Mechanical Properties and Lattice Stabilization Mechanism of Phosphogypsum-Based Cementitious Materials for Solidifying Cr(VI)-Contaminated Soil in High Chloride Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

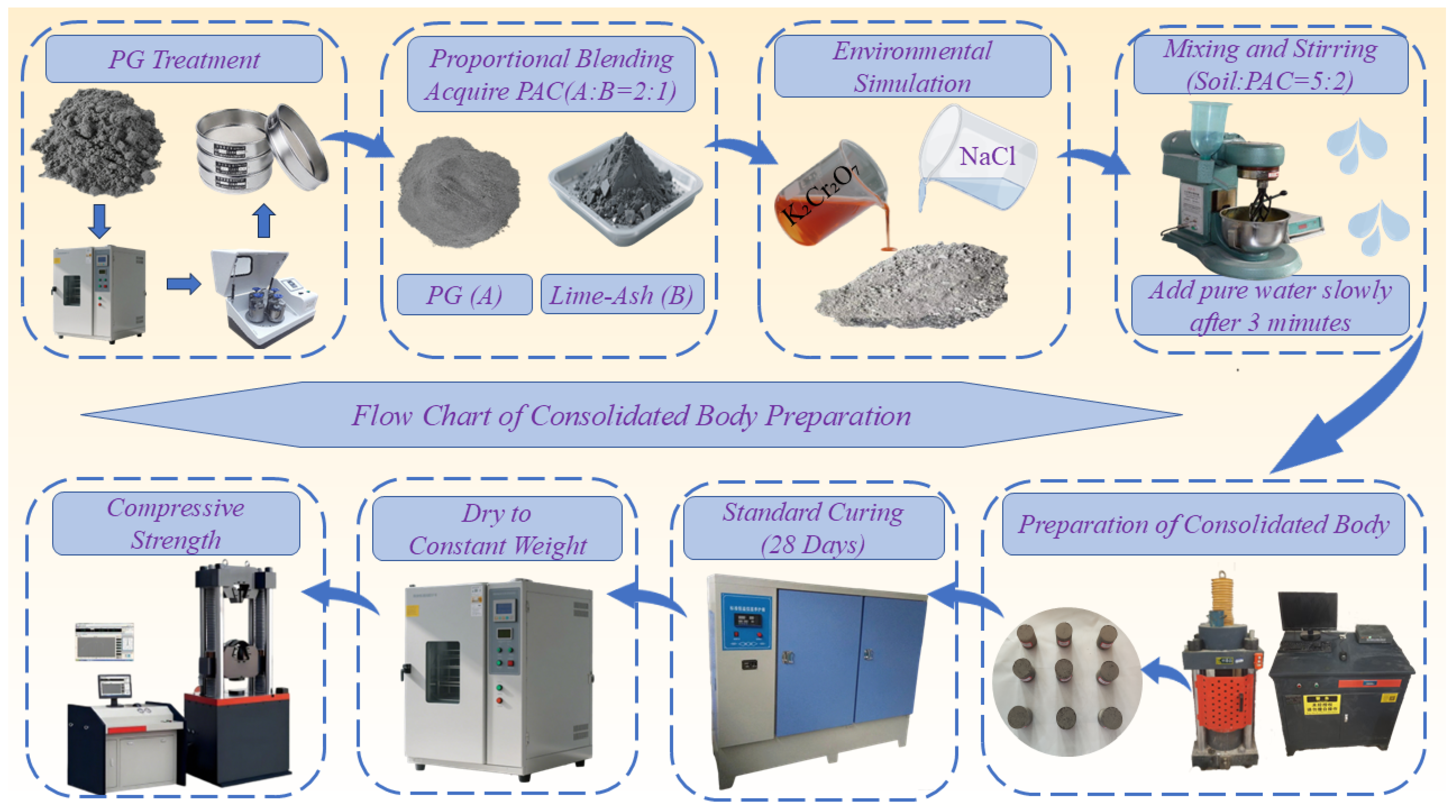

2. Test Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

2.2. Preparation of Cr(VI)-Contaminated Soil Under High-Salinity Conditions

2.3. PAC Preparation

