Abstract

Self-reflexivity is a significant characteristic of Austro-German cinema during the early sound film period, particular in films that revolve around musical topics. Many examples of self-reflexive cinematic instances are connected to music in one way or another. The various ways in which music is integrated in films can produce instances of intertextuality, inter- and transmediality, and self-referentiality. However, instead of relying solely on the analysis of the films in order to interrogate the conception of such scenes, this article examines several screenplays. They include musical instructions and motivations for diegetic musical performances. However, not only music itself, but also music as a subject matter can be found in these screenplays, as part of the dialogue or instructions for the mis-en-scène. The work of Austrian screenwriter and director Walter Reisch (1903–1983) will serve as a case study to discuss various forms of self-reflexivity in the context of genre studies, screenwriting studies and the early sound film. Different forms and categories of self-referential uses of music in Reisch’s work will be examined and contextualized within early sound cinema in Austria and Germany in the 1930s. The results of this investigation suggest that Reisch’s early screenplays demonstrate that the amount of self-reflexivity in early Austro-German music films is closely connected to music. Self-referential devices were closely connected to generic conventions during the formative years and particularly highlight characteristics of Reisch’s writing style. The relatively early emergence of self-reflexive and “self-conscious” moments of music in film already during the silent period provides a perfect starting point to advance discussions about the musical discourse in film, as well as the role and functions of screenplays and screenwriters in this context.

1. Introduction: Self-Reflexivity in Film and Music

Self-reflexivity in film music is a multi-faceted topic that can be tackled from various perspectives. While the concepts and methods of self-reference and self-reflection, of intertextuality and intermediality, have been discussed extensively within film and media studies (see Stam 1992), less literature on these issues can be found in musicology (see Steinbeck 2011; Michaelsen 2015 or Bernhardt 2018). Self-reflexivity in film music is mostly addressed with regards to the film musical (Feuer 1995) and discussions about the diegetical status of music implicitly tackle the issue (see Biancorosso 2009; Heldt 2013; Stilwell 2007; Smith 1998; Winters 2010).

Film music, however, is a field that requires analysis and discussions that go beyond musicological methods and theories. Music in film cannot be analyzed simply as music, that is, on a purely formal-aesthetical level, but it needs to be understood in relation to the film’s visuals and narrative. In this article we use self-reference and self-reflection in film music as referencing music in film, thus distinguishing two kinds of self-reflexivity:

- Music as sonic feature: music that refers to another narrative, text or medium (e.g., musical performances, lyrics).

- Music as subject matter or narrative element: references about music, made mostly within the dialogue or less frequently in the mis-en-scène.

2. Walter Reisch: The Musical Writer

In this article we will use screenplays by Walter Reisch as our case study. Austrian screenwriter Walter Reisch (1903–1983) already had a prolific career in Austro-German silent and early sound cinema1 before he was forced to immigrate to the United States in 1937. He had started to write for film as a young student in Vienna during the 1920s. In Hollywood he wrote, among others, a biopic of Johann Strauss (The Great Waltz, 1938) as well as Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotschka (1939, co-written with Melchior Lengyel, Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder). Among his Austrian and German films are Zwei Herzen im ¾ Takt (1930), Das Lied ist aus (1930), F.P. 1 antwortet nicht (1932), Leise flehen meine Lieder (1933), Maskerade (1934), Episode (1935), and Silhouetten (1936). In 1953 Walter Reisch won an Academy Award (with Charles Brackett and Richard L. Breen) for the screenplay for Titanic; a feat that few Austrians achieved.

Already his early work for Austrian silent cinema contains an astonishingly great number of instructions for the use of music and for the structuring of musical moments—a tendency that increased even more in his sound films. The way Reisch integrated music in his stories is characterized by a high degree of self-reflexivity, self-consciousness and intertextuality. The examples below shall demonstrate how Reisch used different devices for this purpose.

The analysis of Reisch’s work during what can in part still be considered the transitional phase between silent and sound cinema illustrates some of the ways the nascent sound film dealt with the new technical possibilities, and over time influenced and helped establish certain conventions of the American film musical, a genre in which elements such as direct audience address, surrealistic spectacle, “impossible” temporal and spatial structures and frequent instances of self-reflexivity thrived. Reisch’s screenplays not only include myriad musical performances, but they also frequently engage with music as a subject matter, with several important characters pursuing or carrying out musical professions. Music becomes a key ingredient of the narrative, leading to the development of specific audio-visual devices already in the screenplay. The Austro-German music film and its numerous sub-genres can be read as precursors to this classical Hollywood genre in many entwined ways, one of which are these instances of self-reflexivity, as we set out to show.

This article is also part of a research project that examines the screenwriting of musical numbers, focusing mostly on the screenplays by Reisch. Self-reflexivity is an important aspect of a screenwriter’s dealing with music in his scripts. The main sources for this article are thus Reisch’s screenplays in their available versions, compared with the films that emerged from them. Detailed readings of the screenplays contextualized within the production process allow us to reconstruct the creative problems filmmakers were confronted with and trace the ways they solved them. Focusing on these screenplays brings forth insights that would have remained hidden if looking at the filmic texts only, in particular when it comes to the intentions and the self-consciousness of screenwriters in connection with the cultural background they represent.

