1. Introduction

In recent years, the development of underground space in prosperous urban areas has presented a deeper, larger, and denser development trend, which is manifested by the increasing density of urban rail transit networks, the emergence of deep and large foundation pits and underground complexes, and the gradual rise of urban underground roads and utility tunnels [

1]. As a result, the number of underground adjacent projects has increased significantly, and the safety protection problems of existing structures have become more acute and complicated. In regions with abundant groundwater and ample recharge, as well as complex geological and hydrological conditions, such as the Pearl River Delta area in China, the soil layers and their genetic types are diverse. The geological characteristics can generally be summarized as “water-rich, with uneven soft and hard layers”. Subway structures in the region are mostly located in “soft” strata, among which the interval tunnel is sensitive to the loading and unloading response of surrounding soil due to its small overall stiffness, and it is easy to produce uneven deformation, which will lead to local cracking of lining and other defects in severe cases, threatening the safety of subway operation, which is the focus and difficulty of subway security work [

2]. Based on the scientific problems revealed by typical engineering cases in the Shenzhen area—specifically that the excavation of upper foundation pits is prone to induce uneven deformation of the underlying shallow-buried existing tunnels, improper control measures may trigger a series of defects such as local cracking or damage of tunnel linings, thereby endangering the operational safety of tunnels. According to engineering experience, portal frame structures can form a “protective hoop” for existing tunnel structures, which can effectively reduce the longitudinal and transverse deformations of such tunnels. However, the load action mode of portal frame anti-heave structures is not entirely consistent with that of conventional building anti-floating systems. Relevant studies on their action mechanism and mechanical characteristics remain relatively scarce, necessitating that systematic research be carried out focusing on the mechanical behaviors of portal frame anti-heave structures.

Existing tunnel deformation control measures commonly used in adjacent foundation pit engineering include block and layer excavation, stratum reinforcement, stacking, tunnel lining reinforcement, and external anti-uplift structure [

3], etc. The most commonly used methods at present include setting uplift-resistant anchor rods or uplift-resistant piles [

4]. The action mechanism and applicable conditions of these measures are different, and the implementation results are also different. In recent years, engineering practice has demonstrated that anti-uplift systems incorporating uplift piles can effectively control the upward deformation of underground structures and overlying buildings. Extensive research has been conducted on uplift piles and anti-uplift slabs used in conventional building anti-flotation systems, yielding substantial findings concerning their mechanical behavior, design parameters, and performance characteristics. However, the loading mechanism of portal frame structures differs in several respects from that of traditional anti-flotation systems, and studies focusing on their mechanical behavior and underlying mechanisms remain limited. Several researchers have recently investigated the load-transfer mechanisms and deformation-control performance of portal-frame systems:

Ramadan et al. [

5,

6] conducted a comparative analysis of the mechanical behavior of pile shafts under loads at different inclination angles, concluding that there is a coupling effect between uplift loads and horizontal loads. Reddy et al. [

7] investigated the influence of pile-top pressure on the ultimate bearing capacity when a single pile is subjected to inclined uplift loads, proposing a semi-empirical formula for the relationship between pile-top pressure and ultimate bearing capacity. Schmertmann [

8] derived a theoretical formula for calculating the uplift-bearing capacity of rigid piles under combined loads. Zhang et al. [

9] conducted a numerical analysis on the influence of branch pile location, spacing, quantity, and diameter on the bearing capacity of piles, demonstrating that branch pipes can effectively share the load at the pile top. Filho et al. [

10] analyzed the uplift performance of grouted helical piles. Uplift piles primarily resist uplift forces through shaft resistance. In engineering practice, their uplift resistance performance can generally be improved by increasing the pile length, diameter, or surface roughness [

11,

12]. However, this concurrently leads to a further increase in project costs. In recent years, various special-shaped piles (such as belled piles, disc piles, helical piles, and battered piles) have been applied in engineering practice to enhance uplift performance [

