.; Shi, Q.; Yang, X.L. Sesquiterpenoids and diterpenes with antimicrobial activity from Leptosphaeria sp. XL026, an endophytic fungus in Panax notoginseng. Fitoterapia 2019, 137, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, M.; Gupta, D.; Gupta, U.; Faraz, R.; Sandhu, S.S. Patents on Endophytic Fungi. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2017, 11, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.; Lim, C.K.; Marzuki, N.F.; Goh, Y.K.; Baharum, S.N. Metabolic Profile of Scytalidium parasiticum-Ganoderma boninense Co-Cultures Revealed the Alkaloids, Flavonoids and Fatty Acids that Contribute to Anti-Ganoderma Activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helge, B.B.D.; Barbara, B.D.; Regina, H.D. Big effects from small changes: Possible ways to explore nature’s chemical diversity. Chembiochem 2002, 3, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Jackson, S.A.; Patry, S.; Dobson, A.D.W. Extending the “One Strain Many Compounds” (OSMAC) Principle to Marine Microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida-Martinez, L.P.; Hertweck, C. Pathogenic fungus harbours endosymbiotic bacteria for toxin production. Nature 2005, 437, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitt, J.A.; Shipley, S.M.; Newman, D.J.; Zuck, K.M. Tetramic Acid Analogues Produced by Coculture of Saccharopolyspora erythraea with Fusarium pallidoroseum. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, S.; Ali, A.; Gupta, A.C.; Shanker, K.; Bawankule, D.U.; Luqman, S. Microwave-Assisted Single Step Cinnamic Acid Derivatization and Evaluation for Cytotoxic Potential. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.Y.; Wu, J.T.; Shao, C.L.; Li, Z.Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.Y. Co-culture: Stimulate the metabolic potential and explore the molecular diversity of natural products from microorganisms. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2021, 3, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.P.; Kang, B.; Duan, X.R.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Li, D.S.; Xu, N. Metabolomic profiles of the liquid state fermentation in co-culture of A. oryzae and Z. rouxii. Food Microbiol. 2022, 103, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Houbraken, J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Meijer, M.; Andersen, B.; Nielsen, K.F.; Crous, P.W.; Samson, R.A. Diversity and taxonomy of Chaetomiumand and chaetomium-like fungi from indoor environments. Stud. Mycol. 2016, 84, 145–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S.J.; Goldbeck, O.; Lkhaasuren, T.; Weixler, D.; Weiß, T.; Eikmanns, B.J. C-di-AMP Is a Second Messenger in Corynebacterium glutamicum That Regulates Expression of a Cell Wall-Related Peptidase via a Riboswitch. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Meng, K.; Bai, Y.G.; Shi, P.J.; Huang, H.Q.; Luo, H.Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Yang, P.L.; Song, W.; Yao, B. Two Family 11 Xylanases from Achaetomium sp. Xz-8 with High Catalytic Efficiency and Application Potentials in the Brewing Industry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 6880–6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.; Meng, K.; Bai, Y.G.; Shi, P.J.; Luo, H.Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Yang, P.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, W.; Yao, B. High-yield production of a low-temperature-active polygalacturonase for papaya juice clarification. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2974–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Gerald, B.K. O-Polysaccharides of LPS Modulate E. coli Uptake by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.T.; Zhang, Q.C.; Ju, M.X.; Yan, S.Y.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Gu, P.W. The Endophytic Fungi Diversity, Community Structure, and Ecological Function Prediction of Sophora alopecuroides in Ningxia, China. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.X.; Zhang, Q.C.; Wang, R.T.; Yan, S.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Gu, P. Correlation in endophytic fungi community diversity and bioactive compounds of Sophora alopecuroides. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 955647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.; Ma, S.; Shi, X.; Xue, W.; Liu, C.; Ding, H. Diversity and Antimicrobial Activity of Endophytic Fungi Isolated from Chloranthus japonicus Sieb in Qinling Mountains, China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, M.; Asgari, B.; Zare, R. Description of Allocanariomyces and Parachaetomium, two new genera, and Achaetomium aegilopis sp. nov. in the Chaetomiaceae. Mycol. Prog. Progress. 2020, 19, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.C.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.; Taylor, F.J.R.; White, T.J.; Lee, S.H.; Taylor, D.L.; Taylor, J.S. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 18, pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Samuels, G.J. Molecular systematics of the Hypocreales: A teleomorph gene phylogeny and the status of their anamorphs. Can. J. Bot. 1995, 73, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.W.; Yang, F.Y.; Meijer, M.; Kraak, B.; Sun, B.D.; Jiang, Y.L.; Wu, Y.M.; Bai, F.Y.; Seifert, K.A.; Crous, P.W.; et al. Redefining Humicola sensu stricto and related genera in the Chaetomiaceae. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 93, 65–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triastuti, A.; Haddad, M.; Barakat, F.; Mejia, K.; Rabouille, G.; Fabre, N.; Amasifuen, C.; Jargeat, P.; Vansteelandt, M. Dynamics of Chemical Diversity During Co-Cultures: An Integrative Time-Scale Metabolomics Study of Fungal Endophytes Cophinforma mamane and Fusarium solani. