1. Introduction

Concrete is one of the most extensively used construction materials in civil engineering, serving as the primary component of buildings, bridges, tunnels, and various infrastructure systems due to its high strength, durability, and ease of production [

1,

2]. With the rapid advancement of modern construction and increasingly complex structural demands, conventional concrete often encounters challenges such as insufficient workability, difficulties in compaction, and quality control issues in densely reinforced or geometrically restricted regions [

3,

4]. To overcome these limitations, self-compacting concrete (SCC) has emerged as an advanced material capable of flowing under its own weight, achieving full compaction without mechanical vibration, and offering superior filling ability and consolidation performance [

5,

6]. Owing to these advantages, SCC has been increasingly adopted in high-rise buildings, long-span bridges, tunnel linings, prefabricated components, and other engineering scenarios that require high construction efficiency, improved surface quality, and enhanced durability [

7,

8]. As its application continues to expand, accurately understanding and predicting the mechanical and rheological behavior of SCC has become essential for mixture optimization, production control, and performance assurance [

9,

10,

11]. However, the properties of SCC are governed by complex interactions among multiple mixture components, resulting in strong nonlinearity and variability that traditional empirical design methods struggle to capture [

12,

13]. Consequently, the development of reliable, efficient, and data-driven predictive approaches has become a critical research focus in intelligent concrete technology and modern construction engineering [

14,

15].

In recent years, machine learning has gained widespread attention in the engineering community due to its strong capability to capture nonlinear relationships and identify complex patterns from data [

16,

17]. Improvements in computational power and data accessibility have further accelerated the adoption of machine learning techniques across various prediction tasks in civil engineering, including material performance evaluation, structural behavior assessment, construction monitoring, and quality control [

18,

19,

20,

21]. These data-driven methods demonstrate clear advantages over traditional empirical or mechanistic approaches, particularly when addressing systems governed by multiple interacting variables [

22,

23,

24,

25]. In the field of concrete materials, machine learning has increasingly become a powerful tool for forecasting mechanical strength, flow characteristics, and durability, thereby supporting mixture design optimization and intelligent construction [

26]. Consequently, data-driven predictive modeling has emerged as an important research direction for enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of performance evaluation for SCC.

A growing body of research has applied machine learning (ML) models to predict the mechanical properties of various concrete systems. Dong et al. [

27] developed a data-driven feature evaluation framework that integrates data imputation techniques with a gradient-descent algorithm using a specially designed loss function to identify key input parameters and improve empirical compressive-strength equations for concrete based on data from the Three Gorges Project. Their findings demonstrated that the proposed method is model-independent, that K-nearest neighbors provide the most reliable imputation performance, and that the optimized empirical equation significantly enhances prediction accuracy. Mohamed Abdellatief et al. [

28] proposed a hybrid ML framework incorporating linear regression, one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (OneD-CNN), SVR, and an ensemble model combining ElasticNet, RF and Gradient Boosting (GB) to predict the compressive strength of metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete using both experimental and literature datasets. Their results showed that the hybrid framework achieves substantially higher accuracy than conventional or standalone models and identified aggregate ratio, NaOH molarity and the H

2O/Na

2O molar ratio as the most influential variables. Yasmina Kellouche et al. [

29] established an ML framework integrating artificial neural networks (ANN), enhanced neural networks with combined inputs, particle swarm optimization (PSO) and a genetic algorithm to predict the compressive strength of palm-oil-fuel-ash concrete using six mixture parameters. The enhanced neural network exhibited superior performance compared with the other tested models and demonstrated robust predictive capability across diverse data ranges. In parallel, recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete (RA-SCC), produced by incorporating waste concrete and industrial by-products, has attracted increasing attention due to its potential to mitigate natural resource depletion and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Collectively, these ML models provide systematic and reliable predictions for RA-SCC and offer valuable insights for mixture-design optimization and quality control. Despite these advancements, several important research gaps remain. First, most existing studies focus on conventional or specialized concrete systems, whereas comprehensive ML investigations targeting SCC, which features pronounced multi-parameter coupling effects, are still limited. Second, many studies rely on single-model frameworks or simple model combinations and lack systematic comparisons across multiple ML algorithms together with effective hyperparameter-optimization strategies, resulting in limited generalization capability. Third, model interpretability has not been sufficiently emphasized, leaving the underlying influence mechanisms of mixture parameters inadequately understood and constraining engineering applicability. Fourth, although compressive strength has been extensively investigated, far fewer studies have examined other essential performance indicators such as slump flow, which governs the placement, flowability and construction performance of SCC.

