Emerging Resident Concerns as Signals of a Paradigm Shift in the Spatial Infrastructure for Integrated Community Care: Focusing on Yeonpyeong Island, a Medically Isolated Declining Region of Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Significance of the Study

1.3. Originality and Contribution

1.3.1. Theoretical Expansion: From Individual Adaptation to Community-Level Dynamics

1.3.2. Methodological Positioning: A Primary Quantitative Study with Contextual Qualitative Validation

1.3.3. Policy and Practical Contribution: Environmental Intervention as Preventive Infrastructure

1.3.4. Aim of This Study

1.4. Key Concept Definitions

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Aging Society and Regional Environmental Imbalance

2.2. Expansion of Environmental Press and Environmental Intervention

2.3. Push–Pull Dynamics in Community Transformation

2.4. Decayed Island as a Living Lab for Theoretical Exploration and Application

2.4.1. Global Justification

2.4.2. Islands as Isolated Yet Strategic Regions

2.4.3. Theoretical Expansion and Implications

2.5. Life-Space and Walk Appeal: Integrating Mobility, Experience, and Control

2.6. Proposed Integrative Model: Environmental Intervention-Based Care Infrastructure (EIICI)

- Environmental Press and Coping Response—Environmental strain functions as a push factor that, when institutionally recognized, can be transformed into adaptive community responses [17].

- Spatial–Psychological Dynamics—Through push–pull interactions, residents engage in psychological mobility, imagining new spatial and social possibilities such as community-based housing, accessible facilities, or shared care systems [23].

- Preventive Environmental Intervention—Care shifts from reactive treatment to proactive prevention, echoing Antonovsky’s [40] Salutogenic Model of Health, wherein environmental structure itself becomes a source of resilience, safety, and inclusion.

2.7. Empirical Foundations in Yeonpyeong Island

2.7.1. Bridging the Theoretical Framework to the Yeonpyeong Context

2.7.2. Residential Suitability and Health Implications

2.7.3. Integrative Implications and Position of the Current Study

3. Research Methods

3.1. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework for Research Design

3.2. Nature of the Research Design

3.2.1. Philosophical Foundation

3.2.2. Characteristics of the Research Approach

3.2.3. Logical Structure of the Research Design

3.3. Situated Characteristis of Study Area

3.3.1. Study Area and Characteristics

3.3.2. Wartime Damage, Governmental Reconstruction, and Residential Deterioration

3.4. Data Collection Process

3.4.1. Primary Quantitative Study with Contextual Qualitative Validation

3.4.2. Ensuring Response Reliability

3.4.3. Fieldwork Procedure

3.4.4. Representativeness and Sampling Validity

3.4.5. Data Processing and Analytical Framework

3.5. Analytical Method Based on the Creative Research Process

3.6. Statistical Analysis of Housing-Related Needs

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Residential Environment Characteristics of Elderly Households

