A Comprehensive Analysis of Microbial Community and Nitrogen Removal Rate Predictions in Three Anammox Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Processing of Literature Data

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.3. Diversity Analysis, Network Analysis and Data Visualization

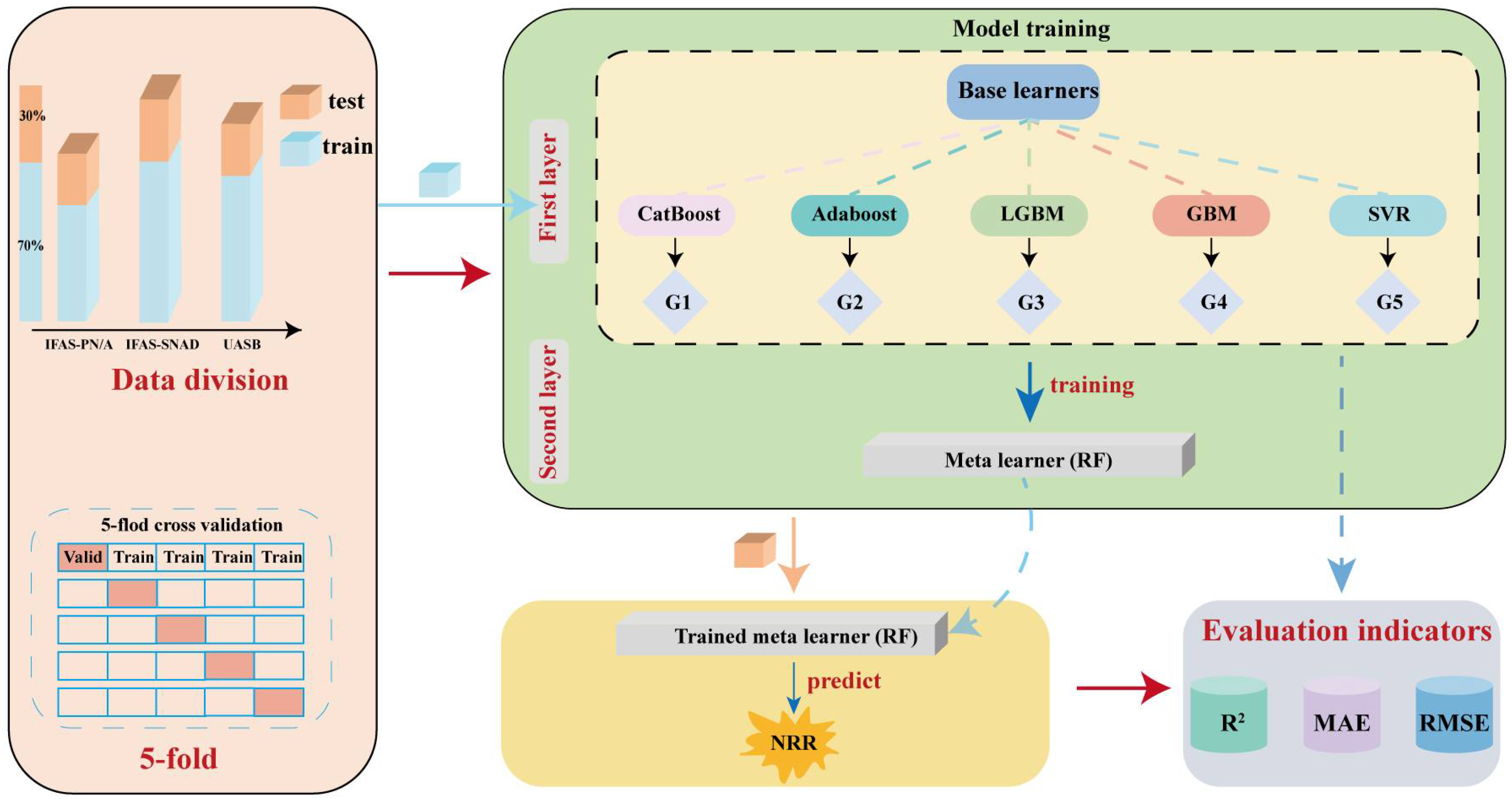

