RBF-NN Supervisory Integral Sliding Mode Control for Motor Position Tracking with Reduced Switching Gain

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A systematic method is proposed for reducing the switching gain of an ISMC via a simplified RBF-NN structure that utilizes only the reference input, with the sliding variable serving as the training signal.

- The proposed control architecture enables the RBF-NN to learn the equivalent disturbance online without requiring explicit disturbance models or high-gain observers, thereby addressing potential instability issues.

- Comprehensive validation is performed through comparative simulations and laboratory experiments against two baseline approaches: a conventional ISMC and a DOBC-based cascade P–PI controller.

- Experimental results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in terms of tracking accuracy, disturbance rejection, and switching gain reduction, particularly under scenarios involving parameter uncertainties and time-varying disturbances.

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. System Description

2.2. Integral Sliding Mode Control (ISMC)

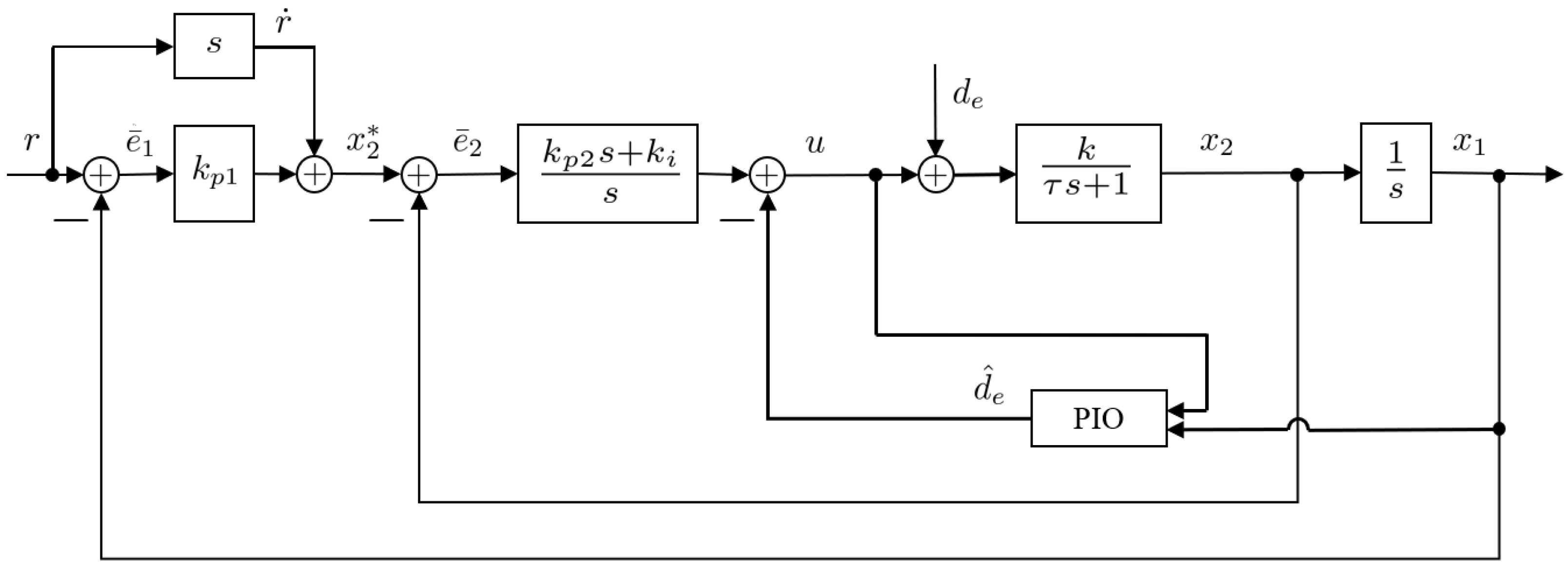

2.3. PIO–Based P–PI Cascade Control

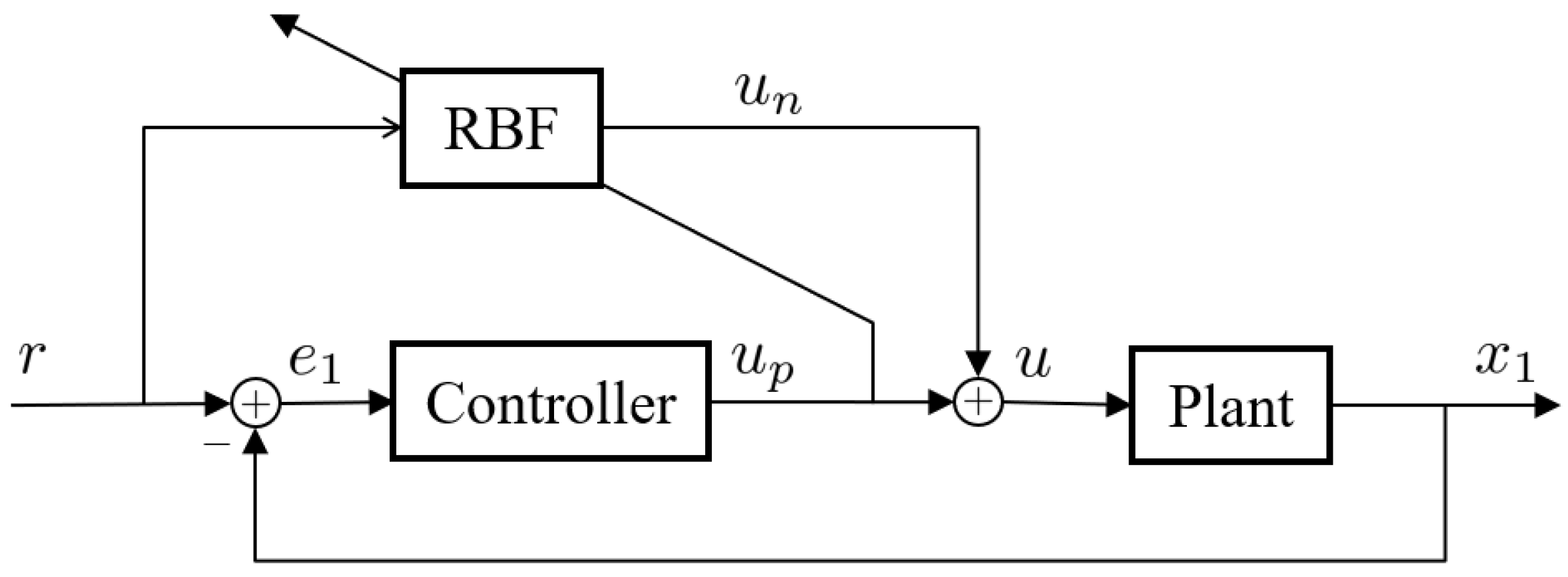

