Historic District Conservation: A Critical Review of Global Trends, Development in the 21st Century, and Challenges Through CiteSpace Analysis

Abstract

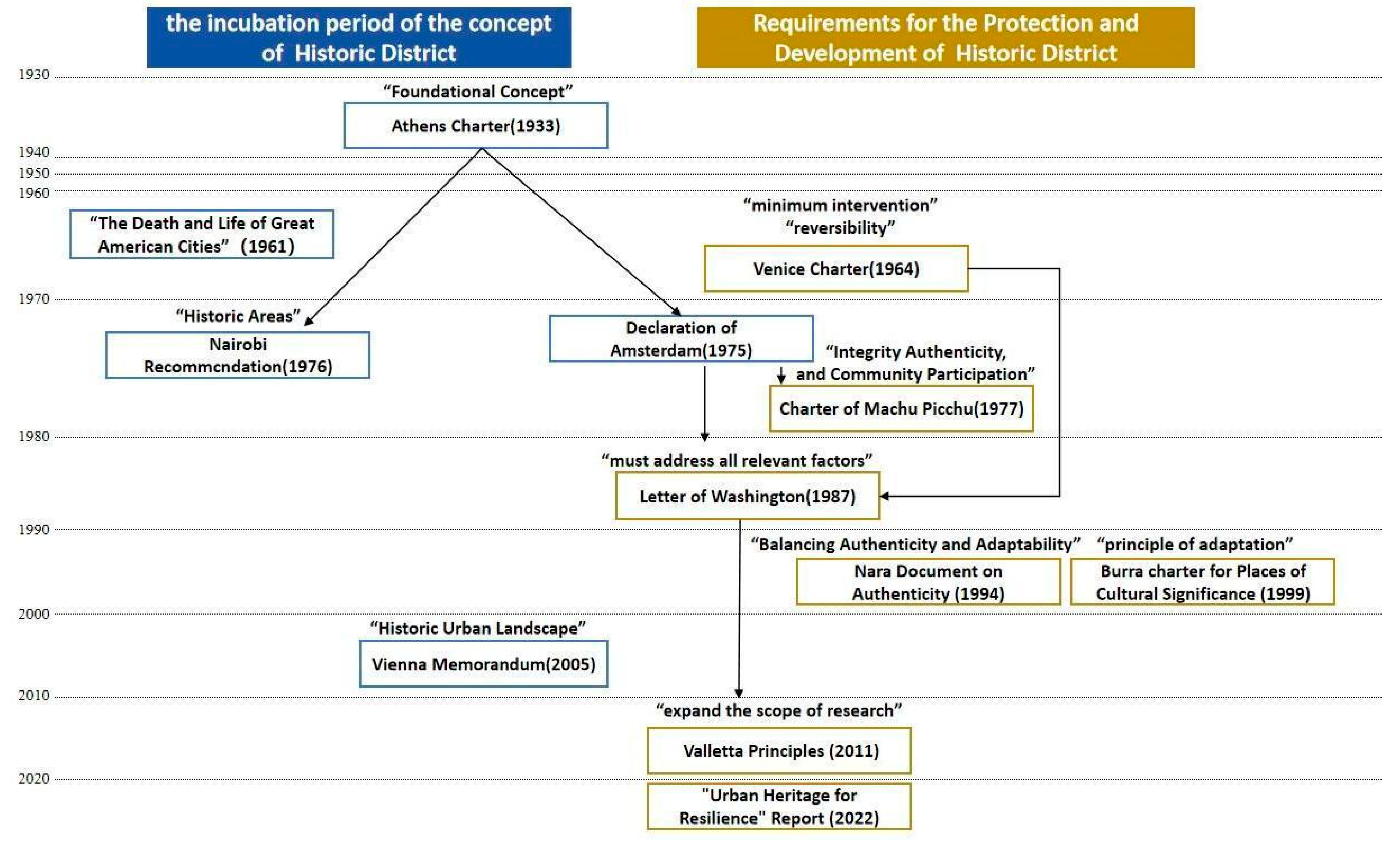

1. Introduction

2. Research Materials, Methods and Process

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

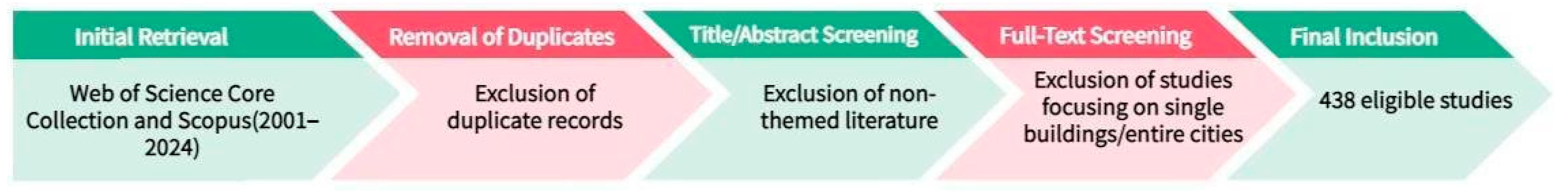

2.3. Research Process

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

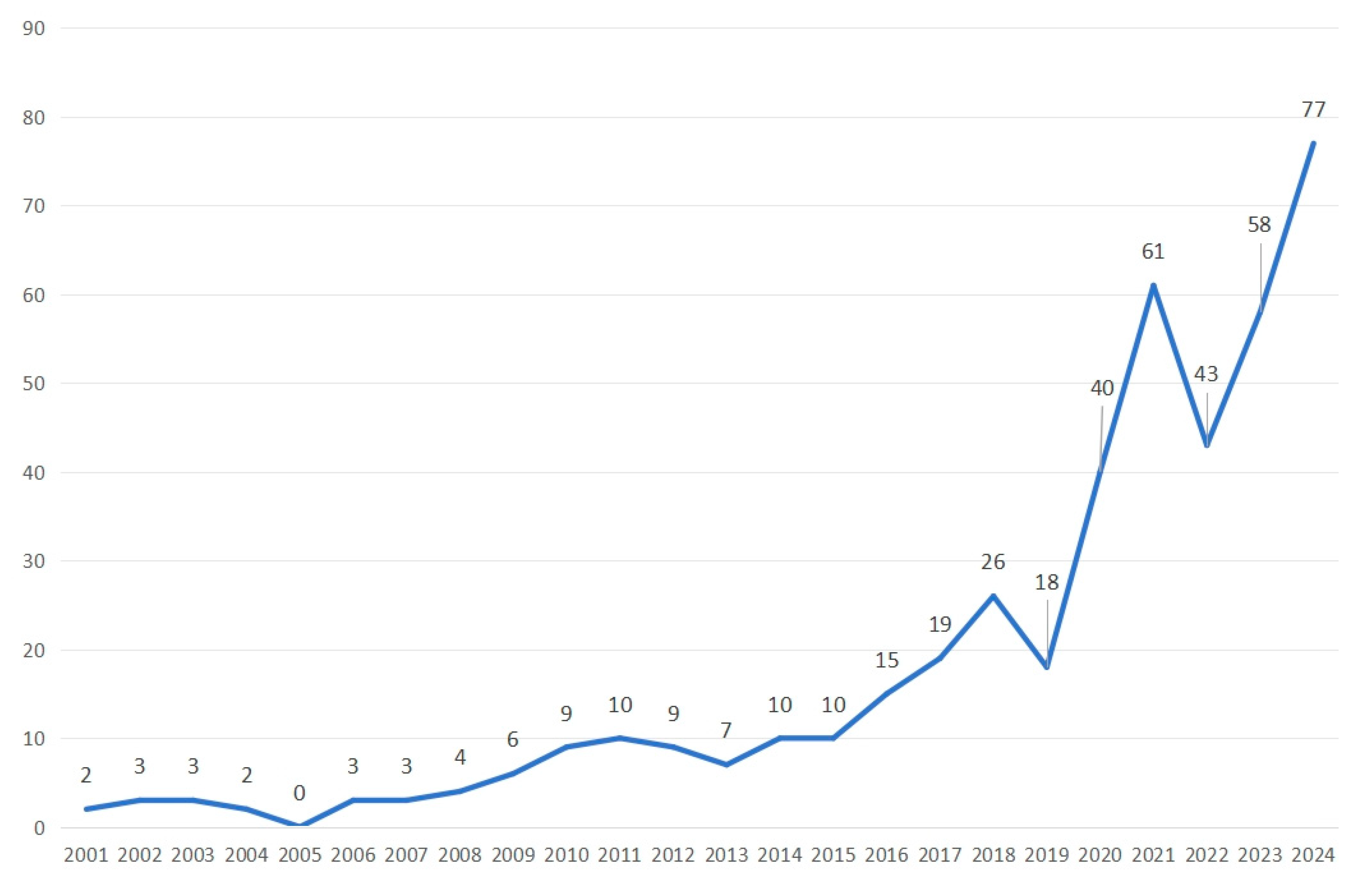

3.1.1. Publication Trends

3.1.2. Geographical Distribution

3.1.3. Cited Journals

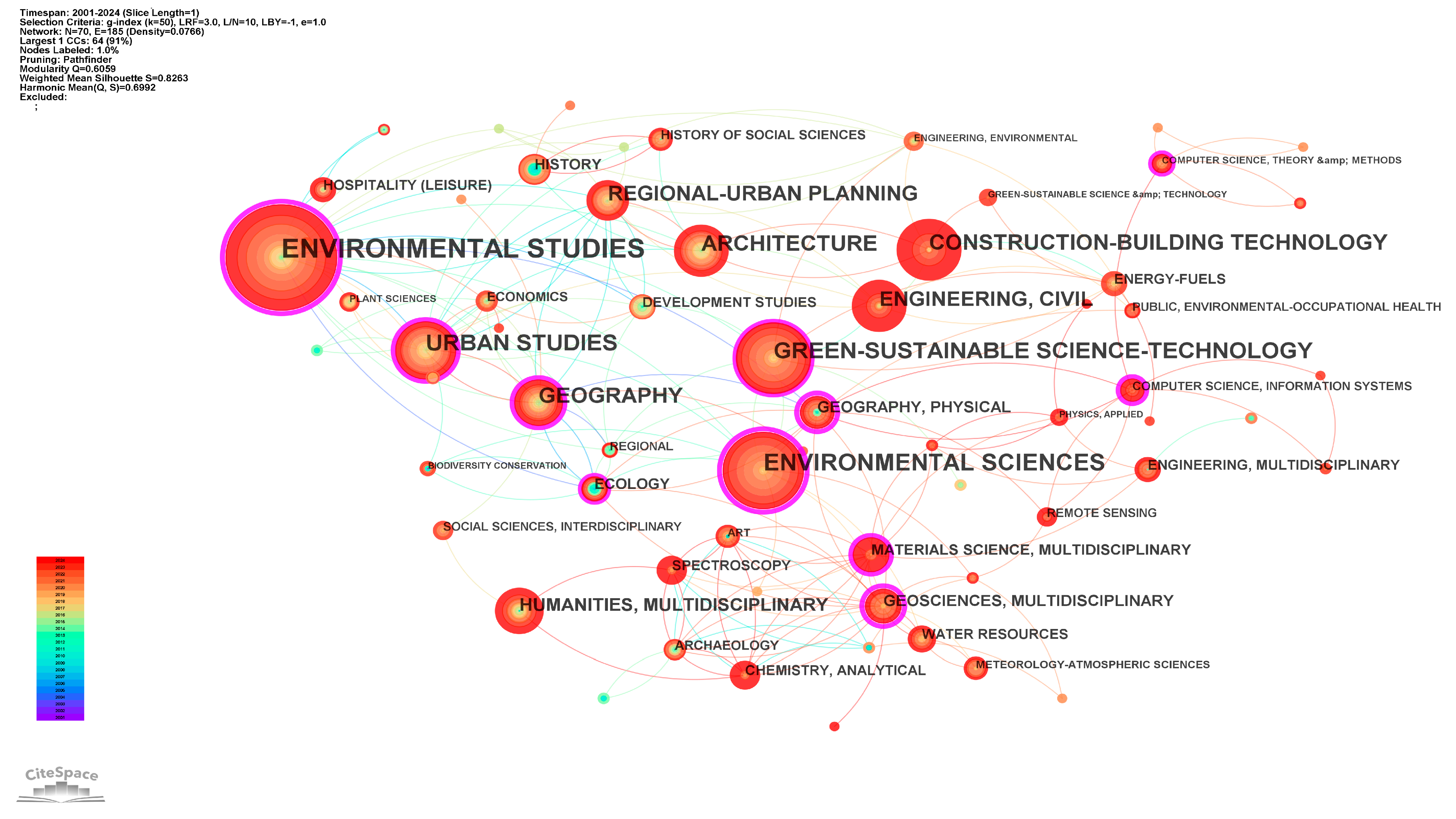

3.1.4. Research Subjects

3.2. Academic Groupings and Research Focus

3.2.1. Keyword Research Areas

- Research Scope

- Research Methods and Research Strategy

- Emerging Trends

3.2.2. Clustering Analysis of Keywords

3.2.3. Landmark References

4. Key Issues in the Research of Historic Districts

4.1. Conceptual Research

4.2. Conservation

4.3. Development Strategies and Technologies

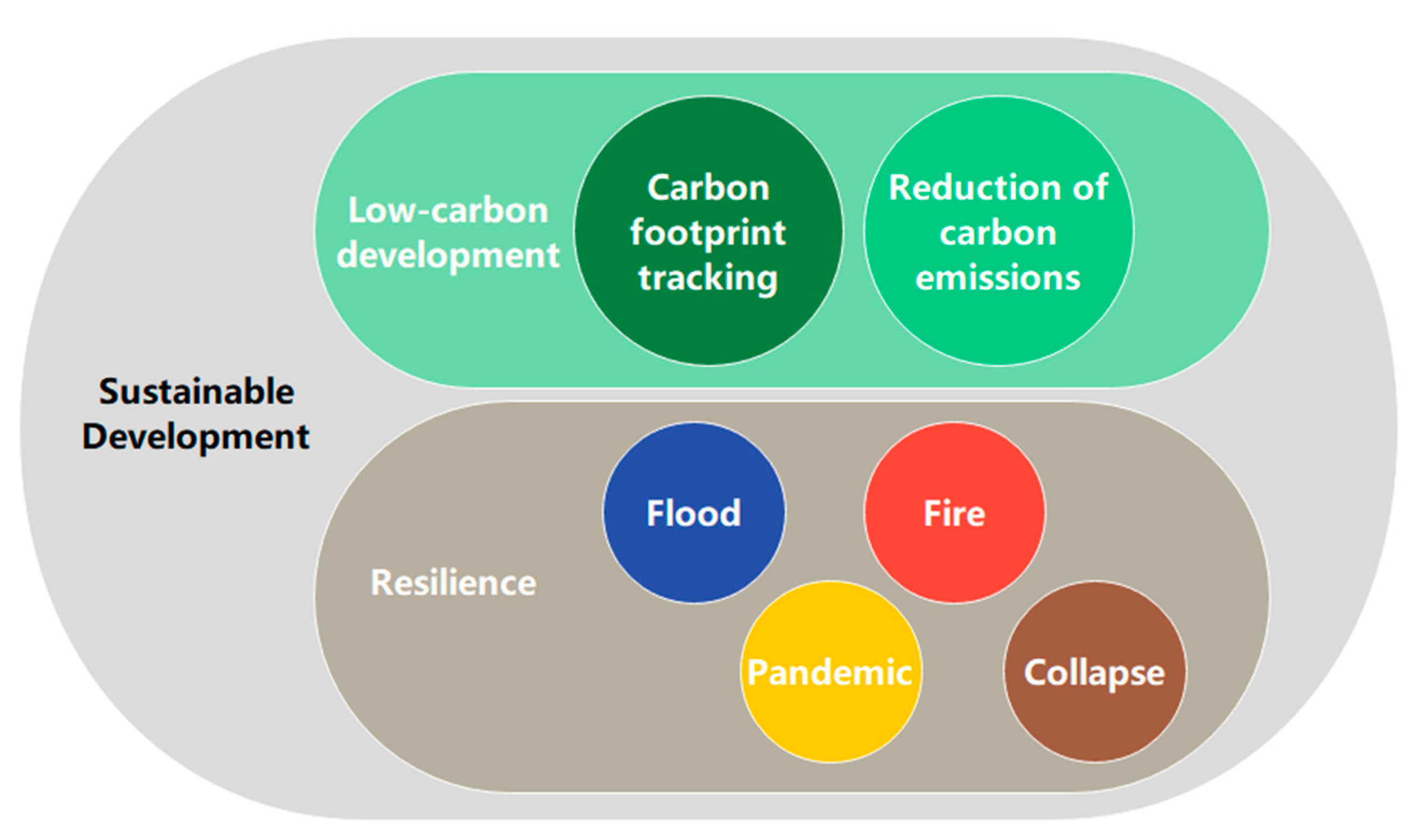

4.4. Sustainable Development

4.5. Urban Renewal Strategies

4.6. Community Participation

5. Conclusions

5.1. Comparative Analysis with Related Bibliometric Studies

5.2. Key Conclusions of Historic District Conservation Research and Their Reflections in Practice

