Structural Response and Damage of RPC Bridge Piers Under Heavy Vehicle Impact: A High-Fidelity FE Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Validation and Result Analysis

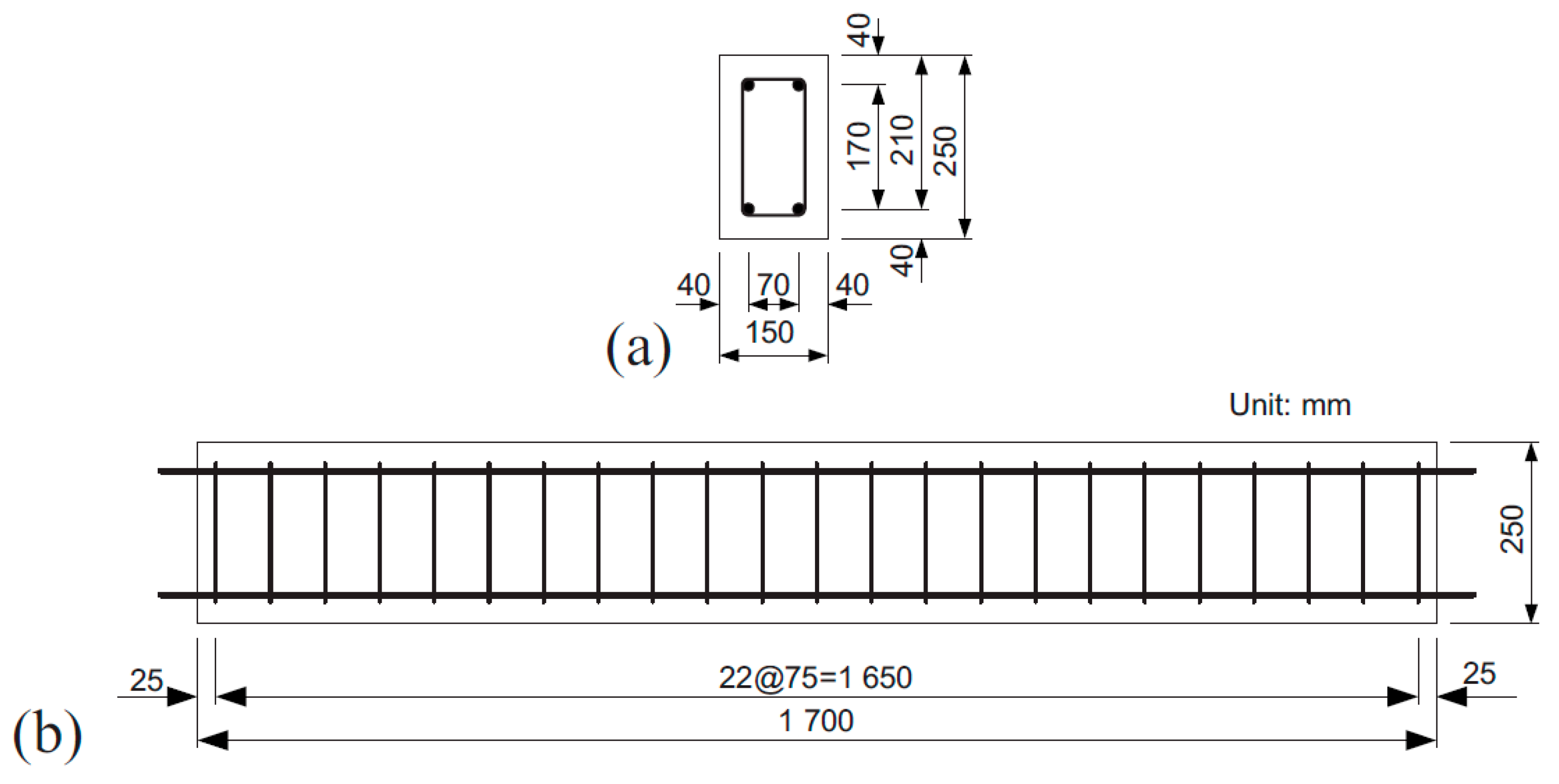

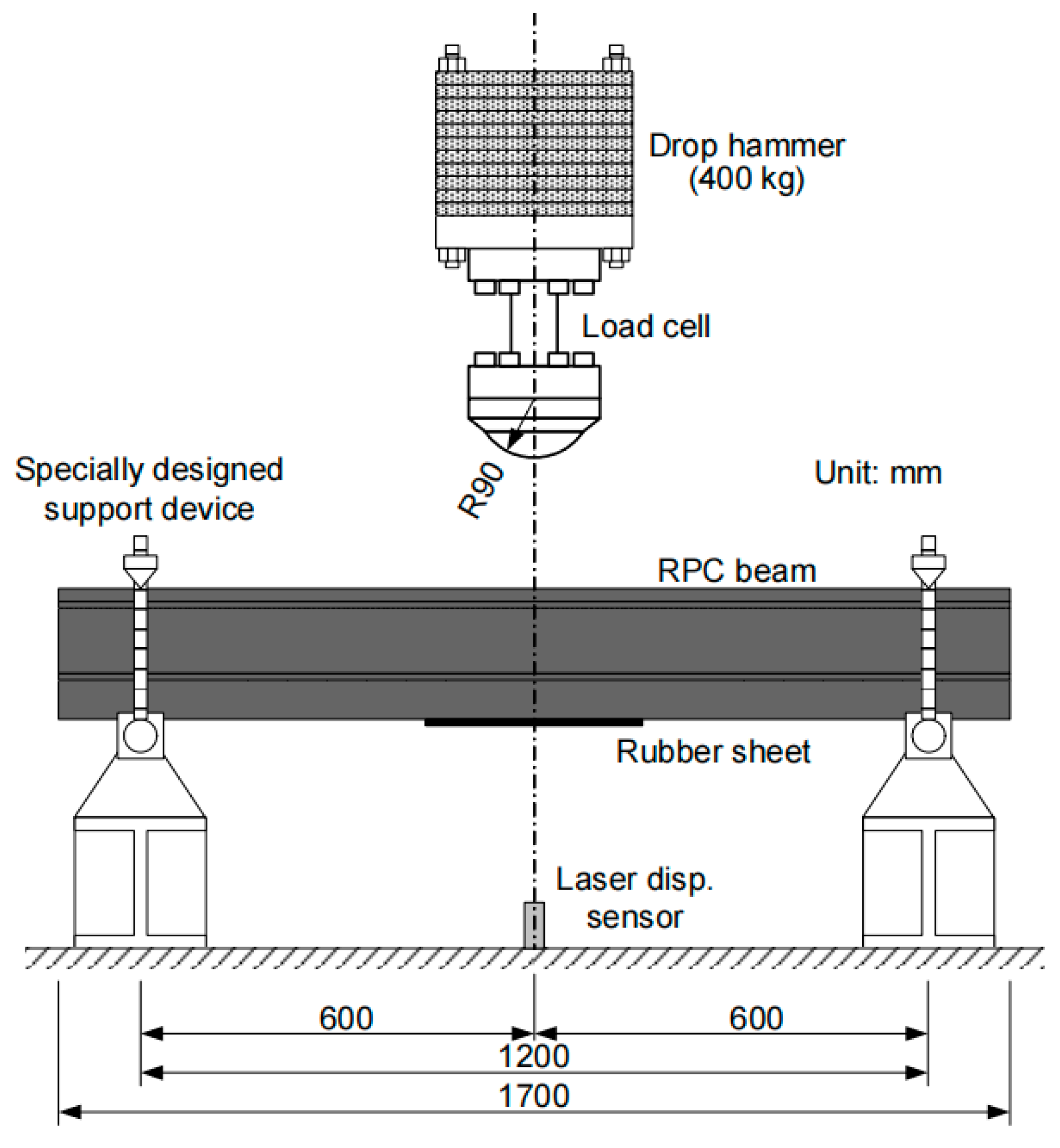

2.1. Drop Hammer Impact Test and Finite Element Model of RPC Beam

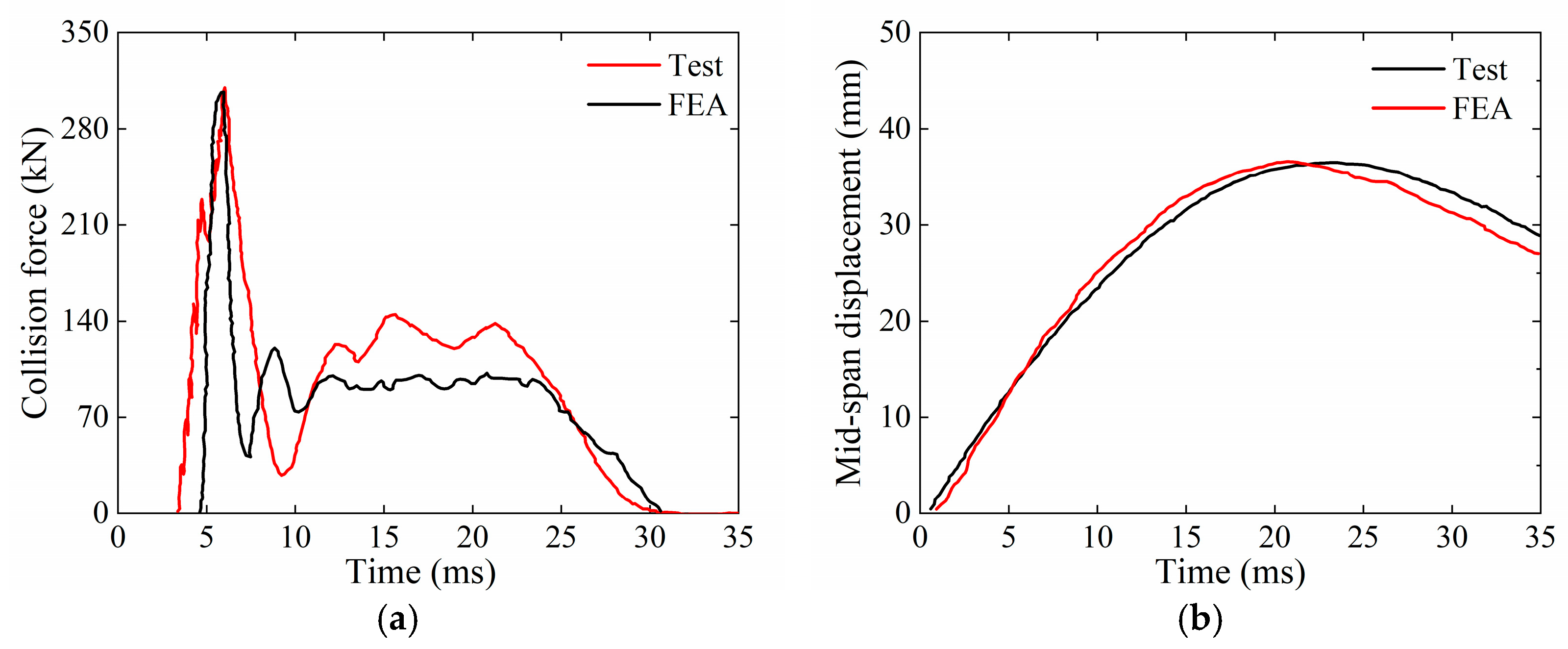

