The Bosch Vault: Reinterpretation and Exploration of the Limits of the Traditional Thin-Tile Vault in the Post-War Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Historical Context

“My friend Bosch Reitg: There will always be those who, like me now, play the role of the long-legged curlew, who gives advice to everyone but none to himself. But I am pleased, as is fortune, to lift up the bold, and therefore I welcome with joy your desire for novelty, even if it is not tempered by healthy restraint and a deep mathematical and experimental study of the structure you advocate.The attempt represents a positive value; if it is not recognized today, do not be discouraged, for tomorrow God will bring the dawn, and we shall prosper”[34].

“Amigo Bosch Reitg: Nunca ha de faltar quien, cual ahora yo, desempeñe el papel de alcaraván zancudo, que da a todos consejos, más para sí ninguno. Pero me place, como a la fortuna, aupar a los audaces, y, por ello, saludo con alborozo su afán de no-vedad, aunque no vaya arrendado por un sano comedimiento y por profundo estudio matemático y experimental de la estructura que propugna.La tentativa representa un valor positivo; si hoy no se reconoce, nada de alebro-narse, que mañana amanecerá Dios y medraremos”[34].

4. Results

4.1. The System and the Patent

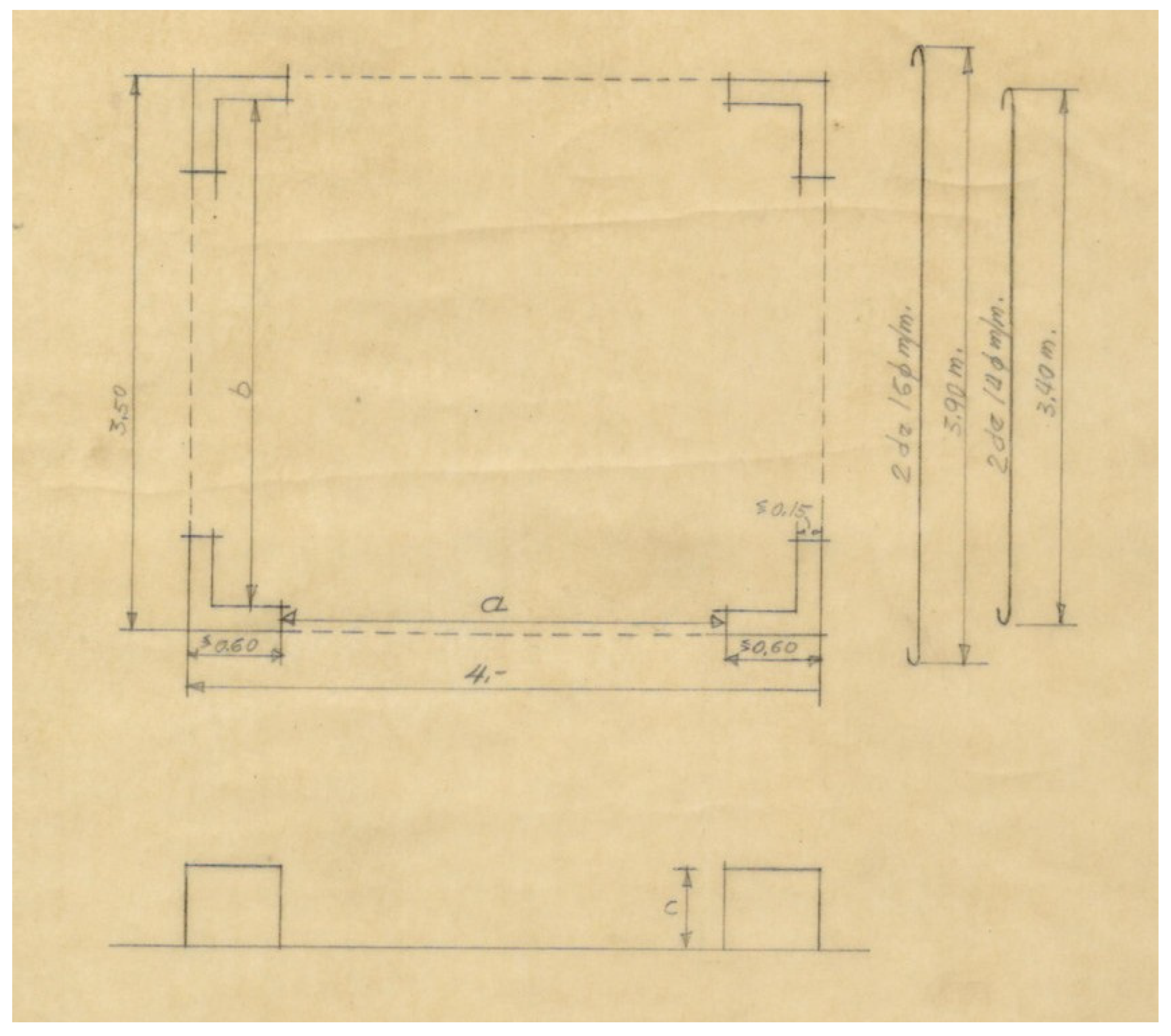

“We assume that the surface area to be covered by the vault is 5 × 3 m, or a total of 15 square metres. The diagonal arch span will be 5.40 metres. The vault will be constructed using medium-sized hollow bricks 4 cm thick, of which we will only consider 3 centimetres for the purposes of the resistant section. We will give the diagonal arch a deflection of 1/10 × L = 54 cm. Therefore, the formwork—generatrix and directrix—will have a deflection of 27 cm. The permanent load will be 100 kg per square metre; and the overload, 150 kg per square metre, i.e., total load per unit, 250 kg per square metre.To find the value of the thrust at the angle, we will use Formula (3).To calculate