1. Introduction

Australian Indigenous people promote their culture and country in the context of tourism in a variety of ways but the specific impact of Indigenous fine art in tourism is seldom examined. Tourism, or more particularly cultural tourism, is an interesting context for looking at art because the visitor is already attuned to cultural aspects of place; and that art will help inform them about this (

Smith and Robinson 2006). Indigenous people in Australia run tourism businesses, act as cultural guides, and publish literature that help disseminate Indigenous perspectives of place, homeland, and cultural knowledge. Governments and public and private arts organisations support these perspectives through exposure of Indigenous fine art events and activities. This exposure simultaneously advances Australia’s international cultural diplomacy, trade, and tourism interests (

Whitford et al. 2017;

Tourism Australia 2019). The quantitative impact of Indigenous fine arts (or any art) on tourism is difficult to assess beyond exhibition attendance and arts sales figures. Tourism surveys on the impact of fine arts are rare and by necessity limited in scope (

Frey 2003;

Sayers 1994). It is nevertheless useful to consider how the quite pervasive visual presence of Australian Indigenous art provides a framework of ideas for visitors about relationships between Australian Indigenous people and place.

Fine art is understood as distinct to ‘tourist art’ in this discussion principally in terms of where the art is seen and purchased by tourists. Public art galleries rarely display ‘tourist art’, although one could argue that they do sell it in their gift shops. Fine art alternatively is rarely for sale in airport terminal shops. As Nelson Graburn argues in

Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds (1999) this issue of defining what is and is not fine art is vexed at the best of times. This is particularly complex in the area of Australian Indigenous art, where the visual sign is often inherently multi-functional (

Biddle 1996). There are also historical factors in the evolution of Indigenous art that make distinctions between tourist and fine art difficult.

1 Much Indigenous art in the form of boomerangs and carved artefacts that are now regarded as art were produced across Australia going back to the 1800s under the encouragement of various missions and government-run communities (

Jones 1992). This art production specifically targeted a fledgling souvenir market. Indigenous ‘fine art’ in these circumstances was not acknowledged as a concept, and was often actively discouraged. ‘Tourist art’ in this context became a way for Indigenous people to maintain cultural knowledge under the radar of non-Indigenous overseers who did not understand the significance of visual signs. Tod Jones, Jessica Booth, and Tim Acker’s article on “The Changing Business of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art: Markets, Audiences, Artists and the Large Art Fairs” is particularly useful in considering these art market distinctions in contemporary times (

Jones et al. 2016). The authors argue that the entire Indigenous art output has developed into a relational assemblage involving “goods whose consumption is based around social interactions and relations … and also between Aboriginal art industry insiders and the technologies that support these relationships” (

Jones et al. 2016, p. 107). Most significantly, they add: “Relational goods comprise not just the consumption object in question, but also the sets of relations that objects hold in place” (

Jones et al. 2016, p. 127). There are interesting analogies between the last statement that objects hold sets of relations in place and the interactive relational role of art objects with the semiotic model applied in my research, and discussed forthwith. However, to summarise the point, this article pertains to how fine art is seen by tourists in urban art galleries, remote art centres, and other platforms of display that do not signify ‘tourist art’ as such.

Participatory tourist experiences of Indigenous art are becoming more common but are also beyond the scope of this article because it involves a different kind of looking at art (

Butler 2017a). Aboriginal run organisations such as Arnhemweavers and Bula Bula Arts in the Arnhem Land region of Australia’s north teach visitors over several days an entire process of weaving from sourcing materials through to a final product (

Butler 2018). Aboriginal artists and arts organisations also offer painting classes for visitors, although communities and individuals differ widely in their opinion of whether this is appropriate because of cultural rights to use certain visual signs. These are complex and community-specific issues of participatory artmaking and exceed the focus of this article on how a visibility of Indigenous fine art impacts on the cultural tourism experience. My method of approach adopts a theoretical model of ‘performing cultural landscapes’ to examine how Australian Indigenous art might condition tourists towards Indigenous perspectives of people and place. This differs to traditional art historical hermeneutics that considers the meaning of artwork. In the context of cultural tourism, I am more concerned with how Australian Indigenous art might intersect with a more global cross-cultural semiotic register of cultural landscape. This research is thus not targeted on how Indigenous people themselves derive meaning from their own art, although it obviously draws on this inspiration. The research also acknowledges that Indigenous art produced for a global art market is clearly intended to be in some way cross-cultural. Artists have agency in this decision to reveal aspects of their culture through visual art and are not ignorant of their global audience. I argue that in the context of cultural tourism Australian Indigenous art does not convey meaning so much as it presents a relational model of cultural landscape that helps condition tourists in how to see Indigenous people and place. This mode of seeing involves a complex psychological and semiotic framework of inalienable signification, visual storytelling, and reconciliation politics that situates tourists as invited guests. Particular contexts of seeing under discussion include the visibility of reconciliation politics, the remote art centre network, and Australia’s urban galleries.