3. A Question of Genre: Music Film and Film Musical

The film musical, based upon musical numbers, is considered as a genre with a high amount of self-reflexivity (see Feuer 1995). Rick Altman defines the American film musical as a narrative genre of feature length, in which a romantic couple—whose gender dualism needs to be resolved during the course of the plot—is at the center of the film. A film musical combines rhythmic movement with realism in the acting and features a mix of diegetic music and dialogue on the soundtrack (see Altman 1987, p. 102ff). However, musical numbers are able to change the mode of representation as well as the overall aesthetic structure of a film in any genre, as recent literature has provided ample evidence for (Herzog 2010).

Most film histories state that the film musical as a genre started in the late 1920s with the transition to sound. Such historiographies clearly focus on the North American context. In many European films, especially in Austria and Germany, musical numbers and “music films”, which anticipated various characteristic elements of the popular genre, can be detected throughout the silent era (Tieber 2016). The shift to sound cinema can thus be regarded as a logical step to further develop and refine the creative solutions of combining music and film that originated in the silent period.

Almost every national cinema has its own history and several variations of the film musical. In the Austro-German case, film scholar Michael Wedel has defined the “Musikfilm”—referring to Altman—as: “a narrative genre with a minimum length of an hour, within which the repeated musical numbers with diegetically motivated singing establish a significant relation between filmic narration and musical discourse” (Wedel 2007, p. 23, our translation). Since the material scope of this examination is defined by a common screenwriter, the film sample includes both “music films”, in accordance with Wedel’s definition and films that do not fall in this category, yet contain a significant amount of music (as sonic feature or subject matter). The Austro-German music film, broadly defined, flourished fully in the 1930s after Reisch helped establish it, though not all of his German language screenplays were written for this genre.

A significant amount of research has been conducted about early Austrian and German sound music films (see Uhlenbrok 1998; Hagener and Hans 1999; Elsaesser 2000; Wedel 2007) and most scholars acknowledge self-reflexivity as an important characteristic of the genre. However, hardly any research has focused on screenplays in this regard, not in the Austro-German case, nor for Hollywood films. Screenplay analysis offers the possibility to analyze and interpret the mode of production of these films, the integration of its diverse and (sometimes) contradicting elements, the construction of musical numbers and the use of music in general. Considered one of the founders of the popular genre of the Viennese film, as well as having directed some films himself, Walter Reisch is one of the few screenwriters mentioned in the literature on the genre. However, very few studies address his screenplays. The reasons for the amount of self-reflexivity in the screenplays by Reisch, which represent just a small portion of the total cases that can be found in Austro-German early sound cinema, are manifold. One important reason is genre: self-reflexivity is a significant characteristic of films featuring musical performances or music as a subject matter; as is evident when looking at the American film musical and their common precursor, the operetta. The operetta has always displayed self-referentiality and self-reflection in lyrics, music, staging etc. (Klotz 1991, p. 130ff). In Walter Reisch’s screenplays, as well as in the Austro-German music film in general, operetta is a very prominent theme and important influence, either through explicit adaptations or through implied references. The Wien Film—an operetta-like genre that constructs a nostalgic, utopian Vienna, ripe with reminiscences of “Wine, Women and Song”—can be considered another form of the operetta after the musical theater genre’s “Golden” and “Silver” eras had passed.

4. Intermediality: Music Historiography in Film

Screenplays—and related materials such as story conference minutes, correspondences etc.—document the stages of development of a story at a specific point in the production process. Ian Macdonald coined the term “screen idea work group” (Macdonald 2013, p. 72ff) to refer to the group that develops a screen idea into a film. Depending on the mode of production, this group can consist of only one person, or of a larger collective including several screenwriters, producers, the director and others. However, it remains the task of the screenwriter to put the results on paper (see also Price 2013, p. 132ff). The integration of musical numbers into a film’s narrative is thus first and foremost the job of the screenwriter, not of the composer, and only in part that of the director. Thus, the way in which musical numbers are incorporated into a film is written down in the screenplay.

In Reisch’s screenplays musical numbers were not only mentioned but also described in great detail. Reisch is not the only screenwriter who had an interest in creating musical numbers. The number of screenplays containing the place holder “insert musical number” is relatively small in Austro-German screenplays and is instead more frequently found in Hollywood screenplays.

One of the tasks a screenwriter has to cope with when incorporating musical numbers into a story is to combine often surreal music scenes with an otherwise realistic narration. One way to address this issue—famously employed in many early film musicals—was to make a song an important part of the narration, which means that the song’s rendition becomes part of the plot.