2.4. Preparation of Solidified Body

2.5. Test Methods

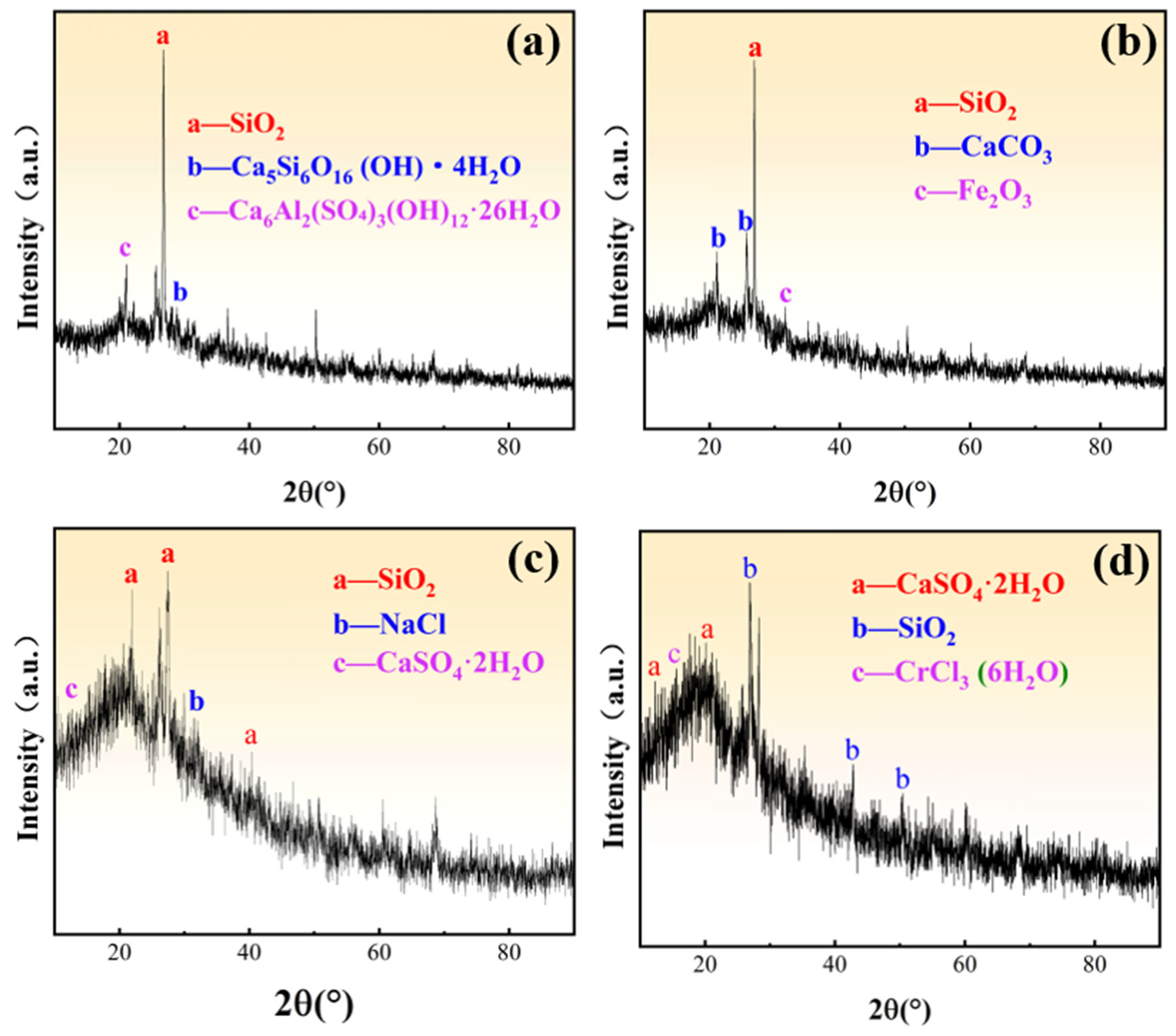

- (1)

- X-ray diffraction (XRD): To determine the crystalline structure and phase assemblage of each specimen, XRD was performed using a Rigaku SmartLab SE diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 40.0 kV and 40.0 mA. Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) was used, with a scanning rate of 5° min−1 in 2θ.

