Abstract

From the starting point of a 1975 artwork made by Norwegian artist Kjartan Slettemark in Sweden to stop a tennis match in resistance to the Chilean military dictatorship, this article reframes the linear image of networks of solidarity and resistance through the gaps and connectivity of a mesh. It expands the figure of the mesh taken from critical materialism into the affective realm of art, historiography, and art institutions by exploring the cases of the museums Museo de la Solidaridad (1971–1974) and Museo Internacional de la Resistencia “Salvador Allende” (1975–1990). As this article delves into various knots and lacunas of the meshes of solidarity and resistance partaking in these museums, and analyzing the relations they wove, it also aims to reflect on the capacity of resilience of arpilleras, as well as on the generative possibilities of the incomplete labor of art history and its ethical and political responsibilities.

1. Introduction

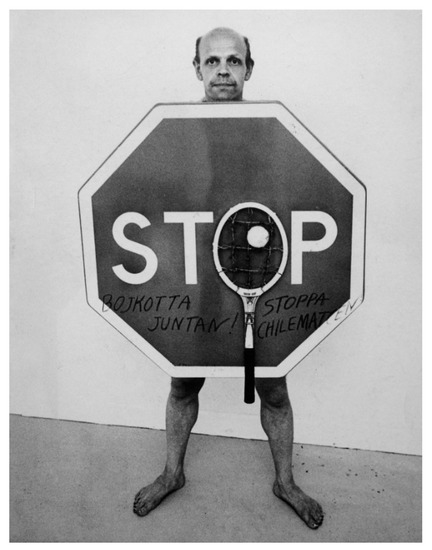

In 2007, I was caught in a mesh. Visually trapped by a hole in a net, caught in one of its interstices. I had visited the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA, Museum of Solidarity Salvador Allende) in Santiago, Chile, to see a show on graphic arts and politics. Among the works that alluded to social inequity, humans rights abuse, and multiple critiques to different forms of oppression, I found myself suddenly arrested by an artwork calling viewers to stop the pace of their normal museum perusing, its images and words strangely familiar yet utterly foreign: a silkscreen print made in 1975 in Sweden featuring a red “stop” sign (Figure 1). The “o” had been replaced by the oval of a tennis racquet and the latter’s mesh was supplanted by blue barb wire, a tennis ball caught within it. Across the paper’s surface, fragments of Swedish words like “Chile”, “junta”, “stop”, and “match”, are recognizable for the Spanish and English-speaking viewers. Considering that the work was made during the civic-military dictatorship in Chile and that it was exhibited at the MSSA, one might ask: What did tennis have to do with the Chilean military junta and with art?

Figure 1.

Kjartan Slettemark. Bojkotta juntan! Stoppa matchem. 1975. Silkscreen. Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA) collection. Used by permission of MSSA.

While MSSA provided no information about the work apart from the artist’s name and the date in which it was made, this lack makes us think about the work’s call as one that brings different times together: the year the work was made in 1975; the year it was exhibited at MSSA in 2007; today, 2019, and possibly beyond as it re-enacts the same gesture of calling out. The viewer thus is invited to think: Can we respond to a call from another time? Can we be affected by that call and its urgency if we no longer share its context and if we don’t fully understand its language? The relationship between art, affects, politics, and time is here central. From the realm of performance and theatre, scholar Rebecca Schneider wonders whether we can be moved by gestures from the past and if they can be interpreted as records to be accessed again. She asks, “if writing, read again, is still the trace of the author’s time, why would a feeling, accessed across time, or felt again, not also bear something of the historical trace? Is displacement necessarily falseness?” (Schneider 2014, p. 47). Looking at Paleolithic cave paintings, especially the images of hands that were painted as positive images on cave walls, for Schneider, these images are gestures in which humans interacted with each other thousands of years ago and in contexts whose histories we are unable to grasp. Yet, she contends that today, despite the conditions of the encounters being radically different, we meet these imprints just as they were encountered in the past as we are still in relation to a gesture. As Schneider writes: “The now of our encounter is certainly different from the then (we may not know what the handprints meant to ice age participants), but it is not only different. The body in relation is, despite radically shifting context, in relation again” (Schneider 2014, p. 67).

This same intersection between time, bodies, and affects can apply in 1975, 2007, and today, that is, throughout time to the silkscreen print described above in which the image of the net is central. This regards not just semiotics. This sign, this artwork, was enmeshed with networks of solidarity and resistance that had sprung up in the 1970s and continued throughout the 1980s, and opens up questions about the ways in which art embraces resistance, on the one hand, and on the ways in which the MSSA, a Museum that has had many names and lives and which was created from affective gestures of international solidarities, is, indeed, still calling out for that resistance, on the other hand. This article delves in these questions, which I will address by reframing the idea of networks, of a mesh, not from critical materialism but from the affective realm of art and historiography and its institutions. It explores some of the gaps in the networks conforming the MSSA, particularly though graphic signs and woven images of gesture and touch. In doing so, this article also reflects on the generative possibilities of the incomplete labor of art history and its ethical and political responsibilities.

2. Solidarity

The Museo de la Solidaridad (MS, Museum of Solidarity) was founded in 1971 in support of the Unidad Popular (UP, Popular Unity), the left-wing coalition supporting the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. It emerged from Operación Verdad (Operation Truth), a counter-information campaign of the UP that brought to Chile a group of international artists, scholars, and intellectuals in April 1971 to experience first-hand Allende’s revolution (Macchiavello 2012) and then spread abroad their personal affective narratives (Berríos 2017, pp. 88–89). During Operación Verdad’s formal and informal meetings, Spanish art critic José María Moreno Galván, Italian painter and activist Carlo Levi, and Spanish born painter José Balmes, a former refugee from Franco’s regime and a key figure in Chilean art, started thinking about a direct way in which the international art world could support the UP’s political project (Conselleria de Cultura País Valencia 1978). While art historical narratives have focused on the originator of the idea of a museum based on donations made by international artists in support of Allende’s government, the affective ground on which it germinated is important to note. If affect can be taken to be an emotional state of low-intensity that operates on a subconscious level, the feelings associated with emotions, and the capacity to affect and be affected (Bertelsen and Murphie 2010, p. 140), the affective ground can be thought of as a multidimensional environment involving a range of interacting agencies that can touch and move each other on conscious and unconscious levels. Art, for instance, had been given a special place within the informal activities of Operación Verdad, particularly crafts and muralism. Organized visits to the exhibitions Magia, hechicería y religión de América (Magic, witchcraft, and religion) at the Museo de Artes Populares (Museum of Popular Arts) and the muralist brigades Ramona Parra and Inti Peredo at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (Museum of Contemporary Art) set up an ambience of camaraderie among the participants against a lived backdrop of collective work and an institutional undoing of conventional artistic hierarchies. Moreno Galván and Levi were also invited to participate as speakers in a forum on the topic of “art and society” that was organized in conjunction with the opening of the muralist brigade’s exhibition, becoming directly engaged with the collective energies and urgent discussions taking place regarding the role of art in a socialist revolution. The memories of their own involvement in resistance movements against fascism in Spain and Italy, and the shared joy of being part of what was felt as a momentous change sprouting in Latin America, were intangible parts of the meshwork—the murky crisscrossing of open lines and trajectories and the emerging interstices between them (Ingold 2016, p. 11)—that helped bring about the idea of a Museum of Solidarity.

