Optimization of Activator Modulus to Improve Mechanical and Interfacial Properties of Polyethylene Fiber-Reinforced Alkali-Activated Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

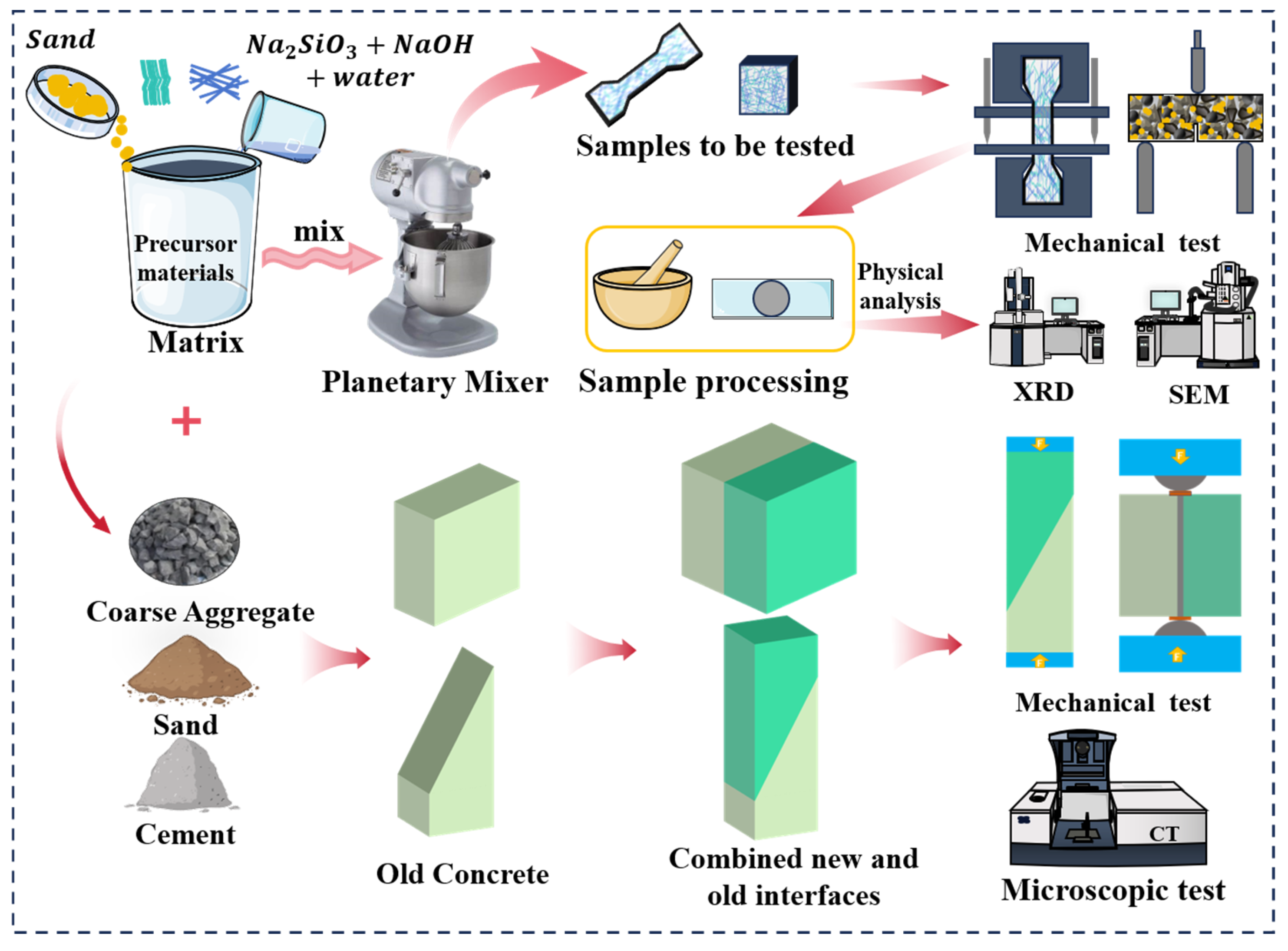

2. Materials and Methods

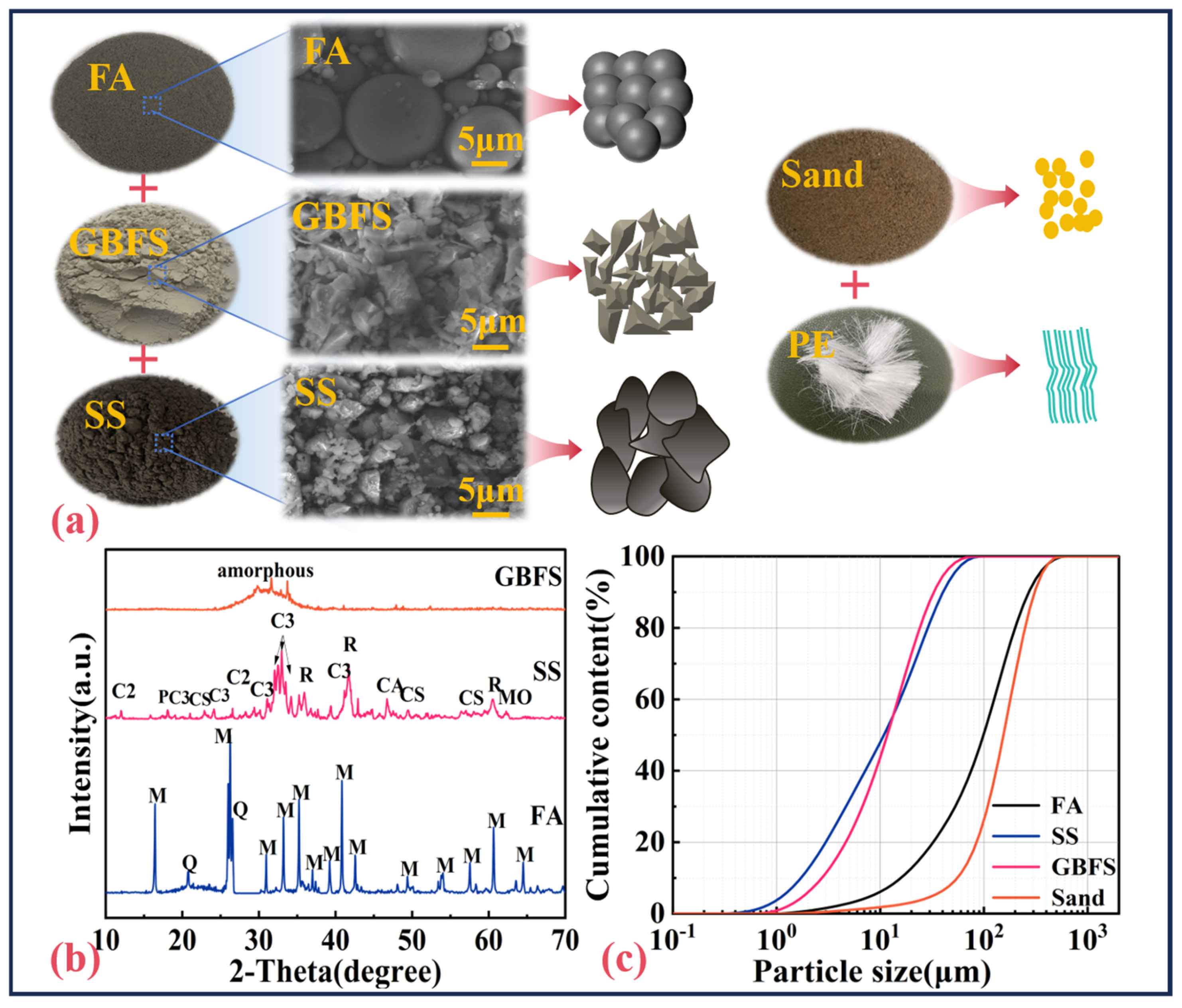

2.1. Raw Materials

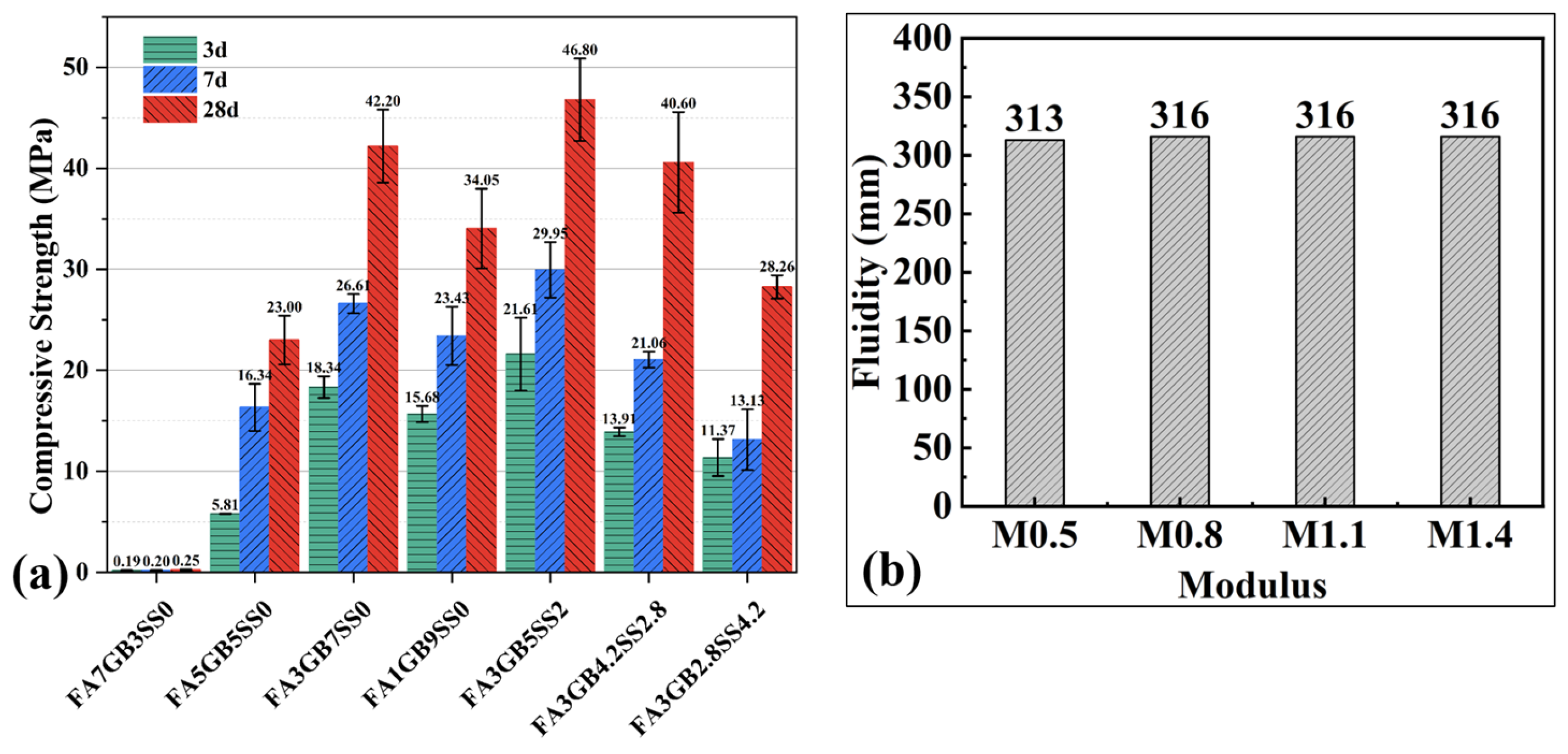

2.2. Mix Design and Sample Preparation

2.3. Methods

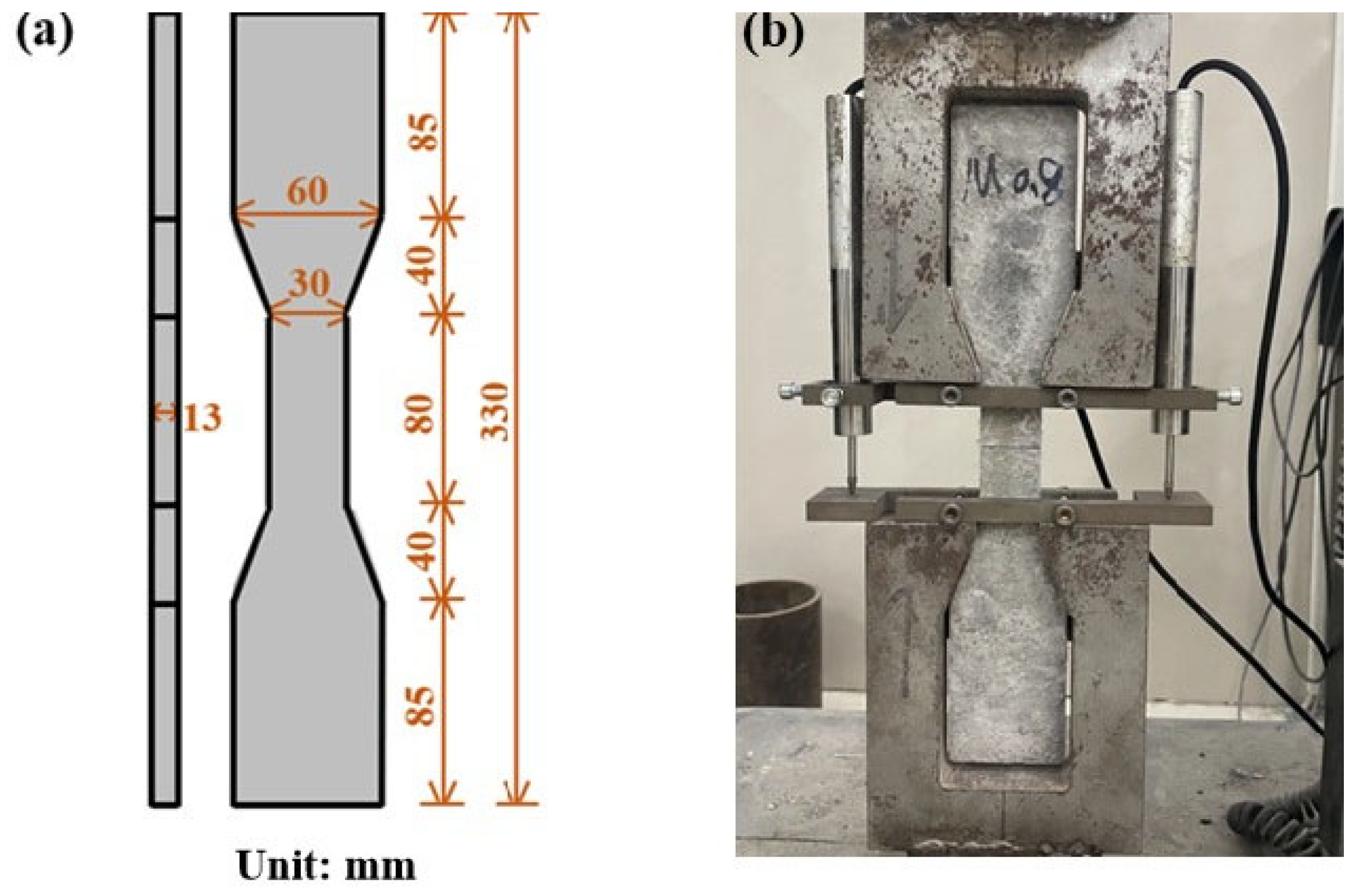

