Emerging Trends in Structural Mechanics Education: A Bibliometric Approach from the Perspective of Colombian Professors

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Q1: Who are the main authors, collaboration networks, institutions, and countries researching the subject?

- Q2: What are the leading journals for publications on this subject?

- Q3: Is research on this subject showing an increasing trend?

- Q4: Are the keywords adequately defined?

- Q5: What are the main topics of research?

- Q6: What are the most cited articles on the subject?

- Q7: What does the evidence from the analyzed research tell us about the education of structural mechanics?

- Q8: What research lines should be followed in structural mechanics education?

2. Structural Mechanics: The Author’s Perspective

3. Research Methodology

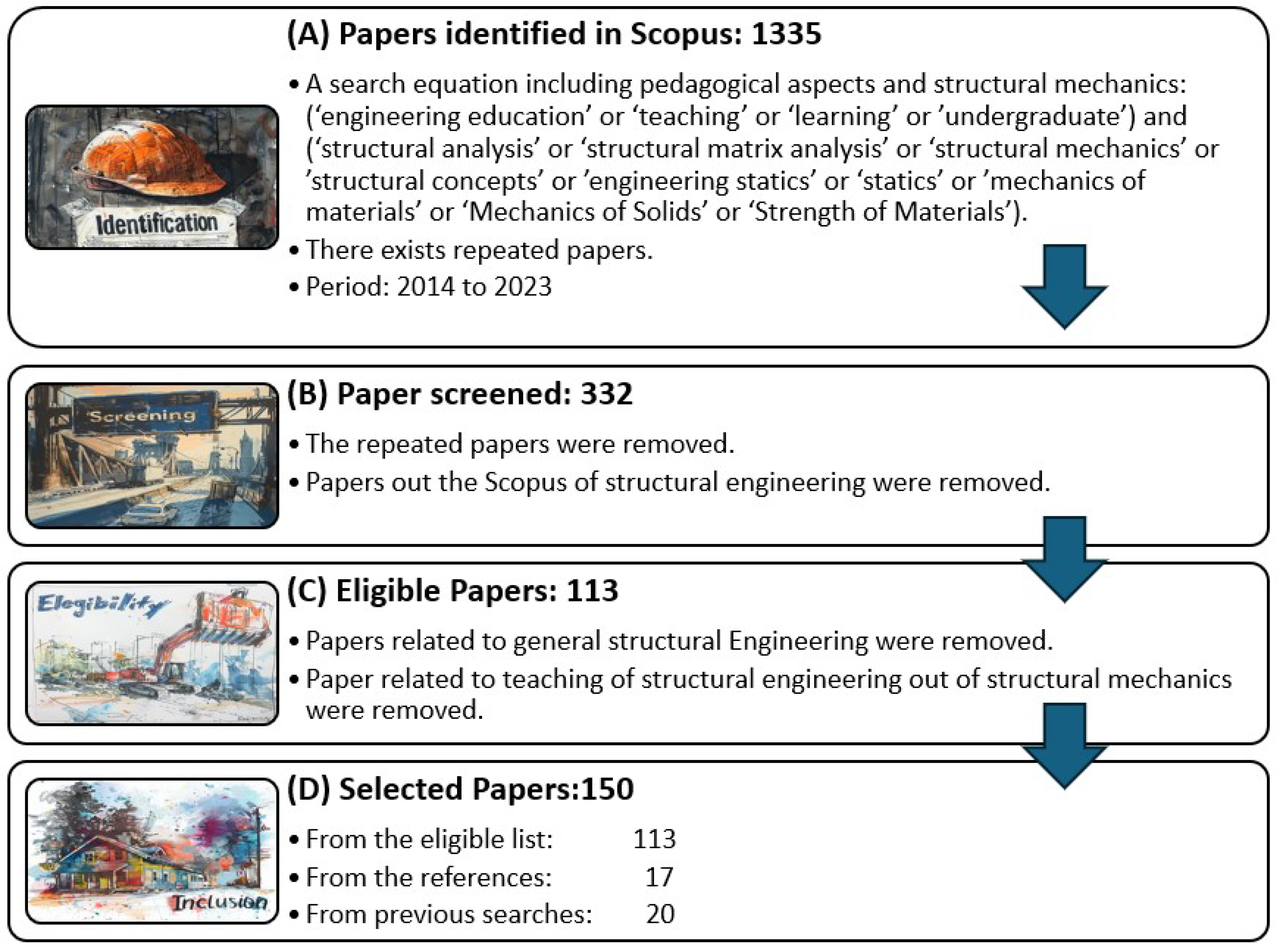

3.1. Background and Methodology Framework

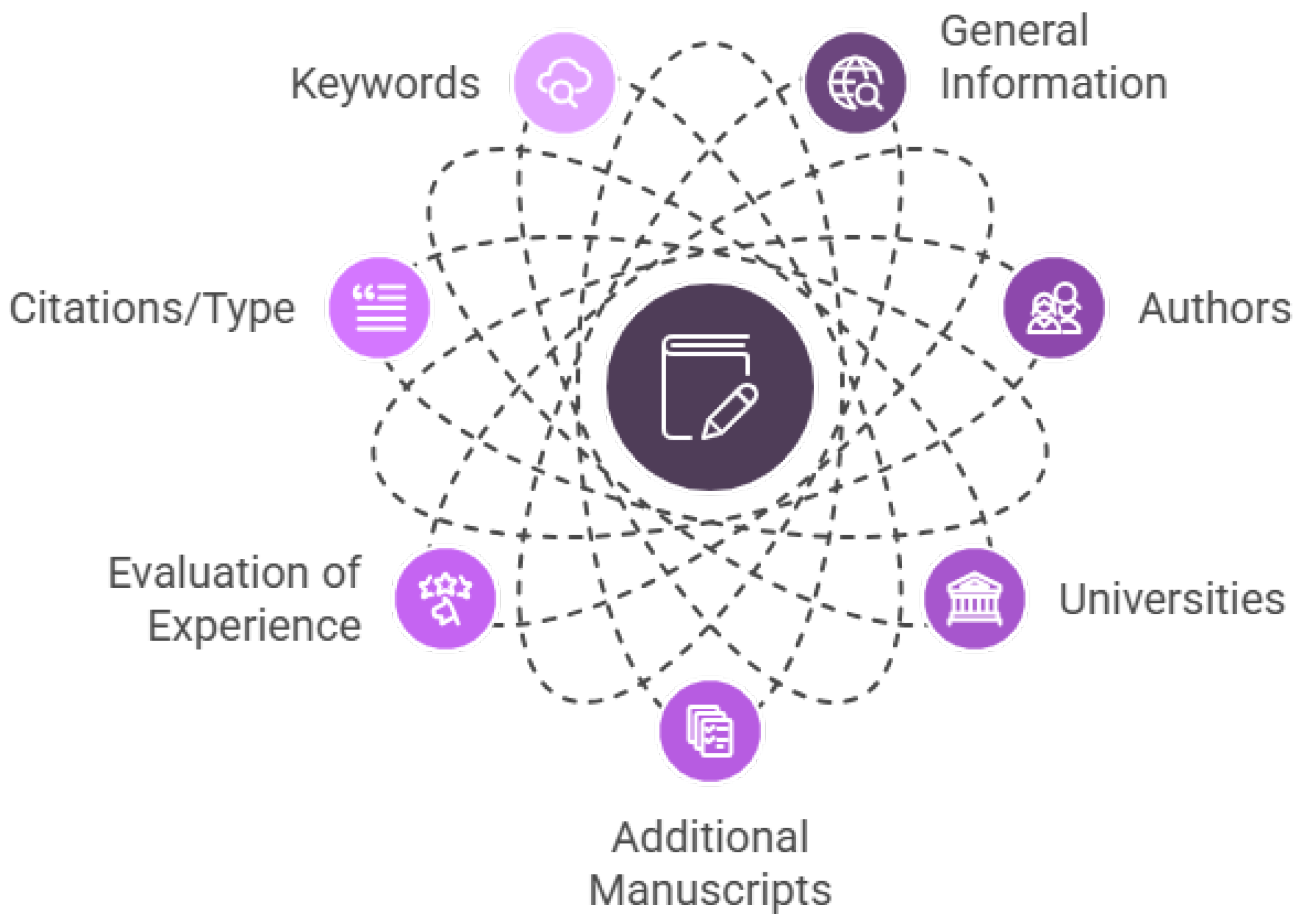

3.2. Bibliometric Structure and Research Landscape

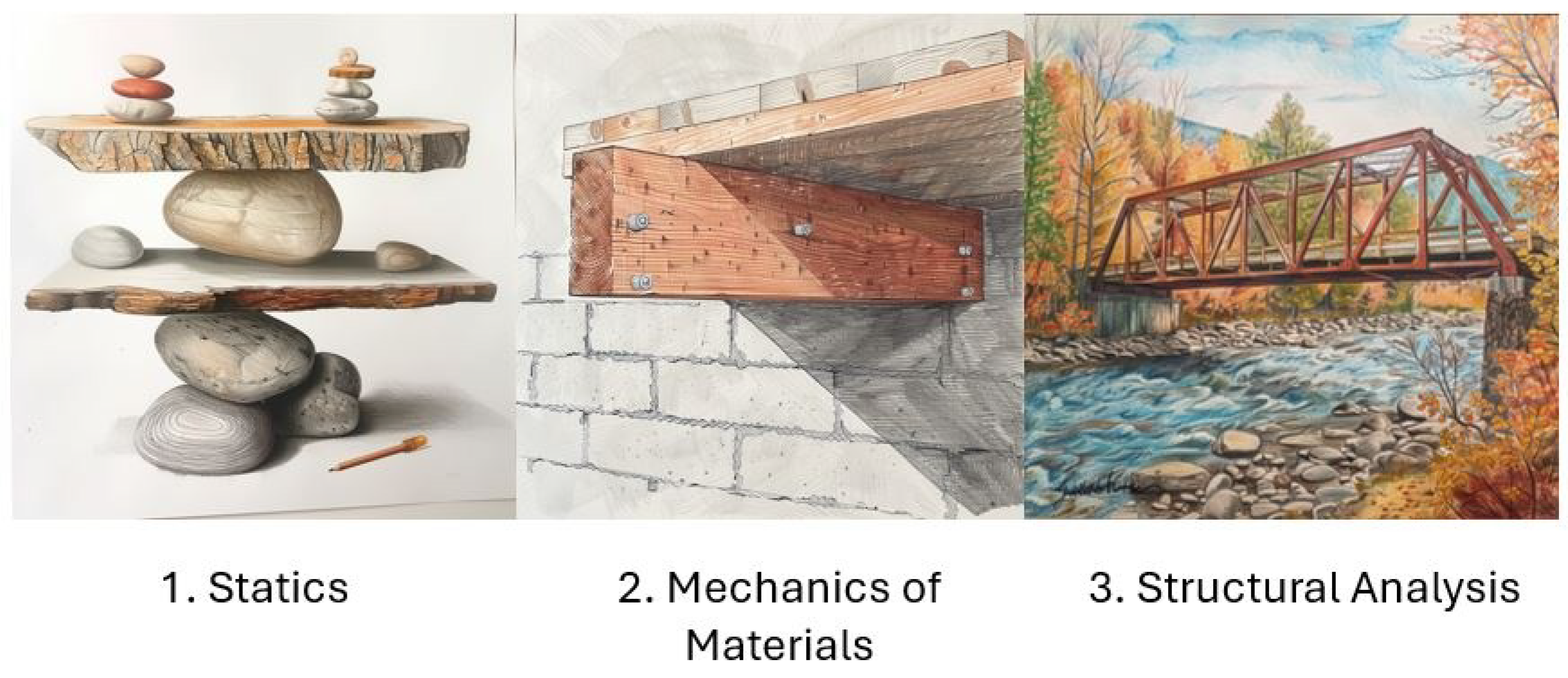

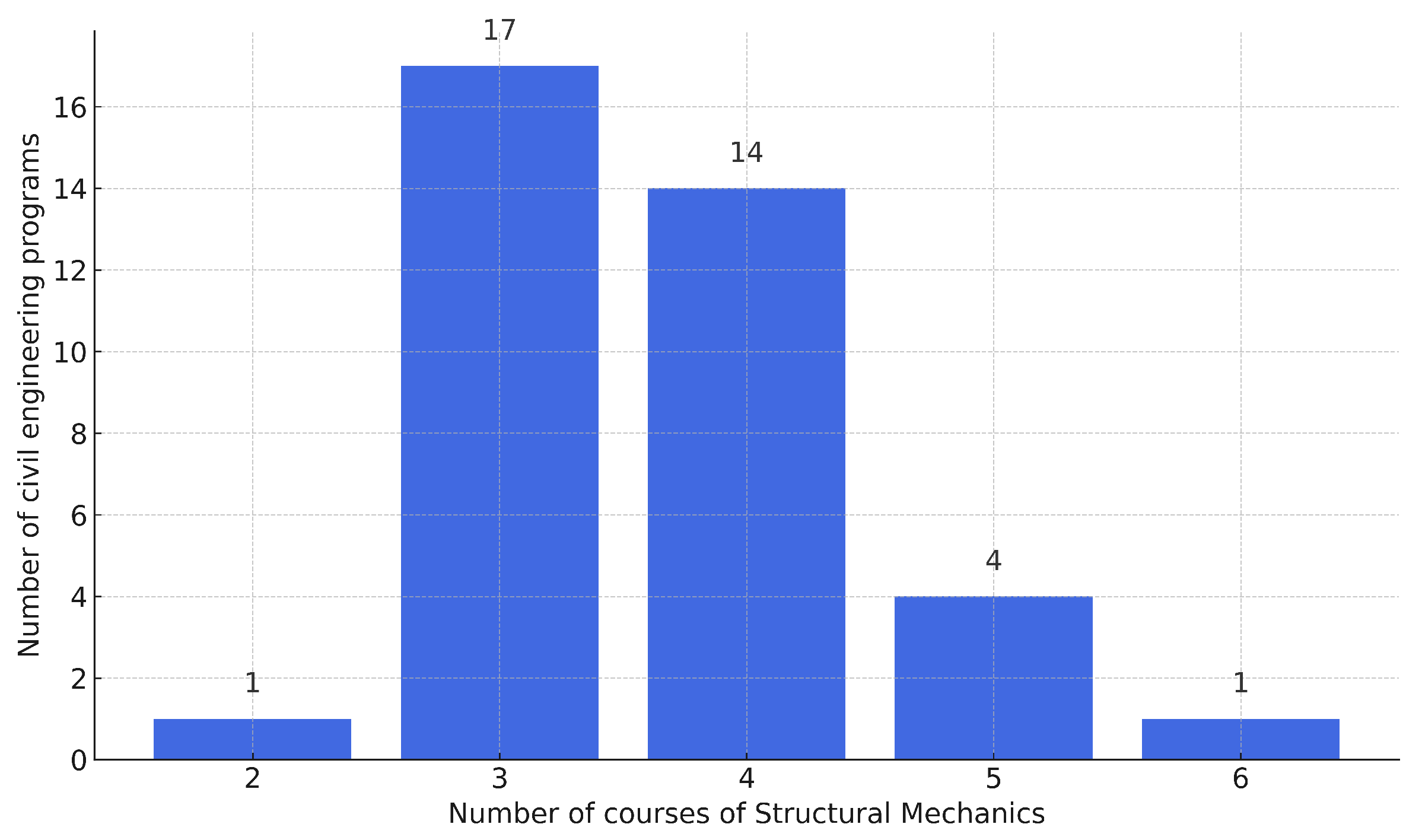

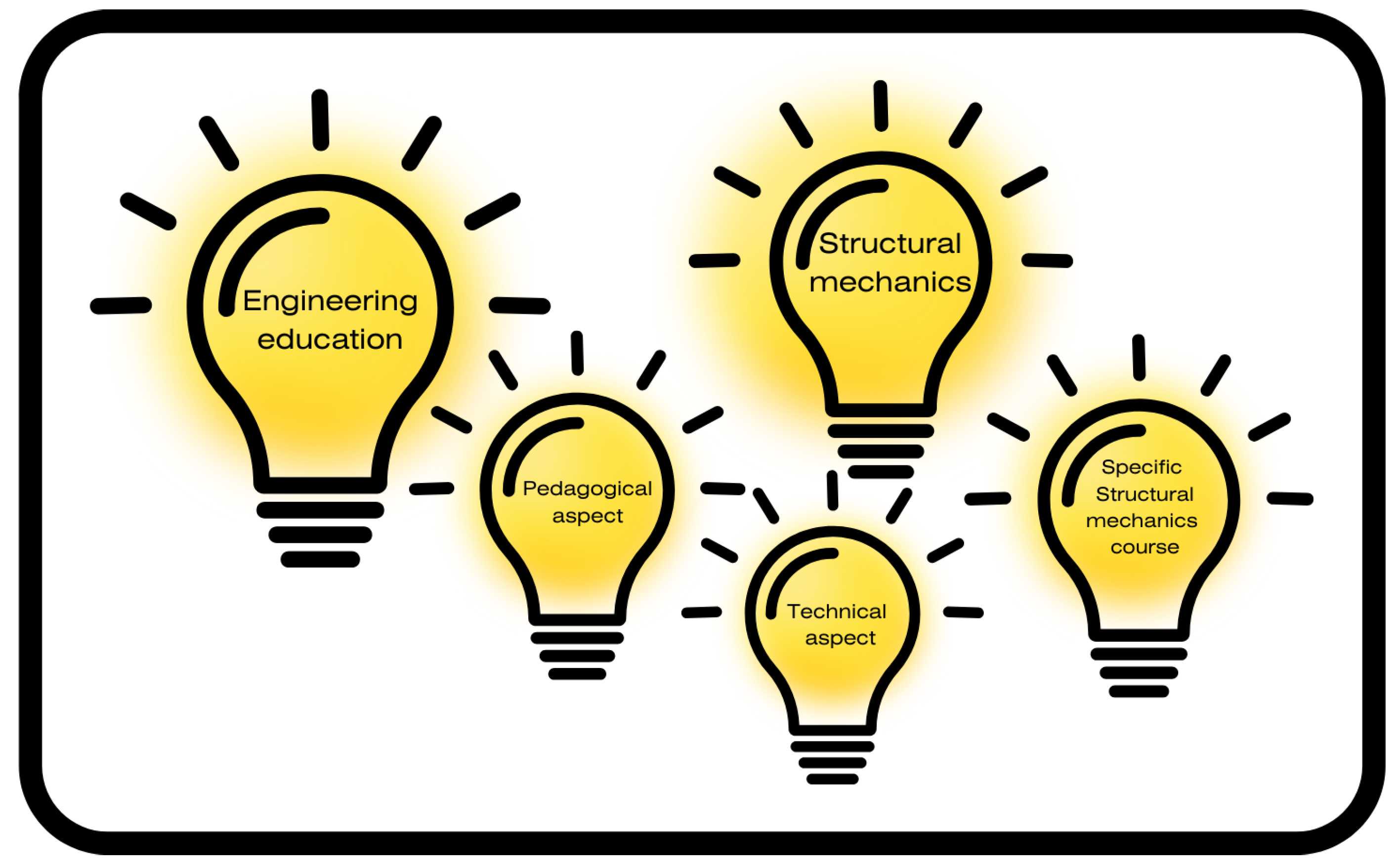

- It must address a topic related to any of the three structural mechanics courses in undergraduate education (see Figure 3).

- It must be published in a scientific journal; no other publication types were considered.

- It must have been published between 2014 and 2023.

- It must be indexed in the Scopus database, thereby ensuring the journal’s inclusion in a recognized index.

- It must be written in English.

