Analysis of Multi-Physics Thermal Response Characteristics of Anchor Rod and Sealant Systems Under Fire Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Coupled FDS–ABAQUS Simulation

- (1)

- Establish an FDS fire model consistent with actual working conditions to simulate the smoke flow and thermal radiation distribution characteristics during the sealant combustion process, focusing on extracting the time-history data of the heat flux on the anchor rod structure’s surface.

- (2)

- Establish a three-dimensional solid ABAQUS model of the anchor rod that corresponds exactly to the geometric dimensions of the FDS model, apply the pre-processed heat flux as a surface load to the model’s surface, and perform transient heat conduction calculations to obtain the detailed temperature field distribution inside the anchor rod and its time evolution.

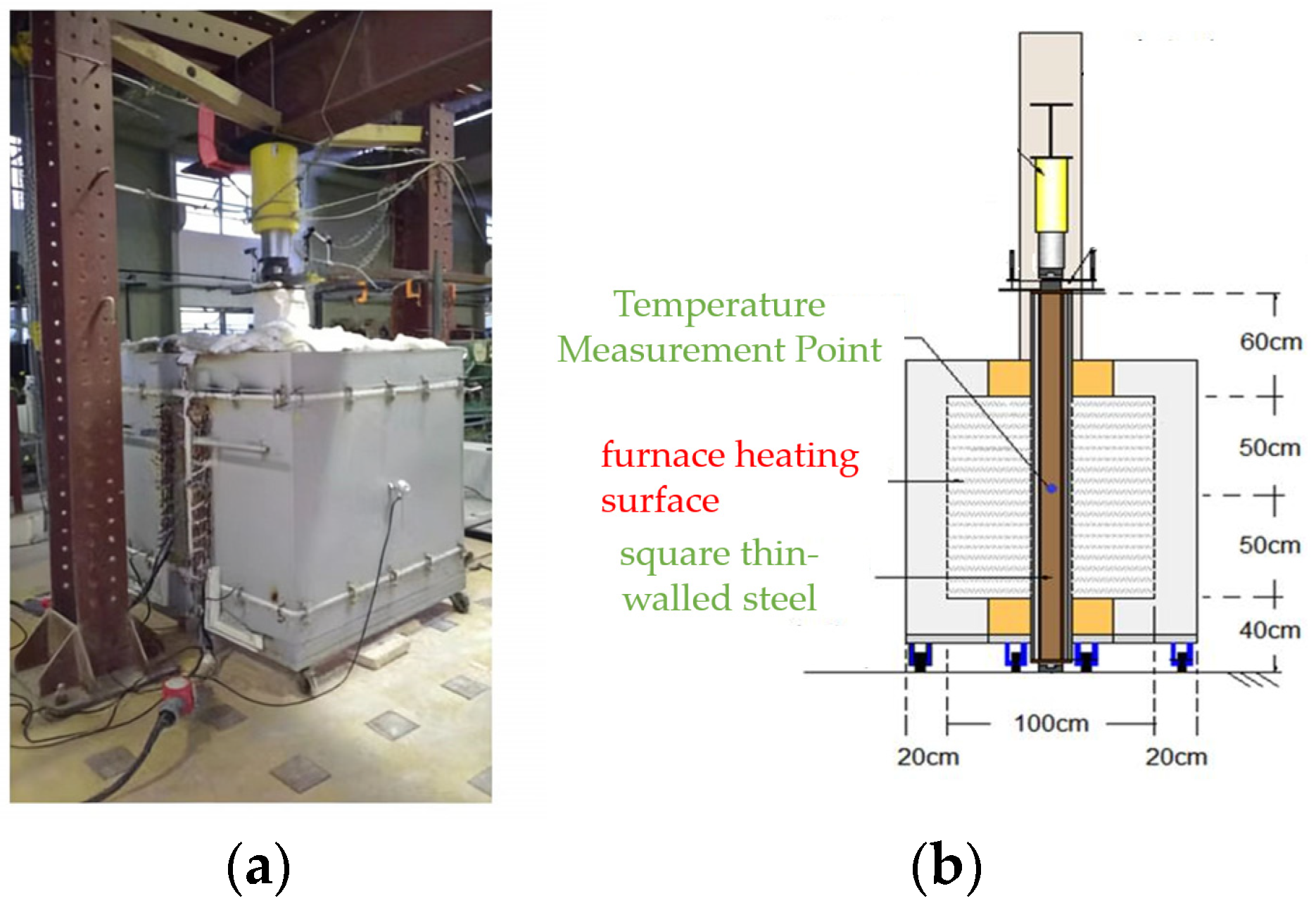

2.2. Validation of the Framework

2.2.1. Experimental Configuration

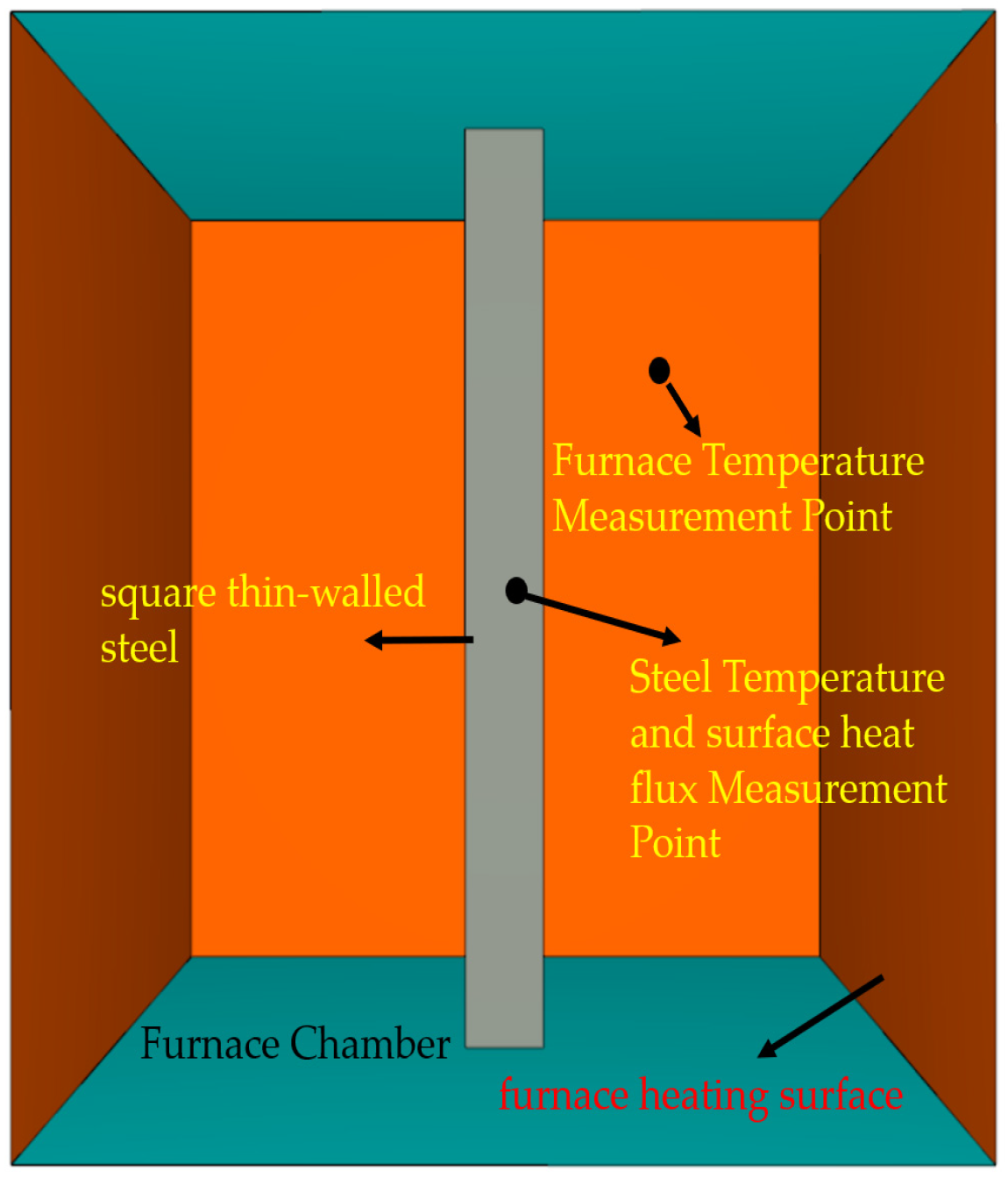

2.2.2. Numerical Modeling

- 1.

- FDS Model for Fire and Thermal Loads

- 2.

- ABAQUS Model for Heat Transfer in Solids

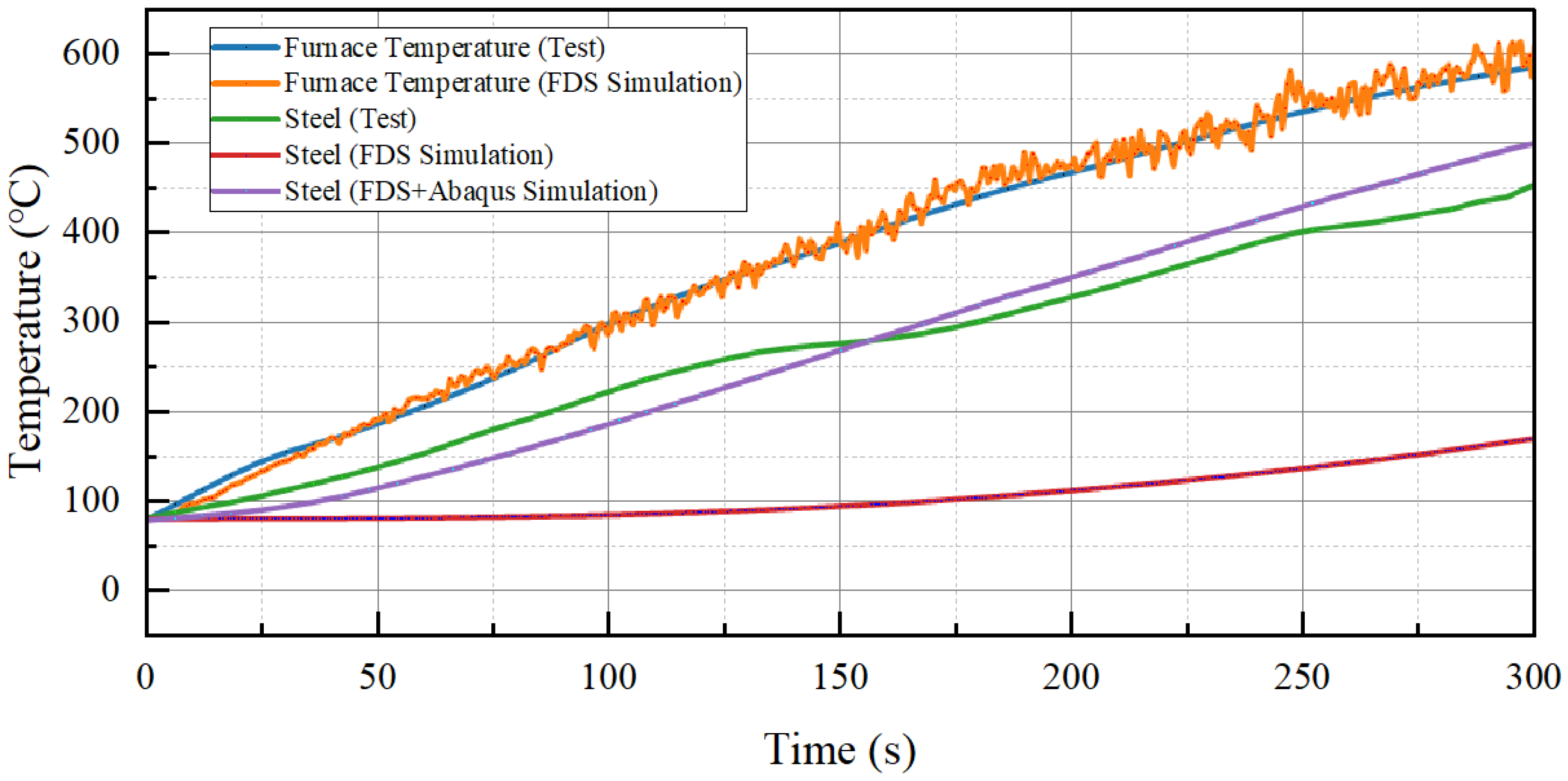

2.2.3. Results and Experimental Validation

- 1.