2.2. Comparison and Analysis of Results

3. Collision Behavior of RPC Bridge Piers

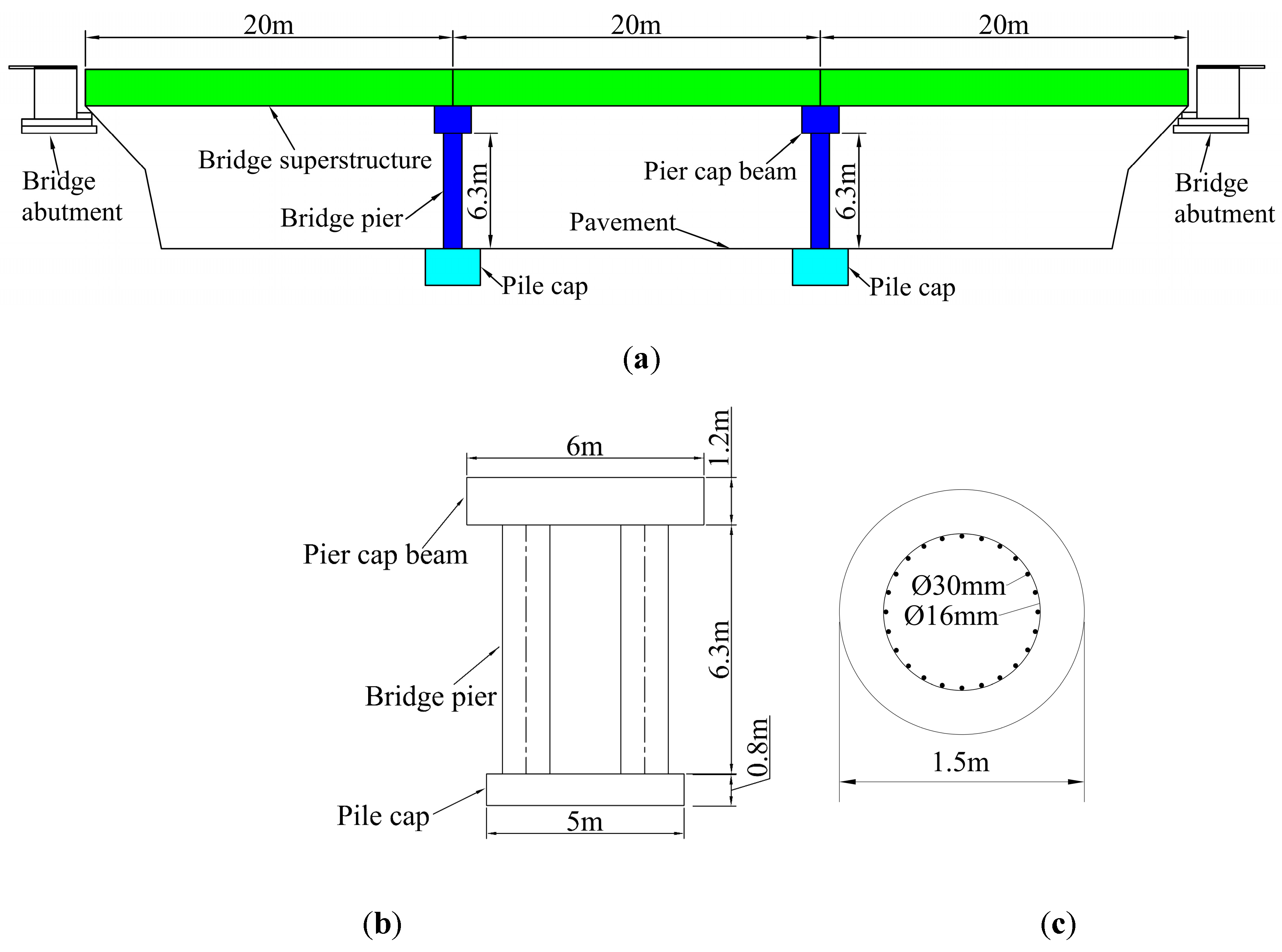

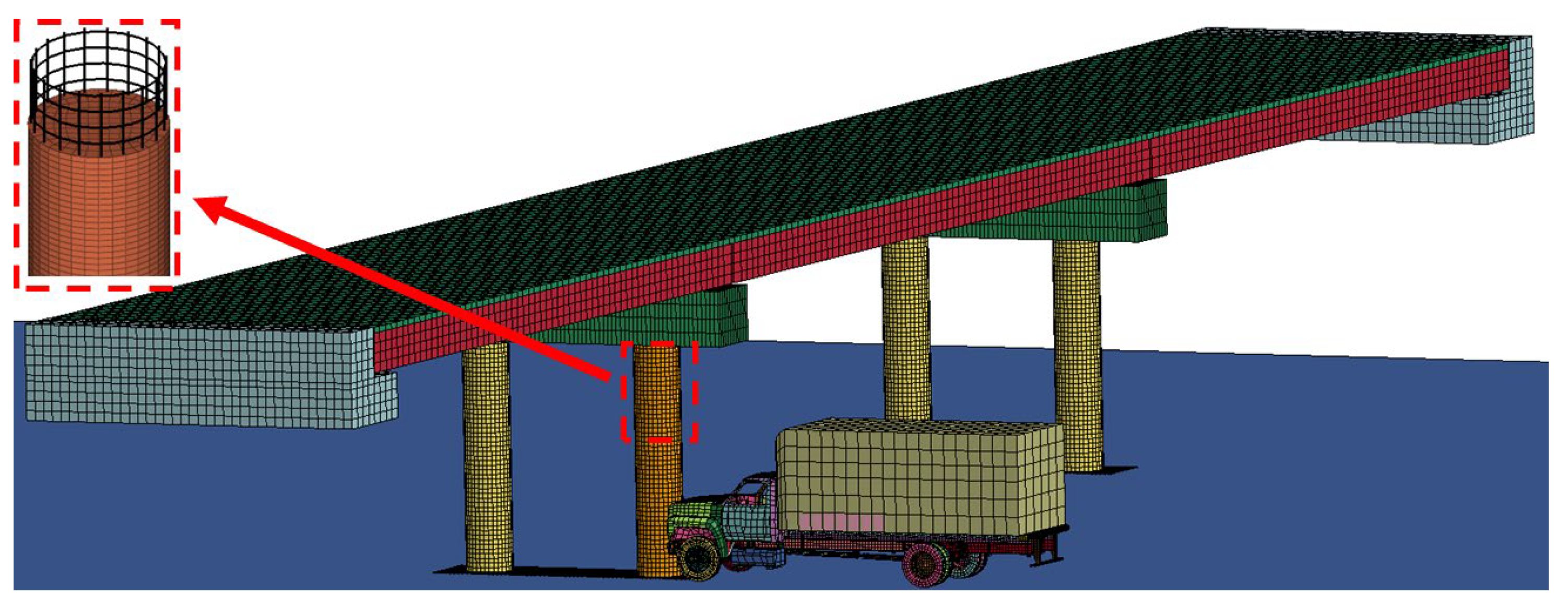

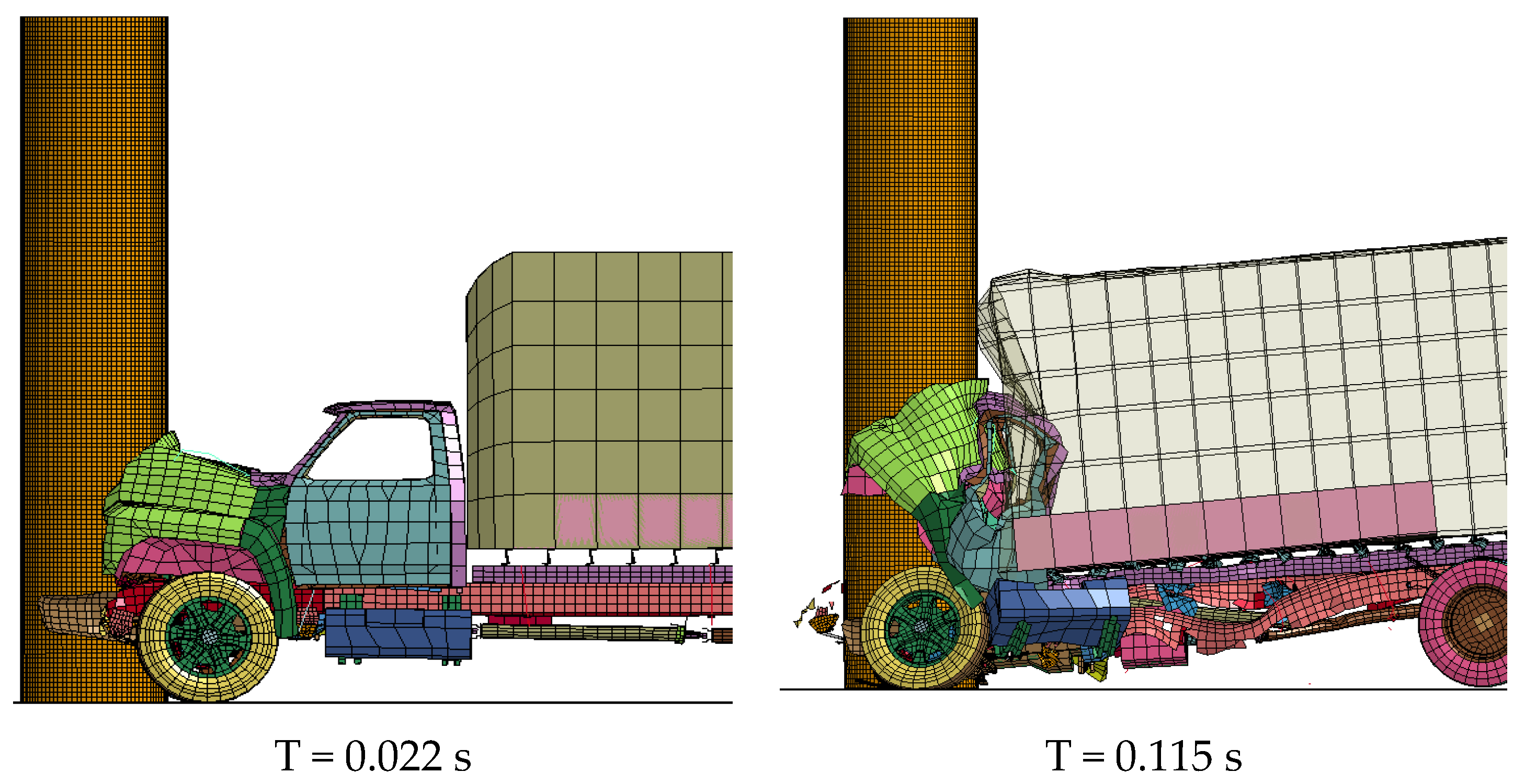

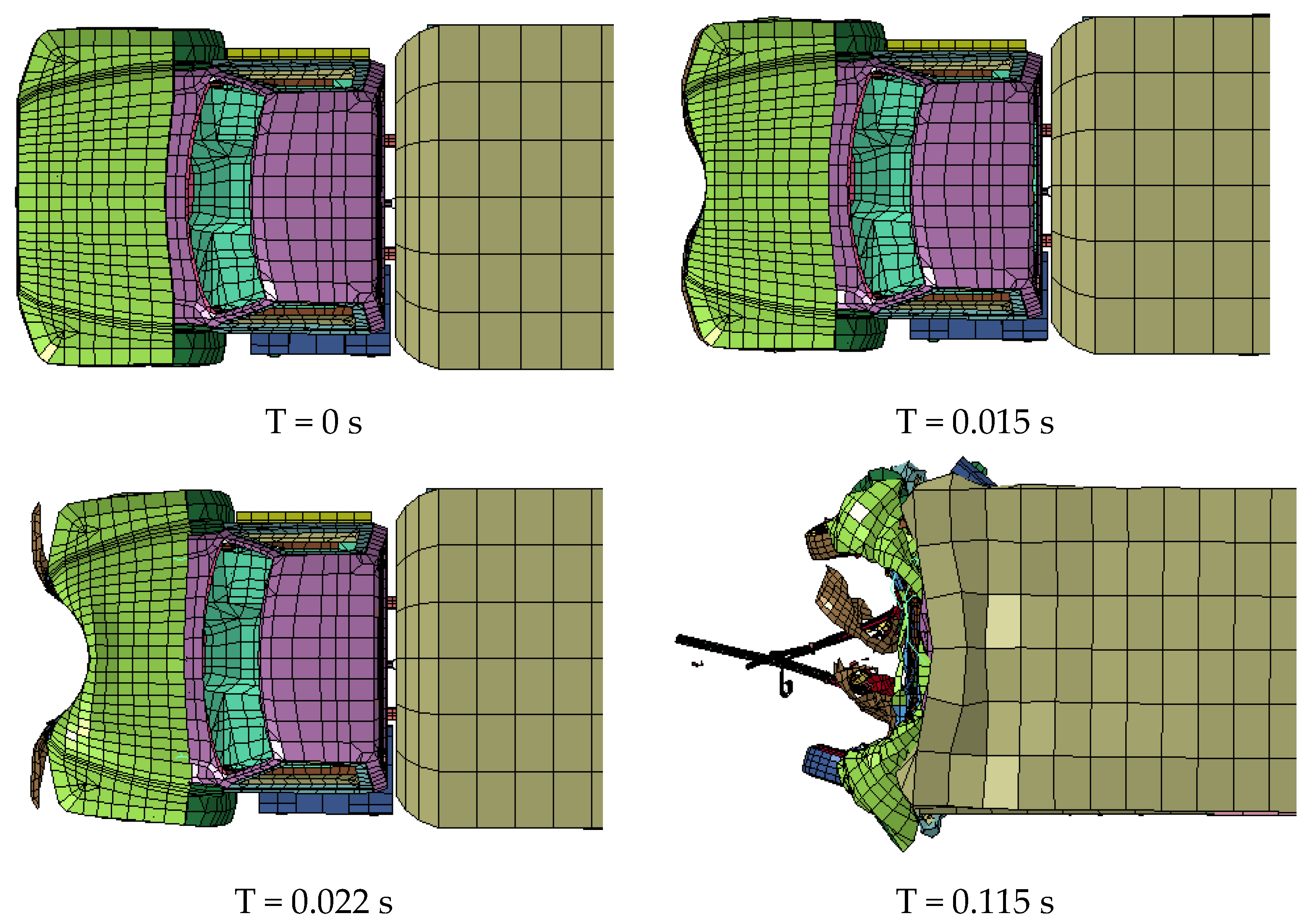

3.1. Finite Element Model Establishment for Vehicle–Bridge Collision

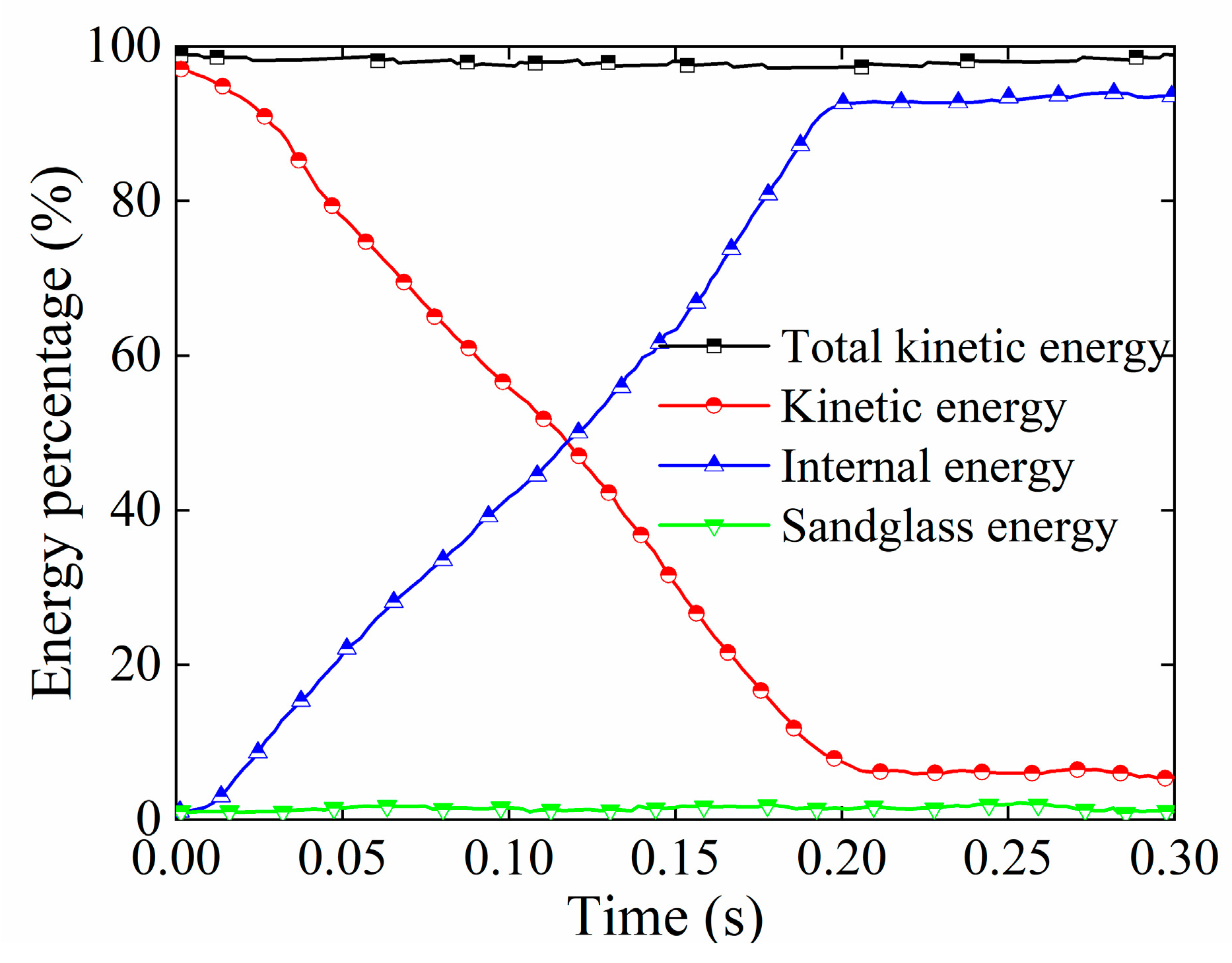

