Research on Landscape Enhancement Design of Street-Facing Façades and Adjacent Public Spaces in Old Residential Areas: A Commercial Activity Optimization Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Is it feasible to open the boundaries of old residential areas?

- (2)

- Does the commercialization of street-facing façades in old residential areas interfere with the functionality and accessibility of urban sidewalks?

- (3)

- How can the commercial development of street-facing surfaces and the improvement of urban sidewalk landscapes be synergistically advanced?

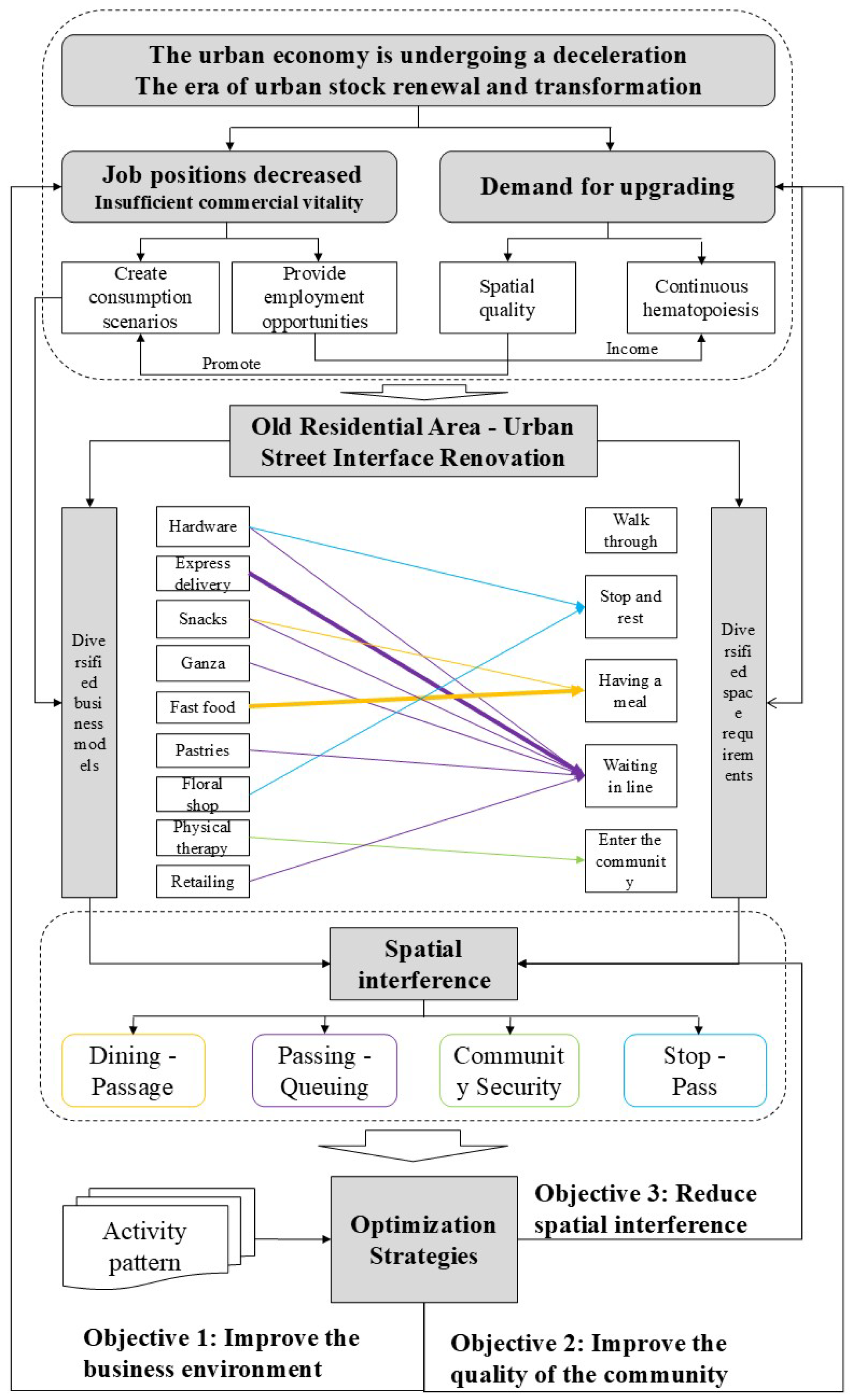

2. Research Framework

3. Research Area and Methods

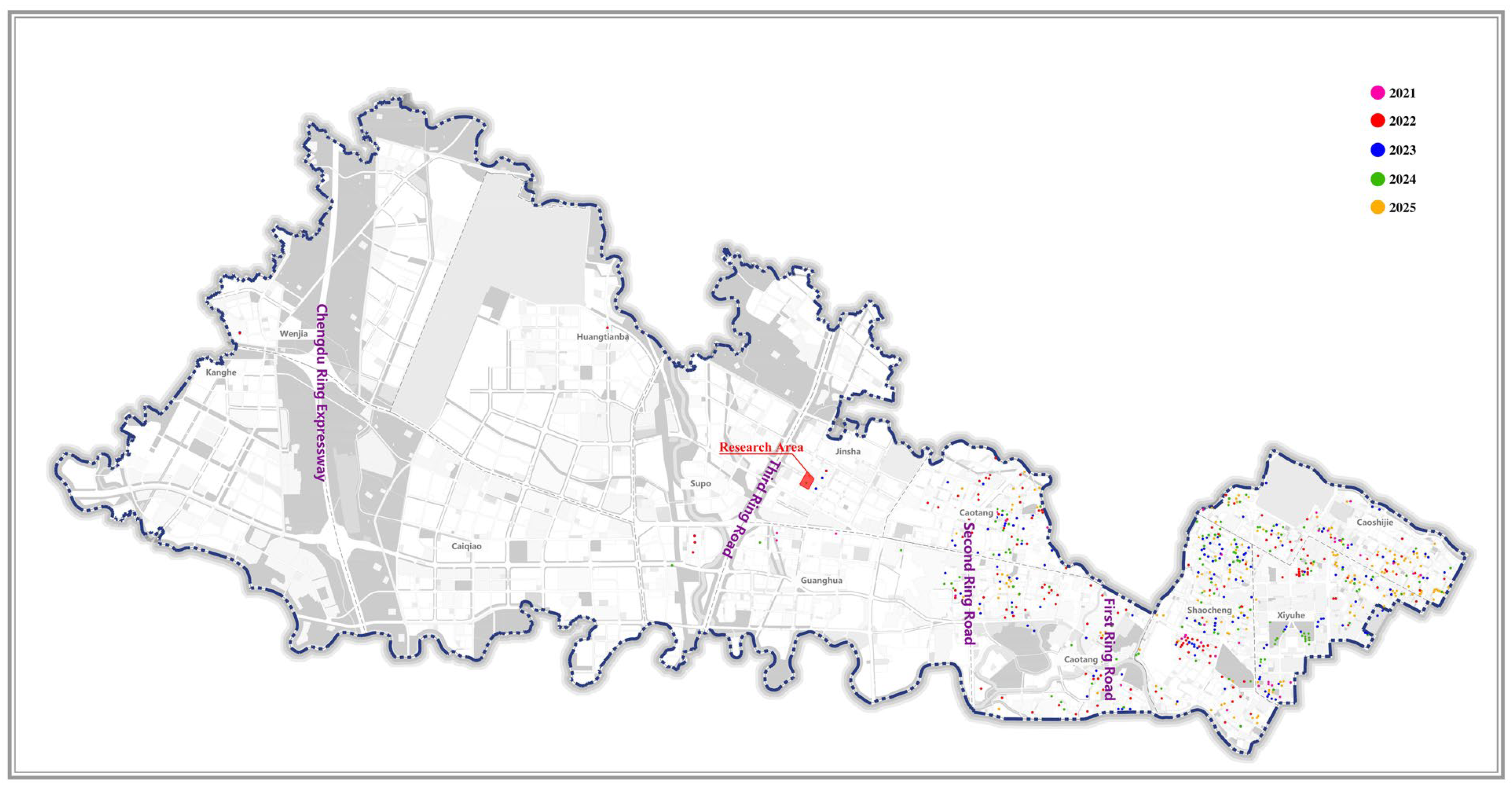

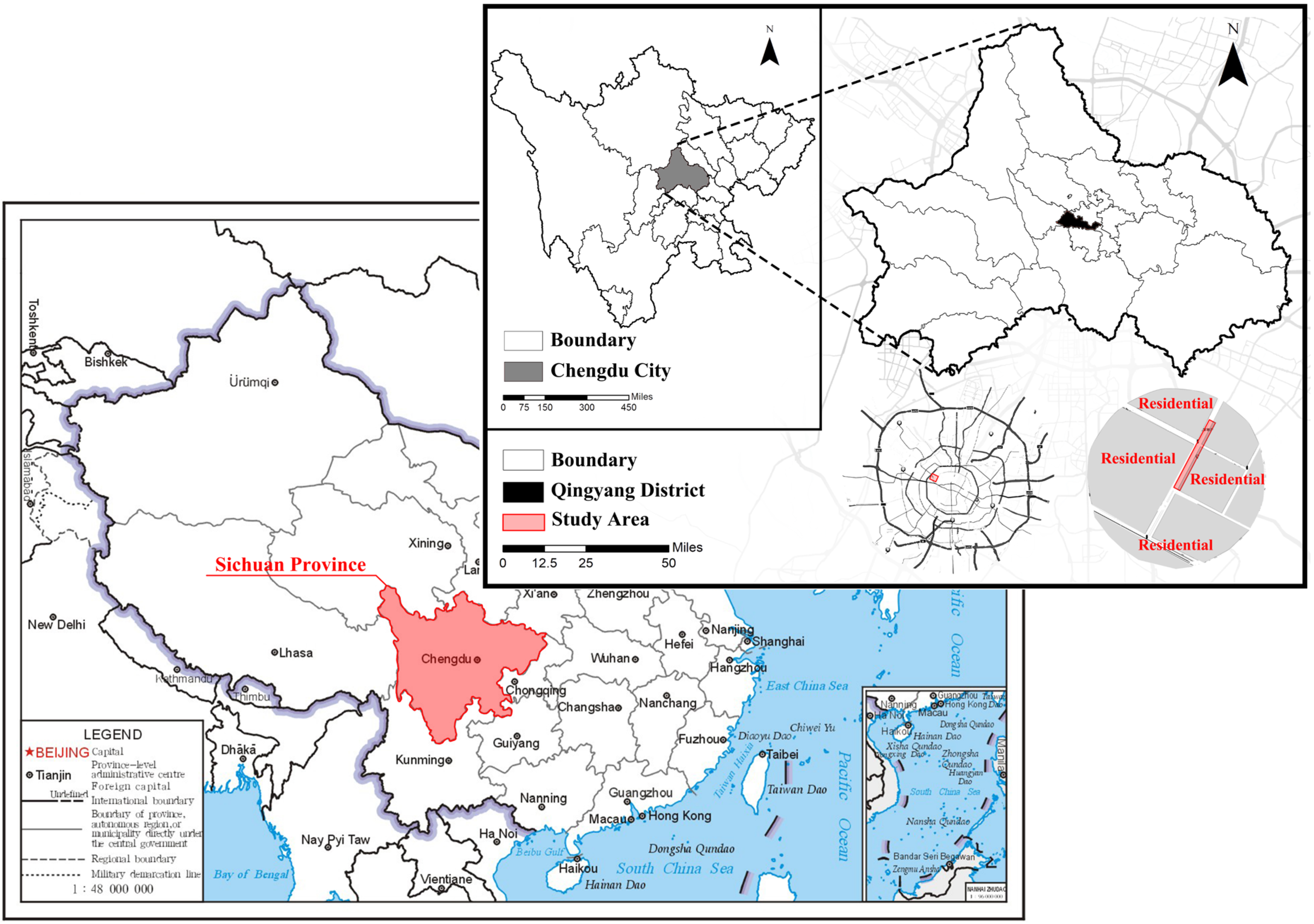

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Research Methods

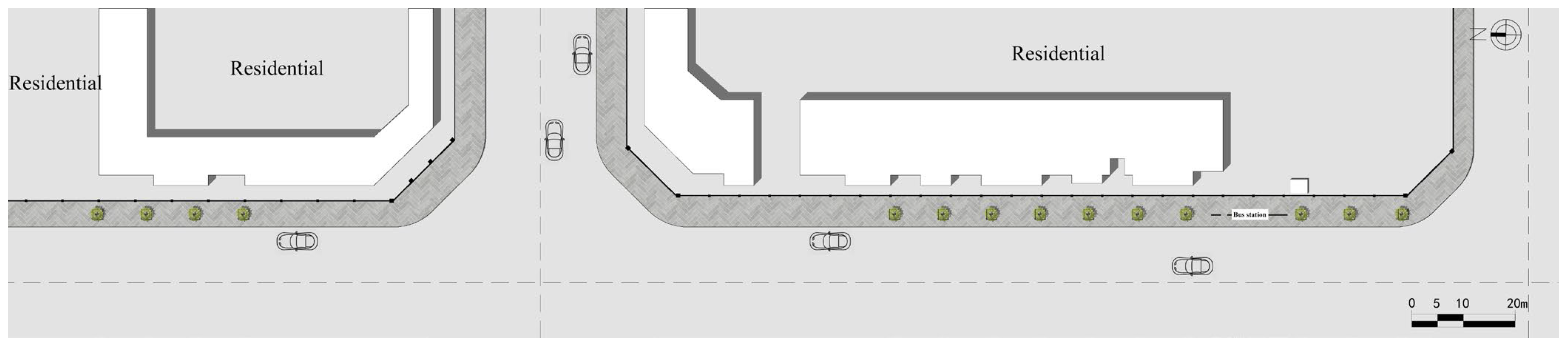

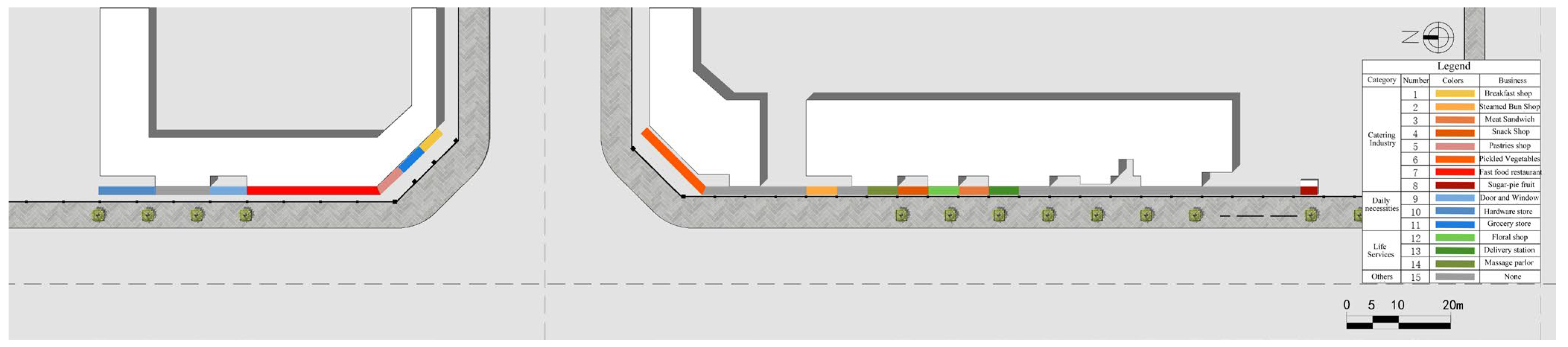

3.2.1. Spatial Surveying

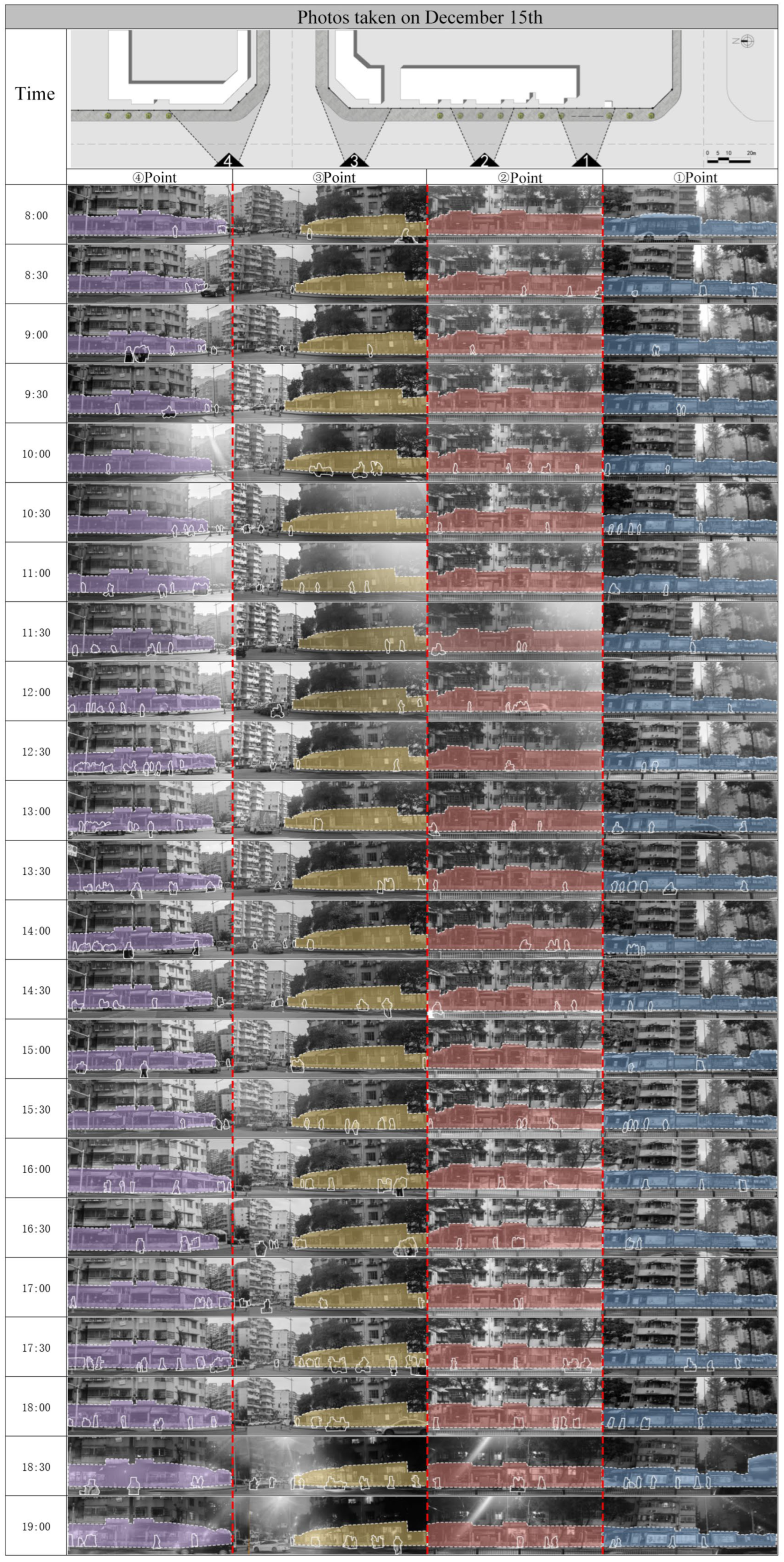

3.2.2. Activity Record

- (1)

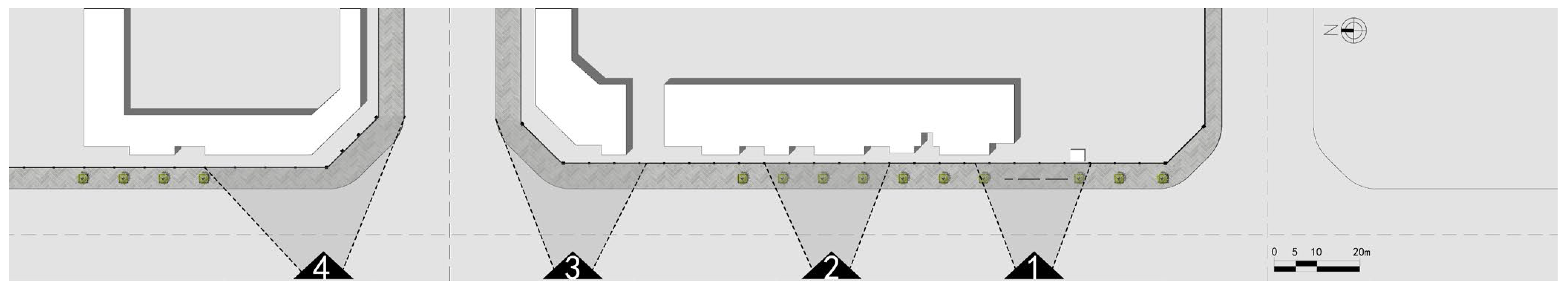

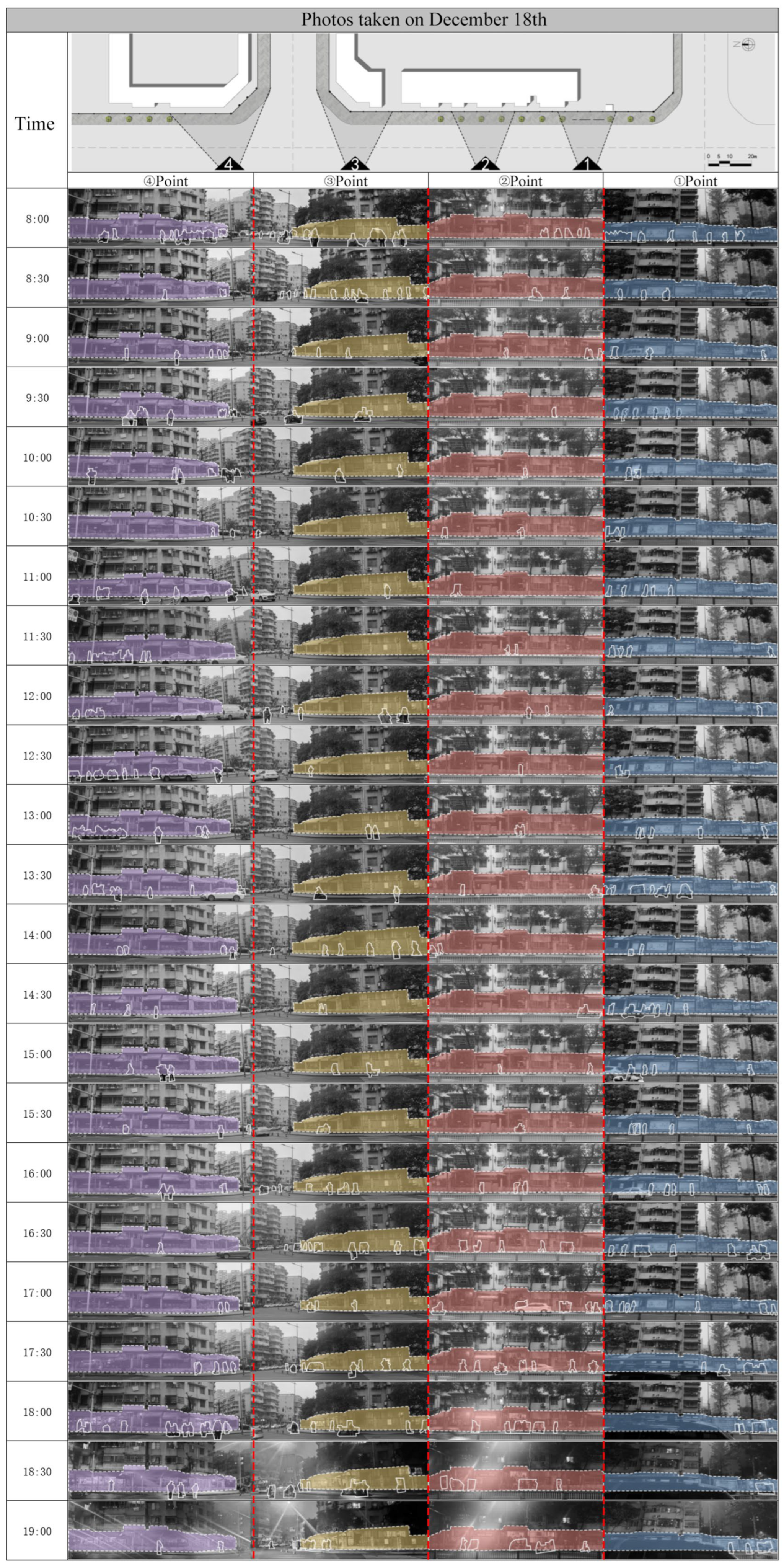

- Definition of observation points. Guided by the existing street conditions and business type distribution patterns, this study selected four key observation points centered on bus stops, courier stations, street-corner retail outlets, and fast-food restaurants. For the convenience of later analysis, we have respectively encoded