2. Performing Cultural Tourism

A method for understanding Australian Indigenous art’s role in cultural tourism requires a shift in thinking from what art means towards art as experience, or even more so, as performance. The academic field of tourism studies quite naturally gravitates towards theoretical analysis of tourism as experience or performance and how such experiences are staged by various stakeholders.

Edensor (

2000) wrote about ‘Staging Tourism: Tourists as Performers’, followed in 2002 by Coleman and Crang’s

Tourism: Between Place and Performance (

Coleman and Crang 2002). This is a field of study drawing on equally emergent fields in geographies, performative aesthetics and tourism psychology (

Adams et al. 2001;

Fischer-Lichte 2008;

Li 2000;

Mignolo 2011;

Stringer and Pearce 1984). Performative models of what cultural tourism is oscillate between literal references to performance in tourism such as in Balme’s ‘Staging Authenticity in Performances for Tourists at the Polynesian Cultural Centre’ (

Balme 1998) to recent, more conceptual, understandings of cultural tourism itself as performance or co-production such as with Carson and Penning’s

Performing Cultural Tourism: Communities, Tourists and Creative Practices (

Carson and Pennings 2018).

Tourism as performance is most useful in the context of cultural tourism studies where it shifts analysis away from the pursuit of meaningfulness towards that of experience (

Li 2000). Experiential knowledge represents a more nuanced form of received knowledge within the tourist encounter where an empirical understanding of what is shared is conditioned by poignant but non-quantitative accounts of impressions, sensations, emotions and a general consciousness of engagement. Carson writes:

As scholars have noted for some time, many tourism sectors now promote co-production, that is an experience in which the visitor takes an active role in producing artefacts or directly engaging with events, as a means by which to access and enhance experiential knowledge. It is clear that today’s tourists want to ‘make’ and ‘do’ as well as ‘watch’.

(ibid., p. 2)

As mentioned previously, visitors are offered opportunities to literally ‘make’ art, but there is also the performative quality of the entire cultural tourism experience. Performative qualities of cultural tourism, particularly where it concerns cultural objects such as visual art, help align the tourism encounter with culture as something always living, interactive and in process, even where it involves a static thing such as a painting. Art theory studies similarly have considered the art object as ‘living’. W. J. T. Mitchell’s study on image theory, called

What Pictures Want? The lives and loves of images (

Mitchell 2005), captures this performative quality of art. Mitchell describes:

The varieties of animation or vitality that are attributed to images, the agency, motivation, autonomy, aura, fecundity, or other symptoms that make pictures into “vital sign”, which I mean not merely signs for living things but signs as livings things.”

When we attend to artworks as living things along with tourism as performance, we begin to understand cultural tourism as something of a dynamic stage where the experience is always contingent, evolving, and perhaps intriguingly uncertain. It is, or at least aims to be, quintessentially engaging, immersive, and intellectually stimulating. Engagement is also what Mitchell attends to when he describes artworks as living things. The artwork is thus characterised as ‘not just a surface but a

face that faces the beholder’ (

Mitchell 2005, p. 30). ‘Face’ as a verb means to confront, challenge, or encounter; all of which implicitly stimulate/animate the beholder.

Place itself is also cast as a performer within this theoretical field of performing cultural tourism. Studies such as Fuchs et.al.

Land/Scape/Theater (

Fuchs and Chaudhuri 2002) fuse the idea of place within frameworks of human geography, artistic constructs of landscape, and the theatrical stage. When tourists encounter this land/scape/theatre, they are potentially guided through it by the performed cultural frameworks of artworks about Indigenous people and place.

3. The Semiotics of Cultural Landscapes

Before further considering how Australian Indigenous art performs cultural tourism, it is useful to take a closer look at recent theoretical approaches to the cultural experience of place. The semiotic concept of a cultural landscape is particularly helpful in understanding place-based cultural tourism and the visual arts. Olga Lavrenova’s

Space and Meanings,

Semantics of the Cultural Landscape (2019) defines cultural landscapes as a geocultural space involving ‘cultural codes expressed in signs and symbols directly connected with a territory and/or manifested in some material expression’ (

