Abstract

Late antiquity witnessed the increased construction of synagogues in the Jewish diaspora of the Roman-Byzantine world. Although not large in number, these synagogues were impressive and magnificent structures that were certainly conspicuous in the urban landscape, especially when constructed within a central location. This paper focuses on mosaic carpets discovered at these synagogues, to discern their distinguishing features through a comparative perspective. Two focal points are examined: on the one hand, local Roman-Byzantine mosaics in civic and religious buildings, and on the other hand, Jewish mosaics carpets in Palestinian synagogues. This comparison reveals several clear distinctions between the Jewish diasporic mosaic carpets and the other two groups of mosaics, that broaden our understanding of the unique nature of Jewish art in the Roman-Byzantine diaspora in particular, and of Jewish diasporic identity in late antiquity in general.

The artistic remains from late antique synagogues are rich and fascinating: most were discovered in dozens of Palestinian synagogues, in stone carvings and mosaic carpets. In this article, I will examine a smaller and less explored branch of this art: that of the Diaspora synagogues, built outside of the provinces of Palestine and Arabia, with a focus on the medium of mosaic carpets.1 Uncovered in archaeological excavations, these synagogues comprise an extremely small group of buildings—15 in all (as opposed to about 120 synagogues uncovered in the Land of Israel). Aside from the frescoes of the Dura Europos synagogue that are continually studied,2 the artistic remains from Diaspora synagogues have naturally received less attention than those from Palestinian synagogues. However, it bears noting that the scant number of synagogues in no way reflect the dimensions of the late antique Jewish diaspora in the Roman-Byzantine sphere. Epigraphic evidence and historical sources attest to the existence of hundreds of communities, and afford us a broader, more precise picture.3

Archeological excavations revealed Roman-Byzantine diasporic synagogues from Dura Europos on the Roman Empire’s eastern frontier, to Elche in Spain in the west. They were constructed from the 1st century BCE (Delos)4 until the 6th century CE (Hammam Lif), although most were constructed or renovated towards the end of the period, between the 4th and 6th centuries. In many respects, there is a pronounced diversity within this group of buildings: some synagogues—such as Hammam Lif and Kelibia in Tunisia and Elche in Spain—have small prayer halls that contrast with the spacious prayer halls in Ostia in Italy and Sardis in Asia Minor. Some of the synagogues in this group—Apamea in Syria, Sardis and Andriake in Asia Minor and Plovdiv in Bulgaria—were erected in central locations within the city, while others such as Ostia, and Priene in Asia Minor, were built on its periphery.5 Additionally, the group exhibits diverse architectural plans differentiated by the design of the prayer hall, the position of the Torah shrine and the entrances, and the use of water installations.6 Artistically, however, a noticeable similarity inheres between most of the structures, manifested in colorful mosaic carpets installed in the prayer halls and, at times, in adjoining rooms.7 This paper will focus on the mosaic carpets through which I will attempt to characterize Jewish visuality in the Roman-Byzantine diaspora, and its contribution to a better understanding of Jewish diasporic identity. A brief depiction of several mosaic carpets will preface this discussion.

