1. Introduction

Train derailment accidents pose a serious threat to railway safety and can lead to substantial human and economic losses. Numerous studies indicate that derailments cannot be completely eliminated because they are influenced by factors that are difficult to control in practice, such as human error, adverse weather, and natural disasters [

1,

2,

3,

4]. With the rapid expansion of high-speed railway (HSR) systems, this challenge becomes more critical, as both the likelihood and consequences of derailment tend to increase with operating speed [

2,

4].

In addition, modern transportation infrastructure is increasingly assessed under accidental and extreme actions—including vehicle collisions with bridge barriers or bridge substructures, rockfall impacts at tunnel portals, and vessel–bridge collision scenarios—because these events may trigger highly localized damage and secondary hazards that threaten adjacent assets and occupants [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. For impact-resistant reinforced concrete (RC) structures, a key concern is not only global integrity but also local failure and debris-related hazards (e.g., fragment projection and secondary fragment impacts), which can significantly amplify risk beyond the impact zone [

10,

11,

12]. This broader safety context highlights the need for reliable, performance-based mitigation measures that can limit intrusion beyond the railway corridor and reduce secondary damage.

To mitigate derailment consequences, many studies have focused on understanding post-derailment train behavior and developing measures that restrain lateral vehicle motion. Three-dimensional dynamic models and wheel–sleeper contact models have been developed to simulate post-derailment trajectories [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], and a variety of onboard devices—such as L-shaped guides, post-derailment stoppers, and under-axle-box devices—have been proposed and experimentally validated [

18,

19,

20,

21]. By keeping the derailed train close to the track centerline, these devices can reduce the probability of vehicles leaving the track area and lessen secondary collisions with surrounding structures [

22]. However, because onboard devices must be installed on each bogie or car, their research, installation, and maintenance costs across an entire HSR network can be high, whereas risk is typically elevated at specific critical sections (e.g., bridges, tunnels, sharp curves, and segments exposed to wind, flooding, or seismic disturbances) where targeted trackside deployment is more practical [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Therefore, trackside solutions that can be selectively deployed at critical sections are attractive for practical risk reduction.

In this regard, structural guiding systems installed along the track—collectively referred to as Derailment Containment Provisions (DCPs)—have been recognized as a promising approach because they can be implemented locally at high-risk sections (e.g., bridges, tunnels, sharp curves, and zones prone to strong winds or flooding). Prior studies classify DCP geometries into three representative types: Type I (inside the track gauge, impacting at the wheel), Type II (outside the track gauge, still impacting at the wheel), and Type III (outside the track gauge, impacting at the axle or bogie) (see

Figure 1) [

30,

31]. Type I DCPs are typically placed within the gauge and function similarly to guard rails [

32,

33,

34], while Type III systems, often constructed from reinforced concrete (RC), have been adopted on railway bridges in Korea to prevent derailed trains from colliding with superstructures or falling off bridges at operating speeds exceeding 200 km/h [

35]. Despite this progress, many design decisions for such containment systems still rely heavily on numerical collision analyses and simplified load assumptions, and there remains a need for full-scale evidence and mechanism-based interpretation—especially for wall-type intrusion protection systems subjected to derailment impact.

Among structural options for impact containment, RC is widely regarded for its load-bearing capacity, energy absorption, controlled deformability, and durability under harsh environmental exposure [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Beyond geometry and reinforcement detailing, recent research has increasingly explored material-based strengthening measures to improve impact resistance and, importantly, to control fragment projection. In this context, polyurea has gained attention as an elastomeric coating capable of enhancing both impact resistance and fragment control in concrete and masonry structures. Polyurea is a segmented elastomer with a phase-separated “hard–soft” microstructure, providing a combination of strength, ductility, and pronounced strain-rate sensitivity. Under impulsive loading, its response may transition from “rubber-like” to “hard-skin-like,” with markedly increased modulus and yield stress while maintaining large critical strains—enabling efficient absorption and dissipation of impact energy [

40,

41,

42,

43].

Consistent with these mechanical characteristics, tests on polyurea-coated RC slabs and walls have shown reduced damage and residual displacement under close-in blast and localized impact loads, while substantially suppressing spalling and scabbing [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Polyurea coatings can act as a continuous “skin” to retain fragments and shift failure from brittle fragmentation toward membrane-like deformation, thereby reducing secondary injury risk from flying debris [

43,

44]. Review studies further identify polyurea as one of the most promising coating materials for blast resistance, impact resistance, and fragment control due to its strain-rate-sensitive behavior, large deformability without brittle fracture, strong adhesion to concrete/steel, and rapid spray application to existing structures [

40,

42,

43].

Nevertheless, most available evidence remains focused on close-in blast and localized impact acting on slabs, walls, or metal plates. By contrast, derailment-induced impact against intrusion protection walls involves a different loading mechanism characterized by large-mass–high-velocity interaction, potentially longer contact duration, and stringent requirements to control concrete debris to protect adjacent structures, vehicles, and passengers. Related derailment-impact research on adjacent infrastructure (e.g., tunnel lining collisions) also indicates intense short-duration contact with multi-peak load characteristics and damage governed by tensile cracking away from the direct impact region, emphasizing that derailment can impose severe and spatially distributed demands on nearby RC components [

29]. These differences motivate the need to evaluate polyurea in a derailment-relevant wall impact scenario and to establish full-scale behavioral data that can support performance assessment and design optimization.

Within this context, under a national research project on “Developing technologies to reduce risks and damage caused by derailment/intrusion accidents of trains,” the authors’ group selected polyurea as a protective coating for an RC intrusion protection system in the form of an inverted T-shaped wall. The coating can be spray-applied directly onto concrete surfaces to form a continuous skin on the impact face, anchored into the existing bridge deck. This skin is expected to contribute to membrane stress sharing and to retain concrete fragments when the wall cracks and fractures under impact. Based on the normal-energy equivalence adopted in this study, a full-scale collision test was conducted in which a 17.68-ton container wagon impacted the wall head-on at a speed of 34.59 km/h, corresponding to the impact energy of a 68-ton KTX car derailing and striking the wall at 300 km/h with an impact angle of 3°. Here, the equivalence is established on the basis of the kinetic energy associated with the effective impact component of velocity and the derailment posture assumed in the validated derailment scenario (details provided in in

Section 2.2). In parallel, a detailed numerical model of the wall–foundation–anchor system was developed and calibrated using experimental measurements (displacements, rotations, and impact forces) to support performance assessment and structural optimization.

Building on previous research and the identified knowledge gaps, this paper pursues three main objectives:

(i) To present the full-scale collision test program on polyurea-coated RC intrusion protection walls under conditions equivalent to high-speed train derailment;

(ii) To analyze the global and local wall response under impact loading, including displacements, rotations, impact forces, failure modes, and the capability of the polyurea coating to limit the dispersion of concrete fragments;

(iii) To discuss design implications regarding the geometry and detailing of intrusion protection walls, based on the observed failure mechanisms and the role of the polyurea coating in the full-scale tests.