Lavrenova 2019, p. 8). The study also models ‘geocultural interactions’, (ibid., p. 2) where sustained views of geographic objects consolidate into culturally significant symbols. Lavrenova does not reference cultural tourism as such, but her concept of cultural landscape semiotics nonetheless provides a systematic explanation for what grounds the place-based appeal and activities of cultural tourism. This is particularly the case where cultural landscape semiotics offers a process where the natural environment becomes an ‘intertext’ made sensible by attributing it signs and symbols that are legible within a culturally cognizant system of signs. Lavrenova describes the process as a ‘physical ungoverned ‘wild’ environment that turns into a sign, gains its fixed place in the world picture, (and) yields to control on a sense level’ (ibid., p. 2); or more simply a ‘dynamic unity of geographic space and human activity’ (ibid., p. 3). We again get the sense of an interactive ‘live’ performance of cultural encounters of place. Mitchell’s approach to art as a “vital sign” seems to align here with Lavrenova’s concept of cultural landscape as a dynamic ‘interext’.

An intertextual process of merging geography with culture is fundamentally ontological in that it helps people define their cultural being in terms of place. Thus, Lavrenova argues that the study of ‘geographic space in literary and visual arts, as well as in folk art, contributes to the reconstruction of deep inside cultural processes’ (

Lavrenova 2019, p. 3). Whilst there is nothing particularly new in the idea that humankind’s sense of being is often determined by a shared set of meanings that link particular people and place, cultural landscape semiotics helps in specifically identifying the elements of the sign system pertaining to spirituality, beliefs, social practice, knowledge, morals, laws, traditions, etc., and how they are passed on through generations, and across cultures. So we can see that cultural signs embedded in the art are potentially triggered when tourists move through a landscape, even though specific symbolic meaning remains elusive.

Lavrenova’s concept of cultural landscape is also useful for understanding the cross-cultural appeal of Australian Indigenous art, and how the art’s mode of semiotics has both a local and global scope. The author approaches culture as ‘an open self-organizing polymorphic system continuously interacting with other cultures, as well as with the environment’ (

Lavrenova 2019, p. 6). This is important because it invokes an inclusivity and open-ness to sign systems that clearly are essential for any pluralistic global society, and global tourism. If tourists are to genuinely engage with culturally different people and places, then a ‘continuously interacting’ open system of signs must be part of the process. The sensory appeal of a place is transformed by culturally coded meanings that are shared through new more globally outward-facing modes of cultural expression (

Servidio and Ruffolo 2016). Australia’s contemporary Indigenous art movement, that emerged in the 1970s as a nation-wide surge of fine art production, was targeted principally for outsiders. Most artists did not trade acrylic canvas paintings between themselves, nor did they keep and display them in their homes. The real art for them, in the contemporary art movement and historically, was the process of making the art to facilitate intergenerational sharing of cultural stories and knowledge (

Biddle 1996;

Butler 2017a). Artworks altered when sold into modified cross-cultural artefacts with a more global purpose. Contemporary Aboriginal art thus participates in a globally inspired open system of meanings, however, the manner in which the art reaches out to others at the same time as it protects its cultural and spiritual integrity, is quite intriguing; and arguably a feature of its tourism-inducing qualities.

4. Inalienable Signs and Invited Guests

Australian Indigenous art involves a dialectic of inviting outsiders’ interest and withholding culturally significant knowledge. The art thus does not involve a totally open system of signs, so how does this work in the ‘intertext’ model discussed above? What in the art actually performs the tourism-inducing qualities? To consider this further, we require some historical understanding of why the contemporary Australian Indigenous art movement emerged. There are obviously many complex reasons why a widespread desire to make commercially saleable art for others took hold in Indigenous communities at a particular time across the nation. However, it is historically clear that the emergence of Indigenous art movements across Australia in the 1970s, and thereafter, coincided with the end of the Australian federal government’s assimilation policy and the first wave of successful Indigenous land rights claims (

Fisher 2016). Rather than having their cultural practices denied or banned (as was the case under the assimilation policy), Australia’s Indigenous people reinvigorated their cultural identities and asserted through art and other means how these identities ontologically involved traditional homelands. Artists adapted traditional cultural coding and semiotics to the new requirements of a global audience, attending to a kind of spectatorship that the linguist, Jennifer Biddle, describes as ‘witness’ (

Biddle 1996). This concept of spectatorship as witness is interesting because it implicates audiences in Indigenous perspectives. Biddle explains how traditional semiotics of Australian Indigenous cultures involves an inalienable system of signs where the meaning of the sign cannot be divorced from the lived experience of its context. Biddle argues that unlike the English language system where the linguistic code can be learnt and applied, the meaning of Indigenous codes involves a contingency of who, what, where, and how, meaning is determined. For instance, the meaning of a circle in an artwork will differ somewhat depending on whether the viewer is Indigenous or not; initiated; and/or depending on age and gender, or even where the circle is viewed geographically. There is thus no essentially stand-alone meaning that can be alienated from the cultural, or indeed geocultural, context from which it derived. Other indigenous cultures of course operate with protocols of restricted knowledge embedded in their concept of secret/sacred knowledge versus publicly available knowledge. Boyd White also considers this within the English language in the context of encounters with artworks in “Private perceptions, public reflections: aesthetic encounters as vehicles for shared meaning making” (

White 2011). However, as Biddle argues, cultural restrictions on certain knowledge are far more closely guarded in Australian Indigenous and other First Nations oral cultures.

