Effects of Long-Term Elevated CO2 on Soil Aggregate Structure and Microbial Communities in a Deyeuxia angustifolia Wetland of the Sanjiang Plain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Setup

2.2. Soil Sample Collection

2.3. Soil Aggregate Fractionation and Stability Indices

2.4. Soil Sample Analyses

2.5. Phospholipid Fatty Acid Analysis (PLFA Analysis)

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

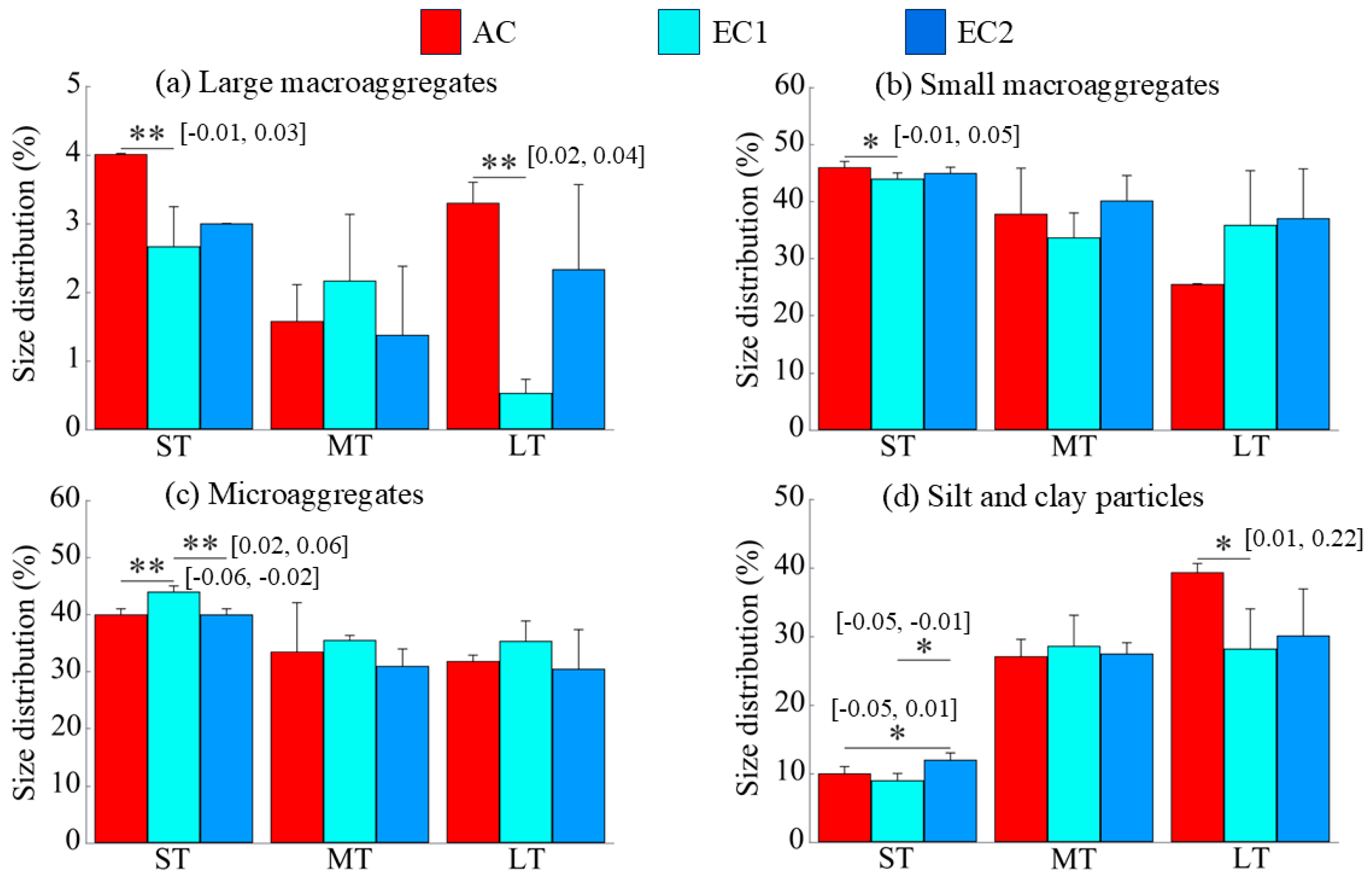

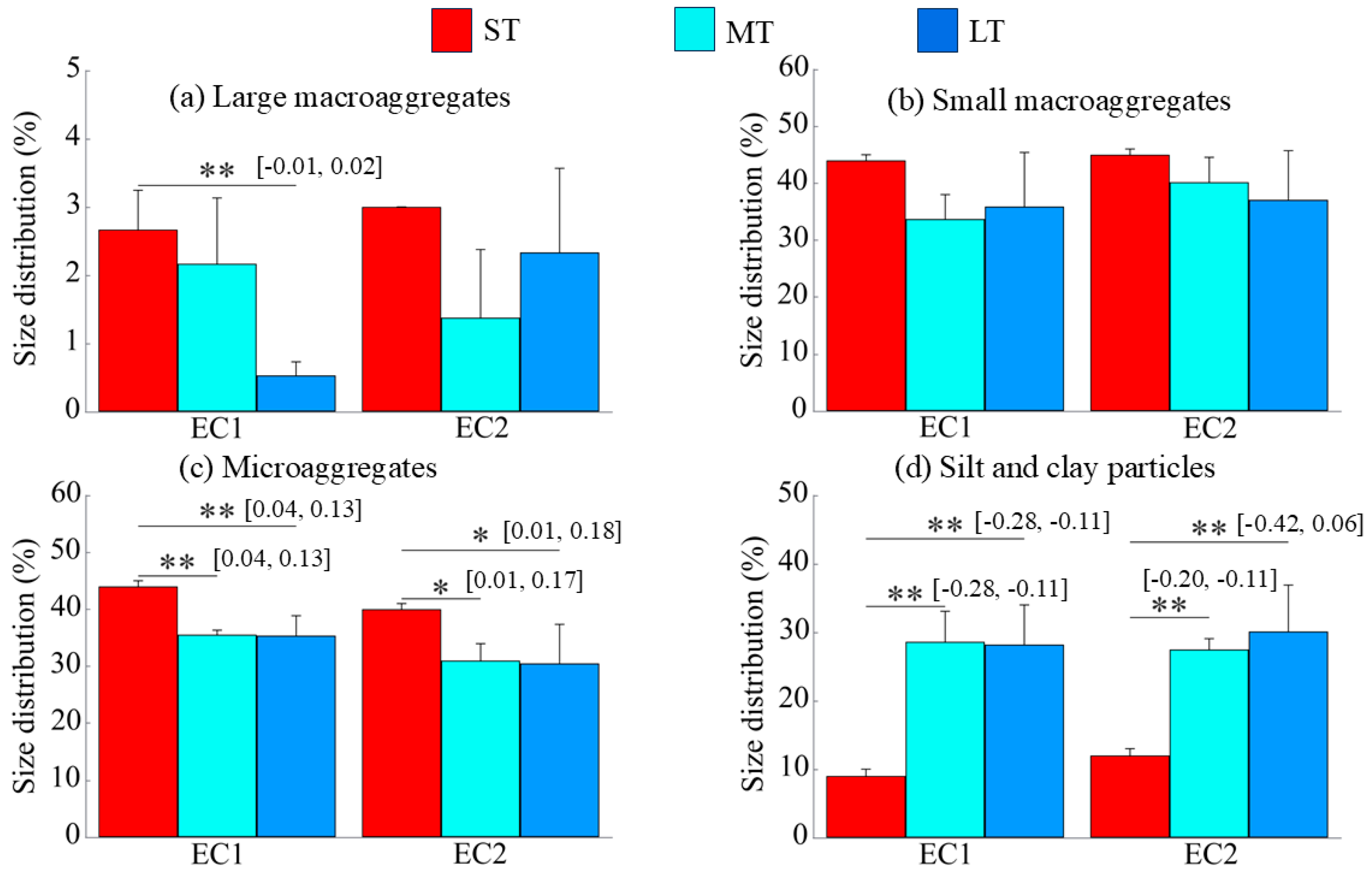

3.1. Particle Size Distribution of Soil Aggregates

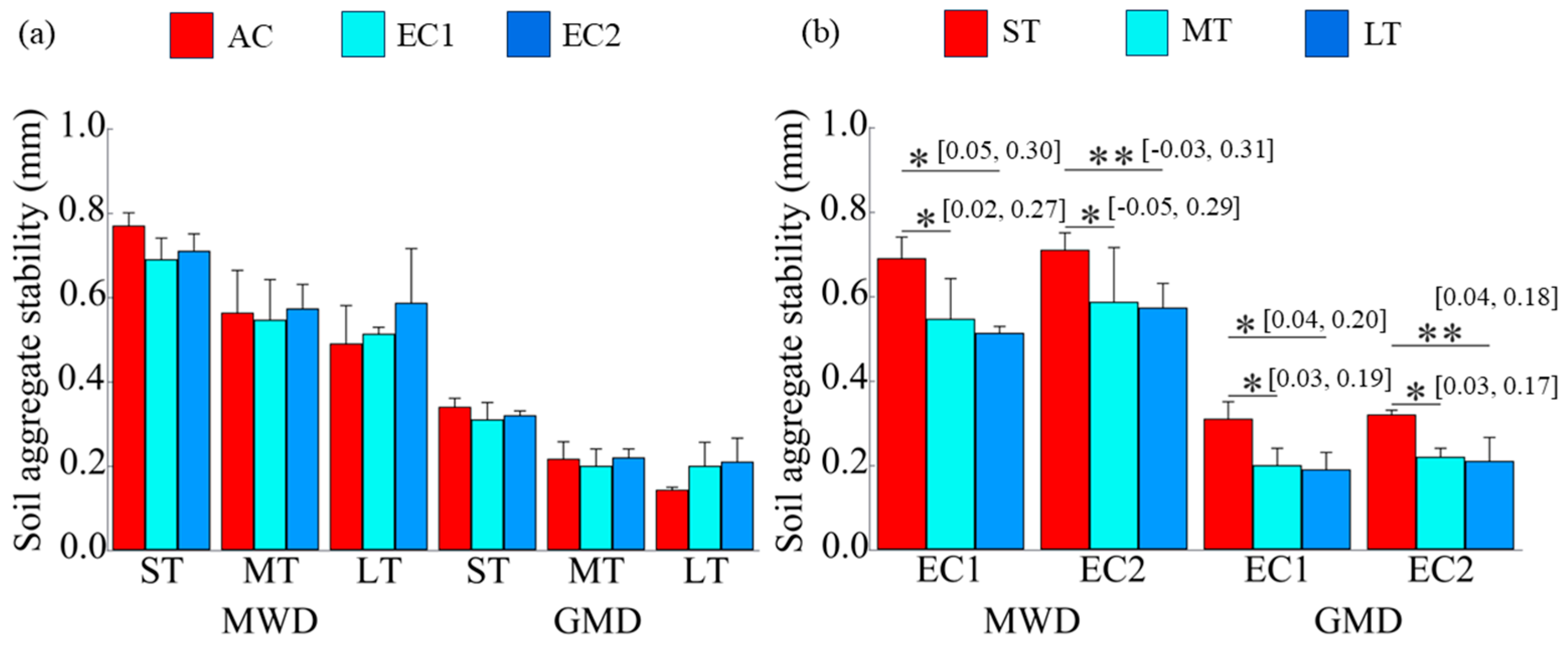

3.2. Soil Aggregate Stability

3.3. Soil Microbial PLFAs, Composition, and Diversity

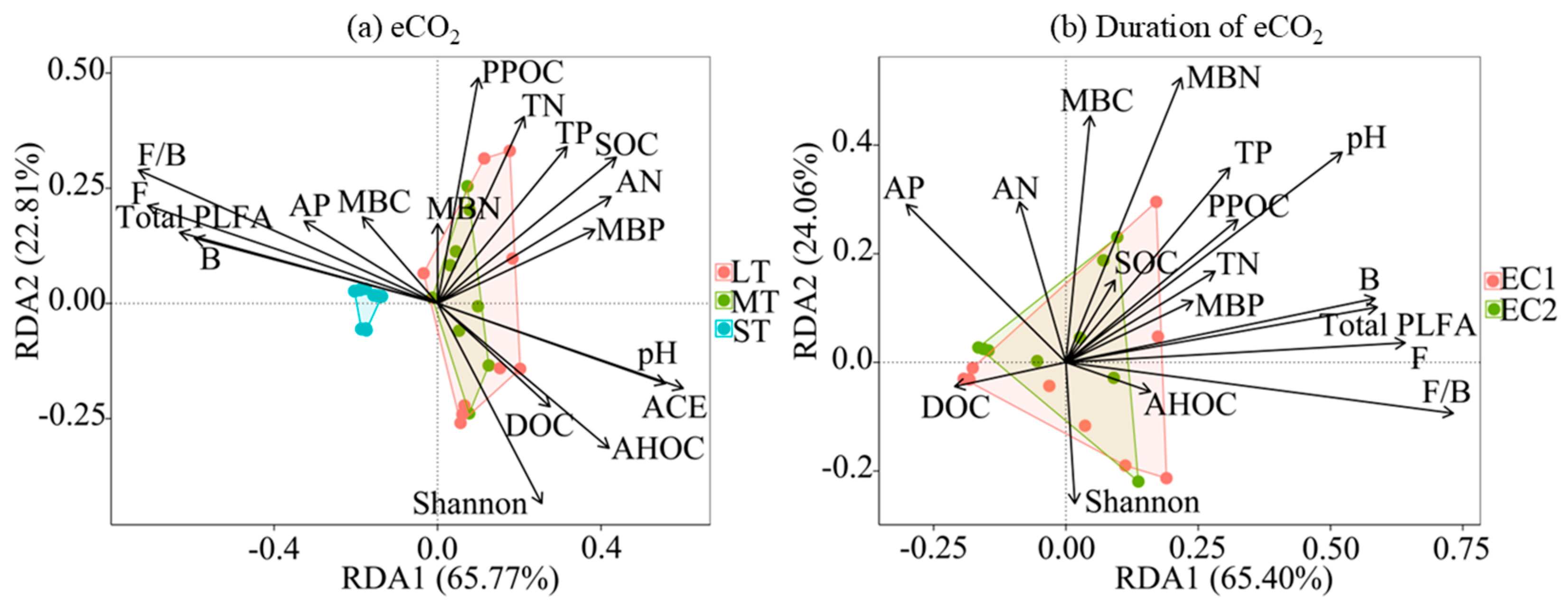

3.4. Influencing Factors of Soil Aggregates

3.5. The Relationship Between Aggregate Components and Stability

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Soil Aggregate Distribution

4.2. Changes in Soil Aggregate Stability

4.3. Changes in Soil Microbial Community Structure

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindsey, R. Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide, 2022. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-atmospheric-carbon-dioxide (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Adak, S.; Mandal, N.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Maity, P.P.; Sen, S. Current State and Prediction of Future Global Climate Change and Variability in Terms of CO2 Levels and Temperature. In Enhancing Resilience of Dryland Agriculture Under Changing Climate: Interdisciplinary and Convergence Approaches; Naorem, A., Machiwal, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Y. Soil aggregates regulate the impact of soil bacterial and fungal communities on soil respiration. Geoderma 2019, 337, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Kang, H.J.J.O.M. Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations on soil microorganisms. J. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, P.; Qiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Gao, C.; Liu, C.; Shao, J.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Z.; et al. The potential for soil C sequestration and N fixation under different planting patterns depends on the carbon and nitrogen content and stability of soil aggregates. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 897, 165430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Becker, E.; Liang, G.; Houssou, A.A.; Wu, H.; Wu, X.; Cai, D.; Degré, A. Effect of different tillage systems on aggregate structure and inner distribution of organic carbon. Geoderma 2017, 288, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verchot, L.V.; Dutaur, L.; Shepherd, K.D.; Albrecht, A. Organic matter stabilization in soil aggregates: Understanding the biogeochemical mechanisms that determine the fate of carbon inputs in soils. Geoderma 2011, 161, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Meng, J.; Lan, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, T.; Yuan, J.; Liu, S.; Han, J. Effects of maize stover and its biochar on soil CO2 emissions and labile organic carbon fractions in Northeast China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 240, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, X.; Mclaughlin, N.B.; Liang, A.; Jia, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, X. Effect of soil temperature and soil moisture on CO2 flux from eroded landscape positions on black soil in Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2014, 144, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, O.Y.A.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Kuramae, E.E. Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances: Ecological Function and Impact on Soil Aggregation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.V.S.R.; Germida, J.J. Soil aggregation: Influence on microbial biomass and implications for biological processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 80, A3–A9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, D.R.; Pregitzer, K.S.; King, J.S.; Holmes, W.E. Elevated atmospheric CO2, fine roots and the response of soil microorganisms: A review and hypothesis. New Phytol. 2000, 147, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Long, S.P. What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol. 2005, 165, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leakey, A.D.B.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Rogers, A.; Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. Elevated CO2 effects on plant carbon, nitrogen, and water relations: Six important lessons from FACE. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 2859–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.Y.; Wang, A.X.; Ni, H.W. Effect of elevated CO2 concentration on leaf photosynthesis in Sanjiang-Deyeuxia angustifolia. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 726, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drigo, B.