Estradiol Modulates the Sensitivity to Vancomycin of Lactobacillus paracasei and Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms—Constituents of Human Skin and Vaginal Microbiota

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Storage

2.2. Active Compounds

2.3. Bacterial Cultures

2.4. Cultivation of Monospecies and Dual-Species Biofilms

2.4.1. Monospecies Biofilms on Polytetrafluoroethylene Cubes

2.4.2. Monospecies and Dual-Species Biofilms on Glass Fiber Filters

2.4.3. Monospecies and Dual-Species Biofilms in 24-Well Glass-Bottom Plates

2.4.4. Biofilms in 96-Well Polystyrene Microtiter Plates

2.4.5. Biofilms on Cellulose Filters

2.5. Staining of Biofilms with Crystal Violet

2.5.1. Biofilms on the PTFE Cubes

2.5.2. Biofilms in 96-Well Microtiter Plates

2.6. Counting of Colony-Forming Units in Biofilms on the Glass Fiber Filters

2.7. Assessment of Metabolic Activity in Biofilms on the Glass Fiber Filters

2.8. Fluorescent in Situ Hybridization

2.9. Confocal Microscopy of Biofilms

2.10. Antibacterial Activity Assay of S. aureus 209P and L. paracasei AK508

2.11. Isolation of L. paracasei Biofilm Matrix

2.12. Isolation and Analysis of L. paracasei Lipids

2.13. qPCR for Differential Expression of S. aureus Resistance Genes in Biofilms

2.14. Statistics

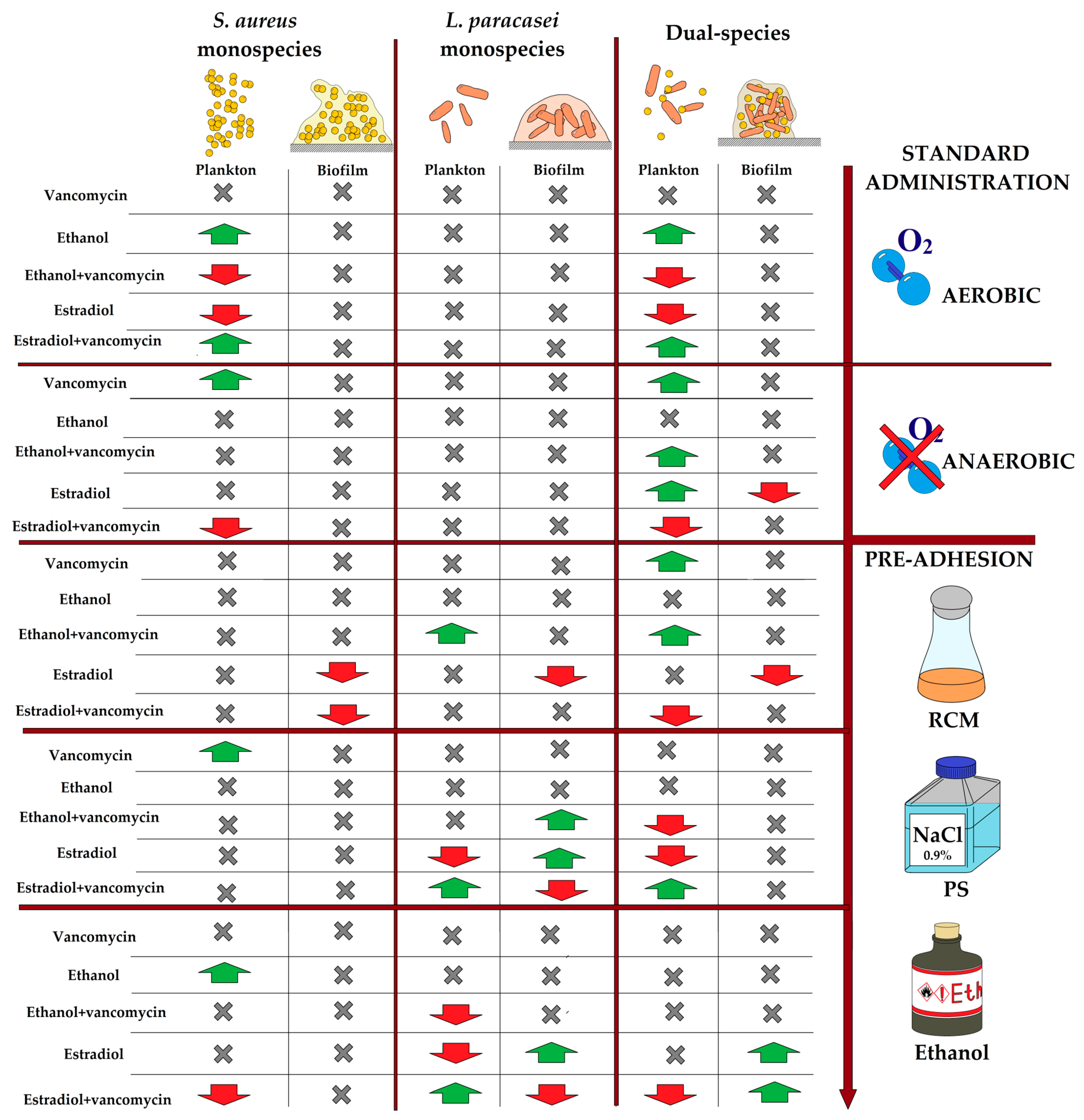

3. Results

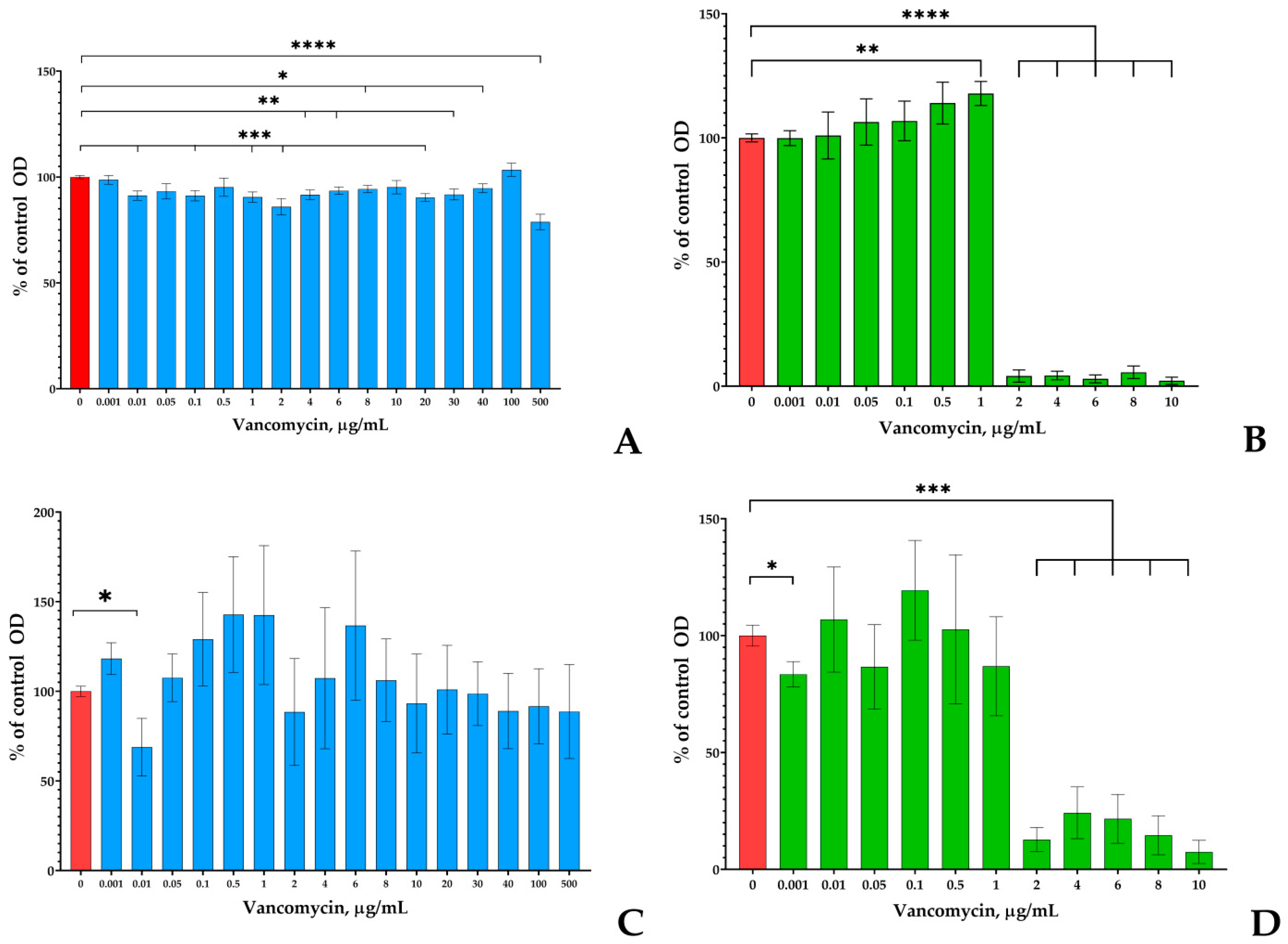

