1. Introduction

Schoolchildren spend a large part of their day in school buildings, where indoor environmental quality (IEQ)–including indoor air quality (IAQ) and thermal comfort–shapes their exposure to indoor pollutants, airborne pathogens, and thermal conditions. Indoor carbon dioxide (CO

2) concentrations in classrooms primarily increase due to human respiration, as exhaled air contains substantially higher CO

2 levels than outdoor air, which typically exhibits a background concentration of approximately 420 ppm [

1]. Consequently, indoor CO

2 serves as a practical indicator of ventilation adequacy and the balance between occupant-related emissions and outdoor air supply. CO

2 concentrations below 1000 ppm are generally considered hygienically safe, whereas concentrations above 2000 ppm are classified as unacceptable [

2,

3]. The effectiveness of ventilation in improving IAQ depends not only on air exchange rates but also on the quality of the supplied outdoor air. While outdoor air is typically cleaner with respect to CO

2 and airborne infectious particles, its particulate matter (PM) load may vary substantially depending on the surrounding environment. Mechanical ventilation systems can reduce indoor exposure to outdoor particulate matter through air filtration, whereas natural window airing introduces outdoor air without filtration. Reports from the German Environment Agency indicate that pupils and teachers frequently experience headaches, fatigue, lack of concentration, eye irritation, and upper respiratory tract symptoms associated with time spent in school environments [

4]. Several international studies show that ventilation rates in school classrooms are often inadequate, as indicated by CO

2 concentrations frequently exceeding 1000 ppm [

5,

6,

7,

8]. This problem is particularly pronounced in classrooms without mechanical ventilation during the heating season, when windows tend to remain closed to maintain thermal comfort [

9]. A review of 125 studies in naturally ventilated primary schools found that 81% of classrooms exceeded the 1000 ppm CO

2 threshold, with CO

2 correlating with PM, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and microbial loads [

5]. A European research project reported that poor IAQ in schools (including inadequate ventilation, elevated CO

2, VOCs, particulate matter, and indicators of dampness) was associated with respiratory symptoms and reduced well-being in children [

7].

Traditionally, ventilation research in schools has emphasized cognitive performance, with lower CO

2 repeatedly linked to improved attention and academic outcomes [

10,

11], and comfort-related aspects of IEQ, such as temperature, humidity, draught, and acoustics. Comfort studies show that ventilation mode and window-opening behavior shape thermal sensation and perceived draught [

12,

13]. Beyond performance and comfort aspects, upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) are highly prevalent worldwide, usually mild and self-limiting, and most commonly manifest as the common cold [

14]. Despite their relevance, only a limited number of school-based studies integrate questionnaires on symptoms of URTIs. The WURSS-K (Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey for Kids) provides a child-appropriate instrument for evaluating acute respiratory illness [

15]. A study in Poland linked PM exposure to higher frequencies of respiratory symptoms in over 1400 Polish children [

16], a study in northern Thailand reported impaired lung function among primary schoolchildren exposed to high ambient PM

2.5 concentrations [

17]. Besides air pollutants, airborne pathogens represent an additional major determinant of respiratory morbidity in classrooms, where high occupancy and limited ventilation facilitate both pollutant accumulation and infection transmission. Interest in ventilation increased markedly during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, with sufficient air dilution and appropriate distribution recognized as key mitigation strategies [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. CO

2 concentrations can serve as an indicator of relative airborne infection risk [

24], provided no air purifier is operating in the room. A review on airborne infection risks in schools concluded that IAQ is often inadequate and that reliable natural or mechanical ventilation is essential for mitigating airborne transmission [

8]. In classrooms where window airing is the only option, CO

2 traffic lights (CO

2 measuring devices with a visual feedback) are recommended to support adequate ventilation behavior [

25]. Mechanical ventilation systems with heat recovery can offer controlled and energy-efficient ventilation, increasing outdoor air exchange while maintaining thermal conditions. Decentralized mechanical ventilation units are increasingly considered a practical retrofit solution, supplying continuous outdoor air without requiring ductwork. In 2021, the German Environment Agency recommended that classrooms be progressively equipped with ventilation and air-conditioning systems for reasons of indoor air hygiene and sustainability [

26]. Nevertheless, although Germany has approximately 32,000 general schools [

27], it was estimated that fewer than 10% were equipped with mechanical ventilation systems in 2021 [

28].