Biddle argues that in the new cross-cultural context of the Indigenous acrylic painting art market, the inalienable system fundamentally inhibited the full dissemination of meaning and thus retained the authority of the sign for those designated by traditional cultural protocols. But within the context of the contemporary art movement, inalienable signs underwrite a complex process of cross-cultural communication (

Cheer et al. 2017). Outsiders’ attention is drawn to the culture by art made specifically for them, but the full capacity to understand its meaning is withheld (

Biddle 1996;

Butler 2017b). Bright acrylic colours and stylized geometric patterns first caught the eye of mid-20th century art enthusiasts. But one might ask how this withheld meaning can actually promote genuine cross-cultural understanding, or in turn, any cultural tourism appeal? Another study about Indigenous hermeneutics helps to understand the concept of ‘witness’ spectatorship from another perspective. In his study of Kuniwinku Indigenous art from northern Australia’s Arnhem Land, Luke Taylor approaches this complex semiotics from perspectives of outside and inside meaning, perhaps better understood as public and private meaning (

Taylor 1996). Those without cultural rights to the deeper inside meanings are still entitled to outside meanings that convey cultural stories about particular people and place. One might argue that in the outward-facing global art market, Indigenous art exploited and expanded its capacities for public meaning and thus encouraged engagement with Indigenous cultures whilst maintaining the internal integrity of traditional semiotics.

It is interesting that Lavrenova’s cultural landscape semiotics similarly refers to a hierarchically organized system of codes (5) where primary sign systems deal with specific meaning and secondary sign systems use various formal and material means for coding the same content resulting, in general, in a ‘world picture’ or the worldview of a particular social community. (5) In the cross-cultural space of the global circulation of contemporary Australian Indigenous art, there seems to have been an intersection between the polyvalent yet hierarchical systems of signs where some kind of culturally-determined experience of place, is shared. Lavrenova’s reference to worldview is perhaps what is being performed for outsiders in the Indigenous art. The cultural landscape for tourists is a public view or eye-witness experience of Indigenous cultures and country. If we are to believe in a concept of cultural tourism where something is genuinely shared, and that the cross-cultural encounter amounts to more than an opportunity for voyeurism, then something within the art, and other cultural practices, is triggering intellectual or emotional engagement (

Gibson 2012).

5. Tourism and Reconciliation Politics

The internal cultural politics of Indigenous epistemologies discussed above clearly impact on how tourists are encouraged to engage with the art, but so too does the socio-political context of art production. Indigenous culturally significant symbols inherently absorb the socio-political realities and histories of Indigenous experience. Contested histories, land rights, human rights, and fundamental issues of social equity, are just some of the socio-political and cultural issues concerning Australia’s Indigenous population. Much of Australian public consciousness recognises the need to address these problems under the terms of

Reconciliation Australia, a not for profit organization run by Indigenous people.

2 Reconciliation politics is a term that has broad resonance with Australian Indigenous experience, but also links Indigenous Australians to other First Nation causes around the world. Most tourists would understand some form of potential reconciliation aspirations in Indigenous art that is produced for outsiders. The quite confrontational work of artists such as Vernon Ah Kee and Richard Bell,

3 or Jason Wing (

Vaughn 2018) is decolonising in its redress of how the history of Indigenous Australia has been told and in continuing social injustice and racial stereotyping. Indigenous commentators such as Deborah Bird Rose have consistently linked the need for decolonisation as a necessary step in any potential reconciliation (

Rose 2002).

There is also considerable global interest in relationships between cultural tourism and reconciliation politics. Courtney Knapp’s 2018 study of racial politics, public spaces, and cosmopolitism in Chatanooga Tennessee, included a chapter titled ‘Public Space, Cultural Development and Reconciliation Politics in the Renaissance City’ (

Knapp 2018). Knapp demonstrated the complex interplay between place, art, and cultural tourism in a case study of a public revitalization project involving Chorekee First Nation stakeholders. In this instance public art installations play a major role in the reconciliation narrative invested in a central urban revitalisation plan, which was partly designed to attract tourists.

