Abstract

Stemming from Grosfoguel’s decolonial discourse, and particularly his enquiry on how to steer away from the alternative between Eurocentric universalism and third world fundamentalism in the production of knowledge, this article aims to respond to this query in relation to the field of the art produced by Latin American women artists in the past four decades. It does so by investigating the decolonial approach advanced by third world feminism (particularly scholar Chandra Talpade Mohanty) and by rescuing it from—what I reckon to be—a methodological impasse. It proposes to resolve such an issue by reclaiming transnational feminism as a way out from what I see as a fundamentalist and essentialist tactic. Following from a theoretically and methodological introduction, this essay analyzes the practice of Cuban-born artist Marta María Pérez Bravo, specifically looking at the photographic series Para Concebir (1985–1986); it proposes a decolonial reading of her work, which merges third world feminism’s nation-based approach with a transnational outlook, hence giving justice to the migration of goods, ideas, and people that Ella Shohat sees as deeply characterizing the contemporary cultural background. Finally, this article claims that Pérez Bravo’s oeuvre offers the visual articulation of a decolonial strategy, concurrently combining global with local concerns.

1.

Are we going to produce a new knowledge that repeats or reproduces the universalistic, Eurocentric, God’s eye view?

In the 2011 essay “Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political-Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking and Global Coloniality”, Ramón Grosfoguel asks himself what kind of knowledge is contemporary culture going to produce—whether or not a model of thought that reciprocates the abstract and transcendental European universalism that he sees affecting western thinking from Descartes, Kant and forward (cf. Grosfoguel 2012). He argues that such “ego-politics of knowledge”, a label, which he borrows from Walter Mignolo, is the result of the myth of self-production of truth by the isolated subject, which in turn constitutes one of the most relevant features of Eurocentered modernity (ibid., p. 89). Such mechanism, according to which an emptied subject speaks from a position of superiority and adopts the God’s eye view, is enacted by the constant persistence of the dualism colonizer/colonized and responds to what Santiago Castro-Gómez has called a ‘zero-point’ philosophy, which in turn is based on the assumption of the existence of an abstract universalism.2 Abstract universalism is rooted in Western XVI century philosophy; Grosfoguel distinguishes between universalism type 1, a ‘knowledge which is detached from all spatio-temporal determination and claims to be eternal’ and universalism type 2, a ‘subject of enunciation that is detached, emptied of body and content, and of its location within the cartography of global power, from which it produces knowledge’ (Grosfoguel 2012, p. 89). Both universalisms are constructed upon the exclusion of the other, the non-self, and therefore any global or cosmopolitan assumption risks to be based upon an imperialist/colonial epistemology, which either privileges the discourse and adopts the point of view of a particular territory or conceals who speaks and from where.

To avoid both universalisms, which are rooted in western thought and consequently lead to a colonial mind-frame, Grosfoguel advances the adoption of a de-colonial approach apt to criticize both Euro-American centric epistemologies—since European imperialism has been replaced, in the 20th century, by North American hegemonism—and third world fundamentalism. He does so by relying particularly on two bodies of knowledge, Aimé Césaire’s “other” universalism and Erinque Dussel’s transmodernity. As quoted by Grosfoguel, Césaire’s idea of the universal is that of a universal, which is filled with all particulars resulting from a ‘horizontal process of critical dialogue between people who relate to one another as equals’. Following Césaire’s footsteps, Dussel argues for ‘a multiplicity of critical, decolonizing perspectives against and beyond Eurocentered modernity, from the various epistemic locations of the colonized people of the world’, therefore proposing alternative epistemologies. By referring to both thinkers, Grosfoguel substitutes the prefix uni- with pluri-, replacing the notion of ‘universal’ with the idea of “pluriversalism” or “multiversalism” and postulates a horizontal dialectics among the so-called global south as alternative vector of knowledge production.

Such an ultimate position is similarly adopted and put forward by Nikos Papastergiadis, whose scholarship deals with the utopian and dystopian phenomena of the globalization in the contemporary world—as well as the role of the artist within this context. Papastergiadis advocates the formulation of ‘an alternative cartography for directing the flow of cultural exchange and proposes to initiate new south-south circuits which in themselves pluralize the possibilities of being global’ (Papastergiadis 2003, pp. 14–16). In his argument, he challenges an aprioristic idea of culture arguing that it never existed in a pristine or predetermined space of “splendid isolation” and therefore subsumes the formation of bodies of knowledge to a south–south stream of interactions (Ibid., p. 9).

The idea of a “global south” however—as much as the “idea” of Latin America, which Mignolo sees as shaped by ‘the colonial matrix of power’ originated in the XVI century—is a Catch-22, since it necessarily prompts a homogenized understanding of the third world, thus reenacting the third world fundamentalism that Grosfoguel attempts to avoid. Recently Papastergiadis has also argued that the idea of the global south as a ‘creative counter-point and critical partner of the North’ has now ended, noticing that it ‘was linked to the emancipatory ideology that was deeply entrenched in both Western enlightenment values and non-Western indigenous knowledge systems’ (cf. Papastergiadis 2017). He goes on explaining that ‘both traditions have been eviscerated by the triumph of neoliberalism’ and that ‘the political landscapes of the Global South and the North have been hollowed out’ (ibid.). Relatedly to Grosfoguel, Papastergiadis sees an alternative in which the old emancipatory discourse has been replaced by the coming out of ‘pluriversal cultural images of the South and of a new perspective on cross-cultural dialogue and transnational solidarity’. I shall come back on the idea of “transnationality” later, since I shall build on that a new decolonial approach to the study of Latin American women artists; now, I shall discuss the label “third World”, which so far was only briefly mentioned.

The expression “Third World” was coined by Alfred Sauvy in his 1952 article published at L’Observateur and titled ‘Three Worlds, One Planet’ and arrived on the world stage during the 1955 Bandung conference, which resulted in the creation of the non-aligned movement. Notably, since the end of the Cold War, the so-called “Third World” had shifted from signifying a political position that was neither aligned with the Capitalist West nor the Communist East, to identifying cultural and economic conditions of so-called “underdeveloped” countries. This opposition between developed and underdeveloped economic theories established a dichotomy between a hegemonic identity and alleged “inferior” cultures, while also creating a fallacious, homogenized understanding of the “Third World.” As Chandra Talpade Mohanty observes, this shift in the understanding of the term has resulted in colonization being ‘used to characterize everything from the most evident economic and political hierarchies to the production of a particular cultural discourse about what is called the Third World’, emphasizing the changes undergone by such a label (Mohanty 1984). Equating late-capitalism with postmodernism and pre-capitalism with pre-modernism, Jameson discusses of the ‘belated emergence of a kind of modernism in the modernizing Third World, at a moment when the so-called advanced countries are themselves sinking into a full postmodernity’ (Jameson 1992). This creates a discrepancy between Western “developed” countries and the third world seen as always laying behind, ‘not only economically but also culturally, condemned to a perpetual game of catch up, in which it can only repeat on another history of the “advanced” world’ (Shohat and Stam 2002). Actually, often Latin American practices, if discussed, had been compared and considered simply ‘copies of European originals, aesthetically inferior and chronologically posterior, mere latter-day echoes of pioneering European gestures’ (ibid.).

