Influence of Emotional Intelligence and Burnout Syndrome on Teachers Well-Being: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

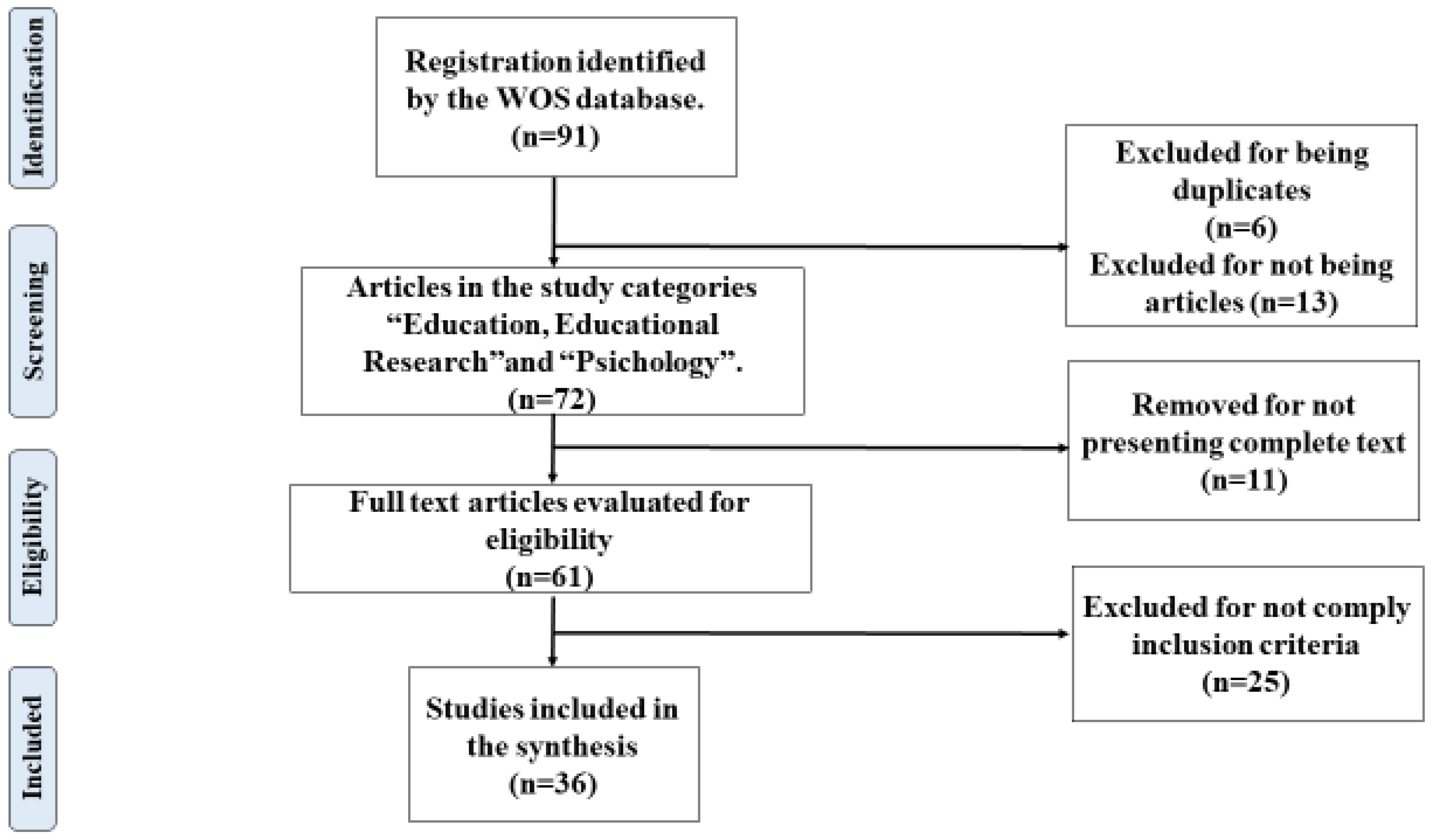

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.1.1. A Literature Search and the Identification of Relevant Studies

