1. Introduction

The modern construction sector is a major energy consumer and a significant contributor to carbon emissions, leading to environmental issues, such as the greenhouse effect [

1]. Governments worldwide are implementing policies to promote energy-saving measures in large-scale constructions to address these concerns. For instance, China aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, prompting specific policies to control energy consumption and emissions across all future projects [

2]. Global attention is shifting towards energy-aware scheduling and green manufacturing. This is particularly critical in the construction sector, which involves a complex, distributed supply chain of off-site component production and on-site assembly. Improving energy efficiency is essential for sustainable development [

3,

4]. The rapidly evolving business landscape, driven by stringent energy conservation policies, compels construction firms to adopt energy-efficient project-centric structures, particularly in modern construction projects.

In addition to energy efficiency, firms are under increasing pressure to reduce project construction costs and improve delivery times. Planning and scheduling are essential for projects that involve assigning start or finish times to tasks under various constraints [

5]. In real life, project managers face tremendous pressure to complete a project with limited resources. Only considering precedence constraints and activity duration is an irrational assumption, as projects require resources ranging from budget to human resources and raw materials to equipment [

6]. Therefore, integrating resource constraints into project scheduling yields resource-constrained project scheduling (RCPS) problems [

7]. In contrast to fundamental RCPS problems, which typically assume a single project and a single execution mode, over 90% of industrial projects are managed concurrently within multi-project environments [

8,

9]. The concurrent execution of multiple projects can significantly influence a firm’s efficiency, offering advantages such as reduced project durations, enhanced resource allocation, and lower management expenses, but it also increases scheduling complexity [

10,

11]. In a multi-project environment, multiple projects must compete to capture available resources. Furthermore, activities can often be executed in a variety of modes, each with specific resource requirements and differing durations [

12]. Integrating multi-project execution and execution mode selection within the RCPSP framework defines the multi-mode resource constraint multi-project scheduling (MRCMPS) problem [

13].

Consequently, to remain competitive in the rapidly evolving business landscape, construction firms are now forced to operate within a complex, multi-mode, resource-constrained, multi-project scheduling problem characterized by dynamic project arrivals and multiple resource constraints, including global renewable, local renewable, and non-renewable resource capacities. This demanding environment pressures managers to simultaneously optimize the conflicting objectives of minimizing total project duration and total energy consumption. Determining the optimal schedule under these circumstances presents a substantial challenge for managers. Therefore, advanced energy-saving techniques are urgently needed to reduce energy consumption and emissions in the construction industry and to achieve sustainable development.

To overcome the challenges of integrating complex resource constraints and conflicting energy objectives, this work proposes a novel multi-objective smart raccoon family optimization (SRFO) algorithm. The SRFO is a hybrid evolutionary approach designed to enhance global exploration and local exploitation by integrating a non-dominated sorting mechanism, a dedicated energy-efficient search strategy, and enhanced genetic operators. The core contributions of this study, aimed at addressing the research gap in energy-efficient scheduling for modern construction projects, are summarized as follows:

To develop a comprehensive mathematical model for the MRCMPS that simultaneously optimizes two conflicting criteria: minimizing total project duration and minimizing total energy consumption;

To develop a novel SRFO algorithm, enhanced with non-dominated sorting, an energy-efficient search operator (ESO), and a smart repair procedure (SRP) to ensure efficient exploration and feasible solutions across trade-off objectives;

To rigorously compare the proposed SRFO against established multi-objective metaheuristics (NSGA-III, MOABC, and MOSMO) using comprehensive benchmark problems and a real-world construction case study.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents a literature review and research gap analysis.

Section 3 provides a detailed description of the problem and the mathematical model.

Section 4 features an in-depth presentation of the proposed SRFO.

Section 5 delves into computational experiments and the examination of their results. Finally,

Section 6 and

Section 7 provide discussion, conclusions, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Multi-Mode Resource-Constrained Multi-Project Scheduling

Researchers have developed objective functions and optimization techniques to address this complexity and identify the most efficient project plan and schedule. The foundational MRCMPS problem, which addresses multiple projects competing for various resources and execution modes, has been investigated through several lenses, primarily focusing on time and cost metrics. Tseng et al. [

14] studied MRCMPS problems with renewable and non-renewable resources, while accounting for due dates and resource availability levels. Asta et al. [

8] investigated the MRCMPS problems with global, local renewable, and non-renewable resources, with the main objective being the minimization of project duration, and makespan as a secondary objective for tie-breaking. Besikci et al. [

9] modeled MRCMPS problems as a resource portfolio problem for budgeting, considering only local renewable and non-renewable resources.

Various approaches are used to optimize objective functions in MRCMPS problems. Kucuksayacigil et al. [

15] focused on minimizing makespan and maximizing net present value using NSGA-II. Geiger [

16] developed a variable-neighborhood search-based method to optimize delay and makespan. Ripon et al. [

17] considered a hierarchical optimization approach to minimize project duration. Kannimuthu et al. [

18] proposed a probabilistic global search algorithm to minimize multiple trade-off objectives. Xu et al. [

19] extended the MRCMPS problem to a fuzzy random environment for a large-scale hydropower construction project and considered only renewable and non-renewable resources, with the objectives of optimizing project duration and quality. Song et al. [

20] investigated MRCMPS specifically for modern construction, studying renewable and non-renewable resources to minimize project duration and cost. Javanmard et al. [

21] developed a hybrid algorithm based on GA, PSO, and cuckoo search for the MRCMPS problem, while considering time-of-use energy usage. Silva et al. [

22] proposed an ant colony optimization (ACO) algorithm for the MRCPS problem with the aim of minimizing energy consumption. Ahmeti et al. [

23] investigated the MRCMPSP with renewable and non-renewable constraints and proposed a hybrid constraint programming approach to minimize project delay. Davari et al. [

24] proposed a mixed-integer programming model for MRCMPS problems that considers renewable and non-renewable constraints to minimize the makespan, net present value, and resource consumption.

2.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Approaches

The literature shows that although many studies optimize a single objective, organizations are increasingly interested in finding the optimal solution to two or more conflicting objectives. Various techniques are employed to address multi-objective optimization challenges, including the weighted-sum method, Pareto solutions, and multi-criteria decision-making methods [

25,

26]. Issa and Tu [

27] and Gomez et al. [

28] reviewed multi-objective optimization techniques for the RCMPS problems. Although exact methods give optimal solutions, they consume more computational resources, limiting their use for large and complex problems [

27]. Consequently, metaheuristics such as genetic algorithms (GA) [

29] and artificial bee colony (ABC) [

30] are among the most frequently used methods for solving project scheduling problems. The non-dominated sorting concept is particularly prevalent among researchers in this domain. For instance, NSGA-II has been widely applied. Kucuksayacigil et al. [

31] presented NSGA-II for RCMPS problems with a backward-forward pass procedure. In another research, Kucuksayacigil et al. [

15] developed a hybrid NSGA-II to optimize net present value and makespan simultaneously. Lafmejani et al. [

32] presented NSGA-II for MRCPSP to maximize cost and project duration simultaneously. Tirkolaee et al. [

33] developed the NSGA-II to reduce the net present value while maximizing the project duration. Zheng et al. [

34] recommended an NSGA-II-based algorithm to optimize the makespan and robustness measure for the RCMPSP. Afshar et al. [

35] presented a multi-objective GA for MRCMPS problems. Wang et al. [

36] presented a hybrid GA for a multi-objective RCMPS problem with doubly constrained resources on the critical chain. Besides GA, several researchers investigated the ABC algorithm’s performance on project scheduling problems and proved that the ABC provides better results than the particle swarm optimization algorithm [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Swarm intelligence optimization algorithms mimic collective behavior in nature to efficiently solve complex optimization problems, offering adaptability, scalability, and robustness in dynamic environments [

44]. The raccoon optimization algorithm (ROA) is a recently developed swarm intelligence optimization algorithm developed by Koohi et al. [

45]. The ROA is designed to balance the exploitation and exploration effects to achieve optimal results for continuous problems, based on raccoons’ foraging behavior. Rauf et al. [

46] proposed a raccoon family optimization algorithm (RFOA) for MRCMPSP to improve the performance of basic ROA by introducing a family of raccoons where each member is accountable for the optimal solution. Song et al. [

20] enhanced the RFOA’s performance by integrating niche genetics and solving the bilevel project scheduling problem. While the RFOA is simple and efficient at quickly finding near-optimal solutions, its primary limitation is its tendency to get trapped in local optima. Several researchers emphasize that integrating problem-specific knowledge is critical for enhancing algorithm performance [

47,

48,

49]. Therefore, to overcome the limitations of RFOA, a novel SRFO algorithm is developed. The SRFO integrates modified genetic operators (crossover and mutation), an energy-efficient smart search operator, and a smart repair procedure to augment exploration/exploitation and verify constraint compliance. A non-dominated sorting mechanism is also introduced to enhance the efficiency of solving multi-objective problems.