It is clearly impossible to divorce the cultural aspects of Australian Indigenous art from its inherent postcolonial politics, and nor would anyone who is really interested in culture want to. Art is the most visible aspect of Indigenous culture across the nation, and it is everywhere. International tourists see it on promotional videos entering the country, in airports, hotels, shops and restaurants, and on television. The art also has a strong mass media presence. Politicians and corporate leaders are often filmed speaking to camera with strategically positioned Indigenous artworks in the background. This visibility shifts between performing a kind of national branding (

Anholt 2003) to an implied acknowledgement of Indigenous Australians, however the complexities of this issue are beyond the scope of this topic on cultural tourism. The reasons for the art’s visibility may often be quite shallow and opportunistic, but the fact is that the art can be seen everywhere in Australia. For tourists it performs a visual Welcome to Country (an Indigenous term for inviting outsiders onto one’s homeland), but what exactly constitutes that ‘welcome’?

Marcia Langton’s 2018 publication titled

Welcome to Country,

A Travel Guide to Indigenous Australia is quite insightful in this regard (

Langton et al. 2018). Langton has been a prominent Indigenous activist since the 1970s and a leading academic and author in Indigenous studies. So when Langton offers a Welcome to Country, it is from a very considered political and cultural perspective. Langton’s book is the first extensive travel guide written by predominantly by an Indigenous author but also follows Mick Dodson and other Indigenous contributors to Peter Kauffman’s book titled

Travelling Aboriginal Australia (2000) (

Dodson 2000). Art centres are mentioned in Kaufmann’s text in the second part of the book devoted a state-by-state guide to Indigenous destinations, similarly to Langton’s text. However, Langton’s book goes much further in providing Indigenous perspectives that includes introductory essays explaining legal and political aspects of Indigenous land ownership and colonial history; cultural customs and protocols, language, art, and storytelling; and outlines a tourism etiquette for interacting with Indigenous people and visiting Indigenous communities. As mentioned, the second part of the book is a directory to Indigenous tourism places, events, and experiences indexed by location. It is thus essentially a welcome to country on Aboriginal terms. As previously mentioned, Langton is a prominent Indigenous cultural theorist and a well-known political activist, so when Langton writes a book titled

Welcome to Country it has Australians’ attention because it is perhaps not a title that they would expect her to put forth. However, the book and its references to art are one of the most significant statements about cultural tourism from an Indigenous perspective that we have to date. It is designed as a guide for tourists in how to engage with Indigenous culture, but it is also a guide to Indigenous protocols and a history of injustice and inequality. The book thus feeds into current reconciliation politics and presents it as an integral part of Indigenous cultural tourism in Australia.

The synthesis of reconciliation politics, visual storytelling, and inalienable signification works obviously in very different ways in given artworks. Sometimes, such as with the art of many Indigenous artists from urban centres, the art is overtly political, the visual story confronting, and the signification is more explicit (revealed) than concealed. Artists such as Richard Bell, Vernon Ah Kee, and Fiona Foley are examples. These more overtly political artworks operate in cultural tourism as symbols of Australia’s unresolved reconciliation politics, and decolonise historical narratives that dispossess and displace the Indigenous population. Other artworks use traditional iconography that in the past appeared in body painting, ceremonial ground painting, on cultural objects, and in rock art. When transferred to canvas painting, many of these symbols create a cultural map of place and embody a visual story of sacred sites known variously in different areas as Songlines, Dreaming tracks, or Storyplaces, among many others (