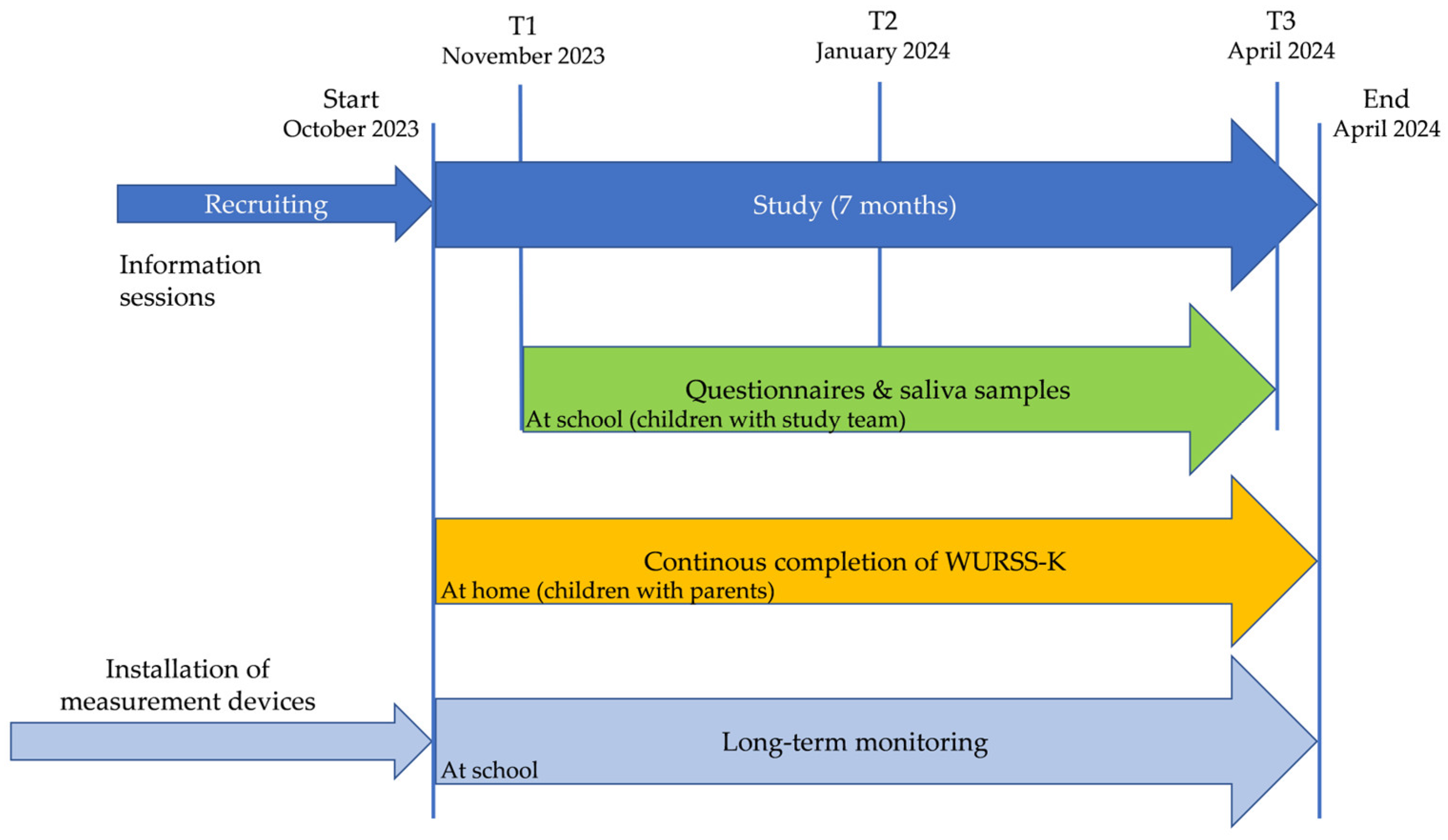

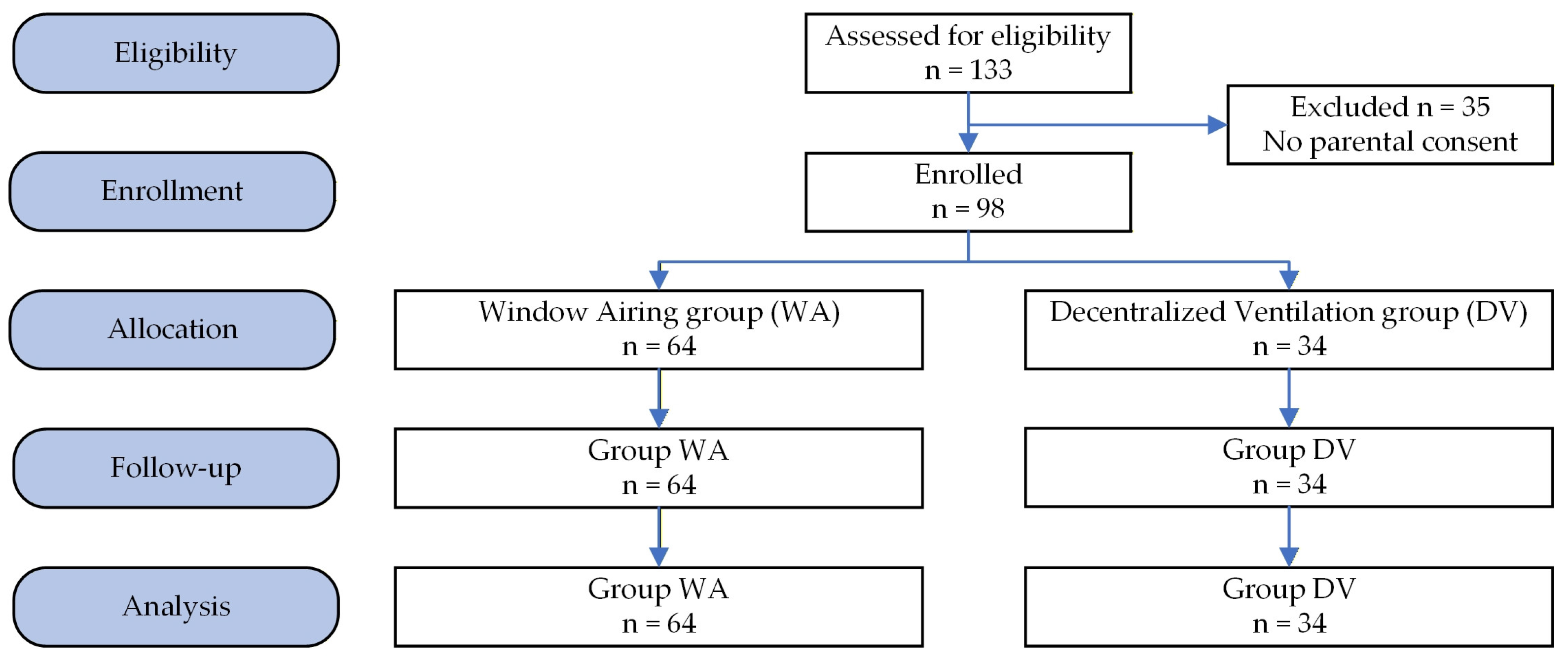

The present controlled observational study investigates differences between manual window airing supported by CO

2 traffic lights and decentralized mechanical ventilation in real-world classroom settings during the winter infection period. A multidimensional approach is applied, combining (i) symptom-based self-assessments of respiratory health, (ii) salivary biomarkers of inflammation and mucosal immunity, (iii) subjective well-being and perceived comfort, and (iv) continuous IEQ monitoring (CO