3.1. Screening of Vancomycin Effects on Monospecies Planktonic Cultures and Biofilms on PTFE Cubes

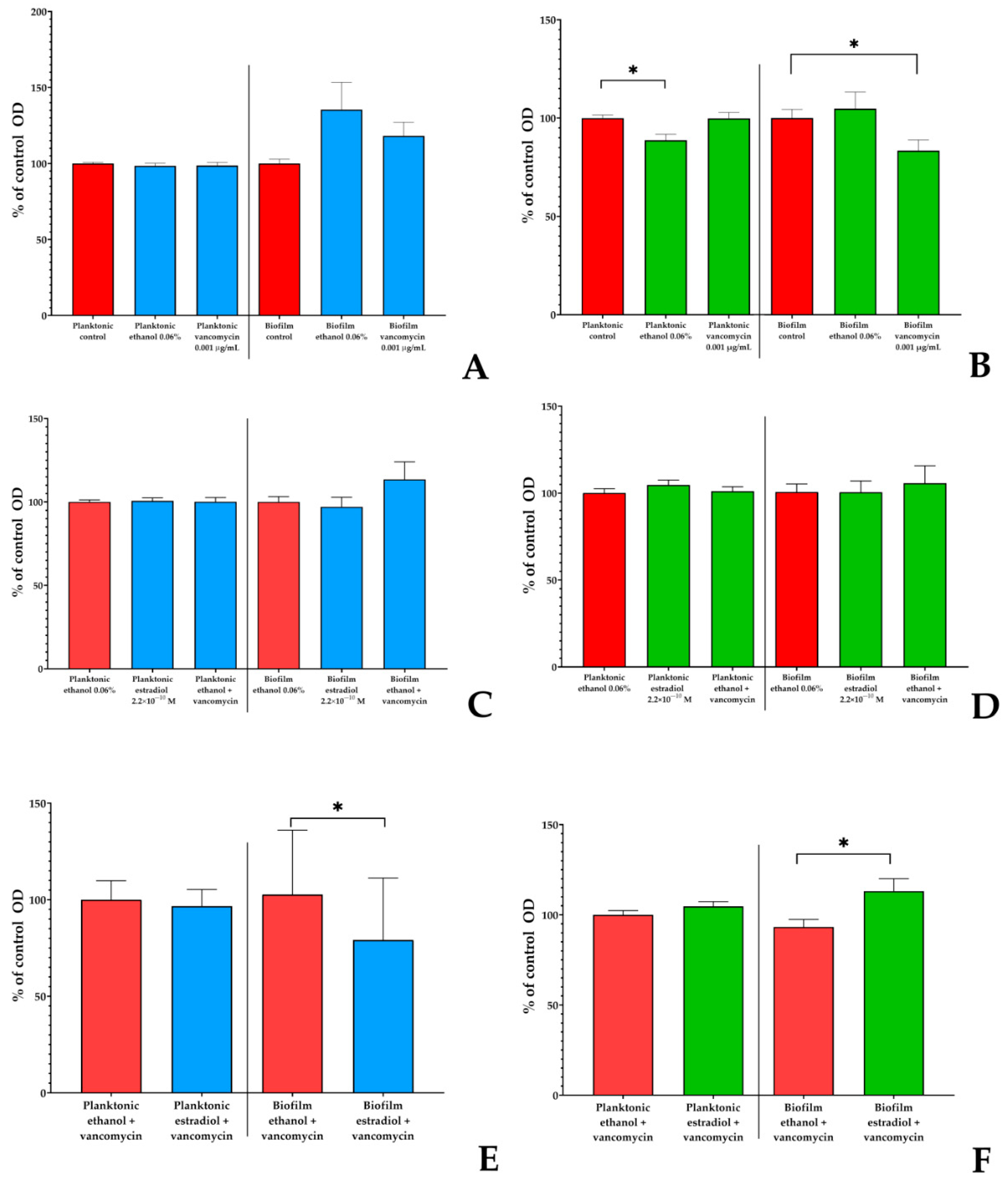

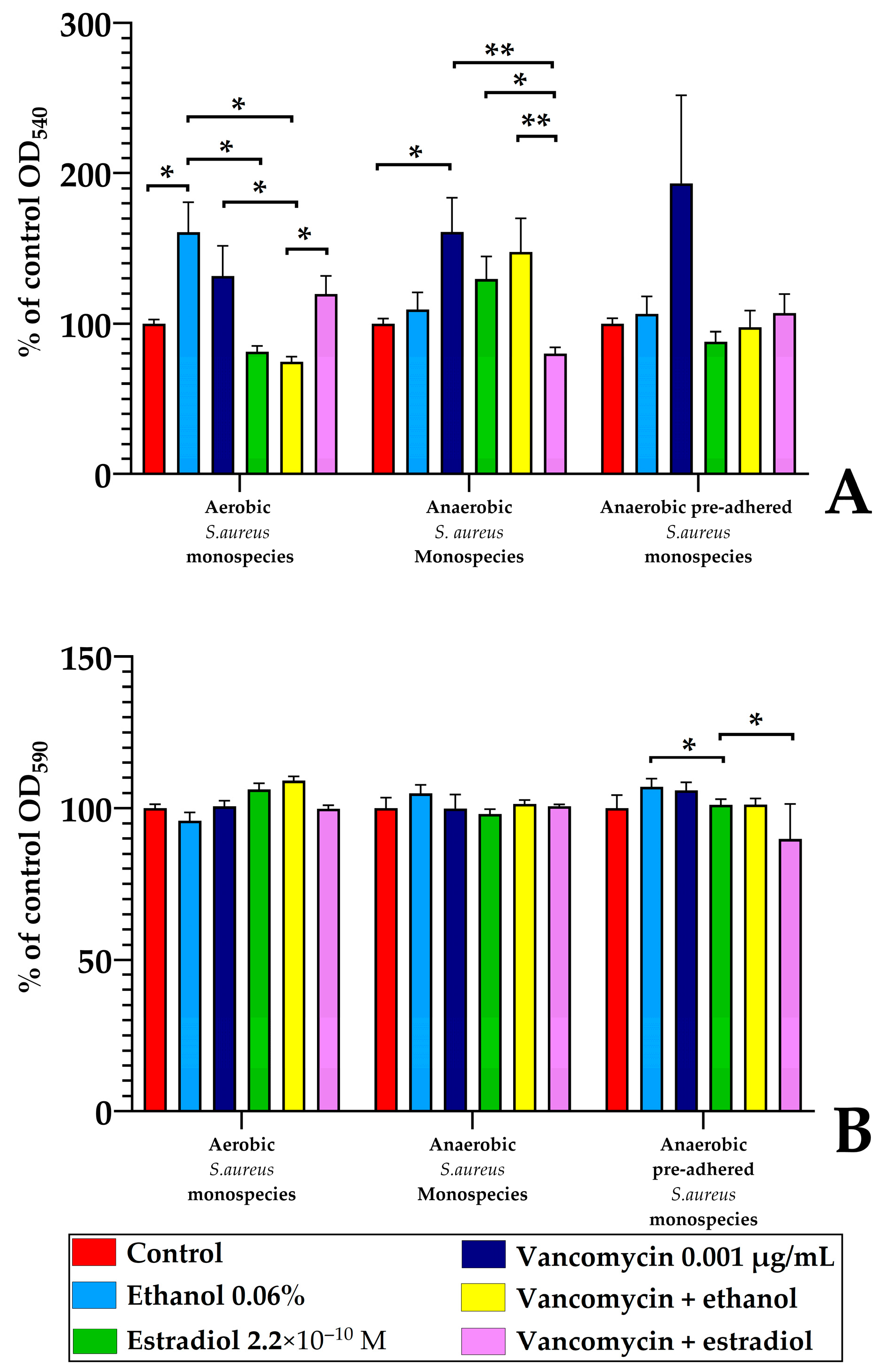

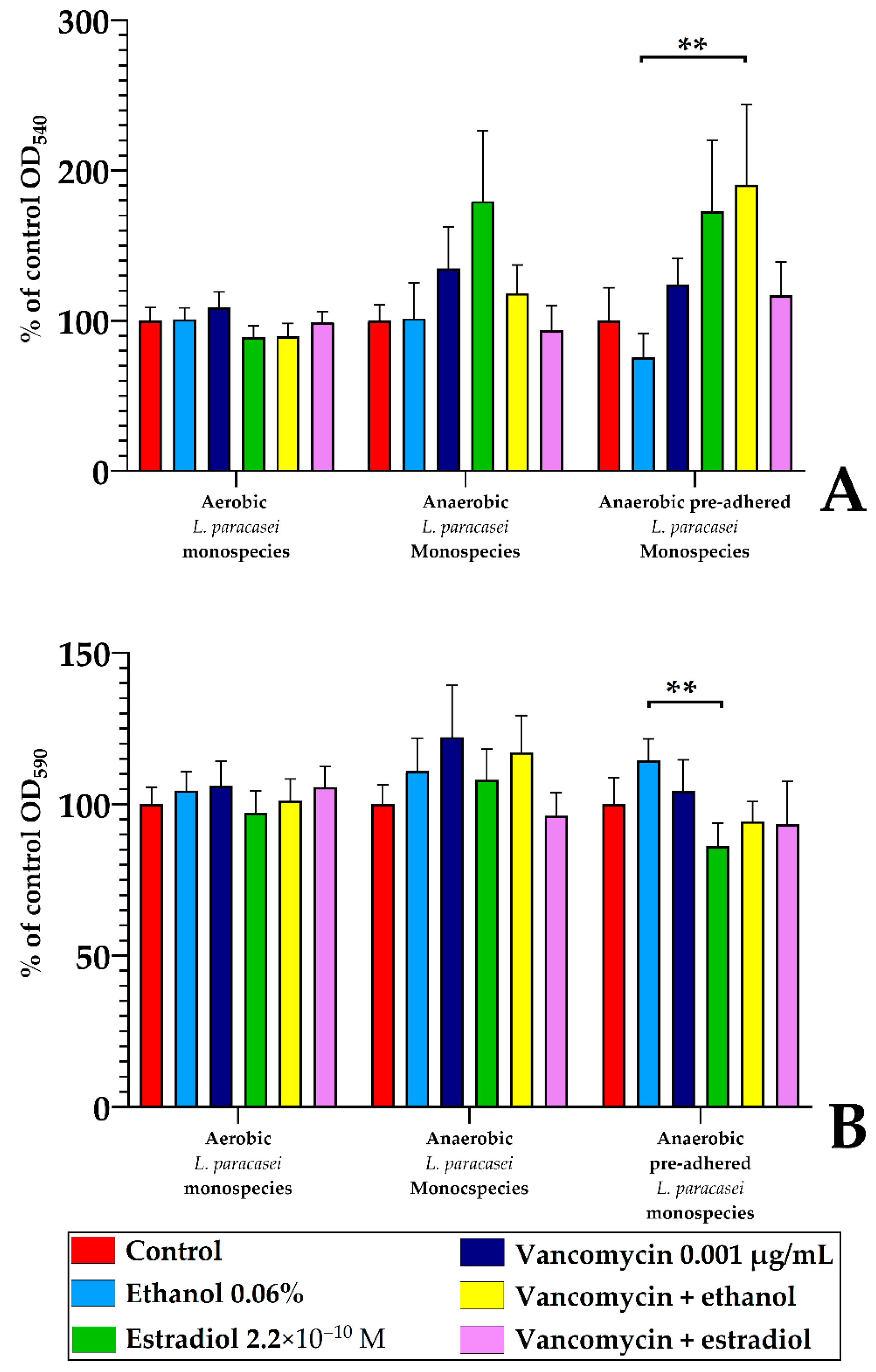

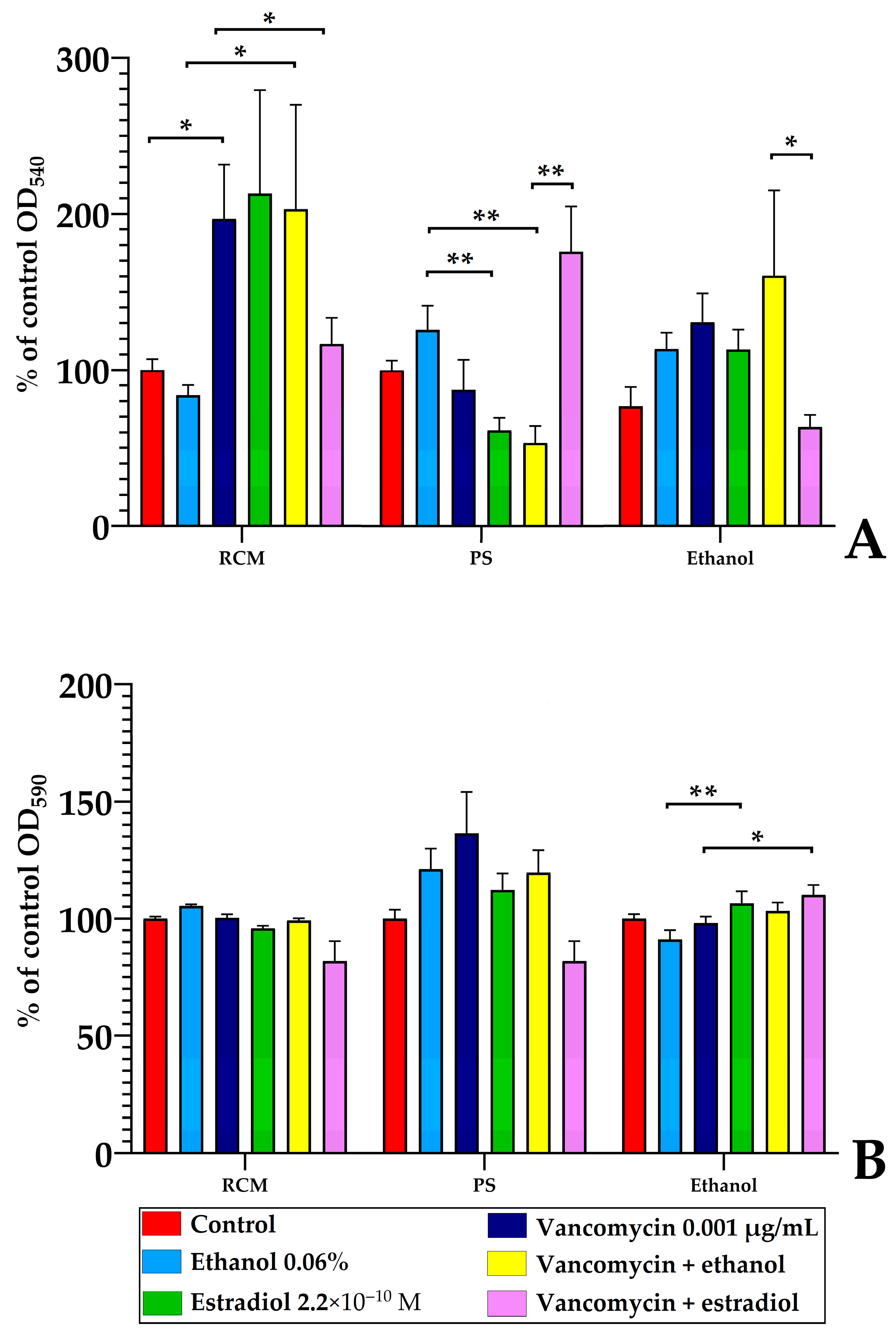

3.2. Estradiol Alters Vancomycin Effects on L. paracasei AK508 and S. aureus 209P in the PTFE-Cube System

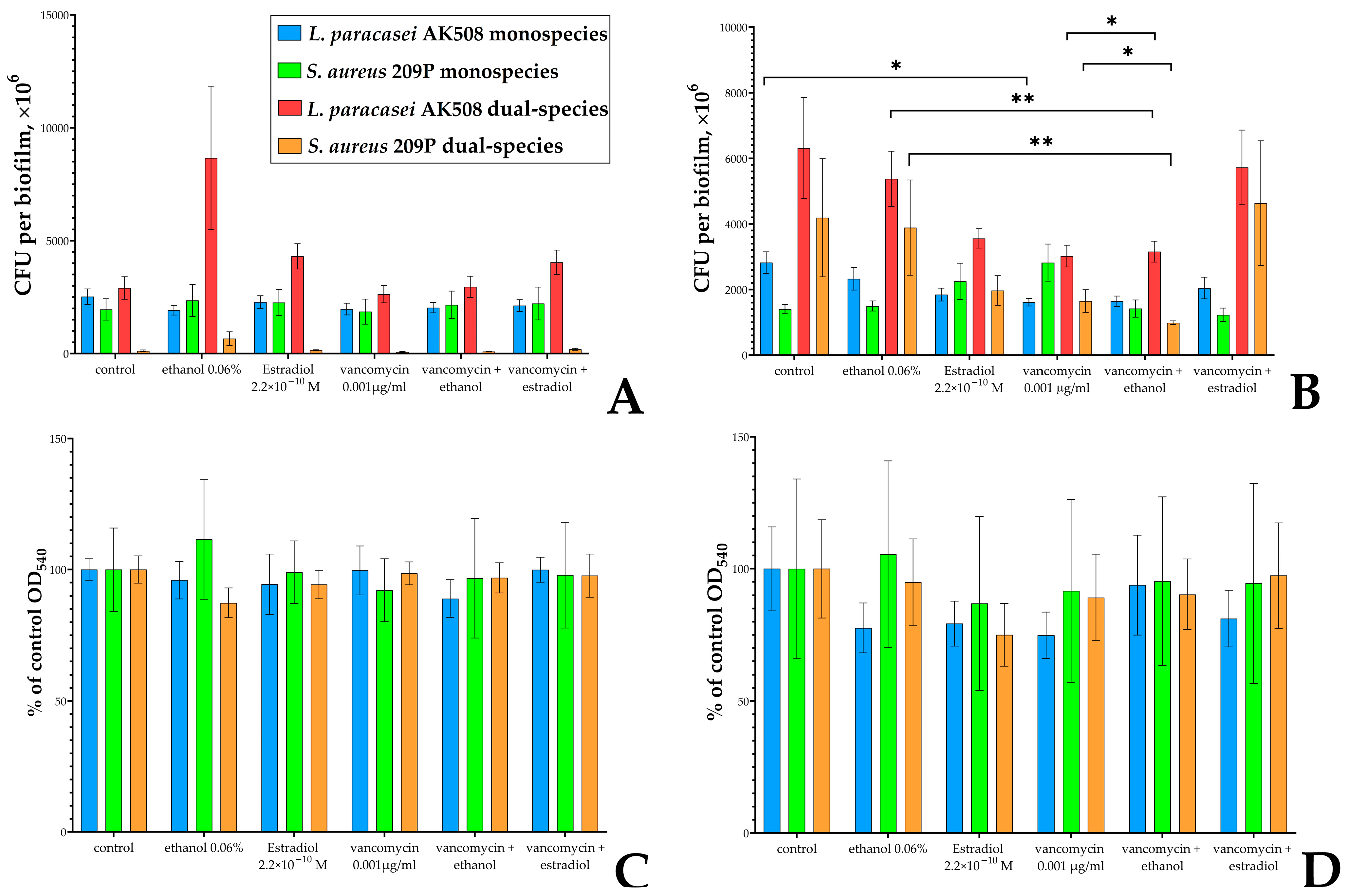

3.3. Estradiol Modulates Vancomycin Responses in S. aureus 209P and L. paracasei AK508 Biofilms on Glass Fiber Filters

