Evaluating the Experiential Value of Public Spaces in Resettlement Communities from the Perspective of Older Adults: A Case Study of Fuzhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Age-Friendly Design of Community Public Spaces

2.2. Characteristics of Resettlement Communities

2.3. Definition and Dimensions of Experiential Value

2.4. Evaluation Frameworks for Public Space Experiences

3. Materials and Methods

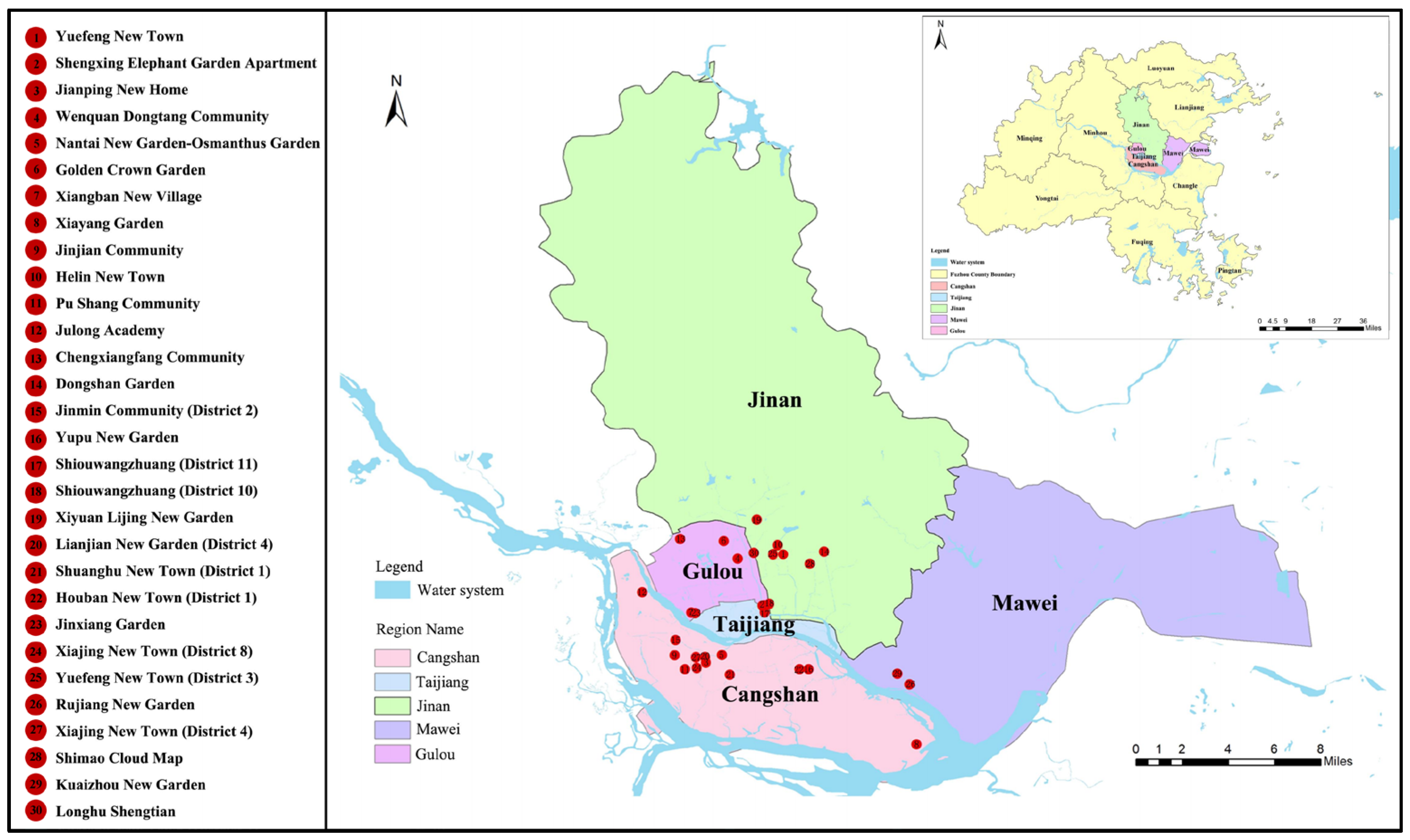

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Design

3.2.1. Questionnaire Design and Determination of Evaluation Indicators

- (1)

- Demographic Characteristics: basic respondent information was collected, including name, occupation, area of specialization, age, educational background, professional experience, and contact details.

- (2)

- Evaluation of Target Dimensions of Experiential Value in Public Spaces of Resettlement Communities: Four primary dimensions—functional value, contextual value, emotional value, and social value—were evaluated. Respondents assessed the relevance and importance of each dimension.

