“True” Accessibility Barriers of Heritage Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control”.

2. Accessibility of Heritage Buildings—Global Initiatives

3. Canada’s Heritage Buildings and Accessibility Standards

- Space and dimensional constraints: area allowances and dimensional constraints of entrances, halls, corridors, accessible routes, doors and doorways, ramps, and washroom facilities that do not provide enough manoeuvrability space for individuals with wheeled mobility devices.

- Doors and doorways requirements: replacing heritage-designated doors with accessible ones might impact the existing elements like walls, partitions, doors, etc.

- Vertical circulation requirements: buildings that cannot accommodate the installation of accessible vertical circulation means like ramps, elevators, and platform lifts may impede the navigation of individuals with physical and sensory impairments.

- Stairs and stairways requirements: altering stairs’ features can be challenging in existing conditions without harming the heritage fabric.

- Elevating devices: elevating devices can facilitate vertical circulations; however, their installation could be unfeasible and/or potentially damaging to the heritage spaces.

- Headroom and protruding object requirements: removing or adjusting headroom or protruding object space could potentially cause damage to the heritage fabric.

- Lack of luminance (colour) contrast: walls, floors, doors, and ceilings that lack luminance (colour) contrast with their surroundings impede the wayfinding for those relying on visual cues.

- Illumination considerations: installing lighting fixtures in dim spaces could damage the heritage fabric. Art pieces and sensitive materials might be affected by excessive lighting.

- Tactile indicators and signage requirements: installation of tactile indicators and signage as per the standard’s requirements might cause destruction to the fabric such as floors, stairs, walls, etc.

- Air ventilation/control and acoustics: the building’s interior might be affected by enhancing the air ventilation and acoustics to accommodate those with functional or cognitive disabilities.

4. Experimental Investigations

- Step 1—identify the historical significance of the building and list the character-defining elements, if designated by the Canadian Register of Historic Places (CRHP).

- Step 2—determine whether the building has undergone any accessibility renovations.

- Step 3—refer to the CSA B651 accessibility standard to become acquainted with relevant accessibility requirements.

- Step 4—prepare a schematic of the building for documentation.

- Step 5—conduct a site visit and identify any accessibility barriers.

- Step 6—assess the causes of the accessibility barriers.

- Step 7—prepare a summary report.

4.1. Barriers Due to Conflict Between Accessibility and Heritage Preservation

- Some spaces do not provide enough manoeuvring areas for mobility devices, hindered by original pipes and machinery. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 4.1 specifies a minimum manoeuvring area for mobility devices.

- Some hallways are narrow and pose a barrier to manoeuvre with mobility devices. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 4.1 provides the clear floor area required to accommodate users with wheeled mobility devices.

- The washrooms do not have enough space to accommodate individuals with powered-mobility devices. The original washroom layout impedes adjusting its dimensions. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 6.2.2 provides the manoeuvring clear floor area in washroom facilities.

- The original doors are very narrow. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.2.1 mandates a clear opening width of 860 mm.

- The original door handles are round-style knobs and require fine motor skills and twisting of the wrist to operate. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.2.7.1 recommends using lever handles or push plate/door pull (U-shaped handles).

- The original high thresholds at doorways pose a physical barrier to navigating with mobility devices. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.2.6 mandates thresholds not to be more than 13 mm.

- The original stairs are steep and poorly designed with inadequate handrails and closely spaced treads. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.4 provides detailed requirements for accessible stairs.

- The absence of elevators or elevators that do not serve all floors poses a challenge to navigate the site. Installing elevators in heritage buildings can be challenging without affecting the heritage fabric.

- The building is only accessible via stairs with no ramps provided at all entrances. This poses a challenge for individuals with mobility impairments, particularly when elevators are not provided as an alternative.

- The original seats are very narrow. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 6.7.1.1 specifics the clear floor area for seating space.

- The poor acoustics generate echo in a large volume of space. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 4.7.3 recommends designing a sound-controlled environment.