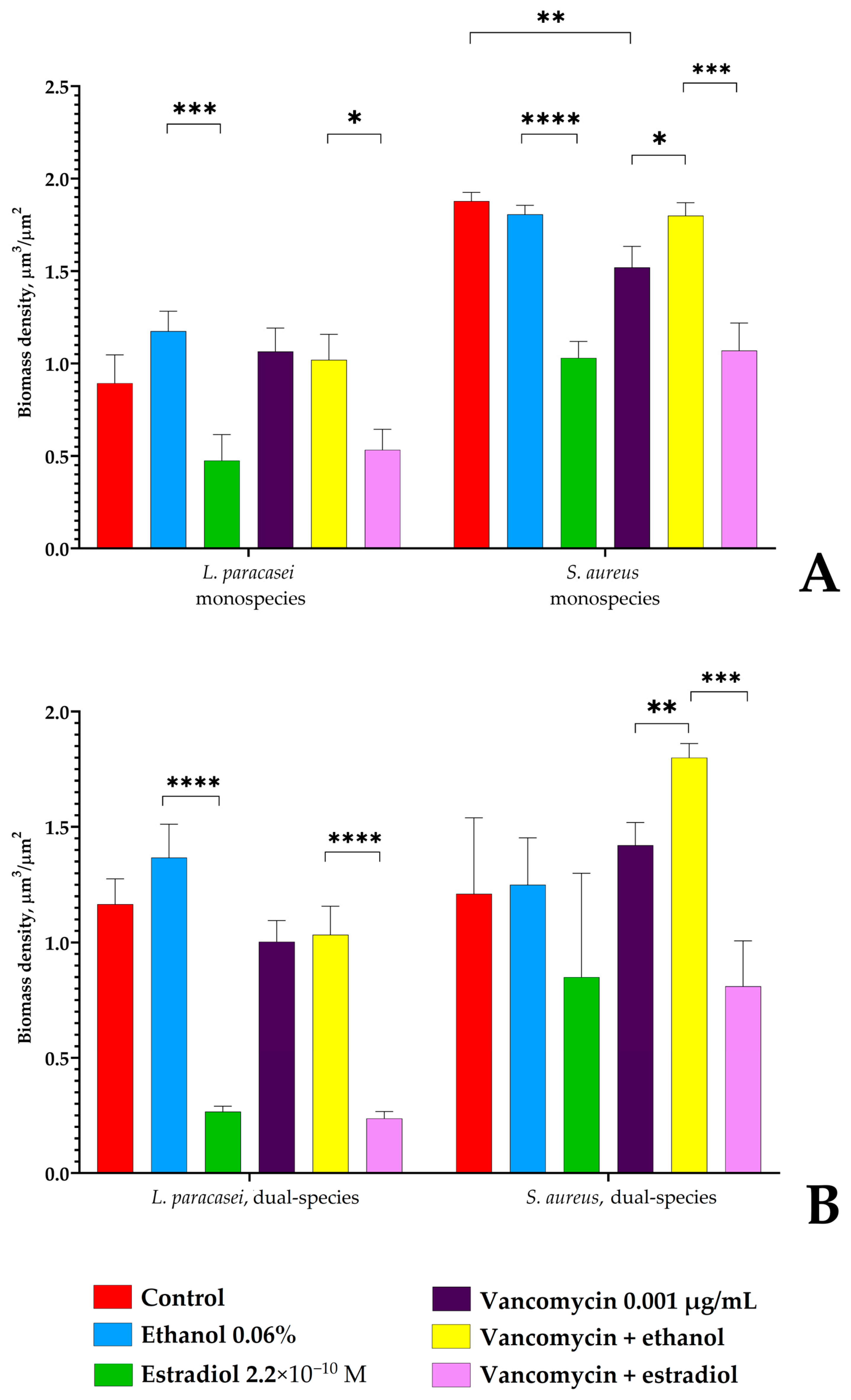

3.4. Confocal Microscopy of L. paracasei and S. aureus Biofilms

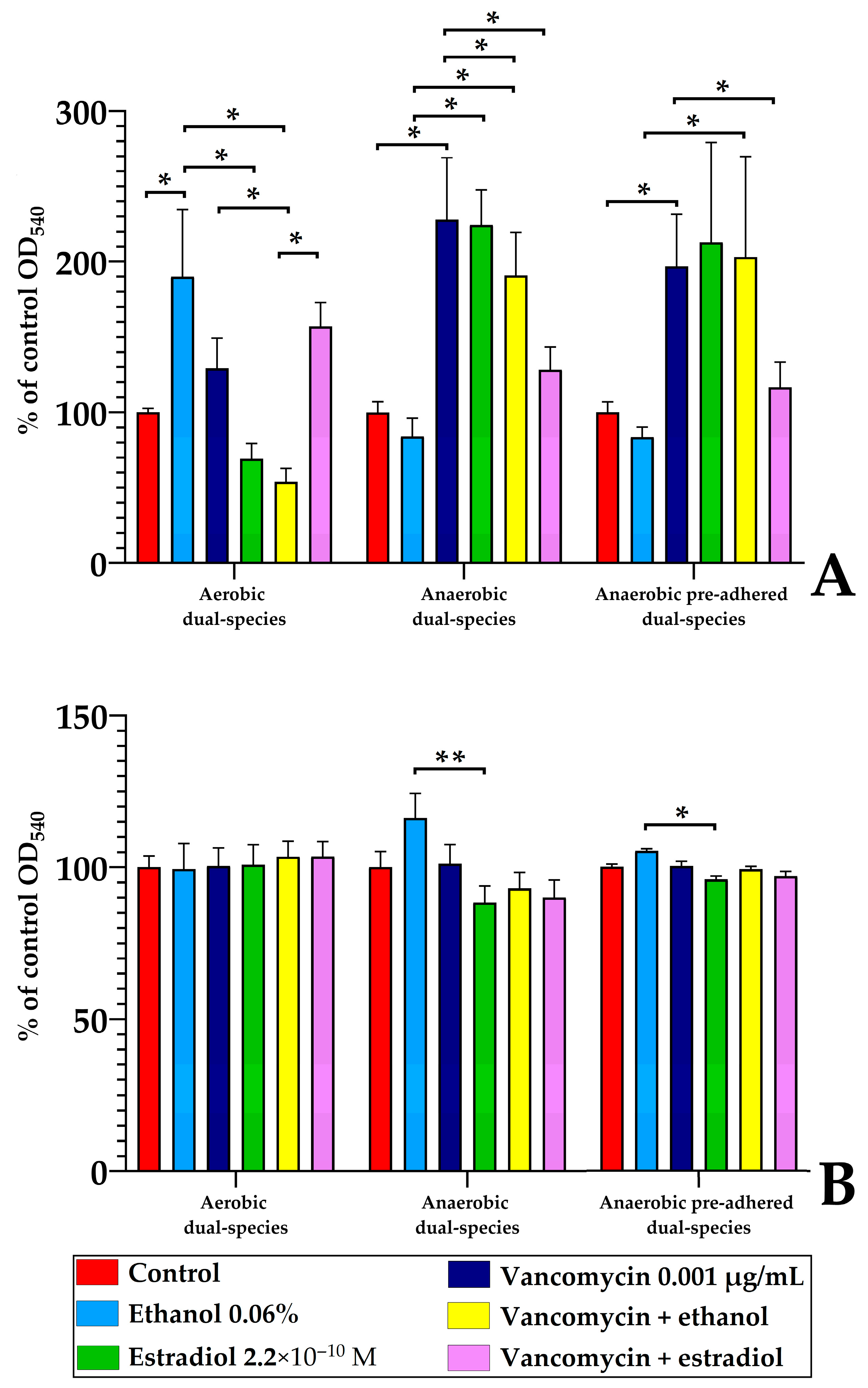

3.5. Monospecies and Dual-Species Biofilms in 96-Well Microtiter Plates

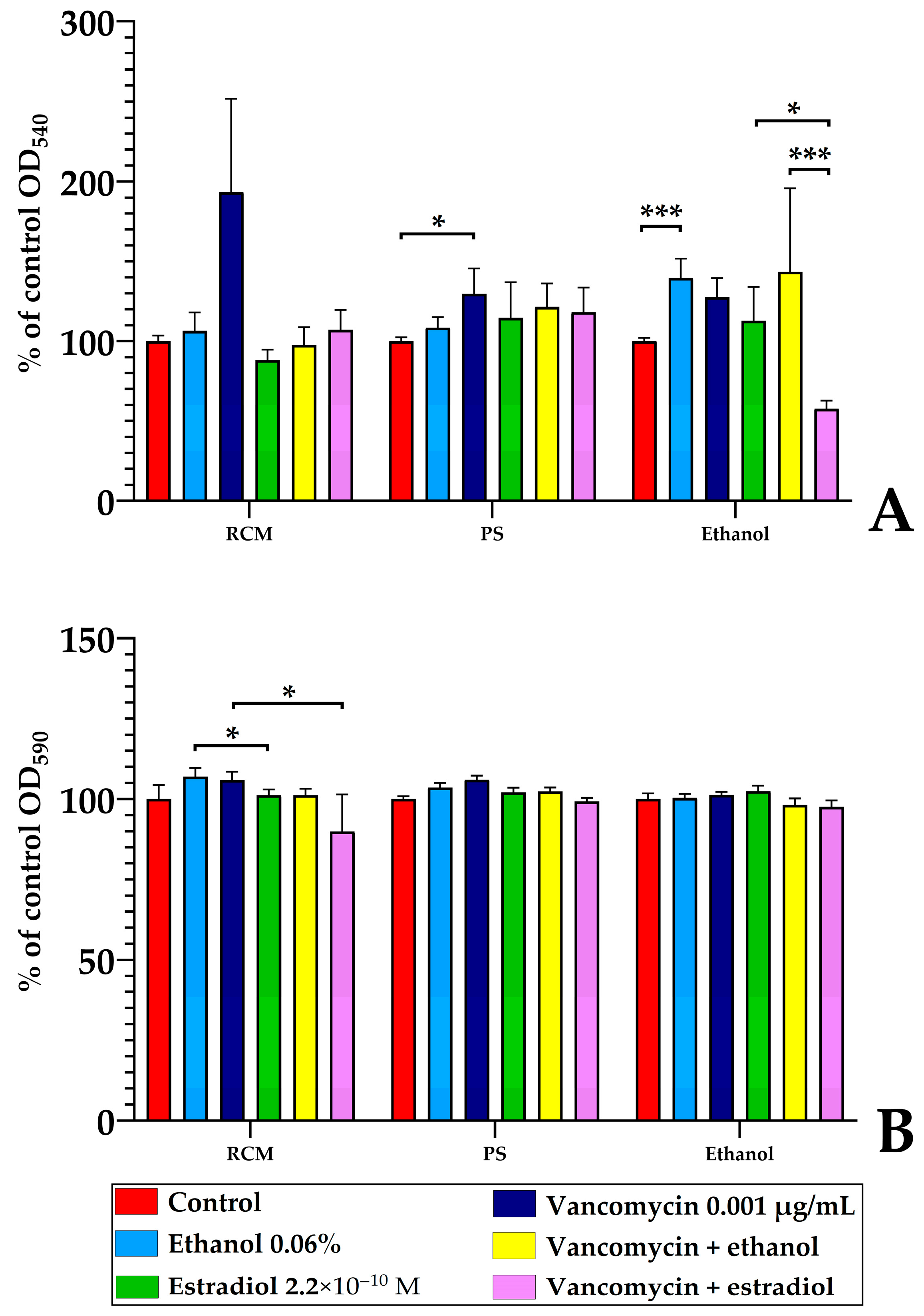

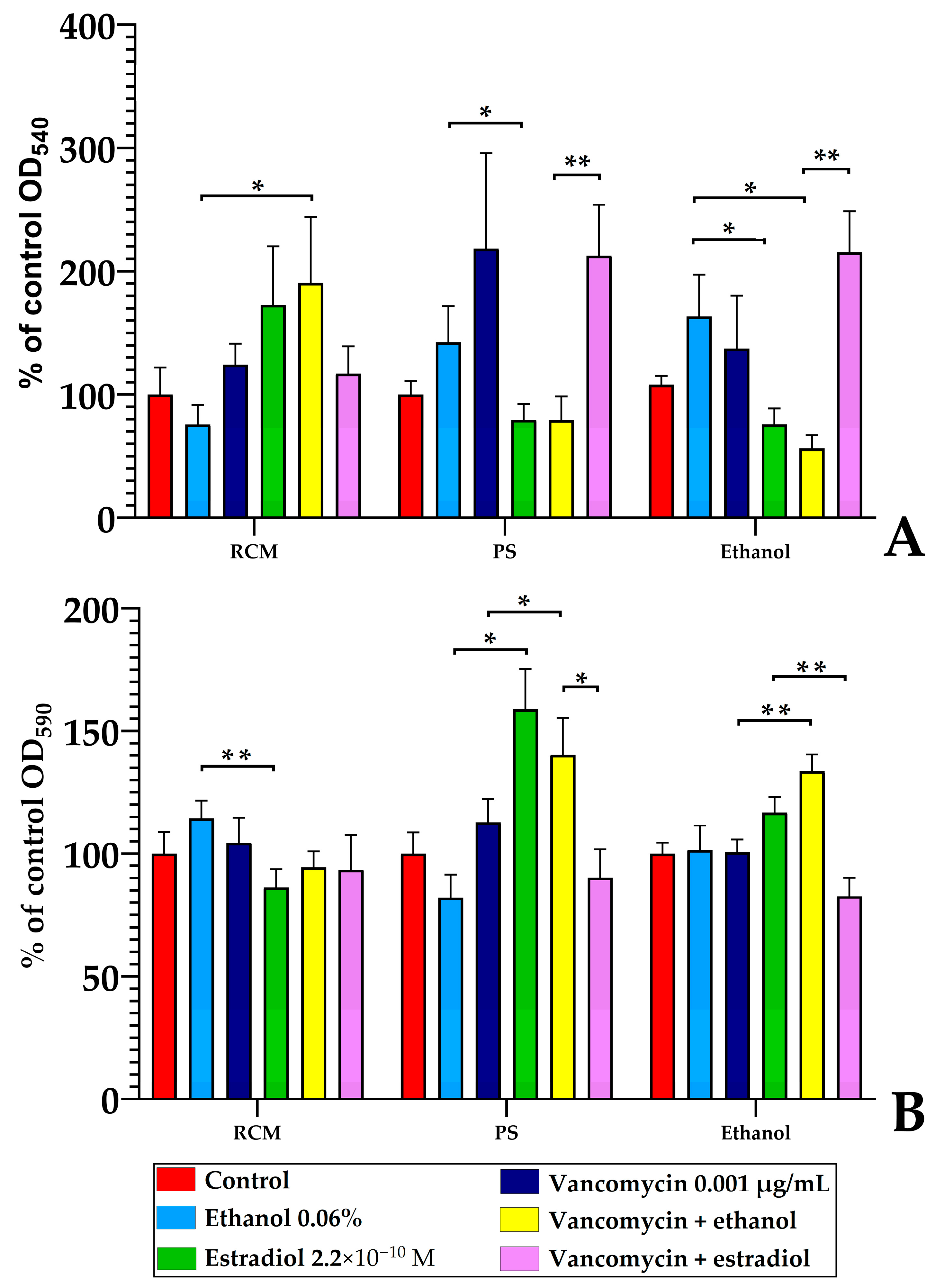

3.5.1. The Effect of Estradiol Absorbed on the Surface of Wells

3.5.2. The Nature of Estradiol Solvent Is Important for Estradiol Effects After Pre-Adhesion

