Exploring the Impact of Different Clustering Algorithms on the Performance of Ensemble Learning-Based Mass Appraisal Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

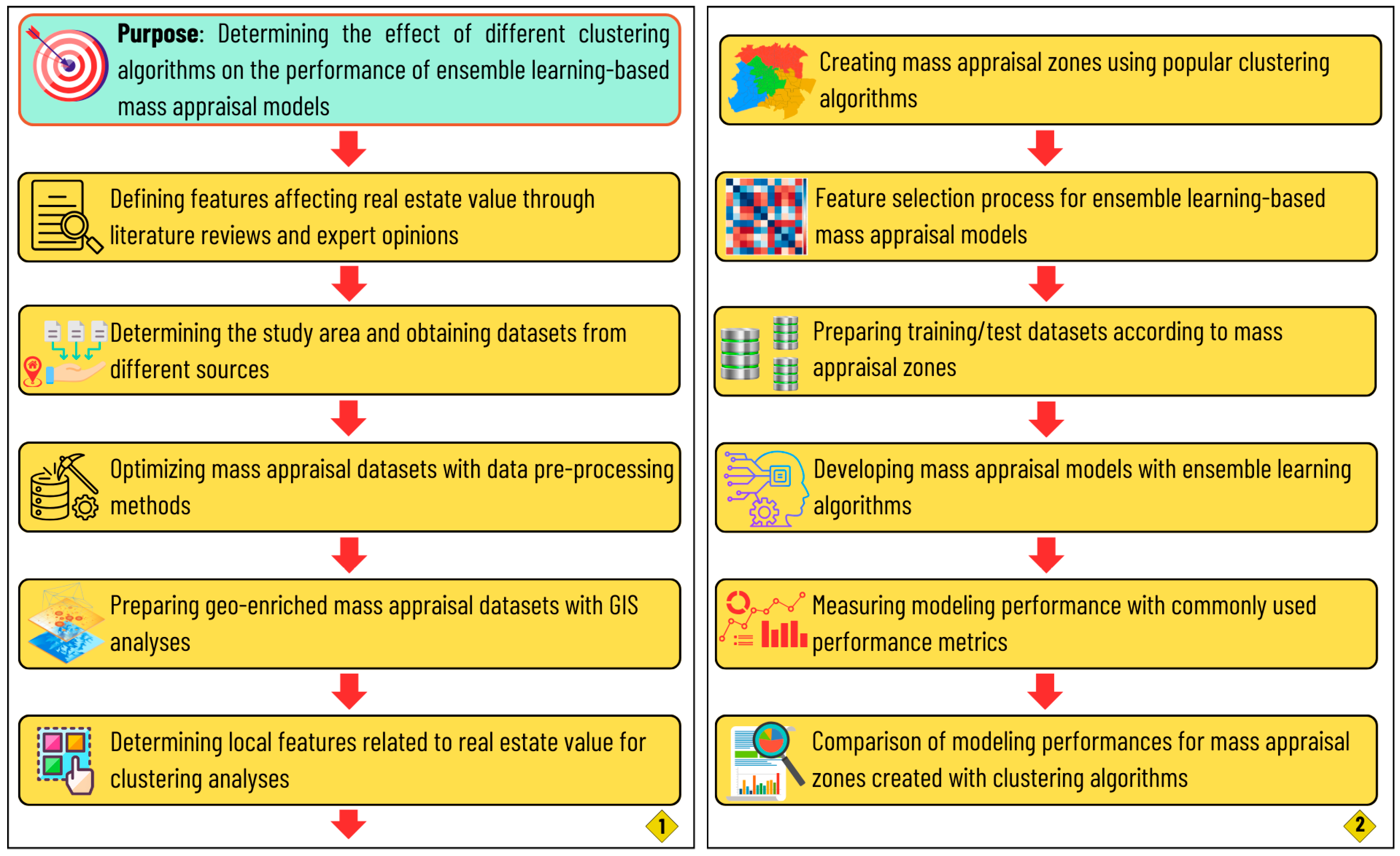

1.2. Aim and Methodology

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Datasets

2.3. Clustering Algorithms

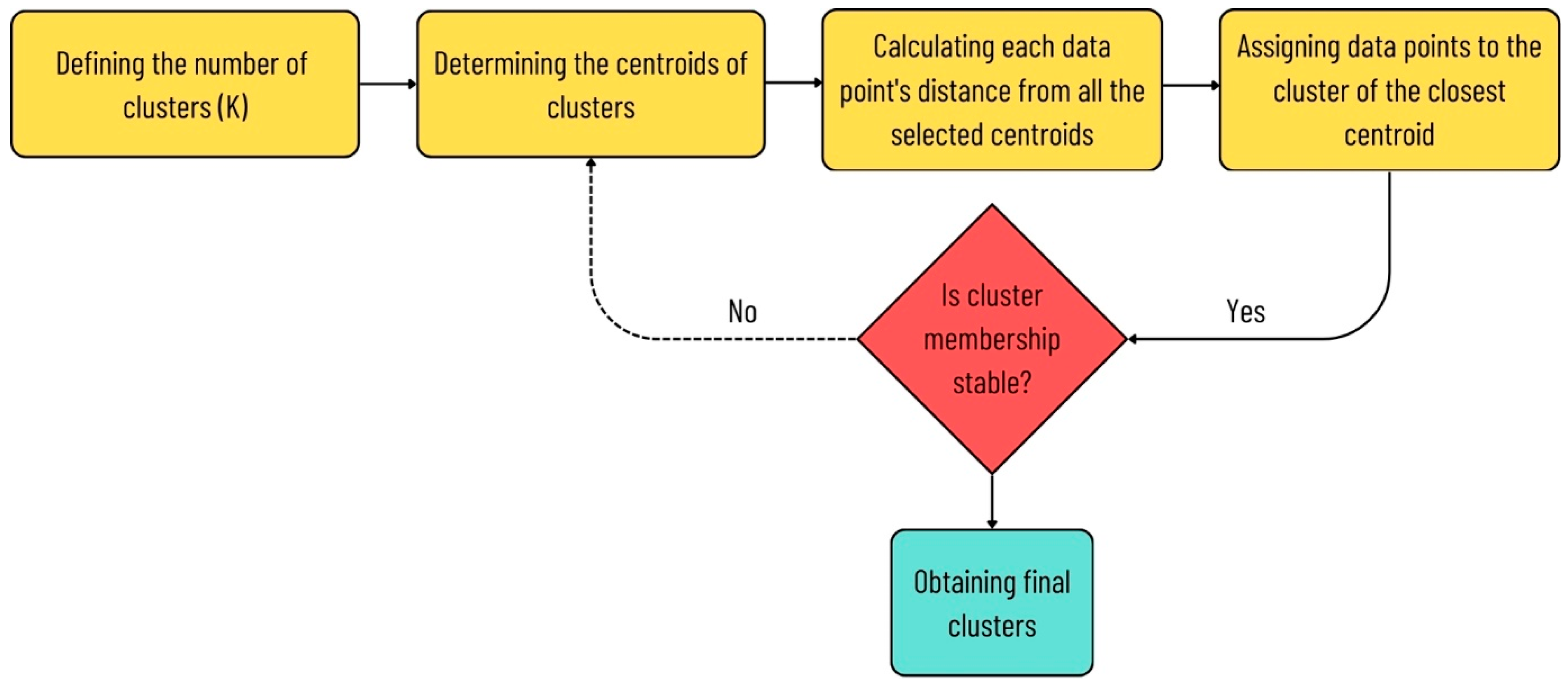

2.3.1. K-Means Algorithm

2.3.2. K-Medians Algorithm

2.3.3. Spatially Constrained Multivariate Clustering Algorithm

2.4. Clustering Validity Indices

| Validity Index | Description | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette Index | It is a validity measure used to evaluate the cohesion and separation of clusters by analyzing how similar each data point is to its own cluster compared with other clusters. It has an index value in the range of [−1,1], and higher index values mean that data points are well matched to their assigned clusters while being distinctly separated from neighboring clusters [39,50] | where : the average distance between and all other data points in its own cluster (within-cluster dissimilarity) : the minimum average distance between and all data points in any other cluster (nearest-cluster dissimilarity) |

| Calinski–Harabasz Index | It is a statistical measure used to evaluate the validity and internal consistency of clustering results. The index simultaneously assesses how distinctly the clusters are separated and how tightly the data points within each cluster are grouped. A high index value indicates strong within-cluster cohesion and clear separation between clusters [51,52] | : the number of data points in cluster : the centroid of cluster : the overall mean of all data points : a data point belonging to cluster : the number of clusters : the total number of data points |

| Davies–Bouldin Index | It is a clustering validity measure that evaluates the quality of a clustering solution by combining two components: the first term penalizes high intra-cluster variance, while the second term rewards large inter-cluster separation. It quantifies how compact clusters are and how distinct they are from each other, with lower index values indicating better clustering performance [53,54] | where : the number of clusters : the average distance between the cluster’s center and all of its elements (within-cluster scatter) : number of data points in cluster : the distance between the centroids of clusters and (between-cluster separation) |

2.5. Ensemble Learning Algorithms

2.5.1. Random Forest (RF)

2.5.2. Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM)

2.5.3. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

2.5.4. Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)