4.2. Barriers Due to Heritage Preservation and/or Standard Compliance

- The stairs are poorly maintained and lack tactile attention indicators and handrails. This barrier does not meet the CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.4 stairs requirements.

- The stairs lack colour contrast and tactile surface indicators. This barrier does not meet the CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.4 stairs requirements.

- The public washroom facilities are inaccessible due to the limited space to accommodate mobility devices. This barrier does not meet CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 6.2 washroom facilities requirements.

- The signs are poorly designed, dark, and hard to locate. This barrier does not meet CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 4.6 signage requirements and clause 4.6.5 which requires the level of illumination on signs to be at least 200 lx.

4.3. Barriers Due to Accessibility Standard Compliance or Specificity

- The accessible ramp to access the building is very long. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.5.1 requires a horizontal distance between the ramp’s level landings no greater than 9000 mm.

- The main entrance or washroom doors are not power-assisted and hard to open manually. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.2.8 recommends the use of a power-assisted door if a force greater than 22 N is required to open a door.

- The stairs lack colour contrast and have a slippery surface. CSA/ASC B651:23 clauses 5.4.1 and 5.4.2 provide the requirements for stairs treads, risers, and nosing.

- The carpets on the stairs have a busy pattern that disorients an individual with a visual impairment. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.4.1 recommends avoiding busy patterns on stairs.

- There were no colour-contrasted strips on the glazing doors. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 5.2.10 mandates marking glazed panels with a continuous opaque strip.

- There were no accessible washroom facilities on every floor. CSA/ASC B651:23 is not specific about the number of washrooms in the building.

- There were no seating options with armrests. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 6.7.2.2 requires providing a mix of seats, where there is more than one, i.e., some with backrests, some with armrests, and some with both.

- The lighting was poor in the main spaces of the building, making it hard to read signs or distinguish between major features. CSA/ASC B651:23 is not specific on the level of illumination in the general areas of a building. However, clause 4.6.5 requires the signage illumination to be at least 200 lx.

- Signs throughout the site are poorly designed or non-existent, posing difficulties in navigation/wayfinding. CSA/ASC B651:23 clause 4.6 provides signage requirements.

