Energy Performance Evaluation and Optimization of a Residential SOFC-CGS in a Typical Passive-Designed Village House in Xi’an, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- First application in rural Western China:

- 2.

- Design and assessment of an integrated PV–battery–SOFC system:

- 3.

- Demonstration of multi-energy complementarity and system-level synergy:

- 4.

- A scalable and replicable pathway for rural decarbonization:

2. Materials and Methods

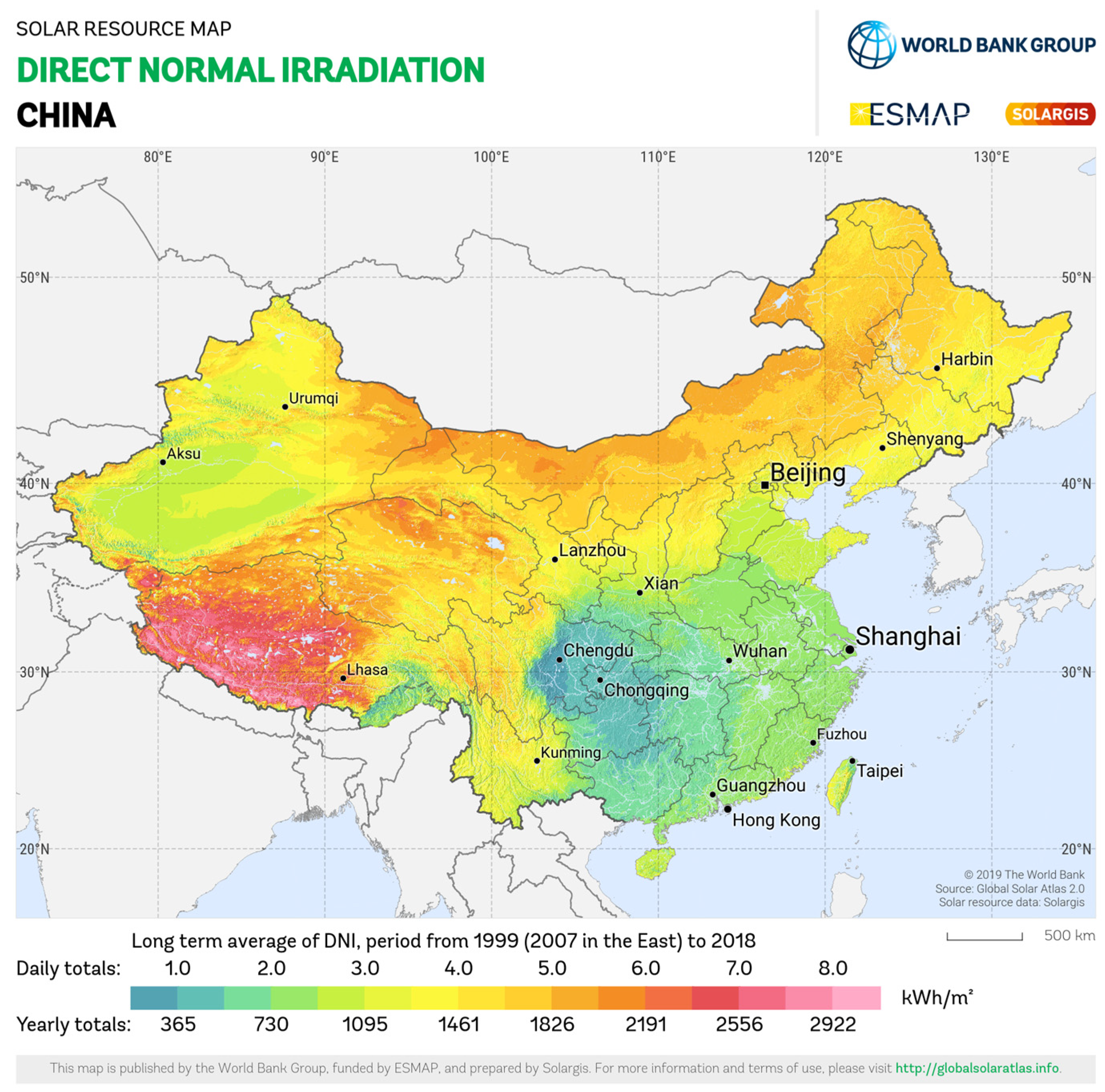

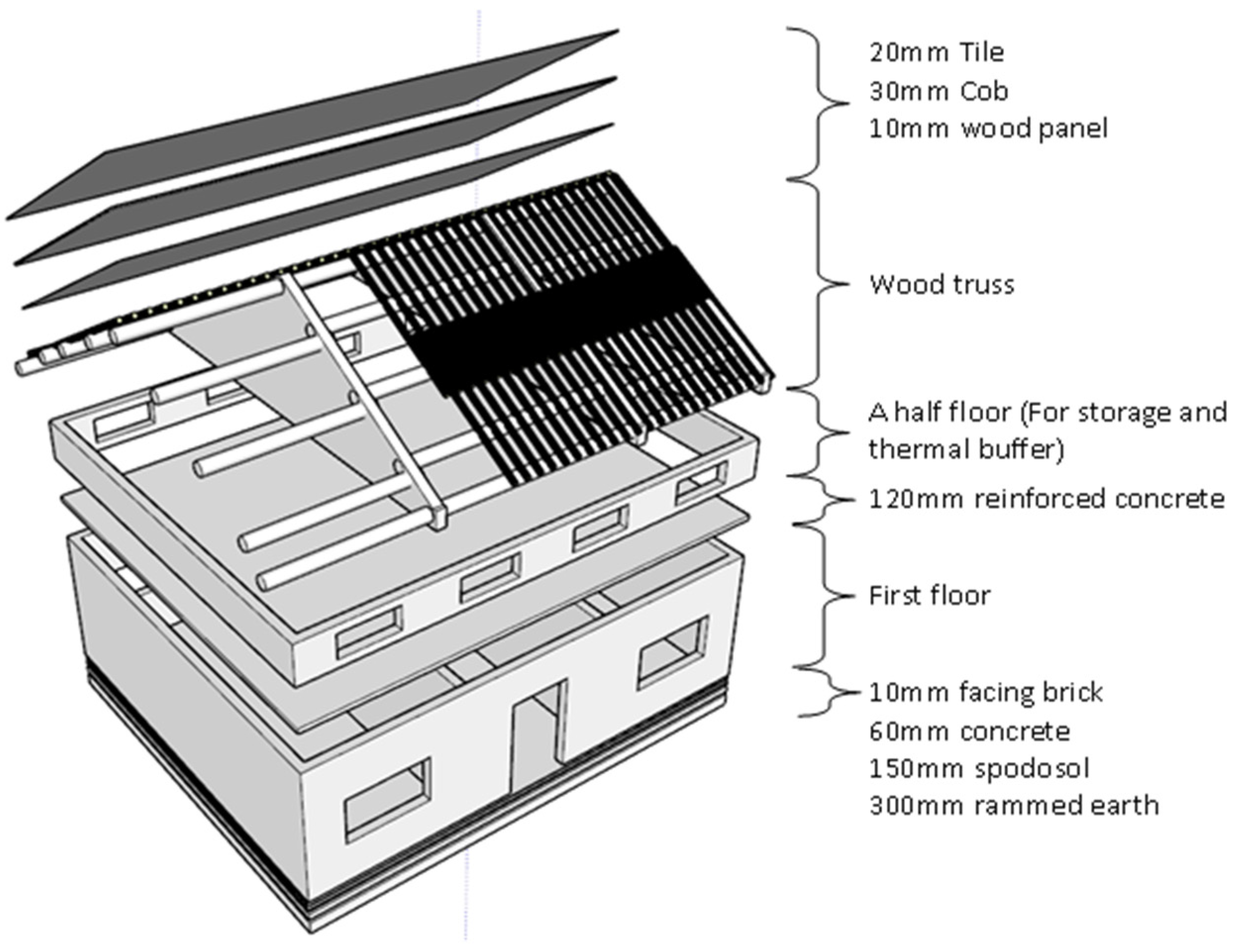

2.1. Research Object

2.2. Research Methodology

3. Analysis of Applying SOFC-CGS in the House

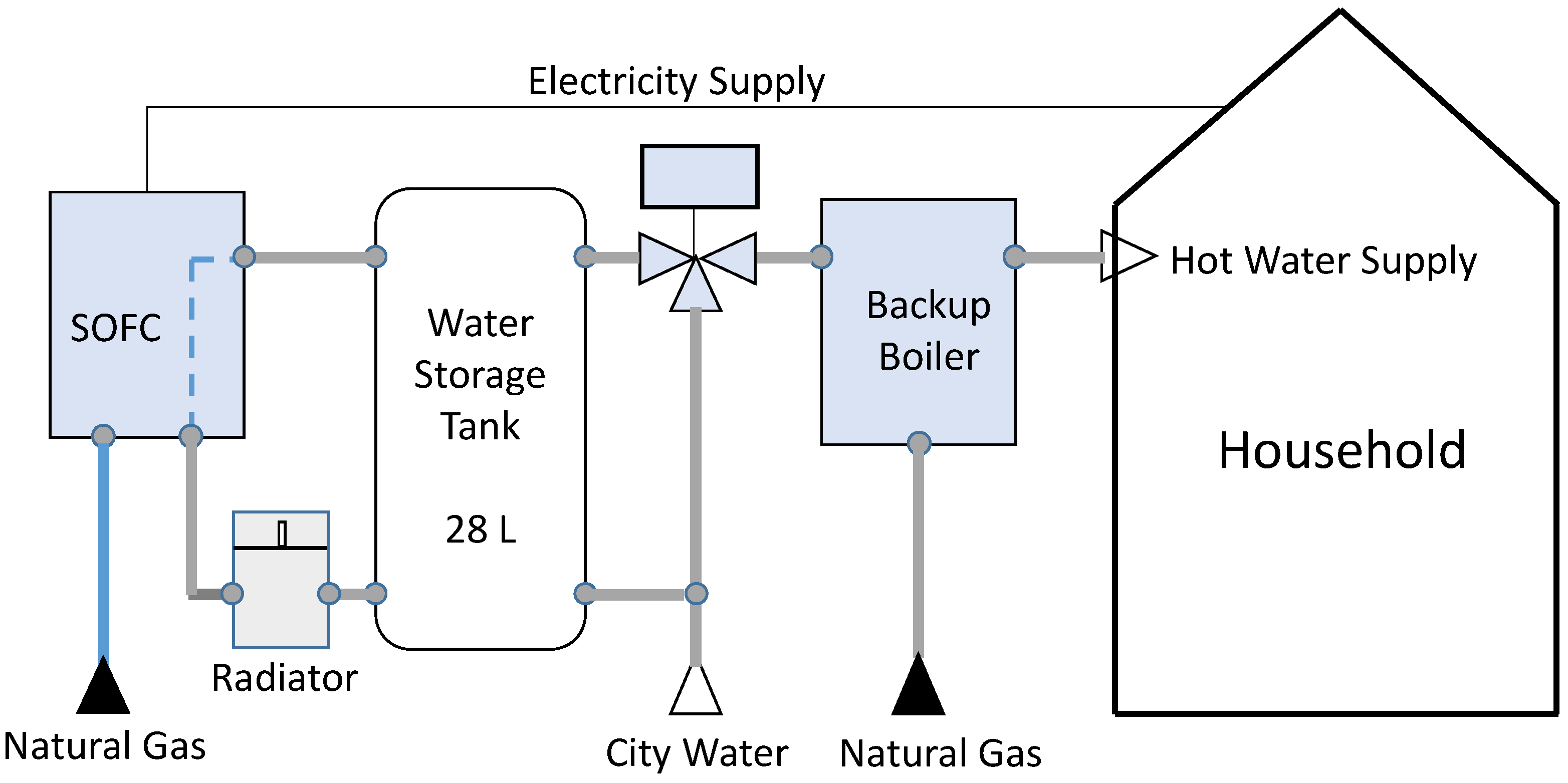

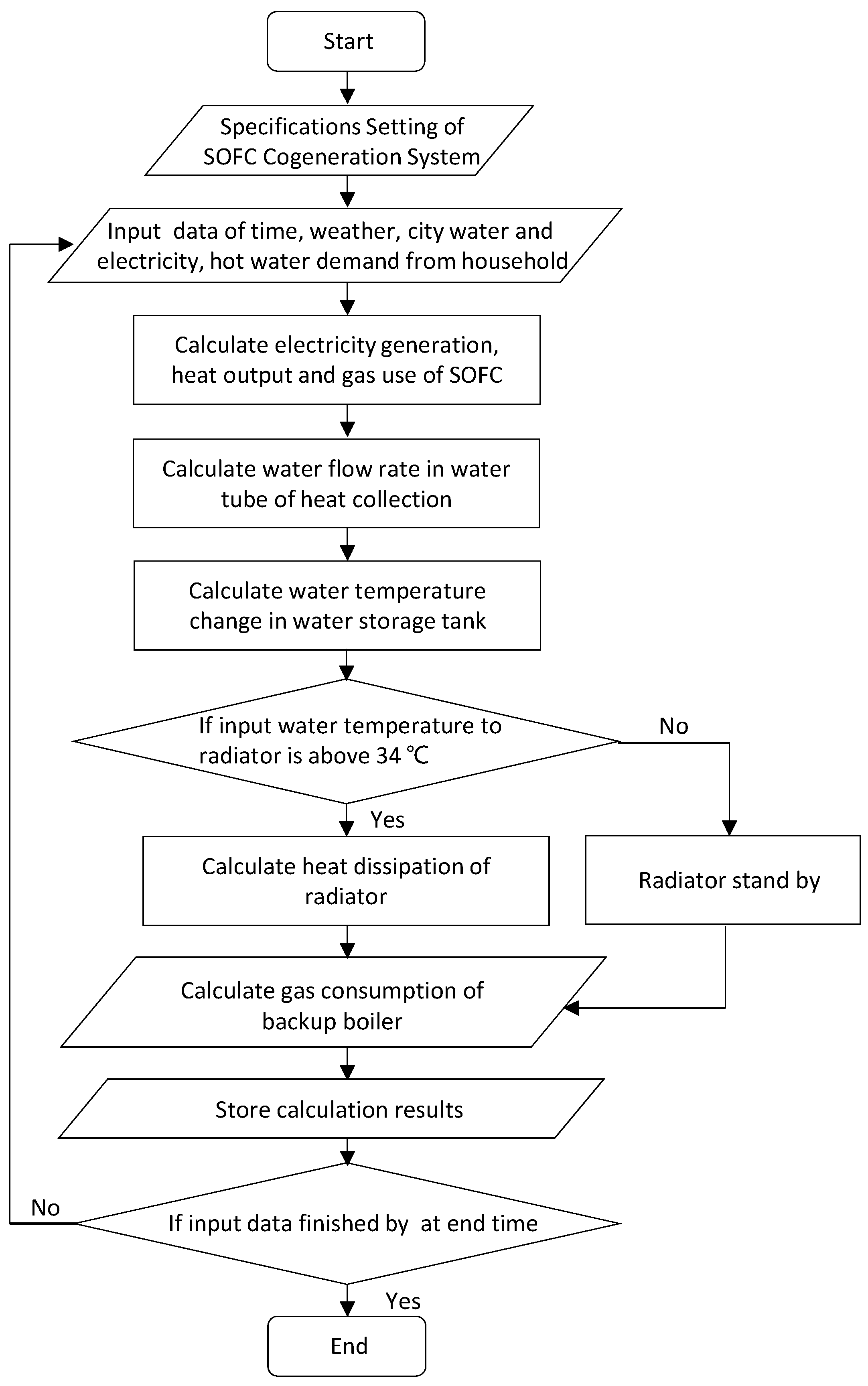

3.1. Modeling of SOFC-CGS

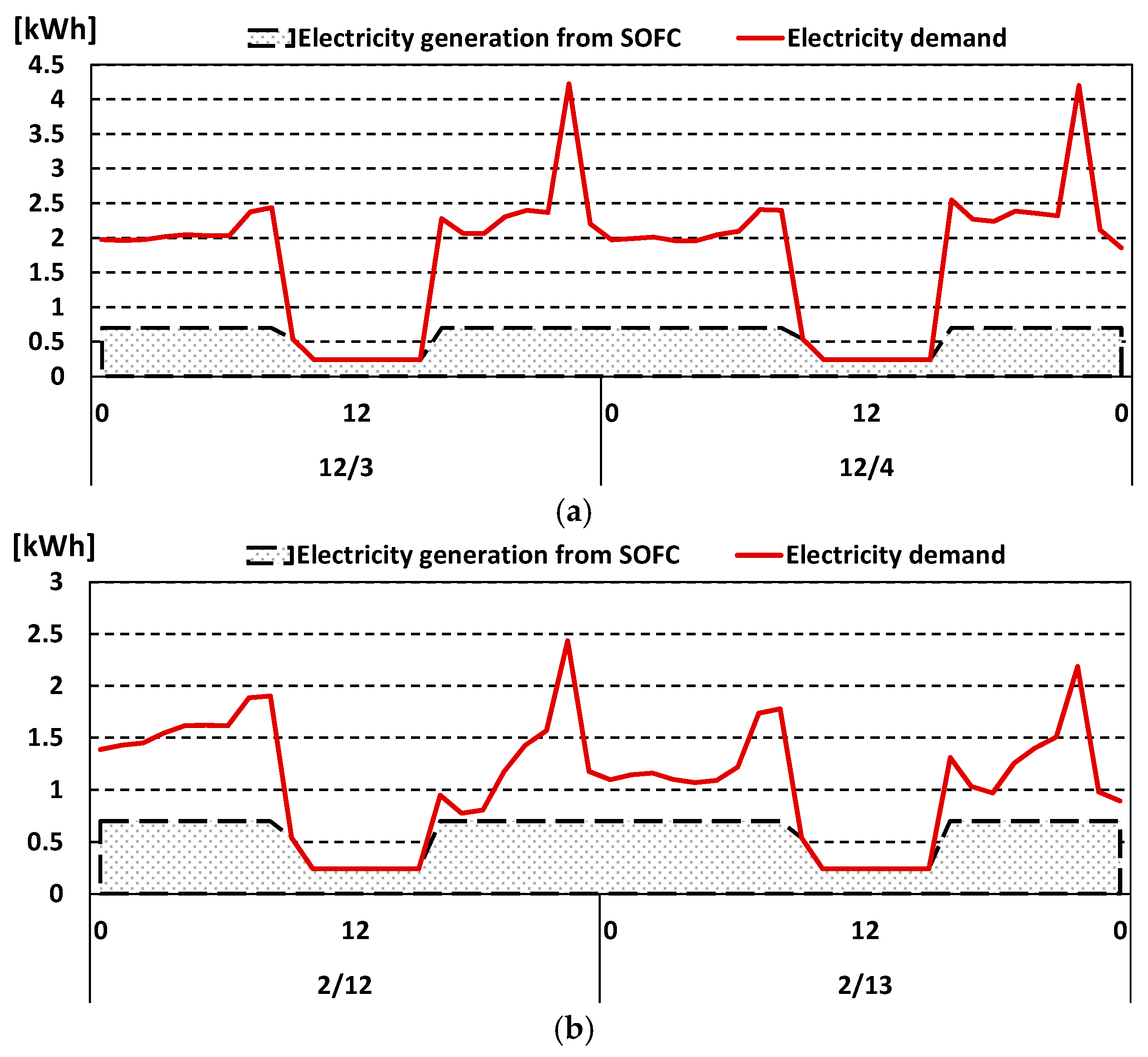

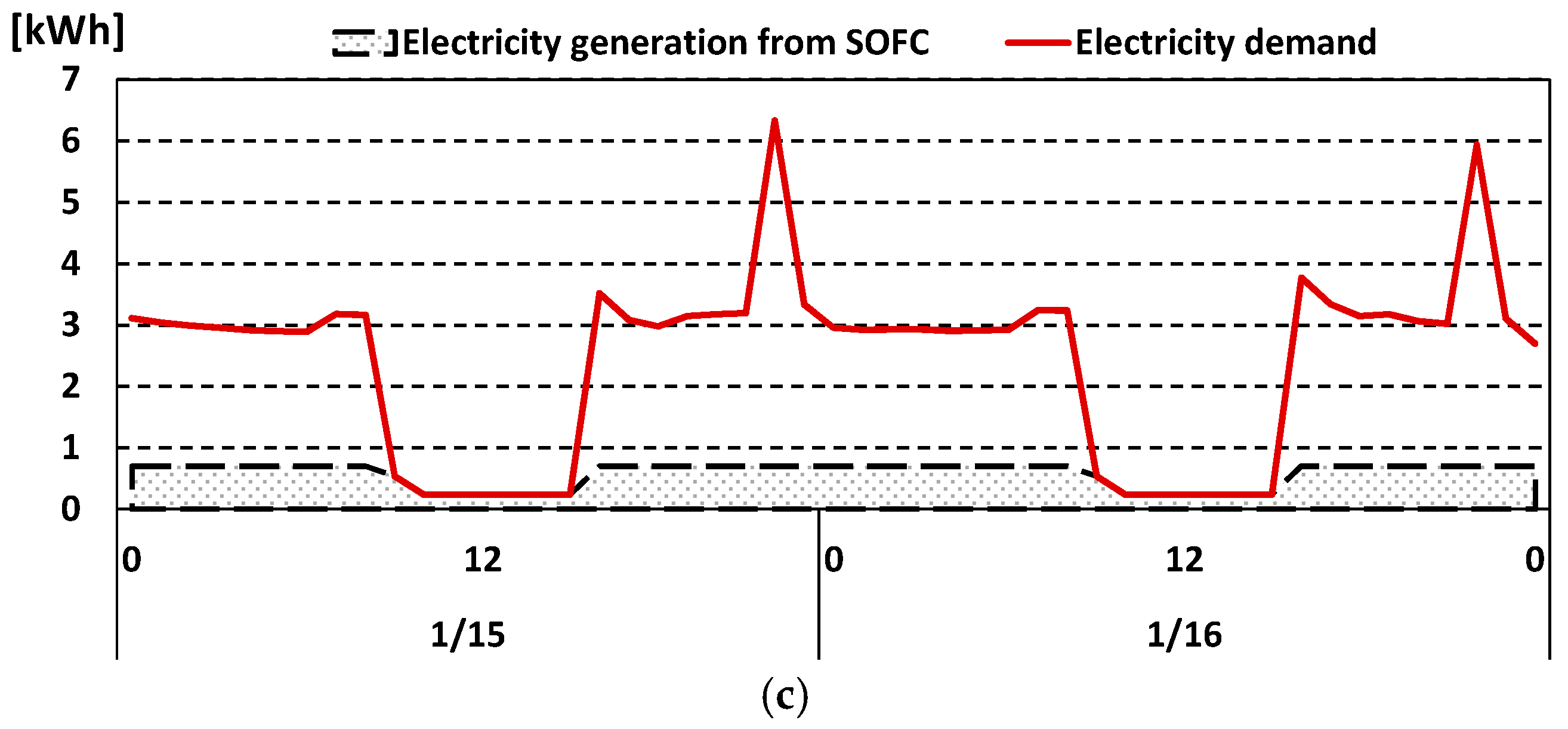

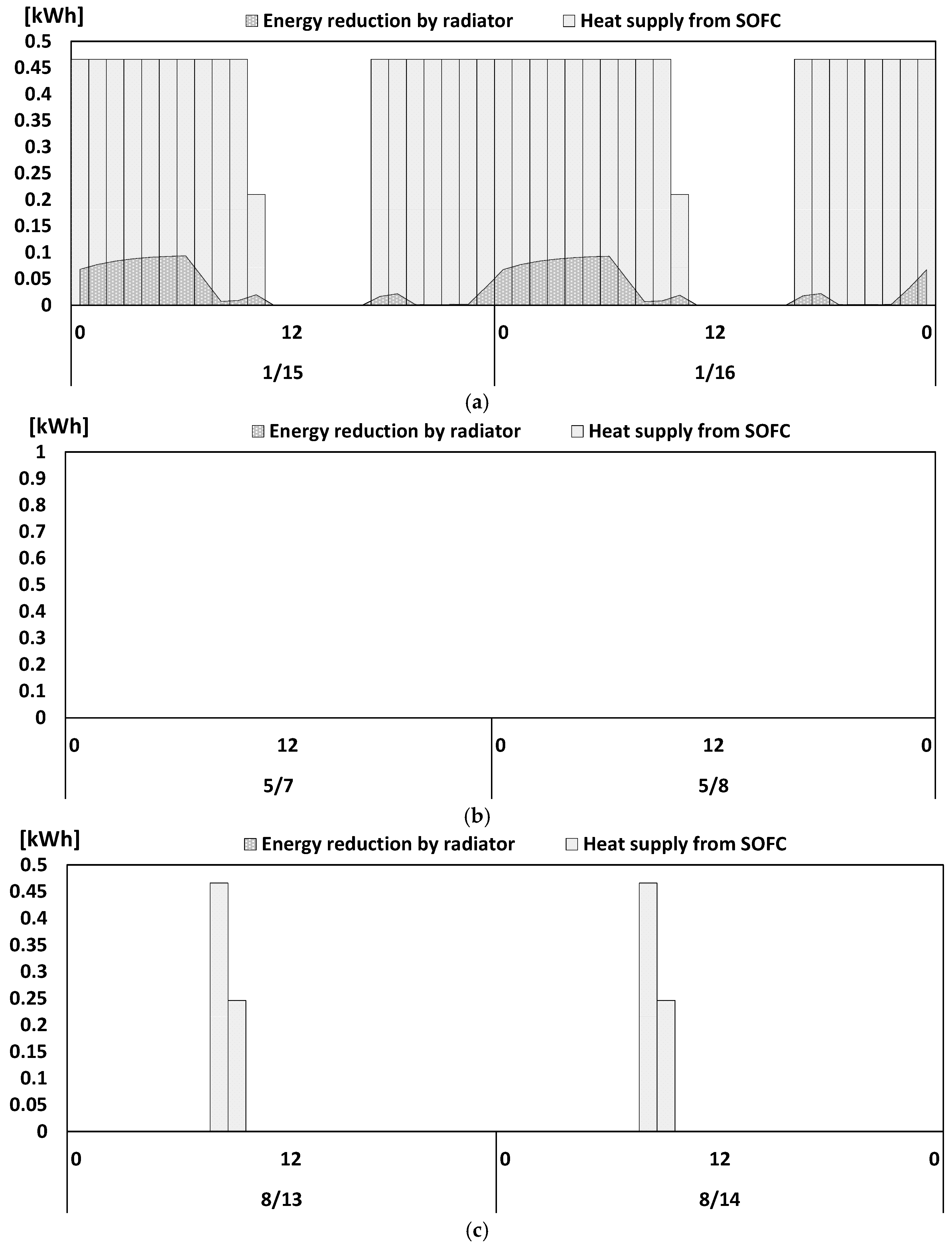

3.2. Simulation of SOFC-CGS in the Passive-Designed Village House

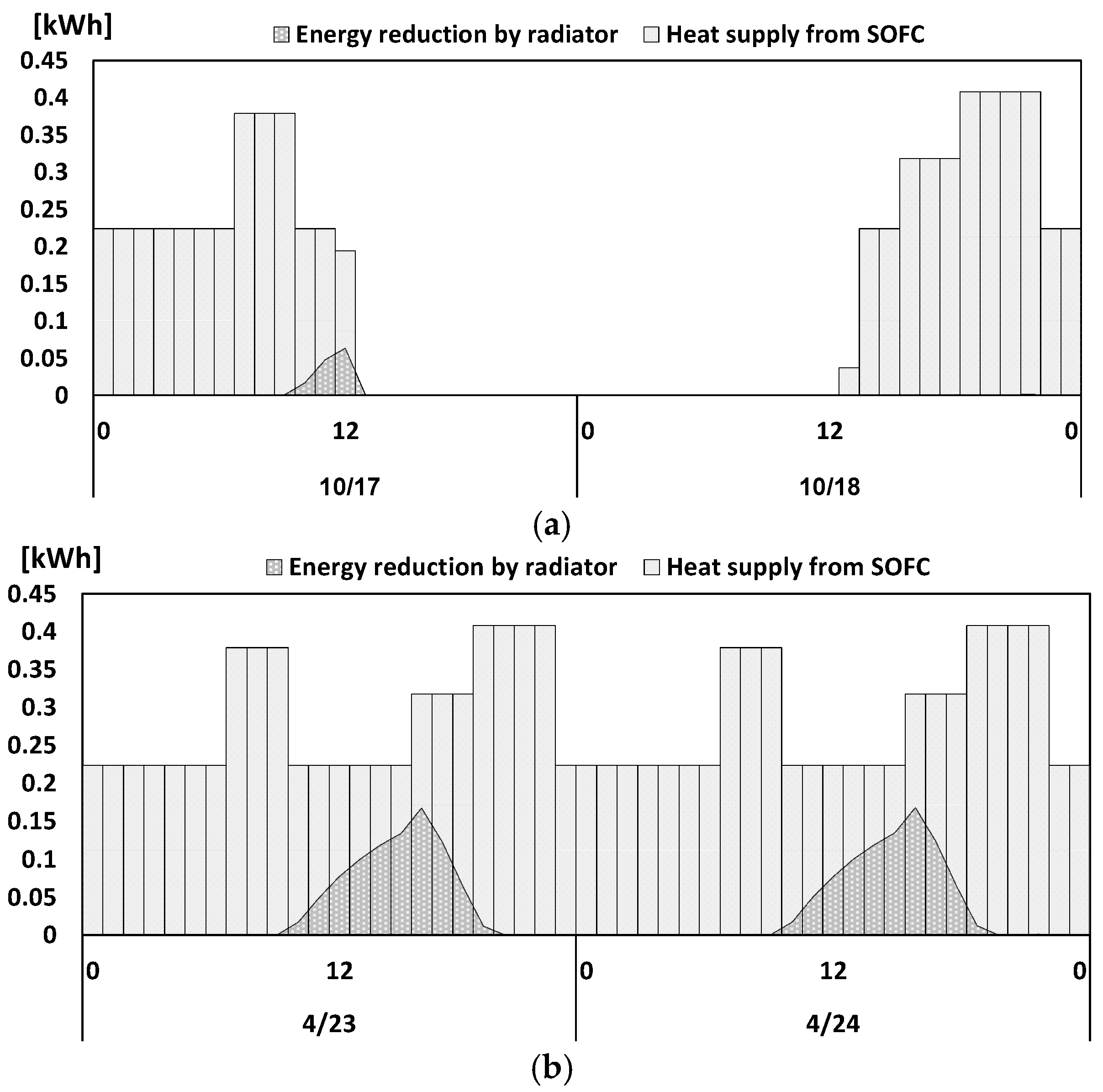

3.3. Simulation of SOFC-CGS with Solar Energy System

4. Discussion

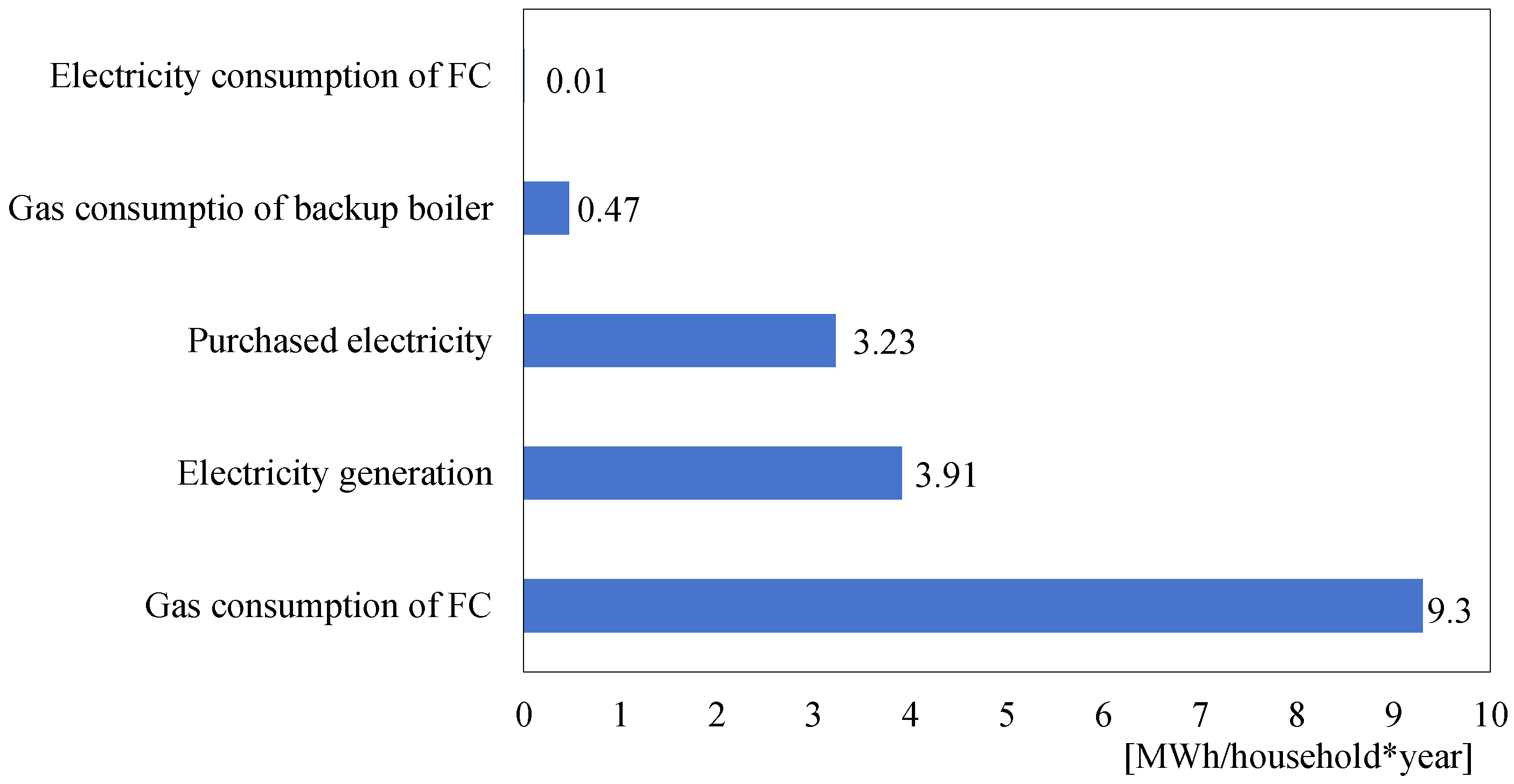

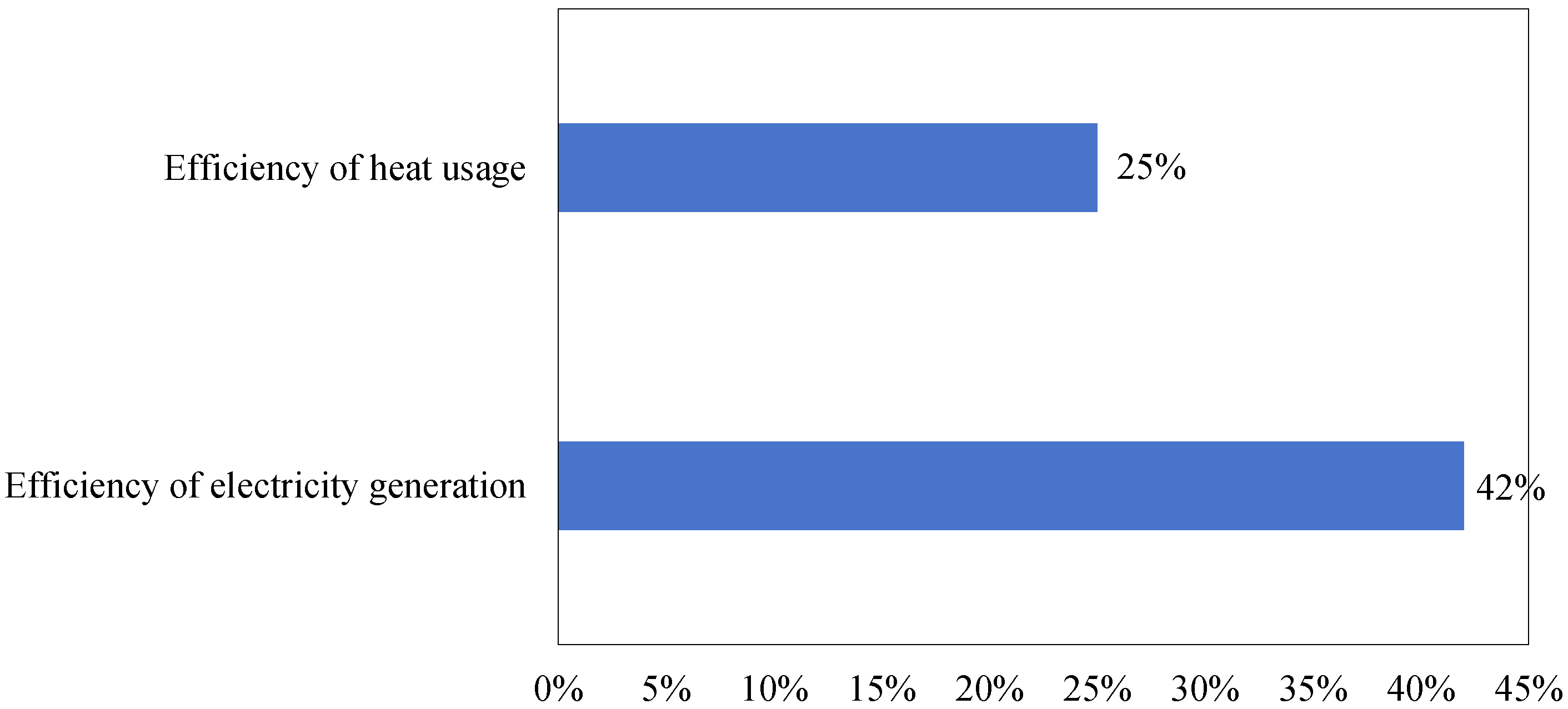

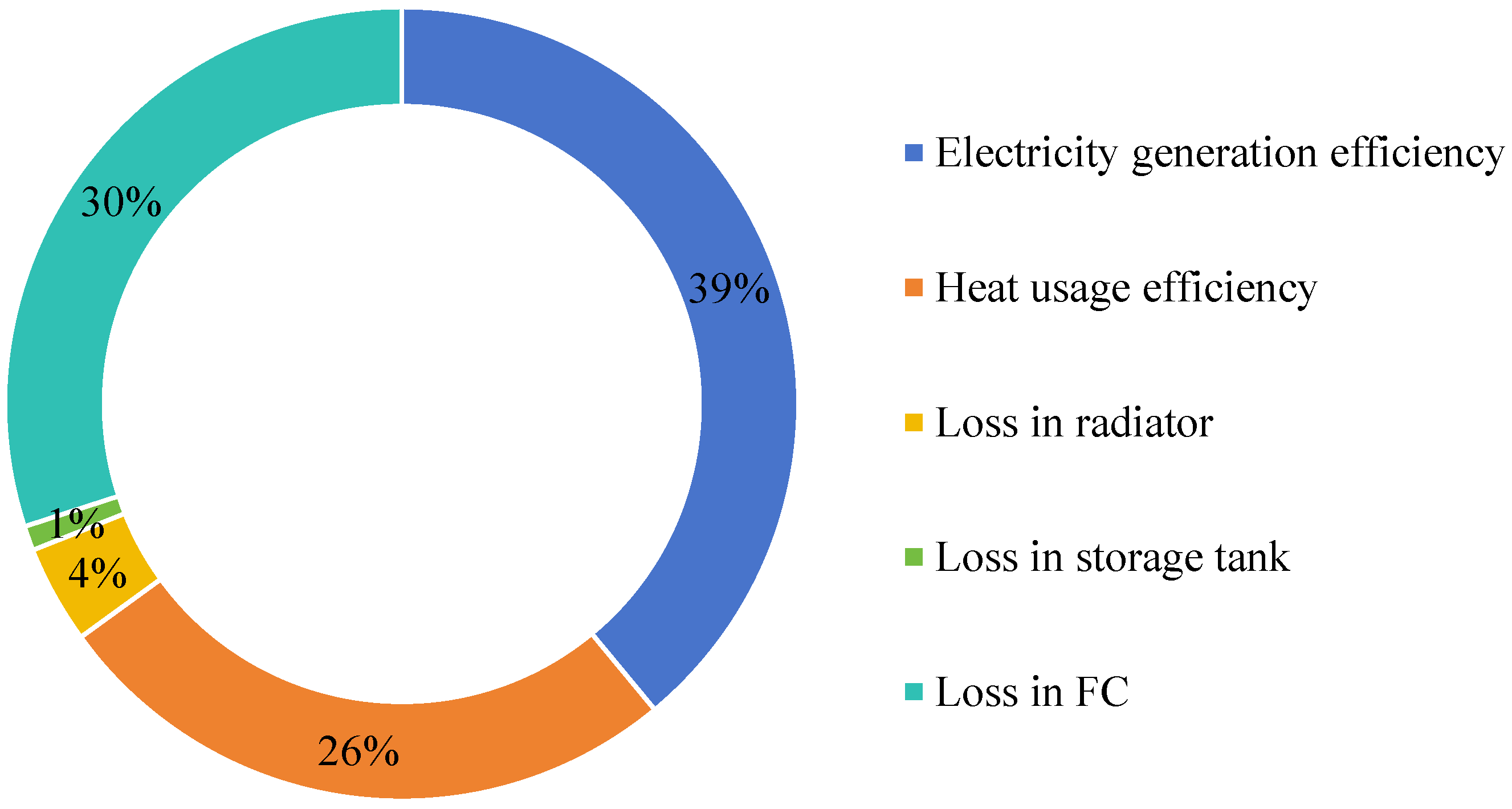

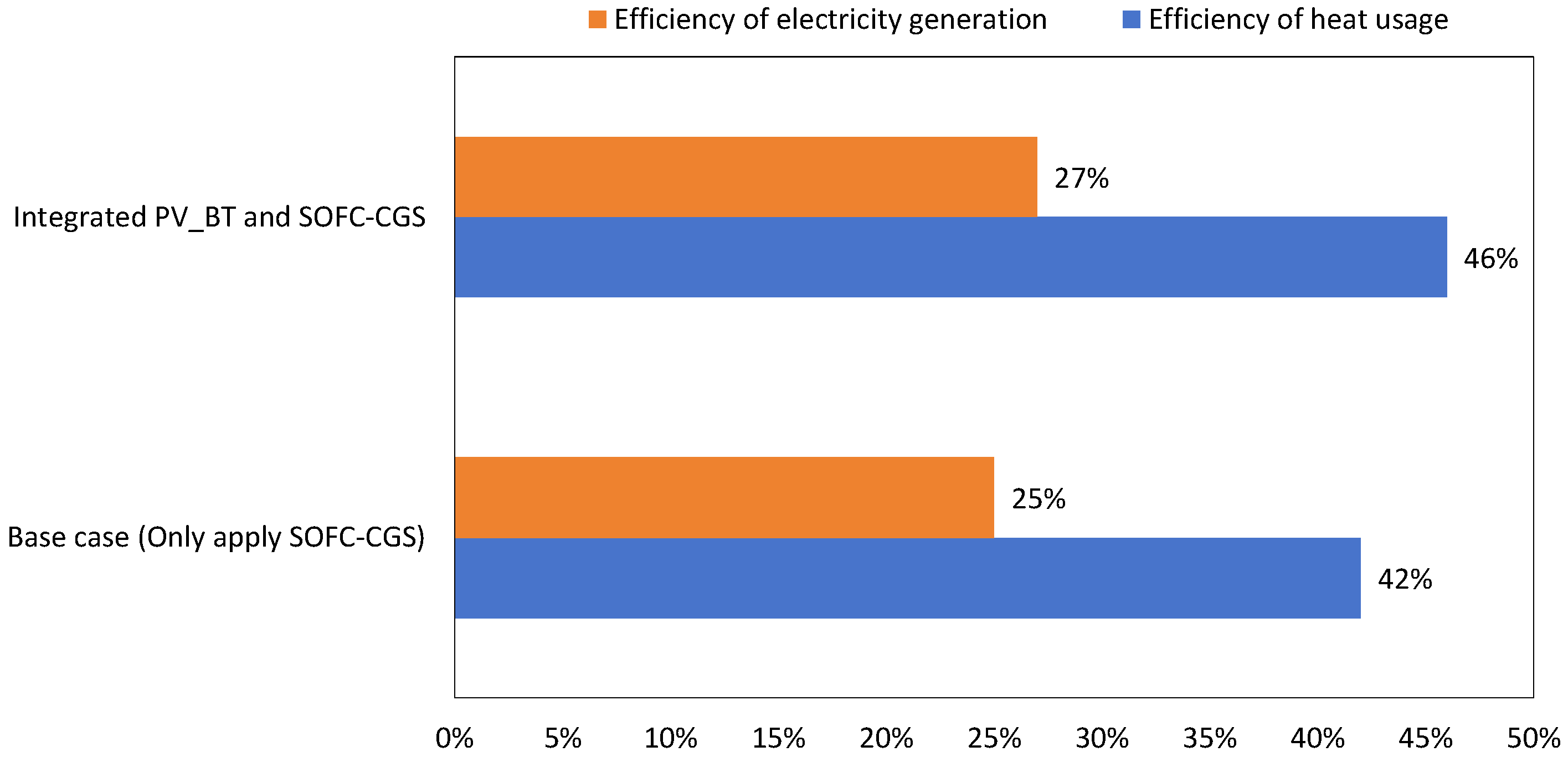

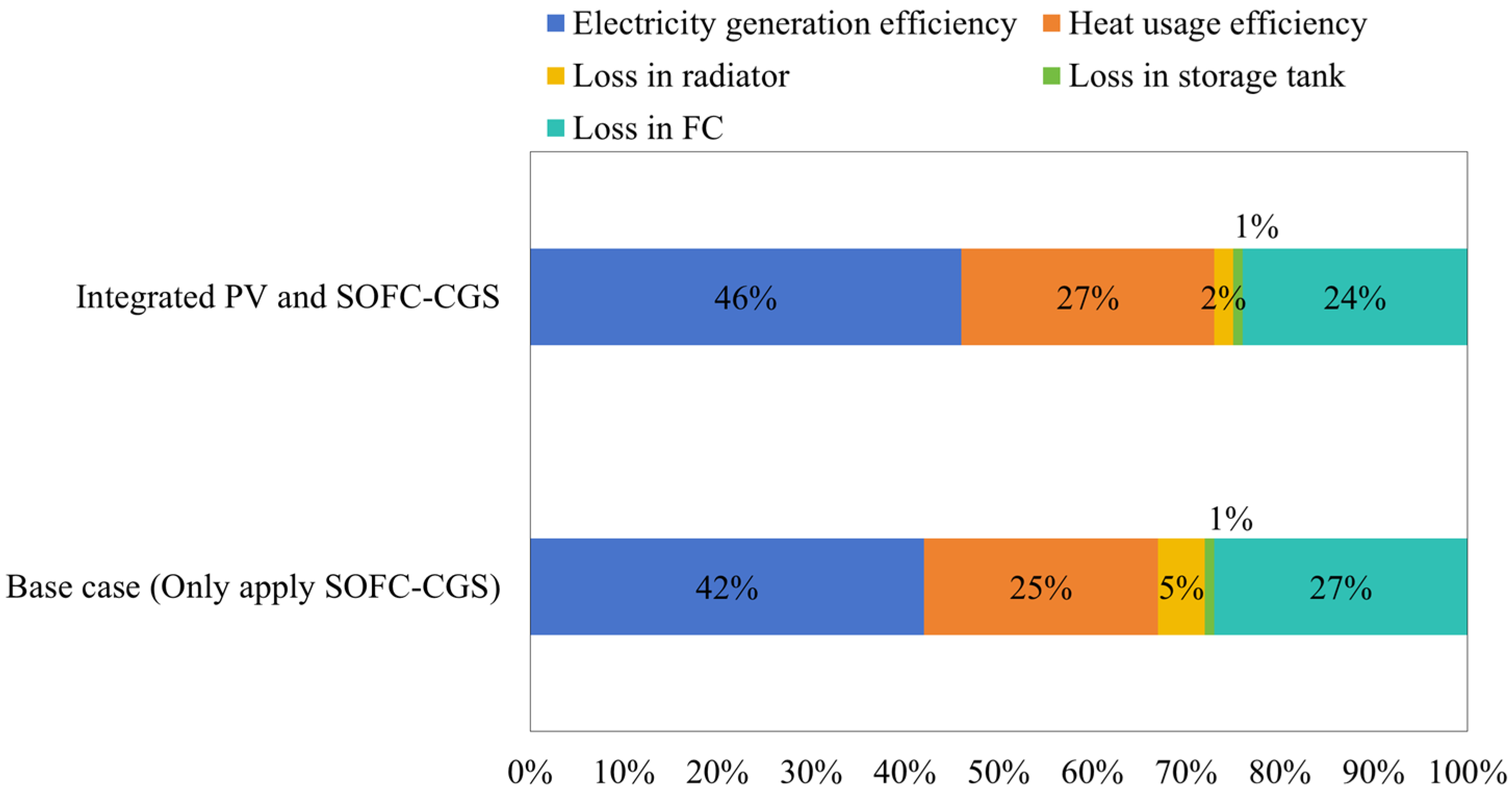

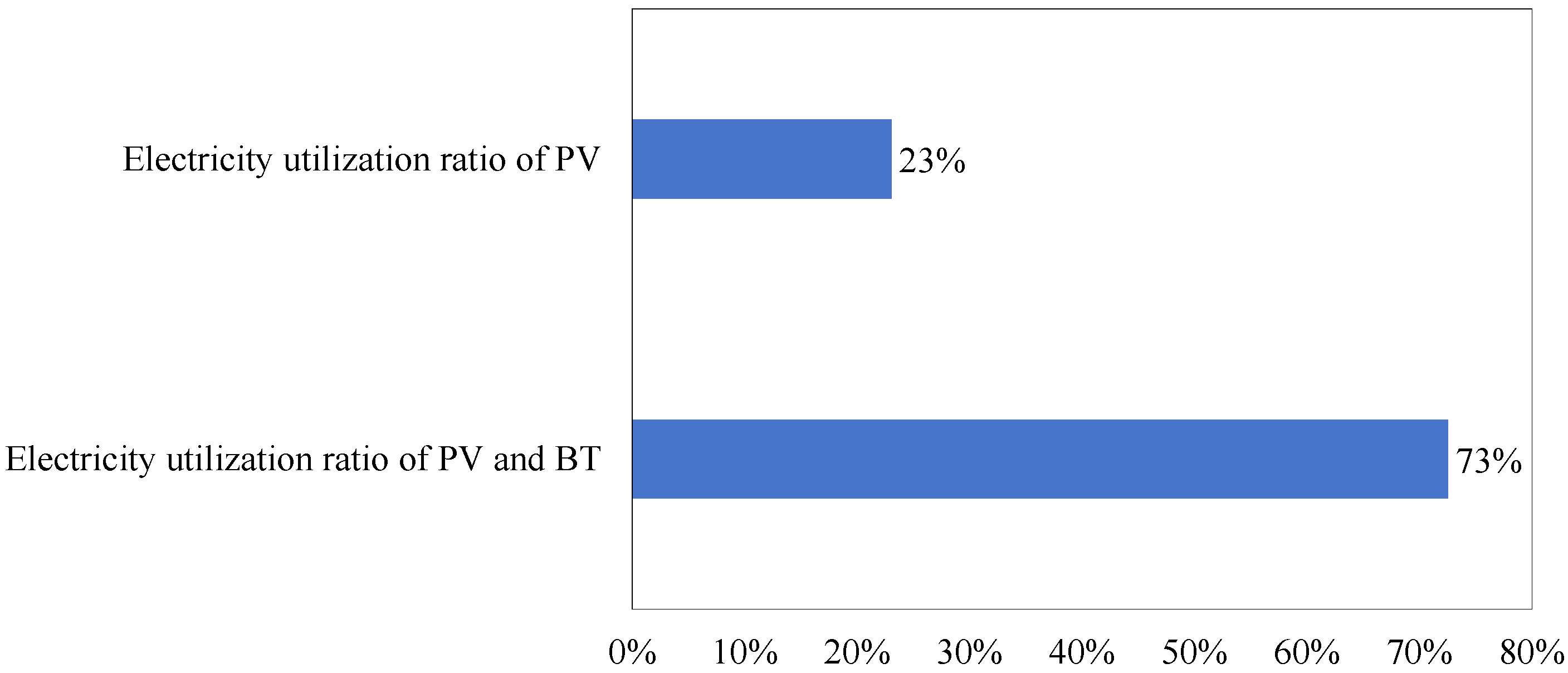

4.1. Energy Performance of Applying Standalone SOFC-CGS

4.2. Economic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moradmand, A.; Dorostian, M.; Shafai, B. Energy scheduling for residential distributed energy resources with uncertainties using model-based predictive control. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 132, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guerrero, J.; Chen, Z.; Blaabjerg, F. Distributed energy resources in grid interactive AC microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG 2010), Hefei, China, 16–18 June 2010; IEEE Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.G.; Værbak, M.; Rasmussen, R.K.; Jørgensen, B.N. Distributed Energy Resource Adoption for Campus Microgrid. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN 2019), Helsinki, Finland, 22–25 July 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, S.; Park, J.S. Comparison and optimization of operating conditions in power generation integrated with thermal energy storage systems. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 69, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Duan, L.; Wang, Z.; Ren, Y. Integration optimization of integrated solar combined cycle (ISCC) system based on system/solar photoelectric efficiency. Energies 2023, 16, 3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, R.N.; Hendriksen, P.V.; Frandsen, H.L. Optimization of energy systems sizing and operation including heat integration and storage. In Proceedings of the ECOS 2023—The 36th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 25–30 June 2023; Available online: https://www.proceedings.com/content/069/069564-0125open.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Energy optimization of stand-alone electrical grid considering the optimal performance of the hydrogen storage system and consumers. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2024, 71, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidu, Z. What Is Baidu Zhidao and How to Get Started, Chinafy. Available online: https://www.chinafy.com/china-tech/what-is-baidu-zhidao-and-how-to-get-started (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Bornemann, L.; Lange, J.; Kaltschmitt, M. Optimizing temperature and pressure in PEM electrolyzers: A model-based approach to enhanced efficiency in integrated energy systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 325, 119338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnawafah, H.; Alnawafah, Q.; Al Sotary, O.; Amano, R.S. Design and optimization of a lab-scale system for efficient green hydrogen production using solar energy. Int. J. Energy Effic. Eng. 2025, 1, 65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Karanafti, A.; Theodosiou, T.; Tsikaloudaki, K. Assessment of buildings’ dynamic thermal insulation technologies—A review. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 119985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Peña, J.; Cadena-Zarate, C.; Parrado-Duque, A.; Osma-Pinto, G. Distributed energy resources on distribution networks: A systematic review of modelling, simulation, metrics, and impacts. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 138, 107900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, G.; Feng, W.; Stadler, M.; Steinbach, J.; Lai, J.; Zhou, N.; Marnay, C.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, J.; Tian, Z.; et al. Regional analysis of building distributed energy costs and CO2 abatement: A U.S.—China comparison. Energy Build. 2014, 77, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.D.; Smith, D.E.; Borca-Tasciuc, D.-A. Performance of wedge-shaped luminescent solar concentrators employing phosphor films and annual energy estimation case studies. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Tsetis, I.; Maghsudi, S. Distributed Management of Fluctuating Energy Resources in Dynamic Networked Systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagananda, R.; Gopiya Naik, S. Optimal power flow management in microgrids using distributed energy resources. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1295, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Dong, B.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Thorin, E. Technology selection for capturing CO2 from wood pyrolysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 266, 115835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Jia, F.; Chen, L.; Yan, F. Assurance process for sustainability reporting: Towards a conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmann, M.; Madlener, R. Assessing local power generation potentials of photovoltaics, engine cogeneration, and heat pumps: The case of a major Swiss city. Energies 2021, 14, 5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeiras, F.; Pinheiro, E.; Gomes, M.; Coelho, P.; Fernandes, J. Review of the cooperation and operation of microgrid clusters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Deng, W.; Beccarelli, P.; Lun, I.Y.F. Thermal comfort investigation of rural houses in China: A review. Build. Environ. 2023, 235, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Study on suitable heating pattern of rural residences in Shaanxi Province, China. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development (ICEESD 2018), Shenzhen, China, 30–31 March 2018; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2018; Volume 163, pp. 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ember. China Energy Transition Review 2025. 