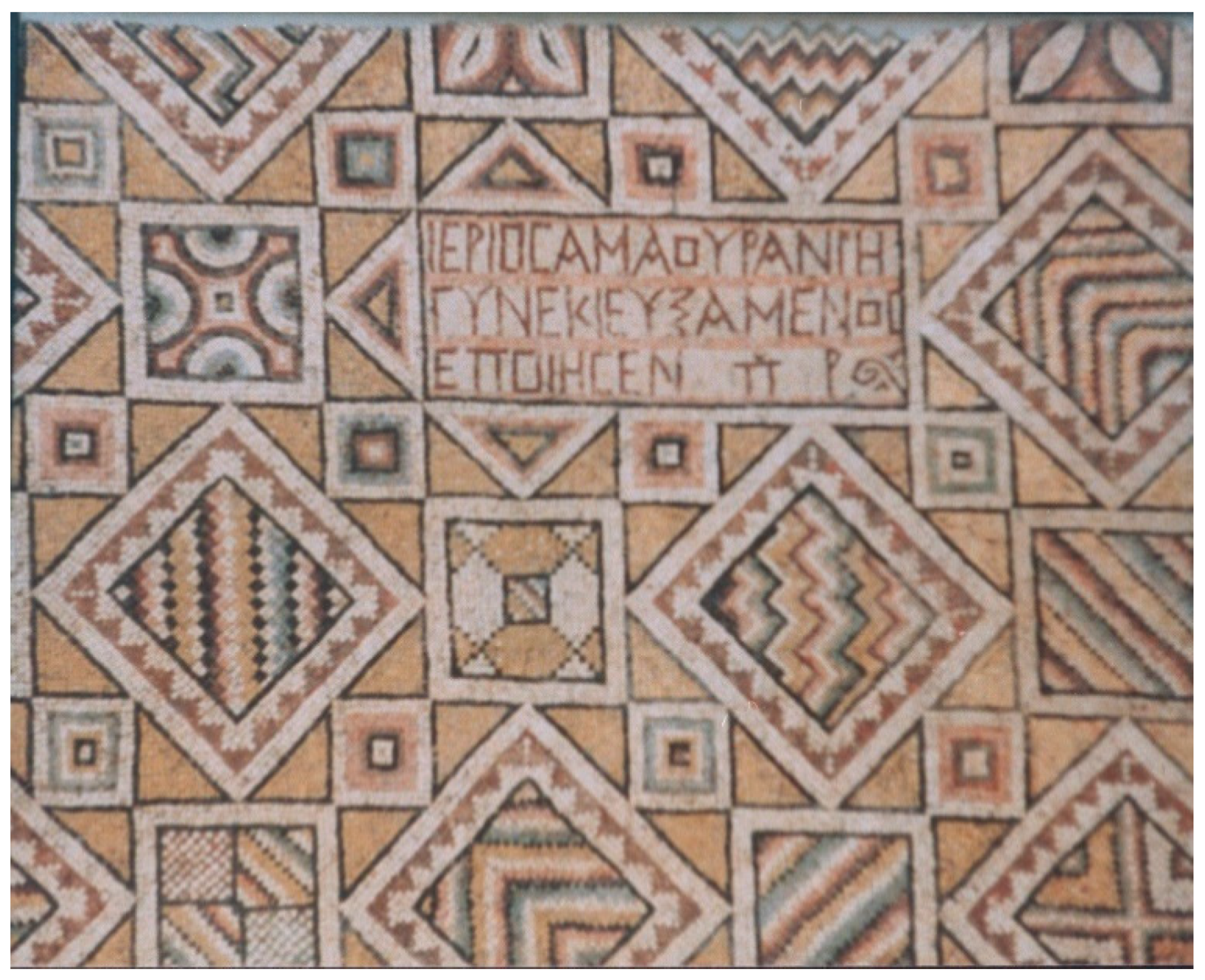

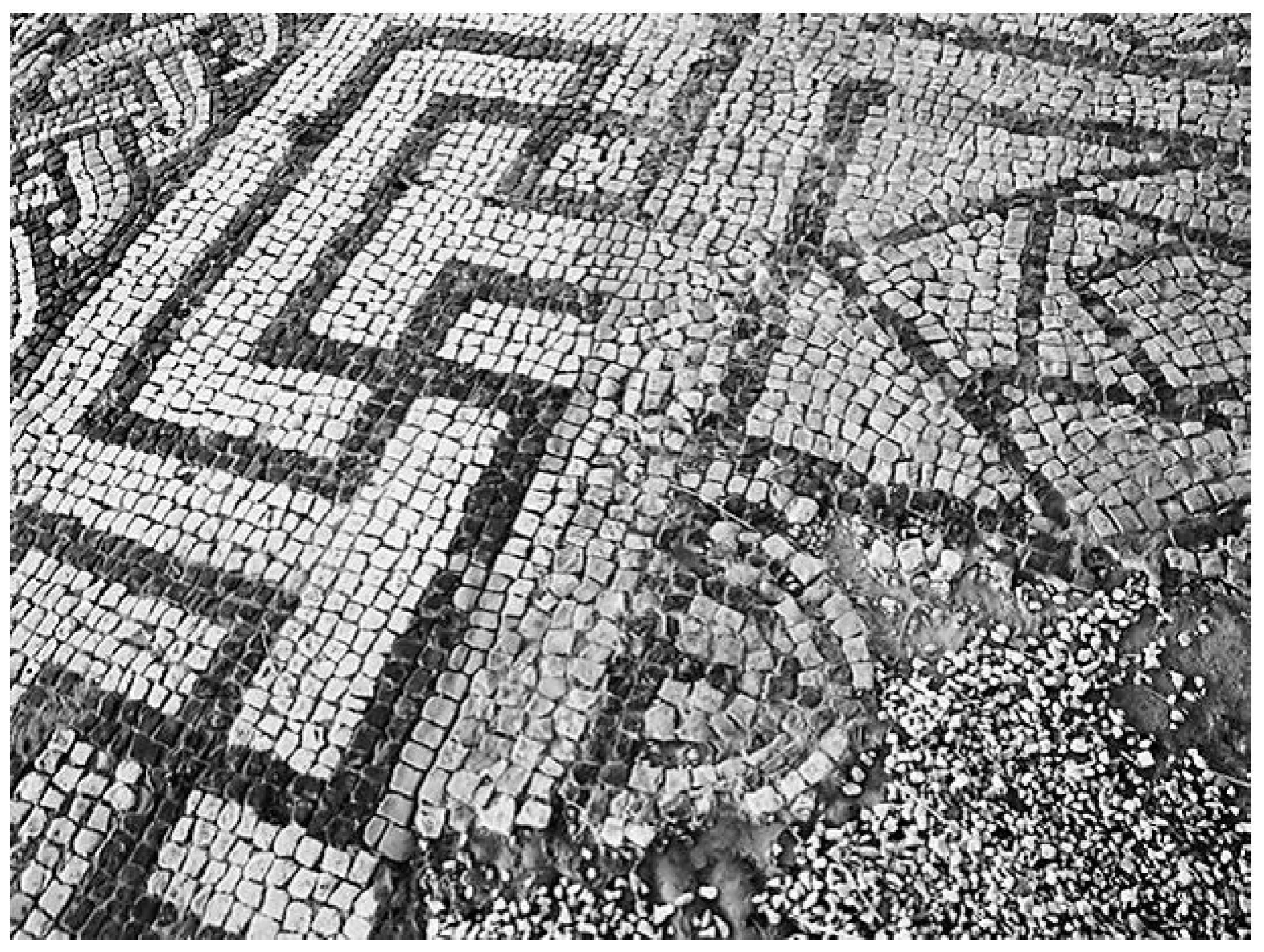

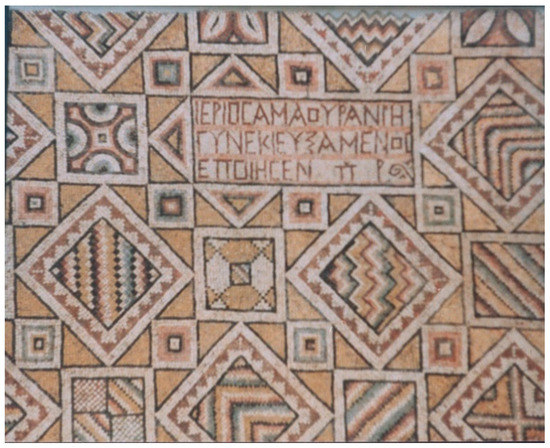

In 1934, in the city of Apamea, the Mission Archaeologique Belge revealed an ancient synagogue, built adjacent to the Cardo Maximus, the city’s main street. The synagogue’s prayer hall is built along a north–south axis, and the Jerusalem-oriented southern wall features a square niche for the Torah shrine. The mosaic carpets that adorned the prayer hall were uncovered in their entirety and they extend over an area of 120 sq. m. The mosaics consist of a central mosaic carpet with a north–south orientation, including two panels bounded by a decorative frame, and eight smaller carpets surrounding the central mosaic carpet from north and west.8 The mosaics incorporate 20 dedicatory inscriptions mentioning the names of 20 donors: 13 women and seven men.9 Two inscriptions record the date of the mosaic carpet’s installation: 392 CE.10 The mosaic features diverse geometric and decorative patterns, some of them manifest in a three-dimensional quality typical to contemporary Syrian mosaic art (Figure 1).11 The prayer hall’s southwestern carpet includes a central medallion containing a dedicatory inscription, surrounded by an octagon resting on eight outward facing squares. A small menorah occupies the space between the two southern squares: this is the only religious symbol in the mosaic carpet (Figure 2).12 The synagogue at Apamea serviced the community only very briefly: the building was abandoned as early as 415–420 CE and a church, known as the Atrium Church, was built above it. The well-preserved state of the synagogue’s mosaics attests that the building’s conversion to a church did not entail their destruction. The synagogue floor was apparently covered over and repaved with a new floor.13

Figure 1.

Mosaic carpet in the prayer hall, the synagogue at Apamea, Syria, 392 CE. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Figure 2.

Mosaic carpet in the prayer hall with a menorah, the synagogue at Apamea, Syria, 392 CE. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The synagogue at Bova Marina in southwestern Italy was discovered accidentally during the eighties of the previous century. The excavators identified two phases in the synagogue: the first following its construction in the 4th century, and the second in the wake of a renovation conducted during the 6th century. The synagogue is located within a complex of rooms whose purpose was not necessarily related to the synagogue. The 6 m × 7 m prayer hall is constructed along a north-west/south-east axis and is accessed through two entrances, on the north-west and south-west walls. Within the complex, only this hall was paved with a mosaic floor; although it has not survived in its entirety, its outline can be fully reconstructed. The mosaic is divided into sixteen 1 m × 1 m square units, bordered by a guilloche pattern. Laurel garlands populate the squares at the center of which are alternating rosettes and Solomon knots. The northwestern row consists only of semi-squares populated by rosettes. An outer frame of laurel leaves surrounds the entire mosaic floor. The second unit from the right, in the third row from the northwestern entrance, is exceptional: a black contour that frames a menorah resting on a tripod base replaces the garland; oil lamps top its seven east-facing branches. The menorah is flanked on the right by a shofar and lulav and on the left by a citron (=ethrog).14 As the mosaic carpet’s composition lacks a central axis (that would require an odd number of vertical rows), the menorah is not at its precise center—facing the estimated position of the Torah shrine on the southeastern wall: rather it tends somewhat southwards. During the synagogue’s first phase, before the construction of the apse and bima, the menorah indicated the building’s southeastern orientation.15 During the early 6th century the building was renovated: the prayer hall was expanded towards the southeast and a bima was built in the new space. An apse was added in the southeast wall. A new decorative mosaic panel, of inferior quality, was installed between the bima and the edge of the old mosaic carpet.16 The synagogue and the entire settlement were abandoned in the wake of outbreaks of violence at the turn of the 7th century. Traces of fire found in the prayer hall attest the synagogue’s fate.17

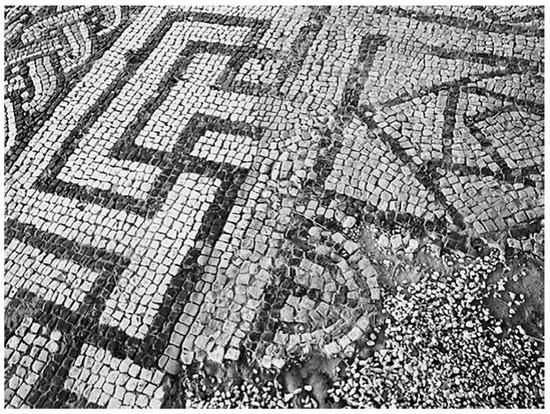

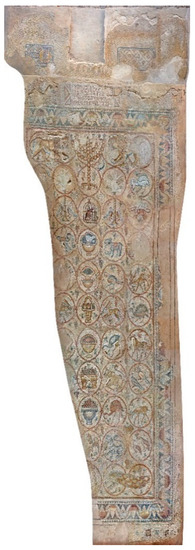

The excavations at the ancient city of Sardis in southern Asia Minor revealed a synagogue that is the largest of all ancient synagogues known to this day. The building, located in the southern part of a Bath-Gymnasium complex, had been converted into a synagogue in the late 3rd or early 4th century.18 The synagogue housed a spacious 18 m × 54 m prayer hall with an apse at its western end. A forecourt with a fountain fed by underground pipes at its center led to the prayer hall from the east (Figure 3).19 During the 4th century, the entire prayer hall, as well as the roofed areas of the forecourt was paved with mosaic carpets, some of which were repaired or replaced during the 5th and 6th centuries. The mosaic carpets feature decorative and geometric patterns that incorporate dedicatory inscriptions. They contain no religious or ritual symbols, nor figural images, aside from two zoomorphic figures that had been displaced from the apse mosaic in the course of iconoclastic activity (Figure 4).20

Figure 3.