- (3)

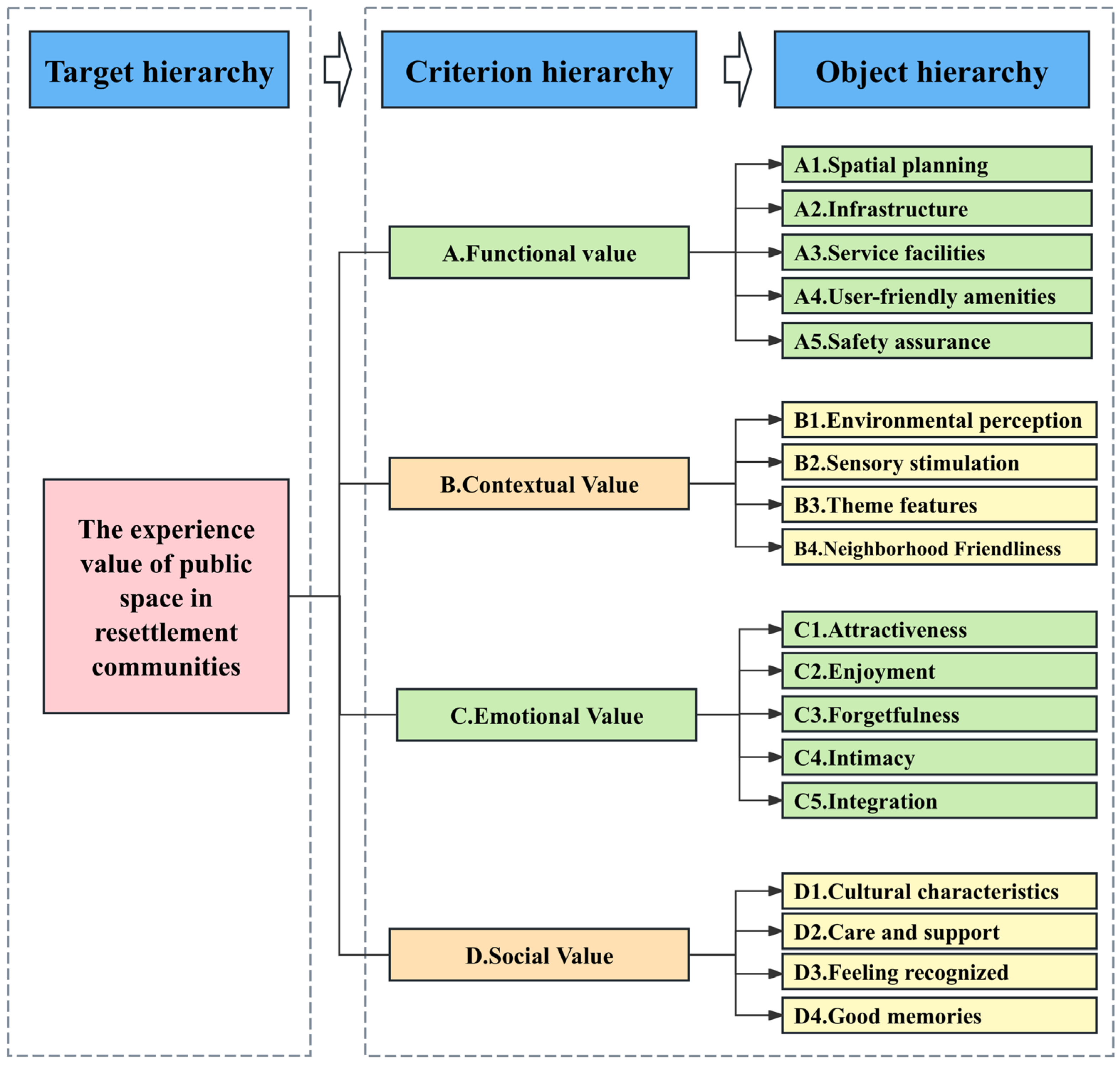

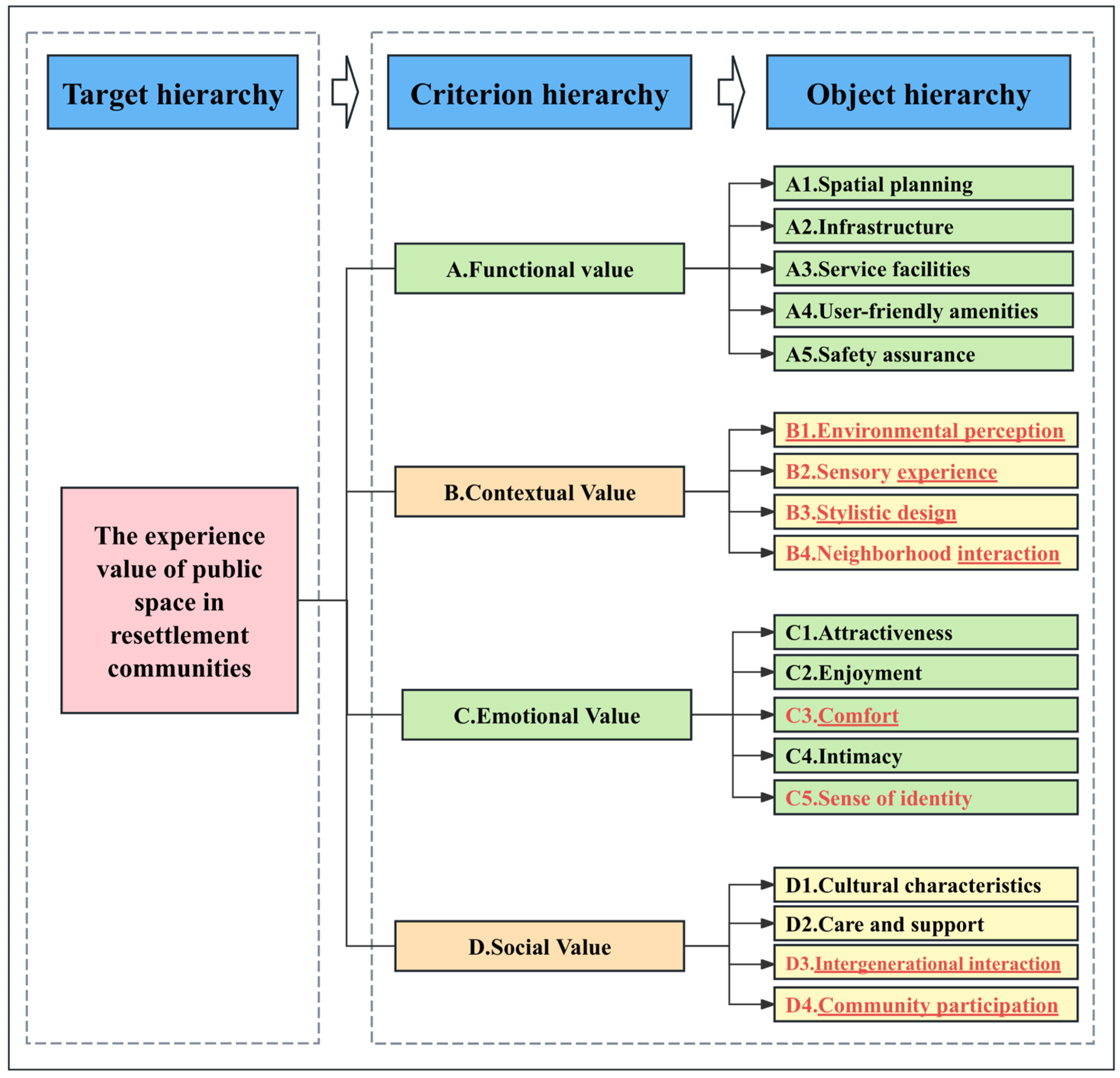

- Evaluation of Indicators for Experiential Value in Resettlement Communities’ Public Spaces: Specific design indicators were developed that were based on experiential value scales established by Varshneya et al. [25] and Wu et al. [45]. Through a literature review and preliminary screening, four dimensional indicators and eighteen detailed design criteria factors were identified (see Figure 3). These frameworks formed the basis of the expert questionnaire survey, allowing for further evaluation and refinement in order to ensure the scientific validity and applicability of the selected design indicators. These frameworks provided the foundation for the expert questionnaire survey, facilitating subsequent evaluation and refinement processes to ensure the scientific validity and practical applicability of the selected design indicators.

3.2.2. Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (Fuzzy AHP)

3.2.3. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation (FCE)

4. Research Results

4.1. Selection of Evaluation Indicators

4.2. Establishment of the Evaluation Indicator System

4.3. Empirical Analysis

4.3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

4.3.2. Evaluation Results of Public Space Experiential Values in Resettlement Communities

4.3.3. Analysis of Evaluation Dimensions

- (1)

- Functional Value: Good Infrastructure; Service Facilities Need Improvement

- (2)

- Environmental Value: High Environmental Perception; Stylistic Design Needs Optimization

- (3)

- Emotional Value: Comfortable Spaces; Sense of Intimacy Needs Strengthening

- (4)

- Social Value: Weak Cultural Characteristics; Community Participation Needs Improvement

4.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Evaluation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Findings and Theoretical Contributions

- (1)

- Research Findings

- (2)

- Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

- (1)

- Improving Service Facilities and Enhancing Spatial Diversity

- (2)

- Optimizing Spatial Design to Enhance Environmental Quality

- (3)

- Strengthening Social Interactions and Promoting Cultural Identity

- (4)

- Enhancing Safety Measures to Create Livable Environments

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Revision of World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, T. Urbanization Impacts on Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions of the Water Infrastructure in China: Trade-Offs among Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttarak, R. Demographic Perspectives in Research on Global Environmental Change. Popul. Stud. 2021, 75 (Suppl. 1), 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2022 National Economic and Social Development. Available online: https://is.gd/A2a6rr (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Lai, Y.; Wang, P.; Wen, K. Exploring the Impact of Public Spaces on Social Cohesion in Resettlement Communities from the Perspective of Experiential Value: A Case Study of Fuzhou, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebauer, S.; Winkler, C. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Factors in Household Decisions for or Against Relocation from a Flood Risk Area. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 60, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E.H.W. Social Needs of the Elderly and Active Aging in Public Open Spaces in Urban Renewal. Cities 2016, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Tian, J. Community Participation, Social Capital Cultivation and Sustainable Community Renewal: A Case Study from Xi’an’s Southern Suburbs, China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 11007–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Paragon House: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Older People’s Neighborhood Satisfaction and Well-Being: A Capability Approach Framework for Community Facility Planning in Urban Old District. Land 2023, 12, 16257. [Google Scholar]

- Yashadhana, A.; Alloun, E.; Serova, N.; de Leeuw, E.; Mengesha, Z. Place-Making and Its Impact on Health and Wellbeing among Recently Resettled Refugees in High-Income Contexts: A Scoping Review. Health Place 2023, 81, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, N.; Díaz-Foncea, M.; Marcuello, C.; Tortia, E. Social Incubators and Social Innovation in Cities: A Qualitative Analysis; CIRIEC International, Université de Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.W.; Zhang, J.R.; Tzeng, G.H.; Huang, S.L.; Xiong, L. Public Open Space Development for Elderly People by Using the DANP-V Model to Establish Continuous Improvement Strategies towards a Sustainable and Healthy Aging Society. Sustainability 2017, 9, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmistu, S.; Kotval, Z. Spatial Interventions and Built Environment Features in Developing Age-Friendly Communities from the Perspective of Urban Planning and Design. Cities 2023, 141, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.C.; Gao, D.R.; Lee, C.Y.; Li, X.; Sun, X.Y.; Chen, C.T. Influence of Promoting an “Age-Friendly Cities” Strategy on Psychological Capital and Social Engagement Based on the Scenario Method. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2023, 35, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Heng, C.K.; Fung, J.C. Using Walk-Along Interviews to Identify Environmental Factors Influencing Older Adults’ Out-of-Home Behaviors in a High-Rise, High-Density Neighborhood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.T.; Yang, N.; Xu, F.; Xing, Y.X. Research on the Evaluation and Optimization of Community Public Spaces under a Multi-Dimensional Health-Oriented Approach—A Case Study of Jialingdao Area, Nankai District, Tianjin. South Archit. 2023, 3, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.K. The State, Ethnic Community, and Refugee Resettlement in Japan. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2018, 53, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fozdar, F.; Hartley, L. Refugee Resettlement in Australia: What We Know and Need to Know. Refugee Surv. Q. 2013, 32, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qian, Z. Urbanization through Resettlement and the Production of Space in Hangzhou’s Concentrated Resettlement Communities. Cities 2022, 129, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tang, B.S.; Chan, E.H. State-Led Land Requisition and Transformation of Rural Villages in Transitional China. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research; Psychology Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nysveen, H.; Oklevik, O.; Pedersen, P.E. Brand Satisfaction: Exploring the Role of Innovativeness, Green Image and Experience in the Hotel Sector. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2908–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. A Qualitative Pilot Study Exploring Tourists’ Pre- and Post-Trip Perceptions on the Destination Image of Macau. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; So, K.K.F. Two Decades of Customer Experience Research in Hospitality and Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis and Thematic Content Analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Notes on Measuring Recreational Place Attachment; Williams, D., Ed.; Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2000; Unpublished Report.