Moreover, such a misnomer like “Third World” is particularly egregious when one considers the pluralities of race, ethnicity, and gender that constitute Latin America, a region whose multiple identities and intercultural complexities are commonly analyzed within the framework of Mestizaje (miscegenation and mixing). Nevertheless, as Cuban art critic and curator Gerardo Mosquera has warned, even a notion as fluid as Mestizaje cannot escape the tendency to erase imbalances and conflicts within diverse cultural communities and, in so doing, similarly runs the risk of becoming ‘an attractive stereotype for the outside gaze’ (Mosquera 2010). Following from these premises, it becomes apparent that any study attempting to decolonize Latin America shall situate itself in-between the totalizing tendency of the “Third World”, the orientalist proclivities of mestizaje, the universalistic Anglo-eurocentrism and the homogenizing dialectic of the “Global South.”3 The task is not only to avoid to be subsumed to a hegemonic perspective, which reinforces the colonial dichotomy oppressor/oppressed but also to disrupt the idea of Latin America as a monolithic continent.4 When approaching feminism (or supposed “feminist art”) in the third world one encounters a greater challenge, since it bears a twofold colonization: patriarchal control and western supremacy. Such twofold colonization disentangles the commonalities shared by both feminist and postcolonial projects: the emancipation from patriarchy and western imperialism, respectively. Notably, women in Latin America suffer from a triple form of oppression, not only from patriarchy and western imperialism, but also from military regimes that have burdened the continent across the twentieth century.

Following from a historiographical excursus, the first part of this essay attempts to explain the theoretical problems embedded in current lines of thought regarding a universalized concept of feminism and an essentialized understanding of the notion of third world. In the second part, I shall propose to bypass what a reckon to be a theoretical impasse by examining the work of Cuban artist and photographer Marta María Pérez Bravo (b. Havana, 1959 and currently working and living in Mexico City), emphasizing its cultural specificities and reframing decolonial discourses by merging local with international narratives.

2.

The phrase Third World has its roots in the post-World War II economic policies of the United Nations, but today it is a euphemism. We use it knowing it implies people of color, non-white and, most of all, “other”. Third World women are other than the majority and the power-holding class, and we have concerns other than those of white feminists, white artists and men.Braderman (1989)

Ella Shohat argues that ‘Feminism is itself a multi-voiced arena of struggle’, a site of resistance against a male-dominated socio-economic apparatus and a patriarchal hierarchy of values. This statement could imply the understanding of women as a homogenous group on the base of gender and a shared oppressed condition. As Miwon Kwon remarks, some female artists from the sixties and the seventies have been grouped together and associated with a ‘belief in female sexuality as innate quality … produced [at a time] when women’s demands for autonomous and self-defined sexuality became a metaphor for the struggle for personal liberation.’5 Many Feminist scholars have criticized this stance as ‘essentialist’, due to the categories “feminine” and “woman” being presented as ahistorical, ‘with characteristics belonging naturally and universally to one gender’, upholding rather than challenging ‘the patriarchal hierarchies of sexual difference, which is in fact engendered by specific sociocultural conventions and ideologies’ (Kwon 1996, p. 166). In turn, this critical position—that on the base of a poststructuralist and Marxist critique defines the aforementioned varieties of feminine and woman not as biological functions but as systems of language and representation—has been accused of intellectual elitism (ibid.). Western feminism could thus be seen as dominant and colonizing, not taking into account differences of culture, race, class, religion, etc. among global women. Countering this, scholars Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Gayatri Spivak, Gloria E. Anzaldúa and Trinh T. Min-ha among others have advocated for a more extensive and comprehensive feminist analysis, one that takes into account women from postcolonial countries, that is those who are doubly colonized by both imperial and patriarchal ideologies. Feminism, they argue, is an unstable, fluid, context-related category. Notably, Anzaldúa’s scholarship acted as a turning point for third world feminism: the publication of This Bridge called my back (1981) was impossible to ignore for a U.S. audience. U.S. third world feminists asserted that feminists of color represented a “third term”, i.e., another gender outside the male and the female (cf. Moraga and Anzaldúa 1981; Anzaldúa 1987). Moraga and Anzaldúa’s book, together with other coeval publications, argued that this third term occupies a politicized space out of which “differential consciousness arises” and where a new racial, sexual, ethnic, physical identity politics is constructed (cf. Sandoval 2000, p. 71). Equally, as the author remarked, This Bridge Called my Back aimed to ‘forge links with women of color from every region’ (Moraga and Anzaldúa 1981, p. 8).

Already in 1979, the magazine ‘Heresies’ had devoted an issue to Third World Women, mainly giving voice to black women living in the United States. Only a little later, acknowledging the downfalls of white global feminism, incapable of addressing the fights of non-white women, in 1980 Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta curated ‘Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists in the United States’ at the A.I.R. Gallery, New York.6 On that occasion she wrote: ‘American Feminism as it stands is basically a white middle class movement. This exhibition points not necessarily to the injustice or incapacity of a society that has not been willing to include us, but more towards a personal will to continue being “other”’ (Bryan-Wilson 2013, p. 33). This statement points to a self-marginalized position understood as a site of resistance and production of knowledge that challenges western ego-epistemology and ontology; in doing so it partly conforms to third world feminism that, with a more individualist approach, stresses the uniqueness of third world women’s condition.

In this context, the analysis of specific cultural backgrounds inevitably produces differences between Western and third world feminism, and consequently could lead to what Mohanty calls the ‘construction of the average Third World woman.’. Similarly, Ella Shoat argues that ‘Eurocentric definitions of feminism cast “third-world” women into a fixed stereotypical role, in which they play the part of passive victims lacking any form of agency’; she goes on in affirming that women involved into anti-colonial struggle have not been considered relevant to feminism, since they were not explicitly labeled as feminist (Shohat 2001, p. 1269). As it can be inferred, such stereotypical and reductive construction is established not only on the basis of a woman’s gender and sexual oppression, but also on her being citizen of the third world (and therefore poor uneducated, family orientated, victimized and oppressed). In an attempt to defeat this process of colonization and progressive homogenization, any intellectual discussion on third world feminism should simultaneously seek to criticize Western feminism internally, to undermine ‘the feminist osmosis thesis’—according to which ‘being female and being feminist are one and the same’ (as much as ‘we are all oppressed and hence we all resist’)—and to formulate ‘autonomous feminist concerns and strategies that are geographically, historically, and culturally grounded,’ therefore taking into account also the intersection of gender, race, class and national identity (Mohanty 2003, pp. 19–20). Moreover, as Mohanty remarks, ‘this is in contrast to the (implicit) self-representation of Western women as educated, as modern and as having control over their own bodies and sexualities and the freedom to make their own decisions’ (ibid., p. 22).

What is problematic with a “global sisterhood” approach is that it assumes ‘womanhood’ in ahistorical terms, ‘instead of analytically demonstrating the production of women as socioeconomic, political groups within particular local contexts’ (Mohanty 2003, p. 31). ‘This analytical move’, Mohanty claims, ‘limits the definition of the female subject to gender identity, completely bypassing social class and ethnic identities. What characterizes women as a group is their gender over and above everything else, indicating a monolithic notion of sexual difference’ (ibid.). As emphasized above, the appropriation of third world feminism by Western feminism causes the inevitable homogenization of differences, flattening the pluralities in terms of social classes and ethnic origins; one must highlight the diversity that featured the struggles of women in the West and in the Third World, since the appropriate acknowledgement of such struggles—struggles that vary according to their location—could rewrite hegemonic Western feminism.