To address the challenges arising from the nonlinear behavior and complex variable interactions of SCC, this study proposes a comprehensive data-driven prediction framework that integrates multiple ML models with advanced optimization and interpretability techniques. The novelty of this study lies in the development of an integrated, interpretable, and systematically optimized ML framework dedicated to SCC performance prediction. Unlike previous SCC-related ML studies that often focus on a single target or adopt limited optimization strategies, the main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows: (1) establishing a unified hybrid ML and metaheuristic framework for SCC prediction; (2) performing dual-target comparative evaluation of mechanical and rheological behaviors; (3) incorporating explainable-AI analysis to interpret model behavior; and (4) proposing a simplified reduced-input strategy that enhances computational efficiency and provides practical guidance for SCC mixture design. The results demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves high predictive accuracy, strong generalization capability, and clear interpretability, offering a practical and reliable tool for mixture-design optimization and intelligent decision-making in concrete engineering.

2. Methodology

The workflow of this study is presented in

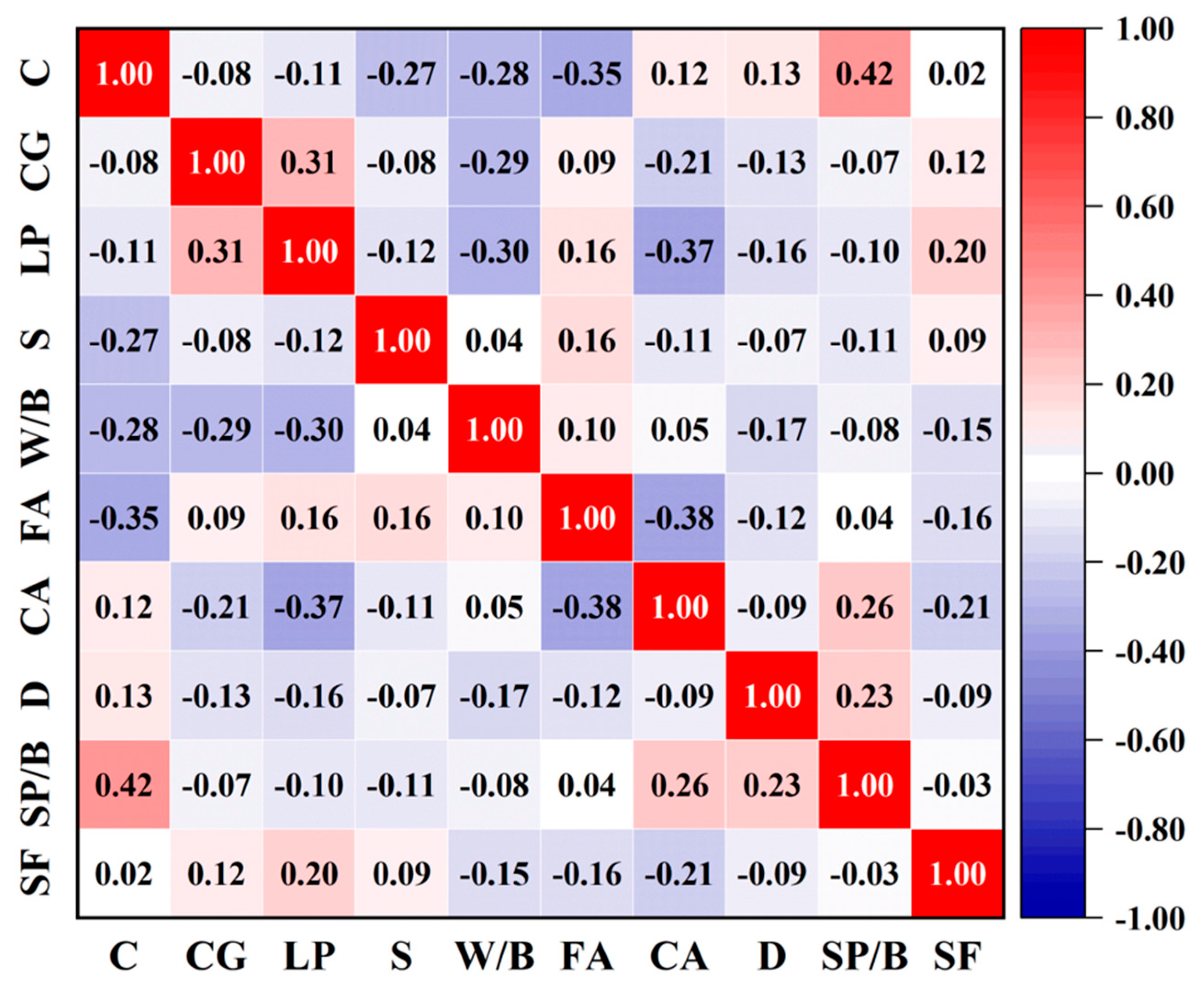

Figure 1. Two structurally consistent datasets were constructed, sharing the same input variables but differing in sample size. The first dataset contains 145 mix designs and is used for predicting the 28-day compressive strength (CS) of SCC. The second dataset comprises 224 mix designs and is employed for predicting slump flow (SF). Both datasets incorporate the same set of input features commonly adopted in SCC mixture design research. Prior to model development, all records were manually verified for completeness and consistency (e.g., variable definitions and units), and no missing entries were identified; apart from the normalization procedure, no additional data screening, filtering, or exclusion criteria (including outlier removal) were applied before model training. To address magnitude discrepancies among variables, all numerical features were normalized using the min–max method. The entire dataset was first randomly split into a training set (80%) and an independent test set (20%). The test set was strictly held out and was not involved in any stage of hyperparameter tuning, model selection, or cross-validation. All hyperparameter optimization procedures were conducted using the training set only, in which a 10-fold cross-validation scheme was embedded within the optimization loop to evaluate each candidate hyperparameter configuration. Specifically, for each candidate solution generated by the metaheuristic optimizer, the model was trained and validated via 10-fold cross-validation on the training set, and the mean cross-validated error was used as the optimization objective. After the best hyperparameters were identified, the final model was refitted on the full training set and evaluated once on the untouched test set to report the final generalization performance. To prevent data leakage during preprocessing, min–max normalization was fitted using only the training data (and, within cross-validation, fitted on the corresponding training folds) and then applied to the associated validation folds and the independent test set. Model robustness and predictive reliability were enhanced through hyperparameter tuning based on five population-based optimization algorithms: SSA, PSO, GWO, GA and WOA. A k-fold cross-validation procedure was applied throughout the modeling process to mitigate overfitting and ensure stable performance assessment. Following the initial training stage, the most influential variables governing the mechanical (CS) and rheological (SF) behavior of SCC were identified through feature importance analysis of the optimal predictive model. A streamlined model was subsequently reconstructed using only these dominant variables to further examine their contribution to predictive performance. Finally, a comprehensive interpretability analysis was conducted to provide deeper insights into how key input features influence SCC behavior and to elucidate the decision-making mechanisms of the optimized model.