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Van Veen, J.A. Climate change goes underground: Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 on microbial community structure and activities in the rhizosphere. Biol Fertil Soils 2008, 44, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Goede, S.P.C.; Hannula, S.E.; Jansen, B.; Morriën, E. Fungal-mediated soil aggregation as a mechanism for carbon stabilization. ISME J. 2025, 19, wraf074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoosbeek, M.R.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.E. Increased litter build up and soil organic matter stabilization in a poplar plantation after 6 years of atmospheric CO2 enrichment (FACE): Final results of POP-EuroFACE compared to other forest FACE experiments. Ecosystems 2009, 12, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.K.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Samal, S.K.; Singh, N.R.; Mishra, J.S.; Prakash, V.; Choubey, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Bhatt, B.P. Impact of simultaneous increase in CO2 and temperature on soil aggregates, associated organic carbon, and nutritional quality of rice–wheat grains. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2024, 187, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Liu, X.; Vinci, G.; Sun, B.; Drosos, M.; Li, L.; Piccolo, A.; Pan, G. Aggregate fractions shaped molecular composition change of soil organic matter in a rice paddy under elevated CO2 and air warming. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 159, 108289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Xiong, J.; Chen, J. Effects of elevated CO2 and nitrogen addition on organic carbon and aggregates in soil planted with different rice cultivars. Plant Soil 2018, 432, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.L.; Zhu, J.G.; Xie, Z.B.; Liu, G.; Zeng, Q. Effects of increased residue biomass under elevated CO2 on carbon and nitrogen in soil aggregate size classes (rice-wheat rotation system, China). Can. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 89, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, N.; Li, J.; Xing, J.; Zou, H. Effects 10 years elevated atmospheric CO2 on soil bacterial community structure in Sanjiang Plain, Northeastern China. Plant Soil 2022, 471, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, H.; Van Echteld, C.J.A.; Dekkers, E.M.J. Ammonia determination based on indophenol formation with sodium salicylate. Water Res. 1978, 12, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doane, T.A.; Horwáth, W.R. Spectrophotometric Determination of Nitrate with a Single Reagent. Anal. Lett. 2003, 36, 2713–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. In