The Influence of Sand Ratio on the Freeze–Thaw Performance of Full Solid Waste Geopolymer Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Design

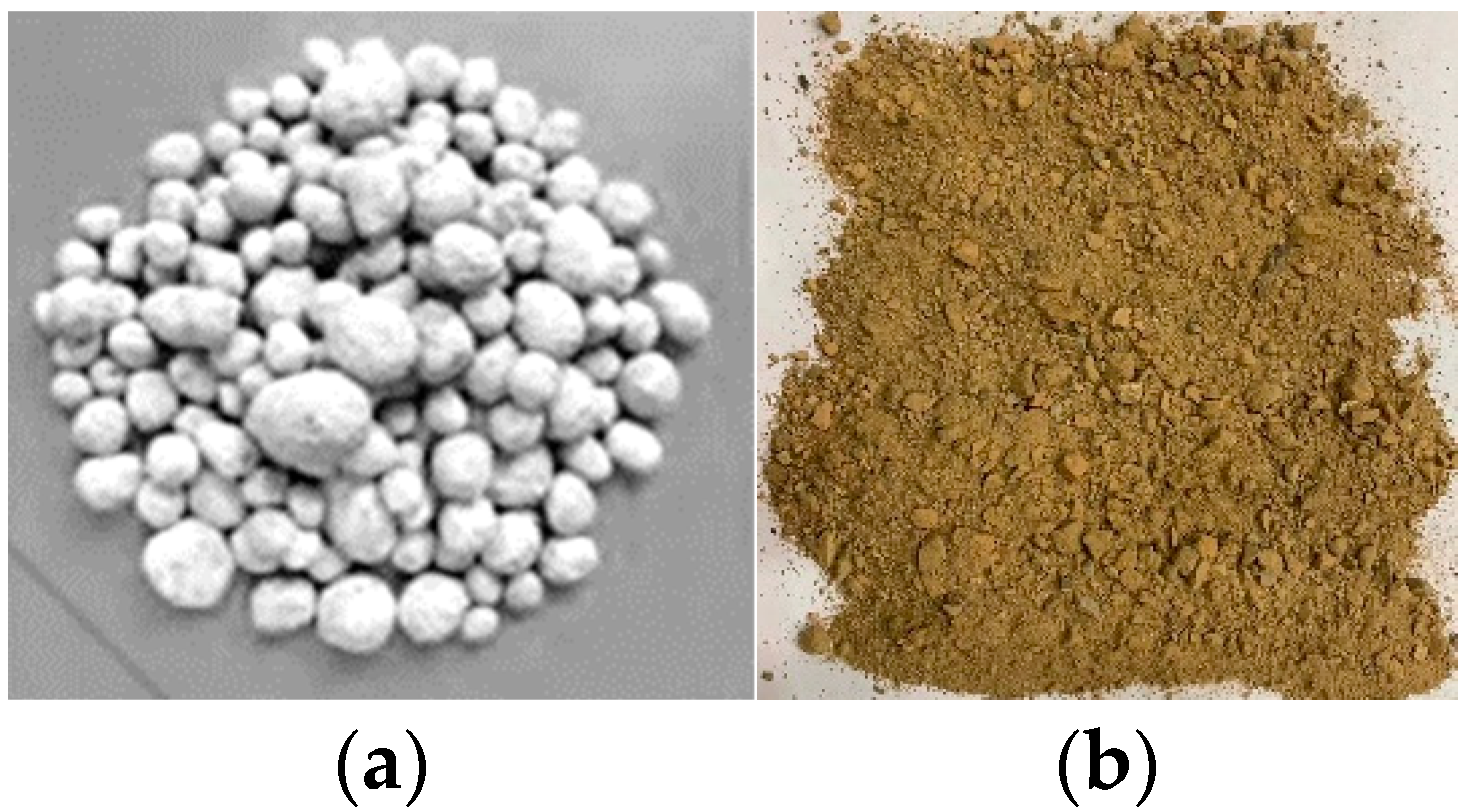

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportions

2.3. Specimen Preparation

2.4. Freeze–Thaw Testing

2.5. Mechanical Properties Test

3. Results and Analysis

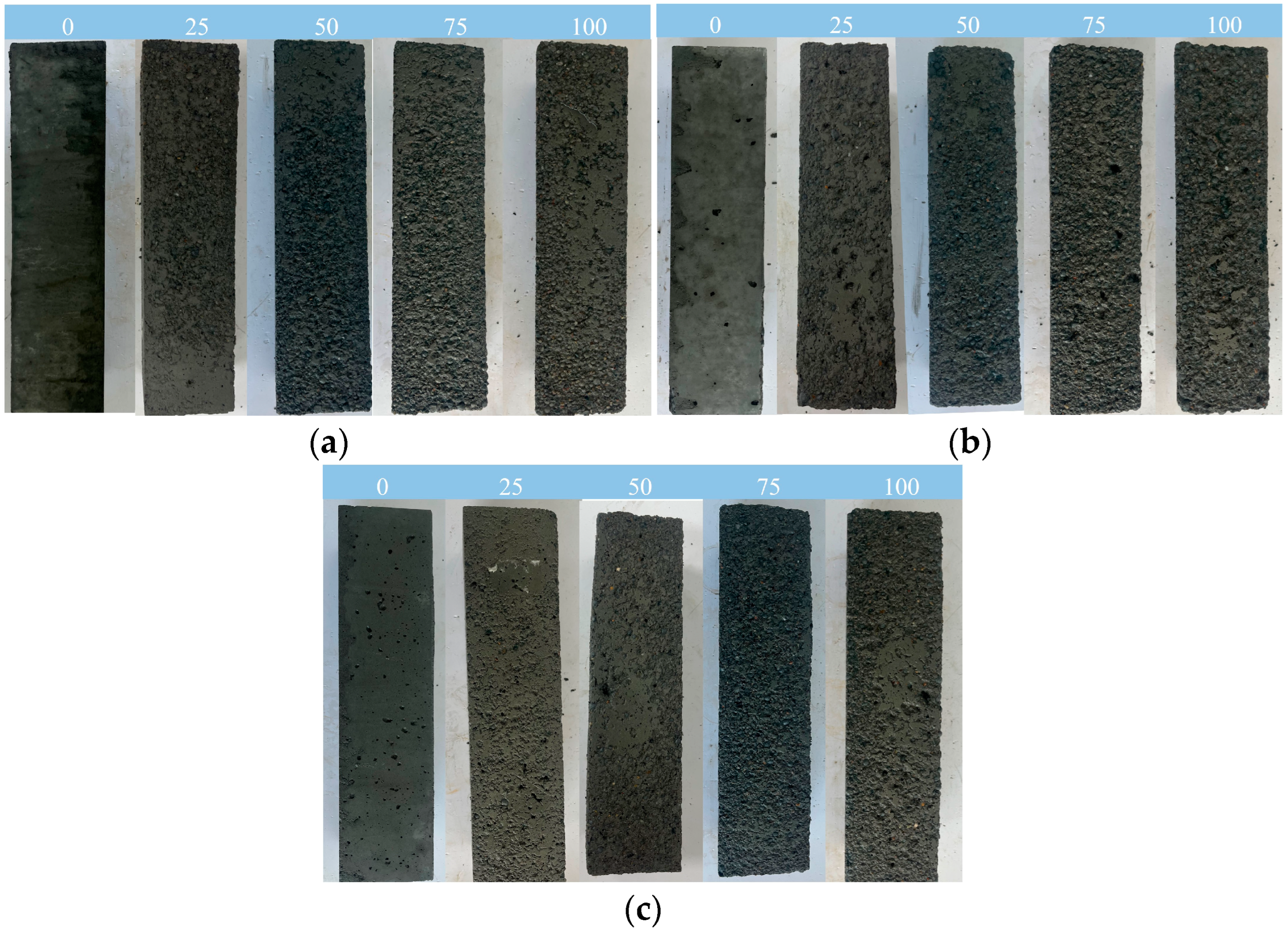

3.1. Mass Loss and Morphological Damage

3.2. Relative Dynamic Elastic Modulus

3.3. Mechanical Properties Degradation

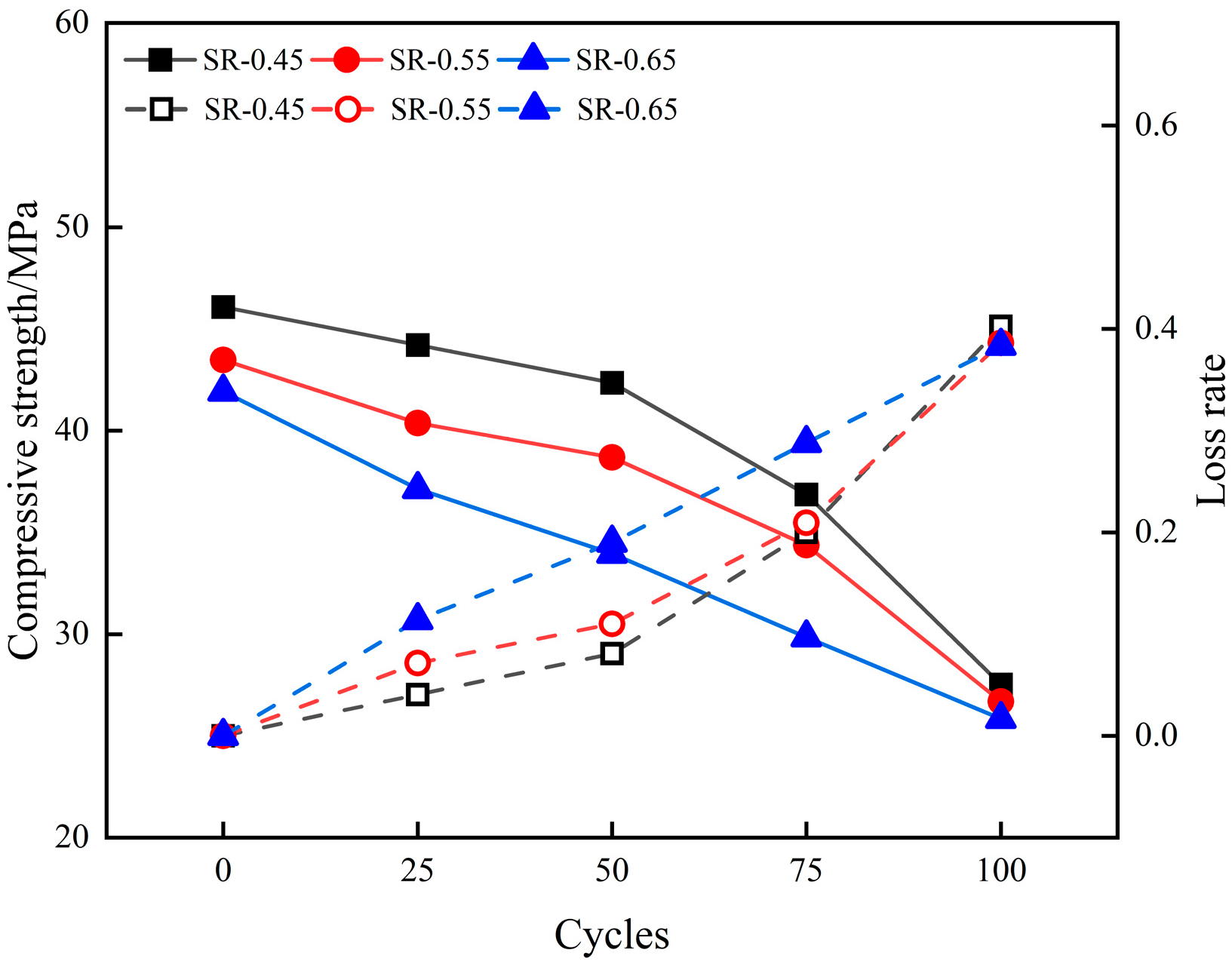

3.3.1. Compressive Strength

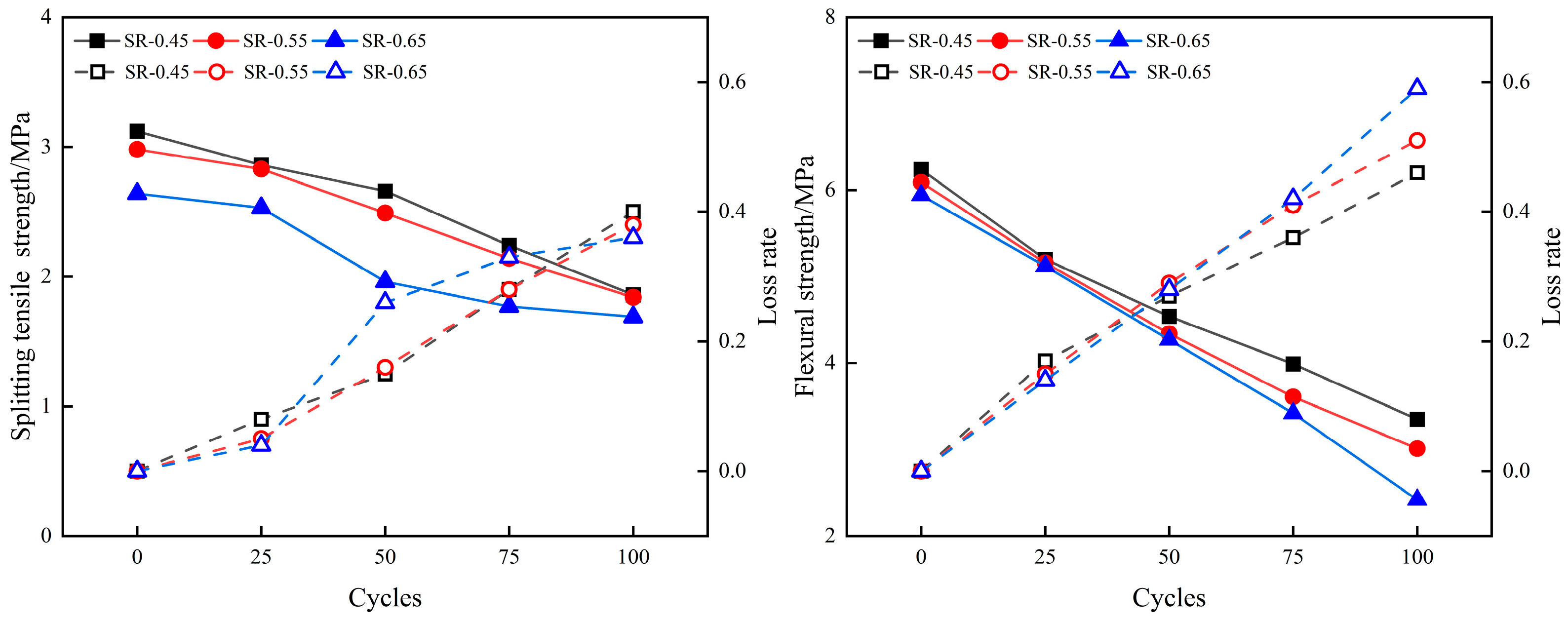

3.3.2. Splitting Tensile and Flexural Strength

3.4. Axial Compression Performance

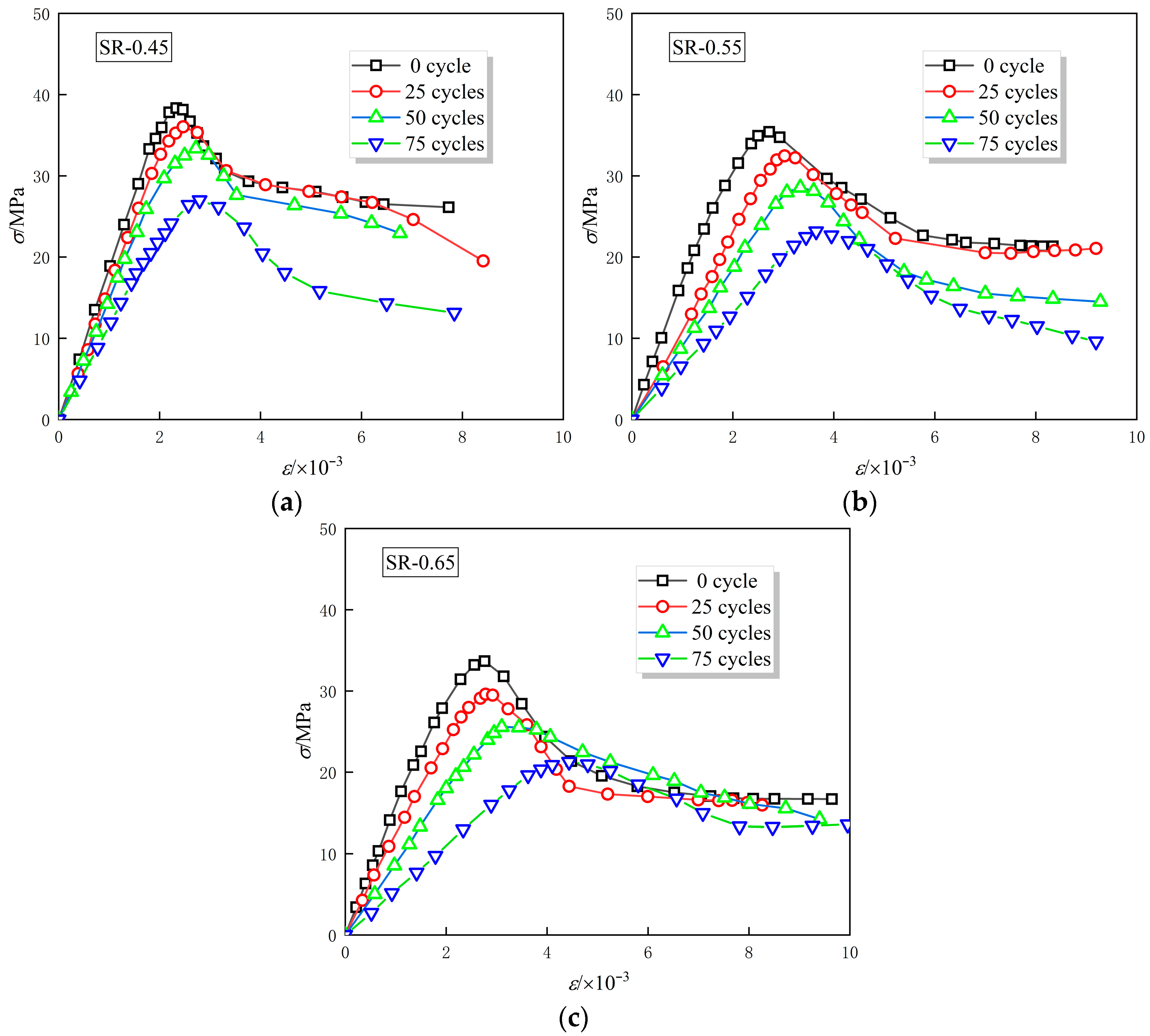

3.4.1. Stress–Strain Curve

3.4.2. Elasticity Modulus

3.4.3. Peak Stress

3.4.4. Peak Point Strain

4. Uniaxial Compression Constitutive Model

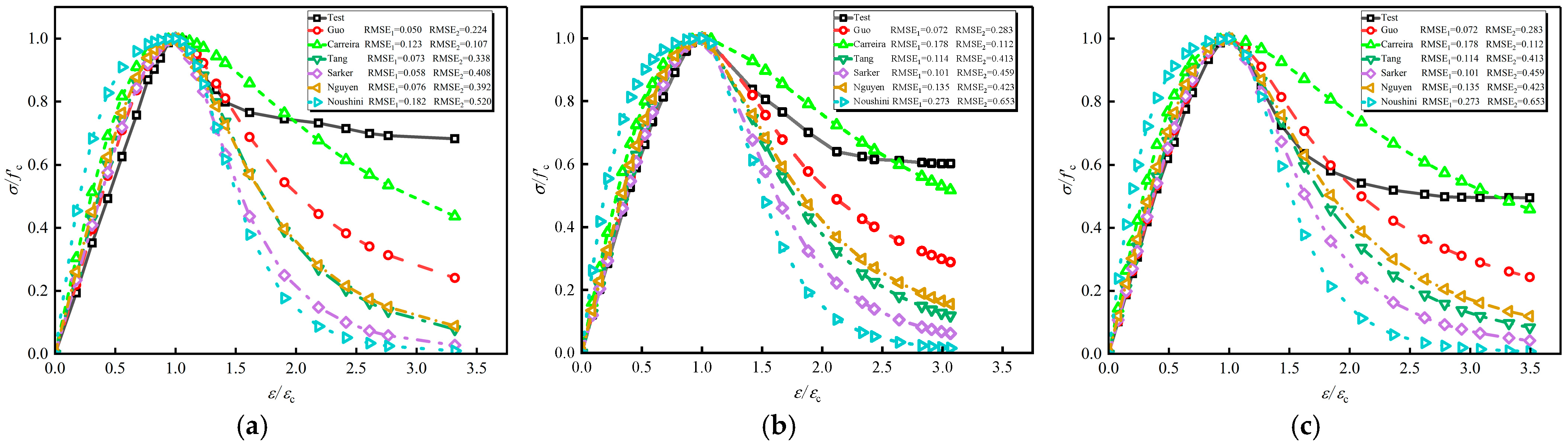

4.1. Classic Model

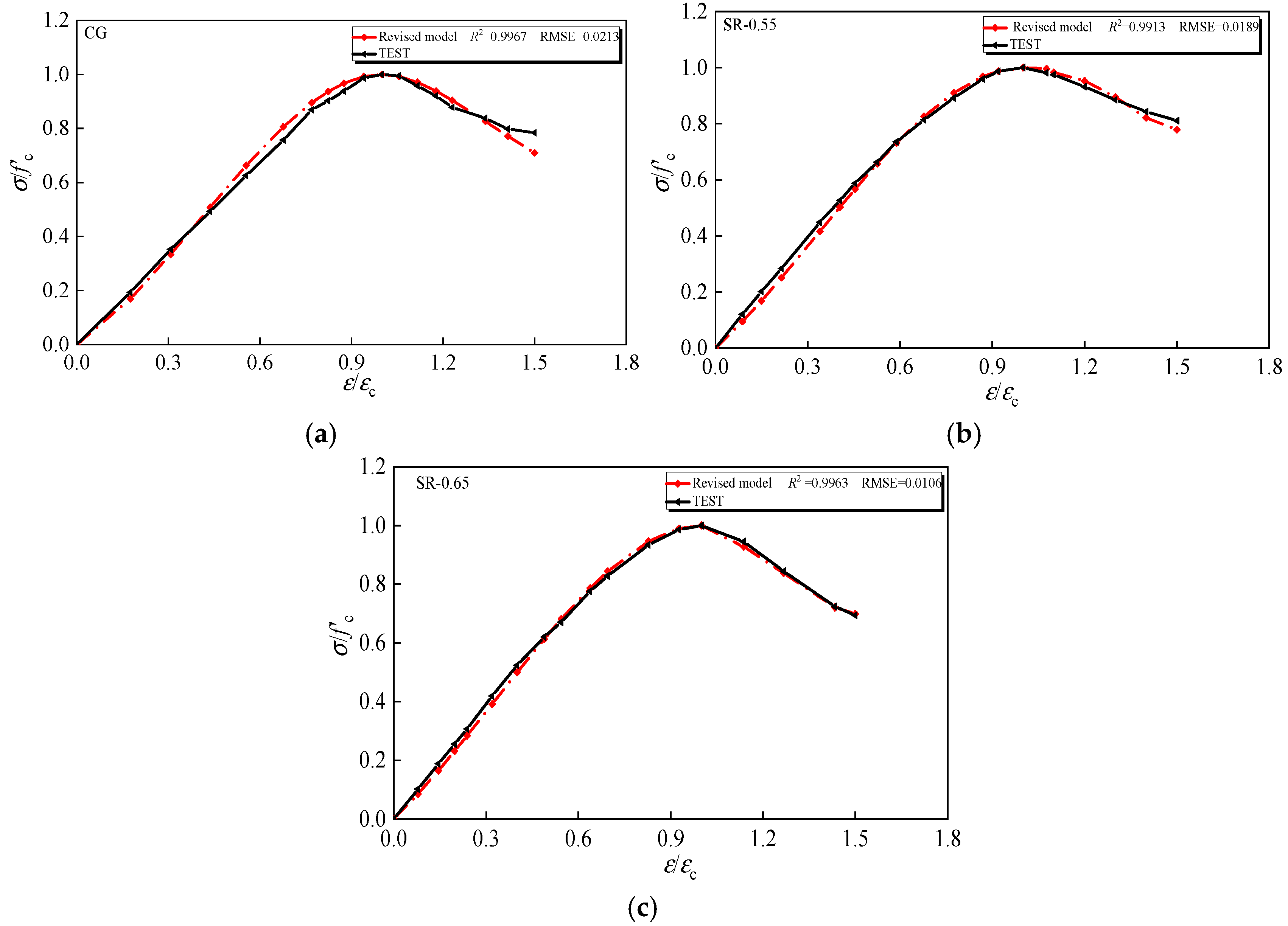

4.2. Model Revision

4.3. The Constitutive Curve Considering Freeze–Thaw Cycles

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Jabari, M. Concrete durability problems: Physicochemical and transport mechanisms. Integral Waterproofing Concr. Struct. 2022, 69–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambidi, B.; Markou, P.; Drakakaki, A.; Oungrinis, K.A. Challenges on contemporary architectural technology on durability of reinforced concrete structures. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 2021, 12, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, J.; Geng, Y.; Hu, J.; Sui, S.; Liu, A.; Hu, M.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Z. Application of silane protective materials in the concrete durability improvement in recent years: A review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 160, 108140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.X.; Qiu, W.L.; Jiang, M. Frost resistance performance assessment of concrete structures under multi-factor coupling in cold offshore environment. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zheng, S.; Feng, Z.; Chen, B.; Qin, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y. Prediction of the frost resistance of high-performance concrete based on RF-REF: A hybrid prediction approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 333, 127132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, K.; Luo, J.; Yin, W.; Chen, P.; Dong, J.; Liang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, Z. Research on the frost resistance performance of fully recycled pervious concrete reinforced with fly ash and basalt fiber. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Saha, P.; Jena, S.P.; Panda, P. Geopolymer concrete: Sustainable green concrete for reduced greenhouse gas emission–A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijiwala, D.B.; Patil, H.S. Geopolymer concrete A green concrete. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Chemical, Biological and Environmental Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, 2–4 November 2010; pp. 202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, N.; Mohamed, O.A.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Olabi, A.G. Geopolymer concrete as green building materials: Recent applications, sustainable development and circular economy potentials. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 836, 155577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Duan, Z.; Wang, J.; Yin, G.; Li, X. Frost resistance and improvement techniques of recycled concrete: A comprehensive review. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1493191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cui, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, M. Durability of concrete containing carbonated recycled aggregates: A comprehensive review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 156, 105865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Bu, Y.; Xu, T.; Zhao, X.; Yu, X.; Liang, Y. Research on freeze resistance and life prediction of Desert sand–Crushed stone fine aggregate concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, N.; Jiang, Z. Utilization of waste phosphogypsum in high-strength geopolymer concrete: Performance optimization and mechanistic exploration. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, W.W.A.; Apandi, N.M.; Adesina, A.; Alengaram, U.J.; Faris, M.A.; Tahir, M.F.M. Physico-mechanical properties of geopolymer mortars for repair applications: Impact of binder to sand ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 412, 134721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Ji, F.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Performance study and life prediction of desert sand concrete under chloride salt erosion and freeze-thaw cycle. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Su, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, P. Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2024, 63, 20230170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.W.; Oh, T.; Lee, S.K.; Banthia, N.; Yoo, D.-Y. Development of Ca-rich slag-based ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced geopolymer concrete (UHP-FRGC): Effect of sand-to-binder ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 370, 130630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Le, T.A.; Lee, K. Evaluation of the mechanical properties of sea sand-based geopolymer concrete and the corrosion of embedded steel bar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 169, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, L. A review on the damage behavior and constitutive model of fiber reinforced concrete at ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 412, 134919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, B.; Fang, Q. Analysis and evaluation of suitability of high-pressure dynamic constitutive model for concrete under blast and impact loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2025, 195, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z. Study on the mesoscopic mechanical behavior and damage constitutive model of micro-steel fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 443, 137767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Zhang, W.; Ye, X.; Liu, X. Mechanical properties and constitutive model of geopolymer lightweight aggregate concrete. Buildings 2024, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X. Impact toughness and dynamic constitutive model of geopolymer concrete after water saturation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimei, L.; Xueliang, G.; Cairong, L.; Zhengnan, Z.; Yuwei, D.; Haiyan, X. Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2024, 31, 20240020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Qi, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, L. Mechanical properties and compressive constitutive model of steel fiber-reinforced geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Qiu, J.; Yang, E.H.; Sanjayan, J. Micromechanics constitutive modelling and optimization of strain hardening geopolymer composite. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 5999–6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Ran, B.; Wu, T.; Zhou, X.; Xiong, Y. Physical performance, durability, and carbon emissions of recycled cement concrete and fully recycled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 138128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50082-2009; Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Ordinary Concrete. Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Yang, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Tang, Z.; Quan, W.; Xiong, X. Damage prediction and long-term cost performance analysis of glass fiber recycled concrete under freeze-thaw cycles. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L. Analysis of damage models and mechanisms of mechanical sand concrete under composite salt freeze–thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 429, 136311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. Principles of Reinforced Concrete; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, D.; Chu, K. Stress-strain relationship for plain concrete in compression. J. Am. Concr. Inst. 1985, 82, 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tam, V.; Li, W. Uniaxial compressive behaviors of fly ash/slag-based geopolymer concrete with recycled aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Lian, H. High-Performance Concrete; Railway Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, P. A constitutive model for fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2008, 1, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, K.; Ahn, N.; Le, T. Theoretical and experimental study on mechanical properties and flexural strength of fly ash-geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Particle Size /mm | Bulk Density /kg·m3 | Cylinder Pressure Strength /MPa | Apparent Density /kg·m3 | 1 h Water Absorption /% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBGLAs | 5–15 | 1025 | 12.48 | 1837 | 9.6 |

| Recycled sand | 0.15–4.75 | 1130 | - | 2650 | 11.2 |

| Materials | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | K2O | MgO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-class fly ash | 54.06 | 28.26 | 4.52 | 6.27 | 1.84 | 1.29 |

| S95-grade slag | 32.08 | 15.13 | 0.47 | 38.61 | 0.43 | 8.45 |

| SF88-grade silica fume | 90.93 | 0.80 | 3.01 | 0.58 | 1.05 | 1.08 |

| Sample | Slag | Fly Ash | Silica Fume | Recycled Sand | Lightweight Aggregate | Activator Solution | Water | Water Reducer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR-0.45 | 197 | 219 | 22 | 626 | 765 | 164 | 55 | 11 |

| SR-0.55 | 226 | 252 | 25 | 719 | 588 | 189 | 63 | 13 |

| SR-0.65 | 252 | 281 | 28 | 801 | 432 | 210 | 70 | 15 |

| Sample | Mass Loss/% | Surface Damage Feature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 Cycles | 50 Cycles | 75 Cycles | 100 Cycles | ||

| SR-0.45 | 0.46 | 0.90 | 1.59 | 2.70 | Slight spalling, smooth surface |

| SR-0.55 | 1.28 | 2.03 | 2.53 | 2.98 | Local flaking, visible micro-cracks |

| SR-0.65 | 2.77 | 3.6 | 3.97 | 4.61 | Severe spalling, exposed aggregate |

| Sample | 25 Cycles | 50 Cycles | 75 Cycles | 100 Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR-0.45 | 92 | 87.2 | 74.2 | 59.5 |