2.6. Performance Metrics

2.7. Overview of the Datasets and Applied Methodological Steps

3. Results

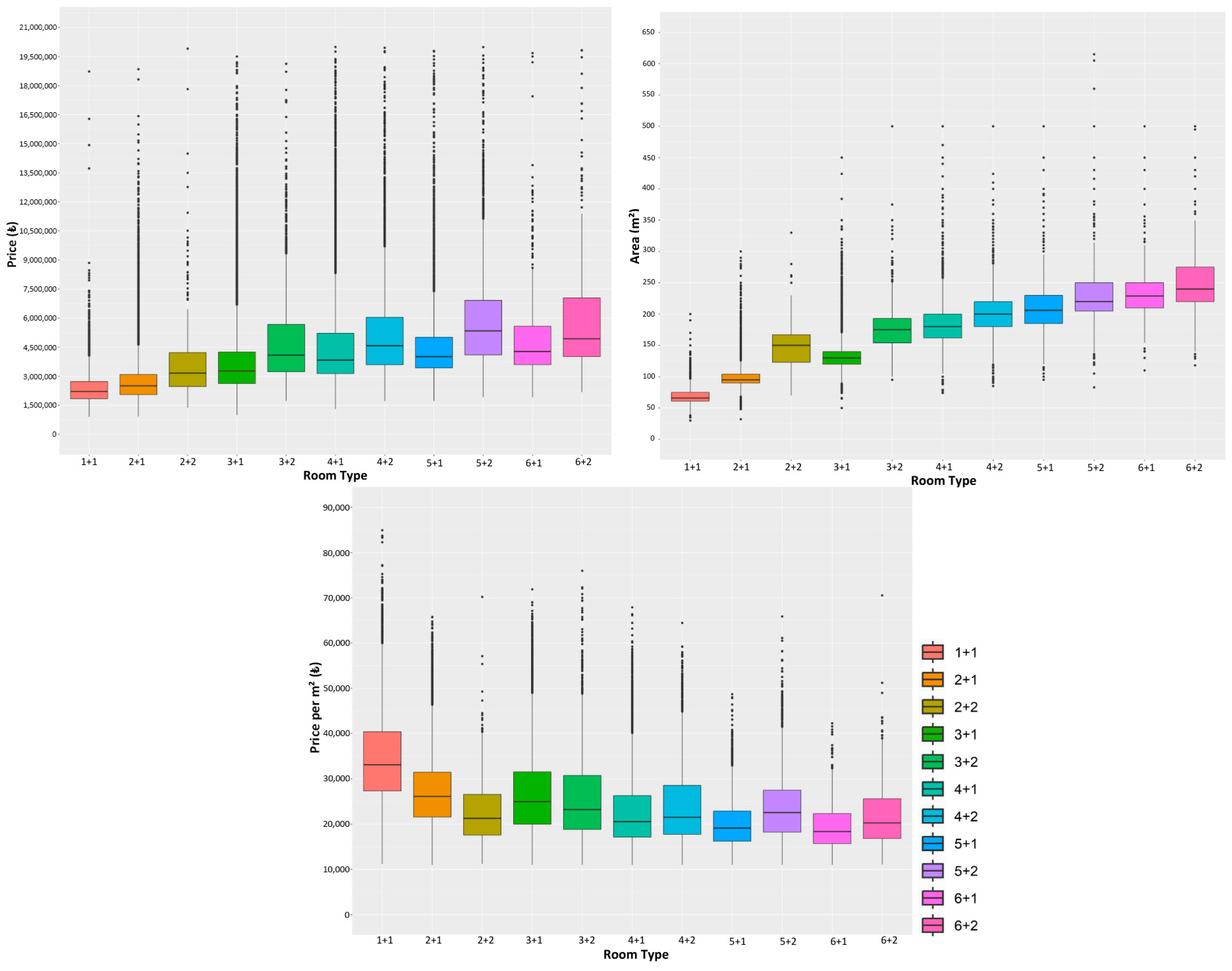

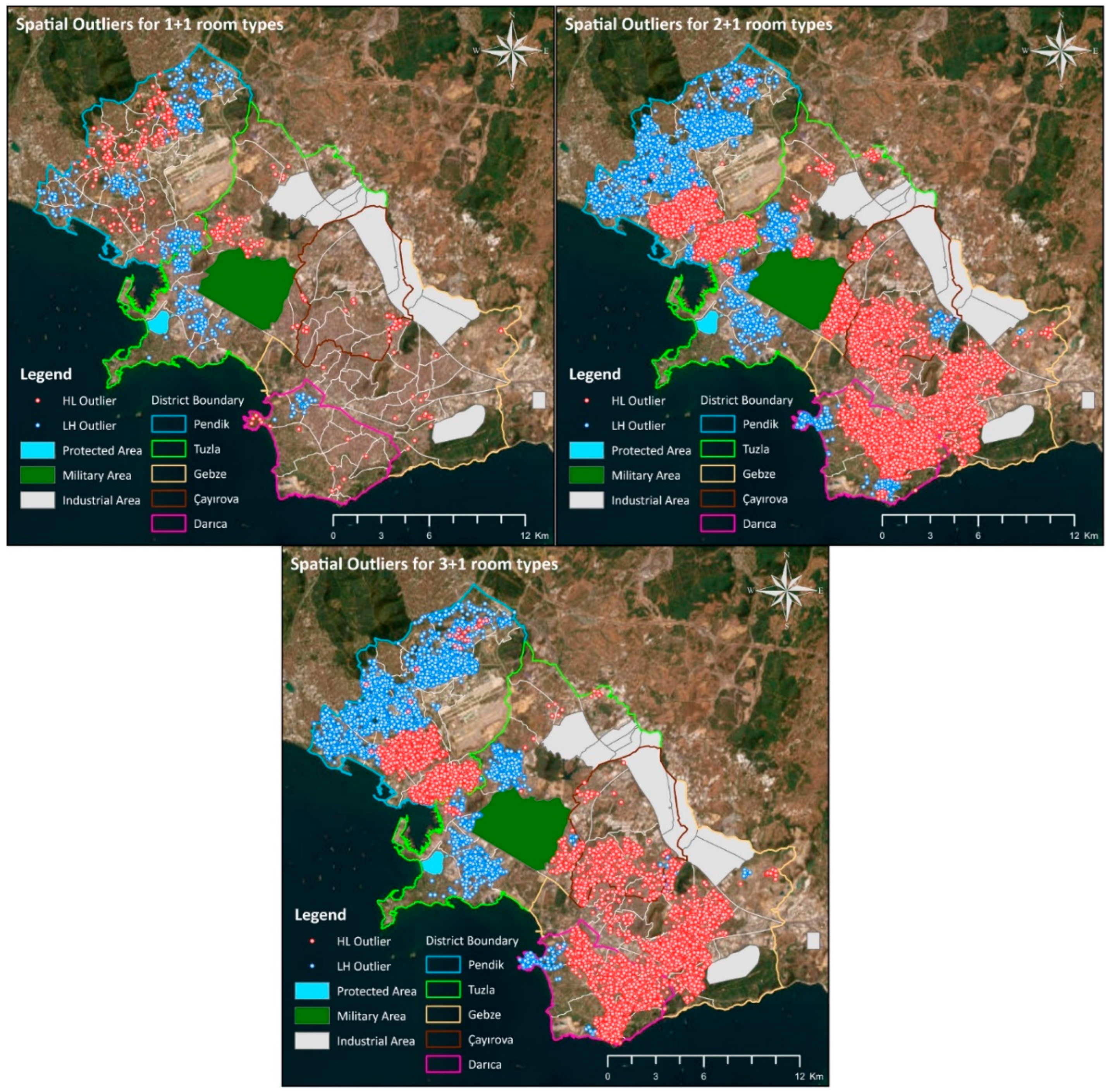

3.1. Data Pre-Processing

3.2. Determining the Features Related to Real Estate Value for Clustering Analysis

3.3. Creating Appraisal Zones with the Clustering Algorithms and Evaluating Clustering Results

3.4. Developing Mass Appraisal Models with the Ensemble Learning Algorithms and Evaluating Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dataset | Variables | Data Level |

|---|---|---|

| Price Dataset | Sales Price (₺), Area (m2), Number of Rooms, Number of Living Rooms, Total Number of Rooms, Number of Bathrooms, Total Number of Floors, Floor Level, Building Age, Direction (North, South, East, West), Room Type, Terrace Area (m2), Inside a Residential Complex, Sports Facility/Gym, Children’s Playground, Elevator, Generator, Security Service, Open Parking Lot, Indoor Parking Garage, Outdoor Swimming Pool, Indoor Swimming Pool, Thermal Insulation, Air Conditioning, Fireplace, Heating System, Landscape (City, Nature, Sea, etc.), Presence of Terrace, Being Duplex, Eligibility for Bank Loan, Furnished Status, etc. | Location (Latitude and Longitude) |