Miscellaneous Paper Institute for Agricultural Research Samaru; US Dept. of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Logninow, W.; Wisniewski, W.; Strony, W.M. Fractionation of organic carbon based on susceptibility to oxidation. Pol. J. Soil Sci. 1987, 20, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira, P.; Vallejo, V.R. Labile and recalcitrant pools of carbon and nitrogen in organic matter decomposing at different depths in soil: An acid hydrolysis approach. Geoderma 2002, 107, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.C.; Landman, A.; Pruden, G.; Jenkinson, D.S. Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: A rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1985, 17, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyer, J.S.; Teasdale, J.R.; Roberts, D.P.; Zasada, I.A.; Maul, J.E. Factors affecting soil microbial community structure in tomato cropping systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, S.; Ge, T.; Jing, H.; Li, B.; Liu, Q.; Lynn, T.M.; Wu, J.; Kuzyakov, Y. Microbial utilization of rice root exudates: 13C labeling and PLFA composition. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2016, 52, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Bell, C.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Pendall, E. Increased plant productivity and decreased microbial respiratory C loss by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria under elevated CO2. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Pan, H.; Ping, Y.; Jin, G.; Song, F. The Underlying Mechanism of Soil Aggregate Stability by Fungi and Related Multiple Factor: A Review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drigo, B.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Knapp, B.A.; Pijl, A.S.; Boschker, H.T.S.; van Veen, J.A. Impacts of 3 years of elevated atmospheric CO2 on rhizosphere carbon flow and microbial community dynamics. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemaninejad, A.; Thorn, R.G.; Branfireun, B.A.; Lindo, Z. Climate change favours specific fungal communities in boreal peatlands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.Q.; Ge, T.D.; Wu, X.H.; Peacock, C.L.; Zhu, Z.K.; Peng, J.; Bao, P.; Wu, J.S.; Zhu, Y.G. Metagenomic and 14C tracing evidence for autotrophic microbial CO2 fixation in paddy soils. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Long, Q.; Huang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, N. Afforestation-induced large macroaggregate formation promotes soil organic carbon accumulation in degraded karst area. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, H.; Liang, C.; Wei, X.; Yao, Y. Soil erosion significantly decreases aggregate-associated OC and N in agricultural soils of Northeast China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 323, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.K.; Morris, D.J.P.; Vogt, S.; Gleber, S.C.; Bigalke, M.; Wilcke, W.; Rillig, M.C. Visualizing the dynamics of soil aggregation as affected by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Zhao, J.S.; Shi, Z.H.; Wang, L. Soil aggregates are key factors that regulate erosion-related carbon loss in citrus orchards of southern China: Bare land vs. grass-covered land. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 309, 107254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Liu, K.; Dou, P.; Shao, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, K.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, K. Soil Nutrients Drive Microbial Changes to Alter Surface Soil Aggregate Stability in Typical Grasslands. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 4943–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhong, Z.; Di, G. Effects of Poplar Shelterbelt Plantations on Soil Aggregate Distribution and Organic Carbon in Northeastern China. Forests 2022, 13, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Liu, Y.; Rizwan, A.; Shoukat, C.A.; Aftab, Q.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y. Impact of elevated CO2 on soil microbiota: A meta-analytical review of carbon and nitrogen metabolism. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, B.; Huang, L.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Gao, R.; Kamran, M.; Fahad, S. Effect of clay mineralogy and soil organic carbon in aggregates under straw incorporation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Wen, H.; Wilson, G.V.; Cai, C.; Wang, J. A simulated study of surface morphological evolution on coarse-textured soils under intermittent rainfall events. Catena 2022, 208, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ma, Z.; Qin, W.; Li, X.; Shi, H.; Hasi, B.; Liu, X. Soil nutrients and pH modulate carbon dynamics in particulate and mineral-associated organic matter during restoration of a Tibetan alpine grassland. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 212, 107522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ao, G.; Feng, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, B. The patterns of forest soil particulate and mineral associated organic carbon characteristics with latitude and soil depth across eastern China. For. Ecosyst. 