The Economic Benefit Evaluation of Elevator Retrofitting: An Empirical Analysis of Second-Hand Housing Price Premiums in Hangzhou’s Older Residential Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Gaps in the Economic Effects of Elevator Retrofitting

1.2. Research Gaps in Benefit-Sharing and Cost Allocation in Elevator Retrofitting

1.3. Feasibility Analysis of Methods for Evaluating the Economic Effects of Elevator Retrofitting

2. Theoretical Mechanism and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Effect of Post-Retrofit Elevators on Overall Housing Value Premium

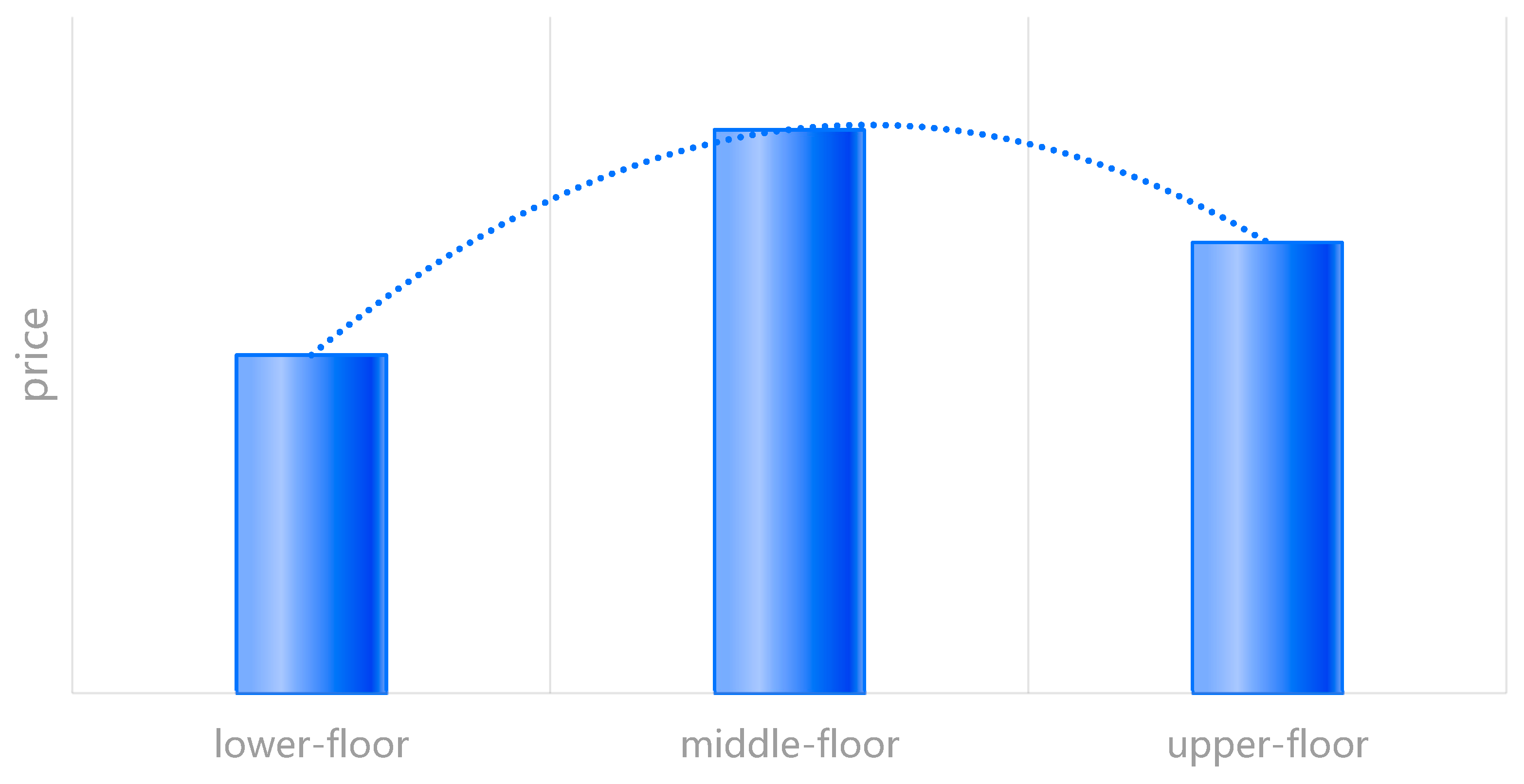

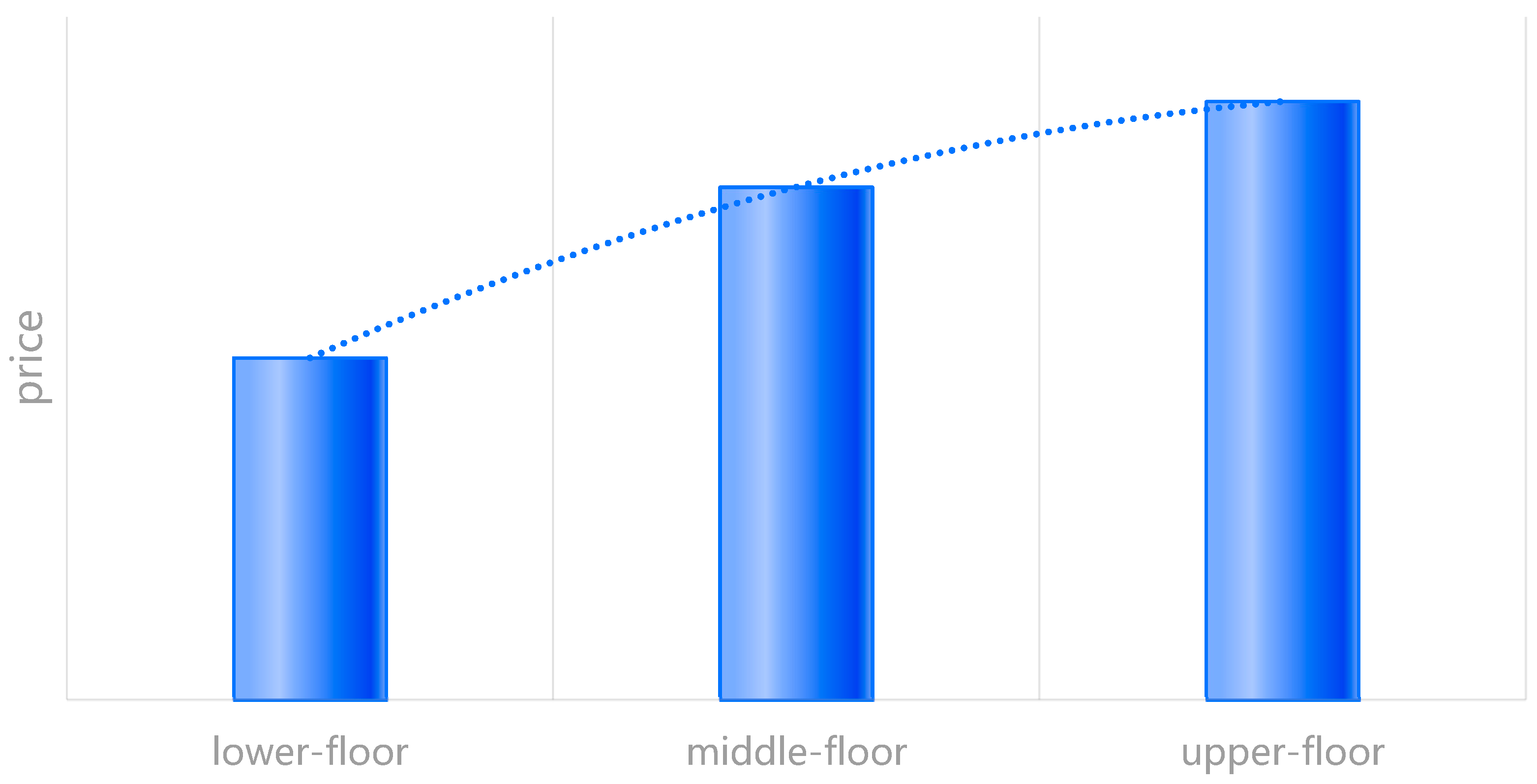

2.2. Heterogeneous Value Appreciation Across Floor Levels Post-Elevator Retrofitting

2.3. Heterogeneous Appreciation Magnitude Across Floor Levels Post-Elevator Retrofitting

3. Analysis of the Price Premium Effects of Elevator Retrofitting in Older Residential Compounds

