1. Indigenous Futures or How to Poeticize Technology

In the last few years, the notion of “indigenous futures” has become a suggestive concept to highlight what indigenous politics and social philosophies offer for imagining a sustainable world outside of the capitalist, modern, and colonial world system. The recent issue of the

Art Journal (2017) dedicated to the subject is a testament to the growing scholarship on indigenous artistic practices and activism within mainstream spaces of contemporary art.

1 By elaborating on how Native American artists have made a critical intervention into the entwined relationship between colonialism and environmental destruction, the issue discussed a number of projects that protest corporate capitalism’s growing threat to the well-being of our human and nonhuman ecosystems (

Morris and Anthes 2017). These art historical studies, together with Zoe Todd’s article “Indigenizing the Anthropocene”, as well as Jessica Horton and Janet Catherine Berlo’s “Beyond the Mirror: Indigenous Ecologies and ‘New Materialisms’ in Contemporary Art”, have underlined the multiple ways in which indigenous communities maintain forms of relating to the environment based on sustainable politics and ethics of solidarity (

Todd 2015, pp. 241–54;

Horton 2017, pp. 48–68;

Horton and Berlo 2013, pp. 17–28;

Franke 2010;

García-Antón et al. 2018).

Building upon this proposal for “indigenous futures”, this essay will elucidate—through the work of the Kichwa artist Manuel Amaru Cholango (b. Ecuador, 1951)—how Latin American indigenous artists have engaged since the early 1990s in advancing a critique of colonialism that addresses the destruction of the environment as well as the sustained oppression of indigenous peoples.

2 Following the polemical 500-year commemoration of the discovery of America in 1992, indigenous communities in Latin America led some of the most radical uprisings in history, condemning not only the celebration of 1492, but also the rhetoric of “encounter” that the events espoused, arguing instead that colonialism was still ongoing. While there were a number of protests, symposia, and artistic projects that questioned the commemoration of the conquest, Cholango’s response to the quincentenary connected coloniality with the impending environmental crisis.

Since the early 1990s, Cholango has experimented with the boundaries between art and technology through installations and media site-specific works. Born in the small rural town of Quinchucajas in the Ecuadorian highlands, Cholango was trained by his mother, who imparted in him a deep understanding of Kichwa cosmovision and Andean social philosophy (

Ortiz Castro 2017, p. 11).

3 As a young adult, however, Cholango pursued a university education in Quito, where he studied mathematics and geology. In the late 1980s, he was granted a fellowship to continue his studies at the Institute of Geological Sciences in London, where he lived for a few years. It was during this time and upon his first visit to the National Gallery that Cholango became captivated by Rembrandt’s paintings and his mastery of chiaroscuro. This experience fostered his curiosity about the arts, prompting him to abandon his studies in favor of an artistic career. He remained in Europe, living for a while in Paris (1982–1984), where he apprenticed as an artist, but he would later on establish a studio in the city of Trier in Germany. His training in mathematics and geology coalesced with his artistic inclinations, allowing him to develop a practice that articulates a criticism of technology and scientific knowledge from within. Cholango, moreover, has stated that he wants to “poeticize technology” and subvert its ordinary function to radicalize our understanding of the essence of nature by reconsidering the relationship between man and the environment.

4 Seeing technology as complicit with colonialism, Cholango’s works do not contest Western technology or scientific advancement per se; they instead challenge science’s claims to universal truth and the belief in modern technology as a universal mode of knowing (

Fernández 1999, p. 58;

Fernández 2017;

Mariátegui et al. 2009).

5 Despite the fact that he divided his time between Germany and Ecuador for several decades, Cholango early on became an active member of the indigenous social movement in his native country. In fact, the natural disaster caused by the Texaco oil spill was one of the primary catalysts for the artistic projects he would carry out, especially his incursion in the use of cybernetics and technology. The devastating Texaco (now Chevron) oil spill in the Ecuadorian Amazon, which systematically contaminated water sources as well as soil in the province of Sucumbios in the east of the country between 1964 and 1992, resulted in one of the most severe environmental catastrophes on the planet (

Demos 2017, p. 102). Corporate neglect followed what was in fact an attack on the public health of thousands of indigenous peoples who lived in the region, as well as the irreversible destruction of the earth, resulting from the hundreds of open toxic pipelines left behind and waste dumped in rivers (

Davidov 2016). That is why, when calling to “poeticize technology”, Cholango is attempting to decolonize it, which, on the one hand, underscores the dangers of the Western logic of technology and, on the other, advances the concept of Andean technology as an alternative approach to world making that is central to producing the very possibility of the future.

6In addition to being a pioneer of cybernetics and digital art, Cholango was also one of the first indigenous artists to participate in mainstream artistic circles in Ecuador. Despite a large indigenous demographic, the only precedent for indigenous representation in the local artistic milieu was the Indigenista movement in the early twentieth century (1920–1960s). While, at times, proposing a critical look at the condition of the indigenous population, this “movement” became an avant-garde project that celebrated the cultural makeup of the mestizo by romanticizing the pre-Columbian past (

Greet 2009, pp. 16–17). Promoted by renowned Ecuadorian painters, such as Oswaldo Guayasamín (1919–1999), Eduardo Kingman (1913–1997), and Camilo Egas (1889–1962), Indigenismo became a well-established tradition and was influential over the course of several decades.