4.1.1. Characteristics of Elderly Residents

4.1.2. Physical Characteristics of Residential Dwellings

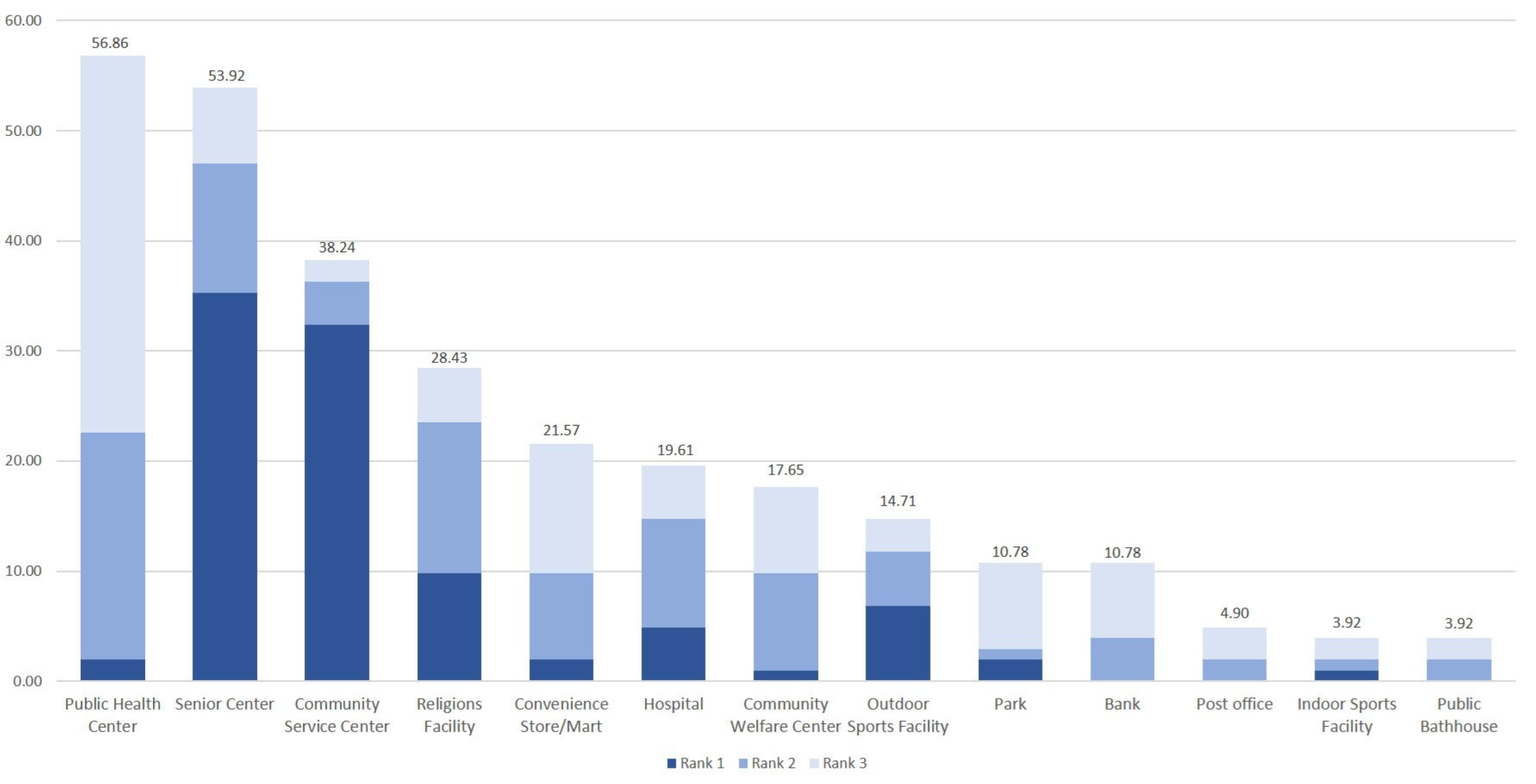

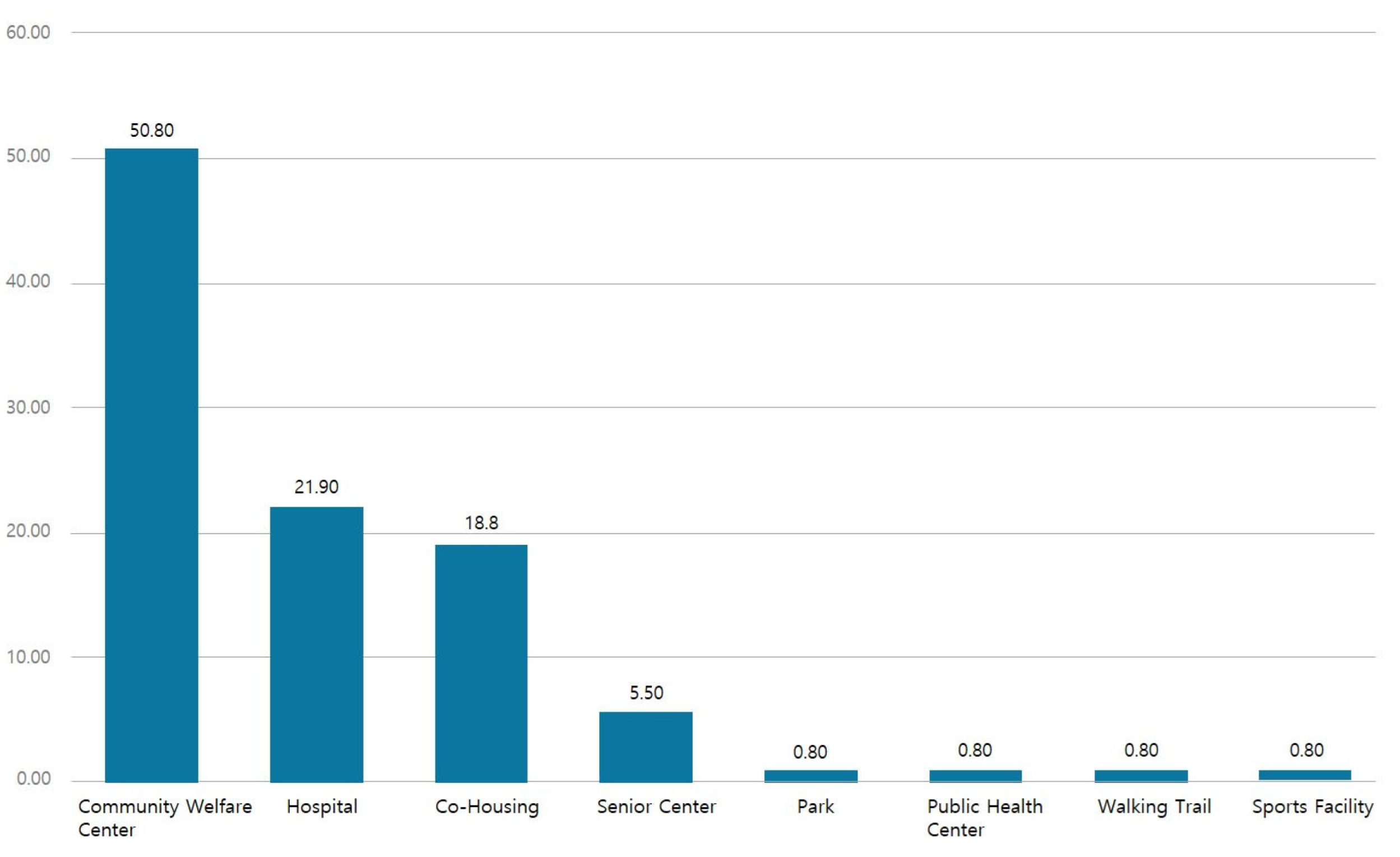

4.1.3. Community Facility Utilization Patterns

- (1)

- Awareness and frequency of use.

- (2)

- Perceived importance.

- (3)

- Required facilities for an extended old-age period.

- (4)

- Integrated interpretation.

4.1.4. Integrated Assessment of the Residential Environment of Older Households

4.2. Emerging Resident Concerns as Signals for Spatial Transformation

4.2.1. Emerging Concerns: Early Signals of Residential Adaptation Needs

- perceived changes in health and daily function,

- perceived safety risks and usefulness of assistive features, and

- perceived necessity and benefits of home modification.

- (1)

- Recognition of age-related change and vulnerability

- (2)

- Experiential understanding of environmental interventions

- (3)

- Attitudinal openness to housing improvement

- (4)

