1. Introduction

The demand for ever taller and more complex buildings has prompted a shift from building structures made exclusively of reinforced concrete (RC) or structural steel toward hybrid structural solutions that combine multiple materials. Although RC has long served as the basis for high-rise construction in many countries, its limitations become more evident as the height of a building increases: oversized member sections reduce usable floor area, excessive self-weight amplifies seismic demand, and foundations must be designed to resist larger loads. Hybrid configurations have been developed to address these challenges, in which RC core walls are typically used for stiffness and strength and are combined with steel or composite members [

1]. This combination of materials reduces overall weight, accelerates construction, and enhances adaptability for future modifications while maintaining cost advantages over single-material systems [

2]. From a theoretical perspective, the reliable application of such systems depends on advances in analytical and numerical methodologies capable of efficiently capturing dynamic processes in complex, heterogeneous structural systems, particularly under seismic loading. A recent study has proposed improved computational strategies for dynamic analysis of elastic elements in complex engineering constructions [

3]. In parallel, increasing attention to environmental protection and sustainability, shaped by national legal frameworks and international policy discourse, has further encouraged the adoption of hybrid solutions that balance structural performance with reduced material consumption and environmental impact [

4].

In practice, buildings that make use of RC and steel are becoming increasingly common. However, the design of a hybrid structure based on these materials is often governed by engineering judgment rather than codified standards, and systematic investigations into the seismic performance of such constructions remain limited [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Zhang et al. [

9] carried out shaking table tests to demonstrate that confined masonry components in hybrid masonry–RC buildings tend to fail earlier than RC members, and may trigger progressive collapse. Their findings highlight the need to reassess design assumptions that often lead to underestimates of the structural contributions of masonry. Complementary studies of hybrid masonry–RC systems conducted by Abrams et al. [

10] revealed that connection detailing, anchorage configuration, and force transfer mechanisms are essential aspects of stable seismic performance; if properly designed, hybrid systems of this type can achieve resilience comparable to that of conventional structures. Zheng et al. [

11] extended this work by examining RC–masonry horizontal hybrids, which are common in rural China, and by showing that torsional irregularities and uneven stiffness distributions can exacerbate seismic vulnerability. Their combined shaking table and finite element analyses provided valuable insight into story drift patterns and stress concentrations at beam–column interfaces.

Subsequent studies have broadened the scope of investigations into hybrid or mixed-material structures. Kiani et al. [

12,

13] evaluated how the height and position of the transition story in buildings with RC bases and steel tops affect the fragility of mixed multistory frames, while Ghanbari et al. [

14] examined its performance under sequential mainshock–aftershock excitations, and evaluated the possibility of cumulative damage effects. Askouni and Papagiannopoulos [

15,

16,

17,

18] explored the dynamic response of three-dimensional mixed frames subjected to strong near-fault ground motions. Askouni [

2] carried out further investigations of hybrid buildings exposed to recurrent earthquakes, which included models of the lower RC portion of an existing structure supporting an upper steel framework, an arrangement that is often used in retrofit or vertical extension projects. Li et al. [

19] proposed a simplified analytical approach for estimating the lateral demand in mixed systems, whereas Kaveh and Ardebili [

20] introduced an optimization-based framework for enhanced cost efficiency. Building on these efforts, Kiani et al. [

21] recommended seismic factors for concrete–steel composite buildings, and Pnevmatikos et al. [

22] applied wavelet analysis to detect damage to planar mixed frames. Similarly, Maley et al. [

23] confirmed that conventional design methods can be applied to frames with vertical material transitions, despite such configurations not being explicitly covered in existing codes. Fanaie and Shamlou [

24] assessed response modification factors for various mixed frames, while Bhattarai and Shakya [

25] investigated response reduction factors for steel–RC systems.

Recent research has commenced to explore hybrid mechanics–data-driven modeling strategies to enhance response prediction while preserving physical interpretability. Shahmansouri et al. [

26] introduced a scaling-based integrated machine learning–mechanics framework for assessing the lateral response of self-centering RC walls. This study, while concentrating on self-centering wall systems instead of mixed-material buildings, illustrates an emerging class of hybrid modeling approaches that may complement physics-based numerical simulations and motivate future extensions in modeling frameworks for complex hybrid structural systems.

Taken together, these studies represent a growing research effort to define analytical tools, design methodologies, and performance assessment frameworks for hybrid structures, and highlight the need for physical evidence on the dynamic responses of such frameworks. Of the various hybrid configurations that have been developed, wall-dominated systems have gained prominence for their ability to combine control deformation and damage in seismic buildings [

27]. In these systems, RC or steel–RC core walls act as the primary lateral-resisting elements, creating a concentration of stiffness and strength near the center of the building. The surrounding steel frames, typically with simple or moment connections, primarily act to support gravitational loads, while floor diaphragms act as collectors that unify the global structural response. For taller buildings, belt trusses or outriggers are often introduced to enhance the interaction between the steel framing and the core wall, in order to further reduce lateral deformation.

Although hybrid wall systems have been shown to yield reliable seismic performance, they continue to pose challenges in terms of both design and analysis. Careful detailing is essential to accommodate inelastic deformation in critical regions, as is a consideration of how coupling beams, floor slabs, and steel frame components influence the stiffness, strength, drift, and failure mechanisms. In steel–RC walls, special attention must be paid to anchorage, the interaction between steel and concrete, and local confinement in order to prevent premature failure. The behavior of the coupling beams, whether composed of RC or structural steel, strongly governs the lateral stiffness and the transfer of shear and axial forces between wall segments, meaning that proper configuration and connection detailing are important. The connections between structural steel and RC elements also require special attention, and evidence is needed in order to judge the current ability of designers to estimate drift, damage, and repairability. Nevertheless, seismic design provisions are primarily focused on single-material systems, such as RC, timber, or steel, and provide limited guidance for hybrid configurations [

28].

