MDR Bacteremia in the Critically Ill During COVID-19: The MARTINI Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Patient Management

2.4. Pathogen Identification

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Logistic Regression Analysis

- Age (B = 0.071, p < 0.001; OR = 1.074; 95% CI: 1.042–1.107;): Each additional year of age was associated with an 7.4% increase in the odds of death, holding other variables constant.

- SOFA score (B = 0.393, p < 0.001; OR = 1.481; 95% CI: 1.190–1.843;): Each one-unit increase in SOFA was associated with a 48.1% increase in the odds of death.

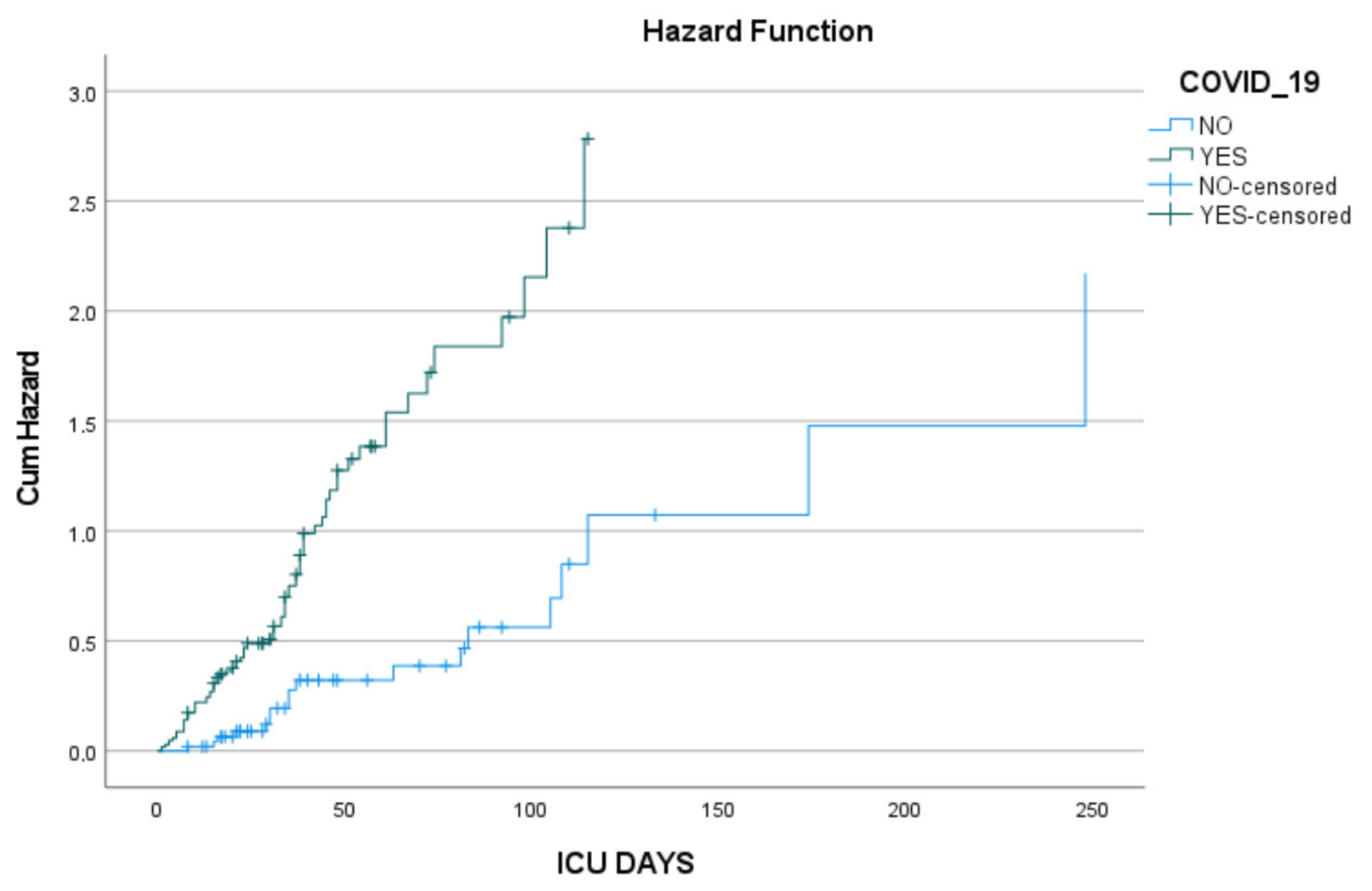

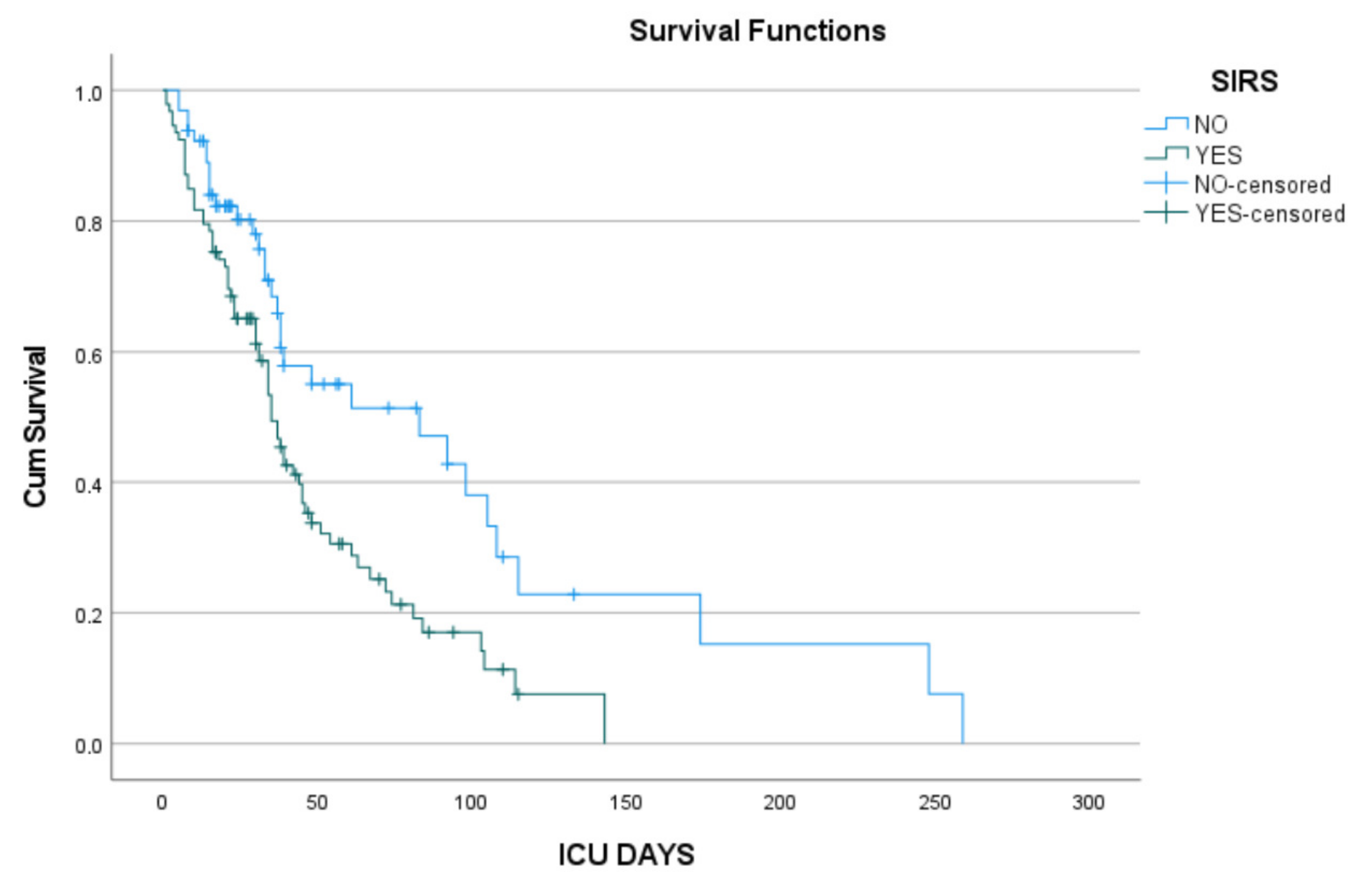

3.2. Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| APACHE II | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II |