7 Paradoxically, the works of art that followed this pictorial trend are today critically viewed as appropriations of indigenous subjects that perpetuated the colonial erasure of native epistemologies and their systems of representation (

Kingman Goetschel 2012, pp. 67–69). Being the first artist to break with this “tradition”, Cholango’s works are indicative of a number of transformations in the cultural politics of the country at the start of the 1990s.

8In 1992, Cholango received an invitation from the renowned Quiteño cultural promoter Wilson Hallo Granja to participate in the IV Bienal Internacional de Pintura in Cuenca (1994), which would be his first exhibition in his native country.

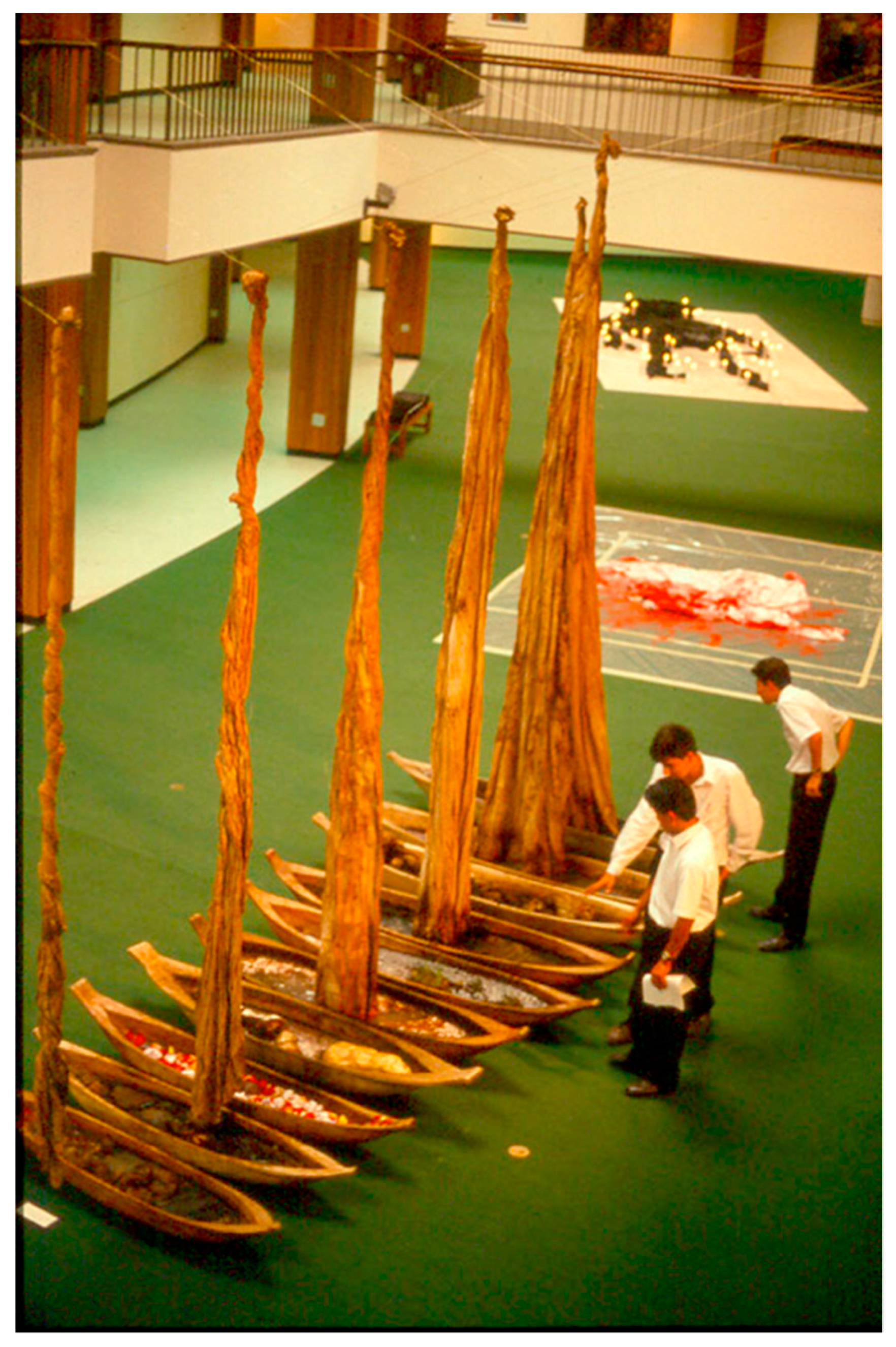

9 With the quincentennial celebration of the “discovery” of America the year prior (1992–1993), Cholango proposed for the Biennial exhibition the installation titled

Las carabelas de Colón todavía navegan en la tierra (

Columbus’ Caravels Still Sail the Earth) (1994,

Figure 1). The installation, comprising ten small wooden canoes containing dead fish, petroleum, and mud, established a direct relationship with colonialism by referencing the most emblematic icon of the conquest—Christopher Columbus’ vessels. Reflecting on the role that the quincentenary played in fostering his artistic concern with colonial exploitation, Cholango noted the following:

On the one hand, the installation addresses the problem of pollution and thus the need for people to become conscientious about the destruction of the environment. On the other hand, it speaks of the colonization of America. The Spaniards brought good things and bad things. Among the bad things, they brought plagues, epidemics, and the flu. The discourse on the five hundred years of conquest is very relevant and it is also universal

As Cholango pointed out, the dregs inside the wooden caravels were a commentary on the destruction of the environment as a result of the modern/colonial logic that enables the interminable exploitation of the earth.