In The Prince of Arcadia (Der Prinz von Arkadien, AT 1932), a “fairytale musical” as per Altman’s definition of the subgenre (Altman 1987, p. 129ff), the song that gives the film its title is taken from Jacques Offenbach’s operetta “Orfée aux Enfers” (“Orpheus in the Underworld”, premiered 1858). The “screen idea” (Macdonald 2013) for the entire film is rooted in another medium and can be boiled down to the question: what if Offenbach’s prince of Arcadia was living in the present? Offenbach’s famous aria is used both as the hymn of the film’s fictional nation as well as a subversive and satirical song repeated throughout the film. It is this kind of tongue-in-cheek humor and the repeated direct audience address—in the tradition of contemporary operetta performance practices—that characterizes not only Reisch’s own writing, but is emblematic of the German-Austrian music film before 1933. In many respects, self-reflexive devices like these derive from the operetta tradition that had been thriving on many Austrian and German theatre stages only decades prior.

The introduction of the song is noted in the screenplay as follows:

- 5c.)

- And he starts to sing:

- “Once I was Prince of Arcadia…

- I lived in wealth, glamour and splendour!”

- Expertly he adds:

- “Lehár …!”

- His highness enters the frame,

- He smiles, says hastily, while tapping the minister of

- justice on the shoulder:

- “Correct…

- Offenbach!”2

—Reisch (1932, p. 32)

Recreating the original format of the screenplay in this quotation renders an impression of the two-column screenplay Reisch used in this case. The (visual) action is described in the left column, while the sound elements (dialogue, singing, music, sound effects) are moved to the right side. This “European” screenplay format differs from the one-column format of the master scene script that became the standard in Hollywood in the early 1930s. Some screenplays for Hollywood musicals adopted the two-column format for scripting musical numbers (see Price 2013, p. 152; Scholz 2016, pp. 82, 344; Tieber 2008, p. 125).

This example works on both levels of self-reflexivity mentioned at the outset of this article: (1) the aria is used to build a closer connection to Offenbach’s famous operetta (music as a sonic feature), and (2) the operetta and its composer are mentioned explicitly, intended to characterize the prince as a well-educated man (music as subject matter).

Reisch included references to known composers multiple times in his screenplays, both by using or paraphrasing their music as well as through dialogue. The above-mentioned Prince of Arcadia starts with music that quotes Richard Wagner: “Music starts. One plays in a jazzed up mode. ‘In fernem Land, unnahbar Euren Schritten’” (Reisch 1932, p. 7). The musical introduction of the film presents Wagner’s famous aria from Lohengrin in a rather conventional way, followed by jazz-like music.

Another of Reisch’s films takes place in the highbrow setting of an opera house: Fire in the Opera House (Brand in der Oper, DE 1930). The film depicts some opera scenes, but none of them long enough to count as a proper attraction in itself or as narratively significant. The film is not a music film according to Wedel’s definition, but it is set in a musically determined location.

The film begins with a prologue intended to recall Goethe’s Faust (Reisch 1930a, p. 7). To achieve this association, Reisch opens the film with a conversation between an opera director, a financial director and a conductor who discuss their next production. The financial director, who resembles Jacques Offenbach, proposes an operetta such as the “Czardasfürstin” (ibid.). The conductor on the other hand, whose facial scar indicates his membership in a German-nationalist fraternity, wants to perform Richard Wagner’s “Götterdämmerung” (ibid.). The financial director wants “little girls” on stage—promoting an apparent anti-Semitic stereotype—while the conductor prefers grand opera. Recalling the gender dualism structure of film musicals according to Altman (1987, p. 28ff), Reisch creates a cultural dualism between a Jewish and a German nationalist character—a problematic and all too obvious opposition that is unexpectedly resolved by suggesting the performance of Offenbach’s “Tales of Hoffmann”. Offenbach’s opera is considered a compromise between a popular operetta and the heavy German opera. According to the director, “Tales of Hoffmann” fulfills both demands: little girls and serious opera (Reisch 1930a, p. 9). “Little girls” were a beloved trait of the film musical at least until Gigi (USA 1957) and its famous opening song (“Thank heaven for little girls” by Lerner and Loewe)—an element of popular entertainment that has since become awkward, to say the least.

Such references to famous classical composers can be found in many of Reisch’s films, as well as in other music films of the time, and they clearly serve the purpose of cultural valorization of cinematic entertainment, ultimately aimed at attracting a wider and bourgeois audience.

Both The Prince of Arcadia and Fire in the Opera House reference the operatic world clearly within the film’s diegeses. However, there are some significant differences: in the former, the source of the film’s title and theme song is mentioned explicitly, guiding the audience’s attention towards an external creative text that is used within the film in various ways. Fire in the Opera House, on the other hand, uses cultural tastes and preferences to characterize its figures. The references remain on the level of the diegesis. The dualism between serious opera and popular operetta is addressed in several of Reisch’s screenplays, both in his German-Austrian films of the 1920s and 1930s, as well as in his American film musicals. Drawing on the opposition between (European) elitist art forms (opera, ballet, classical music) and (American) mass-produced entertainment lies at the core of many film musicals (Feuer 1982). If the “myth of entertainment”—the demystification and remythicization of the production of entertainment—is one of the essential characteristics of the film musical, as Jane Feuer (1995, p. 443) suggests then entertainment itself is negotiated within the discourse of these films.