As hybrid structural systems become increasingly prevalent in contemporary construction, the lack of dedicated design provisions highlights the need for systematic, system-level investigations that clarify their seismic behavior and support damage-control and resilience-oriented design strategies. To address this need, the present study focuses on a wall-dominated hybrid structural steel–RC coupled wall system, a configuration that has received comparatively limited experimental and analytical attention in prior research, which has largely emphasized vertically transitioned hybrid buildings. Through a comprehensive nonlinear analytical investigation of a full building system, this study examines how global seismic response, force-sharing mechanisms, and deformation demands develop at the system level, providing preliminary yet essential insight into these behaviors. The research was conducted through an international collaboration between the National Center for Research on Earthquake Engineering (NCREE) at the National Institutes of Applied Research (NIAR), Taiwan, and the New Zealand Centre for Earthquake Resilience Te Riranga Rū QuakeCoRE, with support from National Taiwan University (NTU), National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), the University of Canterbury, and the University of Auckland.

The study described the selection and scaling of input ground motions and included nonlinear dynamic simulation results obtained using ETABS. Nonlinear hinge properties followed TEASPA and ASCE guidelines, and appropriate boundary conditions were used to represent the expected deformation behavior of the hybrid system. The aim of this investigation was to produce tangible data on the measured seismic response of hybrid structures, in order to support design methods with a focus on the control of seismic drift and damage, to expedite building reuse. In addition, the paper outlines a large-scale experimental program that is planned to verify the analytical findings introduced here. By documenting both numerical modeling results and test planning for a hybrid steel–RC coupled wall system, this study will provide the research and engineering communities with a valuable reference to support the implementation of resilient hybrid structures.

2. Methodology

2.1. Steel–RC Hybrid System Under Study

Collaborative initiatives between the NCREE in Taiwan and New Zealand’s Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE have laid important groundwork for extending the current knowledge of the seismic performance of whole buildings. Earlier joint studies focused on mid-rise RC frame buildings with torsional irregularities, which are typical of existing structures in Taiwan and New Zealand [

29]. Subsequent programs under QuakeCoRE extended this exploration to low-damage systems, and included a two-story concrete-wall building and an ongoing investigation of a three-story steel structure incorporating a friction-based energy dissipation system. Complementary efforts by E-Defense in Japan and the University of California San Diego (UCSD) have further enriched the state of the art through large-scale shaking table tests of concrete, steel, and timber buildings [

30]. Together, these projects have provided significant insight into how entire structures respond to seismic excitation, but further investigation remains essential to evaluate the performance of emerging hybrid systems that combine multiple materials and lateral force mechanisms.