the iron section, as we indicated at the beginning, we will break down this thrust, according to the diagonal, into two components, according to the sides of the vault; which, when calculated using vectors, gives us: Ha = 1.22 tonnes; Hb = 2.04 tonnes. The iron section to be placed on the shorter side will be:In other words, for bracing, we will place a 12 mm round bar on the shorter sides and a 15 mm round bar on the longer sides.The total surface area of the vault will be = 15 m2.The total weight of iron with fork = 20 kg.The iron per square metre of surface area = 1.33 kg/m2.”[16] (p. 506).

“La superficie a cubrir por la bóveda suponemos que es de 5 × 3 m, o sea en total 15 metros cuadrados. La luz del arco diagonal corresponderá a 5′40 metros. La bóveda la ejecutaremos con ladrillo hueco mediano de 4 cm de espesor, del que solo consideramos 3 centímetros a los efectos de sección resistente. Daremos una flecha al arco diagonal de 1/10 × L = 54 cm. Por tanto, las cimbras—generatriz y directriz—tendrán una flecha de 27 cm. La carga permanente será de 100 kilogramos por metro cuadrado; y la sobrecarga, 150 kilos por metro cuadrado, o sea, carga total por unidad, 250 kilos por metro cuadrado.Para conocer elvalordel empuje en el ángulo haremos uso de la Fórmula (3).Para calcular la sección de hierro, como ya hemos indicado al principio, descompondremos este empuje, según la diagonal, en dos componentes, según los lados de la bóveda; lo que efectuado por vectores nos da: Ha = 1.22 toneladas; Hb = 2′04 toneladas. La sección de hierro a colocar sobre el lado menor será:O sea, para arriostramiento colocaremos un redondo de 12 mm en los lados menores, y un redondo de 15 mm en los lados mayores.La superficie total de la bóveda será = 15 m2.El peso total de hierro con horquilla = 20 kg.El hierro por metro cuadrado de superficie = 1.33 kg/m2.”[16] (p. 506).

“Barcelona.

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

4.2. National Diffusion

- -

- Complex of 300 dwellings in Olot [16] (p. 612, 7).