| Local Features Dataset | Population (Neighborhood Population, Neighborhood Population Density (People/km2), Percentage of Children (0–14) (%), Percentage of Youth (15–24) (%), Percentage of Adults (25–65) (%), Percentage of Elderly (65+) (%), Percentage of Females (%), Percentage of Males (%)), Marital Status (Percentage of Married Couples (%), Percentage of Single Individuals (%), Percentage of Divorced Couples (%), Percentage of Widowed Individuals (%)), Income Level (Percentage of A+ Group Individuals (%), Percentage of A Group Individuals (%), Percentage of B Group Individuals (%), Percentage of C Group Individuals (%), Percentage of D Group Individuals (%), Household Income Per Capita, Savings Per Capita), Education Level (Percentage of Individuals with Unknown Education Level (%), Percentage of Illiterate Individuals (%), Percentage of Literate but Uneducated Individuals (%), Percentage of Primary School Graduates (%), Percentage of Secondary School Graduates (%), Percentage of High School Graduates (%), Percentage of Undergraduate/Bachelor’s Graduates (%), Percentage of Master’s Graduates (%), Percentage of PhD Graduates (%)), Household Expenditure Behaviors (Food Expenditures, Healthcare Expenditures, Transportation Expenditures, Education Expenditures, Housing Expenditures, Clothing Expenditures, Restaurant Expenditures, Entertainment Expenditures, Alcohol Expenditures, Furniture Expenditures, Communication Expenditures, Total Expenditure), Socio-Economic Development (Provincial Socio-Economic Development Level, District Socio-Economic Development Level, Socio-Economic Development Ranking of the District within the Province) | Neighborhood/District/Province |

| Urban Functions Datasets | Educational Facilities (Kindergartens, Primary Schools, High Schools, Universities, Public Education Centers), Health Facilities (Local Health Units, Hospitals, Pharmacies, Emergency Health Stations, Clinics, etc.), Shopping and Commercial Facilities (City Centers/Bazaars, Shopping Malls, Markets, Restaurants, Post Offices), Cultural Facilities (Exhibition Centers, Cinemas and Theaters, Museums, Convention and Cultural Centers, Libraries, Historical Buildings), Public Service Facilities (Administrative Facilities, Courthouses, Banks, ATMs, Fire Stations, Security Units), Green Spaces Parks, Forests), Entertainment and Sports Facilities (Beaches, Amusement Parks, Sports Facilities), Accommodation Facilities (Guesthouses, Hotels), Industrial Facilities (Fuel Stations, Industrial Facilities, Water Treatment Plants), Religious Facilities (Places of Worship, Cemeteries), Transportation Facilities (Rail System Stations, Airports, Bus Stops, Taxi Stands, Sea Piers, EV Charging Stations, Bike Stations, Bus Terminals, etc.), Public Law Restriction Areas (Military Area, Natural Protected Area, Specially Protected Environment Areas, Water Basin Areas, etc.) | Location (Latitude and Longitude) |

| Real Estate Market Activity Dataset | Trading Density, Number of Sales, Number of Mortgages, Sales for Condominium Units | Neighborhood |

| Air Quality and Meteorological Dataset | Air Quality Index, Temperature (°C), Wind Speed (m/sn), Pressure (hPa), Humidity (%) | Location (Latitude and Longitude) |

| The Building Energy Statistics Dataset | Number of Building Energy Certificates, Primary Energy Consumption (kWh/year), Air-Conditioned area (m2), Renewable Energy Contribution (kWh/year) | District |