13,

14]. Qian et al. [

15] systematically investigated the uplift bearing capacity of expanded-plate pile groups through full-scale tests and three-dimensional numerical simulations. Their results demonstrated that the overhanging disc significantly modifies the load transfer mechanism, forming a combined resistance mode of shaft friction and end-bearing at the disc, and an optimal disc diameter exists for maximizing uplift capacity. Mao et al. [

16] further proposed a two-stage analysis framework to distinguish the elastic rebound stage and the plastic deformation stage of existing tunnels subjected to adjacent excavation. Their results demonstrated that neglecting the staged unloading path may lead to significant underestimation of tunnel deformation.

Accurate numerical prediction of tunnel deformation induced by excavation and anti-uplift measures strongly depends on the ability of the constitutive model to capture the small-strain stiffness and unloading–reloading behavior of soils. Traditional Mohr–Coulomb and basic hardening soil models often fail to reproduce realistic rebound and stiffness degradation in soft soils. To address this limitation, Liang et al. [

17] developed a bounding surface constitutive model that incorporates the characteristics of small-strain stiffness and cyclic loading behavior of soft soils. Their model exhibited high accuracy in simulating soil rebound and nonlinear stress–strain behavior during excavation unloading. Meanwhile, Xiao et al. [

18] proposed an optimization-based parameter identification method for the Hardening Soil model with small-strain stiffness (HSS model), enabling reliable determination of soil parameters through inverse analysis combined with finite element simulations. These advanced constitutive formulations provide essential theoretical support for refined numerical analysis of excavation-induced tunnel deformation and the performance evaluation of anti-uplift structures, especially under small-strain conditions. Lan [

19] verified the effectiveness of the portal anti-uplift frame in controlling the uplift deformation of the underlying tunnel through numerical simulation. Qian et al. [

20] investigated the influence of bearing plate position on the uplift behavior of novel concrete expanded-plate pile groups through physical model tests and finite element simulations, demonstrating that staggered plate arrangements significantly modify load sharing and failure mechanisms within the pile group, and that an optimized plate position can effectively enhance the overall uplift bearing capacity. Through laboratory model tests and numerical simulation analysis, Chen et al. [

21] revealed that helical piles exhibit superiority over conventional uplift piles in terms of uplift bearing capacity, pile–soil interaction, and load transfer efficiency.

At present, the research on uplift piles and anti-floating plates in the anti-floating system of conventional buildings (structures) has been deepened, and rich achievements have been accumulated in mechanical characteristics and design parameters. However, the load action mode of the portal frame anti-uplift structure is not completely consistent with that of conventional building anti-floating systems, and research on its action mechanism and mechanical characteristics is rare. Based on typical engineering cases in Shenzhen, this paper will systematically study the mechanical characteristics of anti-uplift portal frame structures, through in situ stress tests and refined numerical analysis, to clarify the mechanical mechanism of anti-uplift portal frame structures and optimize the key technical parameters of anti-floating structure design and construction.

2. Project Overview

2.1. Stratum Parameters

In this paper, based on the foundation pit project of the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Cooperation Zone (hereinafter referred to as the water corridor project), the stress of the portal frame anti-uplift structure is studied. The water corridor project runs northeast–southwest, and it is 85 degrees oblique to Metro Line 9. The terrain within the red line is flat, there are no tall buildings (structures), and the adjacent water corridors at both ends have not been built yet. See

Figure 1 for the plane position relationship between the water gallery and the existing tunnel.

The strata in the site are mainly filled with earth, rock, muddy clay, cohesive soil, sandy cohesive soil (granite residual soil), fully weathered mixed granite, and strongly weathered mixed granite from top to bottom. See

Table 1 below for the physical and mechanical parameters of each soil layer. The buried depth of groundwater is 0.5~3.4 m. The top line of excavation is 46.0 m × 31.2 m, the depth is 5.0~5.5 m, the clear distance between tunnels and pits is 3.0 m, the unloading ratio is about 0.65, and the slope is 1:0.5.