2. Experimental Program

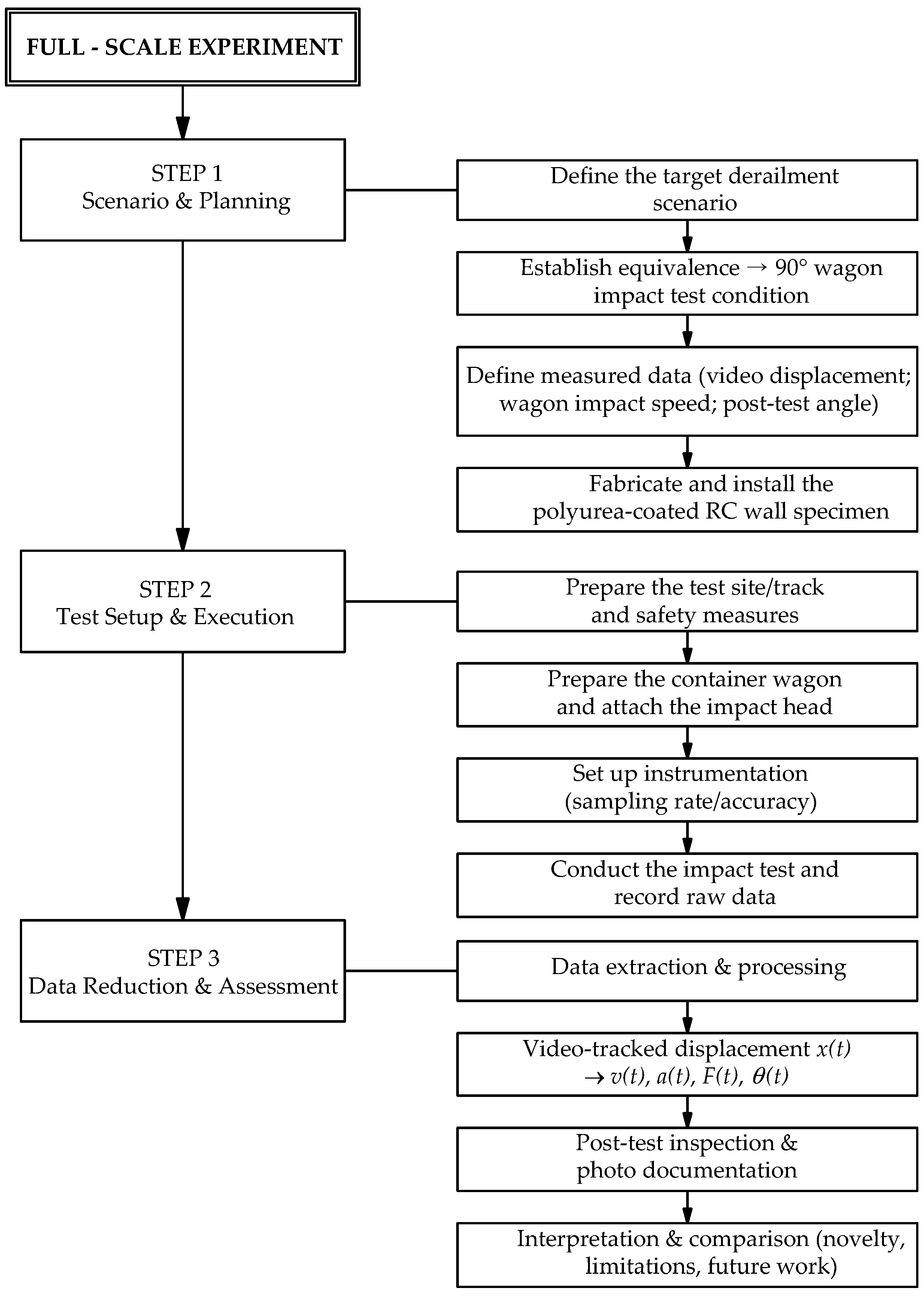

Figure 2 summarizes the overall workflow of the full-scale impact test and the data-reduction procedure. The detailed test setup/instrumentation and the adopted data processing are presented in

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3 and

Section 3.

