Designing for Health and Learning: Lessons Learned from a Case Study of the Evidence-Based Health Design Process for a Rooftop Garden at a Danish Social and Healthcare School

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nature, Human Health and Landscape Architecture

1.2. Working Evidence-Based in Landscape Architecture for Human Health

1.3. Applying the EBHDL Process Model

1.4. The Case—Context and Commission of the Care Outside Project

1.5. Motivation and Aim of the Case Study

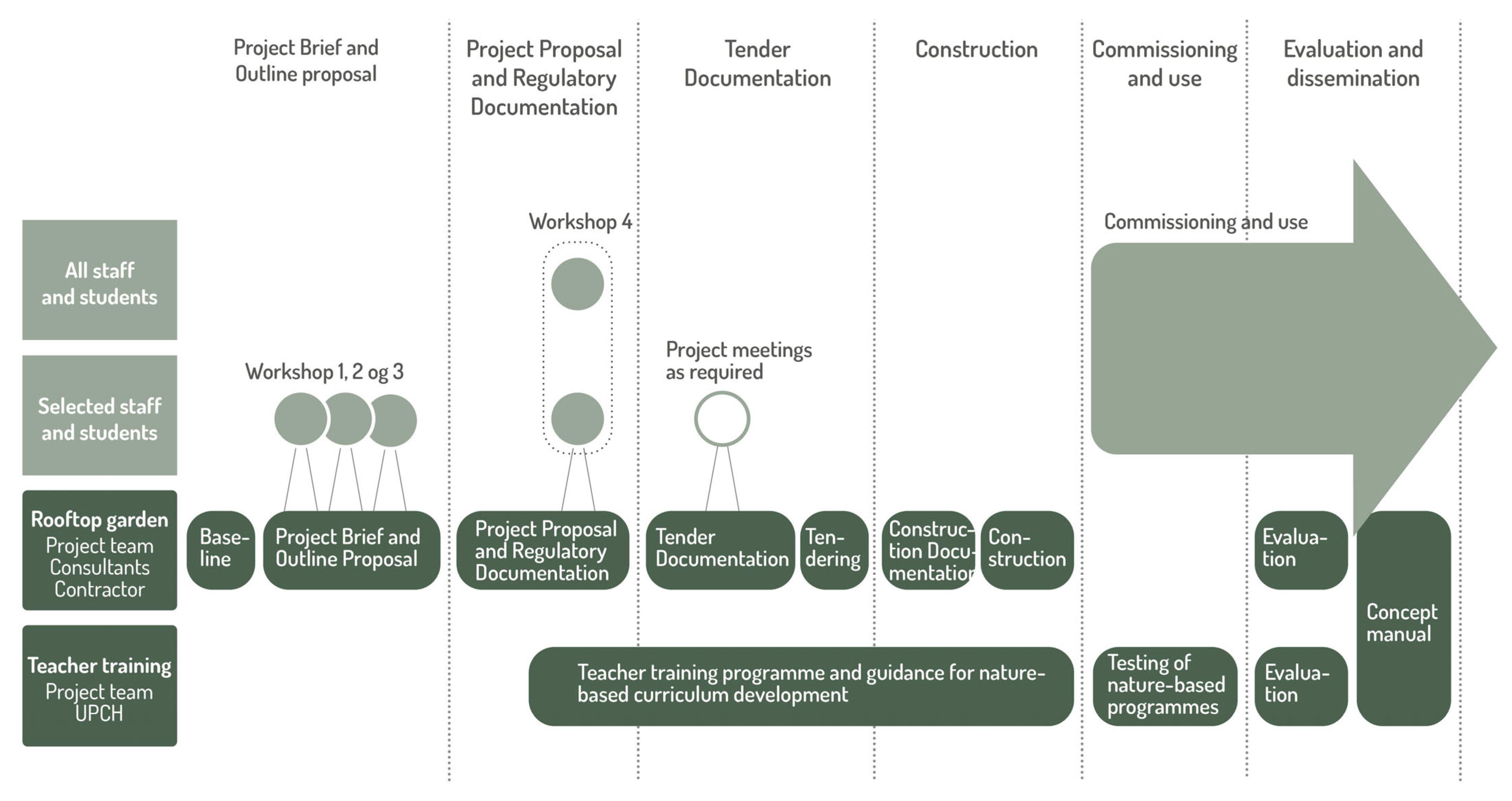

2. Project Context and Construction Framework

2.1. Danish Construction Phases

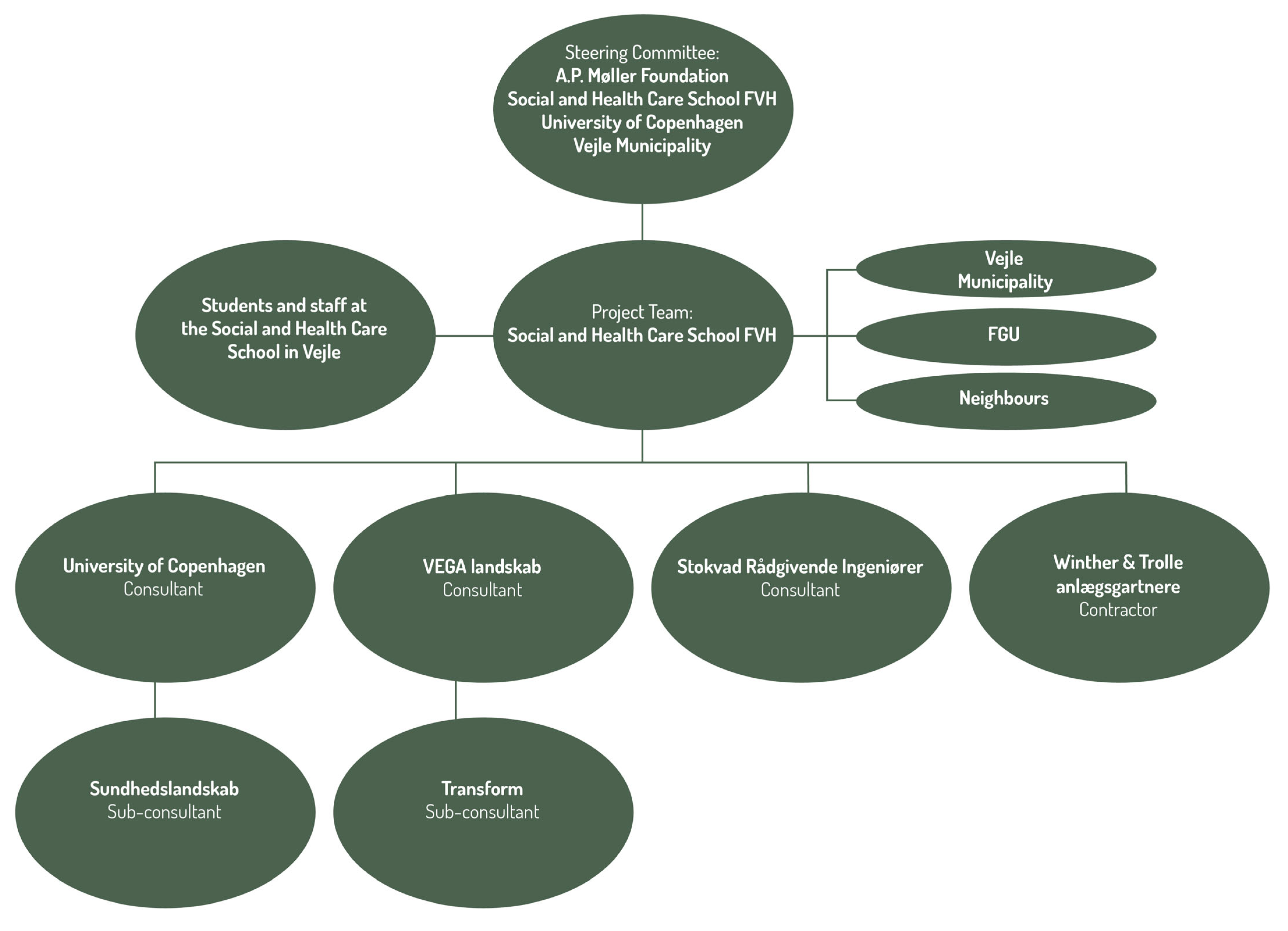

2.2. Stakeholder Roles and Phase-Specific Engagement

2.3. Mapping the EBHDL Process onto the Danish Construction Framework

2.4. Key Stakeholders

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Approach: Documenting and Analysing an Evidence-Informed, Practice-Based Design Process