The outer diameter of the existing shield tunnel lining is 6.0 m, the segment width is 1.5 m, the segment thickness is 0.3 m, the concrete strength is C50, and the clear distance between left and right lines is 7.8 m; the clear width of the main trough of the water corridor is 20.0 m, and the clear height is 4.0 m; the bottom plate is 39.0 m long, 24.2 m wide and 1.0 m thick. Three rows of uplift piles with a diameter of 1.2 m and a length of 22.0 m are set along both sides of the existing tunnel, including seven side piles with a center distance of 3.0 m, 10 middle piles with a center distance of 2.0 m, and a side wall thickness of 0.8 m. See

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 for typical sections.

2.2. Subway Protection Scheme and Key Processes

The water corridor project has adopted a subway protection scheme featuring “layered and block excavation, portal-section grouting, and frame anti-heaving structure”. Main construction steps: construction dewatering → replacement and filling (rock filling layer) → jet grouting reinforcement → water level recovery → uplift piles → dewatering → block excavation → bottom plate construction → side wall construction → backfilling and stacking.

A method of “well-point dewatering and in-pit collection and drainage” has been adopted to ensure water-free construction for excavation and anti-floating slab working faces. High-pressure double-tube rotary jet bite reinforcement (ϕ800 @ 600) is adopted, and the reinforcement scope is shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The uplift pile adopts full sleeve follow-up rotary drilling to form holes. The principle of giving priority to the formation of portal frame and jumping pit excavation to set up the excavation process is followed. See

Figure 4 for the layout of piles and the way of dividing the bottom plate, and

Figure 5 for the typical construction steps:

2.3. Structural Stress In Situ Test

The anti-uplift structure of the portal frame is spliced into a whole block by block, with a complex load mode and many construction procedures. To obtain the real stress state of the frame structure, an in situ stress test was carried out, and the strain of anti-floating concrete was tested by using high-precision FRP intelligent composite reinforcement with grating.

(1) Monitoring equipment

Compared with the traditional vibrating wire strain gauge, FRP intelligent composite reinforcement has the advantages of high precision, easy layout, less wiring, and convenient data acquisition. The diameter of the FRP smart composite rib selected this time is 8 mm, and the data acquisition equipment is a GM8050 portable optical fiber demodulator. The test rib and its layout are shown in

Figure 6.

