Mechanical Performance of Joints with Bearing Plates in Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Arch-Supporting Column-Prestressed Steel Reinforced Concrete Beam Structures: Numerical Simulation and Design Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

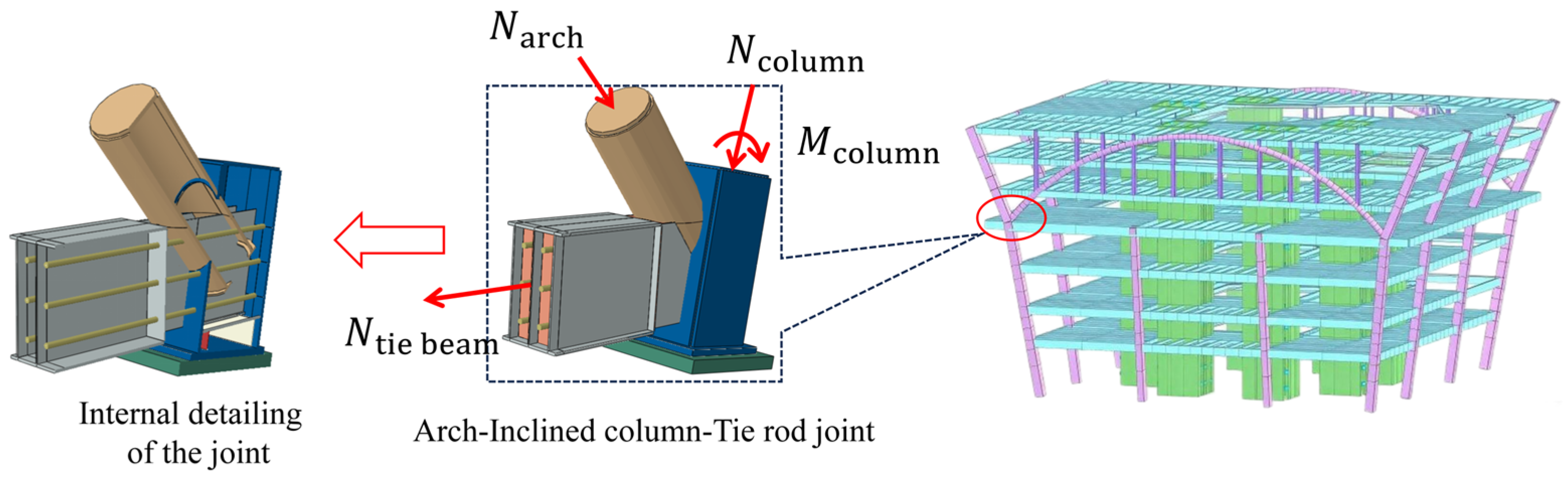

2. Research Object

2.1. Project Background

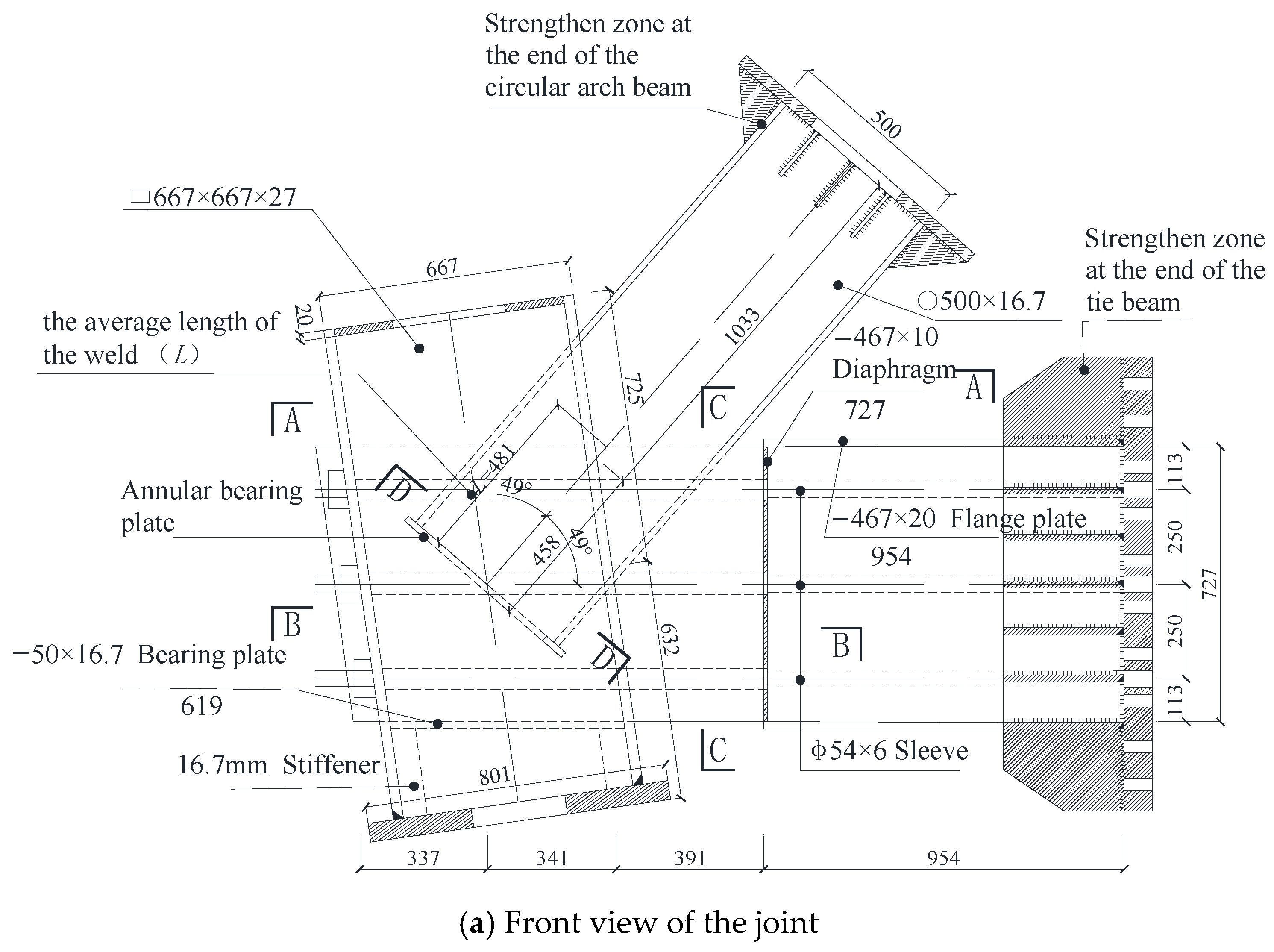

2.2. Construction and Design Concept of the Joint

- (1)

- Connection design at the arch beam-tie beam intersection: The circular CFST arch beam is inserted into the joint zone. Slots are cut into the circular steel tube to allow the three web plates of the tie beam to pass through. The web plates are connected to the steel tube using groove full-penetration welds, forming an engagement segment with an average length of L. This design transfers part of the axial force from the arch to the tie beam’s web plates via shear through the welds.

- (2)

- Setting of an annular bearing plate at the arch beam end: An annular plate is installed at the end of the circular steel tube to increase the contact area between the tube and the concrete in the joint zone. This action disperses the concentrated axial force from the steel tube more uniformly into the concrete, thereby preventing concrete splitting and ensuring a more uniform local stress transfer.

- (3)

- Connection design at the tie beam-inclined column intersection: Slots are opened in the inclined column to allow the three web plates of the tie beam to pass through. After passing through the inclined column, the tie beam’s web plates are welded to the steel tube of the inclined column.

- (4)

- Arrangement of tie beam flanges and prestressed cables: To ensure thorough compaction of the concrete, the upper and lower flanges of the tie beam are discontinued outside the joint zone, thus avoiding intrusion into the joint core during casting. The prestressed cables are arranged horizontally between the web plates of the tie beam, passing through the joint zone and anchored outside the supporting column. Horizontal bearing plates are provided at the bottom of the web plates within the joint zone to assist in transferring the prestressing force.