What unites these examples across genre borders is Reisch’s affinity to use musical references and to address musical tastes in his screenplays. The amount and level of these references is determined by the genre conventions and the audience’s expectations towards the amount of realism in their modes of representation.

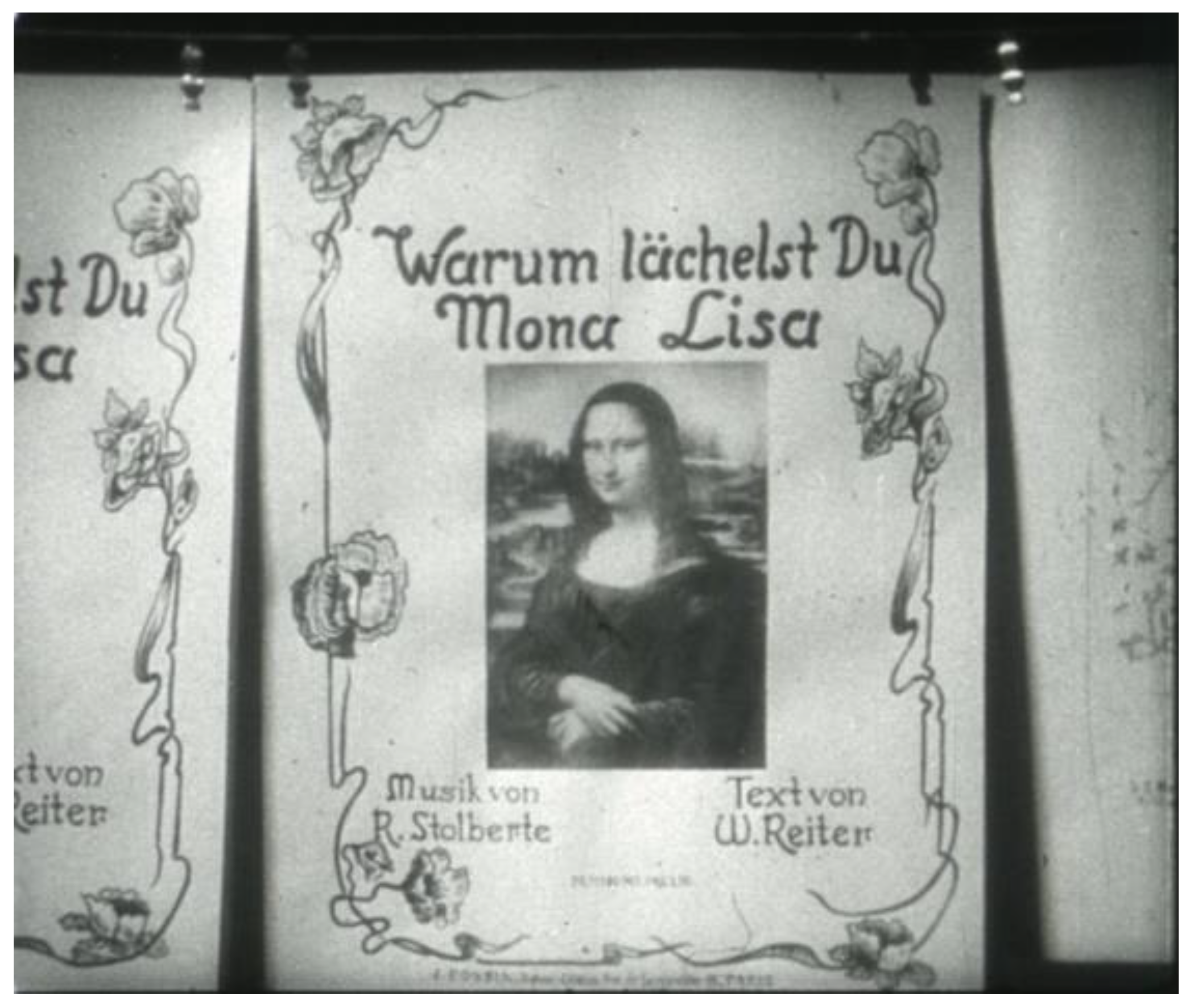

In The Theft of the Mona Lisa (Der Raub der Mona Lisa, DE, Reisch 1931) the names of two of the film’s creators are seen on screen in a brief comedic cameo: two musicians are sitting in a coffee house, reading in the newspaper that the famous painting of the Mona Lisa was stolen. One writes on a piece of paper: “Why are you smiling, Mona Lisa?” as a song lyric. The other man begins to write a melody above the sentence and the next shot shows the illustrated cover page of that very song with an image of the painting and the following credits: “Music by R. Stolberte/Lyrics by W. Reiter”—an obvious reference to lyricist Walter Reisch and composer Robert Stolz (Figure 1). Different musicians on various instruments—including a couple of songbirds sitting on a wire for the song’s finale—are then shown as they perform the song which is used repeatedly throughout the film.

Figure 1.