(2) Survey line layout

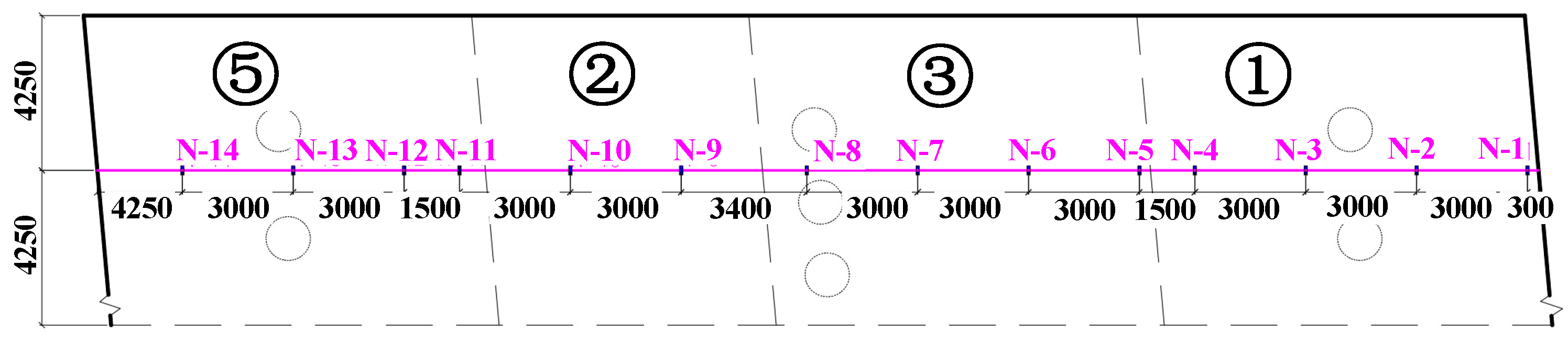

FRP intelligent composite bars are arranged in the floor structure corresponding to the blocks ①, ②, ③ and ⑤ that form the portal frame at first, and installed in the internal side of the upper and lower main bars. Test bars are cut to length according to the excavation width of each block and installed step by step with the excavation of the foundation pit. The layout of survey lines is shown in

Figure 7.

(3) Data processing

The strain value at the measuring point is calculated by Equation (1):

where:

K—grating strain coefficient, taking 833 ;

B—temperature correction coefficient. Considering that the thermal expansion coefficient of FRP composite bars is close to that of concrete materials, the temperature expansion stress is not considered separately, so take ;

—Test wavelength of strain grating, nm;

—Initial wavelength of strain grating, nm;

—Testing wavelength of temperature-compensated grating, nm;

—Initial wavelength of temperature-compensated grating, nm.

4. Deformation Response of Existing Tunnels

The primary design approach for the gantry frame anti-uplift structure focuses on promptly establishing a frame system comprising uplift piles and anti-buoyancy slabs, so as to restrain the deformation of underlying strata and control the uplift of existing tunnels during the excavation of adjacent foundation pits. This section focuses on the stress evolution process of the Z-1 section where the central connecting line of uplift piles 1#, 8# and 18# first forms the pile-plate frame structure, and the section position is shown in

Figure 12. The nephogram of vertical stress of the Z-1 section uplift pile and X-direction horizontal stress of the anti-floating plate under typical excavation steps is shown in

Figure 13, and the extreme development of structural stress is shown in

Figure 14.

With the step-by-step excavation of the foundation pit, the frame structure is gradually expanded and shaped, and the structure has undergone a complex evolution process, which can be divided into three stages as a whole. Before the portal frame structure was formed, the uplift piles and the anti-floating plates were separated from each other, and no integral stress structure was formed. When the uplift pile is excavated in blocks, the tensile stress of the pile is greatly increased due to the floating of the stratum around the pile, and it is reduced after the upper floor is poured and backfilled. At this stage, the anti-floating plate mainly bears local surcharge, and the horizontal stress is relatively small. After the portal frame structure is formed, the loads include the upper stacking load, the buoyancy on the stratum caused by the excavation of adjacent soil, the soil pressure on the slab side, the pile–soil friction, and the self-weight of the structure, and the stress is very complicated. The anti-floating plate bears the combined action of compression, bending, and shear and generally presents the stress state of upper compression and lower tension. The maximum tensile stress is 426.5 kPa, which appears at the bottom of the anti-floating plate between 8# and 18# piles that first form the frame structure. The uplift pile shows tension in the middle and compression at the upper and lower ends. After the cross-section frame is fully formed, the structural stiffness is greatly increased, and the stress changes gradually stabilize. When the pile is unloaded, the tensile stress of the uplift pile increases greatly, and the uplift effect is fully exerted, reaching an extreme value of 1.0 MPa, which is about 6.5 m below the top of the middle pile.

The safety state of the structure is controlled by tensile stress, in which the tensile and compressive stresses of the anti-floating plate are far less than the design values. If it is only used as an anti-uplift measure, there is a large room for optimization, so it is suggested to appropriately reduce the section size and the reinforcement ratio.

5. Mechanical Characteristics of Anti-Floating Plate

5.1. Typical Section Stress Distribution

The horizontal stress distribution of eight typical cross-section anti-floating plates parallel to the existing tunnel axis and the water gallery axis is analyzed. The cross-section position and number are shown in

Figure 15, and the stress distribution nephogram of each cross-section under the condition of stack unloading is shown in

Figure 16.