- (5)

- Integrated concrete casting: Concrete is cast continuously in a single operation for the circular steel tube, the joint zone, and the tie beam, forming an integral concrete core. This ensures continuous force transfer and maintains the integrity of the joint.

2.3. Preliminary Validation of the Rationality of Joint Construction

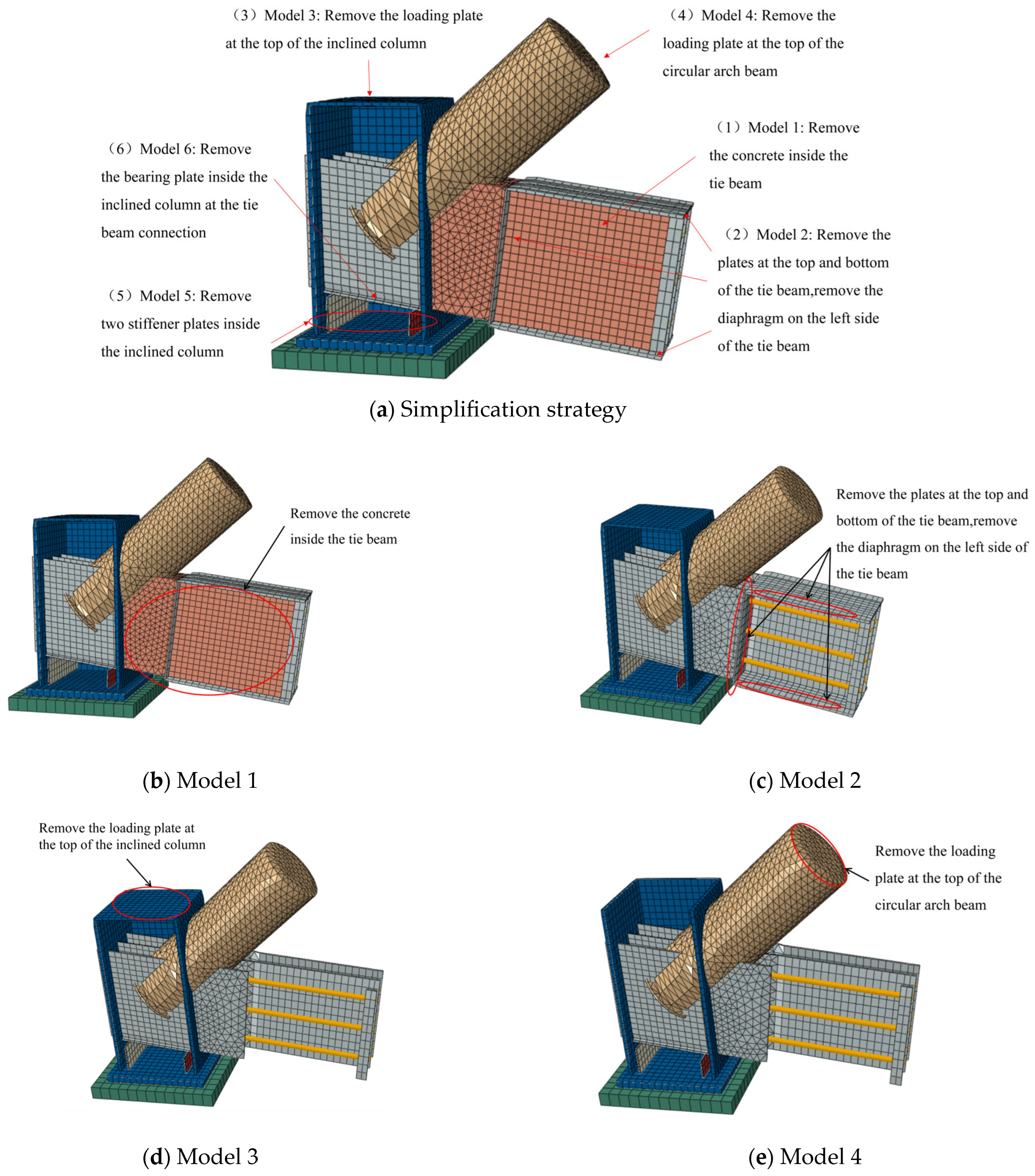

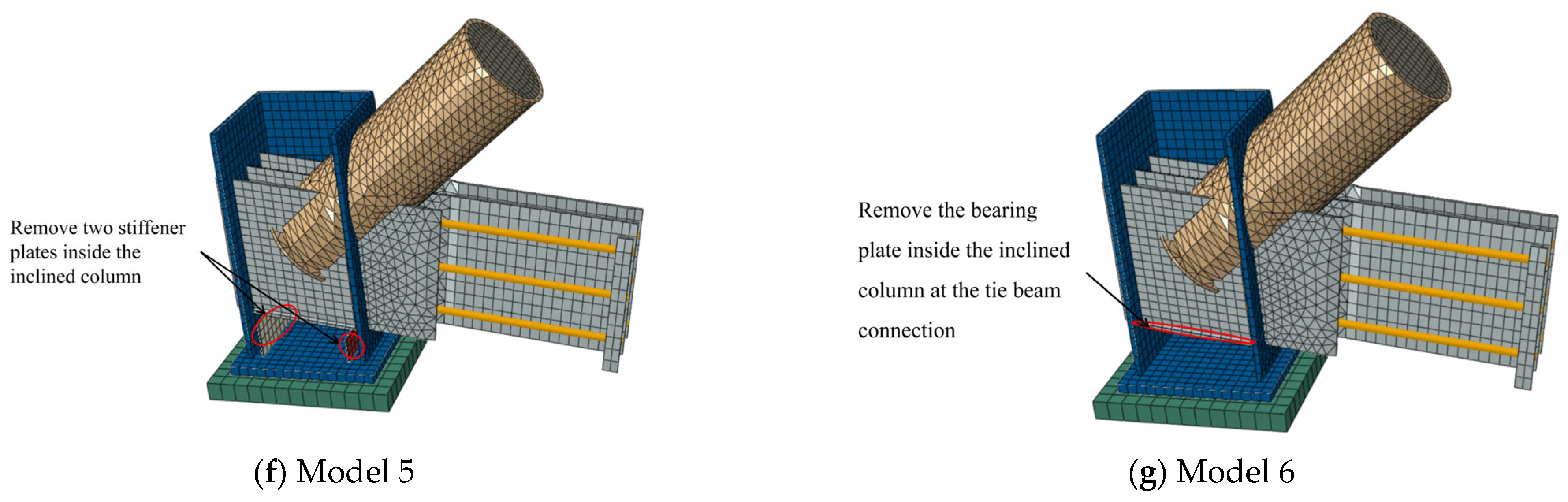

3. Numerical Simulation

3.1. Geometric Modeling

3.2. Material Properties

3.3. Boundary Conditions and Contact Interactions

- (1)

- The end of the tie beam was designed as a fixed support.

- (2)

- The end of the circular arch beam was free, and axial compression was applied at this location.

- (3)

- The top of the inclined column was free, and the relatively small load transferred from the upper floors was neglected.

- (4)

- As mentioned above, under the most critical design condition, the horizontal shear force in the column is only 0.29 times of the force in the tie beam. Therefore, the horizontal resistance of the inclined column was neglected, with only the balance between the horizontal components of the tie beam and the circular arch beam considered in the analysis. This approach results in a more critical load condition for the tie beam and represents a conservative simplification, and it is also adopted in the design method. In the numerical model, the bottom of the inclined column was provided with a sliding support.