A fountain in the center of the forecourt, the synagogue at Sardis, Asia Minor, 4th–5th century. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Figure 4.

Mosaic carpets in the prayer hall, the synagogue at Sardis. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

However, the mosaic carpets do not comprise the entire synagogue décor: a range of artistic techniques was utilized to decorate the various areas of the building. The synagogue can only be appraised by examination of its art as an entirety: the lower part of the prayer hall’s walls were decorated with polychrome opus sectile that included engraved pieces of marble and marble pieces cut in various patterns, among them several zoomorphic depictions.21 A pair of marble sculptures—each engraved with a pair of back-to-back lion—as well as a marble table with an eagle engraved upon each leg was utilized in secondary use within the prayer hall.22 Two aedicula on masonry platforms flanking the main entrance to the prayer hall in its eastern wall, as well as numerous depictions of religious symbols, most notably the menorah, reflect the building’s function as a Jewish house of prayer.23 The artistic remains of the Sardis synagogue present therefore a complex picture whose significance will be addressed in the continuum. The synagogue was abandoned in the wake of the Sassanid conquest of the city in 616.24

The ancient synagogue in the Albanian city of Saranda will complete this brief survey. The synagogue is located in a complex of rooms in which excavators identified five phases of activity during the Late Roman-Byzantine period. Phases 3–4 correlate with the synagogue’s activity during the 5th–6th centuries and perhaps even earlier. A north–south oriented hall decorated with a rectangular mosaic floor that includes various geometric patterns presumably appertains to the synagogue’s first phase (Phase 3 of the site). The carpet’s central panel contains a menorah, a shofar and an ethrog, prompting excavators to name it the ‘Menorah Hall’ (Figure 5). An additional mosaic floor, adjacent to this carpet in the east, portrays an amphora from which protrudes a bush with foliage and possibly a figure of an animal as well.25 In its second phase, the synagogue functioned in an east-oriented basilica structure, with a mosaic carpet adorning the nave. Three architectural facades—or perhaps aediculae—arranged vertically, one atop the other are depicted in the mosaic. The eastern one attached to the bima is best preserved: a pair of birds is discernible adorning both sides of the gable. Additional images in the carpet include an amphora surrounded by zoomorphic figures, trees encircled by animal pairs and interlaced medallions inhabited by birds and flowers.26

Figure 5.

Jewish symbols in the mosaic carpet of the ‘Menorah Hall’, the synagogue at Saranda, Albania, 5–6th century. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

This brief overview suffices to demonstrate the prominence of geometric and decorative patterns in the mosaic carpets and, conversely, the proportionally small amount of figural images. Of all the mosaics in Diaspora synagogues, zoomorphic images are most prevalent at Saranda; they appear also in the mosaic carpets at Hamman Lif and Kelibia in Tunisia. Conversely, the decorative plans of the mosaic carpets at Apamea, Aegina, Plovdiv, Stobi, Bova Marina and Ostia are completely aniconic. Moreover, anthropomorphic images have never been discovered in any of the Diasporan synagogue mosaics—certainly not images affiliated with the pagan world.27

An additional phenomenon that warrants consideration is the presence of religious symbols—the menorah, lulav, ethrog and shofar, in the mosaic carpets.28 These symbols—especially the menorah, occur in most of the carpets, although with varying degrees of prominence and conspicuity. At Plovdiv a monumental menorah appears on a 3.8 m × 3 m panel, flanked by the four species (Figure 6).29 At Saranda and Bova Marina the menorahs (and the symbols flanking them) are conspicuous because of their central position in the carpet and their occurrence in an independent unit, whereas at Apamea and at Hammam Lif the menorahs merge with the carpet’s decorative scheme and are thus much less prominent.30 Recently, Robyn Walsh argued that the mosaic at the Elche synagogue incorporated a small menorah depiction, thus dispelling some scholars’ doubts regarding the structure’s Jewish identity (Figure 7).31

Figure 6.

A huge menorah, flanked by the four species, in the mosaic carpet of the prayer hall, the synagogue at Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 4th century. Courtesy of the Regional Archaeological Museum, Plovdiv.

Figure 7.

A small menorah integrated in the geometric patterns of the mosaic floor, the synagogue at Elche, Spain, 4th century. Photograph courtesy of Robyn Faith Walsh.

This said, Ostia and Sardis demonstrate that the absence of religious symbols from the mosaics does not ensure their absence from the entire décor of the building: an engraving of the menorah, together with a shofar and the four species, adorns two supporting corbels on the façade of the apsidal aedicula at Ostia.32 At Sardis, numerous menorah depictions, in engravings, reliefs and sculpture, were found throughout the synagogue and in proximity to it.33 Similarly, at Dura Europos, Andriake and Priene—synagogues that lack mosaic carpets—menorahs appear in frescoes, reliefs and engravings. Seemingly, not one community refrained from depicting the menorah—usually with accompanying religious symbols—in the space of the synagogue.

Two phenomena thus characterize the iconography of mosaic carpets (and largely, all the visual art) of Diaspora synagogues: limited portrayal of figural images and the presence of religious symbols. In order to assess the significance of these phenomena, I will seek to discern the relationship between this group of mosaics and two additional groups: the local Late Roman and Byzantine mosaic carpets, in religious and civic buildings, adjacent in time and place to the synagogues, and the contemporary mosaic carpets in Palestinian synagogues.

According to a widespread opinion, the mosaic carpets of Diaspora synagogues share, above all, an artistic language with local mosaic art.34 Indeed, this affinity between the Jewish and local mosaic carpets, expressed as stylistic resemblances and identical geometric patterns is clearly discernible at several sites. Thus, for example, at Apamea, geometric designs in the late 4th century synagogue mosaic also decorate mosaic carpets at a spacious villa dated to the second half of the 4th century.35 At the villa, the geometric patterns frame large panels that display sophisticated figural depictions; the synagogue artist, however, omitted the figural panels and filled the entire area with geometric designs. Furthermore, the geometric pattern in the synagogue’s southern mosaic carpet (Figure 1) appears in several contemporary Antiochian mosaics—attesting the mobility of decorative patterns, transcending religious boundaries in Byzantine Syria.36 At Stobi, the excavators pointed to a clear resemblance between the 4th and 5th century synagogue mosaics and local mosaics: one in a private home named ‘the casino’, and the other in the second phase of the old Episcopal Basilica, dated to the early 5th century. They suggest that the Jewish and Christian communities engaged the same workshops to install the mosaic carpets.37 In Sardis, civic structures of the Bath-Gymnasium complex (which included the synagogue) were paved during the 4th and 5th centuries with geometric mosaic carpets, similar in style and design to those that were installed in the synagogue during the same period.38

The affinity of the synagogue mosaics to local mosaic art is not at all surprising: it is only natural that the Jewish community designed its house of prayer in conformance to aesthetic conventions that were current in the near environment and engaged local workshops to this end. Joint Jewish, Christian and pagan patronage of the same workshops, with customization of the works, such as sarcophagi decorations, gold glasses, chancel screens and mosaic carpets, to each group’s specific requirements, is a well known phenomenon in late antique art.39 Nevertheless, the absence, in a religious structure, of identity markers of the religious group that functioned within the building runs counter to expectation. As such, the two phenomena discussed above—the restriction of figural images and the presence of religious symbols—indeed articulate the worldview of the Jewish communities and are in dissonance with local mosaic art. Regarding religious symbols—these were generally harmonized within the existing geometric patterns, with no need for customization. Thus, for example, in the synagogue at Kelibia: the rectangular mosaic in the prayer hall is divided vertically and horizontally into 11 square, identically sized units (one of the corner units is missing). Various elements: amphorae, flowers, Solomon knots and a square decorate the corners of the units. Three of the 11 units contain depictions of menorahs, one in each corner.40