- Varshneya, G.; Das, G. Experiential Value: Multi-Item Scale Development and Validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, P. Measuring the Effects of Multi-Sensory Stimuli in the Mixed Reality Environment for Tourism Value Creation. Ph.D. Thesis, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, R.; Ahtola, O.T. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Sources of Consumer Attitudes. Mark. Lett. 1991, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yrjölä, M.; Rintamäki, T.; Saarijärvi, H.; Joensuu, J.; Kulkarni, G. A Customer Value Perspective to Service Experiences in Restaurants. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskett, J.L.; Sasser, W.E. Southwest Airlines: In a Different World; Harvard Business School Case 910–419; Harvard Business School Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating Public Space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Principles for Public Space Design, Planning to Do Better. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; Conservation Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. Big Data, Smart Cities and City Planning. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2013, 3, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertman, S.; Allan, A.; Pettit, C.; Stillwell, J. Planning Support Systems and Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pafka, E.; Dovey, K. The Urban Density Assemblage: Modelling Multiple Measures. Urban Des. Int. 2017, 22, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X. Big Data and Machine Learning for Urban Planning: A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102466. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D. How Do Users Experience the Interaction with an Immersive Screen? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 98, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.K.; Zhang, X.L. Discussion on the Historical Evolution of Urban Housing Demolition Systems. Constr. Budg. 2014, 4, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, M.Y.; Li, T. A Study of Experiential Quality, Experiential Value, Experiential Satisfaction, Theme Park Image, and Revisit Intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 26–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M. Fuzzy AHP and Its Application to Risk Evaluation. J. Jpn. Soc. Fuzzy Theory Syst. 1991, 3, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.G.; Wang, X.L.; Li, G. Application of Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process in Supply Chain Management. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2022, 40, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simiyu, S.N.; Kweyu, R.M.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Adjei, K.A. Barriers and Opportunities for Cleanliness of Shared Sanitation Facilities in Low-Income Settlements in Kenya. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simiyu, S.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Adjei, K.; Kweyu, R. Developing and Testing Strategies for Improving Cleanliness of Shared Sanitation in Low-Income Settlements of Kisumu, Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 105, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewiola, H. Child-Friendliness of Urban Space in the Example of Łabędy. Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2023, 16, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, B.; Cilliers, J.; Lategan, L. Spatial Planning Guidelines for Child-Friendly Spaces: An African Perspective. Rural Soc. 2022, 31, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Hwang, T.; Kim, G. The Role and Criteria of Advanced Street Lighting to Enhance Urban Safety in South Korea. Buildings 2024, 14, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Illuminating Safety: The Impact of Street Lighting on Reducing Fear of Crime in a Virtual Environment. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Wang, J. Research on the Optimal Design of Community Public Space from the Perspective of Social Capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Lu, J.; Shao, Y. Exploring the Impact of Visual and Aural Elements in Urban Parks on Human Behavior and Emotional Responses. Land 2024, 13, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Hu, J.; Gao, X. Community Life Circle, Neighbourly Interaction, and Social Cohesion: Does Community Space Use Foster Stronger Communities? Land 2024, 13, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, E.; Hansen, L.E.; Djupdræt, M.B. Museums as Public Spaces in the City: Insights from Aarhus, Denmark. Cities 2025, 159, 10577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, M.; Görig, T.; Georg, S.; Hoffmann, D.; Sonntag, D.; Philippi, H.; König, J.; Urschitz, M.S.; De Bock, F. Evaluation of a Complex Intervention to Strengthen Participation-Centred Care for Children with Special Healthcare Needs: Protocol of the Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised PART-CHILD Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova-Zinkevič, I.; Podvezko, V.; Zavadskas, E.K. Comparative Assessment of the Stability of AHP and FAHP Methods. Symmetry 2021, 13, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, D.; Jana, A. Assessing Urban Recreational Open Spaces for the Elderly: A Case of Three Indian Cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 35, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Jiménez, A.; Blandón-González, B.; Barrios-Padura, Á. Towards a Built Environment without Physical Barriers: An Accessibility Assessment Procedure and Action Protocol for Social Housing Occupied by the Elderly. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Lin, Z.; Vojnovic, I.; Qi, J.; Wu, R.; Xie, D. Social Environments Still Matter: The Role of Physical and Social Environments in Place Attachment in a Transitional City, Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 232, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrentzen, S.; Tural, E. The Role of Building Design and Interiors in Ageing Actively at Home. J. Hous. Elder. 2015, 29, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demolition and Resettlement Era | Number of Communities | Placement Model | Community Overview |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–2001 | 120 | On-site resettlement | Residential buildings in these communities typically include walk-up apartments and apartment blocks with elevators that have been retrofitted at later stages. Such communities are characterized by densely built environments, limited public spaces, insufficient recreational areas, and a pronounced lack of essential infrastructure. |

| 2002–2011 | 227 | On-site resettlement and off-site resettlement | Depending on community scale, residential buildings include both walk-up apartments and elevator-equipped apartment blocks. Additionally, infrastructure such as public spaces, green belts, and landscape design has been subject to continuous improvement. |