- -

- Complex of 123 dwellings in Huelva [16] (p. 612, 7).

- -

- Complex of 722 dwellings in Valladolid [16] (p. 612, 7).

- -

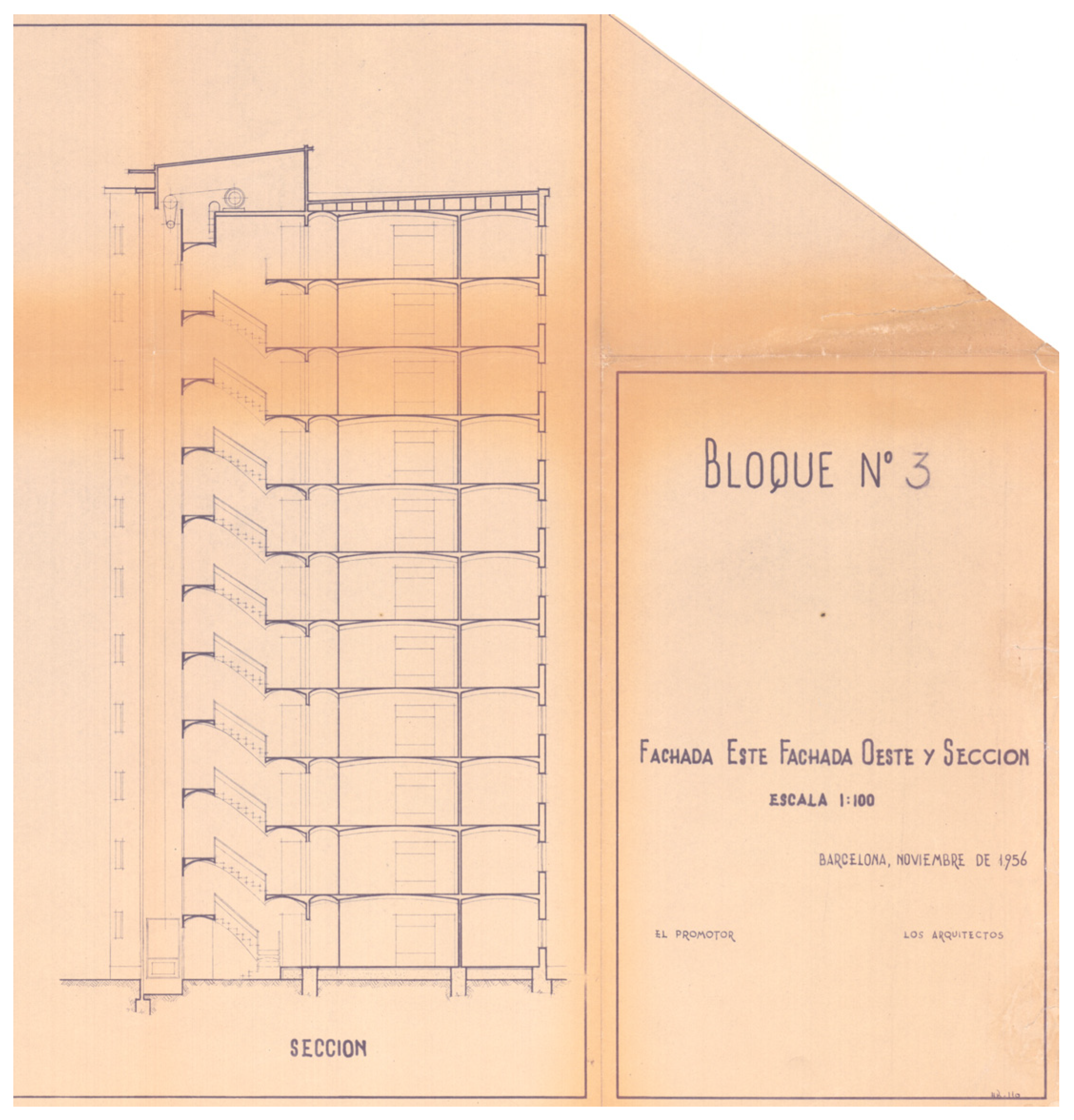

- Other 6- to 8-storey buildings in Barcelona, adding 650 additional homes [16] (p. 612, 5) (Given the date and scale, it is understood that these are homes for SEAT workers in the Zona Franca).