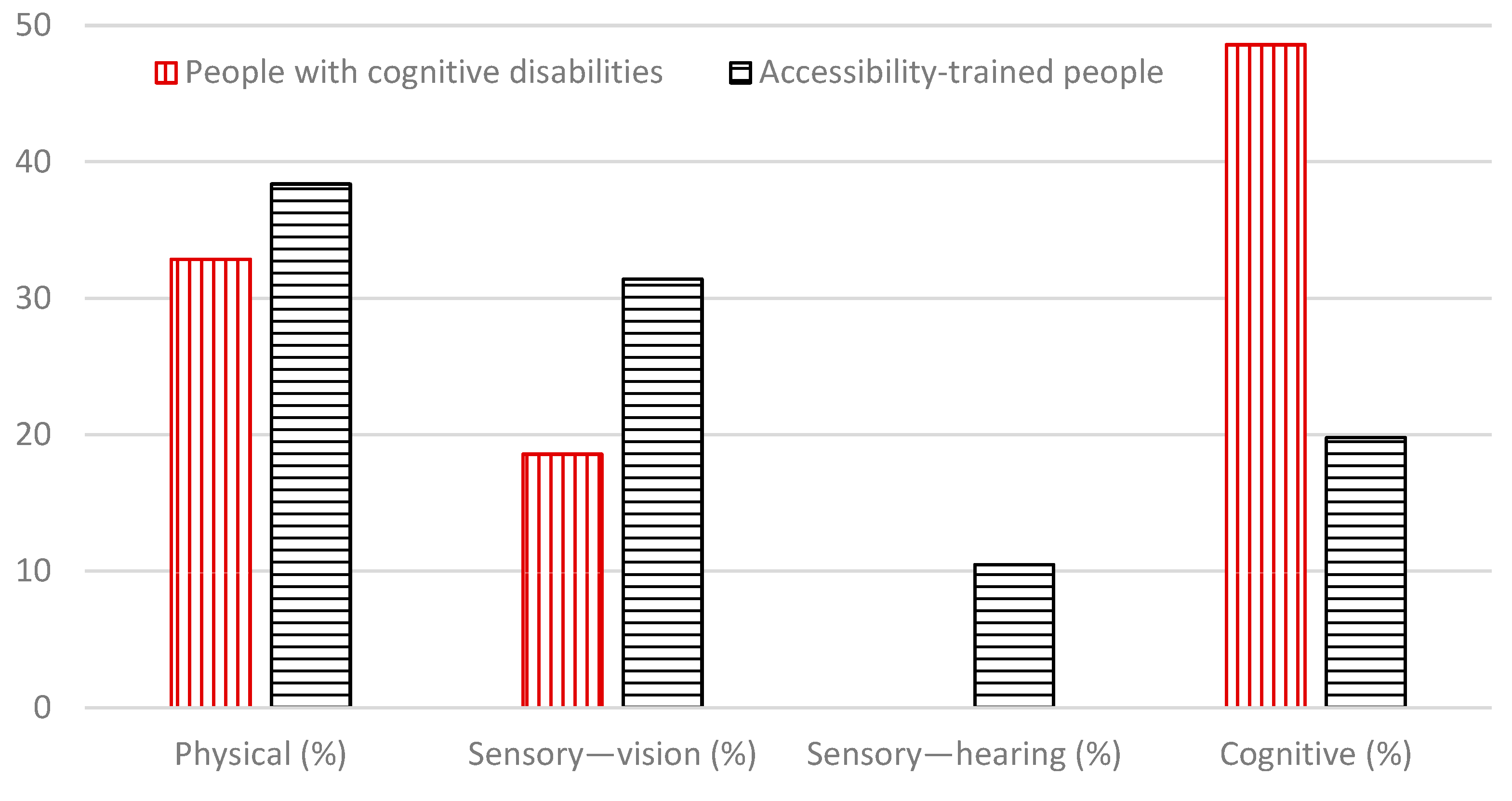

5. Analysis and Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Accessibility standards, which are continuously evolving, do not meet the needs of all people with disabilities, specifically people with sensory and cognitive/intellectual disabilities. It is found to lack clarity, specificity, and completeness.

- Accessibility barriers identified in Canada’s heritage buildings include entrances and doors, stairs, building layout, lighting, acoustics, seating, floor areas and dimensions, and washroom facilities. A significant number of them can be mitigated by applying current accessibility standard requirements.

- Conflicts between accessibility and heritage preservation constitute about 19% of the “true” barriers in comparison to issues associated with code compliance and code clarity.

- A total of 19%, 17%, and 64% of reported “true” barriers per heritage building were attributed to conflict between accessibility and heritage preservation, accessibility standard clarity/specificity, and accessibility standard compliance, respectively.

- A total of 16%, 39%, and 45% of reported “perceived” barriers per heritage building by accessibility-trained people were attributed to the conflict between accessibility and heritage preservation, accessibility standard clarity/specificity, and accessibility standard compliance, respectively.

- The needs of people with cognitive/intellectual disabilities are the least addressed and understood by accessibility codes and standards and accessibility-trained professionals.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Pianosi, R.; Presley, L.; Buchanan, J.; Lévesque, A.; Savard, S.-A.; Lam, J. Canadian Survey on Disability, 2022: Concepts and Methods Guide; Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023.

