Torque Ripple Suppression in BLDC Reaction Wheels Using Adaptive Composite Control Strategy Under Non-Ideal Back-EMF

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Modeling the Motor Control System and Disturbance Analysis

2.1. Mathematical Modeling of the BLDC Motor

- (1)

- The rotor currents induced by stator harmonic fields are neglected;

- (2)

- Core and stray losses are ignored;

- (3)

- The effect of armature reaction is neglected;

- (4)

- The stator windings are assumed to be identical and symmetrically distributed with a spatial displacement of 120°. Under these assumptions and the equivalent circuit, the phase voltage model of the BLDC motor can be expressed aswhere , , represent the corresponding phase currents, and , , are the phase terminal voltages. Based on the principle of power conservation, the mechanical output power is equal to the electromagnetic input power . The electromagnetic power is expressed as the summation of the products of the back-EMFs and the corresponding phase currents [14]:Neglecting the mechanical losses of the system, including frictional resistance, the mechanical output power of the BLDC motor can be expressed, based on fundamental mechanics, as the product of the electromagnetic torque and the rotor speed, i.e., [15]where denotes the electromagnetic torque, and represents the mechanical angular velocity.

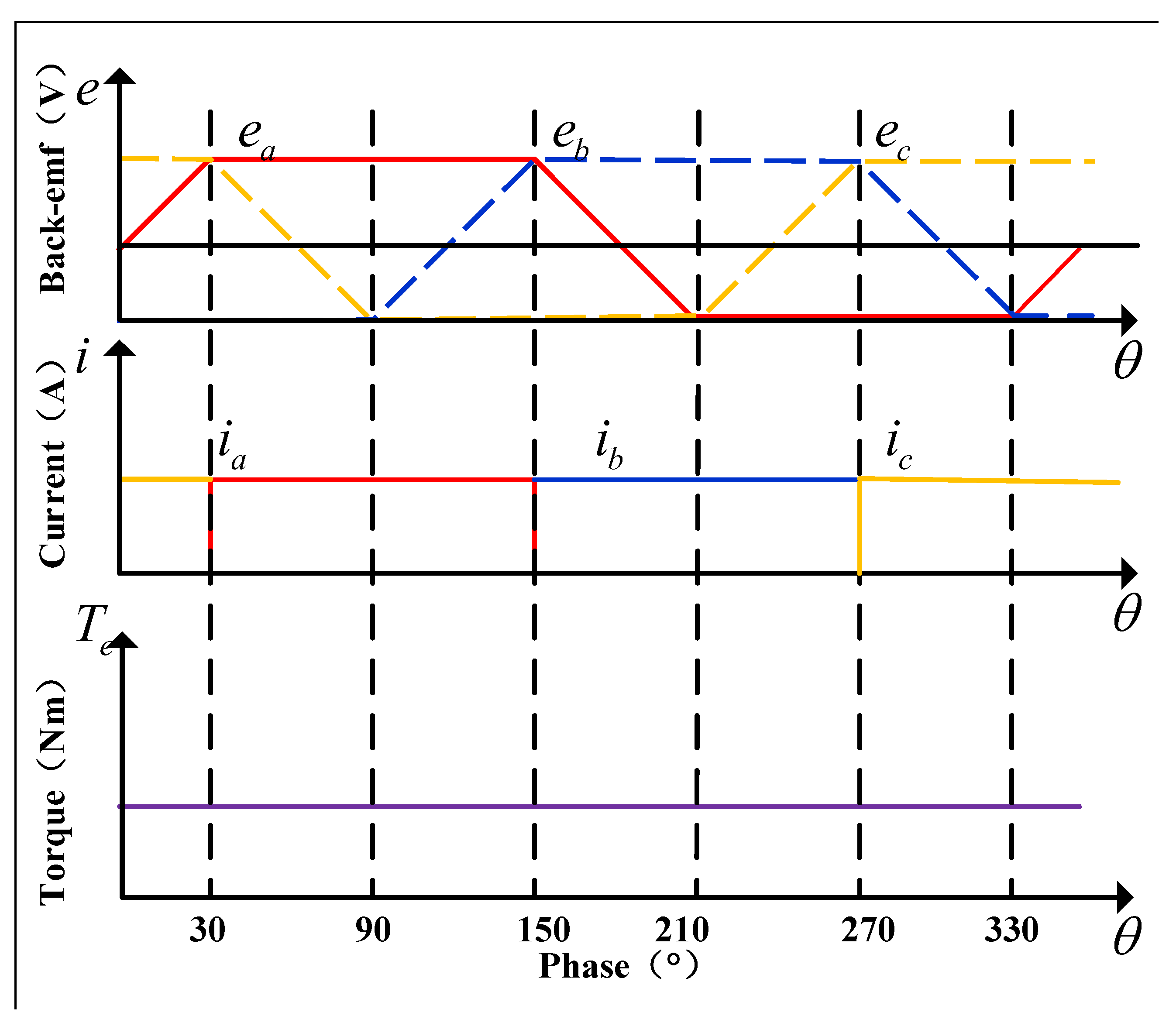

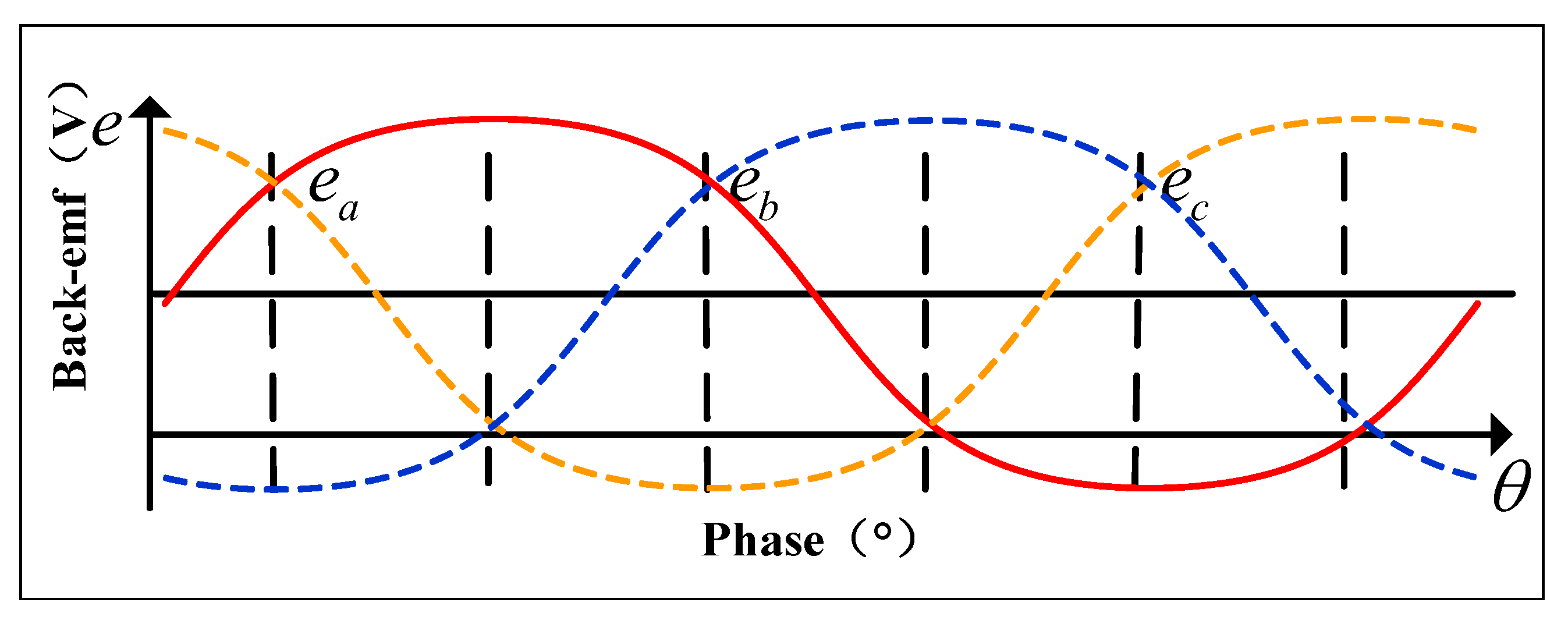

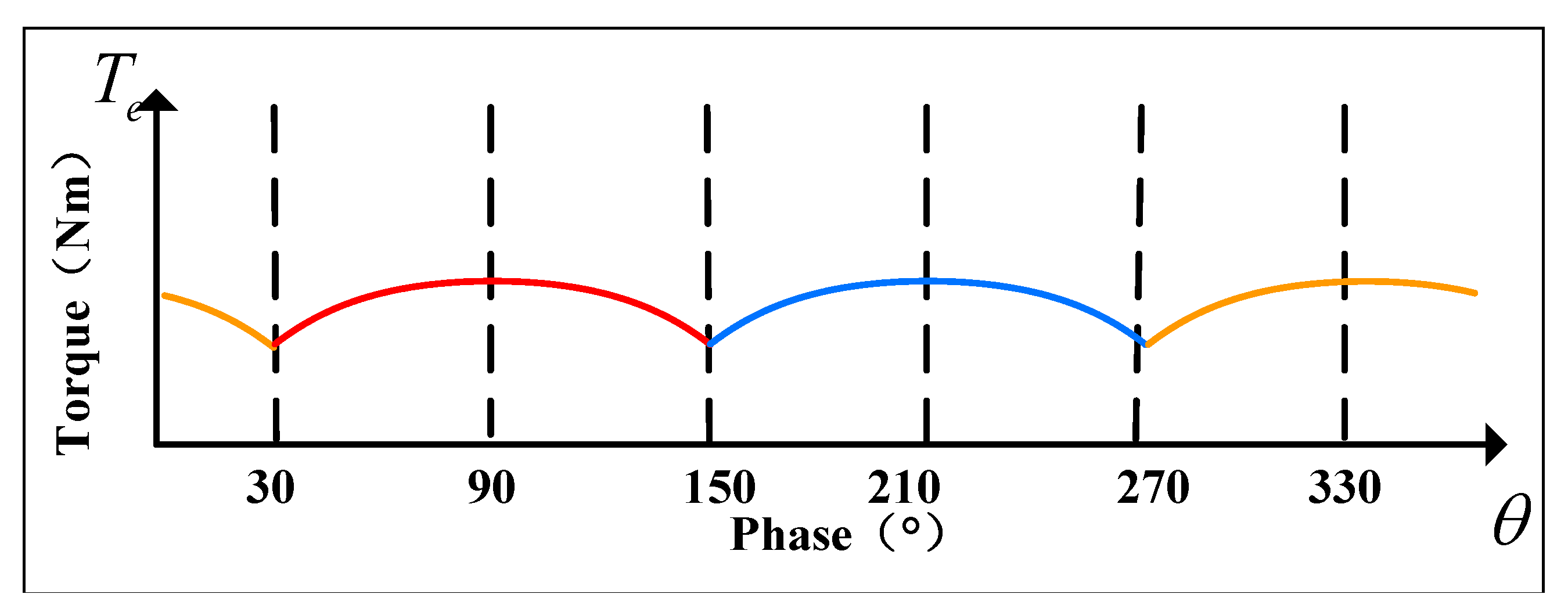

2.2. Torque Ripple Analysis of Reaction Wheel Systems

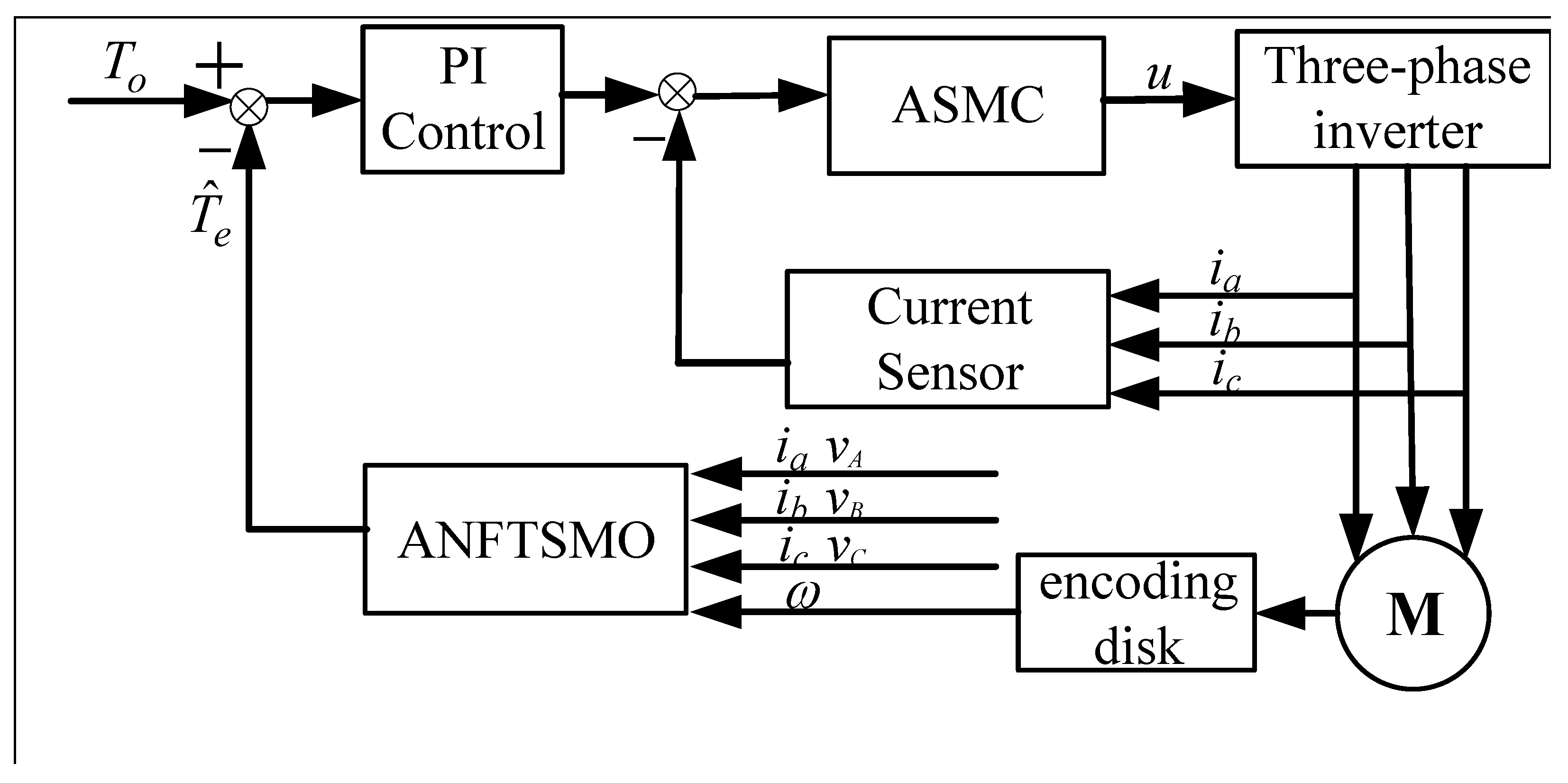

3. Design of the Composite Control Strategy

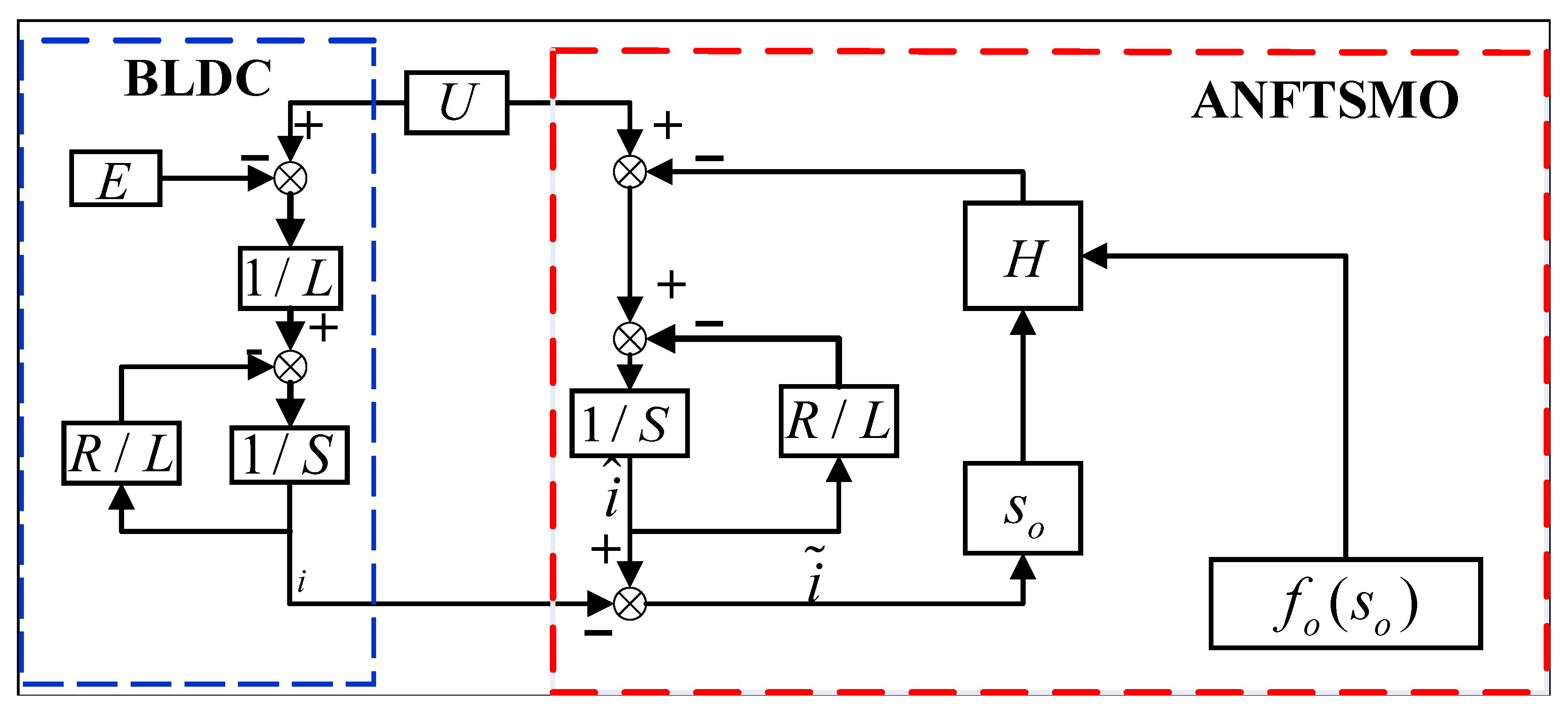

3.1. Adaptive Nonsingular Fast Terminal Sliding-Mode Observer Design

3.2. Adaptive Sliding-Mode Current Control Design

4. Simulation and Experimental Results

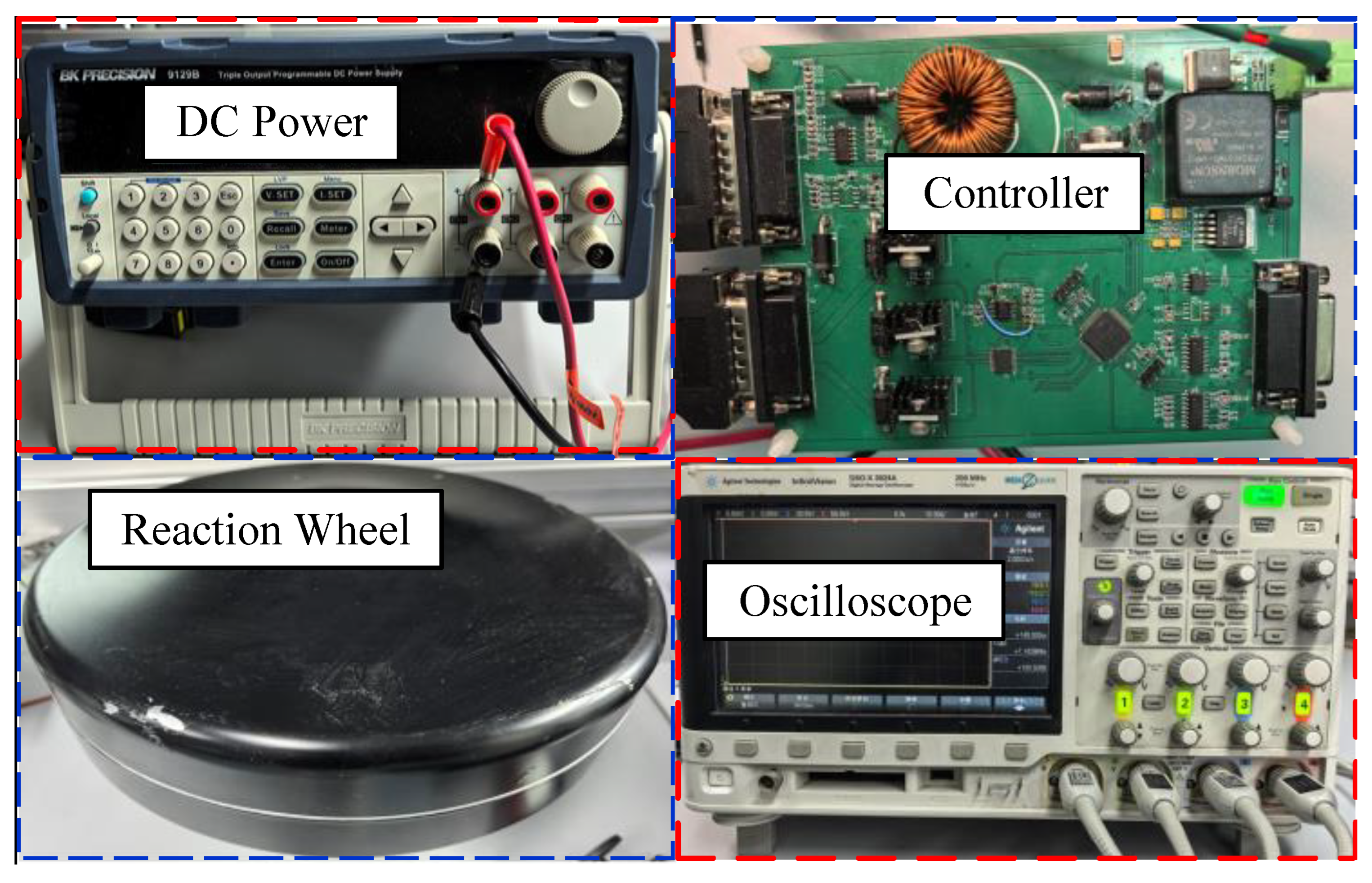

4.1. Experimental Platform and Parameters

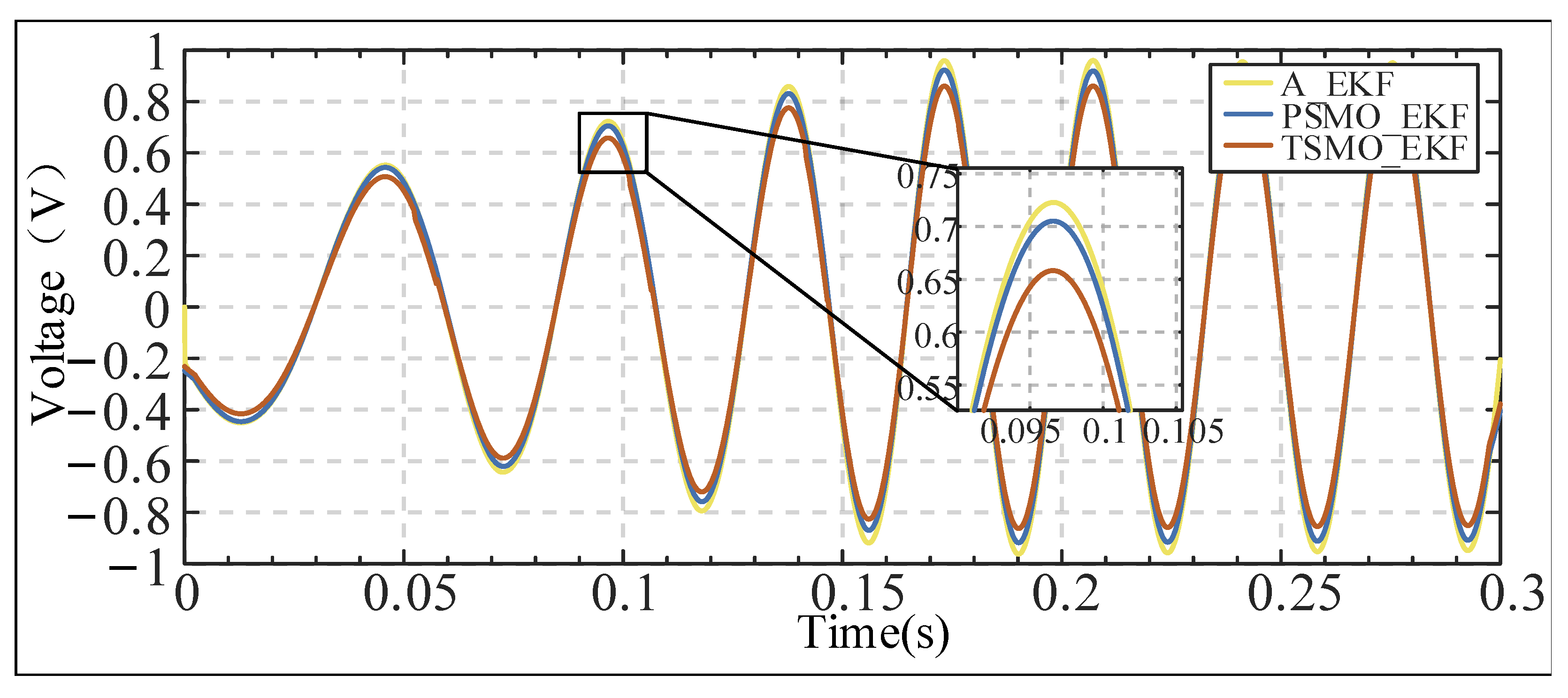

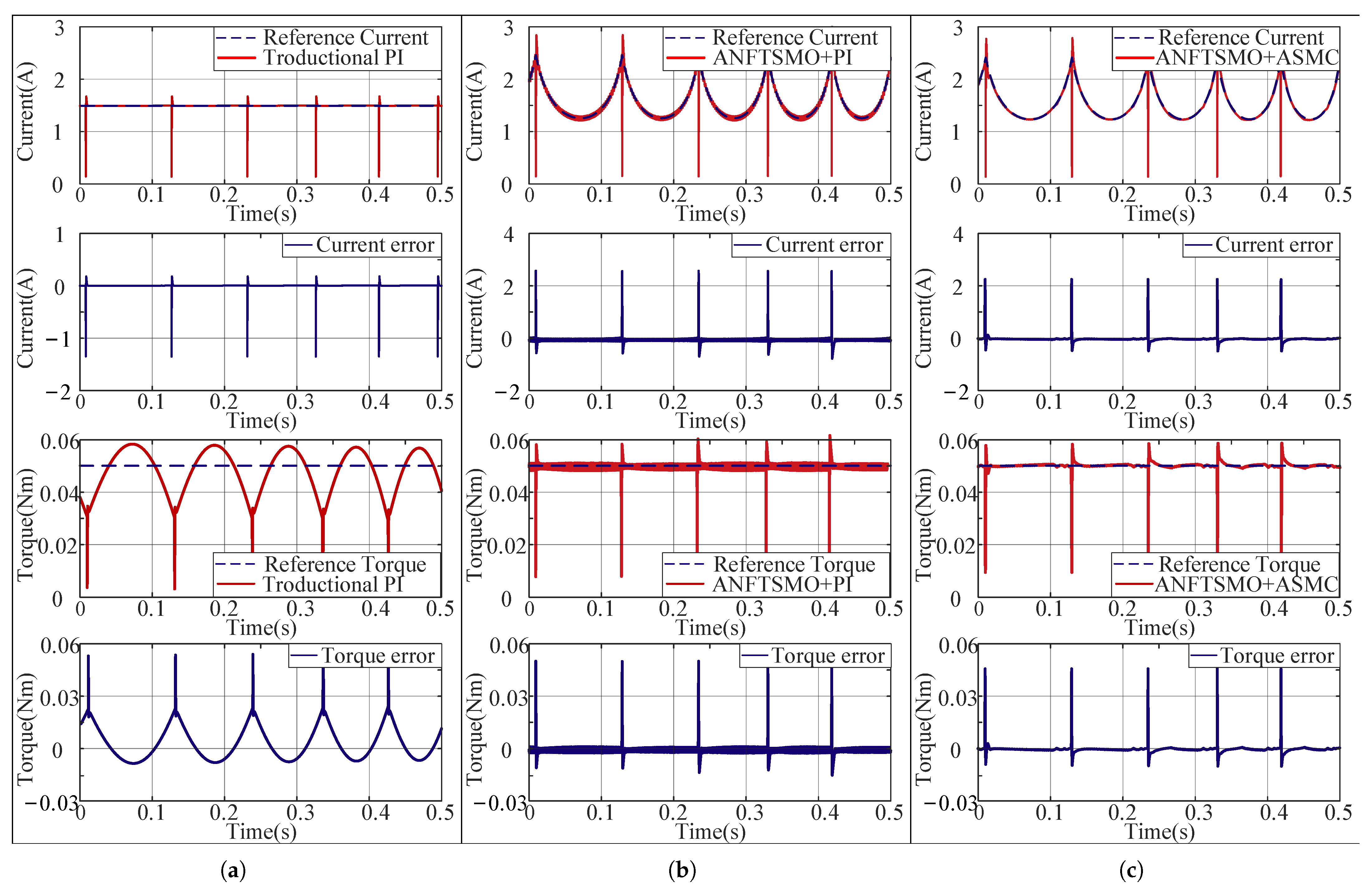

4.2. Simulation and Experimental Validations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANFTSMO | Adaptive Nonsingular Fast Terminal Sliding-Mode Observer |

| ASMC | Adaptive Sliding-Mode Controller |