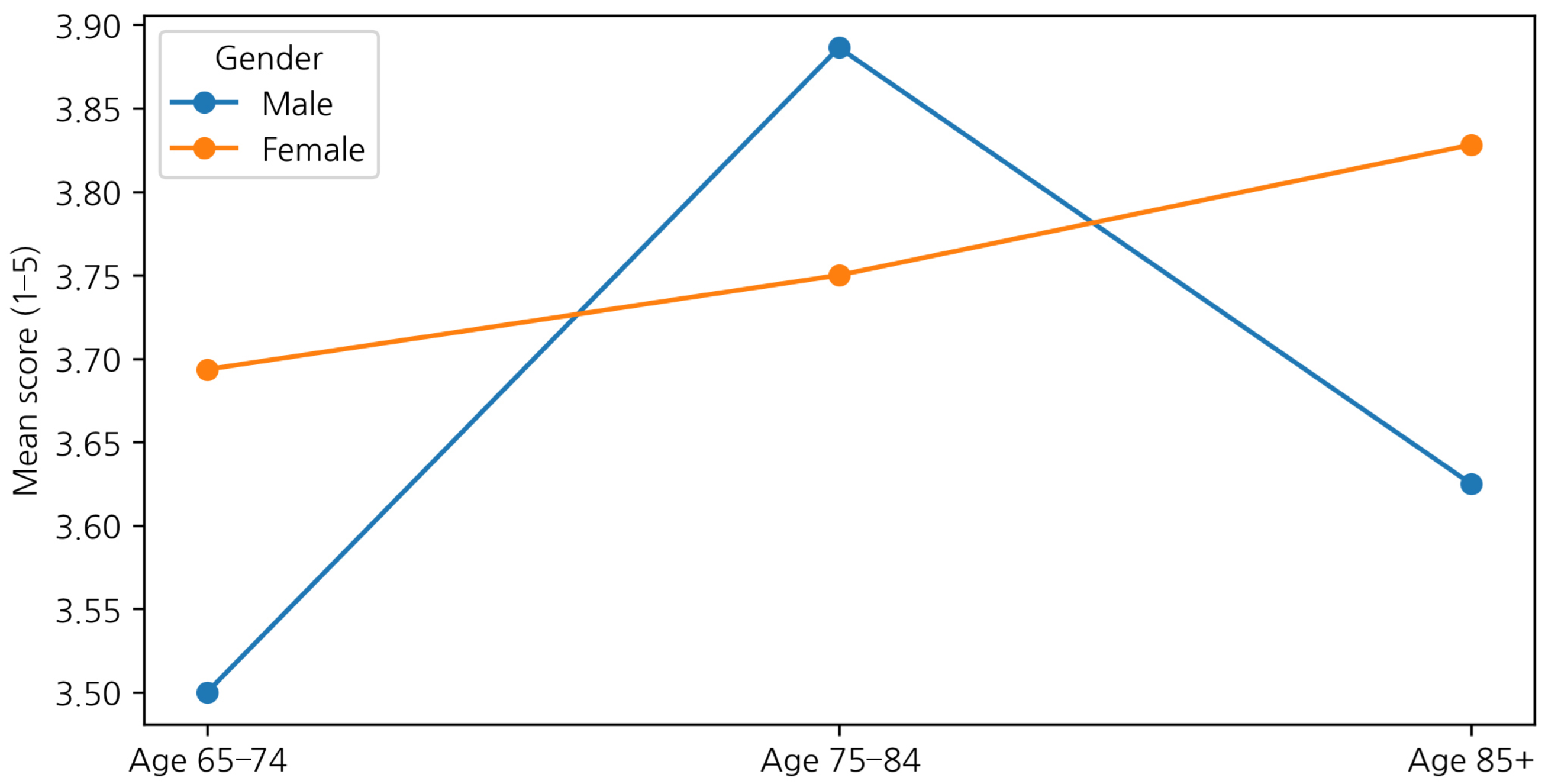

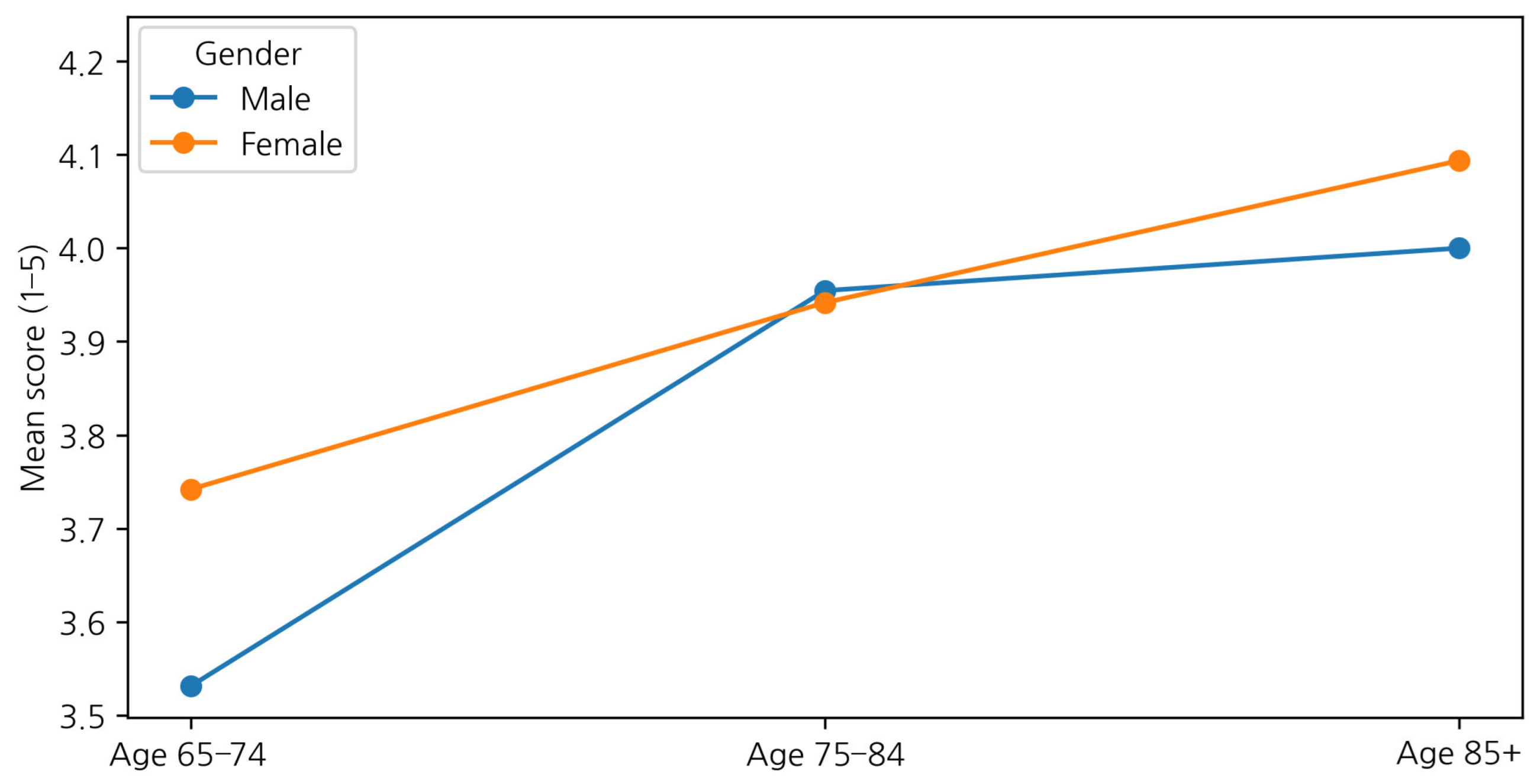

- Age- and Gender-Related Differences in Home Improvement Needs

4.2.2. Perceived Acceptability of Alternative Co-Housing Models

- (1)

- Functional strain and declining residential fit

- (2)

- Emotional–relational needs and desire for social reassurance

- (3)

- Openness to co-housing models that preserve autonomy

- (4)

- Age- and Gender-Related Differences in Alternative Housing Needs

4.2.3. Perceived Needs for Community Support Spaces

- (1)

- Environmental adequacy and accessibility deficitsItems 1–3 showed strong dissatisfaction with the adequacy and accessibility of leisure spaces and routes to meeting places, with negative responses dominating and mean levels remaining low (e.g., M = 1.92 for leisure-space adequacy). These results indicate structural constraints in proximity, accessible circulation, and continuity of use as mobility declines.

- (2)

- Programmatic and service integration needsItems 4–6 showed near-universal endorsement of consolidated, multi-functional hubs providing diverse services and programs, including spaces usable across age groups. This pattern reflects strong preference for integrated community environments that support everyday stability and participation.

- (3)

- Environmental and climatic requirements for new facilitiesItems 7–10 also received overwhelmingly positive responses, emphasizing mobility-safe access, usability during extreme weather, and expectations that well-designed community spaces support autonomous living. These responses indicate explicit criteria for future facilities in an aging and climate-vulnerable island context.