2.3. Research Gap

A review of the state of the art reveals a substantial focus on traditional project objectives such as completion time, cost, net present value, and quality, within the MRCMPS literature. However, the critical objective of minimizing total energy consumption, a necessity driven by global environmental policies, especially in energy-intensive modern construction, remains significantly underdeveloped. For instance, Song et al. [

20] investigated the MRCMPS for prefabricated buildings, aiming to minimize project duration and cost, but they did not specifically target energy efficiency. Other existing studies, such as those by Silva et al. [

22] and Javanmard et al. [

21], have considered energy consumption, but their models typically do not integrate dynamic project arrivals and often frame the problem as a single-objective optimization problem. The inherent inverse relationship between project duration and energy consumption, where speeding up construction often necessitates greater resource intensity and thus higher energy use, creates a critical conflict that single-objective or cost-focused models cannot effectively resolve.

As shown in

Table 1, the literature, therefore, lacks a dedicated multi-objective optimization framework capable of simultaneously and efficiently balancing the conflicting objectives of minimizing project duration and minimizing energy consumption. The critical research gap addressed by this work is the absence of a robust metaheuristic designed for this highly constrained environment, which is characterized by the following:

Simultaneous minimization of project duration and total energy consumption;

Management of three distinct resource types (global renewable, local renewable, and non-renewable);

Handling dynamic project arrivals and multi-mode execution selection.

Addressing this complex, multi-layered gap requires a robust metaheuristic tailored with problem-specific knowledge, such as the proposed SRFO algorithm. The SRFO is specifically engineered for this bi-objective, constrained problem by integrating a non-dominated sorting mechanism to manage the conflicting time/energy trade-off and by incorporating problem-specific enhancements, such as the ESO and SRP, to efficiently generate and maintain feasible, high-quality solutions amidst strict resource and precedence constraints.

3. Problem Description

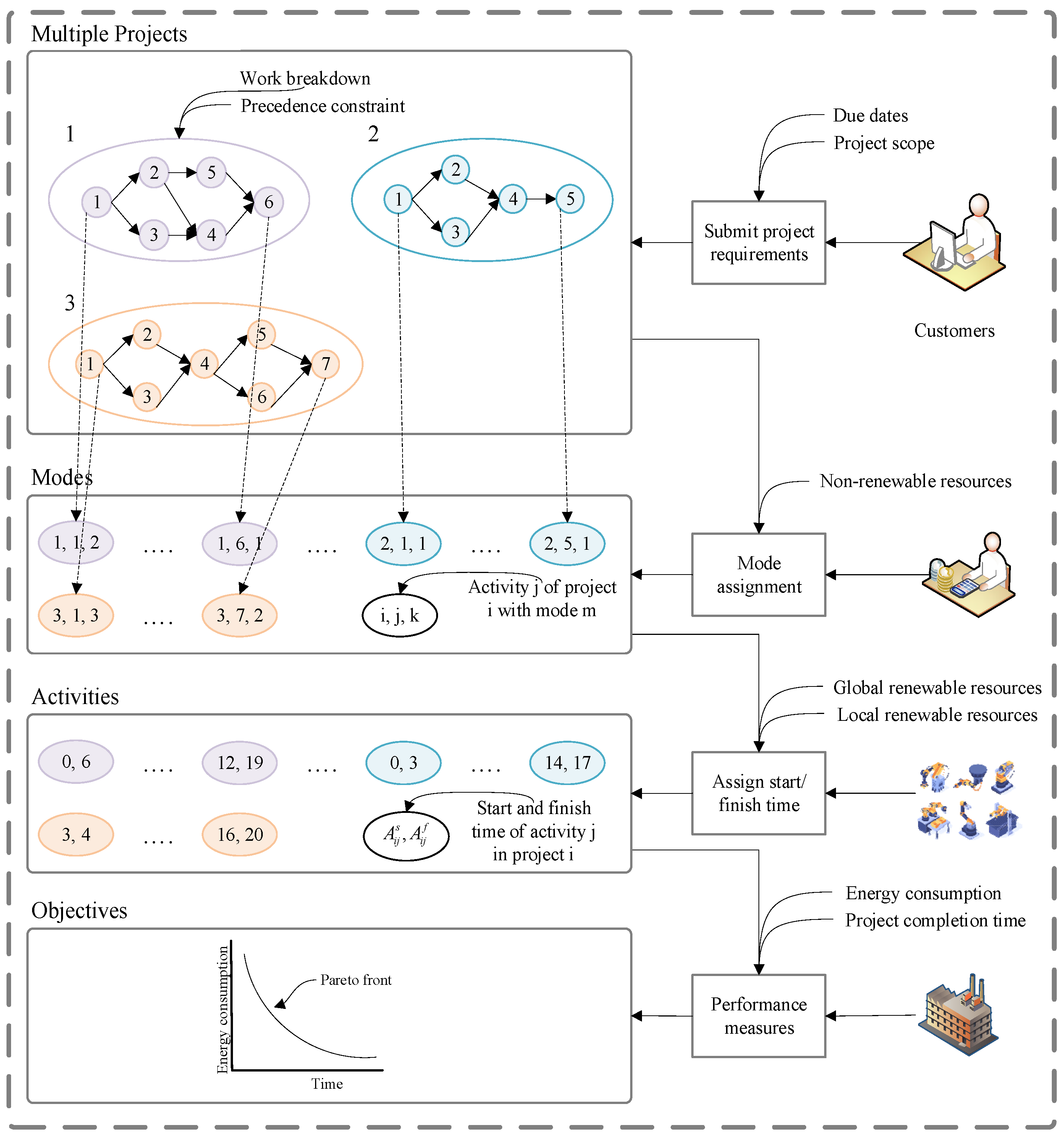

The problem under investigation focuses on modern construction projects, which inherently involve multiple projects and multi-mode activities spanning off-site manufacturing, delivery, and on-site assembly. This integrated process requires the consideration of project activities that can be executed in several modes. The projects are broken down into major parts using a work breakdown structure to divide the project into manageable activities. The precedence relationships among these activities are captured in a project network. Each activity can also be carried out in various ways, each with its own resource requirements and processing times. A visual representation of the concurrent scheduling of multiple projects, incorporating various execution modes and the limitations imposed by resource availability, is presented in

Figure 1. As demonstrated, some concurrently scheduled activities cannot start because of resource constraints, while others must wait for their predecessor activities to finish. The multi-project scheduling problem becomes much more complex because of these factors.

First, projects are selected based on their arrival dates, and each activity is assigned an execution mode according to the non-renewable resources’ availability. Next, start and finish times are allocated to activities based on the resources’ availability and precedence constraints. Two critical performance measures in this context are project completion duration and project energy consumption. These represent conflicting objectives: minimizing one may increase the other, requiring a trade-off. Optimizing the project scheduling problem under these circumstances involves simultaneously minimizing total project completion duration and energy consumption. The complexity of construction scheduling stems from resource constraints, precedence relationships, and the absolute requirement that on-site assembly activities can only begin after the required components arrive on time. The model operates under the assumption that resource capacities, task-specific resource demands, and the durations of activities across different modes are both fixed and deterministic. Additionally, the framework allows for the concurrent execution of various projects, provided that resource limits are respected and individual project release schedules are followed. The notations assumed for the mathematical modeling of the current problem are defined in Abbreviations.

