Research on the Optimization Design of Large-Diameter Silo Foundation Piles Based on an Automatic Grouping Genetic Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sensitivity Analysis of Silo Pile Foundation

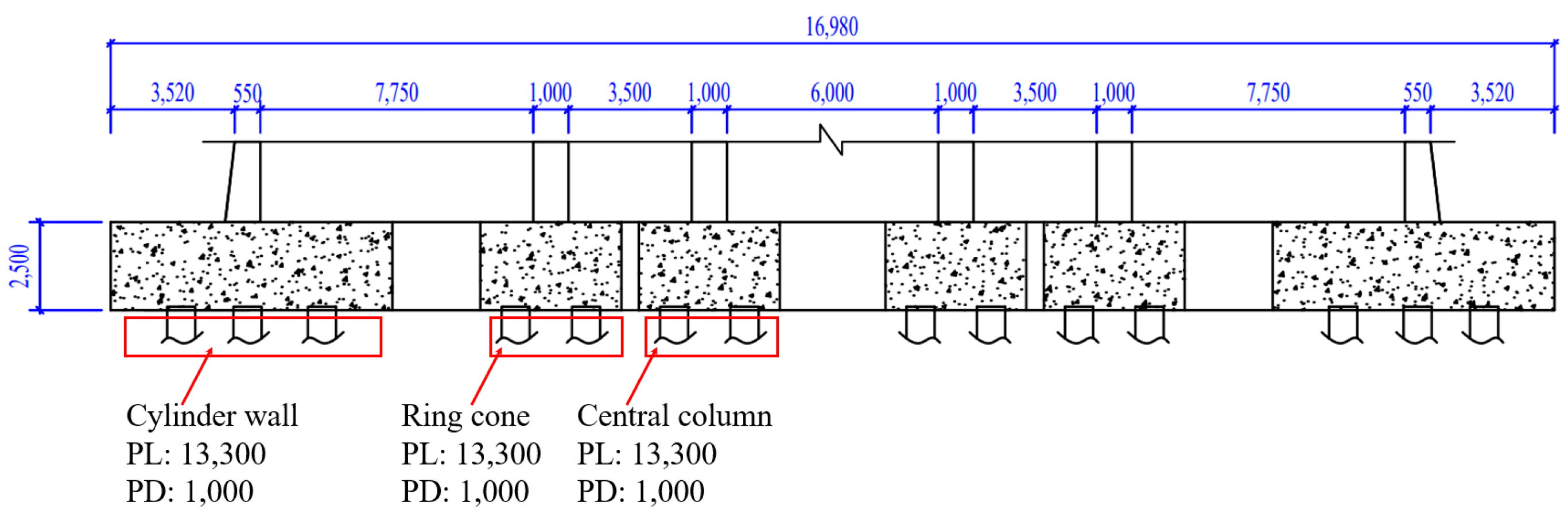