References

- Bovkir, R.; Aydinoglu, A.C. Providing Land Value Information from Geographic Data Infrastructure by Using Fuzzy Logic Analysis Approach. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IVSC. International Valuation Standards; IVSC: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 9780993151347. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Peng, W.; Gao, S.; Rao, J.; Duarte, F.; Ratti, C. Understanding House Price Appreciation Using Multi-Source Big Geo-Data and Machine Learning. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, E. Performing Real Estate Value(s): Real Estate Developers, Systems of Expertise and the Production of Space. Geoforum 2022, 134, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, T.; Moulas, A. A Proposal of a Mass Appraisal System in Greece with CAMA System: Evaluating GWR and MRA Techniques in Thessaloniki Municipality. Open Geosci. 2016, 8, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAAO. Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property—A Criterion for Measuring Fairness, Quality, Equity and Accuracy; IAAO: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, V.J. Mass Appraisal Models of Real Estate in the 21st Century: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepe, E. A Random Forests-Based Hedonic Price Model Accounting for Spatial Autocorrelation. J. Geogr. Syst. 2024, 26, 511–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinoglu, A.C.; Bovkir, R.; Colkesen, I. Implementing a Mass Valuation Application on Interoperable Land Valuation Data Model Designed as an Extension of the National GDI. Surv. Rev. 2021, 53, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafary, P.; Shojaei, D.; Rajabifard, A.; Ngo, T. Automating Property Valuation at the Macro Scale of Suburban Level: A Multi-Step Method Based on Spatial Imputation Techniques, Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Habitat Int. 2024, 148, 103075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafary, P.; Shojaei, D.; Rajabifard, A.; Ngo, T. Automated Land Valuation Models: A Comparative Study of Four Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods Based on a Comprehensive Range of Influential Factors. Cities 2024, 151, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iban, M.C. An Explainable Model for the Mass Appraisal of Residences: The Application of Tree-Based Machine Learning Algorithms and Interpretation of Value Determinants. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, J.P.; Piumetto, M.A.; Lucca, C.M.; Da Silva, E. Mass Appraisal as Affordable Public Policy: Open Data and Machine Learning for Mapping Urban Land Values. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppner, J.; von Ahlefeldt-Dehn, B.; Beracha, E.; Schaefers, W. Boosting the Accuracy of Commercial Real Estate Appraisals: An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2025, 71, 314–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unel, F.B.; Yalpir, S. Sustainable Tax System Design for Use of Mass Real Estate Appraisal in Land Management. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, K.; Rosenfelder, M.; Lutz, B. Automated Real Estate Valuation with Machine Learning Models Using Property Descriptions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellmer, R.; Cichulska, A.; Bełej, M. Spatial Analysis of Housing Prices and Market Activity with the Geographically Weighted Regression. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Bahadori, B.; Charkhan, S. Spatial Analysis of Housing Prices in Tehran City. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2024, 17, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mete, M.O. Developing GeoAI Integrated Mass Valuation Model Based on LADM Valuation Information Great Britain Country Profile. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, e13273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, N.; Colak, H.E.; Ozbilgin, F. Spatial Performance Approach to Machine Learning Algorithms: A GIS-Based Comparison Analysis for Real Estate Valuation. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, e13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinoglu, A.C.; Sisman, S. Comparing Modelling Performance and Evaluating Differences of Feature Importance on Defined Geographical Appraisal Zones for Mass Real Estate Appraisal. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2024, 19, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Pettit, C.J.; Heydari, M.; Aghaei, F. Housing Price Variations Using Spatio-Temporal Data Mining Techniques. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 1199–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wei, Y.D.; Li, H. Analyzing Spatial Heterogeneity of Housing Prices Using Large Datasets. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2020, 13, 223–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGM. District Areas, Directorate General for Mapping (DGM)—National Mapping Agency. Available online: https://www.harita.gov.tr/il-ve-ilce-yuzolcumleri (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- TurkStat. Population and Demography. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=nufus-ve-demografi-109&dil=1 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- GDDA. General Directorate of Development Agencies (GDDA), Socio-Economic Development Index of Districts (SEDI)-2022; GDDA: Ankara, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Endeksa. Value, Sell, Invest in Property—Endeksa. Available online: https://www.endeksa.com/en/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Çaǧdaş, V. An Application Domain Extension to CityGML for Immovable Property Taxation: A Turkish Case Study. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2013, 21, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazer, S.; Kocaman, S. A Mass Appraisal Assessment Study Using Machine Learning Based on Multiple Regression and Random Forest. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EVDS. Residential Property Price Index (RPPI) Statistics-Electronic Data Delivery System (EVDS). Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- GDLRC. Land Query Application, General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre (GDLRC). Available online: https://parselsorgu.tkgm.gov.tr/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- NAQIMN. National Air Quality Monitoring Network (NAQIMN), Ministry of Environment, Urbanisation and Climate Change. Available online: https://www.turkiye.gov.tr/cevre-ve-sehircilik-ulusal-hava-kalite-izleme-agi (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- TSMS. Meteorological Data-Information Presentation and Sales System, Turkish State Meteorological Service (TSMS). Available online: https://www.mgm.gov.tr/eng/forecast-cities.aspx (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- GVS. Directorate General of Vocational Services (GVS). Available online: https://meslekihizmetler.csb.gov.tr/en (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Velumani, P.; Priyadharshini, B.; Mukilan, K.; Shanmugapriya. A Mass Appraisal Assessment Study of Land Values Using Spatial Analysis and Multiple Regression Analysis Model (MRA). Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 2614–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Du, Q.; Geng, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y. An Improved Spatial Error Model for the Mass Appraisal of Commercial Real Estate Based on Spatial Analysis: Shenzhen as a Case Study. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugwu, A.E.; Ikotun, A.M.; Oyelade, O.O.; Abualigah, L.; Agushaka, J.O.; Eke, C.I.; Akinyelu, A.A. A Comprehensive Survey of Clustering Algorithms: State-of-the-Art Machine Learning Applications, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Future Research Prospects. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 110, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, G.; Caruso, G.; Hilal, M.; Thomas, I. A Partition-Free Spatial Clustering That Preserves Topology: Application to Built-up Density. J. Geogr. Syst. 2023, 25, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutaywi, M.; Kachouie, N.N. Silhouette Analysis for Performance Evaluation in Machine Learning with Applications to Clustering. Entropy 2021, 23, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirhan, H.; Baser, F. Hierarchical Fuzzy Regression Functions for Mixed Predictors and an Application to Real Estate Price Prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 11545–11561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Arribas-Bel, D.; Singleton, A. Understanding the Dynamics of Urban Areas of Interest through Volunteered Geographic Information. J. Geogr. Syst. 2019, 21, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Multivariate Observations. In Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statisticsand Probability, Berkley, CA, USA, 18–21 June 1965 and 27 December 1965–7 January 1966; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-Means Clustering Algorithms: A Comprehensive Review, Variants Analysis, and Advances in the Era of Big Data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Song, C.; Shen, S.; Gao, P.; Cheng, C.; Cheng, F.; Wan, C.; Zhu, D. Spatial Pattern of Arable Land-Use Intensity in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Godichon-Baggioni, A.; Surendran, S. A Penalized Criterion for Selecting the Number of Clusters for K-Medians. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2024, 33, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, R.M.; Neves, M.C.; Câmara, G.; Da Costa Freitas, C. Efficient Regionalization Techniques for Socio-Economic Geographical Units Using Minimum Spanning Trees. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2006, 20, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Amaral, P. Endogenous Spatial Regimes. J. Geogr. Syst. 2024, 26, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; He, X. A Multi-Stage Hierarchical Clustering Algorithm Based on Centroid of Tree and Cut Edge Constraint. Inf. Sci. 2021, 557, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertunç, E.; Karkınlı, A.E.; Bozdağ, A. A Clustering-Based Approach to Land Valuation in Land Consolidation Projects. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliñski, T.; Harabasz, J. A Dendrite Method Foe Cluster Analysis. Commun. Stat. 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, F.; Riad, R.; Guillaume, S. PDBI: A Partitioning Davies-Bouldin Index for Clustering Evaluation. Neurocomputing 2023, 528, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. A Cluster Separation Measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1979, PAMI-1, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhang, X. Boosting the Accuracy of Property Valuation with Ensemble Learning and Explainable Artificial Intelligence: The Case of Hong Kong. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2025, 74, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Garcia, R.T.; Cespedes-Lopez, M.F.; Perez-Sanchez, V.R. Housing Price Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms in COVID-19 Times. Land 2022, 11, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagi, O.; Rokach, L. Ensemble Learning: A Survey. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2018, 8, e1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Heydari, M.; Aghaei, F.; Pettit, C.J. Housing Price Prediction Incorporating Spatio-Temporal Dependency into Machine Learning Algorithms. Cities 2022, 131, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X. Mapping the Fine-Scale Spatial Pattern of Housing Rent in the Metropolitan Area by Using Online Rental Listings and Ensemble Learning. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 75, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, G.; Scornet, E. A Random Forest Guided Tour. TEST 2016, 25, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, S.; Eibek, K.U.; Akhter, S.; Ziaul, S.; Towfiqul Islam, A.R.M.; Mallick, J. Modeling Fragmentation Probability of Land-Use and Land-Cover Using the Bagging, Random Forest and Random Subspace in the Teesta River Basin, Bangladesh. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čeh, M.; Kilibarda, M.; Lisec, A.; Bajat, B. Estimating the Performance of Random Forest versus Multiple Regression for Predicting Prices of the Apartments. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2699986 (accessed on 17 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Antolí-Martínez, J.M.; Cortijo, A.; Martines, V.; Andrés, S.M.; Sánchez-López, E.; Sirignano, F.M.; Padrón, A.L.; Kim, C.; Park, T. Predicting Determinants of Lifelong Learning Intention Using Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) with Grid Search. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, A.V.; Utkin, L.V. Interpretable Machine Learning with an Ensemble of Gradient Boosting Machines. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2021, 222, 106993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzani, S.; Granderson, J.; Fernandes, S. Gradient Boosting Machine for Modeling the Energy Consumption of Commercial Buildings. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, R.; Costache, R.; Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H.; Pham, Q.B. Flash-Flood Susceptibility Mapping Based on XGBoost, Random Forest and Boosted Regression Trees. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 5479–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Qiu, L.; Lu, C.; Song, L.; Ding, Z.; Yu, Y.; Chen, G. A Data-Driven Model for Predicting Initial Productivity of Offshore Directional Well Based on the Physical Constrained EXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) Trees. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 211, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, B.; Bayrak, O.C.; Gülgen, F.; Gurturk, M.; Abay, P. Unveiling the Impact of Machine Learning Algorithms on the Quality of Online Geocoding Services: A Case Study Using COVID-19 Data. J. Geogr. Syst. 2024, 26, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Corporation. Welcome to LightGBM’s Documentation!—LightGBM 4.6.0 Documentation. Available online: https://lightgbm.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Soomro, A.; Akmar Mokhtar, A.; B Hussin, H.; Lashari, N.; Lekan Oladosu, T.; Muslim Jameel, S.; Inayat, M. Analysis of Machine Learning Models and Data Sources to Forecast Burst Pressure of Petroleum Corroded Pipelines: A Comprehensive Review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 155, 107747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Feng, L.; Yang, L.; Guo, Y. Stock Price Prediction Based on LSTM and LightGBM Hybrid Model. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 11768–11793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, J.; Nayyar, A.; Dalal, S.; Ali, Z.H. House Price Prediction Using Hedonic Pricing Model and Machine Learning Techniques. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2022, 34, e7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibindi, R.; Mwangi, R.W.; Waititu, A.G. A Boosting Ensemble Learning Based Hybrid Light Gradient Boosting Machine and Extreme Gradient Boosting Model for Predicting House Prices. Eng. Rep. 2023, 5, e12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.K.O.; Tang, B.S.; Wong, S.W. Predicting Property Prices with Machine Learning Algorithms. J. Prop. Res. 2021, 38, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, W.S. A House Price Valuation Based on the Random Forest Approach: The Mass Appraisal of Residential Property in South Korea. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2020, 24, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalpır, Ş. Enhancement of Parcel Valuation with Adaptive Artificial Neural Network Modeling. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2018, 49, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Yang, W. A Divide-and-Conquer Method for Predicting the Fine-Grained Spatial Distribution of Population in Urban and Rural Areas. J. Geogr. Syst. 2025, 27, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghushairy, O.; Alsini, R.; Soule, T.; Ma, X. A Review of Local Outlier Factor Algorithms for Outlier Detection in Big Data Streams. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rehman, A.; Belhaouari, S.B. Unsupervised Outlier Detection in Multidimensional Data. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI. Cluster and Outlier Analysis (Anselin Local Moran’s I) (Spatial Statistics)—ArcGIS Pro|Documentation. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/cluster-and-outlier-analysis-anselin-local-moran-s.htm (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Anselin, L.; Sridharan, S.; Gholston, S. Using Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis to Leverage Social Indicator Databases: The Discovery of Interesting Patterns. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 82, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisman, S.; Aydinoglu, A.C. Improving Performance of Mass Real Estate Valuation through Application of the Dataset Optimization and Spatially Constrained Multivariate Clustering Analysis. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Data Pre-Processing | Clustering | Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Price Dataset, The Local Features Dataset, Urban Functions Datasets, Real Estate Market Activity Dataset, Air Quality and Meteorological Datasets, The Building Energy Statistics Dataset | GIS-Based Dataset Preparing Methods (XY Table To Point, Analysis, Euclidean Distance Analysis, Spatial Interpolation Analysis, Extract Multi Values to Points Analysis) | Clustering Algorithms (K-Means, K-Medians, SCMCA) | Ensemble Learning Algorithms (RF, GBM, XGBoost, LightGBM) |