- -

- Groups of 500 and 150 homes in other locations [16] (p. 614, 6 and 7).

4.3. International Diffusion

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

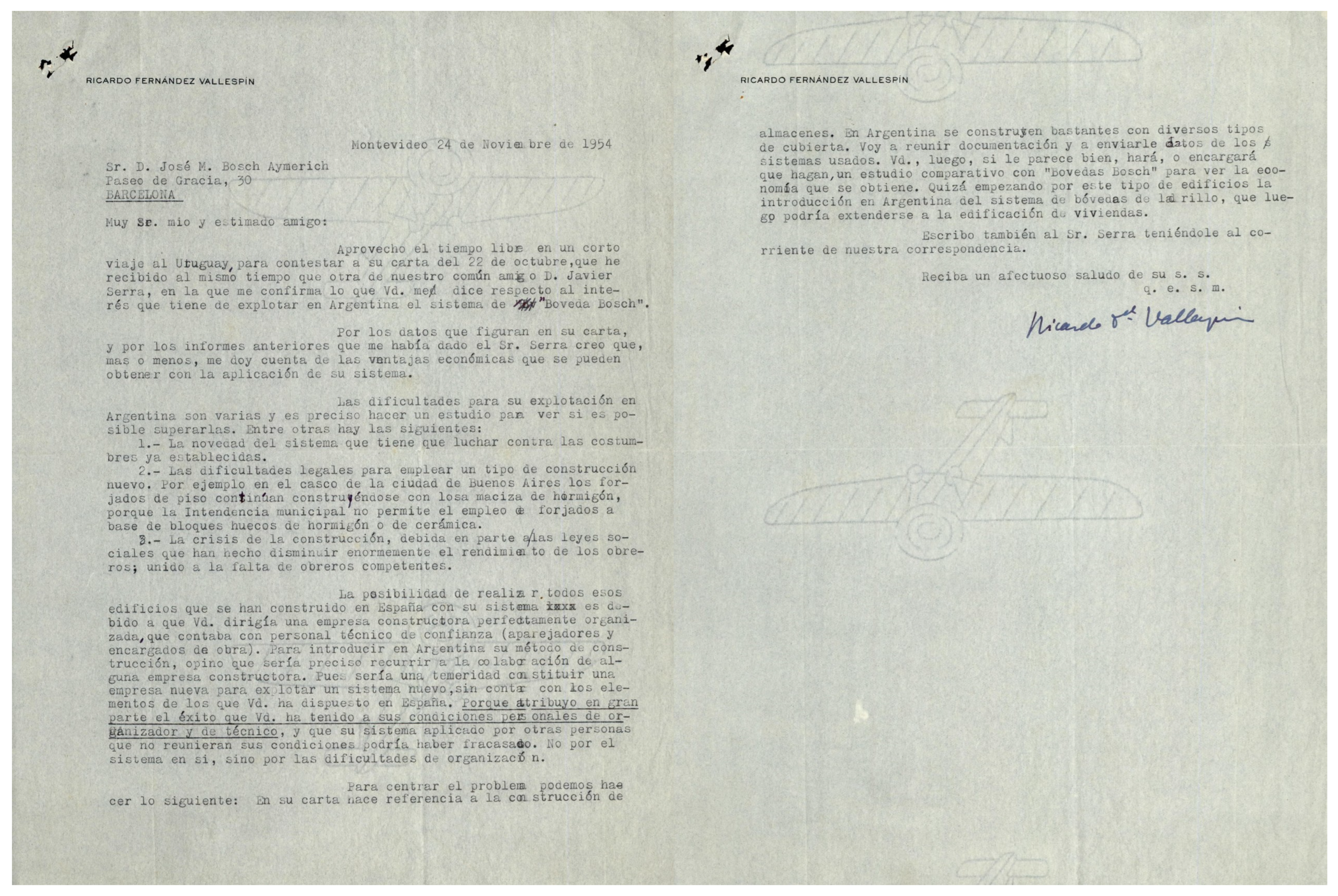

“The possibility of constructing all those buildings that have been built in Spain using your system is due to the fact that you ran a perfectly organized construction company, which had reliable technical staff (quantity surveyors and site managers). In order to introduce your construction method in Argentina, I believe it would be necessary to seek the collaboration of a construction company. It would be reckless to set up a new company to exploit a new system without the resources you have had at your disposal in Spain. I attribute much of your success to your personal qualities as an organizer and technician, and believe that your system, if applied by others who do not meet your standards, could have failed. Not because of the system itself, but because of the difficulties of organization”[16] (p. 520).

“La posibilidad de realizar, todos esos edificios que se han construido en España con su sistema es debido a que Vd. dirigía una empresa constructora perfectamente organizada, que contaba con personal técnico de confianza (aparejadores y encargados de obra). Para introducir en Argentina su método de construcción, opino que sería preciso recurrir a la colaboración de alguna empresa constructora. Pues sería una temeridad constituir una empresa nueva para explotar un sistema nuevo, sin contar con los elementos de los que Vd. ha dispuesto en España. Porque atribuyo en gran parte el éxito que Vd. ha tenido a sus condiciones personales de organizador y de técnico, y que su sistema aplicado por otras personas que no reunieran sus condiciones podría haber fracasado. No por el sistema en sí, sino por las dificultades de organización”[16] (p. 520).

“Regarding brick vaults. It was wonderful that when our war ended, and despite the tremendous difficulties we suffered, all kinds of attempts were made to keep construction going and, therefore, to find whatever solutions were necessary. It is a case similar to that of gas generators in cars. Gas generators were installed because we were not being supplied with gasoline; but once we have gasoline, no one would think of continuing to use gas generators. It seems to me that we are in a similar situation with these vaults, which are absurd in the current circumstances because they have terrible acoustic conditions and because they leave wasted space that weighs down the building”[39].

