Parenting Practices and Adjustment Profiles among Latino Youth in Rural Areas of the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Adolescent Adjustment

1.2. Parenting and Adolescent Adjustment

1.3. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

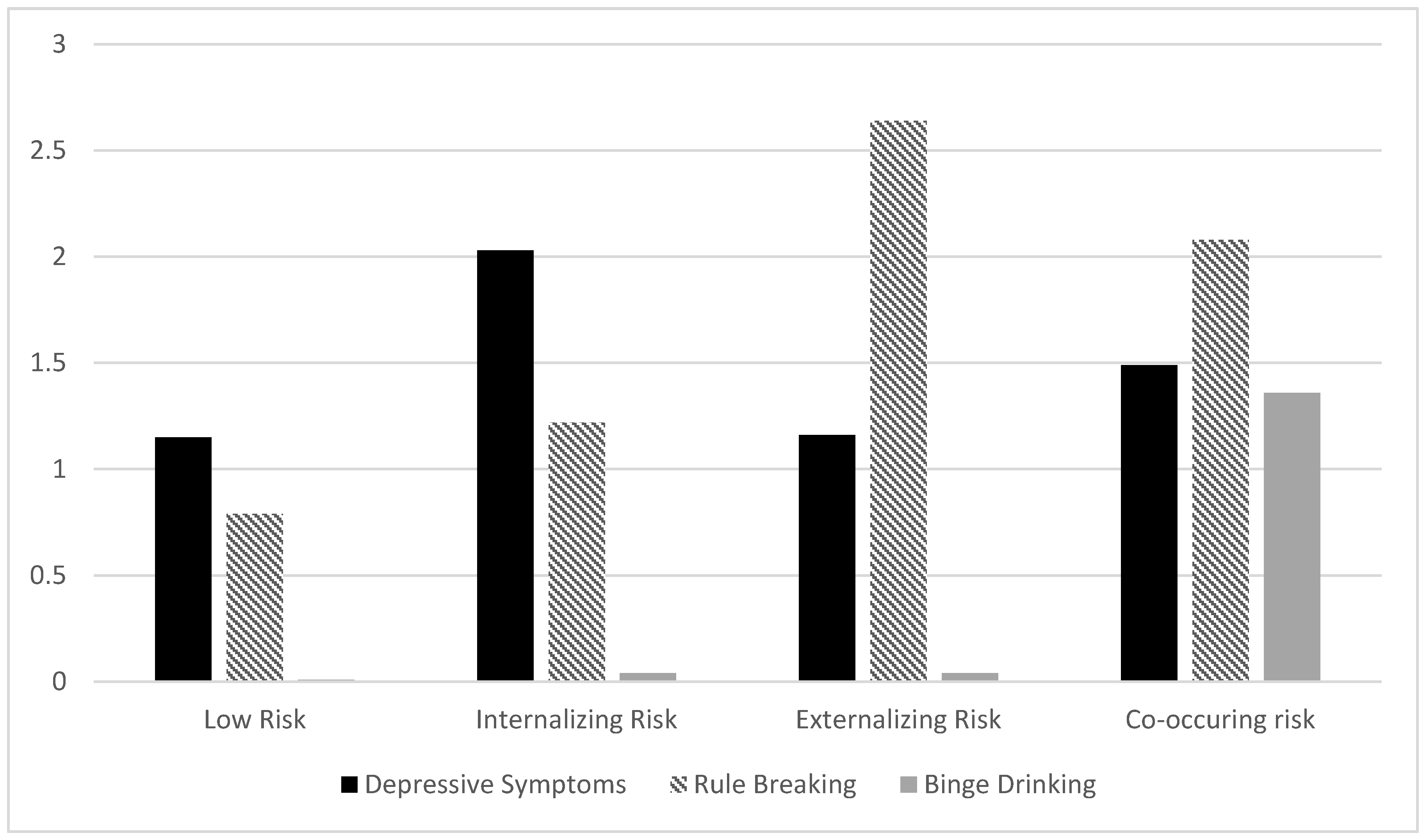

3.3. Adjustment Profiles

3.4. Parenting Practices and Adjustment Profiles

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bámaca-Colbert, Mayra Y., Melinda Gonzales-Backen, Carolyn S. Henry, Peter S. Y. Kim, Martha Zapata Roblyer, Scott W. Plunkett, and Tovah Sands. 2018. Family profiles of cohesion and parenting practices and Latino youth adjustment. Family Process 57: 719–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrendt, Silke, Gerhard Bühringer, Michael Höfler, Roselind Lieb, and Katja Beesdo-Baum. 2017. Prediction of incidence and stability of alcohol use disorders by latent internalizing psychopathology risk profiles in adolescence and young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 179: 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosworth, Kris, and Dorothy Espelage. 1995. Teen Conflict Survey. Bloomington: Center for Adolescent Studies, Indiana University. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, Miguel Ángel, Seth J. Schwartz, Linda G. Castillo, Andrea J. Romero, Shi Huang, Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco, Jennifer B. Unger, Byron L. Zamboanga, Sabrina E. Des Rosiers, Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, and et al. 2015. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence 42: 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlo, Gustavo, Rebecca M. B. White, Cara Streit, George P. Knight, and Katharine H. Zeiders. 2018. Longitudinal relations among parenting styles, prosocial behaviors, and academic outcomes in US Mexican adolescents. Child Development 89: 577–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caughy, Margaret O’Brien, Saundra Murray Nettles, and Julie Lima. 2011. Profiles of racial socialization among African American parents: Correlates, context, and outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies 20: 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012. Youth risk behavior surveillance. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 61: S162. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6104.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Chan, Ya-Fen, Michael L. Dennis, and Rodney R. Funk. 2008. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 34: 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. Angus, M. Brent Donnellan, Richard W. Robins, and Rand D. Conger. 2015. Early adolescent temperament, parental monitoring, and substance use in Mexican-origin adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 41: 121–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colder, Craig R., Seth Frndak, Liliana J. Lengua, Jennifer P. Read, Larry W. Hawk, and William F. Wieczorek. 2018. Internalizing and externalizing problem behavior: A test of latent variable interaction predicting a two-part growth model of adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 46: 319–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criss, Michael M., Tammy K. Lee, Amanda Sheffield Morris, Lixian Cui, Cara D. Bosler, Karina M. Shreffler, and Jennifer S. Silk. 2015. Link between monitoring behavior and adolescent adjustment: An analysis of direct and indirect effects. Journal of Child and Family Studies 24: 668–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, Meridith, Vangie Foshee, Susan Ennett, Daniela Sotres-Alvarez, H. Luz McNaughton Reyes, Robert Faris, and Kari North. 2018. Profiles of internalizing and externalizing symptoms associated with bullying victimization. Journal of Adolescence 65: 101–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, Caroline B. R., Katie L. Cotter, Roderick A. Rose, and Paul R. Smokowski. 2016. Substance use in rural adolescents: The impact of social capital, anti-social capital, and social capital deprivation. Journal of Addictive Diseases 35: 244–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanti, Kostas A., and Christopher C. Henrich. 2010. Trajectoris of pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems from age 2 to age 12: Findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Developmental Psychology 46: 1159–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, Myriam, Timothy Grigsby, Daniel W. Soto, Seth J. Schwartz, and Jennifer B. Unger. 2014. The role of bicultural stress and perceived context of reception in the expression of aggression and rule breaking behaviors among recent-immigrant Hispanic youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 30: 1807–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García Coll, Cynthia, Keith Crnic, Gontran Lamberty, Barbara Hanna Wasik, Renee Jenkins, Heidie Vazquez Garcia, and Harriet Pipes McAdoo. 1996. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development 67: 1891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Backen, Melinda A., Jamila E. Holcomb, and Lenore M. McWey. 2019. Cross-Ethnic Measurement Equivalence of the Children’s Depression Inventory Among Youth in Foster Care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, Momoko, Alison Giovanelli, Michelle M. Englund, and Arthur J. Reynolds. 2016. Not just academics: Paths of longitudinal effects from parent involvement to substance abuse in emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health 58: 433–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, Virginia W., and Andrew J. Fuligni. 2008. Ethnic socialization and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology 44: 1202–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, George P., Martha E. Bernal, Camille A. Garza, Marya K. Cota, and Katheryn A. Ocampo. 1993. Family socialization and the ethnic identity of Mexican-American children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 24: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, Maria. 1992. Children’s Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health System. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jingwen, Brian Mustanski, Danielle Dick, John Bolland, and Darlene A. Kertes. 