4.2.4. Integrated Interpretation of Emerging Concerns Across Housing, Co-Housing, and Community Spaces

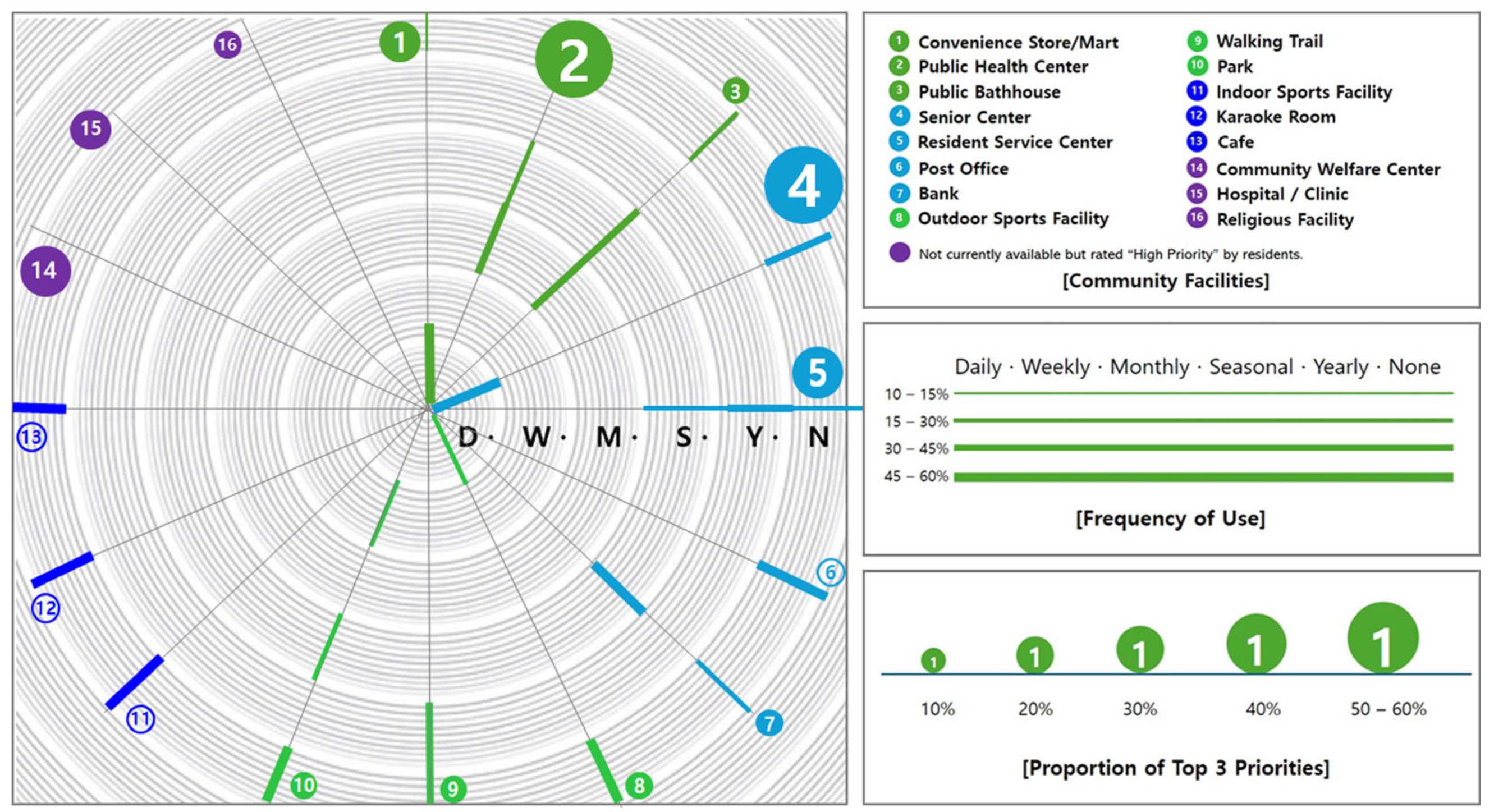

5. Discussion

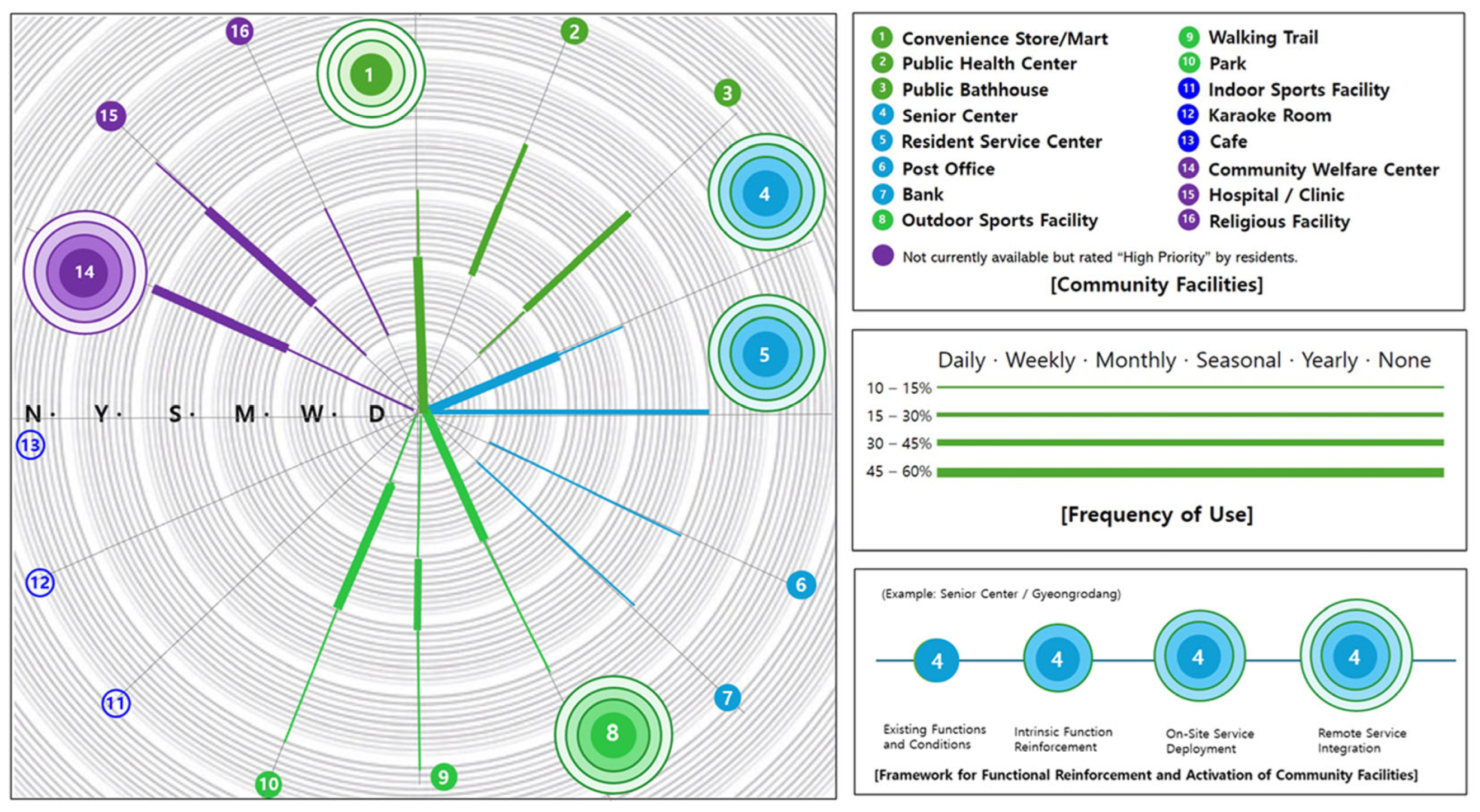

5.1. A Directional Framework for Functional Integration of Community Facilities

- (1)