“Respecto a las bóvedas de ladrillo. Fué [sic] estupendo que al terminarse nuestra guerra, y existiendo aquellas dificultades tan tremendas que padecimos, se hicieran tentativas de todo género para no parar la construcción, y, por tanto, ir a las soluciones que fueran necesarias. Es un caso análogo al del gasógeno en los coches. Se pusieron gasógenos porque no nos mandaban gasolina; pero una vez que tenemos gasolina, el ir con gasógeno detrás no se le ocurre a nadie. A mi me parece que en un caso semejante estamos con esto de las bóvedas, que en las condiciones actuales son absurdas porque tienen unas malísimas condiciones acústicas y porque dejan unos espacios perdidos que gravan el edificio”[39].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lluis-Teruel, C.; Lluis i Ginovart, J. Construction of structures with thin-section ceramic masonry. Buildings 2025, 15, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza Catalán, A. Hacia una historia de las bóvedas tabicadas. In Construyendo Bóvedas Tabicadas, Actas del Simposio Internacional sobre Bóvedas Tabicadas; Zaragoza, A., Soler, R., Marín, R., Eds.; Editorial de la Universitat Politécnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2012; pp. 11–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lluis i Ginovart, J.; Lluis Teruel, C.; Ugalde-Blázquez, I. Formas de construcción tradicional en la ingeniería militar española. In Proceedings of the Congreso Internacional Icofort, Menorca, Spain, 20–23 October 2021; Available online: https://publicaciones.defensa.gob.es/congreso-internacional-icofort-2021-libros-pdf.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- González Moreno-Navarro, J.L. La bóveda tabicada: Pasado y futuro de un elemento de gran valor patrimonial. In Construcción de Bóvedas Tabicadas; Truñó, A., Huerta, S., González Moreno-Navarro, J.L., Eds.; Instituto Juan de Herrera, Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. xi–lx. Available online: https://archive.org/details/truno-2004.-construccion-de-bovedas-tabicadas/page/n7/mode/2up (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Lluis i Guinovart, J.; Lluis-Teruel, C.; Gómez-Val, R. From the voûte à la Roussillon to the voûte à la notre maniere. The fortune of tile vault in Enlightened France. Inf. Construcción 2023, 75, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsendorf, J. Guastavino Vaulting. The Art of Sturctural Tile; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, J.; Neumann, A.G. The Old World Meets the New. The Guastavino Company and the Technology of the Catalan Vault (1885–1962); Avery Architectural Fine Arts Library: New York, NY, USA; Miriam and Ira, D. Wallach Art Gallery: New York, NY, USA; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bassegoda Nonell, J. La construcción tradicional en la arquitectura de Gaudí. Inf. Construcción 1990, 42, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayo, J. La Bóveda Tabicada. Anu. Asoc. Arquit. Cataluña 1910, 157–184. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell, J. Estructuras de Ladrillo y Hierro Atirantado: En la Arquitectura Catalana Moderna. Anu. Asoc. Arquit. Cataluña 1910, 119–146. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrablo, V.; Roviras, J. Bóvedas cerámicas. Un viaje transatlántico de ida y vuelta. Palimsesto 2019, 19, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López García, E. La mediterraneidad en la obra de Le Corbusier. La bóveda Catalana Le Corbusierana: Influencias y evolución. In Proceedings of the LC2015—Le Corbusier, 50 Years Later, Polytechnic University of Valencia Congress, Valencia, Spain, 18–20 November 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro Trenado, M.A.; Llorens Sulivera, J.; Llorens Sullivera, M. Ignasi Bosch i Reitg (1910–1985): Una patente para construir bóvedas tabicadas. In Construyendo Bóvedas Tabicadas. Actas del Simposio Internacional sobre Bóvedas Tabicadas; Zaragoza, A., Soler, R., Marín, R., Eds.; Editorial de la Universitat Politécnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2012; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro Trenado, M.A.; Cuenca, B. Ignasi Bosch Reitg and the Construction of “Timbrel” Vaults During the Post-War Period in Girona, Catalonia. In Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Construction History, 29 March–2 April 2006; Queens’ College, Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2006. Available online: https://www.arct.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/vol-1-631-640-chamorro.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Arza Garaloces, P. Un viaje a través del papel: La difusión de la producción arquitectónica española en las revistas extranjeras. In Arquitectura Importada y Exportada en España y Portugal (1925–1975): Actas Preliminares; Pamplona 5/6 mayo 2016; T6 Ediciones: Pamplona, Spain, 2016; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Bosch Aymerich Archive. 2012 folder. Project name: Patente sistema estructural para suelos y techos.