2025, 12, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Fenner, N.; Freeman, C. Shifts of soil enzyme activities in wetlands exposed to elevated CO2. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 337, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tang, C. The effects of elevated CO2 and nitrogen availability on rhizosphere priming of soil organic matter under wheat and white lupin. Plant Soil 2018, 425, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Krohn, C.; Franks, A.E.; Wang, X.; Wood, J.L.; Petrovski, S.; McCaskill, M.; Batinovic, S.; Xie, Z.; Tang, C. Elevated atmospheric CO2 alters the microbial community composition and metabolic potential to mineralize organic phosphorus in the rhizosphere of wheat. Microbiome 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E.; Brookes, P.C.; Lauber, C.L.; Lozupone, C.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 2010, 4, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, D.R.; Holmes, W.E.; Finzi, A.C.; Norby, R.J.; Schlesinger, W.H. Soil nitrogen cycling under elevated CO2: A synthesis of forest FACE experiments. Ecol. Appl. 2003, 13, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yan, W.; Canisares, L.P.; Wang, S.; Brodie, E.L. Alterations in soil pH emerge as a key driver of the impact of global change on soil microbial nitrogen cycling: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2023, 32, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Chang, S.X.; Liang, C.; An, S. Negative effects of multiple global change factors on soil microbial diversity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 156, 108229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.F.; Liu, Y.; Luo, C.T.; Liu, W.F.; Duan, H.; Liao, Y.; Wu, C.; Fan, H. Research progress on response and adaptation of plant and soil microbial community diversity to global change in terrestrial ecosystem. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2019, 28, 2129–2140. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Krohn, C.; Davis, R.; Franks, A.E.; Wang, X.; Wood, J.L.; Tang, C. Clarifying the role of microbial communities in carbon loss from rhizosphere priming of contrasting crop species under elevated atmospheric CO2. Plant Soil 2025, 515, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.X.; Xiang, X.J.; Zhang, F. Effects of elevated CO2 concentration on soil carbon degrading enzyme activity and soil organic carbon. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 3192–3203. [Google Scholar]