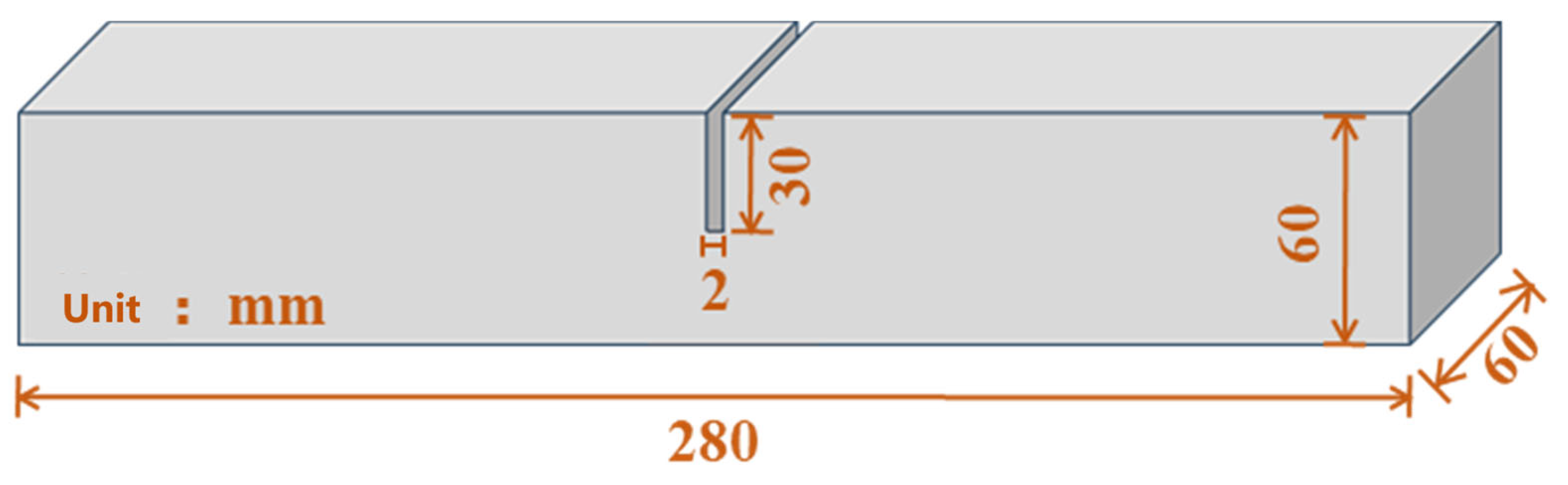

2.3.1. Uniaxial Tension Test

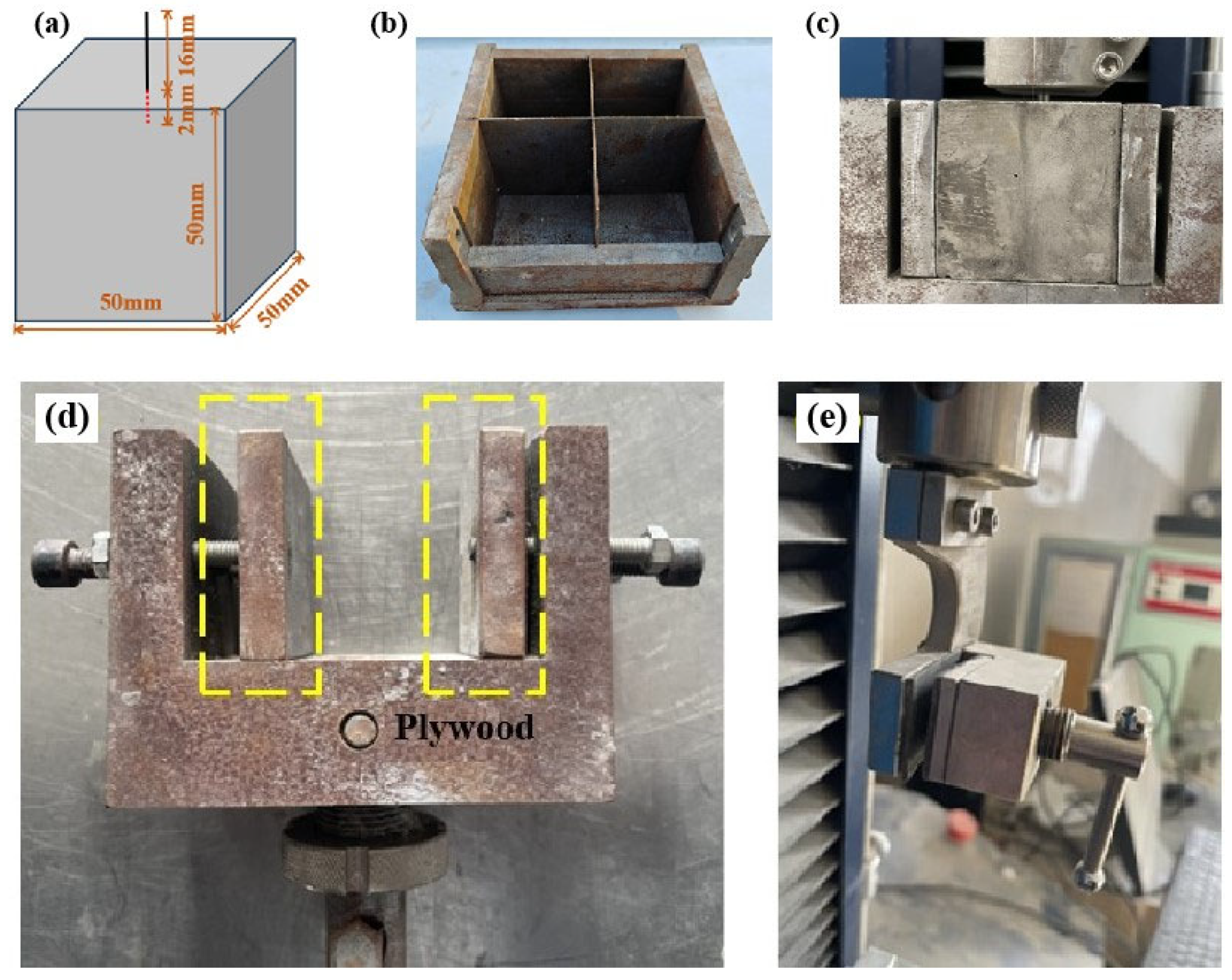

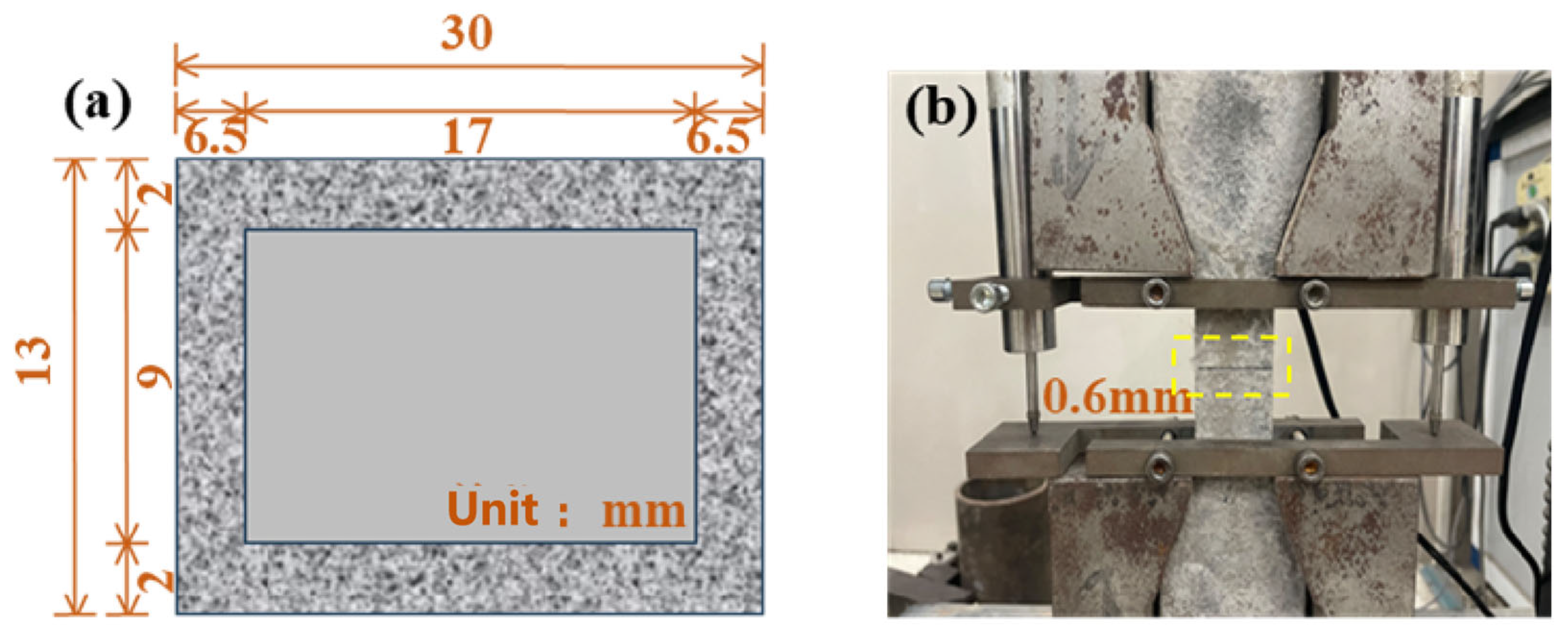

2.3.2. Fiber Pull-Out Test

2.3.3. Strain-Hardening Stress Criterion and Energy Criterion

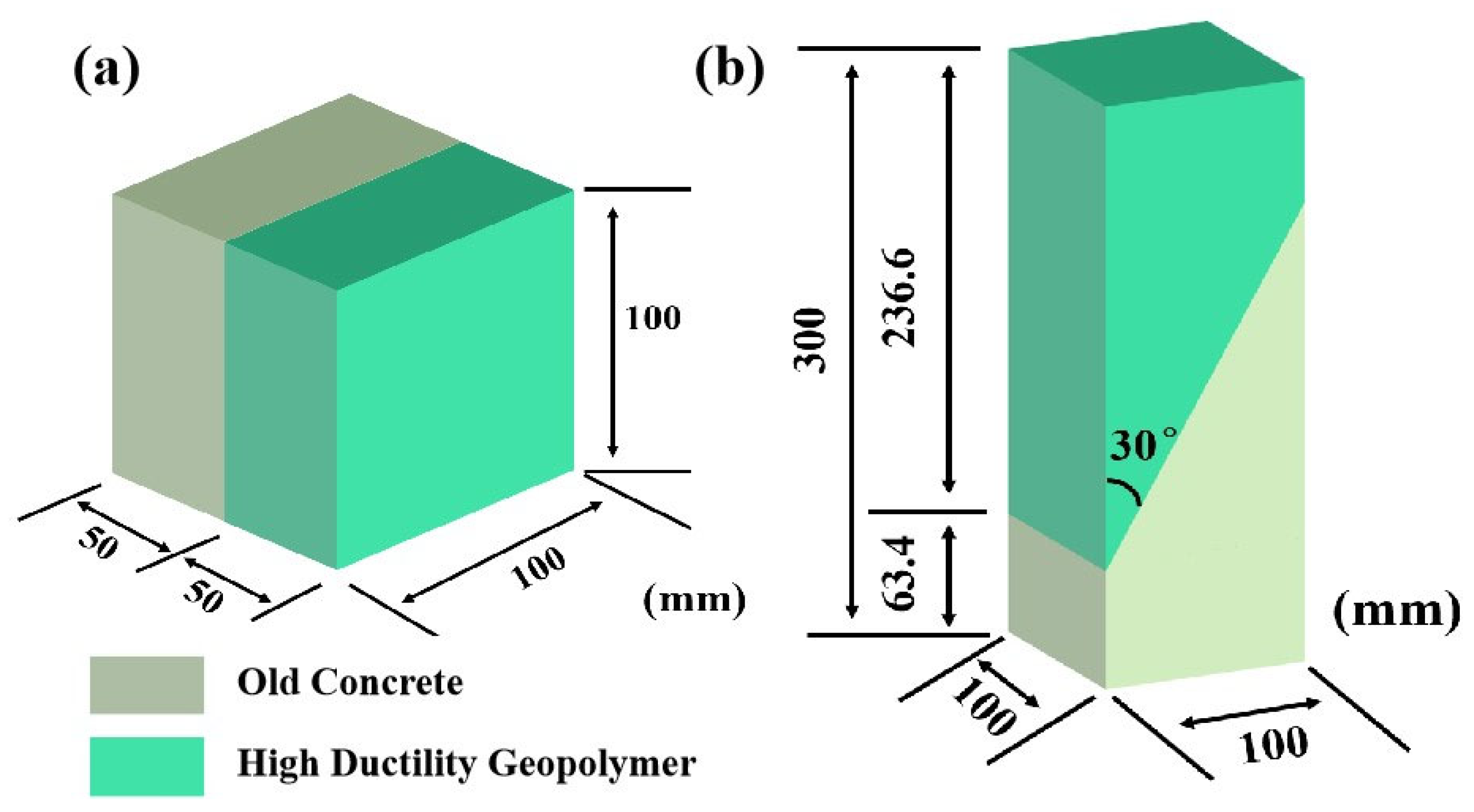

2.3.4. Shear and Splitting Tensile Tests

2.3.5. Phase Composition Analysis

2.3.6. Porosity Determination

2.3.7. SEM Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Properties