3.1. Model Construction

3.2. Variable Selection and Data Sources

3.2.1. Variable Selection

3.2.2. Data Sources

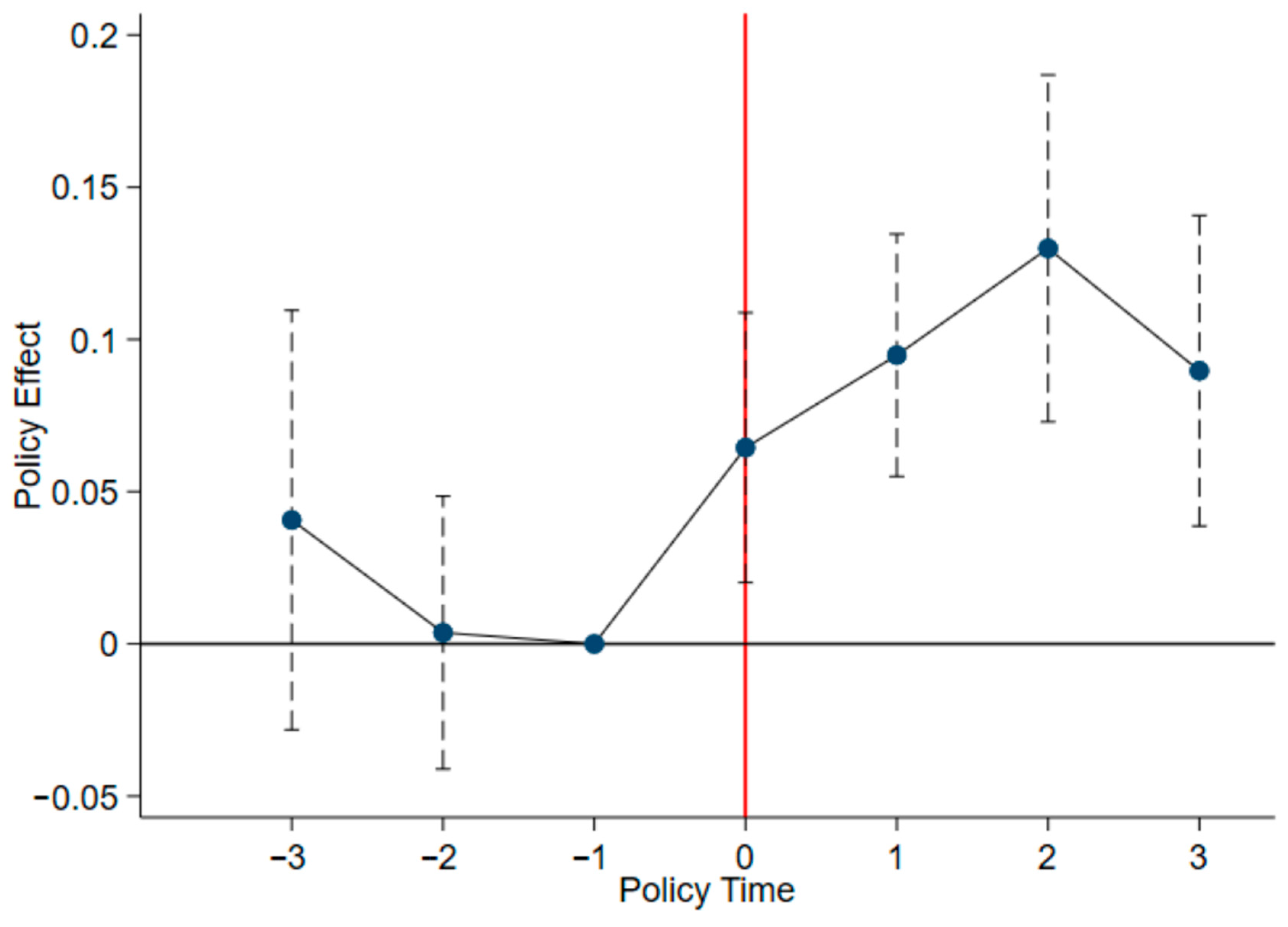

3.2.3. Parallel Trends Assumption Test

3.3. Results and Analysis

3.3.1. Examination of the Overall Premium Effect on Housing After Elevator Retrofitting

3.3.2. Robustness Test of the Overall Premium Effect on Housing Following Elevator Retrofitting

- (1)

