Nature-Inspired Pathogen and Cancer Protein Covalent Inhibitors: From Plants and Other Natural Sources to Drug Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

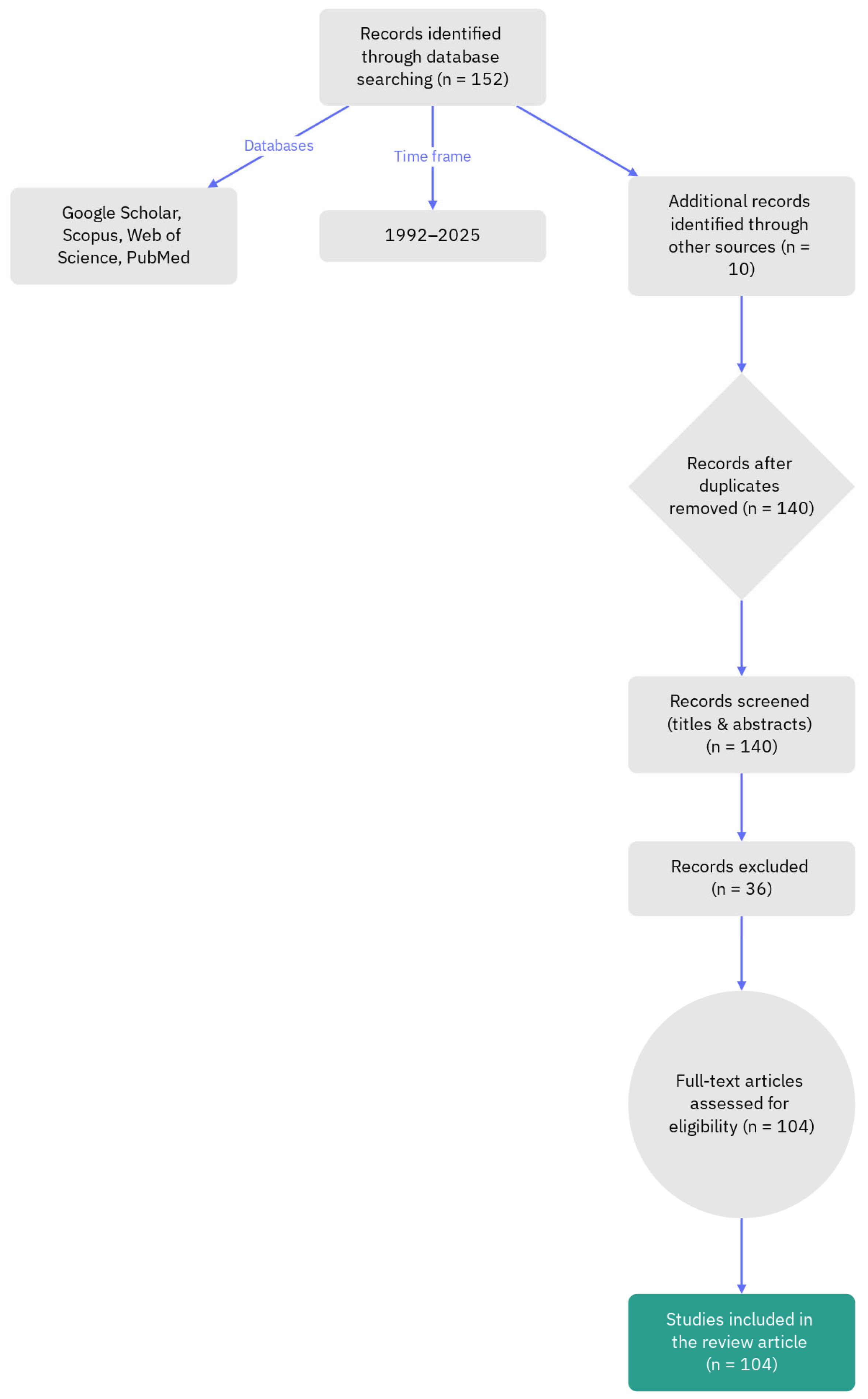

Methodology

2. Covalent Inhibitors from Natural Sources

2.1. Inhibition of Pathogen Enzymes as a Therapeutic Strategy

2.2. Difference Between Covalent and Non-Covalent Enzyme Inhibition

2.3. Covalent Inhibitors from Fungi, Marine Organisms, and Microbes

2.4. Covalent Inhibitors from Plants

3. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| ASK1 | Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 |