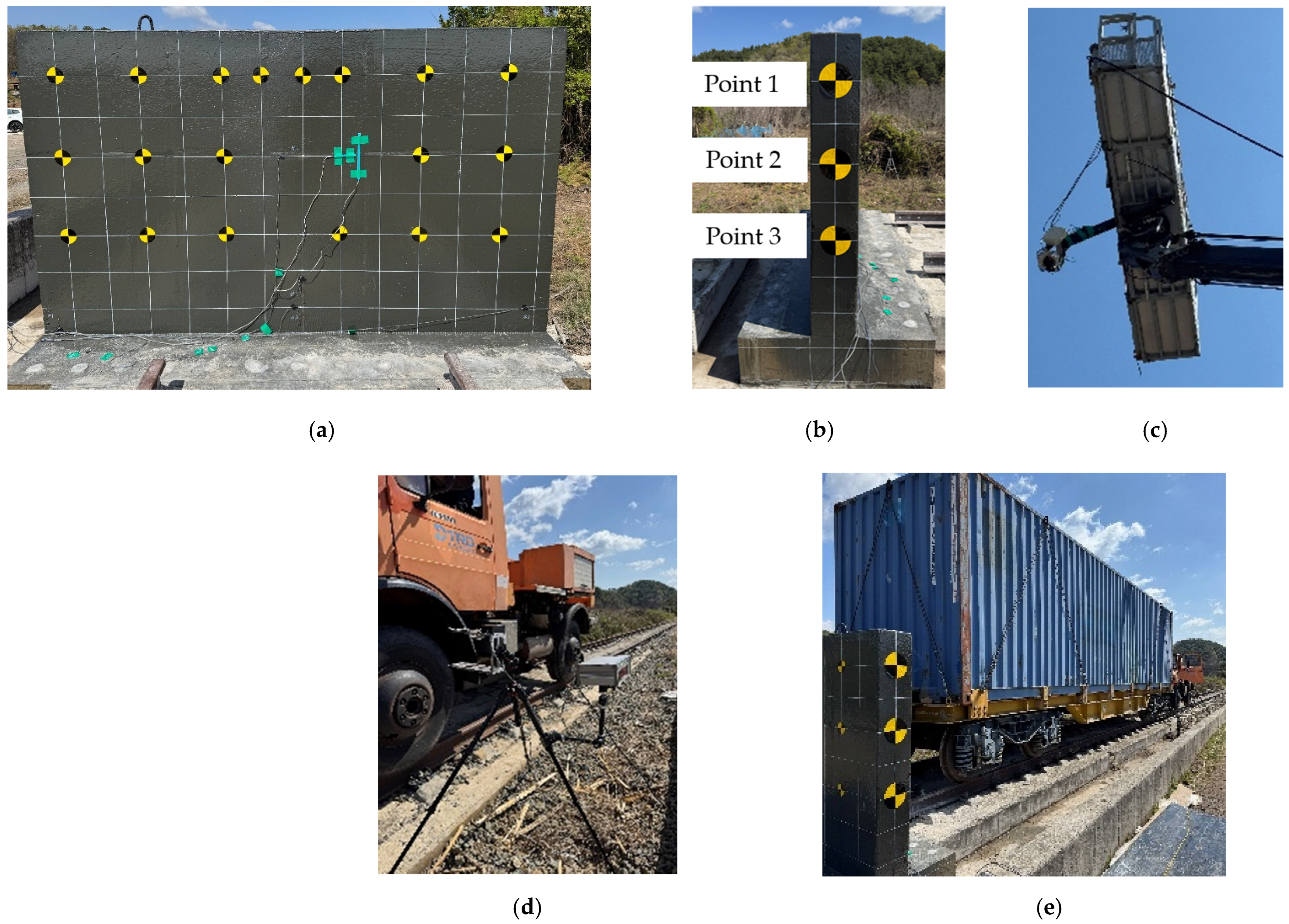

2.1. Intrusion Wall Specimen

The intrusion protection wall was constructed as an inverted T-shaped reinforced concrete (RC) wall, placed on the RC slab of the test site and rigidly anchored to the slab to ensure transfer of impact forces and to limit sliding and overturning under large lateral loads. The concrete used had a specified compressive strength of f′c = 30 MPa, and the reinforcing steel had a nominal yield strength of fy = 400 MPa.

The wall specimen had an overall length of approximately 3.3 m. The cross-section consisted of a vertical wall stem 300 mm thick and a footing slab 1350 mm wide. The height of the wall stem from the top of the footing to the top of the wall was 1950 mm, while the total height from the bottom of the footing to the top of the wall was 2300 mm; the footing thickness was 350 mm.

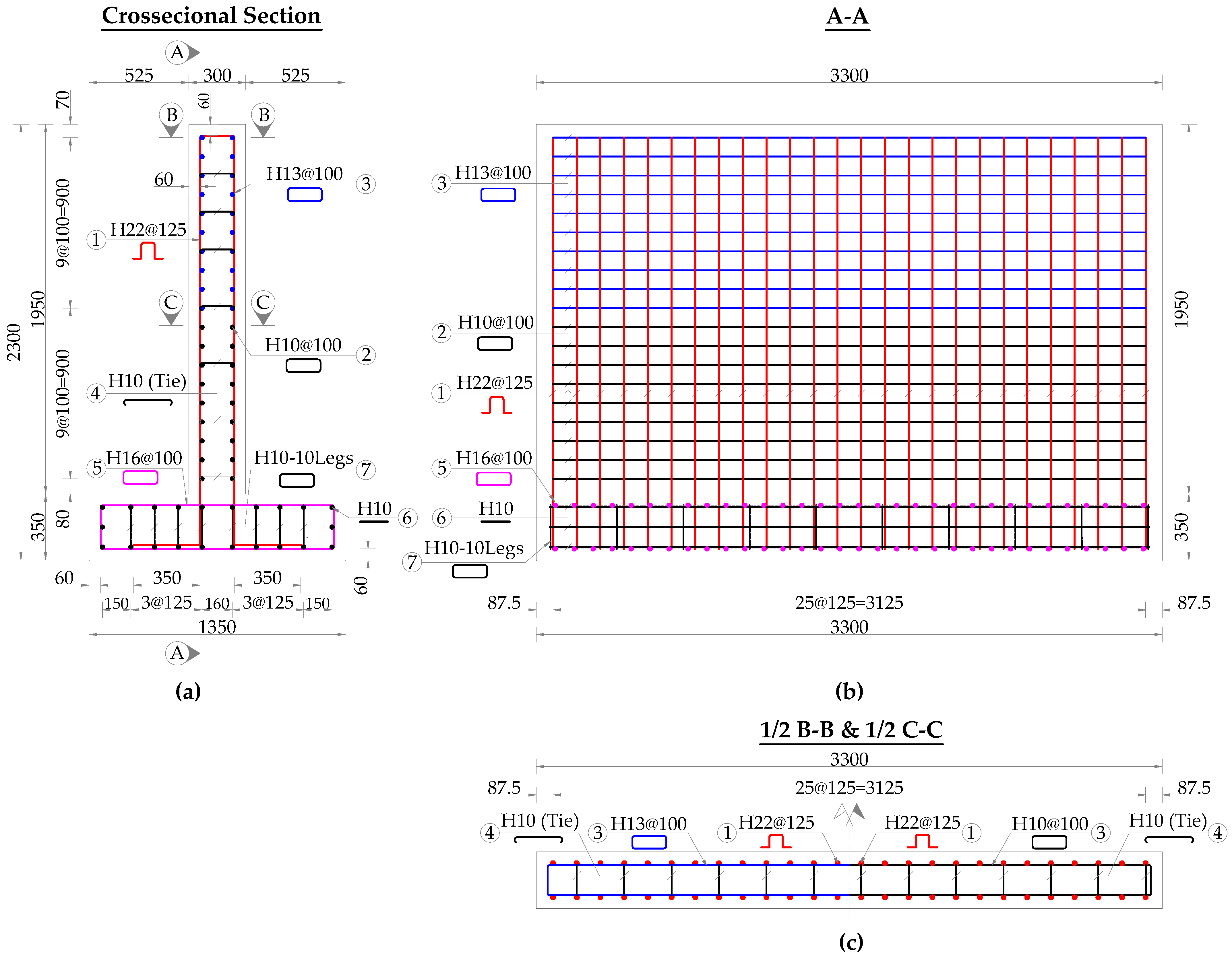

Figure 3 illustrates the reinforcement details of the wall specimen. In this figure, the H22 and H16 bars are the primary reinforcement for the wall stem and the footing, respectively, and they are arranged along the wall length at spacings of 125 mm and 100 mm. The H10 and H13 bars are provided mainly as ties (stirrups) and assembly/spacer bars to maintain bar spacing, provide bracing where necessary, and form the reinforcement framework of the protective wall. The number following “H” denotes the nominal bar diameter in millimeters.

A Polyurea layer was sprayed over the entire impact face of the wall and continuously across the junction between the wall stem and the footing, in order to prevent concrete debonding, limit fragment projection and increase the ductility of the system under high-velocity impact. The nominal thickness of the coating was approximately 5 mm, following the configuration adopted in the reference experimental program.