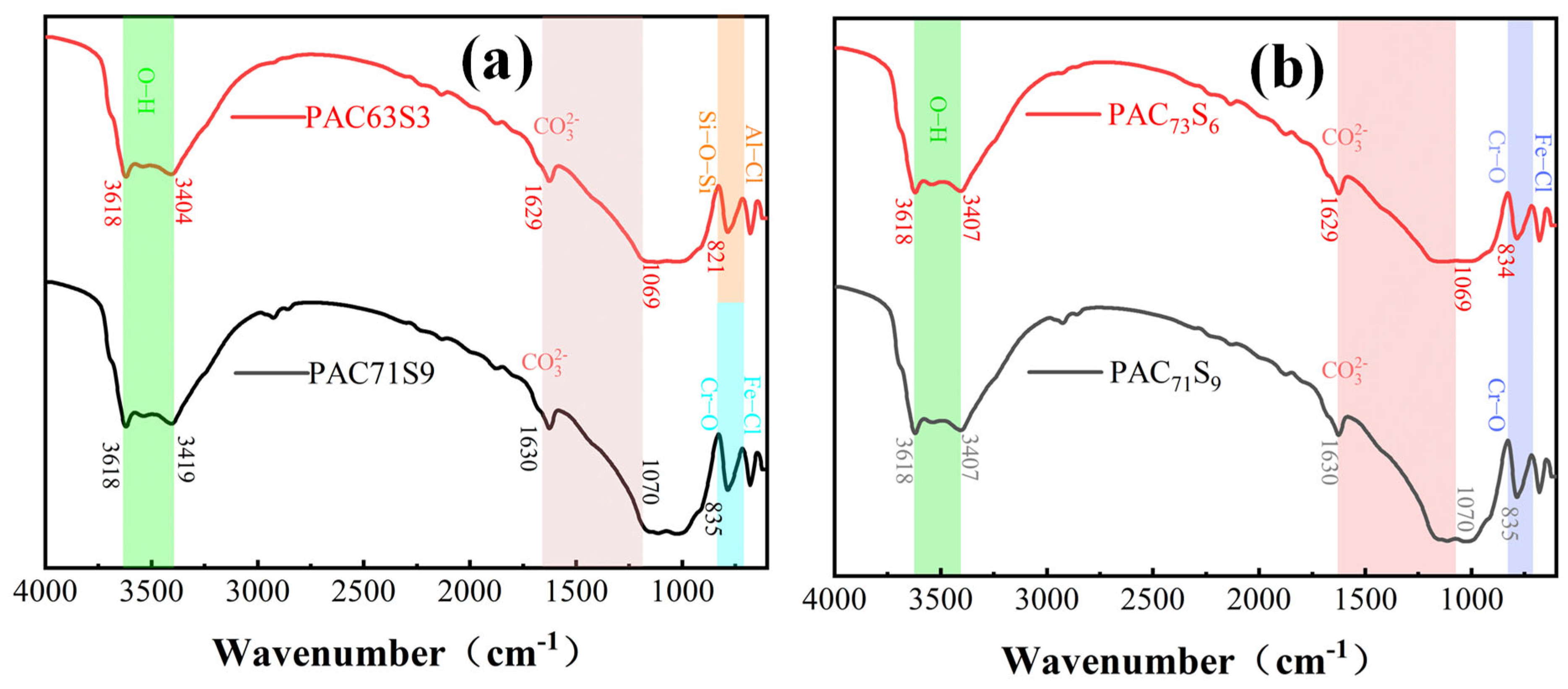

- (2)

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR): To probe molecular structure, chemical composition, and vibrational features, FTIR spectra were collected using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) over 4000–400 cm−1.

- (3)

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Surface morphology and microstructure were examined using a Gemini SEM 300 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and a Tescan SEM system (model 120-0283; Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic). Prior to imaging, all samples were oven-dried at 105 °C.

- (4)

- Specific surface area and pore structure: Specific surface area and pore characteristics were analyzed using an AUTOSORB-1-C analyzer (Quantachrome, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) with N2 as the adsorbate. Samples were degassed at 200 °C for 6 h before measurement.