| 2012–Present | 156 | On-site resettlement and off-site resettlement | Characterized by high-rise apartment buildings equipped with elevators, these communities feature well-developed infrastructure. Notably, there has been a substantial advancement in the quality and availability of parks, gardens, and leisure facilities, resulting in marked improvements in overall environmental quality. |

| Category | Code | Job Title | Professional Field | Age | Years of Professional Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Expert | D01 | Senior Designer | Urban Planning | 31~40 | 0~5 years (inclusive) |

| D02 | Senior Designer | Design Studies | 31~40 | 6~10 years (inclusive) | |

| D03 | Senior Designer | Design Studies | 31~40 | 11~15 years (inclusive) | |

| D04 | Senior Designer | Design Studies | 31~40 | 11~15 years (inclusive) | |

| D05 | Senior Designer | Design Studies | 31~40 | 11~15 years (inclusive) | |

| D06 | Senior Designer | Architecture | 31~40 | 11~15 years (inclusive) | |

| D07 | Senior Designer | Landscape Architecture | 31~40 | 11~15 years (inclusive) | |

| D08 | Senior Designer | Urban Planning | 31~40 | 11~15 years (inclusive) | |

| D09 | Design Director | Urban Planning | 41~50 | 16 years or more | |

| D10 | Project Lead | Architecture | 41~50 | 16 years or more | |

| Academic Expert | S01 | Lecturer | Design Studies | 31~40 | 0~5 years (inclusive) |

| S02 | Lecturer | Landscape Architecture | 31~40 | 6~10 years (inclusive) | |

| S03 | Lecturer | Design Studies | 31~40 | 6~10 years (inclusive) | |

| S04 | Associate Professor | Design Studies | 31~40 | 6~10 years (inclusive) | |

| S05 | Associate Professor | Design Studies | 31~40 | 11~15 years (inclusive) | |

| S06 | Associate Professor | Sociology | 41~50 | 16 years or more | |

| S07 | Associate Professor | Architecture | 51~60 | 16 years or more | |

| S08 | Associate Professor | Architecture | 41~50 | 16 years or more | |

| S09 | Associate Professor | Urban Planning | 51~60 | 16 years or more | |

| S10 | Professor | Architecture | 51~60 | 16 years or more |

| Criterion | Definition | Type | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Functional Value | Perceptual evaluation of the use and design of community public space functions. | Benefit | [29,45] |

| A1. Spatial planning | The layout of the community public space is reasonably planned according to the functional requirements in order to ensure convenient traffic routes and to pay attention to the continuity and interaction of space. | [35] | |

| A2. Infrastructure | The extent to which infrastructure such as road traffic, streetlights, communication services, safety facilities, and education and medical facilities are established within the community. | [5] | |

| A3. Service facilities | The completeness and service quality of catering, recreation, community service facilities (such as community centers), and sanitation and cleaning facilities within 1 km of the community. | [49,50] | |

| A4. User-friendly amenities | The community public space is equipped with age-appropriate and child-friendly facilities to ensure that the functional areas are reasonably planned and smoothly connected. | [51,52] | |

| A5. Safety assurance | The public space of the community is equipped with safety guarantee designs such as emergency buttons, sentry settings, and streetlight illumination design to ensure the perfect and effective implementation of safety protection measures. | [53,54] | |

| B. Contextual Value | Perception and evaluation of situational elements such as environmental atmosphere and interactive scenes created in community public spaces. | Benefit | [29,45] |

| B1. Environmental perception | The overall perceptual experience of community public space is shaped by multidimensional factors such as physical design, environmental esthetics, and social interaction. | [55] | |

| B2. Sensory experience | The communal spaces of the community allow residents to have a rich sensory experience, including sight, hearing, smell, etc. | [56] | |

| B3. Stylistic design | The stylistic design of the community public space should maintain coherence and consistency. | [37] | |

| B4. Neighborhood interaction | Community public spaces provide areas that promote neighborhood interaction, support community events and gatherings, and provide an environment for residents to connect. | [57] | |

| C. Emotional Value | The perception and evaluation of residents’ common emotional experience in community public space. | Benefit | [29,45] |

| C1. Attractiveness | Activities in the public spaces of the resettlement community continue to engage residents (e.g., community fitness activities, holiday celebrations, etc.). | [5] | |

| C2. Enjoyment | Participating in community-organized activities (e.g., sports days and folk festivals) keeps residents happy. | [5] | |

| C3. Comfort | In the resettlement community public space, a comfortable environment can promote physical and mental relaxation and emotional regulation so that residents can obtain emotional healing and psychological peace. | [5] | |

| C4. Intimacy | Within the scope of the resettlement community, intimacy may be formed by the interaction between property management personnel, security guards, community party branches, and residents. | [5] | |