Equations (1) and (2) indicate the objective functions used to minimize the total energy consumption and total project time, respectively. Equation (3) calculates the project’s (i) total energy consumption. Here, represents the total energy consumed by the specific equipment and processes required to complete activity (j) in project (i) using execution mode (m) over its entire duration. Equation (4) is the decision variable with a value of 1 if the activity (j) of the project (i) is executed in the mode (m); otherwise, its value is 0. Equation (5) is a decision variable with a value of 1 if the activity (j) of the project (i) is performed at a time (t); otherwise, it is 0. According to Equation (6), the conclusion of project i is defined by the completion of its final task, representing the maximum finish time among all constituent activities. The precise finish time for an individual task j within project i is determined using Equation (7). Equation (8) enforces the non-renewable resource constraint, mandating that the cumulative use of resource k stays within the total permissible budget. The availability of shared global renewable resources at any specific time t is protected by Equation (9), preventing over-allocation across the project portfolio. Similarly, Equation (10) restricts the usage of site-specific local renewable resources to ensure they do not exceed project-dependent capacities at time t. Equation (11) stipulates that a single execution mode must be selected for each activity, and this selection remains fixed throughout the task’s duration. The temporal baseline is established by Equation (12), which sets the start of the primary project to zero. Equation (13) ensures that no project commences prior to its designated release time. Structural logic is maintained by Equation (14), which prevents a successor activity j′ from starting until its predecessor j has concluded. Finally, Equation (15) guarantees that each activity j is assigned to the schedule exactly once.

The mathematical model developed in this section precisely captures the complex constraints inherent in energy-efficient modern construction projects, including precedence relationships, multi-mode execution selection, and simultaneous consumption constraints for three distinct resource types (local renewable, global renewable, and non-renewable). Given the NP-hard nature of the MRCMPS problem and the bi-objective nature of minimizing both time and energy, an exact solution method is computationally infeasible for large instances. The following section introduces the proposed metaheuristic optimization approach, the SRFO algorithm, specifically designed to navigate this combinatorial challenge and generate high-quality Pareto-optimal solutions efficiently.

4. Proposed Optimization Approach

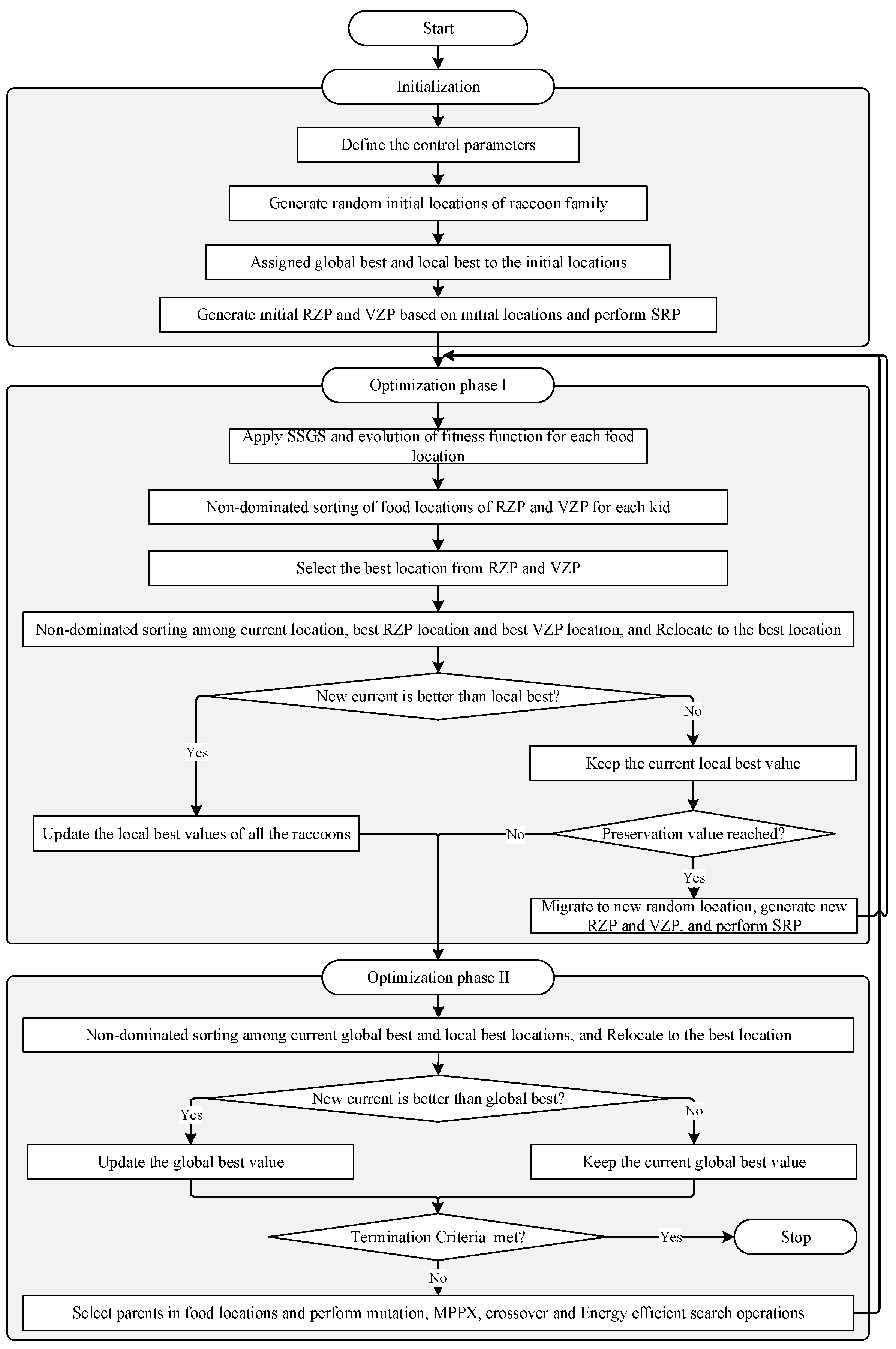

This section provides a detailed description of the proposed SRFO algorithm for solving the resource-constrained multi-project scheduling problem with various execution modes and project arrivals. The foraging behavior of raccoons inspires the standard RFO algorithm. Unlike traditional evolutionary algorithms such as GAs, the RFO algorithm comprises several subgroups, endowing it with multi-group collaborative optimization. The original RFO algorithm is designed for single-objective optimization problems. However, the current problem falls into discrete multi-objective optimization problems. Therefore, the Pareto concept, smart repair procedure (SRP), energy-efficient local search, and crossover operation are incorporated into the original RFO algorithm. The structure of the proposed SRFO is organized into three distinct stages: the initialization phase, global optimization, and local optimization. A detailed visual guide to this multi-objective framework is provided in the flowchart presented in

Figure 2.

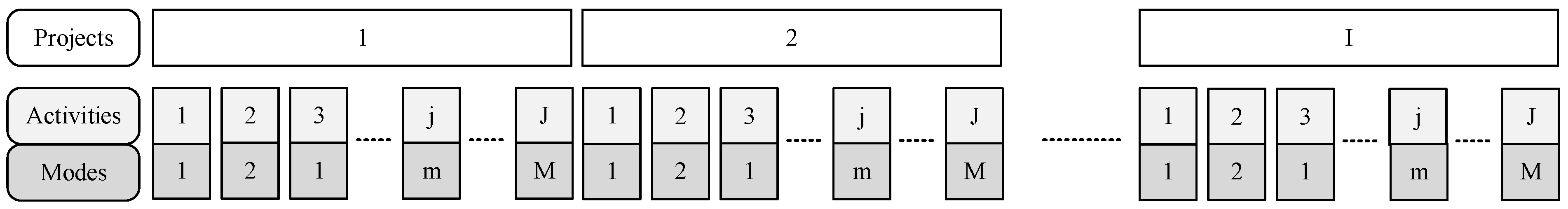

Given the nature of the current multi-project scheduling challenge, the problem is defined within a discrete optimization framework. Because the environment involves distinct variables such as project selection, activities ordering, and mode assignment, the SRFO utilizes a specific food representation to navigate this discrete solution space. The current multi-project scheduling problem is discrete and includes multiple trade-off objectives. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the search space is mapped through a specific food location encoding scheme. This representation is composed of three distinct vectors that sequentially define the sequence of projects, the order of activities, and the assigned execution modes. The serial schedule generation scheme (SSGS) is employed for decoding purposes, as proposed by Asta et al. [

8]. The SSGS translates the precedence-feasible task sequence (

) and the selected mode vector (M) into a concrete schedule by following a stage-by-stage allocation logic while dynamically managing the renewable resource constraints. At each stage

, the algorithm selects the next activity from the sequence

and determines its earliest possible start time (

such that:

The activity starts only after all its predecessor activities have finished;

The required units of global and local renewable resources () for the selected mode are available for the entire duration of the activity without exceeding the total global and local renewable resource capacities ( and

If a resource conflict occurs (i.e., the demand exceeds the available capacity), the activity is delayed to the earliest time slot where the resource requirements can be satisfied. This ensures that the generated schedule is not only theoretically optimal in terms of time and energy but also practically executable within the fixed resource limits of the construction site.

