Preliminary Microclimate Monitoring for Preventive Conservation and Visitor Comfort: The Case of the Ligurian Archaeological Museum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Surveys and inspections: identification of critical/significant artifacts and monitoring needs, involving the curator in the process. During this phase, artifacts’ location (showcases or open environment) and the space logistics (visitor flow, HVAC systems) were analyzed. Technical challenges include installation constraints (size, security, and power source), which heavily influence sensor choice.

- Monitoring parameters and target values: preliminary ranges for human comfort and artifact preventive conservation were defined based on the information collected during surveys and inspections and the main standards requirements. This range will be adjusted after one year of data analysis.

- Sensors selection and installation: selection of the sensors to monitor the selected parameters, ensuring compliance with exhibition requirements and technical feasibility.

- Data analysis: preliminary analysis of daily trends, fluctuations, and compliance with selected ranges.

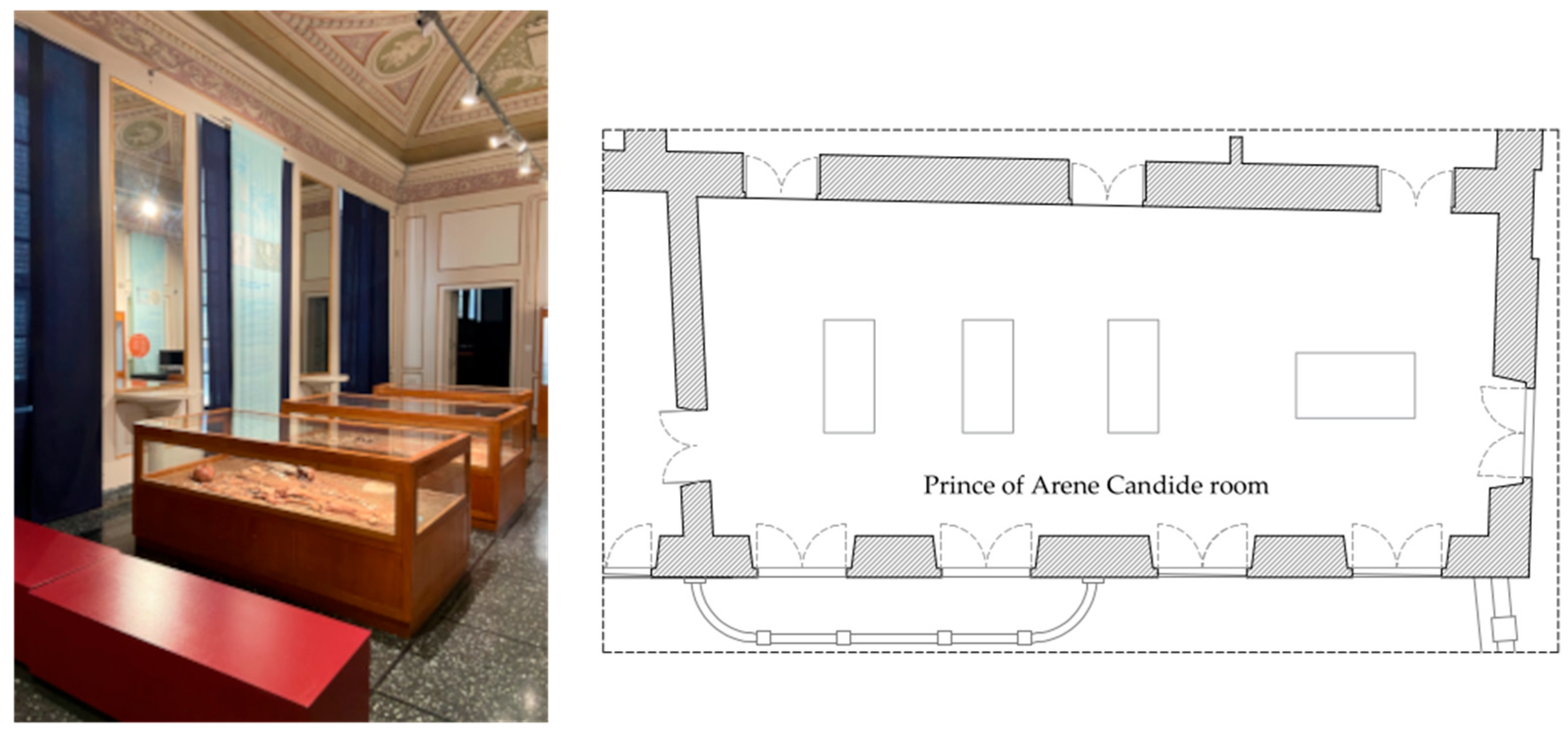

2.1. Surveys and Inspections

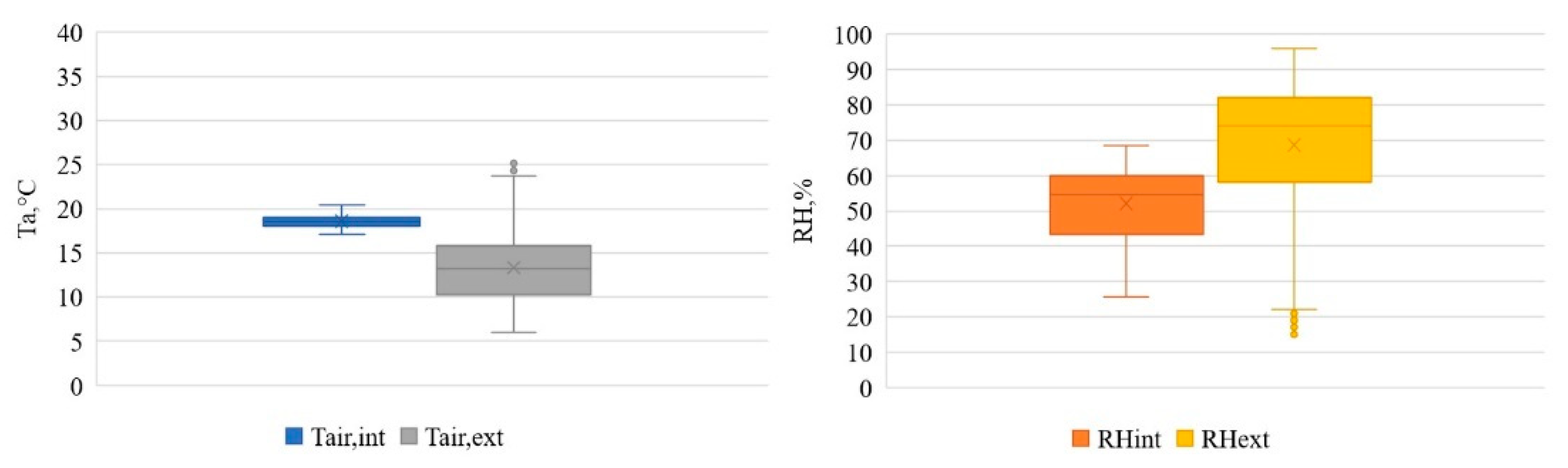

- Spring: from 16 April to 8 May 2024 in the PoAC room and from 16 to 23 April in the deposit.

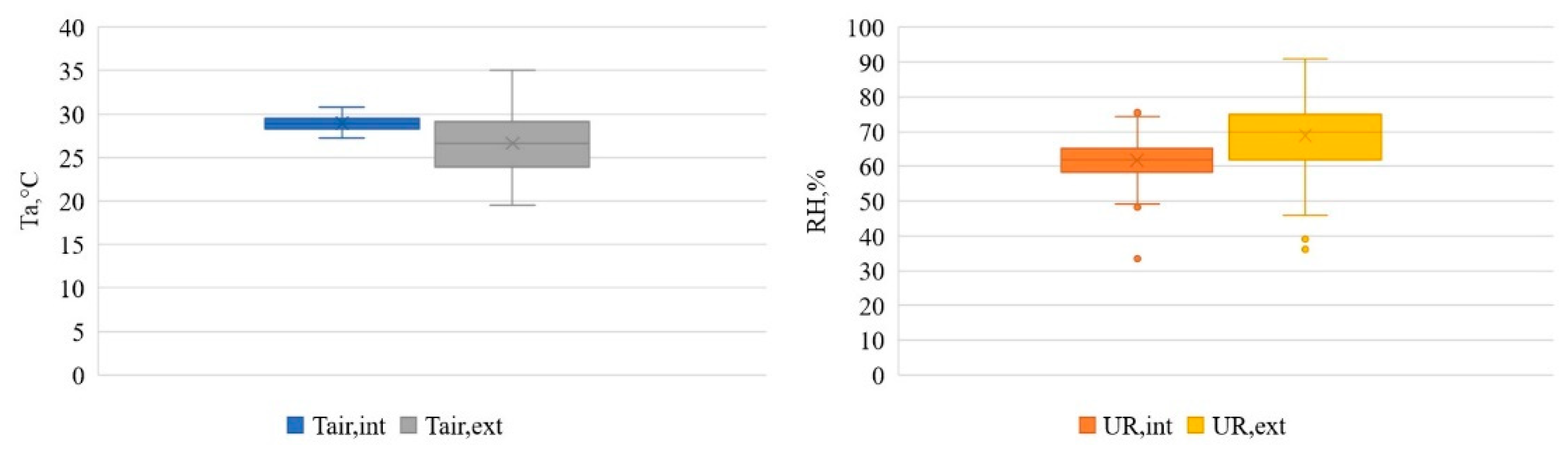

- Summer: from 23 July to 27 August 2024 in the PoAC room and deposit.