2025. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2025/09/China-Energy-Transition-Review-2025.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- China National Institute of Standardization. White Paper on Energy Efficiency Status of Energy-Using Products in China (2011); Zhou, N., Romankiewicz, J., Fridley, D., Eds. and Translators; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xr643c8 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- El-Hamalawy, A.F.; Farag, H.E.Z.; Asif, A. Optimal design and technology selection for electrolyzer hydrogen plants considering hydrogen supply and provision of grid services. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2025, 16, 2327–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, H.; Pandey, Y.; Md Kabir, I.; Chattopadhyay, S. Bridging complexity and accessibility: A novel model for PV and BESS capacity estimation in rural microgrids near the equatorial region. e-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 14, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestipino, M.; Corigliano, O.; Galvagno, A.; Piccolo, A.; Fragiacomo, P. Exploring the potential of wet biomass gasification with SOFC and ICE cogeneration technologies: Process design, simulation and comparative thermodynamic analysis. Appl. Energy 2025, 392, 125998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ye, Z.; Ni, P.; Cao, C.; Wei, X.; Zhao, J.; He, X. Intelligent Digital Twin Modelling for Hybrid PV-SOFC Power Generation System. Energies 2023, 16, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Muyeen, S.M.; Lin, S. Optimizing microgrid efficiency: Coordinating commercial and residential demand patterns with shared battery energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 88, 111485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.; Ghandehariun, S.; Siavashi, M. Solar-to-power generation via fuel cells: A state-of-the-art review of hybrid conversion systems. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 28, 101310. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, P.; Mo, W.; Jiao, Z.; Gao, W. A multi-objective approach to optimizing the geometry and envelope of rural dwellings for energy demand, thermal comfort, and daylight in cold regions of China: A case study of Shandong province. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322, 119128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiang, J.; Lin, H.; Li, Y. Comprehensive rural distribution network optimization: Tailored demand-side management via multi-agent deep reinforcement learning coupled with distributionally robust stochastic models. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 82, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Sheikh, M.R.I.; Biswas, D.; Mamun, A.A.; Hossen, M.J. Optimizing renewable energy-based grid-connected hybrid microgrid for residential applications in Bangladesh: Predictive modeling for renewable energy, grid stability and demand response analysis. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerloff, N. Comparative life-cycle assessment analysis of power-to-methane plants including different water electrolysis technologies and CO2 sources while applying various energy scenarios. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 10123–10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Barrington-Leigh, C.P.; Robinson, B.E. Rural household energy transition in China: Trends and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palone, O.; Cosentini, C.; Conti, M.; Gagliardi, G.; Cedola, L.; Borello, D. Techno-economic comparison of Power-to-Gas systems using solid oxide and anion exchange membrane carbon dioxide/water electrolysers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 345, 120370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solargis. Global Solar Atlas. 2025. Available online: https://globalsolaratlas.info/map?c=-9.275622 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Wu, Q.; Gao, W. Research on passive design optimization about an experimental rural residence in hot summer and cold winter region of China. J. Build. Constr. Plan. Res. 2016, 4, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Hou, Y.; Lee, I.; Liu, T.; Acharya, T.D. Feasibility study and passive design of nearly zero energy building on rural houses in Xi’an, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlanta: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). Energy Efficient Design for Low-Rise Residential Buildings: ASHRAE Standard 90.1-2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/file%20library/technical%20resources/standards%20and%20guidelines/standards%20addenda/90_2_2018_q_20240531.