4.1. Initialization

The first stage of the proposed SRFO is the initialization phase. The initialization phase is divided into four steps: define parameters, generate initial location, assign global and local best, and generate population.

Step 1: The process commences with the specification of all necessary algorithmic control parameters.

Step 2: The initial positions of the raccoon family are established by distributing them randomly across the feasible solution space. This preliminary setup is designated as the zero-th iteration of the search process.

Step 3: In the third step, the mother raccoon and the kids’ current random locations are set to global and local optimum, respectively.

Step 4: During the final initialization phase, the starting population is established. The algorithm uses reachable zone populations (RZP) and visible zone populations (VZP). Because the multi-project scheduling environment is discrete and governed by complex resource and precedence dependencies, some candidate food locations in this initial set may not initially be feasible. Therefore, a novel SRP is developed to check the food location’s feasibility and repair it. The steps to implement SRP are presented in the pseudo-code Algorithm 1 below.

| Algorithm 1: Steps of Smart Repair Procedure (SRP) |

![Buildings 16 00392 i001 Buildings 16 00392 i001]() |

4.2. Optimization Phase I

The most crucial parts of this algorithm are the optimization phases. These optimization stages are executed systematically throughout every evolutionary cycle, denoted as . The first optimization phase is known as the local optimization phase. The local optimization phase involves three sequential procedures: assessing solution fitness alongside non-dominated sorting, moving the raccoon toward the optimal position, and initiating the migration process.

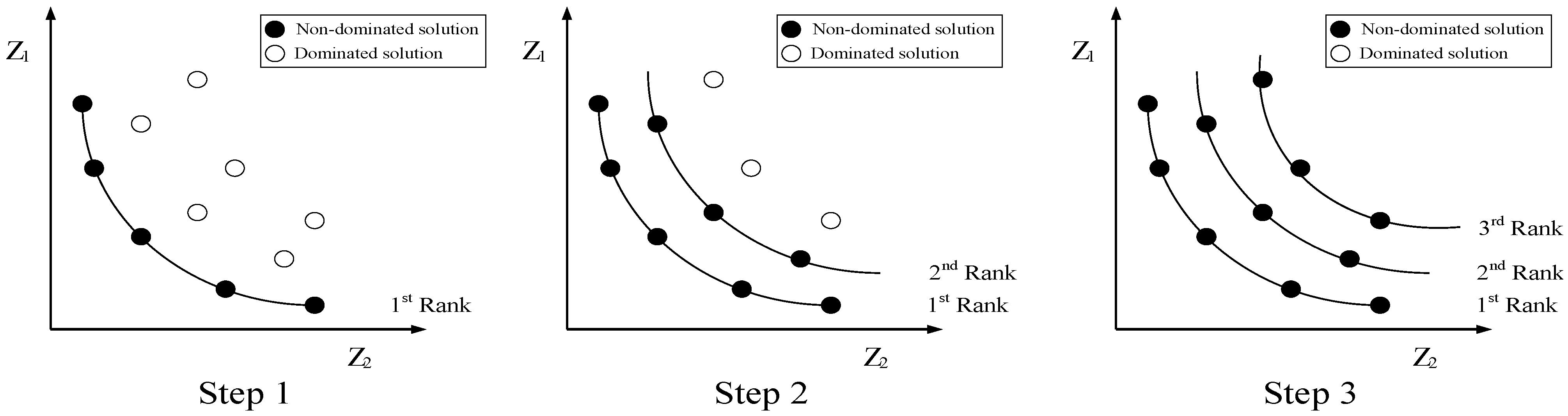

Step 1: The initial step involves assessing the fitness values for every potential food location, which represent the set of candidate solutions. Each food location consists of two different types of foods due to the current problem’s bi-objective nature. Therefore, each kid’s non-dominated sorting of RZP and VZP food locations is performed. This sorting divides food locations into various fronts comprising non-dominated solutions. The Pareto front, which is ranked first, is considered the best front, and the food locations in the first-ranked Pareto front are considered the best. The step-by-step sorting process for food locations is given in

Figure 4. Here, the x-axis and y-axis are the two trade-off objectives (completion time, TEC).

Step 2: The algorithm identifies the top-tier Pareto front by evaluating the fitness of the current position, the highest-performing value within the RZP (), and the leading value from VZP (). Based on this evaluation, the kid raccoon transitions toward the most favorable positions within the primary Pareto front. Following this shift, a new round of non-dominated sorting is conducted between the updated current coordinates and the existing local optimum . The resulting premier Pareto front is archived and designated as the new local optimum . To prepare for the global optimization stage, the kid raccoons transmit their revised current locations and local optima to the group leader.

Step 3: To mitigate the risk of stalling at local optima and to circumvent premature convergence, the group leader’s decision-making process is guided by a preservation parameter and a migration factor (). Initially, is assigned a value of zero. If a raccoon’s location remains stagnant, this counter increments by one; conversely, any change in position resets back to zero. Once the stagnation counter reaches the threshold defined by the MF, the group leader mandates a migration phase. During migration, the kid raccoon is displaced from its current search area and relocated to a randomized position entirely outside its previous RZP and VZP zones. Following the successful relocation of the raccoon, the counter is reset to zero to restart the monitoring process.

4.3. Optimization Phase II

During the global optimization stage, the group leader aggregates data regarding the most favorable local food positions identified by the kids to refine its own coordinates. This step, which constitutes the second optimization phase, focuses on leveraging the collective search efforts to improve the overall global position. This phase consists of three significant steps: relocation to the global optimum location, termination criteria check, and population generation.

Step 1: The group leader assesses her existing position against the local optimal coordinates identified by the kids through non-dominated sorting and the subsequent ranking of Pareto fronts. The leader then transitions to a new location corresponding to a position on the top-ranked Pareto front. Following this movement, a secondary non-dominated sorting is executed, comparing the new current position with the existing global optimum . The resulting first-ranked Pareto front from this comparison is then designated as the updated global optimum value .

Step 2: In this step, the termination criteria are checked. If the termination criteria are met, the algorithm terminates; otherwise, a new population is generated.

Step 3: At this step, a new population is generated. To expand the search within the reachable (RZP) and visible (VZP) zones, genetic mechanisms, specifically crossover and mutation, are utilized to produce additional candidate solutions, as depicted in

Figure 5. Moreover, a novel energy-efficient search operator (ESO) has been developed to minimize energy consumption. To enhance the search process, genetic operators are utilized to broaden the local exploration area, whereas the ESO is designed for rapid identification of optimal solutions. Given that the problem structure is organized into three distinct tiers, encompassing projects, activities, and execution modes, these search mechanisms are executed across multiple levels. Specifically, the ESO is implemented at the third level, focusing on mode assignment to allocate both renewable and non-renewable resources to various project tasks. Further, the modified precedence-preserving crossover (MPPX) and swap mutation genetic operators are applied to activities and multiple projects to generate the following food locations. The steps for the ESO are given below in pseudo-code Algorithm 2. The coordinated local and global search procedures are executed iteratively for a total of NI cycles, continuing until the predefined stopping conditions are satisfied. This repetitive cycle ensures that the algorithm thoroughly explores the solution space and refines candidate schedules through successive generations. The hybrid design of the SRFO, which integrates non-dominated sorting with problem-specific knowledge (such as the ESO and SRP), provides a robust and efficient mechanism for exploring the solution space and exploiting high-quality, energy-efficient schedules. The computational performance and superior efficacy of the proposed SRFO algorithm, along with a detailed comparison against established metaheuristics, are validated through extensive experimentation in the subsequent section.