Anti-floating plates are spliced into a whole piece by piece. Under the combined action of buoyancy, backfill surcharge, and earth pressure on the side of the plates, the stress distribution in the section is significantly different; the upper part is in compression, and the lower part is in tension. In the X-direction section, the tensile stress of the BX-2 section at the axial position is significantly greater than in other sections. At the same time, the stress in the area where the pile-plate frame is formed first is relatively concentrated, and the extreme value is located near the top of the 21# side pile on the east side. The Y-direction tensile stress of the anti-floating plate is concentrated at the joint of blocks, and its extreme value is 0.335 MPa at the joint between block 3 and block 8 of the BY-3 section of the middle pile. The extreme values of tensile and compressive stresses in each section are far less than the design tensile strength of C35 concrete, which shows that the overall bearing capacity of the anti-floating slab structure is relatively large, and the optimization methods such as reducing the section size and adopting non-uniform reinforcement in combination with stress concentration can be applied appropriately.

5.2. Actual Measurement and Numerical Analysis of the Bending Moment of the Anti-Floating Plate

The measured and numerical results show that the maximum tensile stress of the anti-floating plate is less than the ultimate tensile strength of concrete during excavation, and the structure is in the elastic stress stage as a whole. Assuming that the strain of the vertical section where each measuring point is located is linearly distributed, the concrete and steel bars work together to coordinate deformation, and the bending moment of the section is calculated with reference to the research results of Liu Guobin and others [

28]. Based on considering the change in the neutral axis position, the composite material composed of steel bars and concrete is converted into a single material section. The area of steel bars in the tension zone (

As) and the area of steel bars in the compression zone (

As′) are converted into equivalent concrete areas

nAs (where

n =

Es/

Ec) at their respective designed positions, and the section bending moment value can be obtained according to Equation (2) of material mechanics.

where

M is the calculated bending moment at the measuring section;

Ec and

Es are the elastic modulus of concrete and steel bar, respectively;

εt,

εc is the measured value of a pair of measuring points;

d denotes the center-to-center distance between a pair of steel bar gauges to be tested;

Ic is the moment of inertia of the measuring section:

where

h0 is the effective height of the section of the anti-floating plate, that is, the distance from the outer edge of the compression zone to the center of gravity of the tensile reinforcement;

b takes the unit width of 1 m;

a is the thickness of the concrete protective layer;

xc is the height of the compression zone, which is calculated from the measured concrete strain. Assuming

εt represents the tensile strain of the concrete and letting

, the height of the compression zone can be calculated using Equation (4). If

xc >

h0, take

xc =

h0, then it can be solved through the formula

The measured and numerical data of the BX-1 section under three typical working conditions, such as “5-excavation to the bottom”, “9-backfilling”, and “removal of surcharge”, are selected for calculation, and the distribution of the bending moment is shown in

Figure 17.

The anti-floating slab is gradually spliced into a whole with the excavation process, during which it is mainly influenced by the upper stacking load, foundation reaction force, buoyancy on the stratum, earth pressure on the slab side, and structural weight, and the distribution of the bending moment is complicated. The BX-1 section is mainly influenced by the positive bending moment (lower tension), and there is a negative bending moment distribution near the side piles, which shows that under the engineering conditions, the anti-floating slab load is mainly backfill stacking load, and the buoyancy on the foundation is relatively small. The distribution of the section bending moment changes with the working conditions. The maximum bending moment under the working condition “5-excavation to the bottom” is 100.65 kN·m, which is located on the east side of the middle pile, and the bending moment under the working condition “9-backfilling” is greatly increased, and the extreme position shifts to the east side pile. After the removal of the stacking load, the peak bending moment decreases and moves to the middle pile, and the distribution of the bending moment on both sides tends to be balanced. Overall, the peak bending moment of the plate body is obvious, but the magnitude is small, and the bearing capacity is large. The application sequence of the anti-floating plate has a significant influence on the bending moment. The bending moment between the middle pile and the east side pile is greater than that in the later forming area, and there is a sudden change at the block boundary. Step-by-step excavation and timely backfilling have suppressed the space-time effect of excavation to a certain extent, and the structure tends to be safe. In the area between the side piles on both sides, the distribution of numerical results of measured data is relatively consistent, with little difference in magnitude, which shows that the model has high reliability and the parameter setting is basically reasonable. There are some differences in the distribution of the bending moment between the side piles on both sides and the edge of the slab. First, because the measured points are limited, spline curves are used to describe the bending moment, and the bending moment values at individual positions may be different from the actual situation. Second, there are some uncertain factors in practical engineering, such as inadequate backfill load, over-excavation, pavement trimming, and loose soil contact at the side of the slab, which makes the stress state of the structure different from the idealized numerical model.