Opposing both the acknowledgment of third world women as a homogenous category ‘victimized by the combined weight of their traditions, culture and beliefs, and “our” (Eurocentric) history’, as well as the notion of “universal sisterhood”—‘that assumes a commonality of gender experience across race and national line’—Mohanty calls for a new analytical methodology that takes in to account third world women and their complexities in relation to their history, cultural context, identity, etc. (Mohanty 2003, pp. 192–93). She also posits the notion of “solidarity” among different communities of women as a replacement for the above-mentioned global sisterhood. The latter—to which Audre Lorde ironically finds a responding label namely “Sister Outsider”—was developed by Robin Morgan in Sisterhood is Global, which aimed to an inclusive definition of woman (cf. Lorde 1984). As explained above, this idea is constructed upon the conviction that women are globally subjected to the norms of the “big brother”, a new label for patriarchy. This generates the idea of a common condition, an equal status, which not only affects women on the base of their gender, but it is in turn projected upon men too. Manhood, as much as womanhood, becomes an abstract category performing a kind of imperialist power. Interestingly, as Denise deCaires Narain observes, this approach not only levels differences but also ‘absolves all women of any complicity in these dominant power structures’ (deCareis Narain 2004, p. 241). The global feminism’s response to the lack of consideration towards women involved in anti-colonial and anti-racial struggles outside the Western world also have prompt what Shoat calls the “sponge/additive approach”. ‘In this approach’, the scholar explains, ‘paradigms that are generated from a U.S. perspective are extended onto “others” whose lives and practices become absorbed into a homogenizing, overarching feminist master narrative,’ therefore pointing out to both the danger of being unwillingly subjected to a colonizing mind-frame and to the need of finding a methodology that could avoid this flaw (Shohat 2001, p. 1270).

We have seen that as much as Grosfoguel’s understanding of decoloniality is based on the refusal of the western idea of “universalism”, third world feminism, compliant with so-called third wave feminism, rejects positions and arguments preached by the (Western) second wave; both have been in search of a way of discarding homogenizing tendencies, which unwillingly undergird both the movement called “Global Feminism” and the label “Global South”.7 However, this does not intend to be a deconstructive essay but one that performs a deconstructive dialectic to foster a subsequent re-construction of meanings and tools. Therefore, as much as it is legit to question, it is necessary to seek an alternative. But what is the alternative?

3.

Unlike colonization, the coloniality of gender is still with us; it is what lies at the intersection of gender and class and race as central constructs of the capitalist world system of power.María C. Lugones, quoted in (Guerrero 2017, p. 239)

Before moving into the proposal of what I reckon could be a way out of the theoretical impasse which affects the study of Latin American women artists pursuing a decolonial approach, I feel the need to dig a bit more into the current use of the language. I anticipate that the language in the field suffers from the same colonizing and universalizing tendencies that we have unmasked in the preceding sections. The task is therefore to recover an epistemology of the “negative” as a space of knowledge and cultural production.

In the decolonial research of Latin American women artists, a heterogeneous and problematic terminology and an overwhelming appearance of labels comes into play. One, indeed, would argue that such a topic pertains to several area of studies—which respond to the U.S. tendency to offer countless courses on these matters—gender studies, feminism, feminist art, Latin America art and so forth, each with its own vocabulary. These terms have been subjected to several attempts of being contained by clear definitions. For example, Elisabeth Doré defines gender as follows:

Gender is the social construction of sexual difference. It is the outcome of struggles over the ways societies define and regulate femininity and masculinity. By its nature gender is multidimensional. It is recreated and transformed through an inseparable mix of norms and behaviors that are cultural, economic, historical, sociological, linguistic and always political’.Doré (1997, p. 9)

As highlighted by the above quote, which testifies to the continue tendency to categorize, if sex is a biological condition, gender is a multidimensional social construct. The label “feminine” is more difficult to pin down, often being defined as something that distinguishes the production of female artists. In 1993 the exhibition Ultramodern: The Art of Contemporary Brazil was organized and accompanied by a catalogue with the same name. In one of the essays, Aracy A. Amaral celebrated the longstanding inclusion of Brazilian women in the arts: ‘In traditional Latin cultures, the space reserved for handcrafted work is occupied solely by women. […] thus since the beginning of the century Brazilian women have gained increasing prominence as artists and musicians’ (Amaral 1993, pp. 17–18). However, Amaral qualifies the art produced by women as affected by their sex: ‘what seems to exist is a composite of feminine characteristics in art. […] The “feminine”, from my perspective, is linked to the fine sensibility of women. As creators of life they are connected more intimately then their male counterparts. This intimate connection can be discerned in their care for the fragile new born child who comes from their own wombs, whom they will to protect.’. The assumption that women artists necessarily make ‘feminine’ art belongs to that long-term discourse, which acknowledges sexuality and gender as universal categories—as already claimed. Related to this is the issue concerning the definition of what ‘feminist art’ is; too often women artists have been labeled as ‘feminist’ despite their agendas. This mistake has been witnessed, for example, in many exhibitions that have featured female artists alongside feminist artists without establishing clear boundaries between the two.

On this matter, Argentinian art historian and curator Andrea Giunta suggests a methodology that ‘requires not calling all works produced by women feminist art’.8 She writes:

To establish a clear differentiation between feminist art—that displays a feminist agenda—and the art produced by women that has been interpreted as feminist is relevant to a discourse on Latin America, where not all women artists saw themselves as feminists.9 Not only were feminist activist movements much less important compared to analogous movements in the West, but also the production of art was particularly reflective of the lack of socio-political freedom enforced by repressive dictatorial regimes. Paralleled to what occurred in Europe and in the United States in the sixties and seventies, feminist movements, which interested both Central and South America, were of a different sort: they had been internalized to wide spread fights for freedom and human rights. A novel awareness of women’s condition occurred at different times and according to different factors that varied from country to country within Latin America. In this context we find, for example, Chilean writer Diamela Eltit who affirmed that a ‘woman’s body broke its prolonged cultural status of physical inferiority to become identical to that of man, in the name of the construction of an egalitarian future’, thus uncovering a certain consciousness of the role of the women in contemporaneous society and prompting a rethinking of the traditional paradigms of the feminine and the masculine.10 Nonetheless, reflecting on subjectivity and on the status of women in society, both from a biological and a cultural perspective, they explored themes entangled with feminist agendas, putting particular emphasis on the body, since ‘the body was the battlefield from which they launched new knowledge in which performance was a privileged instrument’ (Giunta 2017, p. 30). Writing on the link between capitalism, social reproduction and the women’s body, Silvia Federici too defines the boundaries of the her research reflecting on categorizations in the field, affirming that if “femininity” has been constituted in a capitalist society as a work-function masking the production of the work-force under the coverage of a biological destiny, then “women’s history” is “class history”, and the question that has to be asked is weather the sexual division of labor that has produced that particular object has been transcended. If the answer is a negative one, then “women” is a legitimate category of analysis, and the activities associated with “reproduction” remain a crucial ground of struggle for women’ (Federici 2014a, pp. 14–15). Federici’s discourse stems from the factual sexual division of labor to justify the use of ‘woman’ as a legitimate category of analysis; in her study women are grouped together under the struggles associated with social reproduction.I establish a difference between feminist artists and artistic feminism. I consider feminist artists those creators who deliberately and systematically attempted to build a feminist artistic repertoire and language (most of them were also feminist activists). I use the term artistic feminism to refer to the position of the historians who study art from the perspective agenda.Giunta (2017, p. 34, ft. 2)