The insert shows the composition “Warum lächelst du Mona Lisa” with “Music by R. Stolberte/Lyrics by W. Reiter” (film still, Filmarchiv Austria).

In a later scene, Willi Forst’s character tries to escape from the authorities by hiding in a church, in which he nevertheless gets arrested. We hear Verdi’s “Messa da Requiem” and it remains ambiguous as to whether it is diegetic music played in the church or not (no musicians are seen). The music continues to the famous and dramatic ‘Dies Irae’, which perfectly fits the dramatic situation, thus functioning as conventional extra-diegetic film music.

The songwriting duo Reisch/Stolz was fairly well known and their songs became popular beyond the films for which they were written. Some of Reisch’s screenplays include the complete lyrics of a given song, others only the first line. But as someone who wrote most of the lyrics for the songs in his films himself, his collaboration with Stolz was very close compared to those of many other screenwriters (see also Kasten 2004, p. 85ff).

To hint at or refer to filmmakers within their very own films is a form of reflexivity that is not used as frequently as others at the time. It connects the fictional world with the real world and ties together films by the same writers, directors or stars.

5. Intermediality: Cinema in Film

In one of his most typical screenplays, The Song is Ended (Das Lied ist aus, DE 1930), Reisch uses pre-existing songs about film and even writes songs that explicitly mention the new medium of sound film that is taking the entertainment industry by storm in the early 1930s in Germany.

Thomas Elsaesser calls The Song is Ended a “comedy without a happy ending. Instead it is full of world-weary resignation that was to become habitual in the Wienfilm” (Elsaesser 2000, p. 337, emphasis in the original). The Wienfilm, or Wiener Film, is a subgenre described by Elsaesser as “a genre of erotic melodrama in operetta night-life settings, narrated in a tone of resigned irony” (ibid., p. 333). Reisch is generally considered as one of the co-founders of the Wiener Film, together with actor-director Willi Forst. Although The Song is Ended takes place in an operetta theater, the film is not an operetta film.

At the very beginning of the film the song “You are my Greta Garbo” is performed by a small orchestra in a restaurant. The song, written by Reisch and Stolz, is played in an instrumental version, making the reference a little subtler. The song is an homage to the Swedish film star, thus establishing an intertextual connection from song to film to star. The same song is furthermore featured in the film A Tango For You (Ein Tango für Dich, DE 1930), also written by Reisch, with another intertextual reference (Reisch 1930e, p. 64).

Yet a different song performed in the film addresses the sound film itself:

- Scene 48

- Love is like a talking picture

- With many twists

- During its course

- First one sighs “Oh” and “Ah”

- Then comes the big fight

- But little by little, one grows weak again.

- Love is like a talking picture

- The main characters are you and I.3

—Reisch (1930b, p. 150)

The song is not only about the very medium in which it is presented, it also lays bare its inner mechanism and conventions, demystifying the production process in an ironic way and thereby displaying an unusually high level of self-consciousness within a more or less simple song.

Another film that includes references to cinema is Episode (AT 1935). Although it includes a couple of songs, it is not a music film as per Wedel’s definition. Reisch incorporated an explicit nod to silent cinema—the film takes place in 1922—with a scene that satirizes the musical conventions of silent film accompaniment. Instead of an entire orchestra, only three musicians are seen and heard at a silent film presentation: a violinist, a cellist and a pianist. They are accompanying a romantic film scene:

- 278./Medium Long Shot

- On the screen a big love scene

- Between the Maharadscha and

- His favourite wife—kiss—

- Happy—End—

- Accompanied by a sobbing violin solo.4

—Reisch (1935, p. 210)

The film shows a scene in a cinema, thereby already shifting the attention from the narration to the medium itself, from content to form, and at the same time it is parodying and satirizing the way music was used in silent cinema. Music becomes a means to poke fun at a specific, conventionalized form of musical accompaniment. What stands out here is Reisch’s focus on the music as one of the major characteristics of silent cinema. The screenplay and the film use the scene to illustrate its historical setting and background; contrasting the actual film to the one shown from the silent era and simultaneously hinting at cinema itself as a constructed product of entertainment.

Another example of referencing another expressive art form in order to direct the focus to the medium of cinema itself is the silhouette theater scene in Silhouetten (AT, Reisch 1936). The sequence is introduced with the intertitle “Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata”. What follows is a visualization and narrativization of Beethoven’s music with the means of a silhouette theatre. The shadow play scene recalls silent cinema in many respects and most famously resembles Lotte Reininger’s silhouette films.5

A similar scene can be found in the already mentioned The Song is Ended, in which Willi Forst performs a private puppet theatre show for his love interest. The remarkable point here is not just the self-reference of the new dramatic medium through the older one, but the musical specifics of this little performance. The play that is performed is called “Grosse Ausstattungsoperette in mehreren Akten und einem Bild” (Reisch 1930b, p. 115), a “large spectacle operetta in multiple acts and one scene”. The short operetta consists mostly of arias and includes musical instructions such as “grand musical illustration, full of power and drama” (ibid., p. 82). The play mirrors the situation of the two main characters with switched gender roles. The mock operetta represents the differences as well as the influence of this musical genre on the early sound film, at least on those genres that are more or less defined by their relation to musical numbers.