2.1. Machine Learning Models

2.1.1. Random Forest (RF)

RF is an ensemble learning method that constructs a large number of independent decision trees and aggregates their outputs to produce stable and accurate predictions [

30,

31]. The algorithm relies on bootstrap sampling to generate multiple training subsets, enabling each tree to learn from different data distributions. This mechanism effectively reduces model variance and mitigates the risk of overfitting. The overall structure and operational process of RF are illustrated in

Figure 2.

During the feature-splitting process, RF introduces additional randomness by selecting only a subset of input variables at each node. This strategy increases diversity among the trees, prevents the model from relying excessively on any single feature, and enhances generalization capability. Due to its robustness to noise, ability to capture nonlinear relationships, and minimal dependence on hyperparameter tuning, RF has been widely recognized as a reliable baseline model for predictive tasks involving complex materials such as concrete.

2.1.2. eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

XGBoost is an optimized gradient boosting framework designed to improve both predictive accuracy and computational efficiency [

32,

33]. By incorporating both first- and second-order gradient information, the algorithm achieves more precise split decisions and faster convergence. XGBoost also employs regularization on tree complexity through combined L1 and L2 penalties, which effectively reduces overfitting and enhances generalization. With additional system-level optimizations such as parallelized tree construction and sparsity-aware split finding, XGBoost performs efficiently on structured datasets and has become one of the most reliable models for material property prediction.

2.1.3. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

SVR is a kernel-based machine learning method that seeks an optimal regression function by maximizing the margin around the data [

34,

35]. The use of an ε-insensitive loss function allows the model to disregard small deviations and remain robust against noise. By applying nonlinear kernel mapping, with the radial basis function (RBF) being one of the most commonly used choices, SVR can effectively capture complex relationships in material behavior. Its strong generalization ability and stability make it particularly suitable for small- to medium-sized datasets in concrete property prediction.

2.2. K-Fold Cross Validation

K-fold cross validation was applied in this study to obtain a reliable and unbiased evaluation of each machine learning model [

36,

37]. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the entire dataset was randomly partitioned into

K equally sized subsets. In the training process, one subset was sequentially selected as the validation set, while the remaining subsets were combined to form the training set. This procedure was repeated

K times, ensuring that every sample participated in both training and validation.

In this work, a 10-fold cross validation strategy (K = 10) was adopted, which provides a well-established balance between computational efficiency and the stability of performance estimation. The final evaluation metrics were calculated by averaging the results across all 10 folds, yielding a more robust reflection of each model’s generalization capability.