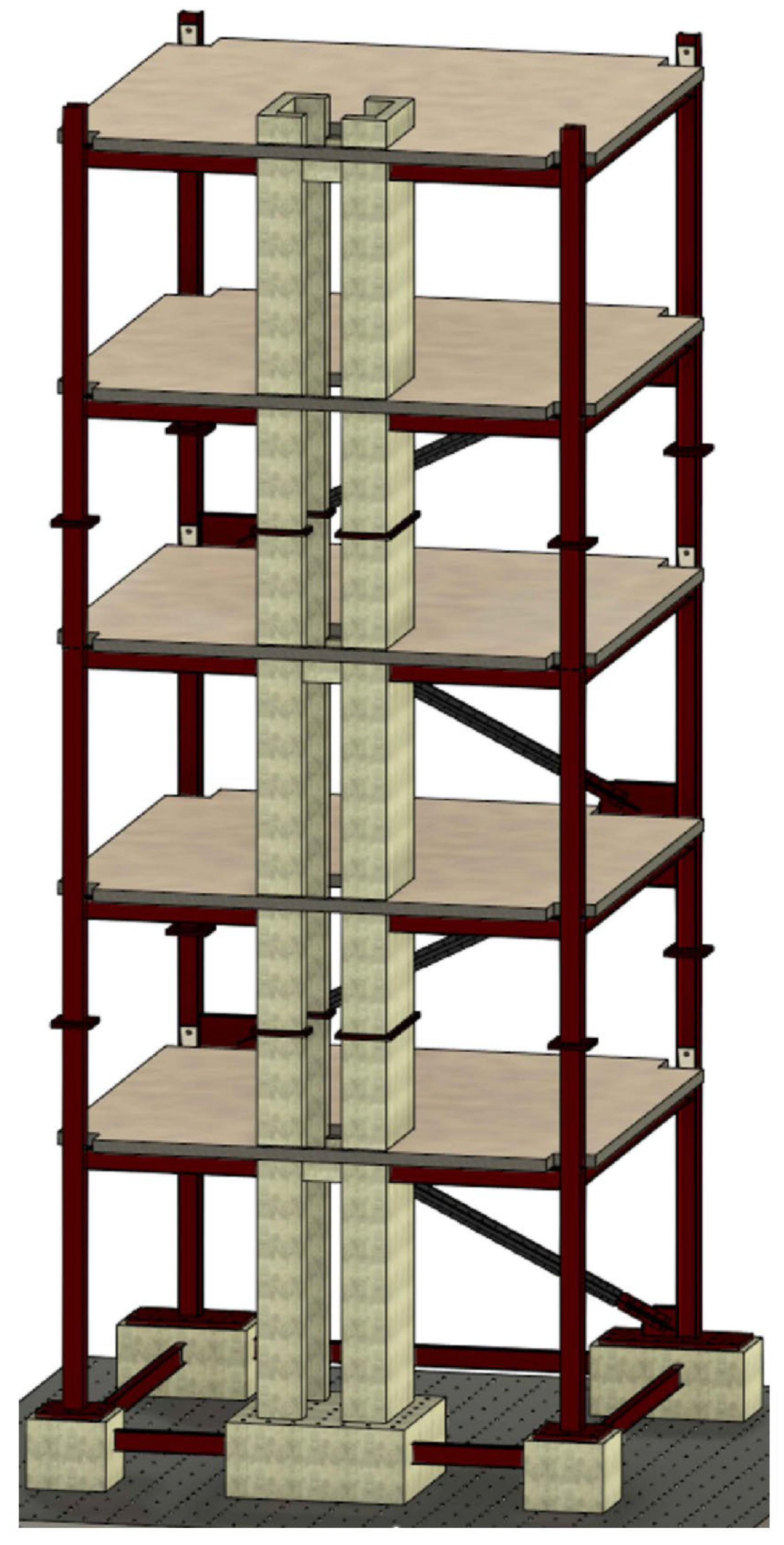

Building upon this international foundation, the present NCREE–QuakeCoRE collaboration developed a hybrid structural steel–RC coupled wall system that represents current practice in New Zealand and can be adapted to Taiwan’s high-seismic environment. The proposed prototype, shown in

Figure 1, integrates structural steel framing with RC coupled-core walls to form a composite lateral resisting system. In this design, there is an emphasis on drift control, ductility, and post-earthquake repairability, in order to meet the broader objective of enhancing seismic resilience and “functional recovery”. In conceptual terms, the prototype represents a mid-rise five-story office building located in Christchurch, which was chosen as a reference for structures in regions of moderate to high seismic hazard.

The test structure features a 5 × 5 m floor plan, defined by centerline-to-centerline dimensions, with an overall height of 12.7 m. It includes two coupled walls that form a core offset from the center of mass. The ratio of the cross-sectional area of the wall to a typical gross floor plan area is 0.023. Coupling beams are located at three (out of five) levels above the foundation, to limit the base shear strength within the capacity of the earthquake simulator.

To allow the torsional response to be explored, buckling-restrained braces can be installed or removed from a frame that is located opposite to the wall and furnished with moment connections placed on alternate floor levels. In the direction perpendicular to the braces, there are steel frames that feature slotted, bolted shear tabs that connect beams to columns and wall segments. Concrete slabs cast on steel-deck panels serve as floors and diaphragms. Depending on the friction at the bolted steel connections, the coupling between the slabs and shear tabs can induce moment transfer at connections that are often assumed not to resist moments.

The structure was built in three modules, which were connected by two splices consisting of pairs of bolted plates, as illustrated in the three-dimensional model in

Figure 2. Steel reinforcing bars and structural steel shapes were welded with full-penetration welds to the splice plates. The specified concrete compressive strength was 40 MPa, and ASTM 706 Grade 60 (

fy = 410 MPa) was selected for all concrete reinforcements. SS400A steel was selected for all structural steel components, including BRBs and gusset plates. The specified yield stress was 205 MPa, and the specified tensile strength was 400 MPa.

The building included nonstructural elements (office furniture, partitions, veneer, library shelves, sprinklers, and a curtain wall, amounting to approximately 1 kPa of added weight per floor except at roof level). The testing program included three phases: (i) without the buckling-restrained braces; (ii) with the braces installed to control torsion; and (iii) without the braces again. In the last phase, a partial curtain wall was installed along the facade accommodating the braces in Phase II. The total building weight, excluding footings, ranged between 730 and 750 kN depending on the configuration (i.e., testing phase). The distribution of building weights for each phase, including nonstructural components, is presented in

Table 1.

Estimated initial periods associated with the first translational modes ranged between 2/5 and 2/3 s, depending on the direction, configuration, and assumptions about the ability of the connections to resist moments. Again, the proportions of the structure were adjusted to keep the demand on the shaking table within its specifications. In the configuration with braces, the prototype was designed to reach a roof drift ratio that did not exceed approximately 1%. The reference (or design) earthquake was represented by a displacement spectrum reaching 200 mm for a period of 1 s and a damping ratio of 2%. At a damping ratio of 5%, the spectrum reaches approximately 150 mm at 1 s. These ordinates correspond to spectral accelerations of approximately 0.8 g and 0.6 g at 1 s, and a peak ground velocity approaching 0.4 m/s. The minimum design base-shear strength coefficients ranged between 1/8 and 1/4, depending on the configuration.

2.1.1. Design of Sandwiched Buckling-Restrained Brace

The braces incorporated into the building were sandwiched buckling-restrained braces (SBRBs), as illustrated in

Figure 3. Their design followed procedures outlined in previous studies [

31,

32], and consisted of a rectangular core plate and two identical restraining members, which were built by welding a steel channel to a rectangular face plate. Cross-sectional dimensions for each SBRB are summarized in

Table 1. The restraining members were bolted together using M14 S10 high-strength bolts, where the distance between bolts was selected to avoid local and global buckling along the yielding length of the core plates. A silicone layer 2 mm thick was installed around the core plate to avoid friction with the restraining members.