2.1.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

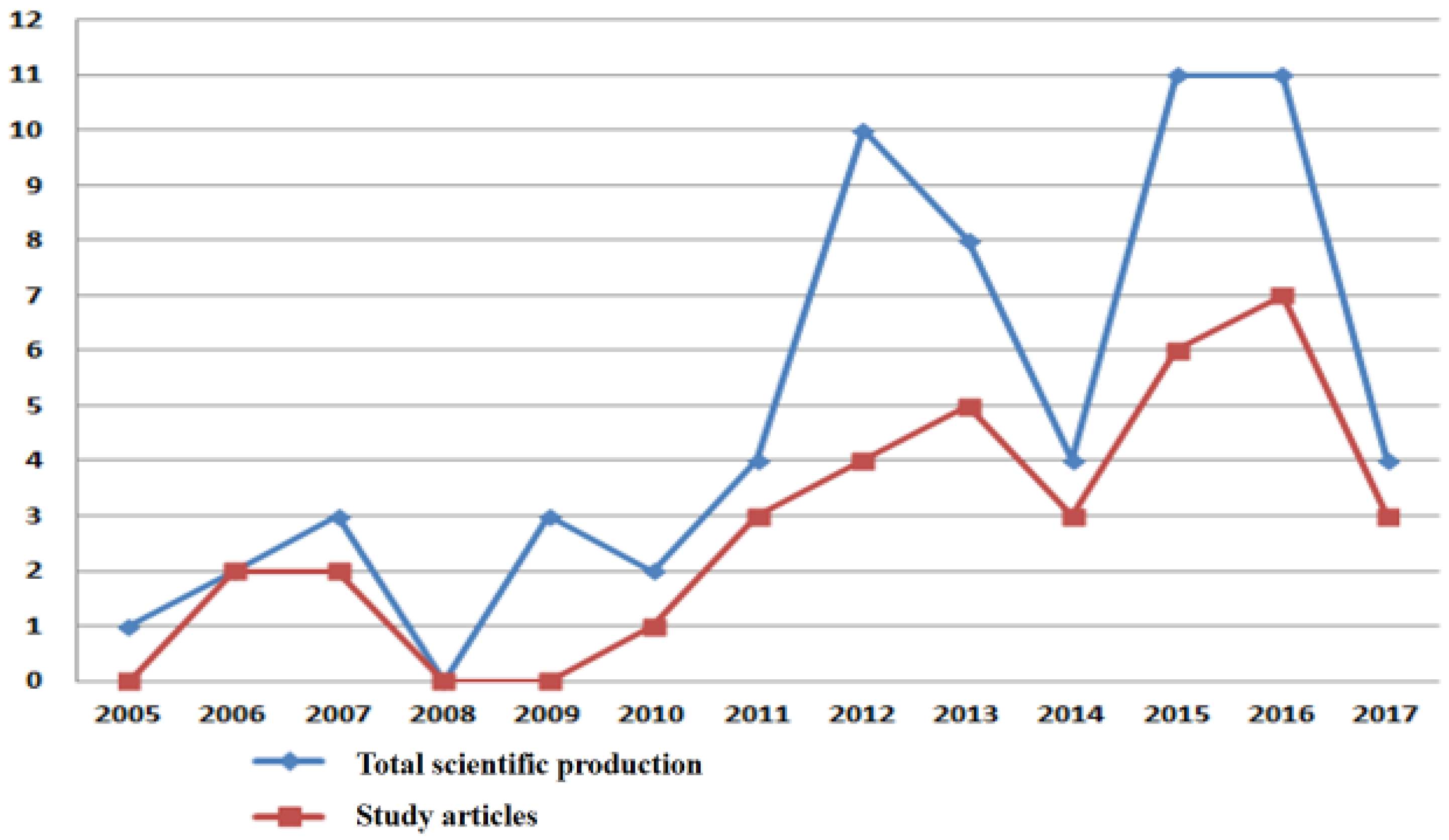

3.1. Evolution of Scientific Production

3.2. Data from Studies Selected for the Systematic Review

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adina-Colomeischi, Asdina. 2015. Teachers Burnout in Relation with Their Emotional Intelligence and Personality Traits. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 180: 1067–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, Hamid, Mansooreh Hosseinnia, and Javad G. Domsky. 2017. EFL teachers’ commitment to professional ethics and their emotional intelligence: A relationship study. Cogentent Education 4: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Landa, José M., Esther López-Zafra, Mª Pilar Berrios-Martos, and Manuel Pulido-Martos. 2012. Analyzing the relations among perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout. Psicología Conductual 20: 151–68. [Google Scholar]

- Baranovska, Andrea, and Dominika P. Doktorova. 2014. The need to create a cognitive structure for primary and secondary school teachers in relation to the degree of burnout and emotional intelligence. Psychology and Psychiatry 1: 491–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Reuven, and James Parker. 2000. Emotional and Social Intelligence: Insights from the Emotional Intelligence Inventory. In Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Persson. 2006. The relevance of personality traits and chronic stress due to a lack of fulfillment of needs for health disturbances of teachers. Psychologie Erziehung und Unterricht 53: 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, Marc A., Raquel Palomera, Justyna Mojsa-Kaja, María R. Reyes, and Peter Salovey. 2011. Emotion-regulation ability, burnout, and job satisfaction among British secondary-school teachers. Psychology in the Schools 47: 406–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Douglas H. 2007. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching, 5th ed. White Plains. New York: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-González, Rosario, Desirée Ruiz-Aranda, and Pablo Fernández-Berrocal. 2010. Docentes emocionalmente inteligentes. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 13: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Callegari, Camila, Ivano Caselli, Lorenza Bertù, Emanuela Berto, and Simone Vender. 2016a. Evaluation of the burden management in a psychiatric day center: distress and recovery style. Rivista di Psichiatria 51: 149–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, Camilla, Lorenza Bertù, Melissa Lucano, Marta Lelmini, Elena Braggio, and Vender Simone. 2016b. Realiability and validity of the Italian versión of the 14-item Resilience Scale. Psychology Research Behavior Management 9: 227–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardelle-Elawar, María, and Luisa S. Acedo-Lizarraga. 