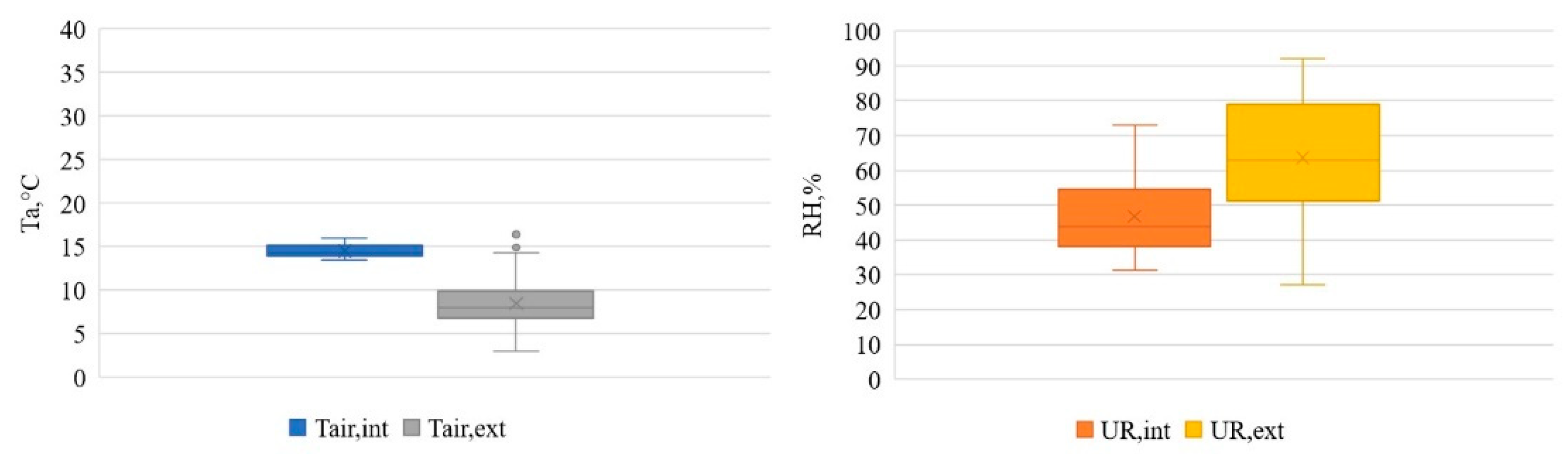

- Winter: from 8 to 22 January 2025 in the PoAC room and deposit.

2.2. Monitoring Parameters and Target Values

- Green: the measured value falls within the established value;

- Yellow: the measured value is within an alert range;

- Red: the measured value is outside the required range.