3.2. Analysing the Design and Construction Process

4. Process Insights

4.1. Identification of Governance Structures and Roles

Lessons Learned

4.2. Clarifying Required Competences and Establishing the Aim of the Design

Lessons Learned

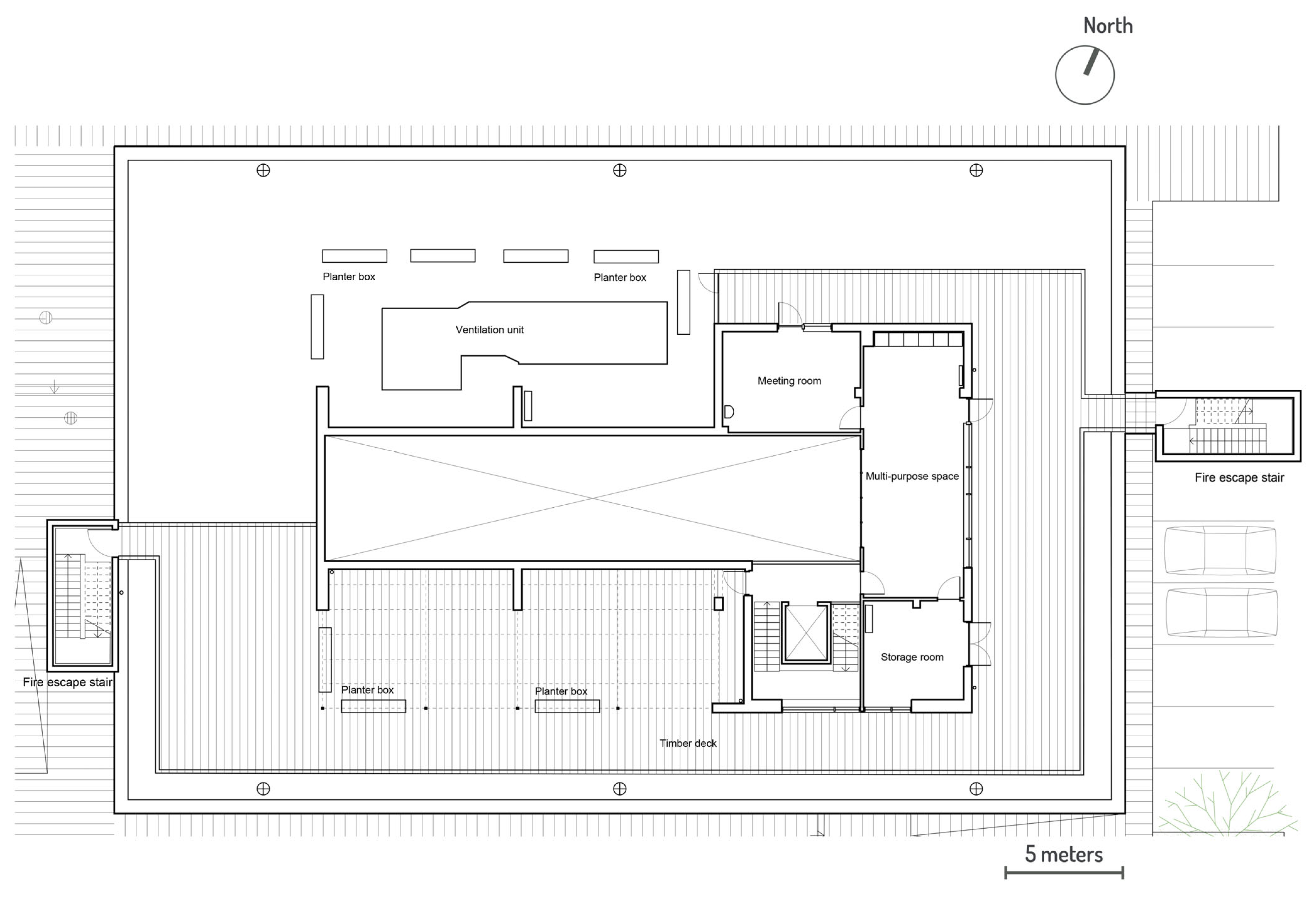

4.3. Understanding the Premises of the Chosen Site

Lessons Learned

4.4. Process Diagram: A Tool for Overview and Coordination

Lessons Learned

4.5. Evidence Collection: First Step of the EBHDL Process Model

Lessons Learned

4.6. Programming: Second Step in the EBHDL Process Model

Lessons Learned

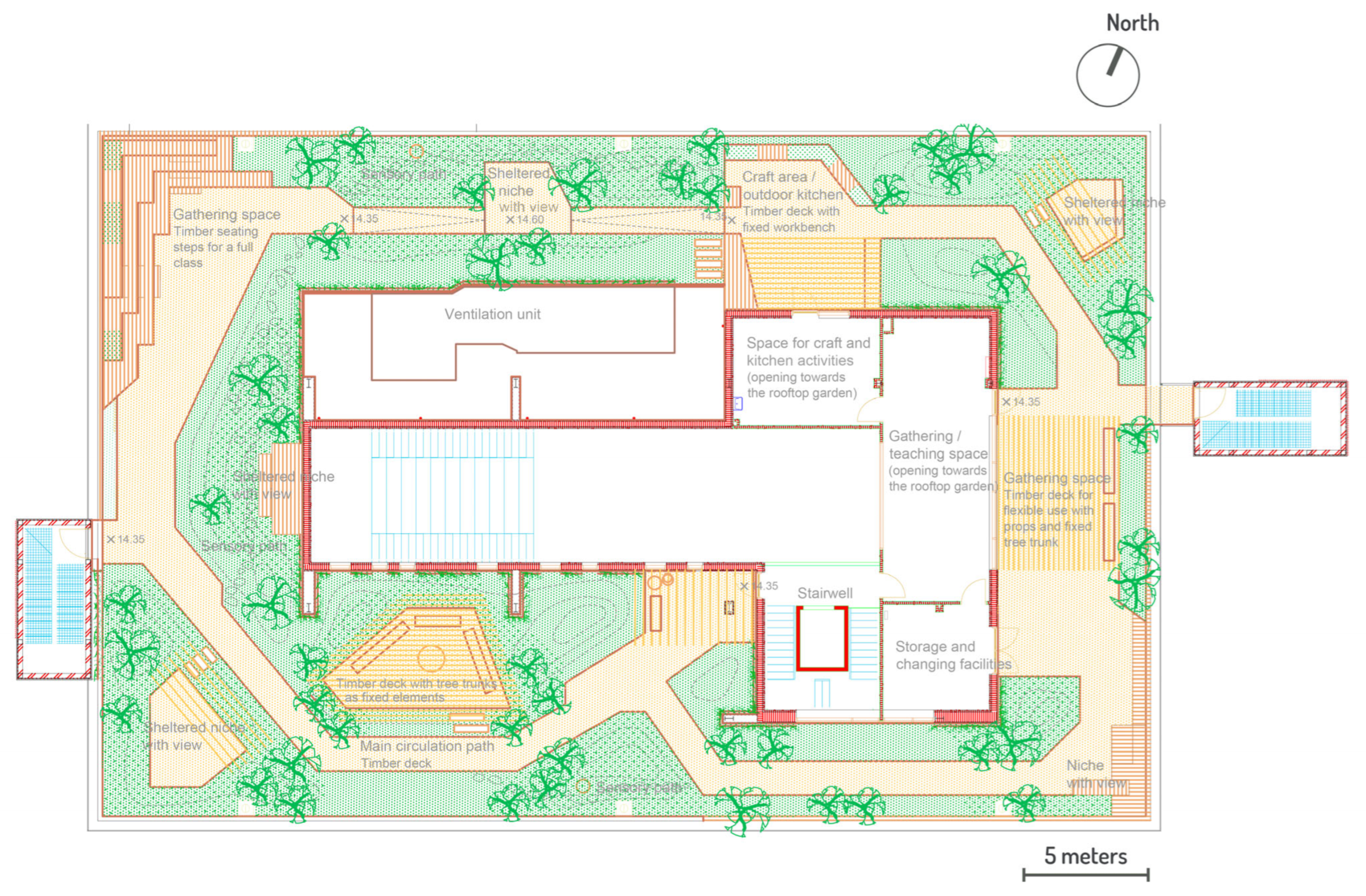

4.7. Design: Third Step in the EBHDL Process Model

4.7.1. Conceptualisations

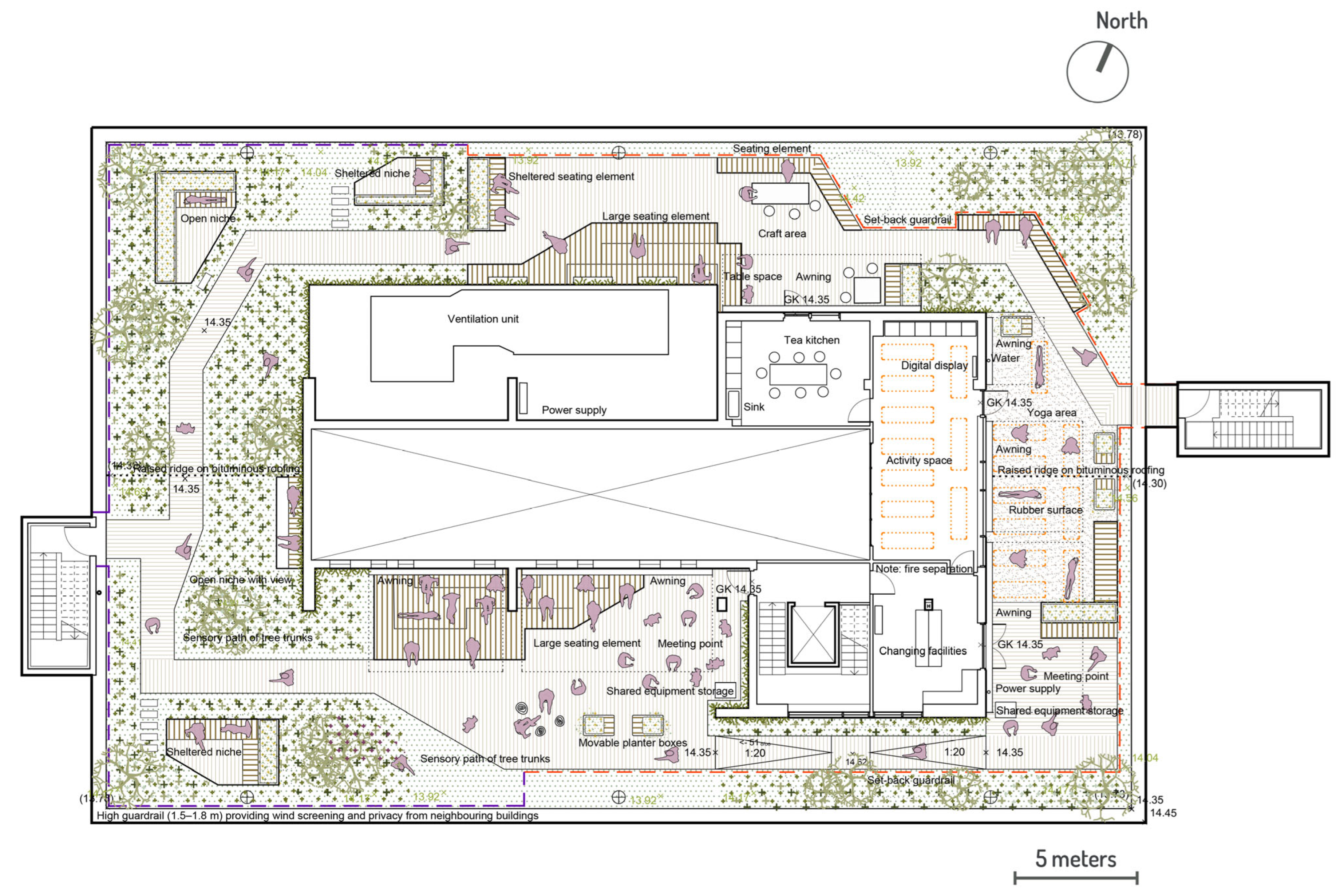

4.7.2. Design

4.7.3. Construction

4.7.4. Lessons Learned

5. Discussion

5.1. EBHDL as a Framework for Design and Decision-Making

5.2. Operationalising EBHDL Across Diverse Contexts

5.3. Practical Lessons and Co-Design

5.4. Transferability, Strengths and Limitations

5.5. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Marcus, C.C.; Sachs, N.A. Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Sun, R.; Vejre, H. Links between green space and public health: A bibliometric review of global research trends and future prospects from 1901 to 2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Hartig, T.; Martin, L.; Pahl, S.; van den Berg, A.E.; Wells, N.M.; Costongs, C.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Elliott, L.R.; Godfrey, A.; et al. Nature-based biopsychosocial resilience: An integrative theoretical framework for research on nature and health. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, M.; Sang, A.O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health—A systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Ekholm, O.; Schipperijn, J.; Toftager, M.; Kamper-Jørgensen, F.; Randrup, T.B. Health promoting outdoor environments: Associations between green space, and health, health-related quality of life and stress based on a Danish national representative survey. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson-Coon, J.; Boddy, K.; Stein, K.; Whear, R.; Barton, J.; Depledge, M.H. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; van den Berg, A.E.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Tomalak, M.; Bauer, N.; Hansmann, R.; Ojala, A.; Syngollitou, E.; Carrus, G.; van Herzele, A.; et al. Health benefits of nature experience: Psychological, social and cultural processes. In Forests, Trees and Human Health; Nilsson, K., Sangster, M., Gallis, C., Hartig, T., de Vries, S., Seeland, K., Schipperijn, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Nyed, P.K.; Larsen, H.B.; Fjorbak, L.O. Efficacy of nature-based therapy for individuals with stress-related illnesses: Randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, A.; Timperio, A.; Veitch, J. Participatory school ground design: Play behaviour and student and teacher views of a school ground post-construction. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, T.; Loebach, J.; Ramsden, R.; Cox, A.; Joyce, K.; Brussoni, M. Running the risk: The social, behavioral and environmental associations with positive risk in children’s play activities in outdoor playspaces. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2023, 26, 307–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk-Wesselius, J.E.; Maas, J.; Hovinga, D.; van Vugt, M.; van den Berg, A.E. The impact of greening schoolyards on the appreciation, and physical, cognitive and social-emotional well-being of schoolchildren: A prospective intervention study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.; Klein, S.E.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Zaplatosch, J. Greening for academic achievement: Prioritizing what to plant and where. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 206, 103962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; McGeown, S.; Bell, S. Improving outdoor pedagogy through design: Reflections on the process of redesigning a school landscape. J. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 19, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korcz, N.; Janeczko, E.; Bielinis, E.; Urban, D.; Koba, J.; Szabat, P.; Małecki, M. Influence of informal education in the forest stand redevelopment area on the psychological restoration of working adults. Forests 2021, 12, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K. Nature, health & design. Alam Cipta Int. J. Sustain. Trop. Des. Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Sidenius, U. Keeping promises—How to attain the goal of designing health-supporting urban green space. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 8, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, J. Inquiry by Design: Environment/Behavior/Neuroscience in Architecture, Interiors, Landscape, and Planning; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.D.; Corry, R.C. Evidence-Based Landscape Architecture for Human Health and Well-Being. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Zhang, G.; Gramkow, M.C.; Sidenius, U. Viewpoint on what may be considered as evidence and how to obtain it when designing health-promoting and inclusive green spaces. Int. J. Arch. Res. Archnet-IJAR 2023, 18, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramkow, M.C.; Sidenus, U.; Zhang, G.; Stigsdotter, U.K. From Evidence to Design Solution—On How to Handle Evidence in the Design Process of Sustainable, Accessible and Health-Promoting Landscapes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pálsdóttir, A.M.; Thorpert, P.; Gudnason, V.; Settergren, H.; Víkingsson, A.; Siggeirsdóttir, K. Conceptual biophilic design in landscape architecture—A design concept for a health garden in Iceland. J. Ther. Hortic. 2021, 31, 39–56. Available online: https://publications.slu.se/?file=publ/show&id=114553 (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- American Society of Landscape Architects. 2023 ASLA Student Awards: Honor Award in Research—Toward Dynamic Optimization: Combining AI and EBHDL for the Elderly. 2023. Available online: https://www.asla.org/awards (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- FRI; Danske Arkitektvirksomheder. Ydelsesbeskrivelse for Byggeri Og Landskab 2018. Frinet.dk. 2018. Available online: https://www.frinet.dk/vaerktoejer/ydelsesbeskrivelser/ydelsesbeskrivelsen-for-byggeri-og-landskab-2018/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Royal Institute of British Architects. RIBA Plan of Work 2020 Overview. 