| C5. Sense of identity | Participate in resettlement-oriented community volunteer activities (such as environmental protection and cleaning and helping disadvantaged groups) to make residents feel that they belong to the community. | [5] | |

| D. Social Value | Perception and evaluation of the relationship with neighbors in the public space of the community. | Benefit | [29,45] |

| D1. Cultural characteristics | Residents of the community can feel the unique culture of the region (temples, theaters, etc.). | [58] | |

| D2. Care and support | In the public space, residents can form an informal network of social relationships, such as the elderly and children through activities in squares and parks, as well as receiving support and care from neighbors. | [59] | |

| D3. Intergenerational Interaction | The community public space provides a platform for residents of different ages to engage in common activities and exchanges, promoting intergenerational interaction. | [59] | |

| D4. Community participation | Residents participate in community affairs through community public space, accumulate social capital, and promote the improvement of community autonomy and governance capabilities. | [55] |

| Target Dimension | First Round: Importance | Second Round: Importance | Paired-Sample Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | C.V. | Mean | S.D. | C.V. | t-Value | p-Value | |

| A. Functional value | 4.6 | 0.95 | 0.20 | 4.8 | 0.41 | 0.09 | −1.073 | 0.297 |

| B. Contextual value | 3.9 | 1.17 * | 0.30 | 4.05 | 0.51 | 0.13 | −0.645 | 0.527 |

| C. Emotional value | 3.8 | 1.15 * | 0.30 | 4.15 | 0.67 | 0.16 | −1.437 | 0.167 |

| D. Social value | 4.3 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 4.35 | 0.59 | 0.14 | −0.213 | 0.834 |

| Design Criteria | First Round: Importance | Second Round: Importance | Paired-Sample Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | C.V. | Mean | S.D. | C.V. | t-Value | p-Value | |

| A1. Spatial Planning | 4.5 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 4.85 | 0.37 | 0.08 | −2.333 | 0.031 |

| A2. Infrastructure | 4.7 | 0.57 | 0.12 | 4.6 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.567 | 0.577 |

| A3. Service Facilities | 4.1 | 1.12 * | 0.27 | 4.05 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.195 | 0.847 |

| A4. User-friendly Amenities | 4.5 | 0.69 | 0.15 | 4.35 | 0.59 | 0.14 | 0.900 | 0.379 |

| A5. Safety Assurance | 4.45 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 4.35 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.525 | 0.606 |

| B1. Environmental Perception | 3.95 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 4 | 0.46 | 0.12 | −0.326 | 0.748 |

| B2. Sensory Experience | 3.25 | 1.45 * | 0.45 * | 4 | 0.46 | 0.12 | −2.263 | 0.036 |

| B3. Stylistic Design | 3.65 | 0.88 | 0.24 | 3.85 | 0.67 | 0.17 | −1.000 | 0.330 |

| B4. Neighborhood Interaction | 4.35 | 0.75 | 0.17 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 0.11 | −1.000 | 0.330 |

| C1. Attractiveness | 3.9 | 1.12 * | 0.29 | 4.1 | 0.72 | 0.18 | −0.639 | 0.530 |

| C2. Enjoyment | 3.45 | 1.15 * | 0.33 * | 4.05 | 0.76 | 0.19 | −2.259 | 0.036 |

| C3. Comfort | 3.3 | 1.03 * | 0.31 * | 4.5 | 0.61 | 0.14 | −3.835 | 0.001 |

| C4. Intimacy | 3.35 | 1.31 * | 0.39 * | 4 | 0.56 | 0.14 | −2.041 | 0.055 |

| C5. Sense of Identity | 3.6 | 1.19 * | 0.33 * | 4.25 | 0.72 | 0.17 | −2.096 | 0.050 |

| D1. Cultural Characteristics | 3.95 | 1.10 * | 0.28 | 4.1 | 0.79 | 0.19 | −0.531 | 0.614 |

| D2. Care and Support | 4.2 | 0.62 | 0.19 | 4.05 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0.767 | 0.453 |

| D3. Intergenerational Interaction | - | - | - | 4 | 0.79 | 0.20 | - | - |

| D4. Community Participation | - | - | - | 4.1 | 0.77 | 0.18 | - | - |

| Scale Value | Definition | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Equally Important | Two evaluation indicators are equally important. |

| 0.6 | Slightly Important | Between two indicators, the former is slightly more important than the latter. |

| 0.7 | Clearly Important | Between two indicators, the former is clearly more important than the latter. |

| 0.8 | Strongly Important | Between two indicators, the former is strongly more important than the latter. |

| 0.9 | Extremely Important | Between two indicators, the former is extremely more important than the latter. |

| 0.1–0.4 | Inverse Comparison | Between two indicators, there is an inverse comparison: . |