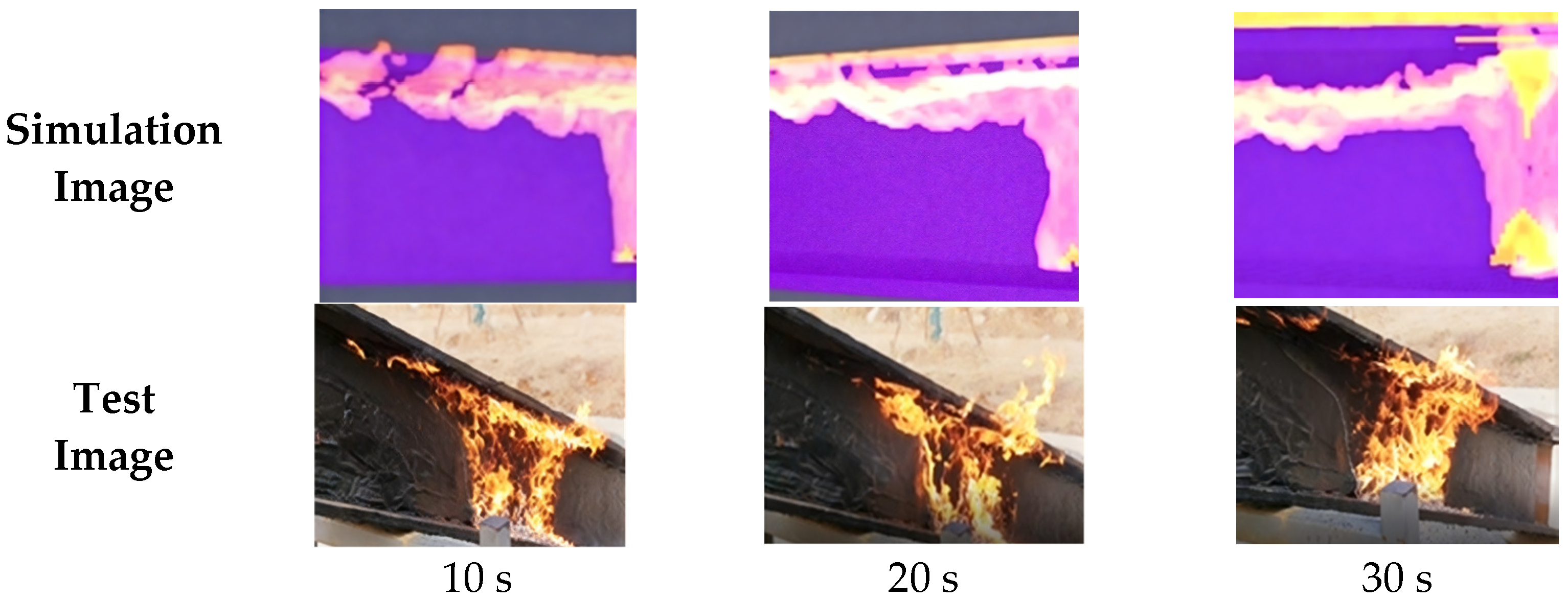

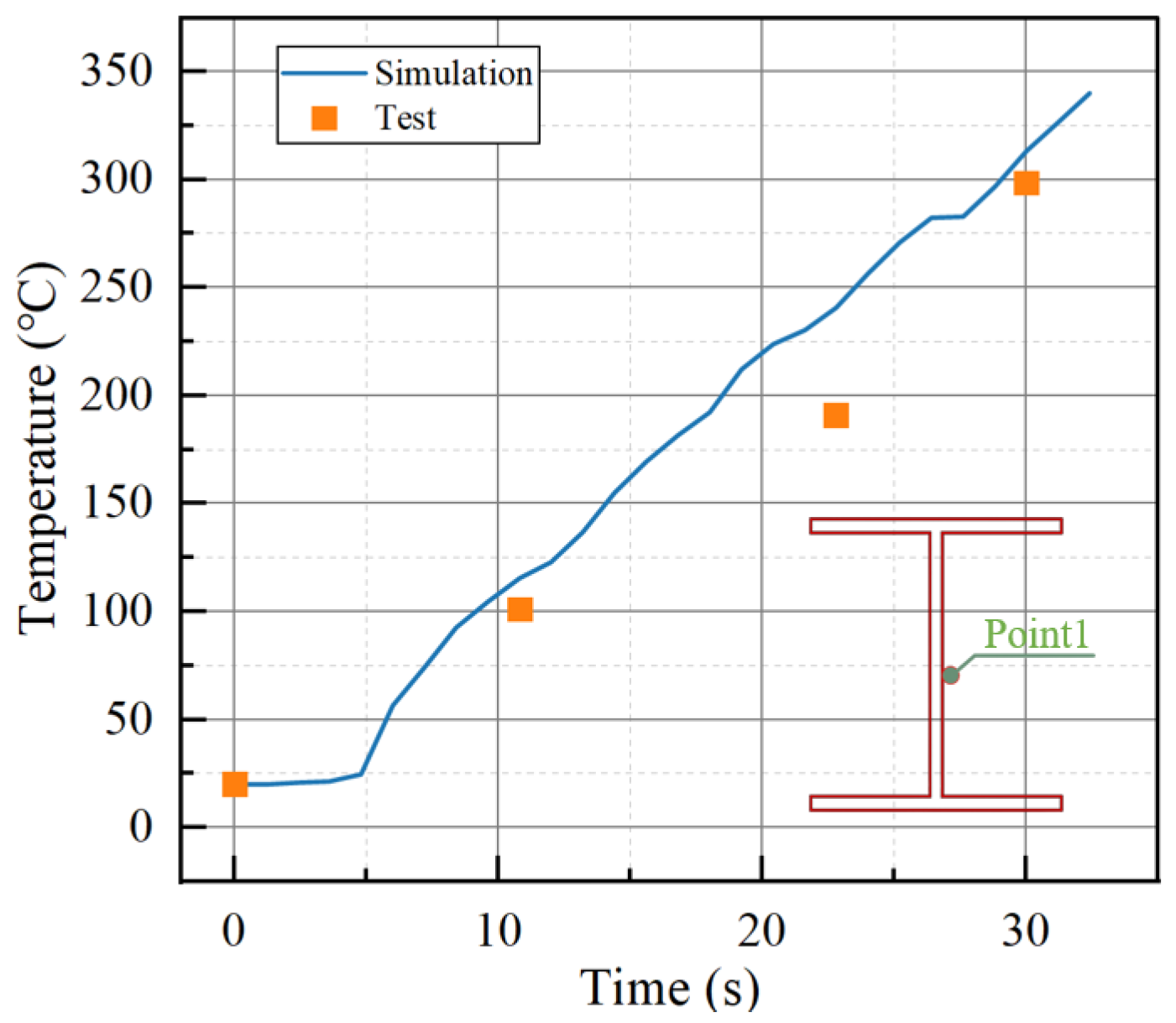

- Accuracy Assessment of the Coupled Strategy

- 2.