11 This was an important position to take in the early 1990s, for, at the time, only a few artists in Ecuador recognized the relationship between the problematic commemoration of the quincentenary and calamities such as the disaster caused by Texaco in the Ecuadorian Amazon (

Davidov 2016, p. 58;

Demos 2017, p. 102;

Kronfle Chambers 2017, pp. 56, 61).

12 In fact, it was the realization that colonial power structures were still in place that instilled in Cholango an urgency to demonstrate that technology was not only directly complicit with colonialism but also enabled its perpetuation and expansion.

Cholango’s installation

Columbus’ Caravels Still Sail the Earth was, moreover, an unprecedented proposal for the Cuenca Biennial, which, at that point, was still a conventional painting salon. Creating some controversy due to the installation format, the piece was excluded from the painting competition and was received negatively with the exception of the guest juror and prominent art historian, Shifra Goldman, who spoke highly on behalf of the artist claiming that “if Cholango’s installation had been included in the contest, there would have been no questions about the real winner” (

Haddaty 1994).

13 The work’s form, however, was not exclusively the reason it was rejected; it also had to do with the fact that the dead fish and the petroleum naturally stunk up the museum halls (

Gilbert 1994). The putrid smell of the installation ironically aggravated the sensibilities of those who, insisting on more conventional artistic forms, undermined the artist’s intent. To this criticism the artist retorted with irony that “people seemed more offended by the pungent reek of an art installation than by the fact that our rivers actually smell like that” (

El Comercio 1994).

14 This environmentally conscientious art piece, therefore, combined the colonial experience of invasion with the concomitant exploitation of the earth to make an intervention in the art world that would render visible the intrinsically complex character of coloniality. The artist’s commentary, moreover, anticipated the type of ecocriticism that has become common in the art world today, for it also underlined in its moment how environmental violence plays a major role in the system that upholds colonial domination (

Toledo 2003).

Cholango and other indigenous artists’ concern with nature also has resonances with contemporary art’s increasing interest in eco art.

15 However, while a variety of artistic collectives support practices of environmental justice as well as degrowth and antiglobalization social movements around the world, their investment in these causes ultimately differ from what is at stake for indigenous peoples in the protection of the environment. Philipp Altmann underscores this point by explaining that “an ecological understanding of the indigenous movements as guardians of whatever or [as] ecological Indians is a misrepresentation. Ecology does not make sense if there is no separation between nature and culture” (

Altmann 2017, p. 753). In this sense, Latin American indigenous social movements, or in this case artistic practices, are not in and of themselves “environmentalist”, as they do not conceive of nature as being distinct from humans—that is, as an entity that unwillingly or without intent simply “endures” human control either for its destruction or its protection (

Altmann 2017, p. 749;

Caria and Domínguez 2014;

Gudynas 2011).

16 Rather, indigenous social philosophies recognize the animism of all entities establishing relational epistemologies and subjectivities that bring the world into being as an interconnected and interdependent web of mutually supported agents (

Sillar 2009, p. 371).

17 In this regard, the environmentally conscientious art pieces created by Cholango go beyond an environmental commentary and establish a much larger decolonial critique that sees the exploitation of the earth as a corollary to the ongoing oppression of indigenous peoples.

18It is also important to underline, along with T. J. Demos, that although studies on new materialism, such as Jane Bennett’s

Vibrant Matter, see humans as being part and parcel with nature, it was indigenous scholars who, in their millenarian thought, initially elaborated this multispecies approach.

19 Following Bill Sillar, it is also possible to see that these contemporary theories differ from Andean notions of animism in that the latter not only recognize the agency of nonhuman entities but perceive them as agents with intentionality (

Sillar 2009, p. 371). Animism more specifically refers to the Andean millenarian ontology that explains that entities, such as plants, animals, and ancestors, and all natural things, such as rivers, stones, or mountains, have a spirit or vital force that endows them with the capacity to relate to and affect humans (ibid., p. 371). In fact, Axel Nielsen, Carlos Angiorama, and Florencia Ávila, in their article “Rituals as Interaction with Non-Humans: Prehispanic Mountain Pass Shrines in the Southern Andes” speak to the question of intentionality as a principle of the animate world when defining the idea of an agent as, “anything to which human practices accord

power (capacity to alter a course of events),

awareness (based on a particular understanding of the world),

intentionality (goals, interest, value, affects, and desire),

choice (possibility of acting otherwise), and therefore

responsibility of some sort” (

Nielsen et al. 2017, p. 242). Within an array of theoretical paradigms that today incorporate post-anthropocentric critiques and advocate for a multispecies approach, these distinctions are important as they inform and shape the construction of a specifically Latin American indigenous proposition that contests modern technology and coloniality at large.