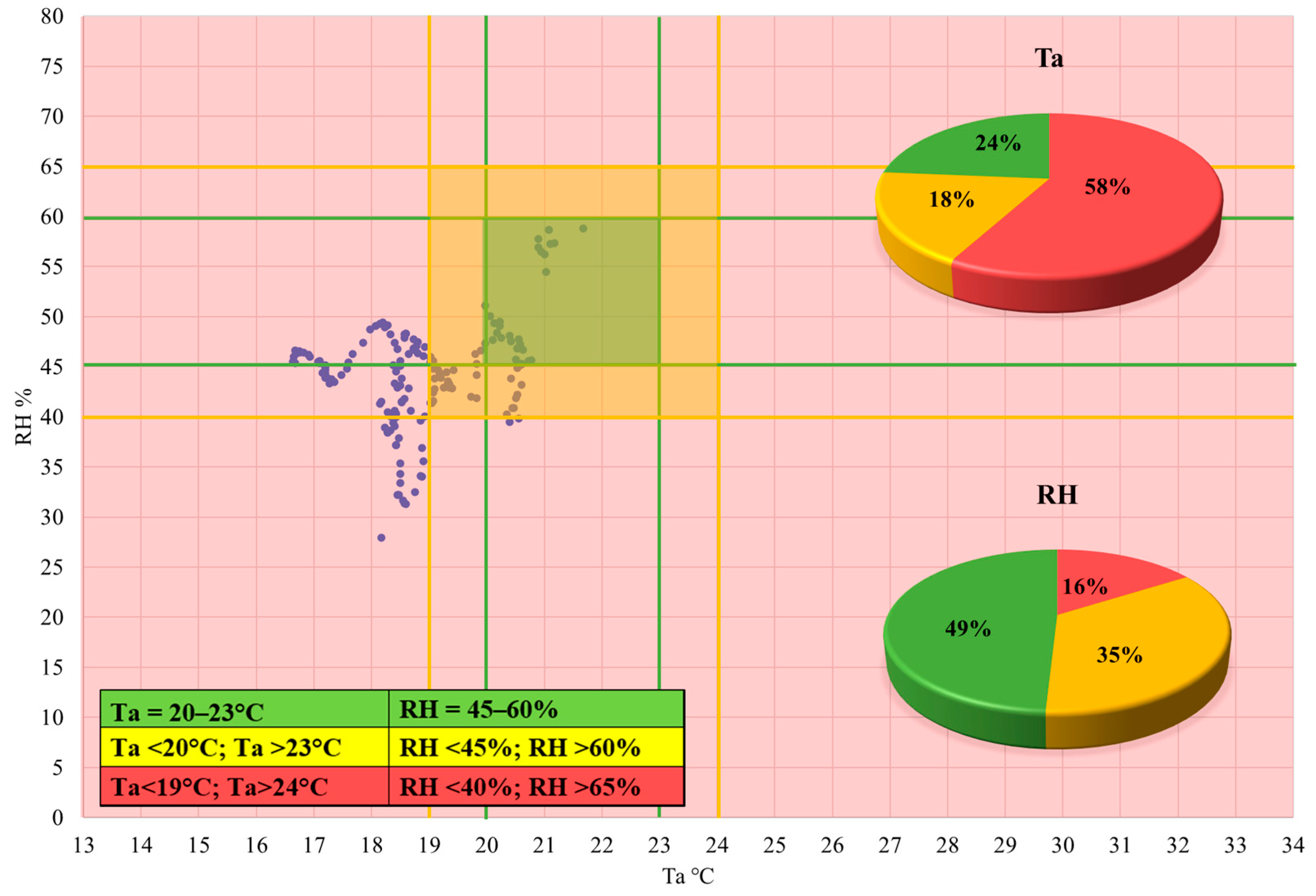

2.2.1. Range of Parameters for Human Comfort

2.2.2. Range of Parameters for Artifacts

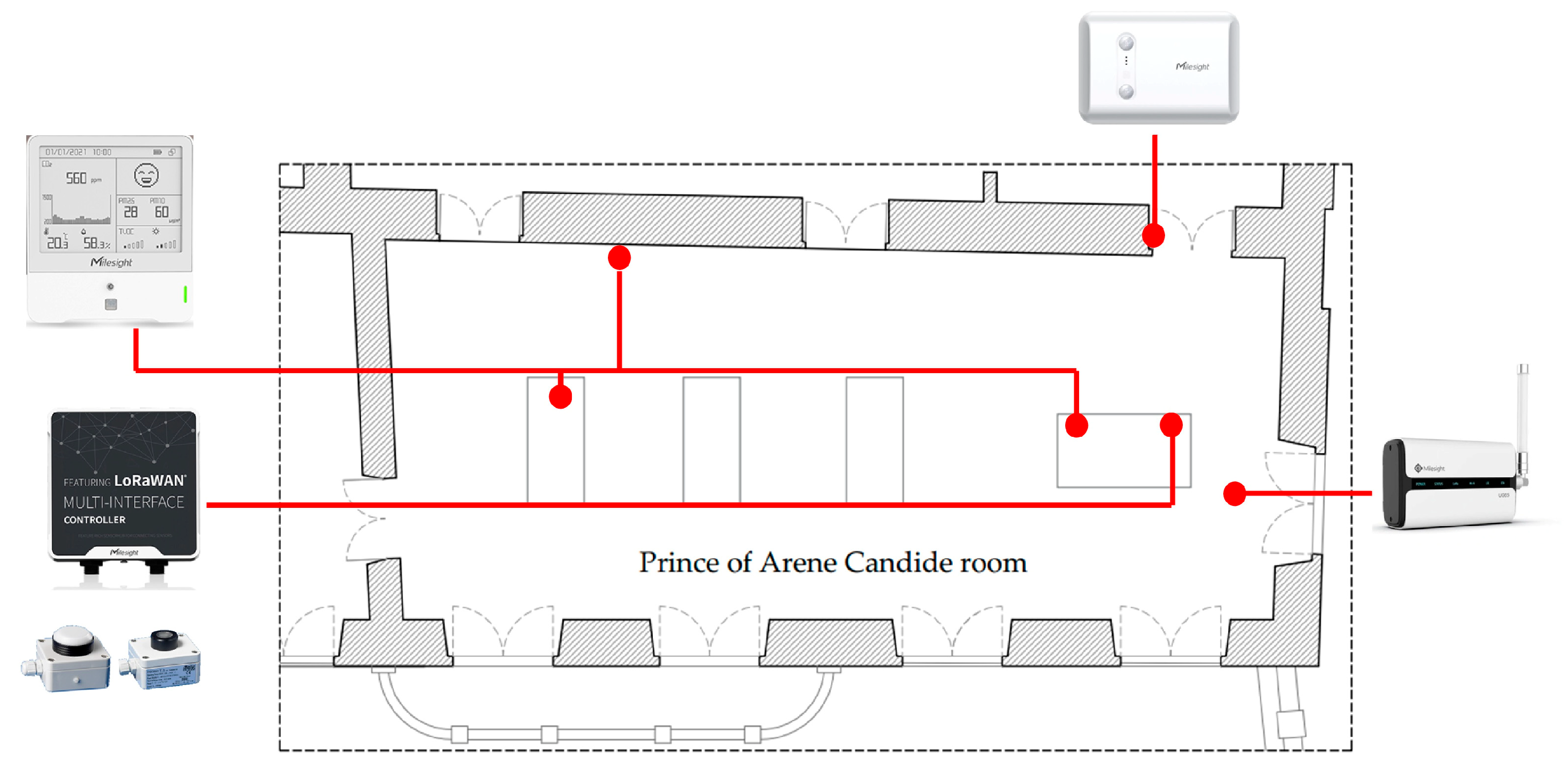

2.3. Sensor Selection and Installation

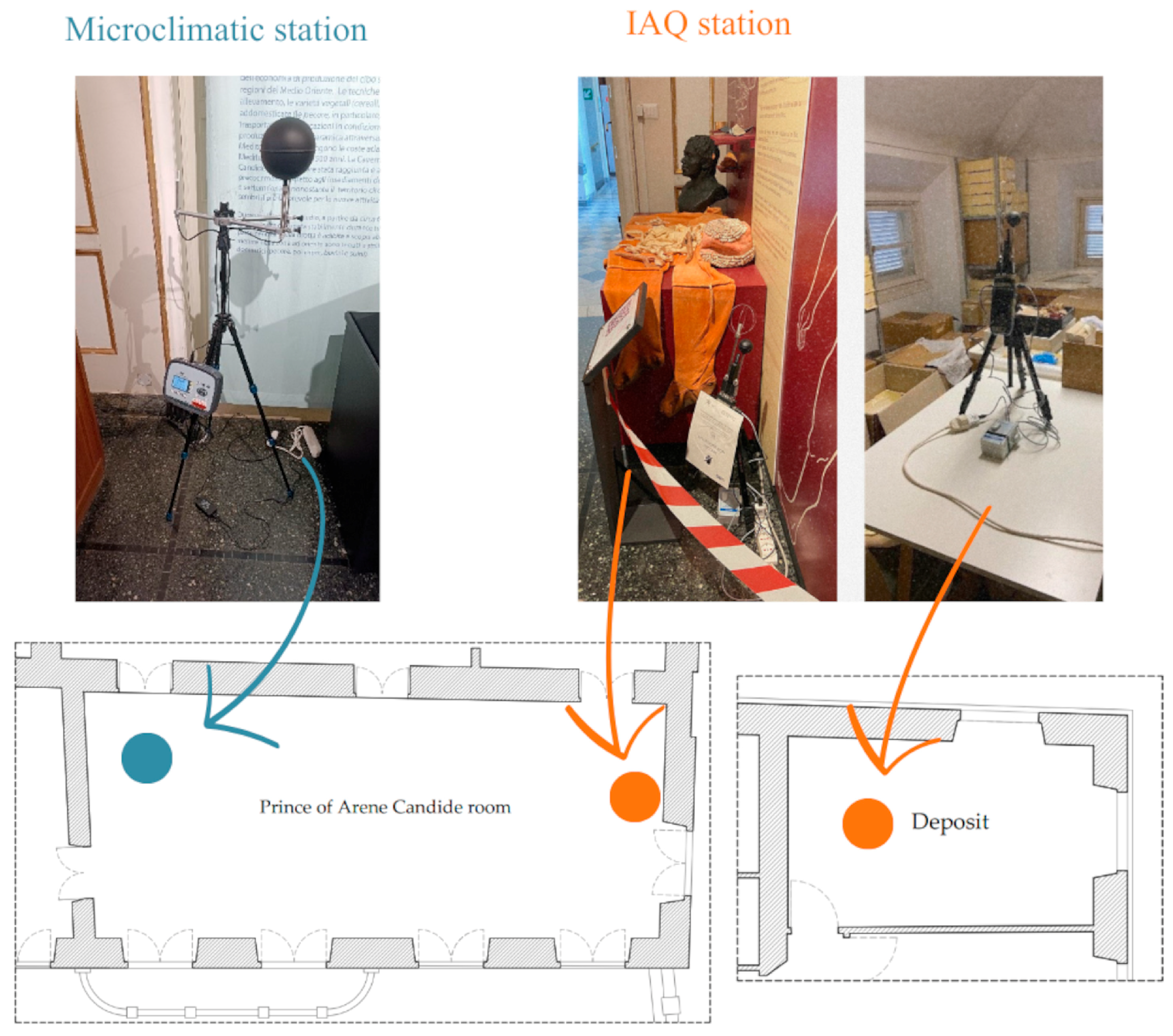

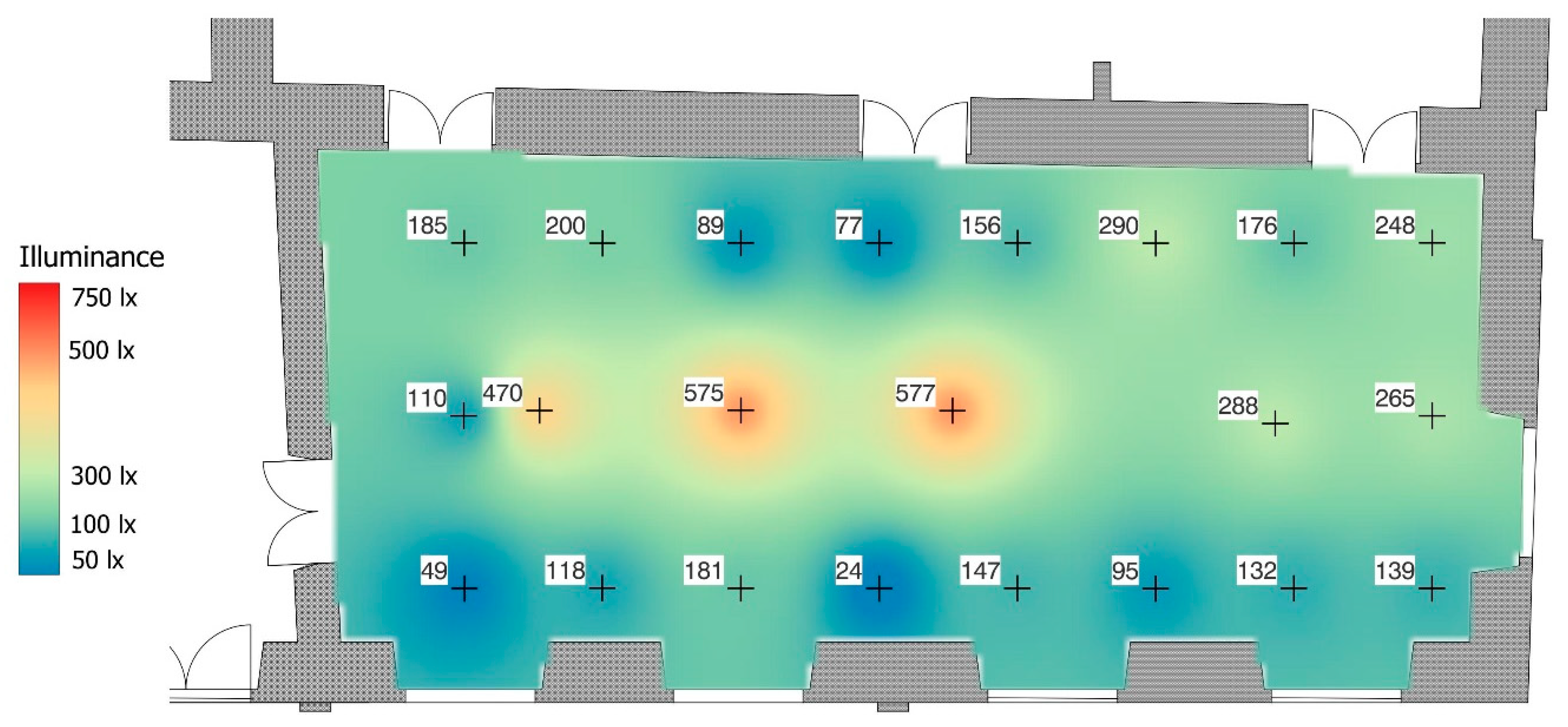

- Microclimatic Station [43]: a datalogger with a globe thermometer probe [44] (PT100 sensor), Φ150, for measuring the globe temperature; a combined temperature and relative humidity probe [45], capacitive RH sensor (5–98%, ±0.1%), Pt100 temperature sensor (−10 °C/80 °C, ±0.01 °C); an omnidirectional hot-wire probe [46] for measuring air velocity (0–5 m/s, ±0.3 m/s); a photometric probe [47] for measuring illuminance (0.1–200,000 lux). One of these was placed in a corner of the PoAC Room.