- Huerta Fernández, S. Mecánica de las bóvedas tabicadas. Arquit. COAM 2005, 339, 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- López López, D.; Domènech, M. Tile vaults. Structural analysis and experimentation. In 2nd Guastavino Biennial; Diputació de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://cultura.gencat.cat/web/.content/dgpc/temes/el_patrimoni_arquitectonic/Comissio_Gustavino/Guastav_david-marta.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Zaragoza, A.; Soler, R.; Marín, R. (Eds.) Construyendo Bóvedas Tabicadas. Actas del Simposio Internacional sobre Bóvedas Tabicadas; Editorial de la Universitat Politécnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez García, A.; Hernando de la Cuerda, R. La bóveda tabicada y el movimiento moderno español. In Proceedings of the Actas del Quinto Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Burgos, Spain, 7–9 June 2007; pp. 763–773. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta, S. Las bóvedas tabicadas en Alemania: La larga migración de una técnica constructiva. In Proceedings of the Décimo Congreso Nacional y Segundo Congreso Internacional Hispanoamericano de Historia de la Construcción, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 3–7 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.; González, M.; Losada, J.C. Tile vault architecture and construction around Eduardo Sacriste. Inf. Construcción 2012, 64, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons Poblet, J.M.; Arboix-Alió, B. El Decreto sobre las Restricciones del hierro en la edificación. La norma olvidada. Inf. Construcción 2022, 74, e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto por el que se aprueba el Reglamento sobre las restricciones del hierro en la edificación. Bol. Of. Estado 1941, 214, 5848–5853. Available online: https://www.boe.es/datos/pdfs/BOE//1941/214/A05848-05853.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Franco, F. Ley de 23 de Septiembre Creando la Dirección General de Arquitectura. Bol. Of. Estado 1939, 273, 5427. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_gazeta/comun/pdf.php?p=1939/09/30/pdfs/BOE-1939-273.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Dirección General de Arquitectura. Sistemas Especiales de Forjados para la Edificación Tipos Aprobados y Revisados por la Sección de Investigación y Normas; Ministerio de la Gobernación: Madrid, Spain, 1942.

- García-Gutiérrez Mosteiro, J. Bóvedas Tabicadas. In Luis Moya Blanco Arquitecto (1904–1990); Capitel, A., García-Gutiérrez Mosteiro, J., Eds.; Ministerio de Fomento, Electa: Madrid, Spain, 2000; pp. 130–148. [Google Scholar]

- Azpilicueta Astarloa, E. La Construcción de Posguerra en España (1939–1962). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Escuela de Arquitectura, Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aburto Renovales, R. Proyecto de Viviendas en Toledo. Obra Sindical del Hogar. Rev. Nac. Arquit. 1952, 4–5. Available online: https://www.coam.org/es/fundacion/biblioteca/revista-arquitectura-100-anios/etapa-1946-1958/revista-nacional-arquitectura-n125-Mayo-1952 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Aburto Renovales, R. Granja Escuela en Talavera de la Reina. Rev. Nac. Arquit. 1948, 299–306. Available online: https://www.coam.org/es/fundacion/biblioteca/revista-arquitectura-100-anios/etapa-1946-1958/revista-nacional-arquitectura-n80-Agosto-1948 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Bassegoda i Musté, B. La Bóveda Catalana; Discurso leído el 26 de Noviembre de 1946; Barcelona, Spain, 1947; Available at COAC Library. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch Reitg, I. Bóvedas Vaídas Tabicadas. Trabajo para el Concurso Bienal del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Cataluña y Baleares. Turno Científico Constructivo. 27 December 1947; Not Published. Available at COAC Library. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch Reitg, I. La bóveda vaida Tabicada. Rev. Nac. Arquit. 1949, 89, 185–199. Available online: https://www.coam.org/es/fundacion/biblioteca/revista-arquitectura-100-anios/etapa-1946-1958/revista-nacional-arquitectura-n89-Mayo-1949 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Bassegoda i Musté, B. Un aplauso con reservas mentales. Rev. Nac. Arquit. 1949, 91, 332. Available online: https://www.coam.org/es/fundacion/biblioteca/revista-arquitectura-100-anios/etapa-1946-1958/revista-nacional-arquitectura-n91-Julio-1949 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Salazar-Lozano, P. Un Impulso Transatlántico. Canales de Influencia de la Arquitectura Norteamericana en España, 1945–1960. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Navarra, Navarra, Spain, 25 June 2018. Available online: https://dadun.unav.edu/entities/publication/e0b97a35-6507-456e-b493-d6cdd258706b (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Cabrera, A.; Sala, I.; Marguí, M.; Jordi, I.; Collel, J. Les Voltes de Quatre Punts. Estudi Constructiu i Estructural de les Cases Barates; Col.legi D’Aparelladors I Arquitectes Tècnics de Girona, Universitat de Girona I Diputació de Girona: Girona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Bosch Aymerich Archive. T-007 tube.