2. Contesting Imperial Visuality

Cholango’s preoccupation with colonialism has found its focus in recent years in explicitly addressing the use of advanced technologies for monitoring and controlling reality. Installations such as

Narciso and

¿Miran tus ojos la realidad? (Can Your Eyes See Reality?) interrogate the construction of the modern gaze, offering instead a form of countervisuality. In an interview with Christian León Mantilla, the artist stated that:

Technology is the right hand of capitalism, and of colonialism as well. It is in this regard that we need to consider that science, which is capitalism in and of itself, has also destroyed the environment. In this sense I fight against technology from within, using video as the medium to underscore its destruction of the earth.

20

In thinking through video, Cholango is not, however, addressing a material idea of technology by which video serves to represent the destruction of nature. Rather, he is establishing a concern with the logic of modern technology as a mechanism of control emblematic of the capitalist–colonial system. In fact, Cholango is more interested in the question of visuality implicit in video technologies following Nicholas Mirzoeff’s concept of “imperial visuality”. According to Mirzoeff, this term does not simply denote a theory of seeing and of representation; it relates instead to the optical apparatuses that combine both the social imaginaries and technologies that make authority both perceptible and natural (

Mirzoeff 2011, pp. 6–7). Visuality, in other words, is an optical paradigm that brings the world into being (view) through relationships of domination, violence, and power. In that sense, Cholango’s prompting to decolonize technology is also a call to contest this hegemony of ocularcentrism by bringing into being other regimes of visuality that can yield non-anthropocentric ways of relating to the environment.

In his 2007 installation titled

Narciso (

Narcissus,

Figure 2), which was presented at his 2011 mid-career retrospective exhibition

Amaneció en medio de la noche (Quito, 2011), Cholango confronts the viewer with the gaze of an ox (

Reus 2011). In a gesture that emulates the act of Narcissus, the work prompts visitors to lean over a large bowl of water so that they can see their own reflections. Instead of facing their mirrored self-representations, visitors are quickly faced with ten oxen eyeballs staring back at them. The image of the visitor is captured and enlarged with the use of video cameras and projectors, prompting a reflection on what animals see and what they understand or know when they see. In bringing to the fore the instruments of vision such as the mirror, the eye, and the camera, the piece discloses the politics of looking, underscoring the power relation that is inscribed in the modern paradigm of visuality. In fact, the use of video elaborates a critique of the “Cartesian scopic regime” (

Jay 1988, pp. 10–11). To delineate the relationship between modern ocularcentrism and the logic of coloniality that is at the heart of man’s sense of superiority over nonhuman agents, Martin Jay explains that the Cartesian scopic regime is founded upon the Cartesian notion of reason, which is in itself based on the separation between object and subject.

21 Following this divide,

Narciso’s deployment of the oxen’s gaze challenges the assumption that as

seeing subjects, only humans can visualize and consequently dominate the “knowable” world. In presenting the stare of an ox and, therefore, confronting the viewer with the animal’s “right to look”,

Narciso enables the emergence of an animal subject that challenges the universality of

man.

The reversed gaze of

Narciso, moreover, reverses the authority of representation. Unlike the perspectival conditions premised by the Cartesian scopic regime, in

Narciso, the traditional onlooker (the human) becomes situated by the representation of his image through the eyes of the ox. Donna Haraway explains that the unsituated positionality set forth by modern ocularcentrism leads subjects to believe in their capacity to apprehend the truth about the world objectively and universally—a capacity that is granted precisely by the viewer’s position, as one supposedly external to the material world (

Haraway 2013, pp. 679–80). In subverting the technology that yields forms of disembodied visualization,

Narciso situates the human viewer as seen from the perspective of the ox. The change in positionality forced by the reversal of the gaze challenges the viewer’s claims to objectivity and, therefore, to truth, because by revealing the ox as an equally knowing subject, the piece makes evident that to bring the world into being (visually) also necessitates becoming with the world ontologically, that is, developing an other-than-human consciousness.

By invoking the notion of countervisuality, I do not necessarily mean to suggest that the ox is reproducing the violence of the gaze that humans impose on each other and the environment. As Mirzoeff claims, countervisuality and visuality are not “a battle for the same field”, implying a struggle for domination through an imperial visuality that reasserts a “colonial environment” (

Mirzoeff 2011, p. 14). Rather, countervisuality tries to make visible other possible imaginaries and therefore different realities for coming into being and existing in the world (ibid.). The piece, therefore, proposes the oxen’s “right to look”, that is, a “claim [to] autonomy, not individualism or voyeurism, but the claim to a political subjectivity and collectivity” (ibid., p. 1). The countervisuality that is enacted by the piece reframes the very concept of the human by raising the ox to the position of a seeing and knowable being capable of becoming one with others collectively and politically.

22 The notion of the human advanced by the installation does not, however, take as its point of departure the notion of a liberal subject but calls upon the Andean idea of equivalence, which ultimately underscores the duty of all entities to maintain relationships of mutual respect and of reciprocity (

Van Kessel and Barrios 1997, pp. 19–22;

Sillar 2009, p. 369). Furthermore, it brings out the recognition that a decolonial approach to environmental crisis demands an epistemological transformation that integrates other-than-human subjectivities (

Sillar 2009, p. 371).