2020. Available online: https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/riba-plan-of-work (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- HOAI. Leistungsphasen Der HOAI. 2021. Available online: https://www.hoai.de/hoai/leistungsphasen/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Danske Ark. Ydelsesbeskrivelse for Byggeri og Landskab 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.danskeark.dk/content/ydelsesbeskrivelse-byggeri-og-landskab-2018-0 (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Byggeriets Aftalevilkår. AB 18—Almindelige Betingelser for Arbejder Og Leverancer i Bygge- Og Anlægsvirksomhed. Transport-, Bygnings- Og Boligministeriet. 2018. Available online: https://www.danskeark.dk/sites/default/files/2023-01/AB18.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. Prospects and refuges re-visited. Landsc. J. 1984, 3, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Grahn, P. Om stödjande miljöer och rofyllda ljud [On supportive environments and restful sounds]. In Ljudmiljö, Hälsa Och Stadsbyggnad 2011; Mossberg, F., Ed.; Ljudmiljöcentrum, Lunds universitet: Lund, Sweden, 2011; pp. 42–55. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de la Guía, L.; Puyuelo Cazorla, M.; de-Miguel-Molina, B. Terms and meanings of “participation” in product design: From “user involvement” to “co-design”. Des. J. 2017, 20, S4539–S4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order | Phase | Phase in Danish | Content | Selected Deliverables | Key Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial Advisory Service, comprising Concept Development and Project Brief | Indledende rådgivning, bestående af Idéoplæg og Byggeprogram | Identification of needs, establishment of project vision and goals, functional requirements, site analysis, feasibility studies, stakeholder dialogue, and preparation of a Concept Proposal and Project Brief. | Functional requirements, concept sketches and conceptual descriptions, initial budget and schedule, project brief | Client, Client Advisor, Users |