- Framework logic and visualization

- (2)

- Direction of integration: from dispersed points to multi-functional hubs

- (3)

- Senior centers (Gyeongrodang) as a practical testbed for staged activation

- (4)

- Integration pathways for other core facilities

- Local mart (Facility #1) as a daily-life support node: As a stable weekly routine destination, the mart can incorporate light health-linked functions (nutrition guidance, simple wellness information, coordination of meal-related support) without requiring major institutional restructuring.

- Resident/administrative support center (Facility #5) as a multi-service civic node: Beyond administrative tasks, the center can serve as a coordination point for welfare navigation, program scheduling, information access, and linkage to visiting or remote services, reducing informational isolation.

- Outdoor sports facility (Facility #8) as an active-aging and rehabilitation node: With modest upgrades (weather protection, seating, safer walking loops, senior-friendly equipment), this node can support routine mobility maintenance and psychosocial restoration.

- Community welfare center (Facility #14) as a future integrated-care hub: Although currently absent, the welfare center represents the most strongly articulated future hub that can coordinate island-wide program delivery, dispatch services to smaller nodes (including senior centers) and integrate welfare–health–leisure functions in one place.

- (5)

- Synthesis: toward a web-shaped service ecosystem.

5.2. Theoretical Discussion

5.2.1. Diagnosing Yeonpyeong’s Residential Environment Through Lawton’s Environmental Press Theory

5.2.2. Push–Pull Dynamics in Elderly Residential Mobility

5.2.3. Life-Space Theory and Directions for Aging-Friendly Housing Development

5.3. Policy Discussion

5.3.1. Integrating Regional Care Policy with Age-Friendly Housing Renewal

5.3.2. Administrative Challenges in Building Integrated Care Infrastructure

- ICT-supported remote care systems,

- Mobile regional service networks,

- Community manager or “village care coordinator” roles,

- Cross-agency budget pooling.

5.3.3. A Sustainable Housing Welfare Model for Aging Island Communities

5.4. Practical Implications and Research Limitations

5.4.1. Practical Implications and Applicability

5.4.2. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Recommendations

6.2.1. Academic Implications

6.2.2. Policy Recommendations

6.2.3. Practical Recommendations

- Prioritize In-Home Safety: Implement universal design upgrades (grab bars, non-slip flooring, and level-difference remediation), prioritizing residents with mobility limitations (e.g., ≥70 years old).

- Establish Multi-functional Micro-Hubs: Upgrade existing senior centers (Gyeongrodang) into multi-service micro-hubs, enabling access to essential supports (basic health monitoring, meal-related assistance, and administrative linkage) within a 10-min walking radius (~500 m).

- Deploy Digital Inclusion Services: Introduce ICT-enabled remote care and community communication platforms, coupled with structured digital literacy training to reduce the digital divide.

- Enhance Mobility Connectivity: Provide senior-friendly shuttle services (or context-appropriate shared mobility options) connecting peripheral residences with micro-hubs to ensure safe and universal access.

6.2.4. Suggestions for Future Research

- Micro level: Longitudinal studies capturing individual adaptation processes, health variation, and day-to-day environmental negotiation.

- Meso level: Evaluation of specific interventions (housing safety upgrades, mobility supports, community programming) using pre–post designs.