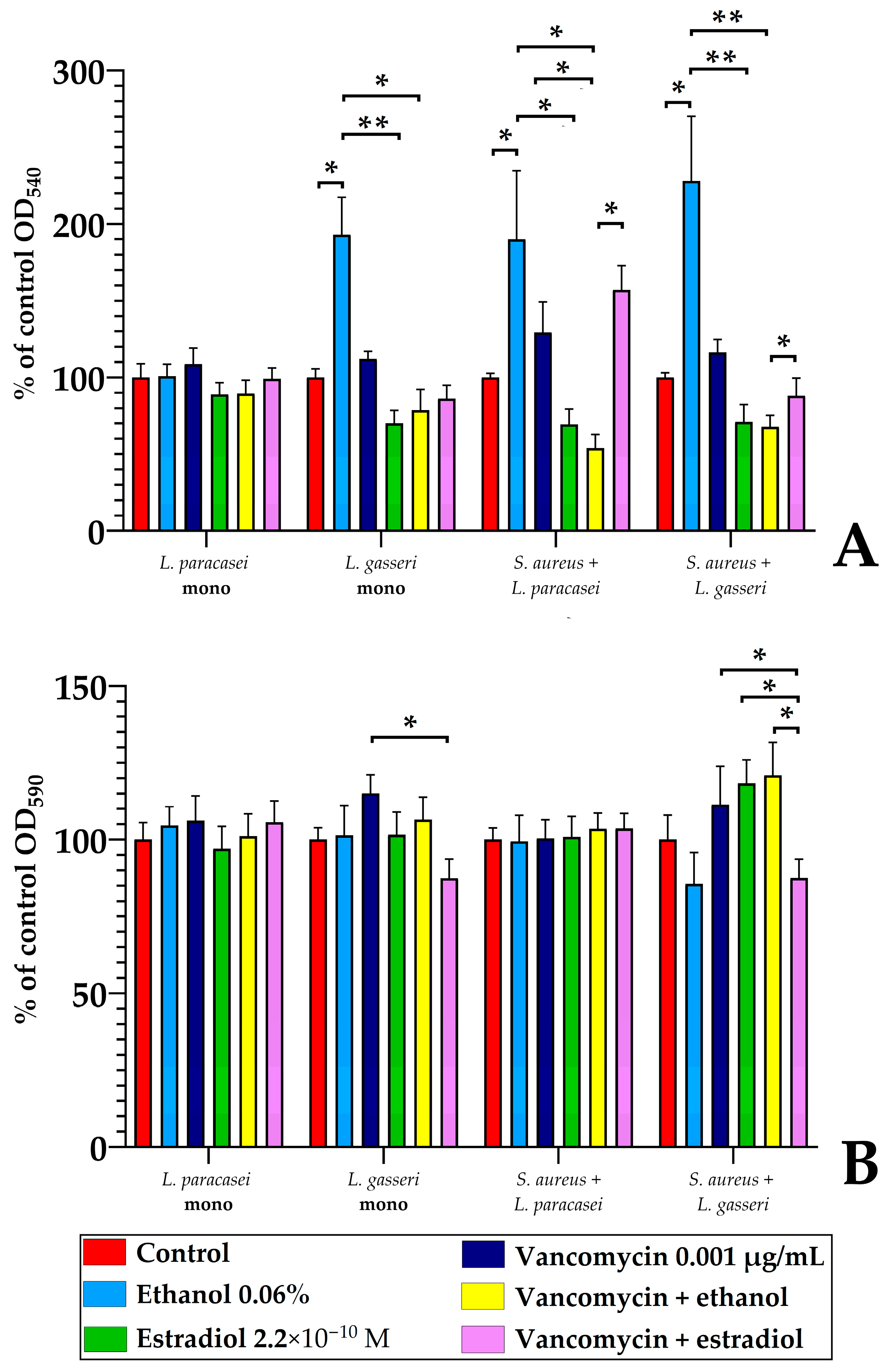

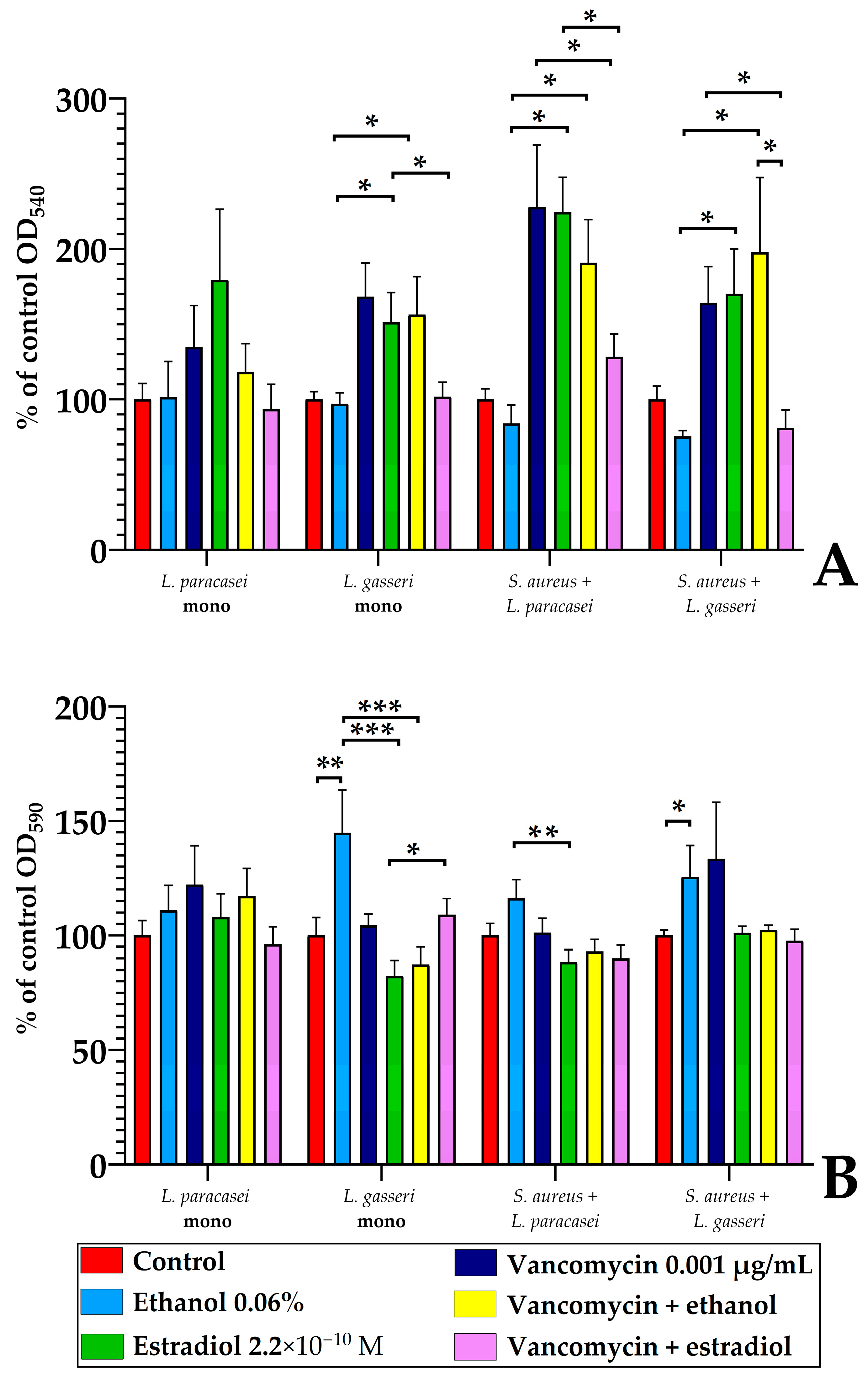

3.5.3. The Comparison of L. paracasei and L. gasseri Susceptibility to Estradiol and Vancomycin

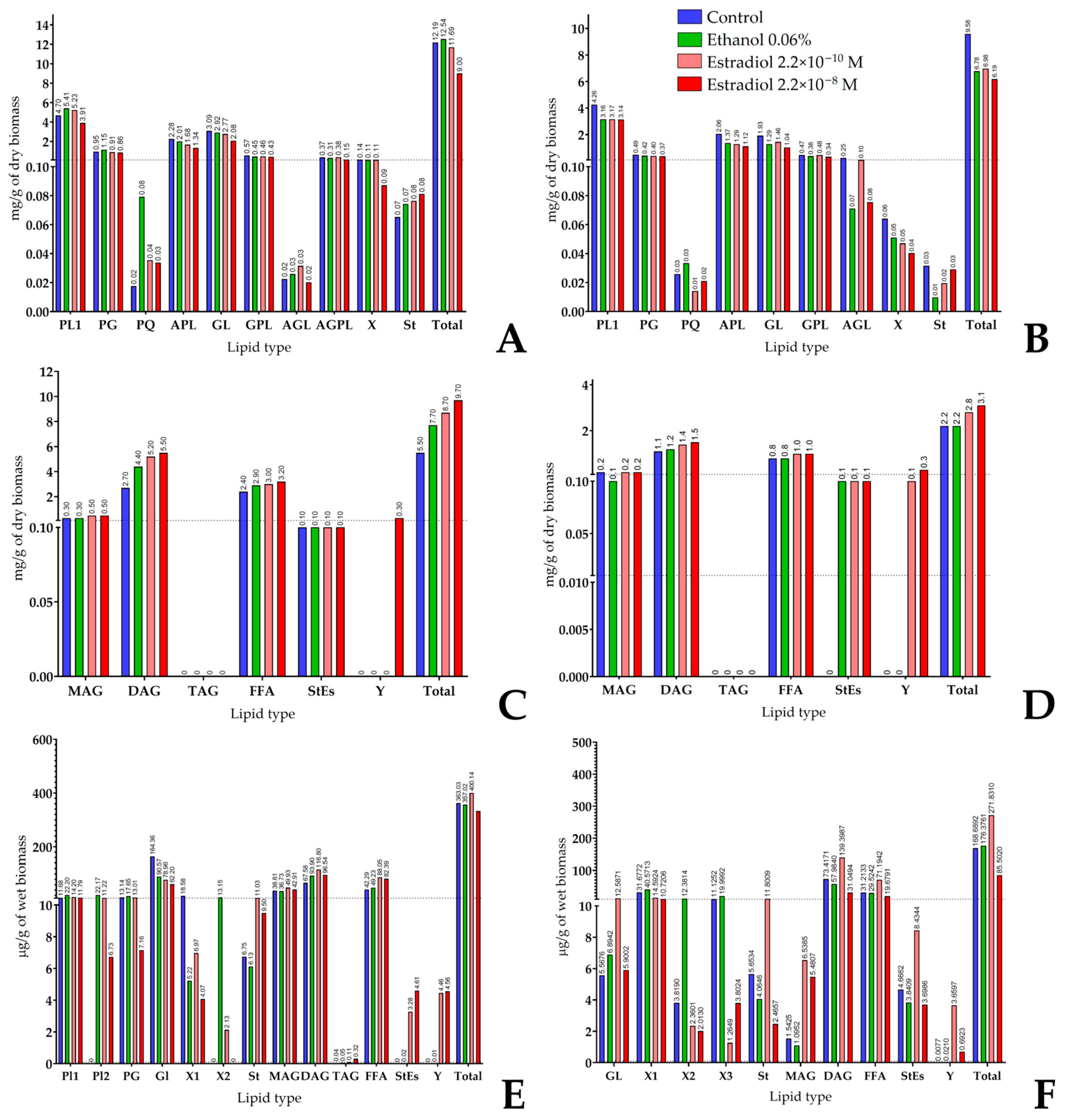

3.6. Lipid Composition of Cells and Biofilm Matrix in Lactobacilli and Its Modulation by Estradiol

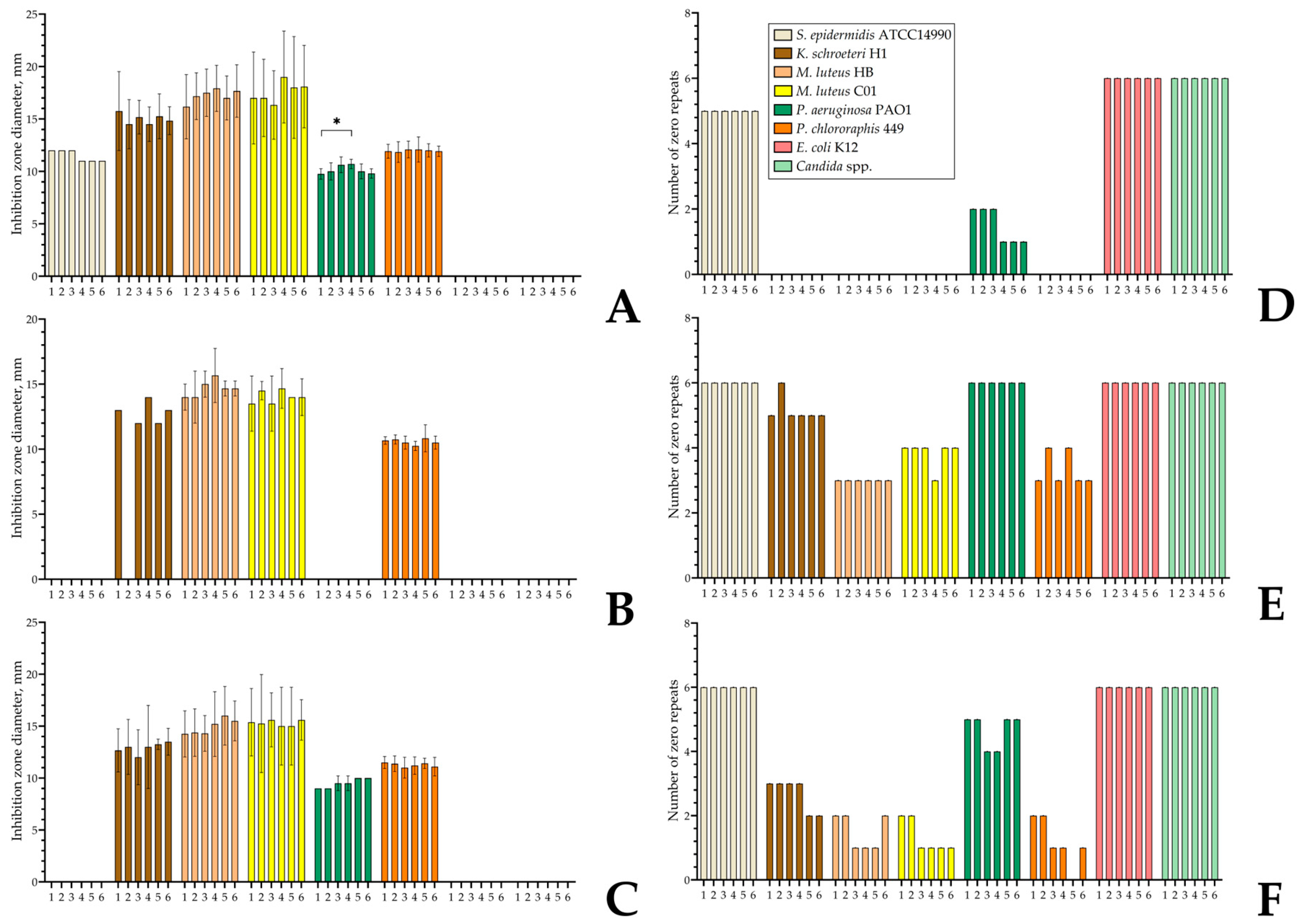

3.7. Antibacterial Activity of Monospecies and Dual-Species Biofilms in the Presence of Estradiol, Ethanol, and Vancomycin