The MS was built within the polyphony of different languages and accents gathered in Operación Verdad that spoke about hope, collective efforts, and imagining new futures vis-à-vis other experiments in art, technology, and education that were carried on in Chile at the time. Though seemingly novel as an idea, it echoed the discourses of solidarity among Third World and non-aligned nations that had spread worldwide since the 1955 Bandung Conference. Defined from early on as a museum of modern and experimental art for the Chilean people, it would be based on gestures of solidarity “in the highest sense of the word (politics)—that is, in an eminently ethical, humanistic and libertarian sense,” as stated in its Necessary Declaration of November 1971. From the outset, the MS rejected art mercantilism and manifested a desire to break up with the colonial divide, aiming to “reach in profusion the underserved areas of the Third World” (quoted in Zaldívar 1991). Challenging linear avant-garde narratives and museological categories that separate movements and mediums, the MS would furthermore incorporate all styles, thus breaking with reductive divisions between formalism and political art, while acknowledging the cultural and artistic contradictions of this century as mentioned by the Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa in a letter to Edy de Wilde (Macchiavello 2012).

The MS materialized through an affirmative act of donation of the feelings of fellowship and mutual responsibility felt towards the emancipatory potential that Allende’s government seemed to herald. In this sense, the museum functioned as a gesture of solidarity itself; it was a performative sign enacting the coalescing powers of a community of feeling that willingly bypassed the capitalist transactions behind the creation of art collections. For some artists involved, this gesture amounted to an act of love and operated under the logic of surrender of the gift that was spurred by the personal commitment felt towards a specific political project. As a Cuban artist and contributor to the first collection, Lesbia Vent Dumois explained years later, to donate an artwork feels that you are giving up a part of yourself; an artwork is like an offspring.1 While we could read this as a heroic gesture of self-sacrifice imbued with sacral, religious, and ideological connotations, and even question its intentions (in so far as it may also have been for some an instrumental act leading to symbolic gain), Vent Dumois’s words point to a maternal, corporal, and psychic relationship with art that extends beyond political interest and is closer to love. Though we cannot assume that her gendered response was shared by all, her account of the act of donation for the MS weaves the care an artist might feel towards a creation and the invisible umbilical cord that needs to be cut for the artwork to be in the world for others, with the sense of individual loss that gives rise to a communitarian project. In this sense, solidarity can be understood as emerging from a cut, a loss, a sacrifice, as much as a desire to join and strengthen. It suggests that to create something new, something needs to be disrupted and transformed.

Today, discourses on solidarity tend to forget those loose threads and non-solid parts that pass through a mesh’s holes. They rather focus on the network’s stronger lines, bright knots, and heroic figures. Recent analyses of the MS have focused on the figure of Mário Pedrosa, then exiled in Chile and affiliated as a scholar to IAL (Institute of Latin American Art), who agreed to act as the Museum’s director. Pedrosa’s role expanding the Museum’s possible futures with his networks of international contacts and friendships has been increasingly highlighted as well as his vision for an experimental museum activated through artists’ workshops, and attention has also been placed on the role of the international committee of support, the Comité Internacional de Solidaridad Artística con Chile (CISAC, International Committee of Artistic Solidarity with Chile) as a rhizomatic web operating in a non-capitalist manner (Cofré Cubillos et al. 2019). The latter was formed to help disseminate the idea, spinning a larger web that included renowned art critics and cultural workers from the Americas and Europe: Louis Aragon, Dore Ashton, Edward (Edy) de Wilde, Jean Leymarie, Giulio Carlo Argan, and Moreno Galván, Rafael Alberti, Mariano Rodríguez, and Juliusz Starzysky, and later on, Sir Ronald Penrose and Harald Szeemann. While it is certainly necessary to understand the role and strategic connections made possible by these international links, the MS relied from the start on affective forms of labor that built tangible yet invisible filaments of this web. The Museum started small and local, with supporters from the Latin American Art Institute (IAL) and a team based at the Art Department of the University of Chile, though it quickly grew as those involved pitched in what they could: contacts, time, letter dictation and writing, telephone calls and meetings, cataloguing, transporting. While the presidential stamp of approval added political prestige and cultural urgency to the Museum, its importance relied mostly on the donated time and work of many, like Uruguayan filmmaker Danilo Trelles, art historian Miguel Rojas Mix who directed IAL and built a strong link with Cuba, the secretary of IAL María Eugenia Zamudio, gallerist Carmen Waugh, journalist Virginia Vidal, Brazilian art historian Daisy Peccinini and members of the Art Faculty, including Virginia Errázuriz and Balmes, among a long list of friends and partners.

Likewise, when thinking about solidarity, a homogeneous response to its call tends to be assumed: one either accepts the call or rejects it depending on one’s convictions or the project it is linked to. However, not every socially minded or left-inclined artist and intellectual wished to be a part of the project, as seen for instance in the refusal to participate of Philip Guston, Claes Oldenburg, and Willem de Kooning (Guston and de Kooning later on sent a work). Affect is variant, “transitive” (Bertelsen and Murphie 2010), involving multiple registers. The way each person involved in the MS was touched and moved by the concept of solidarity varied greatly and changed over time. Emotional depletion after years of activism had resulted in the gradual wavering of political commitment by U.S. artists as expressed by Ashton in her letters to Pedrosa. Difficulties might also be encountered in the case of artists who had been donating to other causes, like those solicited for Angela Davis’s liberation, as Peter Selz explained to him. A similar lack of enthusiasm from European artists (especially when compared to the rapid response of Latin Americans living in France) was noted by other committee members, linking their tepid response to the fear of becoming too intimately associated with a political idea or party and receiving art world retaliation. In spite of pre-existing solidarity networks, sending artworks to the “end” of the world was still a strange and risky idea that raised certain mistrust. Questions such as who would pay transportation, storage, and insurance refrained the impulse of some artists and delayed their donations. So were poignant concerns from CISAC members about the rushed way in which the Museum was being handled, with Pedrosa himself complaining about the lack of quality and representation of the Italian donations.

All this considered, one might wonder about the inner tensions and intentions of this burgeoning museum. For instance, by focusing on foreign donations, the MS did not allow local artists to participate, lacking a connection to its own soil in terms of the art it would collect. Such a critique resonated with discussions held at IAL regarding the ways in which “art” was defined and how it related to the people (“el pueblo”), as well as questions on who produces culture, and, ultimately, who makes these definitions.2 If the MS was a contingent political strategy resulting from a counter-propaganda campaign, then only foreign donations were needed to achieve the effect. But when the matter became how such a collection worked locally, how it related to the Chilean people, what discourses it subverted and reproduced, the question became more complex and its aims less clear. Elodie Lebou has argued that the Museum “revolutionized traditional museum practices” (Lebeau 2018, p. 331), as it became involved in social change. And yet, considering that it sprang in the revolutionary climate of the Popular Unity aiming to generate participation and dissolve epistemic hierarchies (García 2019), and that it resonated with the aims of a Socialist program that sought to create a new culture based on the masses, we might wonder: How could a museum that derived its prestige and political value from the works of foreign modern masters also be a non-hierarchical one serving the people of Chile? Could it move away from the reproduction of a history of the master/slave, center/periphery, and propose an alternate model of relation to art?