- Macro level: Comparative studies across rural, mountainous, and peripheral urban regions to assess transferability and inform a Korean Ageing Community Framework (K-Ageing Model).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Statistics Korea. Population Projections for Korea: 2022–2070; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2024. 2024. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the aging process. In The psychology of Adult of Development and Aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M.P., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, S.; Spann, A.; Borilovic, J.; Witte, L.; Hawley, M. Understanding the care and support needs of older people: A scoping review and categorisation using the WHO international classification of functioning, disability and health framework (ICF). BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, G.; Farmer, J. What older people want: Evidence from a study of remote Scottish communities. Rural. Remote Health 2009, 9, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.; Gibson-Smith, K.; Cunningham, S.; Pfleger, S.; Rushworth, G. A qualitative study of the perspectives of older people in remote Scotland on accessibility to healthcare, medicines and medicines-taking. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018, 40, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.S. A theory of migration. Demography 1966, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Lee, D.Y.; Jun, E.J. A spatial spectrum framework for age-friendly environments: Integrating docility and life space concepts. Buildings 2025, 15, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahana, E.; Lovegreen, L.; Kahana, B.; Kahana, M. Person–environment fit and adaptive strategies of the aged: Implications for aging in place. In Aging in Context; Wah, J.W., Scheidt, R.J., Windley, P.G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, E.A.; Oberlink, M.; Scharlach, A.E.; Neal, M.B.; Stafford, P.B. Age-friendly community initiatives: Conceptual issues and key questions. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services; WHO Press, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, K.; Wiles, J.L.; Allen, R.E.S. Resilience: Thoughts on the value of the concept for critical gerontology. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Cho, S.Y.; Jun, E.J. Assessing the residential suitability of elderly housing in coastal island communities from the fall prevention perspective. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2025, 41, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kim, M.; Chung, S. Factors Influencing Loneliness of Older Adults: Analysis of Individual and Regional Factors Using Multilevel Analysis. Korean Assoc. Surv. Res. 2023, 24, 157–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L.N. Conducting research on home environments: Lessons learned and new directions. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Oswald, F. Environmental perspectives on aging. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Gerontology; Dannefer, D., Phillipson, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipson, C. Ageing; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson, S.; Ståhl, A. Accessibility, usability, and universal design—Positioning and definition of concepts describing person–environment relationships. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, L.L.; Steggell, C.D.; Iwarsson, S. Adaptive Strategies and Person-Environment Fit among Functionally Limited Older Adults Aging in Place: A Mixed Methods Approach. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2015, 12, 11954–11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.H.; Sirkeci, I. Cultures of Migration: The Global Nature of Contemporary Mobility; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, M.; Entwistle, V.; Kelly, T.; Illsley, B. Moving residence in later life: Actively shaping place and wellbeing. Int. J. Ageing Later Life 2021, 15, 127–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Halfacree, K. To Revitalise Counterurbanisation Research? Recognising an International and Fuller Picture. Popul. Space Place 2008, 14, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Nihon no tōsho no kōsei [Composition of Japan’s Islands]. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Tokyo, Japan, 2025. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/kokudoseisaku/chirit/content/001477518.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Yoshida, M.; Tatsukawa, M.; Otani, S.; Fujimura, K. Thoughts of older adults living in an isolated community on a remote island while continuing to live in familiar surroundings. Jpn. Soc. Public Health 2025, 72, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.co.kr/maps/@/data=!5m1!1e4?hl=en&entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTIwOS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Webber, S.C.; Porter, M.M.; Menec, V.H. Mobility in older adults: A comprehensive framework. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.; Nayak, U.S.L.; Isaacs, B. The life-space diary: A measure of mobility in old people at home. Int. Rehabil. Med. 1985, 7, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, P.S.; Bodner, E.V.; Allman, R.M. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1610–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T.; Thompson, C.W. Outdoor environments, activity and the well-being of older people: Conceptualising environmental support. Sage J. 2007, 39, 1943–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, J. Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, one Step at a Time; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marquet, O.; Miralles-Guasch, C. The walkable city and the importance of the proximity environments for Barcelona’s everyday mobility. Cities 2015, 42, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipson, C. Urbanisation and ageing: Towards a new environmental gerontology. Ageing Soc. 2004, 24, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Weisman, G.D. Environmental gerontology at the beginning of the new millennium: Reflections on its historical, empirical, and theoretical development. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging Well and the Environment: Toward an Integrative Model and Research Agenda for the Future. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, F.M.; Carp, A. A Complementary/Congruence Model of Well-Being or Mental Health for the Community Elderly. In Elderly People and the Environment. Human Behavior and Environment; Altman, I., Lawton, M.P., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, S.; Keglovits, M.; Somerville, E.; Hu, Y.L.; Barker, A.; Sykora, D.; Yan, Y. Home hazard removal to reduce falls among community-dwelling older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2122044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Wahl, H.-W.; Matthews, J.T.; De Vito Dabbs, A.; Beach, S.R.; Czaja, S.J. Advancing the aging and technology agenda in gerontology. Gerontologist 2018, 55, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.; Jang, M.; Kang, H. Implications of the health conditions of elderly residents in old houses in Yeonpyeong-do on housing improvement. Des. Converg. Study 2025, 24, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.G.; Stolterman, E. The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Design thinking. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 84–92. Available online: https://hbr.org/2008/06/design-thinking (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Statistical Yearbook of Health and Welfare. Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea; 2023. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10107010202&bid=0037&act=view&list_no=1481006 (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Statistical Yearbook of Health and Welfare. Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea; 2022. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10107010202&bid=0037&act=view&list_no=378218 (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements. National Territorial Policy Trends Report. KRIHS: Sejong, Republic of Korea. 2020. Available online: https://www.krihs.re.kr/gallery.es?mid=a10702050000&bid=0043&list_cnt= (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Statistical Yearbook of Local Administration. Government of the Republic of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2011. Available online: https://www.mois.go.kr (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Wong, D.L.; Baker, C.M. Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr. Nurs. 1988, 14, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Herr, K.; Coyne, P.J.; McCaffery, M.; Manworren, R.; Merkel, S. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: Position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain. Manag. Nurs. 2011, 12, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandek, B.; Sinclair, S.J.; Kosinski, M.; Ware, J.E. Psychometric Evaluation of the SF-36® Health Survey in Medicare Managed Care. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2004, 25, 5–25. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4194895/ (accessed on 28 October 2025). [PubMed]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cutchin, M.P.; Kemp, C.; Marshall, V. Researching Social Gerontology; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, 1st ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 1–374. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land; Infrastructure and Transport. Mobility Innovation Roadmap. MOLIT: Sejong City, Republic of Korea; 2022. Available online: https://www.molit.go.kr/USR/NEWS/m_71/dtl.jsp?id=95087208 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

| Concept | Scholarly Definition & Theoretical Basis | Key Citation | Relevance to This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging Concern | Early-stage perceptual signals showing that residents recognize instability, insufficiency, or mismatch in their living environments. Conceptually represents the cognitive–affective precursor to environmental or behavioral adaptation. | Kahana et al. [9]; Lawton & Nahemow [3] | Interprets Yeonpyeong residents’ subtle worries (mobility decline, lack of services, safety risks) as the earliest signals of environmental transformation needs. |

| Signal of a Paradigm Shift | Detectable turning point in expectations, values, and behavioral orientation; indicates collective movement from individual-based aging patterns toward community-integrated and preventive care models. | Kuhn [10]; Greenfield et al. [11] | Frames residents’ expressed needs as societal cues suggesting the island is transitioning toward integrated community care. |

| Infrastructure for Integrated Community Care | A multidimensional system combining physical environments (housing, community hubs, mobility paths), service networks (healthcare, welfare, nutrition, safety), and ICT platforms (telehealth, monitoring, coordination) to support autonomy, participation, and preventive care. | WHO [12]; Wiles et al. [13]; Greenfield et al. [11] | Provides conceptual grounding for the proposed spatial restructuring and service-integration model for aging-friendly island communities. |

| No. | Structural Feature | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Theoretical Induction | Expands or modifies existing theories based on field-grounded data. |

| 2 | Conceptual Integration | Synthesizes Environmental Press, Push–Pull, and Life-Space frameworks into one integrative system. |

| 3 | Generative Outcome | Produces the conceptual model of Environmental Intervention-Based Integrative Care Infrastructure (EIICI) as a theoretical innovation. |

| Stage | Research Focus | Key Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Theoretical Framing | Establishes core frameworks—Environmental Press, Push–Pull Dynamics, and Life-Space. |

| 2 | Empirical Grounding | Conducts field surveys, interviews, and contextual observations in aging island settings. |

| 3 | Conceptual Integration | Reinterprets the push–pull relationship as the structural mechanism of the EIICI model. |

| 4 | Visual Modeling | Presents the conceptual framework for sustainable spatial transformation in island communities. |

| Age (Year) | Total | Man | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–19 | 132 | 71 | 61 |

| 20–50 | 937 | 697 | 240 |

| 51–64 | 479 | 288 | 191 |

| Over 65 | 445 | 214 | 231 |

| Total | 1993 | 1270 | 723 |

| No. | Strategy | Description | Expected Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Surveyor Recruitment | Recruited a long-term resident and community leader with administrative experience as field surveyor; leveraged social trust and contextual insight to elicit candid, accurate responses. | Enhanced participant trust and contextual accuracy. |

| 2 | Surveyor Training and Workshop | Conducted iterative workshops on research aims, question intent, ethics, and interview practice, including hands-on tablet/Google Form use. | Improved interviewer consistency and ethical awareness. |

