Preparation of Red Mud-Electrolytic Manganese Residue Paste: Properties and Environmental Impact

Highlights

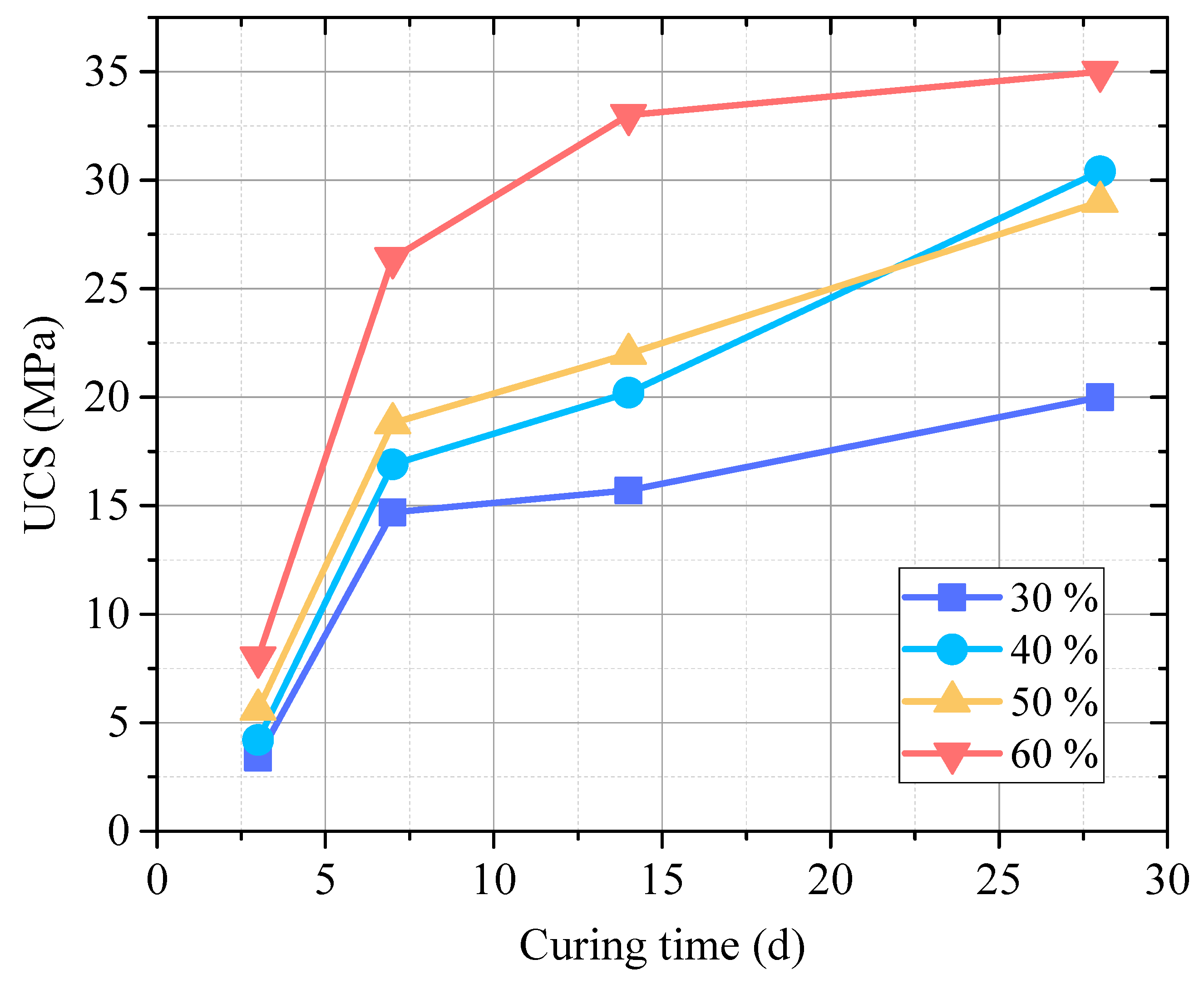

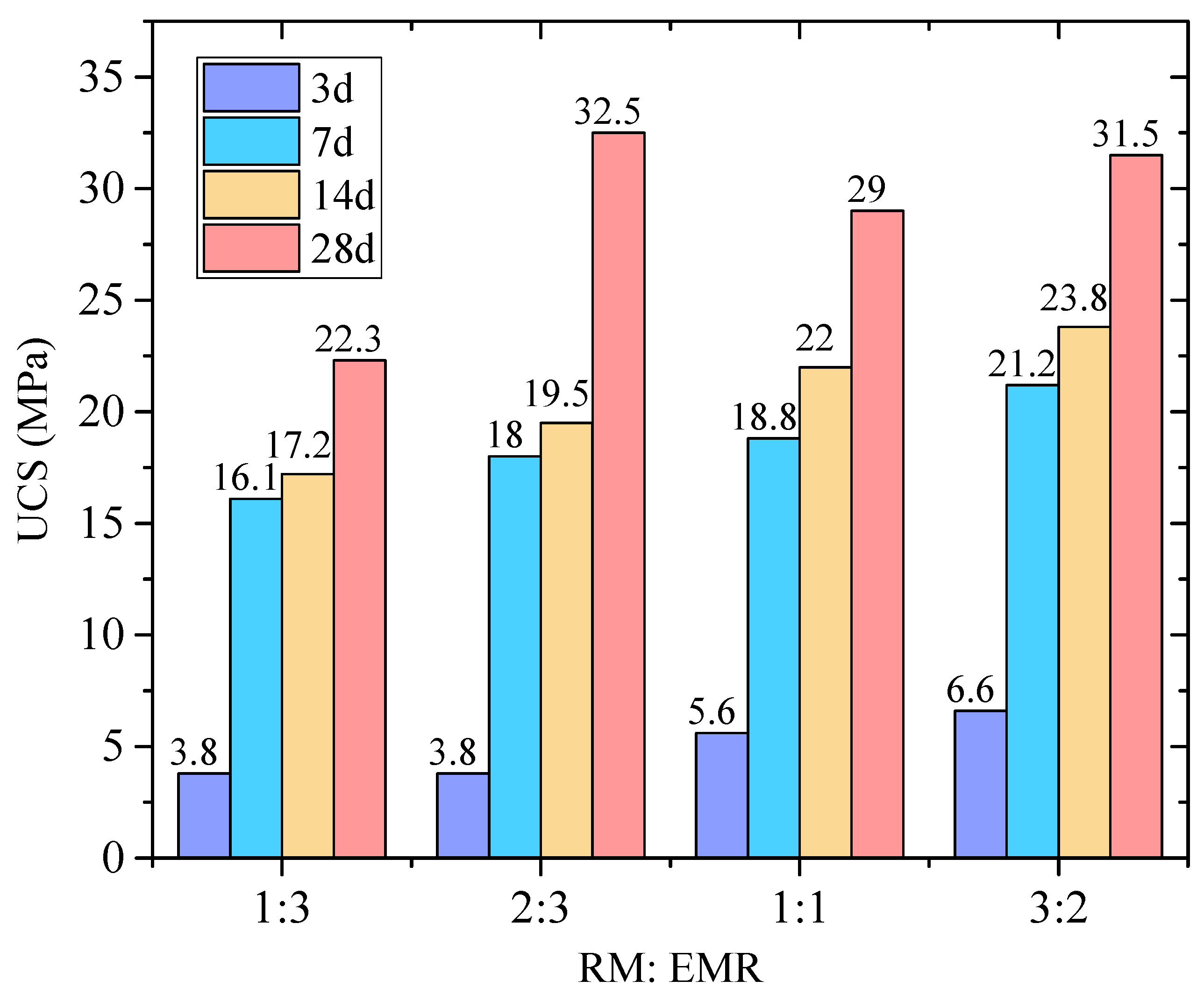

- When the RM-EMR mass ratio is 2:3 and the activator content reaches 60%, the optimal 28-day unconfined compressive strength reaches 35 MPa, and strength development follows a “rapid growth–gradual stabilization” pattern.