3.3. Description of the Analysis

4. Bibliometric Analysis

4.1. General Information

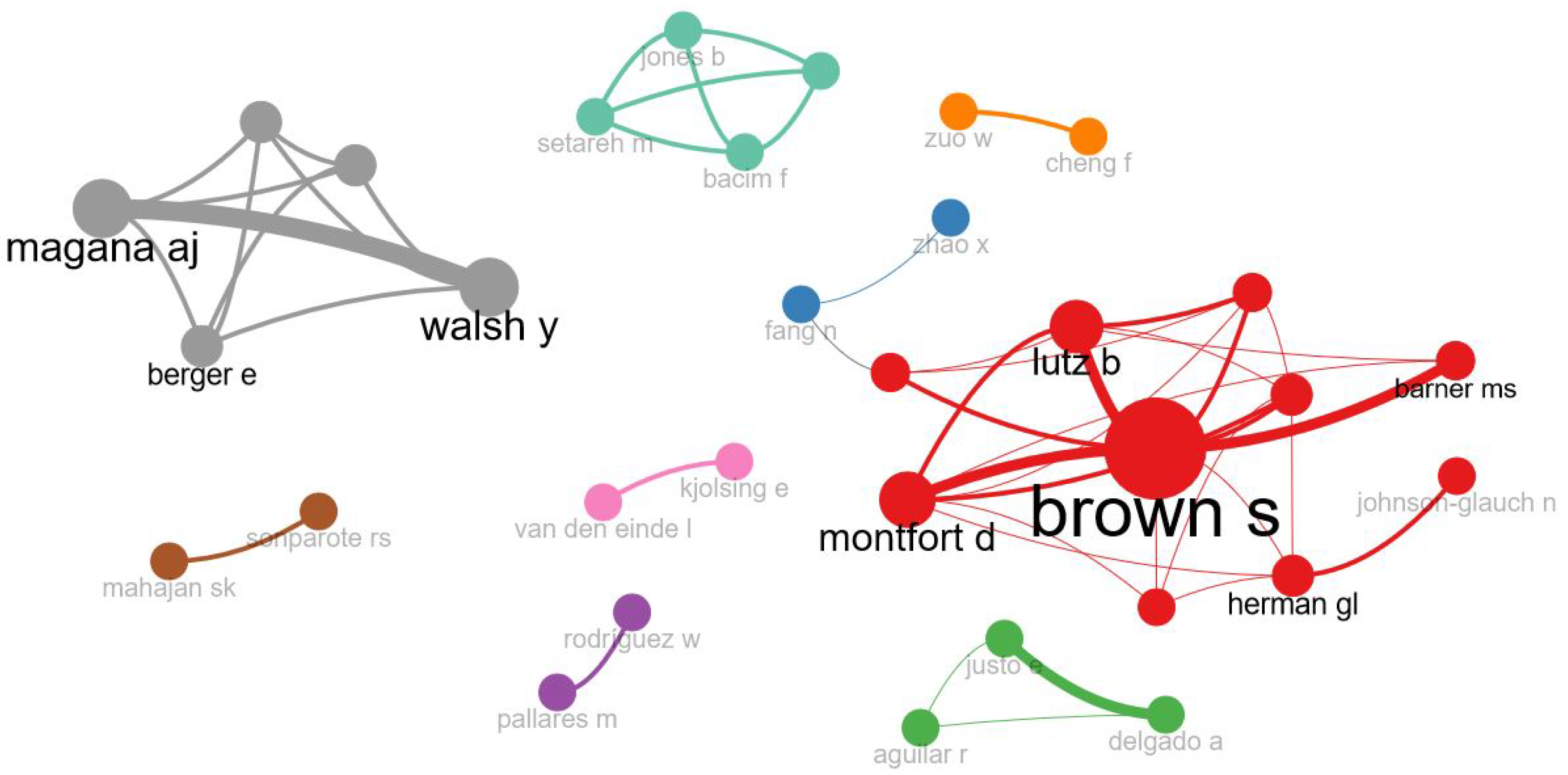

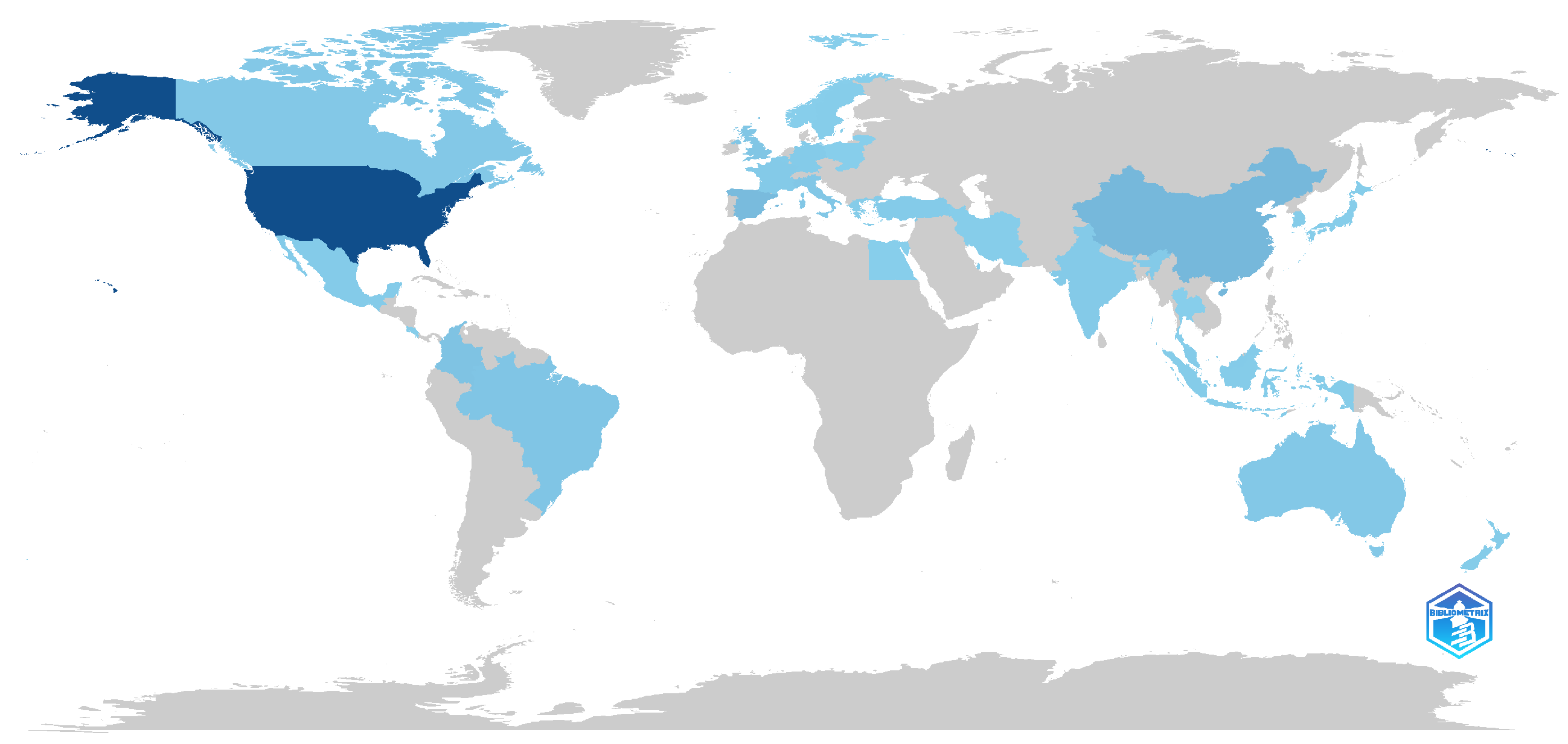

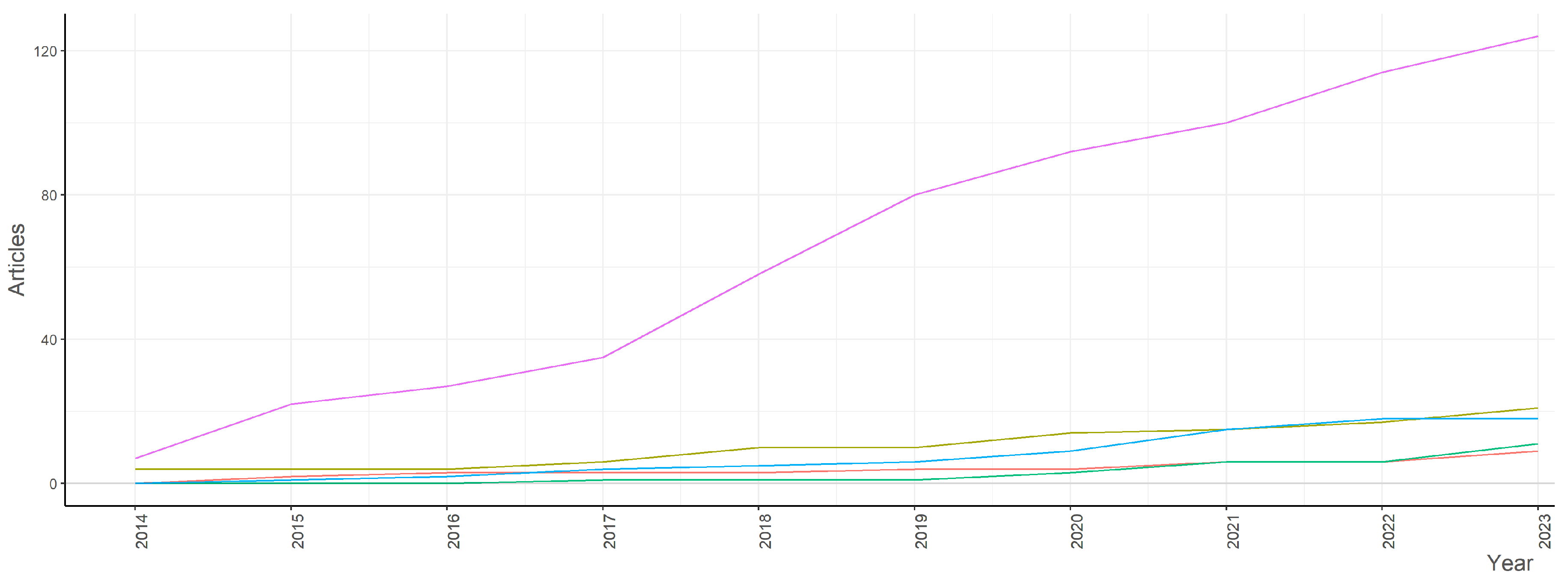

4.2. Q1: Who Are the Main Authors, Collaboration Networks, Institutions, and Countries Researching the Subject?

4.3. Q2: What Are the Leading Journals for Publications on This Subject?

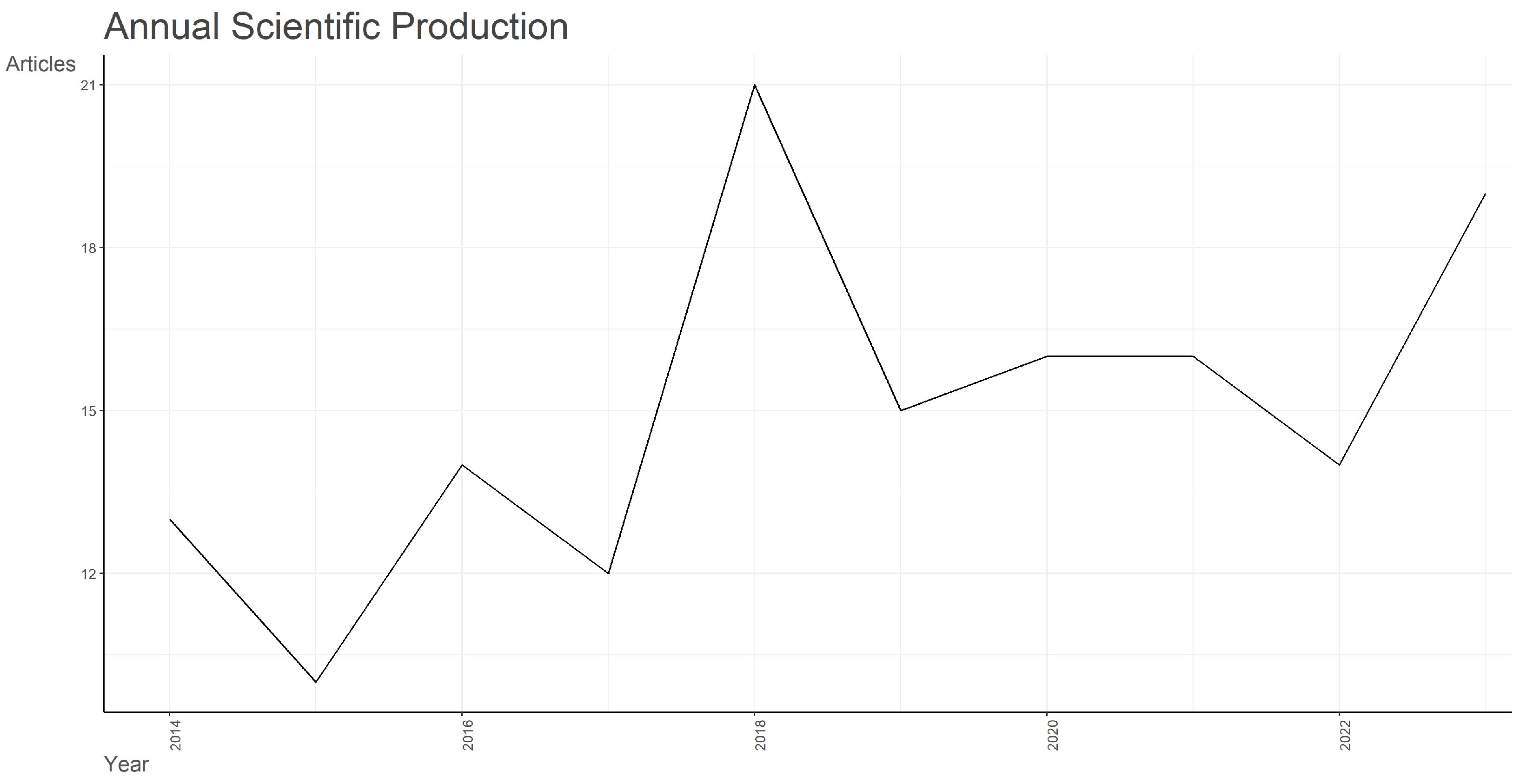

4.4. Q3: Is Research on This Subject Showing an Increasing Trend?

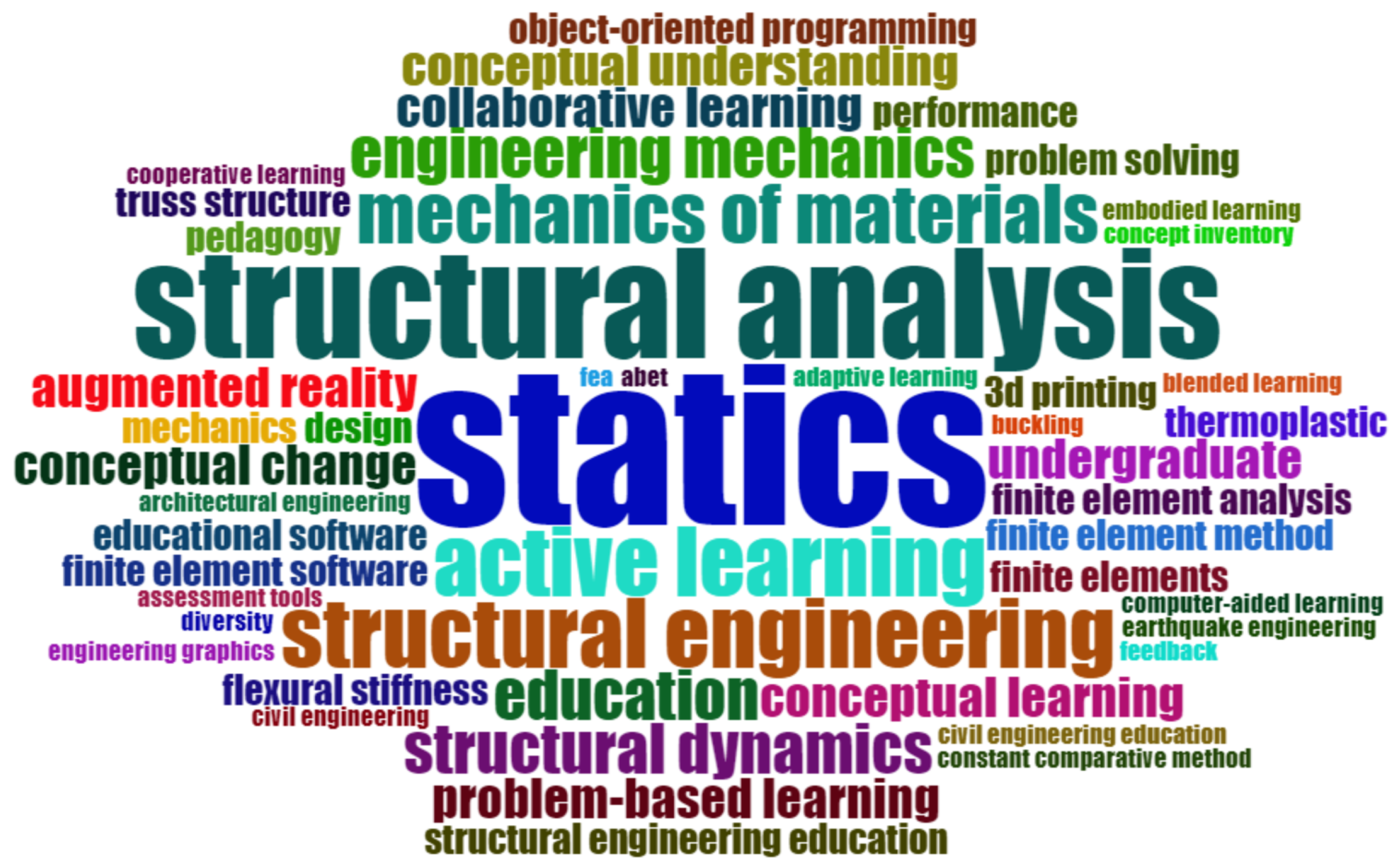

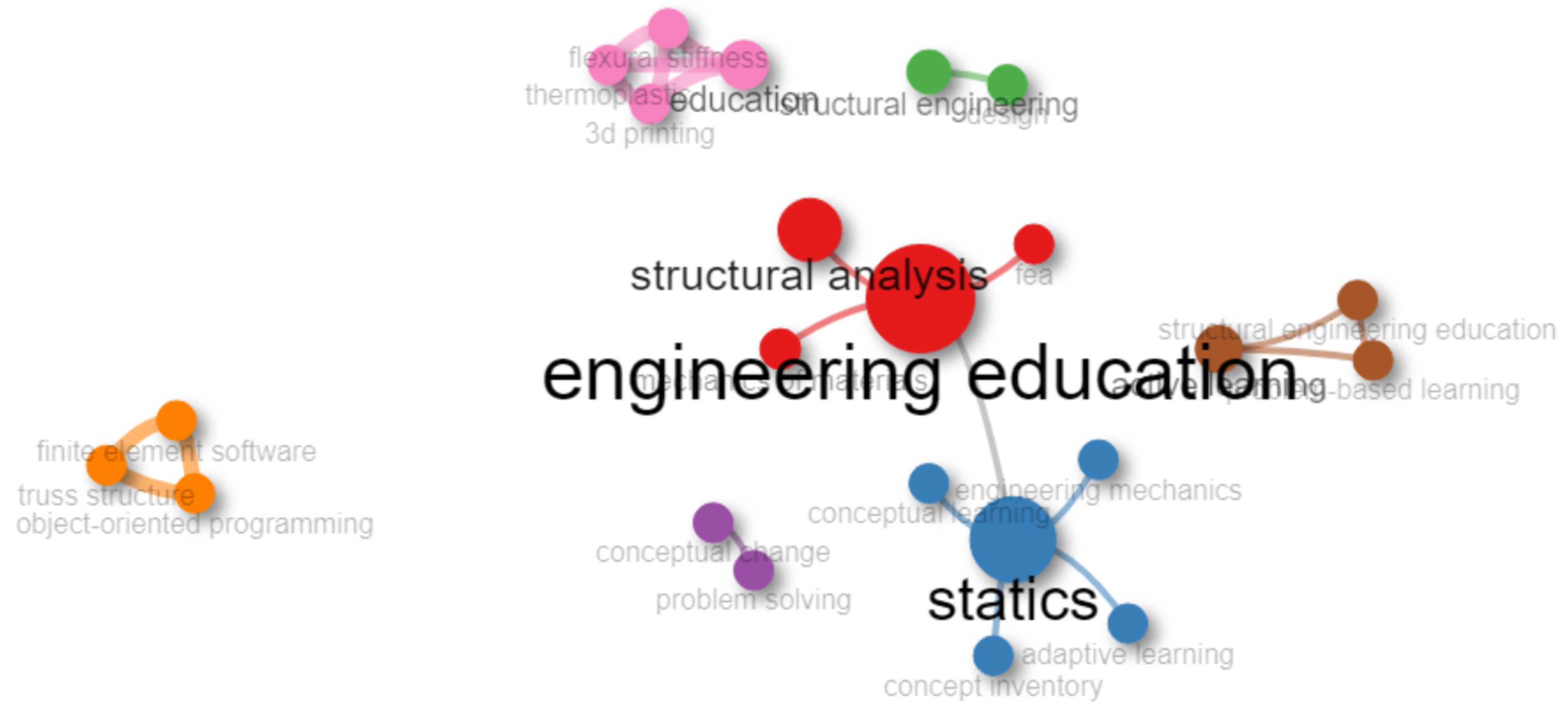

4.5. Q4: Are the Keywords Adequately Defined?

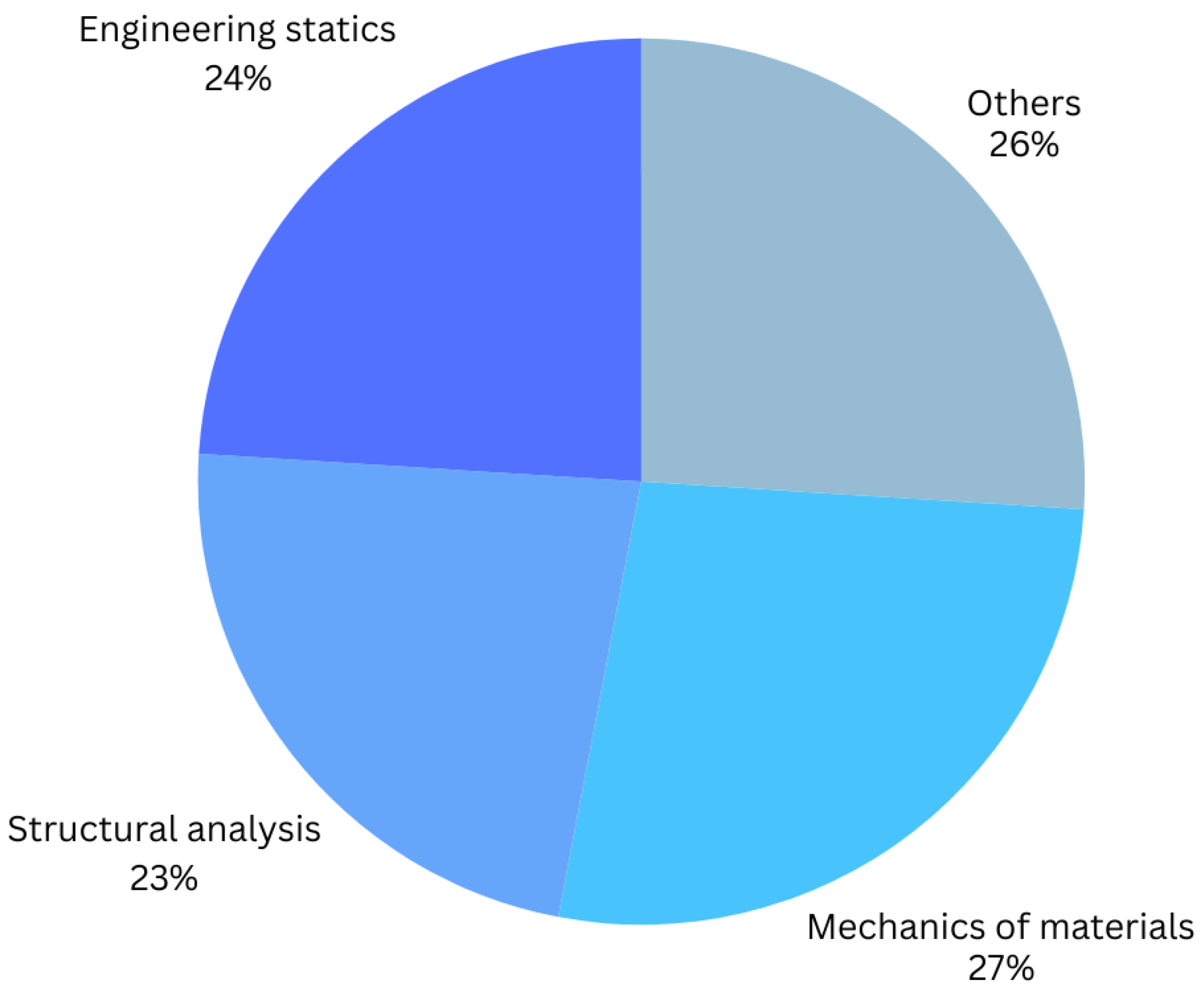