2.3. Hyperparametric Optimization Algorithm

Hyperparameter optimization is essential for enhancing the accuracy, stability, and generalization capability of machine learning models [

38,

39]. In this study, five nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms were employed to explore the hyperparameter search space. All of these algorithms are derived from natural phenomena and perform population-based iterative searches to locate promising regions in complex and nonlinear optimization landscapes.

SSA simulates the foraging and anti-predation behavior of sparrows and provides a flexible balance between global exploration and local exploitation [

40]. PSO is inspired by the collective movement of bird flocks and fish schools, updating particle positions based on both individual experience and group knowledge, which enables rapid convergence in continuous parameter spaces [

41]. GWO models the hierarchical structure and cooperative hunting strategies of gray wolves and exhibits strong global search capability with a relatively simple algorithmic structure [

42]. WOA imitates the bubble-net feeding behavior of humpback whales and integrates encircling and spiral movement mechanisms to reduce the likelihood of premature convergence [

43]. GA, a classical evolutionary algorithm, relies on biologically inspired operators such as selection, crossover and mutation to iteratively evolve a population of candidate solutions [

44]. In this study, SSA, PSO, GWO and WOA are categorized as swarm intelligence algorithms, whereas GA is treated as an evolutionary algorithm. Leveraging this diverse set of nature-inspired metaheuristics enhances the robustness of the hyperparameter search process and contributes to improved overall model performance.

2.4. Model Performance Evaluation Indicators

To rigorously evaluate the predictive performance of the machine learning models, five widely used statistical indicators were adopted in this study: the coefficient of determination (R

2), mean absolute error (MAE), mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). These indicators collectively assess the accuracy, error magnitude, sensitivity to large deviations, and scale-independent behavior of model predictions. The mathematical expressions of these indicators are summarized in

Table 1.

R2 quantifies the proportion of variance explained by the model, where higher values indicate stronger predictive capability. MAE measures the average absolute deviation between predictions and observations, providing an intuitive interpretation of error magnitude. MSE represents the average squared difference between predicted and true values, emphasizing the influence of large deviations due to the squaring operation. RMSE, as the square root of MSE, maintains the original unit of the target variable while remaining sensitive to significant errors. MAPE expresses prediction errors in percentage form, enabling relative comparisons across datasets with different scales.

To ensure consistent C normalized prior to composite scoring, for indicators where higher values indicate better performance (e.g., R

2), normalization was conducted using Equation (1):

For indicators where lower values indicate better performance (MAE, MSE, RMSE, MAPE), normalization was performed using Equation (2):

where

is the original value of indicator

j for model

i;

s the normalized value; and

and

denote the maximum and minimum values of indicator

j, respectively.

Following normalization, objective indicator weights were determined using the CRITIC (Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation) method. CRITIC evaluates both the variability of each indicator and its degree of conflict with other indicators. In practical SCC mixture design and quality control scenarios, model selection should not rely on a single metric because different indicators reflect different engineering concerns. While R

2 describes overall fit, error-based metrics (MAE, RMSE, and MAPE) quantify the magnitude of prediction deviations that directly relate to the risk of strength/workability misestimation in design and construction. Therefore, a composite score is used to summarize multi-metric performance into a single comparable index, enabling efficient ranking of multiple model–optimizer combinations. In this study, CRITIC is adopted to assign objective weights by considering both the dispersion of each indicator and its conflict (correlation) with others, which helps reduce redundancy and mitigates subjectivity in multi-criteria evaluation. The amount of information carried by indicator

j was computed using Equation (3):

The final weight of each indicator was obtained by normalizing the information content, as shown in Equation (4):

where

is the standard deviation of indicator

j;

is the correlation coefficient between indicators

j and

k;

represents the information conten;

denotes the CRITIC weight; and

m is the total number of indicators.

The overall performance score of each model was obtained by combining the normalized indicator values with their CRITIC-derived weights. The composite score was calculated using Equation (5):

where

is the final composite score of model

I;

is the normalized value of indicator

j for model

I; and

is the weight assigned to indicator

j.

A higher composite score indicates better overall model performance, reflecting accuracy, robustness, and stability across all evaluation dimensions.

4. Discussion

4.1. ML Models Hyperparameter Optimization

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 present the convergence behavior of five meta-heuristic algorithms, namely SSA, PSO, GWO, GA, and WOA, during the hyperparameter optimization of the RF, XGBoost, and SVR models on two independent datasets. These curves provide a clear visualization of how efficiently each algorithm reduces prediction error throughout the optimization process.