2, PM

2.5, VOC, temperature, relative humidity). A detailed analysis of the long-term monitoring, including indoor and outdoor environmental data, is presented in [

29]. This integrative study design enables health-related outcomes to be interpreted within the context of classroom exposure conditions and supports the identification of potential environmental confounders, such as particulate matter. By linking medical outcomes with continuous environmental monitoring, the study adds a health-centered perspective to school ventilation research. It offers new insights into the potential health and comfort implications of decentralized mechanical ventilation and highlights the value of integrating subjective assessments, physiological markers, and continuous environmental measurements in school-based field studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Results

The WURSS-K outcomes showed a clear and consistent pattern indicating lower illness burden, functional impairment, and illness duration in group DV compared to group WA. Notably, several parameters–including maximum global total score, maximum global illness severity, maximum functional impact, and sick days–showed statistically significant group differences, while all remaining parameters demonstrated effects pointing in the same direction. This convergence across multiple symptom domains suggests that decentralized ventilation may be associated with a measurably milder subjective illness experience in school-aged children. The consistency of these findings is further supported by the epidemiological indicators, including a lower infection rate (absolute risk reduction of 7.8%) in group DV. Together, the symptom-based and epidemiological measures strengthen the interpretation that mechanical ventilation may contribute to reduced perceived illness severity. Although the WURSS-K was defined as the primary outcome of the study, the analyses of its individual symptom domains must be interpreted with caution. The instrument as a whole served as the predefined primary endpoint, whereas the evaluation of multiple correlated subparameters is inherently exploratory. Nonetheless, the consistent direction of effects across all domains–including several statistically significant group differences–supports the robustness of the overall pattern favoring decentralized ventilation.