3. Analysis of Test Results

3.1. Orthogonal Test Analysis

3.1.1. Mechanical Properties

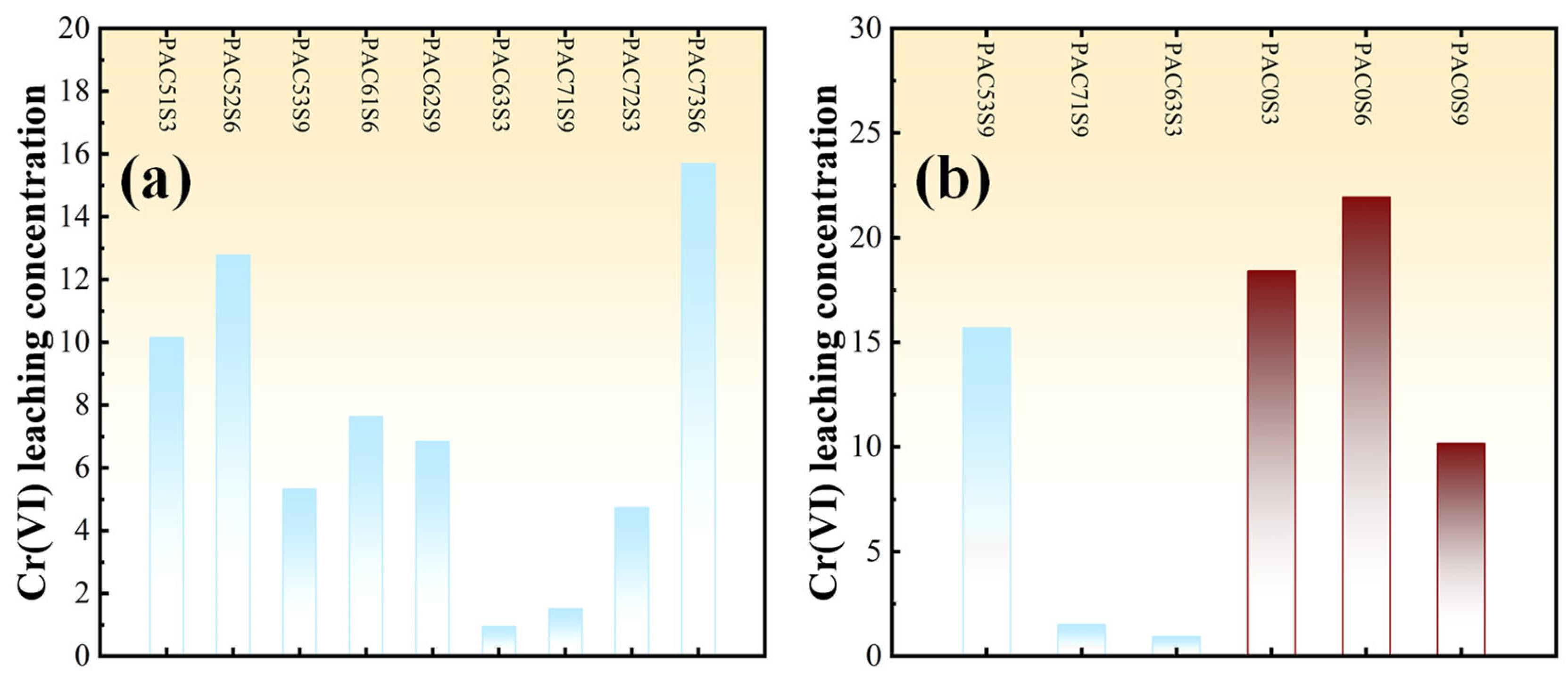

3.1.2. Toxic Leaching

3.2. Analysis of Microscopic Characteristics

3.2.1. Mineral Structure Composition

3.2.2. Functional Group Structure

3.2.3. Micromorphology

3.2.4. Electron Energy Spectrum Test