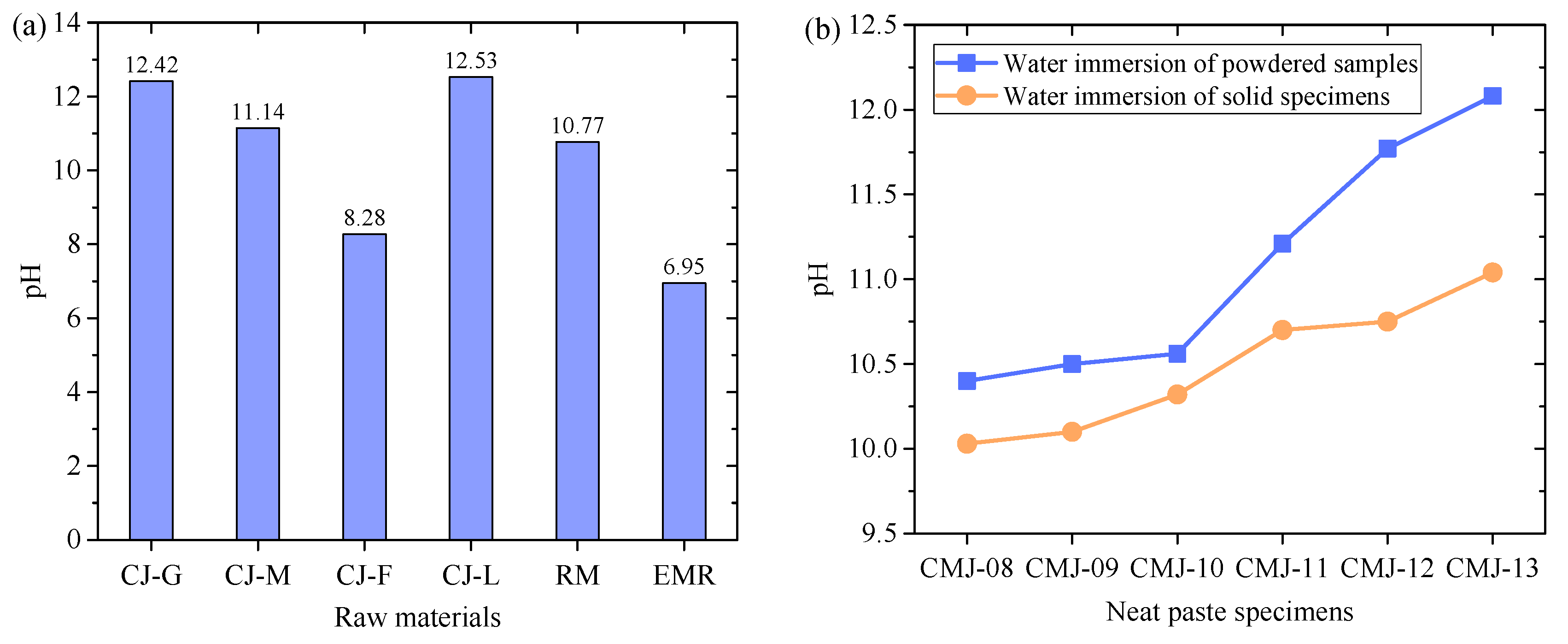

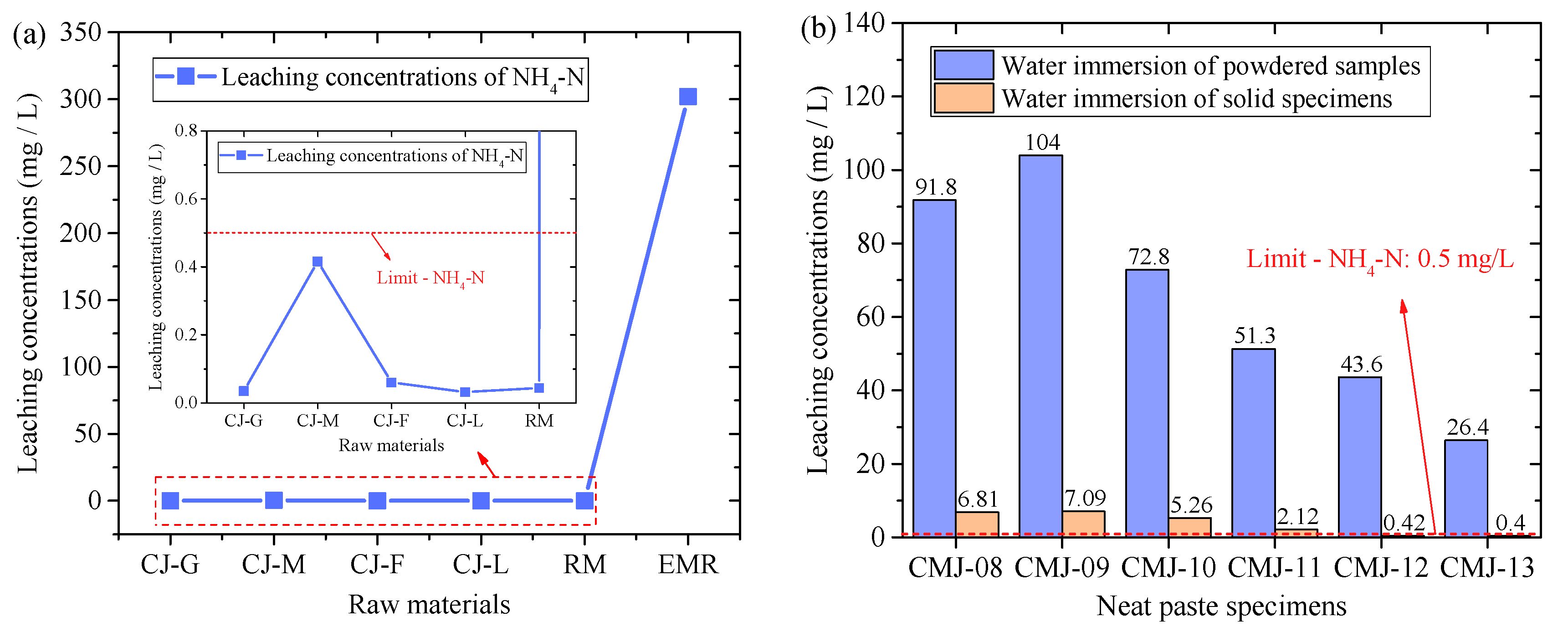

- EMR showed high NH4+-N leaching performance (302 mg/L), and under the alkaline conditions induced by the activator (pH > 11), NH4+ were converted to gaseous NH3, and more than 50% of the composite test block leaching values met the regulatory limits.