While the Museum of Solidarity collected over six hundred and fifty works by 1973, and exhibited its growing collection twice—first in May 1972 at MAC of Quinta Normal, and then in April 1973, in MAC and the UNCTAD III building—it was never legally constituted as a museum. It lacked a space of its own and Pedrosa was unable to invite participating artists to engage in workshops with local communities and fully explore the new museum’s possibilities. It was just a blueprint of the possible drawn in conversations, letters, proposals, plans. While efforts were made to renovate a space at Parque O’Higgins and legal actions were explored, they happened under strained circumstances, with knowledge that strikes, boycotts, internal divisions among the left, pressure from centrist and right-wing sectors, and the preparation of the military were leading towards armed confrontation. In spite of such difficulties, Pedrosa and his team kept their spirits high about the fate of the museum. As he mentioned in a letter to Dore Ashton of 6 November 1972, at times of struggle everything was interconnected, making art and politics inseparable. The coup on 11 September, however, cut short any possibilities of further development. Some works were still being exhibited at borrowed locations, causing the sudden closure of the exhibitions and supporting institutions. The Museum’s organizers were persecuted, some found asylum immediately while others were forced to exile. Some artworks were confiscated, others were left in other museum’s deposits, ending up in the offices of military officers, reappearing at times in exhibitions of other institutions without a proper recognition of their origin, or lost. Other works were tended to by caring hands, folded and stacked, waiting.

As this first part of the Museum’s history becomes increasingly studied, it is important to consider its gaps and lacunas, including: the idealization of a model that operated under the oppositional logics of the Cold War and a series of binaries; the pre-eminence given to donations of renowned artists from the north; the lack of interest in indigenous artists, the persistent class and racist barriers. More importantly, as it stands today, MSSA has an underside, a less-exposed network. Shunned from Chilean and global art history for a long time, it was considered to be tied to a history that needed to be erased, one that was even more politically instrumentalized than the solidarity period, disparaged and suppressed because of the sentiments it aroused. Slettemark’s work belongs to this constellation, that is, to the period at the MSSA known as “resistance”.

3. Stopping a Match: Meshes Within

The poster of the stop sign was made by Norwegian artist Kjartan Slettemark (1932–2008), who was living then in Sweden. Compelled to perform an act of resistance, Slettemark joined other Swedes, Chilean exiles, and foreigners in a massive boycott called by the Chile Committee (Chilekommitte), a political organization supporting Chilean resistance movements against the military dictatorship. The boycott aimed at stopping the Davis Cup tennis matches that were going to take place that year at the city of Båstad. The Chilean tennis team had passed to the semifinals, and the matches were to be played in Sweden against the Swedish team. Since Sweden prided itself on supporting Chilean exiles and being a democratic country that protected freedom of assembly, it could not cancel the matches and had to ensure the safety of tennis players, as well as impede any police violence against demonstrators. One of the players, Jaime Fillol, had allegedly received a death threat in a letter sent to a Swedish priest, in which a Chilean exile, whose wife had died at the hands of the military, claimed that Fillol’s support of the regime made him an accomplice (Macchiavello 2009). Though Fillol claimed he was representing a country and its people, and his trainer conveniently argued that they played tennis no matter who was Chile’s president, the matches provided an opportunity for activism and the potential of dire consequences (New York Times, 18 September 1975). As sport historian Brenda Elsey points out, solidarity activists were using all sorts of “sports events as opportunities to contest the legitimacy of Pinochet and call attention to the regime’s abuse of human rights” (Elsey 2013, p. 185). Simultaneously, the Swedish government was trying to avoid what was still a recent memory—the Båstad riots that broke out when Sweden faced Rhodesia for the Davis Cup. In 1968, protests against Rhodesia’s and South Africa’s apartheid policies had been so violent in their clash with the Swedish police that the matches had to be cancelled.

Police were mobilized in a theatrical display of power that was unparalleled in the tournament’s history: two fire helicopters would monitor the games, a ship would be stationed in the coast, and 1200 armed policemen with more than a 100 dogs, horses, and tear-gas pistols would be on foot. The city was turned into a fortress, the tennis complex surrounded by two protective walls with corresponding fences that shut down all neighborhood traffic. Tickets were not sold openly in the market, seats were double checked, and 40-foot-tall nets were set up around the clay court so that no projectiles could reach it. On 18 September 1975, a Stockholm daily newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, published aerial photographs of the closed precinct and maps of the protests’ locations. This “theatrical display” gained global attention. In the U.S., the New York Times commented that the picturesque and idyllic tourist city by the sea had been transformed into an “iron fortress” (19 and 20 September 1975). The press supporting the manifestations, on the other hand, emphasized the intimidating display of potential force in the democratic country, connecting the wall imagery with Cold War geopolitics and territorial divisions, and even alluding in some cartoons to the executions of political prisoners that had taken place in stadiums in Chile in 1973. But demonstrators were ingenious and playful. Since they were only allowed to occupy a plaza far away from the tennis court, they lit firecrackers, used bullhorns and sirens to create noise during the matches, and sent flying over the court inflated bright red balloons with the names of victims of the dictatorship, including renowned ones, like songwriter Victor Jara (who was tortured at the Chile Stadium in Santiago), and anti-junta slogans, hovering like a red menace.

Taking the protestor’s slogan as the basis of a personal act of repudiation of the military regime, Slettemark made a performance-assemblage object for which he appropriated a large street stop sign, attached in the place of the “O” a tennis racquet whose mesh had been replaced by barb wire. He then placed a yellow tennis ball in one of its holes and wrote the slogan “Boycott the Junta! Stop the match against Chile!”. He also carried the sign in the streets and was photographed standing nude and bald, holding the stop sign in front of his torso and redeploying it as a protective shield that called attention and guarded his exposed body (Figure 2).3 The gesture invoked both the vulnerability and power of nudity, the unguarded exposure of the concrete protesting body, doubly raising its call to stop transit, to be touched and come out from the private comfort of Swedish homes to the streets to collectively resist the Junta while redefining the signs of normativity and social control in public space. That particular body though was erased from the picture when the photograph became the basis for a poster printed with the support of the Chilean Committee in Stockholm, which was used to call people to join the protests and help boycott the matches. What remained was only the stop sign turned into a more abstract and thus seemingly universal sign. Slettemark’s stop sign appeared in multiple formats before the final; it was pasted on the streets of Stockholm, and could be glimpsed held by the protestors at Båstad; a few years later it was reproduced as the cover of Stokholm’s VI magazine in 1978, in a homage to Allende. Though they were not able to stop the semi-final’s last match (Chileans were defeated by the Swedes 4-1), 6500 protesters gathered to resist the dictatorship, with some beckoned by a sign in a silkscreen print that was still to be found in the streets of Stockholm a year later (image reproduced in Camacho Padilla 2009).

Figure 2.

Kjartan Slettemark. Bojkotta juntan! Stoppa matchem. 1975. Photograph by Jan Erik Jonasson. Used by permission of Karin Grönlund.

I invoke this image of arrest and calling, of protest and nets, because when we think about networks we tend to picture a system of interconnected things, people, places, an arrangement of points and lines in diverse configurations, and of exchanges among its nodes, circulating data, energies, information. While the elements conforming the nodes may vary and the network might grow, decrease, break, strengthen, and even collapse, we hardly stop to think about the elements caught in between the web, those apparently empty spaces where things can actually get trapped or flow in a different direction. After all, the origin of the word net and “red” are connected with fishing, the Latin rete or retis, the mesh used to fish. The net thus contains points of suspension, holes or negative spaces that let pass and allow other flows to happen, enabling different binds to occur, knots to be dissolved and new ones to be created. As Timothy Morton argues, “Meshes are potent metaphors for the strange interconnectedness of things, an interconnectedness that does not allow for perfect, lossless transmission of information, but is instead full of gaps and absences” (Morton 2013, p. 83). In this sense, meshes include both the relationships created by the crisscrossing threads and the gaps produced in between them. The gaps are constitutive of the mesh and allow for openings rather than fixity, for things to get caught and dropped, that pass by without being registered by the net, for loss. From this perspective, Slettemark’s poster offers a material opening to explore an ampler understanding of what a network may entail, especially networks of solidarity and resistance. Can the holes in the net trouble our assumptions about networks and how they operate? What passes through the gaps, what gets lost in the network, in translation, in and between the knots that bind people, artworks, feelings, politics, struggles? Would it be possible to think of networks in these strange areas of overlap that also create thresholds, even resistance to passage and flow, points of suspension and uncertainty, the potential of in-betweenness?