To achieve the desired deformation performance, additional refinement was applied to the core plate and restraining components. The dimensions of the stiffener and the slit spacing on the face plates were adjusted to ensure that the core could undergo axial deformation without premature buckling. This tuning process enabled the braces to reach the target strain capacity while maintaining stable hysteretic behavior under cyclic loading. In this study, all four SBRBs were designed to sustain axial core strains exceeding 4.5%, in order to confirm their ability to provide reliable energy dissipation and consistent mechanical performance under simulated seismic demand. In this design approach, the SBRBs were expected to exhibit stable load–deformation characteristics and to contribute significantly to the overall seismic resilience of the hybrid structural system. Once these requirements had been met, the SBRB design was finalized, and the corresponding geometric and mechanical properties are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

2.1.2. Design of the Coupled Wall

The RC coupled wall consisted of two opposing C-shaped walls linked by coupling beams at three levels, as illustrated in

Figure 4. Each C-shaped wall was based on a combination of a web and two flange panels, as shown in

Figure 5a.

The core wall was designed to yield in flexure, without shear or bond failures. For anchorage, longitudinal wall bars were welded to plates placed at the bottom of the wall footing. The maximum shear demand was estimated using the likely properties of the material to enable an estimate of the moment capacities. An effective lever arm equal to 50% of the wall height was used to estimate the peak wall shear demand. The peak nominal unit shear stress estimated for the product of net wall length and web thickness was kept below 2 MPa. To estimate the peak shear in the direction of the coupling beams, a mechanism with plastic hinges was assumed to occur at all beam faces and wall bases, whereas in the perpendicular direction, hinging was assumed to occur exclusively at wall bases.

The boundary element (BE) regions, identified as Zones 1 through 4 in

Figure 5b, were confined to enhance the deformation capacity of the concrete. The volumetric reinforcement ratios calculated for the concrete within confining hoop centerlines ranged from 1.11% to 1.98%. Excluding the hoop reinforcement, the continuous transverse reinforcement placed in the coupling wall web (CW web) and flange panels provided transverse reinforcement ratios between 0.89% to 1.58%. Ties were expected to be able to resist the entire shear force, without contributions attributable to the concrete. The total longitudinal reinforcement ratio was 1.60%. In the boundary elements, the longitudinal reinforcement ratios were 2.02% on the long-web side (BE

1 and BE

3) and 2.21% on the short-web side (BE

2 and BE

4).

2.1.3. Design of the Coupling Beams

Each coupling beam had a span of 400 mm, an overall depth of 240 mm, and a span-to-depth ratio of 1.67, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The beam width was 200 mm, matching the width of the adjacent wall segments. The diagonal reinforcement consisted of #4 bars placed at an inclination of 20°, allowing the strength of the steel bars to be mobilized under diagonal tension. The diagonal bars were provided with headed anchors and embedment lengths of 30 times the bar diameter. The horizontal longitudinal reinforcement was not intended to yield under tension, and consisted of a total of six #6 bars with short embedment lengths of 15 times the bar diameter. The transverse reinforcement ratio provided by the stirrups was approximately 0.7%.

The coupling beams were confined with closed hoops and cross-ties made from #3 bars. The spacing of the ties (80 mm) did not exceed one-quarter of the beam depth or six times the diameter of the longitudinal bars, and one hoop was positioned within 50 mm from the wall face to improve confinement near the interface. The reinforcement detailing and member dimensions were chosen to ensure that the expected chord rotation under the reference (or design) earthquake does not surpass 3.5% or the rotational capacity observed in tests of similar beams, noting that a greater span-to-height ratio may result in increased beam chord rotation [

33].