3. Design of the Proposed RBF–NN–Based Controller

4. Performance Evaluation

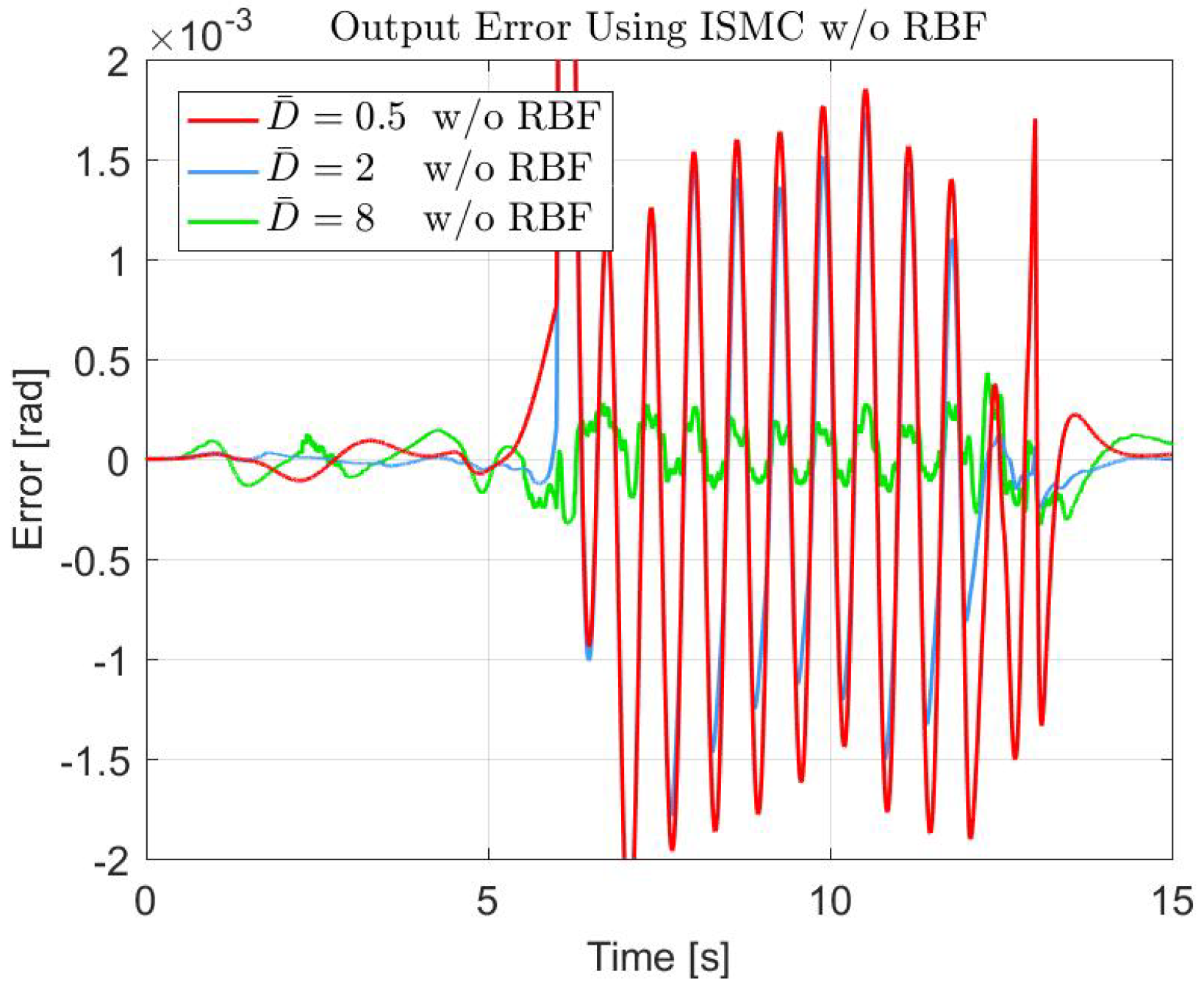

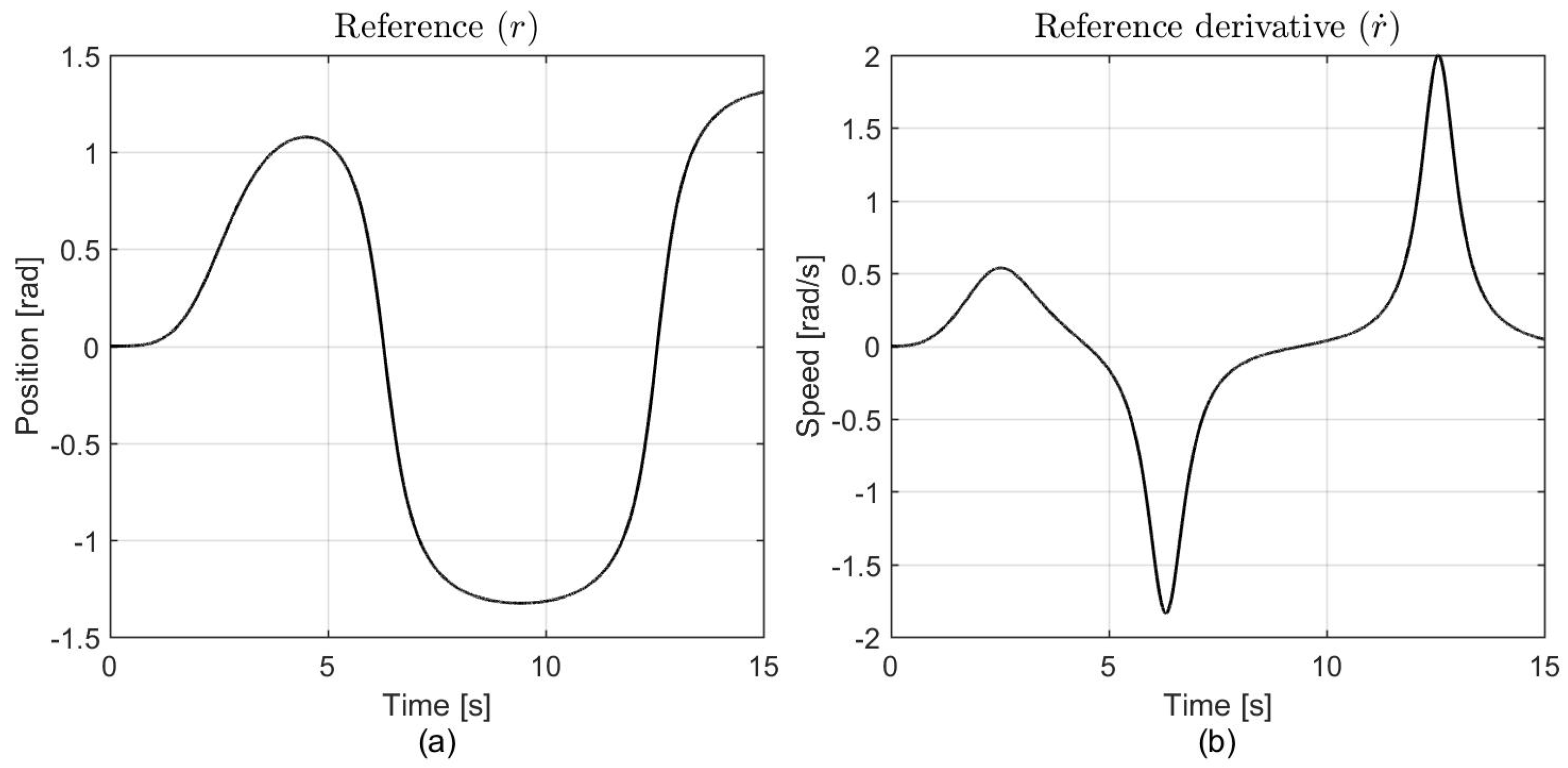

4.1. Simulation Results

4.2. Experimental Setup

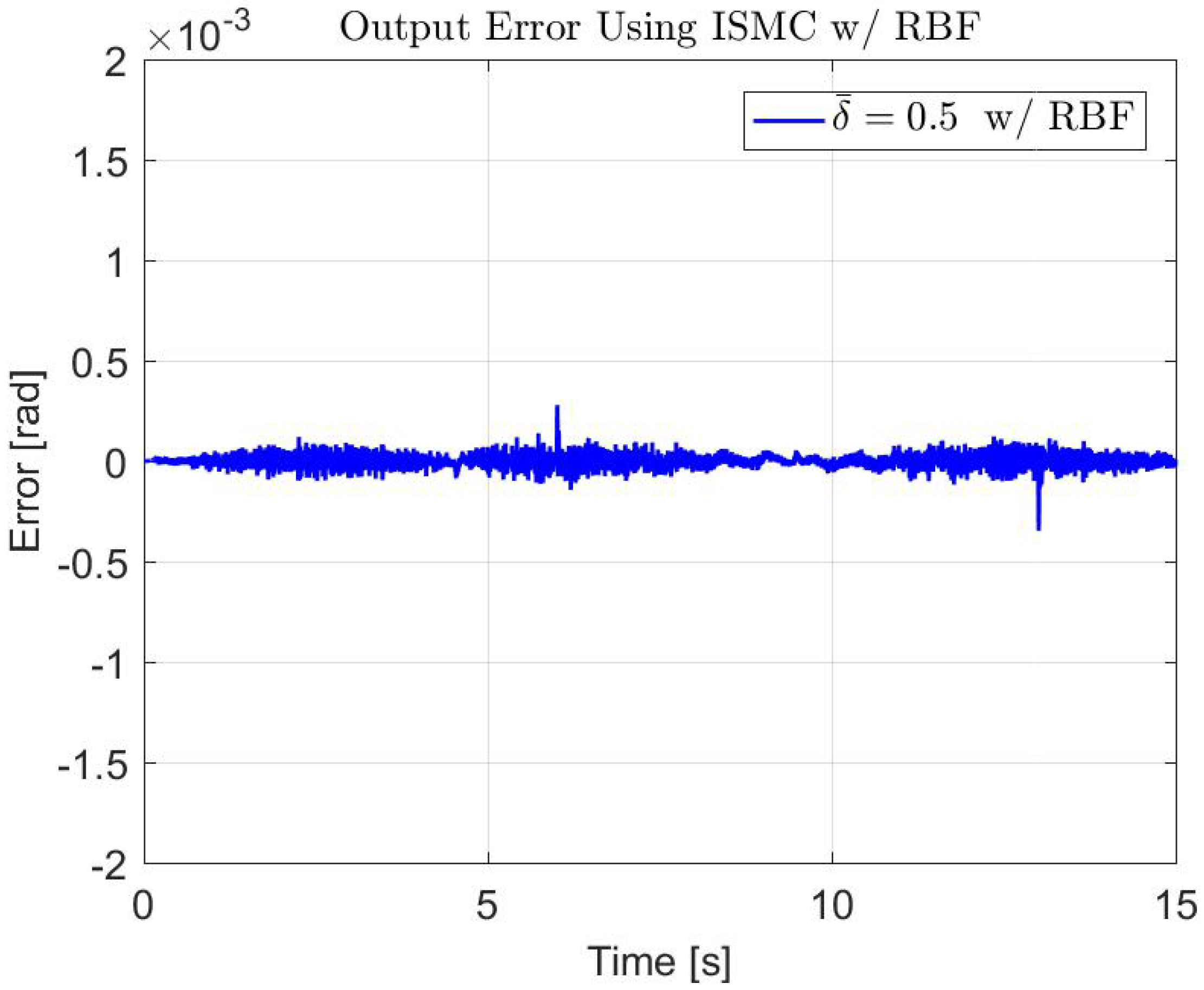

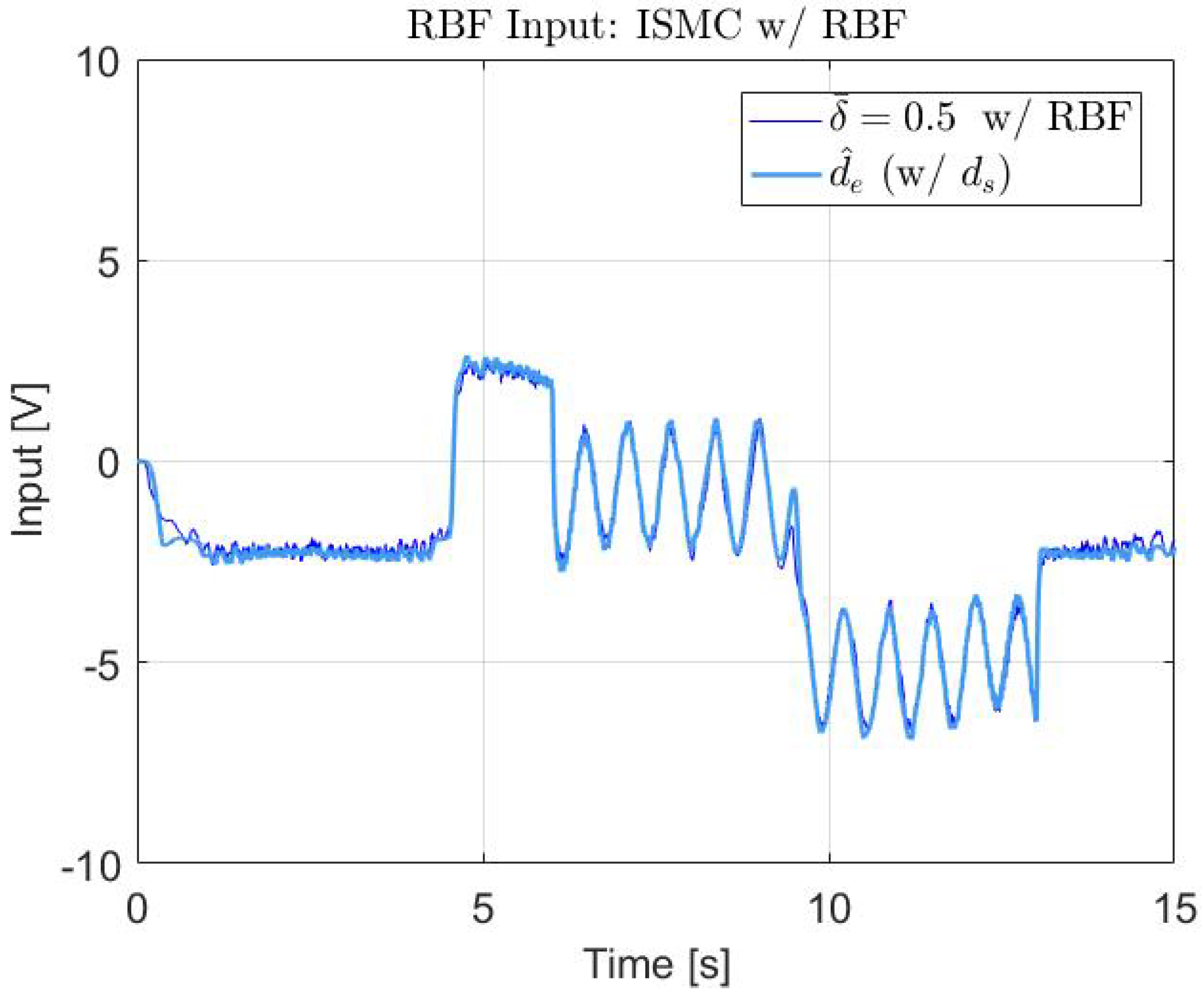

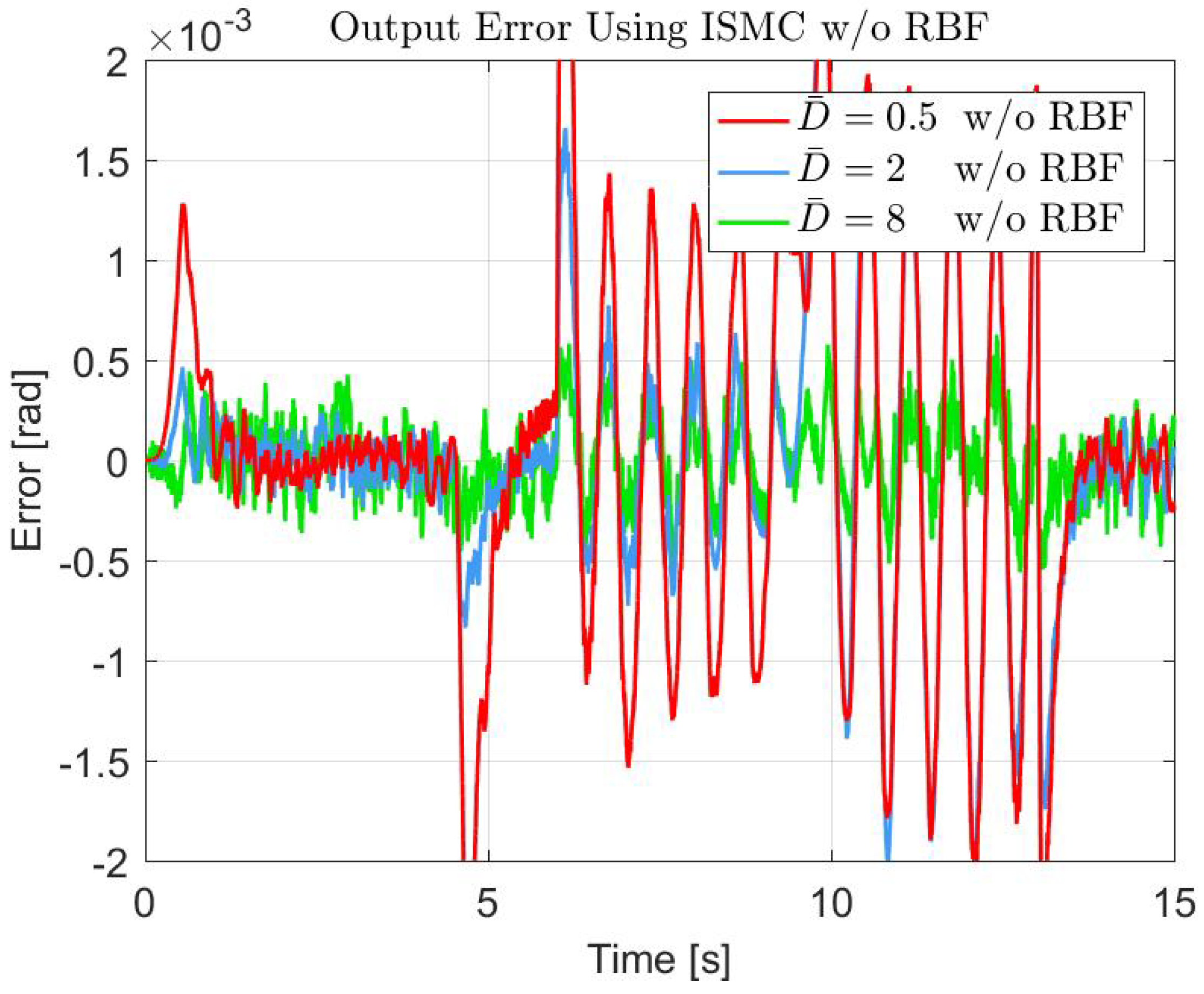