2.1. Test Specimen Description

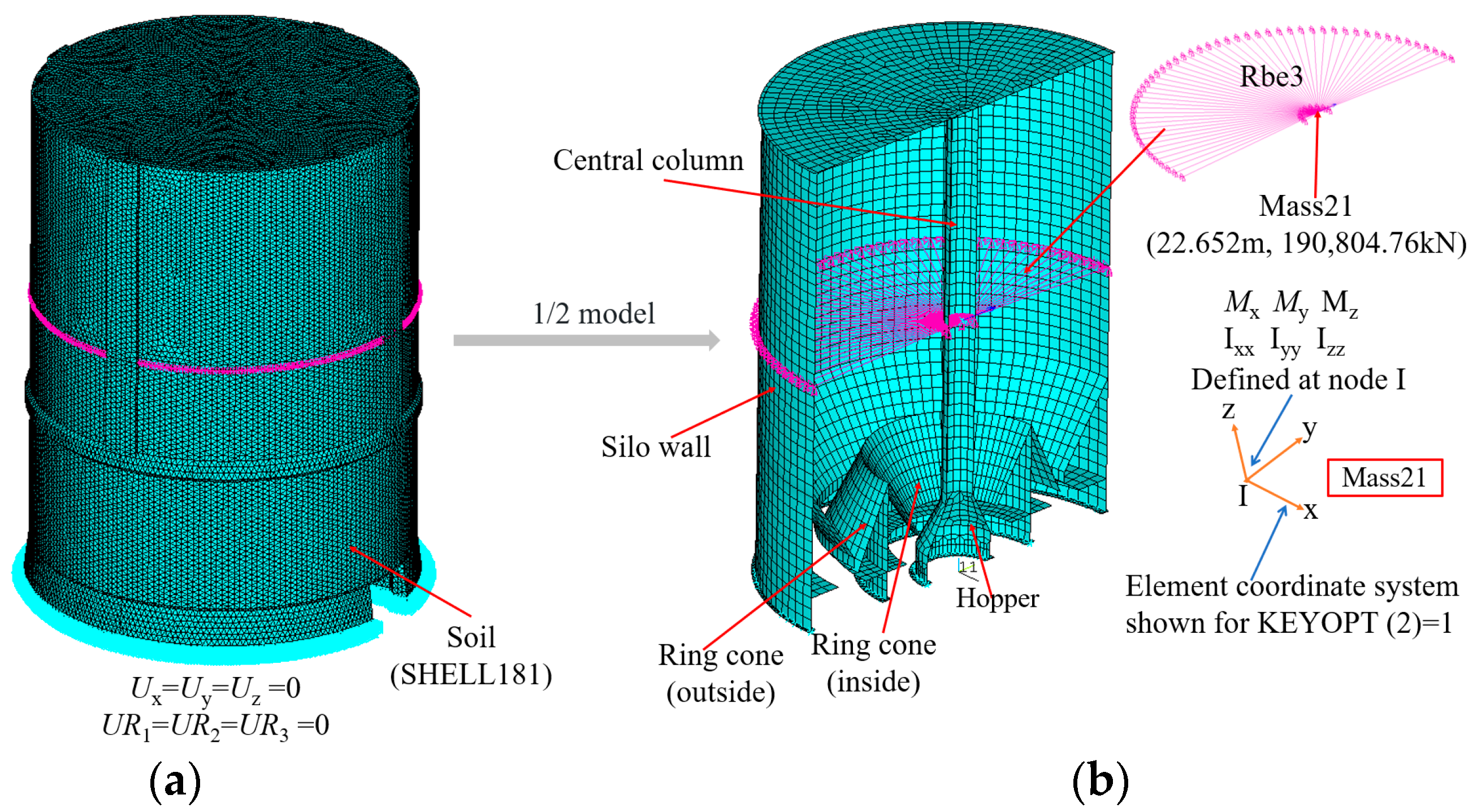

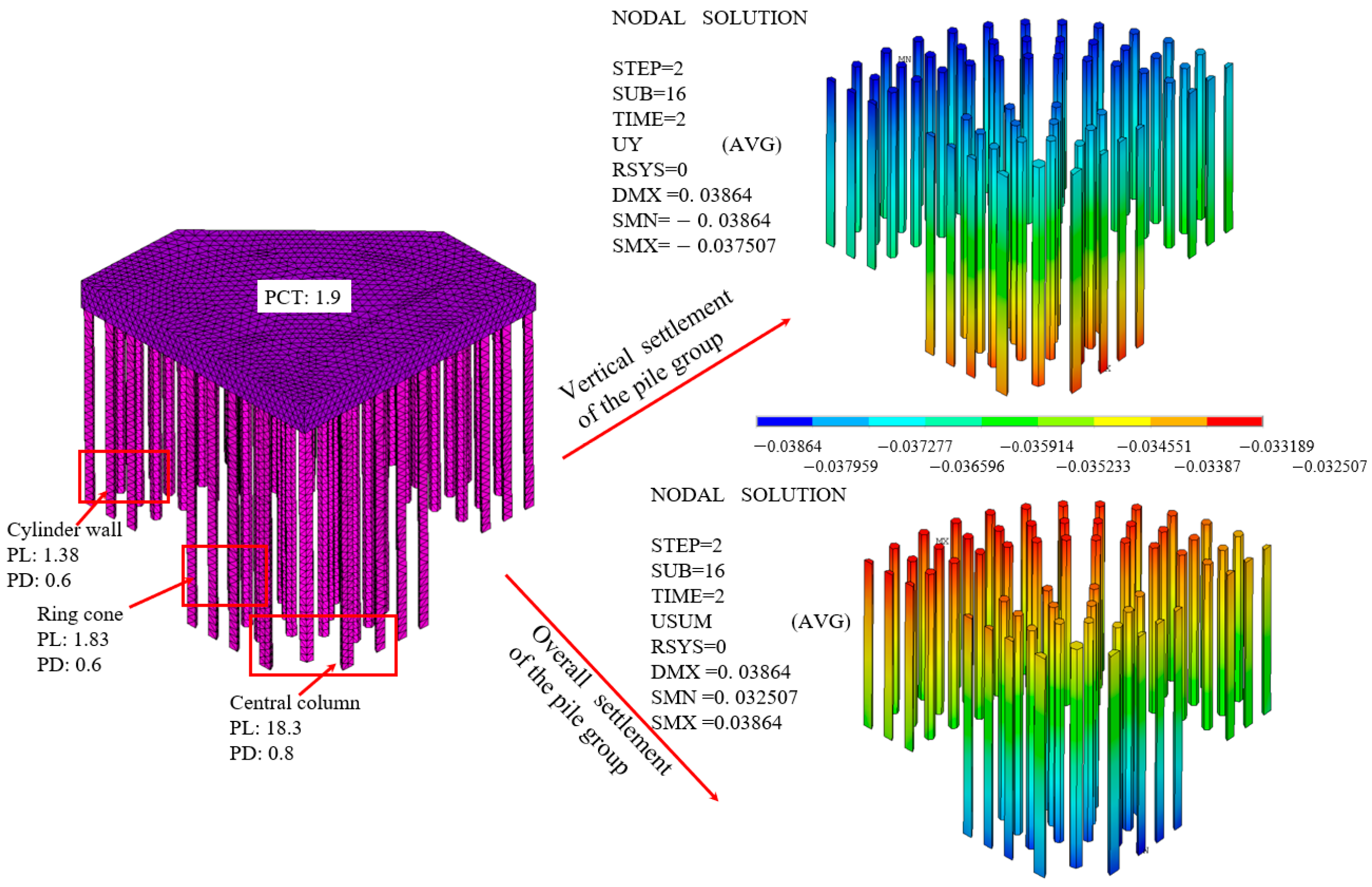

2.2. Numerical Model

2.2.1. Element Type and Material Constitutive Model

2.2.2. Mesh Size and Boundary Conditions

2.2.3. Contact and Loading