| Back-EMF | Back-Electromotive Force |

| BLDC | Brushless DC |

| DTC | Direct Torque Control |

| EMI | Electromagnetic Interference |

| PMSM | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor |

| PWM | Pulse-Width Modulation |

References

- Sanfedino, F.; Thiébaud, G.; Alazard, D.; Guercio, N.; Deslaef, N. Advances in fine line-of-sight control for large space flexible structures. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 130, 107961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, J.M.; Barltrop, C.; Berman, S.; Bushman, S.; Dickson, J.; Drain, T.; Engelbrecht, C.; Fugett, D.; Gruel, D.; Hill, S.; et al. Europa Clipper flight system overview. Space Sci. Rev. 2025, 221, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. An AEFA-based optimum design of fuzzy PID controller for attitude control flywheel with BLDC motor. Aerospace 2022, 9, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanfar, M.; Alizadeh Pahlavani, M.R.; Dehestani Kolagar, A.; KoohMaskan, Y. Position control of a permanent magnet brushless DC motor using a model predictive control method with Laguerre functions. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 3551–3564. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.; Wan, Z.; Huang, S.; He, J. Torque ripple suppression in non-commutation interval of the coreless brushless DC motor based on unipolar PWM predictive control. IET Power Electron. 2024, 17, 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Gao, S.; Chu, F. Micro-vibration analysis, suppression, and isolation of spacecraft flywheel rotor systems: A review. Vibration 2024, 7, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmouditabar, F.; Vahedi, A.; Takorabet, N. Robust Design of BLDC Motor Considering Driving Cycle. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 1414–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dou, M.; Yan, L. A novel current solution for torque ripple suppression of BLDCM with minimal rotor eddy-current loss. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 2831–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yan, C.; Wang, X. Torque ripple suppression of brushless DC motor drive system based on improved harmonic injection active disturbance rejection