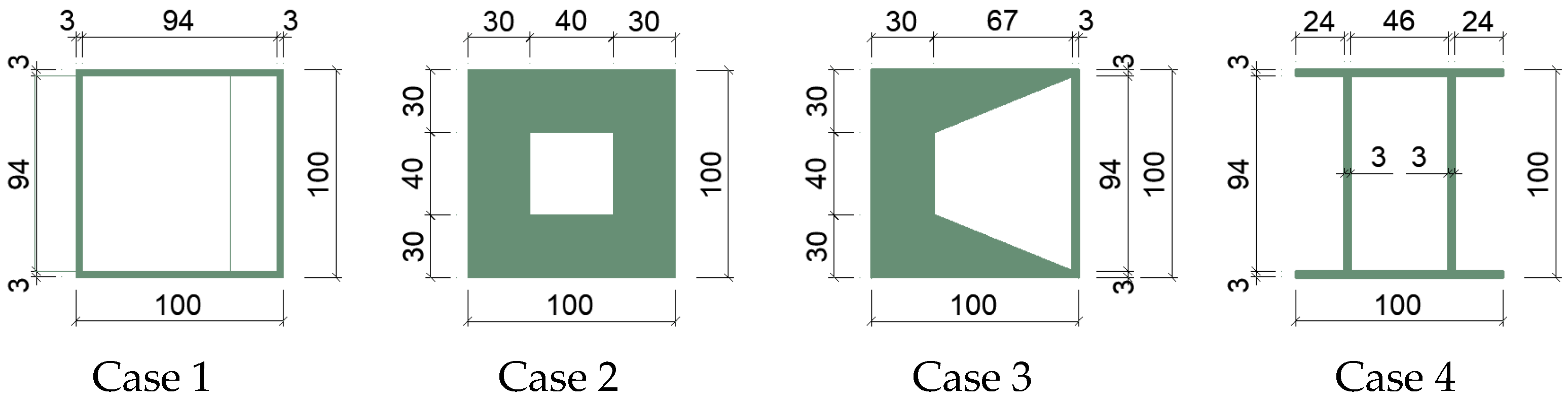

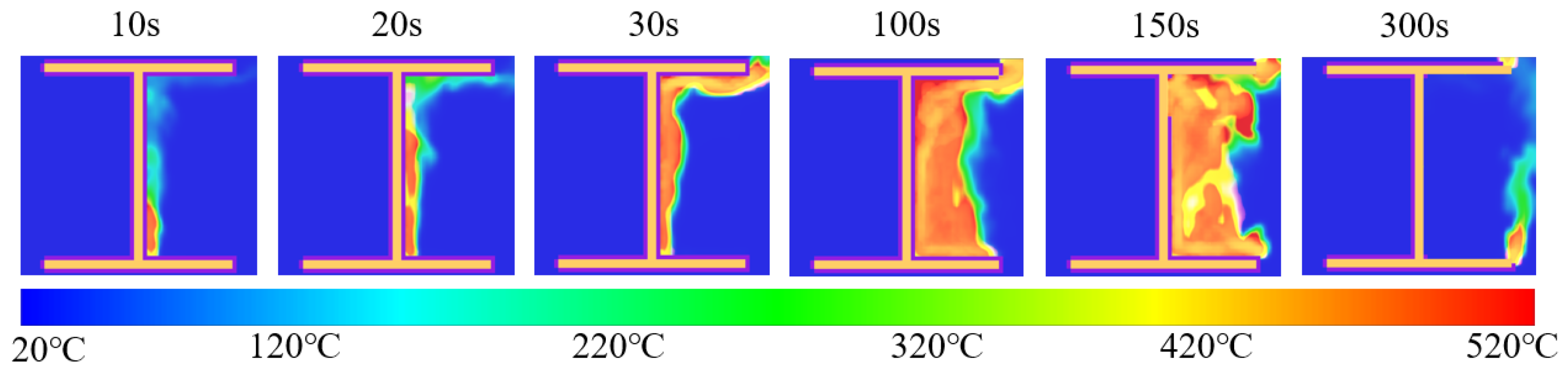

- Generalizability Assessment of the Coupled Strategy

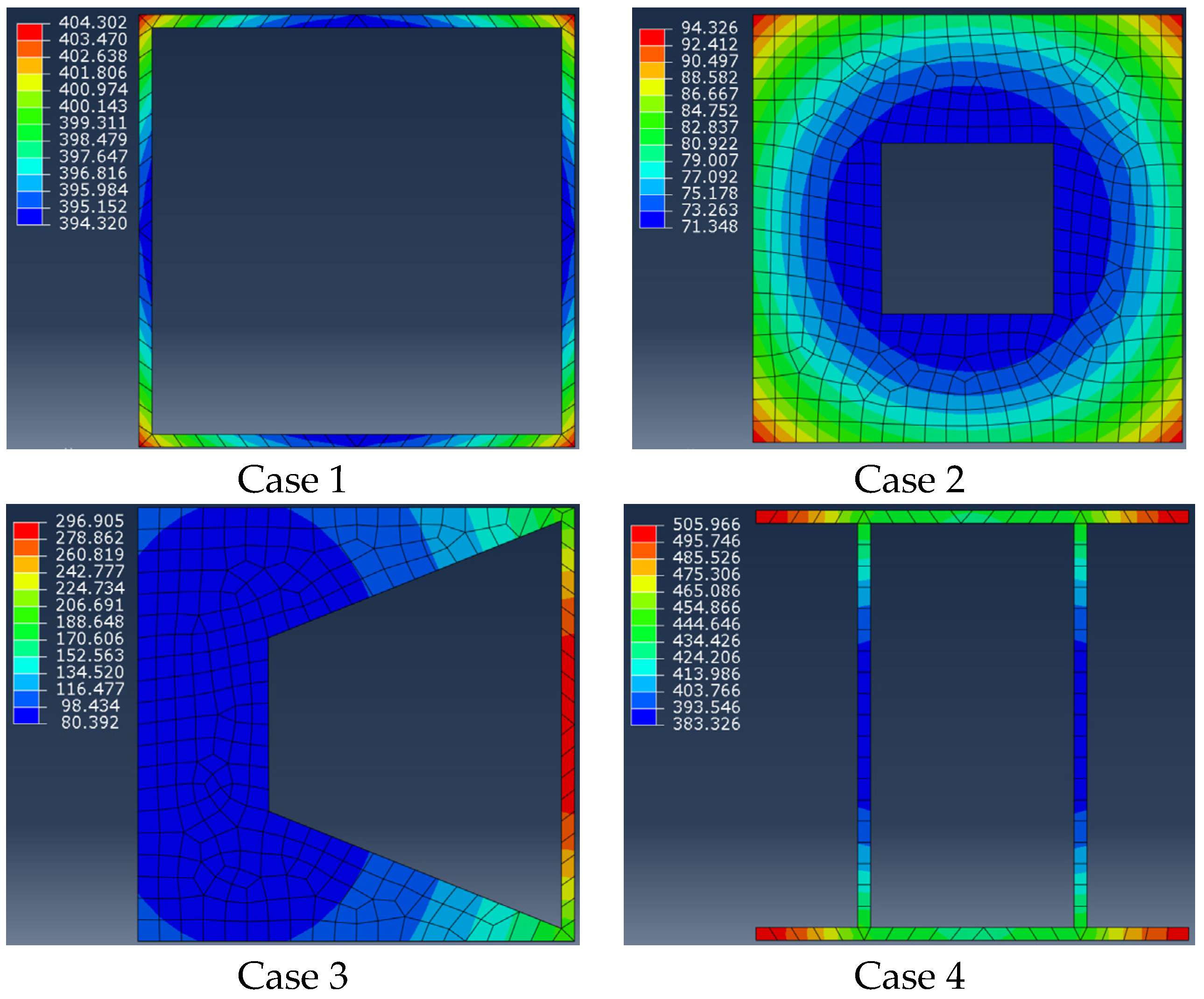

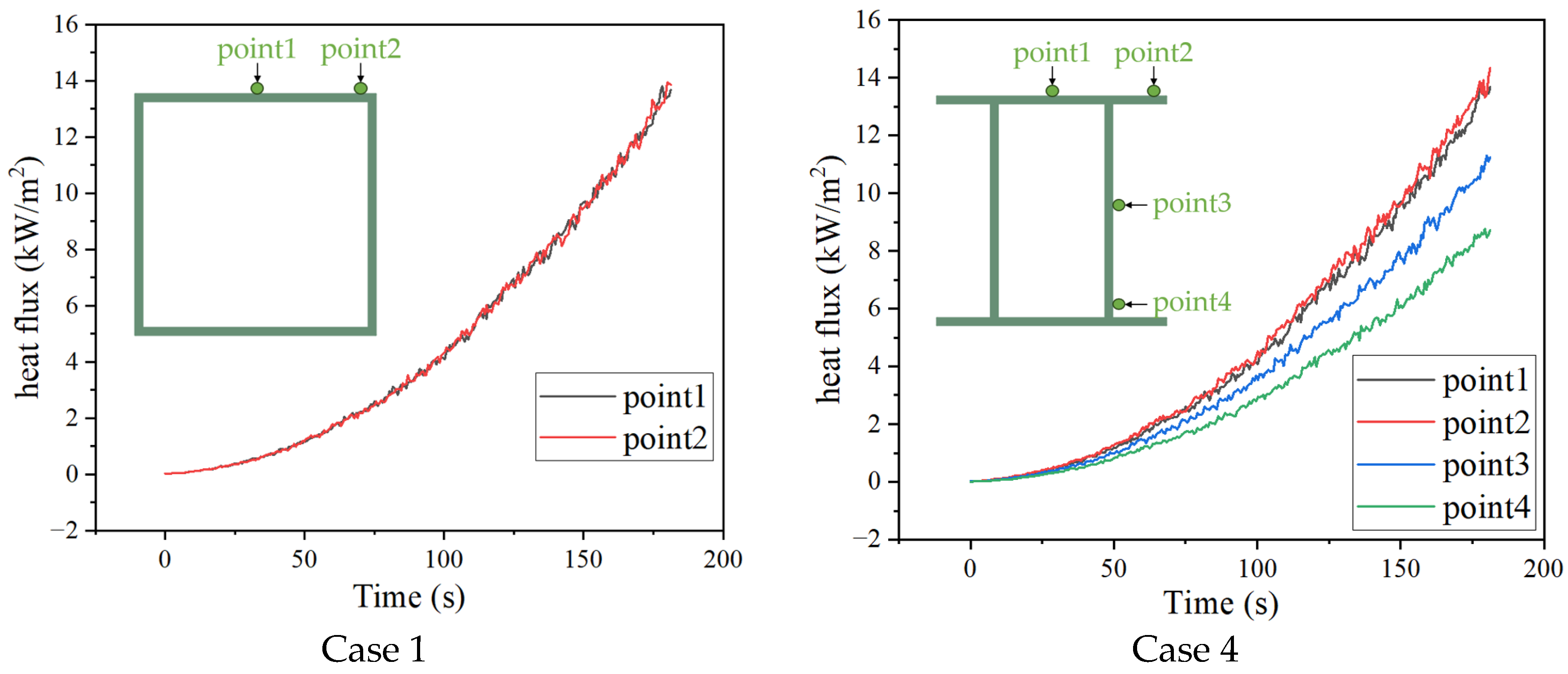

- Case 1: Thin-walled square steel tube with a 100 mm × 100 mm external square profile and a uniform wall thickness of 3 mm.

- Case 2: Thick-walled square steel tube with a 100 mm × 100 mm external square profile and a uniform wall thickness of 30 mm.

- Case 3: Square steel tube with a tapered wall thickness. The external profile is a 100 mm × 100 mm square, and the wall thickness varies linearly from 30 mm on the left side to 3 mm on the right side.

- Case 4: Thin-walled steel section with flanges. The overall external dimensions are 100 mm × 100 mm, and all walls have a uniform thickness of 3 mm.