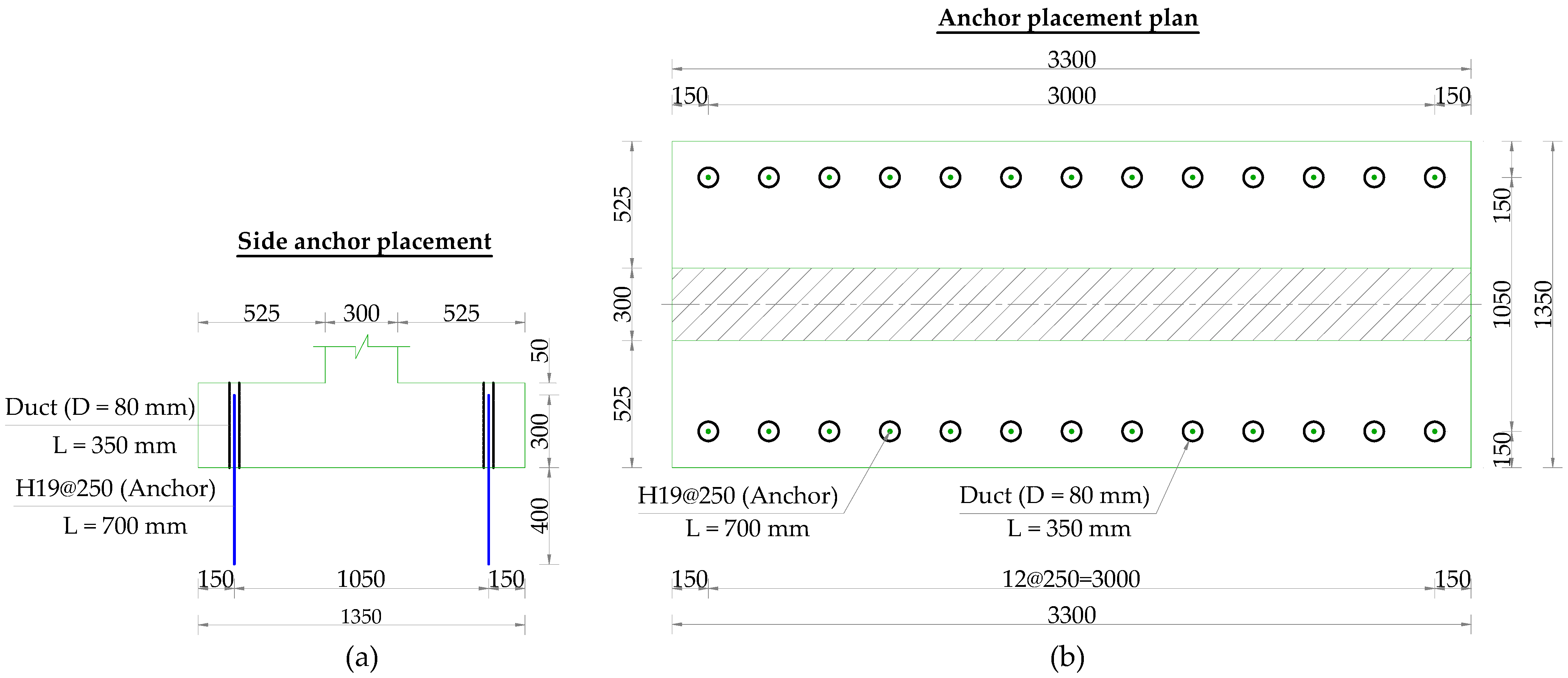

The wall–footing unit was anchored to the existing RC slab at the test site to prevent overturning and sliding under lateral impact. Anchorage was provided by post-installed Ø19 mm deformed reinforcing-bar anchors (H19; nominal yield strength

fy = 400 MPa) installed with an injectable adhesive mortar system (HIT-HY 200-R V3, Hilti, Schaan, Liechtenstein) at an embedment depth of 400 mm. The anchors were arranged at 250 mm spacing in two longitudinal rows along the footing; the spacing between the two rows was 1050 mm, leaving 150 mm cantilever portions at the front and rear edges. In addition, ducts with a diameter of 80 mm (length 350 mm) were provided for the anchorage detail and filled with non-shrink grout with

f′c = 30 MPa to secure the footing and ensure force transfer. The anchor arrangement and duct details are shown in

Figure 4.

2.2. Experimental Setup and Impact Scenario

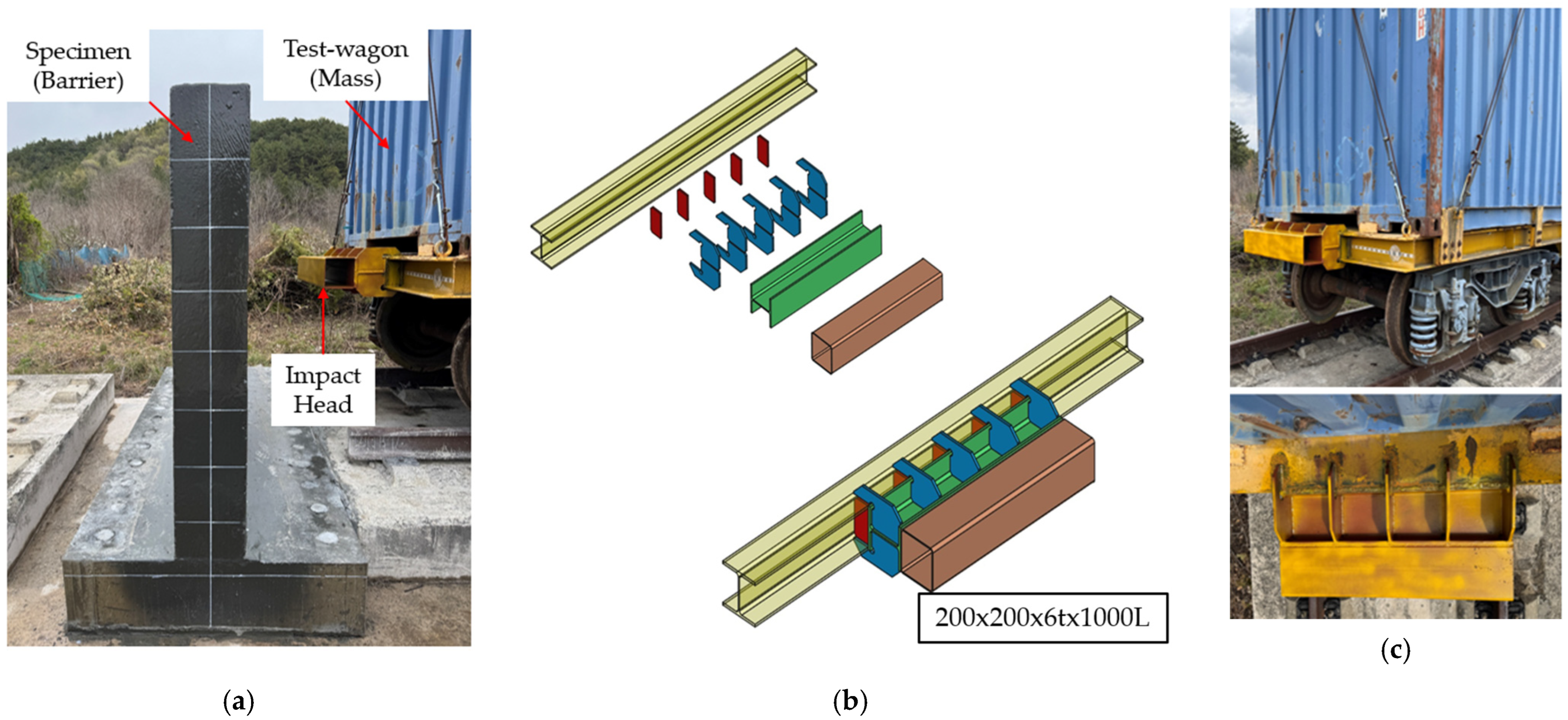

The full-scale impact test was conducted at an on-track railway test site, with a 120 m long test track comprising an acceleration section, an impact guidance section and the intrusion protection wall zone. The wall specimen was installed at the end of the test track (impact zone) and fixed to the existing reinforced concrete foundation using post-installed anchors.