2011. Looking at teacher identity through self-regulation. Psicothema 22: 293–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, David W. 2006. Emotional intelligence and components of burnout among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Teaching and Teacher Education 22: 1042–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, David W. 2007. Burnout, self-efficacy, and successful intelligence among Chinese prospective and in-service school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology 27: 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Hyun J., and Kyung A. Park. 2007. The effect of emotional intelligence and self-efficacy on teachers’ burnout. The Journal of Korean Teacher Eduction 24: 251–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi, Joseph, Josehp P. Forgas, and John D. Mayer. 2006. Emotional Intelligence in Everyday Life. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doudin, Andrè, and Denise Curchod-Ruedi. 2011. La Comprensione Delle Emozioni Come Fattore di Protezione Dalla Violenza a Scuola. La Comprensione: Aspetti Cognitivi, Metacognitivi ed Emotive. Milano: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Elvira, Juan, and Javier Cabrera. 2004. Estrés y burnout en profesores. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 4: 597–621. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera, Natalio, Auxiliadora Durán, and Lourdes Rey. 2007. Inteligencia emocional y su relación con los niveles de burnout, engagement y estrés en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Educación 342: 239–56. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera-Pacheco, Natalio, Lourdes Rey-Peña, and Mario Pena-Garrido. 2016. Educadores de corazón. Inteligencia emocional como elemento clave en la labor docente. Journal of Parents and Teachers 368: 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feuerhahn, Nicolas, Christian Stamov-Roßnagel, Maren Wolfram, Silja Bellingrath, and Brigitte M. Kudielka. 2013. Emotional Exhaustion and Cognitive Performance in Apparently Healthy Teachers: A Longitudinal Multi-source Study. Stress and Health 29: 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorelli, Caterina, Ottavia Albanese, Piera Gabola, and Alessandro Pepe. 2016. Teachers’ Emotional Competence and Social Support: Assessing the Mediating Role of Teacher Burnout. Scandinavian Journal of Educucation Research 61: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Emma, and Dianne Vella-Brodrick. 2008. Social support and emotional intelligence as predictors of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 44: 1551–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Howard. 2011. De las Inteligencias Múltiples a la Educación Personalizada. Directed by Fred Zinnemann, and Emilio Gómez Muriel. Redes. México City: Carlos Chávez (for the Secretaría de Educación Pública). [Google Scholar]