- Interactive Fixed Effects

- (2)

- Substitution of Sample Scope

- (3)

- Controlling for Additional Covariates

3.3.3. Heterogeneity Test of Housing Appreciation in Elevator Retrofitting

- (1)

- Heterogeneity Test in Housing Price Appreciation Across Different Floor Levels

- (2)

- Heterogeneity Test of Appreciation Extent on Different Floors

3.4. Mechanism Analysis

- (1)

- Capitalisation Mechanism of Public Good Improvement

- (2)

- Mechanism of Vertical Location Value Reconfiguration

- (3)

- Mechanism of Demand Preference Shift and Divergence in Willingness-to-Pay

4. Economic Benefit Evaluation of Elevator Retrofitting in Older Residential Compounds

4.1. Evaluation Methodology

4.2. Economic Benefit Evaluation

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

- (1)

- Analytical Framework and Parameter Specification

- (2)

- Sensitivity Analysis Results

- (3)

- Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gan, C.; Chen, M.Y.; Rowe, P. Beijing’s Selected Older Neighborhoods Measurement from the Perspective of Aging. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, L.; Jin, J. The Spatio-Temporal Pattern and Spatial Effect of Installation of Lifts in Old Residential Buildings: Evidence from Hangzhou in China. Land 2022, 11, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.P. Sacrifice and Sorting in Clubs. Forum Soc. Econ. 2020, 49, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.M.; Ryan, R.L. The influence of policy design on club good provisions: A study of for-profit shopping mall roof gardens in Shanghai. Land Use Policy 2022, 121, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, M.; Weichenrieder, A.J. Public goods, club goods, and the measurement of crowding. J. Urban Econ. 1999, 46, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Tang, C. The Rationales of the Supply of Communal Public Goods—A Case Study of Installing New Elevators in the Long-Established Condominium Communities. J. Chin. Public Adm. 2019, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.W.; Yang, Y.L. Construction of Neighborhood Governance Community Under the Perspective of Spatial Production: Taking the Installing of New Elevators in Old Residential Communities as a Lens. J. Theory Reform 2024, 126–138+166-167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysinghe, T.; Gu, J.Y. Lifetime Income and Housing Affordability in Singapore. Urban Stud. 2021, 48, 1875–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.L.; Tian, G.J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, T. Addressing the macroeconomic and hedonic determinants of housing prices in Beijing Metropolitan Area, China. Habitat Int. 2021, 113, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.D. Effects of Access Time via Travel Modes to Urban Service Facilities on Housing Prices: Evidence from Seoul. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 05025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinkovic, S.; Dzunic, M.; Marjanovic, I. Determinants of housing prices: Serbian Cities’ perspective. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 1601–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Ren, H.; Xiang, W.M.; Wu, K.; Cai, W.G. Nonlinear Influence of Public Services on Urban Housing Prices: A Case Study of China. Land 2021, 10, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.H.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Zhang, S.J.; Wang, S.Q.; Chen, Y.Y. The Spatial Effect of Accessibility to Public Service Facilities on Housing Prices: Highlighting the Housing Equity. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Wu, L.F. Appeals Promote Publicity: The Rationale of Participating in Community Governance-based on the Field Research of Installing New Elevators in the Long-Established Condominium Communities of City. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2019, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.X.; Wang, X.; Song, J.B. Research on the Cooperation Model of Elevator Retrofitting Projects in Old Neighborhoods Based on PPP Model. J. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 32, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E. Club Goods and Local Government. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2011, 77, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Jiao, J.; Farahi, A. Disparities in affecting factors of housing price: A machine learning approach to the effects of housing status, public transit, and density factors on single-family housing price. Cities 2023, 140, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesselmeyer, E.; Seah, K.Y.S.; Kwok, J.C.Y. The effect of localised density on housing prices in Singapore. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 68, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, H.R.A.; Ommeren, J. Place-Based Policies and the Housing Market. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2019, 101, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Chen, L.Y.; Zhao, P.J. The impact of metro services on housing prices: A case study from Beijing. Transportation 2019, 46, 1291–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.S.; Sun, G.B.; Li, L. New metro and housing price and rent premiums: A natural experiment in China. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 1371–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.A.; Zhang, S.M.; Guan, M.; Cao, J.F.; Zhang, B.L. An Assessment of the Accessibility of Multiple Public Service Facilities and Its Correlation with Housing Prices Using an Improved 2SFCA Method-A Case Study of Jinan City, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.W.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, Y.H. Investigating the Influence of Age-Friendly Community Infrastructure Facilities on the Health of the Elderly in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.X.; Chen, H. The Renovation of Aging Residential Communities: Integrationg Emotions and Coordinating Interasts—A Case of Elevator Installation in Hemu New Village. Adm. Trib. 2023, 30, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.P.; Hu, X.P. Research on the Impact of Public Risk Perception on Behavioral Tendencies in Urban Renewal—A Case Study of Elevator Installation Projects in Old Residential Areas in Beijing. Urban Probl. 2022, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M. Public Service Co-production and Its Mechanisms Driven by Grassroots: A Case Study of PPP Regeneration of Micro-Infrastructure in Y Sub-district in S City. Chin. Public Adm. 2022, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; You, Y.Y. Spatial Variation Characteristics of Housing Conditions in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.R. construction and application of elevator cost model in existing multi-storey residential buildings. Constr. Econ. 2014, 41, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.Q. Theoretical Analysis of the Cost-Sharing and Compensation Measures for Installing Elevators in Existing Residential Buildings. J. Urban Probl. 2014, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Li, X.M.; Mao, Y.M. The Premium Effect of ‘Electric Zone Housing’: Evidence from Micro-level Housing Transaction Data. J. World Econ. 2024, 47, 219–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Chen, A.P. Urban Renewal’s Premium: Evidence from a Quasi—Natural Experiment of Urban Village Redevelopment. China Econ. Stud. 2021, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Zhang, L. The dynamic Impact of New Subway Stations on Housing Prices in Hangzhou Under the Background of Subway Expansion. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Sci. Ed.) 2025, 52, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; He, H. Evaluating the accessibility and equity of urban health resources based on multi-source big data in high-density city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 100, 105049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.X.; Ma, J.; Tao, S. Examining the nonlinear relationship between neighborhood environment and residents’ health. Cities 2024, 152, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvenniemi, H.; Huovila, A.; Pinto-Sepp, I. What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities? Cities 2017, 60, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, I.; Delmelle, E.C. Impact of new rail transit stations on neighborhood destination choices and income segregation. Cities 2020, 102, 102737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.K.; Cheung, K.S. Co-Living at Its Best-An Empirical Study of Economies of Scale, Building Age, and Amenities of Housing Estates in Hong Kong. Buildings 2023, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wei, Y.D.; Wu, J. Amenity Effects of Urban Facilities on Housing Prices in China: Accessibility, Scarcity, And Urban Spaces. Cities 2020, 96, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, B.; Li, X. Rising Housing Prices and Marriage Delays in China: Evidence from the Urban Land Transaction Policy. Cities 2023, 135, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.L.; Cai, Y.Y. Do rising housing prices restrict urban innovation vitality? Evidence from 288 cities in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 72, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonn, J.W.; Chen, K.W.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. A Top-down Creation of a Cluster for Urban Regeneration: The Case of OCT Loft, ShenZhen. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. How Long to Pareto Efficiency. Game Theory 2024, 43, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicket, M.; Vanner, R. Designing Policy Mixes for Resource Efficiency: The role of Public Acceptability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Yu, J.H.; Zhang, W.Z. Spatial Impact of Airport Facilities’ NIMBY Effect on Residential Price: A Case Study of Beijing Capital International Airport. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 1993–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.F.; He, Q.Y.; Ouyang, X. The Capitalization Effect of Natural Amenities on Housing Price in Urban China: New Evidence From Changsha. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 833831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.Z.; Xiao, Y.; Hui, E.C. Quantile Effect of Educational Facilities on Housing Price: Do Homebuyers of High Er-Priced Housing Pay More for Educational Resources? Cities 2019, 90, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.C.; Zhao, P.X.; Xiao, Y. Walking Accessibility to the Bus Stop: Does it Affect Residential Rents? The Case of Jinan, China. Land 2022, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Description |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Housing Price (Y) | Logarithm of transaction price per square meter (yuan/m2) for second-hand residences |