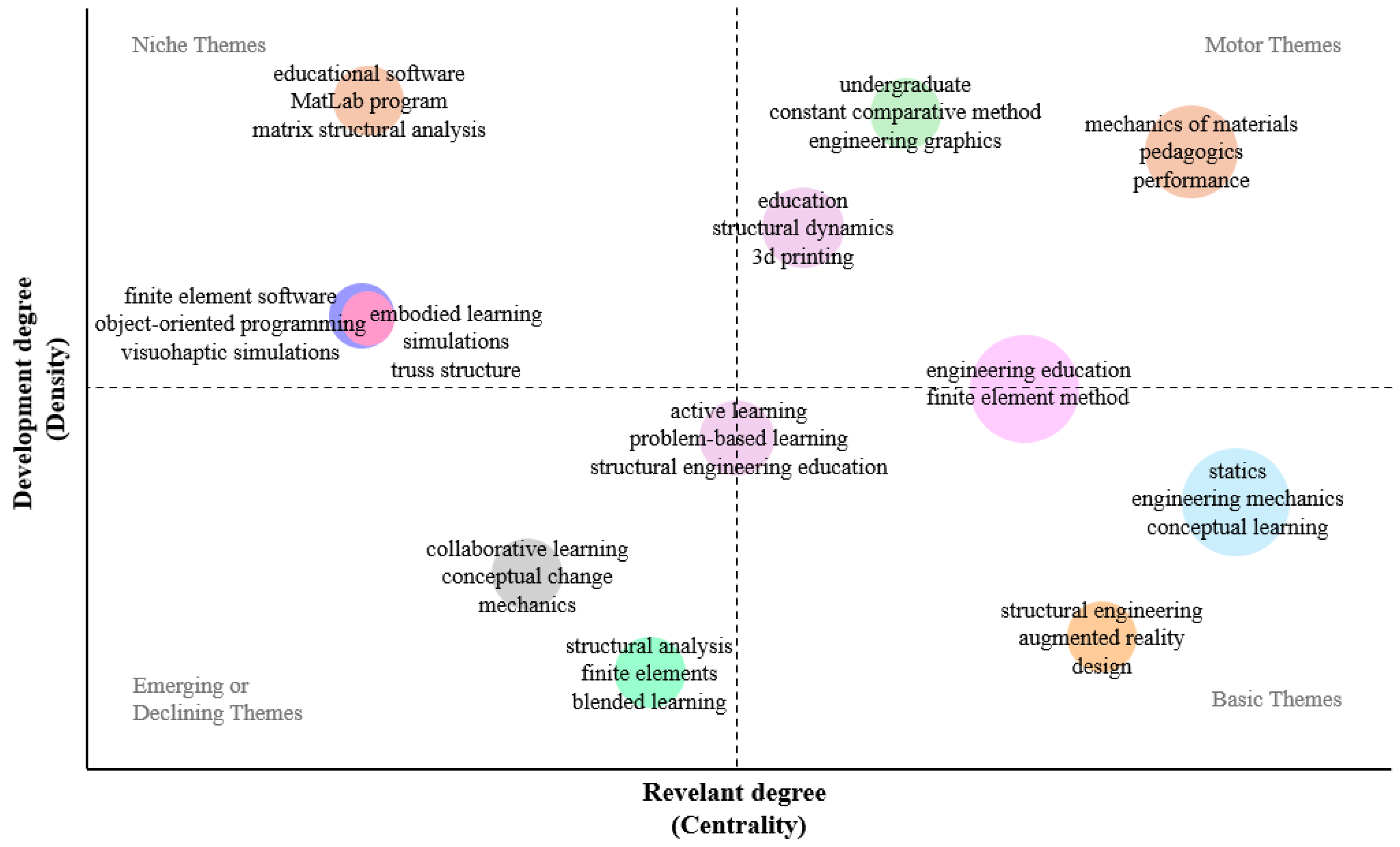

4.6. Q5: What Are the Main Topics of Research?

4.7. Q6: What Are the Most Cited Articles on the Subject?

5. Discussion

5.1. Q7: What Does the Evidence from the Analyzed Research Tell Us About the Education of Structural Mechanics?

- What proportion of professors in the sample have received formal pedagogical training?

- What strategies do universities use to promote and support pedagogical training for their professors?

- Is there evidence that pedagogically trained professors are more effective in improving student learning outcomes?

- Is it necessary to assess impacts at a global level, or is locally focused research sufficient?