3.1.1. Uniaxial Tensile Strength

3.1.2. Stress–Strain Behavior

3.2. Interfacial Bonding Behavior

3.3. Microstructure Analysis

3.3.1. Interface Morphology and Phases

3.3.2. Fiber-Matrix Interface

3.4. Strain-Hardening Criteria

3.5. Interfacial Behavior of Alkali-Activated Materials

3.5.1. Bonding Behavior

3.5.2. Pore Structure

4. Conclusions

- The activator modulus significantly affects the tensile properties of AAM. At Ms = 1.1, the composite achieved the maximum tensile strength (3.77 MPa) and ultimate tensile strain (3.68%) at 28 days, corresponding to increases of 231% and 64.6% compared with Ms = 0.

- AAM with Ms around 1.1 exhibited stable strain-hardening behavior and multiple fine cracks, confirming effective fiber bridging and stress redistribution. This ductility makes the material suitable for applications requiring crack and seismic resistance.

- Single-fiber pull-out tests revealed that Ms = 1.1 provided optimal interfacial frictional bond strength, facilitating controlled fiber pull-out rather than premature rupture. This mechanism enables fibers to bridge more cracks and sustain tensile loading.

- Slant shear and splitting tensile tests showed that Ms strongly influences interfacial bonding with concrete. Moderate moduli (1.0–1.1) ensured strong adhesion and balanced composite strength, while excessive modulus (1.4) led to porous ITZ and degraded bond performance.