| BLSI | Bloodstream Infection (used interchangeably with BSI) |

| BSI | Bloodstream Infection |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CLABSI | Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection |

| COVID-ICU | COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit |

| CRE | Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae |

| CRAB | Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CNS | Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CVC | Central Venous Catheter |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| ECDC | European Center for Disease Prevention and Control |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IV | Intravenous |

| MDR | Multidrug-Resistant |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MR-CNS | Methicillin-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PDR | Pandrug-Resistant |

| PLT | Platelets |

| PITT | Pitt Bacteremia Score |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SAPS II | Simplified Acute Physiology Score II |

| SIRS | Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| VRE | Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus |

| WBC | White Blood Cells |

| XDR | Extensively Drug-Resistant |

References

- Ranjbar, R.; Alam, M. Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Evid. Based Nurs. 2023, 27, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seneghini, M.; Rufenacht, S.; Babouee-Flury, B.; Flury, D.; Schlegel, M.; Kuster, S.P.; Kohler, P.P. It is complicated: Potential short- and long-term impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on antimicrobial resistance—An expert review. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J. How COVID-19 is accelerating the threat of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ 2020, 369, m1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getahun, H.; Smith, I.; Trivedi, K.; Paulin, S.; Balkhy, H.H. Tackling antimicrobial resistance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 442–442A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner-Lastinger, L.M.; Pattabiraman, V.; Konnor, R.Y.; Patel, P.R.; Wong, E.; Xu, S.Y.; Smith, B.; Edwards, J.R.; Dudeck, M.A. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on healthcare-associated infections in 2020: A summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D.R.; Battaglini, D.; Ball, L.; Brunetti, I.; Bruzzone, B.; Codda, G.; Crea, F.; De Maria, A.; Dentone, C.; Di Biagio, A.; et al. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 50, e13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasciana, T.; Antonelli, A.; Bianco, G.; Lombardo, D.; Codda, G.; Roscetto, E.; Perez, M.; Lipari, D.; Arrigo, I.; Galia, E.; et al. Multicenter study on the prevalence of colonization due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales strains before and during the first year of COVID-19, Italy 2018–2020. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1270924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polemis, M.; Mandilara, G.; Pappa, O.; Argyropoulou, A.; Perivolioti, E.; Koudoumnakis, N.; Pournaras, S.; Vasilakopoulou, A.; Vourli, S.; Katsifa, H.; et al. COVID-19 and Antimicrobial Resistance: Data from the Greek Electronic System for the Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance-WHONET-Greece (January 2018–March 2021). Life 2021, 11, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansbury, L.; Lim, B.; Baskaran, V.; Lim, W.S. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Westwood, D.; MacFadden, D.R.; Soucy, J.R.; Daneman, N. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: A living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buetti, N.; Tabah, A.; Loiodice, A.; Ruckly, S.; Aslan, A.T.; Montrucchio, G.; Cortegiani, A.; Saltoglu, N.; Kayaaslan, B.; Aksoy, F.; et al. Different epidemiology of bloodstream infections in COVID-19 compared to non-COVID-19 critically ill patients: A descriptive analysis of the Eurobact II study. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management of COVID-19: Living Guideline, June 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/b09467 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; McIntyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e1063–e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endeshaw, Y.; Campbell, K. Advanced age, comorbidity and the risk of mortality in COVID-19 infection. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2022, 114, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakthavatchalam, R.; Bakthavatchalam, S.; Ravikoti, S.; Shanmukham, B.; Reddy, K.S.; Pallavali, J.R.; Gaur, A.; Geetha, J.; Varatharajan, S. Analyzing the Outcomes of COVID-19 Infection on Patients With Comorbidities: Insights from Hospital-Based Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e55358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Marinkovic, A.; Patidar, R.; Younis, K.; Desai, P.; Hosein, Z.; Padda, I.; Mangat, J.; Altaf, M. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrascu, R.; Dumitru, C.S.; Laza, R.; Besliu, R.S.; Gug, M.; Zara, F.; Laitin, S.M.D. The Role of Age and Comorbidity Interactions in COVID-19 Mortality: Insights from Cardiac and Pulmonary Conditions. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwani, M.; Yassin, A.; Al-Zoubi, R.M.; Aboumarzouk, O.M.; Nettleship, J.; Kelly, D.; Al-Qudimat, A.R.; Shabsigh, R. Sex-based differences in severity and mortality in COVID-19. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Qie, G.; Yao, Q.; Sun, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Jiang, J.; Bai, X.; et al. Sex Differences on Clinical Characteristics, Severity, and Mortality in Adult Patients With COVID-19: A Multicentre Retrospective Study. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 607059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Olsson, P.E. Sex differences in severity and mortality from COVID-19: Are males more vulnerable? Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki Dana, P.; Sadoughi, F.; Hallajzadeh, J.; Asemi, Z.; Mansournia, M.A.; Yousefi, B.; Momen-Heravi, M. An Insight into the Sex Differences in COVID-19 Patients: What are the Possible Causes? Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2020, 35, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamo, D.; Aklog, E.; Gebremedhin, Y. Patterns of admission and outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit of Addis Ababa Burn Emergency and Trauma Hospital. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelms, S.B.; Wilhelms, D.B. Emergency department admissions to the intensive care unit—A national retrospective study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2021, 21, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfong, E.M.; Lovly, C.M.; Gillaspie, E.A.; Huang, L.C.; Shyr, Y.; Casey, J.D.; Rini, B.I.; Semler, M.W. Severity of illness scores at presentation predict ICU admission and mortality in COVID-19. J. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyambu, S.; Alsaei, A.; Mateen, P.; Javed, M.A.; Coriasso, C.; Khan, A.; Sadaka, F.J.C.C.M. 190: Predicting Mortality in COVID-19: Comparison of Novel Score with APACHE IV. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 49, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, M.A.; Elgazzar, A.G.; Abdalazeem, E.S.; Mousa, H.H.; Zahra, A.M. Validity of Severity scoring systems in critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection. Benha J. Appl. Sci. 2022, 7, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Taccone, F.; Schmit, X. Classification, incidence, and outcomes of sepsis and multiple organ failure. Contrib. Nephrol. 2007, 156, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L. Organ failure in the intensive care unit. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 32, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, T.; Hassani, F.; Ghaffari, N.; Ebrahimi, B.; Yarahmadi, A.; Hassanzadeh, G. COVID-19 and multiorgan failure: A narrative review on potential mechanisms. J. Mol. Histol. 2020, 51, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maab, H.; Mustafa, F.; Shabbir, S.J. Cardiovascular impact of COVID-19: An array of presentations. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.A.; Metaxaki, M.; Sithole, N.; Landin, P.; Martin, P.; Salinas-Botran, A. Cardiovascular disease and covid-19: A systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.W.; Gantner, D.; McGloughlin, S.; Leong, T.; Worth, L.J.; Klintworth, G.; Scheinkestel, C.; Pilcher, D.; Cheng, A.C.; Udy, A.A. The influence of intensive care unit-acquired central line-associated bloodstream infection on in-hospital mortality: A single-center risk-adjusted analysis. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, D.; Hansen, E.; Kreil, S.; Nolte, F.; Jawhar, M.; Hecht, A.; Hofmann, W.K.; Klein, S.A. The insertion site is the main risk factor for central venous catheter-related complications in patients with hematologic malignancies. Am. J. Hematol. 2022, 97, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowardman, J.R.; Robertson, I.K.; Parkes, S.; Rickard, C.M. Influence of insertion site on central venous catheter colonization and bloodstream infection rates. Intensive Care Med. 2008, 34, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, P.A. Hypotension and mortality in septic shock: The “golden hour”. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 1819–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitsioti, E.; Louka, C.; Mamali, V.; Kousouli, E.; Velentza, L.; Papadouli, V.; Loizos, G.; Mavroudis, P.; Kranidiotis, G.; Rekleiti, N.; et al. Bloodstream Infections in a COVID-19 Non-ICU Department: Microbial Epidemiology, Resistance Profiles and Comparative Analysis of Risk Factors and Patients’ Outcome. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kaur, A.; Chowdhary, A. Fungal pathogens and COVID-19. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 75, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga-Moya, J.C.; Papadopoulos, B.; Mansoor, A.E.; Mazi, P.B.; Rauseo, A.M.; Spec, A. Incidence and Mortality of COVID-19-Associated Invasive Fungal Infections Among Critically Ill Intubated Patients: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl, M.; Seidel, D.; Sprute, R.; Cunha, C.; Oliverio, M.; Goldman, G.H.