Slettemark’s “Stop” poster has been largely ignored by the art historical canon. This is not the case of his prior works made with bright clashing colors and graphically polemic images that called for sympathy with Ulrike Meinhof, or his collages Nixon Visions (1971–74), which granted the artist international recognition. Circulating widely and appropriated by protesters around the world, Nixon Visions, for instance, combined an image of a smiling Nixon holding a coffee cup with a fragment from an advertisement for the Swedish coffee brand Gevalia in a psychedelic and kaleidoscopic effect (Högkvist et al. 2013). Its composition resonated with the bold visual language of OSPAAAL posters (Organización de Solidaridad de África, Asia y América Latina, Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America) that helped disseminate and link protest movements internationally. By contrast, the Stoppa matchem poster’s fate was very similar to that of the Museum it was donated, the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia “Salvador Allende” MIRSA (Museum of Resistance Salvador Allende), whose collection was shown at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm between March and April 1978 and yet, its story remained stored for decades in the recollections of those who had contributed to it. When mentioned in Chilean art historical accounts, the MIRSA was treated pejoratively as a case of propaganda, of political instrumentalization, or as an addendum to its first phase, the Museo de la Solidaridad, and a chapter too complicated to deal with. In so doing, it was reduced to a sentimental political project conceived by nostalgic exiles rather than an artistic or cultural one, and thus dismissed, left on its own and to its promoters. An ideological symbol, a silent sign of a past age. And yet, it called.

A second question raised by the poster’s call concerns the work of art historians in the present. Recently, scholars from a variety of backgrounds have become interested in MSSA and the networks that have shaped its phases. How do we tie ourselves or get caught in these old meshes and bring them to the present? As social protests continue to sprout in Latin America and we see in Chile the use of street signs as shields during clashes with the police and military forces brought out to the streets, or we listen to the incessant music of pots and pans banged on the streets, and resonate with Victor Jara’s song reminding us of the right to live in peace, it is inevitable for me to recall Slettemark’s work and the Båstad protests, and the endurance and transformation of these resisting gestures. As art historians, how do we knot ourselves into the meshes and networks we are trying to (re)construct and in so doing, pay attention to our own localized and embodied experiences, prejudices, educational distortions, mannered trainings, colonial, logocentric, and patriarchal mentalities? How do we participate in that which we study, co-creating its image? If avoiding the pitfalls of projections is impossible as well as arriving at any final truth, how do we become accountable for the stories we choose to tell? How does our research, writing, curating, or narrating reflect our contradictions, our tensions and passions, acknowledging our ethical and political responsibilities? Do we leave any loose knots, zones of uncertainty within the linear tracings we so meticulously and lovingly draw? What do we resist?

4. Remembering Resistance

When Slettemark created his poster in 1975, the exiled members of the Museum of Solidarity had since regrouped and were devising strategies to continue the project. After the coup, the 73 year old Pedrosa had to hide in friends’ homes and seek asylum again, first in Mexico through Fernando Gamboa, and then in France (Macchiavello 2017, pp. 28–77; de la Garza and Vargas Santiago 2016). Balmes was also exiled in France with his family in late 1973 after being accused of being a political activist who organized armed groups and was exonerated from his position as Dean at the University of Chile. The difficulties encountered by those exiled immediately reactivated the network of solidarity formed previously through the Encuentro de Plástica Latinoamericana (Encounter of Latin American Plastic Art) organized by Casa de las Américas in Havana in 1972, which had brought together like-minded Latin American artists and intellectuals under the notion of resisting cultural imperialism and cultural penetration (Macchiavello and Juliana Suárez 2015). In France, Balmes contacted Brazilian artist Sérvulo Esmeraldo and received a friendly hand from Argentinean artist Julio Le Parc to find a studio for himself and his wife, painter Gracia Barrios, and was soon making posters for solidarity movements for the Chilean people while joining the International Brigade of Antifascist Painters organized by Le Parc. Miguel Rojas Mix, who also exiled in France with his wife, as well as the ex-Dean Pedro Miras, set out from the start to plan the possibility of reconfiguring the MS abroad with other members of IAL and supporters of the Museum exiled in Spain, and first attempts were made to recover the donated artworks.

During the II Encuentro de Plástica Latinoamericana of October 1973 in Havana, which had no Chilean participation due to the coup, participants thought about placing the works of the MS under the custody of the United Nations and a telegram to the Secretary General was reproduced in the journal Revista Casa de las Américas in January 1974. Many such ideas were proposed between 1973 and 1975, at a time when solidarity groups and events were created in different countries to repudiate the military Junta and human rights organizations expressed concern for Chile. Solidarity networks that had been dormant or timid flourished after the military coup. If solidarity with Allende’s government had provoked suspicion, after the coup there was less hesitation, as many felt personally, even intimately, touched by the traumatic events and the violations of human rights occurring in the country. For several organizers, the Museum became a refuge and a home, a space of containment and trust that enabled collaborative action, and a therapeutic labor of love that gave a renewed sense of affirmative purpose to their lives, even in bleak circumstances. As María Eugenia Zamudio would express in a letter to Casa de las América’s subdirector, Mariano Rodríguez, in August 1976: “For all the compañeros who live in Spain and especially for me, this has been a revitalizing work and we are devoted to it with immense enthusiasm” (Macchiavello 2018). For those who were organizing resistance movements in the cultural front, like Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman, who had been cultural advisor for Allende’s government and created the Cultural Commission of Chilean Resistance in France with members of the Communist and Socialist parties, the Museum was a symbol of continuity with a past that should not be forgotten. However, he expressed disbelief in the efficacy of the strategies employed and the real possibilities of swaying the current authorities in Chile to release the donated artworks. After intense legal consultation with lawyer Joë Nordmann and a series of failed attempts to recover some of the artworks (for example, Dore Ashton’s efforts with the US ambassador in Chile) the idea began to lose momentum (Macchiavello 2016, p. 41).

It was around this time that a new call was formulated to help the Chilean resistance through renovated acts of solidarity: the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende (MIRSA, International Museum of Resistance Salvador Allende). As with the “origins” of the MS, we can also speculate about the beginnings of the MIRSA. The idea certainly travelled and one of its pigeon carriers was Miria Contreras. Best known as one of Allende’s secretaries, who had an intimate and long-standing relationship with him, “Payita” as she was nicknamed, had been in charge of managing donations and loans of artworks from the presidential palace (including some interactions with Casa de las Américas and the MS), and due to her experience she had been temporarily managing the gallery of her sister Lina Contreras, Galería El Patio. As a highly sought out figure when the coup broke out (she had seen Allende at the government palace when the military had begun to attack it, and lost one of her sons that day), she had to hide and only after months was able to get out of the country, receiving asylum in Sweden (Macchiavello 2016; Lebeau 2019). She settled in Cuba and made a home in Havana with her son Max and her sister Mitzi, while developing a close-knit friendship with Beatriz Allende, one of Allende’s daughters who was exiled in Cuba and who had quickly formed the Comité Chileno de Solidaridad con la Resistencia Antifascista (Chilean Committee of Solidarity with the Antifascist Resistance) on 8 October 1973 (Harmer 2016). Familiarity was thus central not only to Payita’s introduction to Casa de las Américas and the ways in which it became her casa, her home, and the office where she and Mitzi worked for the new museum. Familiarity was also crucial to an everyday life in which politics, art, culture, diplomacy, and domesticity were intimately woven, in which borders between political commitment, family, and friends became blurred, sometimes pleasurably and joyously and sometimes painfully. This was another type of sustaining net in which asking a friend to keep an eye on the children or caring for a friend’s mental health (as Payita often mentioned in her letters to Mariano Rodríguez and friends concerning Beatriz’s depression) was threaded to being present at an art opening to show official political support as much as making bank deposits for an underground network of resistance.