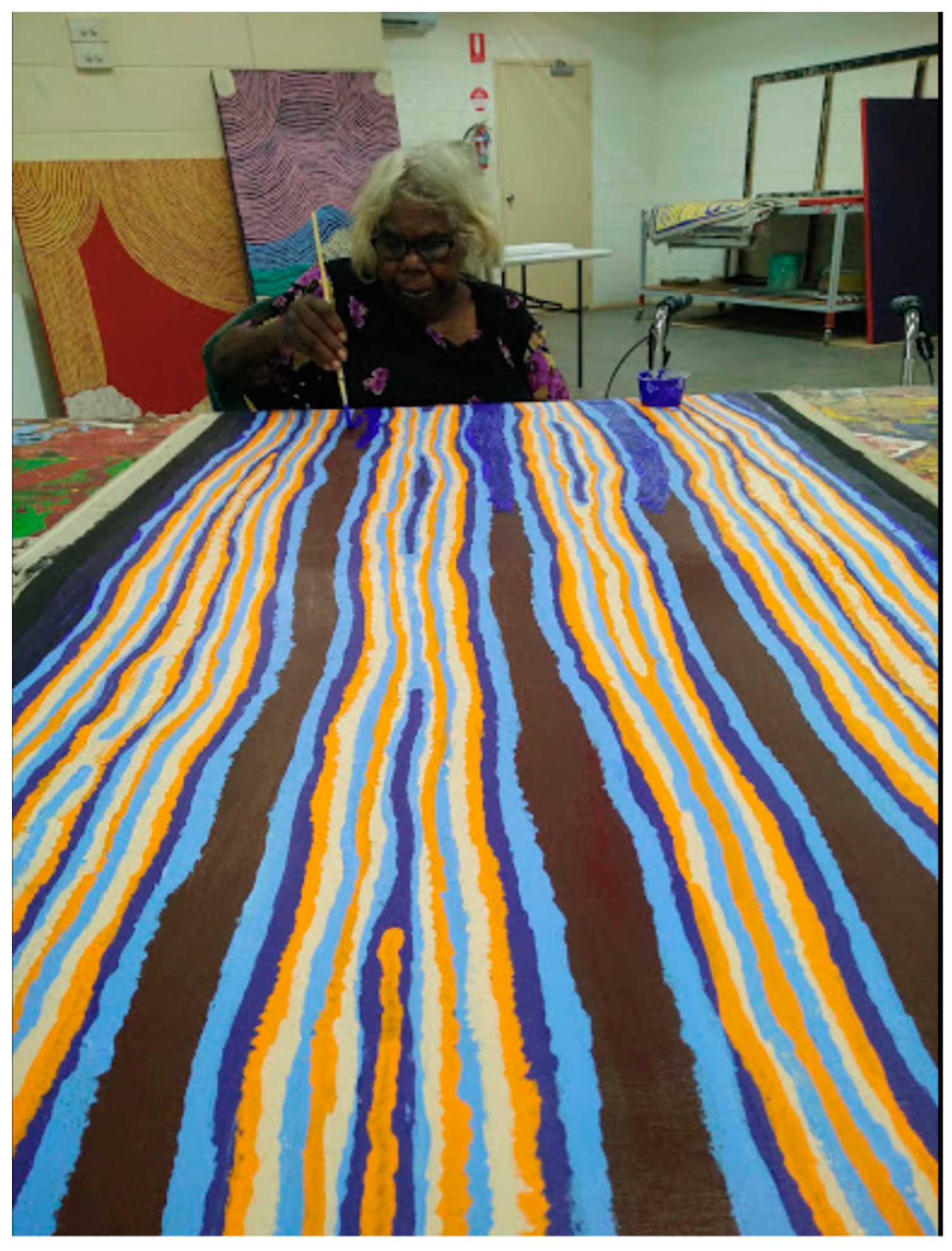

Beckett et al. 2008). And there are the artworks that work on a more subtle level, and these are arguably the most appealing to tourists because they seem to oscillate between western and non-western artistic styles. Or perhaps we could refer to them as a high-functioning ‘intertext’ using Lavrenova’s term. Alice Nampitjinpa Dixon’s (b. 1943) series of

Tali Tali (or Sandhills) paintings is an example (see

Figure 1.) (

Dixon 2016). To a western art-trained eye, the paintings appear to be a form of soft-edge op art, like Bridget Riley without the hard-edge precision. However, precision in Dixon’s imagery comes from another source. The paintings more or less perform linear sand hills where the artist was born, and where she travelled many times. Vast kilometres of remote sand hills (also called sand ridges, linear dunes, or longitudinal dunes), feature in Australia’s central and western deserts. They can be hundreds of kilometres long and between ten and several hundred kilometres wide. Their crestlines in country west of Alice Springs, where Dixon was born, are remarkably straight rather than sinuous. These sand hills are the most startling and spectacular introduction to Central Australia when tourists fly into, or over, the region. One could argue that the aerial vision of these sand hills fundamentally characterise the experience of the Central Australian geography, even if tourists do not travel to, or through, the sand hills.

Dixon’s Dreaming stories and her personal history are about navigating these hills and knowing how to survive many weeks, and possibly months, in their ecosystem. The vivid colours of Dixon’s paintings are not representational of geographical colours but of mood and emotional intensity. At sunrise and sunset it is an intensely vivid and coloured landscape, and in the midday sun it is simply mesmerizing. Dixon captures this spirit of place in her paintings, and it is a beautiful initiation for tourists in how to love one of the most remote and apparently harsh parts of the planet. However, to return to Mitchell’s ‘living’ image concept, these paintings also strive for the aura or fecundity of a living country, a living culture, and a living art. The paintings have a face that confronts us, and thus perform cultural tourism across significant cultural differences. The act of creating these paintings, and selling them to outsiders, is an expression of land rights to the artist’s traditional homelands, and an invocation of Biddle’s concept of ‘witness’. Outsiders and tourists become witnesses to the artist’s authority over the cultural landscape of particular sandhills and their stories. Tourists to the region, and viewers of the art, thus become invited guests to the cultural landscape synthesising reconciliation politics, visual storytelling, and inalienable signification.