2.4. Machine Learning Model

2.5. Feature Importance Analysis and Data Visualization

3. Results and Discussion

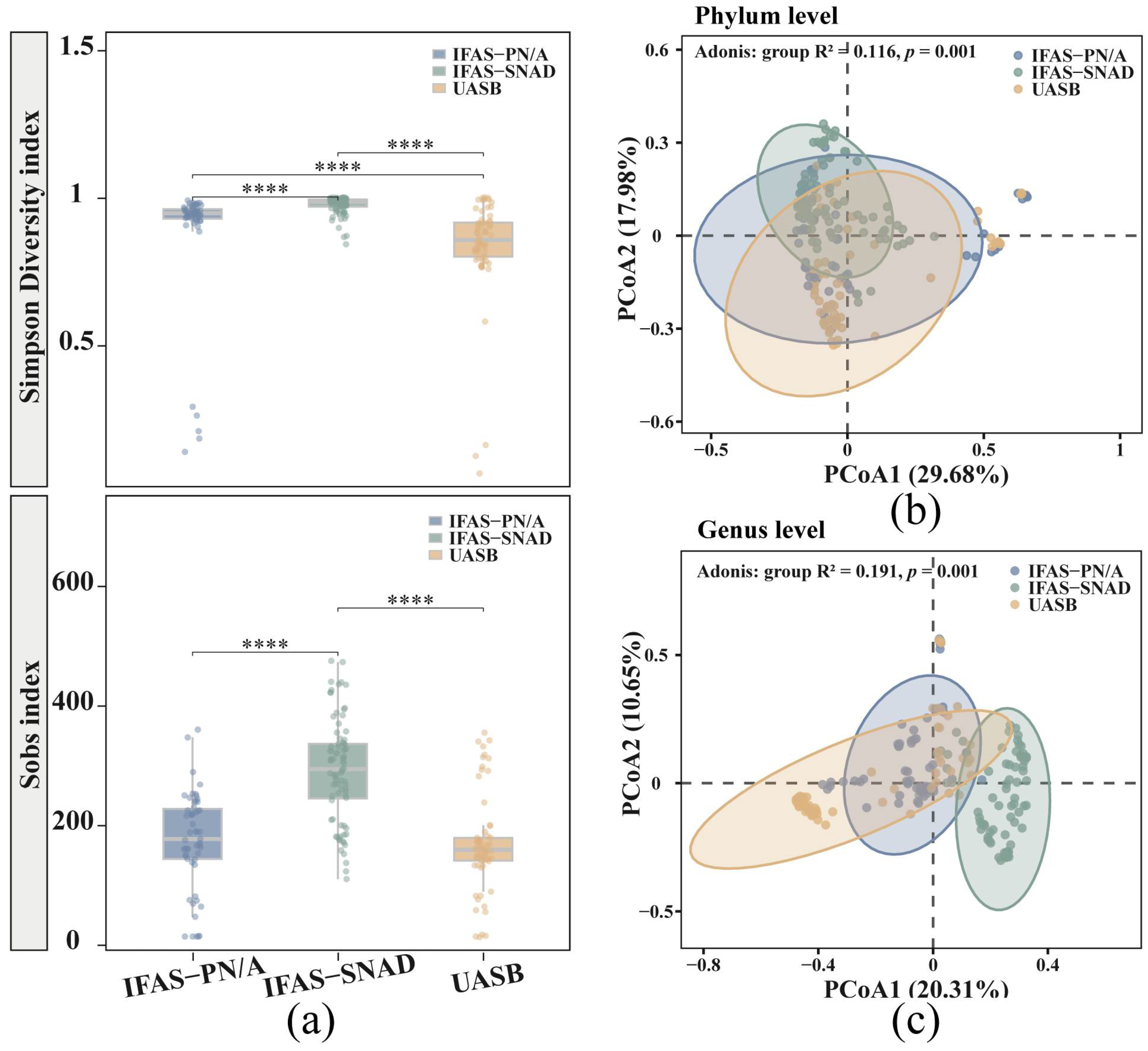

3.1. Distinct Microbial Community Diversity and Structures in Three Anammox Systems

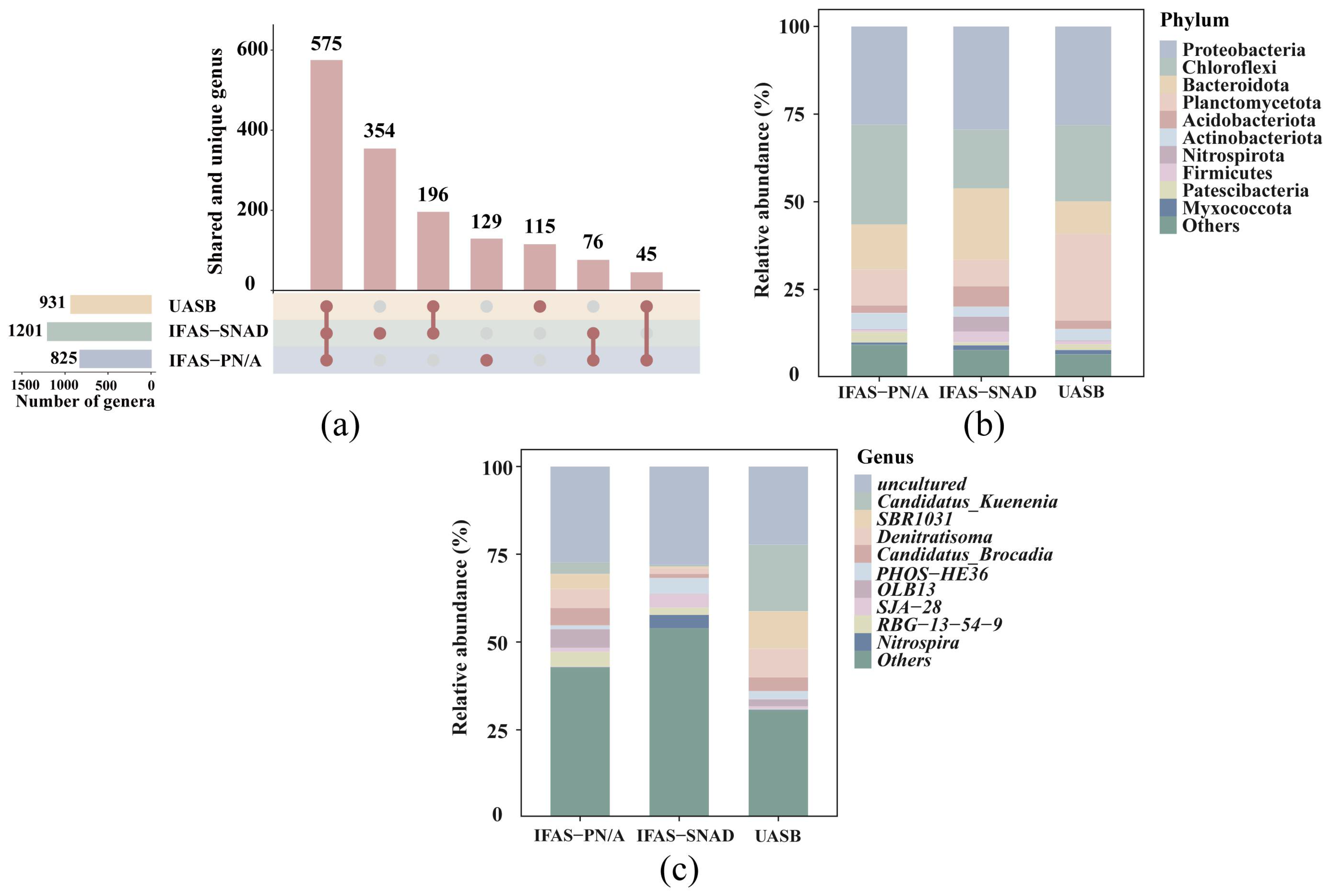

3.2. Differential Abundance of Taxonomic Compositions