2.2. Selection of Input Ground Motion

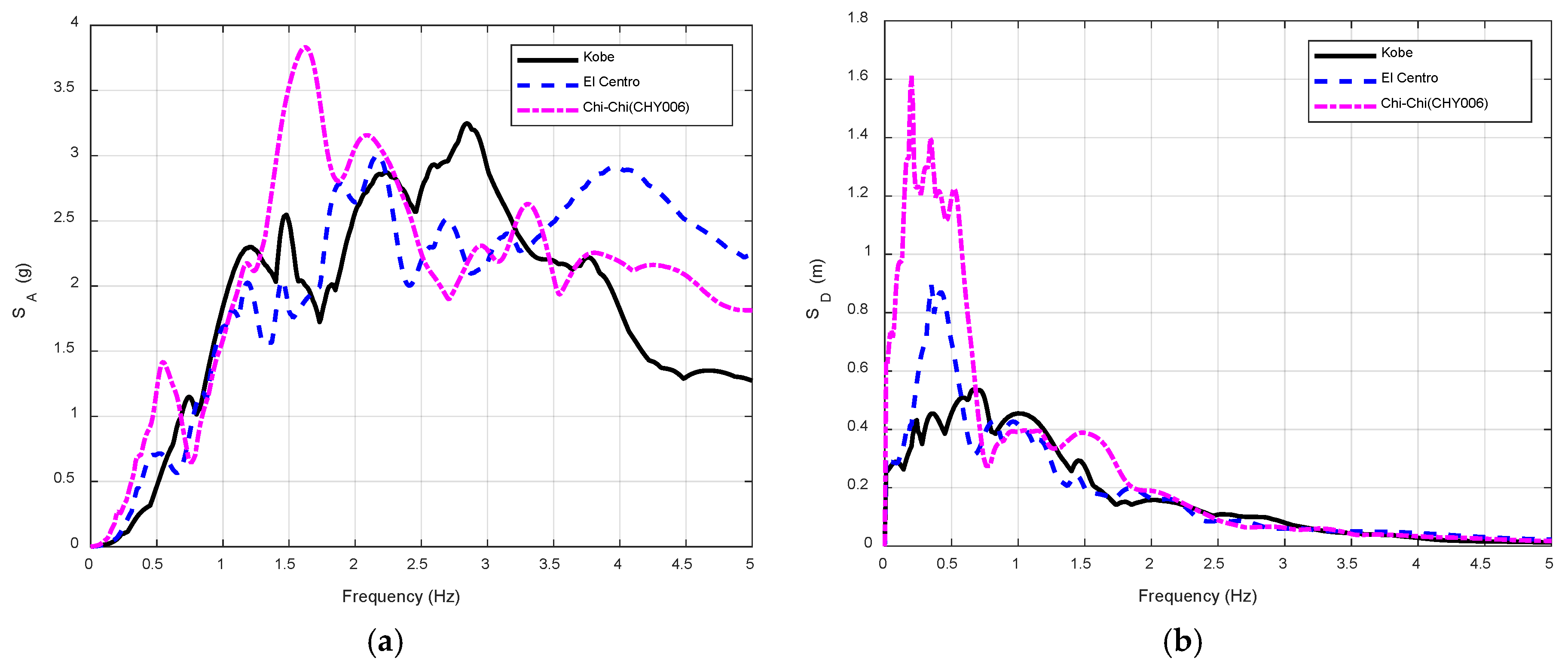

The primary objective of this analytical model was to investigate the torsional behavior of a hybrid lateral-resisting system composed of steel and RC elements. To achieve this, the principal direction of seismic excitation was defined as the direction parallel to the SBRBs. The ground motion records were scaled to match the design spectra over the range of periods relevant to the system (0.4 to 1.5 s). The ground motion was further scaled to represent multiple seismic hazard levels, where R = 0.25 corresponds to serviceability-level shaking, R = 0.5 to the repairable level, R = 1.0 to the design-basis earthquake (DBE), and R = 1.5 or higher to the maximum considered earthquake (MCE). This multi-level scaling approach enabled a comprehensive evaluation of the structural response under a wide range of seismic demand, including both elastic behavior and highly nonlinear deformation regimes.

Three components of recorded ground motions were considered for reference: the EW component of the 1995 Hyogo-ken Nanbu (Kobe) earthquake recorded at the JMA station, the EW component of the 1940 Imperial Valley earthquake recorded at Array #6, and the EW component of the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake recorded at the CHY006 station. Of these, the Chi-Chi CHY006 record was selected as the primary input motion for the nonlinear dynamic analyses, while the Kobe and Imperial Valley records were retained for comparative purposes to highlight differences in spectral shape and frequency content.

Figure 7a–c present the corresponding acceleration time histories, and

Figure 8 shows the 5%-damped response spectra after scaling. In particular, the scaled Chi-Chi CHY006 spectrum exhibits close agreement with the target design spectrum prescribed by NZS 1170.5 [

34] over the period range of interest for the prototype structure (approximately 0.4–1.5 s), with spectral ordinates generally within an acceptable deviation for nonlinear time-history analysis. This range encompasses the fundamental and higher-mode periods of the hybrid coupled wall system, ensuring consistency between the selected input motion and the governing seismic hazard.