| Building Characteristics | Floor Level | Low floor (1st–2nd floor) = 1; Middle floor (3rd–4th floor) = 2; High floor (5th–6th floor) = 3 |

| Housing Area | Floor area of residence (m2), transformed using. natural logarithm | |

| Orientation | South-facing = 1; Non-south-facing = 0 | |

| Renovation Status | Simple renovation = 1; Medium renovation = 2; High-quality renovation = 3 | |

| Housing Type | Relocation housing = 0; Private ownership = 1; Reform housing = 2; Commercial housing = 3 | |

| Bedrooms | Number of bedrooms in the residence | |

| Living Rooms | Number of living rooms in the residence | |

| Bathrooms | Number of bathrooms in the residence | |

| Housing Age | Number of years since the residence was built | |

| Location Characteristics | Shopping Mall | Mall within 500 m = 1; Mall within 1000 m = 2; Mall within 1500 m = 3 |

| Subway Station | Subway station within 500 m = 1; No subway station within 500 m = 0 | |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | School | Scored 1 to 5 based on school tier |

| Hospital | Hospital within 500 m = 1; Hospital within 1000 m = 2; Hospital within 1500 m = 3 |

| Variable | Full Sample | Treatment Group (Treat = 1) | Control Group (Treat = 0) | Between-Group Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Sd | Mean | Sd | Mean | Sd | (Mean Diff) | |

| Log(Housing Price) | 10.8111 | 0.35 | 10.9247 | 0.32 | 10.7649 | 0.36 | 0.16 |

| Floor Level | 2.0648 | 0.78 | 2.0079 | 0.79 | 2.088 | 0.78 | −0.08 |

| Housing Area | 74.0442 | 32.53 | 76.4091 | 26.58 | 73.0831 | 34.62 | 3.33 |

| Orientation | 0.9204 | 0.27 | 0.9449 | 0.23 | 0.9104 | 0.29 | 0.03 |

| Renovation Status | 2.2582 | 0.56 | 2.1299 | 0.64 | 2.3104 | 0.51 | −0.18 *** |

| Housing Type | 2.8532 | 0.39 | 2.8425 | 0.44 | 2.8576 | 0.37 | −0.02 |

| Bedrooms | 2.3094 | 0.86 | 2.4252 | 0.74 | 2.2624 | 0.9 | 0.16 |

| Living Rooms | 1.2856 | 0.5 | 1.3819 | 0.52 | 1.2464 | 0.49 | 0.14 |

| Bathrooms | 1.182 | 0.47 | 1.1575 | 0.42 | 1.192 | 0.5 | −0.03 |

| Housing Age | 26.8851 | 5.35 | 27.2165 | 6.55 | 26.7504 | 4.77 | 0.47 |

| Shopping Mall | 1.8089 | 0.74 | 1.9646 | 0.75 | 1.7456 | 0.73 | 0.22 |

| Subway Station | 0.4391 | 0.5 | 0.2835 | 0.45 | 0.5024 | 0.5 | −0.22 |

| School | 1.9079 | 1.2 | 1.8701 | 1.28 | 1.9232 | 1.17 | −0.05 |

| Hospital | 2.1843 | 0.8 | 1.874 | 0.68 | 2.3104 | 0.8 | −0.44 |

| Housing Prices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 0.102 *** | 0.0592 *** | 0.0553 *** | 0.0553 *** | |