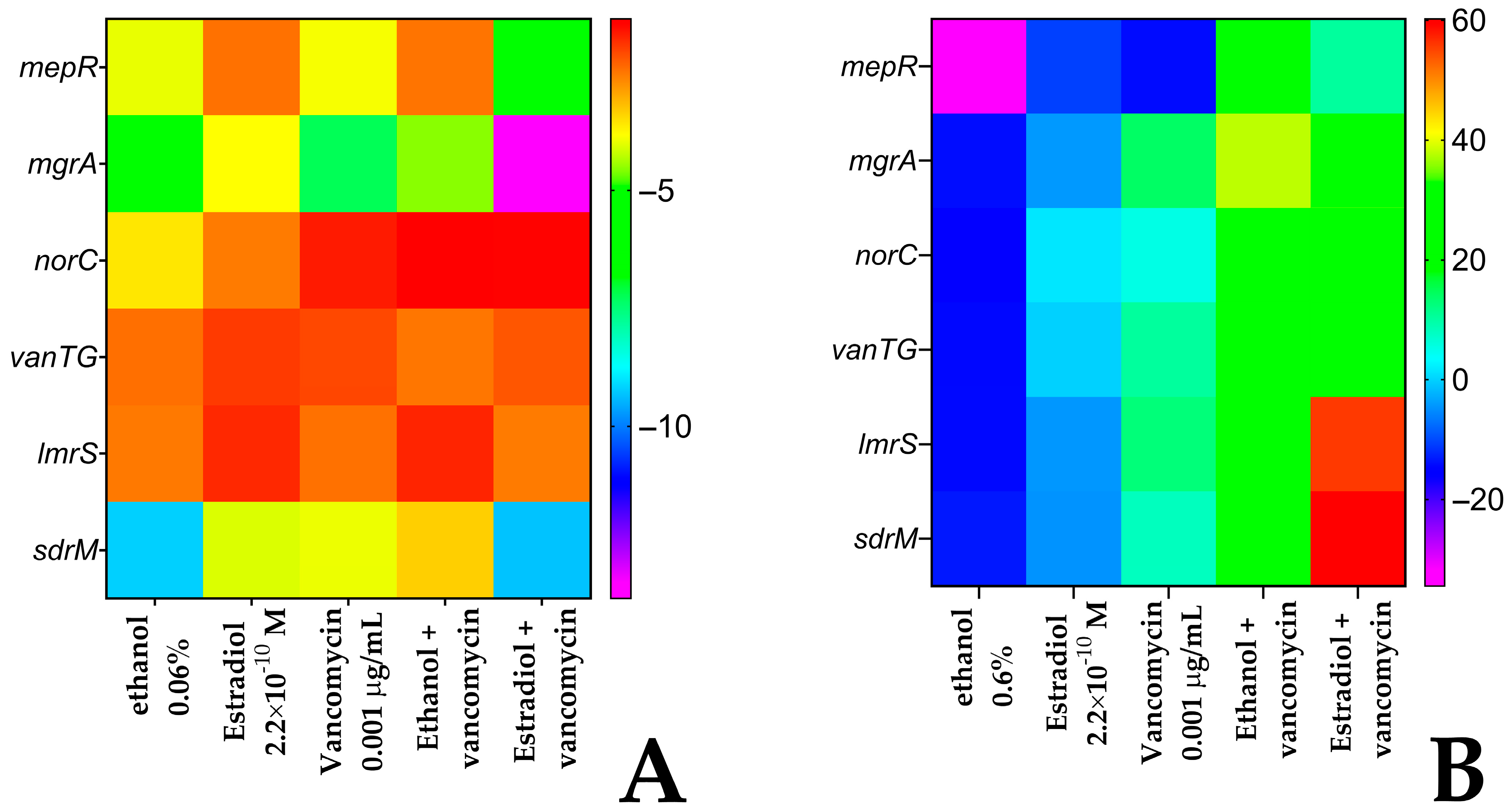

3.8. Differential Gene Expression in S. aureus

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, E.; Zilber-Rosenberg, I. The Hologenome Concept: Human, Animal and Plant Microbiota; Springer Cham: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Lyte, M. Microbial endocrinology and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 817, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasolli, E.; Asnicar, F.; Manara, S.; Zolfo, M.; Karcher, N.; Armanini, F.; Beghini, F.; Manghi, P.; Tett, A.; Ghensi, P.; et al. Extensive unexplored human microbiome diversity revealed by over 150,000 genomes from metagenomes spanning age, geography, and lifestyle. Cell 2019, 176, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, A.; Yao, M.; Fang, J.; Dai, Z.; Li, X.; van der Meer, W.; Medema, G.; Rose, J.B.; Liu, G. Bacterial communities of planktonic bacteria and mature biofilm in service lines and premise plumbing of a Megacity: Composition, Diversity, and influencing factors. Environ. Int. 2024, 185, 108538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyohannes, G.; Nyerere, A.; Bii, C.; Sbhatu, D.B. Challenges of intervention, treatment, and antibiotic resistance of biofilm-forming microorganisms. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Mitterer, F.; Pombo, J.P.; Schild, S. Biofilms by bacterial human pathogens: Clinical relevance—development, composition and regulation—therapeutical strategies. Microb. Cell 2021, 8, 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Boby, S.; Shafeekh Muyyarikkandy, M. Phytochemicals: A promising strategy to combat biofilm-associated antimicrobial resistance. In Exploring Bacterial Biofilms; Dincer, S., Ozdenefe, M.S., Takci, H.A.M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025; pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Belay, T.; Sonnenfeld, G. Differential effects of catecholamines on in vitro growth of pathogenic bacteria. Life Sci. 2002, 71, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, P.P.; Sandrini, S.M.; Haigh, R.D.; Lyte, M. Microbial endocrinology: How stress influences susceptibility to infection. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaycı-Yüksek, F.; Gümüş, D.; Güler, V.; Uyanık-Öcal, A.; Anğ-Küçüker, M. Progesterone and Estradiol alter the growth, virulence and antibiotic susceptibilities of Staphylococcus aureus. New Microbiol. 2023, 46, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diuvenji, E.V.; Nevolina, E.D.; Solovyev, I.D.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Mart’yanov, S.V.; Novikova, A.S.; Zhurina, M.V.; Plakunov, V.K.; Gannesen, A.V. A-Type natriuretic peptide alters the impact of azithromycin on planktonic culture and on (monospecies and binary) biofilms of skin bacteria Kytococcus schroeteri and Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoroge, J.; Sperandio, V. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli virulence regulation by two bacterial adrenergic kinases, QseC and QseE. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannesen, A.V.; Lesouhaitier, O.; Racine, P.J.; Barreau, M.; Netrusov, A.I.; Plakunov, V.K.; Feuilloley, M.G.J. Regulation of monospecies and mixed biofilms formation of skin Staphylococcus aureus and Cutibacterium acnes by human natriuretic peptides. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovcharova, M.A.; Schelkunov, M.I.; Geras’kina, O.V.; Makarova, N.E.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Martyanov, S.V.; Nevolina, E.D.; Zhurina, M.V.; Feofanov, A.V.; Botchkova, E.A.; et al. C-Type natriuretic peptide acts as a microorganism-activated regulator of the skin commensals Staphylococcus epidermidis and Cutibacterium acnes in dual-species biofilms. Biology 2023, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A. The orchestra of human bacteriome by hormones. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 180, 106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabaut, M.; Boukerb, A.M.; Ben Mlouka, A.; Suet, A.; Tahrioui, A.; Verdon, J.; Barreau, M.; Maillot, O.; Le Tirant, A.; Karsybayeva, M.; et al. Variability of the response of human vaginal Lactobacillus crispatus to 17β-estradiol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabaut, M.; Suet, A.; Racine, P.J.; Tahrioui, A.; Verdon, J.; Barreau, M.; Maillot, O.; Le Tirant, A.; Karsybayeva, M.; Kremser, C.; et al. Effect of 17β-estradiol on a human vaginal Lactobacillus crispatus strain. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaillac, C.; Yong, V.F.L.; Aschtgen, M.S.; Qu, J.; Yang, S.; Xu, G.; Seng, Z.J.; Brown, A.C.; Ali, M.K.; Jaggi, T.K.; et al. Sex steroids induce membrane stress responses and virulence properties in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 2020, 11, e01774-20, Erratum in mBio 2020, 11. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02809-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, J.J.; Fultz, L.M.; White, P.; Jeong, C. Application of biochar in estrogen hormone-contaminated and manure-affected soils: Impact on soil respiration, microbial community and enzyme activity. Chemosphere 2021, 270, 128625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beury-Cirou, A.; Tannières, M.; Minard, C.; Soulère, L.; Rasamiravaka, T.; Dodd, R.H.; Queneau, Y.; Dessaux, Y.; Guillou, C.; Vandeputte, O.M.; et al. At a supra-physiological concentration, human sexual hormones act as quorum-sensing inhibitors. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zawity, J.; Afzal, F.; Awan, A.; Nordhoff, D.; Kleimann, A.; Wesner, D.; Montier, T.; Le Gall, T.; Müller, M. Effects of the Sex Steroid Hormone Estradiol on Biofilm Growth of Cystic Fibrosis Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 941014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fteita, D.; Könönen, E.; Gürsoy, M.; Söderling, E.; Gürsoy, U.K. Does estradiol have an impact on the dipeptidyl peptidase IV enzyme activity of the Prevotella intermedia group bacteria? Anaerobe 2015, 36, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelsöy, U.; Svensson, M.A.; Demirel, I. Estradiol alters the virulence traits of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 682626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.D.; Noh, H.L.; Graham, M.E.; Suk, S.; Friedline, R.H.; Gomez, C.C.; Parakoyi, A.E.R.; Chen, J.; Kim, J.K.; Tetel, M.J. Distinct changes in gut microbiota are associated with estradiol-mediated protection from diet-induced obesity in female mice. Metabolites 2021, 11, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Rui, C.; Zhuang, B.; Liu, X.; Luan, T.; Jiang, L.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wu, A.; Li, P.; et al. 17β-Estradiol mediates Staphylococcus aureus adhesion in vaginal epithelial cells via estrogen receptor α-associated signaling pathway. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, J.P.; Hakansson, A.P.; Lee, S.A. Editorial: Microbial biofilms interacting with host mucosal surfaces. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1049347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, W.J.Y.; Chew, S.Y.; Than, L.T.L. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzaretti, S.; Taverniti, V.; Rondini, G.; Marcolegio, G.; Minuzzo, M.; Remagni, M.C.; Fiore, W.; Arioli, S.; Guglielmetti, S. The vaginal isolate Lactobacillus paracasei LPC-S01 (DSM 26760) is suitable for oral administration. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, F.; Giordani, B.; Fedi, S.; Ghezzi, D.; Galletti, P.; Mercolini, L.; Mandrioli, R.; Parolin, C.; Luppi, B.; Vitali, B. Vaginal Lactobacillus gasseri biosurfactant: A novel bio- and eco-compatible anti-Candida agent. Biofilm 2025, 10, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maduta, C.S.; Tuffs, S.W.; McCormick, J.K.; Dufresne, K. Interplay between Staphylococcus aureus and the vaginal microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancomycin Hydrochloride 2% Vaginal Gel. Available online: https://www.bayviewrx.com/formulas/Vancomycin-Hydrochloride-2-Vaginal-Gel-Bacterial-Vaginosis-Vaginal-Infections-Methicillin-Resistant-Staphylococcus-Aureus-MRSA-Colonization-Recurrent-Vaginal-Infections-Vaginal-Microbiota-Imbalance (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Kiseleva, A.A.; Solovyeva, T.V.; Ovcharova, M.A.; Geras’kina, O.V.; Mart’yanov, S.V.; Cherdyntseva, T.A.; Danilova, N.D.; Zhurina, M.V.; Botchkova, E.A.; Feofanov, A.V.; et al. Effect of β-estradiol on mono- and mixed-species biofilms of human commensal bacteria Lactobacillus paracasei AK508 and Micrococcus luteus C01 on different model surfaces. Coatings 2022, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmina, E.; Stanczyk, F.Z.; Lobo, R.A. Evaluation of hormonal status. In Yen and Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology and Clinical Management, 6th ed.; Strauss, J.F., III, Barbieri, R.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Saunders, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 801–823. [Google Scholar]