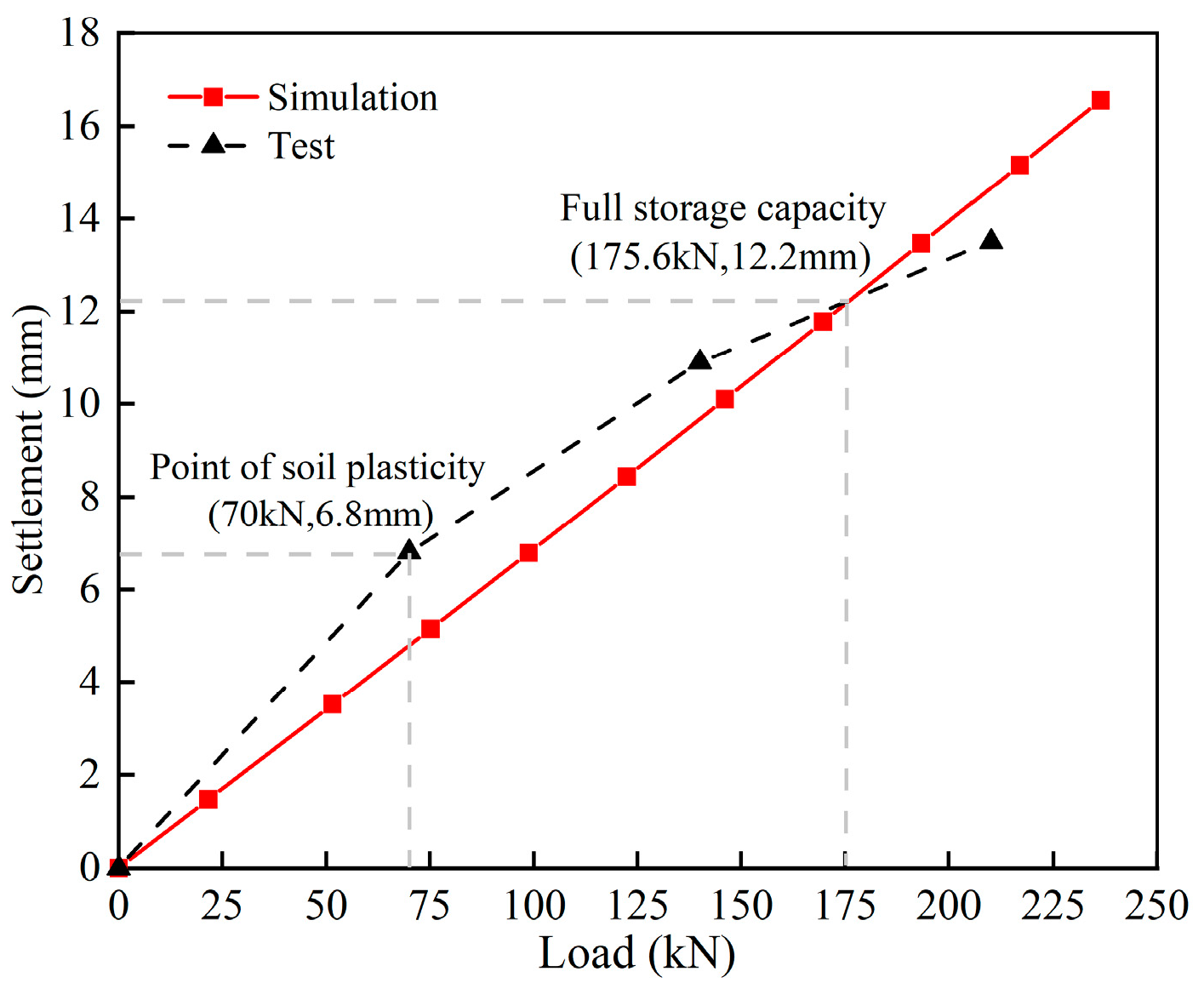

2.2.4. Finite Element Verification

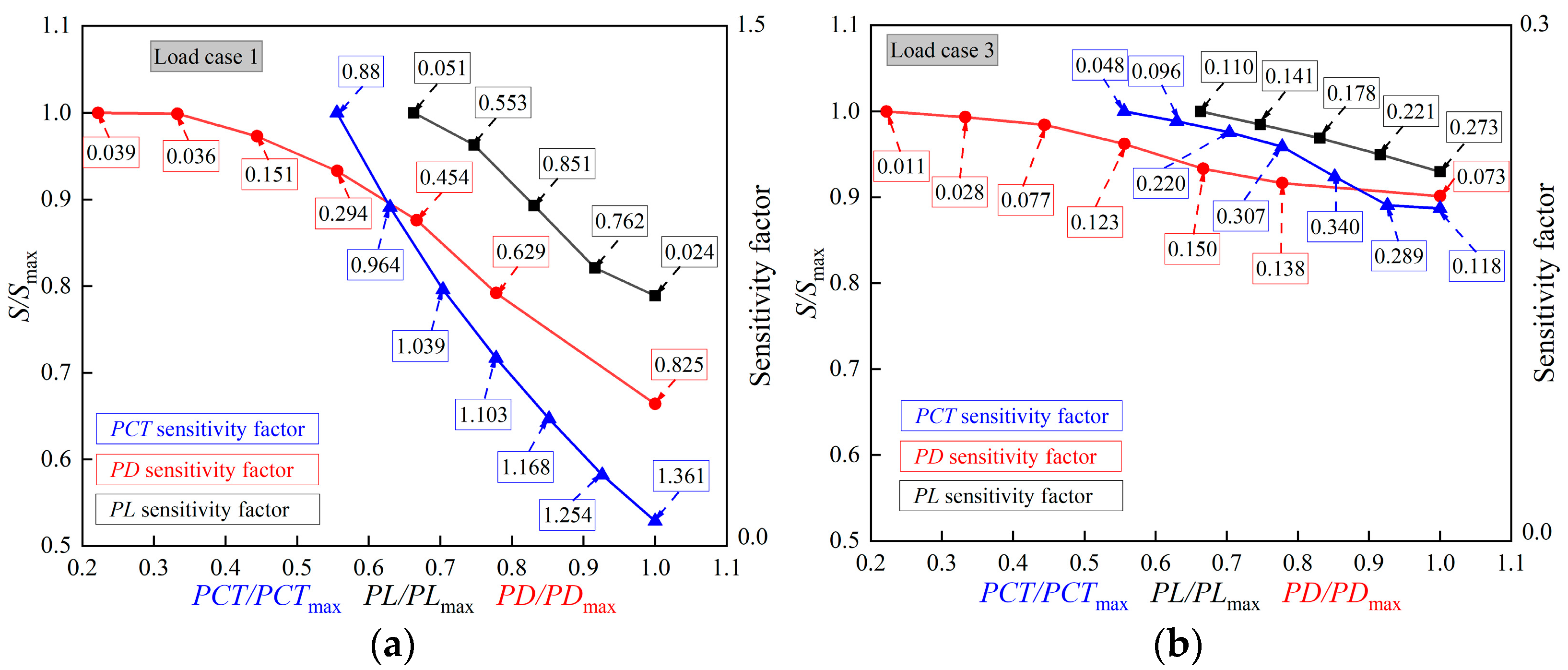

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Pile Foundation

2.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis Model

2.3.2. Parameter Design and Analysis