3.3. Microbial Network Analysis

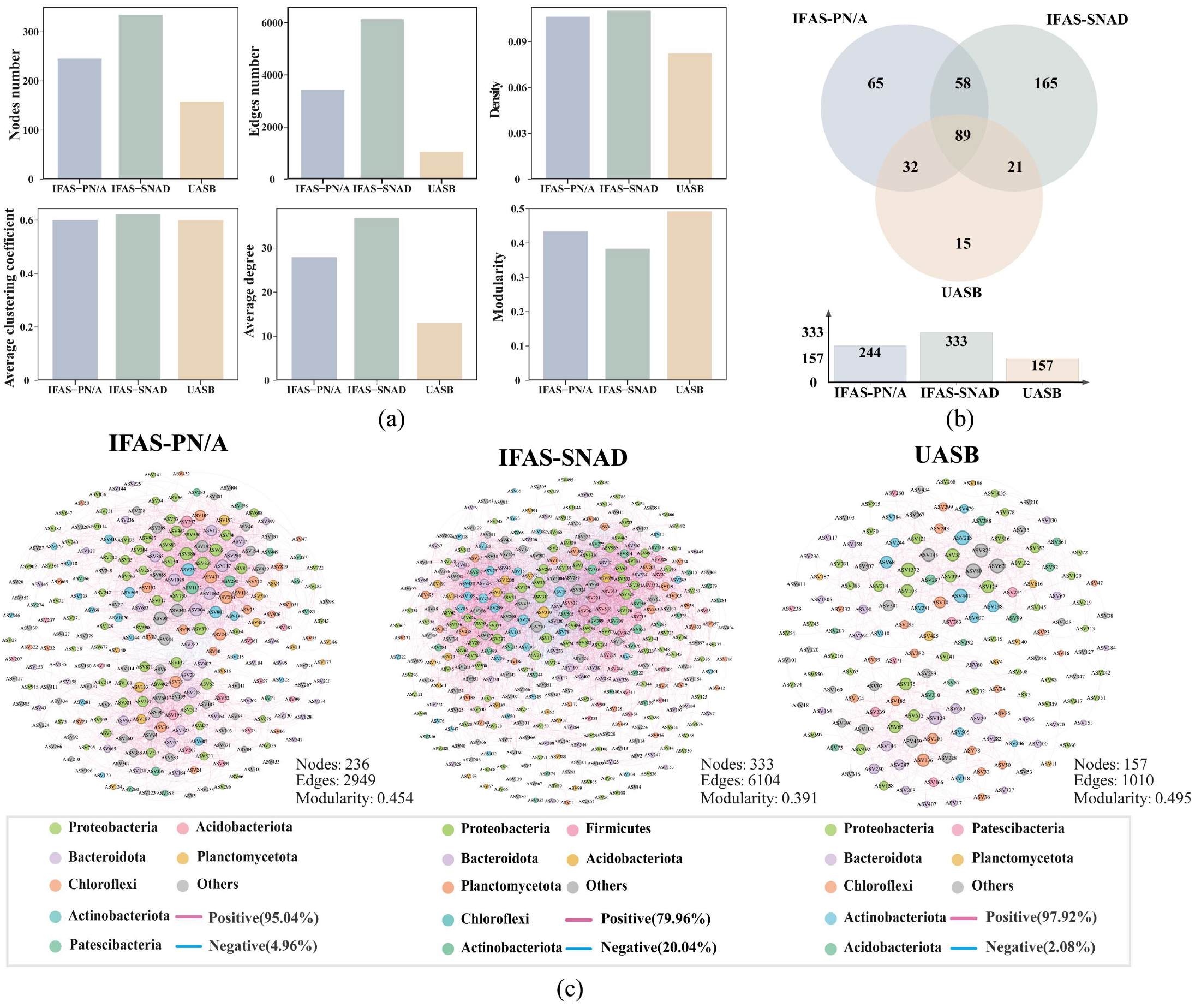

3.3.1. Network Topological Features

3.3.2. Network Structure in the Three Systems

3.4. The Prediction of the Impact of Environmental Factors on NRR Using ML

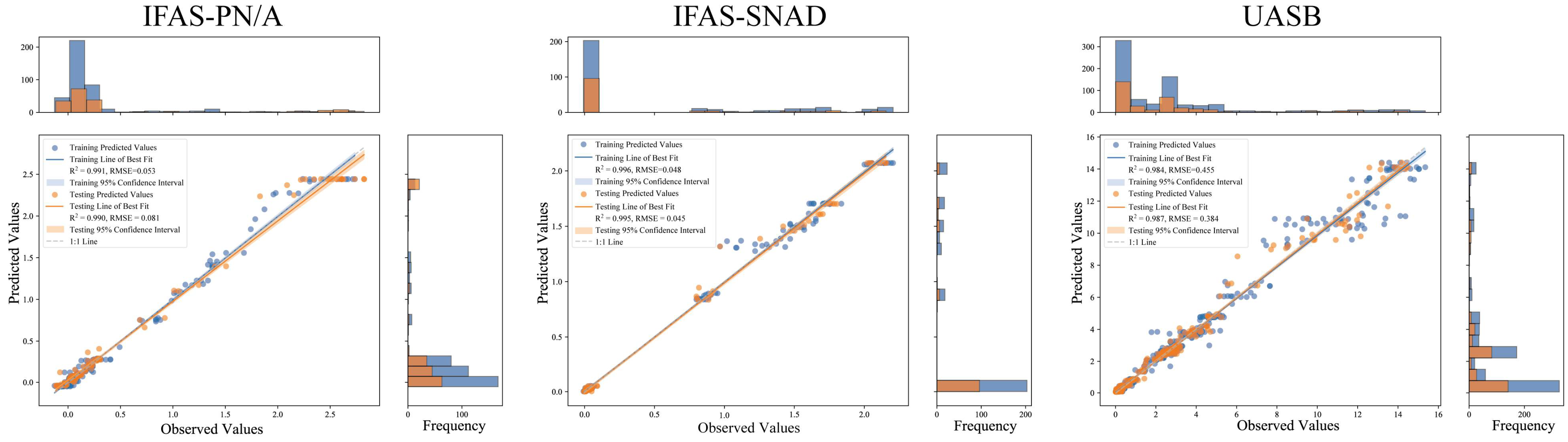

3.4.1. Evaluation of Model Performance