Political resistance from Cuba led to international threads and new weavings connected to the second phase of the Museum. A neighbor of Payita in Havana was Sonja Martinson Uppman, who had previously worked in Chile before the coup and assisted with asylum seekers at the Swedish embassy before embarking to Cuba with her then-partner Max Marambio. Martinson Uppman carried back to Sweden the seeds of their burgeoning friendship and helped to develop a MIRSA collection (Macchiavello 2016, pp. 54–55). She assisted the director of the Moderna Museet, Björn Springfeldt, in the call for donations of Swedish artists and careful selection of artworks that represented contemporary art in Sweden, including the work of Slettemark, even when those decisions contravened the political (and stylistic) desires of the Chilean exiles who wished for more ample participation.4

The idea of a Museum of Resistance grew strong roots at Casa de las Américas, receiving the support of both Mariano Rodríguez, with whom Payita developed a strong friendship, and its director, Haydée Santamaría, who personally wrote letters to selected artists like Matta and Le Parc to help with the project. This new version was conceived as a wandering museum, headless and centerless, without walls; a museum that both accepted and disregarded national borders, a museum in exile; a museum that could sell its artworks so as to support multiple forms of resistance; a museum as a gesture, capable of agitating, a museum with clear intentions: to resist by existing, even while mutating forms. Or resisting because it transformed.

After Payita proposed the project of the Museum of Resistance to members of the MS in France in 1975, two official nodes formed in Paris and Havana, from where members of the museum’s new Secretariat (Balmes, Miras, Rojas Mix, Contreras) began to articulate a larger network of connections to get support (Pedrosa continued to collaborate until 1977, yet did not form part of the Secretariat). In its December 1975 call, the MIRSA was described as a museum based on artists’ donations made both as “a testimony of solidarity” with the people of Chile fighting fascism, and specifically “as a political instrument of agitation and propaganda.” Donations were conceived as individual and collective gestures of support and resistance, as well as a further call to others to respond and take responsibility. Committees of support featuring a range of stellar figures from different cultural domains were to be formed and donations made in each country would be part of a traveling exhibition, creating an ideal feedback loop of more donations in other cities. As the MIRSA continued to grow, its seeds would also be carried further and sprout in other nations, multiplying endlessly and keeping the idea alive, resisting by repeating its act of remembrance, refusing to be forgotten. While a large exhibition was envisioned displaying the most representative works of all collections (an idea never fully accomplished while in exile), the museum’s roaming would finally cease when democracy returned to Chile. Only then, as if awaiting a promised land, all works would return and be reunited with the half of the family that had remained sequestered and silenced in Santiago, to form part of the Museum of Solidarity Salvador Allende.

Solidarity in resistance seemed to be an even more powerful concept and in a few years MIRSA support committees had been created in Mexico, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Cuba, Venezuela, Canada, the United States of America, France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Finland, Poland, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, the URSS, Iraq, Mongolia, as more donations and touring exhibitions were made and promised from other nations. Once again, many hands labored for its cause and complex networks of politicians, lawyers, family members like the daughters of Waugh and Contreras (Pilar Fontecilla and Isabel Ropert, who lived in Europe), artists, friendly scholars, and monks contributed with phone calls, letters, conversations, ideas, collecting art works, transporting, hanging, promoting, cataloguing, storing, and emotional support, all equally necessary acts that helped weave the threads of resistance together. However, the MIRSA also found resistance within. A particularly sensitive issue was the fourth clause that stipulated sales of artworks. The overall notion of supporting the resistance of the Chilean people allowed for many slippages and foggy areas concerning who determined when the works were sold, who handled the sales and where the funds went, or how they would be channeled to support which resistance: the families of the disappeared or detained, the lawyers, informational bulletins, the clandestine armed resistance? Selling went against the anti-capitalist gesture of donation that had animated the Museum’s first solidarity phase, creating deep rifts among the Secretariat and beyond, as well as silences and forgetfulness, with a few receipts attesting to scattered sales. It introduces a stiff knot in the museum’s fabric that has been willfully ignored and it questions how we thread ourselves into the telling of new stories about it. Donations are complicated when they operate on the logic of the gift, for its recipient might be unclear, whether it is a Museum dedicated to an idea (and named after an individual), a family, or a people.

Donations also responded to many factors, varying according to local and global political climates, personal and party interests, material possibilities, clashing tastes and notions of art as much as feelings and their political manipulation. Following the paper trails left by Contreras at Casa de las Américas offers a glimpse into how she navigated the intricate waters of Cold War politics in East Germany, Poland, Yugoslavia, and the URSS to get donations, employing her personal political acumen and known charm while negotiating the desires of a multiplicity of local authorities and political parties, taking the temperature of each context, sometimes alone (and finding solace in letters written to Rodríguez with who she could discharge her frustrations, despair, and anxiety) and sometimes receiving the informed opinion and tactical counsel of representatives from different Chilean Left parties reconstituted in exile. Politicians clearly grasped the value of the MIRSA as a stage, as much as the latter’s members took advantage of existing political networks to gain visibility and enact the museum’s acts of counter-memory. The complexity of these meshes can be seen at one of the first pair of the museum’s exhibitions in France in 1977, which was organized in conjunction with the World Theatre Festival of Nancy. The latter was dedicated that year to Latin America and offered an international colloquium on art, politics, torture, and human rights that included speakers from Portugal, Brazil and Bolivia among others, while highlighting the presence of Chile. The festival’s director, Jacques Lang, made a call to set the basis of a common cultural struggle between Europe and Latin America. The MIRSA’s exhibition was in turn attended by soon-to-be presidential candidate François Mitterrand of the Socialist Party who paraded the grounds and was photographed in front of the movable murals made for the occasion by the International Brigade of Antifascist Painters along with Hortensia Bussi, Allende’s widow. At a time when traditional Leftist parties in France were losing adherents and trying to reconfigure their social platforms, such gestures of international solidarity with oppressed peoples, as declared by Mitterrand, could also help bind its internal differences, an act of political maneuvering that was duly noted in the opposing right-wing press (Macchiavello 2016). Writers Ariel Dorfman and Julio Cortázar, who participated at the colloquium along with Régis Debray and Otelo de Carvalho, spoke of the necessity of joining cultural with political forms of resistance, and the press gestured towards the MIRSA’s collection of stitched and woven fabrics in particular, the arpilleras, as a sign of this intersection. Even Mitterrand was quoted by the press mentioning how touched he felt when visiting MIRSA’s collection and being confronted with these fragile yet powerful textiles made by Chilean women, and several of the festival conference’s participants, like de Carvalho, were spurred by the MIRSA to pledge their commitment to solidarity with Latin American peoples. Since the arpilleras were made in Chile, they seemed to contravene the main strategy of the museum, the donation of works by artists living outside of Chile, and yet they were to become one of its most potent signs of resistance and a call in themselves to perform further acts of solidarity. How were they woven then, into the MIRSA?