The attitude towards figural art is a different matter: in this case, the Jewish mosaic carpets represent a position that diverged from that of their non-Jewish environment. Late Roman and Early Byzantine mosaics, from east to west, abounded in figural images including zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures as well as representations of deities and Christian saints. This distinction manifests clearly at those sites where figural mosaic carpets are close in time and location to synagogue mosaics. Thus, for example, a villa in Apamea, located near the synagogue, houses a 4th century mosaic carpet depicting the Greek philosopher Socrates and six of his disciples seated in a semi-circle.41 Thus also at Ostia, where figural mosaics dated to the 4th century adorned the caldarium and the frigidarium in the Baths of Musiciolus, built very close to the synagogue, on the northern side of the Severiana road. The mosaic carpet in the caldarium features a decorative border that creates square and rectangular panels. Five of the panels are occupied by male busts: four are athletes while the fifth—Pascentius—is depicted as a cloaked and bearded older man.42

This example, among others,43 demonstrates that the cautious approach towards figural images manifested in Jewish mosaics did not harmonize with the local mosaic art and, in this context, might have expressed a tendency to differentiation. While, for the most part, Jewish symbols integrated smoothly into the common geometric patterns, the tendency to minimize and avoid figural images differentiated between synagogue mosaics and local mosaic art. Thus, synagogue artists conceived elaborate geometric-decorative schemes to fill entire carpets, and these became a hallmark of Jewish diasporic mosaic art.44

The second reference group is contemporary mosaic carpets from Palestinian synagogues. Nearly 25 mosaic carpets have hitherto been revealed in the Land of Israel and only a handful are designed as geometric-decorative carpets devoid of zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures, resembling those found in Diasporan synagogues. These carpets are dated mostly to the early Muslim period, and therefore, evince the stylistic influence of Muslim anti-figural conceptions.45 Conversely, most of the mosaic carpets installed in Palestinian synagogues (including Gerasa in Jordan) combine a variety of figural images in their decorative scheme.46 These include animals that inhabit rows of medallions, such as in the nave at the Ma’on Nirim synagogue (Figure 8) and in the southern aisle at Gaza,47 and others that appear alongside dedicatory inscriptions and religious symbols at Hammat Tiberias, Sepphoris and Beit Alpha.48

Figure 8.

Rows of medallions inhabited by animal figures and a menorah in the mosaic floor of the prayer hall, the synagogue at Ma’on Nirim, 6th century. Courtesy of the Israel Exploration Society.

Additionally, anthropomorphic and even pagan figures appear, especially in the depictions of the zodiac that adorned seven Palestinian synagogues, including the recently excavated synagogue at Huqoq. Female figures generally represent the seasons of the year that adorn the four corners of the depiction; at Huqoq and Susiya the figures (not necessarily female) are winged.49 The zodiac signs of Libra, Sagittarius, Aquarius, Gemini and Virgo are portrayed anthropomorphically. The artists at Sepphoris and at Huqoq even went so far as to pair each zodiacal image with a youth.50 Adorning the inner circle of the zodiac is the figure of Sol Invictus, the Roman sun god, driving a quadriga—a chariot drawn by four horses. Additional pagan images occur in the zodiac sign of Sagittarius, depicted as a centaur in Sepphoris,51 and in the sign of Capricorn at Hammath Tiberias and at Huqoq where the goat is portrayed as Capricorn—the mythological sea goat (Figure 9).52

Figure 9.

The sign of Capricorn in the zodiac panel, the mosaic carpet of the prayer hall, the synagogue at Hammath Tiberias, 4th century. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Similarly, figural images are integrated in depictions of biblical scenes, such as the Binding of Isaac (Sepphoris and Beit Alpha), Daniel in the Lion’s Den (Susiya and Na’aran), and the Tower of Babel (Wadi Hammam and Huqoq), that are sometimes intertwined with midrashic interpretations. It is true that the synagogue most replete with depictions of biblical scenes was actually discovered in the Diaspora, in Dura Europos. However, the elaborate iconographic program at this synagogue is unknown in any other ancient synagogue—in the Diaspora or in the Land of Israel—and therefore Dura Europos should be viewed in this context as a unique and singular case amongst all ancient synagogues.53

Visual depictions of biblical scenes incorporated into the synagogue décor convey a double message: the first, directed inwards, at the Jewish community that interpreted these stories as ancient models of faith and deliverance from oppressors. The second is directed outward, at non-Jewish groups that also draw on biblical traditions as a cornerstone of their faith, i.e., the Christian community. It is generally argued that these works of art were intended not only to bolster the faith of synagogue worshippers but also to sustain a dialogue with and polemic against Christian biblical exegesis54—a shared and polemical aspect that is absent from the mosaic carpets of the Diasporan synagogues. Apparently, the predominant trend that informed the design of these mosaic carpets avoided conversation with the non-Jewish environment, both pagan—by refraining from motifs associated with paganism, and Christian—by refraining from depicting biblical themes, whose exegesis was a source of polemic between the two religions.

The mosaic carpets that adorned Late Roman and Byzantine diasporic synagogues therefore constitute a cohesive group defined by distinct and autonomous characteristics. The main iconographic characteristic distinguishing them from their non-Jewish environment on the one hand, and from Palestinian synagogal art on the other hand, is the strict attitude towards figural art. This attitude manifests in the absence of human and pagan figures, as well as biblical themes at all the sites, and in the avoidance of any figural images at many sites. When zoomorphic images do appear in the mosaics, they generally serve to enrich the carpet’s decorative effect and possess no symbolic or religious significance. These unique characteristics paint a portrait of an independent group with a distinctive identity that resonates in its visual art.

What is the significance of these aesthetic preferences? The synagogue was the Jewish community’s principal and most essential public building. Its art was not merely decorative: it expressed the community’s beliefs, identity, and at times, its contention with opposing religous ideologies. Mosaic carpets embellished with sophisticated symbolic and narrative schemes such as those at Beit Alpha, Sepphoris and Na’aran, surely reflect the community’s spiritual world even if modern scholars’ understanding of them is often disputed and uncertain. However, what can we deduce from geometric patterns, botanical motifs and a handful of religious symbols? In what way are they informative of the community’s world and life experience?

The religious symbols are certainly a key to this interpretation. Their presence in most of the mosaic carpets and in the entire artistic complex of the synagogues bespeaks their central role in establishing the buildings’ religious identity.55 The standing of these symbols within the synagogue’s decorative scheme varies from site to site: however, one must bear in mind that the structures and their décor have been discrepantly preserved. Moreover, we may assume that the manner in which Jewish identity was defined in the space of the synagogue was influenced by the specific sitz im leben of each community and by the relationship that it maintained with its non-Jewish neighbors. Apparently then, the religious symbols, and the menorah in particular, functioned foremostly to define and shape the differential identity of the minority group operating in the space, vis-à-vis its surroundings. This does not negate their religious or liturgical functions, although these were of secondary importance.56

Seemingly, with regard to this matter, it is worth reconsidering the artistic findings from Palestinian synagogues that abounded in religious symbols, in various compositions. The most intricate composition appears in a panel with a central Torah shrine flanked by two menorahs, each in turn flanked by the four species, a shofar and an incense shovel (Figure 10).57

Figure 10.

Panel with ritual motifs in the mosaic carpet of the prayer hall, the synagogue at Beit Alpha, 6th century. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

This panel, replete with Temple motifs encircling the Torah shrine (or perhaps the Holy Ark58) is often interpreted as a visual expression of the rabbinic conception that regards the synagogue as a ‘lesser sanctuary’ (miqdash me’at).59 Although this composition has never been discovered in Diasporan synagogues, its occurrence in tombstone ornamentations, frescoes and gold-glass remains at the Roman catacombs casts doubt on the randomness of this absence.60

That said, visual expressions of the view of the synagogue as a ‘lesser sanctuary’ are also discernible at Diasporan synagogues. This is particularly conspicuous in the architectural emphasis on the storage space of the Torah scrolls within the prayer hall: the apse, the bima or the aedicule.61 Nevertheless, the menorah and its attendant ritual symbols portrayed in the mosaic carpets should not be viewed as appertaining to this concept. More plausibly, they function primarily as a marker of the structures’ Jewish identity—an identity in crucial need of amplification, faced with the overall rise and solidification of Christianity and, specifically, with the increasing harassment of the synagogues by Christian elements from the late 4th century onwards.62

Presumably, the prominence of geometric and decorative patterns in the mosaic carpets of the Diasporan synagogues articulates a trend of integration within the local and regional decorative language and is antithetical to the trend articulated by the religious symbols. The use of these patterns yields a neutral work of art that could complement any religious or civic building. This trend can be interpreted as the communities’ basic desire to live in peace and harmony with their non-Jewish neighbors as well as their willingness to absorb those norms and values that do not contradict their Jewish faith.63 Moreover, various evidence from this period depict a group called ‘God-fearers’, namely, non-Jews approaching Judaism who were involved as such in the synagogue and its activities. Possibly, this attachment, which resulted at times in conversion, influenced the desire to create a space of neutral character that would put all types of visitors at ease.64