For Dataset 1, SSA demonstrates the fastest and most stable convergence among all algorithms. It rapidly reduces the fitness value within the initial iterations and subsequently maintains a steady downward trend, indicating strong global search capability. In contrast, GA and WOA exhibit slower improvement accompanied by more pronounced oscillations, reflecting weaker stability during the optimization process. A similar pattern is observed for Dataset 2, where SSA again outperforms the other four algorithms across all three models. PSO and GWO generally achieve moderate performance with smoother convergence curves, whereas GA consistently shows the slowest convergence.

The optimization results are further summarized in

Table 5, which reports the minimum RMSE obtained by each algorithm–model combination. On Dataset 1, SSA reaches the lowest RMSE values for RF (3.65), XGBoost (4.08), and SVR (6.08). These values are noticeably lower than those achieved by the remaining algorithms, demonstrating the superior accuracy of SSA. The advantage of SSA becomes even more apparent in Dataset 2, where it again obtains the smallest RMSE for all three models: 27.54 for RF, 28.91 for XGBoost, and 33.09 for SVR.

Figure 10 summarizes the optimization results for both datasets using radar charts, where a larger radial distance corresponds to lower prediction error and thus superior performance. For Dataset 1, the SSA-optimized RF, XGBoost and SVR models occupy the outermost region of the chart, forming a distinctly expanded boundary that reflects the highest overall accuracy. A similar pattern is observed for Dataset 2, in which SSA again defines the outer contour, demonstrating its consistently strong optimization capability. In contrast, GA and WOA remain closer to the center, indicating higher RMSE values and less stable optimization outcomes.

Overall, SSA exhibits the most favorable characteristics across nearly all evaluation criteria. It converges rapidly, achieves the lowest prediction errors and maintains stable optimization trajectories throughout the search process. Given its strong performance and computational efficiency, SSA is selected as the hyperparameter optimization method for the subsequent development of predictive models in this study.

4.2. Performance Comparison of Different ML Models

A detailed comparison of the results in

Table 6 and

Table 7 shows that RF provides the best overall predictive performance among the three models. Although XGBoost achieves the highest training accuracy in Dataset 1 (R

2 = 0.998, RMSE = 0.604) and similarly strong performance in Dataset 2 (R

2 = 0.997), its test accuracy drops more noticeably across both datasets, indicating a higher susceptibility to overfitting. In contrast, RF maintains a more consistent balance between training and testing performance, achieving test R

2 values of 0.967 for Dataset 1 and 0.958 for Dataset 2, along with comparatively low RMSE values. This stability highlights the strong generalization capability of RF.

The observed performance differences can be attributed to the inherent characteristics of the models. XGBoost relies on iterative boosting, which aggressively minimizes training error but can also amplify noise and local data fluctuations, particularly when dealing with smaller or more heterogeneous datasets. This tendency increases the risk of overfitting and explains its larger discrepancy between training and testing accuracy. In contrast, RF benefits from ensemble averaging across multiple decision trees, which effectively reduces variance and enhances robustness when handling complex or noisy input features. SVR, meanwhile, consistently exhibited the lowest predictive performance, with substantially higher error levels—especially on Dataset 2 (test RMSE = 37.993)—indicating limited suitability for modeling the highly variable behavior associated with SF prediction.

Figure 11 shows the scatter distribution between the predicted and experimental values for Dataset 1. RF exhibits the most concentrated clustering around the reference line, with most samples closely following the ideal prediction trajectory, demonstrating strong predictive accuracy and generalization capability for CS. In contrast, XGBoost displays slightly greater dispersion, particularly in the high-strength range, indicating a tendency toward overfitting and reduced robustness when extrapolating to larger strength values. SVR shows the weakest performance, with several points deviating markedly from the main cluster, suggesting limited capability in capturing the nonlinear relationships present in the dataset.

A clear improvement in prediction performance for SF is observed in

Figure 12. The scatter distributions become more concentrated across all three models, with RF showing the tightest clustering and minimal dispersion, indicating its superior predictive capability for rheological behavior. XGBoost maintains competitive performance; however, a subset of its predictions still falls outside the main concentration region, suggesting a degree of sensitivity to data variability. SVR once again exhibits the largest deviations, reinforcing its limited ability to capture the nonlinear interactions governing SF in SCC mixtures.

To objectively compare the overall performance of the different ML models, a composite evaluation index was developed using min–max normalization in combination with the CRITIC weighting method. This approach assigns higher weights to indicators with greater variability and lower inter-correlation, thereby ensuring a balanced and unbiased assessment across multiple evaluation metrics. The final composite scores obtained through this procedure are presented in

Figure 13.