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Carvalho, A. COVID-19-associated fungal infections. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trelles, M.; Murillo, J.; Fuenmayor-Gonzalez, L.; Yu-Liu, Y.; Alexander-Leon, H.; Acebo, J.; Cuicapuza, D.; Morales, M.; Pena, C.; Garcia-Aguilera, M.F. Prevalence of invasive fungal infection in critically Ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Luan, Z.; Ma, X. Risk of invasive candidiasis with prolonged duration of ICU stay: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntziora, F.; Giannitsioti, E. Bloodstream infections in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic: Changing epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in the intensive care unit. J. Intensive Med. 2024, 4, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kasiakou, S.K. Toxicity of polymyxins: A systematic review of the evidence from old and recent studies. Crit. Care 2006, 10, R27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, A.; Kreitmann, L.; Nseir, S. ICU-Acquired Colonization and Infection Related to Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in COVID-19 Patients: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serapide, F.; Quirino, A.; Scaglione, V.; Morrone, H.L.; Longhini, F.; Bruni, A.; Garofalo, E.; Matera, G.; Marascio, N.; Scarlata, G.G.M.; et al. Is the Pendulum of Antimicrobial Drug Resistance Swinging Back After COVID-19? Microorganisms 2022, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak-Qamsari, M.; Jenaghi, B.; Sahebi, L.; Norouzi-Shadehi, M.; Salehi, M.R.; Shakoori-Farahani, A.; Khoshnevis, H.; Abdollahi, A.; Feizabadi, M.M. Evaluation of Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus respiratory tract superinfections among patients with COVID-19 at a tertiary-care hospital in Tehran, Iran. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karruli, A.; Boccia, F.; Gagliardi, M.; Patauner, F.; Ursi, M.P.; Sommese, P.; De Rosa, R.; Murino, P.; Ruocco, G.; Corcione, A.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant Infections and Outcome of Critically Ill Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Single Center Experience. Microb. Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golli, A.L.; Popa, S.G.; Ghenea, A.E.; Turcu, F.L. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Antibiotic Resistance of Gram-Negative Pathogens Causing Bloodstream Infections in an Intensive Care Unit. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Meng, X. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on the distribution and drug resistance of pathogens in patients with bloodstream infection. Front. Public. Health 2025, 13, 1607801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Abideen, Z.U.; Azmat, A.; Irfan, M.; Anjum, S.; Dirie, A. Impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of multi-drug-resistant bacteria: A literature review and meta-analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2025, 118, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentieva, A.; Kaimakamis, E.; Voutsas, V.; Bitzani, M. An observational study on factors associated with ICU mortality in Covid-19 patients and critical review of the literature. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todi, S.; Ghosh, S. A Comparative Study on the Outcomes of Mechanically Ventilated COVID-19 vs Non-COVID-19 Patients with Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. Indian. J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bologheanu, R.; Maleczek, M.; Laxar, D.; Kimberger, O. Outcomes of non-COVID-19 critically ill patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective propensity score-matched analysis. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2021, 133, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leafloor, C.W.; Imsirovic, H.; Qureshi, D.; Milani, C.; Nyarko, K.; Dickson, S.E.; Thompson, L.; Tanuseputro, P.; Kyeremanteng, K. Characteristics and Outcomes of ICU Patients Without COVID-19 Infection-Pandemic Versus Nonpandemic Times: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Crit. Care Explor. 2023, 5, e0888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLarty, J.; Litton, E.; Beane, A.; Aryal, D.; Bailey, M.; Bendel, S.; Burghi, G.; Christensen, S.; Christiansen, C.F.; Dongelmans, D.A.; et al. Non-COVID-19 intensive care admissions during the pandemic: A multinational registry-based study. Thorax 2024, 79, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, A.B.; Admon, A.J.; Brenner, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Lazarous, D.; Leaf, D.E.; Gershengorn, H.B.; Investigators, S.-C. Association of Surge Conditions with Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19. J. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 37, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livieratos, A.; Gogos, C.; Akinosoglou, K. SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Clinical Outcomes of Special Populations: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Viruses 2024, 16, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| COVID ICU (n = 106) | Non-COVID ICU (n = 50) | Statistical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | |||