| ATPase | Adenosine triphosphatase |

| CDC25A | Cell division cycle 25A phosphatase |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| EM23 | Heliangolide from Elephantopus mollis |

| ERK2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 |

| GLT-1 | Glutamate transporter 1 |

| IKKα | IκB kinase alpha |

| IKKβ | IκB kinase beta |

| IJ-5 | Eudesmanolide from Inula japonica |

| LC-1 | Parthenolide prodrug with enhanced solubility |

| Lys | Lysine |

| LuxE | Acyl-protein synthetase in quorum-sensing pathway |

| LuxS | S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MPC-1 | Modified penicillin compound for enhanced β-lactamase inhibition |

| MurA | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-enolpyruvyltransferase |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PBP | Penicillin-binding protein |

| PHA B | Polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthesis enzyme |

| PKAα | Protein kinase A alpha |

| PP1 | Protein phosphatase 1 |

| PP2A | Protein phosphatase 2A |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PSMA | Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| SERCA | Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase |

| TRPA1 | Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 |

References

- Robertson, J.G. Mechanistic basis of enzyme-targeted drugs. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 5561–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, D.; P Parker, J.; J Marmion, C. Enzyme inhibition as a key target for the development of novel metal-based anti-cancer therapeutics. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. (Former. Curr. Med. Chem.-Anti-Cancer Agents) 2010, 10, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flury, P.; Vishwakarma, J.; Sylvester, K.; Higashi-Kuwata, N.; Dabrowska, A.K.; Delgado, R.; Cuell, A.; Basu, R.; Taylor, A.B.; de Oliveira, E.G. Azapeptide-Based SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors: Design, Synthesis, Enzyme Inhibition, Structural Determination, and Antiviral Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 19339–19376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotschafer, J.C.; Ostergaard, B.E. Combination β-lactam and β-lactamase-inhibitor products: Antimicrobial activity and efficiency of enzyme inhibition. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 1995, 52 (Suppl. S2), S15–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, D.; Cheng, X. Recent advances in covalent drug discovery. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Grams, R.J.; Hsu, K.-L. Advancing Covalent Ligand and Drug Discovery beyond Cysteine. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 6653–6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridoon; Zheng, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.J. Key Advances in the Development of Reversible Covalent Inhibitors; Taylor & Francis: Oxford, UK, 2025; Volume 17, pp. 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.-Y.; Xiao, M.-Z.; Hao, W.-C.; Yang, Z.-S.; Liu, X.-R.; Xu, D.-S.; Peng, Z.-X.; Zhang, L.-Y. Drug resistance in breast cancer: Mechanisms and strategies for management. Drug Resist. Updates 2025, 83, 101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, G.N. Therapeutic Convergence in Neurodegeneration: Natural Products, Drug Repurposing, and Biomolecular Targets. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; Roviello, G.N. Precision Therapeutics Through Bioactive Compounds: Metabolic Reprogramming, Omics Integration, and Drug Repurposing Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittova, V.; Pirtskhalava, M.; Tsetskhladze, Z.R.; Makalatia, K.; Loladze, A.; Bebiashvili, I.; Barblishvili, T.; Gogoladze, A.; Roviello, G.N. Antioxidant Potential and Antibacterial Activities of Caucasian Endemic Plants Sempervivum transcaucasicum and Paeonia daurica subsp. mlokosewitschii Extracts and Molecular In Silico Mechanism Insights. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, A.P.; Piccialli, I.; Greco, F.; D’Errico, S.; Nolli, M.G.; Borbone, N.; Oliviero, G.; Roviello, G.N. Nanostructural Modulation of G-Quadruplex DNA in Neurodegeneration: Orotate Interaction Revealed Through Experimental and Computational Approaches. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e16296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, T.; Simonyan, H.M.; Stepanyan, L.; Tsaturyan, A.; Vicidomini, C.; Pastore, R.; Guerra, G.; Roviello, G.N. Neuroprotective Properties of Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): State of the Art and Future Pharmaceutical Applications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugisa, S.; Murahari, M. Covalent Inhibitors-An Overview of Design Process, Challenges and Future Directions. Curr. Org. Chem. 2025, 29, 1424–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Zhu, G.-H.; Chen, P.-C.; Liu, W.; Hu, X.-P.; Song, F.-F.; Pan, Z.-F.; Zheng, S.-L. Uncovering the naturally occurring covalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro from the Chinese medicine sappanwood and deciphering their synergistic anti-Mpro effects. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 342, 119397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curieses Andrés, C.M.; Lobo, F.; Pérez de Lastra, J.M.; Bustamante Munguira, E.; Andrés Juan, C.