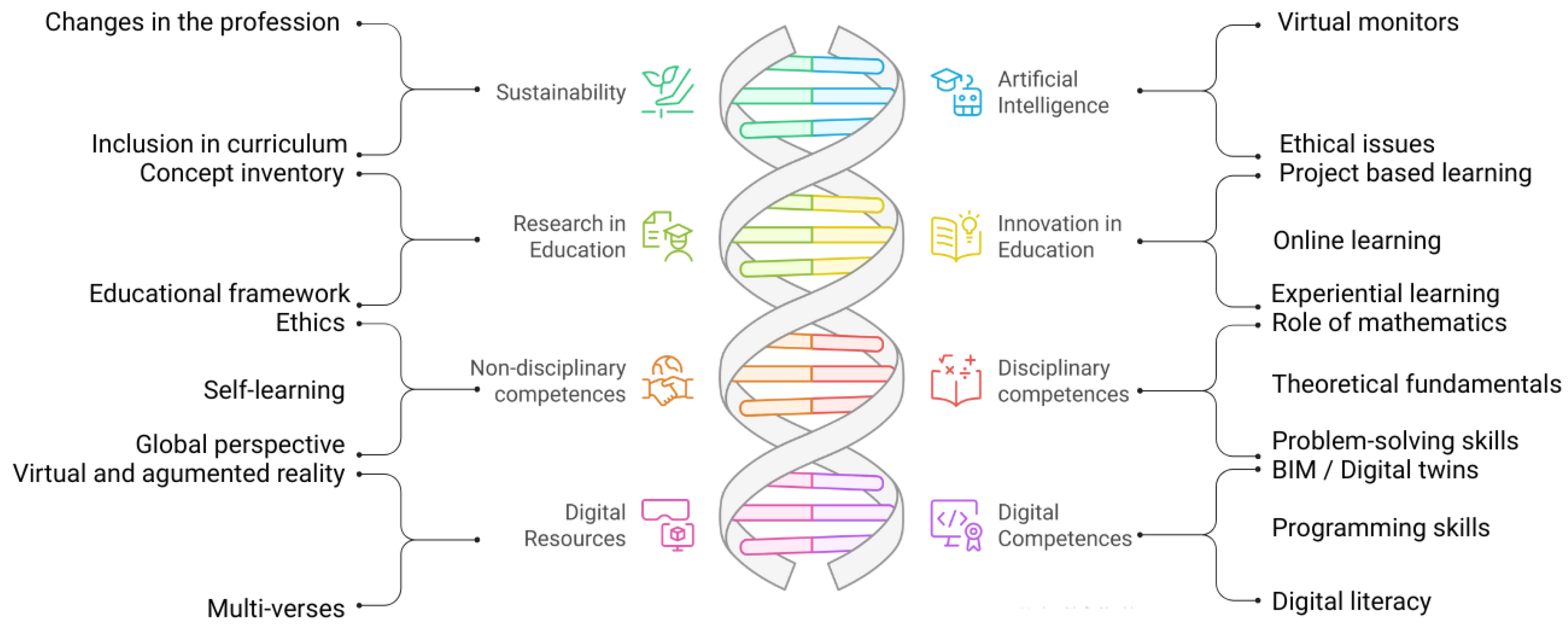

5.2. Q8: What Would Be the Research Lines to Follow in Structural Mechanics Education?

5.3. Implications of the Findings for Structural Engineering Education

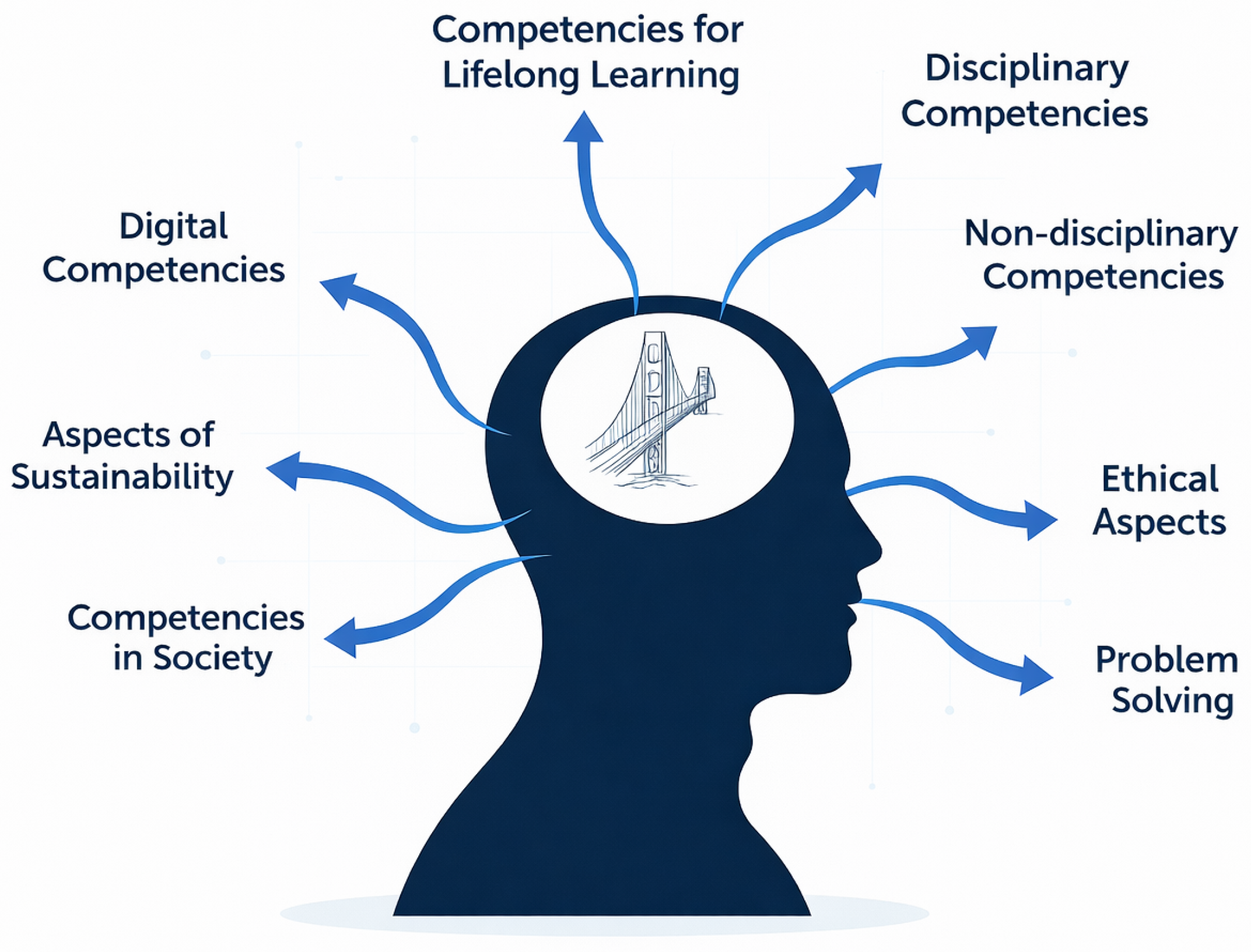

- Define a shared vision of structural engineering thinking: Explicitly articulate the set of disciplinary and transversal competencies that graduates should achieve in structural mechanics, and map these outcomes across the curriculum.

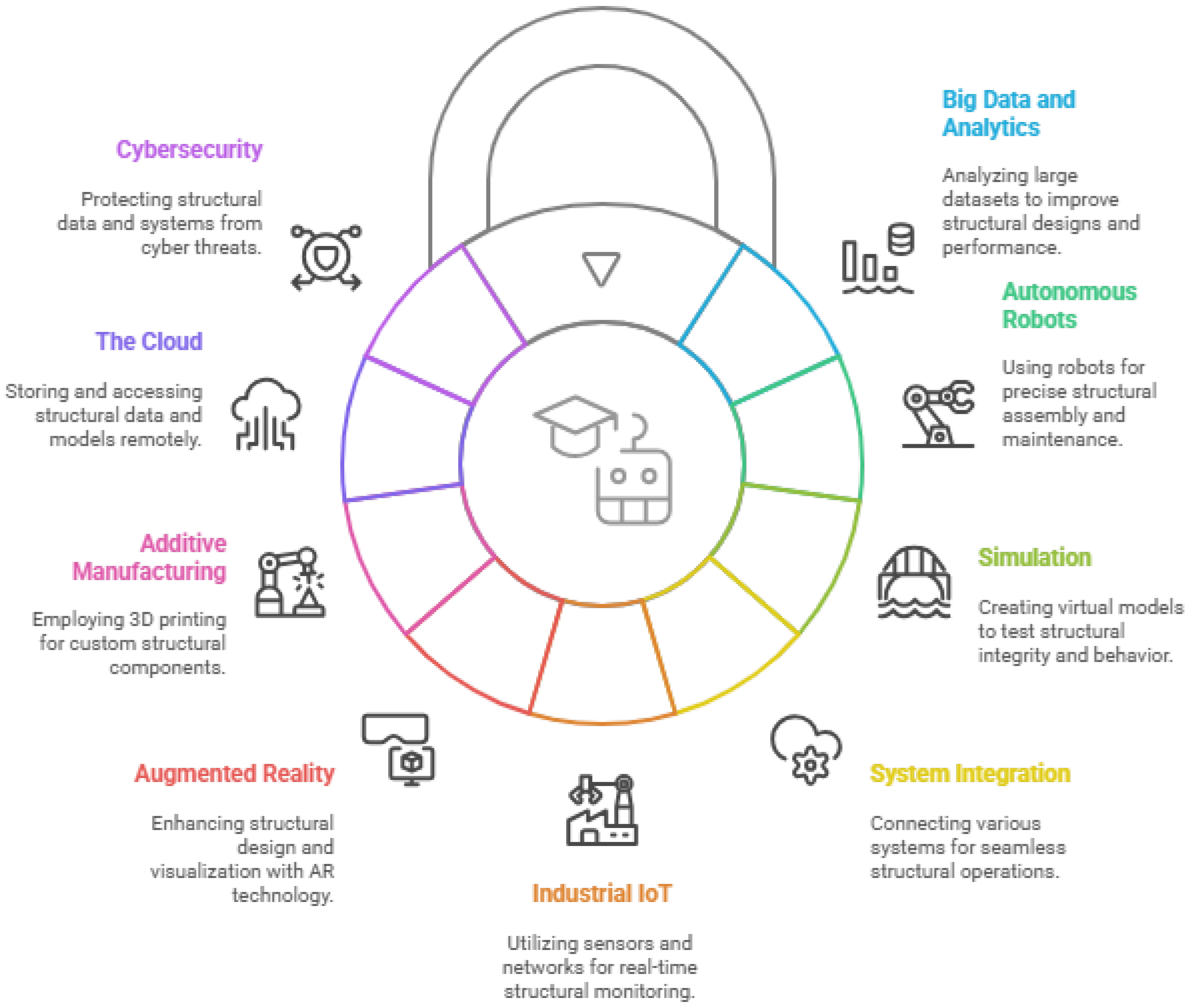

- Invest in pedagogical development for structural mechanics instructors: This involves offering sustained programs in university teaching, educational research methodologies, and assessment design, supported by institutional incentives for faculty participation. In addition, it is essential to promote educational innovation projects and develop the competencies required to build and strengthen communities of practice focused on improving teaching and learning in this field.

- Support interdisciplinary teaching and research teams: Develop the appropriate framework encompassing time, recognition, and funding to encourage collaboration amongst structural engineers, education specialists, and experts in educational technology and statistics.

- Provide and maintain educational technology and laboratory infrastructure: Allocate resources for physical models, experimental laboratories, virtual and augmented reality, BIM platforms, programming environments, and other digital tools. These elements should be incorporated into thoughtfully planned learning activities.

- Establish guidelines for the ethical and effective use of artificial intelligence: Create institutional policies and instructional guidelines that will assist educators and students in the application of generative AI and related technologies to enrich the educational process, while concurrently managing the challenges of integrity, bias, and transparency.

- Recognize and reward educational innovation and scholarship: By incorporating teaching innovation, curriculum development, and publications in engineering education into promotion and evaluation criteria, educational research can be valued equally with disciplinary research.

- Promote international and inter-institutional collaboration: Encourage joint courses, comparative studies, and shared projects in structural mechanics education across universities and countries to test the transferability of pedagogical approaches to different contexts.

- Improve the visibility and retrievability of educational research: Encourage the systematic use of structured keywords (e.g., the proposed five-keyword framework) and support institutional repositories that make educational studies in structural mechanics more accessible to the community.

6. Conclusions

- At least four contributions are documented in the analyzed sample by six authors. Dr. Brown stands out as the leading researcher in this area, with eight contributions to date. A significant proportion of the researchers are affiliated with institutions in the United States. Strengthening collaborative networks remains an urgent need.

- The leading journals in this domain are Computer Applications in Engineering Education and the Journal of Civil Engineering Education, reflecting a sustained interest in the topic. Only a small number of articles have been published in non-educational journals.

- In the last two years, at least 20 papers have been published on structural mechanics education, demonstrating the scientific community’s interest in the subject. However, the annual growth rate of scientific production remains relatively low. It is expected that the number of publications will increase as the field of research becomes more consolidated.

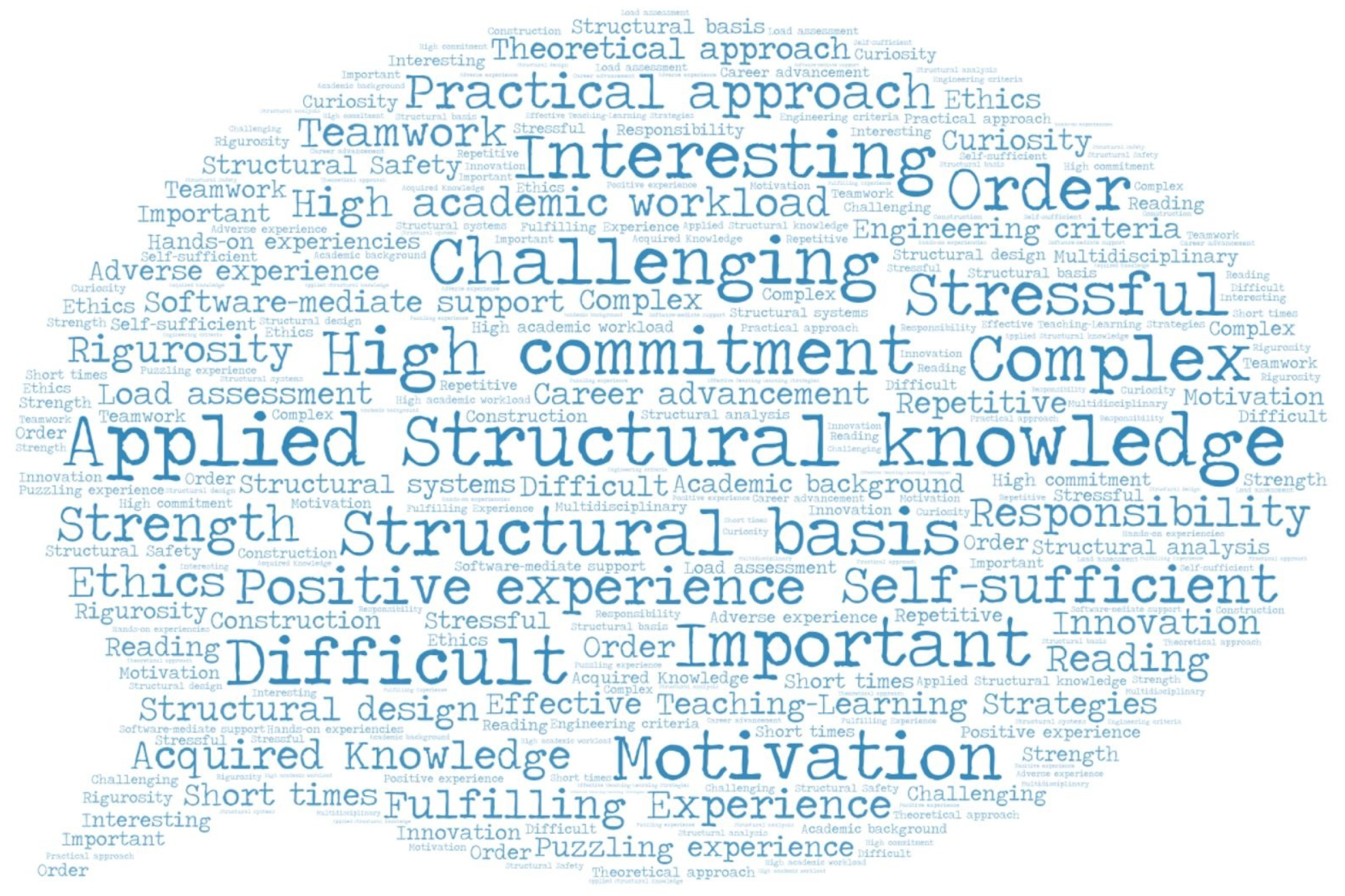

- Keyword definition represents an important challenge for effective information retrieval. “Engineering education” emerges as the most relevant keyword in the sample. This study introduces a keyword-definition strategy applicable to engineering education—particularly in relation to structural mechanics, pedagogy, technical aspects, and structural mechanics courses.