5. Arpilleras: Stitched Calls

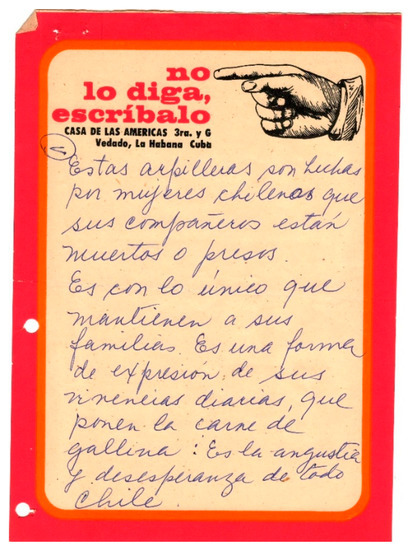

For this purpose, we can turn our attention to a rather different call, seen in Figure 3. This is a memo of institutional memory as much as a case of testimonial memory, written on a paper pad with the address of Casa de las Américas in Havana. A pointing finger is seen in the image followed by an authoritative printed request reminding Casa de las Américas’s staff to record in writing their communications and thus to leave a paper trail (“write it down, don’t say it,” it reads). In spite of the commanding gesture and tone, the handwritten words below it speak instead of a body that feels, that connects emotionally and sensitively to images, that has become tied to a memory knot. It reads in broken Spanish: “These arpilleras are made by Chilean women whose partners are dead or imprisoned. It is the only way they sustain their families. It is a form of expression of their everyday lives, which gives you goosebumps: it is the angst and despair of all Chile.”

Figure 3.

(Contreras, Miria): (Arpilleras mujeres chilenas), undated, Notes. Fondo MIRSA. Subfondo Secretariado Ejecutivo-Miria Contreras. MSSA Archive. Cod: c0116; c0117. Used by permission of MSSA.

The text attempts to translate the psychic, emotional, and physical experience of seeing and be-holding, touching and being touched by the arpilleras. It evokes the impact caused on the writer by the small sewn burlap sacks made with hand-stitched fabrics depicting the everyday realities of the women who made them. By then, these embellished and colorful patchwork cloths had been produced for almost two years by groups of women in the shantytowns and margins of Santiago, many of who had lost husbands and family members to the dictatorship. Supported by the Vicariate of Solidarity of the Catholic Church, the arpilleras’s workshops emerged as a means of subsistence out of the desperate need of a small group of women “to placate the grief, to remedy economic crisis, and to feed the children that were without fathers” (Agosín 1996, pp. 11–12). These represent survival in material terms and as the resistant embodiment of memories, can be considered acts of denunciation and of material necessity, a working through trauma, and part of a process of healing, sharing, being heard and seen. Though the memo is undated, it corresponds to the first phases of the arpilleras’s journeys from Chile to other countries in 1976, and how the MIRSA intersected and facilitated their circulation. The handwriting possibly belongs to Payita, and it is a more official, cleaned up version of a note scribbled quickly by her close friend, gallerist Carmen Waugh. In it, Waugh mentions that she has sent Payita two arpilleras, describing them with the aforementioned text. No more comments are made, as if the works spoke and gestured for themselves, exerting their influence. As described in the memo, the arpilleras make you shiver, the corporal electricity generated by an affective experience of intense empathy.

I will not attempt here an analysis of the arpilleras as a medium or genre. This has been done over time by Marjorie Agosín, Betty LaDuke, Eliana Moya-Raggio, Jacqueline Adams, and Julia Bryan-Wilson among many others, and continues today. As in the case of Slettemark’s poster, I am interested in looking at these arpilleras in relation to the MIRSA’s first stages, as physical objects and signs that do many things at once, translating, transporting, intervening, calling out, trapping in meshes, and sending shivers down the spine.

The original message confided to Payita the emotional and sensorial experience of Waugh. It translated into handwritten words the sense of being touched by the arpilleras, stirred by their contents, their rudimentary yet careful forms, the dire context in which they were produced, and by a sisterly feeling of connection with women making do with leftovers, in spite of vast class differences. In her own relay of the message as an institutional memo, Payita reframed the contents of Waugh’s rushed note, emphasizing the affective power of the arpilleras as physical documents of the women’s everyday struggles.

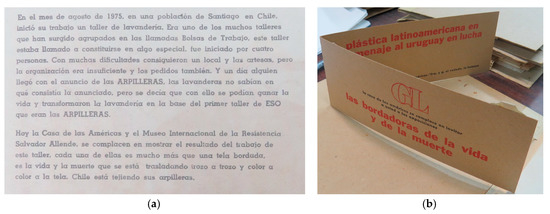

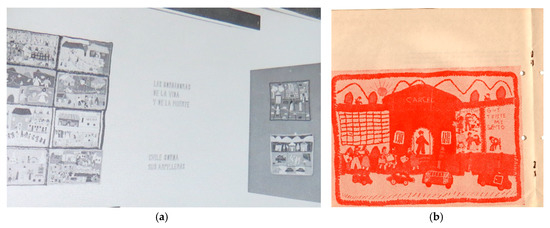

Casa de las Américas picked up on the memo’s affective and political connotations. An impromptu exhibition of 33 arpilleras was inaugurated in January 1977 at the vestibule of Casa’s gallery, Galería Latinoamericana, acting as an eloquent appendix to an already planned exhibition of solidarity with the Uruguayan people, also gripped for several years under a civic-military dictatorship (Figure 4b and Figure 5a). The catalogue succinctly mentioned that in August 1975 the idea of creating arpilleras had been brought to a laundry workshop supported by the Vicariate of Solidarity where several women worked (Figure 4a). Personal experiences of the arpilleristas were quoted as the anonymous collective voice of the taller, and some works were reproduced in bright red color, translating the bloodlines threading hope and despair into the patchwork fabrics, as suggested by the exhibition’s title: Bordadoras de la vida y de la muerte. As seen in the arpilleras reproduced in the catalogue (Figure 5b), different aspects of the women’s everyday life were represented, weaving the personal and the political: feeding chickens, washing clothes, going to the cemetery, giving birth, are threaded to going to jail, asking the family member incarcerated how they are and getting as a response an “I’m feeling so sad”: qué triste me siento states a crude embroidered text, textured like a scar. A short promotional film of the exhibition made by renown Cuban cinematographer Santiago Álvarez, for the newsreel of ICAIC (Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry), further exalted their emotive component by gently zooming into the arpilleras that included texts (including a cemetery scene showing a tomb with Allende’s last name), accompanied to the Andean sounds of Victor Jara’s song “La partida.”

Figure 4.

(a) Detail from catalogue Bordadoras de la vida y de la muerte, 1977, and (b) invitation to dual exhibition. Casa de las Américas, Archivo Área Plástica. Images taken by the author.

Figure 5.

(a) Exhibition view of “Bordadoras de la Vida y de la muerte,” Exhibition at Casa de las Américas, January 1977. Photograph in Casa de las Américas, Archivo Plástica. (b) Detail from exhibition catalogue “Bordadoras de la Vida y de la muerte,” published by Casa de las Américas. Used by permission of MSSA.