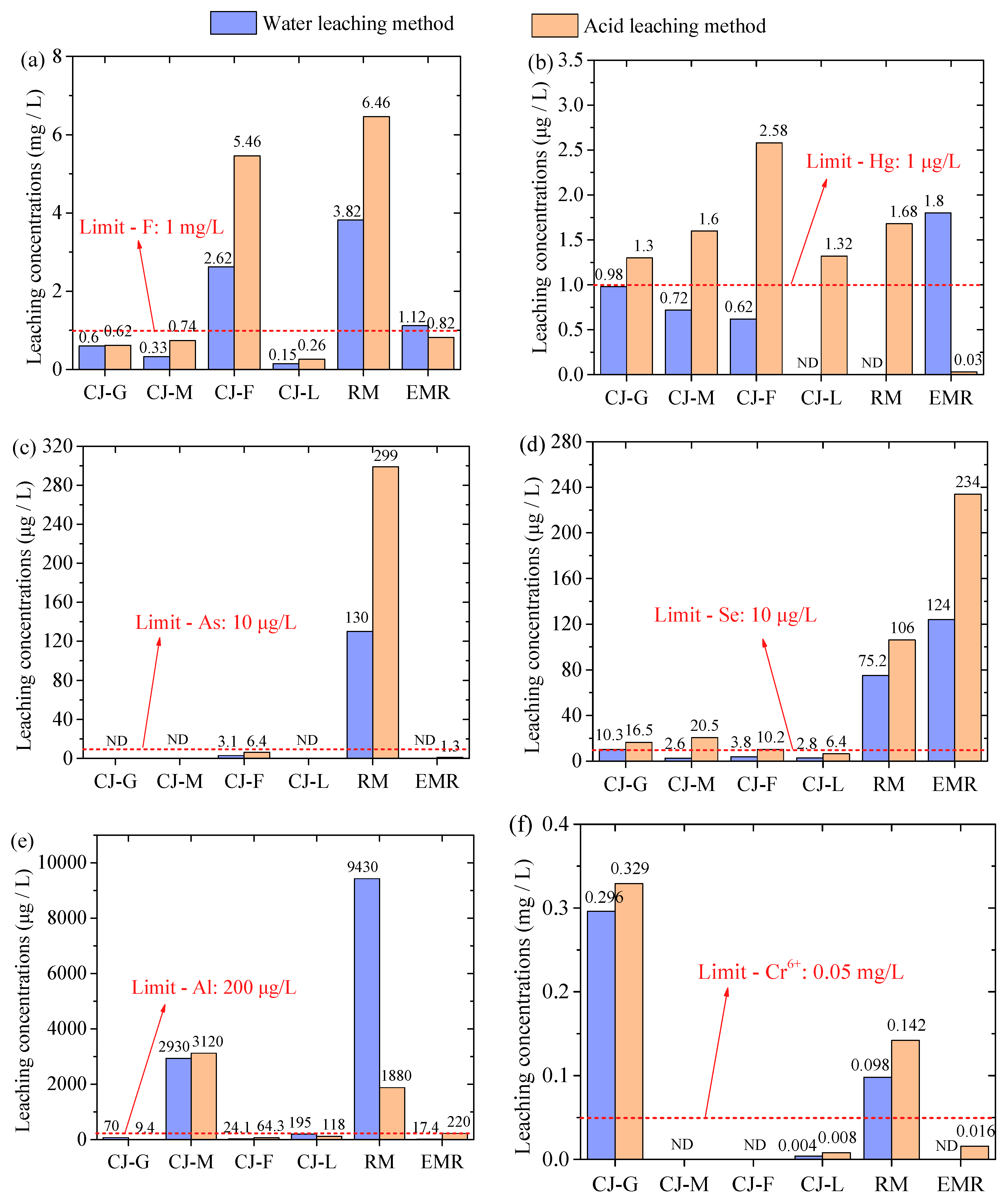

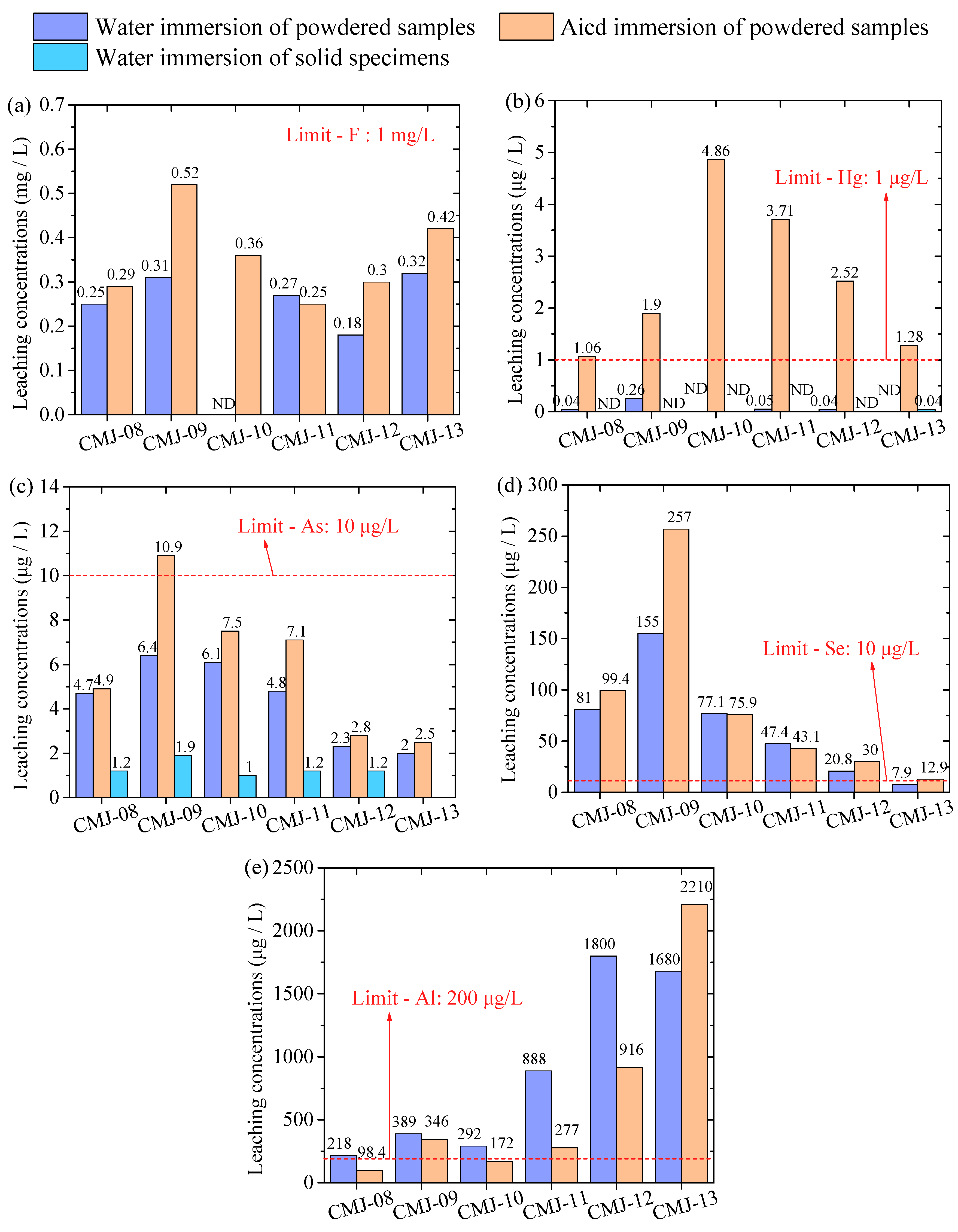

- The RM-EMR system can effectively fix Mn and Cd, while Al and Se show high leaching behavior, especially the extremely high leaching concentrations of Al under water immersion conditions.

- These findings indicate that proper raw material ratio and activator dosage control can synergistically improve early/long-term strength, supplying key design parameters for solid waste-based cementitious material engineering use.

- The results show alkalinity regulation has a dual function: it may raise pH but reduces ammonia pollution via chemical transformation, offering new insights for environmental safety control.