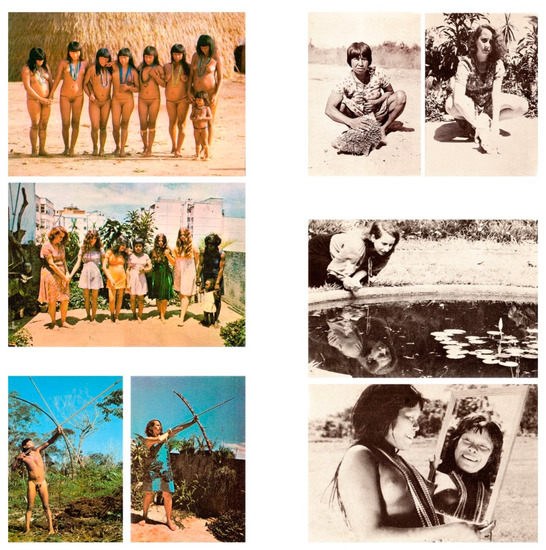

From these debates emerge the necessity to further discuss and problematize the association made by scholars between ‘feminine’ and womanhood as well as to redefine the terminology used in the field of feminist art history. Similarly, we must distinguish between those artists who consciously display and perform a decolonizing agenda, engaging with their colonial past and exploring postcolonial concerns, and those whose work have been interpreted as both decolonial and decolonizing. Brazilian artist Anna Bella Geiger’s (b. Rio de Janeiro 1933) work offers a powerful example about the ambivalence that defines the boundaries of the aforementioned differentiations. In Declaração em retrato No. 1 (Statement in portrait no. 1, 1974; Figure 1), a black and white video portraying the artist talking to the camera while stroking a white cat, Geiger openly reports the legacy of Brazil’s colonization stating: “I am Latin America. I am Brazilian. They take a position of colonizing us. They always come to dictate ideas.”. Notably, the artist uses the present tense, hence denoting a situation that continues even currently. Equally visually striking is Geiger’s work Brasil native, Brasil alienígena (Native Brazil, alien Brazil, 1977; Figure 2), where the artist recreates iconic photos portraying indigenous Brazilian populations, mimicking their gestures and their poses but in contemporaneous settings, creating unexpected contrasts. These photographs refer to Brazil’s multi-ethnic identity and question the use and significance of labels such as “native” and “alien”. Such work has often been interpreted according to a postcolonial perspective and through a feminist lens, since it clearly comments upon Brazilian colonial past and the legacy of this heritage. However, Geiger herself gives a less radical interpretation of it: ‘In the ’80s and ’90s, I read and taught about feminism. But I always thought these postcards were more simply the work of a Brazilian artist living in that difficult moment in which we were deprived of liberty, the right to vote, etc., more than a feminist approach. Some people saw an anti-colonialist position in that work, but to me it was more about drawing a relationship about the deprivation of democratic possibilities on a very simple level.’11 She therefore highlights the boundary between different ways of dealing with coloniality in a postcolonial era, emphasizing the discrepancy between artistic intention and decolonial readings.

Figure 1.

Anna Bella Geiger, Declaração em retrato No. 1 (Statement in Portrait No. 1), 1974. Single channel video, black and white, sound. Duration: 16 min. 18 sec. Videographer: Tom Job Azulay. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. (Film still) Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria, New York.

Figure 2.

Bella Geiger, Brasil nativo, Brasil alienígena (Native Brazil, Alien Brazil), 1976–1977. Postcards. 17 1/8 in × 46 in. (43.5 cm × 116.8 cm), framed. Limited edition. Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria, New York.

4.

After having acknowledged language as a powerful and dangerous colonizing apparatus, I shall go back to Grosfoguel initial questions: what kind of knowledge is contemporary culture going to produce, and how to ‘avoid’ European universalism and third world fundamentalism. These matters have been partly developed in aforementioned 8th issue of the journal Heresies, which featured the work of both Ana Mendieta and Zarina, among others, and hosted views and memories of black, Hispanic and Chicana women living in the United States. On this occasion, one of the editors, Joan Braderman, posited the following enquiries:

In the attempt to emphasize and uncover peculiarities that pertains to non-Western women’s condition, Braderman felt back in to the “essentialist” trap, consciously or unconsciously reiterating a (self)marginalized position and a Eurocentric homogenizing view. She did so by not sufficiently acknowledging womanhood and related phenomena cross-culturally and transnationally, and displaying a nearsighted stance.Is there a difference in the way feminism functions among Third World women and white women? Can working relationships be established and maintained between lesbian and heterosexual Third World women? Can Third World women afford to participate in volunteerism, since we have little, if any financial security as it is? Can we as Third World women work collectively? Do we recognize that many of us actually practice feminist modes of being while rejecting them in theory?Braderman (1989, p. 1)

On the matter of transnationalism—key notion to release third world feminism from a fundamentalist and essentialist approach—Ella Shohat argues:

In a so-called “global” age, we cannot ignore that images, sounds and goods travel and populations migrate, constantly shifting the hub of the production of knowledge and the nature of such knowledge. It is important to say in this respect that I do not believe the adoption of transnational feminism to stand in contrast with third world feminism: since I do not think intellectual discourses or disciplines as framed by rigid grids but as interwoven discussions, I rather reckon the two methodologies as complementing each other. As a matter of fact, both third world feminism and transnational feminism criticize North American feminism and share two concerns: first, that the analysis of third world women’s conditions ‘should be historically situated’; and second, that third world women’s agency and voices should be respected (Seoduherr 2014; also cf. Visions 1998). However, they both diverge in the premises of their criticism, since transnational feminism privileges a multicultural and intersectional approach and dismisses the nation state and nationalism as irrelevant to a feminist discourse, while third world feminism specifically focuses on local and national contexts (ibid.). To avoid the study of women and gender issues in isolation, third world feminist ideology should adopt a transnational approach. Likewise, Maura Reilly, curator of the Global Feminism exhibition (2007), supportive of this so-to-speak tactic, argues ‘“Transnational” is specifically chosen here in order to designate a new postcolonial interest in exceeding what Enwezor calls “the borders of the colonized world … by making empire’s former OTHER visible at all times”’ (Pérez-Ratton 2007, p. 35). In her claim, a transnational discourse backs up a decolonial narrative.Any serious analysis has to begin from the premise that genders, sexualities, races, classes, nations, and even continents exist not as hermetically sealed entities but, rather, as part of a set of permeable, interwoven relationships.Shohat (2001, p. 1269)

For the art, the strategy of decolonizing third world feminism—concurrently fostering a transnational outlook—is translated into those practices that question and attempt to dismiss the stereotypical representation of women in (parts of) the third world or how such representation was expected to be visually articulated, thereby disavowing the logic of “coloniality of gender”. Any study on women artists coming from (what has been designated as) a third world country must unveil the presence of multiple feminisms, decolonize their subaltern presence, and question western canons; in doing so it must aim to further complicate the idea of feminism in Latin America and indicate how it differs from other third world continents. Artistic practices must not only be analyzed in relation to the artists’ native contexts, disavowing the understanding of Latin America as a monolithic continent, but also unpacked from different perspectives—religious, cultural, racial and socio-political. The contest of creation of each work shall be scrutinized with an attentive reading of indigenous sources but in transnational perspective, emphasizing the exchange between local and global. Thus, As Shohat argues:

To have a truly relational analysis, we would have to address the operative terms and axes of stratifications typical of specific contexts […] Issues of class, nation, religion, gender, and sexuality all meet and contest at these intersections. But, rather than lead us into immobility, such articulations of contradictions help us chart the conflictual positioning of women in the contemporary world.Shohat (2001, p. 1272)

Borrowing from Shoat, the aim of any study concerning women artists in third world countries—in this case, specifically from Latin America—should deploy the grids that prevent methodological tools from adopting a truly transnational point of view. Yet, one also should depart from those grids, in order to flesh out critical perspectives often associated with academic categories (cf. Shoat 2016, p. xv).

Certainly, as Ranjoo Seudu Herr rightfully acknowledges, transnational feminism—which in the nineties seemed to have achieved a shared approval—has its flaws, having the term lately become so ubiquitous, that much of its political valence seems to have become evaluated (cf. Grewan and Kaplan 2001). Moreover, canonical transnational feminism has been suspicious of nation state and nationalism claiming that ‘the concept of national identity [has served] the interests of various patriarchies in multiple locations’ (cf. Hegemonies 1994, p. 22).