- Future studies should explore long-term durability and volume stability under service conditions, investigate the comprehensive effects of various fibers and additives, and conduct large-scale and field studies to further validate and broaden engineering applications. In addition, quantitative or semi-quantitative characterization beyond qualitative XRD is needed to better substantiate amorphous gel formation and phase assemblage in alkali-activated systems. In addition, field-relevant curing conditions, including temperature fluctuations, early-age drying, and wetting–drying cycles, should be systematically considered, because moisture and thermal variations may affect shrinkage-induced microcracking and the AAM–concrete interfacial bond, potentially shifting the optimum Ms window identified under controlled laboratory curing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, V.C. On engineered cementitious composites (ECC): A review of the material and its applications. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2003, 1, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kewalramani, M.A.; Mohamed, O.A.; Syed, Z.I. Engineered Cementitious Composites for Modern Civil Engineering Structures in Hot Arid Coastal Climatic Conditions. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, N.; Praveenkumar, S. Influence of supplementary cementitious materials, curing conditions and mixing ratios on fresh and mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 309, 125038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balea, A.; Fuente, E.; Blanco, A.; Negro, C. Nanocelluloses: Natural-based materials for fiber-reinforced cement composites. A critical review. Polymers 2019, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Xi, B.; Sui, L.; Zheng, S.; Xing, F.; Li, L. Development of high strain-hardening lightweight engineered cementitious composites: Design and performance. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cai, J.; Xu, L.; Ma, X.; Pan, J. Mechanical and environmental performance of engineered geopolymer composites incorporating ternary solid waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 141065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Pan, J.; Leung, C.K.Y. Mechanical Behavior of Fiber-Reinforced Engineered Cementitious Composites in Uniaxial Compression. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 27, 04014111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, W.; O’Neill, E.; Guo, Z. Differential scanning calorimetry study of ordinary Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 1487–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasuriya, C.; Vimonsatit, V.; Dias, W.P.S. Performance based energy, ecological and financial costs of a sustainable alternative cement. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhong, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Engineering properties and sustainability assessment of recycled fibre reinforced rubberised cementitious composite. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B.; Adak, D.; Kapoor, K.; Tabish, M. Low carbon concrete: Advancements, challenges and future directions in sustainable construction. Discov. Concr. Cem. 2025, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Gamil, Y.; Iftikhar, B.; Murtaza, H. Towards modern sustainable construction materials: A bibliographic analysis of engineered geopolymer composites. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1277567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Q. Engineering and microstructural properties of carbon-fiber-reinforced fly-ash-based geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Mao, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zheng, J.; Hu, S.; Wang, K. A critical review on modeling and prediction on properties of fresh and hardened geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 88, 109184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, A.; Verre, S.; Micelli, F.; Aiello, M.A. Durability-aimed performance of glass FRCM-confined concrete cylinders: Experimental insights into alkali environmental effects. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Feng, H.; Huang, H.; Guo, A.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y. Bonding Properties between Fly Ash/Slag-Based Engineering Geopolymer Composites and Concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, W.; Shi, G.; Lu, P. Effect of slag on the mechanical properties and bond strength of fly ash-based engineered geopolymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 164, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Lu, Y.; An, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, S. Multi-scale reinforcement of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/polyvinyl alcohol fibers on lightweight engineered geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Effect of sand content on engineering properties of fly ash-slag based strain hardening geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 34, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, M.; Li, V.C. An integrated design method of Engineered Geopolymer Composite. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 88, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Shi, C.; Yao, W.; Liang, G.; Song, J.; She, A. Electro-thermal actuation in recycled aggregate concrete with rapid self-reinforcement via smart cement-based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, J.-C.; Ma, R.-Y.; Xu, L.-Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.-N.; Yao, J.; Wang, Y.-S.; Xie, T.-Y.; Huang, B.-T. Fly ash-dominated high-strength engineered/strain-hardening geopolymer composites (HS-EGC/SHGC): Influence of alkalinity and environmental assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaswanth, K.; Revathy, J.; Gajalakshmi, P. Strength, durability and micro-structural assessment of slag-agro blended based alkali activated engineered geopolymer composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, K.Z.; Johari, M.A.M.; Demirboğa, R. Impact of fiber reinforcements on properties of geopolymer composites: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-X.; Chen, G.; Pan, H.-s.; Wang, Y.-c.; Guo, Y.-c.; Jiang, Z.-x. Analysis of stress-strain behavior in engineered geopolymer composites reinforced with hybrid PE-PP fibers: A focus on cracking characteristics. Compos. Struct. 2023, 323, 117437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M. Effect of steel fibers on geopolymer properties—The best synopsis for civil engineer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 246, 118534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefaei, Y.; Dai, J.-G. Tensile behavior and microstructure of hybrid fiber ambient cured one-part engineered geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 184, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-P.; Feng, R.; Quach, W.-M.; Zeng, J.-J. Evaluation of flexural performance on corrosion-damaged RC beams retrofitted with UHPFRCC under marine exposure. Eng. Struct. 2025, 333, 120193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-P.; Feng, R.; Quach, W.-M.; Zeng, J.-J. Axial compressive behaviour of simulated corrosion-damaged RC columns retrofitted with UHPFRC jackets subjected to dry-wet cycling condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 424, 135956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tang, J.-P.; Feng, R.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, J.-H. Tensile behavior and flexural performance of polarized CFRCM-strengthened corroded RC continuous beams. Structures 2025, 76, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Feng, R.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, J.-H. Compressive behavior of seawater sea sand concrete (SSC) composite columns with dual-functional C-FRCM jacket under eccentric loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 502, 144450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.H.