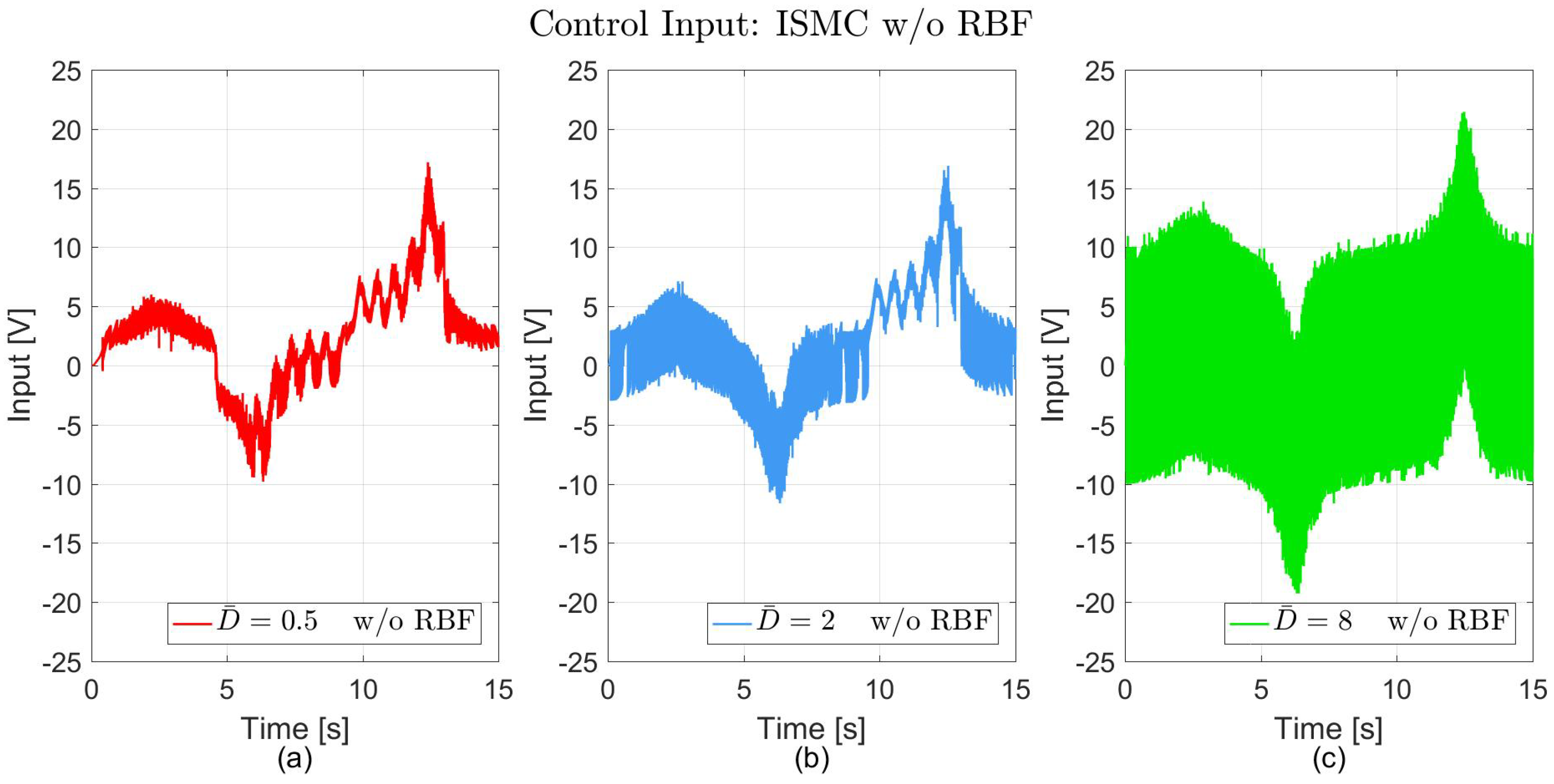

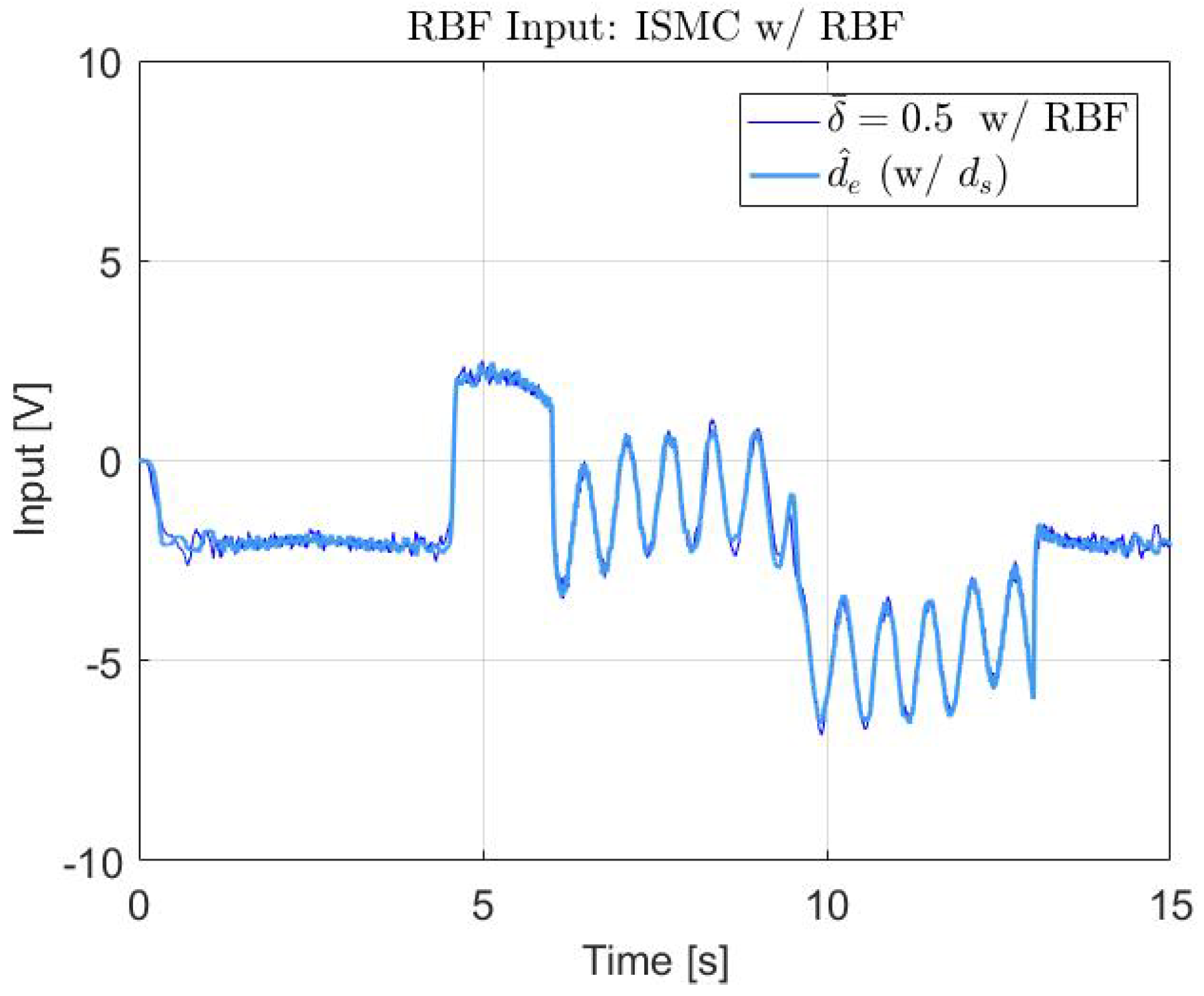

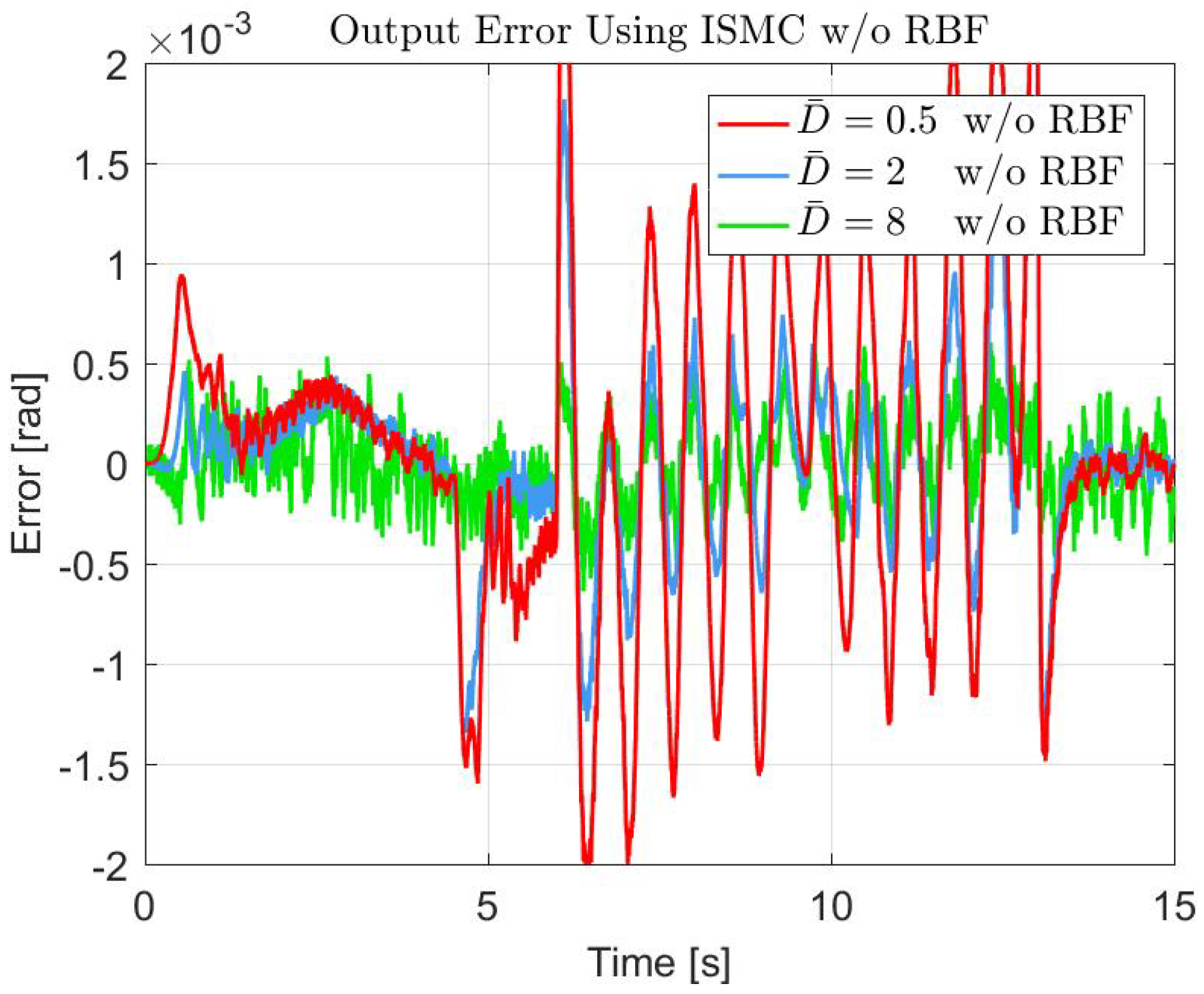

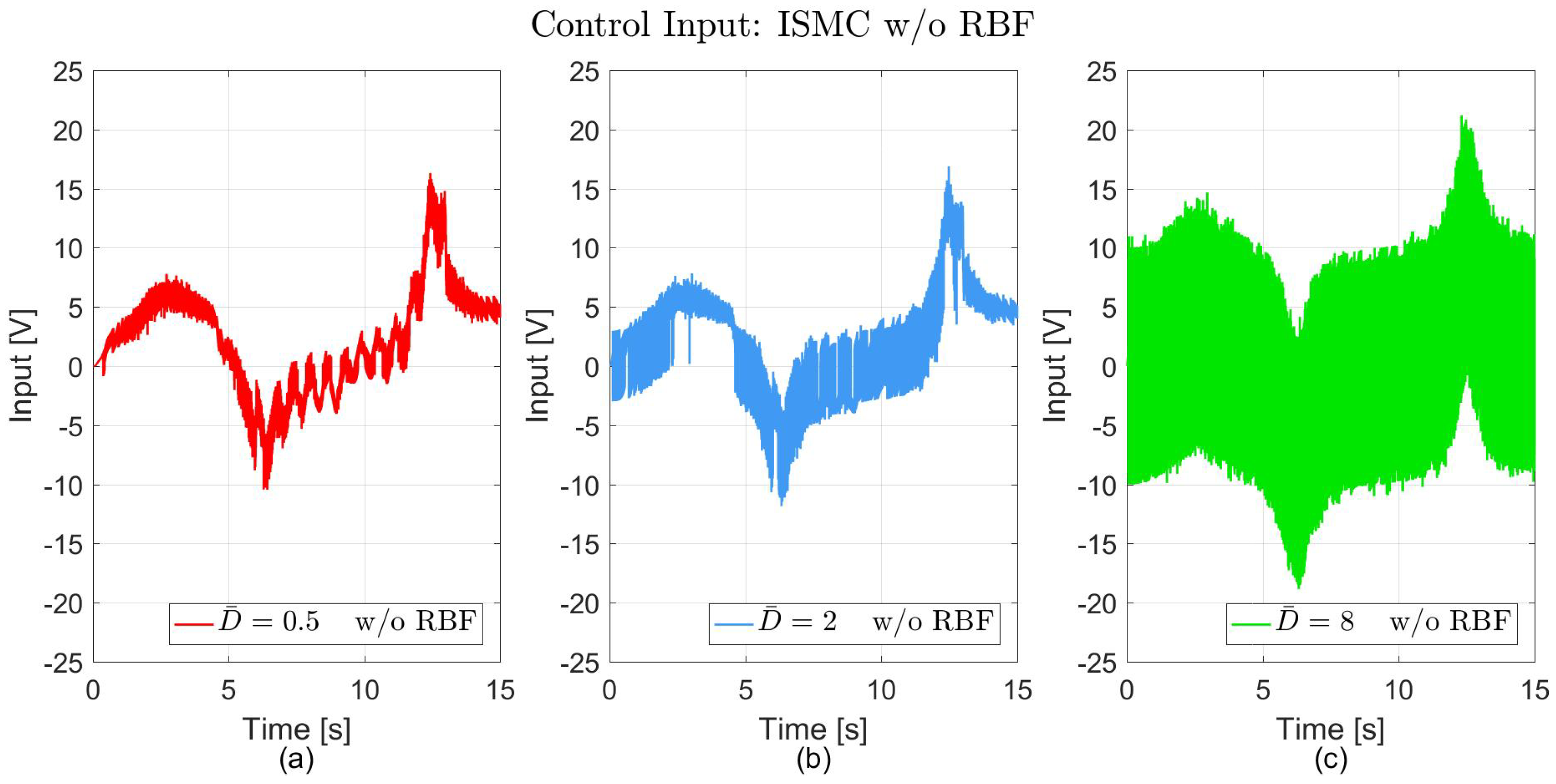

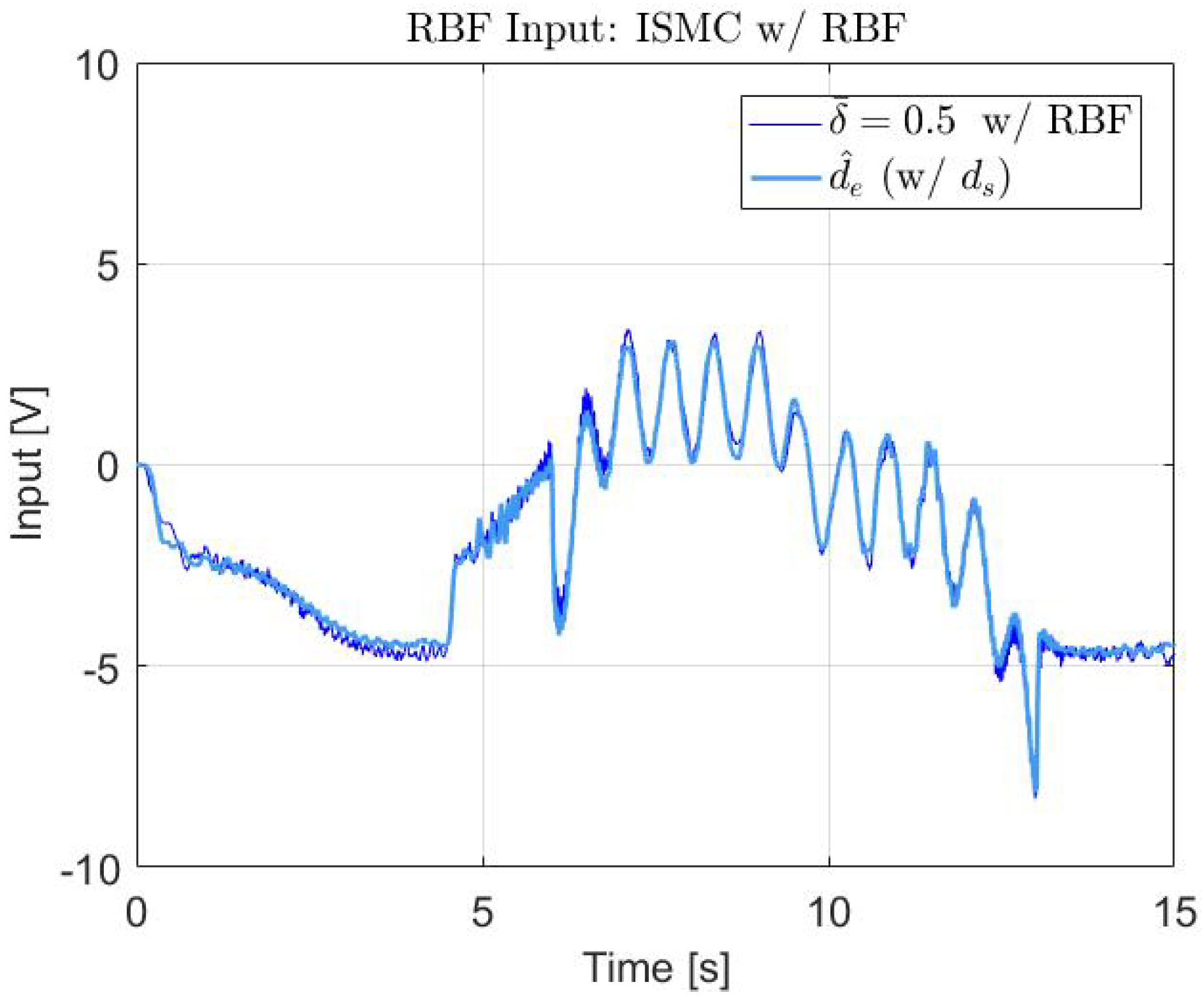

4.3. Experimental Results

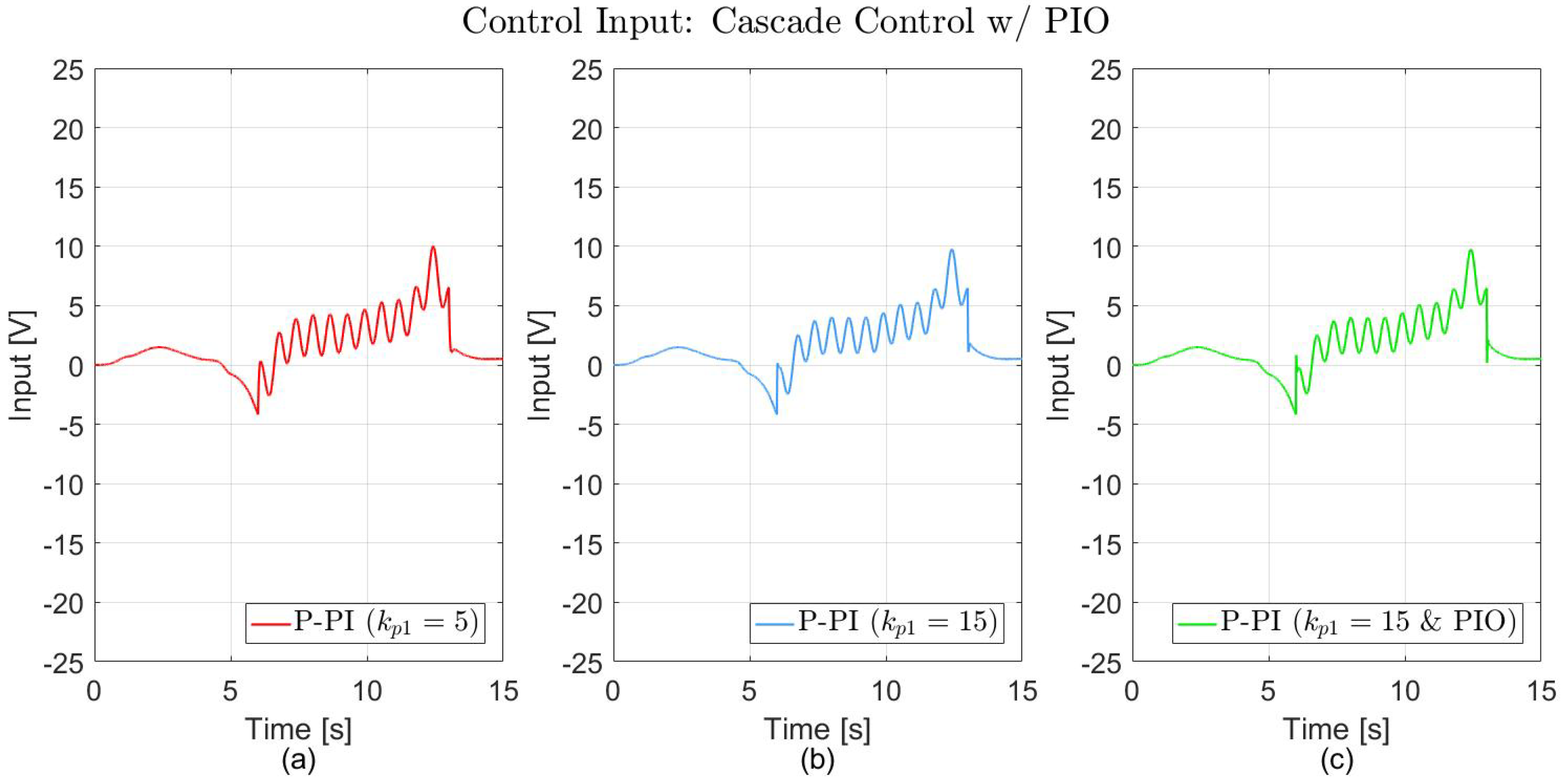

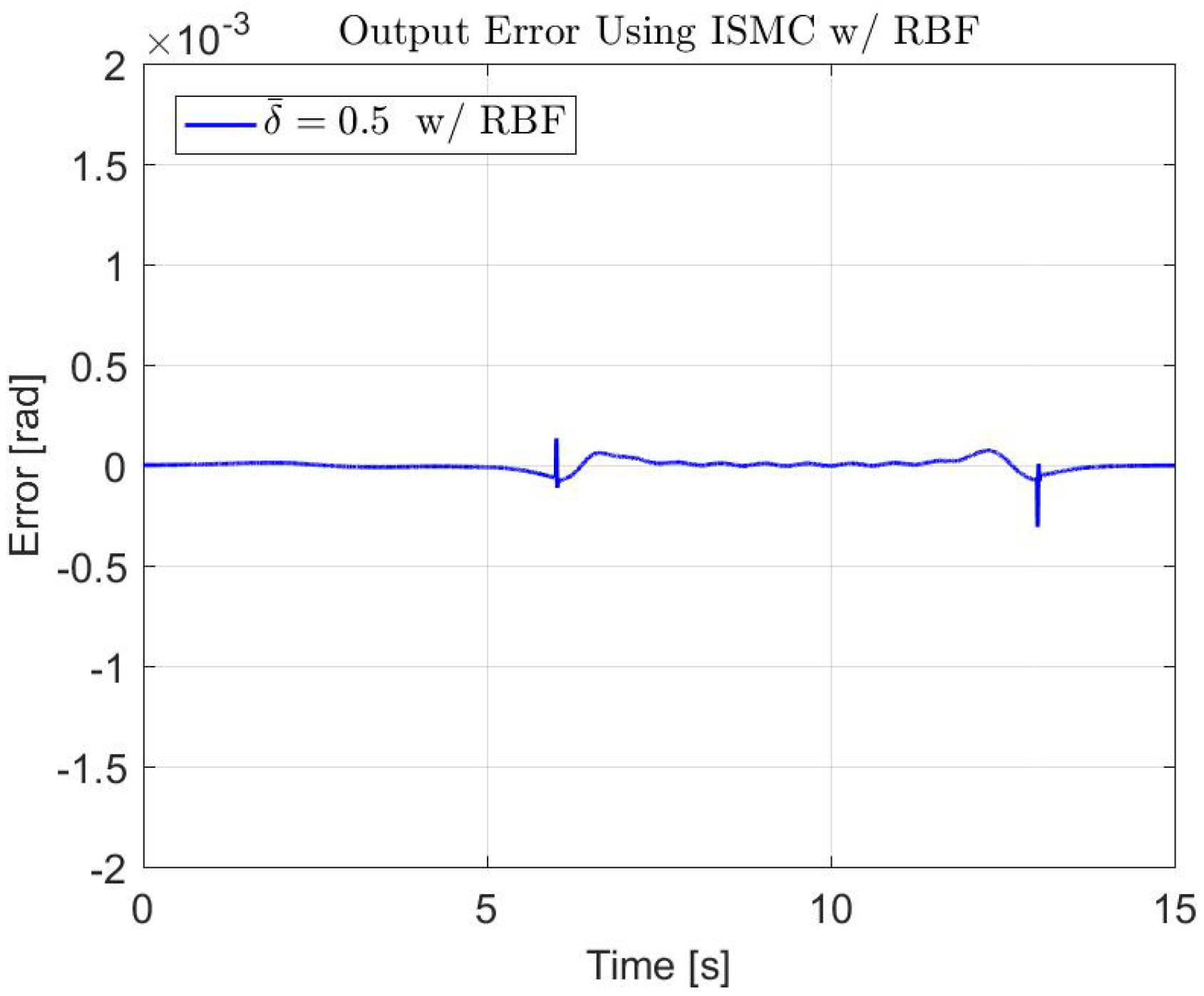