Cholango’s moving piece

¿Miran tus ojos la realidad? (Can Your Eyes See Reality? 2011,

Figure 3) also reflects the concern with reality that he raises as part of his critique of colonial knowing. Evoking Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the piece casts shadows of moving creatures onto the wall as a metaphor for the removal of reality through the illusion of its representation (

Plato 2017). While the work appears to be a simple installation, technologically speaking, the question of reality and its representation gets at the heart of his interest in the idea of truth. In posing the question “Can your eyes see reality?”, Cholango asks if they can see truth, that is, the essence of creatures and not simply the illusion of their appearance. Confronting the viewer with shadows—which, according to Plato, are the form of representation furthest removed from reality—the installation forces us to determine the creatures’ nature given that these are amorphous but animal-like figures (

Figure 4). By purposefully displaying the contours of an uncertain organism while simultaneously posing the question of reality, the artist presents us, on the one hand, with the impossibility of scientifically knowing the nature of the organism (understood here as objectivity, truth, and universality) and, on the other, with a denial of its representation. To this, Ronaldo Vázquez explains that the Andean principle of relationality “implies a way of being in the world that does not follow the modern mode of appropriation and representation. […] It is not a mode in which the human becomes the center and the locus of explanation of the real” (

Vázquez 2012, p. 4). This description is useful in considering how, according to indigenous social philosophies, the way of reconstituting oneself within nature relationally underscores from the outset a rejection of modernity’s dichotomous thinking and its attempts to define the natural world through representation. As we are unable to fix the creatures in place, the artist invites us to come to

know them through a sort of relational seeing that recognizes them as agents capable of affecting the world. Thus, in underlining relationality as a paradigm that is inherently nonhuman-centric, we can also conceive of it as a method for knowing the world (

Kohn 2013, pp. 1–26).

23 While emphasizing the very notion of visuality that has also been offered by Mirzoeff, Cholango’s critique of technology’s complicity with colonialism does not refer simply to an idea of the technological as a mechanical entity. Rather, it contests the understanding of technology following Martin Heidegger. In his acclaimed book The Question Concerning Technology, Heidegger advances the notion that the essence of modern technology is not something technological per se but refers instead to a mode of seeing and knowing the world—one that has revealing as its purpose, as he explains:

What has the essence of technology to do with revealing? The answer: everything. For every bringing-forth is grounded in revealing. Bringing-forth, indeed gathers within itself the four modes of occasioning—causality—and rules them throughout. Within its domain belong end and means, belong instrumentality. Instrumentality is considered to be the fundamental characteristic of technology. […] Technology is therefore no mere means. Technology is a way of revealing. If we give heed to this, then another whole realm for the essence of technology will open itself up to us. It is the realm of revealing, i.e., of truth.

It is in this succinct explanation that Heidegger proposes that technology is the means (via instrumentality and apparatus) both of knowing and of revealing knowledge. Moreover, he clarifies that the rules set out by modern technology are also attuned to the very logic of capitalism, because unlocking, transforming, storing, and distributing are all forms of revealing. In that sense, the perception that technology is both the apparatus and the knowledge that perpetually extracts and controls an inexhaustible standing reserve of natural resources ultimately has served as the source of humans’ impetus for exploiting the environment since the sixteenth century (

Heidegger 1977, p. 7).

Beyond challenging the idea of technology as an apparatus designed for the use of men, as is assumed by these models, indigenous philosophical thinking advances an entirely different definition of technology. According to the Peruvian anthropologist Alexander Herrera Wassilowsky, Andean technology can be characterized as a “total social doing” (“un hecho social total”), by which he means a “complex network of social relations woven together by human communities, plants, animals, the environment, and which are rooted in history” (

Herrera Wassilowsky 2011, p. 17).

24 Not only does indigenous technology integrate nonhuman agents and local realities as vital actors in the social network of technology, but it also incorporates temporality (past, present, and future) as a defining element in the construction of knowledge. Hence Herrera Wassilowsky further clarifies the following:

Andean philosophy indicates, however, that technology is not a simple relation between a technological hardware and a cultural software, but that technology refers to a set of practices embedded in social networks woven by objects, places, and specific local epistemologies. So that technology is not only not neutral, but it is also not external to people or society—in short it proposes a sociotechnological approach instead of a technoscientific approach.

(ibid., p. 17)

In other words, Andean technology goes beyond the idea of technology as an external apparatus and refers instead to a logic constituted from within the social relations between human and other-than-human agents. However, as Herrera Wassilowsky further explains, the purpose of differentiating indigenous technology from modern technology is not to find some substantial difference between them, but to better understand their contextual distinctions, that is, the way that local epistemologies and their different actors (human and nonhuman, political, historical, cultural, and environmental) define technological doing and knowing (ibid., p. 20) In this sense, the complete integration of “abstract (time-based), contextual (local), and practical (mechanical) characteristics of Andean technology” can be understood in its totality as an expression of Andean identities or the way in which technology ultimately mediates the formation of intersubjectivities between human, other-than-human, environmental, and historical agents (ibid., p. 21).

3. Andean Technologies and the Embodiment of Relational Epistemologies

Cholango’s cybernetic installation titled

Cochasqui (2014,

Figure 5) is an illustrative example of how the artist makes a critical intervention into the meaning and logic of technology with Andean notions of animism, relationality, and equivalence to bring about a total social doing. The mechanical entities in

Cochasqui are not simply a way of representing these principles. Instead, I argue, they embody these qualities, confronting the viewer with their existence as hybrid creations between machine and animal.