3.2.5. Specific Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution

3.2.6. Photoelectronic Energy Spectrum

3.3. Mechanistic Analysis and Discussion

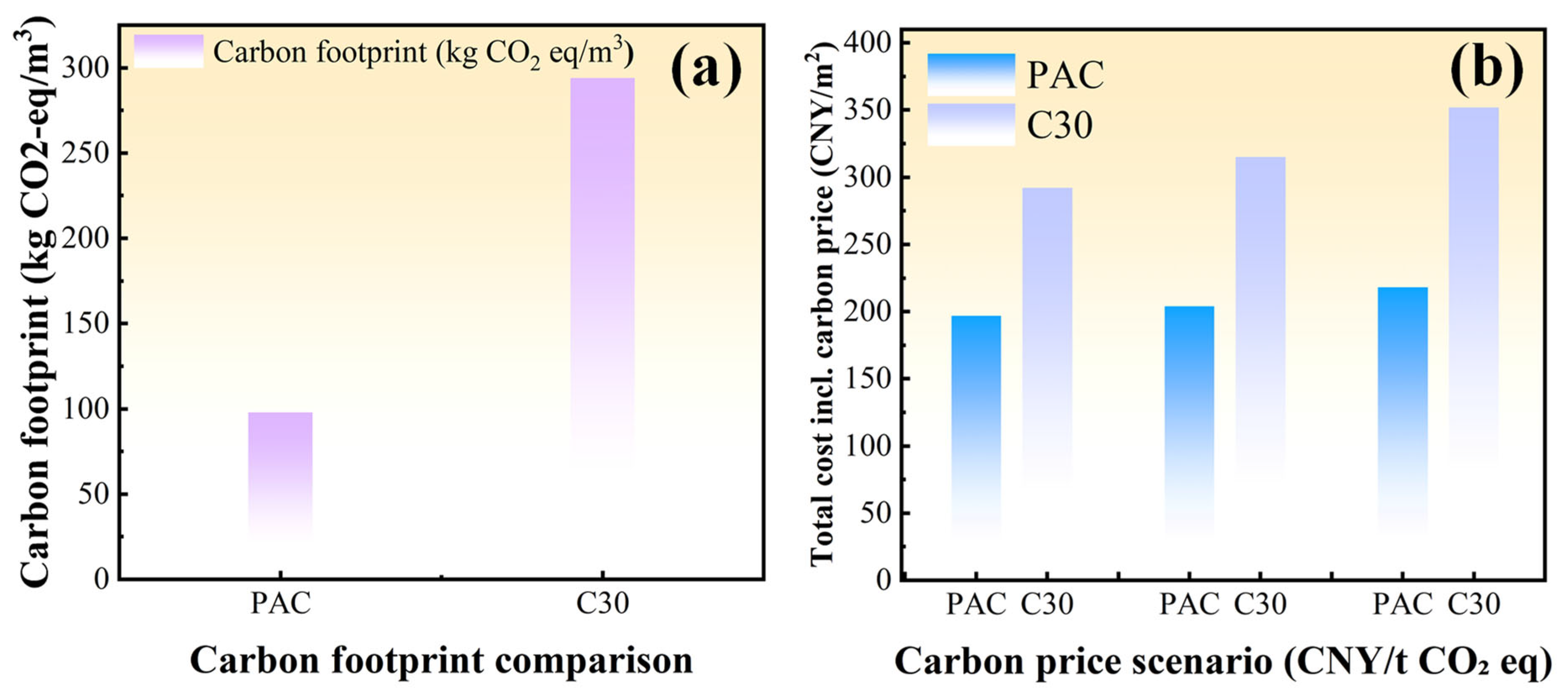

3.4. Economic Benefit Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Compressive strength and orthogonal analysis:

- (2)

- Toxicity leaching and salinity-interference mechanisms:

- (3)