- Frostegård, Å.; Tunlid, A.; Bååth, E. Use and misuse of PLFA measurements in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Treatment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST-AC- | ST-EC1 | ST-EC2 | MT-AC | MT-EC1 | MT-EC2 | LT-AC | LT-EC1 | LT-EC2 | |

| Total PLFAs | 83.16 ± 8.84 a | 78.26 ± 4.58 a | 89.27 ± 4.54 a | 115.34 ± 9.19 a | 136.06 ± 8.51 a | 121.18 ± 10.92 a | 125.16 ± 6.99 a | 131.52 ± 4.26 a | 149.88 ± 23.85 a |

| Bacterial PLFAs | 33.42 ± 3.67 a | 31.16 ± 1.73 a | 35.27 ± 1.60 a | 44.89 ± 3.31 a | 52.86 ± 3.12 a | 47.11 ± 4.23 a | 47.28 ± 2.32 a | 50.00 ± 1.02 a | 56.73 ± 8.72 a |

| Fungal PLFAs | 4.66 ± 0.46 a | 5.04 ± 0.46 a | 6.05 ± 0.51 a | 9.90 ± 1.16 a | 12.04 ± 1.25 a | 10.87 ± 1.12 a | 12.78 ± 1.29 a | 12.53 ± 1.32 a | 14.35 ± 2.65 a |

| F/B | 0.14 ± 0.02 a | 0.16 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.01 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 0.23 ± 0.02 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 a | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.25 ± 0.02 a | 0.25 ± 0.01 a |

| Alpha diversity | |||||||||

| Shannon | 1.71 ± 0.02 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.71 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.73 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a |