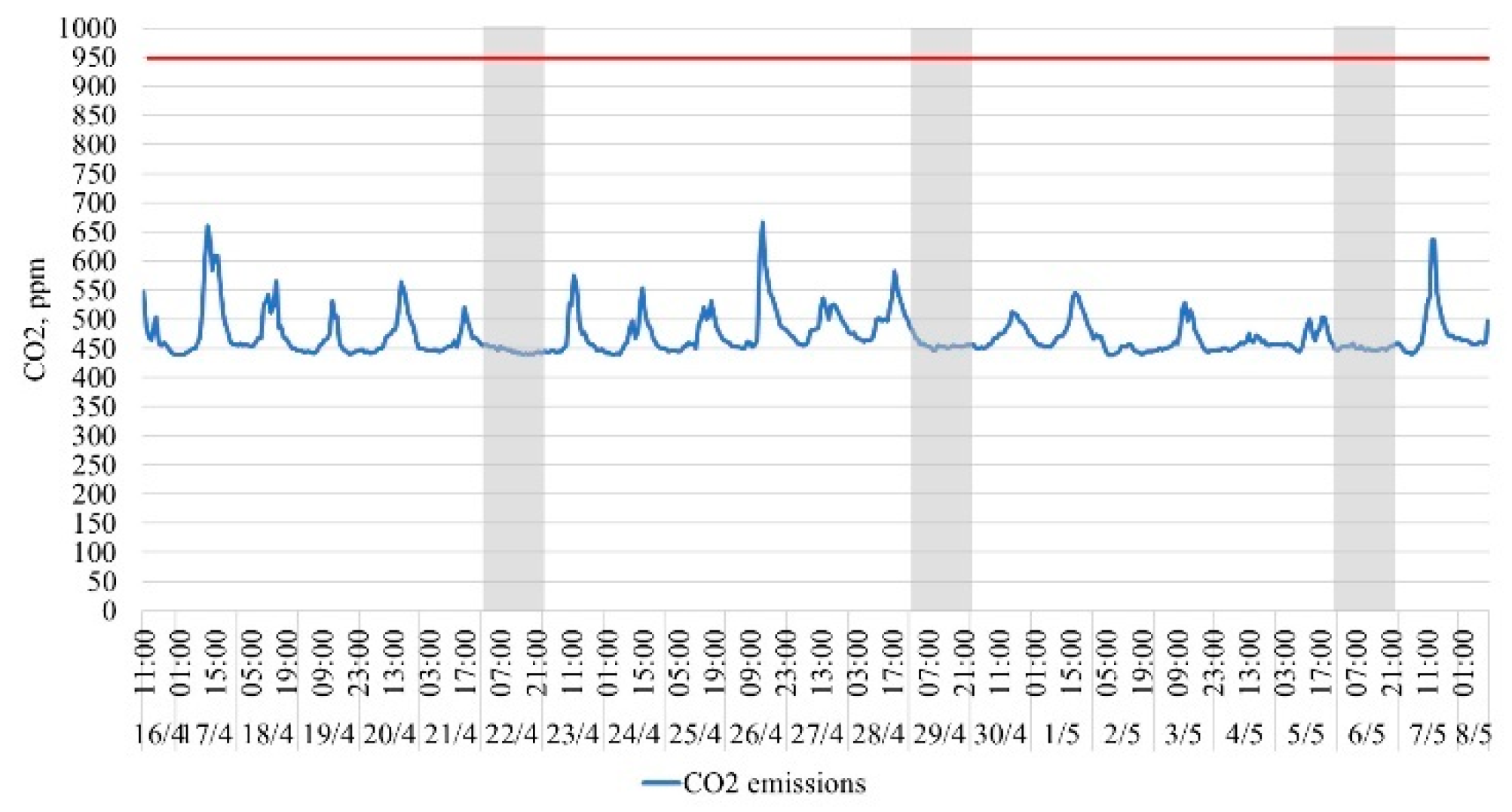

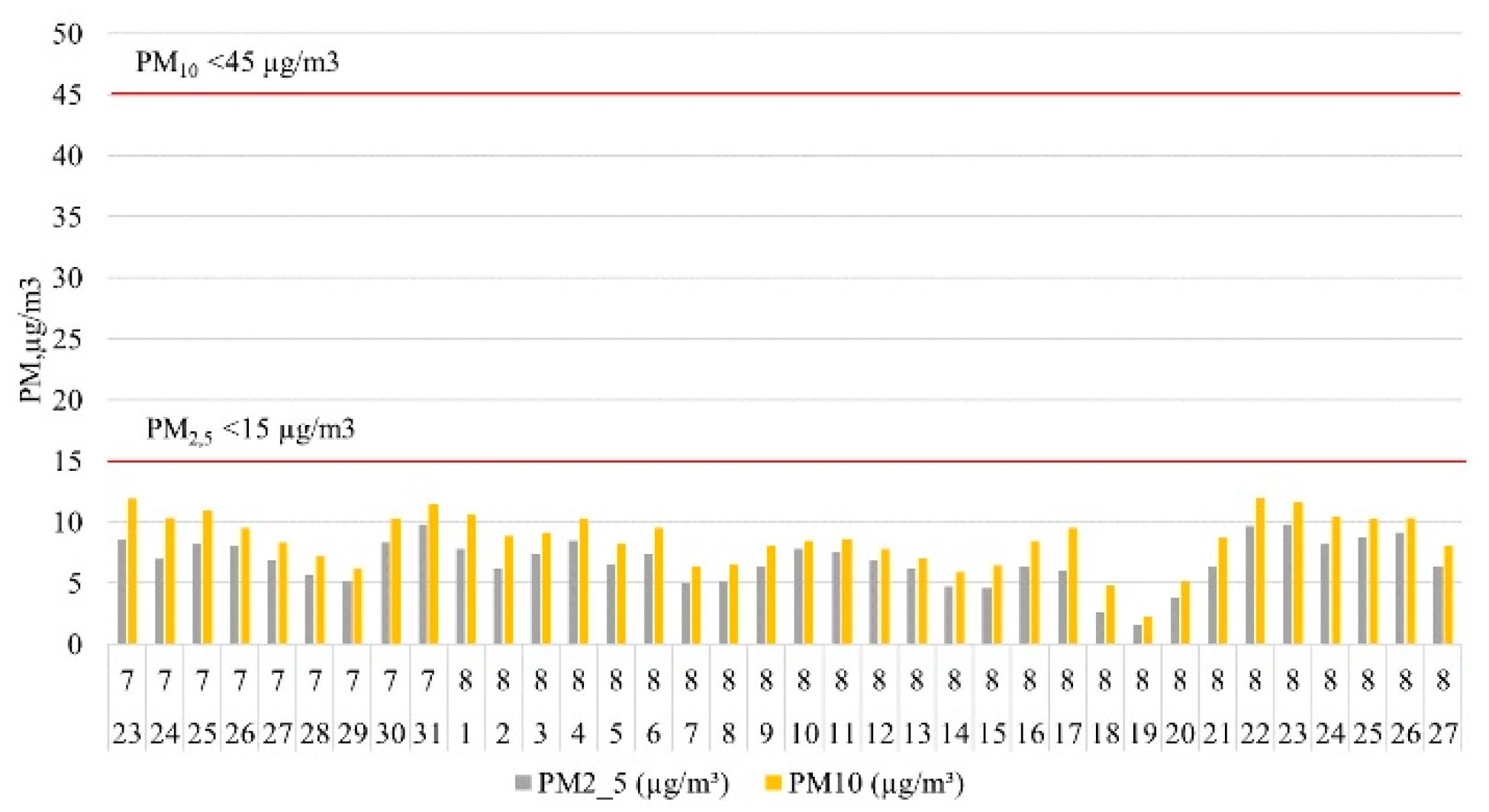

- IAQ Station [48]: a datalogger with Particulate Matter PM1, PM2.5, and PM10 Transmitter and a combined CO2 (0–5000 ppm, ±50 ppm + 3%), relative humidity (0 ÷ 100%, ±2%), temperature (−20 ÷ 80 °C, 0.1 °C), radiant temperature (−30 ÷ 120 °C, 0.1 °C), atmospheric pressure probe (300 ÷ 1250 hPa, ±0.5 hPa), TVOCs index (0–500). One of these was placed in a corner of the PoAC Room and one in the middle of the deposit.

2.4. Data Analysis

- The Deviation Index (DI) relates to conservation conditions and is evaluated as the percentage of time (or the percentage of measured data points) during which the detected environmental parameters fall outside the acceptable range of values.

- Frequency percentage describes the percentage of time in which a parameter falls in a specific range.