3. Optimization of Silo Pile Foundation

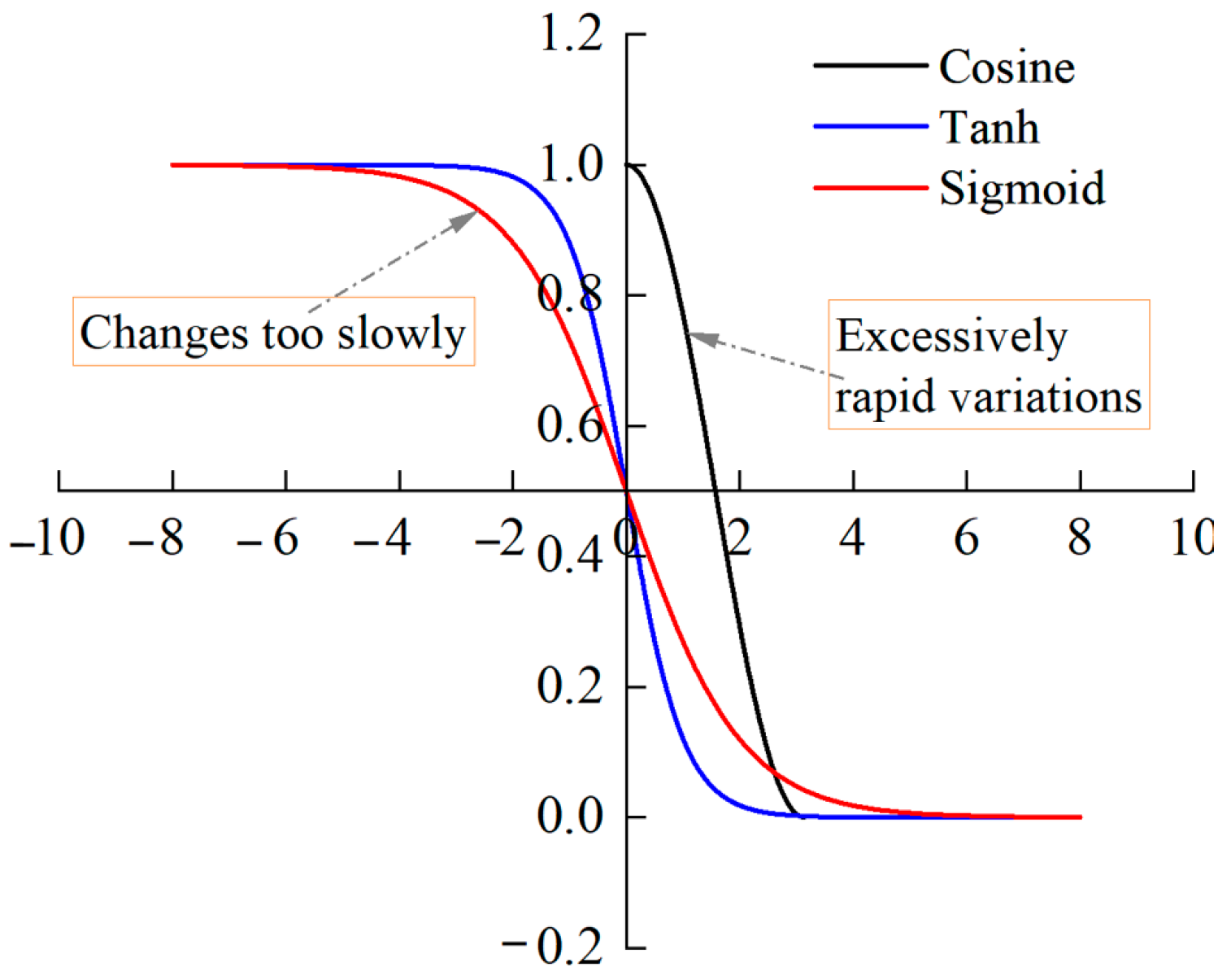

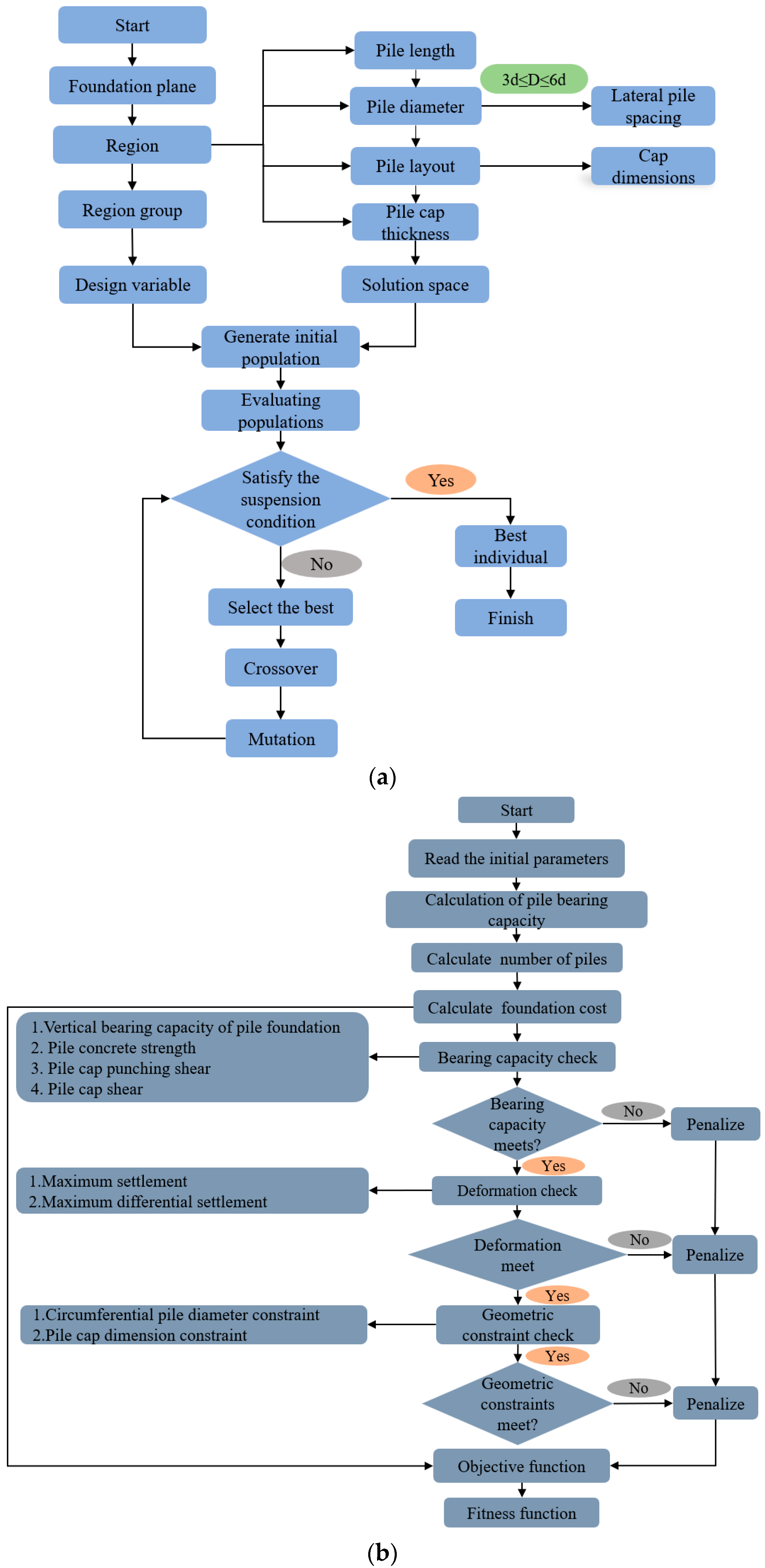

3.1. Improvement of Genetic Algorithm

3.2. Calculation Diagram

3.3. Optimization Model

3.3.1. Modularization of Pile Foundation