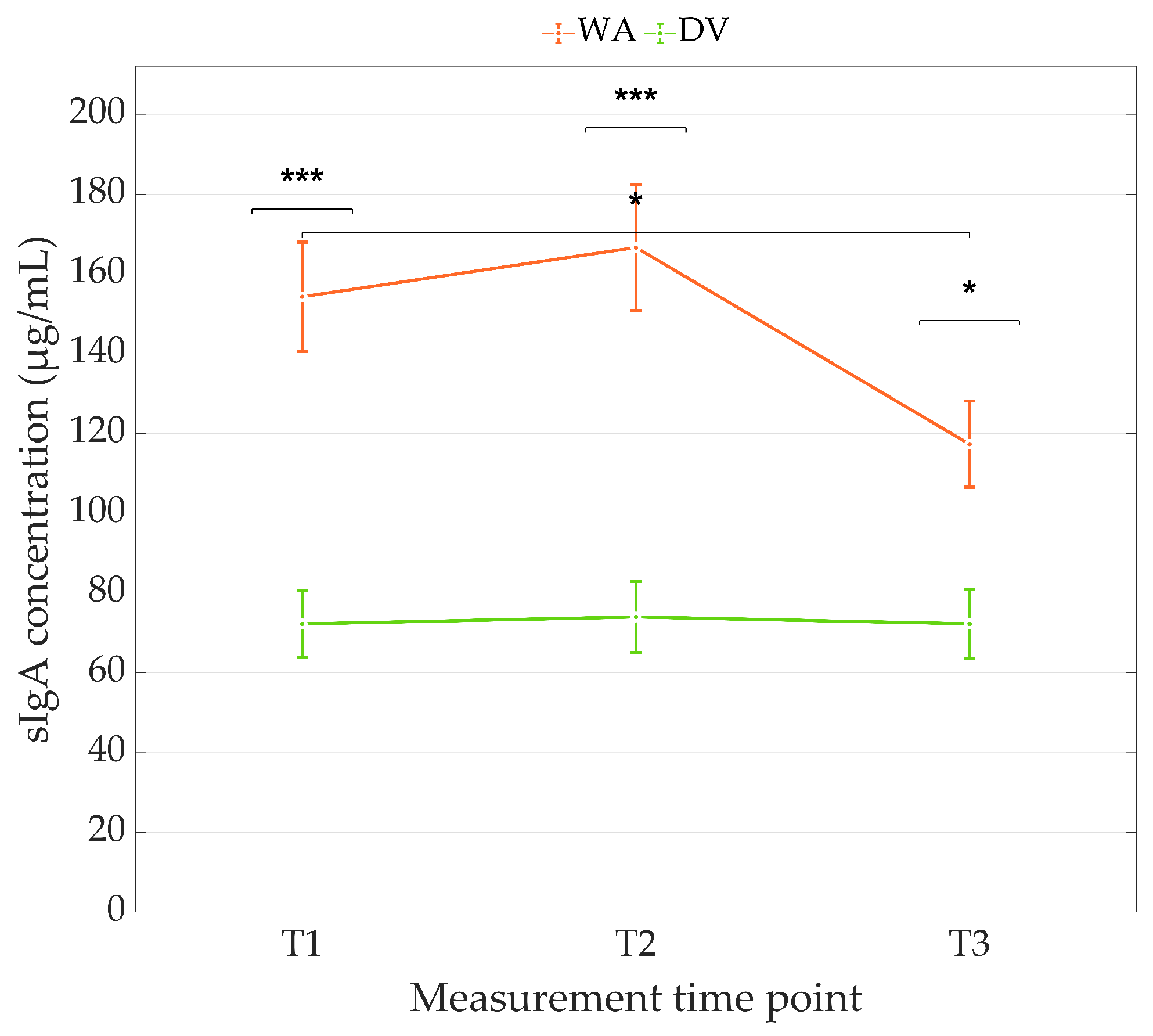

To complement the symptom-based self-assessment, the salivary biomarkers sCRP and sIgA were examined, as they offer objective measures of inflammatory responses and mucosal immune activity. sCRP levels did not differ significantly between ventilation groups and showed no systematic variation over time. The absence of group, time, or interaction effects indicates that low-grade inflammatory activity, as reflected by sCRP, was not meaningfully influenced by the indoor environmental conditions. Given the low concentrations typical for healthy children and the high inter-individual variability of sCRP, these null findings are consistent with its limited sensitivity to moderate environmental fluctuations.