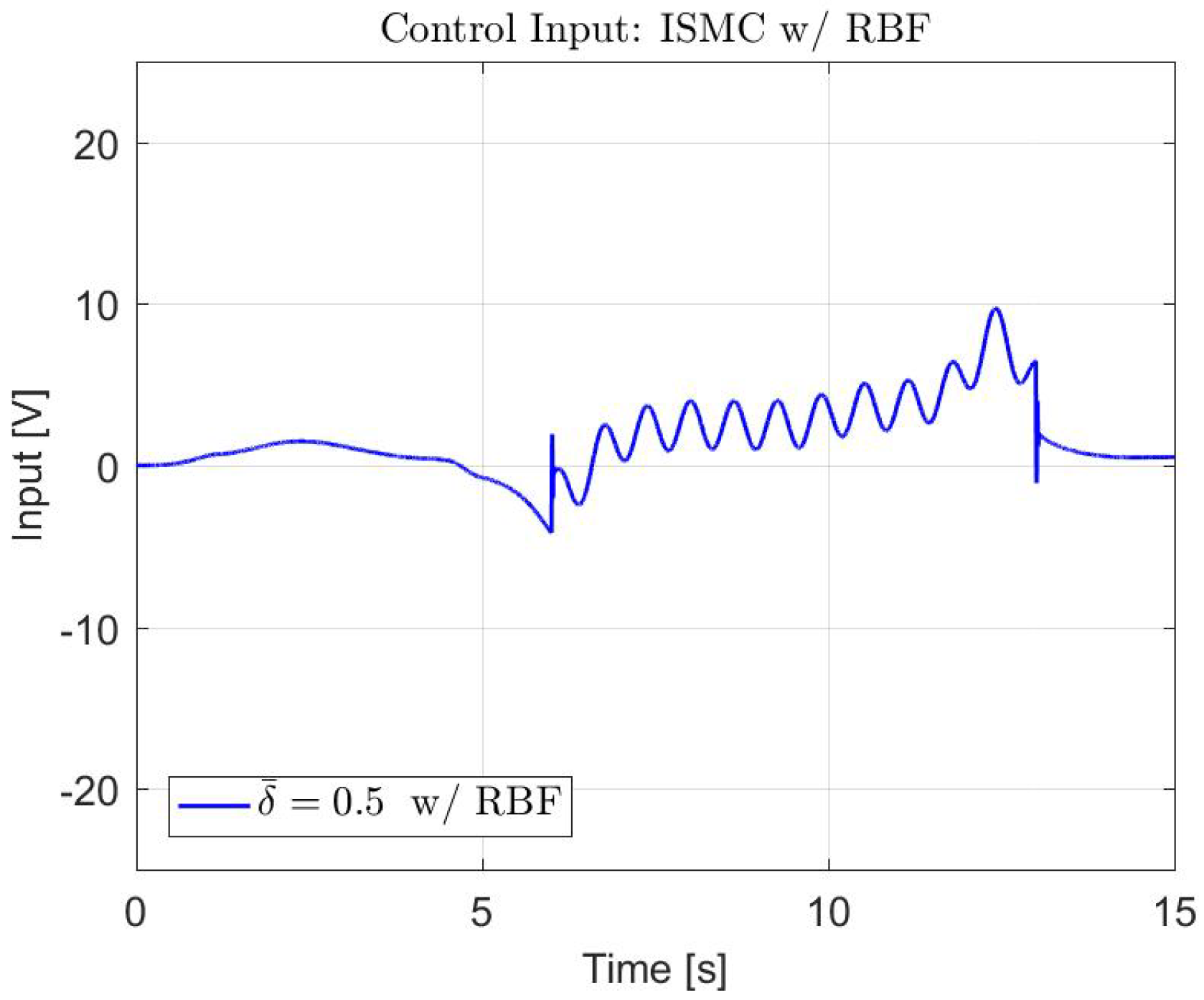

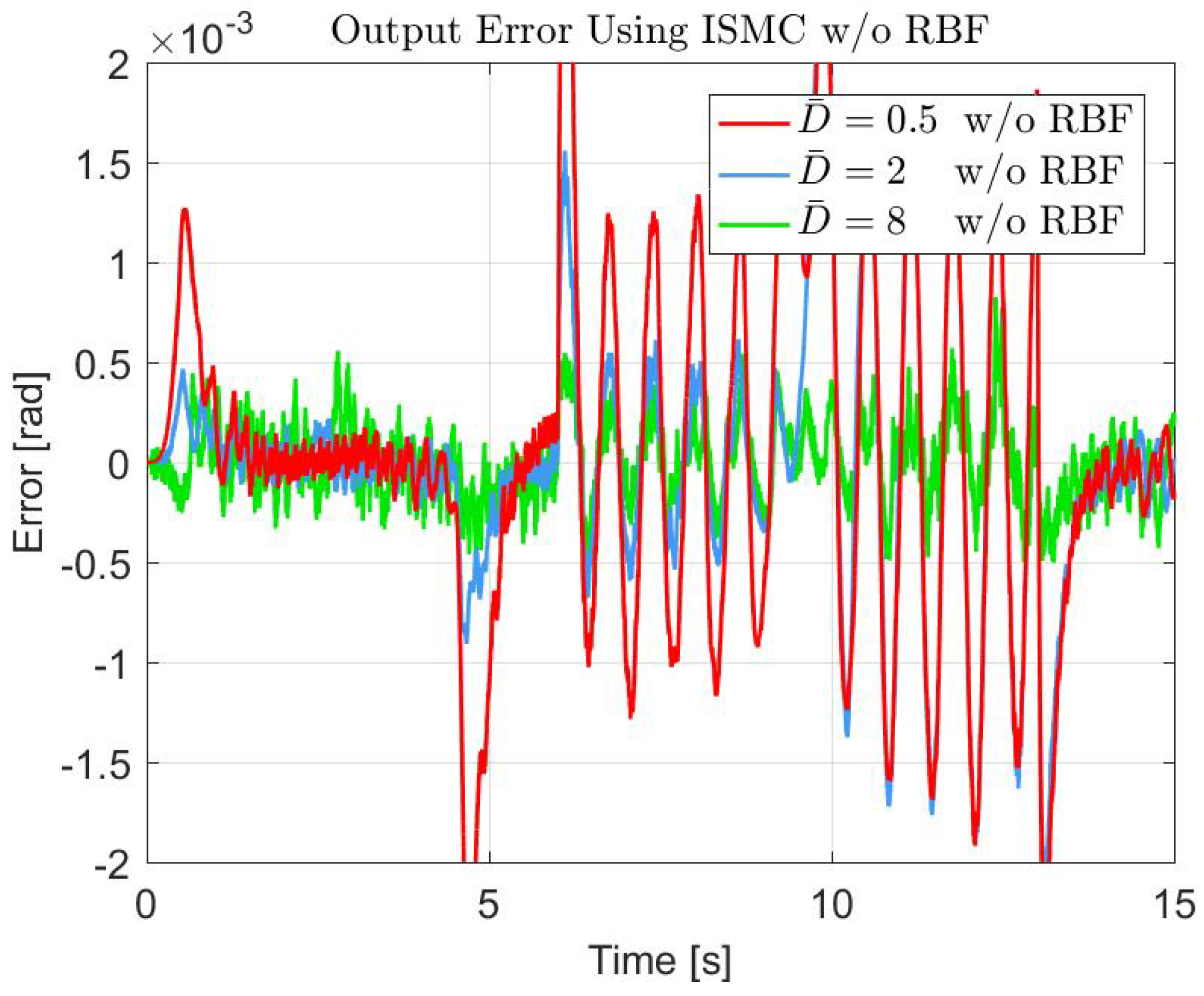

4.3.1. Baseline Experiments Without Payload Mass

4.3.2. Horizontal Rotation Experiment with Payload Mass

4.3.3. Vertical Rotation Experiment with Payload Mass

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISMC | Integral Sliding Mode Control |