- Mart’yanov, S.V.; Botchkova, E.A.; Plakunov, V.K.; Gannesen, A.V. The impact of norepinephrine on mono-species and dual-species Staphylococcal Biofilms. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.A. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannesen, A.V.; Ziganshin, R.H.; Zdorovenko, E.L.; Klimko, A.I.; Ianutsevich, E.A.; Danilova, O.A.; Tereshina, V.M.; Gorbachevskii, M.V.; Ovcharova, M.A.; Nevolina, E.D.; et al. Epinephrine extensively changes the biofilm matrix composition in Micrococcus luteus C01 isolated from human skin. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1003942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovcharova, M.A.; Geraskina, O.V.; Danilova, N.D.; Botchkova, E.A.; Martyanov, S.V.; Feofanov, A.V.; Plakunov, V.K.; Gannesen, A.V. Atrial natriuretic peptide affects skin commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis and Cutibacterium acnes dual-species biofilms. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elleuch, L.; Shaaban, M.; Smaoui, S.; Mellouli, L.; Karray-Rebai, I.; Fourati-Ben Fguira, L.; Shaaban, K.A.; Laatsch, H. Bioactive secondary metabolites from a new terrestrial Streptomyces sp. TN262. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 162, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, V.A.; Trebesius, K.; Autenrieth, I.B. Fluorescent In situ hybridization allows rapid identification of microorganisms in blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeer, S.; Verhoeven, T.L.; Claes, I.J.; De Hertogh, G.; Vermeire, S.; Buyse, J.; Van Immerseel, F.; Vanderleyden, J.; De Keersmaecker, S.C. FISH analysis of Lactobacillus biofilms in the gastrointestinal tract of different hosts. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 52, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannesen, A.V.; Zdorovenko, E.L.; Botchkova, E.A.; Hardouin, J.; Massier, S.; Kopitsyn, D.S.; Gorbachevskii, M.V.; Kadykova, A.A.; Shashkov, A.S.; Zhurina, M.V.; et al. Composition of the biofilm matrix of Cutibacterium acnes acneic strain RT5. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, B.W. Separation of the lipids of photosynthetic tissues: Improvements in analysis by thin-layer chromatography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1963, 70, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benning, C.; Huang, Z.H.; Gage, D.A. Accumulation of a novel glycolipid and a betaine lipid in cells of Rhodobacter sphaeroides grown under phosphate limitation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995, 317, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kates, M. Techniques of Lipidology: Isolation, Analysis and Identification of Lipids; Laboratory Techniques in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1972; Volume 3, p. 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaskovsky, V.E.; Kostetsky, E.Y.; Vasendin, I.M. A universal reagent for phospholipid analysis. J. Chromatogr. 1975, 114, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diuvenji, E.V.; Soloviev, I.D.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Nevolina, E.D.; Ovcharova, M.A.; Loginova, N.A.; Mosolova, A.M.; Mart’yanov, S.V.; Plakunov, V.K.; Gannesen, A.V. Modulation of azithromycin activity against single-species and binary biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus and Kytococcus schroeteri by norepinephrine. Microbiology 2024, 93, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Available online: https://card.mcmaster.ca/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; UGENE Team. Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikandi, J.; San Millán, R.; Rementeria, A.; Garaizar, J. In silico analysis of complete bacterial genomes: PCR, AFLP-PCR and endonuclease restriction. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 798–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullar, R.; Leonard, S.N.; Davis, S.L.; Delgado, G., Jr.; Pogue, J.M.; Wahby, K.A.; Falcione, B.; Rybak, M.J. Validation of the effectiveness of a vancomycin nomogram in achieving target trough concentrations of 15–20 mg/L suggested by the vancomycin consensus guidelines. Pharmacotherapy 2011, 31, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Child, S.A.; Ghith, A.; Bruning, J.B.; Bell, S.G. A comparison of steroid and lipid binding cytochrome P450s from Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 209, 111116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griekspoor, A.; Zwart, W.; Neefjes, J.; Michalides, R. Visualizing the action of steroid hormone receptors in living cells. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2007, 5, nrs-05003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos da Silva, D.; Patel, H.K.; González, J.F.; Devescovi, G.; Meng, X.; Covaceuszach, S.; Lamba, D.; Subramoni, S.; Venturi, V. Studies on synthetic LuxR solo hybrids. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diuvenji, E.V.; Nevolina, E.D.; Mart’Yanov, S.V.; Zhurina, M.A.; Kalmantaeva, O.V.; Makarova, M.A.; Botchkova, E.A.; Firstova, B.B.; Plakunov, V.K.; Gannesen, A.V. Binary biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus 209P and Kytococcus schroeteri H01: Dualistic role of kytococci and cell adhesion alterations in the presence of the A-type natriuretic peptide. Microbiology 2022, 91, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.R.; Lazarenko, O.P.; Haley, R.L.; Blackburn, M.L.; Badger, T.M.; Ronis, M.J. Ethanol impairs estrogen receptor signaling resulting in accelerated activation of senescence pathways, whereas estradiol attenuates the effects of ethanol in osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2009, 24, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, I.; Somerville, G.A.; Heilmann, C.; Sahl, H.G.; Maurer, H.H.; Herrmann, M. Very low ethanol concentrations affect the viability and growth recovery in post-stationary-phase Staphylococcus aureus populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancomycin. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/vancomycin.html (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Wei, Y.; Yang, J.W.; Boddu, S.H.; Jung, R.; Churchwell, M.D. Compatibility, stability, and efficacy of vancomycin combined with gentamicin or ethanol in sodium citrate as a catheter lock solution. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 52, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.C.; Quindlen, E.A. Accumulation of vancomycin after intraventricular infusions. South. Med. J. 1983, 76, 1554–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.; Mabasa, V.H.; Chow, I.; Ensom, M.H. Systematic review of efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and administration of intraventricular vancomycin in adults. Neurocritical Care 2014, 20, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolin, C.; Croatti, V.; Laghi, L.; Giordani, B.; Tondi, M.R.; De Gregorio, P.R.; Foschi, C.; Vitali, B. Lactobacillus biofilms influence anti-Candida activity. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 750368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Microorganism | Sequence 5′-3′ | Fluorophore | Wavelength, nm | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus 209P | GCCCCAAGATTACACTTCCG | FAM | 488 | [39] |

| L. paracasei AK508 | GTATTAGCAYCTGTTTCCA | R6G | 561 | [40] |

| OD540 of an Inoculum | Analysis | Ethanol | Estradiol | Vancomycin 0.001 µg/mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | +Ethanol | +Estradiol | |||||

| S. aureus in monospecies biofilms | 0.5 | CFU | N/E | N/E | N/E | N/E | N/E |

| MTT | N/E | N/E | N/E | N/E | N/E | ||

| CV on PTFE | N/E | N/E | In | N/E | St | ||

| 2 | CFU | N/E | TSt | TSt | TIn | TIn | |

| MTT | N/E | N/E | N/E | N/E | N/E | ||

| S. aureus in dual-species biofilms | 0.5 | CFU | TSt | TIn | TIn | TIn | TSt |

| MTT | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| 2 | CFU | N/E | TI | TI | In | St | |

| MTT | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| L. paracasei in monospecies biofilms | 0.5 (S. aureus 0.5) | CFU | TIn | TSt | N/E | N/E | N/E |

| MTT | N/E | N/E | N/E | TIn | TSt | ||

| CV on PTFE | TSt | N/E | TSt | TSt | In | ||

| 0.5 (S. aureus 2) | CFU | TIn | TIn | TIn | N/E | TSt | |

| MTT | TIn | N/E | TIn | TSt | TIn | ||

| L. paracasei in dual-species biofilms | 0.5 (S. aureus 0.5) 0.5 (S. aureus 2) | CFU | TSt | TIn | N/E | TSt | TSt |

| MTT | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| CFU | TIn | TIn | TIn | In | St | ||

| MTT | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mosolova, A.M.; Loginova, N.A.; Diuvenji, E.V.; Chebotarevskii, A.G.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Tsibulnikov, S.V.; Bikmulina, P.Y.; Tereshina, V.M.; Ianutsevich, E.A.; Danilova, O.A.; et al. Estradiol Modulates the Sensitivity to Vancomycin of Lactobacillus paracasei and Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms—Constituents of Human Skin and Vaginal Microbiota. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122777

Mosolova AM, Loginova NA, Diuvenji EV, Chebotarevskii AG, Sukhacheva MV, Tsibulnikov SV, Bikmulina PY, Tereshina VM, Ianutsevich EA, Danilova OA, et al. Estradiol Modulates the Sensitivity to Vancomycin of Lactobacillus paracasei and Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms—Constituents of Human Skin and Vaginal Microbiota. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122777

Chicago/Turabian StyleMosolova, Anna M., Nadezhda A. Loginova, Ecaterina V. Diuvenji, Artem G. Chebotarevskii, Marina V. Sukhacheva, Sergey V. Tsibulnikov, Polina Y. Bikmulina, Vera M. Tereshina, Elena A. Ianutsevich, Olga A. Danilova, and et al. 2025. "Estradiol Modulates the Sensitivity to Vancomycin of Lactobacillus paracasei and Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms—Constituents of Human Skin and Vaginal Microbiota" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122777

APA StyleMosolova, A. M., Loginova, N. A., Diuvenji, E. V., Chebotarevskii, A. G., Sukhacheva, M. V., Tsibulnikov, S. V., Bikmulina, P. Y., Tereshina, V. M., Ianutsevich, E. A., Danilova, O. A., Novikova, A. S., Plakunov, V. K., Martyanov, S. V., Netrusov, A. I., & Gannesen, A. V. (2025). Estradiol Modulates the Sensitivity to Vancomycin of Lactobacillus paracasei and Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms—Constituents of Human Skin and Vaginal Microbiota. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122777