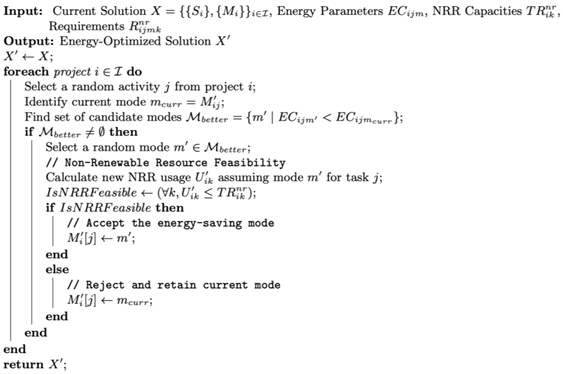

| Algorithm 2: Steps for Energy-efficient Search Operator (ESO) |

![Buildings 16 00392 i002 Buildings 16 00392 i002]() |

5. Computational Experiments and Results

In this section, we outline the experimental setup and the application of the Taguchi method for optimizing the parameters of the SRFO, NSGA-III [

34], MOABC [

50], and MOSMO [

1] algorithms. Performance evaluation is conducted using adapted MISTA [

51] benchmark problems. These benchmarks were constructed by merging single-project data from the J10, J20, and J30 PSPLIB sets to form multi-mode, multi-project networks. Specifically, the computational experiments used four instances for each of the three size categories (small, medium, and large), yielding a total of 12 benchmark problems for comprehensive validation. To address the absence of energy-related data in the original benchmarks, we adopted the data assignment approach established by Yue et al. [

1]. Additional model parameters were generated using a uniform distribution within a specified range

. Finally, the effectiveness of the SRFO is benchmarked against the aforementioned algorithms using a comprehensive suite of metrics covering convergence, solution distribution, and multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM).

5.1. Parameter Tuning

Appropriate parameter selection significantly affects the performance of algorithms. The performance of metaheuristic algorithms is highly sensitive to their parameter settings. Consequently, precise selection and calibration are required to achieve optimal outcomes for specific problem instances. To analyze the influence of five key SRFO parameters, specifically the number of kids (k), the migration factor (f), the mutation rate (m), the crossover rate (c), and the greedy search operator (g), this study employs the Taguchi method in conjunction with orthogonal arrays. Each of these five parameters was evaluated across three distinct levels [

,

,

,

,

]. Given this configuration, an L27 (35) orthogonal array was implemented, necessitating a total of 27 experimental trials per test case. To ensure data reliability, each trial was executed ten times, with the results for both objective functions

meticulously documented. The variation in experimental responses was analyzed by converting raw data into signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios. Although S/N ratios are generally categorized into three types, namely, “nominal-is-best,” “larger-the-better,” and “smaller-the-better”. The “smaller-the-better” criterion was adopted here. This selection aligns with the minimization nature of our objective functions and established literature in the field [

52].

For the design of the experiment and Taguchi analysis, a MINITAB

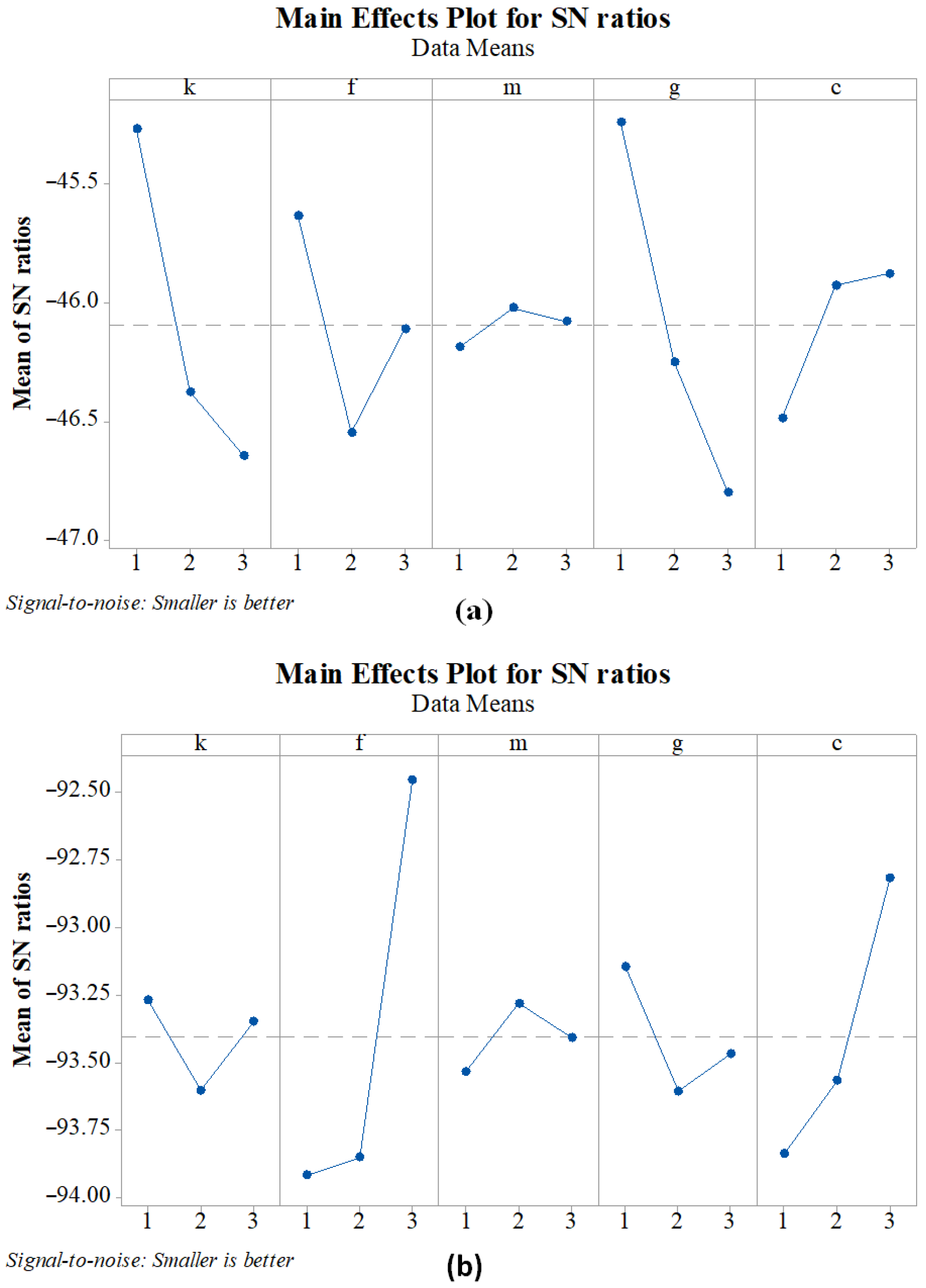

TM 18 is used. A visual observation-based method is used to identify the effects of parameter of algorithms. S/N ratios for both objective functions are given in

Figure 6, which shows the impact of the objective functions’ parameters. It can be seen from

Figure 6 that the number of kids (k) and greedy search operator (g) performed best at level 1, mutation (m) at level 2, and crossover (c) at level 3 for both objectives. However, that is not the case for the migration factor (f). The migration factor (f) performed best at level 1 and worst at level 2 for the first objective, while it performed worst at level 1 and best at level 3 for the second objective. Since the migration factor (f) performed best for the second objective and medium for the first objective at level 3, level 3 is selected. For a fair comparison, the parameters of the other compared algorithms are also fine-tuned using the Taguchi method. The parameters’ combination of algorithms is given in

Table 2.

5.2. Analysis of Results

In this phase of the study, the benchmark instances previously described are processed using the proposed SRFO, along with MOABC, NSGA-III, and MOSMO. The primary objective is to evaluate and contrast the computational effectiveness of the SRFO against these established metaheuristic frameworks. The literature shows that several algorithms are effective for solving project scheduling problems. However, the performance of the proposed SRFO algorithm is compared with that of the MOSMO, NGGA-III, and MOABC algorithms. As mentioned above, the proposed SRFO and other algorithms are implemented in MATLABTM R2020b and run on a system with a Core i7-10710U processor at 1.10 GHz and 16.00 GB of memory. For a fair comparison, the parameters of all algorithms are also fine-tuned using the Taguchi method. Each algorithm is run independently, with its encoding and decoding, initial population, constraints, and fitness function kept identical to avoid their effects on the algorithms’ performance. All algorithms are run 10 times per case to obtain reliable data, and the mean value across runs is recorded.