The impacting container wagon used in the test had a mass of m = 17.68 t. The container wagon was towed by a Unimog towing vehicle and guided by a derailment-guidance device to achieve an approximately normal (90°) impact against the wall, representing the head-on equivalent test condition.

At the front end of the container wagon, a steel tube impact head was rigidly attached to the container wagon frame through a steel load-transfer assembly so that the impact load would be concentrated on the target region of the wall. The impact head was designed not to fail, serving only to transfer the impact energy into the wall.

The target impact speed for the full-scale test was determined using a normal-energy equivalence between the adopted 90° head-on container wagon impact and a representative high-speed derailment impact scenario. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the derailment case is idealized as an oblique collision with an impact angle

θ defined with respect to the wall surface. The post-derailment impact/heading angle is not a single fixed value and depends on the track geometry and the wall offset. In the intrusion-barrier design study by Moyer et al. [

49], small initial derailment angles on the order of a few degrees (approximately 1.1°–5.7°) were suggested depending on the offset distance. Based on this prior work,

θ = 3° was selected here as a representative design value within the reported range to define the normal kinetic-energy component used in the equivalence. The impact demand on the wall is assumed to be governed primarily by the normal component of the container wagon motion,

Vn (

Vn =

Vsin

θ), while the tangential component mainly contributes to sliding along the wall and is therefore neglected in the present equivalence. Accordingly, the effective normal impact energy is expressed as

where

M = 68 t is the mass of the train car and

V = 300 km/h is the assumed operating speed of the KTX train in the aforementioned derailment studies [

50,

51].

Applying the same impact energy to the container wagon with mass

m =17.68 t leads to the target speed

To compensate for losses due to friction, control errors and uncertainties under field conditions, a target speed band of 31–35 km/h was selected for the test. The actual speed measured at the instant of impact was 34.59 km/h, which lies within the target range and satisfies the requirements of energy and impact trajectory equivalence for the design scenario.

In addition to the impact zone, the measurement system included a photoelectric speed measurement system, accelerometers, high-speed cameras, displacement markers attached to the wall surface, protective shields and a safety zone for observers and instrumentation.

Figure 6 shows the overall layout of the intrusion protection wall, the container wagon and the impact head structure mounted on the container wagon.

2.3. Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

The instrumentation focused on capturing the wall kinematics and impact speed during the full-scale test. A single high-speed camera was installed at the side of the wall, and all displacement tracking was performed using the side-view recordings. The primary recorded data included high-speed camera videos for image-based displacement tracking, a photoelectric sensor-based speed measurement system for impact speed (two sensor gates consisting of four photo sensors, spaced 100 mm apart), and post-test measurements/photos for residual rotation and damage documentation. The high-speed camera recording was triggered by a pressure-activated sensor at the moment of impact. The trigger sensor was configured to record for a total duration of 3 s, including 0.5 s before impact and 2.5 s after impact, and was also used for time synchronization of the measured responses.

- (1)

Measurement of displacement and rotation

High-speed camera target marks were attached to the wall surface as stickers used as fixed pixel reference points for displacement tracking. The lateral displacement of the wall was obtained from the side-view high-speed camera recordings (recording frame rate: 1000 fps) using an image-based point-tracking technique. Three target points on the wall edge, denoted Point 1, Point 2, and Point 3, were selected as shown in

Figure 7b to represent the wall top, mid-height, and base. The recorded data consisted of high-speed camera video files (AVI format), from which displacement histories were derived using image-based displacement tracking. The tracked pixel coordinates were converted into physical displacements using a pixel-to-length scaling factor. For subsequent data reduction and presentation, the tracked displacement histories were exported/down-sampled to a sampling interval of Δ

t = 0.01 s (100 Hz).

The overall rotation of the wall after impact was measured using a digital angle meter. The device was placed successively on the wall surface and on the footing slab to determine the deviation from the initial vertical alignment; the difference between the measured angles was used to assess the wall rotation and its overturning risk.

For impact-force evaluation, the displacement history x(t) obtained from video tracking at the contact region between the container wagon and the wall (based on the wall target markers) was numerically differentiated to obtain velocity v(t) and acceleration a(t). To reduce noise, the acceleration signal was filtered using a moving average with a 150 ms window (15 samples at 100 Hz). Assuming negligible slip/separation during the main impact phase, the contact-point acceleration was taken as an approximation of the container wagon deceleration, and an equivalent impact force history was estimated as F(t) = ma(t), where m is the container wagon mass.

- (2)

Damage monitoring and field observations

Target markers were attached to the wall surface as fixed pixel reference points for image-based displacement tracking in the high-speed camera analysis. The high-speed footage was used primarily for kinematic measurements; the frames were additionally reviewed to qualitatively identify major visible damage events in the impact region (e.g., local spalling or coating tearing/debonding, if observed). After the test, the wall was visually inspected and photographed to document the observed damage, such as surface cracking, local spalling, delamination/debonding, and localized failure near the impact zone.

The recorded time-history data were post-processed to obtain displacement, velocity, acceleration, and the corresponding impact-force history.