- Ghanizadeh, Afsaneh, and Nahid Royaei. 2015. Emotional facet of language teaching: Emotion regulation and emotional labor strategies as predictors of teacher burnout. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning 10: 139–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goroshit, Marina, and Meriav Hen. 2016. Teachers’ empathy: Can it be predicted by self-efficacy? Teachers and Teaching 22: 805–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosotani, Rika, and Kyoko Imai-Matsumura. 2011. Emotional experience, expression, and regulation of high-quality Japanese elementary school teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education 27: 1039–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein-Heidari, Mohammad, Kamal Nosrati-Heshi, Zohre Mottagi, Mehrnosh Amini, and Ali Shiravani-Shiri. 2015. Teachers’ professional ethics from Avicenna’s perspective. Journal Educational Research and Reviews 10: 2460–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Sharon M., and Anthony V. Naidoo. 2017. A psychoeducational approach for prevention of burnout among teachers dealing with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS 29: 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowett, Gareth E., Andrew P. Hill, Howard K. Hall, and Thomas Curran. 2016. Perfectionism, burnout and engagement in youth sport: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 24: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Chengting, Jijun Lan, Yuan Li, Wei Feng, and Xuqun You. 2015. The mediating role of workplace social support on the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and teacher burnout. Teaching and Teacher Educational 51: 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakus, Mehmet. 2013. Emotional intelligence and negative feelings: A gender specific moderated mediation model. Educational Studies 39: 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hansung, and Sun Lee. 2013. The effects of childcare center teachers’ job satisfaction and burnout on young children’s emotional intelligence and social ability. Journal of Korean Council for Children and Rights 17: 369–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kotaman, Huseyin. 2016. Turkish early childhood teachers’ emotional problems in early years of their professional lives. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 24: 365–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yee H., and Packianathan Chelladurai. 2016. Affectivity, emotional labor, emotional exhaustion, and emotional intelligence in coaching. Journal of Appled Sport Psychology 28: 170–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Paulo N., Peter Salovey, Stéphane Côté, and Michael Beers. 2005. Emotion regulation abilities and the quality of social interaction. Emotion 5: 113–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaliyeva, Zabira, Aigerim Mynbayeva, Zukhra Sadvakassova, and Manzura Zholdassova. 2015. Correction of burnout in teachers. Procedia-Social Behavioral Sciences 171: 1345–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maslach, Christina. 2003. Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Sciences 12: 189–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Michael P. Leiter. 2001. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Leigh, Tashia Abry, Michelle Taylor, Manuela Jiménez, and Kristen Granger. 2017. Teachers’ mental health and perceptions of school climate across the transition from training to teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education 65: 230–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas Altman. 2009. Preferred reporting ítems for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals or Internal Medicine 151: 264–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Arrebola, Rubén, Asunción Martínez-Martínez, Félix Zurita-Ortega, Silvia San Román-Mata, Antonio J. Pérez-Cortés, and José L. Ubago-Jiménez. 2017. La actividad física como promotora de la Inteligencia Emocional en docentes. Revisión Bibliográfica. TRANCES 9: 387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Nizielski, S., S. Hallum, P. N. Lopes, and A. Schütz. 2012. Attention to student needs mediates the relationship between teacher emotional intelligence and student misconduct in the classroom. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 30: 320–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizielski, Sophia, Suhair Hallum, Astrid Schütz, and Paulo N. Lopes. 2013. A note on emotion appraisal and burnout: The mediating role of antecedent-focused coping strategies. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 18: 363–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, Verónica M., and Myron D. Friesen. 2016. Teachers as first responders in tragedy: The role of emotion in teacher adjustment eighteen months post-earthquake. Teaching and Teacher Education 59: 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomera-Martín, Raquel, Paloma Gil-Olarte, and Marc A. Brackett. 2006. ¿Se perciben con inteligencia emocional los docentes? Posibles consecuencias sobre la calidad educativa. Revista de Educación 341: 687–703. [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Garrido, Mario, and Natalio Extremera-Pacheco. 2012. Perceived emotional intelligence in primary school teachers and its relationship with levels of burnout and engagement. Revista de Educucación 359: 604–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, Nuria, Gemma Filella-Guiu, Anna Soldevila, and Anna Fondevila. 2013. Evalution of an emotional education program for primary teachers. Educación XX1 16: 233–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishghadam, Reza, and Samaneh Sahebjam. 2012. Personality and emotional intelligence in teacher burnout. The Spanis Journal of Psychology 15: 227–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platsidou, María. 2010. Trait emotional intelligence of Greek special education teachers in relation to burnout and job satisfaction. School Psychology International 31: 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloni, Nicola, Silvia M. Armani, Marta Ielmini, Ivano Caselli, Rosario Sutera, Roberto Pagani, and Camilla Callegari. 2017. Characteristics of the caregiver in mental health: stress and strain. Minerva Psichiatrica 58: 118–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloni, Nicola, Daniele Zizolfi, Marta Lelmini, Roberto Pagani, Ivano Caselli, Marcello Diurni, Anna Milano, and Camilla Callegari. 2018. A naturalistic study on the relationship among resilient factors, psychiatric symptoms, and psychosocial functioning in a sample of residential patients with psychosis. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 11: 123–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas-Molero, Pilar, Félix Zurita-Ortega, Ramón Chacón-Cuberos, Asunción Martínez-Martínez, Manuel Castro-Sánchez, and Gabriel González-Valero. 2018a. An explanatory model of emotional intelligence and its association with stress, burnout syndrome and non-verbal communication in the university techers. Journal Clinical Medicine 7: 524–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puertas-Molero, Pilar, José L. Ubago-Jiménez, Rubén Moreno-Arrebola, Rosario Padial-Ruz, Asunción Martínez-Martínez, and Gabriel González-Valero. 2018b. La inteligencia emocional en la formación y desempeño docente: Una revisión sistemática. REOP 29: 128–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Martos, Manuel, Esther López-Zafra, Fernándo Estévez-López, and José M. Augusto-Landa. 2016. The moderator role of perceived emotional intelligence in the relationship between sources of stress and mental health in teachers. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 19: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyhältö, Kirsi, Janne Pietarinen, and Katariina Salmela. 2011. Teacher–working-environment fit as a framework for burnout experienced by Finnish teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education 27: 1101–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, Lourdes, and Natalio Extremera. 2011. Social support as mediator of perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in a sample of teachers. Revista de Psicología Social 26: 401–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiiari, Abdulamir, Motahareh Moslehi, and Rohollah Valizadeh. 2011. Relationship between emotional intelligence and burnout syndrome in sport teachers of secondary schools. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 15: 1786–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salehnia, Nooshin, and Hamid Ashraf. 2015. On the Relationship between Iranian EFL Teachers’ Commitment to Professional Ethics and their Students’ Self-Esteem. MCSER 6: 135–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salovey, Peter, and John Mayer. 1990. Inteligencia Emocional. La Imaginación, la cognición y Personalidad. España: Vergara Editor. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey, Peter, Brian Bedell, Jerusha Detweiler, and Jhon Mayer. 1999. The Psychology of What Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Satybaldina, Nazym, Ajgul Saipova, Aaliya Karabayeva, Sveta Berdibayeva, and Anar Mukasheva. 2015. Psychodiagnostic of Emotional States of Secondary School Teachers with Long Work Experience. Procedia-Social. Behavioral Sciences 171: 433–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddighi, Sorour, Mohammad S. Bagheri, and Mortaza Yamini. 2016. Iranian EFL teacher burnout and its relation to human resources in workplace. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods 6: 429–60. [Google Scholar]