the observation points as P1–P4. These locations collectively encompassed 90% of the road segments and commercial establishments, represent all business categories, and specifically target potential conflict zones identified during the preliminary research phase. The spatial layout of these observation points is illustrated in Figure 4.

- (2)

- Recording period. To comprehensively capture the characteristics of commercial activities and urban public activities across different time periods, this study selected 16 December 2024 (Sunday) and 18 December 2024 (Wednesday) as observation dates, representing weekend and weekday activity patterns respectively. The recording period was set from 8:00 to 19:00, based on winter sunrise and sunset patterns in Chengdu and activity timeframes identified during the preliminary research phase. Commercial and public activities outside this timeframe were minimal, making it unsuitable for analyzing the interactions and potential conflicts between these two types of activities.

- (3)

- Recording method. This study involved four researchers conducting on-site activity documentation. First, smartphone mounts were installed at each observation point to ensure stable positioning and consistent angles for photographic recording. Subsequently, the research team captured images of the streets and street-facing façades of old residential communities from designated locations, completed on-site observation forms, and systematically recorded key information including the number and demographic distribution of people present, types of commercial activities, spatial disturbances, and spatial demands during each interval. Data were collected at 30-min intervals, resulting in a total of 23 sets of image and observational data.

- (4)

- Data organization. First, the street-view images were encoded and categorized into two groups following the methodological framework established by Wen and Sun. Subsequently, folders labeled P1 through P4 were created in sequential order, and the corresponding images were systematically organized within each folder according to the time sequence from 8:00 to 19:00, resulting in a structured and comprehensive data package for subsequent analysis. The time-slice photography method was applied to compile 23 images captured at the same observation point throughout the day, enabling a visual representation of the characteristics and temporal dynamics of commercial and urban public activities. Additionally, the point cluster time series method was utilized to annotate human activity patterns across different time periods on a two-dimensional map. This approach facilitated the identification of spatial conflicts between commercial and public activities during specific periods, thereby offering data-driven insights for subsequent spatial design interventions.