control. Sensors 2022, 22, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.I.; Han, J.S.; Park, J.S.; Lim, H.S.; Lee, G.H. Performance improvement of DTC-SVM of PMSM with compensation for the dead time effect and power switch loss based on extended Kalman filter. Electronics 2023, 12, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, X.; Wu, H.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, Z. Torque ripple reduction in BLDC motors using phase current integration and enhanced zero vector DTC. Electronics 2025, 14, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Qu, S.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H. An improved adaptive sliding mode observer for middle- and high-speed rotor tracking. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J. A new reaching law for antidisturbance sliding-mode control of PMSM speed regulation system. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 4117–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, S.; Chenniappan, S.; Nayagi, A.T.; Mahendran, R. Introduction to electric power systems. In Basic Electrical and Instrumentation Engineering; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, D.S.; Shivarudraswamy, R. Loss and efficiency analysis of BLDC motor and universal motor by mathematical modelling in the mixer grinder. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. B 2022, 103, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarso, G.C.; Nallamothu, R.B.; Gopal, R.; Jin, G.G. Strategic slot–pole optimization in electromagnetic coupling with random forest regressor model inspired by response surface methodology. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-S.; Tsai, C.-T.; Hwang, J.-C.; Lin, C.-T.; Lin, Y.-T. Current harmonics suppression of six-phase permanent-magnet synchronous motor drives using back-electromotive-force harmonics compensation. Energies 2024, 17, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fan, M.; Qiao, J.; He, X.; Yang, M.; Tuo, J. Analytical prediction of electromagnetic performance for surface-embedded permanent magnet in-wheel machines considering iron’s nonlinearity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, F.; Jin, S.; Sun, Y. Study on performance of low-speed high-torque permanent magnet synchronous motor with dynamic eccentricity rotor. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popsi, N.R.S.; Anik, A.; Verma, R.; Viana, C.; Iyer, K.L.V.; Kar, N.C. Influence of electric motor manufacturing tolerances on end-of-line testing: A review. Energies 2024, 17, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivanc, O.C.; Ozturk, S.B.; Toliyat, H.A. On-line dead time compensator for PMSM drive based on current observer. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 25, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liang, D.; Liu, K. Online Parameter Estimation for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: An Overview. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59059–59084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghlache, A.; Djerioui, A.; Mekki, H.; Zeghlache, S.; Benkhoris, M.F. Robust Sensorless PMSM Control with Improved Back-EMF Observer and Adaptive Parameter Estimation. Electronics 2025, 14, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rated speed (r/min) | 6000 | Armature inductance L (μH) | 100 |