Again, the reference to another medium functions by mirroring the very medium at hand and its comparable apparatus, especially its use of music and the way it synchronizes music and image. The very stylized medium of the silhouette theatre lays bare the circumstance that it is created and crafted with a purpose. The illusionist purpose of mainstream cinema is again contrasted by inter-medial and self-reflexive devices.

6. The Myth of the Audience Invented: The Audience as Performer

Diegetic audiences are a crucial element of the film musical (Feuer 1982, p. 23ff), they guide and shape the expected reactions of the real audience. Usually the diegetic audience is used as an intermediary between the performers and us, the real audience. But in Reisch’s “musical comedy” (“musikalisches Lustspiel”) (Reisch 1930c, p. 1) A Gentleman to Order (Ein Herr auf Bestellung, DE 1930) we find the rare case of an audience as performer. The public lecture of a scholar who stammers is introduced with a scene that shows the waiting audience. All of a sudden, the audience starts to sing a “jazz song”:

- We are the audience

- The big audience

- We want amusement

- For our money!6

—Reisch (1930c, p. 47)

The number is addressed directly to the camera and is choreographed in a comedic way. As Feuer (1982, p. 35) notes about the use of direct address in the film musical: “Musical entertainment concentrates on breaking down any perceived distance between performer and audience”. In this scene the (diegetic) audience is not watching a performance but instead takes over the role of the performer. The audience within the film addresses the real audience in the cinema directly. The number is performed straight to the camera. The lyrics emphasize this explicit reflection of the role of the audience while the diegetic audience is totally aware of its role and function. Reisch is of course parodying a certain kind of bourgeois audience and specific conventions of entertainment. The scene might have been motivated by the need to add a funny musical number, but even today it works as a radical disruption of the film’s narrative flow and as a sort of disillusionment, lifting the already high degree of self-reflexivity to a new level.

Considering the MGM musical and the “myth of the audience”, Feuer (1995, p. 453) suggests that “the audience participates in the creation of musical entertainment”. In this case, at least the diegetic audience does indeed participate in the creation of a musical number.

7. Self-Reflecting the Media

Numerous examples in Reisch’s screenplays reflect upon the medium of cinema. One of the most crucial questions when dealing with musical numbers in films, the relation between musical attraction and narration, is explicitly addressed by two characters in Two Hearts in Waltz Time (Zwei Herzen im ¾ Takt, DE 1930), an operetta film that was adapted for the stage only three years after the film’s release. The director of an operetta theatre and one of his librettists discuss an upcoming production:

- Director: “But the plot is of minor importance,

- The main thing is the next song—”

- Nicky: (offended) “Mister Director, the plot is of equal importance—

- because it gives the songs their human basis—”

- Director: “Leave me alone with your basis—”7

—Reisch (1930d, p. 40)

The scene demonstrates not only Reisch’s own position, which might be more aligned with that of librettist Nicky, but it also shows that each character clearly defends their own interests. The director wants to find success with the public while the librettist emphasizes artistic motivation and humanity. Ultimately, such scenes highlight that the final result of an artistic production, be it a screenplay, a film or an operetta, is negotiated in consideration of creative and commercial arguments, and discussed by people working in a hierarchical system. This apt image for the process of screenplay development is varied in other films, and it is mostly used in the context of musical theatre, such as in Fire in the Opera House.

Early in the film, the two librettists—brothers named Vicky and Nicky Mahler (Willi Forst and Oskar Karlsweis)—have a fight leading both to retreat to their respective rooms. The following “dialogue” then plays out by using single lines from famous arias and folk songs.

- 11th Scene

- Vicky’s room

- Vicky paces around outraged. It becomes clear that he is sorry for having offended his brother. Unhappy about the situation, he looks at the door repeatedly to see if his brother comes in.

- He heads for the closet, loosens his tie, ties another one, looks at the door again. Suddenly, he has an idea. He quickly sits down at the piano, opens it and plays loud and with heavy hands:

- “I don’t know what it means, that I am so sad”

- 12th Scene

- Nicky’s room

- Nicky (on the sofa) turns around grudgingly, leaps to his feet, and plays fiercely and commandingly on his piano:

- “Never shall you ask me”.8

—Reisch (1930d, p. 21f)

They continue to communicate in this way until they join in song for the last line of the sequence: “We want to pretend we were friends” (“Wir wollen so tun als ob wir Freunde wären”), a popular chanson by Michael Kraus. The final filmed scenes cut some of the action proposed by the screenplay and changed the order at times, but in sum, the scene is very close to Reisch’s original idea.

8. Referencing One’s Own Film

As regards these devices of self-referentiality and inter-textuality, Reisch often pointed to his own work, using various cinematic elements. For example, in two of his films he placed advertisements of his previous productions in the mise-en-scène to establish a connection. At the beginning of Silhouetten we see a poster for Episode; in Ein Tango für Dich, an advertisement for Two Hearts in Waltz Time is shown on a billboard (Reisch 1930e, p. 17). These references can also occur on a musical level: the main theme song from Episode is played by a clarinet in Silhouetten, or, as mentioned above, a song like “You are my Greta Garbo” is used in a subsequent film.