| Outlier Detection Methods (Boxplot, COA) | Clustering Validity Indices (Silhouette Index, Calinski–Harabasz Index, Davies–Bouldin Index) | Hyperparameter Tuning (Grid Search) | |

| Feature Selection Method (Pearson Correlation Analysis) | Performance Metrics (MAE, MAPE, RMSE, R2) | ||

| Feature Standardization Method (Max Normalization) |

| Category | Feature | Correlation Coefficient | Sign (Two-Tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Total population | 0.079 | 0.458 |

| Women residing in the neighborhood (%) | 0.311 ** | 0.003 | |

| Man residing in the neighborhood (%) | −0.311 ** | 0.003 | |

| Population density (person/km2) | −0.097 | 0.362 | |

| Children population in the neighborhood (%) | −0.468 ** | 0.000 | |

| Young population in the neighborhood (%) | −0.231 * | 0.028 | |

| Adult population in the neighborhood (%) | 0.432 ** | 0.000 | |

| Old population in the neighborhood (%) | 0.406 ** | 0.000 | |

| Marital Status | Single person residing in the neighborhood (%) | 0.023 | 0.830 |

| Married couple residing in the neighborhood (%) | −0.365 | 0.000 | |

| Divorced couple residing in the neighborhood (%) | 0.284 ** | 0.007 | |

| Widows residing in the neighborhood (%) | 0.617 ** | 0.000 | |

| Income Level | Population with A+ income level (%) | 0.300 ** | 0.004 |

| Population with A income level (%) | 0.298 ** | 0.004 | |

| Population with B income level (%) | −0.026 | 0.809 | |

| Population with C income level (%) | −0.277 ** | 0.008 | |

| Population with D income level (%) | −0.298 ** | 0.004 | |

| Education Level | Population with unknown educational status (%) | 0.344 ** | 0.001 |

| Illiterate population (%) | −0.362 ** | 0.000 | |

| Literate population without a diploma (%) | −0.514 ** | 0.000 | |

| Primary school graduate population (%) | −0.555 ** | 0.000 | |

| Primary education graduate population (%) | −0.653 ** | 0.000 | |

| Secondary school graduate population (%) | −0.731 ** | 0.000 | |

| High school graduate population (%) | 0.199 | 0.060 | |

| Population with undergraduate degree (%) | 0.740 ** | 0.000 | |

| Population with MSc degree (%) | 0.703 ** | 0.000 | |

| Population with PhD degree (%) | 0.666 ** | 0.000 | |

| Household Expenditure Behavior | Individual household income per capita (₺) | 0.326 ** | 0.002 |