For Dataset 1, XGBoost attains the highest composite score (0.71); however, this apparent advantage is primarily driven by its exceptionally low training errors, which also indicate a clear tendency toward overfitting. RF, in comparison, achieves a slightly lower score (0.69) but exhibits markedly better consistency between training and testing results, reflecting stronger generalization capability and more reliable predictive stability. For Dataset 2, RF again obtains the highest score (0.69), outperforming XGBoost (0.67) and demonstrating robust predictive performance in a dataset characterized by smoother variable interactions. SVR shows a noticeable improvement in Dataset 2 (0.32) relative to Dataset 1, suggesting that kernel-based regression is more suitable for this dataset, where nonlinear patterns are less dominant.

Overall, RF demonstrates the most reliable and well-balanced performance across both datasets, confirming its status as the most robust and generalizable model among the three algorithms evaluated.

4.3. ML Models Performance After Feature Selection

To evaluate the feasibility of simplifying the input variables for practical engineering applications, a feature importance analysis was conducted prior to retraining the hybrid SSA–RF model. In real construction settings, obtaining all input parameters with high precision can be costly, time-consuming or impractical; thus, reducing the number of required features is crucial for enhancing applicability and operational efficiency. RF-based importance scores were adopted due to their stability, robustness against multicollinearity and compatibility with the SSA–RF framework. The analysis was performed separately for Dataset 1 and Dataset 2, and the ranked feature importance distributions are presented in

Figure 14.

As shown in the figures, the top five variables in each dataset collectively contribute more than 80% of the total importance, indicating that essential predictive information is concentrated within a limited subset of influential features. For CS prediction (Dataset 1), the most dominant variables are S, W/B, CG, C and FA. These factors govern the core mechanisms of strength development, including paste quality, aggregate interlocking, hydration kinetics and particle packing density. In contrast, SF prediction (Dataset 2) is primarily influenced by FA, W/B, SP/B, C and CA, which is consistent with rheological principles because these variables directly affect mixture viscosity, yield stress, cohesion and lubrication behavior within the fresh mortar matrix.

The dominance of the top five variables in each dataset aligns with the fundamental mixture design principles of SCC. Parameters such as W/B and SP/B play critical roles in governing flowability and paste rheology, whereas S, CG, FA and C collectively influence packing density, water demand, matrix stiffness and hydration potential. Retaining these key features therefore preserves the essential physical mechanisms underlying both strength and flow behavior, while eliminating redundant or weakly informative variables. Based on this rationale, the top five features from each dataset were selected to construct two reduced-feature datasets, which were subsequently used to retrain the SSA–RF model for performance comparison.

Following the selection of the top five most influential features from each dataset, the SSA–RF model was retrained using the reduced input sets. As shown in

Table 8, for Dataset 1, the full-feature model achieved an R

2 of 0.967, with corresponding RMSE, MSE, MAE and MAPE values of 2.295, 5.267, 1.926 and 5.167%, respectively. After retaining only the top five features, model performance decreased, with R

2 dropping to 0.897 and the error metrics increasing to RMSE 4.088, MSE 16.713, MAE 3.551 and MAPE 10.965%. Although this decline reflects the expected loss of information associated with reducing the number of input variables, the simplified model still maintains sufficiently high predictive capability for engineering-level estimation of CS. A similar pattern is observed for Dataset 2, as summarized in

Table 9. With all features included, the SSA–RF model achieved an R

2 of 0.958 and a MAPE of 3.691%. After feature reduction, R

2 declined slightly to 0.927, while RMSE increased from 23.068 to 30.769 and MAPE rose moderately to 4.594%. Despite these changes, the simplified model continues to produce reliable predictions, with R

2 > 0.92 and MAPE < 5%, demonstrating its suitability for practical SF estimation in engineering applications.

In addition to maintaining acceptable predictive performance, the simplified SSA–RF model provides clear computational benefits. For Dataset 1, the running time decreased from 7.3 s to 5.9 s, and for Dataset 2, from 9.7 s to 6.1 s. These reductions, approximately 19% for Dataset 1 and 37% for Dataset 2, demonstrate that selecting a smaller subset of input variables can substantially lower computational cost. This improvement is particularly valuable for real-time prediction, repeated simulations, and optimization tasks that require frequent model evaluations.

From an engineering perspective, the reduced-input strategy introduces an explicit trade-off between accuracy and practicality. Although the simplified SSA–RF model shows a decrease in CS prediction performance, this accuracy level can still be acceptable for preliminary mixture design, rapid screening, and repeated evaluation scenarios, especially when only a limited set of mixture parameters is available and computational efficiency is prioritized. However, for structural or safety-critical applications where conservative and highly accurate strength estimation is required, the full-feature model is recommended, or the simplified model should be further calibrated and validated using project-specific data before being used for decision-making.