| 2 | Design Proposal, comprising Outline Proposal and Project Proposal | Forslag, bestående af Dispotions- forslag og Projektforslag | Conceptual ideas are developed into concrete design solutions by defining spatial organisation and design principles, considering materials and technical options, assessing sustainability and costs, and preparing preliminary design documentation. | Drawings and digital models, descriptions and updated budget | Consultants, Users (Approval of Design Proposal: Client, supported by Client Advisor) |

| 3 | Regulatory Documentation | Myndighedsprojekt | Preparation and submission of building permit applications, including energy, fire safety, accessibility and other statutory documentation required by authorities. | Permit application package, compliance documentation | Consultants |

| 4 | Tender Documentation | Udbudsprojekt | Preparation of a complete tender package that defines the project clearly and in sufficient detail to form the basis for tendering and contracting, and to support the subsequent preparation of construction documentation and execution. | Tender conditions, drawings and digital models, specifications, bills of quantities and draft contracts | Consultants (Approval of Tender Documentation: Client, supported by Client Advisor) |

| 5 | Construction Documentation | Udførselsprojekt | The construction documentation is based on the accepted tenders and develops the tender documentation into a final coordinated execution project, ensuring constructability and cross-disciplinary consistency. | Detailed working drawings and digital models, coordinated specifications, execution documents, updated budget and risk assessment | Consultants, Contractor (Approval of Construction Documentation: Client, supported by Client Advisor) |

| 6 | Construction Execution | Udførelse | Implementation of the construction works according to approved plans and documentation, supported by construction management, site supervision and project follow-up. | Executed construction works, supervision reports, site meeting minutes, updated project documentation | Contractor (supervision by Consultants) |

| 7 | Handover and Deficiencies | Aflevering | Final inspections, preparation of deficiency lists, testing and commissioning, delivery of as-built documentation, and formal transfer to the client. | Handover protocol, deficiency report, as-built documentation, and operation and maintenance manuals | Contractor, Consultants, Client, supported by Client advisor |