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Cysteine Alkylation in Enzymes and Transcription Factors: A Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Huma, Z.E.; Duncan, D. Reversible Covalent Inhibition—Desired Covalent Adduct Formation by Mass Action. ACS Chem. Biol. 2024, 19, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanaullah, B.; Truong, N.V.; Nguyen, T.-K.; Han, E.-T. Combating malaria: Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system to conquer drug resistance. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Lee, P.-Y.; Stollar, V.; Li, M.-L. Antiviral therapy targeting viral polymerase. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 1339–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancheri, P.; Di Sabatino, A.; Corazza, G.R.; MacDonald, T.T. Proteases and the gut barrier. Cell Tissue Res. 2013, 351, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, S.; Taillandier, D.; Aurousseau, E.; Cherel, Y.; Le Maho, Y.; Arnal, M.; Attaix, D. Gastrointestinal tract protein synthesis and mRNA levels for proteolytic systems in adult fasted rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 1996, 271, E232–E238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnolle, N. Protease inhibition as new therapeutic strategy for GI diseases. Gut 2016, 65, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, M.L.R.; de Oliveira, C.F.R.; Costa, P.M.; Castelhano, E.C.; Silva-Filho, M.C. Adaptive mechanisms of insect pests against plant protease inhibitors and future prospects related to crop protection: A review. Protein Pept. Lett. 2015, 22, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloi, S.J.; Ngara, R. The roles of plant proteases and protease inhibitors in drought response: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1165845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabotič, J.; Kos, J. Microbial and fungal protease inhibitors—Current and potential applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 1351–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, A.; Pal, D.; Kumar, A. Combinatorial therapeutic enzymes to combat multidrug resistance in bacteria. Life Sci. 2024, 353, 122920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban-Chmiel, R.; Marek, A.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Wieczorek, K.; Dec, M.; Nowaczek, A.; Osek, J. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria—A review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clatworthy, A.E.; Pierson, E.; Hung, D.T. Targeting virulence: A new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chai, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, A.; Li, Y. Central Nervous System-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Strooper, B.; Vassar, R.; Golde, T. The secretases: Enzymes with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, G.; Carta, F.; Supuran, C.T. The integrase: An overview of a key player enzyme in the antiviral scenario. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Chi, G. HIV integrase inhibitors as therapeutic agents in AIDS. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007, 17, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, K.; Das, P.; Mamidi, S.; Hurevich, M.; Iosub-Amir, A.; Metanis, N.; Reches, M.; Friedler, A. Covalent Inhibition of HIV-1 Integrase by N-Succinimidyl Peptides. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xue, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z. Comparative Analysis of Pharmacophore Features and Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships for CD 38 Covalent and Non-covalent Inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015, 86, 1411–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljoundi, A.; Bjij, I.; El Rashedy, A.; Soliman, M.E. Covalent versus non-covalent enzyme inhibition: Which route should we take? A justification of the good and bad from molecular modelling perspective. Protein J. 2020, 39, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groll, M.; Huber, R. Substrate access and processing by the 20S proteasome core particle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003, 35, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.; Hayden, P.J.; Will, A.; Wheatley, K.; Coyne, I. Bortezomib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, CD010816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, P.; Dubiella, C.; Groll, M. Covalent and non-covalent reversible proteasome inhibition. Biol. Chem. 2012, 393, 1101–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, B.A.; Tomaszewski, J.E. Proteasome inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015, 96, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akher, F.B.; Farrokhzadeh, A.; Soliman, M.E. Covalent vs. Non-Covalent Inhibition: Tackling Drug Resistance in EGFR–A Thorough Dynamic Perspective. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1800518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.A. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Present and future. Cancer J. 2019, 25, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadman, M.; Burke, J.M.; Cultrera, J.; Yimer, H.A.; Zafar, S.F.; Misleh, J.; Rao, S.S.; Farber, C.M.; Cohen, A.; Yao, H. Zanubrutinib is well tolerated and effective in patients with CLL/SLL intolerant of ibrutinib/acalabrutinib: Updated results. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 4100–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zain, R.; Vihinen, M. Structure-function relationships of covalent and non-covalent BTK inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 694853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, G.; Cai, X.-p.; Deng, J.-w.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, H.-h.; Zheng, M.; Yang, B.; Chen, Z. An overview of COVID-19. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 2020, 21, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Flamholz, A.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers. Elife 2020, 9, e57309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agost-Beltrán, L.; de la Hoz-Rodríguez, S.; Bou-Iserte, L.; Rodríguez, S.; Fernández-de-la-Pradilla, A.; González, F.V. Advances in the development of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. Molecules 2022, 27, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoonor-Williams, E.; Abu-Saleh, A.A.-A.A. Covalent and non-covalent binding free energy calculations for peptidomimetic inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 6746–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Chai, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; He, L.; Sang, Z.; Chen, D.; Zheng, X. The advancements of marine natural products in the treatment of alzheimer’s disease: A study based on cell and animal experiments. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.-Y.; Liu, J.-J.; Wang, C.-D.; Dou, Y.-F.; Lv, J.-H.; Wang, L.-A.; Zhang, J.-X.; Li, Z. Novel polycyclic meroterpenoids with protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitory activity isolated from desert-derived fungi Talaromyces sp. HMT-8. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2025, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallorini, M.; Carradori, S.; Panieri, E.; Sova, M.; Saso, L. Modulation of NRF2: Biological dualism in cancer, targets and possible therapeutic applications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2024, 40, 636–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddraraju, K.V.; Zhang, Z.-Y. Covalent inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Mol. Biosyst. 2017, 13, 1257–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoutte, R.; Winssinger, N. Following the lead from nature with covalent inhibitors. Chimia 2017, 71, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, M.; Choy, J.W.; Gushwa, N.N.; Oses-Prieto, J.A.; Koupparis, K.; Burlingame, A.L.; Renslo, A.R.; McKerrow, J.H.; Taunton, J. Hypothemycin, a fungal natural product, identifies therapeutic targets in Trypanosoma brucei. Elife 2013, 2, e00712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salaski, E.J.; Krishnamurthy, G.; Ding, W.-D.; Yu, K.; Insaf, S.S.; Eid, C.; Shim, J.; Levin, J.I.; Tabei, K.; Toral-Barza, L. Pyranonaphthoquinone lactones: A new class of AKT selective kinase inhibitors alkylate a regulatory loop cysteine. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2181–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuna, K.; Noguchi, N.; Nakada, M. Convergent total synthesis of (+)-ophiobolin A. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9452–9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornienko, A.; La Clair, J.J. Covalent modification of biological targets with natural products through Paal–Knorr pyrrole formation. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, C.A.; Abe, T.; Park, J.; Eubanks, L.M.; Sawada, D.; Kaufmann, G.F.; Janda, K.D. Revisiting AI-2 quorum sensing inhibitors: Direct comparison of alkyl-DPD analogues and a natural product fimbrolide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15584–15585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, D.; Zhu, J. Mechanism of action of S-ribosylhomocysteinase (LuxS). Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004, 8, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dizin, E.; Hu, X.; Wavreille, A.-S.; Park, J.; Pei, D. S-Ribosylhomocysteinase (LuxS) is a mononuclear iron protein. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 4717–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Wu, J.; Xu, H.; Hu, Z.; Huo, Y.; Wang, L. Cryo-EM structure of the fatty acid reductase LuxC–LuxE complex provides insights into bacterial bioluminescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chang, J.H.; Kim, E.-J.; Kim, K.-J. Crystal structure of (R)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase PhaB from Ralstonia eutropha. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 443, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Rehm, B.H. Polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in Caulobacter crescentus: Molecular characterization of the polyhydroxybutyrate synthase. Microbiology 2001, 147, 3353–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Endimiani, A.; Taracila, M.A.; Bonomo, R.A. Carbapenems: Past, present, and future. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4943–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breilh, D.; Texier-Maugein, J.; Allaouchiche, B.; Saux, M.