- Trigwell, Keith. 2012. Relations between teachers’ emotions in teaching and their approaches to teaching in higher education. Instructional Science 40: 607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, Guido, and Alessandro Pepe. 2014. Sense of coherence mediates the effect of trauma on the social and emotional functioning of Palestinian health providers. American. Journal Orthopsychiatric 84: 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, Ashley K., Donald H. Saklofske, and David W. Nordstokke. 2014. EI training and pre-service teacher wellbeing. Personality and Individual Differences 65: 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Hongbiao. 2015. The effect of teachers’ emotional labour on teaching satisfaction: Moderation of emotional intelligence. Teachers and Teaching Education 21: 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Hongbiao B., John C. Lee, and Zhong H. Zhang. 2013. Exploring the relationship among teachers’ emotional intelligence, emotional labor strategies and teaching satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education 35: 137–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita-Ortega, Félix, Manuel Rojas-Cabrera, Daniel Linares-Girela, Carlos J. López-Gutiérrez, Asunción Martínez-Martínez, and Manuel Castro-Sánchez. 2015. Satisfacción laboral en el profesor de educación física de Cienfuegos (Cuba). Revista de Ciencias Sociales 2: 261–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zysberg, Leehu, Chagay Orenshtein, Eli Gimmon, and Ruth Robinson. 2017. Emotional intelligence, personality, stress, and burnout among educators. International Journal of Stress Management 24: 122–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Country | Type of Research | Sample | Educational Stage (Media Experience) | Variable | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adina-Colomeischi (2015) | Romania | cross-sectional | 575 | PE/HS/U (15) | EI/BS | EIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Augusto-Landa et al. (2012) | Spain | cross-sectional | 251 | PE (39 ± 11.25) | EI/BS | TMMS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Baranovska and Doktorova (2014) | Slovakia | cross-sectional | 586 | PE/HS (30–52) | EI/BS | EE |