| Savings per capita (₺) | 0.336 ** | 0.001 | |

| Total household consumption expenditure per capita (₺) | 0.322 ** | 0.002 | |

| Food and non-alcoholic beverages expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.263 * | 0.012 | |

| Alcoholic beverages, cigarette and tobacco expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.279 ** | 0.008 | |

| Clothing and footwear expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.331 ** | 0.001 | |

| Housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuel expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.271 ** | 0.010 | |

| Furniture, houses appliances and home care services expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.331 ** | 0.001 | |

| Health expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.329 ** | 0.002 | |

| Transportation expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.335 ** | 0.001 | |

| Communication expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.319 ** | 0.002 | |

| Entertainment and culture expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.336 ** | 0.001 | |

| Educational services expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.330 ** | 0.002 | |

| Restaurant, food services and hotel expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.330 ** | 0.001 | |

| Various good and services expenditures per capita (₺) | 0.336 ** | 0.001 | |

| Socio-Economic Development | Socio-economic development score of the district | 0.473 ** | 0.000 |

| General development ranking of the district by country | −0.370 ** | 0.000 | |

| Development ranking of the district within the city | 0.642 ** | 0.000 | |

| District development level | −0.359 ** | 0.001 | |

| Sales Statistics | Real estate trading density | 0.047 | 0.657 |

| Number of main real estate mortgage sales | −0.090 | 0.401 | |

| Number of main real estate sales | −0.241 * | 0.022 | |

| Number of condominium mortgage sales | 0.119 | 0.263 | |

| Number of condominium unit sales | 0.130 | 0.223 | |

| Local Inventory | Number of education facilities | 0.313 ** | 0.003 |

| Number of religious facilities | 0.053 | 0.622 | |

| Number of cultural facilities | 0.306 ** | 0.003 | |

| Number of healthcare facilities | 0.378 ** | 0.000 | |

| Number of industrial facilities | 0.046 | 0.668 | |

| Number of private workplace facilities | 0.231 * | 0.029 | |

| Number of shopping facilities | 0.189 | 0.074 | |

| Number of accommodation facilities | 0.483 ** | 0.000 | |

| Number of sport facilities | 0.422 ** | 0.000 | |

| Number of transportation facilities | 0.543 ** | 0.000 | |

| Number of entertainment facilities | 0.025 | 0.813 | |

| Number of public service facilities | 0.296 ** | 0.005 | |

| Number of personal care facilities | 0.382 ** | 0.000 | |

| Number of households | 0.151 | 0.156 | |

| Number of buildings | 0.175 | 0.098 | |

| Land Value | Average land market value (₺) | 0.666 ** | 0.666 ** |

| Clustering Algorithm | Silhouette Index | Calinski–Harabasz Index | Davies–Bouldin Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | 0.549 | 432.320 | 0.574 |

| K-Medians | 0.464 | 262.481 | 0.648 |

| SCMCA | 0.032 | 46.641 | 2.702 |

| Clustering Algorithm | Training/Test Data Ratio | Cluster-1 | Cluster-2 | Cluster-3 | Cluster-4 | Cluster-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | Training (70%) | 31.913 | 25.857 | 23.361 | 1.971 | 45.698 |

| Test (30%) | 13.678 | 11.082 | 10.013 | 846 | 19.585 | |

| K-Medians | Training (70%) | 36.743 | 20.193 | 25.332 | 13.736 | 32.797 |

| Test (30%) | 15.748 | 8.654 | 10.857 | 5.888 | 14.056 | |

| SCMCA | Training (70%) | 41.477 | 9.485 | 20.767 | 15.171 | 41.902 |

| Test (30%) | 17.776 | 4.065 | 8.900 | 6.503 | 17.958 |

| Model | Parameter | Range | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | mtry | 30, 40, 50 | 40 |

| ntree | 50, 100, 150 | 150 | |

| GBM | n.trees | 50, 100, 150 | 150 |

| interaction.depth | 4, 5, 6 | 6 | |

| shrinkage | 0.01, 0.05, 0.10 | 0.05 | |

| bag.fraction | 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 | 0.8 | |

| n.minobsinnode | 10, 15, 20 | 15 | |

| XGBoost | eta | 0.01, 0.05, 0.10 | 0.10 |

| max_depth | 4, 5, 6 | 6 | |

| min_child_weight | 10, 15, 20 | 15 | |

| Subsample | 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| colsample_bytree | 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| gamma | 0, 1, 5 | 1 | |

| alpha (L1) | 0, 1, 5 | 0 | |

| lambda (L2) | 1, 5, 10 | 1 | |

| Nrounds | 50, 100, 150 | 150 | |

| LightGBM | learning_rate | 0.01, 0.05, 0.10 | 0.05 |

| num_leaves | 40, 50, 60 | 60 | |

| max_depth | 4, 5, 6 | 6 | |

| min_child_samples | 10, 15, 20 | 20 | |

| subsample | 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| colsample_bytree | 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| reg_alpha (L1) | 0, 0.1, 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| reg_lambda (L2) | 0, 0.1, 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| Nrounds | 50, 100, 150 | 150 |

| Model | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.063 | 15.679 | 0.083 | 0.654 |

| GBM | 0.055 | 13.270 | 0.072 | 0.737 |

| XGBoost | 0.046 | 11.071 | 0.061 | 0.814 |

| LightGBM | 0.045 | 10.770 | 0.059 | 0.823 |

| Clustering Algorithm | Cluster | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | Cluster-1 | 0.066 | 13.519 | 0.086 | 0.404 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.059 | 16.160 | 0.078 | 0.565 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.072 | 13.287 | 0.090 | 0.531 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.069 | 11.830 | 0.086 | 0.402 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.045 | 13.910 | 0.060 | 0.404 | |

| K-Medians | Cluster-1 | 0.064 | 14.303 | 0.083 | 0.504 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.057 | 15.434 | 0.076 | 0.515 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.072 | 13.124 | 0.090 | 0.518 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.054 | 13.110 | 0.069 | 0.389 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.047 | 13.889 | 0.063 | 0.428 | |