3.3.2. Optimization Model of Pile Foundation

3.3.3. Optimization Process of Pile Foundation

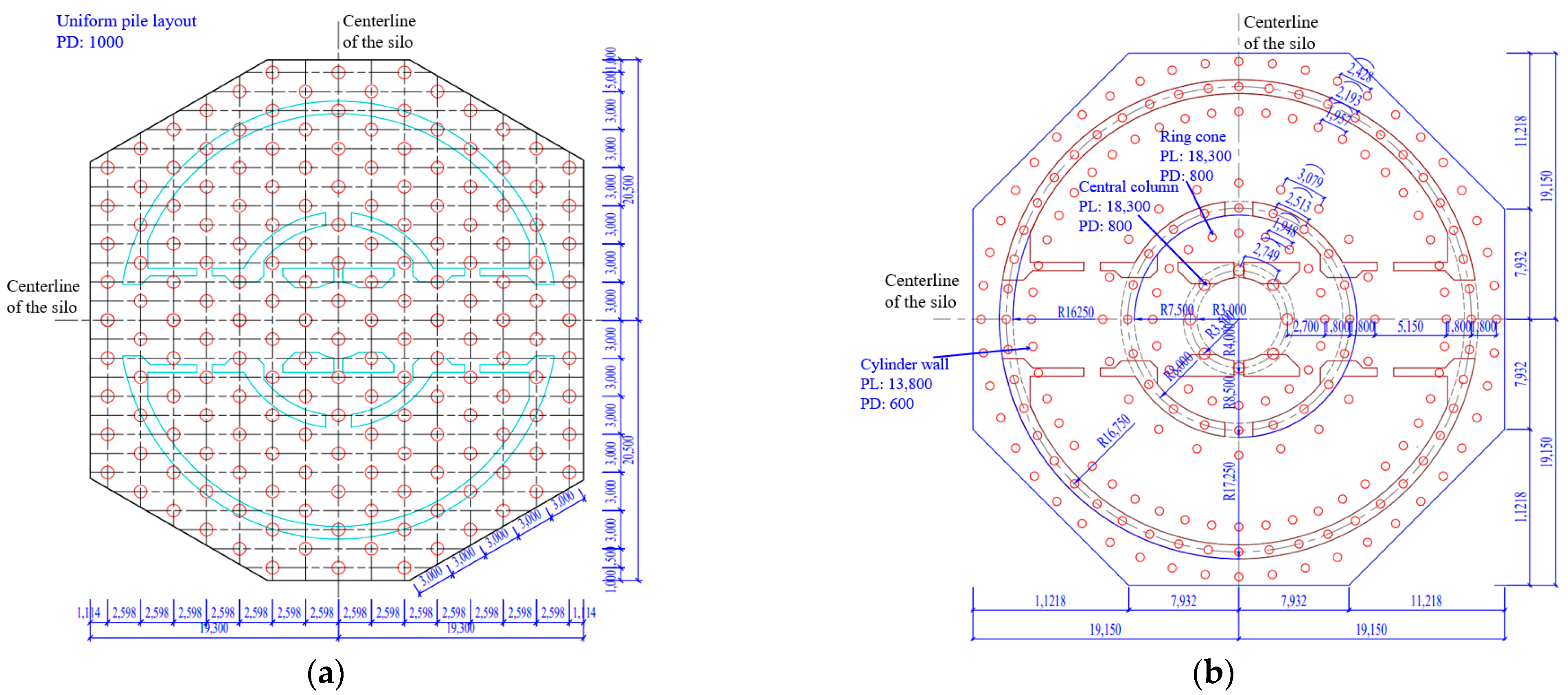

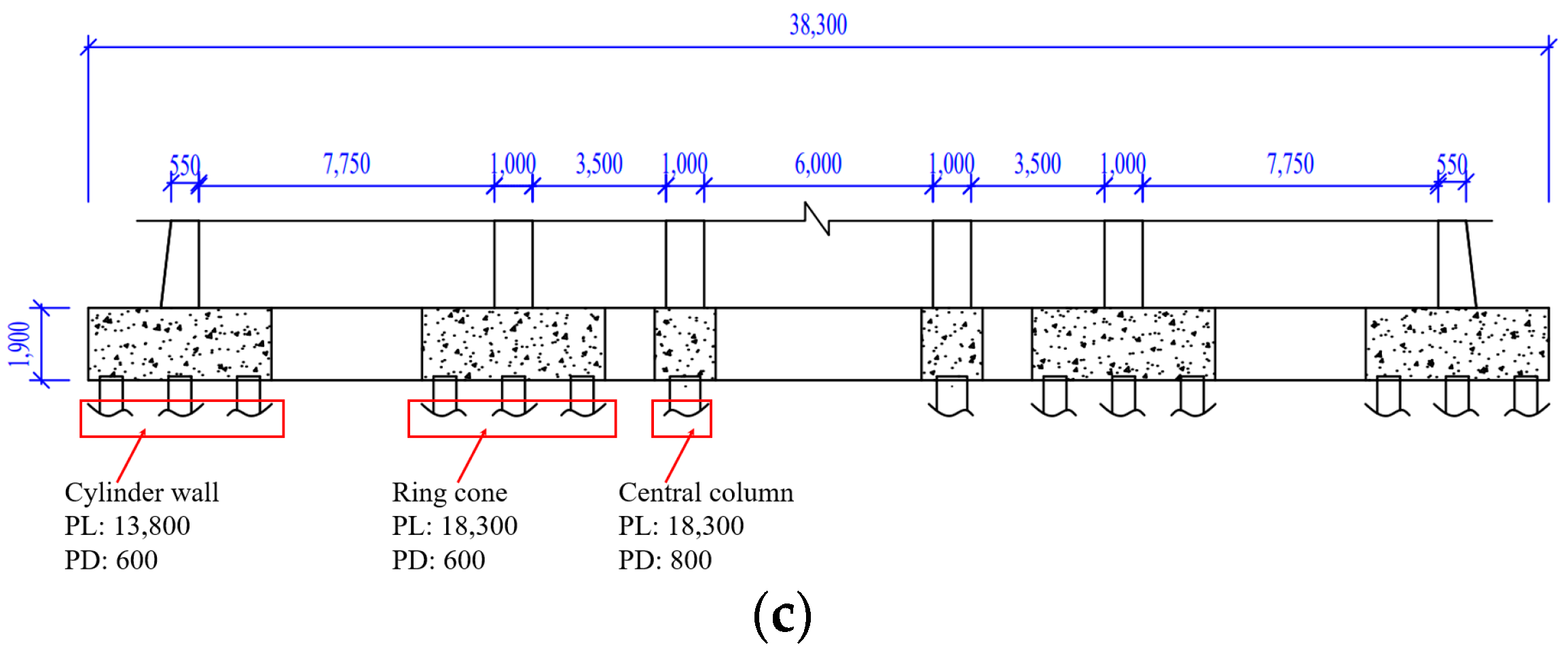

3.4. Optimization Results and Analysis

4. Conclusions and Discussion

- (1)