3. Results

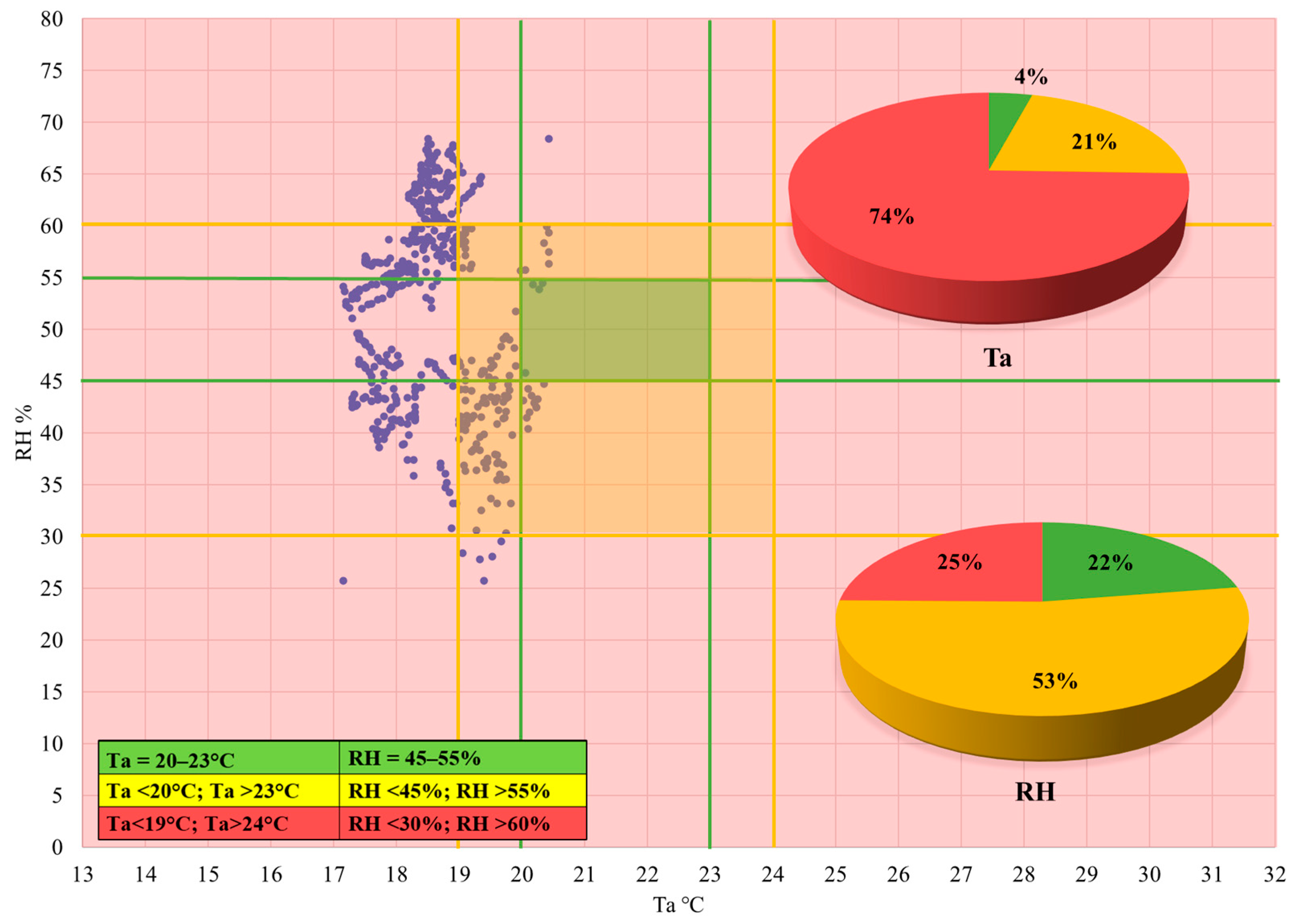

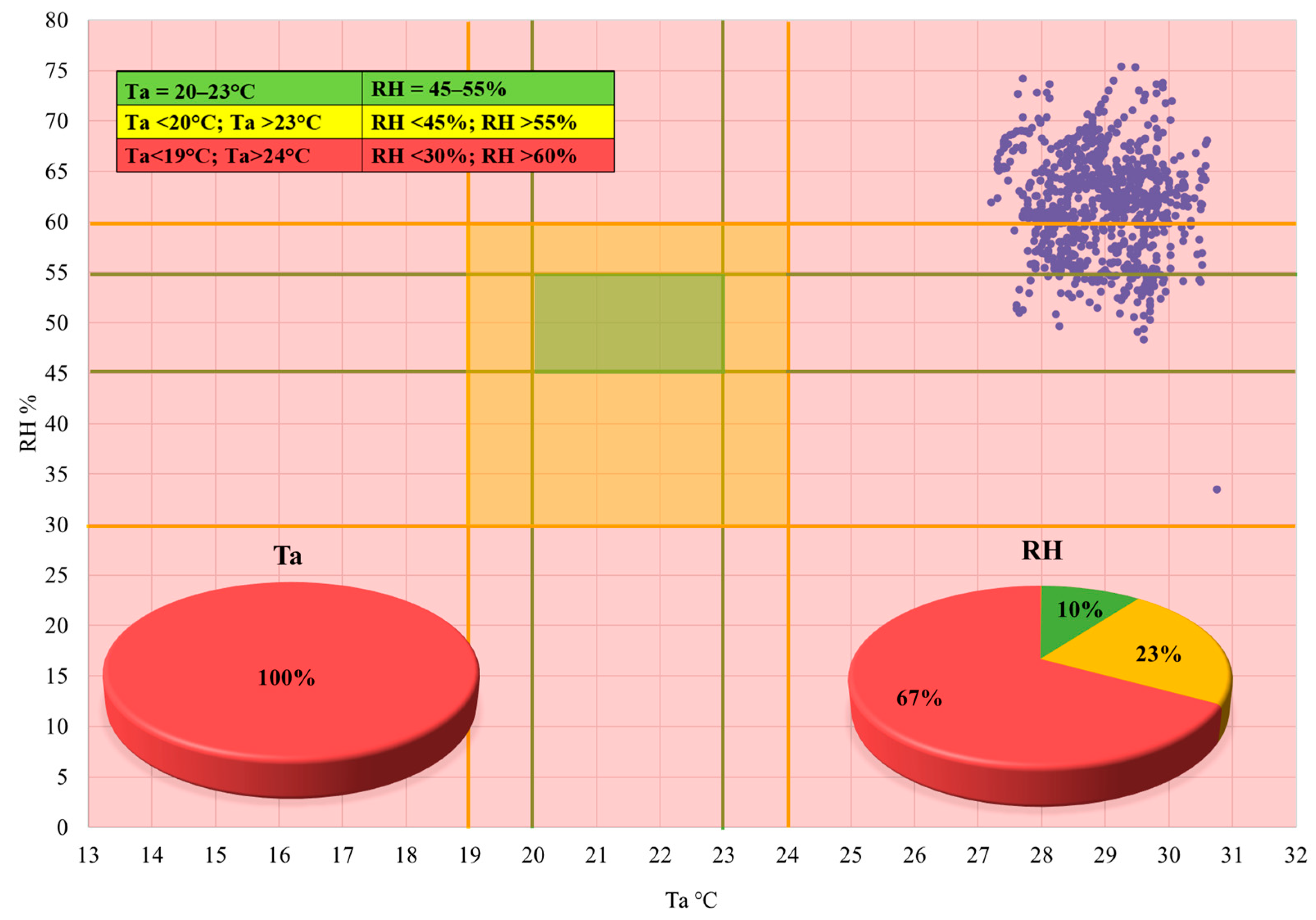

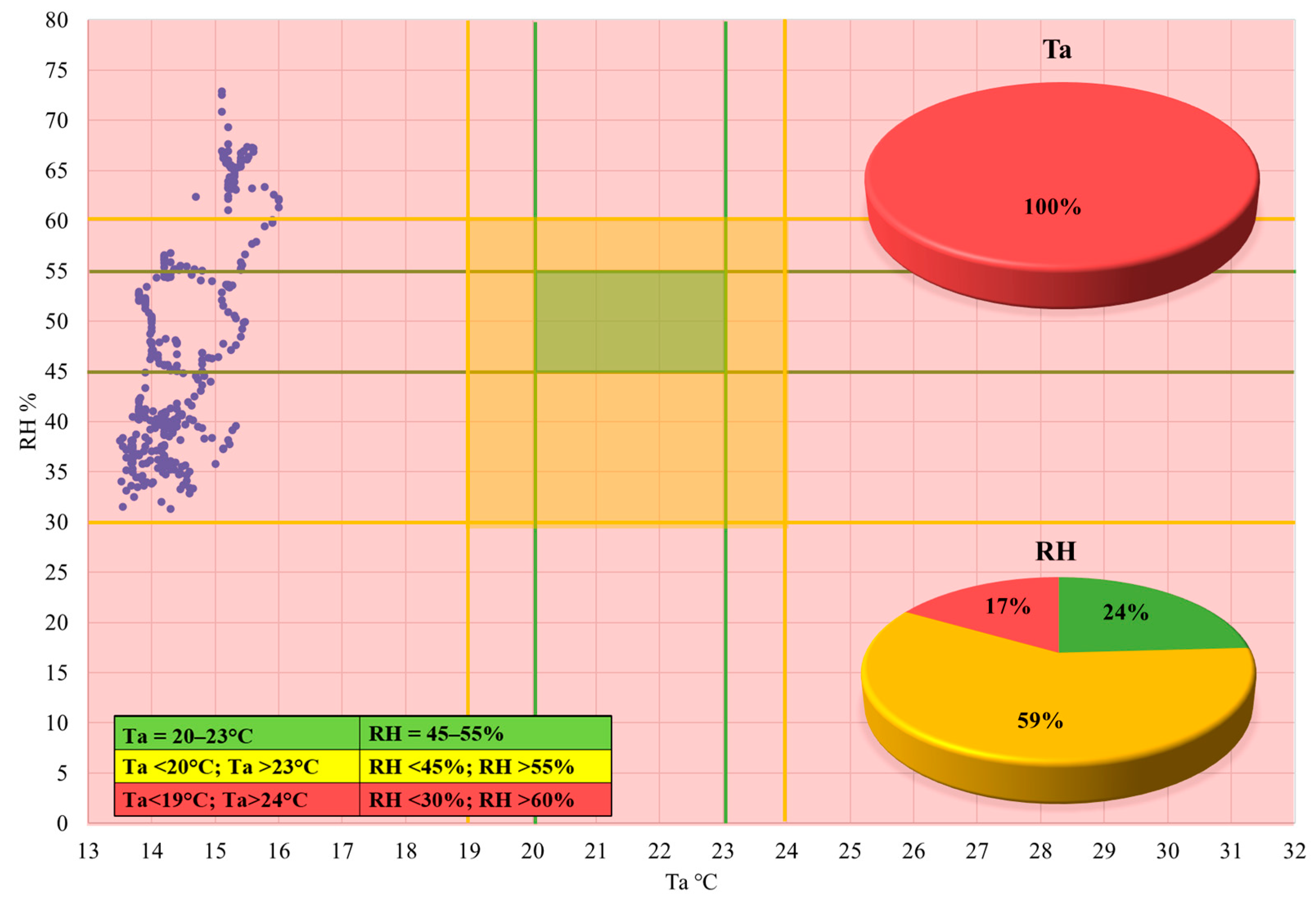

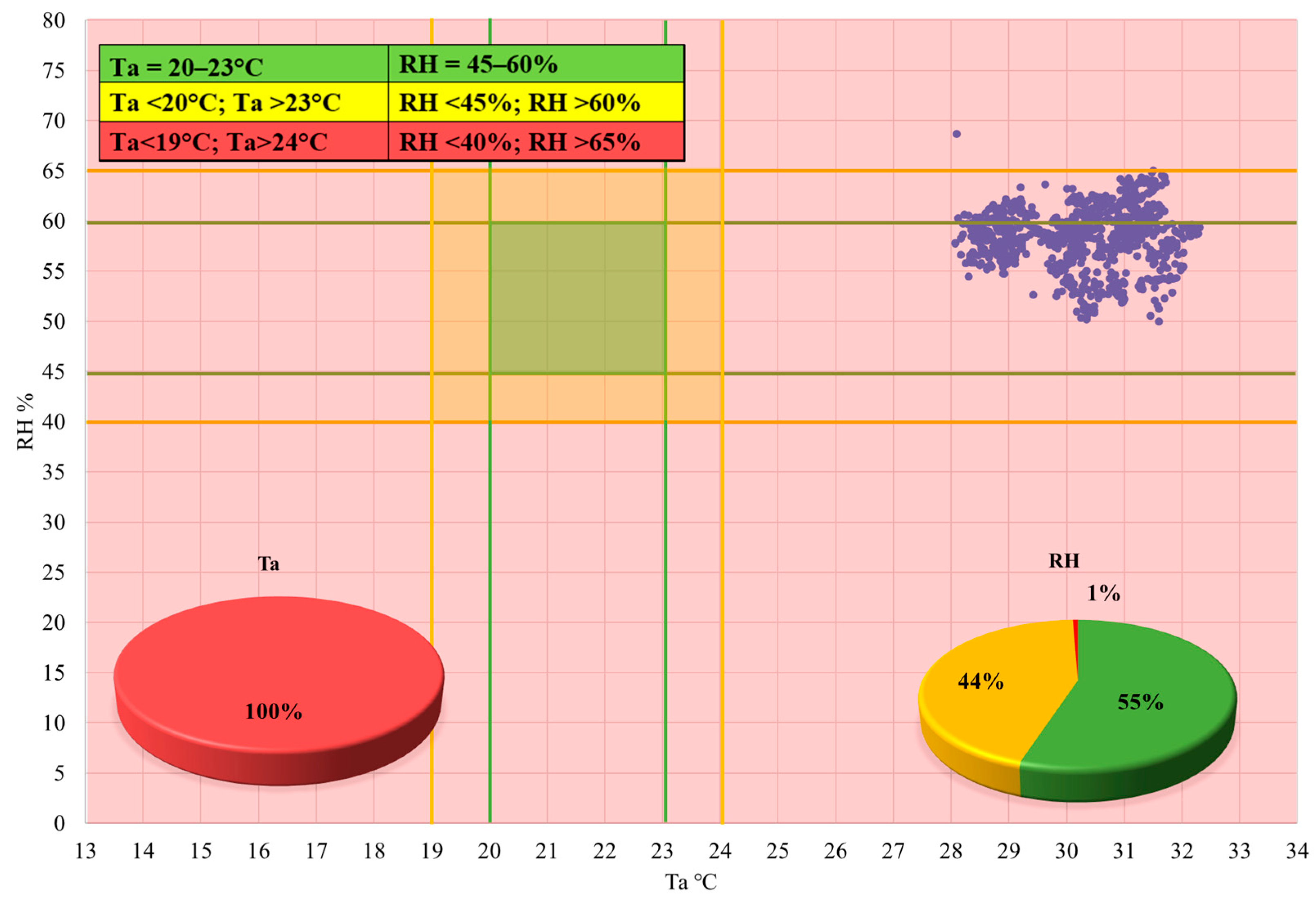

3.1. Prince of Arene Candide Room

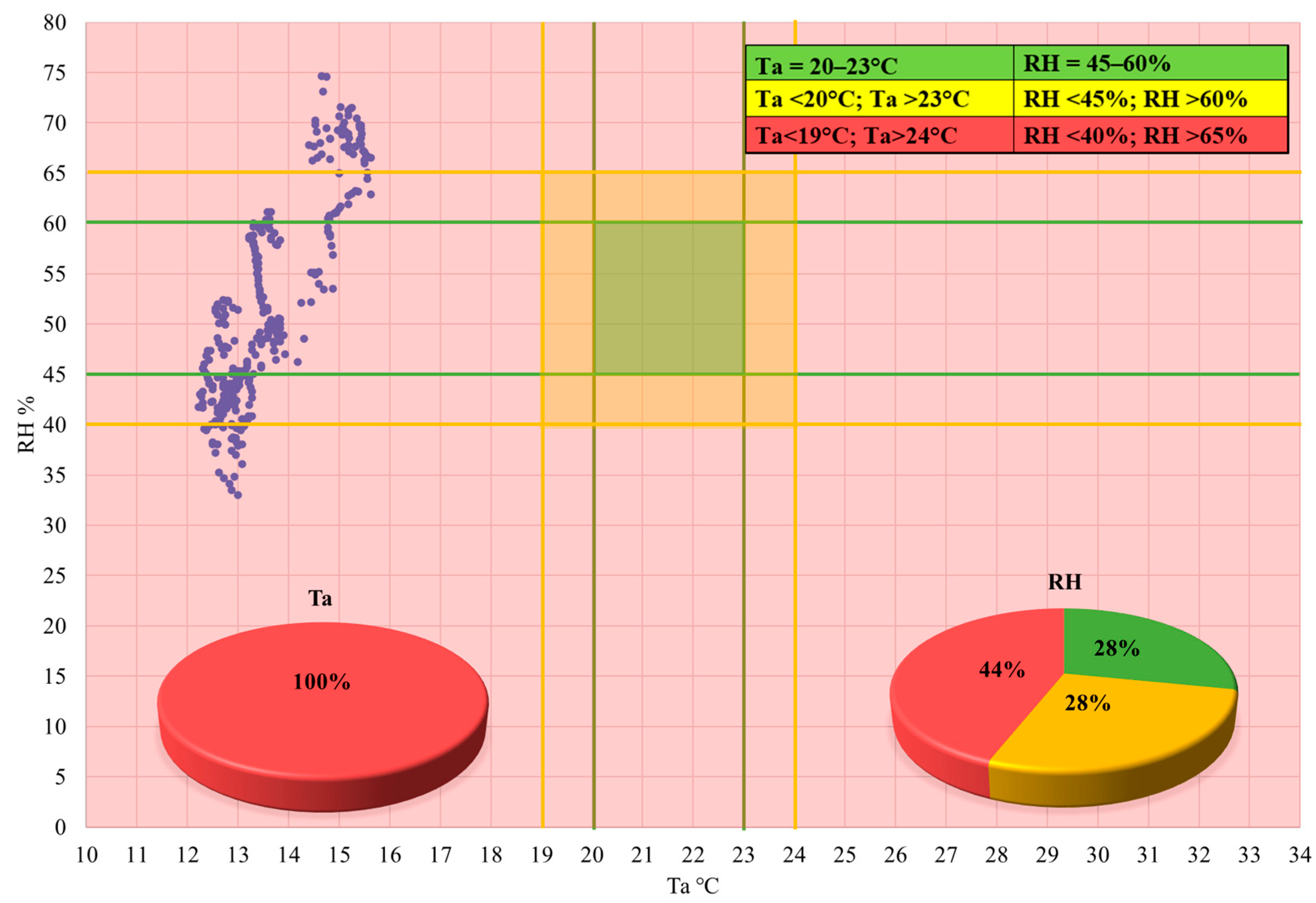

3.2. Deposit

3.3. Design of the Long-Term Monitoring Campaign

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ta | Air Temperature (°C) |

| DI | Deviation Index |

| PI | Global Performance Index |

| E | Illuminance (lux) |

| UVmax | Maximum amount of ultraviolet radiation (mW/lm) |

| LOmax | Maximum annual light dose (Mlx/h yr) |

| ΔTa,max | Maximum daily Air Temperature Range (°C) |

| ΔRHmax | Maximum daily Relative Humidity range (%) |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides (ppb) |

| O3 | Ozone (ppb) |

| PM10,24h | Particulate Matter with a diameter of 10 μm or less, 24 h mean (µg/m3) |

| PM2.5,24h | Particulate Matter with a diameter of 2.5 μm or less, 24 h mean (µg/m3) |

| PoAC room | Prince of Arene Candide’s room |

| RH | Relative Humidity (%) |

| SO2 | Sulfur Dioxide (ppb) |

References

- Weintraub, S. The Museum Environment: Adverse Consequences of Well-Intentioned Solutions. Collections 2006, 2, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, E.; Conti, P.; Urbanucci, L.; Testi, D. Multi-Objective Optimization of HVAC Control in Museum Environment for Artwork Preservation, Visitors’ Thermal Comfort and Energy Efficiency. Build. Environ. 2020, 180, 107018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, C.; Lescop, B.; Nguyen-Vien, G.; Rioual, S. The Deutsches Museum Spacesuit Display: Long-Term Preservation and Atmospheric Monitoring. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Review of Preventive Conservation in Museum Buildings. J. Cult. Heritage 2018, 29, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preventive Conservation. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/projects/preventive-conservation (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- ICOM-CC Terminology to Characterize the Conservation of Tangible Cultural Heritage. 2008. Available online: https://www.icom-cc.org/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- CEN Technical Bodies. CEN/TC 346 Conservation of Cultural Heritage 2022; CEN Technical Bodies: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- EN 15898:2019; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Main General Terms and Definitions. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- D.M. 113 21/02/2018; Adozione dei Livelli Minimi Uniformi di Qualità per i musei e i luoghi della cultura di appartenenza pubblica e attivazione del Sistema Museale Nazionale. Ministero Della Cultura: Rome, Italy, 2018.