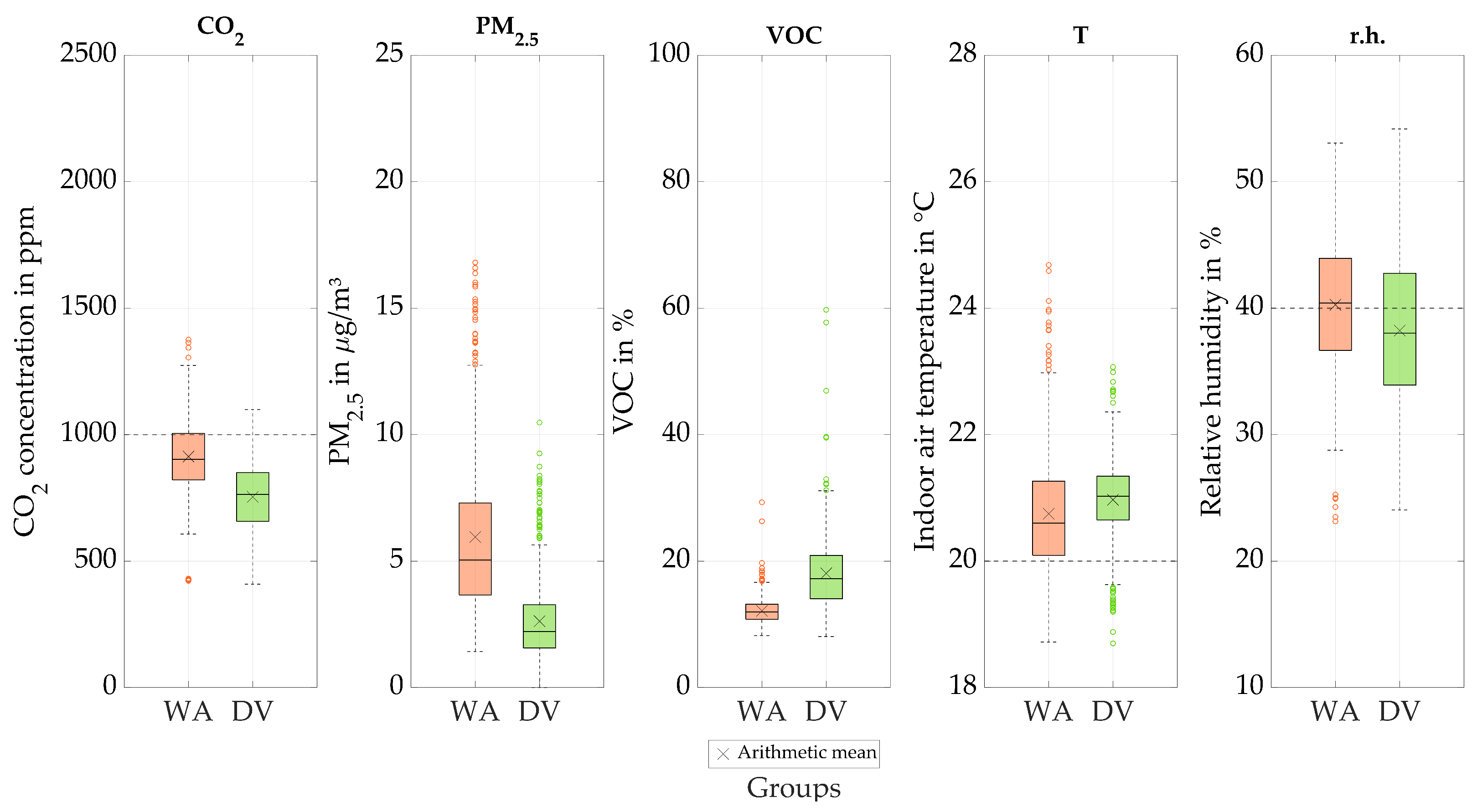

In contrast, the primary analysis of sIgA revealed clear and consistent group differences: children in mechanically ventilated classrooms showed significantly lower sIgA concentrations across all three time points, and these differences remained robust after FDR correction. This pattern may reflect reduced antigenic stimulation in mechanically ventilated rooms, which exhibited markedly lower CO2 and PM2.5 levels in the long-term monitoring. Reduced exposure to airborne pollutants and potentially infectious particles could plausibly diminish mucosal immune activation and thereby lower sIgA secretion.

The sensitivity analysis supports this interpretation. When indoor-environmental parameters were added individually as covariates, most did not affect the group differences. Both PM2.5 and CO2 were positively associated with sIgA, indicating that higher exposures predicted higher mucosal immune activity. However, only the inclusion of PM2.5 eliminated the group effect, suggesting that particulate exposure is a key environmental factor linking the ventilation concept with sIgA levels. The substantially lower PM2.5 concentrations in mechanically ventilated classrooms therefore offer a coherent explanation for the lower sIgA levels observed in group DV.

These findings align with previous research showing associations between particulate matter exposure and respiratory symptoms in children. Prior work using the WURSS-K has linked higher PM levels to increased respiratory symptom scores in school-aged populations [

16]. The present study extends this evidence by integrating repeated symptom assessments with salivary biomarker data and continuous exposure monitoring, providing a comprehensive and temporally resolved perspective under real-world school conditions.

To complement these immune-related findings with a broader psychosocial perspective, general subjective well-being was assessed using the WHO-5 questionnaire. No significant differences in WHO-5 well-being scores were observed between classrooms with and without mechanical ventilation, nor did well-being change systematically over time. Overall, these findings suggest that the ventilation concept did not markedly influence general subjective well-being as measured by the WHO-5. Because the WHO-5 reflects broad psychosocial well-being rather than immediate indoor-environmental perceptions, a more targeted assessment of comfort was needed to examine potential links between ventilation strategy and subjective experience.