It is essential to compare the performance of one algorithm with that of the others using performance indicators. In a multi-objective optimization problem, we have to deal with multiple conflicting objectives, whereas in single-objective optimization problems, we care only about minimizing or maximizing one objective. Therefore, comparing the performance of algorithms in multi-objective optimization problems is not straightforward and requires additional steps. For this purpose, various researchers have suggested different performance indicators/metrics. These metrics can be classified as convergence and distribution metrics [

53]. Besides these metrics, the researchers have also used the technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS), a multi-criteria decision-making technique (MCDM) to compare algorithms’ performance on multi-objective optimization problems [

26]. Most researchers have used two or more performance metrics to compare algorithms’ performance on multi-objective optimization problems. Therefore, to make a fair and comprehensive comparison, convergence, distribution, and one MCDM metric (TOPSIS) are selected as performance indicators to compare the algorithm’s performance for multi-objective optimization problems.

5.2.1. Comparison Based on Objective Functions and Computational Time

Table 3 presents a comparison of the proposed SRFO algorithm with competitors (MOABC, NSGA-III, and MOSMO) based on raw objective function values and computational efficiency across small, medium, and large problem instances. The values reported for project completion time and TEC are the mean and standard deviation (Std) obtained from 10 independent runs on each instance. Since both objectives are minimization objectives, the lower values are better.

The results in

Table 3 demonstrate that SRFO consistently achieves the best trade-off, recording the lowest mean values for both Time and TEC across all three problem sizes. For the large-scale problem, SRFO achieves a mean duration of 228.25 days and a TEC of 29,392.50, significantly outperforming the next-closest competitor. Furthermore, the standard deviation (Std) values for SRFO’s objective functions are consistently lower than those of the competing algorithms, especially for the larger instances. This indicates that SRFO exhibits superior robustness and stability, consistently generating high-quality solutions with less variability than the general-purpose metaheuristics.

The table also reports the mean and standard deviation of CPU Time (seconds), addressing computational feasibility. In the medium instance, the SRFO runs in an average of 59.24 s, demonstrating that, while MOSMO is marginally faster (55.84 s), the computational effort of SRFO remains highly competitive, especially given its verified superiority in solution quality and stability. This efficiency is critical for its practical application as a decision-support tool.

5.2.2. Comparison Based on Convergence Metrics

Convergence metrics relate to the quality and number of solutions an algorithm produces; the closer the solutions are to the true Pareto front, the better the algorithm. In convergence metrics, researchers have used the quality metric (QM) [

32,

50], the inverted generational distance (IGD) [

50,

53,

54,

55], and a number of Pareto solutions (NPS) [

32,

53]. The performance of the proposed SRFO is compared with that of MOABC and NSGA-III based on QM, IGD, and NPS. A smaller IGD value indicates better convergence toward the true Pareto front, a higher NPS indicates a greater number of non-dominated solutions discovered, and a higher QM score indicates a higher percentage of solutions that remain non-dominated when compared against the sets of all other competing algorithms. A comparison of algorithms based on these performance indicators is given in

Table 4.

Table 4 shows that the proposed SRFO provides better results, with the lowest IGD and the highest NPS and QM values across all instances.

5.2.3. Comparison Based on Distribution and MCDM Metrics

The distribution metrics measure the evenness of solutions’ distribution; the more even it is, the better the trade-offs between conflicting objectives are. In distribution metrics, researchers have used the spacing metric (SM) [

33,

52,

53,

56] and the diversity metric (DM) [

32,

33,

53]. The smaller the SM value, the better the distribution, while a larger DM value means the algorithm’s solutions cover a larger solution space. A comparison of algorithms based on these performance indicators is given in

Table 5. From the average SM and DM values, the solution obtained from the proposed SRFO shows a better distribution across all test cases than those of other algorithms.

The technique for order of preference by similarity to an ideal solution (TOPSIS) is an MCDM method. It is commonly used to select the best alternative based on different trade-off criteria. However, it can be adapted to compare the performance of different algorithms for multi-objective optimization problems due to its high flexibility and simplicity. The steps for performing the TOPSIS are adopted from Rauf et al. [

26]. The proposed SRFO is compared with the NSGA-III, MOABC, and MOSMO algorithms using TOPSIS’s steps, and the results are shown in

Table 5. The average value shows that the proposed SRFO achieves a better trade-off between objectives than other algorithms.

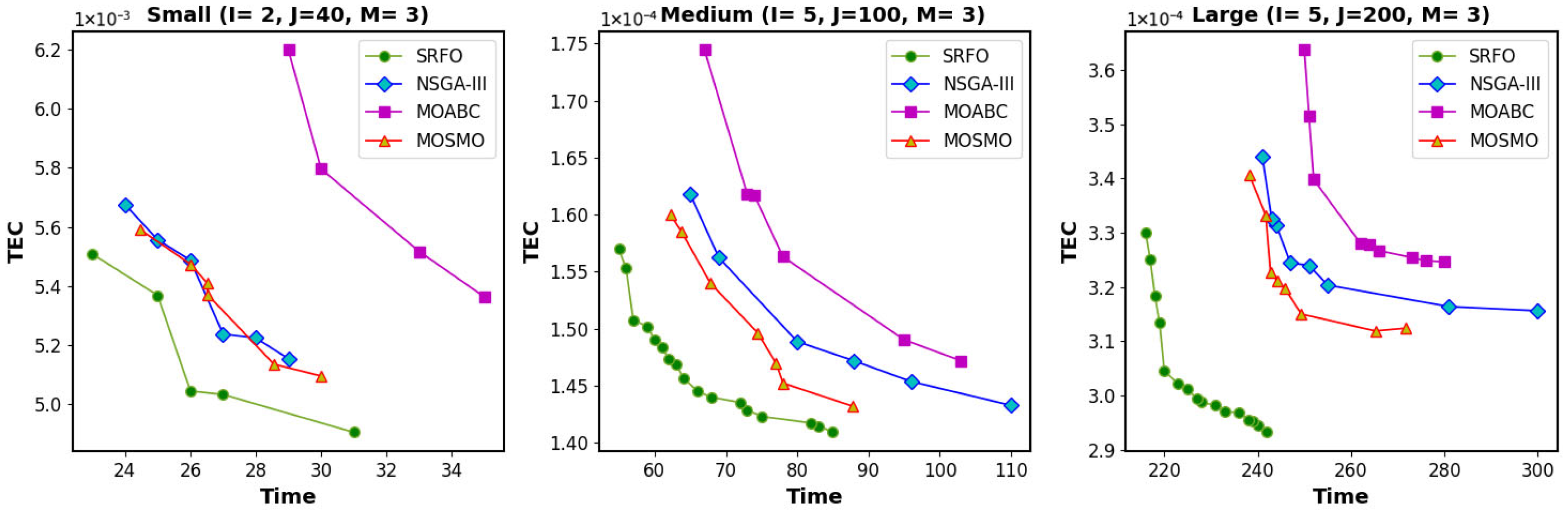

5.2.4. Pareto Fronts (PFs)

The proposed SRFO’s performance is compared with NSGA-III, MOABC, and MOSMO on Pareto front-based comparisons. Pareto fronts obtained by these algorithms for small-, medium-, and large-size problems are illustrated in

Figure 7. Since both objectives (time and cost) need to be minimized, a Pareto front closer to the origin is better. As shown in

Figure 7, the Pareto fronts obtained by the proposed SRFO are closer to the origin. The proposed SRFO leverages ESO, genetic operators, and non-dominated sorting mechanisms to enhance exploration and exploitation. Further, the addition of SRP in the proposed SRFO increases efficiency. Therefore, it can be concluded that the proposed SRFO outperformed the other algorithms based on the Pareto fronts.

5.2.5. Statistical Analysis

To rigorously validate the observed performance differences in the mean values, a nonparametric statistical analysis was conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. This test is appropriate for comparing the performance of two related algorithms across multiple problem instances. The test assesses whether the differences between the paired observations (SRFO vs. Competitor) come from a distribution with a non-zero median. The threshold for statistical significance was set at .