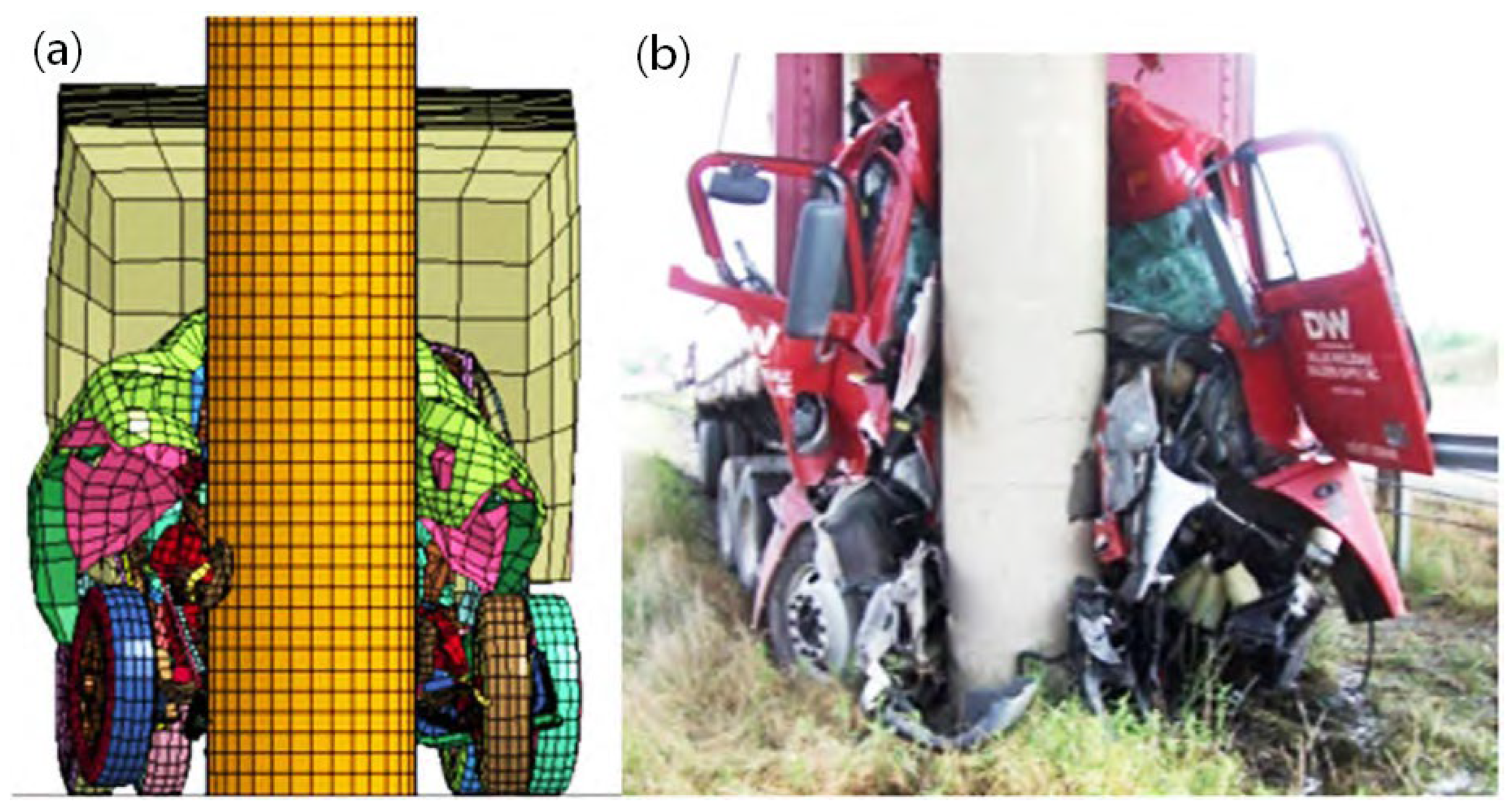

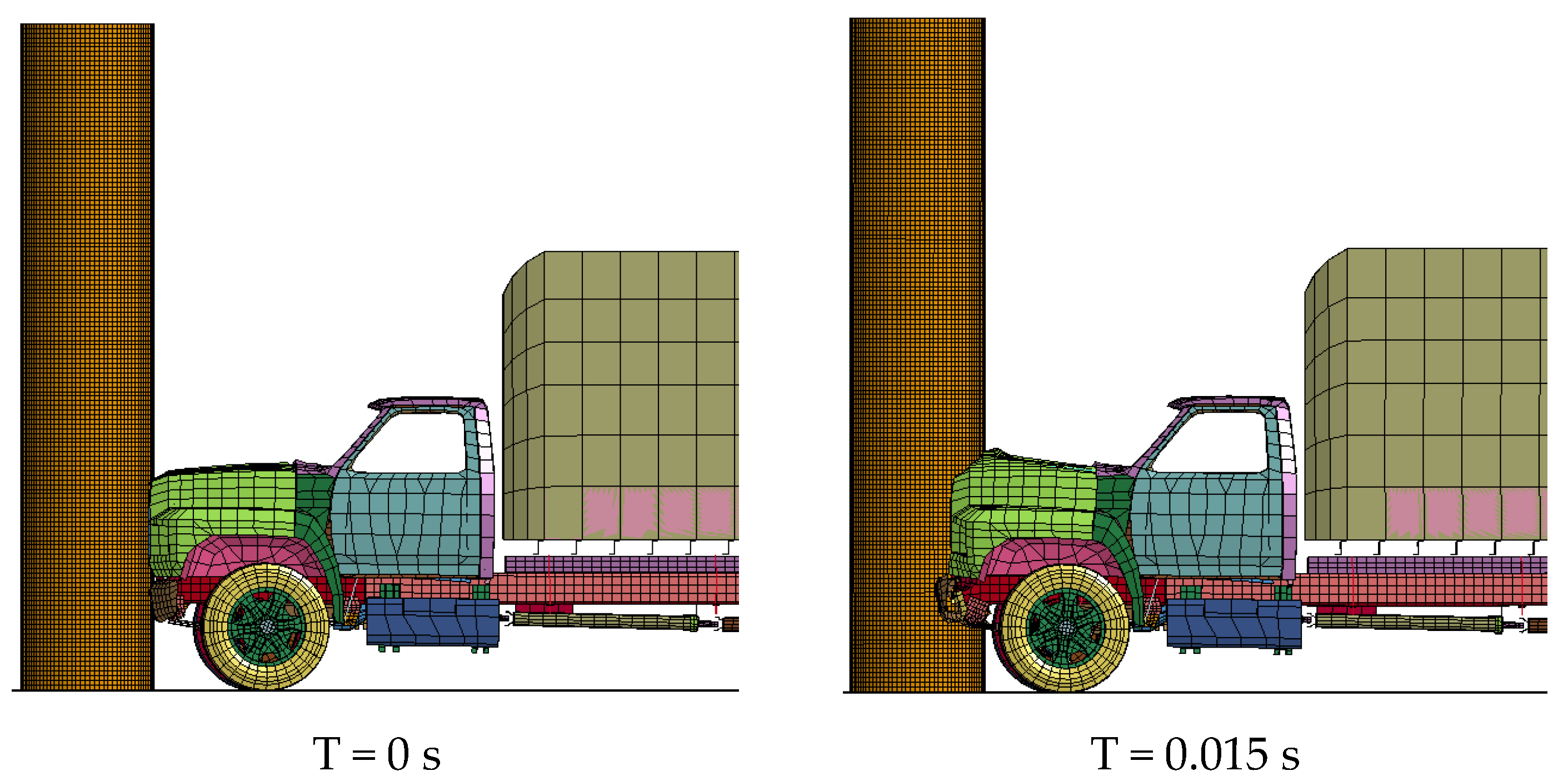

3.2. Verification of Finite Element Analysis Model

3.3. Verification of Grid Independence

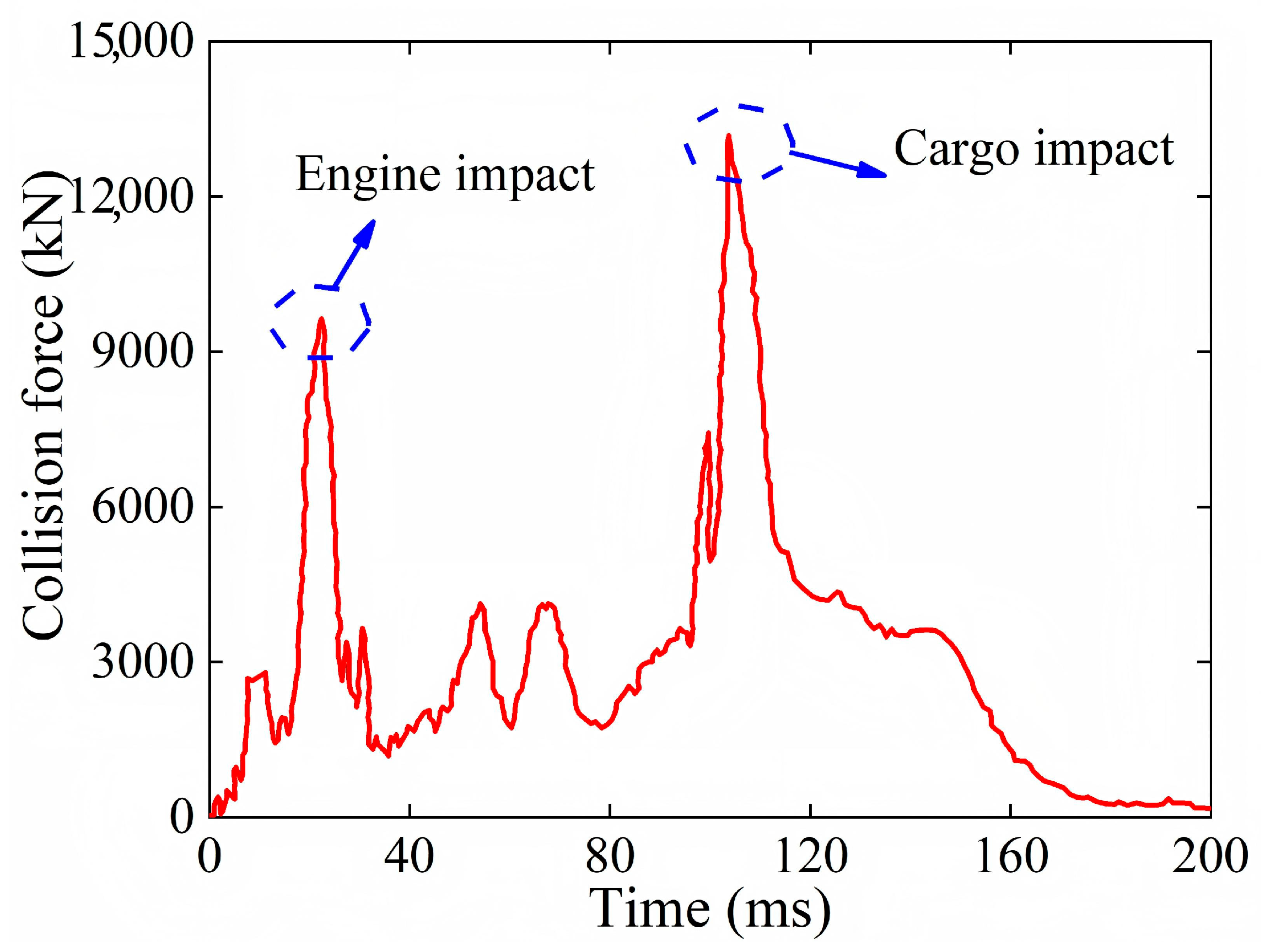

3.4. Collision Force and Vehicle Deformation

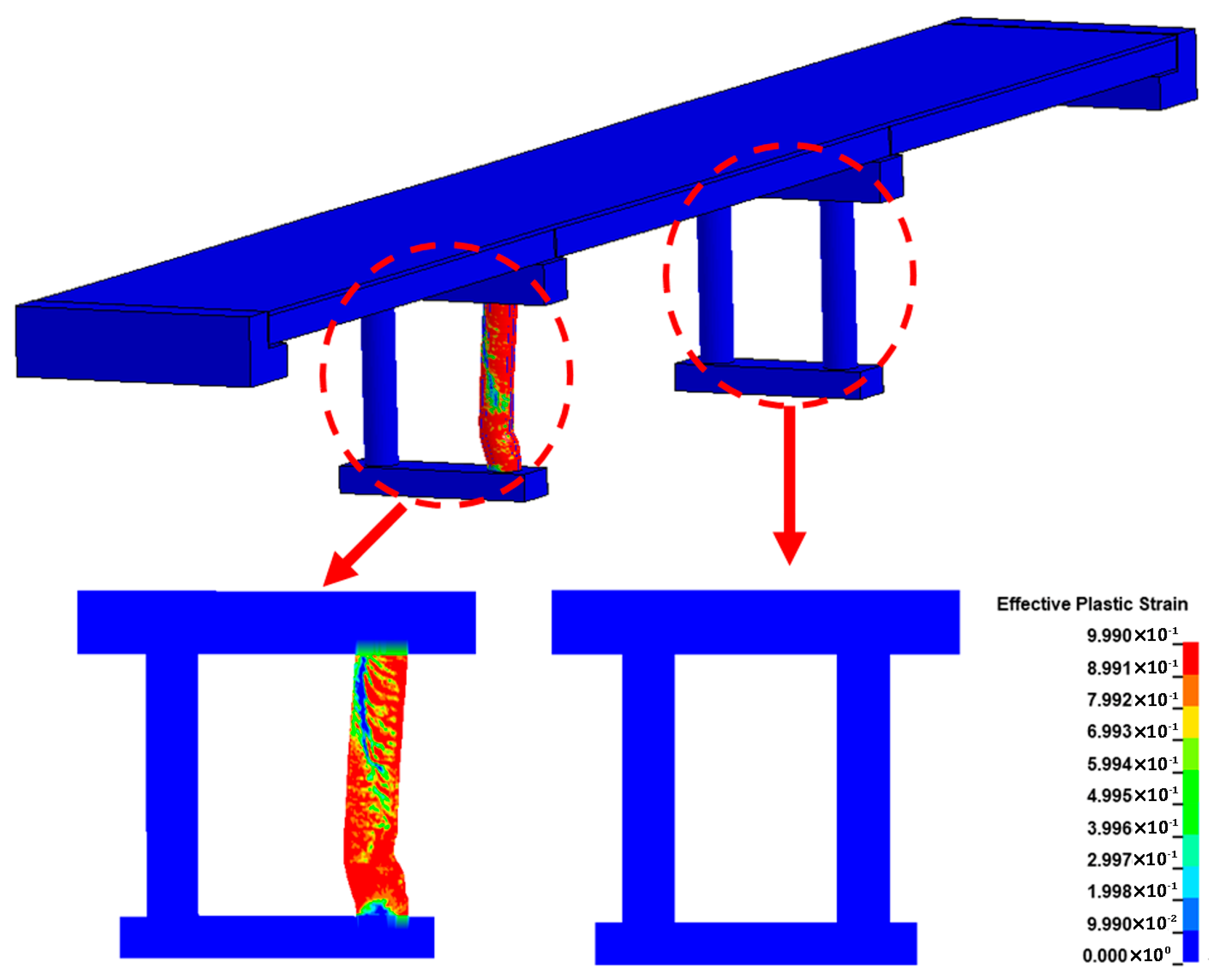

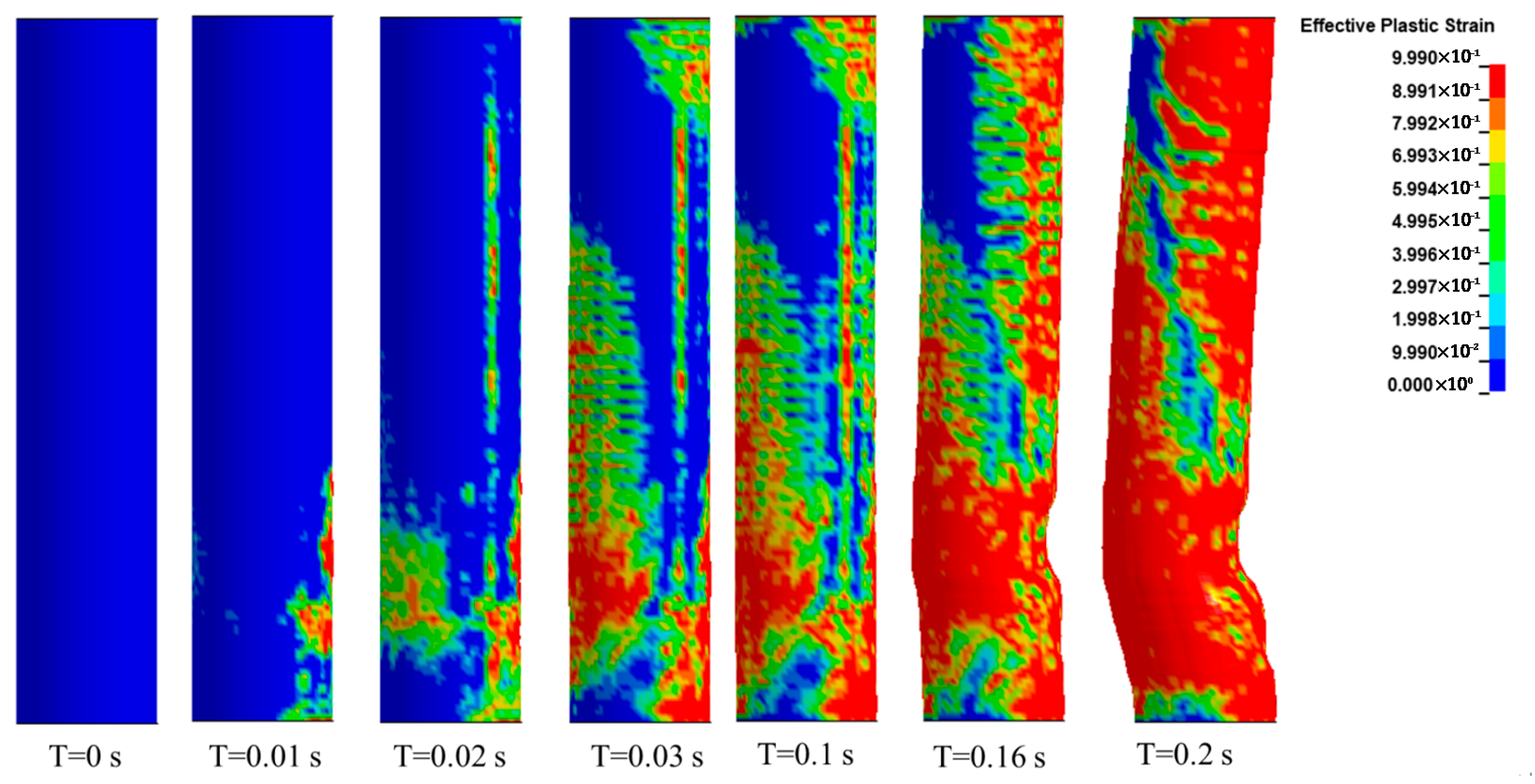

3.5. Bridge Damage