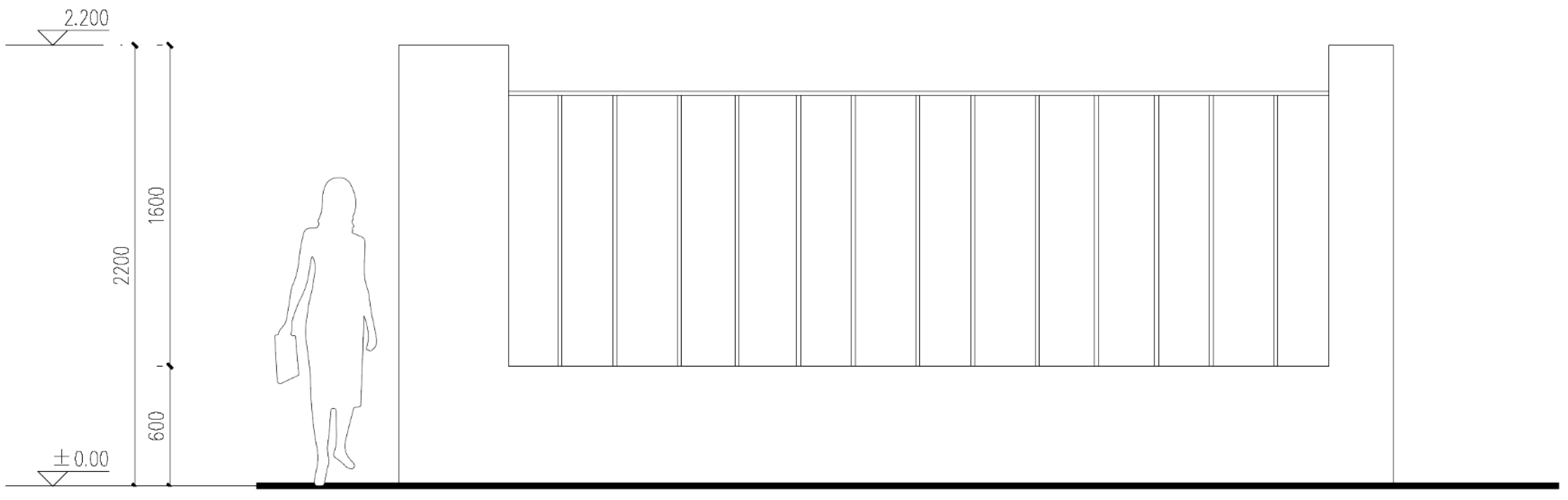

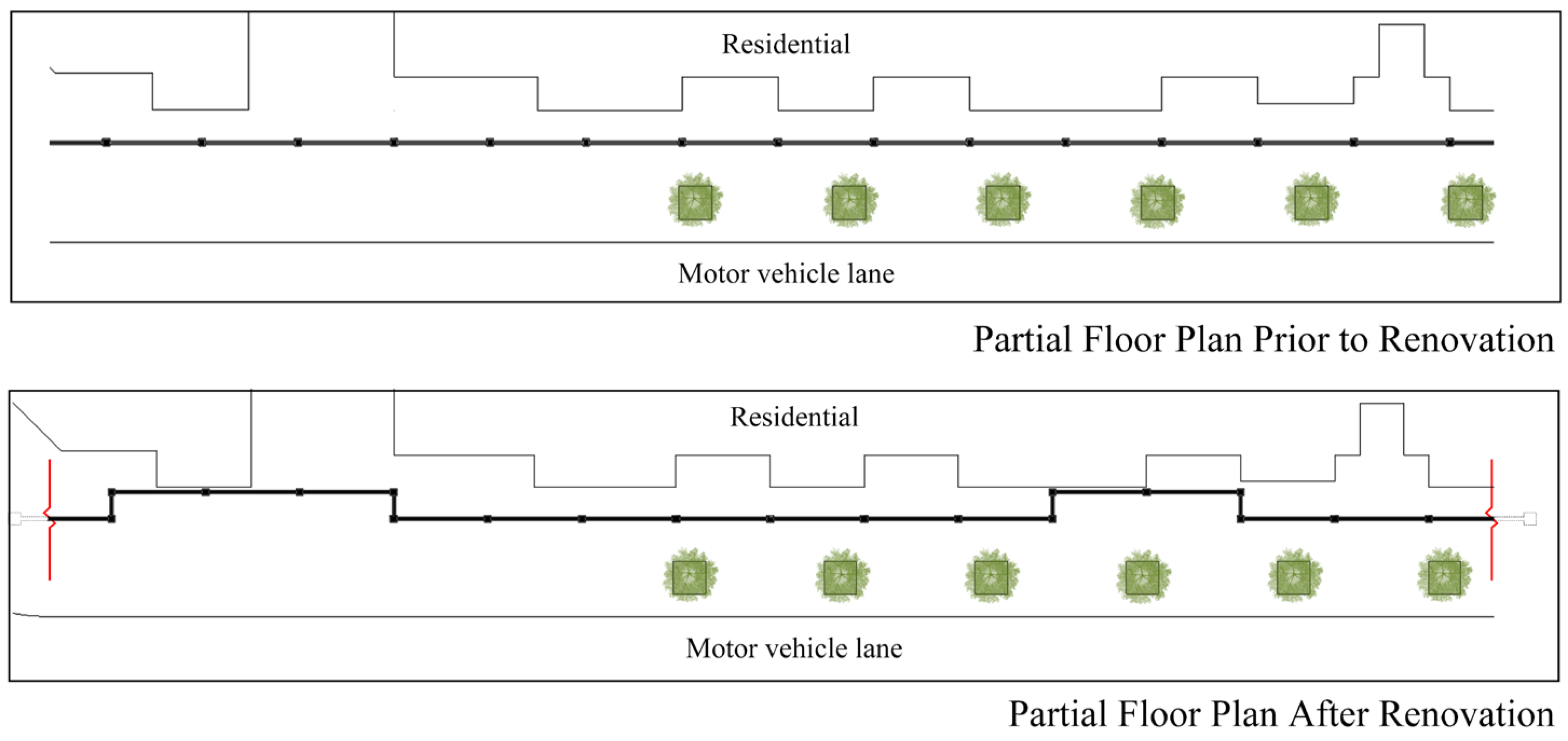

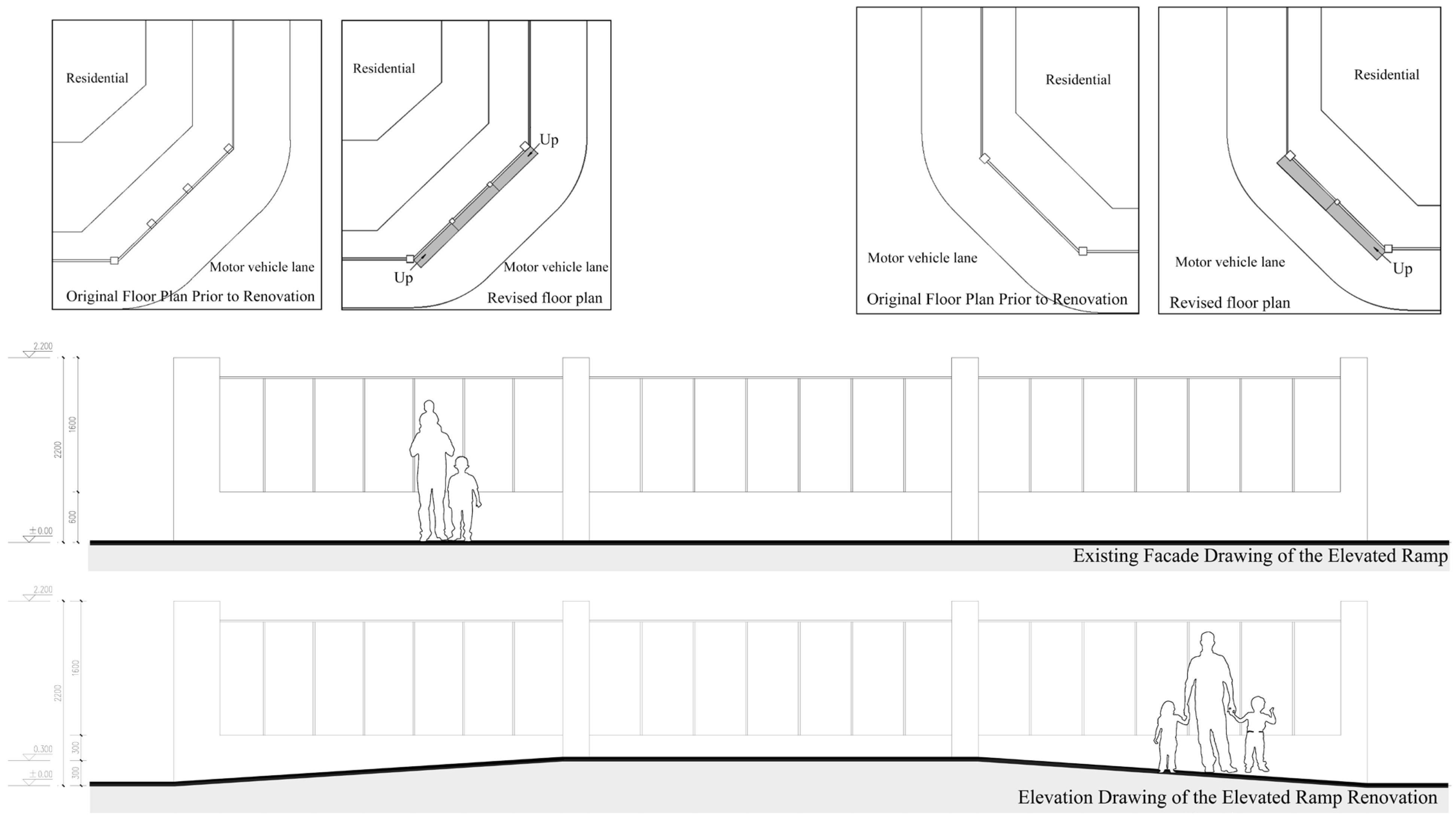

3.2.3. Space Design

4. Results

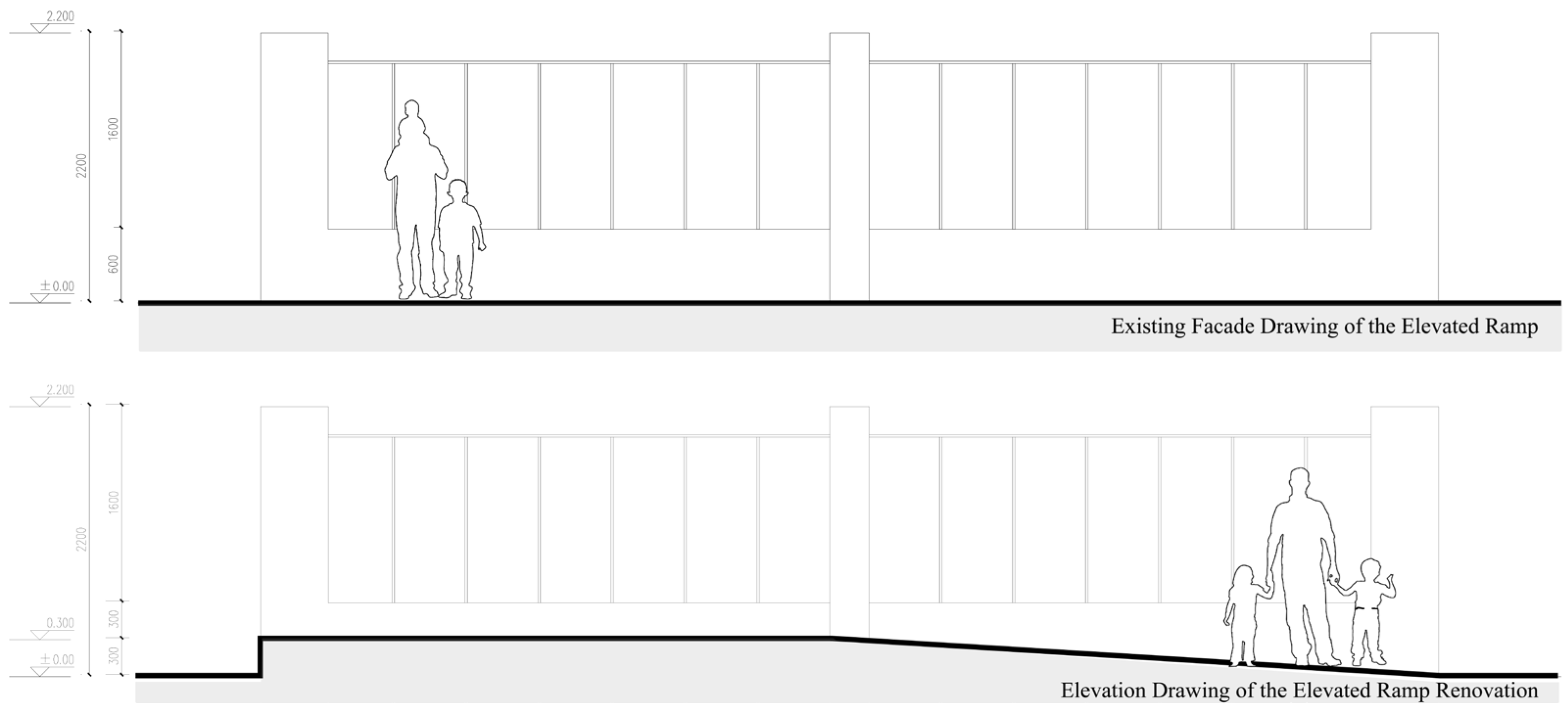

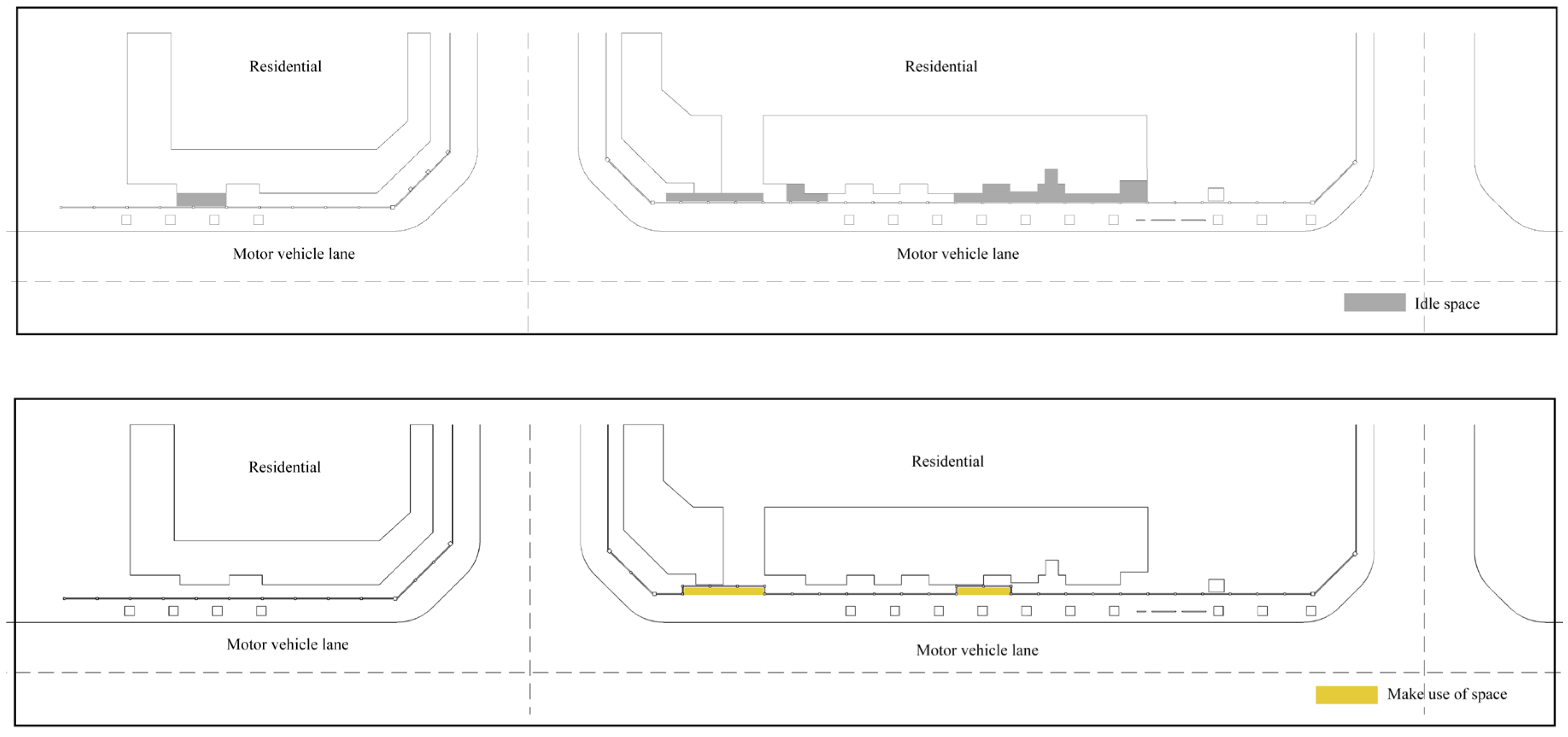

4.1. Spatial Form of the Street Frontage of Old Residential Areas and Urban Streets

4.2. Activity Patterns of Different Age Groups at Different Times

4.3. Spatial Adaptation and Spatial Interference

4.3.1. Complementary Business Hours

4.3.2. Off-Peak Operating Hours

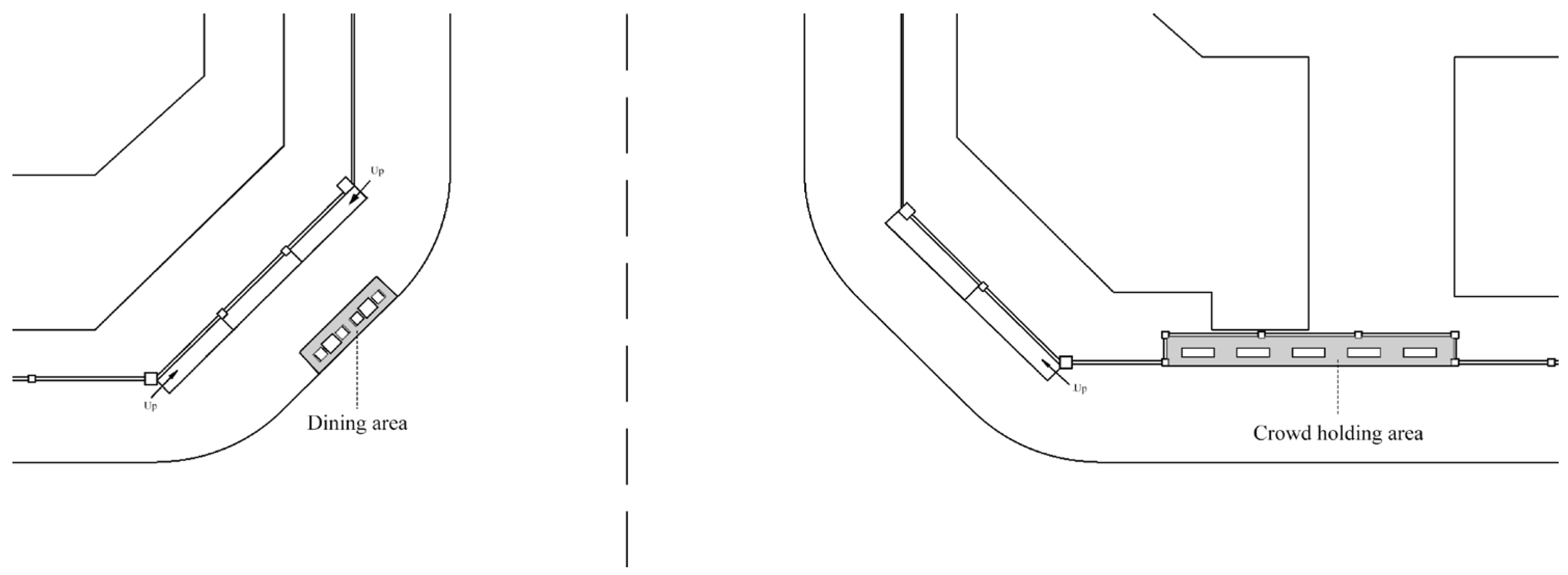

4.3.3. The Queue Was Very Crowded

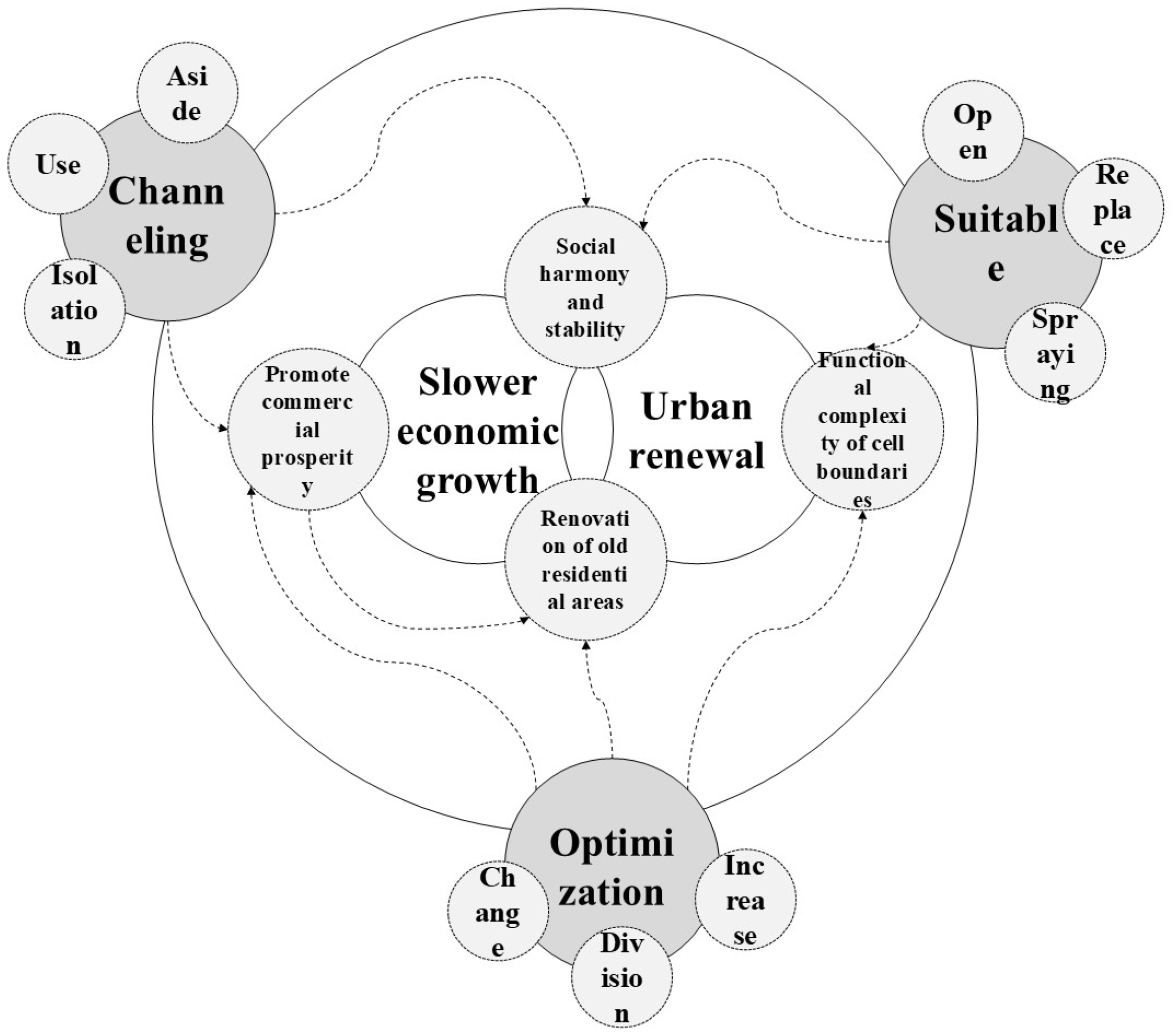

5. Discussion

5.1. Channeling: Spatial Segregation of Passing Traffic and Waiting Crowds

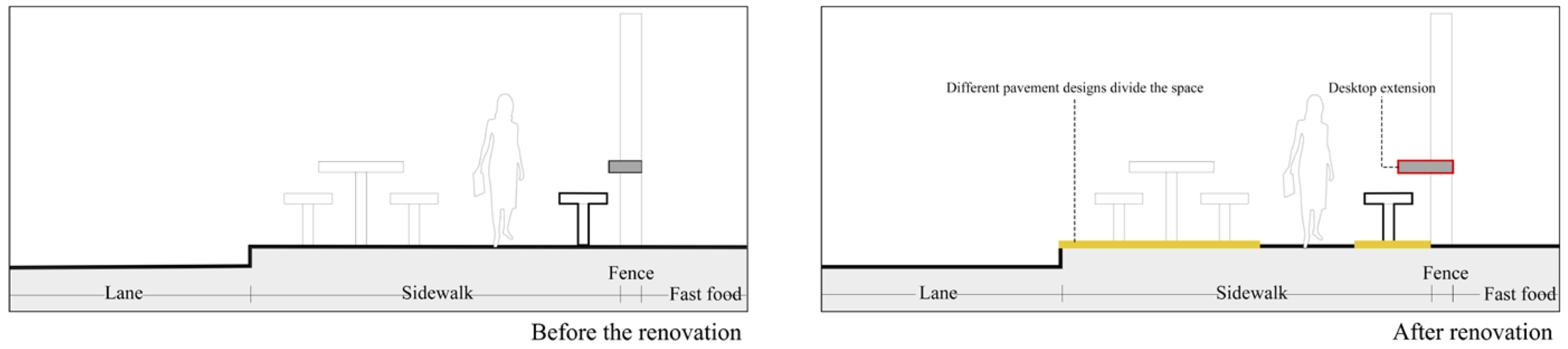

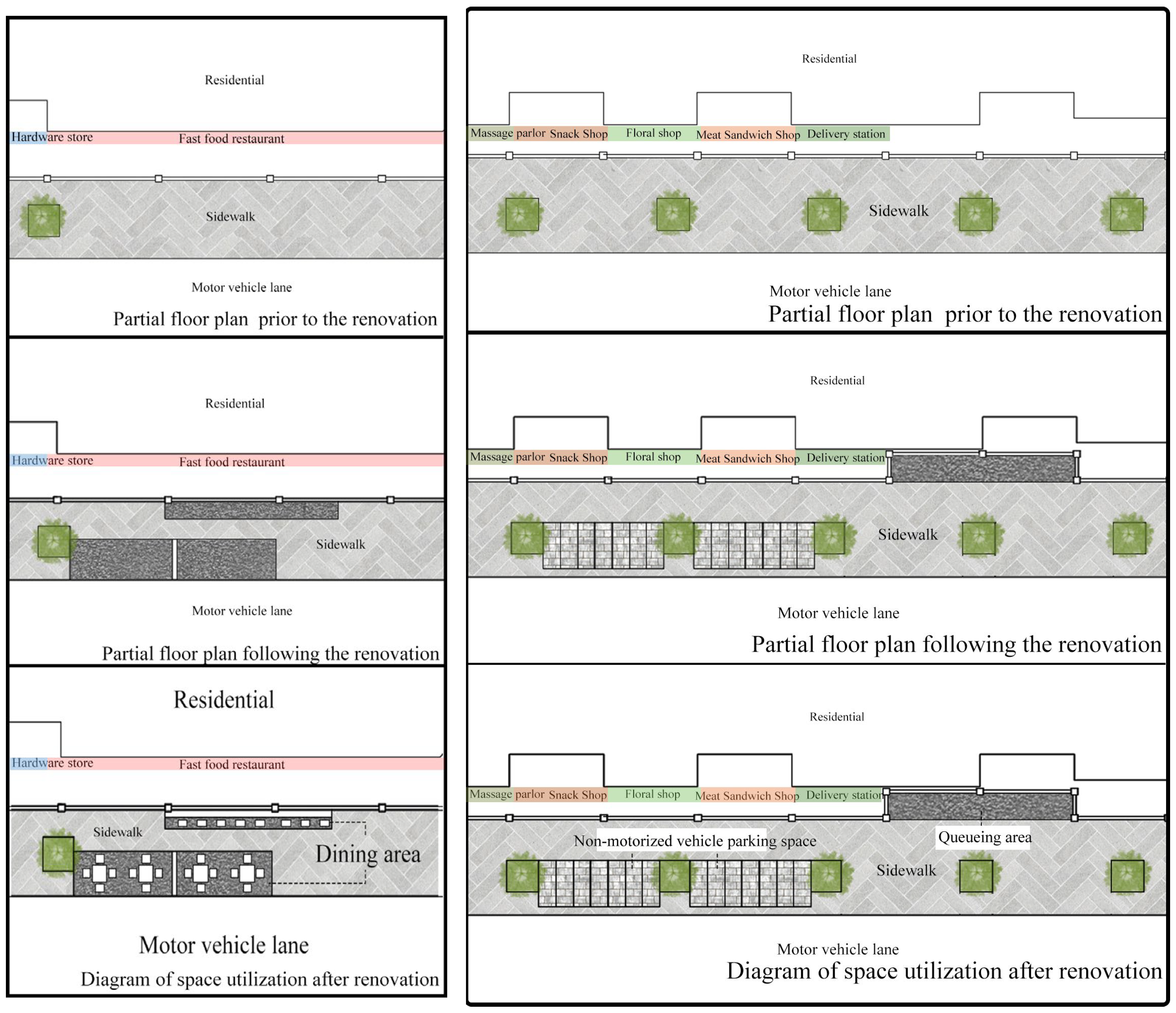

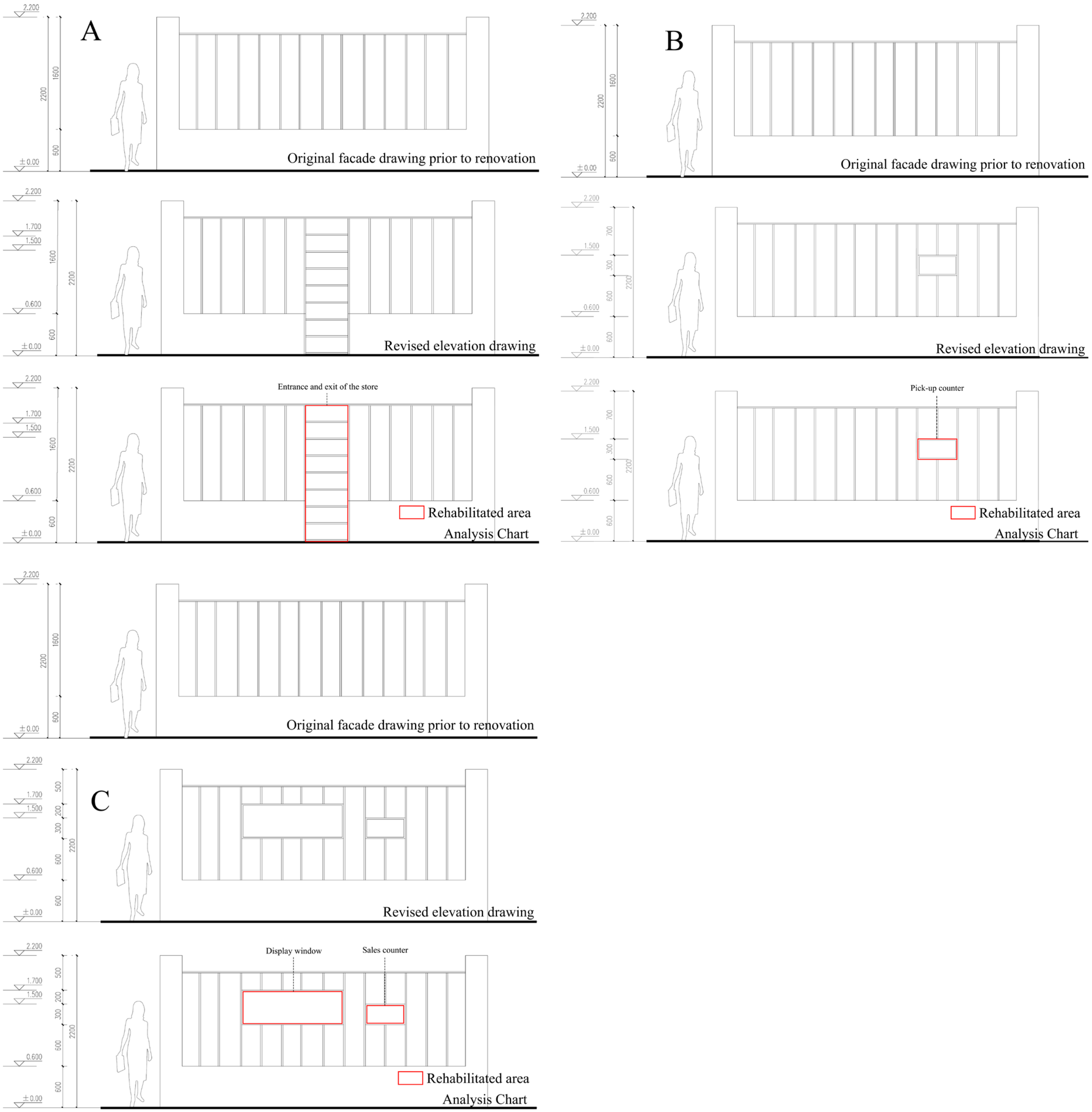

5.2. Optimization: Spatial Experience for Visitors and Diners

5.3. Suitable: Spatial Coordination of Shopping and Service Populations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, Z.-S.; Li, J.-H. Research on High-Quality Industrial Space Planning in the Era of Existing Capacity: A Case Study of Guangzhou. Housing 2021, 36, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.