- Atto di indirizzo sui criteri tecnico–scientifici e sugli standard di funzionamento e sviluppo dei musei; D.Lgs. n.112/98 art. 150 comma, 6, 2001; Ministero Della Cultura: Rome, Italy, 2001.

- UNI 10829:1999; Beni Di Interesse Storico e Artistico—Condizioni Ambientali Di Conservazione—Misurazione Ed Analisi. CTI–Comitato Termotecnico Italiano: Milan, Italia, 1999.

- Sciurpi, F.; Carletti, C.; Cellai, G.; Piselli, C. Assessment of the Suitability of Non-Air-Conditioned Historical Buildings for Artwork Conservation: Comparing the Microclimate Monitoring in Vasari Corridor and La Specola Museum in Florence. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 15757:2010; Conservation of Cultural Property—Specifications for Temperature and Relative Humidity to Limit Climate-Induced Mechanical Damage in Organic Hygroscopic Materials. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- Front Matter. In Microclimate for Cultural Heritage, 3rd ed.; Camuffo, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. i–ii. ISBN 978-0-444-64106-9. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/monograph/9780444641069/microclimate-for-cultural-heritage (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Bizot Green Protocol—National Museum Directors’ Council Website. Available online: https://www.nationalmuseums.org.uk/what-we-do/climate-crisis/bizot-green-protocol/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- AICCM Environmental Guidelines 2018. Available online: https://aiccm.org.au/conservation/environmental-guidelines/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- ASHRAE. ANSI/ASHRAE Chapter 24, Museums, Galleries, Archives and Libraries; ASHRAE Handbook–HVAC Applications; SI Edition: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-955516-50-1. [Google Scholar]

- ElAdl, M.; Fathy, F.; Morsi, N.K.; Nessim, A.; Refat, M.; Sabry, H. Managing Microclimate Challenges for Museum Buildings in Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletti, C.; Cellai, G.; Piselli, C.; Sciurpi, F.; Russo, G.; Schmidt, E.D. Uffizi Gallery Monitoring for IAQ Assessment. In Proceedings of the 52nd AiCARR International Conference “HVAC and Health, Comfort, Environment—Equipments and Design for IEQ and Sustainability”, Vicenza, Italy, 3–4 September 2022; Volume 343. [Google Scholar]

- Sciurpi, F.; Carletti, C.; Cellai, G.; Pierangioli, L. Environmental Monitoring and Microclimatic Control Strategies in “La Specola” Museum of Florence. Energy Build. 2015, 95, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, E.; Testi, D.; Grassi, W. A Proposal for New Microclimate Indexes for the Evaluation of Indoor Air Quality in Museums. Buildings 2016, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report ISTAT I MUSEI, LE AREE ARCHEOLOGICHE E I MONUMENTI IN ITALIA 2015. Available online: https://www.istat.it/en/press-release/museums-archeological-areas-and-monuments-in-italy-year-2015/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Varas-Muriel, M.J.; Gómez-Marfil, A.; Álvarez De Buergo, M.; Fort, R. Temporary Monitoring of the Microclimate in a Museum without Climate Control and Its Implications in the Preventive Conservation of Collections. Build. Environ. 2025, 284, 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16893:2018; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Specifications for Location, Construction and Modification of Buildings or Rooms Intended for the Storage or Use of Heritage Collections. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Kramer, R.; van Schijndel, J.; Schellen, H. Dynamic Setpoint Control for Museum Indoor Climate Conditioning Integrating Collection and Comfort Requirements: Development and Energy Impact for Europe. Build. Environ. 2017, 118, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Multidisciplinary Risk-Based Analysis for Supporting the Decision Making Process on Conservation, Energy Efficiency, and Human Comfort in Museum Buildings. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 22, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Simplified Assessment Method for Environmental and Energy Quality in Museum Buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 117, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, P.; Innella, C.; Marghella, G.; Marzo, A.; Tripepi, C. Monitoring for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage and Visitor Satisfaction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 595 LNCE, pp. 406–414. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Maya, I.; Rubio-Bellido, C. Use of International Adaptive Thermal Comfort Models as a Strategy for Adjusting the Museum Environments of the Mudejar Pavilion, Seville. Energies 2024, 17, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieș, A.; Caciora, T.; Marcu, F.; Berdenov, Z.; Ilieș, G.; Safarov, B.; Hodor, N.; Grama, V.; Shomali, M.A.A.; Ilies, D.C.; et al. Analysis of the Interior Microclimate in Art Nouveau Heritage Buildings for the Protection of Exhibits and Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkadi, H.; Al-Maiyah, S.; Fielder, K.; Kenawy, I.; Martinson, D.B. The Regulations and Reality of Indoor Environmental Standards for Objects and Visitors in Museums. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldan, M.; Manente, S.; Izzo, F.C. The Role of Bio-Pollutants in the Indoor Air Quality of Old Museum Buildings: Artworks Biodeterioration as Preview of Human Diseases. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilieş, D.C.; Marcu, F.; Caciora, T.; Indrie, L.; Ilieş, A.; Albu, A.; Costea, M.; Burtă, L.; Baias, Ş.; Ilieş, M.; et al. Investigations of Museum Indoor Microclimate and Air Quality. Case Study from Romania. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, A.L.; Castaldo, V.L.; Piselli, C.; Cotana, F. Coupling Artworks Preservation Constraints with Visitors’ Environmental Satisfaction: Results from an Indoor Microclimate Assessment Procedure in a Historical Museum Building in Central Italy. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 27, 846–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligurian Archaeological Museum|Museums in Genoa. Available online: https://www.museidigenova.it/en/archeological-museum-liguria (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings—Ventilation for Buildings—Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- EN ISO 7730:2005; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; Wolrd Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003422-8. [Google Scholar]

- EN 12464-1:2021; Light and Lighting—Lighting of Work Places—Part 1: Indoor Work Places. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- UNI EN 16163:2024; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Guidelines and Procedures for Choosing Appropriate Lighting for Indoor Exhibitions. CTI–Comitato Termotecnico Italiano: Milan, Italia, 2024.

- EN 7726:2025; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Instruments for Measuring and Monitoring Physical Quantities. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- EN 15758:2010; Conservation of Cultural Property—Procedures and Instruments for Measuring Temperatures of the Air and the Surfaces of Objects. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- Senseca. HD32.1—Thermal Microclimate Data Logger—Microclimate—Thermal Comfort. Available online: https://environmental.senseca.com/product/hd32-1-thermal-microclimate-data-logger-2/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Senseca. TP3275—Globe Temperature Probe—Microclimate—Thermal Comfort. Available online: https://environmental.senseca.com/product/tp3275-globe-temperature-probe-2/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Senseca. HP3217R—Combined RH and Temperature Probe—Microclimate—Thermal Comfort. Available online: https://environmental.senseca.com/product/hp3217r-combined-rh-and-temperature-probe-2/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Senseca. AP3203—Omnidirectional Hotwire Probe—Microclimate—Thermal Comfort. Available online: https://environmental.senseca.com/product/ap3203-omnidirectional-hotwire-probe-2/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Senseca. LP471PHOT—Illuminance Probe—Light. Available online: https://environmental.senseca.com/product/lp471phot-illuminance-probe-2/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Senseca. HD32.3TC—HD32.3TCA—Thermal Microclimate PMV-PPD/WBGT—Microclimate—Thermal Comfort. Available online: https://environmental.senseca.com/product/hd32-3tc-thermal-microclimate-pmv-ppd-wbgt/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Corgnati, S.P.; Fabi, V.; Filippi, M. A Methodology for Microclimatic Quality Evaluation in Museums: Application to a Temporary Exhibit. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambiente in Liguria: Meteo. Available online: https://ambientepub.regione.liguria.it/SiraQualMeteo/script/PubAccessoDatiMeteo.asp (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Camuffo, D.; Pagan, E. What Is behind Relative Humidity? Why It Is so a Relevant Variable in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage? In European University Centre for Cultural Heritage; European University Centre for Cultural Heritage: Bari, Italy, 2006; pp. 21–38. ISBN 978-88-7228-447-6. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265793107_What_is_behind_Relative_Humidity_Why_it_is_so_a_relevant_variable_in_the_conservation_of_Cultural_Heritage (accessed on 26 January 2026).