- Strength loss in high-salinity environments and mitigation:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, D.M.; Fu, R.B.; Liu, H.Q.; Guo, X.P. Current knowledge from heavy metal pollution in Chinese smelter contaminated soils, health risk implications and associated remediation progress in recent decades: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, L.; Wang, S.B.; Ren, M.; Zhao, P.J.; Huang, Z.Y.; Jia, H.J.; Wang, J.H.; Lin, A.J. Comprehensive evaluation of the risk system for heavy metals in the rehabilitated saline-alkali land. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.X.; Fan, X.D.; Wang, X.Q.; Tang, Y.B.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Z.T.; Zhou, J.Y.; Han, Y.B.; Li, T. Bioremediation of a saline-alkali soil polluted with Zn using ryegrass associated with Fusarium incarnatum. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 312, 119929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, J.; Wang, Q.M.; Han, L.J.; Li, J.S. Synergistic remediation strategies for soil contaminated with compound heavy metals and organic pollutants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Chen, W.B.; Zhao, R.D.; Malik, N.; Yin, J.H.; Chen, Y.G. Investigation on solidified/stabilized behavior of marine soil slurry by lime-activated incinerated sewage sludge ash-ground granulated blast furnace slag under multifactor conditions. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 5264–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.T.; Liu, Z.B.; Song, M.; Liu, L.Q.; Liu, Z. Soil flushing for remediation of landfill leachate-contaminated soil: A comprehensive evaluation of optimal flushing agents and influencing factors. Waste Manag. 2025, 200, 114771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.M.; Fu, R.B.; Wang, J.X.; Shi, Y.X.; Guo, X.P. Chemical stabilization remediation for heavy metals in contaminated soils on the latest decade: Available stabilizing materials and associated evaluation methods-A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.M.M.; Rais, U.; Altaf, M.M.; Rasul, F.; Shah, A.; Tahir, A.; Nafees-Ur-Rehman, M.; Shaukat, M.; Sultan, H.; Zou, R.L.; et al. Microbial-inoculated biochar for remediation of salt and heavy metal contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.J.; Li, Q.; Peng, H.; Zhang, J.X.; Chen, W.J.; Zhou, B.C.; Chen, M. Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils with Soil Washing: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.P.; Xu, D.; Yue, J.Y.; Ma, Y.C.; Dong, S.J.; Feng, J. Recent advances in soil remediation technology for heavy metal contaminated sites: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Guo, B.L.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Huang, L.B.; Ok, Y.S.; Mechtcherine, V. Red mud-enhanced magnesium phosphate cement for remediation of Pb and As contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S.S.; Singh, J.; Taneja, P.K.; Mandal, A. Remediation techniques for removal of heavy metals from the soil contaminated through different sources: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 1319–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseer, U.; Ali, M.; Younis, M.A.; Du, Z.P.; Mushtaq, A.; Yousaf, M.; Qiu, C.T.; Yue, T.X. Sustainable Permeable Reactive Barrier Materials for Electrokinetic Remediation of Heavy Metals-Contaminated Soil. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2400722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.S. Characteristics and long-term effects of stabilized nanoscale ferrous sulfide immobilized hexavalent chromium in soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 122089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadoullahtabar, S.R.; Asgari, A.; Tabari, M.M.R. Assessment, identifying, and presenting a plan for the stabilization of loessic soils exposed to scouring in the path of gas pipelines, case study: Maraveh-Tappeh city. Eng. Geol. 2024, 342, 107747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.C.; Dong, Y.Q.; Zang, M.; Zou, N.C.; Lu, H.J. Mechanical properties and chemical microscopic characteristics of all-solid-waste composite cementitious materials prepared from phosphogypsum and granulated blast furnace slag. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.Y.; Jiang, H.; Qiu, Z.D.; Lv, M.R.; Cong, X.Y.; Wu, X.G.; Gong, J.; Yang, X.C.; Lu, S. Synergy effects of phosphogypsum on the hydration mechanism and mechanical properties of alkali-activated slag in polysilicon sludge solidification. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 456, 139386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Zhang, X.M.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Q.; Huang, P.C.; Zheng, C.J.; Liao, Q.; Yang, W.C. Reductive materials for remediation of hexavalent chromium contaminated soil—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.Q.; Zou, N.C.; Lan, J.R.; Zang, M.; Lu, H.J.; Huang, B.T. Ball milling modified phosphogypsum as active admixture: Milling kinetics and activation mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 488, 142158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Bai, J.D.; Chang, I.S.; Wu, J. A systematic review of phosphogypsum recycling industry based on the survey data in China—Applications, drivers, obstacles, and solutions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.T.; Cao, Y.H.; Guan, H.W.; Hu, Q.S.; Liu, Z.H.; Xu, J.; Hu, B.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Luo, R. Resource utilization and development of phosphogypsum-based materials in civil engineering. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Ding, J.W.; Mou, C.; Gao, M.Y.; Jiao, N. Role of Bayer red mud and phosphogypsum in cement-stabilized dredged soil with different water and cement contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, Y.J.; Zhang, W.Y.; Luo, X.H.; Feng, W.; Wang, R.; Yi, C.P.; Ai, Z.Y.; Zhang, H. Physicochemical Properties of the Rice Flour and Structural Features of the Isolated Starches from Saline-Tolerant Rice Grown at Different Levels of Soil Salinity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 7560, Erratum in J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17353–17361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Ding, J.W.; Wang, J.H.; Gao, P.J.; Wei, X. Evolution in macro-micro properties of cement-treated clay with changing ratio of red mud to phosphogypsum. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Bai, J.; Li, W.C.; Kong, L.X.; Xu, J.; Guhl, S.; Li, X.M.; Bai, Z.Q.; Li, W. Iron transformation behavior in coal ash slag in the entrained flow gasifier and the application for Yanzhou coal. Fuel 2019, 237, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.; Wang, S.M.; Wall, T.; Novak, F.; Lucas, J.; Hurst, H.; Patterson, J.; Happ, J. Dissolution of lime into synthetic coal ash slags. Fuel Process. Technol. 1998, 56, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Y.D.; Cao, Z.G. Immobilization of Cu (II), Ni (II) and Zn (II) in silica fume blended Portland cement: Role of silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; He, M.H.; Chen, H.; Rashad, A.M.; Liang, Y.S. Study on the curing conditions on the physico-mechanical and environmental performance of phosphogypsum-based artificial aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 415, 135030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Xu, L.; He, X.Y.; Su, Y.; Miao, W.J.; Strnadel, B.; Huang, X.P. Hydration and rheology of activated ultra-fine ground granulated blast furnace slag with carbide slag and anhydrous phosphogypsum. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 133, 104727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, A.U.; Selvasembian, R.; Ashiq, A.; Gunarathne, V.; Ekanayake, A.; Perera, V.O.; Wijesekera, H.; Mia, S.M.; Ahmad, M.; Vithanage, M.; et al. A systematic review on adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions: Recent advances. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 152055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yao, X.L.; Yao, Y.G.; Ren, C.Z.; Wu, C.L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.L. Recycling phosphogypsum as the sole calcium oxide source in calcium sulfoaluminate cement production and solidification of phosphorus. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.W. Meso-scale modeling of the influence of waste rock content on mechanical behavior of cemented tailings backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 307, 124473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ye, Y.; Yao, N.; Fu, F.; Hu, N. Study on Acoustic Emission Characteristics and Damage Mechanism of Mixed Aggregate Cemented Backfill Under Uniaxial Compression. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.D.; Li, X.B.; He, S.Y.; Zhou, S.T.; Zhou, Y.N.; Yang, S.; Shi, Y. Effect of mixing time on the properties of phosphogypsum-based cemented backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 210, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskini, S.; Mechnou, I.; Benmansour, M.; Remmal, T.; Samdi, A. Environmental investigation on the use of a phosphogypsum-based road material: Radiological and leaching assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miaomiao, W.; Weiguo, S.; Xing, X.; Li, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Huiying, S.; Gelong, X.; Qinglin, Z.; Guiming, W.; Wengsheng, Z. Effects of the phosphogypsum on the hydration and microstructure of alkali activated slag pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yao, X.L.; Ren, C.Z.; Yao, Y.G.; Wang, W.L. Recycling phosphogypsum as a sole calcium oxide source in calcium sulfoaluminate cement and its environmental effects. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yunzhi, T.; Changlin, Z.; Wenjing, S.; De’an, S.; Hang, Y.; Dongliang, X. Utilisation of silica-rich waste in eco phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials: Strength, microstructure, thermodynamics and CO2 sequestration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134469. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Shui, Z.H.; Sun, T.; Li, H.Y.; Chi, H.H.; Ouyang, G.S.; Li, Z.W.; Tang, P. Effect of MgO and superfine slag modification on the carbonation resistance of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials: Based on hydration enhancement and phase evolution regulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 415, 134914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Cui, K.; Yang, Y.; Chang, J. Investigation on the preparation of low carbon cement materials from industrial solid waste phosphogypsum: Clinker preparation, cement properties, and hydration mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Mo, K.H.; Tan, T.H.; Hung, C.C.; Yap, S.P.; Ling, T.C. Influence of calcination and GGBS addition in preparing β-hemihydrate synthetic gypsum from phosphogypsum. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J.J.; Hu, X.C.; Ran, B.; Huang, R.; Tang, H.Y.; Li, Z.; Li, B.W.; Wu, S.H. Modification of recycled cement with phosphogypsum and ground granulated blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Cui, W.; Chen, M.; Lu, H. Solidified Tailings-Contaminated Sludge as an Anti-Seepage Material for Solid Waste Landfills: Mechanical Characteristics and Microscopic Mechanisms. GeoStorage 2025, 1, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.X.; Zuo, X.B.; Yin, G.J.; Zhang, H.L.; Ding, F.B. Utilization of industrial wastes on the durability improvement of cementitious materials: A comparative study between FA and GGBFS. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 421, 135629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafshgarkolaei, H.J.; Lotfollahi-Yaghin, M.A.; Mojtahedi, A. A modified orthonormal polynomial series expansion tailored to thin beams undergoing slamming loads. Ocean Eng. 2019, 182, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | MgO | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | 55.49 | 16.95 | 8.23 | 3.05 | 16.28 |