| MBI | ||||||

| Brackett et al. (2011) | USA | cross-sectional | 123 | HS (37.79 ± 10.99) | EI/BS | ERA |

| MSCEIT | ||||||

| MBI | ||||||

| Becker (2006) | Germany | cross-sectional | 91 | PE | EI/BS | EIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Chang (2006) | China | cross-sectional | 167 | HS (5.29 ± 4.77) | EI/BS | EIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Chang (2007) | China | cross-sectional | 267 | PE (4.67 ± 3.84) | EI/BS | SIQ |

| MBI | ||||||

| Cho and Park (2007) | China | cross-sectional | 254 | PE | EI/BS | EIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Fiorelli et al. (2016) | Italy | cross-sectional | 149 | PE | EI/BS | ECQ |

| MBI | ||||||

| Feuerhahn et al. (2013) | Germany | Longitudinal (6 month) | 100 | U (37.2 ± 9.1) | EI/BS | JP |

| EE | ||||||

| Ghanizadeh and Royaei (2015) | Iran | cross-sectional | 153 | HS (12.97 ± 11.4) | EI/BS | ERQ |

| MBI | ||||||

| Goroshit and Hen (2016) | Israel | cross-sectional | 543 | PE/HS/U (40.6 ± 11.1) | EI | ESE |

| Johnson and Naidoo (2017) | Africa | Longitudinal (6 sessions; 3 h) | 27 | PE (51) | BS | MBI |

| Ju et al. (2015) | China | cross-sectional | 307 | HS (42.01 ± 8.74) | EI/BS | WLEIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Karakus (2013) | Turkey | cross-sectional | 425 | PE | EI/BS | WLEIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Kim and Lee (2013) | China | cross-sectional | 152 | K (34.3 ± 33.3) | EI | EIS |