Hitherto, I have attempted to discern the significance of the decorative elements occurring in the mosaic carpets. A comprehensive analysis, however, must consider not only what the mosaic carpets contain but also what is missing. The lack of anthropomorphic images and the dearth of zoomorphic images distinguish these works from the local Roman-Byzantine mosaics on the one hand, and from Jewish mosaics from the Land of Israel on the other. This iconographic phenomenon expresses a separatist mentality and estrangement from influences viewed as foreign to the Jewish world. These influences might appear in pagan form, like several images in Palestinian synagogues’ zodiac depictions, but they might also manifest in a biblical form, that—while seemingly loyal to Jewish tradition, also embraces an anti-Christian polemic. As opposed to their Palestinian counterparts, Diasporan communities were seemingly less interested in intensifying the anti-pagan and anti-Christian polemical dimension in their synagogues. This reflects two different and even contradictory factors: first, the interest in Judaism on the part of local pagans and Christians that was expressed, inter alia, through visits to the synagogue—a prevailing phenomenon until the late 4th century. Second and conversely, the mounting hostility towards Jewish communities among Christian authorities and worshippers, from the second half of the 4th century. This hostility gave rise to the sporadic destruction and abandonment of synagogues, their renovation as churches and—in extreme cases—forced conversions of Jews.65 Archaeological evidence of these events is discernable at the sites of four synagogues—Apamea, Stobi, Alece and Saranda—that were abandoned by the Jewish community and converted into churches. Literary sources, however, significantly expand this picture.66 Clearly, visual hints of polemic were inopportune in this harsh environment, for which neutral decorative schemes represented a suitably discreet choice.

Thus, the neutral design of mosaic carpets in Byzantine diasporic synagogues might correlate directly with heightened tensions and hostility between Jews and Christians and the resultant harassment of Jewish communities in some areas; this is in contradiction to the Land of Israel where such abovementioned acts of violence were unknown.67 Furthermore, it bears noting that at least half of the communities overwhelmingly chose to avoid figural images, including animal figures. Some scholars attribute this to a strict implementation of the second commandment68 or to an expression of conservatism;69 however, in our view, it appertains to the social-cultural context outlined above. Figural representations were a characteristic of the Roman-Byzantine visual art and therefore their eschewal created an element of differentiation and emphasized the unique religious-cultural framework of the Jewish community.

To sum up, the mosaic carpets in late antique Diaspora synagogues embrace two cultural trends which seem to contradict each other: a trend of integration within the visual language of the local mosaic art, and on the other hand, a trend that emphasizes a distinct Jewish identity within the surrounding culture. The first trend manifests in the extensive use of decorative geometric carpets, and the second, in the incorporation of religious symbols within the decorative schemes and in the avoidance of figural images. This ambivalent attitude is at once the seeming result and the reflection of the complexity of Jewish communal life in the Diaspora, one that manifests in other areas of life as well. Rutgers discerned a similar phenomenon concerning the epigraphic evidence from Jewish tombstones in Rome: on the one hand, he observed the use of Koine Greek and vulgar Latin that characterize non-Jewish inscriptions from the same period. Furthermore, most of the names in these inscriptions are Greek or Latin names that were prevalent among the surrounding society. On the other hand, Jews were buried separately from gentiles, Jewish symbols marked their burial sites and the inscriptions utilized terminology that was unique to the Jewish community, including, inter alia, references to the deceased’s official function within the community. Trends of integration and differentiation thus intertwined.

The mosaic carpets of the Diasporan synagogues—although vague and uninspired at first glance, in comparison to their counterparts in Palestinian synagogues—demonstrate, through their simplicity, complexity and thoughtful deliberation as to how the Jewish community should meet the challenges of Diasporan reality during a period of political and religious instability that demanded extra caution. Although unalike by many parameters, the Jewish communities faced similar challenges during the early Byzantine period onwards, which led them to implement comparable decisions regarding synagogue décor in general and mosaic carpets in particular.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

| BASOR | The Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research |

References

- Ameling, Walter. 2004. Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis, II: Kleinasien. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Avi-Yonah, Michael. 1960. The Mosaic Pavement of Ma’on (Nirim). Louis M. Rabinowitz Fund Bulletin 3: 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Balty, Janine. 1995. Une nouvelle mosaïque du IVe siècle dans l’édifice dit “au triclinos” à Apamée. In Mosaïques Antiques du Proche-Orient: Chronologie, Iconographie, Interpretation. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, pp. 177–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barag, Dan, Yosef Porat, and Ehud Netzer. 1981. The Synagogue at En-Gedi. In Ancient Synagogues Revealed. Edited by Lee Israel Levine. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society, pp. 116–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baramki, Dimitri. 1938. An Early Byzantine Synagogue near Tell Es-Sultan. Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine 6: 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, Douglas. 2013. Ostia in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balty, Janine. 1991. La mosaïque romaine et byzantine en Syrie du Nord. Revue du Monde Musulman et de la Méditerranée 62: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, Nadin. 2014. Uncomparable Buildings? The Synagogues in Priene and Sardis. Journal of Ancient Judaism 5: 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonz, Marianne Palmer. 1993. Differing Approaches to Religious Benefaction: The Late Third-Century Acquisition of the Sardis Synagogue. Harvard Theological Review 86: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botermann, Helga. 1990. Die Synagoge von Sardes: Eine Synagoge aus dem 4. Jahrhundert? Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 81: 103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Scott, ed. 1996. Severus of Minorca: Letter on the Conversion of the Jews. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Brenk, Beat. 1991. Die Umwandlung der Synagoge von Apamea in eine Kirche. TESSERAE.Festschrift für Joseph Engemann. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum. Ergänzungsband 18: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brooten, Bernadette. 1982. Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue: Inscriptional Evidence and Background Issues. Chico: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buckler, William Hepburn, and David Moore Robinson. 1932. Sardis VII: I, Greek and Latin Inscriptions. Leyden: American Society for the Excavation of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, Nadin, and Mark Wilson. 2013. The late antique Synagogue in Priene: Its History, Architecture, and Context. Gephyra 10: 166–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cevik, Nevzat, Ozgu Comezoglu, Hüseyin Sami Öztürk, and Inci Turkoglu. 2010. Unique Discovery in Lycia: The Ancient Synagogue at Andriake, Port of Myra. Adalya 13: 335–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chaniotis, Angelos. 2002. The Jews of Aphrodisias: New Evidence and Old Problems. Scripta Classica Israelica 21: 209–42. [Google Scholar]

- Colafemmina, Cesare. 2012. The Jews in Calabria, a Documentary History of the Jews in Italy 33. Brill: The Goren-Goldstein Diaspora Research Centre, Tel Aviv University, Leiden. [Google Scholar]

- Costamagna, Liliana. 1991. La sinagoga di Bova Marina nel quadro degli insediamenti tardoantichi della costa Ionica meridionale della Calabria. Mélanges de l’école française de Rome 103: 611–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costamagna, Liliana. 1994. La sinagoga di Bova Marina. In Architettura Judaica in Italia: Ebraisimo, sito, Memoriadei Loughi. Edited by R. La Franca. Palermo: Flaccovio Editore, pp. 239–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, Elizabeta, Silvana Blaževska, and Miško Tutkovski. 2012. Early Christian Wall Paintings from the Episcopal Basilica in Stobi. Stobi: National Institution Stobi. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Moshe. 1983. Hammath Tiberias—Early Synagogues and the Hellenistic and Roman Remains (Final Excavation Report: I). Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Drbal, Vlastimil. 2009. Socrates in late antique Art and Philosophy: The Mosaic of Apamea. Series Byzantina 7: 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbabin, Katherine M. D. 1999. Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorjetski, Estēe. 2005. The Synagogue-Church at Gerasa in Jordan. A Contribution to the Study of Ancient Synagogues. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 121: 140–67. [Google Scholar]