| SCMCA | Cluster-1 | 0.069 | 14.212 | 0.088 | 0.539 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.060 | 13.942 | 0.080 | 0.633 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.068 | 14.190 | 0.086 | 0.638 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.054 | 13.183 | 0.069 | 0.480 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.053 | 14.688 | 0.070 | 0.472 |

| Clustering Algorithm | Cluster | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | Cluster-1 | 0.059 | 11.933 | 0.078 | 0.515 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.051 | 13.805 | 0.067 | 0.673 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.064 | 11.672 | 0.081 | 0.620 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.064 | 10.858 | 0.080 | 0.479 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.040 | 12.047 | 0.053 | 0.545 | |

| K-Medians | Cluster-1 | 0.057 | 12.475 | 0.075 | 0.603 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.051 | 13.509 | 0.067 | 0.614 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.065 | 11.622 | 0.081 | 0.605 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.049 | 11.654 | 0.063 | 0.495 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.042 | 12.120 | 0.056 | 0.555 | |

| SCMCA | Cluster-1 | 0.061 | 12.369 | 0.078 | 0.638 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.054 | 12.451 | 0.072 | 0.696 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.060 | 12.284 | 0.077 | 0.715 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.047 | 11.533 | 0.062 | 0.590 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.046 | 12.593 | 0.061 | 0.597 |

| Clustering Algorithm | Cluster | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | Cluster-1 | 0.050 | 9.778 | 0.067 | 0.634 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.044 | 12.020 | 0.060 | 0.744 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.056 | 10.016 | 0.072 | 0.698 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.063 | 10.668 | 0.079 | 0.491 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.037 | 11.119 | 0.048 | 0.620 | |

| K-Medians | Cluster-1 | 0.049 | 10.474 | 0.065 | 0.697 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.045 | 11.807 | 0.060 | 0.694 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.056 | 10.019 | 0.073 | 0.683 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.047 | 11.153 | 0.061 | 0.530 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.038 | 11.116 | 0.051 | 0.631 | |

| SCMCA | Cluster-1 | 0.050 | 9.902 | 0.066 | 0.744 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.049 | 11.157 | 0.066 | 0.744 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.054 | 10.969 | 0.070 | 0.762 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.045 | 10.887 | 0.059 | 0.630 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.042 | 11.487 | 0.056 | 0.667 |

| Clustering Algorithm | Cluster | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | Cluster-1 | 0.048 | 9.461 | 0.066 | 0.652 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.043 | 11.563 | 0.058 | 0.756 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.054 | 9.670 | 0.070 | 0.711 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.062 | 10.602 | 0.079 | 0.495 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.036 | 10.869 | 0.047 | 0.636 | |

| K-Medians | Cluster-1 | 0.046 | 9.950 | 0.063 | 0.717 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.043 | 11.364 | 0.058 | 0.712 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.055 | 9.745 | 0.072 | 0.695 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.046 | 10.970 | 0.060 | 0.541 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.037 | 10.820 | 0.050 | 0.646 | |

| SCMCA | Cluster-1 | 0.048 | 9.433 | 0.064 | 0.760 |

| Cluster-2 | 0.048 | 10.937 | 0.065 | 0.754 | |

| Cluster-3 | 0.053 | 10.615 | 0.069 | 0.771 | |

| Cluster-4 | 0.044 | 10.735 | 0.058 | 0.637 | |

| Cluster-5 | 0.041 | 11.163 | 0.055 | 0.682 |

| Clustering Algorithm | Model | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | RF | 0.058 | 14.120 | 0.076 | 0.459 |

| GBM | 0.052 | 12.285 | 0.067 | 0.576 | |

| XGBoost | 0.045 | 10.761 | 0.060 | 0.661 | |

| LightGBM | 0.044 | 10.438 | 0.059 | 0.675 | |

| K-Medians | RF | 0.059 | 14.016 | 0.077 | 0.477 |

| GBM | 0.053 | 12.291 | 0.069 | 0.581 | |

| XGBoost | 0.047 | 10.830 | 0.062 | 0.659 | |

| LightGBM | 0.045 | 10.461 | 0.060 | 0.675 | |

| SCMCA | RF | 0.061 | 14.222 | 0.079 | 0.533 |

| GBM | 0.054 | 12.336 | 0.070 | 0.636 | |

| XGBoost | 0.047 | 10.798 | 0.062 | 0.709 | |

| LightGBM | 0.046 | 10.450 | 0.061 | 0.722 |

| Clustering Algorithm | Model | MAE (%ΔPM) | MAPE (%ΔPM) | RMSE (%ΔPM) | R2 (%ΔPM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means | RF | −7.26 | −9.95 | −8.40 | −29.81 |

| GBM | −5.48 | −7.42 | −6.90 | −21.83 | |

| XGBoost | −0.84 | −2.80 | −1.15 | −18.90 | |

| LightGBM | −1.07 | −3.09 | −1.14 | −17.90 | |

| K-Medians | RF | −5.73 | −10.61 | −7.26 | −27.13 |

| GBM | −3.30 | −7.38 | −4.83 | −21.11 | |

| XGBoost | 2.22 | −2.18 | 1.74 | −19.06 | |

| LightGBM | 1.57 | −2.87 | 1.55 | −17.96 | |

| SCMCA | RF | −3.05 | −9.29 | −4.16 | −18.55 |

| GBM | −1.69 | −7.04 | −2.88 | −13.71 | |

| XGBoost | 3.20 | −2.46 | 2.95 | −12.99 | |

| LightGBM | 2.74 | −2.97 | 2.84 | −12.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sisman, S.; Kara, A.; Aydinoglu, A.C. Exploring the Impact of Different Clustering Algorithms on the Performance of Ensemble Learning-Based Mass Appraisal Models. Buildings 2026, 16, 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030615

Sisman S, Kara A, Aydinoglu AC. Exploring the Impact of Different Clustering Algorithms on the Performance of Ensemble Learning-Based Mass Appraisal Models. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):615. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030615

Chicago/Turabian StyleSisman, Suleyman, Abdullah Kara, and Arif Cagdas Aydinoglu. 2026. "Exploring the Impact of Different Clustering Algorithms on the Performance of Ensemble Learning-Based Mass Appraisal Models" Buildings 16, no. 3: 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030615

APA StyleSisman, S., Kara, A., & Aydinoglu, A. C. (2026). Exploring the Impact of Different Clustering Algorithms on the Performance of Ensemble Learning-Based Mass Appraisal Models. Buildings, 16(3), 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030615