| Work- Shop | Title of Workshop | Objectives of the Workshop | Workshop Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Input for the EBHDL Programme and the design of the rooftop garden | 1. To introduce participants to the rooftop garden development process and clarify their role within it. | Participants included teachers selected according to their subject areas and roles within the school; students from the student council; a member of the service staff; a mentor from Vejle Municipality; the project team; the landscape architect from VEGA landskab; and facilitators from the UCPH team. |

| 2. To encourage participants to reflect on elements that contribute to a meaningful experience of the rooftop garden. | |||

| 3. To collect participants’ input regarding potential activities in the rooftop garden. | |||

| 4. To identify key facilitators and barriers to the use of the rooftop garden. | |||

| 2 | Feedback on the rooftop garden design | 1. To prompt participants to consider how they might adapt their current practices to enhance the benefits of the rooftop garden. | Same as Workshop 1 |

| 2. To gather feedback on the initial rooftop garden design, based on various teaching and wellbeing scenarios. | |||

| 3 | Testing Design Elements in a Natural Forest Environment | 1. To provide participants with hands-on experience in using nature within educational programmes, including group work, individual immersion and restorative activities. | Same as Workshop 1 |

| 2. To support reflection on how this experience informs their expectations and aspirations for the rooftop garden. | |||

| 4 | Presentation and Discussion on the Final Rooftop Garden Design | 1. To present and discuss the final rooftop garden design, demonstrating how input from staff and students has been integrated through the co-creation process. | Participants included all students and staff; internship providers and other partners from Vejle Municipality; neighbouring residents; potential collaborators; the project team; the landscape architect from VEGA landskab; and a landscape architect from the UCPH team. |

| 2. To provide an update on the status of the teacher training programme. | |||

| 3. To provide an update on the collaboration with internship sites on nature-based activities |

| Target Group | ||||

| Evidence | Design Criteria | Design Solution | Number | Conceptualisations |

| Students; Wide age range, culturally diverse, many not keen on outdoor experiences | The design should be inclusive, safe and supportive, where all students and staff have the opportunity to participate based on their own abilities. | The rooftop is designed so it is experienced as a secure, non-threatening space in regard to design or plant material. | 1 | |

| The garden should be easy to interpret and there is no single ‘right way’ to use the garden. | A clear design language that guides students’ use of the garden. | |||

| Students not always used to spending time in natural environments. Teaching staff not used to nature-based teaching. | The design should support both the students and teachers to actively use the garden all year around. | Transition zones between indoors and outdoors are needed to support both students and teachers. | 2 |  |

| The students are challenged with poor mental, physical and social health. | The design should offer nature experiences (PSDs, four components from ART that constitute restorative environments) and activities preferred by the students. | Nature experiences offering mental restoration. Possibilities for different levels of physical training along paths and in specific spaces. Possibilities for both social and solitary activities. | 3 |  |

| Nature and Human Health Relationship | ||||

| Evidence | Design Criteria | Design Solution | Number | Conceptualisations |

| Attention Restoration Theory posits that humans use two types of attention: directed attention, which requires effort and can lead to mental fatigue, and involuntary attention, which is effortlessly captured by certain stimuli. Exposure to natural environments that engage involuntary attention can support recovery from mental fatigue. | In order for an environment to be perceived as restorative it should offer the following components:

| All four components should be present throughout the garden. Being away: Visiting the garden enables students to leave the school’s physical environment behind. Long views from the site guide the placement of spaces and functions to reinforce this sense of detachment. Extent: A coherent spatial character is created through a continuous ground layer of vegetation, with varied planting that supports orientation and exploration. Fascination: The site’s elongated views offer visual interest at key vantage points, while the diversity and detail of the planting provide sensory engagement at a smaller scale. Compatibility: The garden is intuitively readable and supports intended activities. What users imagine doing in the space is both understandable and achievable. | 4 | |

| The Supportive Environment Theory Pyramid illustrates how individuals’ experiences of nature—and the level of demands they can manage—depend on their emotional and cognitive resources. The model consists of four levels, with a greater need for low-demand green spaces at the base and a lesser need at the top. | The design should address all four levels of the pyramid, considering mental, physical and social demands. | All four levels are represented across the area. Locations are arranged to avoid conflict between high- and low-demand environments. Off-track paths and smaller spaces offer opportunities for closer contact with nature, either individually or in groups. | 5 |  |

| Prospect-Refuge Theory suggests that humans seek environments offering both prospect—open, brightly lit views over long distances—and refuge—places of concealment and protection, typically small and enclosed. These contrasting perceptions must co-exist to create a sense of safety and comfort. | The design should provide simultaneous experiences of prospect and refuge. | Refuge is created using terrain, vegetation and lightweight constructions, reducing structural load. Prospect is offered through open views to the surroundings. Refuge areas are placed to avoid disturbance from more dynamic or ‘wild’ activities, ensuring calm and protected experiences. | 6 |  |