- Engemann, Josef. 1968–1969. Bemerkungen zu römischen Gläsern mit Goldfoliendekor. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 11/12: 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fantar, Mounir. 2009. Sur la découverte d’un espace cultuel juif à Clipea (Tunisie). Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 153: 1083–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Louis Harry. 1993. Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World: Attitudes and Interactions from Alexander to Justinian. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 1997. This Holy Place: On the Sanctity of the Synagogue during the Greco-Roman Period. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 2005. Liturgy and the Art of the Dura Europos Synagogue. In Liturgy in the Life of the Synagogue: Studies in the History of Jewish Prayer. Edited by R. Langer and S. Fine. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven, and Leonard Rutgers. 1996. New Light on Judaism in Asia Minor during late antiquity: Two Recently Identified Inscribed Menorahs. Jewish Studies Quarterly 3: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fraade, Steven, D. 2019. Facing the Holy Ark: In Words and in Images. Near Eastern Archaeology 82: 156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen, Paula. 2016. ‘If It Looks like a Duck, and It Quacks like a Duck …’ On Not Giving up the Godfearers. In A Most Reliable Witness: Essays in Honor of Ross Shepard Kraemer. Edited by Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Nathaniel DesRosiers, Shira L. Lander, Jacqueline Pastis and Daniel Ullucci. Providence: Brown Judaic Series, pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 1998. Ancient Jewish Art and Archeology in the Diaspora. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2010. The Dura-Europos Synagogue Wall Paintings: A Question of Origin and Interpretation. In Follow the Wise: Studies in Jewish History and Culture in Honor of Lee I. Levine. Edited by Zeev Weiss, Oded Irshai, Jodi Magness and Seth Schwartz. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 403–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2018. The Menorah: Evolving into the Most Important Jewish Symbol. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1967. The Ninth Campaign at Sardis. BASOR 187: 9–32, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George Maxim Anossov, and Nancy Hirschland Ramage. 1978. Sculpture from Sardis: The Finds through 1975. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Edward D. 1982. St. Stephen in Minorca: An Episode in Jewish—Christian Relations in the Early 5th Century A.D. The Journal of Theological Studies 33: 106–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilan, Zvi. 1991. Ancient Synagogues in Israel. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Herbert Leon. 2000. The Sepphoris Mosaic and Christian art. In From Dura to Sepphoris: Studies in Jewish Art and Society in late Antiquity. Edited by Lee Israel Levine and Zeev Weiss. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kiperwasser, Reuven, and Serge Ruzer. 2013. The Holy Land and Its Inhabitors in Travel Stories of Bar-Sauma. Cathedra 148: 41–70. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Kolarik, Ruth. 2014. Synagogue Floors from the Balkans Religious and Historical Implications. Niš and Byzantium 12: 115–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kraabel, Alf Thomas. 1979. The Diaspora Synagogue: Archeological and Epigraphic Evidence since Sukenik. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Romischen Welt, II, 19.1. Edited by Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 477–510. [Google Scholar]

- Kraeling, Carl Hermann. 1979. The Synagogue: The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Final Report VIII/I. New Haven: Yale University Press, New York: Ktav Pub. House. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, John H. 2001. The Greek Inscriptions of the Sardis Synagogue. Harvard Theological Review 94: 5–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Doro. 1947. Antioch Mosaic Pavements. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lee Israel. 2005. The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lee Israel. 2012. Visual Judaism in late Antiquity. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, Amnon. 1987. The Jews in Roman Imperial Legislation. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Magness, Jodi. 2005. The Date of the Sardis Synagogue in Light of the Numismatic Evidence. American Journal of Archaeology 109: 443–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magness, Jodi, Shua Kisilevitz, Matthew Grey, Dennis Mizzi, Daniel Schindler, Martin Wells, Karen Britt, Ra’anan Boustan, Shana O’Connell, Emily Hubbard, and et al. 2018. The Huqoq Excavation Project: 2014–17 Interim Report. BASOR 380: 61–131. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, Lawrence J. 1967. Evidence for the Interior Decoration of the Synagogue. BASOR 187: 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Matassa, Lidia D. 2018. Invention of the First-Century Synagogue. Edited by Jason M Silverman and Murray Watson. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayence, Fernand. 1935. La quatrième campagne de fouilles à Apamée. l’Antiquité Classique 4: 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayence, Fernand. 1939. La VIe campagne de fouilles à Apamée. l’Antiquité Classique 8: 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoleone-Lemaire, Jacqueline, and Jean Charles Balty. 1969. L’église à Atrium de la Grande Colonnade. Bruxelles: Centre Belge de recherches archéologiques à Apamée de Syrie. [Google Scholar]

- Nau, François. 1927. Deux épisodes de l‘histoire juive sous Theodose II (423–438) d’après la vie de Barsauma le Syrien. Revue des Études Juives 83: 184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Netzer, Ehud, and Gideon Foerster. 2005. The Synagogue at Saranda, Albania. Qadmoniot 129: 45–53. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Noga-Banai, Galit. 2008. Between the Menorot: New Light on a Fourth Century Jewish Representative Composition. Viator 39: 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, David. 1993. Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, I: Italy, Spain and Gaul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, David. 1995. Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, II: The City of Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, David, and Susan Sorek. 2003. ‘Peace and Mercy upon all your Blessed People’: Jews and Christians at Apamea in late antiquity. Jewish Culture and History 6: 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, David, Alexander Panayotov, and Hanswulf Bloedhorn. 2004. Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis, I: Eastern Europe. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Ovadia, Asher. 1981. The Synagogue at Gaza. In Ancient Synagogues Revealed. Edited by Lee I. Levine. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society, pp. 129–31. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotov, Alexander. 2004. The Jews in the Balkan Provinces of the Roman Empire: The Evidence from the Territory of Bulgaria. In Negotiating Diaspora: Jewish Strategies in the Roman Empire. Edited by John Martyn Gurney Barclay. London: T & T Clark International, pp. 38–65. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, James. 1961. Conflict of the Church and the Synagogue: A Study in the Origins of Antisemitism. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Rajak, Tessa. 2006. The Jewish Diaspora. In Cambridge History of Christianity, I. Edited by Margaret M. Mitchell and Frances M. Young. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rautman, Marcus. 2010. Daniel at Sardis. BASOR 358: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautman, Marcus. 2015. A menorah Plaque from the Center of Sardis. Journal of Roman Archaeology 28: 431–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Gerson, Leah. 2001. The Jews of Syria as Reflected in the Greek Inscriptions. Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers, Leonard Victor. 1995. The Jews in Late Ancient Rome: Evidence of Cultural Interaction in the Roman Diaspora. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers, Leonard Victor. 1996. Diaspora Synagogues: Synagogue Archeology. In Sacred Realm: The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World. Edited by Steven Fine. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 67–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers, Leonard Victor. 1998. The Hidden Heritage of Diaspora Judaism. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Seager, Andrew R. 1972. The Building History of the Sardis Synagogue. American Journal of Archeology 76: 425–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, Andrew R., and Alf Thomas Kraabel. 1983. The Synagogue and the Jewish Community. In Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis 1958–75. Edited by George Maxim Anossov Hanfmann. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 169–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, A. R. R. 1979. Jews, Christians and Heretics in Acmonia and Eumenia. Anatolian Studies 29: 169–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1932. The Ancient Synagogue of Beth Alpha. Jerusalem: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1935. The Ancient Synagogue of El-Hammeh. Jerusalem: R. Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1950–1951. The Mosaic Inscriptions in the Synagogue at Apamea on the Orontes. The Hebrew Union College Annual 23: 541–51. [Google Scholar]

- Talgam, Rina. 2014. Mosaics of Faith: Floors of Pagans, Jews, Samaritans, Christians, and Muslims in the Holy Land. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi Press, University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tzaferis, Vassilios. 1982. The Ancient Synagogue at Ma’oz Hayyim. Israel Exploration Journal 32: 215–44. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoogen, Violette. 1964. Apamée de Syrie aux Musées Royaux d’art et D’histoire. Bruxelles: M. Weissenbruch. [Google Scholar]

- Villey, Thomas. Forthcoming. La question de la licéité des images dans le judaïsme ancien à travers l’exemple des pavements en mosaïque de deux synagogues africaines. In Actes de la Table Ronde Image et Droit: Le Droit aux Images, Rome, 2–3 Décembre 2013. forthcoming.