Cochasqui is an installation of five robots suspended in the air, all of which have an upper structure that resembles an arachnid skeleton connected to feathers that move up and down, while the bottom part rotates from right to left. The asynchronous movement between up and down and right to left is indicative of the sophistication of the machine. Each robot emits a light, which they use to communicate with each other. Using sensors, the robots capture the light shining toward them as input and can subsequently change direction. Sound and colored lights are also at work in the piece, but these are preprogrammed elements.

25 As the visitor nears the cyborg creatures, he/she is to see the robots telecommunicating using sound and light. These responses are characterized in cybernetics as feedback, that is, responses in the form of light or movement that confirm that an input has been received or that communication has been established. The idea of communication, besides being a principle of cybernetics, can be thought of as provoking the dynamic that the artist is advocating for in trying to transform peoples’ relationship with the environment. This repositioning, however, is not one that is simply about stating the importance of nature and its significance in the continuation of human life but is about establishing other ways of knowing and being with and in the environment altogether.

As is true for many experiments in art and technology, especially cybernetics, these robots do not have any utilitarian function or a specific meaning; they simply embody a form of play that manifests their own technological nature. When visitors come into contact with the robots, these machines are already interacting among themselves. In that respect, the viewer is confronted immediately with the question of the installation’s behavior and function—one that is purposefully undetermined, so that upon trying to understand the machines’

raison d’être, the viewer’s assumptions about these uncanny cyborgs are quickly challenged. Cholango’s intention in using robotics relies partially on what Roy Ascott had already described in the 1960s as robotic art’s inherent interest in exploring behavior; the machine’s own capability to respond and interact, as well as its capacity to jolt and even transform people’s knowledge base and attitudes (

Ascott 2003, pp. 110–11). In the case of

Cochasqui, the nonfunctional human–machine interaction is intended to expose our own preprogrammed behaviors toward the environment and toward each other by contesting the assumptions that we often make about other-than-human entities—their essence, function, appearance, and overall behavior or intelligence. Thus, by not conforming to our imaginaries of robotics’ supposedly android capacities and appearances, which are both informed by science fiction accounts and modern technologies, the artist’s cyborgs expand our otherwise homogenous and universalizing notions of modern technology.

26 Cybernetics, moreover, is an appropriate medium to further question our notions about and relationship to the technological precisely because it subverts the representational idea of art by inciting forms of interaction, participation, and engagement that bring forth the knowledge and knowing that is produced within a total social doing. In fact, the animistic qualities of the creature-machines are evident in their capacity to reveal through their mesmerizing interaction how nonhuman persons also have sentient vitality, agency, and intent not only worthy of human attention but, more importantly, of their respect (

Sillar 2009, p. 371). Additionally, the idea of relationality is expressed in the way in which they demonstrate a capacity to communicate and hence initiate forms of nonhierarchical reciprocity (ibid.). This can be furthered underscored by turning to Claudia Pederson’s analysis of Latin American robotic art:

While taking diverse forms, these [cybernetic] practices share a common formal and conceptual point of reference in reciprocity; that is, the processes of exchange central to the operation of these works embody an alternative formation of the “political,” understood to broadly include visions of being and relating that are deeply antithetical to the dominant hierarchical thought, value, and structures.

Hence, by bringing visitors into contact with indigenous robotics, the installation exposes them to the concept of Andean technology, which is in and of itself an embodiment of relationships of solidarity with the unknowable, indeterminate, and the unrepresentable. This engagement with

Cochasqui exposes visitors to the embodiment of modes of knowing premised on relational epistemologies, which according to the anthropologist Nurit Bird-David, refer to “knowing the world by focusing primarily on relatednesses, from a related point of view, within the shifting horizons of the related viewer” (

Bird-David 1999, p. S69), that is, to modes of knowing and becoming with others that are based on partial and always shifting perspectives. Technologies (modes of knowing) that are today crucial in repositioning our relationship to the environment and even to the very environmental crisis that we are inhabiting.