In this regard, Ella Shohat finds a compromise, arguing that ‘a polycentric multiculturalism entails a profound reconceptualization and restructuring of intercommunal relations within and beyond the nation state. It hopes to decolonize representation not only in terms of cultural artifacts but also in terms of the “communities” behind the artifacts,’ and therefore placing a decolonial struggle as commonly shared by the two waves (cf. Visions 1998).12 Nonetheless, it is important in this respect to visually articulate what I mean by a convergence between transnational and third world feminism, and how such ‘methodological merging’ provides with, what I reckon to be, an appropriate account of certain art practices in the current cultural context. The work of Marta María Pérez Bravo offers the visual expression of such theoretical combination.

5.

The maternal body has a paradoxical status as both natural and exceptional, a sanctioned yet highly circumscribed form of female embodiment; like the nude, it is both a powerful cultural idea and a bodily state, but one which is unstable and open to multiple meanings.Betterton (1999, p. 1)

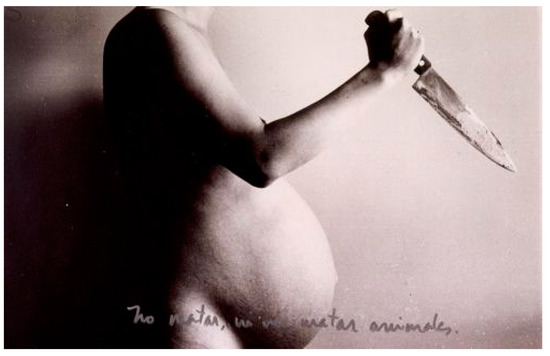

The image of Marta María Pérez Bravo pointing a knife towards her swollen womb is a brave work of art. For its striking and horrifying iconography, in Cuba the photograph has become almost as famous as Alberto Korda’s iconic shoot of Che Guevara (cf. Mosquera 1995). Brave because it makes our common sense related to motherhood teeter. Maternity also itself needs courage. Pérez Bravo’s work decolonizes the maternal body from a reassuring, mythic, and Christian vision of motherhood, prompting a “conflicting” view of it. At the same time, the medium she employs speaks a transnational language, bridging local with global factors.

In the aforementioned photograph, which is titled No matar, ni ver matar animales (Neither Kill, Nor Watch Animals Being Killed, 1986; Figure 3) and belongs tothe series Para concebir (To conceive, 1985–1986), Pérez Bravo’s swollen womb is seen in profile and at the last stage of pregnancy. The artist, whose head and legs are cut off the frame, brandishes a knife against her belly. In doing so, she creates unexpected oxymorons in her antiromantic depiction of maternity: a carnal pregnant body, rendered with realism and portrayed naked in its visceral entirety, appears as solemn as a place of worship; it is enriched with sacred associations, since it bears references to traditions of Santería and Palo Monte—two Afro-Cuban religions that draw from Yoruba (western Africa) and Kongo/Angola (Central Africa) practices respectively. This view that considers the body as a divinely inspired work of art exists in contrast to the Judeo-Christian conception of the body as corrupted, impure and so forth (cf. Schultz 2008). Afro-Cubanism did emerge already in the forties, being one of the three main trends that characterized Cuban vanguardia, or “new art”, together with Criollismo and painting of social commitment; it was influenced by the rediscovery of Africa through the research of Fernando Ortiz (Havana, 1881–1969) and later Lydia Cabrera (Havana, 1899—Miami, 1991), which triggered a great interest in Afro-Cuban traditions among contemporaneous intellectuals, particularly novelist and musicologist Alejo Carpentier and painter Eduardo Abela (Cabrera 2015).

Figure 3.

Marta María Pérez Bravo, No matar, ni ver matar animales (Neither Kill, Nor Watch Animals Being Killed), 1986. Courtesy of the artist.

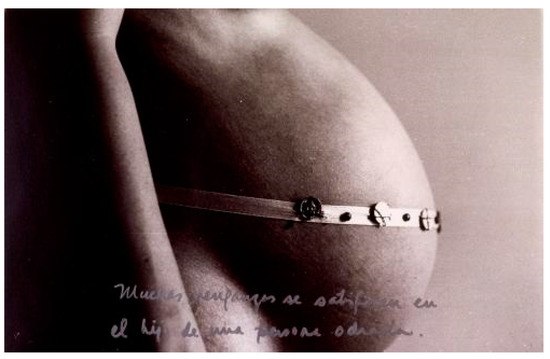

Cuban-born artist Marta María Pérez Bravo’s series of five photographs Para Concebir (To Conceive, 1985–86) questions the taboo of motherhood as something that should not be seen, patently displaying features that distinguish a changing body at the very last stage of pregnancy. At the same time, title and composition of each photo challenge a set of popular superstitions rooted in the Island. In Muchas venganzas se satisfacen en el hijo de una persona odiada (Many Vengeances are Satisfied through the Child of a Hated Person, 1986; Figure 4), the artist photographs herself with a belt around her belly. The very accentuated black and white chiaroscuro of the composition almost dematerializes the edges of the figure that emerges from a neutral background; concurrently, it stresses the presence of skin’s stretch marks around the womb. Notably, Para Concebir is a series of self-portraits narrating Pérez Bravo’s own experience of pregnancy; this creates a double identification between author—the subject agent—and object. Through these photographs, Pérez Bravo scrutinizes her own pregnancy and the moment after birth with a keen eye, as a way for her to get to know a body subsumed to a constant metamorphosis; in this process of (re)discovery, the body is conceived as something new, unknown and detached from her prior knowledge (Ussher 2006, p. 89). Nonetheless, her head is very often cut off the composition, an expedient that hides the artist’s identity and confers to these body parts a demand of universal identification—regardless of the distinctiveness of a single woman.

Figure 4.

Marta María Pérez Bravo, Muchas venganzas se satisfacen en el hijo de una persona odiada (Many Vengeances are Satisfied through the Child of a Hated Person), 1985–86. Courtesy of the artist.

The belt around the waist bears a twofold allusion: coupled with the title, it refers to beliefs embedded in Afro-Cuban traditions; concurrently, it constitutes a nod to the most common iconography of the “Madonna del Parto” of medieval origins. In fact, early Tuscan painters used to depict the pregnant Virgin Mary with a belt embracing the upper part of her belly—a compositional device, quickly discarded, employed to signify that the woman was pregnant without having to reveal too much of her swollen womb. Conversely during antiquity, the belt used to denote a married woman and was removed during gestation. Later in the history of western Christian iconography, the belt persisted to be associate with the Virgin Mary, but not with her pregnancy (cf. Mioscisa 2000).

The belt in the photograph—in the guise of a ribbon—is adorned with beads and charms of difficult exegesis. Pregnant Cuban women sometimes wear ribbons around their stomachs (especially in yellow or red) in order to protect the developing fetus against the evil eye, accidents, and problems. The first charm attached to the belt looks like a ship’s wheel: that could refer to Yemayá, the Virgen de la Regla, “anchoring” the fetus to the body of the subject. The other larger buttons look like Kongo cosmograms, often present in Pérez Bravo’s works. The beads could have some sort of connection to a particular “oricha” (deity) of Santería or perhaps an evocation of (various) sub-Saharan African traditions of wearing a “fertility” belt as an adornment of a young woman.

The line created by the belt—that divides the composition in two parts—can resonate with the axis mundi of Kongo cosmology (evident in Palo Monte and in Haitian Vodou): the belt stands for the horizontal axis and the woman herself is positioned as the vertical axis connecting the two domains. The title, Many Vengeances are Satisfied through the Child of a Hated Person, is of difficult interpretation too: firstly, it refers to the idea that a hated person is often the subject of the “mal de ojo”, the evil eye, which can cause harm by simply looking at the person affected by it; the second hypothesis is that the ‘hated’ person may be the object of witchcraft, or volt sorcery, and the child of that person would be the best target, since there is nothing more valuable than one’s own offspring. For this reason, Cubans will often give to their children “despojos”, or cleansings at home with herbs and holy water, and have them wear jewelry that contains pieces of coral, which is thought to absorb the bad intensions of others13.