- Walsh, Robyn Faith. 2016. Reconsidering the Synagogue/Basilica of Elche, Spain. Jewish Studies Quarterly 23: 91–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Zeev. 2005. The Sepphoris Synagogue. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Ze’ev. 2016. Decorating the Sacred Realm: Biblical Depictions in Synagogues and Churches of Ancient Palestine. In Jewish Art in Its Late Antique Context. Edited by U. Leibner and C. Hezser. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 121–68. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt, and Herbert Kessler. 1990. The Frescoes of the Dura Synagogue and Christian Art. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Werlin, Steven. 2015. Southern Palestine, 300–800 C.E.: Living on the Edge. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- White, L. Michael. 1990. Building God’s House in the Roman World: Architectural Adaptation among Pagans, Jews, and Christians. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, L. Michael. 1997. Synagogue and Society in Imperial Ostia: Archaeological and Epigraphic Evidence. Harvard Theological Review 90: 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, Robert Louis. 1983. John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late 4th Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yegül, Fikret K. 1986. The Bath-Gymnasium Complex at Sardis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Some scholars classify Gerasa as a Diasporan synagogue; however, I believe there is a clear affinity between the synagogues in the provinces of Palestine and Arabia, including Gerasa and the synagogue at Naveh in the Hauran, Moreover, the mosaic floor at the synagogue of Gerasa (and the church above it) appertains to a regional artistic tradition of mosaic floors in synagogues and churches in the provinces of Palestine and Arabia. See (Talgam 2014, pp. 319–22). Therefore, I have defined ‘Diaspora’ as the area outside of these provinces. Unfortunately, I do not address the Babylonian diaspora in this article as hitherto not a single synagogue has been uncovered in this region. See (Levine 2005, pp. 286–91). |

| 2 | For several key studies that include additional references, see (Kraeling 1979; Weitzmann and Kessler 1990; Fine 2005; Hachlili 2010; Levine 2012, pp. 97–118). |

| 3 | For collections of Jewish inscriptions from the various regions, see (Noy 1993, 1995; Noy et al. 2004; Ameling 2004). See also (Rutgers 1995; Panayotov 2004). For the map of the Jewish diaspora based on archeological finds and literary evidence, published by Haifa University’s Jewish Diaspora mapping project, see: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1fiMBoXPJrqzEV-5PU0dKMVMbQbk&ll=32.46113771566362%2C27.950343482299445&z=4. |

| 4 | The Jewish identity of the building is still disputed, see (Matassa 2018, pp. 37–77). |

| 5 | However, it seems that at the time of the Ostia synagogue’s construction the area along the seashore was settled and active. See (White 1997, pp. 27–28; Boin 2013, pp. 119–20). |

| 6 | See (Kraabel 1979; White 1990, pp. 60–77; Rutgers 1996; Hachlili 1998, pp. 25–76; Levine 2005, pp. 252–83). |

| 7 | Mosaic carpets did not adorn the synagogues at Delos, Dura Europos, Priene and Andriake, though only the last two were operational in the Byzantine period, when, under Christian influence, mosaic carpets became a prominent decorative medium in synagogues. The main decorative medium in the synagogues of Priene and Andriake is the sculptural medium, mainly carved marble slabs. See (Burkhardt and Wilson 2013, pp. 177–78; Cevik et al. 2010, pp. 341–44). |

| 8 | See (Mayence 1935; 1939, p. 203; Brenk 1991; Hachlili 1998, pp. 32–34; Levine 2005, pp. 258–60). |

| 9 | This mosaic evokes women’s special status in the community: the inscriptions mention eight women as independent donors and mentions the others with their husbands. According to the inscriptions, they financed the installation of over half the carpet. On dedicatory inscriptions that reference female donors to antique synagogues, see (Brooten 1982, pp. 157–65). |

| 10 | See (Sukenik 1950–1951; Roth-Gerson 2001, pp. 54–83; Noy and Sorek 2003). |

| 11 | See (Balty 1991; Dunbabin 1999, pp. 176–86). |

| 12 | See (Verhoogen 1964, p. 16). |

| 13 | See (Mayence 1935, pp. 200–1; Napoleone-Lemaire and Balty 1969, pp. 13–22). |

| 14 | See (Costamagna 1991, pp. 623–25; 1994, pp. 239–41; Hachlili 1998, pl. VII: 2). |

| 15 | As such, the northwestern entrance was obviously the main entrance. Excavators found an intact amphora and fragments of other amphorae in a room adjoining the prayer hall, indicating its possible use as a storeroom for food. Two amphorae handles stamped with menorahs attest the amphorae’s use by community members. A pitcher containing over 3000 bronze coins, dated mostly to the 5th century, was found in another room. See (Colafemmina 2012, pp. 2–3). |

| 16 | See (Costamagna 1991, pp. 626–27; 1994, p. 242). |

| 17 | (See (Costamagna 1991, p. 628; 1994, p. 243). |

| 18 | The excavators identify four architectural phases of the building, the fourth an uncontrovertibly Jewish structure, and the third debatably so. Magness, by contrast, suggested that the synagogue was established as late as the mid-6th century. See (Seager 1972, pp. 433–35; Botermann 1990; Bonz 1993; Magness 2005). |

| 19 | An inscription that enumerates the city’s public fountains mentions ‘the synagogue’s fountain’: συναγωγῆ [ς κρήνη—]. If indeed this is the said fountain, it appears to have serviced not just the Jewish community but rather all the city’s inhabitants. See (Buckler and Robinson 1932, pp. 37–40). |

| 20 | See (Hanfmann 1967, pp. 10–32; Majewski 1967, pp. 32–46; Seager and Kraabel 1983, pp. 168–74; Hachlili 1998, pp. 218–31). |

| 21 | See (Majewski 1967, pp. 41–50, figs. 59–60, 71; Seager and Kraabel 1983, pp. 262–66). |

| 22 | See (Hanfmann and Ramage 1978, pp. 63–65, figs. 92–101 [lions], pp. 148–49, figs. 379–82 [table of eagles]). For a discussion regarding the significance of these spolia objects in the prayer hall, see (Levine 2012, pp. 304–6). |

| 23 | See (Hanfmann and Ramage 1978, pp. 151–52, figs. 391–93; Seager and Kraabel 1983, pp. 170–71). |

| 24 | See (Seager 1972, p. 435). |

| 25 | Additional mosaic fragments that are identified with this phase are mostly geometric and decorative. See (Netzer and Foerster 2005, pp. 47–49). |

| 26 | See (ibid., pp. 49–53). |

| 27 | Anthropomorphic images are completely absent from Diasporan Jewish art of the Byzantine period, yet manifest extensively in the frescoes at Dura Europos from the mid-3rd century. An exception is a small engraving depicting the biblical story of Daniel in the lion’s den discovered at the Sardis synagogue; see below, note 53. |

| 28 | Hachlili argues that the menorah appears frequently alongside the lulav and ethrog in Diasporan synagogues and much less often alongside the shofar. See (Hachlili 1998, p. 354; 2018, pp. 133–35). |

| 29 | See (Panayotov 2004, pp. 41–45). |

| 30 | See (Fantar 2009, p. 1085, fig. 2). |

| 31 | See (Walsh 2016, pp. 96–99). |

| 32 | See (Hachlili 1998, pl. II: 9–10). |

| 33 | Most of the artistic works were found in the prayer hall, and several in the forecourt and in the stores near the synagogue. Recently, Marcus Rautman published a marble slab engraved with a menorah flanked by a lulav and an ethrog that was uncovered at the city’s center (field 55). See (Burkhardt 2014, p. 198; Rautman 2015). |

| 34 | See (Hachlili 1998, p. 236). |

| 35 | See (Balty 1995, pp. 177–90, pl. XVIII: 1–2). This is the plate’s number. In Levi 1947 (below), vol I is text, and vol. II is plates. |

| 36 | See in the 4th century mosaic carpet from the Yakto Complex in Daphne, near Antioch (Levi 1947, vol. I, pp. 280–81; vol. II, pl. 111: a), as well as in the 5th century mosaic from the ‘House of Ge and Season’ in Daphne, where a protome of a female personification populates the central medallion (ibid., vol. I, pp. 346–47; vol. II, pl. 82: a). Of the ties between the Jewish communities of Antioch and Apamea we can learn from two dedicatory inscriptions from the synagogue that mention the donation of ‘Ilasios (son) of Isakios, archisynagogos of the Antiochians’. See: (Roth-Gerson 2001, pp. 54, 57). |

| 37 | See (Kolarik 2014, pp. 118–19). |

| 38 | See (Yegül 1986, pp. 53, 243, 268, 272, 281). |

| 39 | See (Engemann 1968–1969; Rutgers 1995, pp. 67–73; 1998, pp. 76–82; Hachlili 1998, pp. 445–49). |

| 40 | See (Fantar 2009, figs. 5–6, 9, 11). |

| 41 | See (Drbal 2009). |

| 42 | Boin suggests that he is an umpire or a trainer, see (Boin 2013, pp. 61–62). |