- The primary research areas identified include structural analysis software and educational laboratory-testing applications. Digital tools play a crucial role in the training of civil engineers, and experiential learning continues to attract considerable attention.

- The most frequently cited papers address multiple dimensions of the field, including problem-based learning, among other instructional approaches.

- The reviewed publications underscore key issues: the need for a clearer articulation of structural engineering thinking, an increasing tendency to incorporate modern pedagogical approaches, a persistent lack of cohesion across the literature, and the importance of integrating more global perspectives into research and practice.

- Eight central research themes were identified: sustainability, educational research, transversal skills, digital resources, artificial intelligence, educational innovation, subject-specific competencies, and digital competencies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crawley, E.; Malmqvist, J.; Östlund, S.; Brodeur, D. Rethinking Engineering Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ASCE. Civil Engineering Body of Knowledge: Preparing the Future Civil Engineer; American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCE. Commentary on the ABET Program Criteria for Civil and Similarly Named Programs; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Structural Engineering Institute. A Vision for the Future of Structural Engineering and Structural Engineers: A Case for Change; Technical Report; American Society of Civil Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Talbert, R. Flipped Learning: A Guide for Higher Education Faculty; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baden, M.S.; Major, C.H. Foundations of Problem-Based Learning; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Larmer, J.; Mergendoller, J.; Boss, S. Setting the Standard for Project Based Learning; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD): Arlington, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.; Rose, D.H.; Gordon, D. Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice; Cast Incorporated: Lynnfield, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borrego, M. Conceptual difficulties experienced by trained engineers learning educational research methods. J. Eng. Educ. 2007, 96, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, M. Qualitative methodology and its pitfalls in educational research. Qual. Quant. 2009, 43, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesiek, B.K.; Newswander, L.K.; Borrego, M. Engineering education research: Discipline, community, or field? J. Eng. Educ. 2009, 98, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, M.; Bernhard, J. The emergence of engineering education research as an internationally connected field of inquiry. J. Eng. Educ. 2011, 100, 14–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, R.M.; Hadgraft, R.G. Educational practice and educational research in engineering: Partners, antagonists, or ships passing in the night? J. Eng. Educ. 2013, 102, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinina, I.; Berestneva, O.; Sviridov, K. Educational Technologies for Forming Intellectual Competence in Scientific Research and Engineering Business. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 166, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, D.S.; Bernhardt, K.L.S.; Turochy, R.E.; Young, R.K. Transportation Engineering Curriculum: Analytic Review of the Literature. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2016, 142, 04016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbeigi, M.; Bairaktarova, D.; Morteza, A. Gamification in Construction Engineering Education: A Scoping Review. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2023, 149, 04022012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliu, J.; Aigbavboa, C. Reviewing the trends of construction education research in the last decade: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rehman, Z. Trends and Challenges of Technology-Enhanced Learning in Geotechnical Engineering Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, A.C.; Ruiz-Teran, A.M. Tradition and Innovation in Teaching Structural Design in Civil Engineering. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2007, 133, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Feng, P.; Dai, G.L. Structural art: Past, present and future. Eng. Struct. 2014, 79, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Inf. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O.; Kocaman, R.; Kanbach, D.K. How to design bibliometric research: An overview and a framework proposal. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.T. Machine learning for structural engineering: A state-of-the-art review. Structures 2022, 38, 448–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, J.; Morante-Carballo, F.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Briones-Bitar, J.; Carrión-Mero, P. A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Geotechnics and Disasters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, L.R.L.; Conesa, J.A.; Borges, A.C. A mini review on phytoremediation of fluoride-contaminated waters: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1278411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytan-Reyna, K.L.; Alvarado-Silva, C.A.; Gaytan-Reyna, S.E.; Gamarra-Rosado, V.O.; de Azevedo Silva, F. The Virtual Teaching in Statistics Course in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Research. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2024, 14, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, A.T.; Ranf, E.D.; Badea, D.; Halmaghi, E.E.; Gorski, H. Education for Sustainability—Some Bibliometric Insights. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, H.S.; Kumar, S.P. Engineering education for sustainable development: Bibliometric analysis. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2022, 36, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, S.M.; Ebrahim, N.A.; Jamali, F. The role of STEM Education in improving the quality of education: A bibliometric study. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2023, 33, 819–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishmuradova, I.I.; Chistyakov, A.A.; Chudnovskiy, A.D.; Grib, E.V.; Kondrashev, S.V.; Zhdanov, S.P. A cross-database bibliometrics analysis of blended learning in higher education: Trends and capabilities. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2024, 16, ep508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, A.; Mohammadi, S.; Hesari, P.M.; Ghaemi, M.; Riazi, H.; Sheikhi-Mobarakeh, Z. Preliminary guideline for reporting bibliometric reviews of the biomedical literature (BIBLIO): A minimum requirements. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, J.P.; Carolina, M.; Gonçalves, P.; Pestana, L.F.D.A.; Akemi, J.; Soares, H.; Boschi, R.S.; Andrade, D.F. Four challenges when conducting bibliometric reviews and how to deal with them. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 60448–60458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, S.; Nafees, M.; El-Borgi, S.; Srinivasa, A. An integrated e-learning approach for teaching statics to undergraduate engineering students. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2023, 53, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, S.; Pauletti, R.M.O.; Stockhusen, K.; Gabriele, S.; Magrone, P.; Varano, V.; Lochner-Aldinger, I. A Project-Based Approach to Learning Form Finding of Structural Surfaces. Int. J. Space Struct. 2015, 30, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.; Bir, D.D. Education Student Interactions with Online Videos in a Large Hybrid Mechanics of Materials Course. Adv. Eng. 2018, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, B.; Nelson, M. Assessment of the effects of using the cooperative learning pedagogy in a hybrid mechanics of materials course. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2019, 47, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleyaasin, M. An elementary finite element exercise to stimulate computational thinking in engineering education. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022, 30, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhan, C.; Gazi, H.C. Bringing Probabilistic Analysis Perspective into Structural Engineering Education: Use of Monte Carlo Simulations. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2014, 30, 1280–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Atadero, R.A.; Rambo-Hernandez, K.E.; Balgopal, M.M. Using social cognitive career theory to assess student outcomes of group design projects in statics. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 104, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badir, A.; Tsegaye, S.; Girimurugan, S. The Effect of McGraw-Hill Connect Online Assessment on Students’ Academic Performance in a Mechanics of Materials Course. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 39, 1242–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Balash, C.; Richardson, S.; Guzzomi, F.; Rassau, A. Engineering Mechanics: Adoption of project-based learning supported by computer-aided online adaptive assessments–overcoming fundamental issues with a fundamental subject. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 45, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, A. Advances in Engineering Education Enhancing Learning Effectiveness by Implementing Screencasts into Civil Engineering Classroom with Deaf Students. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barner, M.S.; Brown, S.A.; Lutz, B.; Montfort, D. How Engineering Faculty Interpret Pull-Oriented Innovation Development and Why Context Matters. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 1644–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Barner, M.S.; Brown, S.A.; Linton, D. Structural Engineering Heuristics in an Engineering Workplace and Academic Environments. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2021, 147, 04020014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barner, M.S.; Brown, S.A. Design Codes in Structural Engineering Practice and Education. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2021, 147, 04020013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjumea, J.M.; Prieto, D.C.; Oyaga, L.C.; Sepulveda, L.N.N.; Pulido, S.M. Development of Experimental and Collaborative Work Skills in the Students of Mechanics of Solids by Implementing a Low-Cost Torsiometer and Digital Image Correlation. Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Aprendiz. 2023, 18, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, M.; Weilenmann, A. Learning about friction: Group dynamics in engineering students’ work with free body diagrams. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2014, 39, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Payne, S.W.; RoyChoudhury, P.; Schueller, J.K. An alternative method of teaching the mechanics of bulk metal forming to undergraduates: Newtonian and Lagrangian approaches. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2022, 50, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Jiao, S.; Reid, T. Evaluating students’ understanding of statics concepts using eye gaze data. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 33, 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bishay, P.L. “fEApps”: Boosting students’ enthusiasm for coding and app designing, with a deeper learning experience in engineering fundamentals. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2016, 24, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishay, P.L. Teaching the finite element method fundamentals to undergraduate students through truss builder and truss analyzer computational tools and student-generated assignments mini-projects. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2020, 28, 1007–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, V.V.B.; Strong, A.C. Exploring the effects of learning assistants on instructional team–student interactions in statics. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2023, 51, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Montfort, D.; Perova-Mello, N.; Lutz, B.; Berger, A.; Streveler, R. Framework Theory of Conceptual Change to Interpret Undergraduate Engineering Students’ Explanations About Mechanics of Materials Concepts. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 107, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Lutz, B.; Perova-Mello, N.; Ha, O. Exploring differences in Statics Concept Inventory scores among students and practitioners. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 108, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Campos, M.; Rodrigues, M.A.C.; Camargo, R.S.; Kiepper, L.S. A unified educational mobile application to aid in teaching solid mechanics using interactive Mohr’s circle. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2023, 53, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canu, M.; Duque, M.; de Hosson, C. Active Learning session based on Didactical Engineering framework for conceptual change in students’ equilibrium and stability understanding. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 42, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, A.M.A.; Atadero, R.A.; Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, A.; Baker, D.W. Linking Engineering Students’ Professional Identity Development to Diversity and Working Inclusively in Technical Courses. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2021, 147, 04021012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, R.; Oller, S. Designing Experiments Using Digital Fabrication in Structural Dynamics. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2017, 143, 05016011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, R.; Codony, D.; Toledo, Á. From physical to digital in structural engineering classrooms using digital fabrication. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2017, 25, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, R.; Claure, F.; de Coss, O. Development of VR/AR Applications for Experimental Tests of Beams, Columns, and Frames. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2020, 34, 05020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimellaro, G.P.; Domaneschi, M. Development of Dynamic Laboratory Platform for Earthquake Engineering Courses. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2018, 144, 05018015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, J. Using the Flipped Classroom Model in a Junior Level Course to Increase Student Learning and Success. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2020, 146, 05020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.M.; Augarde, C.E. AMPLE: A Material Point Learning Environment. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2020, 139, 102748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.L.D. Using learning objects to teach structural engineering. Int. J. Online Eng. 2016, 12, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dart, S.; Lim, J.B.P. Three-Dimensional Printed Models for Teaching and Learning Structural Engineering Concepts: Building Intuition by Physically Connecting Theory to Real Life. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2023, 149, 05022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoz, J.L.D.L.; Vieira, C.; Arteta, C. Self-explanation activities in statics: A knowledge-building activity to promote conceptual change. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 112, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echempati, R. New Idea to Enhance Better Understanding of Free Body Diagrams in Solid Mechanics Course. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2020, 34, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, L.E.; Barrientos, D.R.Q.; la Peña, J.A.D.D.; de Jesús Balvantín García, A.; Leyva, P.A.L. Integration of Numerical, Theoretical & Experimental Methods for the Calculation and Measurement of Strains in an Experimental Stress Analysis Lecture. Exp. Tech. 2018, 42, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essig, R.R.; Troy, C.D.; Jesiek, B.K.; Buswell, N.T.; Boyd, J.E. Assessment and Characterization of Writing Exercises in Core Engineering Textbooks. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2018, 144, 04018007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, N.; Zhao, X. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Learning Style Preferences between American and Chinese Undergraduate Engineering Students. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2014, 30, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, B.; Johnson-Glauch, N.; Choi, D.S.; Herman, G.L. When am I ever going to use this? An investigation of the calculus content of core engineering courses. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 109, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.J.; Fatehiboroujeni, S.; Fisher, E.M.; Ritz, H. A Hands-on Guided-inquiry Materials Laboratory that Supports Student Agency. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2023, 11, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, J.; McCormick, J.; El-Tawil, S. Improving Student Understanding of Complex Spatial Arrangements with Virtual Reality. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2018, 144, 04017013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foutz, T.L. Using argumentation as a learning strategy to improve student performance in engineering Statics. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 44, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, S.; Schevenels, M.; Dooms, D.; Jansen, M.; Wambacq, J.; Lombaert, G.; Degrande, G.; Roeck, G.D. Stabil: An educational Matlab toolbox for static and dynamic structural analysis. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2021, 29, 1372–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederich, J.; Pfaller, S.; Steinmann, P. A web-based tool for the interactive visualization of stresses in an infinite plate with an elliptical hole under simple tension: www.ltm.fau.de/plate. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2016, 86, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvreau, P. Sustainable education for bridge engineers. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 5, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Kuester, F. Integrative Simulation Environment for Conceptual Structural Analysis. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2015, 29, B4014004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, J.W.; Arboleda, D.; Kim, N.J.; Chin, S.J.; Britton, J.C.; Secada, W.G. An active learning approach to teach distributed forces using augmented reality with guided inquiry. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 32, e22703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, L. An engineering-problem-based short experiment project on finite element method for undergraduate students. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, O.; Fang, N. Spatial Ability in Learning Engineering Mechanics: Critical Review. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2016, 142, 04015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, O.; Brown, S.; Pitterson, N. An Exploratory Factor Analysis of Statics Concept Inventory Data from Practicing Civil Engineers. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 33, 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J.H. Teaching Students How to Evaluate the Reasonableness of Structural Analysis Results. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritos, N. Hands-on experiential learning of structural mechanics. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2019, 20, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, S.; Masek, A.; Mahthir, B.N.S.M.; Rashid, A.H.A.; Nincarean, D. Association of interest, attitude and learning habit in mathematics learning towards enhancing students’ achievement. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 6, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.D.; Ahn, B. Student video viewing habits in an online mechanics of materials engineering course. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2018, 8, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Goh, Y.M.; Lin, A. Educational impact of an Augmented Reality (AR) application for teaching structural systems to non-engineering students. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 50, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ong, S.K.; Nee, A.Y.C. An approach for augmented learning of finite element analysis. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2019, 27, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wen, M.; Yang, T.; Fan, B. An effective teaching strategy for engineering mechanics to develop structural optimization modeling skills of undergraduates. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2020, 48, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsu, N.J.; Olaogun, O.P.; Oje, A.V.; Carnell, P.H.; Morkos, B. Investigating students’ motivational goals and self-efficacy and task beliefs in relationship to course attendance and prior knowledge in an undergraduate statics course. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 112, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, K.; Farrell, S.; Hartman, H.; Forin, T. Integrating Inclusivity and Sustainability in Civil Engineering Courses. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 38, 727–741. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi, R.; Milanovic, I. Building Virtual Laboratory with Simulations. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022, 30, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Bell, A.; Wu, Y. The philosophical basis of Seeing and Touching Structural Concepts. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 46, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glauch, N.; Herman, G.L. Engineering representations guide student problem-solving in statics. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 108, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glauch, N.; Choi, D.S.; Herman, G. How engineering students use domain knowledge when problem-solving using different visual representations. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 109, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, E.; Delgado, A. Change to Competence-Based Education in Structural Engineering. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2015, 141, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, E.; Delgado, A.; Vázquez-Boza, M.; Branda, L.A. Implementation of Problem-Based Learning in Structural Engineering: A Case Study. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2016, 32, 2556–2568. [Google Scholar]