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, M.; Kazmi, S.M.S.; Zhu, Z.; Shamim, A. Mechanical properties and durability of ECC incorporating LC3 and RFA in chloride environment. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zou, Y. Flexural performance of damaged RC beams strengthened with UHPC: Coupling effect of load-induced cracking and chloride corrosion. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 115, 114627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Kong, D.; Zhang, J. Effect of activator modulus on the interfacial bonding behavior between high ductility geopolymer composites and concrete substrate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 487, 142149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaoui, A.; Ben Rejeb, Z.; Park, C.B. Surface-engineered in-situ fibrillated thermoplastic polyurethane as toughening reinforcement for geopolymer-based mortar. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 283, 111623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, K.; Chang, J. Synthesis process-based mechanical property optimization of alkali-activated materials from red mud: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B.; Sui, Z.-Q.; Corke, H. Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): An updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 924–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Shi, C. Elucidating the effect of modulus of sodium silicate on microstructural and mechanical properties of alkali activated slag pastes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2026, 166, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Zhang, M. Engineered geopolymer composites: A state-of-the-art review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 135, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Cao, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D. Thermo-mechanical optimization of alkali activated materials: Synergistic fiber strategy for high-temperature toughness retention. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Liao, H.; Cheng, F.; Song, H.; Yang, H. Investigation into the synergistic effects in hydrated gelling systems containing fly ash, desulfurization gypsum and steel slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, K.-M. Influence of Na2O content and Ms (SiO2/Na2O) of alkaline activator on workability and setting of alkali-activated slag paste. Materials 2019, 12, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.; Gismera, S.; Alonso, M.d.M.; De Lacaillerie, J.d.E.; Lothenbach, B.; Favier, A.; Brumaud, C.; Puertas, F. Early reactivity of sodium silicate-activated slag pastes and its impact on rheological properties. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 140, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liang, J.; Ye, G. Effect of the sodium silicate modulus and slag content on fresh and hardened properties of alkali-activated fly ash/slag. Minerals 2020, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, T.; Sreenivasan, H.; Abdollahnejad, Z.; Yliniemi, J.; Kantola, A.; Telkki, V.-V.; Kinnunen, P.; Illikainen, M. Influence of sodium silicate powder silica modulus for mechanical and chemical properties of dry-mix alkali-activated slag mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Mechanical Properties of Ordinary Concrete. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Yang, D.; Yan, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Li, J. Chloride threshold value and initial corrosion time of steel bars in concrete exposed to saline soil environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 120979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-I.; Lee, B.Y.; Ranade, R.; Li, V.C.; Lee, Y. Ultra-high-ductile behavior of a polyethylene fiber-reinforced alkali-activated slag-based composite. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 70, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Ma, Z.; Wang, B. Mechanical properties of hybrid fiber reinforced ternary-blended alkali-activated materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 366, 129841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Shi, R.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, X.; Wu, M. Feasibility study on using incineration fly ash from municipal solid waste to develop high ductile alkali-activated composites. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-I.; Kim, H.-K.; Lee, B.Y. Mechanical and fiber-bridging behavior of slag-based composite with high tensile ductility. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-I.; Nguyễn, H.H.; Cha, S.L.; Li, M.; Lee, B.Y. Composite properties of calcium-based alkali-activated slag composites reinforced by different types of polyethylene fibers and micromechanical analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-X.; Xu, L.-Y.; Huang, B.-T.; Weng, K.-F.; Dai, J.-G. Recent developments in Engineered/Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites (ECC/SHCC) with high and ultra-high strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 127956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, T.; Marar, K. Effects of crushed stone dust on some properties of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 1996, 26, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, I.; Henrist, C.; Liégeois, M.; Maseri, F.; Rulmont, A.; Cloots, R. (Micro)-structural comparison between geopolymers, alkali-activated slag cement and Portland cement. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 3789–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, P.; Sagoe-Crenstil, K.; Sirivivatnanon, V. Kinetics of geopolymerization: Role of Al2O3 and SiO2. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vargas, A.S.; Dal Molin, D.C.; Vilela, A.C.; Da Silva, F.J.; Pavao, B.; Veit, H. The effects of Na2O/SiO2 molar ratio, curing temperature and age on compressive strength, morphology and microstructure of alkali-activated fly ash-based geopolymers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; MacKenzie, K.J.; Brown, I.W. Crystalline phase formation in metakaolinite geopolymers activated with NaOH and sodium silicate. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 4668–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Li Victor, C. Interface Property and Apparent Strength of High-Strength Hydrophilic Fiber in Cement Matrix. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 1998, 10, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Ogawa, A.; Saito, T. Interface tailoring for strain-hardening polyvinyl alcohol-engineered cementitious composite (PVA-ECC). Mater. J. 2002, 99, 463–472. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, T.; Li, V.C. Practical Design Criteria for Saturated Pseudo Strain Hardening Behavior in ECC. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2006, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjithkumar, M.G.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Rajeshkumar, G. Characterization of sustainable natural fiber reinforced geopolymer composites. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 3691–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Ahmed, B.; El Ouni, M.H.; Ghazouani, N.; Chen, W. Microstructural and thermal characterization of polyethylene fiber-reinforced geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.Y.; Irshidat, M.R. Development of sustainable geopolymer composites for repair application: Workability and setting time evaluation. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.-h.; Liu, M.-h. Setting time and mechanical properties of chemical admixtures modified FA/GGBS-based engineered geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 431, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | SO3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | 45.86 | 32.26 | 8.69 | 5.55 | 0.43 | 0.84 |