| Phosphogypsum | 7.47 | 1.57 | 1.31 | 1.22 | 88.43 |

| Serial Number | PAC Coal Ash Calcination Conditions | Cr(VI) Concentration (mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcination Temperature | Calcination Time | ||

| PAC51S3 | 500 °C | 1 h | 30 |

| PAC52S6 | 500 °C | 2 h | 60 |

| PAC53S9 | 500 °C | 3 h | 90 |

| PAC61S6 | 600 °C | 1 h | 60 |

| PAC62S9 | 600 °C | 2 h | 90 |

| PAC63S3 | 600 °C | 3 h | 30 |

| PAC71S9 | 700 °C | 1 h | 90 |

| PAC72S3 | 700 °C | 2 h | 30 |

| PAC73S6 | 700 °C | 3 h | 60 |

| Serial Number | PAC Coal Ash Calcination Conditions | Cr(VI) Concentration (mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcination Temperature | Calcination Time | ||

| PAC0S3 | Uncalcined | Uncalcined | 30 |

| PAC0S6 | Uncalcined | Uncalcined | 60 |

| PAC0S9 | Uncalcined | Uncalcined | 90 |

| Factor | PAC Calcination Temperature | PAC Calcination Time | Cr(VI) Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean level 1 average (MPa) | 15.50 | 19.70 | 28.10 |

| Mean level 2 average (MPa) | 24.30 | 22.40 | 21.30 |

| Mean level 3 average (MPa) | 26.00 | 23.70 | 16.40 |

| Range (MPa) | 10.50 | 4.00 | 11.70 |

| Factor | PAC Calcination Temperature | PAC Calcination Time | Cr(VI) Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean level 1 average(μg/L) | 10.30 | 6.80 | 3.20 |

| Mean level 2 average(μg/L) | 5.80 | 6.20 | 6.00 |

| Mean level 2 average(μg/L) | 4.10 | 6.30 | 10.90 |

| Range(μg/L) | 6.20 | 0.60 | 7.70 |

| Sample | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Total Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Average Aperture (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAC63S3 | 60.8345 | 0.2155 | 14.1696 |

| PAC73S6 | 15.5274 | 0.0534 | 13.7563 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, Y.; Deng, A.; Mao, L.; Cai, G.; Zou, N.; Cui, W.; Lu, H.; Wan, S.; Liu, S. Mechanical Properties and Lattice Stabilization Mechanism of Phosphogypsum-Based Cementitious Materials for Solidifying Cr(VI)-Contaminated Soil in High Chloride Environments. Buildings 2026, 16, 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030631

Dong Y, Deng A, Mao L, Cai G, Zou N, Cui W, Lu H, Wan S, Liu S. Mechanical Properties and Lattice Stabilization Mechanism of Phosphogypsum-Based Cementitious Materials for Solidifying Cr(VI)-Contaminated Soil in High Chloride Environments. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):631. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030631

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Yiqie, Anhua Deng, Lianjie Mao, Guanghua Cai, Nachuan Zou, Wanyuan Cui, Haijun Lu, Sha Wan, and Shuhua Liu. 2026. "Mechanical Properties and Lattice Stabilization Mechanism of Phosphogypsum-Based Cementitious Materials for Solidifying Cr(VI)-Contaminated Soil in High Chloride Environments" Buildings 16, no. 3: 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030631

APA StyleDong, Y., Deng, A., Mao, L., Cai, G., Zou, N., Cui, W., Lu, H., Wan, S., & Liu, S. (2026). Mechanical Properties and Lattice Stabilization Mechanism of Phosphogypsum-Based Cementitious Materials for Solidifying Cr(VI)-Contaminated Soil in High Chloride Environments. Buildings, 16(3), 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030631