- Justo, E.; Delgado, A.; Llorente-Cejudo, C.; Aguilar, R.; Cabero-Almenara, J. The effectiveness of physical and virtual manipulatives on learning and motivation in structural engineering. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 111, 813–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Lee, K. Real-time, high-fidelity linear elastostatic beam models for engineering education. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 3483–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karn, A.; Vyas, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Dwivedi, A. Elegant Computational Frameworks For the Analysis of Cantilevers and Beams. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2023, 37, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Learning statics through in-class demonstration, assignment and evaluation. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2015, 43, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjolsing, E.; Einde, L.V.D.; Todd, M. Using a Design Project to Instill Empathy in Structural Engineering Teaching Assistants. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2016, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjolsing, E.; Asce, S.M.; Van, L.; Einde, D.; Asce, M. Peer Instruction: Using Isomorphic Questions to Document Learning Gains in a Small Statics Class. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2016, 142, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, M.; Jin, R.; Wanatowski, D.; Piroozfar, P. Incorporating Woodwork Fabrication into the Integrated Teaching and Learning of Civil Engineering Students. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2018, 144, 05018007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loong, C.N.; Juan, J.D.Q.S.; Chang, C.C. Image-based structural analysis for education purposes: A proof-of-concept study. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 1200–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.; Rangel, R.; Martha, L.F. An interactive user interface for a structural analysis software using computer graphics techniques in MATLAB. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2021, 29, 1505–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCariella, J.; Pribesh, S.; Williams, M.R. An Engineering Learning Community to Promote Retention and Graduation for Community College Students. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.K.; Sonparote, R.S. Implementation of comparative visualization pedagogy for structural dynamics. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2018, 26, 1894–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, N.K. Importance of student feedback in improving mechanical engineering courses. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2019, 47, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrum, D.P. Evaluation of creative problem-solving abilities in undergraduate structural engineers through interdisciplinary problem-based learning. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 42, 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheal, A.G. Gamifying structural analysis assessments for first-year architecture engineering students. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. Advances in Engineering Education Mentoring and Motivating Project Based Learning in Dynamics. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2020, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Montfort, D.; Herman, G.L.; Brown, S.; Matusovich, H.M.; Streveler, R.A.; Adesope, O. Patterns of Student Conceptual Understanding across Engineering Content Areas. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 31, 1587–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.; State, P.; Alto, M.; Williams, C.B.; North, C.; Johri, A.; Paretti, M. Effectiveness of Adaptive Concept Maps for Promoting Conceptual Understanding: Findings from a Design-Based Case Study of a Learner-Centered Tool. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2015, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Narvydas, E.; Puodziuniene, N. Curved beam stress analysis using a binary image of the cross-section. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2020, 28, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmi, G. Load Cell Training for the Students of Experimental Stress Analysis. Exp. Tech. 2016, 40, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otarawanna, S.; Ngiamsoongnirn, K.; Malatip, A.; Eiamaram, P.; Phongthanapanich, S.; Juntasaro, E.; Kowitwarangkul, P.; Intarakumthornchai, T.; Boonmalert, P.; Bhothikhun, C. An educational software suite for comprehensive learning of Computer-Aided Engineering. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2020, 28, 1083–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallares, M.; Rodríguez, W.; Gonzalez, D. An educational computer program for matrix analysis of plane trusses in civil engineering. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2020, 15, 570–576. [Google Scholar]

- Pallares, M.; Rodríguez, W. Solving plane stress problems using EsfPlano2D educational software. DYNA 2023, 90, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paya-Zaforteza, I.; Garlock, M.E. Structural Engineering Heroes and Their Inspirational Journey. Struct. Eng. Int. 2021, 31, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, N.; Chen, A. Development of structural analysis virtual modules for iPad application. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2018, 26, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Santiago, R.; Campos, E. FEM education in undergraduate studies: Industry-informed research. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picton, O.; Losada, R.; Ferna, I.; Bustos, N.D.; Roji, E. Glued-Wood Structure Development Contests for Project Based Learning in Engineering and Architecture Degrees. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 35, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Plevris, V.; Markeset, G. Educational challenges in computer-based Finite Element Analysis and design of structures. J. Comput. Sci. 2018, 14, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polys, N.F.; Bacim, F.; Setareh, M.; Jones, B.D.; Tech, V. SAFAS: Unifying Form and Structure through Interactive 3D Simulation. Eng. Des. Graph. J. (EDGJ) 2015, 79, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, Y.; Pradipto, E.; Mustaffa, Z.; Saputra, A.; Mohammed, B.S.; Utomo, C. Enhancing Students’ Competency and Learning Experience in Structural Engineering through Collaborative Building Design Practices. Buildings 2022, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rais-Rohani, M.; Walters, A. Preliminary Assessment of the Emporium Model in a Redesigned Engineering Mechanics Course. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2014, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel, R.L.; Martha, L.F. LESM—An object-oriented MATLAB program for structural analysis of linear element models. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2019, 27, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeping, D.; Knight, D.; Grohs, J.; Case, S.W. Visualization and Analysis of Student Enrollment Patterns in Foundational Engineering Courses. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 35, 142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, B.; Rastiello, G.; Giry, C.; Riccardi, F.; Paredes, R.; Zafati, E.; Kakarla, S.; Lejouad, C. CastLab: An object-oriented finite element toolbox within the Matlab environment for educational and research purposes in computational solid mechanics. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2019, 128, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopa, A.K.; Hunashyal, A.M. Enhancing student learning in mechanics of material course through contextual learning. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2020, 33, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruta, G.; Elishakoff, I. On proper applications of Galërkin’s approach in structural mechanics courses. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2022, 50, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, K.; Jankowski, S. Learning statics by visualizing forces on the example of a physical model of a truss. Buildings 2021, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.; Barner, M.; Brown, S. Comparing Engineering Student and Practitioner Performance on the Strength of Materials Concept Inventory: Results and Implications. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2022, 148, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Kienzler, R. Teaching nonlinear mechanics: An extensive discussion of a standard example feasible for undergraduate courses. Int. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Sci. Mech. 2014, 15, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, G.; Piker, D. Interactive real-time physics: An intuitive approach to form-finding and structural analysis for design and education. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2015, 61, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setareh, M.; Jones, B.; Ma, L.; Bacim, F.; Polys, N. Application and Evaluation of Double-Layer Grid Spatial Structures for the Engineering Education of Architects. J. Archit. Eng. 2015, 21, 04015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sextos, A.G. A paperless course on structural engineering programming: Investing in educational technology in the times of the Greek financial recession. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2014, 39, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, B.; Guo, X.; Zhong, Q.; Xiong, H. Impact of Peer Learning on the Academic Performance of Civil Engineering Undergraduates: A Case Study from China. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 39, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Simonen, K. Iterating Structures: Teaching Engineering as Design. J. Archit. Eng. 2014, 20, 05014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambi, L.; Kubiak, L.; Basso, N.; Garavaglia, E. Active learning for the promotion of students’ creativity and critical thinking: An experience in structural courses for architecture. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, R.K.; Adams, R.K.; Buker, K.; Hurwitz, D.S.; Mason, H.B.; Parrish, C.E.; Scott, M.H. Response spectrum devices for active learning in earthquake engineering education. HardwareX 2018, 4, e00032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonparote, R.S.; Mahajan, S.K. An educational tool to improve understanding of structural dynamics through idealization of physical structure to analytical model. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2018, 26, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, R.P.; Mobaraki, B.; Lozano-Galant, J.A.; Sanchez-Cambronero, S.; Muñoz, F.P.; Gutierrez, J.J. New image recognition technique for intuitive understanding in class of the dynamic response of high-rise buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.S. Project Based Curriculumfor Millennial Learners @ Florida Polytechnic University. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2018, 31, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, K.M.; Brunhaver, S.R.; Sheppard, S.D. Feedback from In-class Worksheets and Discussion Improves Performance on the Statics Concept Inventory. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2014, 30, 992–999. [Google Scholar]

- Steif, P.S.; Fu, L.; Kara, L.B. Providing formative assessment to students solving multipath engineering problems with complex arrangements of interacting parts: An intelligent tutor approach. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1864–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-García, A.; Arce-Fariña, E.; Álvarez Hernández, M.; Fernández-Gavilanes, M. Teaching structural analysis theory with Jupyter Notebooks. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2021, 29, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.S. Development of educational software for beam loading analysis using pen-based user interfaces. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2014, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, J.; Mahmoudi, M.; Javidruzi, M. Practical concepts of structura for architecture students. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2017, 12, 7843–7848. [Google Scholar]