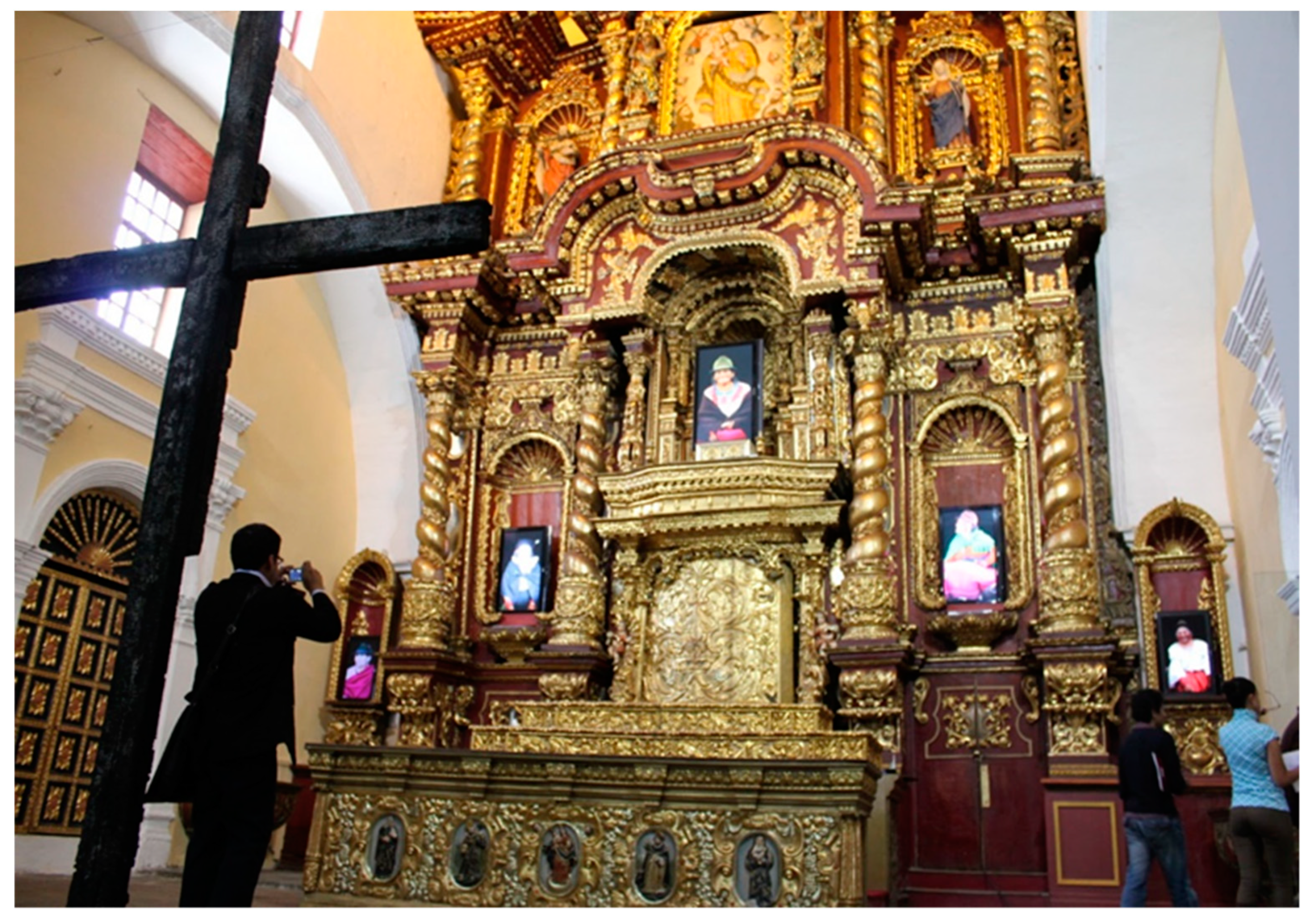

Finally, in the video-installation titled

Adorarás otros dioses delante de mí (You Will Worship Other Gods Before Me, 2011,

Figure 6), the artist’s critical intervention involves the Baroque altarpiece of the Capilla de los Ángeles in Quito (now part of the Museum of the City of Quito) with the creation of a video installation of Andean ancestors, which he locates in what is otherwise the place of Catholic saints within the altarpiece. Cholango, however, is not simply substituting the saints but, more specifically, altering the historical significance of the altarpiece as a site of religious worship. Playing the images of Kichwa ancestors in television monitors throughout the baroque structure, he allots the figures with a liveliness that contrasts the static representation of sacred sculptures. Presented at the exhibition titled

Caspicara-Cholango in 2014 in Quito (

Anonymity 2015), the appropriation of the altarpiece with five video monitors underscores Cholango’s interest in Spanish colonial art history by establishing a parallel between him and the eighteenth-century indigenous sculptor Manuel Chili Caspicara (1726–1796), who is today renowned for his sculptures in the Andean Baroque style. Altogether, the resignification of the altarpiece through the artist’s media intervention results in a neo-baroque gesture that ultimately advances a form of epistemological revindication.

Adorarás otros dioses delante de mí is an appropriation of the church as a space for worship that speaks to the syncretic manner in which Andean spirituality is often combined with Catholic religiosity. Accounting for the sacred context of the piece, Cholango stated during an interview in 2006 with the Ecuadorian newspaper

El Comercio, “Yes, all my work is both political and religious. I always include certain aspects of my indigenous culture and ancestral heritage as a form of political resistance” (

El Comercio 2006;

Reus 2011). Following this quote and considering the integration of video in the piece, Cholango demonstrates how Andean epistemology constitutes a form of knowing that does not separate secular beliefs from religious views. In fact, Axel Nielsen, Carlos Angiorama, and Florencia Ávila further explain that:

The current interest in non-human agencies has a lot in common with what is usually encompassed under the category of religion, particularly if we embrace [Robin] Horton’s definition of this concept as “an extension of social relationships beyond the confines of purely human society,” to include “personified” non-humans that have an influence on people’s lives and destiny. Building on this idea and on the tradition that conceives of ritual as religious practice, we can tentatively define ritual as social action that addresses non-human agents who have a significant influence on human fate [my emphasis].