Intertextual references are relatively common in early 1930s cinema as a cheap way to advertise films and to create a “corporate design”, be it that of a film studio or a filmmaker. The intriguing fact in Reisch’s case is that such references were repeatedly made on a musical level.

9. Separating and Combining Sound and Vision

Early sound film praised the new technological possibilities. At the same time, the synchronicity between body and voice was a point that was emphasized in various, often reflexive and deconstructive ways.

The circumstance that what is heard might not be what is seen, was addressed by Reisch very early. In A Gentleman to Order from 1930 the whole plot is based upon the idea that a man lends another man his voice, thus synchronizing him. The gramophone at the beginning of A Tango for you gives the impression that the real singer is in the room. In Silhouetten Reisch uses again a gramophone as a diegetic source of music to accompany dramatic scenes (Figure 2). The focus on the gramophone makes the combination of sound and image visible, thus deconstructing the audio-visual setup of the scene.

Figure 2.

In Silhouetten Reisch uses a gramophone as a diegetic source of music to accompany dramatic scenes (film still, Filmarchiv Austria).

The plethora of devices Reisch used already in this small sample of films demonstrate that self-reflexive, intermedial and intertextual references were anything but unusual in German-Austrian music films of the early sound era. As we aimed to show in this article, the number of self-reflexive elements in Austro-German music films—in a broad sense—from the early sound era is astonishingly high and wide in scope. The reason for this circumstance is the film’s emphasis on music, mostly (but not limited to) diegetic music and thus musical performances.

The analyzed examples represent a reflection about the medium itself and on our role as members of the audience. Close readings of the screenplays for these films allow for a deeper understanding of the original intentions as well as the production history with its creative decisions and rejections. Wedel (2007, p. 312) sums up the “musicalization” of Austro-German genre cinema in the early sound era: “The accumulation of song performances within the narration functioned as a new definition of the acoustic effective dimension of the cinematic experience under the sign of the sound film”. Sound film was able to create a new synchronized relation between vision and sound—between body and voice—in a more effective way than silent cinema was able to achieve. Within the genre of the music film “the transition from spoken and acted scenes to musical numbers, from spoken dialogue to singing did not have to be diegetically anchored or causally motivated within the plot. Instead, the various narrative and performative levels of expression have to be integrated on the level of the production” (ibid.).

The new medium of sound film self-consciously displayed its new technical possibilities. Sound film builds the technical premises of a new relation of sound and vision; of body and voice. In the case of the early Austro-German sound film, the dominant and most popular version was to include musical numbers, which led to the development of the music film and its various subgenres (with precursors in silent cinema). Self-reflexivity (the ongoing showcase of musical numbers and moments) is part humoristic element and part advertising the new medium of sound film.

10. Conclusions: Self-Reflexivity, Music and Genre

Self-reflexivity in the realm of music in film (as opposed to film music) most often contains a reflection about the use of music in film. The circumstance that music is played, sung and/or danced (to) is made explicit, the film guides the audience’s attention towards this fact and thus exposes itself as a constructed artifact (of mass entertainment).

The analyzed devices of self-reflexivity in Austro-German films as discussed above fulfill different tasks and provoke different reactions and affects in the viewers. They are able to create a closer and more intimate relationship between a film and its audience by laying bare the construction of the film, offering a glimpse “behind the scenes”.

The amount and level of self-reflexive devices in these films depend on the specific genre and its degree of realism and verisimilitude. Nevertheless, genre is not the only criterion self-reflexivity can be connected with. Reisch’s screenplays feature self-reflexive devices across generic boundaries. Although most of his films are somehow connected with diegetic music and musical numbers can indeed be found in most of his screenplays, not all of his films can be regarded as music films in the way Wedel defines the term. Musical numbers in his films tend to be more strongly anchored in a film’s narration and are mostly motivated by diegetic musical performances (as opposed to musical numbers in which characters often sing and dance following genre conventions). In short, self-reflexivity in these films is embedded in generic conventions and in humoristic scenes and often used with a tongue-in-cheek attitude. In most cases such self-reflexive moments are—as we demonstrated—closely connected with music. The amount of self-reflexive devices in these films is thus connected to the historical and technological development of the early sound film and the conventions and the establishment of filmic genres, as well as to the cultural background and individual tastes of its screenwriter.

Reisch’s preferences and his comprehensive cultural education can be traced through all of the mentioned examples. Instead of regarding him as the “auteur”, and his creative decisions as individual proclivities, we rather regard him as a representative of a specific culture of irony, double entendre and subversive humor that can be identified in most of his screenplays.