Overall, although the accuracy of the SSA–RF model decreased slightly after feature selection, the simplified models retained strong engineering applicability while substantially improving computational efficiency. These results demonstrate that the adopted feature selection strategy provides an effective balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, thereby offering a streamlined and practical workflow for SCC-related predictive tasks.

4.4. ML Model Interpretability Analysis

To deepen the understanding of the internal reasoning of the SSA–RF models and to verify whether the learned relationships are consistent with established engineering mechanisms of SCC, interpretability analyses were performed using SHAP and partial dependence plots (PDPs). The SHAP summary plots in

Figure 15a,b illustrate the global feature contributions for CS in Dataset 1 and SF in Dataset 2, respectively. The corresponding PDPs, shown in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17, depict the marginal effects of individual features on the model outputs.

As shown in

Figure 15a, the SHAP distribution for Dataset 1 indicates that S and W/B exert the strongest influence on the predicted CS, followed by CG, C and SP/B. Higher values of S are associated with positive SHAP contributions, suggesting that an adequate fine-aggregate content improves packing density, strengthens the granular skeleton and consequently enhances compressive behavior. In contrast, W/B exhibits predominantly negative SHAP values at higher levels, confirming that increased water content weakens the cementitious matrix by increasing porosity and reducing the density of hydration products. CG and C show positive effects, reflecting the benefits of higher cement strength grade and greater binder content for strength development. Variables such as FA, LP and MAXD contribute moderately, indicating that these parameters adjust microstructural or rheological characteristics but are not dominant drivers of strength within the given datasets.

For SF prediction, as shown in

Figure 15b, a distinct hierarchy of feature importance is observed. W/B, S and SP/B emerge as the most influential variables, whereas CA, LP, FA and CG exhibit comparatively smaller global contributions. High values of W/B and SP/B are strongly associated with positive SHAP values, indicating that mixtures with greater paste fluidity and lower yield stress are predicted to achieve higher slump-flow. In contrast, higher S generally contributes negatively, reflecting the increased interparticle friction caused by excessive sand content. The relatively small SHAP magnitudes of CA, MAXD and CG suggest that aggregate characteristics and cement strength have secondary influence on fresh-state flowability, with paste-related variables serving as the primary determinants.

The PDPs shown in

Figure 16 further illustrate the marginal effects of each feature on CS. C and CG exhibit nearly monotonic increasing trends, indicating systematic strength enhancement with higher binder quality and dosage. FA displays a nonlinear pattern in which moderate replacement has minimal impact, whereas excessive FA slightly reduces strength due to its dilution effect. LP and CA show rapid initial increases followed by plateau regions, suggesting the existence of optimal ranges beyond which additional increments provide limited improvement. The PDP for W/B reveals a clear decreasing trend, consistent with the well-established negative influence of excess water on strength development. The PDP for S increases over most of its practical range, indicating that appropriate fine-aggregate content enhances granular packing and contributes positively to strength. MAXD and SP/B display non-monotonic behaviors, implying that both parameters possess optimal values at which their contributions to strength are maximized before diminishing.

For SF, as shown in

Figure 17, the PDP results highlight the underlying mechanisms governing SCC flowability. W/B exhibits a strong positive influence at low to moderate levels, followed by stabilization, indicating that increasing water content enhances flow until a rheological limit is reached. SP/B shows a rapid initial rise before transitioning into a plateau, reflecting the saturation behavior of superplasticizers once the mixture achieves sufficiently low yield stress. FA and LP present nonlinear trends in which moderate dosages improve flow through lubrication and enhanced paste structure, whereas excessive amounts may induce instability or segregation, ultimately reducing slump flow. In contrast, S, CA and MAXD display decreasing or oscillatory patterns, suggesting that higher fine- or coarse-aggregate content or larger aggregate sizes hinder flow due to increased frictional resistance and blockage effects.

Overall, the SHAP and PDP analyses consistently demonstrate that the SSA–RF models capture physically meaningful relationships that align with established SCC theory. Strength predictions are primarily governed by parameters related to binder quality, paste porosity and granular packing, whereas SF behavior is predominantly influenced by rheology-related variables such as W/B and SP/B. These interpretability results not only confirm the reliability of the proposed models but also offer practical guidance for optimizing SCC mixture design in engineering applications.

4.5. Comparison with Previous Studies

Previous studies on concrete performance have made substantial contributions by systematically investigating how mixture constituents and modification measures influence fresh behavior, strength development, and durability-related properties [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Extensive experimental and mechanistic research has clarified the roles of cementitious materials, water-to-binder ratio, aggregate characteristics, mineral additions, chemical admixtures, and various additives or reinforcement strategies in governing microstructure evolution and macroscopic performance. These works provide the fundamental scientific basis and practical guidance for mixture design, quality control, and performance-oriented engineering applications, and they remain essential for understanding the underlying mechanisms of concrete behavior [

49,

50,

51].