- The results demonstrated that RM-EMR is effective in immobilizing heavy metals, and elevated Al/Se leaching requires raw material pretreatment (e.g., removing soluble Al), thus providing guidance for process refinement.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

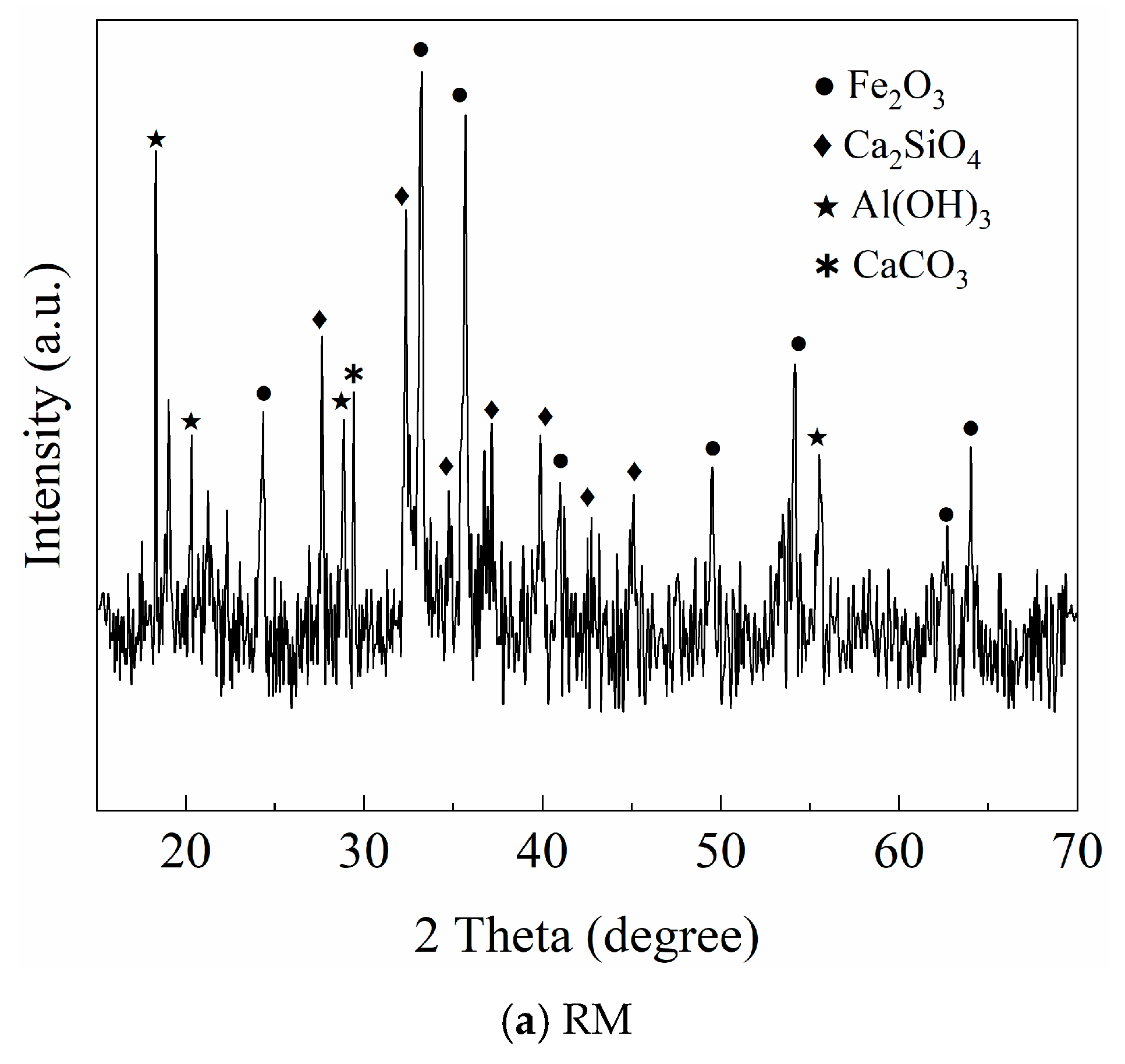

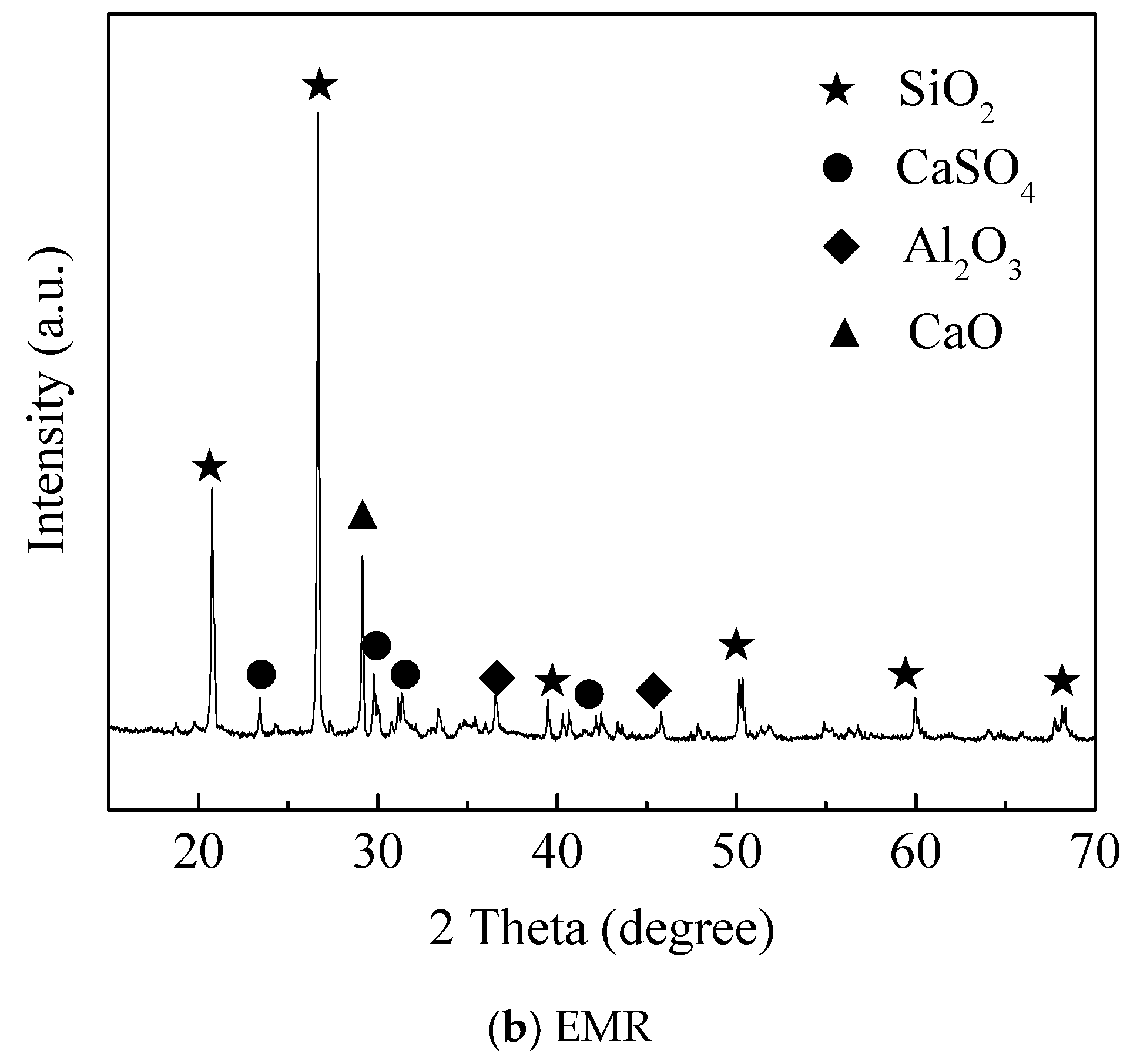

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportions

2.3. Specimen Preparation