6. Mechanical Characteristics of Uplift Piles

6.1. Stress Distribution

Uplift piles mainly bear vertical loads such as upper pile load, pile side friction, structural self-weight, buoyancy, and pile tip resistance, which is different from the uplift force transmitted from the upper structure by the general uplift pile load, and mainly comes from the friction force acting on the pile body and the uplift force acting on the anti-floating plate when the stratum floats. The load action process and distribution law are complicated, and its bearing safety state is mainly controlled by axial tensile stress. Based on the extreme stress evolution process of the Z-1 section of the frame structure shown in

Figure 14, the vertical stress distribution of the cross section of the center connection line of each row of piles is analyzed when the most unfavorable working condition is removed. The cross section position is shown in

Figure 18, and the vertical stress distribution of uplift piles is shown in

Figure 19.

It can be seen from the figure that the vertical stress distribution of uplift piles presents the following laws. The vertical stress of the uplift pile is unevenly distributed along the pile body, with the upper and lower ends compressed and the middle tensile. The compressive stress is small, and the safe state of bearing is controlled by the tensile stress. The tensile stress of the P-2 section of the middle pile is relatively large, followed by the P-3 section of the side pile excavated first. At the same time, the closer to the edge of the water corridor, the more obvious the eccentric compression phenomenon of the pile body. After the removal of the pile load, the extreme value of tensile stress of these 24 piles increases to 1.35 MPa, which is about 3 m below the top of pile 11#. At this time, the tensile stress has reached 78.9% of the designed tensile strength. Considering the distribution range of tensile stress of each pile, reinforcement can be strengthened within 10 m (twice the excavation depth) below the top of the pile.

6.2. Evolution of Axial Force

By studying the development of the axial force of uplift piles, the evolution process of stress can be revealed, and the key construction steps can be judged. The development of the axial force of the 18# and 8# piles, which first form the pile-plate frame structure, is selected for analysis. The analysis process is divided into two stages: one is the excavation of the No. 1 block to the formation of the pile-plate frame; second, after the pile-plate frame is formed, the pile load is removed. The changes in axial force of the 18# and 8# piles after the frame structure is formed are shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21. The axial force of the uplift pile is calculated according to Equation (5):

where:

—Mean value of strain at measuring points of cross section;

—Equivalent stiffness of section;

—Cross-sectional area of pile body.

As can be seen from

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, after the uplift pile is poured, the load is mainly the self-weight of the structure and the overburden load; the soil around the pile produces a certain negative friction due to the stacking load, and the axial force distribution increases first and then decreases from top to bottom; 5 m precipitation before excavation leads to a significant increase in negative friction on the pile side and an increase in axial force of 280~330 kN.