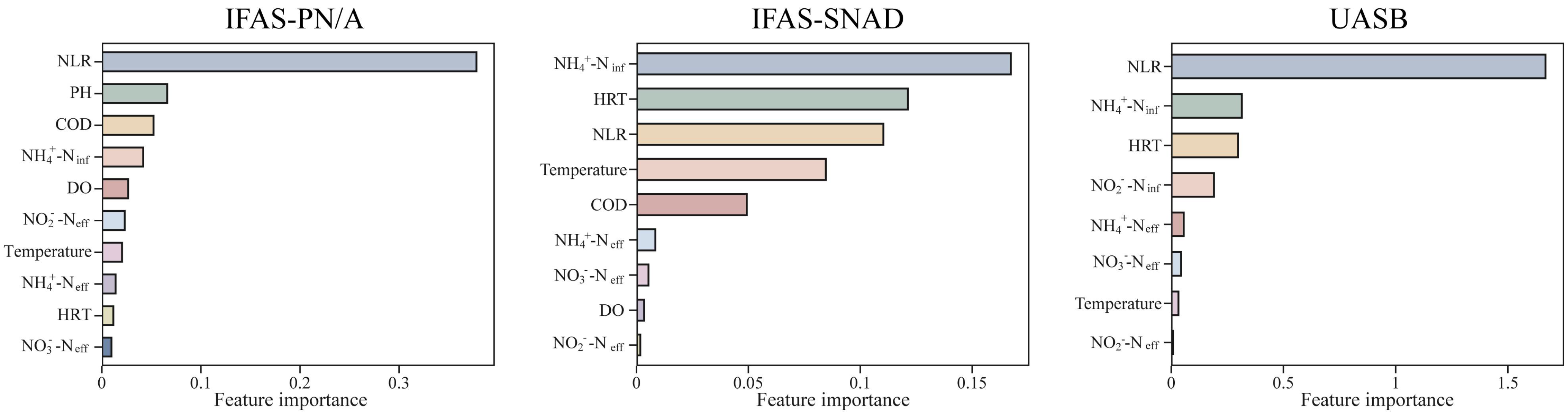

3.4.2. Identification of Key Environmental Factors

3.5. Impacts of Environmental Factors on Bacterial Communities

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| Anammox | Anaerobic ammonia oxidation |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium nitrogen |