3. Test Results and Discussion

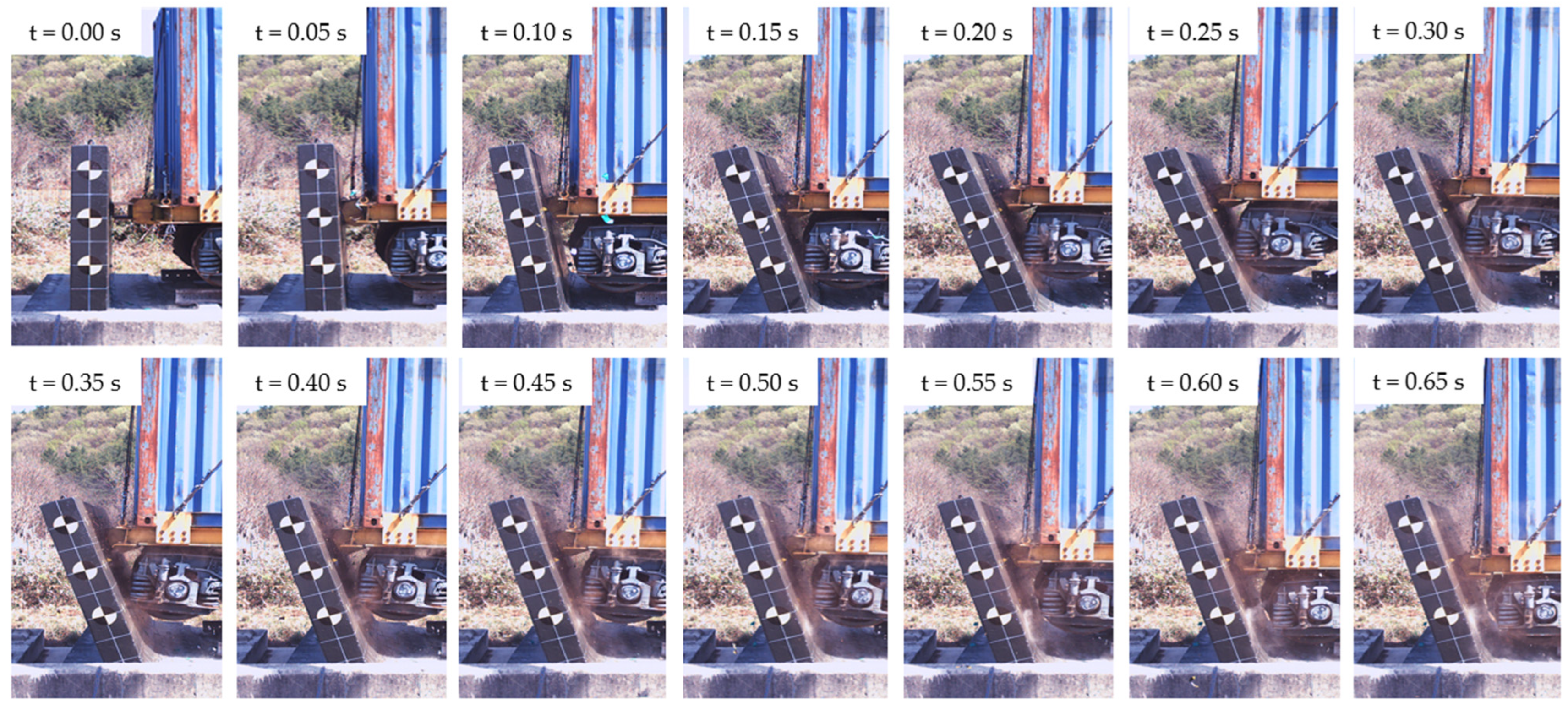

3.1. Global Behavior and Intrusion-Prevention Performance

The polyurea-coated RC intrusion-protection wall was impacted by the container wagon (empty container wagon) with a mass of 17.68 t at a measured impact speed of 34.59 km/h. The sequential high-speed images in

Figure 8 show that the wall–footing system responded predominantly through global rotation. After the initial contact, the response rapidly transitioned into rocking, with pronounced rotation observed at approximately

t ≈ 0.10 s (

Figure 8). Rocking continued during the main contact phase while the container wagon remained in contact with the wall face and decelerated progressively.

From the intrusion-prevention standpoint, the container wagon was retained in front of the wall throughout the recorded event and did not climb over the wall crest (

Figure 8). The high-speed footage did not show noticeable sliding of the footing on the supporting RC slab or obvious uplift at the footing edges, which is consistent with a rocking-dominated response under the tested condition. Based on the high-speed observation and post-test visual inspection, no obvious brittle failure (e.g., a sudden loss of load-carrying capacity accompanied by extensive fragmentation) was identified during the main impact phase. Overall, the tested wall system successfully prevented intrusion into the space behind the wall under the representative full-scale impact scenario.

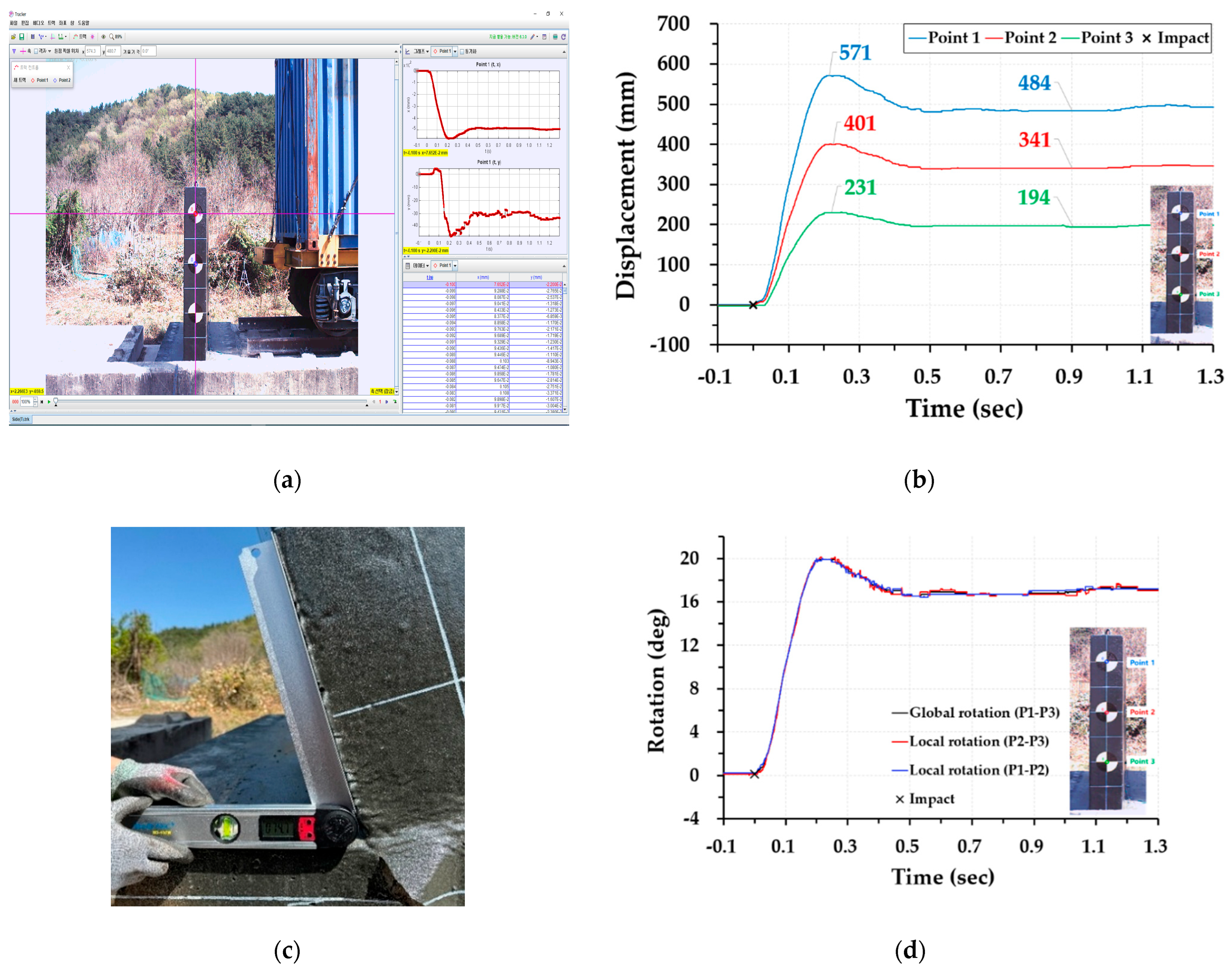

3.2. Wall Displacement and Rotation Time Histories

As described in

Section 2.3, the wall kinematics during impact were obtained from the side-view high-speed camera recordings (1000 fps) using an image-based point-tracking method applied to target markers along the wall height. The tracking provided synchronized lateral displacement histories at three locations: the wall top (Point 1), an intermediate position (Point 2), and near the wall base (Point 3). For data reduction and consistent presentation, the tracked displacement histories were converted to physical units using a pixel-to-length scaling factor and then exported at a sampling interval of Δ

t = 0.01 s (100 Hz).