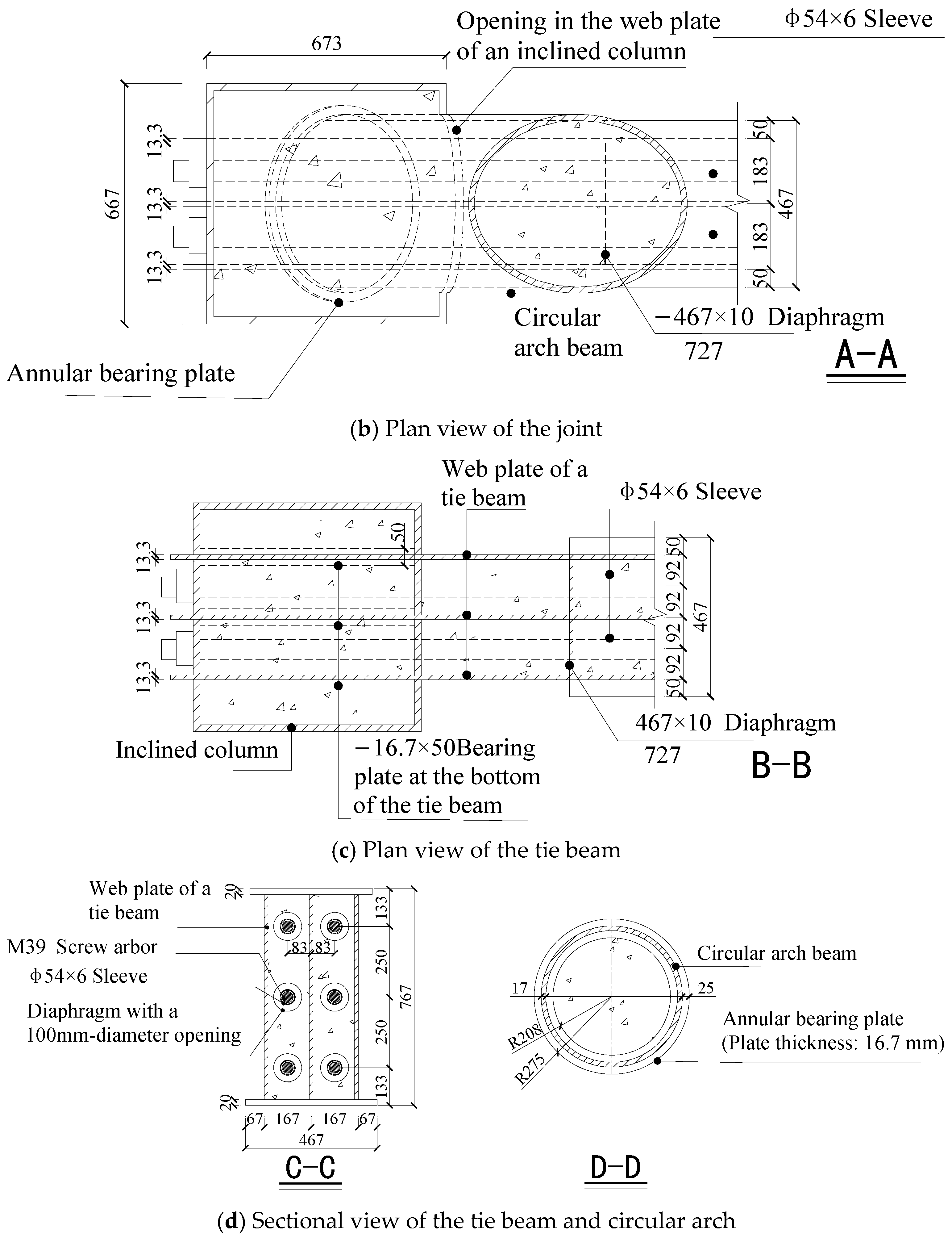

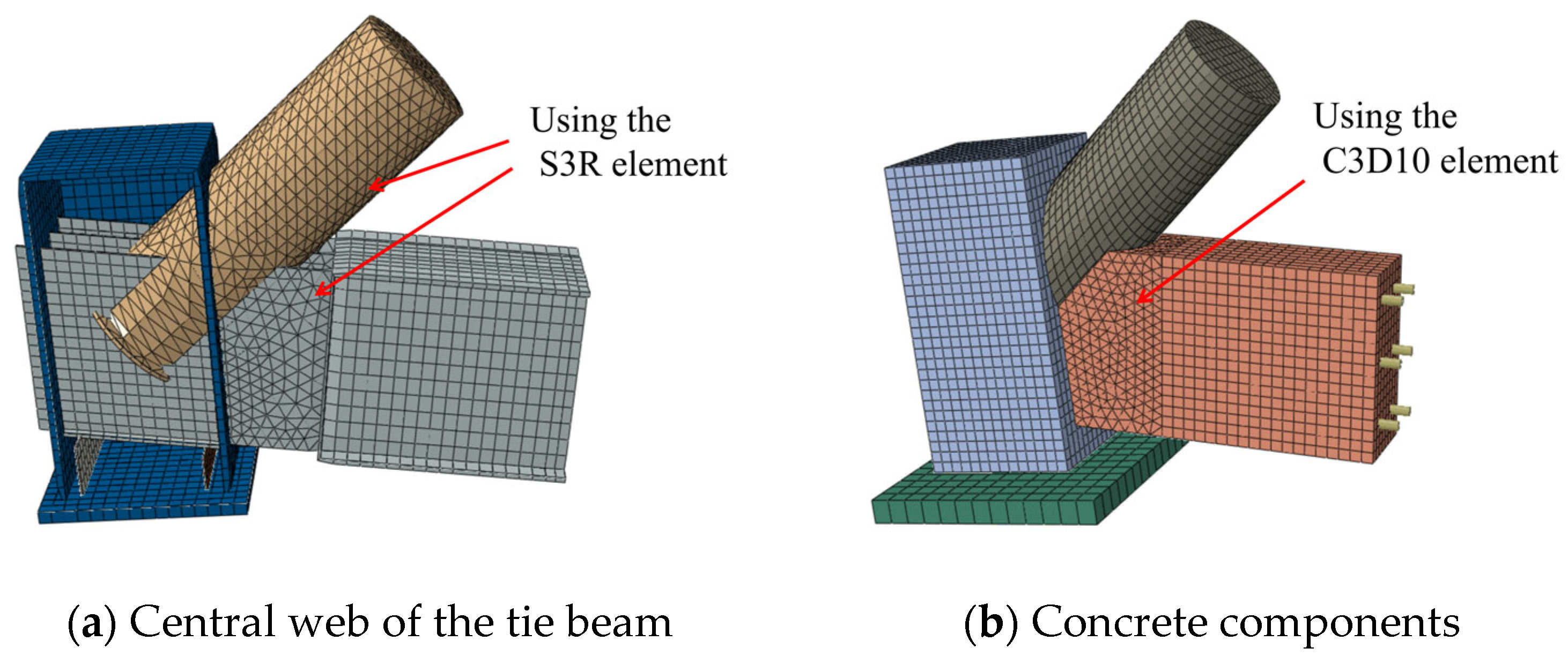

3.4. Element Selection and Meshing

3.5. Loading Protocol

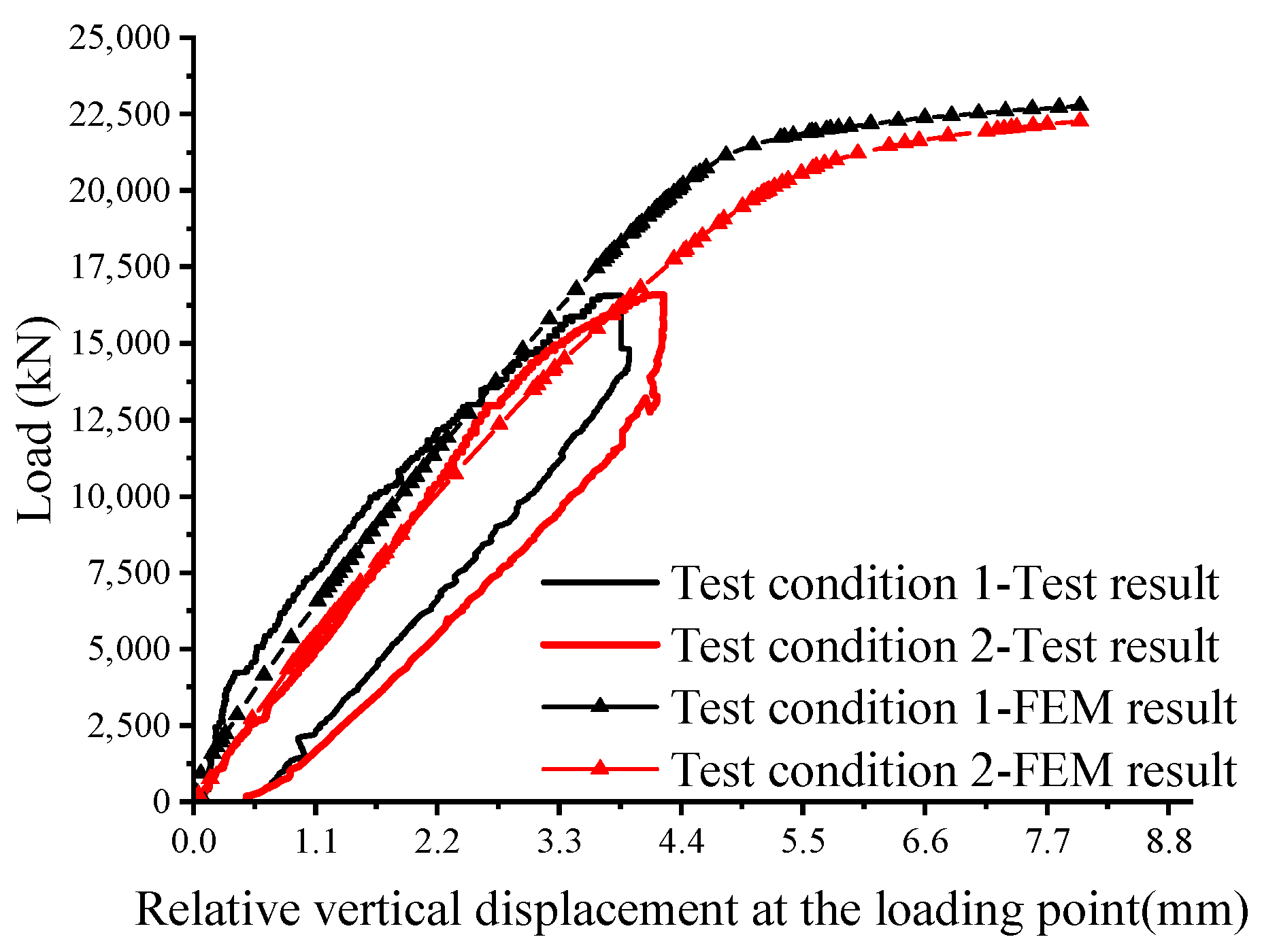

- (1)

- Condition 1: Loading was applied up to the design value of 9967 kN, corresponding to 1/9 of the original structural design load. It was then increased from 9967 kN to the test system’s maximum capacity of 16,500 kN, and further continued until significant failure characteristics were observed in the model.

- (2)

- Condition 2: After removing the six prestressed high-strength rods to simulate the unfavorable condition of prestress loss, the same loading protocol as in Condition 1 was applied.