2.4. Test Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Unconfined Compressive Strength

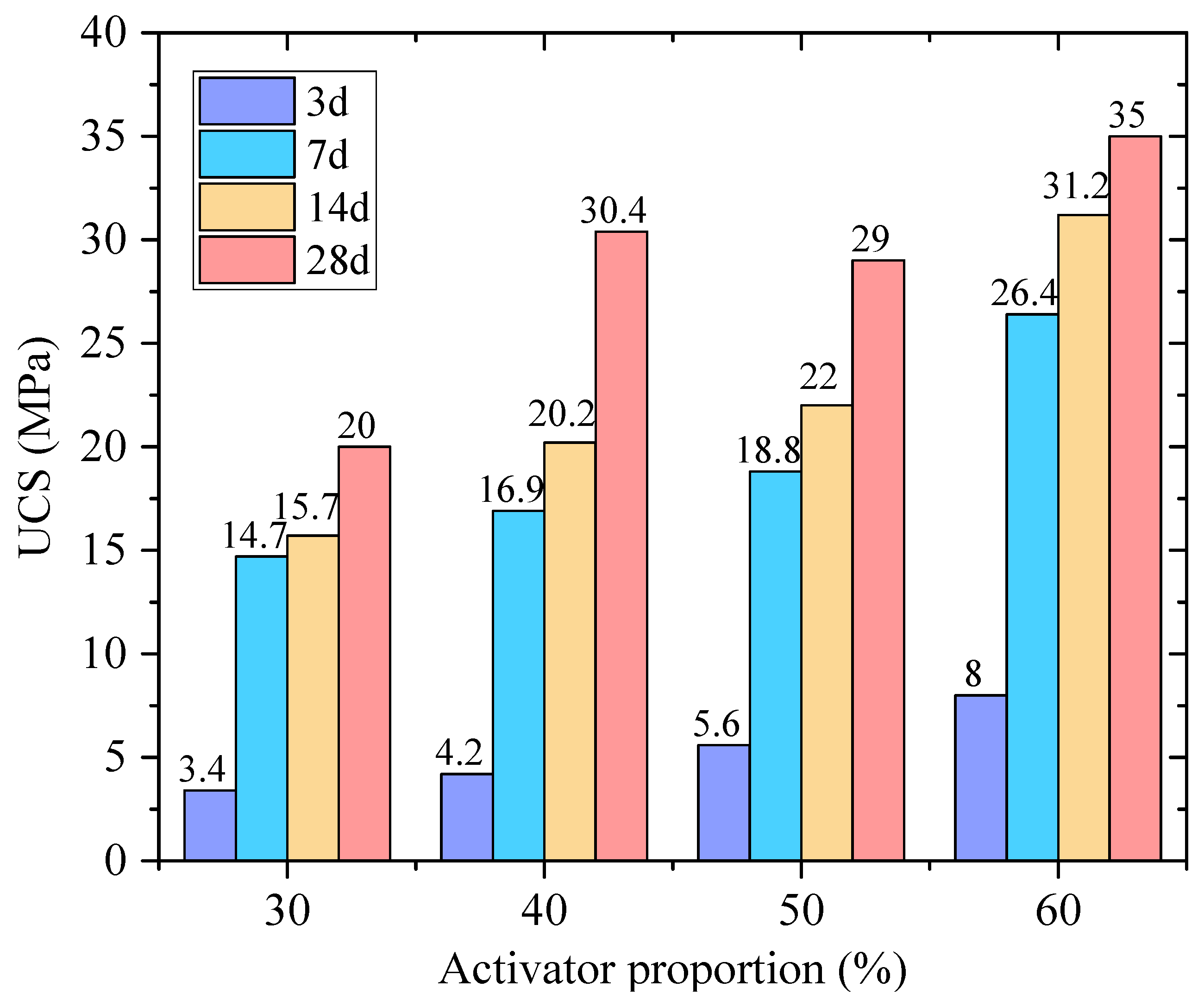

3.1.1. The Influence of Activator Proportion

3.1.2. The Influence of Curing Time

3.1.3. The Influence of RM to EMR Ratio

3.2. Environmental Impact

3.2.1. Leachate pH

3.2.2. NH4+-N Concentration

3.2.3. Leaching Toxicity

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Mix Proportion Optimization and Mechanical Properties