-C.; Boselli, E. Carbapenems. J. Chemother. 2013, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Lloyd, E.P.; Moshos, K.A.; Townsend, C.A. Identification and characterization of the carbapenem MM 4550 and its gene cluster in Streptomyces argenteolus ATCC 11009. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ri, Y.J.; Ri, C.H.; Ho, U.H.; Song, S.R.; Pak, I.S.; Ri, T.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Ri, J.S. Association between intraspecific variability and penicillin production in industrial strain, Penicillium chrysogenum revealed by RAPD and SRAP markers. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Hesek, D.; Suvorov, M.; Lee, W.; Vakulenko, S.; Mobashery, S. A mechanism-based inhibitor targeting the DD-transpeptidase activity of bacterial penicillin-binding proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 16322–16326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; He, Y.; Chen, T.; Chan, K.-F.; Zhao, Y. Modified penicillin molecule with carbapenem-like stereochemistry specifically inhibits class C β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Ke, X.; Tian, X.; Chu, J. Cephalosporin C biosynthesis and fermentation in Acremonium chrysogenum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 6413–6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollnick, C.; Seidel, G.; Beyer, M.; Schügerl, K. Investigations of the production of cephalosporin C by Acremonium chrysogenum. In New Trends and Developments in Biochemical Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, A.; Davey, P.; Geddes, A.; Farrell, I.; Brookes, G. Clavulanic acid and amoxycillin: A clinical, bacteriological, and pharmacological study. Lancet 1980, 315, 620–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoae-Hagh, P.; Razavi, B.M.; Sadeghnia, H.R.; Mehri, S.; Karimi, G.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Molecular and Behavioral Neuroprotective Effects of Clavulanic Acid and Crocin in Haloperidol-Induced Tardive Dyskinesia in Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 5156–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ríos, D.; Gómez-Gaona, L.M.; Ramírez-Malule, H. Clavulanic Acid Overproduction: A Review of Environmental Conditions, Metabolic Fluxes, and Strain Engineering in Streptomyces clavuligerus. Fermentation 2024, 10, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcazar-Ochoa, L.G.; Ventura-Martínez, R.; Ángeles-López, G.E.; Gómez-Acevedo, C.; Carrasco, O.F.; Sampieri-Cabrera, R.; Chavarría, A.; González-Hernández, A. Clavulanic acid and its potential therapeutic effects on the central nervous system. Arch. Med. Res. 2024, 55, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J.D.; Patel, S.; Regan, M.R.; Haenggeli, C.; Huang, Y.H.; Bergles, D.E.; Jin, L.; Dykes Hoberg, M.; Vidensky, S.; Chung, D.S. β-Lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature 2005, 433, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, L.J.; Yan, F.; Liu, P.; Liu, H.-w.; Drennan, C.L. Structural insight into antibiotic fosfomycin biosynthesis by a mononuclear iron enzyme. Nature 2005, 437, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergogne-Bérézin, E. Fosfomycin and derivatives. In Antimicrobial Agents: Antibacterials and Antifungals; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 972–982. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, L.L. Fosfomycin: Mechanism and resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a025262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altwiley, D.; Brignoli, T.; Edwards, A.; Recker, M.; Lee, J.C.; Massey, R.C. A functional menadione biosynthesis pathway is required for capsule production by Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 2021, 167, 001108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, M.J. The biosynthesis of menaquinone-4: How a historic biochemical pathway is changing our understanding of vitamin K nutrition. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beulens, J.W.; Booth, S.L.; van den Heuvel, E.G.; Stoecklin, E.; Baka, A.; Vermeer, C. The role of menaquinones (vitamin K2) in human health. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conly, J.; Stein, K. The production of menaquinones (vitamin K2) by intestinal bacteria and their role in maintaining coagulation homeostasis. Prog. Food Nutr. Sci. 1992, 16, 307–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marchionatti, A.M.; Picotto, G.; Narvaez, C.J.; Welsh, J.; de Talamoni, N.G.T. Antiproliferative action of menadione and 1, 25 (OH) 2D3 on breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 113, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehringer, M.; Laufer, S.A. Emerging and re-emerging warheads for targeted covalent inhibitors: Applications in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 62, 5673–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakheit, A.H.; Saquib, Q.; Ahmed, S.; Ansari, S.M.; Al-Salem, A.M.; Al-Khedhairy, A.A. Covalent inhibitors from saudi medicinal plants target RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2023, 15, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, E.; Zarei, A.; Omidkhoda, A. Parthenolide: Pioneering new frontiers in hematological malignancies. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1534686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrke, M.; Lazar, M.A. The many faces of PPARγ. Cell 2005, 123, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. Regulation of PPARγ function by TNF-α. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 374, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, D.; Altamirano-Vallejo, J.C.; Navarro-Partida, J.; Sanchez-Aguilar, O.E.; Inzunza, A.; Valdez-Garcia, J.E.; Gonzalez-de-la-Rosa, A.; Bustamante-Arias, A.; Armendariz-Borunda, J.; Santos, A. Enhancing Ocular Surface in Dry Eye Disease Patients: A Clinical Evaluation of a Topical Formulation Containing Sesquiterpene Lactone Helenalin. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizemore, N.; Lerner, N.; Dombrowski, N.; Sakurai, H.; Stark, G.R. Distinct roles of the IκB kinase α and β subunits in liberating nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) from IκB and in phosphorylating the p65 subunit of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 3863–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurram, I.; Khan, M.U.; Ibrahim, S.; Ghani, M.U.; Amin, I.; Falzone, L.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Setzer, W.N.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Calina, D. Thapsigargin and its prodrug derivatives: Exploring novel approaches for targeted cancer therapy through calcium signaling disruption. Med. Oncol. 2024, 42, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A.; Bagchi, D.; Kaliappan, K.P. Thapsigargin: A promising natural product with diverse medicinal potential-a review of synthetic approaches and total syntheses. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 8551–8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makunga, N.P.; Jäger, A.K.; van Staden, J. An improved system for the in vitro regeneration of Thapsia garganica via direct organogenesis–influence of auxins and cytokinins. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2005, 82, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello, M.M.B.; de Oliveira Neves, V.G.; Parente, J.M.; Pernomian, L.; de Oliveira, I.S.; Pedersoli, C.A.; Awata, W.M.C.; Tirapelli, C.R.; Arantes, E.C.; Tostes, R.d.C.A. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) proteolysis by matrix metalloproteinase-2 contributes to vascular dysfunction in early hypertension. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 983, 176981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Tian, W. The role of SERCA in vascular diseases, a potential therapeutic target. Cell Calcium 2025, 129, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.B.; López, C.Q.; Manczak, T.; Martinez, K.; Simonsen, H.T. Thapsigargin—From Thapsia L. to mipsagargin. Molecules 2015, 20, 6113–6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, J.T.; Brennen, W.N.; Christensen, S.B.; Denmeade, S.R. Mipsagargin: The beginning—Not the end—Of thapsigargin prodrug-based cancer therapeutics. Molecules 2021, 26, 7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccioni, D.; Juarez, T.; Brown, B.; Rose, L.; Allgood, V.; Kesari, S. Atct-18: Phase II Study of Mipsagargin (G-202), A Psma-Activated Prodrug Targeting the Tumor Endothelium, in Adult Patients with Recurrent or Progressive Glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. 2015, 17 (Suppl. S5), v5. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.-J.; Xu, X.-K.; Shen, Y.-H.; Su, J.; Tian, J.-M.; Liang, S.; Li, H.-L.; Liu, R.-H.; Zhang, W.-D. Ainsliadimer A, a new sesquiterpene lactone dimer with an unusual carbon skeleton from Ainsliaea macrocephala. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2397–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teresa, L.D.P.; Caballero, E.; Anaya, J.; Caballero, C.; Gonzalez, M. Eudesmanolides from Chamaemelum fuscatum. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, X.; Luo, Z.; Wu, D.; Shi, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, C.; Yang, C. Chemical constituents from the flowers of Inula japonica and their anti-inflammatory activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 117052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoja, S.O.; Nnadi, C.O.; Udem, S.C.; Anaga, A.O. Potential antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of a heliangolide sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Helianthus annuus L. leaves. Acta Pharm. 2020, 70, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jian, S.; Nan, P.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Y. Chemotypical variability of leaf oils in Elephantopus scaber from 12 locations in China. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2005, 41, 491–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.A. Covalent inhibitors in drug discovery: From accidental discoveries to avoided liabilities and designed therapies. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Covalent Enzyme Inhibition | Non-Covalent Enzyme Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of interaction | Forms a stable chemical (covalent) bond with the target enzyme. | Involves reversible physical interactions such as hydrogen bonds, ionic forces, van der Waals interactions, and hydrophobic effects. |