- United Nations. 70 Years of the Work Towards a More Inclusive World; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- United Nations A/RES/61/106: Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities—Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 13 December 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_61_106.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Jester, T.C.; Park, S.C. Making Historic Properties Accessible; Preservation Briefs (Volume 32); National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Nicolás, J.; Sáez-Pérez, M.P. An Evaluation Tool for Physical Accessibility of Cultural Heritage Buildings. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Pérez, M.P.; Marín-Nicolás, J. Design of a Support Tool to Improve Accessibility in Heritage Buildings—Application in Case Study for Public Use. Buildings 2023, 13, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani Mehr, S.; Wilkinson, S. A Model for Assessing Adaptability in Heritage Buildings. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 12, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S.; Proverbs, D.G. How Adaption of Historic Listed Buildings Affords Access. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2020, 38, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.S.P.; dos Reis, A.A.; Cinelli, M.J. Accessibility of Buildings of Historical and Cultural Interest; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Americans with Disabilities Act Appendix A to Part 1191-Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities. Available online: https://www.access-board.gov/adaag-1991-2002.html#4.1.7 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Grimmer, A.E. The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for Preserving, Rehabilitating, Restoring & Reconstructing Historic Buildings. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1739/secretary-standards-treatment-historic-properties.htm (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- WBDG Whole Building Design Guide. Provide Accessibility for Historic Buildings. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/do/preservation/provide-accessibility#:~:text=Exterior%20accessibility%20can%20be%20accommodated,adequate%20turning%20radius%20at%20intervals (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Richard Williams Heritage Buildings and the Challenges Compliance with Current Regulations. Available online: https://www.consandheritage.co.uk/articles/heritage-buildings-and-the-challenges-compliance-with-current-regulations (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- The National Archives—HM Government Equality Act 2010 (c.15). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- HM Government. The Building Regulations 2010—Access to and Use of Buildings; HM Government: London, UK, 2015.

- Historic England Easy Access to Historic Buildings. Available online: www.historicengland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Historic England. Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance—For the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment; Historic England: London, UK, 2008.

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin. Cultural Heritage and Barrier-Free Accessibility—Guideline and Student Projects. Available online: https://backend.use.metropolis.org/system/images/1701/original/CulturalHeritage_and_Barrier-free_en.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Raum und Bau. Albrechtsburg Castle, Meissen. Available online: https://www.raumundbau.de/portfolio/schloss-albrechtsburg/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Office of Parliamentary Counsel. Disability Discrimination Act 1992, No. 135, 1992, Compilation No. 38; Office of Parliamentary Counsel: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Australia ICOMOS the Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance 2013. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Martin, E. Improving Access to Heritage Buildings: A Practical Guide to Meeting the Needs of People with Disabilities; Australian Council of National Trusts: Canberra, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Basilica of San Petronio. Visit to the Basilica of San Petronio. Available online: https://www.basilicadisanpetronio.org/en/visits/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Japanese Government. The Building Standard Law of Japan; Japanese Government: Tokyo, Japan, 2016.

- Brundtland Commission. United Nations Our Common Future—Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sakkaf, A.; Zayed, T.; Bagchi, A. A Sustainability Based Framework for Evaluating the Heritage Buildings. Int. J. Energy Optim. Eng. 2020, 9, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, C. Sustainability—A Guiding Principle of the World Heritage Convention—What Has Been Achieved—What Is Missing—What Is the Future Perspective. In 50 Years World Heritage Convention: Shared Responsibility—Conflict & Reconciliation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 445–457. [Google Scholar]

- Parks Canada About World Heritage. Available online: https://parks.canada.ca/culture/spm-whs/a-propos-about (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- United Nations General Assembly Adopts Groundbreaking Convention, Optional Protocol on Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2006/ga10554.doc.htm (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Canadian Heritage. Towards a New Act Protecting Canada’s Historic Places; Canadian Heritage: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2002.

- Parks Canada. Framework for History and Commemoration—National Historic Sites System Plan. In National Historic Sites System Plan; Parks Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2019; ISBN 9780660311197. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, D. Preserving Canada’s Heritage: The Foundation for Tomorrow; Report of the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; House of Commons Chamber des Communes Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017.

- Government of Canada Summary of the Accessible Canada Act. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/accessible-canada/act-summary.html (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- NRCC-CONST-56435E; National Building Code of Canada 2020. Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022; ISBN 9780660379135.

- CAN-ASC-2; Heritage Buildings and Sites. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; In Development.