| (0.0145) | (0.0169) | (0.0163) | (0.0163) | |

| Floor Level = 2 | 0.0303 *** | 0.0303 *** | ||

| (0.00946) | (0.00946) | |||

| Floor Level = 3 | −0.00565 | −0.00565 | ||

| (0.00968) | (0.00968) | |||

| Housing Area | −0.142 *** | −0.142 *** | ||

| (0.0271) | (0.0271) | |||

| Orientation = 1 | 0.0366 ** | 0.0366 ** | ||

| (0.0147) | (0.0147) | |||

| Renovation Status = 2 | 0.0300 | 0.0300 | ||

| (0.0243) | (0.0243) | |||

| Renovation Status = 3 | 0.0441 * | 0.0441 * | ||

| (0.0248) | (0.0248) | |||

| Housing Type = 1 | 0.0508 | 0.0508 | ||

| (0.0862) | (0.0862) | |||

| Housing Type = 2 | −0.0696 | −0.0696 | ||

| (0.0656) | (0.0656) | |||

| Housing Type = 3 | −0.0227 | −0.0227 | ||

| (0.0637) | (0.0637) | |||

| Bedrooms | 0.0178 * | 0.0178 * | ||

| (0.00923) | (0.00923) | |||

| Living Rooms | 0.0148 | 0.0148 | ||

| (0.0107) | (0.0107) | |||

| Bathrooms | 0.00233 | 0.00233 | ||

| (0.0113) | (0.0113) | |||

| Housing Age | −0.00434 | −0.00434 | ||

| (0.00703) | (0.00703) | |||

| School = 2 | 0.976 *** | |||

| (0.126) | ||||

| School = 3 | 0.0678 ** | |||

| (0.0340) | ||||

| School = 4 | 0.253 *** | |||

| (0.0663) | ||||

| School = 5 | 0.382 *** | |||

| (0.0822) | ||||

| Hospital = 2 | 0.650 *** | |||

| (0.117) | ||||

| Hospital = 3 | 0.684 *** | |||

| (0.0497) | ||||

| Shopping Mall = 2 | 0.0909 | |||

| (0.0768) | ||||

| Shopping Mall = 3 | −1.110 *** | |||

| (0.0649) | ||||

| Subway Station | 0.574 *** | |||

| (0.0616) | ||||

| Compound Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time Fixed Effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 879 | 879 | 879 | 879 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.907 | 0.913 | 0.922 | 0.922 |

| Housing Price | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 0.0592 *** | 0.0553 *** | 0.0553 *** | 0.0553 *** | |

| (0.0168) | (0.0163) | (0.0163) | (0.0163) | |

| Building Characteristics | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Neighbourhood Characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Location Characteristics | No | No | No | Yes |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| N | 879 | 879 | 879 | 879 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.9115 | 0.9129 | 0.9219 | 0.9219 |

| Housing Price | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

| 0.0604 *** | 0.0637 *** | |

| (0.0168) | (0.0199) | |

| Building Characteristics | Yes | Yes |

| Neighbourhood Characteristics | Yes | Yes |

| Location Characteristics | Yes | Yes |

| Yes | Yes | |

| N | 0.9278 | 0.9276 |

| Adjusted R2 | 759 | 512 |

| Housing Price | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 0.0747 *** | 0.0728 *** | 0.0728 *** | 0.0728 *** | |

| (0.0186) | (0.0163) | (0.0163) | (0.0163) | |

| Building Characteristics | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Neighbourhood Characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Location Characteristics | No | No | No | Yes |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| N | 615 | 615 | 615 | 615 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.9237 | 0.9129 | 0.9219 | 0.9219 |

| Housing Price | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Low Floor | Middle Floor | High Floor |

| 0.0159 ** | 0.0458 *** | 0.081 *** | |

| (0.0295) | (0.0254) | (0.0240) | |

| Building Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Neighbourhood Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Location Characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Street Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 243 | 336 | 300 |

| R-squared | 0.950 | 0.920 | 0.947 |

| Housing Price | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 0.0425 * | −0.00445 | −0.0166 | −0.0166 | |

| (0.0227) | (0.0241) | (0.0233) | (0.0233) | |

| 0.0779 *** | 0.0815 *** | 0.0898 *** | 0.0898 *** | |

| (0.0275) | (0.0272) | (0.0264) | (0.0264) | |

| 0.0894 *** | 0.0953 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.114 *** | |

| (0.0286) | (0.0282) | (0.0272) | (0.0272) | |

| Building Characteristics | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Neighbourhood Characteristics | No | No | No | Yes |

| Location Characteristics | No | No | No | Yes |

| Street Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time Fixed Effects | NO | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-squared | 0.909 | 0.916 | 0.924 | 0.924 |