| NO2−-N | Nitrite nitrogen |

| N2 | Nitrogen gas |

| IFAS | Integrated fixed-film activated sludge |

| PN/A | Partial nitritation/anammox |

| SNAD | Simultaneous nitrification, anammox, and denitrification |

| UASB | Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket |

| IFAS-PN/A | Integrated fixed-film activated sludge-partial nitritation/anammox |

| IFAS-SNAD | Integrated fixed-film activated sludge-simultaneous nitrification, anammox, and denitrification |

| ML | Machine learning |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variant |

| AnAOB | Anammox bacteria |

| AOB | Ammonium-oxidizing bacteria |

| NOB | Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| LGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| RF | Random Forest |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| CatBoost | Categorical Boosting |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machine |

| ST-XG | Stacked-XGBoost |

| ST-RF | Stacked-RF |

| NRR | Nitrogen Removal Rate |

| NLR | Nitrogen Loading Rate |

| NRE | Nitrogen removal efficiency |

| R2 | Determination coefficients |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| avgK | Average degree |

| avgCC | Average clustering coefficient |

References

- Adams, M.; Issaka, E.; Chen, C. Anammox-Based Technologies: A Review of Recent Advances, Mechanism, and Bottlenecks. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 148, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, M.S.M.; Wagner, M.; Fuerst, J.; Van Loosdrecht, M.; Kuenen, G.; Strous, M. Microbiology and Application of the Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation (‘Anammox’) Process. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2001, 12, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, S.; Gilbert, E.M.; Vlaeminck, S.E.; Joss, A.; Horn, H.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Full-Scale Partial Nitritation/Anammox Experiences–an Application Survey. Water Res. 2014, 55, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terada, A.; Zhou, S.; Hosomi, M. Presence and Detection of Anaerobic Ammonium-Oxidizing (Anammox) Bacteria and Appraisal of Anammox Process for High-Strength Nitrogenous Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2011, 13, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenen, J.G. Anammox and Beyond. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Yusof, N.; Mohd Yusoff, M.Z.; Hassan, M.A. Enrichment of Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation (Anammox) Bacteria for Short Start-up of the Anammox Process: A Review. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 13958–13978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strous, M.; Heijnen, J.J.; Kuenen, J.G.; Jetten, M.S.M. The Sequencing Batch Reactor as a Powerful Tool for the Study of Slowly Growing Anaerobic Ammonium-Oxidizing Microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1998, 50, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, M.S.M.; Strous, M.; Van De Pas-Schoonen, K.T.; Schalk, J.; Van Dongen, U.G.J.M.; Van De Graaf, A.A.; Logemann, S.; Muyzer, G.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Kuenen, J.G. The Anaerobic Oxidation of Ammonium. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 22, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahiman, S.; Qiblawey, H. Anammox-MBR Technology: Breakthroughs and Challenges in Sustainable Nitrogen Removal from Wastewater. Membranes 2025, 15, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureni, M.; Weissbrodt, D.G.; Villez, K.; Robin, O.; De Jonge, N.; Rosenthal, A.; Wells, G.; Nielsen, J.L.; Morgenroth, E.; Joss, A. Biomass Segregation between Biofilm and Flocs Improves the Control of Nitrite-Oxidizing Bacteria in Mainstream Partial Nitritation and Anammox Processes. Water Res. 2019, 154, 104–116, Erratum in Water Res. 2020, 169, 115133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeminck, S.E.; Terada, A.; Smets, B.F.; De Clippeleir, H.; Schaubroeck, T.; Bolca, S.; Demeestere, L.; Mast, J.; Boon, N.; Carballa, M.; et al. Aggregate Size and Architecture Determine Microbial Activity Balance for One-Stage Partial Nitritation and Anammox. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Autotrophic Nitrogen Removal in an Integrated Fixed-Biofilm Activated Sludge (IFAS) Reactor: Anammox Bacteria Enriched in the Flocs Have Been Overlooked. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, J. Synergistic Membrane-Biofilm-Sludge System Coupling Partial Nitritation and Anammox: Achieving Efficient Nitrogen Removal in High-Ammonia/Low-Carbon Condensate Wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 434, 132819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.; Yang, F. Achieving Mainstream Nitrogen Removal through Simultaneous Partial Nitrification, Anammox and Denitrification Process in an Integrated Fixed Film Activated Sludge Reactor. Chemosphere 2018, 203, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Yu, D.; Wang, X.; Zhen, J.; Bi, C.; Gong, X.; Zhao, J. Achieving Simultaneous Nitritation, Anammox and Denitrification (SNAD) in an Integrated Fixed-Biofilm Activated Sludge (IFAS) Reactor: Quickly Culturing Self-Generated Anammox Bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Gan, Y.; Chang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhu, G. Performance of Anammox UASB Reactor Treating Low Strength Wastewater under Moderate and Low Temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 129, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.J.; Zheng, P.; Wang, C.H.; Mahmood, Q.; Zhang, J.Q.; Chen, X.G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.W. Performance of High-Loaded ANAMMOX UASB Reactors Containing Granular Sludge. Water Res. 2011, 45, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Xie, J.; Kabore, A.W.J.; Chang, Y.; Xie, J.; Guo, M.; Chen, C. Research Advances in Anammox Granular Sludge: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 631–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abma, W.R.; Schultz, C.E.; Mulder, J.W.; Van Der Star, W.R.L.; Strous, M.; Tokutomi, T.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Full-Scale Granular Sludge Anammox Process. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yao, J.; Jia, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y. Initiation of Anammox in an Up-Flow Anaerobic Sludge Bed Reactor: Bacterial Community Structure, Nitrogen Removal Functional Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Water 2024, 16, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, V.; Ying, L.; Asghari, V.; Hsu, S.-C.; Lee, P.-H. Modeling of a Mainstream Partial Nitrification/Anammox Process through a Hybrid Theoretical-Machine Learning Approach. ACS EST Water 2025, 5, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Du, T.; Guo, D.; Jiang, X.; Zeng, M.; Wu, N.