- CSA/ASC B651:23; Accessible Design for the Built Environment. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023.

- Chidiac, S.E.; Reda, M.A.; Marjaba, G.E. A Framework for Accessible Heritage Buildings & Structures Retrofits; McMaster University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Year Built | Location | Primary Use | Participant’s Type of Disability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Her Majesty’s/St. Paul’s Chapel of the Mohawks National Historic Site of Canada | 1785 | Brantford, Ontario | Religious Facility or Place of Worship | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Province House | 1811–1819 | Halifax, Nova Scotia | Government Legislative Building | Vision |

| Chiefswood National Historic Site of Canada | 1853–1856 | Six Nations Grand River Reserve, Ontario | Museum | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Art Gallery of Nova Scotia | 1861–1868 | Halifax, Nova Scotia | Art Museum | Vision |

| The Cundall Home | 1877 | Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island | Museum/Historic Site | Physical |

| Victoria City Hall National Historic Site of Canada | 1878–1891 | British Columbia | Government City Hall | Physical |

| Le Labo retail store, Gastown Historic District National Historic Site of Canada/Granville Townsite | 1886–1914 | Vancouver, British Columbia | Historic Neighbourhood/Suburb | Hearing |

| Tacofino taco bar, Gastown Historic District National Historic Site of Canada/Granville Townsite | 1886–1914 | Vancouver, British Columbia | Historic Neighbourhood/Suburb | Hearing |

| Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site of Canada | 1894–1964 | British Columbia | Museum/ Historic Site | Physical |

| Calgary Old City Hall | 1907–1911 | Calgary, Alberta | Government City Hall | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Winnipeg Law Courts National Historic Site of Canada | 1912–1916 | Winnipeg, Manitoba | Government City Hall | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Manitoba Legislative Assembly | 1913–1920 | Winnipeg, Manitoba | Government Legislative Building | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Pacific Central Station—Canadian National Railways/VIA Rail Station | 1917 | Vancouver, British Columbia | Historic or Interpretive Site | Intellectual/Developmental |

| University Hall—McMaster University | 1930 | Hamilton, Ontario | University Building | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Hamilton Hall—McMaster University | 1930 | Hamilton, Ontario | University Building | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Calgary Public Building | 1930–1931 | Calgary, Alberta | Government Office Building | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Vancouver City Hall | 1935–1936 | Vancouver, British Columbia | Government City Hall | Intellectual/Developmental |

| Charlottetown Library Learning Centre, Dominion Building | 1955 | Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island | Public Library | Physical |

| Type of Disability | Barriers to Accessible Heritage Buildings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes | Number | Total Number | Total/Buildings | |

| Physical | Heritage preservation | 4 | 27 | 9 |

| Standard compliance | 21 | |||

| Standard clarity | 2 | |||

| Sensory—vision | Heritage preservation | 9 | 35 | 18 |

| Standard compliance | 21 | |||

| Standard clarity | 5 | |||

| Sensory—hearing | Heritage preservation | 5 | 28 | 14 |

| Standard compliance | 17 | |||

| Standard clarity | 6 | |||

| Cognitive/intellectual | Heritage preservation | 14 | 135 | 14 |

| Standard compliance | 64 | |||

| Standard clarity | 57 | |||

| Accessibility-trained people | Heritage preservation | 14 | 85 | 21 |

| Standard compliance | 38 | |||

| Standard clarity | 33 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chidiac, S.E.; Reda, M.A. “True” Accessibility Barriers of Heritage Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091528

Chidiac SE, Reda MA. “True” Accessibility Barriers of Heritage Buildings. Buildings. 2025; 15(9):1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091528

Chicago/Turabian StyleChidiac, Samir E., and Mouna A. Reda. 2025. "“True” Accessibility Barriers of Heritage Buildings" Buildings 15, no. 9: 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091528

APA StyleChidiac, S. E., & Reda, M. A. (2025). “True” Accessibility Barriers of Heritage Buildings. Buildings, 15(9), 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091528