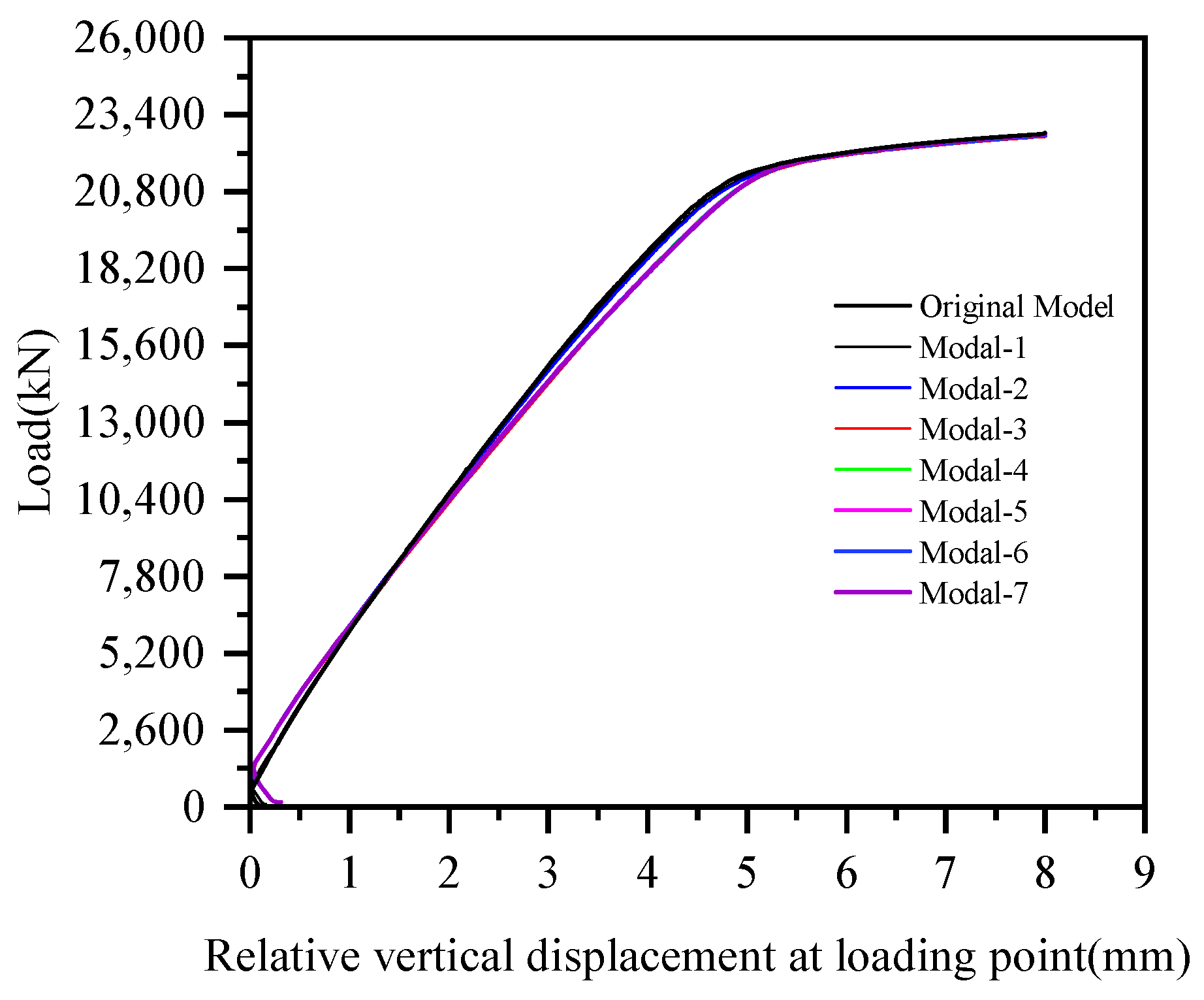

3.6. Validation

4. Analysis of the Force Mechanism

4.1. The Load-Bearing Capacity and Deformation Characteristics

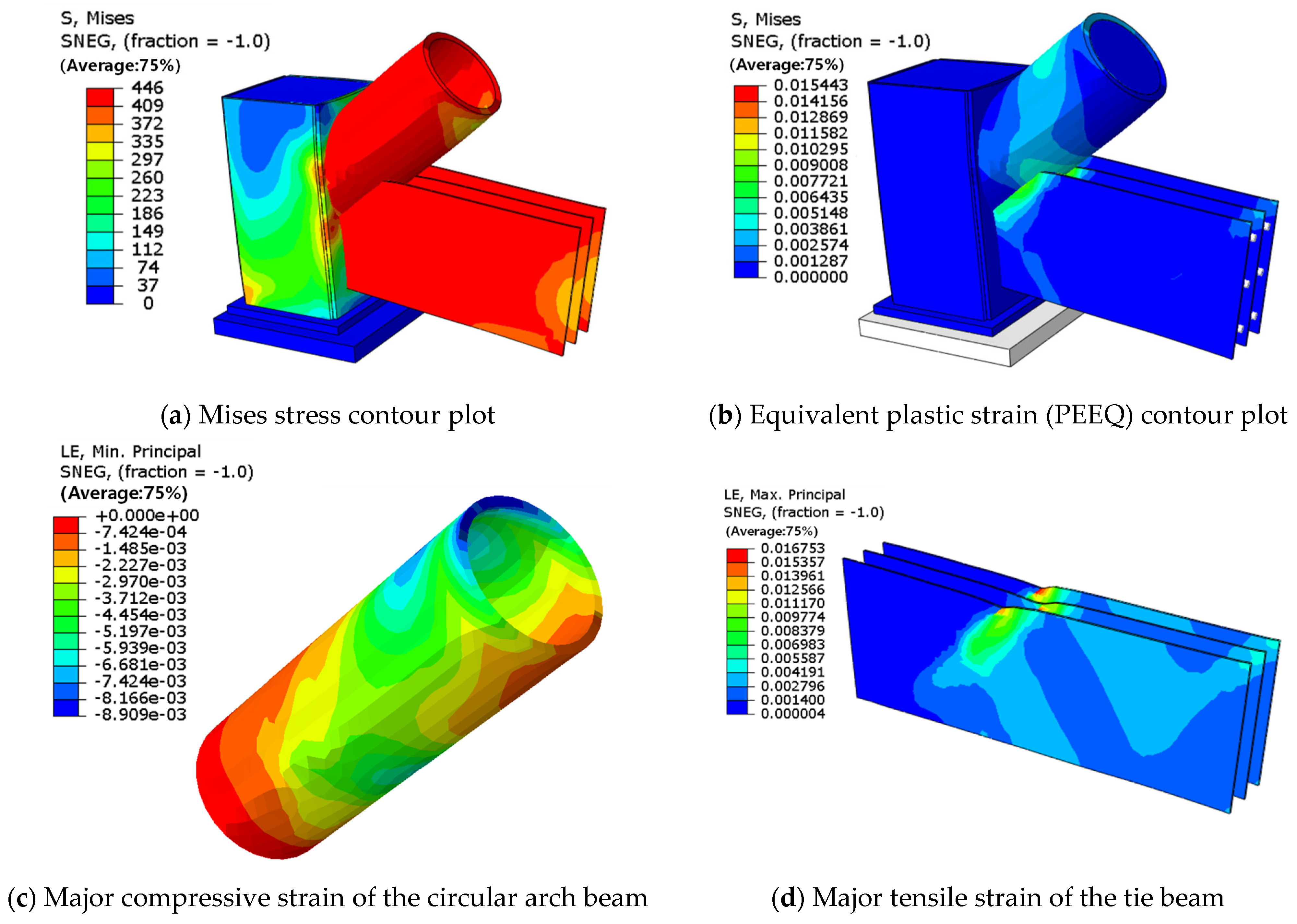

4.2. Effect of Prestressed Rods on Joint Stress Distribution and Plastic Zone Development

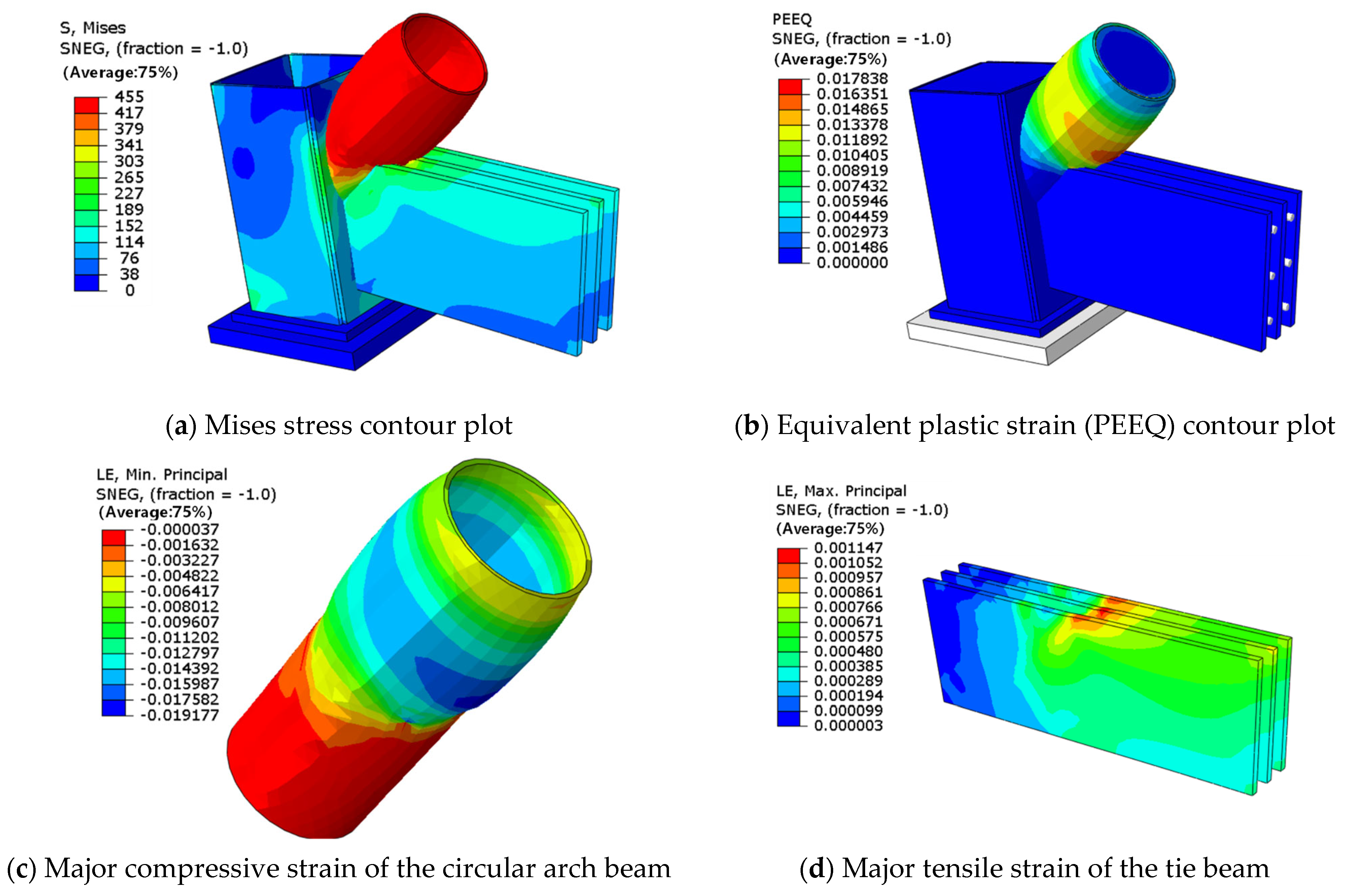

4.3. Joint Stress Distribution and Plastic Zone Propagation Under Failure of Prestressed Rods

5. Parametric Analysis

5.1. Thickness of Tie Beam Web Plates

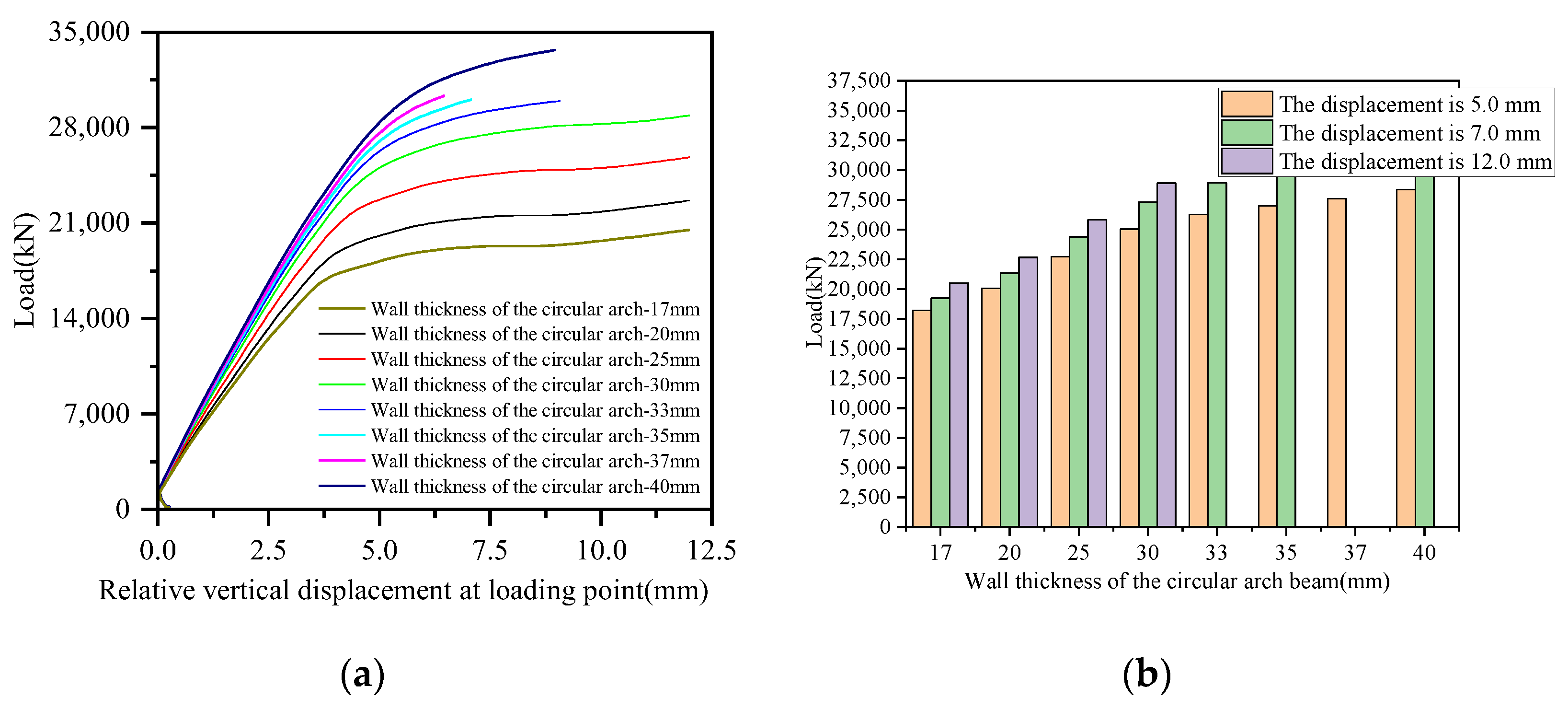

5.2. Wall Thickness of the Circular Arch Beam Steel Tube

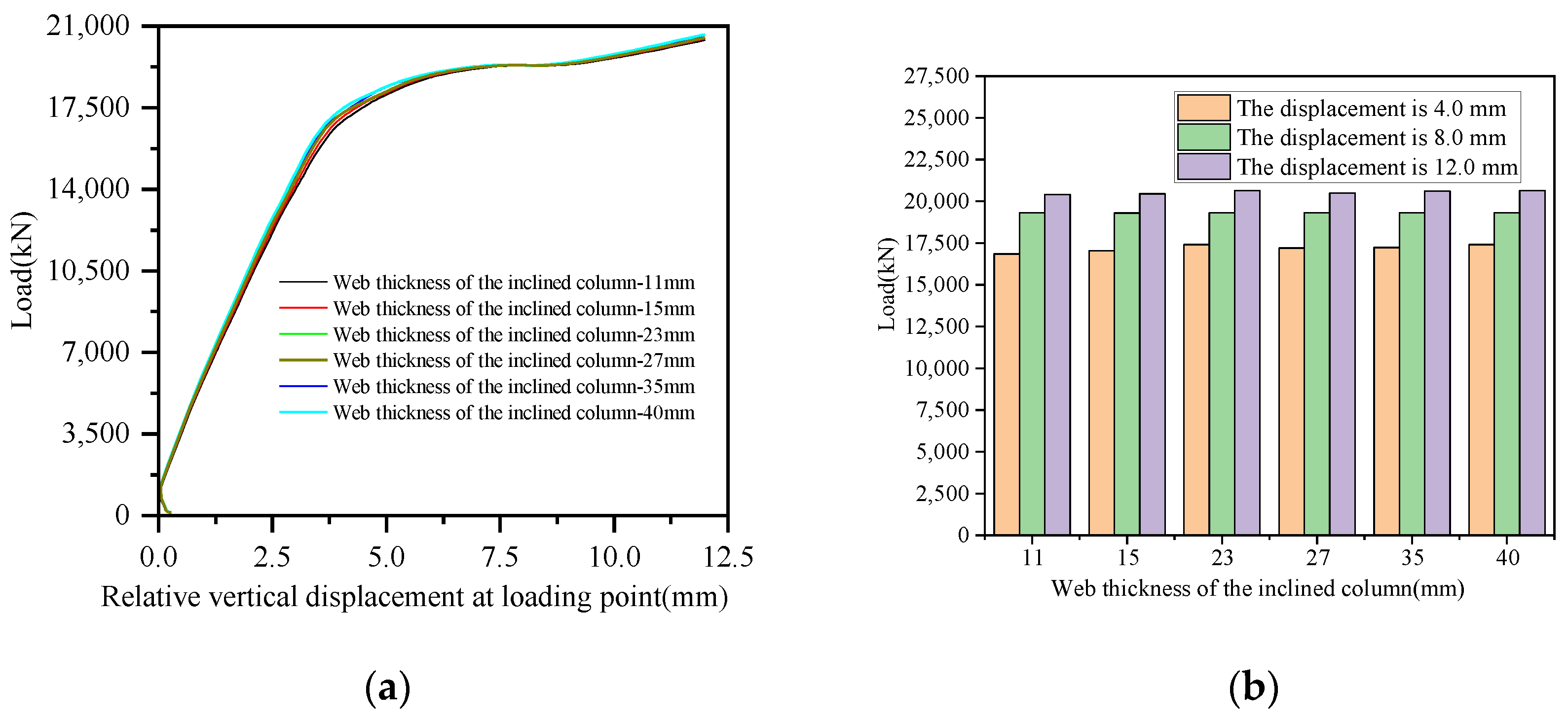