| Age (years) (median, IQR) | 64 (15) | 50 (33) | <0.0001 |

| Sex: male (n, %) | 73 (68.9) | 40 (80) | 0.146 |

| Cause of ICU admission | |||

| Infection n (%) | 105 (99.1) | 8 (16) | <0.001 |

| Trauma n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 10 (20) | <0.001 |

| Neurosurgical Pathology n (%) | 0 (0) | 16 (32) | <0.001 |

| Surgical Pathology n (%) | 0 (0) | 11 (22) | <0.001 |

| Other n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| CCI Score (median, IQR) | 2 (2) | 1 (4) | 0.016 |

| Diabetes Mellitus n (%) | 29 (27.36) | 7 (14) | 0.100 |

| Heart Failure n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2) | 0.540 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2) | 0.540 |

| Coronary Heart Disease n (%) | 5 (4.8) | 6 (12) | 0.177 |

| Dyslipidemia n (%) | 34 (32) | 9 (18) | 0.100 |

| Thyroid Dysfunction n (%) | 12 (11) | 1 (20) | 0.063 |

| Arterial Hypertension n (%) | 54 (51) | 10 (20) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease n (%) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (4) | 0.594 |

| Atrial Fibrillation n (%) | 6 (5.6) | 1 (2) | 0.431 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease n (%) | 12 (11) | 3 (6) | 0.390 |

| Dementia n (%) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Solid Organ Malignancy n (%) | 9 (8.5) | 9 (18) | 0.107 |

| Hematological Disease n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| Chronic Liver Disease n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| Obesity n (%) | 42 (50.6) | 16 (41) | 0.339 |

| Neuropsychiatric Disease/Drug Overuse n (%) | 8 (7.5) | 6 (12) | 0.379 |

| Autoimmune n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2) | 0.665 |

| Severity Indices | |||

| SOFA (median, IQR) | 8 (2) | 7 (4) | <0.001 |

| APACHE II (median, IQR) | 20 (4) | 19.50 (5) | 0.012 |

| Presence of SIRS n (%) | 67 (63.2) | 24 (48) | 0.083 |

| Laboratory Values | |||

| WBC K/μL (median, IQR) | 15,560 (9865) | 12,565 (10,508) | 0.170 |

| PLT K/μL (median, IQR) | 199,500 (194,000) | 177,000 (202,500) | 0.001 |

| Hb mg/dL (median, IQR) | 11.1 (4.1) | 9 (4.3) | 0.005 |

| CRP mg/dL (median, IQR) | 7.02 (13.2) | 2.83 (13.32) | 0.033 |

| Ferritin ng/mL (median, IQR) | 1306 (1750) | 992.5 (846) | 0.310 |

| Presence of Organ Failure upon ICU admission | |||

| Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (6.4) | 0.175 |

| Acute Renal Injury n (%) | 41 (39.4) | 11 (23.9) | 0.093 |

| Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation n (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (2.1) | 0.527 |