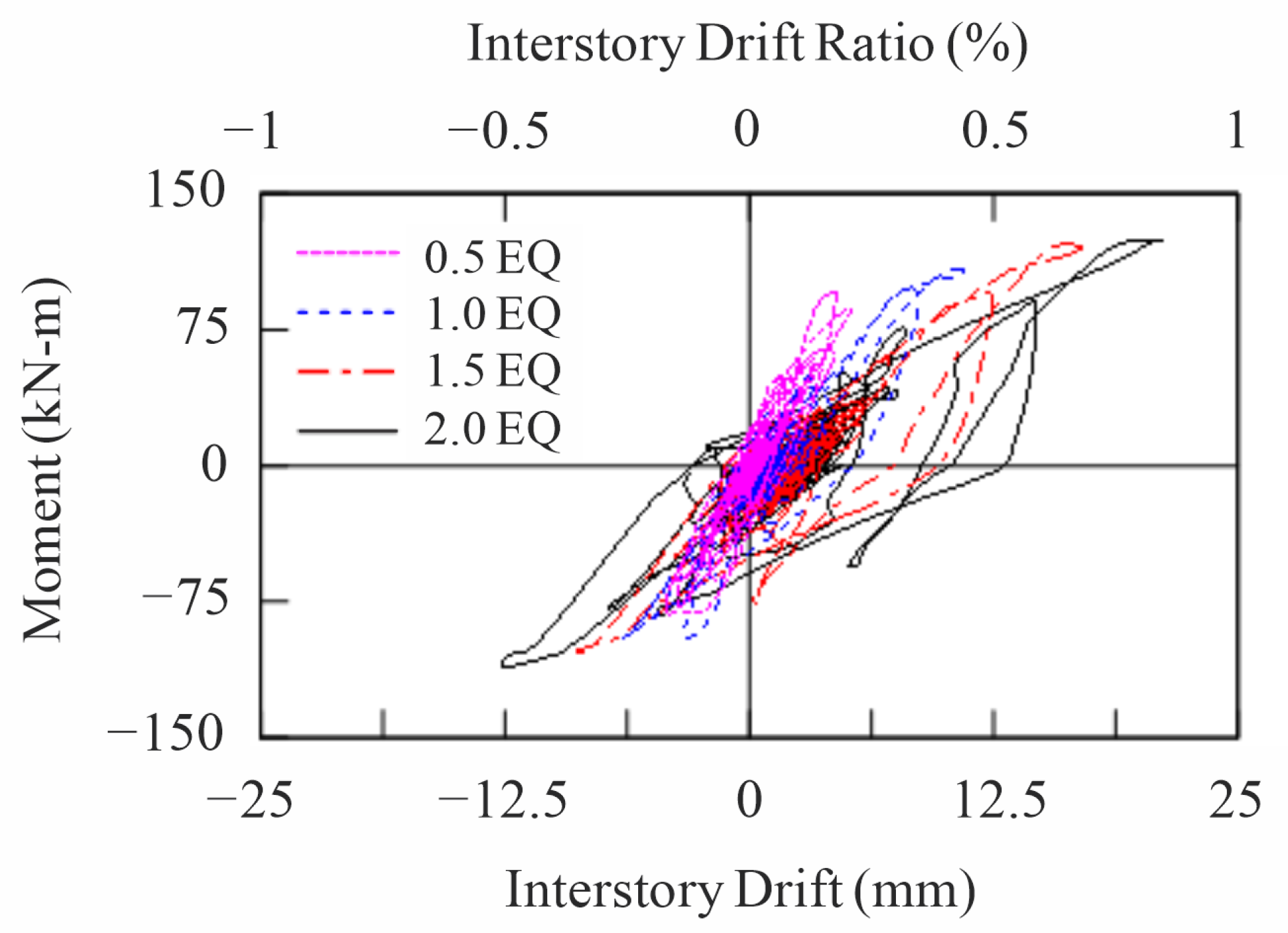

The Chi-Chi CHY006 motion is characterized by pronounced long-period pulse-like features, as reflected by its relatively high spectral displacement in the low-frequency range (approximately 0.2–0.5 Hz), which makes it particularly suitable for evaluating wall-dominated hybrid systems. Such pulse-like motions are known to impose large displacement and rotation demands and are therefore critical for assessing torsional response, force redistribution between RC walls and steel framing, and coupling-beam deformation demands. The EW component was selected because it produces the most significant structural response relative to the principal horizontal axes of the building, consistent with standard practice in performance-based seismic assessment. The applied scaling factors of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 represent increasing intensity levels that may be interpreted as serviceability, design-basis, and beyond–design-basis to near-collapse conditions for the considered site and structural system, enabling a systematic evaluation of response progression under escalating seismic demand.

2.3. Numerical Modeling

To verify that the analytical model could accurately reproduce the intended structural behavior, a series of nonlinear dynamic analyses were performed, with a focus on evaluating the global and torsional responses of the proposed hybrid structural system under near-fault excitation. As described above, the ground motion recorded during the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake (station CHY006) was used for the dynamic analysis.

Furthermore, as a preliminary investigation of the system response, the model used the design material properties. The concrete in the wall and the coupling beams used a design compressive strength

of 30 MPa, while the reinforcing bars in these members used a design yield strength

of 420 MPa, values that were representative of common construction practice in New Zealand. The steel columns and beams were modeled using the standard structural steel grade SN400 [

35], with a minimum design yield stress

and tensile strength

of 205 MPa and 400 MPa, respectively. The elastic moduli adopted for concrete

and steel

were 20.8 GPa and 200 GPa, respectively. Nonlinear behavior was represented by hinge properties assigned to the structural elements, and the detailed definitions of these hinges are presented in the following subsection. The outline of the modeling assumptions and setup, including material properties, section dimensions, and the configuration of the buckling-restrained braces, as summarized in

Table 4.

2.3.1. Basic Modeling Settings

In the analytical model, the X-direction was defined as the axis of the SBRB, and corresponded to the short direction of the RC core wall, while the Y-direction represented the long direction of the wall. Beam and column elements were modeled using their actual cross-sectional dimensions, to ensure accurate representation of the stiffness. The RC core wall was idealized using the equivalent wide-column approach described in TEASPA 4.0, in which the wall is represented by two boundary columns connected by a cross-shaped linking member. The equivalent wide columns were assigned their actual dimensions with a web and coupling beam width of 200 mm, and elastic end regions were defined at both ends of the wall columns, as shown in

Figure 9.

To simulate realistic boundary conditions, pinned connections (representing hinged behavior) were used at the interfaces where the steel beam ends meet the RC-wall joints, reflecting the absence of fully connected top and bottom flanges. Meanwhile, the steel columns and the RC wall boundary elements were constrained using fixed joints at the base, as shown in

Figure 9c,d. The panel zones at these joints were modeled as rotational springs, with values for the elastic shear stiffness derived from the geometry and material properties of the actual joint section. The applied loads followed the planned testing conditions: in addition to the self-weight of the structural members, all other vertical loads (representing nonstructural components such as equipment and furnishings) were applied as uniformly distributed loads on each floor slab. For the modal analysis, both the self-weights of the members and the additional vertical loads were treated as static loads, and were incorporated into the mass matrix of the analytical model.

2.3.2. Nonlinear Hinge Settings

Nonlinear hinge properties were incorporated into the analytical model for each primary structural component, in order to represent the expected inelastic response under seismic loading. To simplify the analysis and to reduce the computational effort involved, the number of hinges was minimized as far as possible without compromising the accuracy of the global response. The steel columns were assigned axial-flexural hinges, although in reduced quantity compared with a fully detailed model, while the steel beams were provided with flexural hinges in the regions of the SBRB beam ends to capture plastic rotations under lateral loading. The RC wall, which was primarily designed to resist shear rather than moment-frame action, was modeled as a single vertical element with a shear hinge located at its base. The RC coupling beams were equipped with flexural hinges at both ends, and the SBRBs were modeled with axial hinges at their ends to represent inelastic tensile and compressive behavior.