5.3. Wall Thickness of the Inclined Column Steel Tube

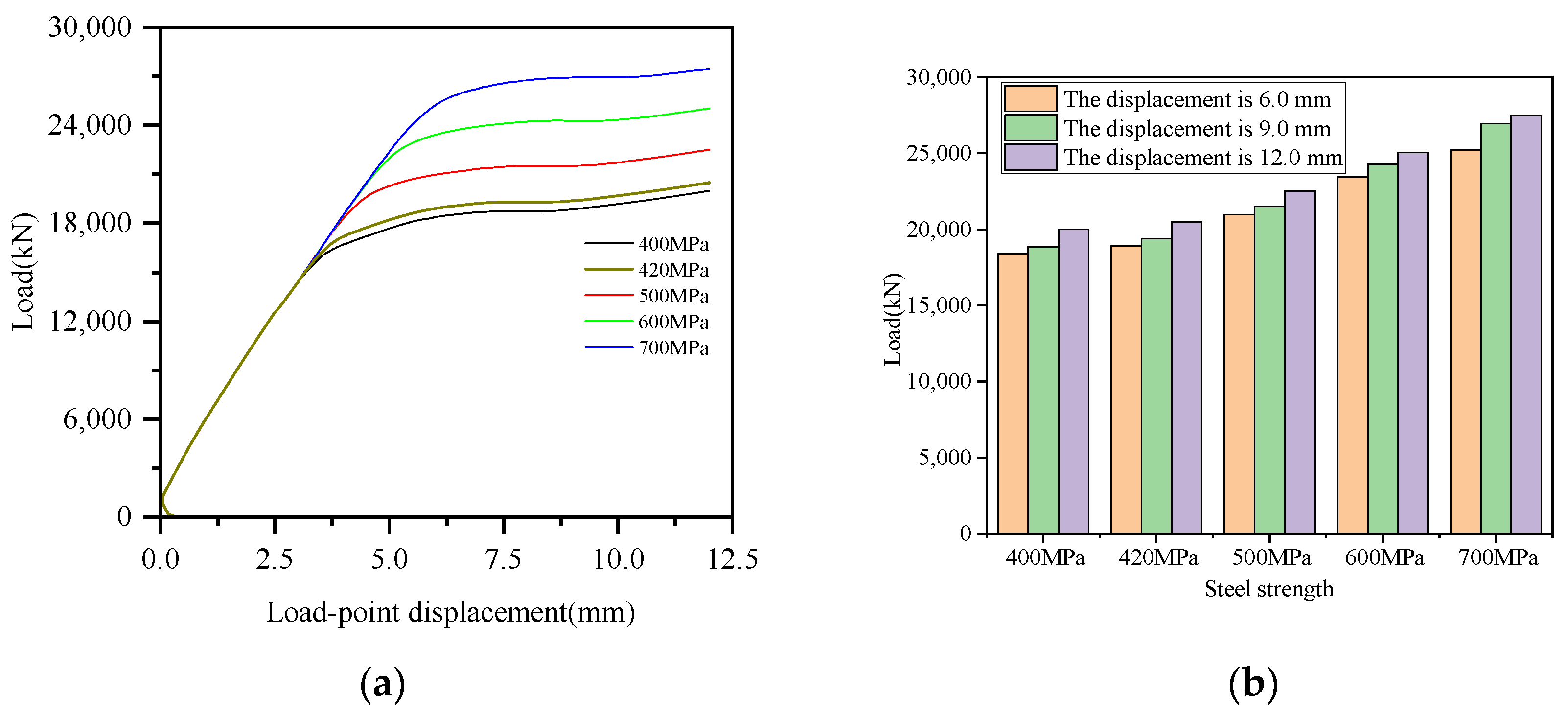

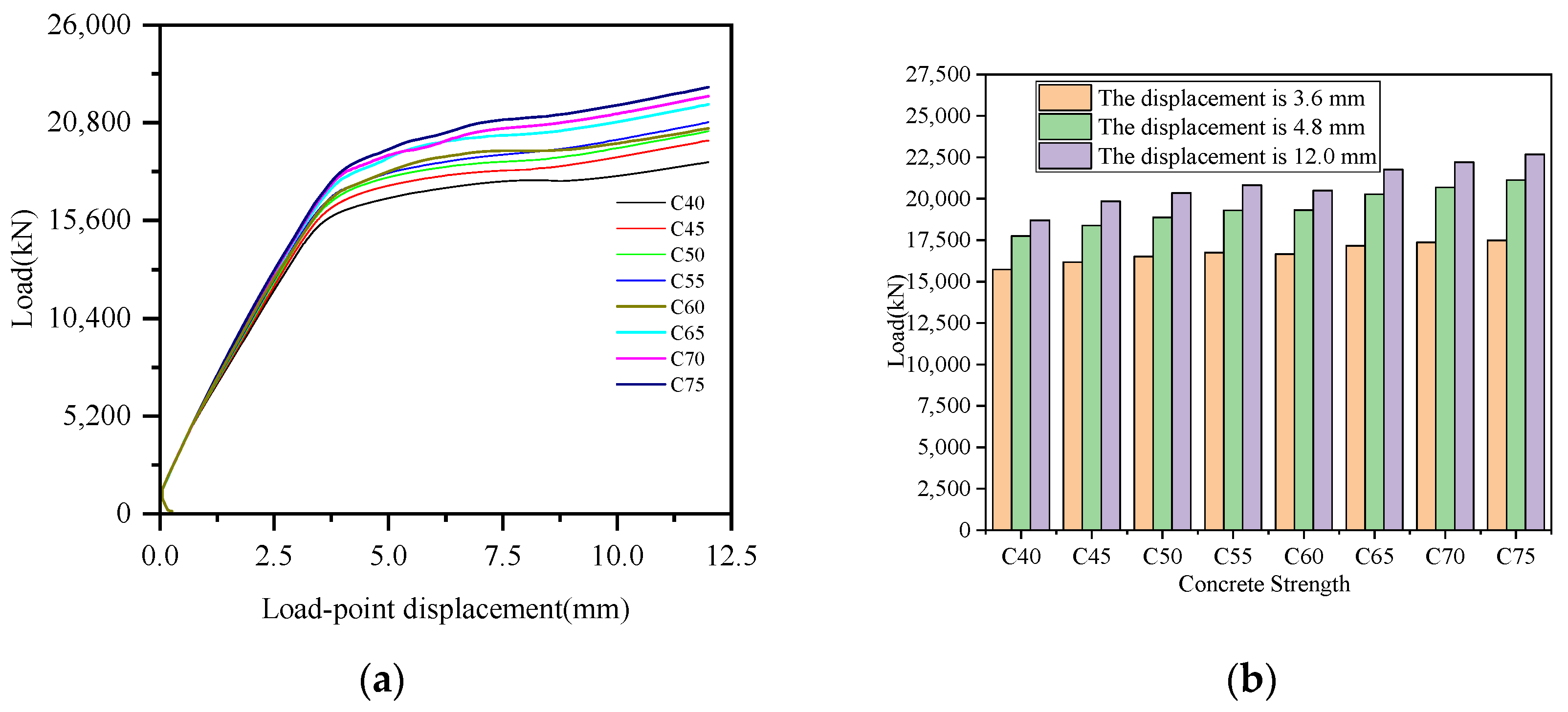

5.4. Strength Grade of Steel and Concrete

6. Design Method

6.1. Local Bearing Capacity

6.2. Force Equilibrium of the Joint

6.3. Stress State of Concrete in the Joint Core Region

6.4. Analysis of Construction Sequence and Corresponding Load Stages

- (1)

- First Stage

- (2)

- Second Stage

- (3)

- Third Stage

- (4)

- Fourth Stage

- (5)

- Fifth Stage

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- A novel configuration for a concrete-filled steel tube arch-column-tie beam joint is proposed. The joint exhibits a rational design and reliable mechanical performance. Through finite element simulation, it can be observed that the joint remains elastic under the design load for both conditions, including the presence of prestressed high-strength rods and the failure of the rods, meeting the design requirements. The joint reaches its ultimate capacity when extensive yielding occurs in the tie beam along the junction region with the circular arch beam, as well as in the steel tube of the arch beam. At this stage, the steel plates and concrete within the joint zone remain elastic, ensuring reliable load transfer.

- (2)

- The maximum computed load of the model with prestressed rods is 2.28 times the design load. The absence of prestressed rods leads to a significant expansion of the high-stress zone within the web of the tie beam. At the ultimate state, the maximum equivalent plastic strain increases by 1.93 times, whereas the stress at the stress concentration point on the circular arch beam above the tie beam decreases by 18%. Consequently, the absence of the rods decreases the joint’s stiffness at yielding by 12.4%, but its effect on the maximum bearing capacity is limited, resulting in merely a 2.2% reduction.