2017. Risk and protective factors for comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems among economically disadvantaged African American youth. Development and Psychopathology 29: 1043–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Tamayo, Roberto, W. LaVome Robinson, Sharon F. Lambert, Leonard A. Jason, and Nicholas S. Ialongo. 2016. Parental monitoring, association with externalized behavior, and academic outcomes in urban African-American youth: A moderated mediation analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology 57: 366–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukas, Alexandra, and Hazel M. Prelow. 2004. Externalizing and internalizing problems in low-income Latino early adolescents: Risk, resource, and protective factors. Journal of Early Adolescence 24: 250–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubke, Gitta, and Michael C. Neale. 2006. Distinguishing between latent classes and continuous factors: Resolution by maximum likelihood? Multivariate Behavioral Research 41: 449–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manczak, Erika M., Sarah J. Ordaz, Manpreet K. Singh, Meghan S. Goyer, and Ian H. Gotlib. 2019. Time spent with parents predicts change in depressive symptoms in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masarik, April S., and Rand D. Conger. 2017. Stress and child development: A review of the family stress model. Current Opinion in Psychology 13: 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meque, Ivete, Berihun Assefa Dachew, Joemer C. Maravilla, Caroline Salom, and Rosa Alati. 2019. Externalizing and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence and the risk of alcohol use disorders in young adulthood: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miech, Richard A., Lloyd D. Johnston, Patrick M. O’Malley, Jerald G. Bachman, John E. Schulenberg, and Megan E. Patrick. 2019. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2018: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Milette-Winfree, Matthew, and Charles W. Mueller. 2018. Treatment-as-usual therapy targets for comorbid youth disproportionately focus on externalizing problems. Psychological Services 15: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, Krystal H., Olivia E. Atherton, Alina Quintana, Rand D. Conger, and Richard W. Robins. 2016. Reciprocal relations between internalizing symptoms and frequency of alcohol use: Findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 30: 203–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereyra, Sergio B., and Roy A. Bean. 2017. Latino adolescent substance use: A mediating model of inter-parental conflict, deviant peer associations, and parenting. Children and Youth Services Review 76: 154–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, Martin. 2017a. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology 53: 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, Martin. 2017b. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Marriage & Family Review 53: 613–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, Marcela, and Angela R. Wiley. 2012. Challenges and strengths of immigrant Latino families in the rural Midwest. Journal of Family Issues 34: 347–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Jamila E., Melinda A. Gonzales-Backen, Kimberly A. Allen, Eric A. Hurley, Roxanne A. Donovan, Seth J. Schwartz, Monika Hudson, Bede Agocha, and Michelle Williams. 2017. Ethnic–racial identity of Black emerging adults: The role of parenting and ethnic–racial socialization. Journal of Family Issues 38: 2200–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, Thomas J., Rand D. Conger, and Richard W. Robins. 2015. Early adolescent substance use in Mexican origin families: Peer selection, peer influence, and parental monitoring. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 157: 129–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, Laurence, Anne Fletcher, and Nancy Darling. 1994. Parental monitoring and peer influences on adolescent substance use. Pediatrics 93: 1060–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trucco, Elisa M., Brian M. Hicks, Sandra Villafuerte, Joel T. Nigg, Margit Burmeister, and Robert A. Zucker. 2016. Temperament and externalizing behavior as mediators of genetic risk on adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 125: 565–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, Adriana J., and Mark A. Fine. 2004. Examining ethnic identity among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 26: 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, Adriana J., Brendesha M. Tynes, Russell B. Toomey, David R. Williams, and Kimberly J. Mitchell. 2015. Latino adolescents’ perceived discrimination in online and offline settings: An examination of cultural risk and protective factors. Developmental Psychology 51: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijk-Herbrink, Marjolein F., David P. Bernstein, Nick J. Broers, Jeffrey Roelofs, Marleen M. Rijkeboer, and Arnoud Arntz. 2018. Internalizing and externalizing behaviors share a common predictor: The effects of early maladaptive schemas are mediated by coping responses and schema modes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 46: 907–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, Deyaun L., and Jackie A. Nelson. 2018. Parental monitoring and adolescent risk behaviors: The moderating role of adolescent internalizing symptoms and gender. Journal of Child and Family Studies 27: 3627–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Frances L., Nancy Eisenberg, Carlos Valiente, and Tracy L. Spinrad. 2016. Role of temperament in early adolescent pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems using a bifactor model: Moderation by parenting and gender. Development and Psychopathology 28: 1487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiders, Katharine H., Kimberly A. Updegraff, Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Susan M. McHale, and Jenny Padilla. 2016. Familism values, family time, and Mexican-Origin young adults’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Marriage and Family 78: 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Jing, and Natasha Slesnick. 2018. The effects of family systems intervention on co-occurring internalizing and externalizing behaviors of children with substance abusing mothers: A latent transition analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 44: 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parental behavioral involvement | -- | 2.99 | 0.90 | ||||