3. Fire Risk Analysis of the Anchor Rod–Sealant System

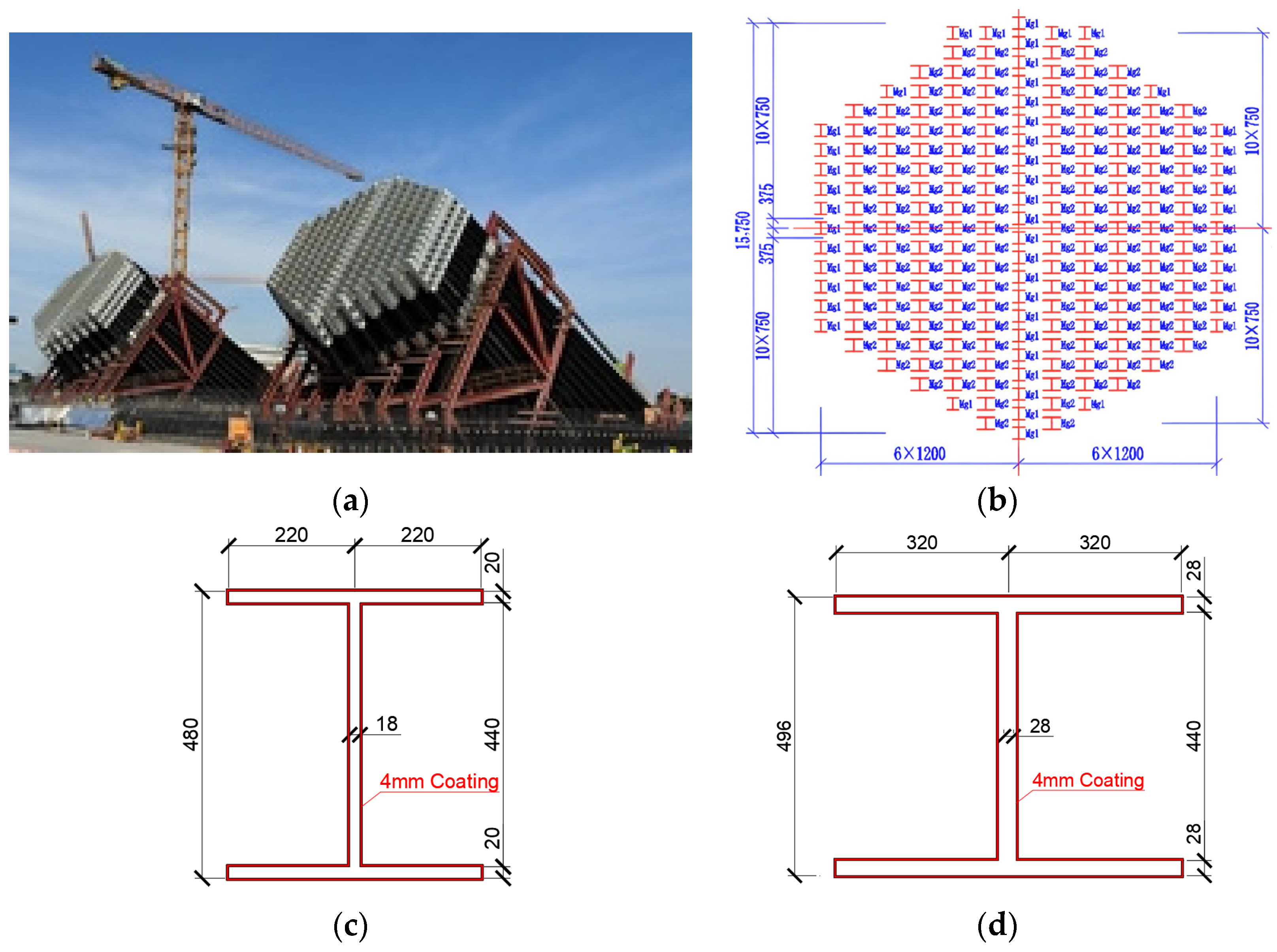

3.1. Engineering Background and System Description

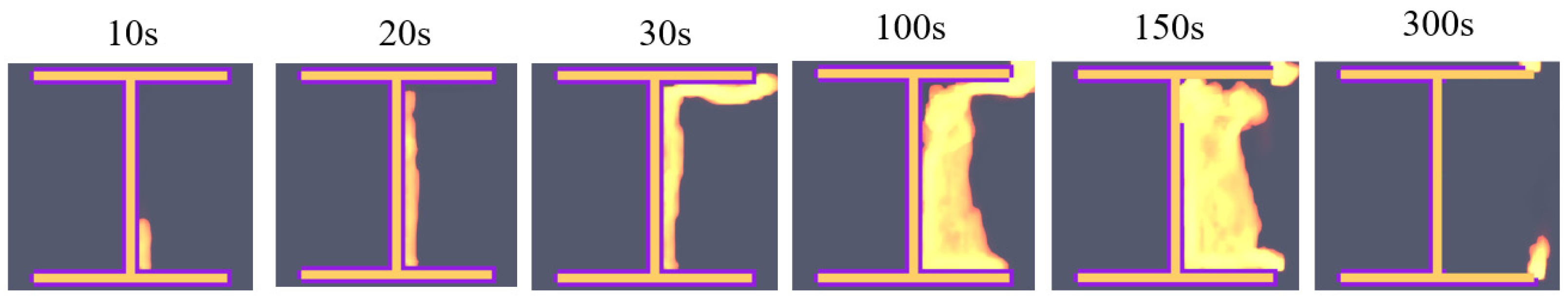

3.2. Thermal Response of a Single Anchor Rod Configuration

3.2.1. Open-Flame Test

3.2.2. Numerical Simulation

3.2.3. Results and Comparisons

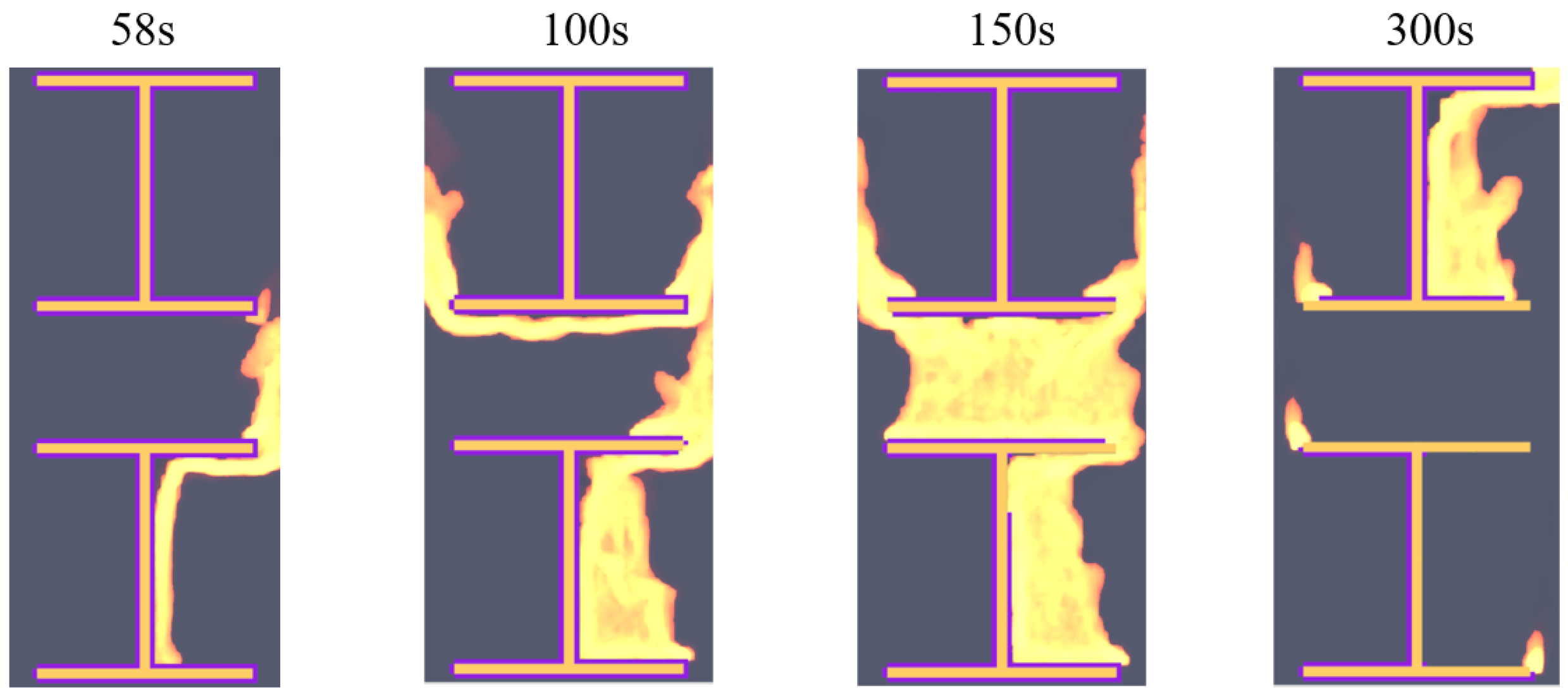

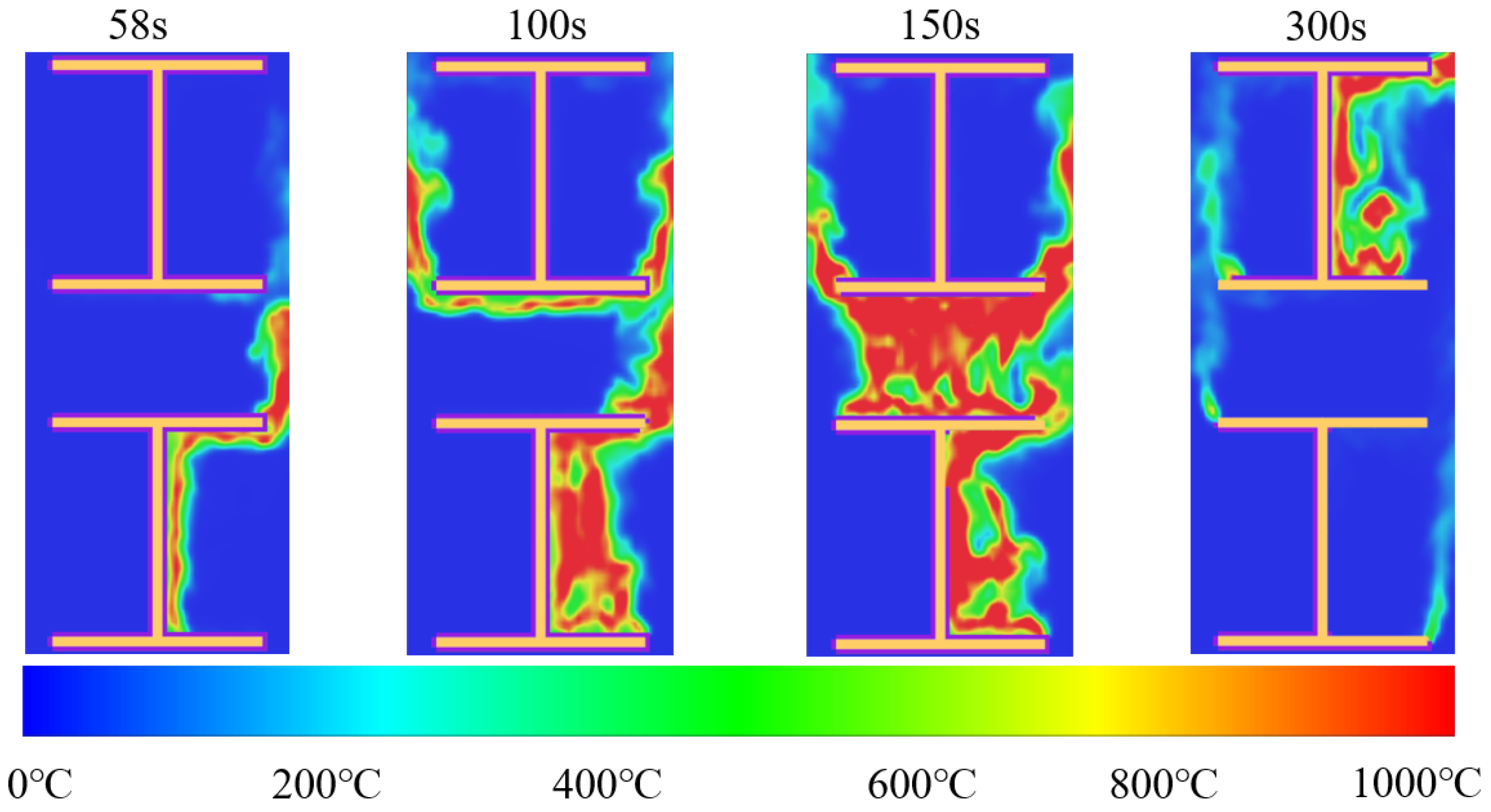

3.3. Flame Propagation in a Double Anchor Rod Configuration

3.3.1. Model of the Double-Anchor-Rod System

3.3.2. Results and Discussion

4. Sensitivity Analysis and Identification of Fire-Safe Thermophysical Thresholds

4.1. Model and Parameter Settings

- (1)

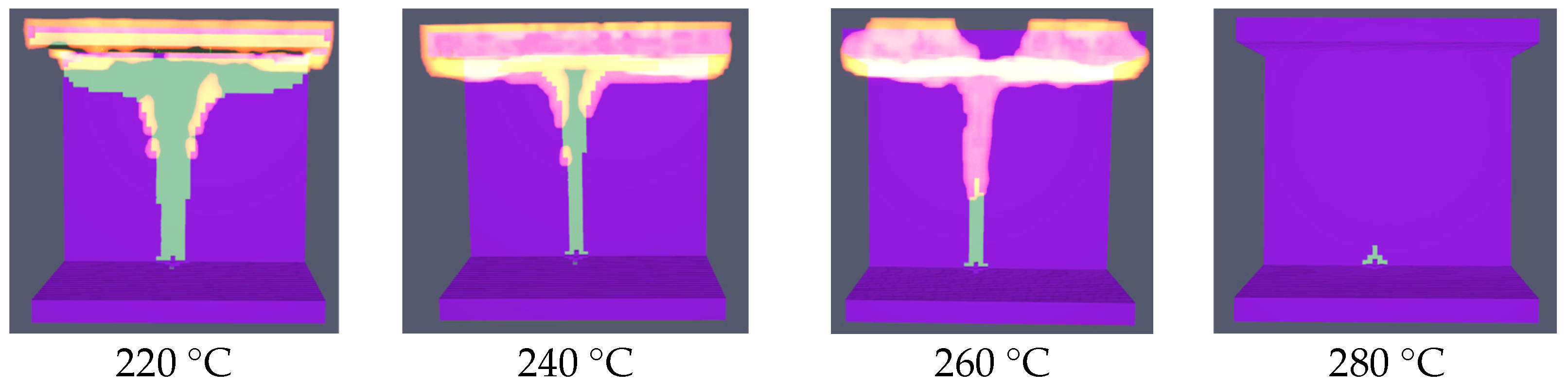