| N | 879 | 879 | 879 | 879 |

| Output | O1 | Housing Value Appreciation |

| O2 | Government Subsidy for Retrofitting | |

| Input | I1 | Elevator Construction Cost |

| I2 | Elevator Maintenance Fees | |

| I3 | Elevator Annual Inspection Fees | |

| I4 | Elevator Electricity Expenses | |

| I5 | Compensation for Lower-Floor Residents |

| Output Indicator | Cost | Period | Discount Rate | Total Cost During the Usage Period (Present Value, Unit: Yuan) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Elevator Construction Cost | 700,000 yuan | One-time | - | 700,000 |

| I2 | Elevator Maintenance Fee | 3600 yuan/year | 12 years | 2.30% | 38,238.86 |

| I3 | Elevator Annual Inspection Fee | 1000 yuan/year | 15 years | 2.30% | 12,854.52 |

| I4 | Elevator Electricity Fee | 2400 yuan/year | 15years | 2.30% | 30,850.84 |

| I5 | Compensation for Lower-floor Residents | 200,000 yuan or a free ride | One-time | - | - |

| Total Cost | 781,944.22 | ||||

| Floor Level | Elevator Retrofit Contribution Ratio | Residential Elevator Installation Cost (in Ten Thousand Yuan) | Elevator Operation Cost (in Ten Thousand Yuan) | Total Cost (in Ten Thousand Yuan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd | 10% | 3.5 | 1.02 | 4.52 |

| 4th | 20% | 7 | 1.02 | 8.02 |

| 5th | 30% | 10.5 | 1.02 | 11.02 |

| 6th | 40% | 14 | 1.02 | 15.02 |

| Floor Level | Average Area (sq. m) | Control Group Housing Price (Yuan/sq. m) | Premium Rate | Premium (in Ten Thousand Yuan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd | 56.77 | 52,003.24 | 4.58% | 13.52 |

| 4th | 60.96 | 52,003.24 | 4.58% | 14.52 |

| 5th | 66.46 | 45,581.41 | 8.10% | 24.54 |

| 6th | 73.38 | 45,581.41 | 8.10% | 27.09 |

| Variable Parameter | Change Scenario | Net Present Value (NPV) | Benefit–Cost Ratio (B/C) | Economic Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Scenario | 169.13 | 3.16 | Highly Feasible | |

| Discount Rate | 1.50% | 185.42 | 3.42 | Highly Feasible |

| 3.50% | 154.21 | 2.91 | Highly Feasible | |

| Overall Premium Rate | −50% (2.57%) | 78.5 | 2 | Feasible |

| Overall Premium Rate | −20% (4.42%) | 132.75 | 2.58 | Feasible |

| +20% (6.64%) | 205.51 | 3.74 | Highly Feasible | |

| Elevator Service Life | 10 years | 145.89 | 2.81 | Feasible |

| 20 years | 192.37 | 3.51 | Highly Feasible | |

| Construction Cost | −15% (59.5) | 183.63 | 3.42 | Highly Feasible |

| +15% (80.5) | 154.63 | 2.9 | Highly Feasible |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dai, X.; Yu, X.; Ma, L.; Zheng, P. The Economic Benefit Evaluation of Elevator Retrofitting: An Empirical Analysis of Second-Hand Housing Price Premiums in Hangzhou’s Older Residential Compounds. Buildings 2026, 16, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010220

Dai X, Yu X, Ma L, Zheng P. The Economic Benefit Evaluation of Elevator Retrofitting: An Empirical Analysis of Second-Hand Housing Price Premiums in Hangzhou’s Older Residential Compounds. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010220

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Xinjun, Xiaofen Yu, Lindong Ma, and Pengju Zheng. 2026. "The Economic Benefit Evaluation of Elevator Retrofitting: An Empirical Analysis of Second-Hand Housing Price Premiums in Hangzhou’s Older Residential Compounds" Buildings 16, no. 1: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010220

APA StyleDai, X., Yu, X., Ma, L., & Zheng, P. (2026). The Economic Benefit Evaluation of Elevator Retrofitting: An Empirical Analysis of Second-Hand Housing Price Premiums in Hangzhou’s Older Residential Compounds. Buildings, 16(1), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010220