Thus, forms of ritual and religious practice are often the sites where the animistic world is invoked to actively affect human life and destiny (future) and where ancestors’ capacity to provide a continuation of the past into the present is more visibly brought to bear. As the definition of Andean technology further stipulates, temporality is an animate entity fundamentally capable of shaping the intersubjectivities of those who constitute the total social doing, and that is why, in calling to decolonize technology, Cholango is simultaneously redefining our conception of time. The moving digital images of ancestors that Cholango placed in the altarpiece do not, however, simply replace Catholic icons as figures of worship; instead, their presence validates their role as agents of memory that can help shape the identity and destiny of humans as well as other-than-human entities. In fact, the type of relationality that is practiced in ritual, according to Ronaldo Vázquez, is “a verbality between present and past, we would say, between what is present and what is absent” (

Vázquez 2012, p. 8). So that to speak of ancestors, in that sense, does not refer to something that has passed and no longer exists, but to engage relationally in the dialectic between the ones who are present and those that are absent, and between past (memory) and the present (

Gagne 2006, p. 256).

I bring Cholango’s religious intentions with his artwork into the discussion, because with his stated intent to “poeticize technology”, he invokes the relationship between art (teche) and technology, that is,

poesis, or the creative act that is embedded both in the concept of technology and art as two modes of materializing the divine as a form of knowing (

Heidegger 1977, p. 18). Cholango’s incorporation of Andean social principles, in this sense, further legitimates the past and the divine as forms of objective knowledge.

27 For by appealing to

poesis, the artist makes reference to a type of creation that substantiates an ethics of making that is not only poetic, but also political, as it contests the belief that scientific thinking is the only valid mode of revealing knowledge. Considering the differences between Andean knowledge and modern scientific thinking as presented in

Adorarás otros dioses delante de mí, it is productive to think about how the Colombian anthropologist Arturo Escobar articulated the relationship between what he calls the

Pachamámicos and the

Modérnicos (

Escobar 2010). As Escobar suggests, one of the main reasons why Pachamamic knowledge (Andean social philosophies) and modern knowledge often seem irreconcilable is because scientific thinking insists on secularity—it denies that god(s) and spirituality (including the belief in ancestors) have any role in the production of objective knowledge (ibid.). One could even say that modern science and Andean social philosophies prioritize two distinct forms of knowing, which is why Escobar further claims that, in the current socio-environmental crisis produced by market forces and capitalist exploitation, modern knowledge is incapable of solving these modern problems for which Andean social philosophies can in fact provide solutions (

Bird-David 1999, pp. S69–S71). And, they can provide solutions precisely because this is a crisis of modes of knowing, marked by our current inability to articulate new ways of world making. Escobar clarifies this when he states that “the crisis is a real conjunctural moment in the reconstruction of the connection between truth and reality, between words and things, one that demands new practices of seeing, knowing and being” (

Escobar 1995, p. 223;

Warwick 2002, p. 653). Those practices are essential to the larger notion of indigenous futures, which entail entirely new ways of world making. This distinction between scientific and Andean thinking does not, however, attempt to render modern knowledge irrelevant or imply that these two are irreconcilable.

28 They are instead complementary, if we understand that

Pachamamismo creates an imaginary for multiple worlds, where a plurality of knowledges and modes of knowing are respected and legitimated, moving away from the ontological dualism set out by modern Cartesian thinking and its claims to universal truth (

Escobar 2003;

Tapia Mealla 2009).

4. Indigenous Futures or How to Poeticize Technology

Although the concept of indigenous futures does not refer to a specific idea or vision of the future, the future that is implied in this proposition has as its horizon the repositioning of our ways of relating to the environment and to each other.

29 In facing our current climate catastrophe, Cholango’s impetus to “poeticize technology”, in accordance with contemporary indigenous ecocriticism, stems from an understanding of the destruction of the environment as one of the major systems that uphold colonial domination. In that sense, to “poeticize technology” means to decolonize the logic of modern technology, which Heidegger explained abides by our capitalist instrumentalization of external apparatuses for the continued exploitation of the earth and other human beings (

Heidegger 1977, p. 5). In that regard, embedding indigenous social principles into the making of new media art installations and robotics creates other epistemologies and, therefore, other ontologies besides those promulgated by Western scientific thinking. The concept of Andean technology as a “total social doing”, moreover, contrasts with Heidegger’s definition of technology, as the former relies on collective, sustainable, intersubjective, and interdependent webs of knowledges and modes of knowing. This is a conception of technology that, furthermore, directly addresses the environmental crisis that we are experiencing today and which, in the face of end-of-the-world scenarios, can help us produce once again the possibility of the future.

Seeking not only the preservation of our multiple and heterogeneous ecosystems, but also the deterrence of growing climate violence, the notion of futurity that has been suggested here is also closely intertwined with the past and our collective memories, as these are vital actors in the total social doing. That is, as stipulated by Kate Morris and Bill Anthes in their introduction to the aforementioned issue of the

Art Journal, this is a notion of the horizon that simultaneously acknowledges and celebrates the resilience, resistance, and thriving capacities of indigenous peoples in fighting against the oppression, exploitation, and epistemic violence that have been perpetuated for over five hundred years (

Morris and Anthes 2017). In that sense, the quincentenary of the discovery of America in 1992 is crucial in understanding the discursive and ideological context in which Cholango’s art practice develops. While not all of Cholango’s installations are “technological”, they are all, nevertheless, attempts to decolonize technology. That is, by expanding our notion of modern technology, the artist subverts the logics of representation, appropriation, and exploitation, so that instead of being complicit with colonization, technology can contribute to the construction of alternative ways of world making.