The Wilcoxon test was performed pairwise, comparing the ranks of the proposed SRFO algorithm against its three competitors: MOABC, NSGA-III, and MOSMO. The results, summarized in

Table 6, confirm the robust superiority of SRFO across most of the critical convergence and multi-criteria decision-making metrics. For the key metrics IGD and QM, the SRFO consistently ranked first in all pairwise comparisons against MOABC, NSGA-III, and MOSMO. The

p-values for the comparisons against MOSMO and the other algorithms were 0.1250, suggesting the differences are statistically significant at a

confidence level. SRFO ranks highest on every problem for these key metrics, providing strong empirical evidence of its superior convergence capability. Similarly, the SRFO demonstrated superior performance in the TOPSIS metric (

p = 0.1250).

The SRFO also performed favourably against MOSMO in the DM (p = 0.1250) and NPS (p = 0.2500). The differences between SRFO and all competitors were not statistically significant for the SM (p = 0.3750), indicating all algorithms produced solutions with a statistically similar level of distribution uniformity. Overall, the statistical analysis confirms that the enhanced operators within SRFO lead to statistically superior solution convergence and quality compared to the established metaheuristics.

5.3. An Illustrative Example Case Study

Project-based companies must simultaneously execute several projects with limited resources to meet deadlines. In the real world, project managers are pressured to finish a project with limited resources. Budget, human resources, raw materials, and equipment are all examples of these resources. The current project scheduling problem for multiple projects with different release dates and execution modes is based on an advanced planning and scheduling (APS) system for a well-known construction component manufacturing company. This scenario involves scheduling the production and delivery pipeline for four distinct modern construction projects (or major component groups) that compete for shared factory (global) and project-specific (local) resources. The proposed SRFO is used to help the construction component manufacturer formulate a detailed, energy-efficient production and logistics plan, ensuring timely component supply to multiple assembly sites. The goal is to provide the managers with optimum solutions for the trade-off objective.

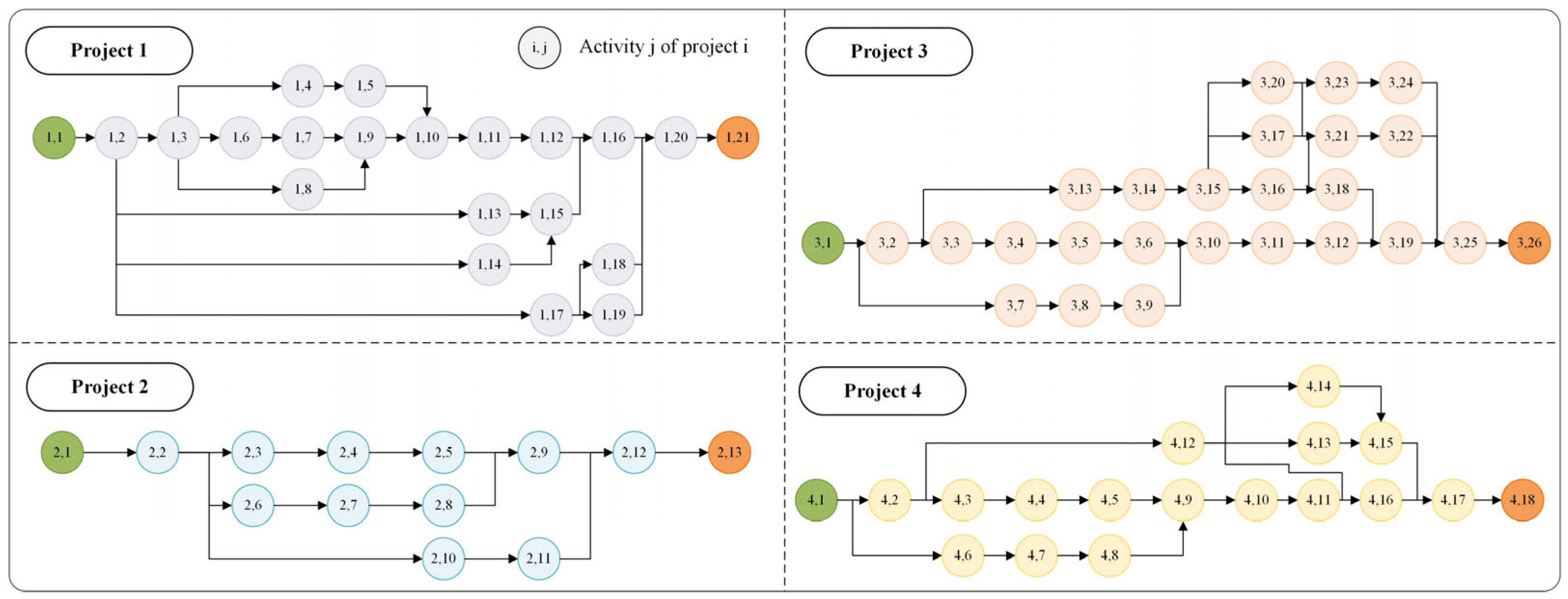

This case study models the complexities of simultaneous scheduling for four distinct modern construction projects (

), which compete for shared factory-level (global) and project-specific (local) resources. The case study is meticulously structured to reflect a high-fidelity construction environment, comprising 78 distinct activities (

j = 78), each of which can be executed via one of three available modes (

). The precedence network is defined by 120 finish-to-start constraints given in

Figure 8. This complex scheduling environment is governed by three distinct resource types: eight categories of global renewable resources, including shared factory equipment and labor teams, with capacities ranging from 1 to 3 units; two project-specific local renewable resources, such as cranes; and two types of non-renewable resources, representing budget and raw material limits. To maintain technical rigor and account for real-world manufacturing variability, the parameter ranges for activity durations (

) and average power consumption rates (

) were derived directly from actual production logs. The available capacities of global, local, and non-renewable resources are given in

Table 7.