| 3 | Visual Scale for Accuracy | Applied a smile-face graphic scale so elderly respondents with limited literacy or hearing could indicate answers visually rather than verbally. | Increased precision and self-directed participation. |

| 4 | Flexible Time Scheduling | Arranged interviews around daily work routines, avoiding early-morning and late-evening fatigue periods. | Reduced inattentive or rushed replies; stronger focus. |

| 5 | Contextual Verification | Used local surveyor follow-up questions to clarify ambiguous answers and confirm field context. | Greater reliability through on-site triangulation. |

| Stage | Period | Description | Main Purpose and Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preliminary Field Visit | January 2025 | Initial site visit and environmental assessment |

| 2 | 1st Exploratory Field Survey | March 2025 | Pilot testing of questionnaire and graphic scale of face icon |

| 3 | 2nd Preparatory Interview | May 2025 | Consultation with community representative |

| 4 | Pre-Survey Preparation & Training | June 2025 | Recruitment and training of local surveyor |

| 5 | Main On-Site Interview Survey | July 2025 | Final face-to-face survey (n = 102, approx. 23% of elderly residents) |

| Cluster | Participants | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Daeyeonpyeong 1–ri | 21 | Fishing- and farming-oriented, high proportion of detached housing |

| Daeyeonpyeong 2–ri | 19 | High rate of single-person households |

| Daeyeonpyeong 3–ri | 18 | Located near the village center and senior hall |

| Soyeonpyeong 1–ri | 24 | Limited transportation, low medical accessibility |

| Soyeonpyeong 2–ri | 20 | Higher proportion of shared or collective living |

| Total | 102 | Approx. 50% of the island’s senior population |

| Stage | Title | Core Content | Question Type | Analytical Focus & Linkage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Background Information | (1) Basic demographics, health status, mobility, and dwelling type | Objective/ Descriptive | Establish sample profile and control variables |

| 2 | Current Residential Conditions | (1) Residential adequacy and housing conditions (detached houses) (2) Use and perceived importance of community facilities and spatial mobility patterns | Fact-oriented | Mainly Push Factors— identification of physical and social constraints |

| 3 | Perceived Needs for Future Living & Community Infrastructure | (1) Perceived adequacy and improvement needs of current housing (2) Necessity and acceptability of alternative housing (3) Perceived need for community facilities and social connection | Perception- oriented | Push–Pull Interaction—awareness of discomfort (push) and aspiration for improvement (pull) |

| Category | Facility | n (%) | Facility Use Frequency (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 1–2 Times/Week | Once/Month | Once/Season | Once/Year | Never Use | |||

| Basic Health-Maintenance Activities | Convenience Store/Mart | 102 (100.00) | 4 (3.92) | 59 (57.84) | 15 (14.71) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (1.00) | 22 (21.57) |

| Public Health center | 102 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (4.90) | 62 (60.78) | 24 (23.53) | 2 (1.96) | 9 (8.82) | |

| Public Bathhouse | 102 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 33 (32.35) | 40 (39.22) | 3 (2.94) | 2 (1.96) | 24 (23.5) | |

| Administrative Task– Related Activities | Senior Center | 102 (100.00) | 54 (52.94) | 2 (1.96) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.98) | 43 (42.16) |

| Resident Service Center | 101 (99.02) | 3 (2.94) | 0 (0.00) | 6 (5.88) | 30 (29.41) | 33 (32.35) | 30 (29.41) | |

| Post Office | 102 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 8 (7.84) | 7 (6.86) | 6 (5.88) | 3 (2.94) | 78 (76.47) | |

| Bank | 101 (99.02) | 0 (0.00) | 11 (10.78) | 52 (50.98) | 11 (10.78) | 2 (1.96) | 26 (25.49) | |

| Outdoor Health- Promotion Activities | Outdoor Sports Facility | 102 (100.00) | 27 (26.47) | 10 (9.80) | 1 (0.98) | 4 (3.92) | 6 (5.88) | 54 (52.94) |

| Walking Trail | 102 (100.00) | 4 (3.92) | 2 (1.96) | 2 (1.96) | 7 (6.86) | 41 (40.20) | 46 (45.10) | |

| Park | 102 (100.00) | 11 (10.78) | 17 (16.67) | 1 (0.98) | 25 (24.51) | 12 (11.8) | 36 (35.29) | |

| Indoor Leisure Activities | Indoor Sports Facility | 102 (100.00) | 4 (3.92) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.96) | 1 (0.98) | 95 (93.14) |

| Cafés | 101 (99.02) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.98) | 100 (98.04) | |

| Cinema | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 102 (100.00) | |

| Others | Religious* & Transportation** Facilities | 1 (0.98) | 2 (1.96)* | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98)** | 0 (0.00) | 99 (97.06) |

| No. | Facility | Rank 1 | Rank 2 | Rank 3 | Overall Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Public Health Center | 2 (1.96) | 21 (20.59) | 35 (34.31) | 58 (56.86) |

| 2 | Senior Center | 36 (35.29) | 12 (11.76) | 7 (6.86) | 55 (53.92) |

| 3 | Resident Service Center | 33 (32.35) | 4 (3.92) | 2 (1.96) | 39 (38.24) |

| 4 | Religions Facility | 10 (9.80) | 14 (13.73) | 5 (4.90) | 29 (28.43) |

| 5 | Convenience Store/Mart | 2 (1.96) | 8 (7.84) | 12 (11.76) | 22 (21.57) |

| 6 | Hospital | 5 (4.90) | 10 (9.80) | 5 (4.90) | 20 (19.61) |

| 7 | Community Welfare Center | 1 (0.98) | 9 (8.82) | 8 (7.84) | 18 (17.65) |

| 8 | Outdoor Sports Facility | 7 (6.86) | 5 (4.90) | 3 (2.94) | 15 (14.71) |

| 9 | Park | 2 (1.96) | 1 (0.98) | 8 (7.84) | 11 (10.78) |

| 10 | Bank | 0 (0.00) | 4 (3.92) | 7 (6.86) | 11 (10.78) |

| 11 | Post office | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.96) | 3 (2.94) | 5 (4.90) |

| 12 | Indoor Sports Facility | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.98) | 2 (1.96) | 4 (3.92) |

| 13 | Public Bathhouse | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.96) | 2 (1.96) | 4 (3.92) |

| Category | Item | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceptions of Aging-Related Health Decline | 1. I feel that gradual aging is causing noticeable changes. | 1 (0.98) | 54 (52.94) | 45 (44.12) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.98) | 3.52 (0.59) |

| 2. My health condition has worsened over the past year and a half. | 0 (0.00) | 18 (17.65) | 82 (80.39) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.98) | 3.15 (0.45) | |

| 3. I am afraid that I may fall when moving around alone. | 3 (2.94) | 41 (40.20) | 55 (53.92) | 2 (1.96) | 1 (0.98) | 3.42 (0.64) | |