| DC bus voltage (V) | 24 | Number of pole pairs | 8 |

| Rotor inertia J (kg·m2) | 0.00956 | Back-EMF constant (V/(r/min)) | 0.00435 |

| Armature resistance R () | 0.942 | Maximum current (A) | 2.5 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| j | 10 | ||

| k | 5 | 1000 | |

| p | 1 | 2 | |

| q | 2 | 50 | |

| 5 | 0.1 | ||

| 5 | |||

| 0.1 |

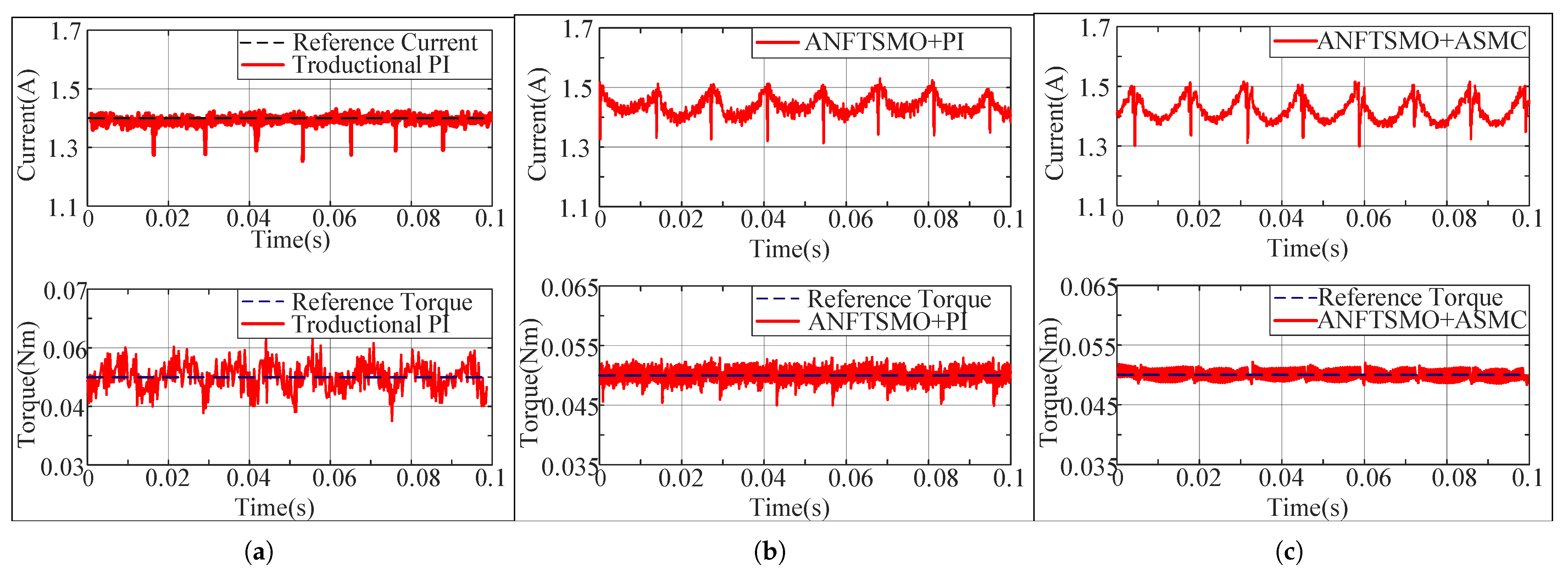

| Control Strategy | Peak-to-Peak Ripple (N·m) | Steady-State Error (%) | Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Constant Current PI | 0.020 | 13.3 | - |

| ANFTSMO + PI | 0.009 | 6.0 | 55.0 |

| ANFTSMO + ASMC | 0.004 | 2.7 | 80.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Wen, T.; Li, H.; Chen, X. Torque Ripple Suppression in BLDC Reaction Wheels Using Adaptive Composite Control Strategy Under Non-Ideal Back-EMF. Actuators 2026, 15, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010028

Wang Z, Li H, Wen T, Li H, Chen X. Torque Ripple Suppression in BLDC Reaction Wheels Using Adaptive Composite Control Strategy Under Non-Ideal Back-EMF. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhicheng, Haitao Li, Tong Wen, Haitao Li, and Xiangwen Chen. 2026. "Torque Ripple Suppression in BLDC Reaction Wheels Using Adaptive Composite Control Strategy Under Non-Ideal Back-EMF" Actuators 15, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010028

APA StyleWang, Z., Li, H., Wen, T., Li, H., & Chen, X. (2026). Torque Ripple Suppression in BLDC Reaction Wheels Using Adaptive Composite Control Strategy Under Non-Ideal Back-EMF. Actuators, 15(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010028