| ACE | 10.34 ± 0.20 bc | 10.26 ± 0.11 bc | 10.38 ± 0.08 bc | 10.92 ± 0.56 ab | 11.27 ± 0.51 a | 11.19 ± 0.86 a | 11.40 ± 0.17 a | 11.46 ± 0.10 a | 10.03 ± 0.58 c |

| Variables | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC1-ST | EC1-MT | EC1-LT | EC2-ST | EC2-MT | EC2-LT | |

| Total PLFAs | 78.26 ± 4.58 a | 136.06 ± 8.51 b | 131.52 ± 4.26 b | 89.27 ± 4.54 a | 121.18 ± 10.92 ab | 149.88 ± 23.85 b |

| Bacterial PLFAs | 31.16 ± 1.73 a | 52.86 ± 3.12 b | 50.00 ± 1.02 b | 35.27 ± 1.60 a | 47.11 ± 4.23 ab | 56.73 ± 8.72 b |

| Fungal PLFAs | 5.04 ± 0.46 a | 12.04 ± 1.25 b | 12.53 ± 1.32 b | 6.05 ± 0.51 a | 10.87 ± 1.12 ab | 14.35 ± 2.65 b |

| F/B | 0.16 ± 0.01 a | 0.23 ± 0.02 b | 0.25 ± 0.02 b | 0.17 ± 0.01 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 b | 0.25 ± 0.01 b |

| Alpha diversity | ||||||

| Shannon | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.71 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 1.72 ± 0.01 a |

| ACE | 10.26 ± 0.11 c | 11.27 ± 0.51 a | 11.46 ± 0.10 a | 10.38 ± 0.08 bc | 11.19 ± 0.86 ab | 10.03 ± 0.58 c |

| Treatments | GMD (mm) | >2 mm | 0.25–2 mm | 0.053–0.25 mm | <0.053 mm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST | MWD | 0.76 * | 0.74 * | 0.97 ** | −0.18 | −0.22 |

| GMD | 0.60 | 0.73 * | −0.13 | −0.12 | ||

| MT | MWD | 0.94 * | 0.76 * | 0.85 ** | −0.74 * | −0.63 |

| GMD | 0.54 | 0.94 ** | −0.72 * | −0.75 * | ||

| LT | MWD | 0.75 * | 0.39 | 0.75 * | −0.86 ** | −0.44 |

| GMD | 0.30 | 0.99 ** | −0.38 | −0.92 ** | ||

| EC1 | MWD | 0.91** | 0.83 ** | 0.72 * | 0.72 * | −0.87 ** |

| GMD | 0.63 | 0.92 ** | 0.60 | −0.92 ** | ||

| EC2 | MWD | 0.85 ** | 0.77 * | 0.86 ** | 0.15 | −0.71 * |

| GMD | 0.53 | 0.86 ** | 0.50 | −0.96 ** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, L.; Cao, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Ni, H. Effects of Long-Term Elevated CO2 on Soil Aggregate Structure and Microbial Communities in a Deyeuxia angustifolia Wetland of the Sanjiang Plain. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122776

Shi L, Cao H, Zhang R, Zhong H, Liu Y, Wang J, Zhang D, Li L, Ni H. Effects of Long-Term Elevated CO2 on Soil Aggregate Structure and Microbial Communities in a Deyeuxia angustifolia Wetland of the Sanjiang Plain. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122776

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Lanying, Hongjie Cao, Rongtao Zhang, Haixiu Zhong, Yingnan Liu, Jifeng Wang, Donglai Zhang, Lin Li, and Hongwei Ni. 2025. "Effects of Long-Term Elevated CO2 on Soil Aggregate Structure and Microbial Communities in a Deyeuxia angustifolia Wetland of the Sanjiang Plain" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122776

APA StyleShi, L., Cao, H., Zhang, R., Zhong, H., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Zhang, D., Li, L., & Ni, H. (2025). Effects of Long-Term Elevated CO2 on Soil Aggregate Structure and Microbial Communities in a Deyeuxia angustifolia Wetland of the Sanjiang Plain. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122776