Adopting the same compositional angle, No matar, ni ver matar animales, sees the artist on the verge of committing a sacrifice—or perhaps the sacrifice of her own body—a gesture that contests the religious creed according to which pregnant women cannot perform or assist to sacrifices of animals being performed (cf. Martín-Sevillano 2011). Indeed, in Santería and Palo Monte among other cultures, women are forbidden to attend a number of ceremonies when pregnant or menstruating, that is when their body undertakes a biological metamorphoses, becoming a dangerous, monstrous ‘site of pollution and source of dread’, subjected to the bias of a patriarchal set of values (cf. Ussher 2006).

By assembling this outstanding composition, Pérez Bravo challenges, provocatively, the stigmas associated to female reproductive functions by questioning ideals rooted into Afro-Cuban practices and patriarchal traditions at large. Her gesture puts into threat her own abdomen, site of gestation, burdened by male expectations. In doing so, she creates a representation of herself as active subjects, rather than passive objects of masculine contemplation, and disrupts ‘dominative pleasures of the patriarchal visualfield’.14 At the same time, the adoption of items and titles coming from folk indigenous traditions brings these forgotten rituals and beliefs to the surface, making up for the marginalization to which these cultures have been subjected in contemporary society. Borrowing from Rosie Mclaren, I argue that from this marginal space, a ‘border crossing’ between the reproductive body and native cultures, Pérez Bravo finds a way to ‘manoeuvre the imaginary and the symbolic signifiers that codify the self-representation of the actual bodies of women’ (cf. Mclare 1999).

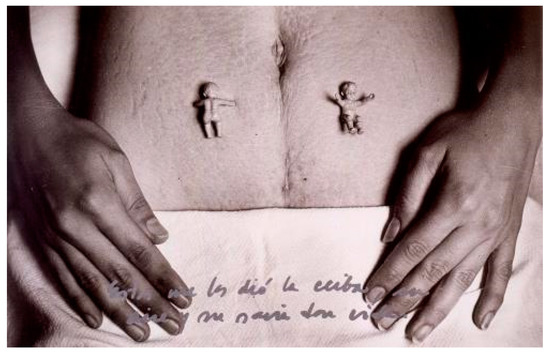

The last photograph of the series, titled Estos me los dio la ceiba, su aire y su nacri dan vida (These were given to me by the ceiba tree, its air and its nacri give life, 1986; Figure 5) disrupts the canonical image of an idealized female body by immortalizing the womb after giving birth; the close-up explicitly emphasizes skin marks and the scar left by the C-section. The belly is adorned with two little statues, which embody Pérez Bravo’s twin daughters. They inform her own form of twin worship by paying homage to ibeji or the twin gods.

Figure 5.

Marta María Pérez Bravo, Estos me los dio la ceiba, su aire y su nacri dan vida (These Were Given to Me by the Ceiba Tree, its Air and its Nacri Give Life), 1986.Courtesy of the artist.

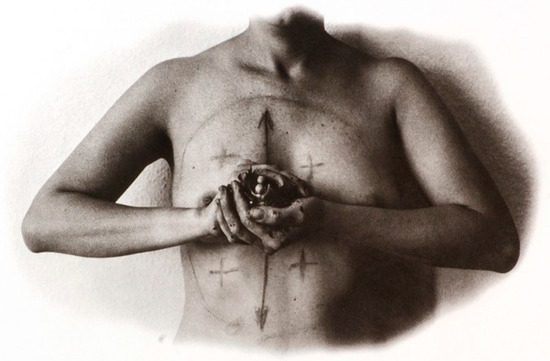

The dolls in the shape of infants here placed on the artist’s abdomen appears also in another work, Macuto (1991; Figure 6), where the artist holds a sacred bundle, called Macuto or Nkuto, a Palo Monte protective charm, comprising the two little statues as a source of power. As Anna Belén Martín Sevillano suggests, ‘the representation of her own children in the religious objects conveys the importance the artist gives to motherhood emphasizing the benefits it brings such as energy and protection’. I argue that such representation also connects the viewer with the narrative on the pregnant body Pérez Bravo develops in the early series Para Concebir and the anxiety that comes with it again places her work in a hybrid net of references. A “cosmogram”, a configuration central to Kongo and Kongo-based philosophy is drawn all over the artist’s chest: it represents the “firma”—a signature in this case embodied by the crosses—and the “four moments of the sun” that evoke the strength of the earth and the winds.15 As Gerardo Mosquera remarks, ‘to identify the center of the chest of a specific woman with the very center of the cosmos, in relation to maternity, is one of the most powerful images that Africa has offered’, a statement that stresses a constant process of transculturation that Pérez Bravo filters through her female identity. As Pérez Bravo herself emphasizes:

From reference to books and from contact with believers and practitioners of these religions I have extracted the concepts, the conception of the world, the ideas and material forms of expression of these religions that have allowed me to establish a close relationship between these beliefs and my own, thus creating a parallelism between this richness of spirit and artistic expression. I often face my works like someone who peers into a temple, a church, a sacred place. This spiritual relationship I have with my art is of utmost importance, and as a rule, a high degree of moral compromise exists with the theme [in] a piece of art.Marta María Pérez Bravo quoted in (Martín-Sevillano 2011, p. 149)

Figure 6.

Marta María Pérez Bravo, Macuto, 1991.Courtesy of the artist.

6.

Together with José Bedia, María Magdalena Campos-Pons and others, Pérez Bravo belongs to the post 1959 group of Cuban artists who graduated from top schools such as the Escuela de Artes Plásticas San Alejandro, Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA) and Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), products of the revolutionary government’s conceptual and financial commitment to education in the arts. This generation gained international recognition, adding to this the experience of the exile, which partly explains the cultural hybridity undertook by their practice and their relation with both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ culture. Furthermore, Pérez Bravo’s use of photography as privileged medium is certainly connected to Cuba’s own history, in which photography gained its greater momentum during the 1959 revolution. Notably Gerardo Mosquera differentiates Pérez Bravo’s use of photography from contemporaneous international artists merging studio-photographs with Yoruba and Mesoamerican traditions—such as Rotmi Fani Kayode, Mario Cravo Neto, Gerardo Suter, and Luis González Palma—by stressing the testimonial personalized character of her compositions, which take advantage of photography as documentations and not of its artistic potential (Mosquera 1995, p. 53). Mosquera highlights the documentary character of Pérez Bravo’s work to the point of coupling it with Ana Mendieta’s use of photography as testimonio: ‘the photograph is the final product’, he suggests, ‘[and] acts rather as a vehicle for a sort of frozen performance’(ibid).

Denying the influences of Cuban documentary photography on Pérez Bravo’s work would be pointless; nevertheless, I wish to question and undermine the emphasis that Mosquera puts on this aspect of her work. Alberto Korda—who belonged to the generations immediately before Pérez Bravo—consecrated photography in Cuba as the documentary medium par excellence: his black and white shots of Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, and moments of the revolution travelled all around the world canonizing a certain style of portraiture—a photographic framing that derived from the soviet model of the Thirties—and creating instants of Cuban recent history. The gazing off in the distance embraced by the portrait of Che Guevara in “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter” had been already codified in soviet aesthetics as the expedient to communicate faith in the future: photography acts as both testimonio and propaganda. At the same time as Korda, Eduardo Hernández Toledo, better known as Guayo, the first Cuban photographer in the Sierra Maestra, realized “De la tiranía a la liberación”, a documentary that demonstrates why armed forced were necessary and that was released not by chance in early 1959 and equally witnesses the importance of the medium employed.