| GBFS | 25.45 | 12.76 | 0.37 | 50.36 | 5.03 | 2.01 |

| SS | 13.11 | 3.51 | 23.29 | 45.78 | 2.62 | 0.51 |

| Material | d10(μm) | d50(μm) | d90(μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA | 15.14 | 99.49 | 268.08 |

| GBFS | 2.76 | 11.91 | 32.46 |

| SS | 1.72 | 10.81 | 39.78 |

| Fiber | Ultimate Tensile Strength /MPa | Elastic Modulus /GPa | Diameter /mm | Length /mm | Density /g/cm3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 3100.000 | 122.000 | 0.025 | 18.000 | 0.970 |

| Cement | Sand | Aggregate | Water | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Splitting Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.84 | 3.27 | 0.54 | 37.65 | 3.86 |

| No. | Materials | Fiber | MS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | GBFS | SS | Water | River Sand | Sodium Hydroxide | Sodium Silicate | S/C | W/C | PE | ||

| kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | Vol./% | ||||

| M0 | 300 | 500 | 200 | 400 | 370 | 64.516 | 0.000 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 2.00 | 0.0 |

| M0.5 | 300 | 500 | 200 | 400 | 370 | 41.475 | 42.051 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 2.00 | 0.5 |

| M0.8 | 300 | 500 | 200 | 400 | 370 | 27.650 | 67.281 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 2.00 | 0.8 |

| M1.1 | 300 | 500 | 200 | 400 | 370 | 13.825 | 92.512 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 2.00 | 1.1 |

| M1.4 | 300 | 500 | 200 | 400 | 370 | 0.000 | 117.742 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 2.00 | 1.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, H.; Liu, D.; Guo, Y.; Jia, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J. Optimization of Activator Modulus to Improve Mechanical and Interfacial Properties of Polyethylene Fiber-Reinforced Alkali-Activated Composites. Buildings 2026, 16, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010057

Yang H, Liu D, Guo Y, Jia M, Zhu Y, Zhang J. Optimization of Activator Modulus to Improve Mechanical and Interfacial Properties of Polyethylene Fiber-Reinforced Alkali-Activated Composites. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Heng, Dong Liu, Yu Guo, Mingkui Jia, Yingcan Zhu, and Junfei Zhang. 2026. "Optimization of Activator Modulus to Improve Mechanical and Interfacial Properties of Polyethylene Fiber-Reinforced Alkali-Activated Composites" Buildings 16, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010057

APA StyleYang, H., Liu, D., Guo, Y., Jia, M., Zhu, Y., & Zhang, J. (2026). Optimization of Activator Modulus to Improve Mechanical and Interfacial Properties of Polyethylene Fiber-Reinforced Alkali-Activated Composites. Buildings, 16(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010057