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z. Deciphering and Predicting Anammox-Based Nitrogen Removal Process under Oxytetracycline Stress via Kinetic Modeling and Machine Learning Based on Big Data Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, S. Elucidating Nitrogen Removal Performance and Response Mechanisms of Anammox under Heavy Metal Stress Using Big Data Analysis and Machine Learning. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 382, 129143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wei, C. Machine Learning Modeling for the Prediction of Phosphorus and Nitrogen Removal Efficiency and Screening of Crucial Microorganisms in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Jia, F.; Qiu, S.; Li, Y.; Mei, N.; Zhao, X.; Han, B.; Han, X.; Zhang, J.; Yao, H. Predicting and Interpreting Nitrogen Removal Performance and Functional Microbial Abundance of Single-Stage Partial Nitrification and Anammox System Using Machine Learning Methods. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 437, 133119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H. Stacked Generalization. Neural Netw. 1992, 5, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achraf, R.; Mounir, M.; Moussa, S.M. A New Framework for Energy-Optimized Biological Treatment in Wastewater Treatment Plants Using Machine Learning Techniques. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 517, 145854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.S.; Emanuel, R.E. How Are Streamflow Responses to the E l N Ino S Outhern O Scillation Affected by Watershed Characteristics? Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 4393–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, R.; Orak, C. Stacked Machine Learning Approach for Predicting Evolved Hydrogen from Sugar Industry Wastewater. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 85, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüftinger, L.; Májek, P.; Beisken, S.; Rattei, T.; Posch, A.E. Learning from Limited Data: Towards Best Practice Techniques for Antimicrobial Resistance Prediction from Whole Genome Sequencing Data. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 610348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Bourexis, D.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Comeau, D.C.; Funk, K.; Kim, S.; Klimke, W.; et al. Database Resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D10–D17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, S.; Liu, X.; Yao, P.; Ge, T.; Zhang, X.-H. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Archaeal Community in Coastal Sediments: Assembly Process and Co-Occurrence Relationship. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1463–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, A.I.; Balzer, L.B. Stacked Generalization: An Introduction to Super Learning. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstajic, D.; Buturovic, L.J.; Leahy, D.E.; Thomas, S. Cross-Validation Pitfalls When Selecting and Assessing Regression and Classification Models. J. Cheminform. 2014, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, G.C.; Talbot, N.L.C. On Over-Fitting in Model Selection and Subsequent Selection Bias in Performance Evaluation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2010, 11, 2079–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Raschka, S. Model Evaluation, Model Selection, and Algorithm Selection in Machine Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1811.12808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, D.R.; In ’T Zandt, M.H.; Guerrero-Cruz, S.; Dutilh, B.E.; Jetten, M.S.M. Genome-Based Microbial Ecology of Anammox Granules in a Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment System. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraga, R.; Galan, A.; Rossello-Mora, R.; Araya, R.; Valdés, J. Composición de la comunidad procariota involucrada en la producción de nitrógeno en sedimentos de la bahía mejillones. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2014, 49, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Qing, X.; He, Q. A Novel Process Combining Simultaneous Partial Nitrification, Anammox and Denitrification (SNAD) with Denitrifying Phosphorus Removal (DPR) to Treat Sewage. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 222, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.; Jurnalis, A.; Denecke, M. The Influence of Aeration Control and Temperature Reduction on Nitrogen Removal and Microbial Community in Two Anammox-based Hybrid Sequencing Batch Biofilm Reactors. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 3358–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovio-Winkler, P.; Guerrero, L.D.; Erijman, L.; Oyarzúa, P.; Suárez-Ojeda, M.E.; Cabezas, A.; Etchebehere, C. Genome-Centric Metagenomic Insights into the Role of Chloroflexi in Anammox, Activated Sludge and Methanogenic Reactors. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardanov, A.V.; Beletsky, A.V.; Ravin, N.V.; Botchkova, E.A.; Litti, Y.V.; Nozhevnikova, A.N. Genome of a Novel Bacterium “Candidatus Jettenia Ecosi” Reconstructed from the Metagenome of an Anammox Bioreactor. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botchkova, E.A.; Litti, Y.V.; Kuznetsov, B.B.; Nozhevnikova, A.N. Microbial Biofilms Formed in a Laboratory-Scale Anammox Bioreactor with Flexible Brush Carrier. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnology 2014, 5, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindaichi, T.; Yuri, S.; Ozaki, N.; Ohashi, A. Ecophysiological Role and Function of Uncultured Chloroflexi in an Anammox Reactor. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 66, 2556–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Yun, W.; Choi, Y.; Jung, J.; Park, S.; Ju, D.; Bae, H. Insights into Thiosulfate-Driven Partial Denitrification Synergistically Mediated by Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation: Biosynthesized Signaling Molecules and Enzymatic Collaboration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.; Zhang, T.; Liu, L.-H.; Fang, H.H.P. Microbial Community and Biochemistry Process in Autosulfurotrophic Denitrifying Biofilm. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücker, S.; Wagner, M.; Maixner, F.; Pelletier, E.; Koch, H.; Vacherie, B.; Rattei, T.; Damsté, J.S.S.; Spieck, E.; Le Paslier, D.; et al. A Nitrospira Metagenome Illuminates the Physiology and Evolution of Globally Important Nitrite-Oxidizing Bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13479–13484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, W.; He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, Z.; Zeng, M.; Wu, N. A Comprehensive Analysis of Microbial Community Differences in Four Morphologies of Mainstream Anaerobic Ammonia Oxidation Systems Using Big-Data Mining and Machine Learning. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1458853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinuevo, B.; Garcia, M.; Karakashev, D.; Angelidaki, I. Anammox for Ammonia Removal from Pig Manure Effluents: Effect of Organic Matter Content on Process Performance. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2171–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureni, M. Mainstream Partial Nitritation and Anammox: Long-Term Process Stability and Effluent Quality at Low Temperatures. Water Res. 2016, 101, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazmi, H.; Grubba, D.; Majtacz, J.; Kowal, P.; Makinia, J. Evaluation of Partial Nitritation/Anammox (PN/A) Process Performance and Microorganisms Community Composition under Different C/N Ratio. Water 2019, 11, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Niu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; He, S.; Li, Y.-Y. Substrate Inhibition and Concentration Control in an UASB-Anammox Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 238, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, D.; Zhang, J.; Miao, Y.; Ma, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhi, J.; Dong, G. Enhancing Nitrite Production Rate Made Anammox Bacteria Have a Competitive Advantage over Nitrite Oxidizing Bacteria in Mainstream Anammox System. Water Environ. Res. 2023, 95, e10878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q. Impact of COD/N on Anammox Granular Sludge with Different Biological Carriers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, B.; De Almeida, N.M.; Maalcke, W.J.; Op Den Camp, H.J.M.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Keltjens, J.T. How to Make a Living from Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 428–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L. Improving Stability of Mainstream Anammox in an Innovative Two-Stage Process for Advanced Nitrogen Removal from Mature Landfill Leachate. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Du, J.; Bian, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, B. Nitrogen Removal via Simultaneous Partial Nitrification, Anammox and Denitrification (SNAD) Process under High DO Condition. Biodegradation 2016, 27, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, B.; Kuypers, M.M.M.; Lavik, G.; Schalk, J.; Op Den Camp, H.J.M.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Strous, M. Anammox Bacteria Disguised as Denitrifiers: Nitrate Reduction to Dinitrogen Gas via Nitrite and Ammonium. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Lee, H.H.; Chung, Y.C.; Jung, J.Y. High-Strength Nitrogenous Wastewater Treatment in Biofilm and Granule Anammox Processes. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2365–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. Carrier Type Induces Anammox Biofilm Structure and the Nitrogen Removal Pathway: Demonstration in a Full-Scale Partial Nitritation/Anammox Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 334, 125249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Y. Full-Scale Partial Nitritation/Anammox (PN/A) Process for Treating Sludge Dewatering Liquor from Anaerobic Digestion after Thermal Hydrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, L. Enhancing Anammox Bacteria Enrichment in Integrated Fixed-Film Activated Sludge Partial Nitritation/Anammox Process via Floc Retention Control. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 391, 129938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, B.; Peng, Y. Achieve Efficient Nitrogen Removal from Real Sewage in a Plug-Flow Integrated Fixed-Film Activated Sludge (IFAS) Reactor via Partial Nitritation/Anammox Pathway. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y. Efficient Nitrogen Removal from Mature Landfill Leachate in a Step Feed Continuous Plug-Flow System Based on One-Stage Anammox Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shen, C.; Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Hao, S.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. Achieving Stable Mainstream Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal Assisted by Hydroxylamine Addition in a Continuous Partial Nitritation/Anammox Process from Real Sewage. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roots, P.; Rosenthal, A.F.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Kozak, J.A.; Zhang, H.; Wells, G.F. Optimization of the Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio for Mainstream Deammonification and the Resulting Shift in Nitrification from Biofilm to Suspension. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 3415–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Jiang, B.; Song, Z.; Ma, Y. Symbiotic Relationship Analysis of Predominant Bacteria in a Lab-Scale Anammox UASB Bioreactor. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 7615–7626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Lei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wan, X.; Yang, B.; Pan, X. Fast Start-up and Reactivation of Anammox Process Using Polyurethane Sponge. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 177, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, T.; Huang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Hai, R.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Functional Stability Correlates with Dynamic Microbial Networks in Anammox Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 370, 128557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Peng, Y. Establishing a Two-Stage System to Efficiently Treat Real Domestic Sewage by Partial Nitrification-SBR and Air-Lift Anammox-UASB: Reactivating and Enhancing Anammox Bacteria to Optimize the Nitrogen Removal Performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Peng, Y. Enrichment of Anammox Biomass during Mainstream Wastewater Treatment Driven by Achievement of Partial Denitrification through the Addition of Bio-Carriers. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 137, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Du, R.; Li, B.; Ren, N.; Peng, Y. High-Throughput Profiling of Microbial Community Structures in an ANAMMOX-UASB Reactor Treating High-Strength Wastewater. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 6457–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-X.; Liao, Q.; Yu, C.; Xiao, R.; Tang, C.-J.; Chai, L.-Y.; Duan, C.-S. Physicochemical and Microbial Properties of Settled and Floating Anammox Granules in Upflow Reactor. Biochem. Eng. J. 2017, 123, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Dang, H.; Zou, X.; Yu, N.; Guo, H.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Y. Deciphering the Role of Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) in Anammox: Effects on Microbial Succession and Communication. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, F.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Yao, H. Metagenomic Prediction Analysis of Microbial Aggregation in Anammox-dominated Community. Water Environ. Res. 2021, 93, 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Training Dataset | Testing Dataset | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | R2 | MAE | RMSE | R2 | MAE | RMSE | |