- (2)

- Alkaline Environment Regulation and Ammonia Nitrogen Removal Mechanism

- (3)

- Environmental Behavior of Heavy Metals and Harmful Elements

- (4)

- Limitations and future research directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RM | Red mud |

| EMR | Electrolytic manganese residue |

| UCS | Unconfined compressive strength |

| FA | Fly ash |

| AFt | Ettringite |

| CCUS | Carbon capture and sequestration |

| B-CSA | Belite-calcium sulfoaluminate cement |

| BYF | Belite-ye’elimite-ferrite |

| SS | Steel slag |

| C-A-S-H | Calcium silicate aluminate hydrate |

| C-S-H | Calcium silicate hydrate |

| LC3 | Limestone calcined clay cement |

| GGBS | Ground granulated blast furnace slag |

| REP | RM-EMR paste |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

References

- Wu, T.; Ng, S.T.; Chen, J. Deciphering the CO2 emissions and emission intensity of cement sector in China through decomposition analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 352, 131627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldsund, M.; Gardarsdottir, S.; De Lena, E.; Pérez-Calvo, J.-F.; Jamali, A.; Berstad, D.; Fu, C.; Romano, M.; Roussanaly, S.; Anantharaman, R.; et al. Comparison of Technologies for CO2 Capture from Cement Production—Part 1: Technical Evaluation. Energies 2019, 12, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Feng, Z.; Pu, S.; Zeng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, C.; Song, H.; Feng, X. Mechanical properties and environmental characteristics of the synergistic preparation of cementitious materials using electrolytic manganese residue, steel slag, and blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Toward sustainable green alumina production: A critical review on process discharge reduction from gibbsitic bauxite and large-scale applications of red mud. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, A.; Lin, C. Trends in research on characterization, treatment and valorization of hazardous red mud: A systematic review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshy, N.; Dondrob, K.; Hu, L.; Wen, Q.; Meegoda, J.N. Synthesis and characterization of geopolymers derived from coal gangue, fly ash and red mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 206, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, J.; Perušić, M.; Stopić, S.; Kostić, D.; Smiljanić, S.; Filipović, R.; Damjanović, V. A review of the red mud utilization possibilities. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Chem. 2024, 35, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Dhawan, N. Microwave acid baking of red mud for extraction of titanium and scandium values. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 204, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gou, H. Unfired bricks prepared with red mud and calcium sulfoaluminate cement: Properties and environmental impact. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wu, A.; Ruan, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, R. Effective reuse of red mud as supplementary material in cemented paste backfill: Durability and environmental impact. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 328, 127002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, I.M.; Aliaghazadeh, M.; Charkhtab, S.; Fathollahpour, A. Environmental impacts and mechanical properties of lightweight concrete containing bauxite residue (red mud). J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2683–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsali, S.; Yildirim, F. Environmental impact assessment of red mud utilization in concrete production: A life cycle assessment study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 12219–12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, K.; Chang, J. Synthesis process-based mechanical property optimization of alkali-activated materials from red mud: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z. Application of red mud in carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J. Removal, conversion and utilization technologies of alkali components in bayer red mud. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Hydration mechanism and leaching behavior of bauxite-calcination-method red mud-coal gangue based cementitious materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 314, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, P.; Hu, C.; Xia, H.; Liang, Z. Study on the Mechanical Properties and Hydration Behavior of Steel Slag-Red Mud-Electrolytic Manganese Residue Based Composite Mortar. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Synergistic utilization, critical mechanisms, and environmental suitability of bauxite residue (red mud) based multi-solid wastes cementitious materials and special concrete. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 361, 121255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Pu, S.; Cai, G.; Duan, W.; Song, H.; Zeng, C.; Yang, Y. Synergistic preparation of geopolymer using electrolytic manganese residue, coal slag and granulated blast furnace slag. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, B.; Zhao, H.; Lu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, Y. Synthesis of Electrolytic Manganese Slag-Solid Waste-Based Geopolymers: Compressive Strength and Mn Immobilization. Materials 2024, 17, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Li, R.; Nie, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q. Belite-calcium sulphoaluminate cement prepared by EMR and BS: Hydration characteristics and microstructure evolution behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 333, 127415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, D. Synergistic use of electrolytic manganese residue and barium slag to prepare belite- sulphoaluminate cement study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, D. Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis on preparation of belite-calcium sulphoaluminate cement using electrolytic manganese residue and barium slag by TGA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 95901–95916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Long, G.; Bai, M.; Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, J.L. A new perspective on Belite-ye’elimite-ferrite cement manufactured from electrolytic manganese residue: Production, properties, and environmental analysis. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 163, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, C.; Ning, P.; He, M.; Bao, S.; Sun, X.; Li, K. One-step synthesis of magnetic catalysts containing Mn3O4-Fe3O4 from manganese slag for degradation of enrofloxacin by activation of peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Feng, Q.; Peng, X.; Tong, L.; Wu, J.; Lin, X.; Wei, L.; Su, M.; Shih, K.; Szlachta, M.; et al. Efficient Mn Recovery and As Removal from Manganese Slag: A Novel Approach for Metal Recovery and Decontamination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ke, X.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Ye, H. A novel double-network hydrogel made from electrolytic manganese slag and polyacrylic acid-polyacrylamide for removal of heavy metals in wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 462, 132722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, J.; Zhao, J.; Wei, X.; Chen, M.; Li, B.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Deng, Z. Synergistic harmless treatment of phosphogypsum leachate wastewater with iron-rich electrolytic manganese residue and electric field. Miner. Eng. 2023, 204, 108399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Yue, Y.; Qian, G. Synthesis and industrial applicability of a manganese slag-derived catalyst for effective decomposition of VOCs. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 208, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.; Randhawa, N.S.; Kumar, S. A review on characteristics of silico-manganese slag and its utilization into construction materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 176, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Han, F.; Hua, W.; Liu, T.; Zheng, J.; An, C.; Li, M. Preparation and properties of microcrystalline foam ceramics from silicon manganese smelting slag. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 2073–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Zhang, S.; Mei, T.; Dong, Y.; Hou, H. Mechanochemical modification of electrolytic manganese residue: Ammonium nitrogen recycling, heavy metal solidification, and baking-free brick preparation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Q.; Xue, J. Reuse of hazardous electrolytic manganese residue: Detailed leaching characterization and novel application as a cementitious material. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Luo, Q.; Feng, Q.; Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Gu, Q.; Zeng, X.; Mao, Z.; Zhu, H. Integrated use of Bayer red mud and electrolytic manganese residue in limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) via thermal treatment activation. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Luo, Y.; Yang, S. Grey correlation analysis and molecular simulation study on modification mechanism of red mud mixed manganese slag. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. Basic Research on the Preparation of Electrolytic Manganese Residue-Red Mud-Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag-Calcium Hydroxide Composite Cementitious Material and Its Mechanical Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, S.; Lakhiar, M.T.; Zhuang, S.; Lakhiar, I.W. Ternary binders and recycled turbine blade fibres in mortar: Reducing embodied carbon in coastal construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 501, 144277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zeng, Q.; Hu, J.; Zhu, W. Study on Performance Optimization of Red Mud–Mineral Powder Composite Cementitious Material Based on Response Surface Methodology. Buildings 2025, 15, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Peng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X. Experimental study on construction application of red mud-based concrete pavement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 15555.12-1995; Solid Waste-Glass Electrode Test-Method of Corrosivity. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1995.