- During the production and operation of silos, the finite element (FE) simulation results demonstrate strong agreement with the actual measurement data, confirming the validity and reliability of the established numerical model. This model serves as a robust tool for further investigation into the effects of pile length (PL), pile diameter (PD), and pile cap thickness (PCT) on the maximum displacement of the structure (MDS) within the pile cap. It provides a solid theoretical foundation for optimizing the design of silo foundations.

- (2)

- To enhance the convergence and mutation effects of the automatic grouping genetic algorithm (AGGA), a power function was introduced to modify the adaptive penalty function, specifically the Lemonge function. Additionally, a novel genetic operator was constructed using the hyperbolic tangent function, whose rate of change lies between that of the cosine and Sigmoid functions. These improvements significantly enhance the algorithm’s global optimization capability and robustness, leading to superior performance in solving complex optimization problems.

- (3)

- Based on the results of the sensitivity analysis, the MDS within the pile cap exhibits a progressively decreasing sensitivity to variations in PL, PD, and PCT. This study further establishes the optimal ranges for key pile foundation parameters: PCT between 1.7 and 2.3 m, PL ranging from 11.8 to 19.3 m, and PD from 0.6 to 1.2 m. These findings provide valuable guidance for design optimization, contributing to improved structural safety and cost efficiency in practical engineering applications.

- (4)

- By introducing the improved AGGA and replacing short, thick piles with long, slender ones, the total volume of foundation concrete was reduced by 39.16% compared to the original design, effectively lowering construction costs. Additionally, the adoption of a variable stiffness piling strategy—stronger internally and weaker externally—reduced the MDS by 4.665 mm. This approach significantly improves the foundation’s deformation resistance and load-bearing performance, ensuring better structural stability under operational conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodey, R.J.; Brown, C.J. The influence of the base boundary condition in modelling filling of a metal silo. Comput. Struct. 2004, 82, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehretehran, A.M.; Maleki, S. 3D buckling assessment of cylindrical steel silos of uniform thickness under seismic action. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018, 131, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.D.; Livaoglu, R. SSI effects on seismic response of RC flat-bottom circular silos. Structures 2023, 57, 105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehretehran, A.M.; Maleki, S. Axial buckling of imperfect cylindrical steel silos with isotropic walls under stored solids loads: FE analyses versus Eurocode provisions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 137, 106282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Li, P. Shaking table tests on a small-scale steel cylindrical silo model in different filling conditions. Structures 2022, 37, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Mei, G.; Zhou, T.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Gong, W.; Sun, H.; Wang, T. Innovation and development of foundation technology. China Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 53, 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, Q.; Min, R.; Duan, Q. Sensitivity analysis of influencing factors of pile foundation stability based on field experiment. Structures 2023, 54, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, L.T.; Xiong, X.; Matsumoto, T. Effect of pile arrangement on long-term settlement and load distribution in piled raft foundation models supported by jacked-in piles in saturated clay. Soils Found. 2024, 64, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 94-2008; Technical Code for Building Pile Foundations. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Poulos, H.G. Piled raft foundations: Design and applications. Geotechnique 2001, 51, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Chen, M. Some issues on the optimum design for a piled raft foundation. China Civ. Eng. J. 2001, 4, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.; Park, J.; Chang, D. An approximate numerical analysis of rafts and piled-rafts foundation. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 168, 106108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansseune, A.; Corte, W.D.; Belis, J. Elasto-plastic failure of locally supported silos with U-shaped longitudinal stiffeners. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 70, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, W. Design philosophy and settlement analysis of the composite long-short pile foundations. China Civ. Eng. J. 2005, 12, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zeng, X.; Yang, X.; Li, J. Seismic response of offshore wind turbine with hybrid monopile foundation based on centrifuge modelling. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 1335–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Lian, J. Review of integrated installation technologies for offshore wind turbines: Current progress and future development trends. Energy Conv. Manag. 2022, 255, 115319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, M.F.; Wroth, C.P. An analysis of the vertical deformation of pile groups. Geotechnique 1979, 29, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.Y.; Chow, Y.K.; Yong, K.Y. A variational approach for vertical deformation analysis of pile group. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1997, 21, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.N.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, K.S.; Chung, C.K.; Kim, M.M.; Lee, H.S. Optimal pile arrangement for minimizing differential settlements in piled raft foundations. Comput. Geotech. 2001, 28, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.F.; Klar, A.; Soga, K. Theoretical study on pile length optimization of pile groups and piled rafts. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2010, 136, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Zai, J.; Huang, G. Optimization design method of composite pile foundation for controlling differential settlement. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2006, 2, 818–821+827. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Y.F.; Klar, A.; Soga, K.; Hoult, N.A. Superstructure-foundation interaction in multi-objective pile group optimization considering settlement response. Can. Geotech. J. 2017, 54, 1408–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalesari, A.T.; Choobbasti, A.J. Numerical analysis of settlement and bearing behaviour of piled raft in Babol clay. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 978–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, M.; Bhowmik, R. 3D numerical analysis of piled raft foundation in stone column improved soft soil. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 13, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Dai, Z. Calculation of interaction coefficient method for group pile settlement by single pile load test. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 38, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Chi, L.; Gao, W.; Liu, J. Experimental study on deformation behavior of piled raft foundation. J. Build. Struct. 2010, 31, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Q.; Li, H.; Gao, W. Deformation behavior and settlement calculation of pile group under vertical load. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 1995, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, R.; Liu, J.; Gao, W.; Qiu, M. Large scale model test study on settlement characteristics of long pile group foundation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 48, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zeng, C.; Liu, W. Optimal design method for pile foundation based on chaotic particle swarm algorithm. Build. Struct. 2016, 46, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, L. On distribution-based global sensitivity analysis by polynomial chaos expansion. Comput. Struct. 2022, 267, 106808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. The design and calculation method of pile-column bridge pier foundation in high and steep slope. Eng. Mech. 2013, 30, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Yang, M.; Yang, H.; Li, F. Study on bearing behaviors and model tests of composite pile foundation with long and short piles. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2007, 29, 580–586. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Chen, Z. Discussion on some key issues related to foundation engineering. Build. Struct. 2021, 51, 1–4+49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, T.; Li, A. Bearing behavior and optimization design of large-diameter long pile foundation in loess subsoil. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2017, 36, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Li, Y. Bearing capacity and displacement characteristics of long-short composite piles in loess areas. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2018, 40, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. Bearing capacity behaviors of subsoil underoptimal design mode of pile foundation stiffness to reduce differential settlement. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2011, 33, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. Bearing capacity of piles in optimized design of pile foundation stiffness to reduce differential settlement. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 37, 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- El-Garhy, B.; Galil, A.A.; Youssef, A.F.; Raia, M.A. Behavior of raft on settlement reducing piles: Experimental model study. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2013, 5, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, M.; Tang, Z.; Yuan, Z. Finite element analysis of huge coal silo foundation. Rock Soil Mech. 2010, 31, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, D. Variable stiffness leveling of piled raft foundation based on topology optimization method. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, D.; Saha, S.; Haldar, S. Behaviour of piled raft foundation in sand subjected to combined VMH loading. Ocean Eng. 2020, 216, 107596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chi, S.; Zhou, X. Research on optimization design method of large-scale pile-raft foundation in complex environment. Rock Soil Mech. 2019, 40, 486–493. [Google Scholar]