| SR-0.55 | 89.6 | 84.1 | 67.1 | 55.2 |

| SR-0.65 | 83.1 | 68.9 | 42.9 | 34.4 |

| Sample | 0 Cycles | 25 Cycles | 50 Cycles | 75 Cycles | 100 Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR-0.45 | 46.08 | 44.21 | 42.35 | 36.87 | 27.53 |

| SR-0.55 | 43.48 | 40.37 | 38.69 | 34.37 | 26.69 |

| SR-0.65 | 41.92 | 37.14 | 33.96 | 29.85 | 25.84 |

| Sample | Splitting Tensile Strength | Flexural Strength | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Cycles | 25 Cycles | 50 Cycles | 75 Cycles | 100 Cycles | 0 Cycles | 25 Cycles | 50 Cycles | 75 Cycles | 100 Cycles | |

| SR-0.45 | 3.12 | 2.86 | 2.66 | 2.24 | 1.86 | 6.24 | 5.20 | 4.54 | 3.99 | 3.35 |

| SR-0.55 | 2.98 | 2.83 | 2.49 | 2.14 | 1.84 | 6.09 | 5.16 | 4.34 | 3.61 | 3.01 |

| SR-0.65 | 2.64 | 2.53 | 1.96 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 5.94 | 5.12 | 4.27 | 3.42 | 2.42 |

| Sample | fc/MPa | εc/(×10−3) | ε0.85/(×10−3) | Ec/GPa | Ep/GPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR-0.45 | 38.34 | 2.33 | 3.06 | 18.87 | 16.45 |

| SR-0.55 | 35.41 | 2.72 | 3.77 | 17.92 | 13.02 |

| SR-0.65 | 34.90 | 2.76 | 3.49 | 15.96 | 12.65 |

| Sample | fc/MPa | εc/(×10−3) | ε0.85/(×10−3) | Ec/GPa | Ep/GPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR-0.45 | 36.03 | 2.47 | 3.32 | 16.42 | 14.61 |

| SR-0.55 | 32.46 | 3.03 | 4.11 | 11.07 | 10.73 |

| SR-0.65 | 29.60 | 2.78 | 3.69 | 12.41 | 10.64 |

| Sample | fc/MPa | εc/(×10−3) | ε0.85/(×10−3) | Ec/GPa | Ep/GPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR-0.45 | 33.37 | 2.72 | 3.43 | 14.49 | 12.28 |

| SR-0.55 | 28.56 | 3.34 | 4.22 | 8.94 | 8.55 |

| SR-0.65 | 25.57 | 3.10 | 5.01 | 8.76 | 8.25 |

| Sample | fc/MPa | εc/(×10−3) | ε0.85/(×10−3) | Ec/GPa | Ep/GPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR-0.45 | 26.99 | 2.79 | 3.73 | 11.58 | 9.66 |

| SR-0.55 | 23.17 | 3.65 | 4.93 | 6.46 | 6.34 |

| SR-0.65 | 21.28 | 4.43 | 5.98 | 5.48 | 4.80 |

| Model | Formula | Feature Points | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guo [32] | Ascending phase: Descending phase: | —— | a = Ec/Ep; Parameter b is determined based on the concrete grade and the constraint method. |

| Carreira [33] | |||

| Tang [34] | , Ascending phase: Descending phase: | ||

| Sarker [35] | , Ascending phase: Descending phase: | ||

| Nguyen [36] | , Ascending phase: Descending phase: | ||

| Noushini [37] | , Ascending phase: Descending phase: |

| Number of Cycles | α1 | α2 | β1 | β2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −2.857 | 4.933 | −0.323 | 6.336 |

| 25 | −3.921 | 4.031 | −0.210 | 4.066 |

| 50 | −3.725 | 3.948 | −0.029 | 1.224 |

| 75 | −2.478 | 2.785 | 0.147 | −0.440 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qiu, T.; Wen, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J.; Gao, X.; Liu, X. The Influence of Sand Ratio on the Freeze–Thaw Performance of Full Solid Waste Geopolymer Concrete. Buildings 2026, 16, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010076

Qiu T, Wen Y, Yang X, Zhou J, Gao X, Liu X. The Influence of Sand Ratio on the Freeze–Thaw Performance of Full Solid Waste Geopolymer Concrete. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Tong, Yuan Wen, Xinzhuo Yang, Jian Zhou, Xuan Gao, and Xi Liu. 2026. "The Influence of Sand Ratio on the Freeze–Thaw Performance of Full Solid Waste Geopolymer Concrete" Buildings 16, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010076

APA StyleQiu, T., Wen, Y., Yang, X., Zhou, J., Gao, X., & Liu, X. (2026). The Influence of Sand Ratio on the Freeze–Thaw Performance of Full Solid Waste Geopolymer Concrete. Buildings, 16(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010076