The excavation in blocks causes the underlying strata to float in a certain range, the relative displacement and friction direction of the pile–soil interface in the middle and upper part of the pile body change, and the axial force changes from compression to tension. After the anti-floating plate is poured and backfilled, the compressive stress at the pile-plate joint is concentrated, the tensile stress and tensile range of the pile body are significantly reduced, and the bearing state tends to be safe. After the stack load is removed, the uplift effect is fully exerted, and the extreme value appears at about 0.3 times the pile length. After the piles and slabs are spliced one by one to form a low cap foundation similar to pile groups, the stiffness is significantly improved, the influence of adjacent block excavation on its stress is greatly reduced, the pressure at the top of the pile is gradually reduced, and the tensile range and tensile stress of the pile are slightly increased. Relatively speaking, the 8# middle pile is affected by the excavation of soil on both sides, the stress fluctuation is relatively large, and the extreme value of axial force and tensile range are larger than those of the 18# pile, which is the focus of structural bearing capacity checking. During the whole process of foundation pit excavation, the uplift force of uplift piles mainly comes from the uplift of soil around the piles. The maximum axial force of the 18# pile is 808.4 kN, and that of the 8# pile is 920.6 kN, both of which are less than the design value of uplift bearing capacity of piles of 3228.13 kN.

7. Conclusions and Discussion

7.1. Discussion

Using a constitutive model that can capture the small-strain behavior of soils, coupled numerical analyses closely reproduce the mechanical response of the portal-frame anti-uplift system during staged excavation, as reflected by field monitoring data. The measured bending moments in the anti-uplift base slab and the axial forces in the uplift piles are within the ranges typically reported in engineering practice, and their temporal evolution and spatial distribution patterns align well with existing research findings. The numerical discrepancies between this study and some previously published work can largely be attributed to differences in pile geometry, the selection of soil constitutive models, the modeling of interfaces, the treatment of groundwater–soil coupling effects, and the computational domain size and boundary conditions adopted.

(1) Wu et al. [

29] reported that forming a closed force-transfer loop in a portal-frame system reduces tunnel uplift and observed a localized bending-moment concentration near the joints of the early-formed frame. The stress concentrations observed at the BX-2 and BY-3 sections in the present study, as well as the migration of the location of the maximum bending moment during construction, are consistent with the field observations of Wu et al. This indicates that regions where the frame forms early are prone to inducing bending-moment and stress concentrations.

(2) Although this study aimed to achieve an accurate numerical simulation, it was inevitable that there would be certain quantitative discrepancies with other published studies due to differences in modeling approaches and underlying assumptions. The plastic hardening (PH) model adopted in this study effectively captures the small-strain stiffness characteristics of soils, with a small-strain threshold of γ

0.7 of approximately 10

−4 (see

Table 1). However, it has been reported that more advanced constitutive models, such as the bounding surface model or the Hardening Soil with Small-Strain Stiffness (HSS) model, can better account for small-strain stiffness and loading–unloading behavior. Consequently, they can more accurately reproduce soil rebound and unloading responses [

30]. Compared with classical Mohr–Coulomb or conventional hardening soil models, these advanced constitutive models generally predict more pronounced small-strain hardening characteristics and different mobilization patterns of pile–soil shaft friction. This contributes to the disparities observed among different studies.

In this study, the shear strength of the pile–soil interface was set at 70% of the shear strength of the soil itself, and a bonded constraint was applied between the piles and the base slab. Other studies may use different descriptions of the interface, such as fully rough contact, Coulomb friction models with various friction angles, or explicitly modeled grouting interfaces. These differences can lead to variations in the predicted axial force distributions. The present simulation accounted for fluid–solid coupling by setting the initial groundwater level at −2.0 m. However, some laboratory tests and simplified numerical studies have neglected the effects of groundwater. This can result in buoyancy being underestimated during dewatering and recovery processes, as well as in the transient evolution of pore water pressure. Additionally, variations in construction sequences (e.g., grouting, curing time, slab casting sequence, and temporary support arrangement) can significantly impact the timing and location of pile–soil shaft friction reversal. Existing case studies have shown that the early formation of a continuous base slab or timely backfilling can markedly reduce peak tensile stresses, a trend also confirmed by this study’s results.