| Kotaman (2016) | Turkey | cross-sectional | 24 | K (1.5) | EI/BS | Interviews |

| Lee and Chelladurai (2016) | USA | cross-sectional | 430 | U (19.50 ± 3.96) | EI/BS | WLEIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Madaliyeva et al. (2015) | USA | Longitudinal | 240 | HS | EI/BS | IQ |

| FPI-B | ||||||

| Nizielski et al. (2012) | Germany | cross-sectional | 300 | HS (15.37 ± 7.94) | EI | WLEIS |

| Nizielski et al. (2013) | Germany | cross-sectional | 300 | PE (15.37 ± 7.94) | EI/BS | WLEIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| O’Toole and Friesen (2016) | New Zealand | cross-sectional | 20 | PE/HS/U (17.15 ± 10.05) | EI/BS | TSES |

| CBI | ||||||

| Pena-Garrido and Extremera-Pacheco (2012) | Spain | cross-sectional | 245 | PE | EI/BS | TMMS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Pérez-Escoda et al. (2013) | Spain | Longitudinal (30 h) | 92 | PE | EI | CDE-A |

| Pishghadam and Sahebjam (2012) | Iran | cross-sectional | 147 | PE (31.2 ± 9.2) | EI/BS | EQ-I |

| MBI | ||||||

| Platsidou (2010) | Greece | cross-sectional | 123 | PE (6.2) | EI/BS | EIS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Pulido-Martos et al. (2016) | Spain | cross-sectional | 250 | PE (39.0 ± 11.03) | EI/BS | TMMS |

| SSST | ||||||

| Rey and Extremera (2011) | Spain | cross-sectional | 123 | PE (39.86 ± 9.66) | EI | WLEIS |

| Saiiari et al. (2011) | Iran | cross-sectional | 183 | HS (25.5) | EI/BS | ECQ |

| MBI | ||||||

| Seddighi et al. (2016) | Iran | cross-sectional | 102 | PE/HS/U | BS | MBI |

| Satybaldina et al. (2015) | Iran | cross-sectional | 72 | HS | EI/BS | EMIN |

| MBI | ||||||

| Vesely et al. (2014) | USA | Longitudinal (5 weeks) | 49 | U (26.5 ± 6.19) | EI/BS | TMMS |

| MBI | ||||||

| Yin (2015) | China | cross-sectional | 1.281 | PE/HS | EI | WLEIS |

| Yin et al. (2013) | China | cross-sectional | 1.281 | HS | EI/BS | WLEIS |

| TSS | ||||||

| Zysberg et al. (2017) | Israel | cross-sectional | 300 | K (46.60 ± 10.61) | EI/BS | SREIT |

| BSI |

| Educational Stage | Study Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten | 3 | 8.4% |

| Primary Education | 14 | 38.9% |

| High School | 9 | 25% |

| Primary Education and High School | 2 | 5.5% |

| University | 3 | 8.4% |

| Primary Education, High School and University | 5 | 13.8% |

| Total | 36 | 100% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puertas Molero, P.; Zurita Ortega, F.; Ubago Jiménez, J.L.; González Valero, G. Influence of Emotional Intelligence and Burnout Syndrome on Teachers Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060185

Puertas Molero P, Zurita Ortega F, Ubago Jiménez JL, González Valero G. Influence of Emotional Intelligence and Burnout Syndrome on Teachers Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(6):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060185

Chicago/Turabian StylePuertas Molero, Pilar, Félix Zurita Ortega, José Luis Ubago Jiménez, and Gabriel González Valero. 2019. "Influence of Emotional Intelligence and Burnout Syndrome on Teachers Well-Being: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 8, no. 6: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060185

APA StylePuertas Molero, P., Zurita Ortega, F., Ubago Jiménez, J. L., & González Valero, G. (2019). Influence of Emotional Intelligence and Burnout Syndrome on Teachers Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences, 8(6), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060185