| Survey Domain | Relevant Survey Parameters | Technical and Operational Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| Kind of artifacts | Type and complexity of artifacts (different materials, significance) to identify the technical requirements of the sensors to be installed | Technical requirements of the sensors typology to be installed: accuracy, range of measurements, resolution |

| Typology of show cases and environmental layout and features (Hvac and lighting systems) | Aesthetics, Invasiveness, Exhibition requirements, Security, Connections, Superintendency interventions and requirements | Technical requirements of the sensors network to be installed: type of power management, type of connection etc |

| Tawinter (°C) | Tasummer (°C) | RHwinter (%) | RHsummer (%) | CO2 (ppm) | PM2.5,24h (µg/m3) | PM10,24h (µg/m3) | E (lux) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19–22 | 24–26 | 40–50 | 50–60 | <950 | <15 | <45 | 300–500 |

| <19 or >22 | <24 or >26 | <40 or <60 | <50 or <70 | <1200 | <20 | <50 | <300 or >500 |

| <18 or >23 | <23 or >27 | <30 or >60 | <40 or >70 | >1200 | >20 | >50 | <200 or >1000 |

| Material of Preserved Artifacts | Ta (°C) | ΔTamax (°C) | RH (%) | ΔRHmax (%) | Emax (lx) | UVmax (µW/lm) | LOmax (Mlx/h yr) | Ref. Standard UNI 10829:1999 | Ta (°C) | RH (%) | Ref. D.M. 10.05.2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal remains | <4 | - | Into saturated air | - | - | - | - | Organic materials from wet excavation areas (before treatment) | 19–24 | 45–65 | Ivories and bones |

| 21 ÷ 23 | 1.5 | 20 ÷ 35 | - | 50 | 75 | 0.2 | Dried animals, anatomical organs, and mummies | ||||

| Faunal remains | 21 ÷ 23 | 1.5 | 20 ÷ 35 | - | 50 | 75 | 0.2 | Dried animals, anatomical organs, and mummies | 15–21 | 45–60 | Furs and feathers |

| 4 ÷ 10 | 1.5 | 30 ÷ 50 | 5 | 50 | 75 | 0.2 | Furs and feathers, taxidermied animals, and birds | ||||

| Mammoth ivory ornaments Elk horn artifacts, shell, and deer-element ornaments Marine shells and faunal elements | 19 ÷ 24 | 1.5 | 40 ÷ 60 | 6 | 150 | 75 | 0.5 | Ivories, horns, malacological collections, eggs, nests, and corals | 19–24 | 45–65 | Ivories and bones |

| Soil and rocks from the burial excavation | 19 ÷ 24 | - | 40 ÷ 60 | 6 | NR * | - | - | Stones, rocks, minerals, meteorites (non-porous), fossils, and stone collections | ≤30 | 45–60 | Mineralogical collections, marbles, and stones |

| Material of Preserved Artifacts | Ta °C | ΔTamax °C | RH % | ΔRHmax % | Emax lx | UVmax µW/lm | LOmax Mlx/h anno | Ref. Standard UNI 10829:1999 | Ta (°C) | RH (%) | Ref. D.M. 10.05.2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramics | NR | - | NR | 10 | NR | - | - | Porcelains, ceramics, stoneware, terracotta, and tiles (non-excavated, and excavated if demineralized) | - | - | - |

| Bronze, Iron, and Silver Artifacts (or Metal Artifacts) | NR * | - | <50 | - | NR * | - | - | Metals, polished metals, metal alloys, silver items, armors, weapons, bronzes, coins, marble objects, tin, iron, steel, lead, and pewters | - | - | - |

| Faunal Remains and Bone Artifacts | 21 ÷ 23 | 1.5 | 20 ÷ 35 | - | 50 | 75 | 0.2 | Animals, dried anatomical organs, and mummies | 19–24 | 45–65 | Ivories and bones |

| Vegetal Remains (Wood, Seeds, and Charcoals) | 19 ÷ 24 | 1.5 | 45 ÷ 60 | 4 | 150 | 75 | 0.5 | Unpainted wood sculptures, wicker objects, and wood or bark panels | 19–24 | 40–65 | Wood |

| Stone Artifacts and Amber Objects | 19 ÷ 24 | - | 40 ÷ 60 | 6 | NR * | - | - | Stones, rocks, minerals, meteorites (non-porous), fossils, and stone collections | ≤30 | 45–60 | Mineralogical collections, marbles, and stones |

| Glass Paste Objects | 20 ÷ 24 | 1.5 | 40 ÷ 45 | - | 150 | 75 | 0.5 | Unstable glass, iridescent, sensitive, and sensitive glass mosaics | 25–60 | Glass and stable glazing |

| Ta (°C) | ΔTamax (°C) | RH (%) | ΔRHmax (%) | CO2 (ppm) | PM2.524h (µg/m3) | PM1024h (µg/m3) | Emax (lux) | UVmax (µW/lm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–23 | 1.5 | 45–55 | 6 | <950 | <15 | <45 | <50 | <10 |

| <20 or >23 | 1.5 | <45 or >55 | 6 | <1200 | <20 | <50 | <70 | <75 |

| <19 or >24 | 1.5 | <30 or >60 | >6 | >1200 | >20 | >50 | >70 | >75 |

| Ta (°C) | ΔTamax (°C) | RH (%) | ΔRHmax (%) | CO2 (ppm) | PM2.5,24h (µg/m3) | PM10,24h (µg/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–23 | 1.5 | 45–60 | <4 | <950 | <15 | <45 |

| <20 or >23 | 1.5 | <45 or >60 | >4 | <1200 | <20 | <50 |

| <19 or >24 | 1.5 | <40 or >65 | >6 | >1200 | >20 | >50 |

| Period | Tmean (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Tmin (°C) | ∂Ta24h,max (°C) | RHmean (%) | RHmax (%) | RHmin (%) | ∂UR24h,max (%) | Radmax W/m2 | Rain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 13.5 | 25.5 | 6.0 | 11.2 | 68.2 | 96 | 15 | 60 | 780 | Cumulative: 101 mm, with 56 mm on May 1st–2nd and a peak on 7th with 17 mm |

| Summer | 26.6 | 35.0 | 19.5 | 11.40 | 68.9 | 91 | 36 | 47 | 742 | Cumulative: 18 mm |

| Winter | 8.61 | 16.9 | 3.0 | 8.90 | 65.2 | 92 | 27 | 50 | 394 | Cumulative: 66 mm |

| Tmean (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Tmin (°C) | ∂Ta24h,max (°C) | N° Days Δ > 1.5 °C | St.dev.T (°C) | RHmean (%) | RHmax (%) | RHmin (%) | ∂UR24h,max (%) | N° Days Δ > 4% | St.dev.RH (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 18.6 | 20.6 | 17.0 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.75 | 52.3 | 68.8 | 23.8 | 20.7 | 22/23 | 9.57 |

| Summer | 28.9 | 30.9 | 27.2 | 2.20 | 3 | 0.74 | 61.8 | 76.5 | 30.6 | 41.10 | 36/36 | 5.02 |

| Winter | 14.5 | 16.0 | 13.4 | 1.50 | 0 | 0.61 | 47.6 | 73.8 | 29.5 | 13.80 | 14/15 | 10.58 |

| Period | Tmean (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Tmin (°C) | ∂Ta24h,max (°C) | N° Days Δ > 1.5 °C | St.dev.T (°C) | RHmean (%) | RHmax (%) | RHmin (%) | ∂UR24h,max (%) | N° Days Δ > 4% | St.dev. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 18.9 | 22.5 | 20.0 | 2.5 | 1/8 | 1.20 | 44.9 | 59.5 | 26.5 | 24.4 | 7/8 | 5.27 |

| Summer | 30.2 | 32.40 | 28.00 | 2.20 | 2/36 | 1.05 | 58.5 | 68.70 | 49.40 | 14.70 | 28/36 | 2.84 |

| Winter | 13.6 | 15.70 | 12.20 | 1.00 | 0/15 | 0.93 | 52.9 | 75.60 | 32.70 | 14.60 | 13/15 | 10.17 |

| Parameter | Range | Accuracy | Resolution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microclimatic station | Air temperature | −20 °C ÷ 60 °C | Typ. ±0.3 °C (−20 °C ÷ 0 °C), ±0.2 °C (0 °C ÷ 60 °C) | 0.1 °C |

| Relative Humidity | 0% ÷ 100% | Typ. ±2%RH (25 °C) | 0.5% | |

| Illuminance | 0–6000 lux, 6-level range | |||

| CO2 concentration | 400 ÷ 5000 ppm | ±(30 ppm + 3% of reading) | ||

| PM2.5, PM10 | 0~1000 μg/m3 | 0 ÷ 100 (±10 μg/m3) | 1 μg/m3 | |

| E-sensor | Illuminance | 0.02 ÷ 2 klux | <8% | |

| UV-A sensor | UV-A radiation | 0 ÷ 20 W/m2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bellazzi, A.; Barozzi, B.; Belussi, L.; Devitofrancesco, A.; Ghellere, M.; Maffè, C.; Salamone, F.; Danza, L. Preliminary Microclimate Monitoring for Preventive Conservation and Visitor Comfort: The Case of the Ligurian Archaeological Museum. Buildings 2026, 16, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030614

Bellazzi A, Barozzi B, Belussi L, Devitofrancesco A, Ghellere M, Maffè C, Salamone F, Danza L. Preliminary Microclimate Monitoring for Preventive Conservation and Visitor Comfort: The Case of the Ligurian Archaeological Museum. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030614

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellazzi, Alice, Benedetta Barozzi, Lorenzo Belussi, Anna Devitofrancesco, Matteo Ghellere, Claudio Maffè, Francesco Salamone, and Ludovico Danza. 2026. "Preliminary Microclimate Monitoring for Preventive Conservation and Visitor Comfort: The Case of the Ligurian Archaeological Museum" Buildings 16, no. 3: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030614

APA StyleBellazzi, A., Barozzi, B., Belussi, L., Devitofrancesco, A., Ghellere, M., Maffè, C., Salamone, F., & Danza, L. (2026). Preliminary Microclimate Monitoring for Preventive Conservation and Visitor Comfort: The Case of the Ligurian Archaeological Museum. Buildings, 16(3), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030614