- Ignition Temperature: Four simulation nodes were uniformly defined within the range of 220 °C to 280 °C. Thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity were held constant at 0.10 W/(m·K) and 1.1 kJ/(kg·K), respectively.

- (2)

- Thermal Conductivity: Five simulation nodes were uniformly distributed within the range of 0.14 W/(m·K) to 0.26 W/(m·K). Ignition temperature and specific heat capacity were fixed at 280 °C and 1.1 kJ/(kg·K), respectively.

- (3)

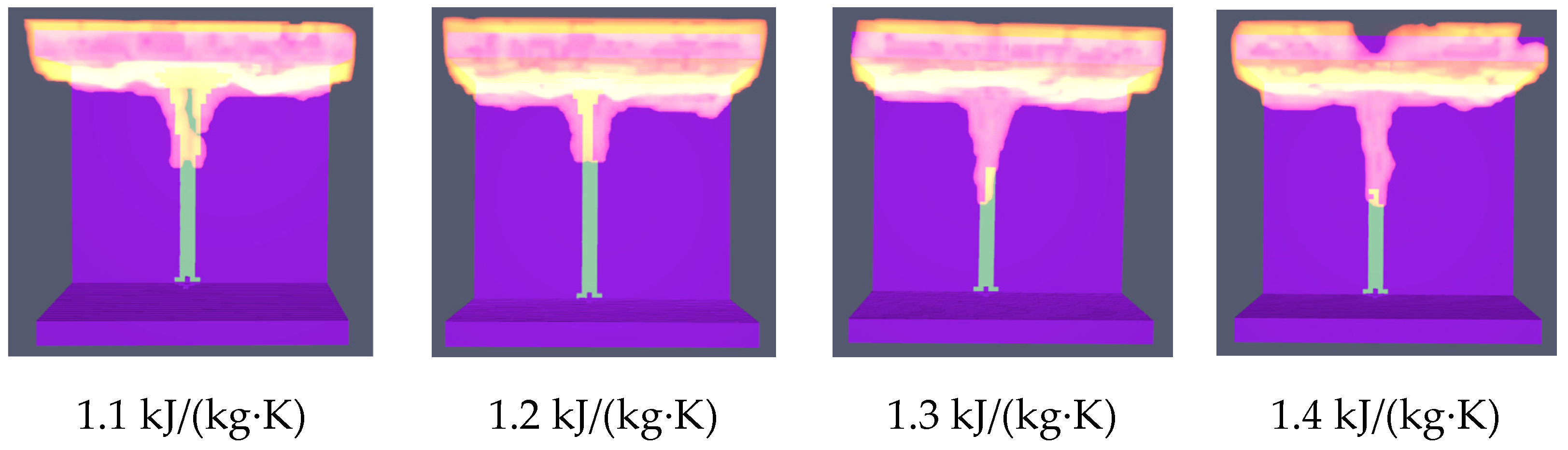

- Specific Heat Capacity: Six simulation cases were uniformly established within the range of 1.1 kJ/(kg·K) to 1.5 kJ/(kg·K). Ignition temperature and thermal conductivity were maintained at 240 °C and 0.10 W/(m·K), respectively.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Effect of Ignition Temperature