6. Remote Art Centre Networks

Langton’s aforementioned

Welcome to Country travel guide includes a reference section to Indigenous art centres located across most of remote and urban Australia (

Riphagen 2016). These art centres are pivotal in Indigenous cultural tourism and also effectively synthesise the reconciliation politics, visual storytelling, and inalienable signification informing the Indigenous art experience. The art centres operate in quite different models, but most have a gallery or shop that invites direct purchase of artworks. Artists are often working in the art centre and are happy to interact with visitors, whilst in other art centres the studio is kept quite separate to visitor access. A video documentary produced in conjunction with artists from Warlayirti Artists in Balgo (

Warlayirti Artists 2019), one of the country’s most remote art centres, is particularly insightful regarding relationships between Indigenous art, people and place; and why art centres are, or can be, significant tourist attractions.

Painting Country was created in 2000 on location in the remote north of Western Australia. The documentary is essentially a story about visual storytelling and how the canvas paintings map spatial, cultural, spiritual, and political journeys of the artists. A select number of artists from the art centre elect to go on a painting road trip to traditional homelands hundreds of kilometres from the community, where many have not visited since childhood. Along this journey, the video provides insight about how the art embeds memories of kinfolk, ceremonies and sacred sites. It also conveys memories of atrocities, massacres, and displacement perpetrated on the Indigenous population. Cuts between aerial footage of the landscape and elements of paintings illustrate the symbolic, abstract and naturalistic representation of Country in the paintings. We listen to cheeky banter between a husband and wife about their early courting days, and are gripped by the emotional experience of an elderly male artist crying for country. Trees, hills and waterholes are identified in the landscape as geocultural markers of different Dreaming stories and journeys and thus the determinants of customary law-determined rights to certain land.

The following commentary on

Painting Country is quoted below at length because of how it demonstrates the

witness dimension of performing cultural tourism as experienced through art (

Ingleton 2000a):

The artists are able to recall landmarks with incredible accuracy and clarity, and for the audience there is a momentary glimpse into an Indigenous perspective of the land. Suddenly, land that may be seen by an outsider as rather obsolete and without familiar symbols, comes alive, and the way the artists inhabit the land as a Westerner would a house, becomes the primary focus of the film. The joy of the elders being returned to country, or the recounting of past food gathering expeditions is the essence of the art itself, and we begin to see that it is the artist’s life and cultural inheritance of wisdom and knowledge that is the basis of such beautiful works.

This film provides a good example of the non-linear notion of time as understood by Indigenous peoples. For example, the personal life stories of the individual artists overlap with the Dreaming stories of the Ancestors and these are re-created within the art. The idea of past and future are imbued within the present, and all narratives—past and future—are woven together through the relationship to land as represented in the artwork.

This road trip is an Indigenous perspective akin to Lavranova’s semiotics of cultural landscape writ large across an immense scope of Australian Indigenous experience and creative expression. Not all tourists are fortunate enough to participate in artists’ road trips such as this, however some dimension of the experience occurs when tourists drive to art centres, and really engage with the art experience, the people, and their place.

7. Urban Galleries

For those tourists not visiting remote Australia, many still encounter Indigenous art whilst visiting public and private galleries, art fairs, and cultural events held in Australia’s urban locations. Public art galleries play a particularly important role in performing cultural tourism (

Lippard 1999;

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998), and portray visual stories about Indigenous art through techniques of exhibition display, information labels (didactics), and public programs. Methods of display, the selection of artworks, juxtapositions of artworks, curatorial themes, and information labels, all contribute to a museum mode of visual storytelling that impacts on tourists’ consciousness of Indigenous Australian cultures. Public galleries all have mission statements that set out the intellectual and cultural framework for how a gallery represents a particular national, state, or regional community. The gallery’s permanent collections and the manner in which they are displayed convey to visitors a story about that community’s people and place. Valerie Casey regards museum’s storytelling as a form of staging or performance, and in this sense, museums are also performing cultural tourism (

Casey 2005).