- Fundación Bosch Aymerich Archive. H130B_1.27 folder.

- de Miguel González, C.; Vivanco Bergamín, L.F.; de Yarza García, J.; Moya Blanco, L.; Fisac Serna, M.; Artiñano Luzárraga, M.; de Aguinaga y Azqueta, E.M.; Gutiérrez Soto, L.; Chueca Goitia, F. Defensa del Ladrillo: Sesión Crítica de Arquitectura celebrada en Madrid el mes de Abril. Rev. Nac. Arquit. 1954, 150, 19–32. Available online: https://www.coam.org/es/fundacion/biblioteca/revista-arquitectura-100-anios/etapa-1946-1958/revista-nacional-arquitectura-n150-Junio-1954 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Piñón Pallarés, H. Reposición de la polémica sobre el realismo. Annals 1983, 3, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Cirici Pellicer, A. La Estética del Franquismo; Editorial G. Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Balldelou, M.A.; Capitel, A. Summa Artis. Historia General del Arte. Vol XL. Arquitectura Española del Siglo XX; Espasa Calpe: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A.A. Bóvedas Tabicadas de Doble y Simple Curvatura. Edificación 1959, 29–48. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/34257/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Gómez, M.A. El Fracaso de la Autarquía: La Política Económica y la Posguerra Mundial (1945–1959). Espac. Tiempo Forma Ser. V Hist. Contemp. 1997, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnoff, C. The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Significance; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ethiopianregistrar.com/files/sgp/crs/row/r45079.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Pizza, A.; Granell, E. (Eds.) Atravesando Fronteras: Redes Internacionales de la Arquitectura Española (1939–1975); Ediciones Asimétricas: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- de San Antonio Gómez, J.C. El viaje desconocido de un arquitecto olvidado. RA Rev. Arquit. 2010, 12, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Apply Date | Approval Date | Quitting Date | Objections | Interferences | Projects * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulgarized | Patent | Geometry | Structure | Material | |||||

| Spain | 24/7/50 | 7/11/50 | - | X | |||||

| Italy | 25/3/52 | 2/12/53 | - | ||||||

| France | 18/3/52 | 30/9/53 | - | X | |||||

| Belgium | 21/2/52 | 15/4/52 | - | ||||||

| Portugal | 15/3/52 | 22/4/52 | - | ||||||

| UK | 25/3/52 | 3/6/54 | - | X | X | X | |||

| Germany | 24/3/52 | - | 21/8/56 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Canada | 18/3/52 | 8/12/53 | - | X | |||||

| Mexico | 19/3/52 | - | 30/4/54 | X | |||||

| Brazil | 26/3/52 | - | 30/4/54 | X | X | ||||

| Uruguay | 1/4/52 | - | 2/6/54 | X | |||||

| EE. UU. | 17/3/52 | - | 10/12/56 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Argentina | - | - | 29/3/55 | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ugalde-Blázquez, I.; Masó-Sotomayor, T.; Morán-García, P. The Bosch Vault: Reinterpretation and Exploration of the Limits of the Traditional Thin-Tile Vault in the Post-War Context. Buildings 2026, 16, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010159

Ugalde-Blázquez I, Masó-Sotomayor T, Morán-García P. The Bosch Vault: Reinterpretation and Exploration of the Limits of the Traditional Thin-Tile Vault in the Post-War Context. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010159

Chicago/Turabian StyleUgalde-Blázquez, Iñigo, Tomás Masó-Sotomayor, and Pilar Morán-García. 2026. "The Bosch Vault: Reinterpretation and Exploration of the Limits of the Traditional Thin-Tile Vault in the Post-War Context" Buildings 16, no. 1: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010159

APA StyleUgalde-Blázquez, I., Masó-Sotomayor, T., & Morán-García, P. (2026). The Bosch Vault: Reinterpretation and Exploration of the Limits of the Traditional Thin-Tile Vault in the Post-War Context. Buildings, 16(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010159