Building on this well-established knowledge base, the present study shifts the focus toward a data-driven modeling perspective and extends the analysis to SCC, where fresh and hardened properties are strongly coupled and influenced by complex nonlinear interactions among mixture variables. By integrating multiple ML models with metaheuristic hyperparameter optimization and incorporating explainability analyses, the proposed framework learns variable–response relationships directly from data and provides interpretable evidence that can be connected to the mechanisms reported in previous studies. In this way, the proposed approach complements prior experimental research by offering an efficient and scalable tool for multi-variable performance prediction and mixture optimization, and it helps translate existing mechanistic understanding into practical, quantitative decision support for SCC engineering.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive data-driven framework that integrates five optimization algorithms and three machine learning models is developed to predict the CS and SF performance of SCC. Two datasets containing nine mixture parameters are analyzed to evaluate model accuracy, generalization capability, computational efficiency, and interpretability. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) Among all optimization methods, SSA demonstrates the strongest hyperparameter search capability and consistently produces the lowest prediction errors. For Dataset 1, SSA achieves RMSE values of 3.65, 4.08, and 6.08 for the RF, XGBoost, and SVR models, respectively. For Dataset 2, the corresponding RMSE values are 27.54, 28.91, and 33.09 for RF, XGBoost, and SVR, respectively. These results confirm the superior global search performance and stability of SSA when optimizing nonlinear regression models.

(2) Among the three prediction models evaluated, RF demonstrates the most balanced and reliable performance. Although XGBoost achieves very high training accuracy for Dataset 1 (R2 = 0.998), its testing accuracy decreases to 0.939, indicating clear overfitting. In contrast, RF maintains strong generalization, with testing R2 values of 0.967 for Dataset 1 and 0.958 for Dataset 2, together with low error levels (RMSE = 2.295 and 23.068, respectively). RF also obtains the highest CRITIC-based comprehensive scores (0.69 for both datasets), confirming its superior robustness and engineering applicability.

(3) Feature importance analysis shows that the top five variables contribute more than 80% of the predictive information for both datasets. For strength prediction, the dominant features are S, W/B, CG, C, and FA, while for slump-flow prediction, the most influential variables are FA, W/B, SP/B, C, and CA. These key features align with established SCC mechanisms, in which mechanical behavior is governed by binder quality and packing density, and flowability is primarily controlled by rheology-related parameters. The high concentration of feature importance underscores the effectiveness of dimensionality reduction.

(4) After retaining only the top five features, the simplified SSA–RF model preserves engineering-level predictive accuracy while reducing computational cost. For Dataset 1, the simplified model achieves R2 = 0.897, RMSE = 4.088, and MAPE = 10.97%, compared with the full-feature performance of R2 = 0.967 and RMSE = 2.295. For Dataset 2, the simplified model maintains R2 = 0.927 and MAPE = 4.59%. At the same time, the computation time decreases from 7.3 s to 5.9 s for Dataset 1 and from 9.7 s to 6.1 s for Dataset 2, corresponding to reductions of 19% and 37%, respectively. These results demonstrate that feature selection offers meaningful computational advantages for real-time prediction and repeated evaluation scenarios. This reduced-input strategy represents a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. For safety-critical design decisions, the full-feature model is recommended, while the simplified model is more suitable for preliminary screening or situations with limited available input information.

(5) The SHAP and PDP analyses demonstrate that the SSA–RF model captures physically meaningful and interpretable mechanisms. Higher S and lower W/B increase predicted strength by enhancing packing density and reducing porosity, whereas higher FA and SP/B improve flowability through lubrication effects and rheological modification. Nonlinear patterns revealed by the PDPs, such as the monotonic decrease in strength with increasing W/B and the saturation behavior of SP/B for SF, are consistent with established SCC mixture design theory. These results confirm that the proposed model not only achieves high predictive accuracy but also provides strong interpretability and engineering reliability.

It should be noted that the present study is subject to several limitations. The datasets compiled from published literature remain relatively limited in size and may involve variability in material sources and test conditions; therefore, the generalization of the proposed framework to broader SCC mixtures and other concrete types should be further validated using larger and more diverse datasets, preferably with additional controlled experimental verification.

Overall, this study provides a robust, interpretable, and computationally efficient framework for predicting the mechanical and rheological behaviors of SCC. The findings offer practical guidance for mixture optimization, on-site quality control, and intelligent decision-making in modern concrete engineering.