| 2. Parental Monitoring | 0.60 ** | -- | 2.06 | 0.98 | |||

| 3. FES a | 0.07 | −0.02 | -- | 3.23 | 1.13 | ||

| 4. Depressive Symptoms | 0.03 | 0.25 * | 0.06 | -- | 1.26 | 0.33 | |

| 5. Externalizing Behaviors | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.29 ** | 0.05 | -- | 1.45 | 1.04 |

| 6. Binge Drinking | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 0.28 ** | 0.21 * | 0.11 | 0.41 |

| Adjustment Profile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting Practice | Low Risk | Internalizing Risk | Externalizing Risk | Co-Occurring Risk |

| Parental behavioral involvement | 3.11 | 3.47 a | 2.89 | 2.43 a |

| Parental Monitoring | 2.15 b | 2.96 c | 1.88 d | 1.74 bcd |

| Familial Ethnic Socialization | 3.29 f | 3.98 e | 2.80 | 2.74 ef |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonzales-Backen, M. Parenting Practices and Adjustment Profiles among Latino Youth in Rural Areas of the United States. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060184

Gonzales-Backen M. Parenting Practices and Adjustment Profiles among Latino Youth in Rural Areas of the United States. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(6):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060184

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzales-Backen, Melinda. 2019. "Parenting Practices and Adjustment Profiles among Latino Youth in Rural Areas of the United States" Social Sciences 8, no. 6: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060184

APA StyleGonzales-Backen, M. (2019). Parenting Practices and Adjustment Profiles among Latino Youth in Rural Areas of the United States. Social Sciences, 8(6), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060184