The “staging” and production of a film project starts with the screenwriting process. Contrary to a common misconception that a screenplay contains merely plot descriptions and dialogue, we demonstrated that the “integration of narrative and performative levels of expression” already starts at this point in the filmmaking process. The self-referential devices discussed in this article can thus be read as a welcome tool to further investigate the relationship between the various levels of film production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T.; methodology, C.T.; investigation, C.T. and C.W.; resources, C.T. and C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T. and C.W.; writing—review and editing, project administration, C.T.; funding acquisition, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the FWF Project Screenwriting Musical Numbers P31488 (principle investigator: Claus Tieber).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anna K. Windisch, Kristina Höch and Gerrit Thies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Altman, Rick. 1987. The American Film Musical. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, Walter, ed. 2018. Werner Wolf: Selected Essays on Intermediality by Werner Wolf. (1992–2014). Leiden: Brill Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Biancorosso, Giorgio. 2009. The harpist in the closet: Film music as epistemological joke. Music and the Moving Image 2: 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser, Thomas. 2000. Weimar Cinema and After. Germany’s Historical Imaginary. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Feuer, Jane. 1982. The Hollywood Musical. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Feuer, Jane. 1995. The Self-Reflexive Musical and the Myth of Entertainment. In Film Genre Reader II. Edited by Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 441–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hagener, Malte, and Jens Hans, eds. 1999. Als die Filme singen lernten. Innovation und Tradition im Musikfilm 1928–1938. München: Text & Kritik. [Google Scholar]

- Held, Guido. 2013. Music and Levels of Narration. Steps across the Border. Bristol: Intellect Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, Amy. 2010. Dreams of Difference, Songs of the Same. The Musical Moment in Film. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kasten, Jürgen. 2004. Blonde Träume. Spione und andere Täuschungen. Walter Reischs frühe Tonfilm-Drehbücher. In Walter Reisch. Film schreiben. Edited by Günter Krenn. Wien: Verlag Filmarchiv Austria, pp. 83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, Volker. 1991. Operette. Porträt und Handbuch einer unerhörten Kunst. München: Piper. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Ian. 2013. Screenwriting. Poetics and the Screen Idea. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelsen, René. 2015. Der komponierte Zweifel. Robert Schumann und die Selbstreflexion in der Musik. Paderborn: Fink. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Steven. 2013. A History of the Screenplay. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Reisch, Walter. 1930a. Brand in der Oper, Deutsche Kinemathek 4.4-198329,1.

- Reisch, Walter. 1930b. Das Lied ist aus, Deutsche Kinemathek 4.4-198329,5.

- Reisch, Walter. 1930c. Ein Herr auf Bestellung, Deutsche Kinemathek 4.4-198329,2.

- Reisch, Walter. 1930d. Zwei Herzen im ¾ Takt, Filmarchiv Austria, Reisch Collection, Box 3.

- Reisch, Walter. 1930e. Ein Tango für Dich, Deutsche Kinemathek 4.4-198329,2.

- Reisch, Walter. 1931. Der Raub der Mona Lisa, The Theft of Mona Lisa. Filmarchiv Austria, Reisch Collection, Box 16.

- Reisch, Walter. 1932. Der Prinz von Arkadien, Deutsche Kinemathek 4.4-198329,20.

- Reisch, Walter. 1935. Episode, Filmarchiv Austria, Drehbuchsammlung (screenplay collection) DB 1781.

- Reisch, Walter. 1936. Silhouetten, Deutsche Kinemathek 4.4-1983/29,10.

- Scholz, Juliane. 2016. Der Drehbuchautor. USA – Deutschland Ein historischer Vergleich. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jeff. 1998. The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, Robert. 1992. Reflexivity in Film and Literature. From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbeck, Wolfram, ed. 2011. Selbstreflexion in der Musik/Wissenschaft: Referate des Kölner Symposions 2007. Kassel: Bosse. [Google Scholar]

- Stilwell, Robynn. 2007. The Fantastical Gap between Diegetic and Non-Diegetic. In Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema. Edited by Daniel Goldmark, Richard Leppert and Lawrence Kramer. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 184–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tieber, Claus. 2008. Schreiben für Hollywood. Das Drehbuch im Studiosystem. Münster: Lit Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Tieber, Claus. 2016. Silent Singing: Diegetic Songs in Austrian Silent Cinema. Immagine. Note di Storia del Cinema 14: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenbrok, Katja, ed. 1998. MusikSpektakelFilm. Musiktheater und Tanzkultur im deutschen Film 1922–1937. München: Text & Kritik. [Google Scholar]

- Wedel, Michael. 2007. Der deutsche Musikfilm. Archäologie eines Genres 1914–1945. München: Text & Kritik. [Google Scholar]

- Winters, Ben. 2010. The Non-Diegetic Fallacy: Film, Music, and Narrative Space. Music & Letters 91: 224–44. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | We are focusing on Austrian cinema in our research, but, starting in the 1920s, many Austrian filmmakers went to Berlin to produce their films due to a more solid financial situation as well as the technical advances made by the German film industry after the First World War. “Austro-German cinema” thus includes films made in Vienna and Berlin. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 | See, among others, Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed (Prince Achmed’s adventures, DE 1926). |

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).