- Momeni, E.; Nazir, R.; Armaghani, D.J.; Maizir, H. Prediction of pile bearing capacity using a hybrid genetic algorithm-based ANN. Measurement 2014, 57, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Park, S. Optimum retrofit strategy of FRP column jacketing system for non-ductile RC building frames using artificial neural network and genetic algorithm hybrid approach. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhu, H. Coevolutionary Genetic Algorithm of Cloud Workflow Scheduling Based on Adaptive Penalty Function. Comput. Sci. 2018, 45, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, H.J.C.; Lemonge, A.C.C.; Borges, C.C.H. A genetic algorithm encoding for cardinality constraints and automatic variable linking in structural optimization. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 3708–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineering Geology Handbook Editorial Committee. Engineering Geology Handbook; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.K.; Yang, Y.B.; Zhao, S.B.; Fu, Z.Q. Experimental and numerical investigation of the effect of temperature patterns on behavior of large scale silo. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 91, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Rui, Y.; Dong, B. Determination of dilatancy angle for geomaterials under non-associated flow rule. Rock Soil Mech. 2009, 30, 3278–3282. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, D. FLAC/Flac3D Fundamentals and Engineering Applications; China Water and Power Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pucker, T.; Bienen, B.; Henke, S. CPT based prediction of foundation penetration in siliceous sand. Appl. Ocean Res. 2013, 41, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, A.R.; Arta, M.R. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of pile groups under lateral loading. Comput. Struct. 1991, 40, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50077-2017; Standard for Design of Reinforced Concrete Silos. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Ooi, J.Y.; Rotter, J.M. Wall pressures in squat steel silos from simple finite element analysis. Comput. Struct. 1990, 37, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, W.; Kong, J.; Xiao, J.; Yuan, J. Study of computation of load on pile top of piled raft foundation for superhigh buildings. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 1138–1142. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50191-2012; Code for Seismic Design of Special Structures. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB 50009-2012; Load Code for the Design of Building Structures. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Zhang, G.; Zhu, W. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Optimizing for Test Programs. Rock Soil Mech. 1993, 14, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Lu, S.; Wang, K.; Tang, J.; Yao, Z. Sensitivity Analysis of Springback to Material Parameters in High Strength 21-6-9 Stainless Steel Tube NC Bending. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2015, 49, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Q.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Q.; Qi, J.; Li, A.; Huang, J. Determination of advance supports in tunnel construction under unfavourable rock conditions. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2016, 35, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lemonge, A.C.C.; Barbosa, H.J.C. An adaptive penalty scheme for genetic algorithms in structural optimization. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2004, 59, 703–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, H.J.C.; Lemonge, A.C.C. A new adaptive penalty scheme for genetic algorithms. Inf. Sci. 2003, 156, 215–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50007-2011; Code for Design of Building Foundation. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

| Soil Layer | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Loess silty soil | Loess silty clay | Crushed stone | Loess silty clay | Strongly weathered andesite | Mid-weathered andesite |

| Thickness (m) | 0.70 | 1.70 | 4.00 | 5.40 | 7.50 | Not debunked |

| Unit weight (kN·m−3) | 19.60 | 18.90 | 19.60 | 19.50 | 22.50 | 26.50 |

| Standard value of ultimate shaft resistance (kPa) | 60.00 | 75.00 | 150.00 | 80.00 | 200.00 | 240.00 |

| Standard ultimate bearing capacity (kPa) | / | / | / | / | 2000 | 2200.00 |

| Poisson ratio | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.20 |

| Modulus of compression (MPa) | 7.65 | 5.73 | 40.32 | 7.87 | 62.00 | 29,444.00 |

| Standard value of internal friction angle (°) | 12.80 | 11.70 | 10.90 | 21.00 | 13.50 | 55.00 |

| Materials | Standard Value (MPa) | Design Value (MPa) | Poisson Ratio | Unit Weight (kN·m−3) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C40 Concrete | 26.8 | 19.1 | 0.2 | 24.0 | 32,500 |

| C30 Concrete | 20.1 | 14.3 | 0.2 | 24.0 | 30,000 |

| HRBE400 Rebar | 400.0 | 360.0 | 0.3 | 78.5 | 200,000 |

| Soil Layer | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Loess silty soil | Loess silty clay | Crushed stone | Loess silty clay | Strongly weathered andesite | Mid-weathered andesite |

| Young’s modulus (MPa) | 22.95 | 17.19 | 121.00 | 23.61 | 186.00 | 88,333.0 |

| Poisson ratio | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.2 |

| Standard value of internal friction angle (°) | 12.80 | 11.70 | 10.90 | 21.00 | 13.50 | 55.0 |

| Cohesion standard value (kPa) | 13.30 | 17.80 | 16.10 | 25.00 | 100.00 | 1500.0 |

| Dilation angle (°) | 6.40 | 5.85 | 5.45 | 10.50 | 6.75 | 27.5 |

| Contact Pairs | Contact Surface | Target Surface | Coefficient of Friction [51] | Cohesion (kPa) | Ultimate Shaft Resistance (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Silo ① | pile | 0.117 | 10.64 | 60.00 |