-J.; Xue, L. Research on Urban Design Strategies in the Tibet Region during the Era—Taking Erqi County as an Example. Urban Archit. 2024, 21, 101–105+45. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K.-H. A Preliminary Exploration of Urban Renewal Planning Strategies in the Context of the Existing Population Era: A Case Study of the Urban Renewal Planning of the South Area of Jiangsu University in Zhenjiang. Housing 2024, 4, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.-J. Exploration of Urban Design Paths in Urban Renewal. Urban Constr. Theory Res. (Electron. Ed.) 2024, 34, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.-W. Analysis of Design Strategies for Old Village Renovation in Guochai Area of Fuzhou City from the Perspective of Urban Renewal. Fujian Archit. 2024, 5, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Urban Renewal and Patchwork in the Era of Existing Urban Structures. Archit. J. 2019, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Research on the Concept and Implementation Path of Urban Renewal: A Case Study of the Functional Area of Changli City Renewal in Fuzhou. Urban Archit. 2024, 21, 707–714. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Research on Urban Design Strategies Oriented towards Landscape Sharing: A Case Study of the Renovation Design of Qixian Industrial Zone in Fengxian District, Shanghai. Urban Archit. 2019, 25, 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G. Urban renewal preserves the memories and cultural heritage of the old city—Longmenhao, a century-old street in Chongqing. Chongqing Archit. 2024, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Y.-F.; Hao, Z.-G.; Wu, J. Research on the Healthy Integration Mechanism of Site Memory and Market Demand in Urban Renewal Design. Urban Archit. 2024, 21, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.-P.; Lin, Y. Strategies for Planning and Renovation of External Public Spaces in Old Residential Areas in Core Business Districts: A Case Study of Liuyun Community. Archit. Cult. 2022, 6, 174–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.-Q.; Liu, S.-F. Complex Adaptive Characteristics of Urban Architectural Heritage in the Era of Accumulated Stock—A Case Study of Harbin. Mod. Urban Res. 2020, 8, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Li, C. Research on an evaluation methodology for urban regeneration in old residential areas of Chengdu, China. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2022, 37, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.-L.; Ding, W. Adaptive Aging Renovation Design for Old Residential Areas Based on Residents’ Environmental Perception and Intelligent Technology: A Case Study of Mei Qi Residential Area in Yangzhou. Cent. China Archit. 2024, 10, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Ye, Z.-J. Research on Micro-Renovation Strategies for Old Residential Areas under Public Safety—Taking Lingcun in Taoyue Road, Jingzhou City as an Example. Cent. China Archit. 2024, 7, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.-H.; Ma, W.-J.; Dian, K. Research on the Adaptation of Outdoor Space Facilities for the Elderly in Old Residential Areas of Taiyuan Based on Elderly Satisfaction. Urban Archit. 2024, 13, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.-Z.; Zhang, J.-J. Renovation Strategies for Public Spaces in Old Residential Areas Based on the Needs of Elderly Outdoor Activities. Mod. Hortic. 2024, 23, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K. Adaptive Aging Renovation of Old Residential Areas. Contemp. Archit. 2024, 7, 5+4. [Google Scholar]