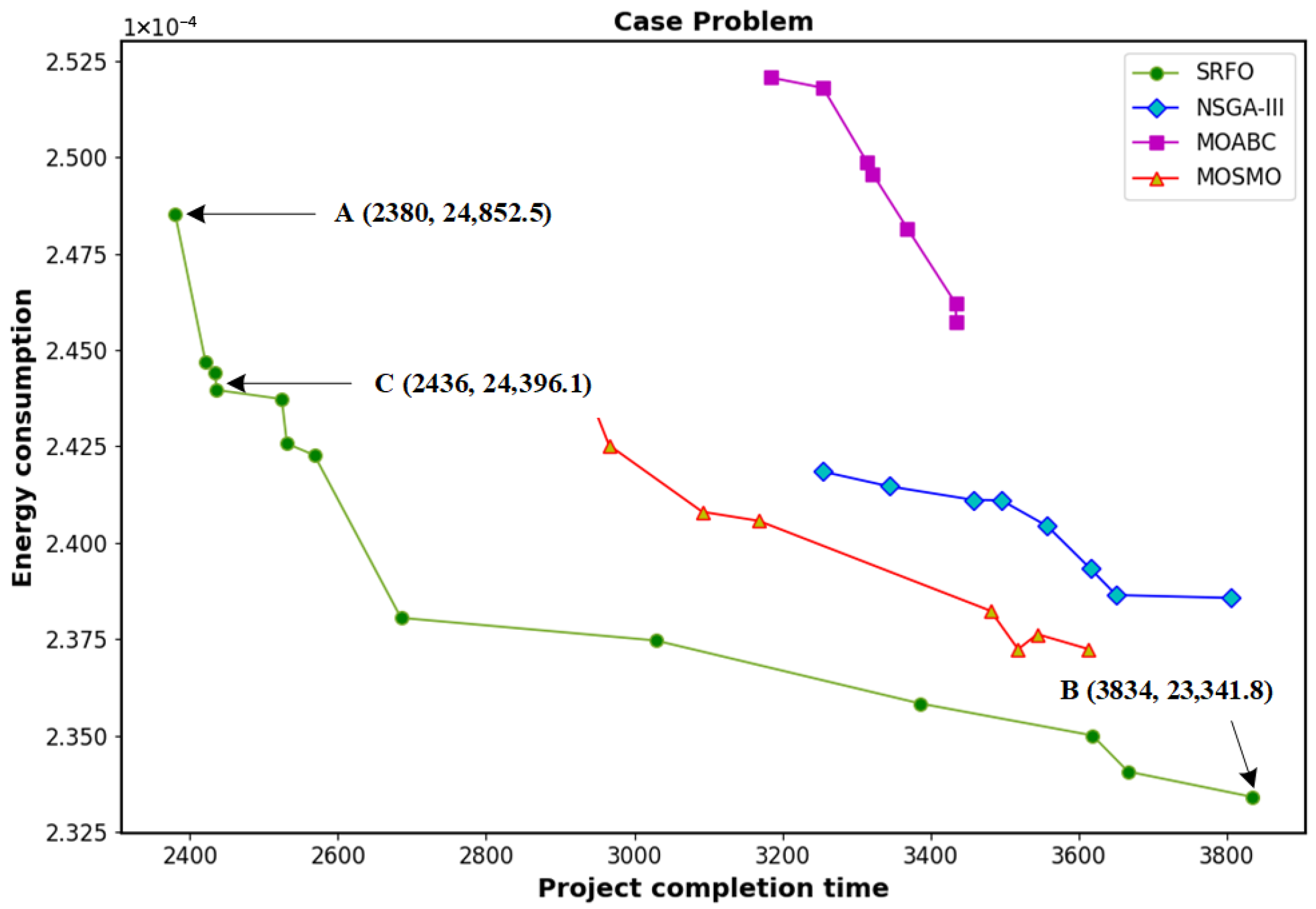

The proposed SRFO is implemented to solve the case problem with the fine-tuned parameters. Pareto points obtained from the proposed SRFO, NSGA-III, MOABC, and MOSMO algorithms are shown in

Figure 9. As shown in

Figure 9, the Pareto front obtained by the proposed SRFO is closer to the origin than those of the other algorithms. The proposed SRFO algorithm facilitates a comprehensive sensitivity analysis by generating a well-distributed Pareto front. This allows project managers to evaluate the “cost” of time in terms of energy, and vice versa. For the current case study, we identified three characteristic selection points (A, B, and C) to represent different managerial priorities. Pareto Point A has a minimum project duration (2380) and maximum energy consumption (24,852.5). In contrast, Point B has the minimum energy consumption (23,341.8) and the maximum project duration (3834). Point C (2436, 24,396.1) is obtained by implementing TOPSIS with equal weights.

To evaluate the performance gain of the proposed SRFO, a baseline schedule was established using the serial schedule generation scheme (SSGS) with a standard earliest-start-time priority rule. This baseline represents a traditional scheduling approach that prioritizes completion time under resource constraints but lacks multi-objective optimization for energy efficiency. As shown in

Table 8, the Baseline Point resulted in a project duration of 2650 days and a total energy consumption (TEC) of 27,140.5 units. The sensitivity analysis provides critical insights into the dynamics between the conflicting objectives. Regarding the sensitivity to time reduction, transitioning from the Baseline Point to Point A (Time-Critical) reduces the total project duration by 10.2%, dropping from 2650 to 2380 days. However, this acceleration necessitates the selection of more resource-intensive execution modes, which is directly reflected in an increase in total energy consumption. When evaluating sensitivity to energy conservation, moving from Point A to the balanced Point C shows that a minor increase in duration of 2.3% yields a significant energy saving of 1.8%. Conversely, achieving the maximum possible energy savings at Point B requires the project duration to extend by 61% compared to the time-critical point, indicating that energy efficiency within this specific project network is highly sensitive to completion speed. Ultimately, the analysis of performance gain over the baseline confirms that the SRFO-Balanced (Point C) is Pareto-superior to the traditional Baseline Point. It simultaneously reduces project duration by 8.1% and energy consumption by 10.1% relative to standard industrial heuristics, validating the technical efficacy of the proposed optimization approach.

The results confirm that the SRFO successfully integrates the construction constraint, where on-site assembly is gated by the arrival of construction components, into an optimized timeline. By utilizing the ESO and SRP, the algorithm produces schedules that are not only theoretically optimal but also practically feasible under strict resource and precedence limitations.

6. Discussion

The experimental results presented in

Section 5 unequivocally demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed SRFO algorithm compared to established multi-objective algorithms, including NSGA-III, MOABC, and MOSMO, across diverse problem sizes and metrics. This superior performance is directly attributed to the specialized components integrated into the SRFO framework, which effectively address the multi-layered constraints of the energy-efficient MRCMPS problem.

Statistical validation through the Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirms that SRFO consistently outperforms its counterparts in key convergence and multi-criteria decision-making metrics. Specifically, the significantly lower IGD values and superior QM and NPS scores confirm that the SRFO population converges faster toward the true Pareto front and identifies a higher density of non-dominated solutions. This enhanced convergence is largely driven by the integration of the non-dominated sorting mechanism, which efficiently manages the trade-off between project duration and energy consumption during the evolutionary process.

Furthermore, the results observed for the SM and DM indicate that SRFO generates solutions that are not only closer to the optimal front but also more uniformly distributed across the feasible space. This uniform distribution is a direct consequence of the enhanced global exploration capability enabled by the RFO base algorithm and the integration of the MPPX and swap mutation genetic operators. Adding the ESO at the mode assignment level ensures the local exploitation phase effectively biases the search toward energy-minimizing modes while maintaining resource feasibility.

The real-world case study and subsequent sensitivity analysis best illustrate the practical relevance of the SRFO. The generated Pareto front provides project managers with a robust decision-support tool by quantifying the trade-offs between duration and energy. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the SRFO-Balanced solution (Point C) is superior to traditional industry heuristics, simultaneously reducing project duration by 8.1% and energy consumption by 10.1% compared to a standard baseline established by standard heuristics. Managers can choose Point A (duration: 2380) for time-critical needs or Point B (TEC: 23,341.8) for maximum energy conservation, while Point C (2436, 24,396.1) offers a balanced compromise. The ability of SRFO to provide high-quality, robust schedules while maintaining competitive computational efficiency confirms its viability for scientific management in energy-constrained construction environments

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This research provides both a practical algorithmic framework and critical insights into sustainable, intelligent construction project scheduling, offering significant implications for industries prioritizing energy efficiency and dynamic resource allocation. We have addressed the complex challenges of MRCMPS, characterized by varying project release dates and multiple resource constraints. By integrating project scheduling with mode assignment, we developed a comprehensive solution framework that effectively balances two conflicting objectives: minimizing total project duration and total energy consumption, which is particularly relevant to low-carbon strategies in the modern construction sector. The inclusion of realistic constraints, such as global, local, and non-renewable resource capacities, alongside mandatory component supply limits, enhances the practical applicability of this approach to modern construction project management. To solve this complex combinatorial optimization problem, we proposed a novel multi-objective SRFO algorithm. The SRFO integrates several advanced features, including a non-dominated sorting mechanism to handle multiple objectives, specialized genetic operators (MPPX and swap mutation) for solution refinement, and a problem-specific ESO for rapid local exploitation. To ensure peak performance, the algorithm’s parameters were meticulously fine-tuned using the Taguchi method.

Extensive experimental validation across both benchmark problems and a real-world case study demonstrated the SRFO’s superior capabilities. The algorithm was rigorously compared against established approaches, including NSGA-III, MOABC, and MOSMO, using a comprehensive set of evaluation metrics. Three convergence metrics (QM, IGD, NPS), two distribution metrics (SM, DM), TOPSIS-based multi-criteria decision-making, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test consistently confirmed the SRFO’s advantages in solution quality, convergence speed, and Pareto front distribution. Specifically, the case study results highlighted the algorithm’s effectiveness, showing that the SRFO-Balanced solution achieved 8.1% reductions in project time and 10.1% in energy consumption compared to traditional industry heuristics. These results underscore the effectiveness of the SRFO in generating high-quality, feasible schedules while respecting complex resource constraints.

From a practical standpoint, this research provides project managers with a robust decision-support tool for scheduling complex project portfolios under stringent energy constraints. Future studies could enhance the model’s practicality by incorporating real-world uncertainties, such as fuzzy activity durations, resource transfer time and cost considerations, and integrating various real-life constraints to develop a hyper-heuristic approach, all of which are key challenges in intelligent construction. These advancements would further strengthen the connection between theoretical optimization and practical project management challenges.