Pérez Bravo’s practice is no doubt affected by the momentum gained by photo-reportage in Cuba in between the fifties and the sixties: both series Para concebir and Recuerdo de nuestro bebé (Memory of our baby, 1987–88) act as chronicles of Pérez Bravo’s maternity, documenting moments of gestation, and breast-feeding and child rearing respectively. However, further investigating their quality and style, Pérez Bravo’s works technically resemble studio-photographs of the beginning of the century, for example the shots of nudes made popular by Cuban photographer Joaquín Blez Marcé among the local bourgeoisie. Unique was Blez’s handling of the light: the photographer used to position the source of lighting always at the side of the body, suggesting the sculptural appearance of its volumes through a clever usage of the chiaroscuro, a modus operandi similarly adopted by Pérez Bravo to emphasize the corporeality of the female body. Blez introduced also the shading or sfumato technique to give face and body of the models a great allure. This strategy was re-employed by Pérez Bravo to blur the contours of her compositions, placing her self-portraits against neutral and fading-away backgrounds. Adopting this very technique, the artist takes the subject out of any temporal context, but accentuates its cultural provenance—or provenances, since the syncretism deployed by her work—through Afro-Cuban elements.

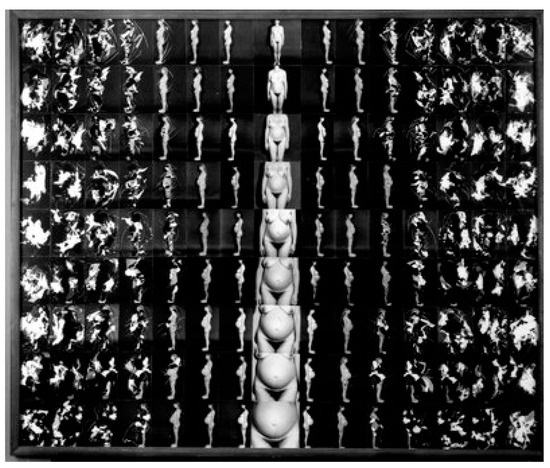

The combination between photography and the mise en scene of the female body through self-representation has been a recurring strategy appropriated by early feminist artists—Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke and Ewa Partum, just to name a few. Black and white photographs of pregnant women characterized the work of several of these artists, particularly in the West. For example, In between 1977 and 1982, German artist Annegret Soltau realized Schwanger (Pregnant; Figure 7), a series of black and white photo-etchings of her own pregnancy. Concern with the anxiety deriving not only from the role of being a mother but also from the necessity of combining the artist’s profession and motherhood, Soltau offers a commentary on the politics of reproduction through the serial repetition of her pregnant body, whose transmission often appears disturbed, like in the presence of interferences.16 Such repetition changes across the grid that frames it, in a constant process of constructing and deconstructing the image: departing from a close-up of the swollen womb, the scene progressively becomes larger, creating an optical play that comes to encompass the artist’s body. These compositional devices are meant to symbolize the tension between productive and reproductive labor that the artist seeks to manifest. Soltau and Pérez Bravo handle the photographic medium with great difference and refer to heterogeneous cultural contexts: the use of serial photo-etchings enclosed in a grid contrasts with what look like hieratic tableaux in which Afro-Cuban elements are dislocated from their traditional setting and become part of an ‘art gallery’. However, both artists insist on the display of their own bodies to filter maternal anxieties deriving from gender inequality rooted in both Western and postcolonial societies.

Figure 7.

Annegret Soltau, Schwanger (Pregnant), 1977–82. Copyright: Annegret Soltau, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019.

To my discussion, that aims to merge a decolonial perspective with a transnational approach, Pérez Bravo’s use of photography offers both a “horizontal” and a “vertical” analysis of the work itself. Both views intersect with each other, suggesting a richer and conflicting idea of the maternal body: the latter is seen through the lens of religious dogma and values inherited from the colonial period and in dialogue with contemporaneous artists across the ocean. Pérez Bravo acknowledges and treats photography as an artistic medium per se exploiting its properties and its impact (cf. Amador Gómez-Quintero and Bustillo 2002, p. 5); on one hand, to pay homage to both Cuban photographic tradition and western feminist use of it as pioneering medium in this discipline, on the other, to create female portraits that combine both references commenting upon a specific socio-cultural reality and the will of a cross-cultural feminine identification. Her work plays on twofold level, which satisfies Grosfoguel’s initial queries: it produces a decolonized view of bodies and identities, in which Afro-Cuban traditions implanted in the Caribbean gain new life, and, in turn, offers to be subjected to both a decolonized and transnational interpretation, allowing scholars to overcome third world fundamentalism, self-marginalization, essentialism and Euro-American hegemonic universalism by merging indigenous with international concerns.

Both art and art history have their raison d’être in the production of knowledge. In this essay, I have questioned and attempted to define what kind of knowledge can art historians produce when they approach the work by Latin American women artists, showing the example of Pérez Bravo’s practice. Her work indeed allows the merging between different methodological approaches and disciplines: not only third world feminism that looks at native contexts but also transnational feminism, which allows to understand the work in dialogue with international tendencies. These women inhabit the contemporaneous world, a world that is obviously multiple and syncretic. Grosfoguel, my starting point, posits the same question, or better, rhetorically asks if we are going to produce a knowledge that reiterates the Eurocentric universalism and the God’s eye view he sees affecting centuries of Western (and therefore what he negatively sees as ‘zero-point’) philosophy and visual culture. And he does so by postulating an issue, which on the one hand exposes western philosophy’s flaws, and attempts to avoid universalism and hegemonic tendencies, on the other it cannot but be acknowledged as undeniably universal.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Amador Gómez-Quintero, Raysa E., and Mireya Pérez Bustillo. 2002. The Female Body: Perspectives of Latin American Artists. Westport: Greenwood Press, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, Aracy A. 1993. Brazil: Women in the Art. In Ultramodern: The Art of Contemporary Brazil. Edited by Aracy A. Amaral and Paulo Herkenhoff. Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts, pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bettelheim, Judith. 2001. Palo Monte Mayombe and its influence on Cuban Contemporary Art. African Studies 34: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betterton, Rosemary. 1999. Maternal Bodies in the Visual Arts. Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Braderman, Joan. 1989. Editorial Statement. Heresies 8: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan-Wilson, Julia. 2013. Against the Body: Interpreting Ana Mendieta. In Ana Mendieta: Traces. Edited by Stephanie Rosenthal. London: Hayward Gallery of Art, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Lydia. 2015. Lydia Cabrera was Champion Critic of Religions of Santería and Palo Monte, Which She Discusses in El Monte. Barcelona: Linkgua. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Gómez, Santiago. 2019. Zero Point Hubris: Science, Race, Enlightenment in the New Granada. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- deCareis Narain, Denis. 2004. What happened to Global Sisterhood? Writing and Reading the ‘Postcolonial Woman. In Third Wave Feminism. Edited by S. Gillis, G. Howie and R. Munford. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakaki, Angela, and Kirsten Loyd. 2017. Social Reproduction and Art. Third Text 31: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Doré, Elisabeth. 1997. Gender Politics in Latin America: Debates in Theory and Practice. New York: Monthly Review Press, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Federici, Silvia. 2014a. Caliban and the Witch. Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, Andrea. 2017. The Iconographic Turn: The Denormalization of Bodies and Sensibilities in the work of Latin American women artists. Radical Women 34: ft. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Grewan, Inderpal, and Caren Kaplan. 2001. Global Identities: Theorizing Transnational Studies of Sexuality. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 7: 663–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griefen, Kat. 2011. Ana Mendieta at A.I.R. Gallery, 1977–82. Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 21: 171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2011. Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political-Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking and Global Coloniality. TRASMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2012. Decolonizing Western Uni-versalisms: Decolonial Pluri-versalism from Aimé Césaire to the Zapatistas. TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1: 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, Marcela. 2017. ‘Yo misma fui mi ruta’: A Decolonial Feminist Analysis of Art from the Hispanic Carabbean. In Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960—1980. Edited by Andrea Giunta and Cecilia Fajardo Hill. Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Hegemonies, Scattered. 1994. Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices. Edited by Inderpal Grewan and Caren Kaplan. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Pressa, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, Fredric. 1992. The Geopolitical Aesthetics: Cinema and Space in the World System. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, London: Critish Film Institute, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kurian, Alka. 1996. Feminism and the Developing World. In The Icon Critical Dictionary of Feminism and Postfeminism. Edited by Sarah Gamble. Cambridge: Icon, pp. 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Miwon. 1996. Bloody Valentines Afterimages by Ana Mendieta. In Inside the Visible: A Elliptical Traverse of 20th Century Art, in, of and from the Feminine. Edited by Catherine de Zegher. Cambridge: MIT Press, p. 166. [Google Scholar]

- Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg: The Crossing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Sevillano, Ana Belén. 2011. Crisscrossing Gender, Ethnicity, and Race: African Religious Legacy in Cuban Contemporary Women’s Art. Cuban Studies 42: 138–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclare, Rosie. 1999. The discourses of Hysteria: Manopause, art and the body. Hecate 25: 108. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2009. Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolonial Freedom. Theory, Culture & Society 26: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mioscisa, Anunziata. 2000. La cintura: Un simbolo dalla pluralità di significati. Insula Fulcheria 30: 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1984. Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses. Boundary 2 12/13: 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 2003. Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds. 1981. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, Gerardo. 1995. Marta María Pérez Bravo: Self-Portraits of the Cosmos. Aperture 141: 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, Gerardo. 2010. Against Latin American Art. In Contemporary Art in Latin America. Edited by Nikolaos Kotsopoulos. London: Black DogPublishing, p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Papastergiadis, Nikos, ed. 2003. Complex Entanglements: Art, Globalisation and Cultural Difference. London: Rivers Oram, pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Papastergiadis, Nikos. 2017. The end of the Global South and the Cultures of the South. Thesis Eleven 141: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ratton, Virginia. 2007. Central American Women artists in a Global Age. In Global Feminism: New Directions in Contemporary Art. Edited by Maura Reilly and Linda Nochlin. London and New York: Merrell, Brooklyn Museum, p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, Chela. 2000. Methodology of the Oppressed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, Stacy E. 2008. Latin Identity. Reconciling Ritual, Culture, and belonging. Women’s Art Journal 29: 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Seoduherr, Ranjoo. 2014. Recaliming Third World Feminism: Or why Transnational Feminism needs Third World Feminism. Meridians 12: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shoat, Ella. 2016. Diasporic Memories, Taboo Voices. Durnham and London: Duke University Press, p. xv. [Google Scholar]

- Shohat, Ella. 2001. Area Studies, Transnationalism, and the Feminist Production of Knowledge. Signs 26: 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. 2002. Narrativizing Visual Culture: Towards a Policentric Aesthetic. In The Visual Culture Reader. Edited by Nicholas Mirzoef. London: Routlege, p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ussher, Jane M. 2006. Managing the Monstrous Feminine. New York: Routledge, p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, Sayak. 2018. Gore Capitalism. South Pasadena: Semiotext(e). Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Visions, Talking. 1998. Multicultural Feminism in Transnational Age. Edited by Ella H. Shoat. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For this article, I owe very much to Okwui Enwezor, who guided me in my research upon decoloniality and gender issues in Latin America. With this essay I would like to pay hommage to his memory. |

| 2 | Santiago Castro-Gómez. The Hubris of the Zero Point. Quoted in (Mignolo 2009). See Also (Castro-Gómez 2019). |

| 3 | Interestingly, Sayak Valencia consciously retains the term Third World in her discussion of “gore capitalism” in Mexico. She indeed argues to use the term as a geopolitical nomenclature that refers not only to spaces actually located in poor countries but also to peripheries that have emerged in the same physical space of economic superpowers. Cf. (Valencia 2018, pp. 205 ft.4, 219 ft.67). |

| 4 | It is important to reckon here that the essentialism I see as affecting understandings of third world, Latin American, etc., are also given by normative structures of academic papers, books, in which scholars’ positions are universalized rather than presented as problems. |

| 5 | Whitney Chadwick. Women, Art and Society. Quoted in (Kwon 1996). |

| 6 | A.I.R. was the first all women’s gallery in the United States and the Project was actually coordinated by Mendieta, Zarina and Kazuko. Despite the collaborative nature of the project, the exhibition was seen as Mendieta’s personal show, as witnessed by an article in the Village Voice by Carrie Rickey titled “The Passion of Ana” September, 1980. Cf. (Griefen 2011). |

| 7 | Despite belonging to and emerging from a European grand narrative on feminism, I employ here the division in waves to refer to different theoretical approaches commonly acknowledged as such. Cf. Alka Kurian: ‘While feminists would surely not deny that the oppression of women is a matter of international concern, the west has tended to dominate both the theoretical and practical aspects of the movement. The customary division of the history of feminism into “waves” stands as a good example of this, since these categorizations are conventionally organized around American and European events and personalities. Thus, however unintentionally, the “grand narrative” of feminism becomes the story of western endeavor, and relegates the experience of non-western women to the margins of feminist discourse’ (Kurian 1996, pp. 66–79). |

| 8 | Giunta was co-curator with Cecilia Fajardo-Hill of the exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 (which travelled from Hammer Museum, LA, 2017, to Brooklyn Museum, NY, 2018, and finally Pinacoteca de São Paulo, 2018). She is currently curator of the 12 Mercosul Biennale (Porto Alegre, 9 April–July 2020). |

| 9 | This is a general statement, which does not want to consider Latin America as a monolithic country. In Mexico, for example, witnessed a great connection between art and feminist activism. |

| 10 | Diamela Eltit, quoted in (Pérez-Ratton 2007, p. 132). |

| 11 | Cf. Dorothée Dupuis. Anna Bella Geiger. Terremoto. Available online: http://terremoto.mx/article/anna-bella-geiger/ (archived on 10 August 2018). |

| 12 | My emphasis. I am using “waves” here not because I align myself with this kind of methodological division but to silently refer to the problems of such criticism. |

| 13 | For the interpretation of both the title and the symbolism in the composition I have to thank very much scholars Elizabeth Pérez at U.C. Santa Barbara and Kristina Wirtz, University of Michigan. |

| 14 | Griselda Pollock. Vision and Difference. Quoted in (Ussher 2006, p. 164). |

| 15 | ‘The creation of a “firma” is an essential, primary act in a ceremony. These signs are made up of “caminos” or “roads”. A particular firma becomes a vehicle for calling on the spirits or for communicating a sacred act. Firmas can also be combined to communicate more complex meanings. Palo firmas are frequently incorporated into installations, sculptures, and paintings, they can communicate on two levels: as aesthetic drawings and as conded indicators of a special power or identity’ (Bettelheim 2001). |

| 16 | A considerable amount of scholarship have treated issues of social reproduction and women’s labour (see Federici 2014; Dimitrakaki and Loyd 2017). In Caliban and the Witch, Federici aims to rethink capitalism from a feminist perspective, which concurrently overcomes the limits of a “woman’s history”, separated from that of the male part of the working class. Cf. (Federici 2014, p. 11). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).