In another letter by Waugh kept in the archives of the Plastic Arts section in Casa de las Américas, she requests that the arpilleras of the 1977 exhibition be returned to her as soon as possible, as she was planning to exhibit them in London, Stockholm, and Madrid. Both of Waugh’s letters point to the existence of an underground network of political and artistic connections related to resistance and to the arpilleras that was rendered invisible with time. Its threads linked the Chilean artist Alberto Pérez to Waugh through Carmen’s sister, Paulina Waugh, and the Vicariate. Pérez had helped organize the exhibition “Mateo 25. El llamado de Cristo a la solidaridad” (Matthew 25, the call of Christ to solidarity) in August 1976 at the gallery run in Santiago by Paulina Waugh, in which a group of arpilleras from the workshops supported by the Vicariate were shown along with woodcuts by the young artist Teresa Gazitúa based on the Christian evangelist’s text. The Vicaría (established in January 1976) developed the project of joint exhibitions to help the arpilleristas sell their work, and supported them by generating publicity and allowing for interchange of knowledge and techniques between artists and artisans (Stern 2006, pp. 81–89). As the arpilleras were sold in support of the women, they were increasingly read as symbols of resistance, whether they actually represented denunciatory messages or not. In the Mateo 25 catalogue, such symbolism was heavily drawn on and tied to affective links associated with solidarity, as Pérez emphasized in his piece the shared “force of the sentiment” that could be felt in the arpilleras and Gazitúa’s prints, which he summarized as the Christian reminder of human fraternity, in spite of political, class, or ethnic differences (Figure 6). Written for a Chilean audience trapped in an environment of censorship and repression, Pérez’s text evoked the Christian call to recognize our human codependence and responsibility, while noting the ability and risk implied in seeing oneself in the other. Appealing to a mostly Christian audience, Pérez redeployed this message of responsibility as a reminder of our ethical accountability beyond political divides. Instead, in the catalogue made for the Havana exhibition, Pérez’s text was rescinded and the quotes were drawn from the Vicaría magazine Solidaridad, a publication distributed through Catholic networks since May 1976, which had featured an article on the arpilleras titled “Bordadoras de la vida y de la muerte,” stressing their wrenching and gendered testimonial component.

Figure 6.

Typewritten transcription of the text by Alberto Pérez, originally in the Mateo 25 catalogue. MSSA Archive. Used by permission of MSSA.

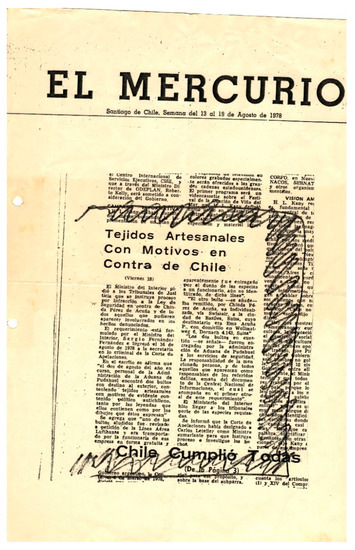

This symbolism of resilience was carried internationally as the arpilleras were smuggled out of Chile in suitcases and wrapped in bundles passed as ragged personal belongings, to be sold through networks of resistance in Europe and the United States. Since arpilleras’s availability was limited, other means were sought to commercialize them and collect funds for the women, whether it was through postcard reproductions or the sales of the book Un peuple brode sa vie et ses luttes at supportive solidarity institutions like the charity organization OXFAM in London and CIMADE in Paris. Some of the MIRSA’s own arpilleras were made in Cuba by Chilean women, introducing a complicated knot in the narratives about their origins. Their existence was explained as an extended gesture of solidarity from exile, since they helped chronicle and thus denounce with more freedom what was happening in Chile, as stated in a text prepared for the International Conference About Exile and Solidarity in 1970s Latin America, which took place in the cities of Caracas and Mérida, Venezuela, in October 1979. But as the arpilleras’s popularity as political symbols and concrete gestures of solidarity with the Chilean people grew in the following years, becoming part of “solidarity art,” defined by Jacqueline Adams as “art that people buy with the intention of helping the artists financially and expressing solidarity with them” (Adams 2018, p. 241), so did the reactions to them by agents of the Chilean dictatorship. When Paulina Waugh exhibited for a second time a group of arpilleras in January 1977, her gallery was the object of a premeditated fire that ended up destroying it. Waugh had to seek help from the Vicaría and was interrogated and threatened for having exhibited these works, and soon left the country (Stern 2006, p. 83). One year later, the power of the arpilleras continued to be evoked in the conservative press, which accused the objects of having almost magical effects on others as political propaganda. The newspaper El Mercurio claimed in August 1978 that the government would consider the export of any work associated with anti-Chilean (and thus anti-government) propaganda as a criminal act. As if to prove this, the Minister of the Interior requested to initiate a process against Chinda Pérez de Acuña based on the infraction of the Law of Security, after a bag of arpilleras sent to Basel under her name was intercepted (while a similar bundle was being carried free of charge by an employee of Lufthansa) (Figure 7). Bundles of solidarity could also be explosive; as Payita mentioned in an interview for the bulletin of the Cuban commission to the UNESCO of 1977, the arpilleras demonstrated that resistance was ever changing forms and that “we can also fight with needle and thread.”

Figure 7.

Cut-out of press article, “Tejidos artesanales con motivos en contra de Chile.” El Mercurio, August 1978. MSSA Archive. Used by permission of MSSA.

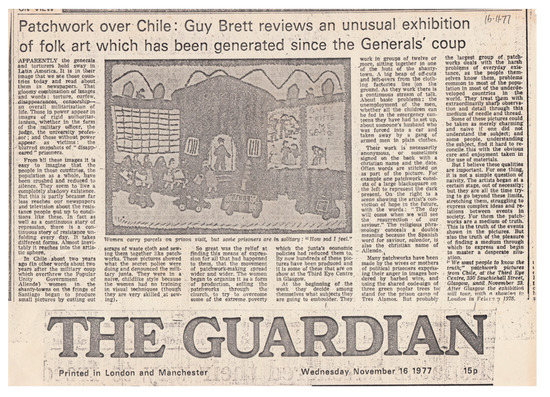

The arpilleras associated with the MIRSA continued to travel and exert their transformative influence. They not only were shown in the exhibitions of MIRSA in France at Nancy and Avignon, and in Madrid, Spain, but also toured the United Kingdom in a group of more than fifty (many belonging to artist Roberto Matta, who participated in some of the events, some loaned by other supporting institutions) between November 1977 and January 1978. MIRSA’s arpilleras were shown in countries with governments favorable to the resistance: a group made an appearance in Krakow, Poland, for the International Day of Women in March 1979, then at the Museum of Textile Arts in Lodz, between 30 March and 20 April 1979, alongside the collection of indigenous Guna embroidered molas donated to MIRSA in 1976 by the Panama committee of support; they were shown again in Krakow in 1980. Their varied reception and acts of framing (even remaking) merit more analysis, as to which aspects and meanings slipped through these meshes or were caught in them, as much as the intricate networks through which they circulated. At Lodz, for example, the arpilleras were described as sisters of the Soviet-inspired propaganda posters, due to their boldly simplified forms and the creation of an image of “the people in struggle” (Macchiavello 2018); in Cuba they were threaded to the graphic language of the cartel Cubano. Pérez understood them in Chile as a powerful example of popular art whose communicative and expressive force laid in its simplicity; while in England, the art critic Guy Brett discussed their “transnational” artistic merits and politicized context, anticipating resistance from local audiences who might not consider the arpilleras as “art” due to what could be regarded as their primitive crudeness or “naivité” (Brett 1977) (Figure 8). In other words, the arpilleras became multivalent gestures, their meaning and value disputed, controversial, still changing.