| Awareness of Safety Risks and Grab Bar Necessity | 4. I feel that installing grab bars is useful. | 17 (16.67) | 45 (44.12) | 36 (35.29) | 4 (3.92) | 0 (0.00) | 3.74 (0.78) |

| 5. As I grow older, daily mobility within the home is becoming more difficult. | 12 (11.76) | 73 (71.57) | 17 (16.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 3.95 (0.53) | |

| 6. I think grab bars are needed in other areas of the home as well. | 8 (7.84) | 41 (40.20) | 46 (45.10) | 7 (6.86) | 0 (0.00) | 3.49 (0.74) | |

| Perceived Necessity and Expected Benefits of Home Modification | 7. I believe that improving residential features will greatly enhance convenience. | 22 (21.57) | 50 (49.02) | 30 (29.41) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 3.92 (0.71) |

| 8. Certain parts of my home need improvement to ensure safety and usability. | 6 (5.88) | 45 (44.12) | 49 (48.04) | 2 (1.96) | 0 (0.00) | 3.54 (0.64) | |

| 9. If properly repaired, I could live in my home for a longer period. | 18 (17.65) | 46 (45.10) | 34 (33.33) | 4 (3.92) | 0 (0.00) | 3.76 (0.79) | |

| 10. If my home is modified, I will be able to live more independently for longer. | 16 (15.69) | 45 (44.12) | 36 (35.29) | 5 (4.90) | 0 (0.00) | 3.71 (0.79) |

| Gender | Mean (SD) | F (df) | p | Post Hoc Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 65–74 | Age 75–84 | Age 85+ | ||||

| Female | 3.69 (0.64) | 3.75 (0.65) | 3.83 (0.51) | F (2.74) = 0.25 | 0.778 | ns |

| Male | 3.50 (0.57) | 3.89 (0.71) | 3.63 (0.47) | F (2.22) = 0.97 | 0.397 | ns |

| Category | Item | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Strain and Residential Fit | 1. Daily living is becoming increasingly difficult. | 2 (1.96) | 52 (50.98) | 48 (47.06) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 3.55 (0.54) |

| 2. I am worried about depression and loneliness. | 1 (0.98) | 15 (14.71) | 76 (74.51) | 10 (9.80) | 0 (0.01) | 3.07 (0.53) | |

| 3. I need meal service support. | 1 (0.98) | 26 (25.49) | 62 (60.78) | 12 (11.76) | 1 (0.98) | 3.14 (0.66) | |

| Emotional Needs and Relational Dependency | 4. I miss having people come and go. | 6 (5.88) | 76 (74.51) | 19 (18.63) | 0 (0.01) | 1 (0.98) | 3.84 (0.56) |

| 5. I wish there were more opportunities to interact with neighbors. | 25 (24.51) | 70 (68.63) | 7 (6.86) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.18 (0.53) | |

| 6. It would be reassuring to have someone nearby in case of an emergency. | 43 (42.16) | 56 (54.90) | 3 (2.94) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.39 (0.55) | |

| Cognitive Openness toward Community-Based Living | 7. Outdoor mobility is becoming increasingly difficult. | 2 (1.96) | 32 (31.37) | 59 (57.84) | 9 (8.82) | 0 (0.00) | 3.26 (0.64) |

| 8. I am concerned about whether I can continue living in my current home. | 5 (4.90) | 37 (36.27) | 52 (50.98) | 8 (7.84) | 0 (0.00) | 3.38 (0.70) | |

| 9. I would like to live together with others while maintaining personal privacy. | 37 (36.27) | 57 (55.88) | 8 (7.84) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.28 (0.60) | |

| 10. Well-designed community housing supports autonomous living. | 67 (65.69) | 27 (26.47) | 8 (7.84) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.58 (0.64) |

| Gender | Mean (SD) | F (df) | p | Post Hoc Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 65–74 | Age 75–84 | Age 85+ | ||||

| Female | 3.74 (0.40) | 3.94 (0.46) | 4.09 (0.45) | F (2.74) = 3.79 | 0.027 | 65–74 < 75–84 < 85+ |

| Male | 3.53 (0.31) | 3.95 (0.43) | 4.00 (0.47) | F (2.22) = 3.18 | 0.061 | ns |

| Category | Item | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequacy and Accessibility of Leisure Spaces | 1. Appropriate places where I can spend my leisure time together with others are well provided. | 3 (2.94) | 0 (0.01) | 4 (3.92) | 74 (72.55) | 21 (20.59) | 1.92 (0.71) |

| 2. The routes to meeting places are well connected and easy to use. | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (4.90) | 80 (78.43) | 16 (15.69) | 1.92 (0.54) | |

| 3. There are places I can continue to visit even as I grow older. | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (4.90) | 86 (84.31) | 10 (9.80) | 1.98 (0.49) | |

| Demand for Programmatic and Service Integration | 4. It would be good if a variety of services were provided in a single place. | 58 (56.86) | 43 (42.16) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 4.55 (0.56) |

| 5. We need places that can be used together by people of different age groups. | 76 (74.51) | 25 (24.51) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.74 (0.47) | |

| 6. It would be good to have places where programs are well provided. | 95 (93.14) | 5 (4.90) | 2 (1.96) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.83 (0.40) | |

| Environmental and Climatic Requirements for New Community Facilities | 7. Places that I can go to even when my mobility is limited are necessary. | 86 (84.31) | 15 (14.71) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.91 (0.35) |

| 8. We need places that can be used during very hot or very cold weather. | 95 (93.14) | 6 (5.88) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.92 (0.31) | |

| 9. When working together with others, I would like the work environment and conditions to be good. | 94 (92.16) | 7 (6.86) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.91 (0.32) | |

| 10. Good community spaces support an autonomous, self-reliant life. | 96 (94.12) | 6 (5.88) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4.94 (0.24) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.S.; Jun, E.J.; Park, J.H. Emerging Resident Concerns as Signals of a Paradigm Shift in the Spatial Infrastructure for Integrated Community Care: Focusing on Yeonpyeong Island, a Medically Isolated Declining Region of Korea. Buildings 2026, 16, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010218

Lee YS, Jun EJ, Park JH. Emerging Resident Concerns as Signals of a Paradigm Shift in the Spatial Infrastructure for Integrated Community Care: Focusing on Yeonpyeong Island, a Medically Isolated Declining Region of Korea. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010218

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yeun Sook, Eun Jung Jun, and Jae Hyun Park. 2026. "Emerging Resident Concerns as Signals of a Paradigm Shift in the Spatial Infrastructure for Integrated Community Care: Focusing on Yeonpyeong Island, a Medically Isolated Declining Region of Korea" Buildings 16, no. 1: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010218

APA StyleLee, Y. S., Jun, E. J., & Park, J. H. (2026). Emerging Resident Concerns as Signals of a Paradigm Shift in the Spatial Infrastructure for Integrated Community Care: Focusing on Yeonpyeong Island, a Medically Isolated Declining Region of Korea. Buildings, 16(1), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010218