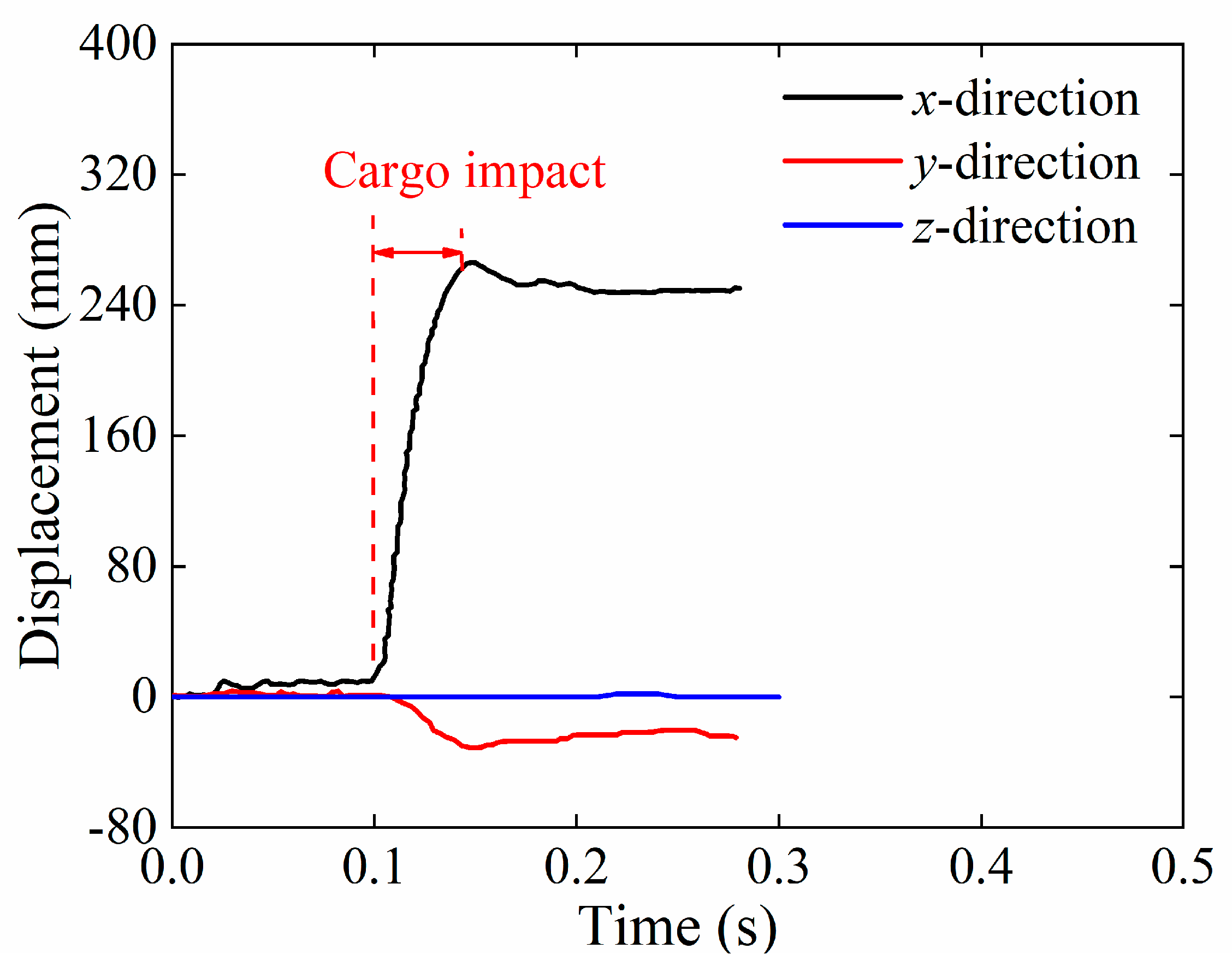

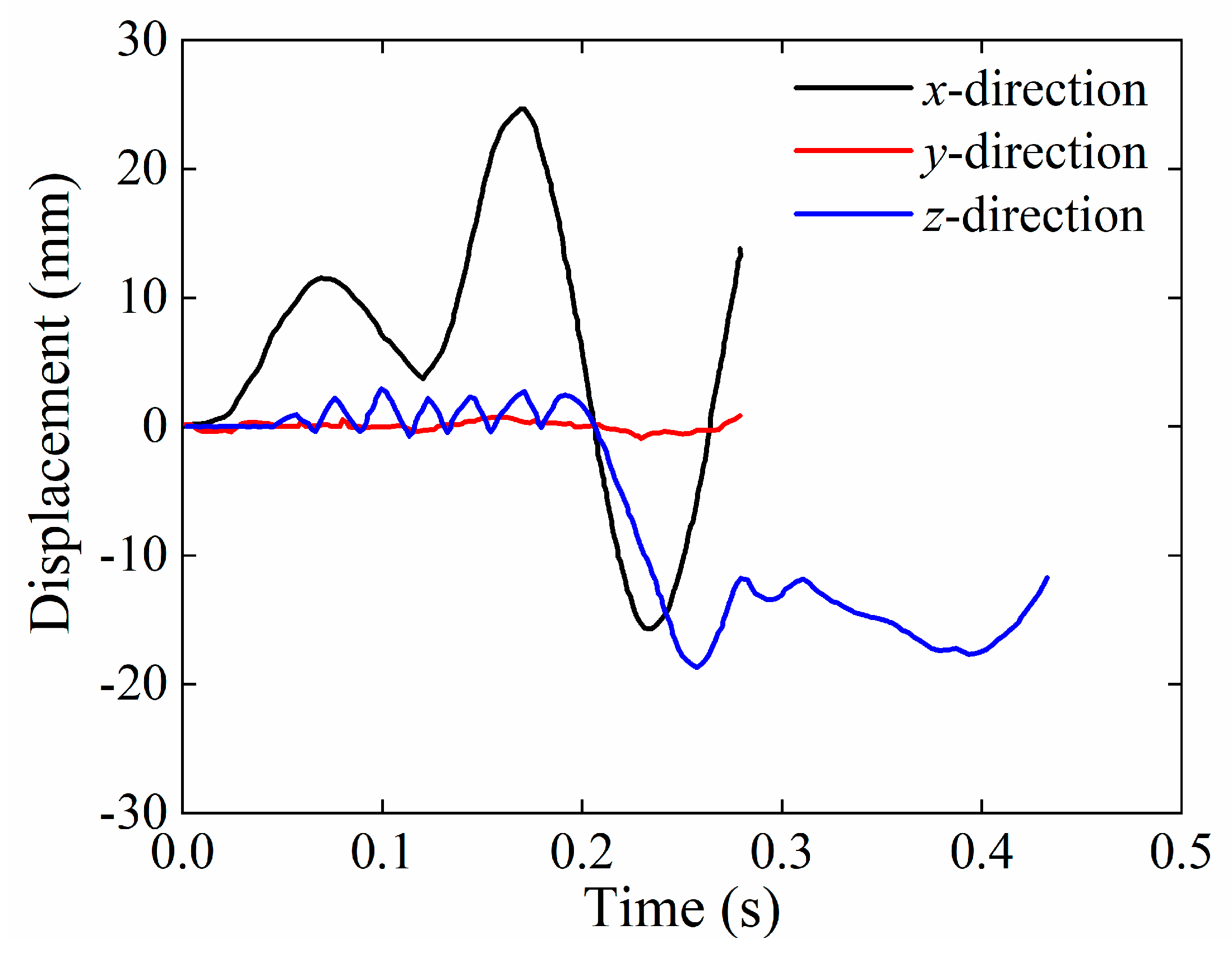

3.6. Collision Response

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- RPC Beam Model Validation: The finite element model of the RPC beam was rigorously validated against drop hammer impact experiments. Overall, the model accurately reproduces the impact response of concrete members. It effectively captures the development of damage patterns and the dynamic behavior under impact loading, demonstrating its reliability as a basis for subsequent vehicle–bridge collision simulations.

- (2)

- Collision Force Characteristics: The bridge pier exhibits distinct dynamic responses under heavy vehicle collisions. Two peak forces were observed, corresponding to the engine and cargo impacts, with the cargo-induced peak approximately 38.2% higher due to its greater mass and inertia. These results emphasize the critical influence of cargo mass on pier impact severity and the need to consider it in design and reinforcement strategies.

- (3)

- Damage Distribution: Damage is primarily concentrated on the impacted pier, while other bridge components remain largely unaffected. Key failure modes include punching shear at the collision face, tensile cracking at the rear, and shear failure near the pier top. The spatial distribution and evolution of damage highlight the importance of localized reinforcement and structural detailing in high-impact zones to mitigate catastrophic failure.