| Septic Shock n (%) | 29 (27.9) | 11 (22.9) | 0.559 |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome n (%) | 33 (31.7) | 5 (10.6) | 0.008 |

| COVID ICU (n = 106) | Non-COVID ICU (n = 50) | Statistical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PITT (median, IQR) | 8 (0) | 6 (2) | 0.001 |

| Days from ICU admission to (+) culture (median, IQR) | 7 (9) | 12 (18) | 0.060 |

| Days from hospital admission to (+) culture (median, IQR) | 15 (18) | 15.5 (17) | 0.524 |

| Days from (+) culture to initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy (median, IQR) | 0 (2) | 0 (3) | 0.129 |

| CVC position | 0.988 | ||

| Jugular n (%) | 95 (89.6) | 45 (90) | |

| Femoral n (%) | 7 (6.6) | 3 (6) | |

| Subclavian n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 2 (4) |

| COVID ICU (n = 106) | Non-COVID ICU (n = 50) | Statistical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen Identified | 0.441 | ||

| Gram (+) n (%) | 6 (5.7) | 4 (8) | |

| Gram (−) n (%) | 96 (90.6) | 42 (84) | |

| Fungi n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 4 (8) | |

| Monomicrobial n (%) | 106 (100) | 50 (100) | |

| Type of pathogen n (%) | 0.198 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 36 (34) | 19 (38) | |

| A. baumannii | 59 (55.7) | 23 (46) | |

| E. faecium | 6 (5.7) | 2 (4) | |

| Candida sp. | 4 (3.8) | 3 (6) | |

| Other | 1 (1.9) | 3 (6) | |

| Bacterial Resistance Mechanisms | 0.155 | ||

| CRAB n (%) | 59 (59) | 23 (52.3) | |

| CRE n (%) | 34 (34) | 20 (45.5) | |

| MR-CNS n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| VRE n (%) | 6 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Fungal resistance phenotype | 1.000 | ||

| Azole resistance n (%) | 3 (75) | 3 (75) | |

| Echinocandin resistance n (%) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | |

| Amphotericin B resistance n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| COVID ICU (n = 106) | Non-COVID ICU (n = 50) | Statistical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days from initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy to (−) culture (median, IQR) | 1 (14) | 2 (13) | 0.587 |

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 30 (30) | 34.5 (60) | 0.013 |

| Mortality (Death) n (%) | 79 (74.5) | 19 (38) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akinosoglou, K.; Petropoulou, C.; Karioti, V.; Kefala, S.; Bousis, D.; Stamouli, V.; Kolonitsiou, F.; Dimopoulos, G.; Gogos, C.; Fligou, F. MDR Bacteremia in the Critically Ill During COVID-19: The MARTINI Study. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111152

Akinosoglou K, Petropoulou C, Karioti V, Kefala S, Bousis D, Stamouli V, Kolonitsiou F, Dimopoulos G, Gogos C, Fligou F. MDR Bacteremia in the Critically Ill During COVID-19: The MARTINI Study. Pathogens. 2025; 14(11):1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111152

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkinosoglou, Karolina, Christina Petropoulou, Vasiliki Karioti, Sotiria Kefala, Dimitrios Bousis, Vasiliki Stamouli, Fevronia Kolonitsiou, George Dimopoulos, Charalambos Gogos, and Foteini Fligou. 2025. "MDR Bacteremia in the Critically Ill During COVID-19: The MARTINI Study" Pathogens 14, no. 11: 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111152

APA StyleAkinosoglou, K., Petropoulou, C., Karioti, V., Kefala, S., Bousis, D., Stamouli, V., Kolonitsiou, F., Dimopoulos, G., Gogos, C., & Fligou, F. (2025). MDR Bacteremia in the Critically Ill During COVID-19: The MARTINI Study. Pathogens, 14(11), 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14111152