- He, J. Thoughts and Explorations on the Renovation of Age-Friendly and Livable Environments in Old Residential Areas in the New Era. China Build. Decor. Renov. 2024, 17, 133–135. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-D.; Li, Z.-T.; Dai, D.-D. Summary of Barrier-Free Environment Construction in the Renovation of Urban Old Residential Areas. Contemp. Archit. 2024, 7, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z. Energy-saving smart city: An edge computing-based renovation and upgrading scheme for old residential areas. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 2023, 71, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Su, S.; Mao, P. Ageing Suitability Evaluation of Residential Districts Based on Active Ageing Theory. Buildings 2023, 13, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.-J.; Shi, M.-Q. Research on the Sustainable Development of Green Renovation in Old Residential Areas under the Background of Urban Renewal. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 6, 406–413. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, X.; Jun, C.; Hao, J.; Tang, X.; Zhai, J. Assessment on the Effectiveness of Urban Stormwater Management. Water 2021, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Hu, D. Research of practical heat mitigation strategies in a residential district of Beijing, North China. Urban Clim. 2022, 46, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.H.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.L.; Wu, S.; Wang, S. Impact study of landscape renewal design on neighborhood microclimate based on a structural analysis framework considering global warming scenarios. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-L. Modular Update and Renovation Strategy for Entrance Spaces of Old Residential Areas in Shanghai. Hous. Real Estate 2024, 25, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, W.-B. The Design of Public Space Renovation in Old Residential Areas under the “Shared Ring” Concept—Taking Zhengzui Temple Community in Jinan City as an Example. Small Town Constr. 2024, 10, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Hu, Q.-G.; Yao, G. Research on the Healthy Renovation Strategy of Low-Effective Spaces in Old Residential Areas—Taking Tian Da Staff Community as an Example. Cent. China Archit. 2024, 8, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Liu, F.-J. Strategies for Landscape Renovation of Old Residential Areas in Luoyang City from the Perspective of Landscape Services. Mod. Hortic. 2024, 23, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.-M. An Innovative Financing Path for Social Capital Participation in Old Residential Area Renovation Projects: A Case Study of the Renovation of Jin Songbei Community in Beijing. Mod. Urban Res. 2024, 6, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.-B.; Hu, A.-D. Research on the Renovation of Idle Spaces in Old Residential Areas from the Perspective of Business Value: A Case Study of Chu Feng Community in Suizhou City. Archit. Cult. 2024, 6, 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Ye, X.; Chen, J.; Kang, J. Effect of the Visual Landscape and Soundscape Factors on Attention Restoration in the Public Space of Old Residential Areas by VR. Int. J. Acoust. Vib. 2023, 28, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ye, X.; Chen, J.; Fan, X.; Kang, J. Effect of visual landscape factors on soundscape evaluation in old residential areas. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 215, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Construction of demand priority model for the renovation planning of old residential quarters. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 2025, 14727978251361719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananian, P.; Declève, B. Requalification of Old Places in Brussels: Increasing Density, Improving Urbanity. Open House Int. 2010, 35, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Lim, H.S.; Kim, J.T. Sustainable lighting performance of refurbished glazed walls for old residential buildings. Energy Build. 2015, 91, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviste, M.; Musakka, S.; Ruus, A.; Vinha, J. A Review of Non-Residential Building Renovation and Improvement of Energy Efficiency: Office Buildings in Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Germany. Energies 2023, 16, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.V.; Nguyen, T.T.; Phan, C.T.; Ha, K.D. Sustainable redevelopment of urban areas: Assessment of key barriers for the reconstruction of old residential buildings. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2282–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shen, C.; Tang, C.; Feng, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S.; Ren, Z. Research on Multi-Objective Optimization of Renovation Projects in Old Residential Areas Based on Evolutionary Algorithms. Buildings 2024, 14, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yang, S.; Ren, C.; Sun, X. Research on Reconstruction Factor Model of Old Residential Area Based on Multi-Modal Data Fusion. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2025, 32, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Burby, R.J.; Salvesen, D.; Creed, M. Encouraging residential rehabilitation with building codes: New Jersey’s experience. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertsmik, K.A.; Arumägi, E.; Hallik, J.; Kalamees, T. Low carbon emission renovation of historical residential buildings. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 3836–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Yuan, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J. Resident Satisfaction and Influencing Factors of the Renewal of Old Communities. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 04023061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhao, D. Residents’ Satisfaction with Public Spaces in Old Urban Residential Communities: A PLS-SEM and IPMA-Based Case Study of Nankai District, Tianjin. Land 2025, 14, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Ouyang, S.; Gao, X.; Ren, Y. Micro-Renovation Method of Old Residential Areas Based on Parametric Energy Simulation: An Aging Community in Middle China as an Example. Buildings 2025, 15, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Lin, Y.; Qiang, S.; Sun, J. Development of a Built Environment-Self-Efficacy-Activity Engagement-Self-Rated Health Model for Older Adults in Urban Residential Areas. Buildings 2025, 15, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Suo, J.; Zhong, H.; Kou, N.; Song, B.; Li, G. The Impact of Multi-Quality Renewal Elements of Residence on the Subjective Well-Being of the Older Adults—A Case Study of Dalian. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.R.; Siu, O.L.; Yeh, A.G.O.; Cheng, K.H. The impacts of dwelling conditions on older persons’ psychological well-being in Hong Kong: The mediating role of residential satisfaction. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 2785–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Ma, C.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y.; Xiong, Y. Vertical Transportation and Age-Friendly Urban Renewal: A Systematic Framework for Sustainable and Inclusive Communities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadaty, A. Applications of morphological regionalization in urban conservation: The case of Bulaq Abulela, Cairo. Urban Morphol. 2021, 25, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitsazzadeh, E.; Daneshmandian, M.C.; Jahani, N.; Tahsildoost, M. Delineating protective boundaries using the HUL approach a case study: Heritage waterways of Isfahan. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, A.; Rhee, H.J. When are urban growth boundaries not second-best policies to congestion tolls? J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, S.; Das, D.N.; Mondal, B.; Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H.; Feng, Y. A neural network and landscape metrics to propose a flexible urban growth boundary: A case study. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benti, S.; Terefe, H.; Callo-Concha, D. Managing the challenges of competing interests of different regions in setting the boundaries of neighboring urban areas: The case of Addis Ababa city administration and oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.S.; Di Giulio, G.; Chaves, R.B.; Lupinetti-Cunha, A.; Duarte, D.; Nascimento, N.; Ruggiero, P.; Silva, L.S.E.; Victor, R.A.B.M.; Metzger, J.P. Urban boundaries are an underexplored frontier for ecological restoration. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Qi, H.; Long, T. Quantitative analysis and design countermeasures of space crime prevention in old residential area quarters. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 2071–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, M.; Ha, K.D.; Phan, C.T. What makes the reconstruction of old residential buildings complex? A study in Vietnamese urban areas. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 7086–7110. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gui, Y.; Gu, M.; Kong, S.; Lin, L. Research on Landscape Enhancement Design of Street-Facing Façades and Adjacent Public Spaces in Old Residential Areas: A Commercial Activity Optimization Approach. Buildings 2026, 16, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020361

Gui Y, Gu M, Kong S, Lin L. Research on Landscape Enhancement Design of Street-Facing Façades and Adjacent Public Spaces in Old Residential Areas: A Commercial Activity Optimization Approach. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020361

Chicago/Turabian StyleGui, Yan, Mengjia Gu, Suoyi Kong, and Likai Lin. 2026. "Research on Landscape Enhancement Design of Street-Facing Façades and Adjacent Public Spaces in Old Residential Areas: A Commercial Activity Optimization Approach" Buildings 16, no. 2: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020361

APA StyleGui, Y., Gu, M., Kong, S., & Lin, L. (2026). Research on Landscape Enhancement Design of Street-Facing Façades and Adjacent Public Spaces in Old Residential Areas: A Commercial Activity Optimization Approach. Buildings, 16(2), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020361