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Mazzeo, D.; Matera, N.; Cornaro, C.; Oliveti, G.; Romagnoni, P.; De Santoli, L. EnergyPlus, IDA ICE and TRNSYS predictive simulation accuracy for building thermal behaviour evaluation by using an experimental campaign in solar test boxes with and without a PCM module. Energy Build. 2020, 212, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Lee, I.-H. Environmental and efficiency analysis of simulated application of the solid oxide fuel cell co-generation system in a dormitory building. Energies 2019, 12, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Lee, I.; Zhai, B.Q.; Yang, Y.J. Proposing strategies for efficiency improvement by using a residential solid oxide fuel cell co-generation system in a small-scale apartment building. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 788097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Energy Storage Network. 2025. Available online: https://www.escn.com.cn/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Lee, T.; Choi, J.; Park, T.; Choi, H.; Yoo, Y. Development and performance test of SOFC co-generation system for RPG. In Proceedings of the Korean Society for New & Renewable Energy Conference, LOTTE HOTEL JEJU, Seogwipo-si, Jeju-do, Republic of Korea, 25–27 June 2009; pp. 361–364. Available online: https://koreascience.kr/article/CFKO200935161993538.page (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Chen, W.; Shen, H. Applying research of storage batteries in photovoltaic system. Chin. Labat Man 2006, 43, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Sumiyoshi, D.; Okuda, Y.; Akashi, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Watanabe, T. Study on the optimal specification of solid oxide fuel cells for apartment buildings and proposal for reduction of hot-water storage tank capacity using bathtubs. J. Archit. Plan. (Trans. AIJ) 2015, 80, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Time and Date. Climate & Weather Averages in Xi’an, Shaanxi, China. 