- (3)

- The wall thickness of the circular arch beam steel tube is the key parameter controlling the bearing capacity of this joint. Gradually increasing the wall thickness of the arch beam’s steel tube shifts the failure mode from arch-beam-dominated yielding to tie-beam-dominated yielding along the junction region. Increasing the steel strength grade is more efficient in enhancing the bearing capacity than increasing the concrete strength grade.

- (4)

- The joint zone should be designed based on three aspects: local stress transfer at the bottom of the arch beam, force equilibrium between the arch beam and the tie beam, and the biaxial compression state of the concrete in the joint zone. The rational construction process lies in first establishing a prestressed self-balancing system, then installing the main load-bearing arch, and finally applying the service load. The stress state of the arch structure should be calculated step by step based on the arch forming process to ensure construction safety and achieve the arch structure’s function.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, Y.; Dong, W. A review on spatial tubular joints of steel pipe structures. Eng. Constr. 2014, 28, 10–11+29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Choo, Y.S.; Qian, X.D.; Wardenier, J. Effects of boundary conditions and chord stresses on static strength of thick-walled CHS K-joints. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2006, 62, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Zavvar, E. Stress Concentration factors induced by out-of-plane bending loads in ring-stiffened tubular KT-joints of jacket structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 91, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Peng, P.; Zhu, Z.; Ao, X.; Xiong, S.; Huang, J.; Zhou, L.; Bai, X. Axial tensile experiment of the lap-type asymmetric k-shaped square tubular joints with built-in stiffeners. Buildings 2025, 15, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Contento, A.; Chen, B. Experimental and numerical analysis of force transfer mechanisms in joints of concrete-filled steel tube truss arch bridge. Eng. Struct. 2025, 341, 120784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gao, L.; Zheng, K.; Shi, J. Mechanical behavior of a novel steel-concrete joint for long-span arch bridges-application to yachi river bridge. Eng. Struct. 2022, 265, 114492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafimandimby, M.N.H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Numerical analysis of novel concrete filled K joints with different brace sections. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Hao, J.; Xu, Z.; Tong, G. Experimental and numerical investigation of large-scale truss complex chord joint under multi-axis loading. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, S.T.; Lee, C.K.; Chiew, S.P.; Shao, Y.B. Validation of surface crack stress intensity factors of a tubular K-joint. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2005, 82, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, A.; Nussbaumer, A. Experimental study on the fatigue behaviour of welded tubular K-joints for bridges. Eng. Struct. 2006, 28, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaumer, A.; Costa Borges, L.A. Size effects in the fatigue behavior of welded steel tubular bridge joints. Mater. Werkst. 2008, 39, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Asoodeh, S. Parametric study of geometrical effects on the degree of bending (DoB) in offshore tubular K-joints under out-of-plane bending loads. Appl. Ocean Res. 2016, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Fam, A.; Liu, B.; Pu, B.; Zhao, R. Experimental and numerical analyses on stress concentration factors of concrete-filled welded integral K-joints in steel truss bridges. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 183, 110347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Hosaka, T.; Isoe, A.; Ichikawa, A.; Mitsuki, K. Experiments on concrete filled and reinforced tubular K-joints of truss ggirder. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2004, 60, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Fenu, L.; Chen, B.; Briseghella, B. Experimental study on K-joints of concrete-filled steel tubular truss structures. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2015, 107, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Fenu, L.; Chen, B.; Briseghella, B. Experimental study on joint resistance and failure modes of concrete filled steel tubular (CFST) truss girders. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 141, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Ma, T.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, H. Flexural behavior of concrete-filled rectangular steel tubular (CFRST) trusses. Structures 2022, 36, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansperger, T.; Jung, R. Tied arch bridge of the saale-elster-viaduct-the fastest of its kind in the German railroad network. Stahlbau 2015, 84, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Su, M.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.F. New songhua river bridge: A continuous girder, tied arch, hybrid bridge with four rail tracks in harbin, China. Struct. Eng. Int. 2016, 26, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, B.; Zhang, W. Experimental and numerical investigation of an arch-beam joint for an arch bridge. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2023, 23, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Cai, J.; Zhu, D.; Chen, X. Research on mechanics performance of the large-span arch multi-storied transfer structure. In Proceedings of the 9th National Conference on Basic Theory and Engineering Application of Concrete Structures, Dalian, China, 2–5 November 2006; pp. 391–395. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, S.; Pan, W. Research on the construction method and key technologies of large-span tie arch skybridges. Prog. Steel Build. Struct. 2023, 25, 99–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Ye, Y.; Wen, P.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, L.; Liang, J. Structural design of poly longmen plaza. Build. Struct. 2023, 53, S263–S268. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.L.; Dou, C. Out-of-plane elastic buckling and elastic-plastic stability design method of spatial truss arches. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 15, 1–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Pi, Y.L.; Zhang, S.M. In-plane nonlinear stability bearing capacity of circular concrete-filled steel tubular arches. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 39, 34–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.Y.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Chen, F.; Lin, F. Structural analysis and design of Shenzhen Qianhai Museum. Build. Struct. 2024, 54, 19–24+39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.H. Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures: Theory and Practice; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2004. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. Research on Mechanism of Concrete-Filled Steel Tubes Subjected to Local Compression; Fuzhou University: Fuzhou, China, 2005. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, K.A.; Mahamid, M.; Hariri-Ardebili, M.A.; Tort, C.; Ford, T. Parameter selection for concrete constitutive models in finite element analysis of composite columns. Buildings 2023, 13, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosatko, A.; Winnicki, A.; Polak, M.A.; Pamin, J. Role of dilatancy angle in plasticity-based models of concrete. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2019, 19, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoroff, F. Description of anisotropic damage application to elasticity. In Physical Non-Linearities in Structural Analysis; Hult, J., Lemaitre, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; pp. 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbat, B.G.; Russell, H.G. Friction Coefficient of Steel on Concrete or Grout. J. Struct. Eng. 1985, 111, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaqus Analysis User’s Guide, Version 6.14; Dassault Systèmes: Providence, RI, USA, 2014.

| Plate Thickness or Nominal Diameter/mm | Strength Grade | Yield Stress/N/mm2 | Peak Stress/N/mm2 | Elastic Modulus/N/mm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | Q420 | 491 | 631 | 196,333 |

| 16.7 | Q420 | 528 | 682 | 179,875 |

| 10 | Q420 | 498 | 662 | 217,666 |

| 13.3 | Q420 | 449 | 579 | 219,666 |

| 39 (Steel rods) | 12.9 | 1080 | 1200 | 210,000 |

| Ψ | ϕ | fbo/fco | K | Viscosity Parameter | Ec | ρ (kg/m3) | υ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0.1 | 1.16 | 0.6667 | 0.0005 | 36,000 | 2.5 × 103 | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Su, X.; Zuo, Z.; Huang, L.; Zhou, Y. Mechanical Performance of Joints with Bearing Plates in Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Arch-Supporting Column-Prestressed Steel Reinforced Concrete Beam Structures: Numerical Simulation and Design Methods. Buildings 2026, 16, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010216

Li C, Su X, Zuo Z, Huang L, Zhou Y. Mechanical Performance of Joints with Bearing Plates in Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Arch-Supporting Column-Prestressed Steel Reinforced Concrete Beam Structures: Numerical Simulation and Design Methods. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010216

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chongyang, Xianggang Su, Zhiliang Zuo, Lehua Huang, and Yuezhou Zhou. 2026. "Mechanical Performance of Joints with Bearing Plates in Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Arch-Supporting Column-Prestressed Steel Reinforced Concrete Beam Structures: Numerical Simulation and Design Methods" Buildings 16, no. 1: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010216

APA StyleLi, C., Su, X., Zuo, Z., Huang, L., & Zhou, Y. (2026). Mechanical Performance of Joints with Bearing Plates in Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Arch-Supporting Column-Prestressed Steel Reinforced Concrete Beam Structures: Numerical Simulation and Design Methods. Buildings, 16(1), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010216