Subjective comfort ratings obtained with the Comfort-13 questionnaire were largely consistent with the objectively monitored indoor environmental conditions. Long-term monitoring showed that classrooms with decentralized ventilation exhibited higher indoor air temperatures, lower CO2 concentrations, and substantially reduced PM2.5 levels, while relative humidity tended to be lower (frequently remaining below the recommended minimum level of 40%) and VOC levels were higher than in window-aired classrooms. These environmental patterns aligned well with several descriptive trends in the self-reported comfort data. Children in group DV reported warmer thermal impressions and slightly less draught sensation, consistent with the higher temperatures and reduced window-opening durations. Conversely, participants in group WA more frequently reported cooler sensations and cold extremities, which correspond to the objectively lower temperatures and the more intensive window airing that also explains their higher draught ratings. Perceived air quality was descriptively better in group DV, mirroring its markedly lower CO2 levels. The elevated VOC concentrations in DV, however, did not translate into poorer subjective air-quality ratings, suggesting that concentrations remained below perceptual thresholds or were overshadowed by other comfort cues such as warmth and low CO2. Acoustic comfort was comparable across groups, with no indications that decentralized ventilation units contributed to noise. Reported disturbances primarily arose from regular classroom activity in both groups or heating noise in group WA, which reflects the operation of radiators. Finally, isolated procedural factors–such as open windows during questionnaire completion at some time points–may have transiently influenced thermal or draught perceptions, but do not alter the overall pattern of results and reflect typical conditions in everyday school life.

4.2. Strenghts and Novelty

A key strength of this study lies in its integrative, real-world design, which combines repeated health assessments and salivary biomarkers with continuous long-term monitoring of IEQ in occupied classrooms. Whereas previous school studies typically focused either on IEQ parameters or on health-related outcomes, the present work integrates these domains within a single analytical framework. This multidimensional approach allows subjective symptoms, mucosal immune markers, and objective exposure data to be interpreted jointly rather than in isolation. A major advantage of this design is the ability to incorporate classroom-level environmental covariates into the statistical models and to explore potential exposure-related mechanisms. The sensitivity analyses showed that the association between ventilation concept and mucosal immune activity was largely driven by PM2.5. After adjustment for PM2.5, the group effect on sIgA disappeared, highlighting particulate exposure as a key environmental factor and shifting the interpretation toward exposure-related pathways. To our knowledge, this PM2.5-mediated pathway linking ventilation concept with mucosal immune responses has rarely been demonstrated in school-based field studies under real operating conditions. Ecological validity is further strengthened by conducting the study during regular school operation and the winter infection season. The convergence of objective IEQ measurements with children’s comfort perceptions enhances the internal coherence of the results and supports their practical interpretability. Finally, the use of a validated symptom instrument (WURSS-K), repeated measurements over time, and mixed-effects modelling accounting for inter-individual variability increases statistical robustness. Taken together, these strengths demonstrate that the present study advances existing research by providing integrated, health-centered evidence on the relationships between ventilation concepts, indoor environmental quality, comfort, and respiratory health in schools.

4.3. Constraints and Limitations

Several methodological constraints should be considered when interpreting the findings. The study followed an observational, non-randomized design determined by existing school infrastructure, which may introduce unmeasured confounding; therefore, causal inferences cannot be drawn. The overall sample size was modest, reducing power for detecting small effects. Despite the modest sample size, the longitudinal repeated-measures design and the integration of continuous IEQ monitoring increased statistical efficiency and allowed detection of effects of moderate magnitude under real-world school conditions. Classrooms with central mechanical ventilation could not be included due to insufficient participation and inconsistent ventilation operation, resulting in unequal group sizes and an imbalanced study design. Inter-individual variability in symptom perception and immune responsiveness is an inherent characteristic of pediatric research and cannot be fully controlled. In the present study, repeated measurements and linear mixed-effects models with subject-specific random intercepts were used for the biomarker analyses to account for between-child variability. Nevertheless, residual heterogeneity between children may have contributed to unexplained variance and limits conclusions at the individual level. Several outcomes relied on self-reported measures from children and may therefore be affected by subjective interpretation and situational influences. This also applies to the WURSS-K symptom scores, which, despite showing a consistent pattern across groups, are inherently variable and may not fully capture day-to-day symptom fluctuations. Subjective outcomes may also be influenced by expectation bias, as blinding of participants and teachers was not possible. Indoor environmental parameters were measured only within the school setting, whereas exposures and activities outside school were not captured, although they may also influence respiratory symptoms and immune responses.