2025. Available online: https://www.timeanddate.com/weather/china/sian/climate (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Li, B.; You, L.; Zheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Energy consumption pattern and indoor thermal environment of residential building in rural China. Energy Built Environ. 2020, 1, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance’s Notice on Renewable Energy Price Subsidies for 2025. 2025. Available online: http://www.mof.gov.cn/zyyjsgkpt/zyddfzyzf/zfxjjzyzf/kzsnydjfjsr/202506/t20250616_3965787.htm (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Whiston, M.M.; Lima Azevedo, I.M.; Litster, S.; Samaras, C.; Whitefoot, K.S.; Whitacre, J.F. Paths to market for stationary solid oxide fuel cells: Expert elicitation and a cost of electricity model. Appl. Energy 2021, 304, 117641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEO China. PV Module Shortage and Price Increase Reappeared. 2025. Available online: http://www.eeo.com.cn/2025/0815/744999.shtml (accessed on 27 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Huaniu Network. Lead-Acid Battery Price Information. 2025. Available online: http://www.chinahuaniu.cn/jiage/14379.html (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- International Energy Network Team. Distributed PV Electricity Subsidies up to 0.45 RMB: Summary of New Energy Policies in 27 Provinces. Sina Finance, 20 May 2023. Available online: https://finance.sina.cn/2023-05-20/detail-imyumrzu3040502.d.html (accessed on 27 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Digital Energy Storage Network News Center. Overview of Provincial New Energy Storage Subsidy Requirements in 2023. ESCN. 2023. Available online: https://www.escn.com.cn/news/show-1584451.html (accessed on 27 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- China Energy Storage Network News Center. Details of Regional Energy Storage Subsidy Policies. ESCN. 2023. Available online: https://www.escn.com.cn/news/show-1544524.html (accessed on 27 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Xi’an Bendibao. Rural and Residential Electricity Tariff Standards in Xi’an for 2025. 2025. Available online: https://m.xa.bendibao.com/live/116360.shtm (accessed on 27 November 2025). (In Chinese).

| Tools | Used For |

|---|---|

| Python, Visual Basic.Net | Development of dynamic models of clean energy systems |