| The Perceived Sensory Dimensions (PSD) framework describes how people experience green spaces through eight distinct dimensions, some of which are more preferred than others. In general, ‘serene’ is the most preferred, followed by ‘space’, ‘nature’, ‘rich in species’, ‘refuge’, ‘culture’, ‘prospect’ and ‘social’. Among these, ‘refuge’, ‘nature’ and ‘rich in species’ are most strongly associated with the preferences of individuals experiencing stress. A combination of these dimensions, with minimal presence of ‘social’, is considered to best match the needs and preferences of this group. | All eight PSDs should be represented in the design. | Different areas of the site support different health dimensions: Areas targeting mental health emphasise ‘refuge’, ‘nature’ and ‘rich in species’. Areas targeting physical health include ‘prospect’, ‘refuge’, ‘rich in species’ and ‘space’. Areas targeting social health are dominated by ‘social’, combined with other PSDs. To meet the school’s request for high biodiversity, the PSD ‘Rich in Species’ is present throughout the garden. Plant selection is based on perceived biodiversity to enhance users’ experience and understanding. | 7 |  |

| Affordances are functional properties of an environmental feature relative to an individual, indicating which actions are possible in the setting and which may be excluded. | The design should encourage meaningful functions that the individual user is able to carry out. | Environmental features offering multiple meaningful functions are distributed throughout the area. The diversity of user groups (age, gender, experience with nature, etc.) is supported by a range of activity options, combining more naturalistic elements with constructed ones. | 8 |  |

| Environment | ||||

| Evidence | Design Criteria | Design Solution | Number | Conceptualisations |

| Allowing vegetation to dominate through extensive use of living plant material creates positive effects on psychological restoration and sensory engagement. | The rooftop garden should be one cohesive space shaped by living material, in which spaces with appropriate sizes for the teaching needs are created. | Maximises vegetation coverage within the roof’s load-bearing capacity constraints, while creating smaller spaces sized appropriately for teaching activities and students’ free periods. | 9 |  |

| The view from the rooftop garden is currently its greatest resource. | The design should enhance the views of the surroundings. | Important views of the forest, the city, the mill, the stream and the sunrise should be preserved and enhanced, for example, by shielding disruptive views. | 10 |  |

| The roof’s load-bearing capacity is a crucial factor in determining the potential for experiences and activities in the rooftop garden. | The rooftop garden will be designed in accordance with the roof’s load-bearing capacity. | The rooftop garden will be designed so that vegetation is placed where the roof’s load-bearing capacity is greatest, thereby allowing for the thickest soil layer. In this way, the garden’s plants can achieve their maximum growth potential. A steel skeleton will carry the main path, which must be constructed from wood due to weight constraints; consequently, organic forms are not feasible. | 11 |  |

| Use of Nature | ||||

| Evidence | Design Criteria | Design Solution | Number | Conceptualisations |

| Students should be able to visit the rooftop garden during breaks from teaching activities. | The garden should be open to students, allowing them to use it freely. | The garden’s spaces, varying in size and furnished for multifunctional use, offer students opportunities for both short and extended breaks, supporting moments of solitude as well as social interaction. | 12 | |

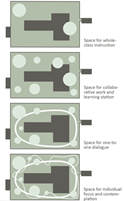

| Teaching staff: The design of the rooftop garden is intended to meet the teaching staff’s needs in relation to implementing nature-based teaching practices. | The garden space should serve as a framework for various teaching activities: classroom teaching; station-based learning; group work; 1:1 conversations; individual immersion; subject-specific teaching activities. | Spaces of various sizes and subject-specific layers are placed to create synergy rather than conflict between the spaces/layers. | 13 |  |

| A main path system connects the larger spaces. A secondary path system connects the smaller spaces for individual immersion. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stigsdotter, U.K.; Lottrup, L. Designing for Health and Learning: Lessons Learned from a Case Study of the Evidence-Based Health Design Process for a Rooftop Garden at a Danish Social and Healthcare School. Buildings 2026, 16, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020393

Stigsdotter UK, Lottrup L. Designing for Health and Learning: Lessons Learned from a Case Study of the Evidence-Based Health Design Process for a Rooftop Garden at a Danish Social and Healthcare School. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020393

Chicago/Turabian StyleStigsdotter, Ulrika K., and Lene Lottrup. 2026. "Designing for Health and Learning: Lessons Learned from a Case Study of the Evidence-Based Health Design Process for a Rooftop Garden at a Danish Social and Healthcare School" Buildings 16, no. 2: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020393

APA StyleStigsdotter, U. K., & Lottrup, L. (2026). Designing for Health and Learning: Lessons Learned from a Case Study of the Evidence-Based Health Design Process for a Rooftop Garden at a Danish Social and Healthcare School. Buildings, 16(2), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020393