- HJ 766-2015; Solid Waste-Determination of metals-Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB/T 14848-2017; Standard for Groundwater Quality. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People's Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Sun, C.; Chen, J.; Tian, K.; Peng, D.; Liao, X.; Wu, X. Geochemical characteristics and toxic elements in alumina refining wastes and leachates from management facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Cui, K.; Lyu, J.; Liu, H.; Qiu, J. Hazards and Dealkalization Technology of Red Mud—A Critical Review. Minerals 2025, 15, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title 1 | RM | EMR |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium oxide (CaO) | 16.2 | 9.3 |

| Quartz (SiO2) | 13.7 | 35.04 |

| Aluminium oxide/alumina (Al2O3) | 17.6 | 5.97 |

| Ferric oxide (Fe2O3) | 26.7 | 12.9 |

| Sulphur oxide (SO3) | 0.2 | 13.67 |

| Anatase (TiO2) | 5.3 | - |

| Manganese dioxide (MnO2) | - | 7.6 |

| Sodium oxide (Na2O) | 5.9 | - |

| Magnesium oxide (MgO) | 0.7 | - |

| Potassium oxide (K2O) | 0.1 | - |

| Chromium(III) oxide (Cr2O3) | 0.2 | - |

| LOI | 11.6 | 15.52 |

| Mixture | RM (wt%) | EMR (wt%) | Activator (wt%) | RM: EMR | Water-to-Binder Ratio | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 35% | 35% | 30% | 1: 1 | 0.4 | |

| P2 | 15% | 45% | 40% | 1: 3 | 0.4 | |

| P3 | 24% | 36% | 40% | 2: 3 | 0.4 | |

| P4 | 30% | 30% | 40% | 1: 1 | 0.4 | Environmental analysis |

| P5 | 36% | 24% | 40% | 3: 2 | 0.4 | |

| P6 | 12.5% | 37.5% | 50% | 1: 3 | 0.4 | |

| P7 | 20% | 30% | 50% | 2: 3 | 0.4 | |

| P8 | 25% | 25% | 50% | 1: 1 | 0.4 | |

| P9 | 30% | 20% | 50% | 3: 2 | 0.4 | |

| P10 | 10% | 30% | 60% | 1: 3 | 0.4 | |

| P11 | 16% | 24% | 60% | 2: 3 | 0.4 | |

| P12 | 20% | 20% | 60% | 1: 1 | 0.4 | |

| P13 | 24% | 16% | 60% | 3: 2 | 0.4 |

| Number | Corrosive | Cr6+ | NH4+-N | Mn | As | Cd | Pb | Hg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groundwater Class III standard | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.001 | |

| 1# (pH8) | 10.03 | ND | 6.81 | ND | 0.0012 | ND | ND | ND |

| 2# (pH9) | 10.1 | ND | 7.09 | 0.0052 | 0.0019 | ND | ND | ND |

| 3# (pH10) | 10.32 | ND | 5.26 | ND | 0.001 | ND | ND | ND |

| 4# (pH11) | 10.7 | ND | 2.12 | ND | 0.0012 | ND | ND | ND |

| 5# (pH12) | 10.75 | ND | 0.421 | ND | 0.0012 | ND | ND | ND |

| 6# (pH13) | 11.04 | ND | 0.404 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.00004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, Y.; Duan, Y. Preparation of Red Mud-Electrolytic Manganese Residue Paste: Properties and Environmental Impact. Buildings 2026, 16, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010224

Chen Z, Li Y, Zhou Y, Peng Y, Duan Y. Preparation of Red Mud-Electrolytic Manganese Residue Paste: Properties and Environmental Impact. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010224

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhongping, Yongkang Li, Yuefu Zhou, Yuansheng Peng, and Yuehua Duan. 2026. "Preparation of Red Mud-Electrolytic Manganese Residue Paste: Properties and Environmental Impact" Buildings 16, no. 1: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010224

APA StyleChen, Z., Li, Y., Zhou, Y., Peng, Y., & Duan, Y. (2026). Preparation of Red Mud-Electrolytic Manganese Residue Paste: Properties and Environmental Impact. Buildings, 16(1), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010224