- Arciniegas, M.T.; Velez, M.I.G.; Reyes, J.C.; Valencia, D.M.; Galvis, F.A.; Ángel, C.C. The Impact of Non-Traditional Teaching on Students’ Performance and Perceptions in a Structural Engineering Course. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 37, 1044–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo, J.L.; Mucillo, V.C.; Bigarella, B.G. Integration of Excel VBA with professional software for the structural analysis and design of civil structures. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkan, Y.; Radkowski, R.; Karabulut-Ilgu, A.; Behzadan, A.H.; Chen, A. Mobile augmented reality for teaching structural analysis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 34, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, H.T.; Coskun, H.; Mertayak, C. Innovative experimental model and simulation method for structural dynamic concepts. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2016, 24, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, H.T.; Sagiroglu, S.; Deliktas, B. Experimental setup for beams with adjustable rotational stiffness: An educational perspective. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022, 30, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vackova, M.; Kancirova, M.; Kovacova, L. The importance of interdisciplinary relations of physics and statics. Commun.-Sci. Lett. Univ. žIlina 2016, 18, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venters, C.; Groen, C.; Mcnair, L.D.; Paretti, M.C. Using Writing Assignments to Improve Learning in Statics: A Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Vimonsatit, V.; Htut, T. Civil Engineering students’ response to visualisation learning experience with building information model. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2016, 21, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgin, L. Enhancing the teaching of structural dynamics using additive manufacturing. Eng. Struct. 2017, 152, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgin, L. Enhancing the teaching of linear structural analysis using additive manufacturing. Eng. Struct. 2017, 150, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgin, L.N. Enhancing the teaching of elastic buckling using additive manufacturing. Eng. Struct. 2018, 174, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgin, L.N. A shear center demonstration model using 3D-printing. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2022, 50, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Y.; Magana, A.J.; Feng, S. Investigating Students’ Explanations about Friction Concepts after Interacting with a Visuohaptic Simulation with Two Different Sequenced Approaches. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2020, 29, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Y.; Magana, A.; Will, H.; Yuksel, T.; Bryan, L.; Berger, E.; Benes, B. A learner-centered approach for designing visuohaptic simulations for conceptual understanding of truss structures. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2021, 29, 1567–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Y.; Magana, A.J. Learning Statics through Physical Manipulative Tools and Visuohaptic Simulations: The Effect of Visual and Haptic Feedback. Electronics 2023, 12, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.; Slaboch, P.E.; Jamshidi, R. Technical writing improvements through engineering lab courses. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2022, 50, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yang, G. Dual analysis of rigidity for structural analysis course. J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 39, 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, D.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, D. Research and development of website application of material mechanics based on flipped course. Int. J. Contin. Eng. Educ. Life-Long Learn. 2018, 28, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, L.; Yin, J.; Nie, Y. A comparison of flipped and traditional classroom learning: A case study in mechanical engineering. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 1876–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Yanase, K. An introduction to FE analysis with Excel-VBA. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2017, 25, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.O.Y.; Imbrie, P.K.; Reed, T.; Shryock, K.J. Identification of the Engineering Gateway Subjects in the Second-Year Engineering Common Curriculum. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 35, 232–251. [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel, T.; Walsh, Y.; Magana, A.J.; Nova, N.; Krs, V.; Ngambeki, I.; Berger, E.J.; Benes, B. Visuohaptic experiments: Exploring the effects of visual and haptic feedback on students’ learning of friction concepts. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2019, 27, 1376–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Open-Topic Project-Based Learning and Its Gender-Related Effect on Students’ Exam Performance in Engineering Mechanics. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2023, 149, 05023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. The effect of teaching reform of a mechanics of materials course on the abilities of students in engineering application and innovation. World Trans. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2014, 12, 738–742. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, W.; Bai, J.; Cheng, F. EFESTS: Educational finite element software for truss structure. Part I: Preprocess. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2014, 42, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Li, X.; Guo, G. EFESTS: Educational finite element software for truss structure. Part II: Linear static analysis. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2014, 42, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Huang, K.; Cheng, F. EFESTS: Educational finite element software for truss structure - Part 3: Geometrically nonlinear static analysis. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2017, 45, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.D.; Graveson, J. Teaching Design and Strength of Materials via Additive Manufacturing Project-Based Learning. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2022, 10, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, M.M.; Roure, F.; Ferrer, M.; Ayneto, X.; Casafont, M.; Pons, J.M.; Bonada, J. Learning in Engineering through Design, Construction, Analysis and Experimentation. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 35, 372–384. [Google Scholar]

- Ballatore, M.G.; Barpi, F.; Crocker, D.; Tabacco, A. Pedestrian bridge application in a fundamentals of structural analysis course inside an architecture bachelor program. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2021, 11, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paultre, P.; Lapointe, E.; Carbonneau, C.; Proulx, J. LAS: A programming language and development environment for learning matrix structural analysis. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2016, 24, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, C.G.; Manolis, G.D. A web-based educational software for structural dynamics. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2016, 24, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuchar, V.J.; Arteta, C.A.; Hoz, J.L.D.L.; Vieira, C. Risk-based student performance prediction model for engineering courses. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2024, 32, e22757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinç, G.M. Design-Build Projects in Architecture Education and Experimental Structures as a Pedagogical Approach. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2024, 17, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, R.; Farooq, M.U.; Riaz, M.R. A Case Study of Problem-Based Learning from a Civil Engineering Structural Analysis Course. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2024, 150, 05024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, E. Adapting the ‘study and research path’ methodology in strength of materials to online teaching and resource-constrained scenarios. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2024, 54, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijoo-Garcia, M.A.; Holstrom, M.S.; Magana, A.J.; Newell, B.A. Simulation-Based Learning and Argumentation to Promote Informed Design Decision-Making Processes within a First-Year Engineering Technology Course. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, A.; Kontar, W. The Role of Disasters and Infrastructure Failures in Engineering Education with Analysis through Machine Learning. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2024, 150, 04024003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Gomez-Merodio, M.; Requena-Garcia-Cruz, M.V. Application of MS Excel and FastTest PlugIn to automatically evaluate the students’ performance in structural engineering courses. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2024, 32, e22799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, I.; Qian, Y.; Talebi-Kalaleh, M.; Mei, Q. A Computer Vision Framework for Structural Analysis of Hand-Drawn Engineering Sketches. Sensors 2024, 24, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, O.; Canakcioglu, N.G. Teaching earthquake-resistant structural systems in architecture department: A hands-on learning experience. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2024, 67, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeChasseur, K.; Wodin-Schwartz, S.J.; Sloboda, A.; Powell, A. Validity of a self-report measure of student learning in active learning statics courses. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2024, 53, 751–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, T.K. The effect of augmented reality applied to learning process with different learning styles in structural engineering education. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 32, 3727–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouani, H.; Hassine, T. An educational MATLAB code for nonlinear isotropic/kinematic hardening model implementation. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2024, 53, 924–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsekoleng, T.K.; Mapotse, T.A.; Gumbo, M.T. The role of indigenous games in education: A technology and environmental education perspective. Diaspora Indig. Minor. Educ. 2022, 18, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.; McMullen, K.F. Mechanics Escape Room: Escaping the Monotony of Solving Problems. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2024, 150, 05024004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, B.; Guo, X.; Zhong, Q. Impact of Peer Learning on Students Academic Achievement and Personal Attributes. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 40, 400–409. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Hou, J.; Wu, Z.; Shu, P.; Liu, N.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Gu, B.; Filla, N.; Li, Y.; et al. Assessing Large Language Models in Mechanical Engineering Education: A Study on Mechanics-Focused Conceptual Understanding. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutetaki, M.E. Application and Assessment of an Experiential Deformation Approach as a Didactive Tool of Truss Structures in Architectural Engineering. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskito; Fortuna, A.; Prasetya, F.; Wulansari, R.E.; Nabawi, R.A.; Luthfi, A. Integration of Mobile Augmented Reality Applications for Engineering Mechanics Learning with Interacting 3D Objects in Engineering Education. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2024, 14, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Contributions |

|---|---|

| Statics | [36,42,44,52,55,57,59,60,67,69,70,72,73,74,77,82,84,85,93,97,98,104,106,117,130,136,148,149,159,160,166,167,168,172,175,176] |

| Mechanics of Materials | [38,39,43,46,49,51,56,58,62,63,66,71,75,76,79,87,88,89,95,102,103,110,112,116,118,119,120,122,134,135,137,138,158,164,165,169,171,177,181,182] |

| Structural Analysis | [41,45,47,48,65,68,80,81,86,90,92,99,100,101,107,108,109,114,121,124,128,131,139,140,142,143,144,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,161,162,170,183,184] |

| Finite Element Analysis | [40,53,54,83,91,125,127,133,173,178,179,180] |

| Structural Dynamics & Earthquake Engineering | [61,64,78,111,115,145,146,147,157,163,185] |

| General | [37,94,96,105,113,123,126,129,132,141,174] |

| Author | Affiliation | Contributions |

|---|---|---|

| Brown S. | Oregon State University | 8 |

| Barner M. S. | Oregon State University | 4 |

| Herman G. L. | California Polytechnic State University | 4 |

| Magana A. J. | Purdue Univerisity | 4 |

| Virgin L. | Duke University | 4 |

| Walsh Y. | Tecnológico de Costa Rica | 4 |

| Ahn B. | Iowa State University | 3 |

| Chacón R. | Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya | 3 |

| Delgado A. | Universidad de Sevilla | 3 |

| Ha O. | Oregon State University | 3 |

| Justo E. | Universidad de Sevilla | 3 |

| Monfort D. | Oregon State University | 3 |

| Johnson-Glauch N. | California Polytechnic State University | 3 |

| Zuo W. | Jilin University | 3 |

| Journal | Country | # Papers | First Author | # Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oregon State University | USA | 9 | 9 | 13 |

| Purdue University | USA | 8 | 5 | 15 |

| Iowa State University | USA | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Virginia Tech | USA | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| California Polytechnic State University | USA | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| California State University | USA | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Duke University | USA | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya | Spain | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| University of California | USA | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Country | Number of Contributions | Number of First Authors |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 73 | 64 |

| China | 15 | 13 |

| Spain | 12 | 11 |

| Brazil | 6 | 5 |

| Colombia | 6 | 6 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | 5 |

| Italy | 5 | 4 |

| Australia | 5 | 5 |

| India | 5 | 5 |

| Turkey | 4 | 3 |

| Journal | Contributions | Quartil |

|---|---|---|

| Computer Applications in Engineering Education | 28 | Q1 |

| Journal of Civil Engineering Education | 18 | Q2 |

| International Journal of Engineering Education | 18 | Q2 |

| International Journal of Mechanical Engineering | 14 | Q4 |

| Journal of Engineering Education | 9 | Q1 |

| Advances in Engineering Education | 7 | Q2 |

| European Journal of Engineering Education | 7 | Q1 |

| Journal of Engineering Education Transformations | 4 | Q4 |

| Engineering Structures | 3 | Q1 |

| Journal of Architectural Engineering | 3 | Q3 |

| Keyword | Number of Contributions |

|---|---|

| Engineering Education | 28 |

| Statics | 18 |

| Structural Analysis | 14 |

| Active Learning | 10 |

| Structural Engineering | 9 |

| Mechanics of Materials | 8 |

| Education | 7 |

| Engineering Mechanics | 7 |

| Structural Dynamics | 4 |

| Augmented Reality | 3 |

| Pedagogical Category | Number of Contributions | References |

|---|---|---|

| Use of Structural Analysis Software | 24 | [40,66,78,79,92,95,102,103,108,111,120,121,122,125,127,128,139,146,155,178,179,180,184,185] |

| Educational Laboratory Testing | 12 | [49,61,62,64,71,75,83,119,145,157,158,182] |

| Virtual and Augmented Reality | 12 | [61,76,81,82,90,91,147,156,166,167,168,175] |

| Physical Models | 12 | [68,87,96,101,104,107,126,144,162,163,164,165] |

| Person-centered learning | 12 | [45,57,60,73,93,94,110,112,115,123,132] |

| Problem-based learning | 11 | [37,47,97,98,99,100,106,113,148,181,183] |

| Programming-based learning | 10 | [41,53,54,109,131,133,141,151,173,176] |

| Virtual Resources | 9 | [36,38,58,118,124,136,140,152,161] |

| Conceptual pedagogical initiatives | 9 | [46,59,69,70,77,114,116,117,149] |

| Assessment Strategies | 8 | [42,43,44,52,85,86,137,150] |

| Collaborative Learning | 6 | [39,50,55,105,129,142] |

| Real cases-based learning | 5 | [48,80,134,143,153] |

| Flipped Learning | 5 | [65,130,154,171,172] |

| Non-traditional Theoretical Approach | 4 | [51,135,138,170] |

| Writing | 3 | [72,160,169] |

| Media support | 2 | [67,89] |

| Mathematical Resources | 2 | [74,88] |

| Authors | Year | Journal | Subject | Number of Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fogarty [76] | 2017 | Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. | Virtual and Augmented Reality | 64 |

| Francois S. [78] | 2021 | Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. | Use of Structural Analysis Software | 40 |

| Atadero et al. [42] | 2015 | J. Eng. Educ | Assessment Strategies | 37 |

| Ha O. [84] | 2016 | Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. | Spatial Ability | 36 |

| Senatore G. [139] | 2015 | CAD. Comput. Aided Des. | Use of Structural Analysis Software | 36 |

| McCrum DP. [113] | 2017 | Eur. J. Eng. Educ. | Problem-based learning | 36 |

| Hashim et al. [88] | 2021 | Indonesian Journal of Science and Tech | Mathematical Resources | 34 |

| Justo E. [99] | 2015 | Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. | Problem-based learning | 26 |

| Hu [90] | 2021 | Adv. Eng. Informatics | Virtual and Augmented Reality | 26 |

| Yan J. [172] | 2018 | Int. J. Eng. Educ. | Flipped Learning | 25 |

| Journal | Number of Citations by Country |

|---|---|

| USA | 182 |

| Spain | 69 |

| United Kingdom | 66 |

| Italy | 44 |

| Belgium | 42 |

| Malaysia | 39 |

| Korea | 37 |

| Australia | 26 |

| Mexico | 22 |

| Greece | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Villalba-Morales, J.D.; Jerez, S.; Parra, R.; Obando, J.C.; Guzmán, A.; Benjumea, J.M.; Arroyo, O.; Cundumi, O. Emerging Trends in Structural Mechanics Education: A Bibliometric Approach from the Perspective of Colombian Professors. Buildings 2026, 16, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010219

Villalba-Morales JD, Jerez S, Parra R, Obando JC, Guzmán A, Benjumea JM, Arroyo O, Cundumi O. Emerging Trends in Structural Mechanics Education: A Bibliometric Approach from the Perspective of Colombian Professors. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010219

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillalba-Morales, Jesús D., Sandra Jerez, Ricardo Parra, Juan C. Obando, Andrés Guzmán, José M. Benjumea, Orlando Arroyo, and Orlando Cundumi. 2026. "Emerging Trends in Structural Mechanics Education: A Bibliometric Approach from the Perspective of Colombian Professors" Buildings 16, no. 1: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010219

APA StyleVillalba-Morales, J. D., Jerez, S., Parra, R., Obando, J. C., Guzmán, A., Benjumea, J. M., Arroyo, O., & Cundumi, O. (2026). Emerging Trends in Structural Mechanics Education: A Bibliometric Approach from the Perspective of Colombian Professors. Buildings, 16(1), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010219