| Primary Criterion | Weight | Secondary Criterion | Local Weight | Global Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Functional Value | 0.2675 | A1. Spatial Planning | 0.2195 | 0.0587 |

| A2. Infrastructure | 0.2024 | 0.0541 | ||

| A3. Service Facilities | 0.2081 | 0.0557 | ||

| A4. User-friendly Amenities | 0.1990 | 0.0532 | ||

| A5. Safety Assurance | 0.1710 | 0.0457 | ||

| B. Contextual Value | 0.2595 | B1. Environmental Perception | 0.2587 | 0.0671 |

| B2. Sensory Experience | 0.2571 | 0.0667 | ||

| B3. Stylistic Design | 0.2508 | 0.0651 | ||

| B4. Neighborhood Interaction | 0.2333 | 0.0606 | ||

| C. Emotional Value | 0.2532 | C1. Attractiveness | 0.2331 | 0.0590 |

| C2. Enjoyment | 0.2019 | 0.0511 | ||

| C3. Comfort | 0.1914 | 0.0485 | ||

| C4. Intimacy | 0.1912 | 0.0484 | ||

| C5. Sense of Identity | 0.1824 | 0.0462 | ||

| D. Social Value | 0.2198 | D1. Cultural Characteristics | 0.2794 | 0.0614 |

| D2. Care and Support | 0.2480 | 0.0545 | ||

| D3. Intergenerational Interaction | 0.2353 | 0.0517 | ||

| D4. Community Participation | 0.2373 | 0.0522 |

| Name | Options | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 97 |

| Woman | 175 | |

| Children | Have children | 226 |

| Childless | 6 | |

| Educational Attainment | High School and Below | 136 |

| College Specialty | 67 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 23 | |

| Graduate Student or Above | 6 | |

| Occupation | Housewife/Husband | 12 |

| Freelance Work | 36 | |

| Retirement | 92 | |

| Public Institutions or Civil Servants | 20 | |

| Business Personnel | 72 | |

| Length of Residence | Less than 1 year | 3 |

| 1–5 years | 21 | |

| 6–10 years | 32 | |

| More than 10 years | 176 | |

| Frequency of Participation Space/Monthly | Never | 7 |

| Occasionally (1–2 times) | 69 | |

| Frequently (3–5 times) | 99 | |

| Every day | 57 | |

| Sum | 232 | |

| Hierarchy Level | Evaluation Score | Primary Criterion | Evaluation Score | Secondary Criterion | Evaluation Score | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiential Value | 88.826 | A. Functional Value | 89.113 | A1. Spatial Planning | 89.138 | 9 |

| A2. Infrastructure | 91.034 | 2 | ||||

| A3. Service Facilities | 87.802 | 14 | ||||

| A4. User-friendly Amenities | 90.258 | 4 | ||||

| A5. Safety Assurance | 87.113 | 15 | ||||

| B. Contextual Value | 89.146 | B1. Environmental Perception | 90.388 | 3 | ||

| B2. Sensory Experience | 89.742 | 5 | ||||

| B3. Stylistic Design | 86.939 | 17 | ||||

| B4. Neighborhood Interaction | 89.484 | 7 | ||||

| C. Emotional Value | 89.113 | C1. Attractiveness | 88.577 | 12 | ||

| C2. Enjoyment | 89.571 | 6 | ||||

| C3. Comfort | 91.467 | 1 | ||||

| C4. Intimacy | 87.026 | 16 | ||||

| C5. Sense of Identity | 89.009 | 10 | ||||

| D. Social Value | 87.77 | D1. Cultural Characteristics | 85.172 | 18 | ||

| D2. Care and Support | 89.482 | 8 | ||||

| D3. Intergenerational Interaction | 88.622 | 11 | ||||

| D4. Community Participation | 88.19 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lai, Y.; Wang, P. Evaluating the Experiential Value of Public Spaces in Resettlement Communities from the Perspective of Older Adults: A Case Study of Fuzhou, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091495

Lai Y, Wang P. Evaluating the Experiential Value of Public Spaces in Resettlement Communities from the Perspective of Older Adults: A Case Study of Fuzhou, China. Buildings. 2025; 15(9):1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091495

Chicago/Turabian StyleLai, Yafeng, and Pohsun Wang. 2025. "Evaluating the Experiential Value of Public Spaces in Resettlement Communities from the Perspective of Older Adults: A Case Study of Fuzhou, China" Buildings 15, no. 9: 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091495

APA StyleLai, Y., & Wang, P. (2025). Evaluating the Experiential Value of Public Spaces in Resettlement Communities from the Perspective of Older Adults: A Case Study of Fuzhou, China. Buildings, 15(9), 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091495