| 43 | The same phenomenon appears in frescoes in Stobi: geometric mosaic carpets decorated the Episcopal Basilica—built during the first half of the 4th century, and considered the earliest church in Macedonia, The remains of the fresco found in the Church and in the nearby baptistery reveal figural depictions that adorned the walls as early as the 4th century. By contrast, remains of the fresco and stucco from the walls of the city’s synagogue are devoid of figural motifs. See (Dimitrova et al. 2012). |

| 44 | It is noteworthy that geometric aniconic carpets also adorned Roman and Byzantine structures during the 4th and 5th centuries: in Jewish society, however, they became the default due to reservations concerning figural art. |

| 45 | This is the case with Hammath Tiberias stage Ia, see (Dothan 1983, pp. 37, 93; Talgam 2014, p. 406), Jericho, see (Baramki 1938; Werlin 2015, pp. 72–84), and the late mosaic carpet in the center of the prayer hall in Susiya, see (Werlin 2015, pp. 152–54). The third stage of the mosaic carpet in Ma’oz Hayyim is aniconic as well, although it is dated prior to the Moslem conquest, see (Tzaferis 1982, pp. 223–27). Limited use of animal figures is evident in two additional mosaic carpets, in the synagogues of Ein Gedi and Hammath Gader. See (Barag et al. 1981, p. 119; Sukenik 1935, pp. 35–38). |

| 46 | Out of 26 mosaic carpets, 16 include images, four are aniconic and two present very few images (Ein Gedi and Hammath Gader). Another four mosaics were uncovered in a partial state that precludes their evaluation. |

| 47 | See (Avi-Yonah 1960, pp. 25–35 [Maon Nirim]; Ovadia 1981, p. 131 [Gaza]). |

| 48 | See (Dothan 1983, pl. 34 [Hammath Tiberias]; Weiss 2005, p. 62, fig. 4 [Sepphoris]; Sukenik 1932, pls. viii, xxii, xxvii [Beit Alpha]). |

| 49 | In Huqoq only the season of Autumn has survived, and for the first time, the season is depicted as a male figure. See (Magness et al. 2018, p. 100, fig. 37 [Huqoq]; Ilan 1991, p. 315 [Susiya]). |

| 50 | See (Weiss 2005, p. 105, fig. 46). |

| 51 | See (ibid., p. 119, fig. 61). |

| 52 | See (Dothan 1983, pl. 33: 6 [Hammath Tiberias]; Magness et al. 2018, p. 107, fig. 41 [Huqoq]). |

| 53 | On Dura Europos see above, note 2. Several years ago, another depiction of a biblical scene from a Diasporan synagogue, that of Sardis, was published. On three fragments of a gray marble slab is an engraving of a figure confronting four lions. The depiction was identified as Daniel in the lions’ den—a familiar biblical motif in Palestinians’ synagogue décor. That said, it should be noted that the marble fragments were found in a corner of the peristyle forecourt, together with artifacts dating to the early 7th century, and their context in the space of the synagogue is not very clear. See (Rautman 2010). |

| 54 | See for example (Kessler 2000; Talgam 2014, pp. 257–332; Weiss 2016). |

| 55 | See (Hachlili 1998, pp. 316–29; Fantar 2009, pp. 1091–94; Panayotov 2004, pp. 42–45; Burkhardt 2014, pp. 197–99; Walsh 2016, pp. 113–20). |

| 56 | Several marble plaques from various sites in Asia Minor that portray two spirals under the branches of a menorah - on either side of the central branch allude to the liturgical context. Fine and Rutgers propose that these images represent the synagogue scrolls, while their incorporation in the depiction of the menorah creates a strong affinity between the menorah of the Temple and the Torah scrolls of the synagogue, and is a visual expression of the conception of the synagogue as a ‘lesser sanctuary’. See (Fine and Rutgers 1996, pp. 12–17; Cevik et al. 2010, pp. 341–43). |

| 57 | This panel appears in Hammath Tiberias, Sephorris, Beit Alpha, Na’aran, and the Samaritan synagogue at Beit She’an. In Susiya two gazelles flank the menorahs. |

| 58 | For the affinity between the Ark of the Covenant and the Torah Shrine in rabbinic literature and late antique Jewish art, see (Fraade 2019). |

| 59 | B. Megillah 29a. |

| 60 | Noga-Banai discerns the historical background of this composition’s simultaneous appearance in the synagogue of Hammath Tiberias and in the Jewish Roman catacombs, during the second half of the 4th century. See (Noga-Banai 2008). If Talgam is correct in her assumption that during the 5th–6th century this panel’s context related to a Jewish-Christian polemic, then its absence from the Diasporan synagogues is quite clear, similar to the argument above in relation to the biblical depictions. See (Talgam 2014, pp. 266–68, 303–14). |

| 61 | See (Kraabel 1979; pp. 502–3; Rutgers 1996, pp. 84–89; Fine 1997, pp. 137–57). |

| 62 | See below, note 66. |

| 63 | Various attestations indicate that members of the Jewish community held offices in the municipal administration. At Sardis, nine community members held the title βουλευτής, member of the city council, and three others held offices in the imperial provincial administration, see (Kroll 2001, p. 10). A funerary inscription from arcosolium D7 in Venosa mentions two people holding the office of Maiores civitatis that is generally understood as civic leaders, see (Noy 1993, p. 119). Severus of Minorca’s Letter on the Conversion of the Jews also elicits this conclusion. He depicts a reality whereby Jews held key political and social posts in the city of Magona, at the eastern end of the island of Minorca, at the beginning of the 5th century. See (Bradbury 1996, pp. 25–43). |

| 64 | Most famous of this evidence is the dedicatory inscription of Aphrodisias from Asia Minor, dated to the 4th or 5th century that includes the names of 54 God fearers (in addition to 68 Jews and three gentiles), some of whom members of the city council, who donated to the Jewish community. The sermons of John Chrystosom against members of his community whom he accused of Judaizing attest to the appeal of Judaism to Christians during the late 4th century in Antioch. Similar warnings appear in the writings of Origen, Ephrem the Syrian and others. The literature on this issue is very extensive; the following are some key studies that include additional bibliography. See (Sheppard 1979; Wilken 1983, pp. 66–94; Feldman 1993, pp. 383–415; Rutgers 1998, pp. 219–24; Chaniotis 2002, pp. 226–32; Levine 2005, pp. 292–99; Rajak 2006, pp. 63–65; Fredriksen 2016). |

| 65 | Rutgers proposes a cause and effect connection between the two phenomena: the stable and secure status of the Jewish communities throughout the Roman Empire during the first centuries CE, and the prominence of the synagogues in the municipal fabric, provoked hostility towards them. This hostility was explicit both in the legal realm – in the laws of Theodosius directed against the synagogues—and in the practical realm, in their physical destruction and their conversion into churches. See (Rutgers 1998, pp. 119–21; Linder 1987, pp. 73–74). |

| 66 | Literary sources shed light on synagogues that were destroyed by Christians, such as those at Rome, Edessa, Callinicum on the Euphrates, Rabat Moab (Areopolis) and Alexandria, as well as synagogues that were converted into churches at Magona (Minorca), Ravenna and Dertona (Italy), Tipasa (Algeria) and Antioch. See (Parkes 1961, pp. 166–68, 187, 204–7, 212–14, 236–38, 244, 263–64; Hunt 1982; Noy and Sorek 2003, pp. 20–22). At the same time, there were strong communities that managed to persist and even thrive, as therenovations conducted at the synagogues of Sardis and Ostia during the 5th and 6th centuries attest. |

| 67 | The closest sites that were damaged are in Transjordan: Gerasa, where in 530/1, a church was built atop the synagogue of the 4th and 5th centuries and the synagogue, and Rabat Moab that, according to historical sources, was destroyed by the monk Barsauma at the beginning of the 5th century. See (Dvorjetski 2005; pp. 158–60; Nau 1927, pp. 186–91; Kiperwasser and Ruzer 2013, p. 49). |

| 68 | As maintained by Noy and Sorek regarding the mosaic at Apamea, see (Noy and Sorek 2003, p. 13), as well as by Villey regarding the North African synagogues of Kelibia and Hammam Lif, and their avoidance of human images, in contrast with contemporary church mosaics. See (Fantar 2009; Villey forthcoming). |

| 69 | See (Levine 2005, pp. 307–8). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).