Indigenous art is today a very significant aspect of Australian art history, to a degree far in excess of their less than 3% representation in the national population. Galleries are aware that decisions made in display of Indigenous art must demonstrate respect for Indigenous cultures, an ethics of representation, and a geocultural mapping of Indigenous Australia (or what Lavrenova would call a cultural landscape). In this way, public galleries synthesise reconciliation politics, visual storytelling, and inalienable signification into a visitor experience of Australia’s Indigenous cultures. The National Gallery of Australia and all state art galleries have permanent collections of Australian Indigenous art displayed in ways that demonstrate the broad diversity of Australia’s Indigenous cultures as well as mixed displays reflecting Indigenous peoples’ (often assimilated) contribution to a national narrative. Such integrated displays of Australian art are perceived variously as either a story of Indigenous assimilation into a post/colonial Australian narrative, or as having a decolonising impact on that narrative. Either way, from a tourist’s perspective, the national narrative is uncertain and ambiguous, as it should be. Reconciliation politics is about unresolved treaties and contested sovereignty, so any combined Australian visual story is far from resolved.

One particular public gallery has recently confronted this issue of the national storytelling in a radical manner. The Queensland Art Gallery is that state’s public gallery and confronted this issue of how to narrate the visual story of Australia in a major re-hang of its permanent Australian collection in 2017. The re-hang is officially themed as Reimagined Australia

4 and presents a thematic, rather than chronological, approach to Australian art. The display basically juxtaposes Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian art along with the work of expatriate artists and some international artists who have worked in Australia. Australian art displays usually begin with early colonial art and then proceed through 19th, 20th, and 21st century iterations. This chronology implicitly denies the circa 60,000 year presence of Indigenous Australians and privileges a colonial/postcolonial teleology. QAG’s rehang is instead a story of Australia reimagined in a global cross-cultural context and attempts to broaden the framework of Australia’s cultural landscape. The QAG blog states its aims quite clearly:

In drawing together artworks from different times and across cultures, this new display traces narratives of geography, country, landscape, and the places we live and work. It also tells stories of journeying and encounter, immigration, colonisation and the expatriate experience.

5

Gina Fairley, in a review of the rehang, explains the importance of reshaping the Australian cultural landscape for tourists:

There is great responsibility in hanging a collection of Australian art in a state art gallery. For many visitors, it might be the first introduction that they have to Australian art, especially if visiting from another country, so getting that story right is critical.

Similarly to other public galleries, QAG supplements display of the Australian permanent collection with an ongoing program of special exhibitions profiling the diversity of Indigenous art across the country. Exhibitions such as

Storyplace,

Indigenous art of Cape York and the Rainforest (2003) work to break down cultural stereotypes that tourists often have in believing that all Australian Indigenous art involves dot painting on canvas.

6 Storyplace was particularly effective for Australians and international visitors in conveying rainforest cultures of Queensland’s far north and their capacity to tell sacred and secular stories about particular people and places in that region.

8. Conclusions

This research attempts to understand how a surface level of meaning in tourists’ encounter with the visibility of Australian Indigenous art has an impact on appreciating Indigenous perspectives of their people and place. If we truly believe in visual communication and that images convey ideas without the necessity of explanatory text, then the performance of visual art in tourism is significant. I approach this problem by adopting a semiotic model of cultural landscape that configures the art’s visual reference to people and place as an ‘intertext’ or a stage that brings certain contexts of looking at art together as a performance. Looking at art in this context is thus more about activating and orchestrating the context of looking than about processing information towards logical conclusions of meaning. It is a model of contextual responsivity that guides or conditions more than it informs.

The article is exploratory in terms of contexts chosen to consider the impact of the art. I took the approach that in general non-Indigenous people are influenced by what Indigenous people say about their culture; they understand the socio-political impact of colonisation on all First Nations people; and they are aware that full understanding of an artwork or culture, particularly in the context of tourism, is impossible. I could have chosen different contexts such as Indigenous music, or television advertising, and different sites for looking at art beyond remote art centres, urban galleries, and the visibility of art in reconciliation politics. I chose these because I believe that they are a scaffold for a broad scope of the tourist encounter with Indigenous art. More research into how and when art is encountered and experienced will help broaden understanding of art beyond traditional frameworks of interpretation that generally lack appeal for all but the most devoted cultural tourists. We do organise our experiences of people and place into some kind of order, and visual art plays a role in prompting how we do this. This article attempts to explore this prompt in a preliminary semiotic manner, more as a test case of the model than as any systematic semiotic analysis. Lavrenova’s theory of performing cultural landscape; the performative turn of tourism studies; and WTJ Mitchell’s activation of the image as something ‘live’; are the methodological intersection of this research that helps in considering the conditioning role of art.

Many scholarly publications deal with the need for an ethical relationship between the tourism industry and Indigenous communities. At the same time, we are experiencing an increasing amount of literature on the desire by Indigenous communities to diversify their employment and income streams through the tourism industry. We are well served to understand the complexities of art’s appeal to visitors in advancing cultural tourism that is mutually beneficial to both hosts and visitors. This requires a great deal more consultation and collaboration with those communities, and it appears that they are ready to accept outsiders in this context as invited guests.