The mechanical properties of these hinges were defined following established standards. For the steel members, the hinge properties were specified in accordance with ASCE 41-17 [

36], as illustrated in

Figure 10a,b. The flexural and shear hinges of the RC wall were defined using TEASPA 4.0, which incorporates key backbone parameters such as cracking and yield strengths, post-yield stiffness ratio, and strength degradation, as shown in

Figure 10c,d. Moreover, the plastic hinge length could be more accurately evaluated by considering the axial stress ratio and the coupling ratio of the coupled RC walls [

37]. The hinge characteristics of the RC coupling beam and SBRB also followed ASCE 41-17 provisions [

36], with backbone curves and rotation capacities appropriate for shear-dominated and axial-dominated members, respectively, as shown in

Figure 10e,f. To capture cyclic degradation and energy dissipation behavior, the Takeda hysteresis model was applied to RC members, whereas the kinematic hardening model was used for steel members. In summary, flexural hinges were assigned at the ends of members to represent plastic rotations, while shear or axial hinges were introduced at critical locations corresponding to the expected inelastic mechanisms.

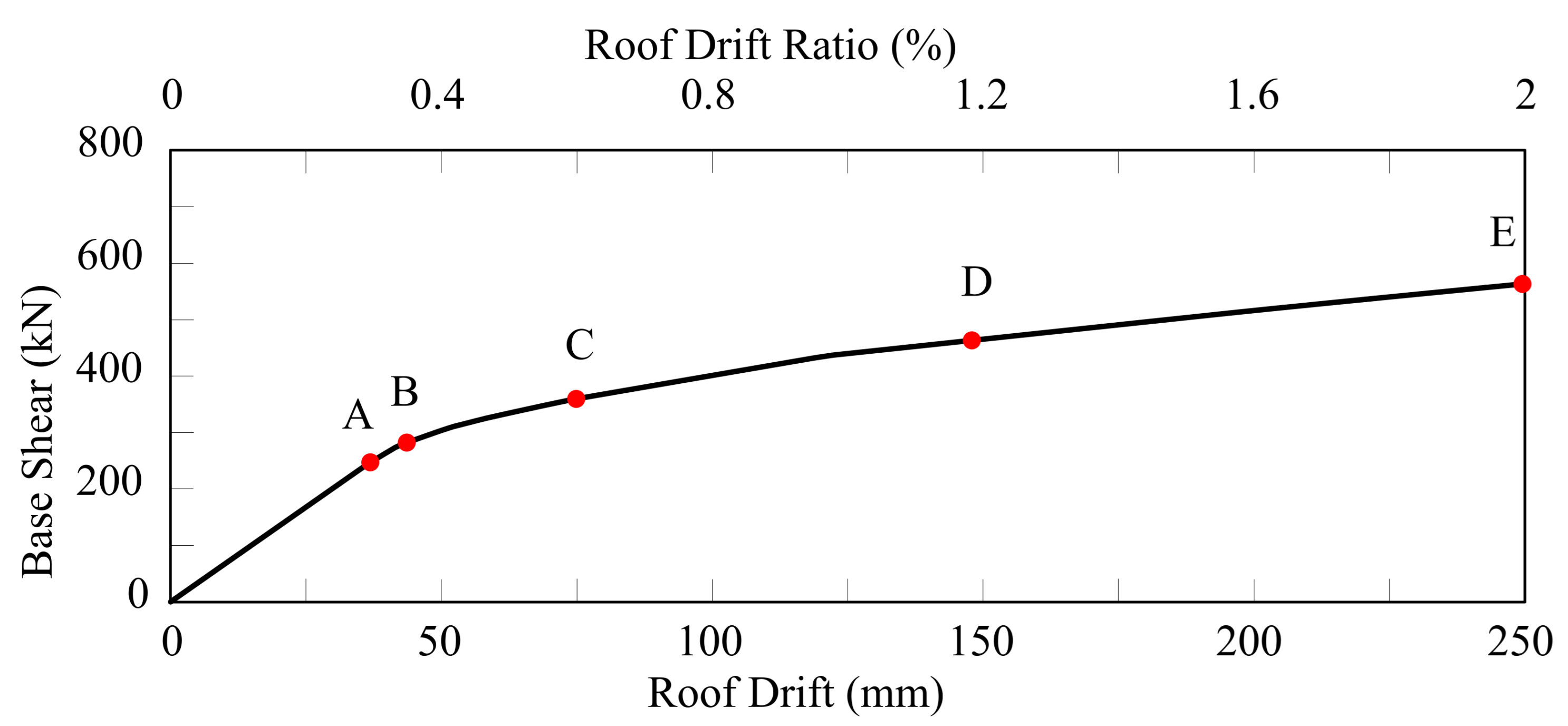

4. Limitations of the Numerical Model and Future Experimental Work

Table 6 presents a comparison between the numerical results and the corresponding allowable acceptance criteria specified in relevant design standards, providing a concise verification of the overall performance of the proposed hybrid structural system. While the analytical model captures the dominant global response characteristics and force-sharing mechanisms of the building, several simplifying assumptions were adopted to maintain computational efficiency and focus on system-level behavior.

Despite the satisfactory agreement with acceptance criteria shown in

Table 6, the RC walls were idealized using an equivalent wide-column representation, which may lead to localized underestimation or overestimation of stiffness and deformation demands, especially near regions of stress concentration. The use of a reduced number of nonlinear hinges, concentrated at predefined critical locations, limits the ability of the model to fully represent the spread of plasticity along members under severe seismic excitation. Panel zones and beam–column joints were modeled using simplified rotational springs, and the floor slabs were assumed to behave as rigid or very stiff diaphragms; these assumptions may influence the predicted torsional response and the distribution of interstory drift, particularly in configurations with asymmetric stiffness. Consequently, the sensitivity of drift demand and torsional behavior to joint stiffness and diaphragm flexibility is not explicitly resolved in the present numerical framework. These limitations highlight the need for complementary experimental investigation to validate the modeling assumptions and to capture local deformation mechanisms that are not fully represented in the analytical model.