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2000672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Qi, D.; Zhou, D.; Wei, Y.; et al. Biocontrol potential of volatile organic compounds produced by Streptomyces corchorusii CG-G2 to strawberry anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.Y.; Liu, R.; Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Sun, Y. Establishment of an HPLC Method for Simultaneous Determination of Ten Flavonoids in Germinated Black Wheat. J. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 43, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, G.; Kapoor, N.; Chandra, G.; Gambhir, L. Cure lies in nature: Medicinal plants and endophytic fungi in curbing cancer. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.Y.; Wang, W.K.; Liu, G.L.; Gu, P. Optimization of culture conditions for the sophoridine producing new fungal species Achaelomium sophor strain HY17 isolated from seeds of Sophora alopecaroides. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2025, 34, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E. The use of fungal entomopathogens as endophytes in biological control: A review. Mycologia 2018, 110, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, M.D.; Lowor, S.T.; Bukari, Y.; Donkor, J.K.; Minnah, B.; Nuhu, A.H.; Dontoh, D.; Amadu, A.A.; Ocloo, A. Cocoa-associated filamentous fungi for the biocontrol of aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2023, 63, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Deng, X.; Gao, Q.; Wu, X.; Han, L.; Gao, X.; Zhao, S.; Chen, W.; Zhou, R.; Li, Z.; et al. Sophora alopecuroides L.: An ethnopharmacological, phytochemical, and pharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248, 112172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Y.; Jia, L.Y.; Rong, Z.; Zhou, X.; Cao, L.Q.; Li, A.H.; Guo, M.; Jin, J.; Wang, Y.D.; Huang, L.; et al. Research Advances on Matrine. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 867318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Gao, C.; Li, Z.; Guo, L.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y. Linking plant secondary metabolites and plant microbiomes: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 621276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Hulle, C.; Braeckman, P.; Vandewalle, M. Isolation of two new flavonoids from the root of Glycyrrhiza glabra var. typica. Planta Medica 1971, 20, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, M.F.; Sales, J.A.; da Rocha, M.G.; Galdino, L.M.; de Aguiar, L.; Pereira-Neto, W.D.; de Aguiar Cordeiro, R.; Castelo-Branco, D.D.; Sidrim, J.J.; Brilhante, R.S. Antifungal effects of the flavonoids kaempferol and quercetin: A possible alternative for the control of fungal biofilms. Figshare 2019, 35, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzakariya, B.Z.; Shakeri, A. Bioactive terpenoids derived from plant endophytic fungi: An updated review (2011–2020). Phytochemistry 2022, 197, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, H.B.; Negi, P.S. Phenolic acids from vegetables: A review on processing stability and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, R.; Rathee, P.; Akkol, E.K.; Khatkar, S.; Lather, A.; Redhu, N.; Khatkar, A. Phenolic Acids—Versatile Natural Moiety with Numerous Biological Applications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 1472–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.P.; Chen, X.Q.; Xie, S.N.; Chen, Y.J.; She, Z.G.; Lin, Y.C.; Tao, Y.W. Dihydroisocoumarin Compounds from Endophytic Fungi of Rhizophora apiculata and Its Antibacterial Activity. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 2018, 35, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wan, J.B.; Zhao, L. Research progress on the pharmacological activities of senkyunolides. Acupunct. Herb. Med. 2023, 3, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Fang, Y.; Huang, M.J.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.R.; Zhao, H. High flavonoid accompanied with high starch accumulation triggered by nutrient starvation in bioenergy crop duckweed (Landoltia punctata). BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Shin, H.-J.; Kwon, Y.J.; Chu, J.; Lee, I.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, S.-H.; Seo, H.W.; et al. Protective Effect of Novel Lactobacillus plantarum KC3 Isolated from Fermented Kimchi on Gut and Respiratory Disorders. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhlova, E.; Colom, J.; Simon, A.; Mazhar, S.; García-Lainez, G.; Llopis, S.; Gonzalez, N.; Enrique-López, M.; Álvarez, B.; Martorell, P.; et al. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Properties of a Novel Potential Probiotic Bacillus clausii CSI08. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Ye, C.; Che, J.; Xu, X.G.; Shao, D.Y.; Jiang, C.M.; Liu, Y.L.; Shi, J.L. Genomic sequencing, genome-scale metabolic network reconstruction, and in silico flux analysis of the grape endophytic fungus Alternaria sp. MG1. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Jia, F.; Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Sun, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, G. Streptomyces virginiae XDS1-5, an antagonistic actinomycete, as a biocontrol to peach brown rot caused by Monilinia fructicola. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 7514–7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathogenic Fungi | Inhibition Rate/% | |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous Inoculation | Delivery of HY17 for 3 Days Prior | |