| Reversibility | Generally irreversible or slowly reversible, depending on the bond stability. | Reversible, allowing the inhibitor to dissociate under physiological conditions. |

| Target engagement | Provides prolonged and sustained inhibition due to covalent linkage. | Results in transient and dynamic inhibition due to weaker, reversible binding. |

| Selectivity | Can achieve high selectivity by targeting rare amino acid residues (e.g., cysteine, serine). | Selectivity depends on binding affinity and complementarity of the enzyme–inhibitor interface. |

| Toxicity and Safety | May cause irreversible drug-induced toxicity or off-target covalent binding. | Generally exhibits a better safety profile due to reversibility. |

| Pharmacodynamics | Often leads to longer duration of action and reduced dosing frequency. | Allows more tunable pharmacodynamics and reversible modulation of enzyme activity. |

| Therapeutic Applications | Used in antiviral, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory drug design. | Used in kinase inhibitors, enzyme regulators, and protease inhibitors with reversible binding modes. |

| Advantages | High potency, durable target engagement, potential for overcoming drug resistance. | Reversible action, lower risk of permanent toxicity, greater control of dose–response. |

| Limitations | Risk of off-target reactivity, limited reversibility, possible mechanism-related toxicity. | Shorter duration of inhibition, may require higher or more frequent dosing. |

| Source | Representative Compound | Reactive Functional Group | Primary Molecular Target | Mechanism/ Type of Covalent Interaction | Biological/Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | 4-Isoavenaciolide | Exo-methylene (Michael acceptor) | VHR phosphatase (Cys124, Cys171) | Michael addition forming covalent adducts | Selective inhibition of dual-specificity and tyrosine phosphatases |

| Fungi | Hypothemycin (resorcylic acid lactone) | cis-Enone within macrocycle | ERK2 (Cys164) and kinases with CDXG motif | Covalent modification at conserved cysteine residues | Antiparasitic (Trypanosoma brucei), antitumor, kinase inhibitor |

| Fungi | Pyranonaphthoquinone lactones (e.g., 7-Deoxykalafungin) | Quinone and lactone moieties | Akt kinase (Cys310) | Thiol-mediated reduction forming reactive quinone methide intermediate | Potent and selective Akt inhibition (anticancer) |

| Fungi (Bipolaris spp.) | Ophiobolin A | 1,4-Dicarbonyl group | Phosphatidylethanolamine (lipid target) | Paal–Knorr pyrrole formation with lysine/amine groups | Paraptosis-like cytotoxicity, membrane disruption in cancer cells |

| Marine red algae (Delisea pulchra) | Fimbrolides | Polybrominated butenolide (bromoolefin) | LuxS (Cys83), LuxE (Cys362), and other quorum-sensing enzymes | Addition–elimination mechanism forming stable covalent adducts | Inhibition of quorum sensing and bacterial communication |