Figure 9b summarizes the measured lateral displacement histories. At all three points, the displacement increases rapidly immediately after impact, reaches a single peak, and then decreases slightly to a nearly constant residual value, with no evident long-lasting free vibration after the main contact phase. This “single-peak + residual” shape indicates that the response is dominated by a brief impact-driven deflection followed by limited elastic recovery, rather than sustained oscillation. Quantitatively, the peak and stabilized displacements were approximately 571/484 mm at Point 1, 401/341 mm at Point 2, and 231/194 mm at Point 3.

Two features of these displacement histories are noteworthy from a mechanism and design perspective. First, the displacement amplitude decreases systematically from the top (Point 1) to the base (Point 3), which is consistent with a rocking-dominated global motion about the rear edge of the footing. Second, the decrease from peak to stabilized displacement is about 15–16% of the peak value at all points, implying limited elastic rebound and a substantial residual deformation component (≈84–85%). This residual component is consistent with permanent rotation concentrated near the wall–footing interface, which is also where cracking and localized footing damage were observed after the test (see

Section 3.4). Together, these observations indicate that the tested system dissipated a large portion of the impact demand through a predominantly global rocking response accompanied by localized inelasticity near the base, rather than through extensive distributed flexural deformation along the wall stem.

To further quantify the kinematics in a way that is directly interpretable for intrusion-prevention performance, the synchronized displacement histories were converted into rotation (inclination) histories. The apparent inclination relative to the vertical,

θij(

t), inferred from a point pair

i-

j was computed as:

where

xi(

t) and

xj(

t) are the measured lateral displacements at Points

i and

j, respectively, and hij is the initial vertical spacing between the two tracking points obtained from the target layout (assumed constant for the kinematic conversion).

Figure 9d shows the resulting rotation histories inferred from three point pairs: the global rotation

θ13(t) (P1–P3) and the local rotations

θ12(t) (P1–P2) and

θ23(t) (P2–P3).

Notably, the three rotation histories almost overlap over the entire event. This overlap serves as an internal consistency check for the image-based kinematic conversion and provides direct experimental evidence that the wall stem behaved close to a rigid body with limited flexural deformation along the height. In practical terms, the result supports interpreting the dominant deformation demand as rotation concentrated near the wall–footing interface (i.e., rocking) rather than distributed curvature, which is important for relating the observed response to simplified mechanical models and for identifying the critical detailing region for impact resistance.

Based on

Figure 9d, the maximum wall inclination relative to the vertical was about 19.9°, followed by an elastic recovery of about 2.9°, resulting in a residual inclination of approximately 17°. Post-test measurements using a digital angle meter (

Figure 9c) provide an independent verification of the residual inclination: measurements at three locations along the wall length (left edge, mid-length, and right edge) yielded 16.2°, 14.7°, and 15.3°, respectively (average ≈ 15.4°). The small difference (≈1–2°) is attributed to differences between the measurement approaches (image-based rotation inferred from tracked points versus post-test multi-location angle readings) and minor non-uniform rotation/flexure along the wall length. Overall, both approaches indicate a comparable residual wall inclination on the order of 15–17°, confirming that the tested wall maintained its integrity while accommodating the impact primarily through global rocking.

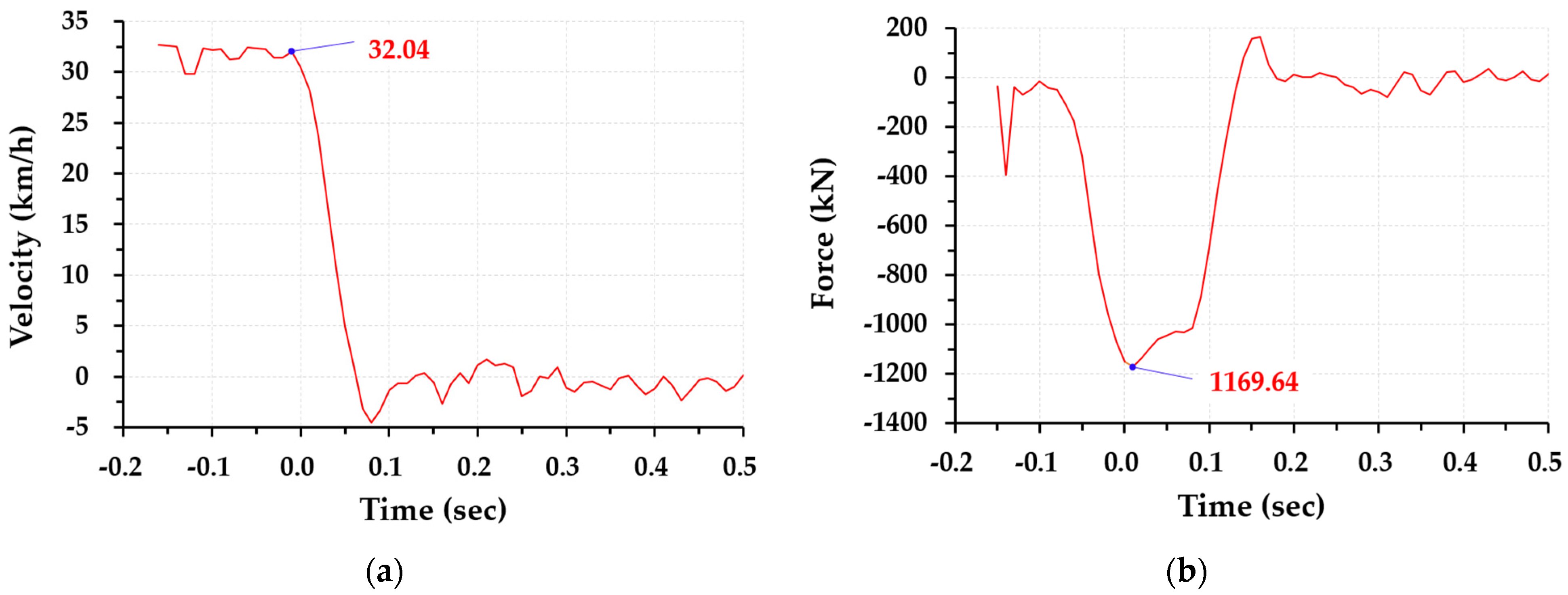

3.3. Container Wagon Kinematics and Estimated Impact Force

The container wagon velocity and the equivalent (estimated) impact force reported in

Figure 10 were derived from the image-based kinematics at the container wagon–wall contact region. The tracked displacement time series

x(

t) was sampled with a time step of Δ

t = 0.01 s and differentiated using centered finite differences to obtain the velocity and acceleration, respectively, as follows (Equations (4) and (5)):

Because numerical differentiation amplifies tracking noise, the acceleration time series was smoothed using a moving-average window of 150 ms (15 samples at 100 Hz). The equivalent impact force was then estimated from the smoothed acceleration using Equation (6), with m = 17.68 t. This force should be interpreted as an indicative impact-pulse estimate derived from post-processed kinematic signals, rather than a direct force measurement from dedicated load instrumentation.