| IFAS-PN/A | AdaBoost | 0.986 | 0.046 | 0.065 | 0.988 | 0.060 | 0.090 |

| CatBoost | 0.876 | 0.118 | 0.194 | 0.843 | 0.186 | 0.325 | |

| LGBM | 0.895 | 0.088 | 0.179 | 0.848 | 0.160 | 0.319 | |

| GBM | 0.794 | 0.150 | 0.250 | 0.787 | 0.217 | 0.378 | |

| SVR | 0.921 | 0.098 | 0.155 | 0.901 | 0.155 | 0.258 | |

| ST-RF | 0.991 | 0.028 | 0.053 | 0.990 | 0.042 | 0.081 | |

| ST-XGB | 0.991 | 0.027 | 0.050 | 0.989 | 0.040 | 0.100 | |

| IFAS-SNAD | AdaBoost | 0.994 | 0.028 | 0.058 | 0.993 | 0.026 | 0.056 |

| CatBoost | 0.903 | 0.173 | 0.230 | 0.903 | 0.159 | 0.206 | |

| LGBM | 0.937 | 0.153 | 0.186 | 0.935 | 0.140 | 0.169 | |

| GBM | 0.796 | 0.285 | 0.334 | 0.788 | 0.262 | 0.305 | |

| SVR | 0.974 | 0.093 | 0.119 | 0.969 | 0.092 | 0.116 | |

| ST-RF | 0.996 | 0.021 | 0.048 | 0.995 | 0.022 | 0.045 | |

| ST-XGB | 0.993 | 0.026 | 0.061 | 0.994 | 0.024 | 0.053 | |

| UASB | AdaBoost | 0.980 | 0.298 | 0.509 | 0.977 | 0.280 | 0.516 |

| CatBoost | 0.883 | 0.816 | 1.220 | 0.899 | 0.753 | 1.069 | |

| LGBM | 0.929 | 0.609 | 0.950 | 0.936 | 0.571 | 0.851 | |

| GBM | 0.781 | 1.140 | 1.669 | 0.795 | 1.061 | 1.527 | |

| SVR | 0.811 | 0.669 | 1.551 | 0.840 | 0.590 | 1.347 | |

| ST-RF | 0.984 | 0.222 | 0.455 | 0.987 | 0.198 | 0.384 | |

| ST-XGB | 0.979 | 0.239 | 0.520 | 0.981 | 0.222 | 0.468 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Ya, T.; Han, L.; Li, W. A Comprehensive Analysis of Microbial Community and Nitrogen Removal Rate Predictions in Three Anammox Systems. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2795. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122795

Zhang X, Ya T, Han L, Li W. A Comprehensive Analysis of Microbial Community and Nitrogen Removal Rate Predictions in Three Anammox Systems. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2795. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122795

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xuan, Tao Ya, Lu Han, and Weize Li. 2025. "A Comprehensive Analysis of Microbial Community and Nitrogen Removal Rate Predictions in Three Anammox Systems" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2795. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122795

APA StyleZhang, X., Ya, T., Han, L., & Li, W. (2025). A Comprehensive Analysis of Microbial Community and Nitrogen Removal Rate Predictions in Three Anammox Systems. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2795. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122795