| 2 | Silo ② | 0.109 | 14.24 | 75.00 | |

| 3 | Silo ③ | 0.179 | 12.88 | 150.00 | |

| 4 | Silo ④ | 0.160 | 20.00 | 80.00 | |

| 5 | Silo ⑤ | 0.182 | 80.00 | 200.00 | |

| 6 | Silo ⑥ | 0.135 | 1200.00 | 240.00 | |

| 7 | ① surface | Pile cap bottom surface | 0.117 | 10.64 | 60.00 |

| Components | Relative Height (m) | Horizontal Pressure Ph (kPa) | Vertical Pressure Pv (kPa) | Normal Pressure Pn (kPa) | Tangential Pressure Pt (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silo wall | 38.239 | 0.000 | / | / | / |

| 12.070 | 91.419 | / | / | / | |

| Central column | 38.239 | 0.000 | / | / | / |

| 6.518 | 110.252 | / | / | / | |

| Hopper | 12.070 | / | 293.766 | 142.006 | 87.619 |

| 5.090 | / | 369.757 | 178.784 | 110.311 | |

| Ring cone (inside) | 10.611 | / | 309.669 | 149.693 | 92.362 |

| 4.532 | / | 375.930 | 181.724 | 112.125 | |

| Ring cone (outside) | 10.611 | / | 309.669 | 131.656 | 79.257 |

| 3.58 | / | 386.307 | 164.238 | 98.871 |

| Load Combination | Factor | Structural Weight | Storage Material Pressure | Horizontal Seismic Load |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard (Load case 1) | Partial | 1.0 | 1.0 | — |

| Combination | 1.0 | 0.9 | — | |

| Basic (Load case 2) | Partial | 1.2 | 1.3 | — |

| Combination | 1.0 | 0.9 | — | |

| Seismic (Load case 3) | Partial | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Combination | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Calculation Cases | Parameter Values (m) |

|---|---|

| Case 1 (c) | 1.5, 1.7, 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, 2.5, 2.7 |

| Case 2 (l) | 10.3, 11.8, 13.3, 14.8, 16.3, 17.8, 19.3 |

| Case 3 (d) | 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.8 |

| Test Functions | Dimension | Number of Iterations | Average Optimal Fitness of SGA | Average Optimal Fitness of AGGA | Average Optimal Fitness of IAGGA | Optimal Fitness Squared Difference in SGA | Optimal Fitness Squared Difference in AGGA | Optimal Fitness Squared Difference in IAGGA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphere | 20 | 1000 | 4.81 × 10−7 | 7.74 × 10−9 | 7.21 × 10−10 | 2.60 × 10−8 | 1.94 × 10−9 | 2.73 × 10−10 |

| 40 | 2000 | 6.48 × 10−6 | 5.03 × 10−8 | 2.58 × 10−8 | 4.33 × 10−7 | 6.32 × 10−9 | 9.27 × 10−9 | |

| 60 | 3000 | 7.97 × 10−5 | 4.82 × 10−6 | 3.75 × 10−7 | 5.23 × 10−6 | 6.98 × 10−7 | 8.48 × 10−8 | |

| Ackley | 20 | 1000 | 6.83 × 10−4 | 3.29 × 10−6 | 1.90 × 10−6 | 4.67 × 10−5 | 1.69 × 10−6 | 4.33 × 10−7 |

| 40 | 2000 | 8.05 × 10−4 | 8.34 × 10−5 | 1.58 × 10−5 | 7.39 × 10−5 | 6.82 × 10−6 | 6.72 × 10−7 | |

| 60 | 3000 | 5.89 × 10−3 | 7.84 × 10−4 | 5.45 × 10−4 | 6.38 × 10−4 | 8.76 × 10−5 | 1.90 × 10−6 | |

| Rastrgin | 20 | 1000 | 3.26 × 10−3 | 8.12 × 10−5 | 2.86 × 10−8 | 7.31 × 10−4 | 3.89 × 10−6 | 8.78 × 10−7 |

| 40 | 2000 | 2.43 × 1000 | 5.24 × 10−3 | 4.53 × 10−6 | 8.78 × 10−2 | 6.03 × 10−4 | 4.23 × 10−7 | |

| 60 | 3000 | 4.67 × 1000 | 6.28 × 10−1 | 7.46 × 10−3 | 7.39 × 10−1 | 9.78 × 10−2 | 6.92 × 10−4 |

| Module | Calculated Number of Piles | Adopted Number of Piles | Radial Pile Spacing (m) | Outer Circumferential Pile Spacing (m) | Middle Circumferential Pile Spacing (m) | Inner Circumferential Pile Spacing (m) | Pile Cap Outer Radius (m) | Pile Cap Inner Radius (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cylinder wall | 134 | 144 | 1.800 | 2.428 | 2.193 | 1.957 | 19.150 | 14.350 |

| Ring cone | 58 | 60 | 1.800 | 3.079 | 2.513 | 1.948 | 10.400 | 5.600 |

| Central column | 7 | 8 | — | — | 2.749 | — | 4.300 | 2.700 |

| Module | Pile Group Concrete Volume (m3) | Pile Cap Concrete Volume (m3) | Total Concrete Volume (m3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Optimized | Original | Optimized | Original | Optimized | |

| Cylinder wall | — | 523 | 3395 | 2309 | 5253 | 3196 |

| Ring cone | — | 300 | ||||

| Central column | — | 64 | ||||

| Total volume | 1858 | 887 | 3395 | 2309 | 5253 | 3196 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhao, P.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Z. Research on the Optimization Design of Large-Diameter Silo Foundation Piles Based on an Automatic Grouping Genetic Algorithm. Buildings 2026, 16, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010160

Yang Y, Deng L, Zhao P, Liu X, Li X, Chen Z. Research on the Optimization Design of Large-Diameter Silo Foundation Piles Based on an Automatic Grouping Genetic Algorithm. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010160

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yabin, Lianchao Deng, Pengtuan Zhao, Xubang Liu, Xiaoke Li, and Zhen Chen. 2026. "Research on the Optimization Design of Large-Diameter Silo Foundation Piles Based on an Automatic Grouping Genetic Algorithm" Buildings 16, no. 1: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010160

APA StyleYang, Y., Deng, L., Zhao, P., Liu, X., Li, X., & Chen, Z. (2026). Research on the Optimization Design of Large-Diameter Silo Foundation Piles Based on an Automatic Grouping Genetic Algorithm. Buildings, 16(1), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010160