A large-scale shaking table program will be undertaken at the NCREE Tainan Laboratory, Taiwan. This program has been designed to capture both the global and local response mechanisms of the hybrid steel–RC coupled wall structure when subjected to design-level excitations with strong motion. A total of 42 ground motion simulations will be performed. The input motions, derived from recorded earthquake data, will be carefully scaled to match the design response spectrum over the target period range of 0.4 to 1.0 s, corresponding to the fundamental vibration modes of the structure. The baseline design intensity is a ground motion characterized by a peak ground velocity (PGV) of 40 cm/s and a peak ground acceleration of 0.4 g. The selection criteria for the applied ground motion are based on two primary considerations: (i) the scaled peak ground acceleration, velocity, and displacement must remain within the operational capacity of the shaking table, and (ii) the spectral displacement should increase proportionally with the period, within the designated range of interest. Based on these requirements, the 1940 El Centro, California, earthquake record has been chosen as the principal input motion for most test sequences, complemented by three additional records representing different spectral characteristics. To explore varying levels of seismic demand, the amplitude of each motion will be scaled to intensity levels ranging from 25% to 150%, in 25% increments.

The experimental program will use the long-stroke, high-velocity earthquake simulator housed at the NCREE Tainan Laboratory, as shown in

Figure 23. This advanced facility features an 8 × 8 m shaking table with a 250-ton payload capacity, and is capable of generating three-dimensional broadband ground motions with high accuracy and control. The system can achieve horizontal and vertical strokes of ±1.0 and ±0.4 m, maximum velocities of 2 and 1 m/s, and peak accelerations of up to ±2.5 g horizontally and ±3.0 g vertically. These capabilities enable the realistic reproduction of design-level seismic demand, including both high-frequency acceleration pulses and long-period displacement components, thus ensuring that the structure experiences loading conditions consistent with those assumed in the numerical analyses.

For the experimental specimen, a modular construction system will be adopted that was specifically developed to facilitate transportation, assembly, and lifting operations within the laboratory. As illustrated in

Figure 24, this structure is divided into three detachable modules representing lower, middle, and upper segments, each of which is designed to represent a distinct structural zone while maintaining full continuity when assembled on the shaking table.

This modular approach allows the specimen to be transported efficiently from the fabrication area to the test platform, and then reassembled with precise alignment and minimal on-site adjustments. The modular joints are designed to ensure sufficient stiffness and continuity, thereby reproducing the intended global behavior while also simplifying the handling process during setup. Furthermore, this configuration offers the potential for reuse of the individual modules in future experimental phases, such as parametric studies or retrofit investigations, thus significantly improving research efficiency and resource utilization.

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the structural response, a detailed instrumentation system will be distributed across the specimen. Five accelerometers, as shown in

Figure 25, will be installed at each floor to capture both translational and rotational accelerations during shaking. These sensors will provide essential data for evaluations of the floor accelerations, interstory drift ratios, and dynamic amplification effects, which together describe the global seismic behavior of the hybrid structural system. In addition to the conventional accelerometers, a motion capture (MoCap) system will be incorporated to record the three-dimensional displacement field and torsional rotations with high precision. This enhanced instrumentation strategy will also enable direct measurement of critical local deformation parameters that were not explicitly resolved in the numerical analysis, including wall base curvature or rotation and coupling beam chord rotation, which are essential for detailed component-level performance assessment. This system will allow for continuous tracking of the absolute motion at critical points across the structure, offering an accurate visualization of its dynamic deformation patterns and enabling detailed comparison with analytical predictions.

The motion capture (MoCap) system will play an important role in achieving a detailed and reliable understanding of the dynamic behavior of the system. The overall configuration of the infrared cameras and marker layout that has been designed to achieve this objective is illustrated in

Figure 26 and

Figure 27.

Multiple infrared cameras will be used in conjunction with reflective markers mounted at key structural locations, such as the floor slabs, wall surfaces, and beam–column junctions. This arrangement will allow for continuous tracking of the three-dimensional displacements and rotations with high spatial accuracy, thus providing direct measurements of the structure’s absolute motion under seismic excitation. The data obtained from this system will be synchronized with accelerometer records to reconstruct the complete dynamic response of the structure, which will enable precise assessments of the modes of deformation, torsional effects, and overall stability. Capture of the full-field motion without physical contact will minimize measurement interference and significantly improve the fidelity of the experimental results.

The forthcoming shaking table experiment is expected to serve as an essential step in validating the numerical predictions presented in this study and advancing the current understanding of the seismic performance of the hybrid steel–RC wall system. The experimental results will enable a direct comparison between the analytical and measured responses, thus helping to verify the modeling assumptions and assess the accuracy of the nonlinear simulation techniques. In addition to confirming the predicted global response, this test will also provide valuable insight into the mechanisms governing energy dissipation, torsional interaction, and deformation concentration within the coupled wall and frame components. These findings are expected to deepen the understanding of how hybrid systems respond under strong earthquake excitations and to support the refinement of design parameters related to strength, ductility, and stiffness balance. Ultimately, the experiment will contribute to the development of more reliable performance-based seismic design methodologies and will promote the broader practical implementation of hybrid structural systems in regions of high seismic risk.