(3) When the soil strain level falls below the order of 10−4–10−3, geomaterials exhibit a pronounced small-strain stiffness enhancement. If the constitutive model adopted does not adequately capture this small-strain stiffness, the numerical simulation may over-predict instantaneous deformations and underestimate the magnitude of tensile forces mobilized in the piles. Conversely, an excessively stiff model may lead to underestimated settlements and may produce unrealistic concentrations of pile–soil shear stress near the pile head.

In this study, high-precision FRP smart composite bars with embedded optical gratings were used for field monitoring, enabling high-resolution measurement of micro-strain responses and providing a reliable basis for validating the numerical predictions. In addition, distributed fiber-optic sensing systems [

31,

32] served as an effective complement to conventional point-type strain gauges, allowing continuous measurement of the axial strain distribution along the pile.

Given the high sensitivity of uplift response to the representation of small-strain stiffness, it is recommended that, in addition to the FRP strain gauges already deployed, at least one representative uplift pile be instrumented with a distributed fiber-optic sensing line. This would facilitate more refined identification of potential zones of reversed shaft friction and further verify the predicted depth of peak tensile stress.

7.2. Conclusions

Based on the foundation pit project of the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Cooperation Zone in Qianhai, a stress test of the portal frame anti-uplift structure was carried out. Combined with a fine numerical modeling analysis, the mechanical response characteristics of the portal frame structure were systematically studied, the main stress characteristics and evolution process of uplift piles and anti-floating plates were revealed, and the unfavorable working conditions and weak positions of the structure were pointed out. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) By using a constitutive model that can characterize the small strain characteristics of soil, the main structures and key contact surfaces are finely modeled, the construction process is reasonably restored, and more reliable, comprehensive, and intuitive numerical results are obtained. Combined with an in situ stress test, the stress distribution and internal force development of the portal frame structure are deeply analyzed, and its main stress characteristics are revealed.

(2) During the construction of the upper foundation pit, the portal frame structure is gradually spliced into a whole, its load action mode is changeable, and the structural stress is more complicated. Before the frame is formed, the stress state of piles and slabs fluctuates greatly due to the influence of excavation and surcharge. After the frame is formed, the stiffness of the structure is greatly improved, and the influence of adjacent block excavation on the structure is greatly reduced. When combined with staged excavation, ground reinforcement, backfilling, and surcharge countermeasures, the portal frame structure demonstrates effective performance in shallow foundation pit projects. Among these measures, staged excavation has the most significant effect on controlling tunnel deformation, followed by ground reinforcement.

(3) Uplift piles mainly bear vertical load, with the middle part in tension and the two ends in compression. The load mode of an anti-floating plate is a combination of compression, bending, and shear, and the positive bending moment is mainly distributed in the area between two piles, while the negative bending moment exists at the top and outer cantilever section of the pile, so the overall force is small. The most unfavorable working condition is the stage of stack unloading, and the extreme tensile stress of the structure is 1.35 MPa, which is located about 3 m below the top of pile 11#, which needs special attention.

(4) Based on the engineering conditions, the bearing capacity of the anti-floating plate in the portal frame structure has a large margin, so it can be optimized by reducing the thickness of the plate, reducing the reinforcement ratio, and adopting asymmetric reinforcement in the tension and compression area. At the same time, the reinforcement can be appropriately strengthened within the scope of 2 times the excavation depth below the pile top. The portal frame structure can effectively reduce the deformation of existing tunnels induced by adjacent excavation. After the combination of uplift piles and anti-floating plates forms a framed system, tunnel stability is substantially enhanced. In shallow foundation pit projects, the use of this structure can also simplify the implementation of other auxiliary control measures.

(5) Clarifying the mechanical characteristics of the portal frame anti-uplift structure has a certain reference value for optimizing the design and construction parameters of the anti-floating structure system, but the influence of the stress and internal force (bending moment and axial force) changes in the anti-floating structure on controlling the uplift deformation of the existing tunnel needs further study.