| Bacteria (Streptomyces spp.) | β-Lactam antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, carbapenems) | β-Lactam ring | Penicillin-binding proteins (serine transpeptidases) | Acylation of catalytic serine residue, irreversible inhibition | Bactericidal; inhibition of cell wall synthesis |

| Bacteria (Streptomyces clavuligerus) | Clavulanic acid | β-Lactam | Serine β-lactamases | Suicide inhibition via irreversible covalent binding | β-Lactamase inhibitor enhancing antibiotic efficacy; neuroprotective potential |

| Bacteria (Streptomyces fradiae) | Fosfomycin | Epoxide ring | MurA enzyme (Cys115) | Nucleophilic attack on epoxide; irreversible inactivation | Inhibition of peptidoglycan biosynthesis; broad-spectrum antibiotic |

| Bacteria (modified by gut microbiota) | Menadione (Vitamin K3) | Quinone moiety | CDC25A phosphatase (active-site cysteine) | Covalent modification of catalytic cysteine | Antiproliferative; potential anticancer activity |

| Source | Representative Compound | Reactive Functional Group | Primary Molecular Target | Mechanism/Type of Covalent Interaction | Biological/Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cruciferous vegetables | Allyl isothiocyanate, Sulforaphane, Phenethyl isothiocyanate | Isothiocyanate (-N=C=S) | Cysteine and lysine residues; TRPA1 ion channel | Covalent modification; reversible glutathione conjugation | Cancer chemoprevention; neurological disorders (schizophrenia, autism) |

| Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) | Parthenolide | α-exo-methylene-γ-butyrolactone, epoxide | IKKβ (CYS179), NF-κB signaling | Covalent modification of cysteine | Anti-inflammatory; acute myelogenous leukemia; drug-resistant glioblastoma |

| Elephantopus scaber | Deoxyelephantopin | Germacranolide | PPARγ (CYS176); proteasome | Covalent binding in zinc-finger domain | Anticancer (breast tumors); apoptosis induction |

| Arnica, Helenium species | Helenalin | α-exo-methylene-γ-butyrolactone, cyclopentenone | NF-κB p65 subunit (CYS38, CYS120) | Covalent cysteine modification | Anti-inflammatory; inhibition of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription |

| Thapsia garganica | Thapsigargin | Electrophilic angelate side chain | SERCA (calcium ATPases) | Irreversible covalent inhibition | Apoptosis induction; tool for cancer research; PSMA-targeted prodrug mipsagargin |

| Ainsliaea species | Ainsliadimer A | α-exo-methylene | IKKα/β (CYS46), PPARγ | Covalent modification at allosteric site | NF-κB inhibition; selective kinase and nuclear receptor targeting |

| Inula japonica | IJ-5 (Eudesmanolide) | α-exo-methylene | UbcH5c (CYS85), NF-κB pathway | Covalent modification of active site cysteine | Anti-inflammatory; selective inhibition of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme |

| Elephantopus mollis | EM23 (Heliangolide) | α-exo-methylene | Thioredoxin reductase (CYS497, Sec498) | Covalent modification of selenocysteine | Anticancer; redox-mediated apoptosis; suppression of NF-κB signaling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roviello, G.N. Nature-Inspired Pathogen and Cancer Protein Covalent Inhibitors: From Plants and Other Natural Sources to Drug Development. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111153

Roviello GN. Nature-Inspired Pathogen and Cancer Protein Covalent Inhibitors: From Plants and Other Natural Sources to Drug Development. Pathogens. 2025; 14(11):1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111153

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoviello, Giovanni N. 2025. "Nature-Inspired Pathogen and Cancer Protein Covalent Inhibitors: From Plants and Other Natural Sources to Drug Development" Pathogens 14, no. 11: 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111153

APA StyleRoviello, G. N. (2025). Nature-Inspired Pathogen and Cancer Protein Covalent Inhibitors: From Plants and Other Natural Sources to Drug Development. Pathogens, 14(11), 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111153