Finally, the generalizability of the findings is influenced by climatic and operational context. The study was conducted in a temperate climate during the heating season, which strongly affects window-opening behavior and thermal comfort. Accordingly, the applicability of manual window airing may differ in warmer or colder climates. In contrast, the decentralized mechanical ventilation system provided a norm-compliant outdoor air volume flow in accordance with DIN EN 16798-1 (IEQ category II) for the investigated classroom sizes. One classroom was operated with a constant air volume flow, while the second was switched to demand-controlled operation based on CO2 concentration during the study, without compromising compliance with the targeted ventilation requirements. This indicates that the underlying mechanical ventilation concept is, in principle, transferable to other climatic regions when appropriately designed and operated. Moreover, the integrative methodological approach applied in this study is independent of climate and can be readily transferred to investigations conducted under different climatic and regulatory conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study indicates that decentralized mechanical ventilation may provide health- and comfort-related benefits for schoolchildren. The primary outcome, the WURSS-K, showed a consistent pattern of milder subjective illness experiences in mechanically ventilated classrooms. Mucosal immune activity also differed between ventilation concepts, with lower sIgA levels observed in mechanically ventilated classrooms. Although causal inferences cannot be drawn from this observational study, converging evidence from the primary analyses, sensitivity analyses and long-term monitoring of IEQ parameters indicates that ventilation-related differences in particulate exposure (PM2.5) may influence mucosal immune responses. Children’s comfort perceptions aligned well with the objectively measured indoor environmental conditions. Mechanically ventilated classrooms exhibited warmer and more stable thermal environments during the heating period, significantly lower CO2 and PM2.5 concentrations and slightly more favorable thermal and draught-related impressions, although relative humidity was frequently below recommended levels. Importantly, children did not report any acoustic disadvantages related to decentralized mechanical ventilation. These findings suggest that decentralized mechanical ventilation can enhance health and perceived comfort while supporting favorable indoor environmental quality.

A particular strength of this study lies in combining medical outcomes with continuous long-term monitoring of indoor environmental quality under real-world school conditions, an approach that remains uncommon in school-based ventilation research. This integrative methodological approach enabled the inclusion of environmental classroom-level covariates and allowed subjective perceptions, immune markers, and objective exposure data to be interpreted jointly. Additional strengths include the use of a validated symptom instrument and the ecological validity afforded by measurements during regular school operation. Comparable levels of detail and multidimensional integration have rarely been applied in school-based research. Future studies should employ larger cohorts and ensure balanced participation across all ventilation groups to further clarify the relationships between ventilation concept, indoor environmental quality, and child health.

From a practical perspective, the findings support decentralized mechanical ventilation as a robust option to improve indoor environmental quality, air hygiene, and perceived comfort in classrooms, particularly during the heating season when window airing alone may be insufficient. At the same time, potential trade-offs related to investment costs, energy use, maintenance requirements, and material-related emissions should be considered during planning and operation, emphasizing the importance of appropriate system design and operation. Operational aspects of mechanical ventilation in the same study setting have been discussed in more detail in a previous monitoring-focused publication [

29]. Overall, ventilation strategies should be selected contextually, balancing air hygiene, comfort, energy efficiency, and operational constraints, and evaluated using integrated approaches that consider both environmental conditions and health-related outcomes.