| Visual Basic 17.0 for Applications, Microsoft Access | Data organizing |

| Input Data | Unit/Value |

|---|---|

| Electricity demand | kW |

| Hot water demand | L/Time unit |

| Setting temperature of backup boiler | 40 °C |

| Ambient temperature | Data from ASHRAE |

| Temperature of city water | 15 °C |

| Temperature of hot water demand | 40 °C |

| Device Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| Efficiency of converting solar energy to electricity | 0.2 |

| Coefficient of loss by ambient temperature | In summer (June to September):0.9 In winter (November to February): 0.95 In other seasons: 0.92 |

| Coefficient of loss by changing direct current to alternating current | 0.95 |

| Coefficient of other losses | 0.95 |

| Device Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| Maximum output capacity | 2 kW |

| Maximum charge capacity | 2 kW |

| Rate of charge loss | 10% |

| Rate of output loss | 10% |

| Rate of time loss | 5%/month |

| Size of PV | Size of BT | Fuel Cell |

|---|---|---|

| 50 m2 | 12 kWh | SOFC-CGS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hou, Y.; Chang, H.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wan, S. Energy Performance Evaluation and Optimization of a Residential SOFC-CGS in a Typical Passive-Designed Village House in Xi’an, China. Buildings 2026, 16, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010059

Hou Y, Chang H, Fan Y, Zhang X, Xiong Y, Zhang B, Wan S. Energy Performance Evaluation and Optimization of a Residential SOFC-CGS in a Typical Passive-Designed Village House in Xi’an, China. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Yaolong, Han Chang, Yidan Fan, Xiangxue Zhang, Yuxuan Xiong, Bo Zhang, and Sanhe Wan. 2026. "Energy Performance Evaluation and Optimization of a Residential SOFC-CGS in a Typical Passive-Designed Village House in Xi’an, China" Buildings 16, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010059

APA StyleHou, Y., Chang, H., Fan, Y., Zhang, X., Xiong, Y., Zhang, B., & Wan, S. (2026). Energy Performance Evaluation and Optimization of a Residential SOFC-CGS in a Typical Passive-Designed Village House in Xi’an, China. Buildings, 16(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010059