As shown in

Figure 10a, the container wagon velocity remains approximately constant before contact (about 32 km/h in the video-derived signal) and drops rapidly during the primary impact phase, approaching near zero within approximately 0.07–0.10 s.

Figure 10b shows the corresponding estimated impact-force response: the force increases sharply after initial contact and reaches a peak magnitude of approximately 1.17 MN, followed by a smooth decay toward values fluctuating around zero. The post-impact small oscillations mainly reflect residual vibration and signal noise after the main force-transfer phase. (For reference, the independently measured impact speed from the photoelectric sensor at the instant of impact was 34.59 km/h, reported in

Section 2.2; minor differences from the video-derived pre-impact level are attributable to the tracking-based estimation and time alignment).

3.4. Failure Mode and Footing-Dominated Damage Mechanism

Post-impact field observations show that damage was concentrated mainly at the wall–footing junction (

Figure 11a), where bending demand is highest and where rotation was concentrated during the event. The cracking pattern consisted primarily of nearly vertical flexural cracks on the wall surface, together with inclined tension cracks propagating from the footing edge into the wall stem, forming a fan-shaped diagonal cracking zone converging toward the wall–footing interface (

Figure 11b,c). On the rear side of the footing, localized spalling/detachment of cover concrete was observed in the region of intense rotation, consistent with the rocking response about the rear footing edge identified in the displacement and rotation analysis (

Section 3.2).

As shown in

Figure 11d, only localized debonding/tearing of the polyurea coating and slight concrete spalling occurred in the immediate vicinity of the load application region; no deep crushed crater or through-thickness shear band was formed in the impact zone. The upper part of the wall stem (mid-height to top) largely retained its monolithic geometry, and no severe local crushing in the impact area was recorded.

In the footing–anchor connection zone, no cone-type tensile breakout, anchor pull-out, or radial cracking around the anchor locations was observed. The wall–deck anchorage employed post-installed Ø19 mm deformed rebar anchors (H19; nominal yield strength

fy = 400 MPa) installed with an injectable adhesive mortar system (HIT-HY 200-R V3, Hilti) at an embedment depth of 400 mm (see

Section 2.1 and

Figure 4). Post-impact inspection confirmed that the anchor heads remained embedded within the footing block and that the surrounding concrete did not exhibit cone-shaped spalling, indicating that the footing–anchor system did not become the weak link of the structure. Overall, the damage pattern is consistent with a footing-dominated rocking mechanism, with plastic rotation and flexural–shear cracking localized at the wall base rather than sliding failure or anchorage failure, while maintaining overall stability and intrusion-prevention functionality after impact.

3.5. Effectiveness of a Polyurea Coating in Fragmentation and Local Damage Mitigation

In the present full-scale impact test, the hot-sprayed polyurea layer (nominal thickness ≈ 5 mm) was applied over the entire impact face and across the wall–footing junction. Post-impact inspection (

Figure 11d) showed only localized tearing/debonding of the coating in the immediate contact region, while the surrounding coating remained largely bonded. The observed damage pattern indicates that the polyurea mainly affected the local response at the impact face—retaining fractured concrete and limiting spalling/fragment release—whereas the global response was governed by the footing-dominated rocking mechanism discussed in

Section 3.4.

These observations are consistent with prior blast and impact studies reporting a membrane-like “skinning/catcher” mechanism of polyurea coatings: even when cracks form in the substrate, the coating bridges the cracked surface and restrains fragments from being propelled. In shock-tube blast tests on concrete tiles, uncoated specimens fragmented and ejected high-velocity debris, whereas polyurea-coated specimens showed a strong fragment-arrest effect, with mitigation improving as coating thickness increased (thin coatings already providing fragment restraint, and thicker layers delaying fragmentation to higher load levels). Similar findings were reported for contact-explosion tests on RC slabs protected by spray-applied polyurea, where the coated specimen exhibited a pronounced reduction in fragmentation relative to the unprotected specimen, achieving a “zero-fragmentation” protection effect on the back face under a large-equivalent contact blast [

45]. These studies also note that the coating may experience localized tearing and/or local delamination near highly loaded regions, which is consistent with the localized damage observed in

Figure 11d [

45].

Beyond fragment retention, published work highlights two practical parameters that strongly govern coating effectiveness: (i) bond quality/adhesion and (ii) coating thickness. Bond performance is repeatedly identified as critical; premature debonding reduces the ability of the coating to retain debris and to provide its intended mitigation effect. Accordingly, several experimental programs emphasize surface treatment and/or primer application to improve adhesion and reduce irregular delamination, particularly near edges and spray discontinuities. In addition, parametric and full-scale masonry-wall studies suggest that a polyurea thickness in showed a strong fragment-arrest effect the range of several millimeters is typically required to delay coating rupture under severe impulsive loads. For example, a minimum thickness of about 6 mm (with high tensile strength and large elongation capacity) has been recommended as a practical lower bound for blast retrofitting of masonry walls, while thicker layers (e.g., 10 mm) can substantially increase rupture limits. Although the present coating thickness (≈5 mm) is slightly below this masonry-oriented recommendation, the current full-scale impact observations still demonstrate effective fragment restraint and limited impact-face spalling, indicating that thin-to-moderate polyurea layers can provide substantial benefits for fragmentation control in RC wall applications.

Regarding “energy dissipation,” polyurea is well known to exhibit rate- and frequency-dependent viscoelastic loss, and dynamic mechanical analyses on blast-mitigation polyurea formulations report favorable loss factors over a wide frequency range. In principle, the absorbed energy of the wall and the container wagon can be defined as the contact work, E(t) = ∫Fdx. However, this study does not report a time history of absorbed energy because the available video-tracked kinematics are not sufficiently robust for repeated differentiation/integration without amplifying noise, and an energy curve derived from such processing would carry non-negligible uncertainty. Therefore, the coating contribution is assessed here using damage-based indicators (fragment retention, reduced spalling/crater formation, and localized coating tearing patterns), supported by comparisons with prior coated/uncoated studies under blast and impact loading.

Overall, the results suggest that the primary benefit of the polyurea coating in the present wall specimen is fragmentation control and local damage moderation at the impact face, while the main deformation demand is accommodated by a stable, footing-dominated rocking response. This combined behavior—localized coating damage with retained substrate fragments and a global rocking mechanism—provides a structurally favorable and potentially more repairable post-impact damage state compared with brittle local crushing/shear-dominated failure patterns commonly reported for unprotected brittle wall systems.