| Botrytis cinerea HM1 | 74.60 ± 2.75 a | 92.86 ± 2.38 a |

| Rhizoctonia solani pn5-2 | 62.81 ± 1.34 a | 99.05 ± 0 a |

| Fusarium avenacea YM1 | 54.18 ± 2.41 b | 96.30 ± 1.50 a |

| Fusarium oxysporum pm29-3 | 49.49 ± 2.85 bc | 86.87 ± 2.86 c |

| Colletotrichum siamense NX2-7 | 68.08 ± 2.09 a | 92.44 ± 1.26 b |

| Fusarium tricuspidata pm36-8 | 49.52 ± 3.39 bc | 84.84 ± 0 c |

| Clonostachys rosea pm34-5 | 53.22 ± 2.49 bc | 54.20 ± 2.64 d |

| Pythium aphanidermatum pn8-3 | 46.42 ± 1.56 c | 86.12 ± 1.35 c |

| Compounds | Virulence Regression Equation | R2 | EC50 (μg/mL) | EC90 (μg/mL) | 95% Confidence Intervals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sophoridine | Y = 0.4902 × X − 44.04 | 0.9801 | 191.84 | 273.44 | 0.4483–0.5321 |

| Oleoylethanolamine | Y = 0.3554 × X − 21.80 | 0.9868 | 202.02 | 314.58 | 0.3336–0.3772 |

| Sophocarpine | Y = 0.3599 × X − 20.76 | 0.9902 | 196.61 | 307.75 | 0.3409–0.3789 |

| Matrine | Y = 0.3695 × X − 16.12 | 0.9791 | 178.94 | 287.21 | 0.3409–0.3981 |

| 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid | Y = 0.4791 × X − 43.43 | 0.9685 | 195.01 | 278.51 | 0.4273–0.5308 |

| Cynaroside | Y = 0.4419 × X − 37.04 | 0.9835 | 196.97 | 287.48 | 0.4015–0.4823 |

| Daidzein | Y = 0.3366 × X − 21.12 | 0.9692 | 211.29 | 330.12 | 0.3048–0.3684 |

| Chalcone | Y = 0.6828 × X + 9.011 | 0.9854 | 60.03 | 118.61 | 0.6387–0.7269 |

| Vitexin | Y = 0.3415 × X − 22.00 | 0.9675 | 210.83 | 327.96 | 0.2974–0.3856 |

| 1-Tetralone | Y = 0.2473 × X + 34.63 | 0.9894 | 62.15 | 223.91 | 0.2244–0.2702 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, G.; Tang, Z.; Wang, R.; Xin, Y.; Gu, P. Metabolomic Analysis of Antifungal Secondary Metabolites from Achaetomium sophora HY17 in Co-Culture with Botrytis cinerea HM1. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122794

Liu G, Tang Z, Wang R, Xin Y, Gu P. Metabolomic Analysis of Antifungal Secondary Metabolites from Achaetomium sophora HY17 in Co-Culture with Botrytis cinerea HM1. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122794

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Guanlan, Zhiyun Tang, Ruotong Wang, Ying Xin, and Peiwen Gu. 2025. "Metabolomic Analysis of Antifungal Secondary Metabolites from Achaetomium sophora HY17 in Co-Culture with Botrytis cinerea HM1" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122794

APA StyleLiu, G., Tang, Z., Wang, R., Xin, Y., & Gu, P. (2025). Metabolomic Analysis of Antifungal Secondary Metabolites from Achaetomium sophora HY17 in Co-Culture with Botrytis cinerea HM1. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2794. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122794