4.2.2. Effect of Thermal Conductivity

4.2.3. Specific Heat Capacity

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- A robust coupled FDS–ABAQUS simulation strategy was developed and validated. By integrating fire-driven fluid dynamics with radiative/convective heat transfer and three-dimensional solid conduction, this framework effectively bridges key multi-physics gaps in structural fire analysis. The strategy reliably predicts temperature-field evolution under fire exposure, as demonstrated through validation against standard fire-resistance tests. Furthermore, it shows good robustness across varying geometric scales, and the capability to capture coupled convection-radiation-conduction phenomena in confined spaces. Consequently, the proposed approach provides a reliable numerical tool for analyzing thermal responses in such structural systems.

- (2)

- The fire risk of the anchor rod–sealant system was assessed through simulations of both single- and double-rod configurations. The results show that the sealant coating on the rod surface is readily ignited by hot particles or localized sparks and sustains continuous combustion, a process that generates extreme local temperatures capable of raising the rod temperature above 900 °C. Furthermore, the simulations reveal that when one rod is on fire, the rising hot plume is highly likely to ignite the sealant on the adjacent upper rod, triggering a progressive upward chain-reaction of fire spread. These findings indicate that densely arranged anchor-rod arrays are subject to a systemic risk of fire propagation.

- (3)

- A single-factor sensitivity analysis identified ignition temperature and thermal conductivity as the primary material properties controlling self-extinguishing behavior. For reliable suppression of flame spread and promotion of self-extinction, sealants should meet or exceed the following dual thresholds: an ignition temperature ≥280 °C and a thermal conductivity ≥0.26 W/(m·K). While specific heat capacity can retard flame growth, its role in achieving self-extinction is secondary.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, G.; He, X.; Long, H.; Lu, J.; Wang, Q. Corrosion Damage Evolution Study of the Offshore Cable-Stayed Bridge Anchorage System Based on Accelerated Corrosion Test. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Shen, R.; Qi, D.; Li, Z. Fire resistance analysis and protection measures for cable components of suspension bridges. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 220, 108852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Rao, R. Damage analysis and assessment of concrete T-girder bridge based on fire scene numerical reconstruction. Adv. Bridge Eng. 2024, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlqvist, J.; Van Hees, P. Validation of FDS for large-scale well-confined mechanically ventilated fire scenarios with emphasis on predicting ventilation system behavior. Fire Saf. J. 2013, 62, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Maciejewski, K.; Ghonem, H. Simulation of Viscoplastic Deformation of Low Carbon Steel Structures at Elevated Temperatures. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2012, 21, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palit, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.K. Response of Steel Frame Assembly Under Localized Fire Effect. Proc. Int. Struct. Eng. Constr 2022, 9, STR-34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alos-Moya, J.; Paya-Zaforteza, I.; Garlock, M.E.M.; Loma-Ossorio, E.; Schiffner, D.; Hospitaler, A. Analysis of a bridge failure due to fire using computational fluid dynamics and finite element models. Eng. Struct. 2014, 68, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alos-Moya, J.; Paya-Zaforteza, I.; Hospitaler, A.; Loma-Ossorio, E. Valencia bridge fire tests: Validation of simplified and advanced numerical approaches to model bridge fire scenarios. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2019, 128, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Silva, J.G.; Weinschenk, C.; Kamikawa, D.; Hasemi, Y. Simulation Methodology for Coupled Fire-Structure Analysis: Modeling Localized Fire Tests on a Steel Column. Fire Technol. 2016, 52, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, A. A simple method for combining fire and structural models and its application to fire safety evaluation. Autom. Constr. 2018, 87, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, G.-Q. Performance of steel cable-stayed bridges in ship fires, part I: Numerical method and baseline fire scenario study. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 210, 108090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, V.K.; Aziz, E.M.; Naser, M.Z. Strategies for enhancing fire performance of steel bridges. Eng. Struct. 2017, 131, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Agrawal, A.K. Safety of Cable-Supported Bridges During Fire Hazards. J. Bridge Eng. 2016, 21, 04015082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Z.; Song, C.; Li, X.; Tang, C. Review and discussion on fire behavior of bridge girders. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. Engl. Ed. 2022, 9, 422–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Liu, G.; Ni, Y.; Xu, B.; Ge, S.; Qi, J. Fire-induced temperature response of main cables and suspenders in suspension bridges: 1:4-scaled experimental and numerical study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 68, 105878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Bae, J.; Ryu, J.; Ju, Y.K. Fire Design Equation for Steel–Polymer Composite Floors in Thermal Fields Via Finite Element Analysis. Materials 2020, 13, 5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, T.A.C.; Do Rêgo Silva, J.J.; Dos Santos, M.M.L.; Costa, L.M. Fire resistance of built-up cold-formed steel columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 177, 106456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 834; Fire Resistance Tests—Elements of Building Construction. Part 1: General Requirements. International Organization of Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

| Temperature (°C) | Specific Heat Capacity (kJ/(kg·K)) | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.5 | 54 |

| 100 | 0.52 | 50 |

| 200 | 0.55 | 48 |

| 400 | 0.62 | 43 |

| 600 | 0.7 | 38 |

| 800 | 0.8 | 33 |

| Density | Heat Release Rate | Ignition Temperature | Combustion Heat | Mass Burning Rate | Specific Heat Capacity | Thermal Conductivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1300 kg/m3 | 897 kW | 200 °C | 14.80 MJ/kg | 0.664 g/s | 1 kJ/(kg·K) | 0.1 W/(m·K) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, K.; Rao, R.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, Q. Analysis of Multi-Physics Thermal Response Characteristics of Anchor Rod and Sealant Systems Under Fire Scenarios. Buildings 2026, 16, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020383

Tian K, Rao R, Zeng Y, Chen S, Xu Q. Analysis of Multi-Physics Thermal Response Characteristics of Anchor Rod and Sealant Systems Under Fire Scenarios. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020383

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Kui, Rui Rao, Yu Zeng, Sihang Chen, and Qingyuan Xu. 2026. "Analysis of Multi-Physics Thermal Response Characteristics of Anchor Rod and Sealant Systems Under Fire Scenarios" Buildings 16, no. 2: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020383

APA StyleTian, K., Rao, R., Zeng, Y., Chen, S., & Xu, Q. (2026). Analysis of Multi-Physics Thermal Response Characteristics of Anchor Rod and Sealant Systems Under Fire Scenarios. Buildings, 16(2), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020383