| DOBC | Disturbance Observer-Based Control |

| RBF-NN | Radial Basis Function Neural Network |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| P–PI | Proportional–Proportional–Integral Controller |

| PIO | Proportional–Integral Observer |

| EMF | Electromotive Force |

| DC | Direct Current |

| PWM | Pulse Width Modulation |

References

- Sul, S.-K. Control of Electric Machine Drive Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 88. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Y.I.; Kim, I.H.; Choi, D.S.; Shim, H. Robust cascade control of electric motor drives using dual reduced-order PI observer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 3672–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Le, K.M.; Tran, H.N.; Jeon, J.W. An adaptive sliding-mode controller with a modified reduced-order proportional integral observer for speed regulation of a permanent magnet synchronous motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 7181–7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Y. High-accuracy sensorless control of permanent magnet linear synchronous motors for variable speed trajectories. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 4396–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, M.; Kokotovic, P.V.; Kanellakopoulos, I. Nonlinear and Adaptive Control Design; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H.K. Nonlinear Systems, 3rd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, H.; Park, G.; Joo, Y.; Back, J.; Jo, N.H. Yet another tutorial of disturbance observer: Robust stabilization and recovery of nominal performance. Control Theory Technol. 2016, 14, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyildiz, E.; Oboe, R.; Ohnishi, K. Disturbance observer-based robust control and its applications: 35th anniversary overview. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 2042–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Spurgeon, S. Sliding Mode Control: Theory and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Soh, Y.C.; Shen, J.X. Speed estimation and nonmatched time-varying parameter identification for a DC motor with hybrid sliding-mode observer. IEEE Tran. Ind. Electron. 2013, 60, 5539–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, I.-C.; Kim, K.-H.; Youn, M.-J. Robust nonlinear speed control of PM synchronous motor using boundary layer integral sliding mode control technique. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2000, 8, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-S.; Chiu, C.-W. A stability-guaranteed integral sliding disturbance observer for systems suffering from disturbances with bounded first time derivatives. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2011, 9, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, H.; Wang, M.; Qi, X. An improved sliding mode control using disturbance torque observer for permanent magnet synchronous motor. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 36691–36701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efimov, D.; Polyakov, A.; Fridman, L.; Perruquetti, W.; Richard, J.-P. Delayed sliding mode control. Automatica 2016, 64, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, A.; Tanelli, M.; Ferrara, A. Switched/time-based adaptation for second-order sliding mode control. Automatica 2016, 64, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, L. Sensorless vector control of permanent magnet synchronous linear motor based on self-adaptive super-twisting sliding mode controller. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 44998–45011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.H.; Son, Y.I. Regulation of a DC/DC boost converter under parametric uncertainty and input voltage variation using nested reduced-order PI observers. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, N.D.; Kim, D.H.; Yang, S.J.; Son, Y.I. Boundary conditions for transient and robust performance of reduced-order model-based state feedback controller with PI observer. Energies 2021, 14, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Sandberg, I.W. Universal approximation using radial-basis-function networks. Neural Comput. 1991, 3, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Radial Basis Function (RBF) Neural Network Control for Mechanical Systems: Design, Analysis and Matlab Simulation; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Lin, G.; Ji, W.; Wang, L. RBF neural network-based supervisor control for maglev vehicles on an elastic track with network time delay. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, F.; Sun, W.; Gu, J.; Yao, B. RBF-neural-network-based adaptive robust control for nonlinear bilateral teleoperation manipulators with uncertainty and time delay. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 25, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, H.; Zheng, G.; Zou, J.; Xin, X.; Guo, L. Adaptive decoupling control using radial basis function neural network for permanent magnet synchronous motor considering uncertain and time-varying parameters. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 112323–112332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, H.; Lee, C.H.T. Online-trained radial basis function neural network compensator for current harmonics suppression of electric drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 15488–15498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Shang, D.; Ma, Y.; Cao, W.; Shang, W.; Wu, X. Modeling and rotation control of servo system with flexible structure based on new deformation description. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 29, 4582–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mei, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Liu, B.; Lu, H. Adaptive neural sliding mode control of an uncertain permanent magnet linear motor system with unknown input backlash in laser processing. Inf. Sci. 2024, 680, 121087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhang, C.; Yi, F.; Lv, P.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. RBFNN-based adaptive integral sliding mode feedback and feedforward control for a lower limb exoskeleton robot. Electronics 2024, 13, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ye, Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y. Adaptive high-order sliding-mode low-speed control with RBF neural network nonlinear disturbance observer for PMSM drive system. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 10865–10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanastrom, K.; Canudas-de-Wit, C. Revisiting the LuGre friction model. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2008, 28, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamayun, M.T.; Edwards, C.; Alwi, H. Fault Tolerant Control Schemes Using Integral Sliding Modes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vacchini, E.; Sacchi, N.; Incremona, G.P.; Ferrara, A. Design of a deep neural network-based integral sliding mode control for nonlinear systems under fully unknown dynamics. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2023, 7, 1789–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yao, B. Adaptive robust control of mechanical systems with non-linear dynamic friction compensation. Int. J. Control 2008, 81, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.H.; Son, Y.I. A practical two-step friction determination for motion control using LuGre model. IEICE Trans. Fundam. 2015, E98-A, 890–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RE 35 and Encoder MR Type L Details. 2 January 2026. Available online: https://www.maxongroup.com/maxon/view/product/motor/dcmotor/re/re35/323890 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

| Controller | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| P–PI | 5 → 15 | |

| 11.3560 → 43.0981 | ||

| 198.3888 → 1785.4990 | ||

| PIO | ||

| ISMC | 5 | |

| 15 | ||

| 85 | ||

| 0.5, 2, 8 | ||

| 0.5 | ||

| RBF | c | |

| b | ||

| 10 | ||

| Uncertainty Component | Symbol | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| LuGre Model | 0.1 | bristle stiffness | |

| 0.001 | bristle damping | ||

| viscous friction coefficient | |||

| Coulomb friction level | |||

| 0.022 | stiction friction force | ||

| 0.1 | Stribeck velocity | ||

| External Disturbance |

| Components | Specification | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Motor (Maxon RE-35) | Power | 90 W |

| Nominal voltage | 24 V | |

| Nominal current | 3.81 A | |

| Nominal speed | 6970 rpm | |

| Encoder (Encoder MR, Type L) | CPR | 2000 |

| Number of channels | 3 | |

| Max. operating frequency | 200 kHz | |

| Motor Driver (L298N motor driver) | Nominal operating voltage | 24 V |

| Output current | 2 A | |

| Max. PWM frequency | 40 kHz | |

| Control Board (Nucleo F767ZI) | MCU type | 32-bit ARM Cortex-M7 |

| Operating voltage | 3.3 V | |

| Clock speed | 216 MHz |

| Controller | Switching Gain | RMS of u | Normed Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| P–PI w/ PIO | – | 5.0721 | |

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 0.5 | 5.1745 | |

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 2 | 5.3086 | |

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 8 | 9.7831 | |

| ISMC w/ RBF (Proposed) | = 0.5 | 5.0831 |

| Controller | Switching Gain | RMS of u | Normed Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 0.5 | 4.8227 | |

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 2 | 4.9918 | |

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 8 | 9.6867 | |

| ISMC w/ RBF (Proposed) | = 0.5 | 4.8412 |

| Controller | Switching Gain | RMS of u | Normed Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 0.5 | 4.9237 | |

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 2 | 4.9812 | |

| ISMC w/o RBF | = 8 | 9.8205 | |

| ISMC w/ RBF (Proposed) | = 0.5 | 5.1465 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Son, Y.I.; Cho, H. RBF-NN Supervisory Integral Sliding Mode Control for Motor Position Tracking with Reduced Switching Gain. Actuators 2026, 15, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010029

Son YI, Cho H. RBF-NN Supervisory Integral Sliding Mode Control for Motor Position Tracking with Reduced Switching Gain. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleSon, Young Ik, and Haneul Cho. 2026. "RBF-NN Supervisory Integral Sliding Mode Control for Motor Position Tracking with Reduced Switching Gain" Actuators 15, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010029

APA StyleSon, Y. I., & Cho, H. (2026). RBF-NN Supervisory Integral Sliding Mode Control for Motor Position Tracking with Reduced Switching Gain. Actuators, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010029