- (4)

- Collision Response: The dynamic response of the pier and superstructure is dominated by horizontal motion. x-direction displacements at the collision point were minimal (<10 mm) for engine impacts but reached up to 264 mm for cargo impacts, accompanied by partial elastic rebound. The cap beam responded primarily in the x- and z-directions, with cargo impacts generating approximately 25 mm in the horizontal direction and about 20 mm in the vertical direction. These observations indicate that cargo collisions govern the overall structural response, highlighting the necessity to account for large displacements in both pier and superstructure design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, W.B.A.; Fan, W.; Yang, C.C.; Peng, W.B. Lessons learned from vehicle collision accident of Dongguofenli Bridge: FE modeling and analysis. Eng. Struct. 2021, 244, 112813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.Y.; Hao, H.; Hao, Y.F. Numerical investigation of impact response of bridge pier subjected to off-center vehicle collision. Eng. Struct. 2024, 317, 118624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, B.Y.; Hu, K.W. Bridge post-disaster rapid inspection using 3D point cloud: A case study on vehicle-bridge collision. J. Infrastruct. Intell. Resil. 2025, 4, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, T.; Hor, Y.; MuI’Nuddin, M.; Saravanan, K.; Shahir, L.M.; Rahman, S.A.; Wong, T.C. Research on HGV collisions with concrete bridge piers. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 567, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.Y.; Li, R.W.; Wang, J.; Guo, C.T. Study on impact behavior and impact force of bridge pier subjected to vehicle collision. Shock. Vib. 2017, 2017, 7085392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, K.; Li, R.W.; Wu, H. Damage assessment of simply supported double-pier bent bridge under heavy truck collision. J. Bridge Eng. 2022, 27, 04022021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echevarria, A.; Zaghi, A.E.; Christenson, R.; Accorsi, M. CFFT bridge columns for multihazard resilience. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 142, C4015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Fang, Y.C.; Chiu, Y.F.; Wu, Y.W.; Lin, T.C. Design and maintenance information integration for concrete bridge assessment and disaster prevention. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2021, 35, 04021015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, H.; Fang, Q.; Li, R.W. Full-scale experimental study of a reinforced concrete bridge pier under truck collision. J. Bridge Eng. 2021, 26, 05021008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, X. Resistance of reinforced concrete structures and their road load-bearing properties to disasters. J. Struct. Des. Constr. Pract. 2025, 30, 04025075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebinia, F.; Zhang, L.D.; Park, S.; Sepasgozar, S. Numerically evaluation of FRP-strengthened members under dynamic impact loading. Buildings 2021, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.B.; Zhou, H.; Wu, M. Dynamic performance analysis of precast segment column reinforced with CFRP subject to vehicle collision. Buildings 2024, 14, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.H.; Chen, Y.H.; He, Y. Vulnerability assessment of reinforced concrete piers under vehicle collision considering the influence of uncertainty. Buildings 2025, 15, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rys, D.; Judycki, J.; Jaskula, P. Determination of vehicles load equivalency factors for polish catalogue of typical flexible and semi-rigid pavement structures. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 2382–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG D60-2015; General Specifications for Design of Highway Bridges and Culverts. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- AASHTO L. Bridge Design Specifications, 2014; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Wash-ington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Liu, B.; Consolazio, R. Residual capacity of axially loaded circular RC columns after lateral low-velocity impact. J. Struct. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikake, K.; Li, B.; Soeun, S. Impact response of reinforced concrete beam and its analytical evaluation. J. Struct. Eng. 2009, 135, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikake, K.; Senga, T.; Ueda, N.; Ohno, T.; Katagiri, M. Study on impact response of reactive powder concrete beam and its analytical model. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2006, 4, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lu, X.Z.; Smith, S.T.; He, S.T. Scaled model test for collision between over-height truck and bridge superstructure. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2012, 49, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Banthia, N.; Kim, S.W.; Yoon, Y.S. Response of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete beams with continuous steel reinforcement subjected to low-velocity impact loading. Compos. Struct. 2015, 126, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buth, C.E.; Brackin, M.S.; Williams, W.F.; Fry, G.T. Collision Loads on Bridge Piers: Phase 2, Report of Guidelines for Designing Bridge Piers and Abutments for Vehicle Collisions; Texas Transportation Institute: College Station, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Yan, X.; Guo, X.; Liu, C.L.; Agrawal, A.K. Test and numerical simulation of truck collision with anti-ram bollards. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2015, 75, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, L.; El-Tawil, S. Impact tests of model RC columns by an equivalent truck frame. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 142, 04016002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; El-Tawil, S.; Xiao, Y. Reduced models for simulating collisions between trucks and bridge piers. J. Bridge Eng. 2016, 21, 04016020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkarim, O.I.; Elgawady, M.A. Performance of bridge piers under vehicle collision. Eng. Struct. 2017, 140, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Liu, G.Y.; Alampalli, S. Effects of truck impacts on bridge piers. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 639, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Agrawal, A.K.; El-Tawil, S.; Xu, X.C.; Wong, W. Heavy truck collision with bridge piers: Computational simulation study. J. Bridge Eng. 2019, 24, 04019052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, X.D. Performance and sensitivity analysis of UHPFRC-strengthened bridge columns subjected to vehicle collisions. Eng. Struct. 2018, 173, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.W.; Wang, L.B.; Shu, H.; Liu, X.G.; Liu, Y.X.; Chen, K.F. Analysis of vehicle-bridge coupled vibration and driving comfort of a PC beam-steel box arch composite system for autonomous vehicles. Buildings 2025, 15, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubliner, J.; Oliver, J.; Oller, S.; Onate, E. A plastic-damage model for concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1989, 25, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Fenves, G.L. Plastic-damage model for cyclic loading of concrete structures. J. Eng. Mech.-ASCE 1998, 124, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEB-FIP. Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures; Ernst & Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OoYang, X.; Wu, Z.M.; Shan, B.; Chen, Q.K.; Shi, C. A critical review on compressive behavior and empirical constitutive models of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.K.; Sun, H.C.; Fan, J.B.; Xian, X.L. Analysis of shear mechanical properties of RPC-NC interface. J. Lanzhou Jiaotong Univ. 2023, 42, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.J.; Su, J.Y. Dynamic Analysismethods and Engineering Examples of ANSYS/LS-DYNA; China Water Power Press: Beijing, China, 2006. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.P.; Liu, W.F.; Guo, J.B.; Du, T.; Guo, E. Refined modeling method of vehicle impact concrete pier. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 1666–1674. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fiber Volume Fraction (%) | Water-Cement Ratio (%) | Water *1 (kg/m) | Pre-Blended Powders (kg/m2) | Steel Fiber (kg/m2) | Superplasticizer (kg/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 22.0 | 180 | 2254 | 157 | 25 |

| Kc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 0.1 | 1.16 | 0.667 | 0.005 |

| Yield Stress (MPa) | Plastic Strain | Flexible Damage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 360 | 0 | Breaking strain | Triaxial stress | Strain ratio |

| 385 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 30 |

| 395 | 0.02 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 30 |

| 401 | 0.1 | Damage evolution | ||

| 427 | 0.15 | Damage displacement | ||

| 440 | 0.4 | 0.02 | ||

| 454 | 1 | |||

| 525 | 4 | |||

| Grid Size (mm) | Size of Impact Force (kN) | Displacement of Collision Point (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 35 | 3493 | 1.87 |

| 50 | 3579 | 1.89 |

| 100 | 3954 | 2.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Geng, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zhu, J.; Yang, B.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C. Structural Response and Damage of RPC Bridge Piers Under Heavy Vehicle Impact: A High-Fidelity FE Study. Buildings 2026, 16, 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030549

Geng Y, Zheng T, Zhu J, Yang B, Wang H, Zhao C. Structural Response and Damage of RPC Bridge Piers Under Heavy Vehicle Impact: A High-Fidelity FE Study. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):549. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030549

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Yanqiong, Tengteng Zheng, Jinjun Zhu, Buren Yang, Hui Wang, and Caiqi Zhao. 2026. "Structural Response and Damage of RPC Bridge Piers Under Heavy Vehicle Impact: A High-Fidelity FE Study" Buildings 16, no. 3: 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030549

APA StyleGeng, Y., Zheng, T., Zhu, J., Yang, B., Wang, H., & Zhao, C. (2026). Structural Response and Damage of RPC Bridge Piers Under Heavy Vehicle Impact: A High-Fidelity FE Study. Buildings, 16(3), 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030549