Figure 8.

Guy Brett, “Patchwork over Chile,” The Guardian, 16 November 1977. MSSA Archive. Used by permission of MSSA.

6. Conclusions: Art History within Woven Solidarities, Affects, and Times

Gestures like Slettemark’s may seem anachronistic, just like the word “utopia” seems to be discredited today. Yet, we can still respond to its call, its gesture of halting and connecting, to imagine other ways of doing, thinking, and feeling with, as we narrate our art historical webs. When exhibited in 2007 at the MSSA, visitors were invited to stop the flow, to connect with a situation and respond differently. Since its conception in 1971, the Museo de la Solidaridad has called out to artists around the world to be affected and not remain indifferent to the fights of others to live dignified lives, particularly the struggles of those in the so called Third World. This gesture reminds us of the multiple ways in which ethics have been articulated in the past decades and their continued resonance today. It reminds us that “The ability to respond is what is meant by responsibility, yet our cultures take away our ability to act—shackle us in the name of protection” (Anzaldúa 1999, pp. 42–43). As with all calls, this one resonates with and echoes those of the past, adding its voice to them rather than aspiring to any kind of smart novelty. Art historian Griselda Pollock asks: “How can we share the planet while allowing it to be uncanny, that is, a source of anxiety that may be important for resisting the mastering of our own sense of fragility by creating abstract models?” (Pollock 2014). As art historians, can we allow ourselves to be fragile, vulnerable, implicated with our objects of study, curious to the bone, letting go of the ambitions to generalize and produce abstract models? Can we instead let the summons of art works, museums, papers, memos, stitched fabrics, put us in relation again (as Schneider suggests), send shivers down our spines, so that in our writing and art historical practice we can shiver with others? I believe we can allow ourselves to be uncanny and strange as we braid our stories to those of others, keeping our threads distinct and yet entwined, as we respond to imaginary calls, and tell stories that ponen la piel de gallina.

Funding

A part of this research was funded by a FONDART grant, Proyecto de investigación Chile-Cuba, folio n. 417836, Fondart Nacional—Artes Visuales – Investigación 2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, Jacqueline. 2018. What is Solidarity Art? In The Art of Solidarity. Visual and Performative Politics in Cold War Latin America. Edited by Jessica Stites Mor and María del Carmen Suescun Pozas. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 241–57. [Google Scholar]

- Agosín, Marjorie. 1996. Tapestries of Hope, Threads of Love. The Arpillera Movement in Chile 1974–1994. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1999. Borderlands: La Frontera. The New Mestiza, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. [Google Scholar]

- Berríos, María. 2017. Por el futuro artístico del mundo. Mário Pedrosa y el Museo de la Solidaridad. In Mário Pedrosa. De la Naturaleza Afectiva de la Forma. Madrid: Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía, pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen, Lone, and Andrew Murphie. 2010. An Ethics of Everyday Affinities and Powers: Félix Guattari on Affect and the Refrain. In The Affect Theory Reader. Edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 138–57. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, Guy. 1977. “We want people to know the truth.” Patchwork pictures from Chile. Spare Rib, A Woman’s Liberation Magazine 63: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Padilla, Fernando. 2009. Suecia por Chile. Una Historia Visual del Exilio y la Solidaridad, 1970–1990. Santiago: LOM. [Google Scholar]

- Cofré Cubillos, Claudia, Francisco González Castro, and Lucy Quezada Yáñez. 2019. Mário Pedrosa y el CISAC. Santiago: Ediciones/Metales Pesados. [Google Scholar]

- De la Garza, Amanda, and Luis Vargas Santiago. 2016. Artistic and Political Networks between Mexico and Chile in the Seventies. In A los artistas del mundo/To the Artists of the World. Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende México/Chile 1971–1977. Ciudad de México: MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, pp. 158–88. [Google Scholar]

- Elsey, Brenda. 2013. As the World is My Witness. Transnational Chilean Solidarity and Popular Culture. In Human Rights and Transnational Solidarity in Latin America. Edited by Jessica Stites Mor. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 177–208. [Google Scholar]

- García, Soledad. 2019. Casa de experimentos: Preguntas y transformaciones recientes del Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende y su integración a la comunidad del Barrio República. Poiésis Niterói 20: 259–76. [Google Scholar]

- Harmer, Tanya. 2016. The View from Havana: Chilean Exiles in Cuba and Early Resistance to Chile’s Dictatorship, 1973–1977. Hispanic American Historical Review 96: 109–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högkvist, Stina, Terje Borgersen, and Frans Josef Petersson. 2013. KjARTan Slettemark: Kunsten å Være Kunst: The Art of Being Art. Oslo: Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2016. On Human Correspondance. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23: 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, Elodie. 2018. When Solidarity Became Art: The Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende (1975–90). In Past Disquiet. Artists, International Solidarity and Museums in Exile. Edited by Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti. Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, pp. 317–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lebeau, Elodie. 2019. Miria Contreras Bell (La Payita): Desafíos Epistemológicos para una Biografía. HAL Archives-Ouvertes. hal-02182507. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02182507 (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Macchiavello, Carla. 2009. A parar el match: Política, deporte y arte. Revista de Estudios Sociales 32: 146–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macchiavello, Carla. 2012. A Flag is a Weave. In 40 Años. Fraternidad, Arte y Política. Santiago: Museo de la Solidaridad, pp. 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Macchiavello, Carla. 2016. A Case of Collective Resistance: Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende. In A los Artistas del Mundo/To the Artists of the World. Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende México/Chile 1971–1977. Ciudad de México: MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, pp. 70–94. [Google Scholar]

- Macchiavello, Carla. 2017. Fibras resistentes: Sobre El/Los/Algunos Museos de la Resistencia. In El Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende. Edited by Claudia Zaldívar. Santiago de Chile: Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, pp. 28–77. [Google Scholar]

- Macchiavello, Carla. 2018. Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, Unpublished Report.

- Macchiavello, Carla, and Sylvia Juliana Suárez. 2015. Solidaridad, plástica, redes y revolución: Una crónica breve del surgimiento y oclusión del meridiano Chile-Cuba en el ámbito del arte latinoamericano. In Redes Intelectuales. Arte y política en América Latina. Edited by María Clara Bernal. Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes, pp. 175–226. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, Timothy. 2013. Hyperobjects. Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conselleria de Cultura País Valencia. 1978. Museu Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende; Valencia: Conselleria de Cultura País Valencia.

- Pollock, Griselda. 2014. Whither Art History? Art Bulletin 96: 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Rebecca. 2014. Theatre & History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Steve J. 2006. Battling for Hearts and Minds. Memory Struggles in Pinochet’s Chile, 1973–1988. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zaldívar, Claudia. 1991. Museo de la Solidaridad. Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Interview with Lesbia Vent Dumois, 21 June 2017. |

| 2 | Transcripts of the recorded talks were reproduced in the journal published by Pontificia Universidad Católica, Escuela de Arte, Cuadernos de Arte 4 (1997). |

| 3 | “This performace went on here and there and everywhere—at the time of preparing the Tennismatch. I walked around in the streets—carrying the Stopsign—Assemblage. The semilar [sic] to that I donated later to the Alliendemuseum.” Email communication with the artist, 22 March 2008. |

| 4 | Interview with Isabel Ropert Contreras, 18 August 2017. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).