- Conceptual Development and Application Dilemmas

- Research Achievements and Disciplinary Trends

- Research Clusters and Methodological Innovations

- Gap between Theory and Practice and Future Directions

6. Discussion

6.1. Trends: Future Prospects for Historic District Conservation

- Strengthening of Holistic and Comprehensive Conservation

- Increasing Significance of Interdisciplinary Research

- Development Opportunities from New Technologies

6.2. Challenges: Barriers to Effective Conservation

- Challenge of Defining the Concept Clearly

- Challenge of Disciplinary Integration

- Challenge of Technology Application and Problem Simplification

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dimelli, D. Modern Conservation Principles and Their Application in Mediterranean Historic Centers—The Case of Valletta. Heritage 2019, 2, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, A.K. Where is the history in historic districts?: Introduction. Public Hist. 2010, 32, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchini, C. Cultural paradigm inertia and urban tourism. In The Future of Tourism: Innovation and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylworth, S. A Multifaceted Approach to Historic District Interpretation in Georgia. Public Hist. 2010, 32, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, E.P. The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928–1960; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hamer, D. Learning from the past: Historic districts and the new urbanism in the United States. Plan. Perspect. 2000, 15, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzet, M. Principles of preservation: An introduction to the international charters for conservation and restoration 40 years after the Venice Charter. In International Charters for Conservation and Restoration; Monuments and Sites; ICOMOS: München, Germany, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cucco, P. Dalla Conservazione Integrata di Amsterdam (1975) all’Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage (2020). Nuove prospettive nello scenario di cambiamenti globali. Esempi Archit. Int. J. Archit. Eng. 2020, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Médard, C. City planning in Nairobi. In Nairobi Today; Mkuki na Nyota Publishers: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010; pp. 25–60. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS International Scientific Committee; ISPRS Permanent Committee (ISC). Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas. Adopted by ICOMOS General Assembly; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stovel, H. Origins and influence of the Nara document on authenticity. APT Bull. 2008, 39, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Truscott, M.; Young, D. Revising the Burra Charter: Australia ICOMOS updates its guidelines for conservation practice. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2000, 4, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, V. The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) as a new approach to the conservation of historic cities. Landsc. Imagin. 2012, 579. [Google Scholar]

- De Marco, L.; Hadzimuammedovich, A.; Kealy, L. ICOMOS-ICCROM Guidance on Post-Disaster and Post-Conflict Recovery and Reconstruction for Heritage Places of Cultural Significance and World Heritage Cultural Properties; ICOMOS & ICCROM: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari, E.; Lotfi, S.; Sholeh, M. HUL values in practice: A character area designation model for the conservation of built heritage in less-developed regions. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 70, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Recommendation on the historic urban landscape. In Proceedings of the Records of the General Conference 36th Session, Paris, France, 25 October–10 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L. International influence and local response: Understanding community involvement in urban heritage conservation in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, S. Humanistic needs and satisfaction study of multi-users in historic districts based on cognitive psychology. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33 (Suppl. S8), 681–693. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. The political economy of historic districts: The private, the public, and the collective. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 86, 103583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Science mapping: A systematic review of the literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2017, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace: A Practical Guide for Mapping Scientific Literature; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Tao, C.; Ding, R. Research hotspots and trends of cardiopulmonary exercise test: Visualization analysis based on citespace. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2022, 16, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Visualizing Patterns and Trends in Scientific Literature. Citespace 2012. Available online: http://cluster.cis.drexel.edu/~cchen/citespace/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Small, H. Co-citation in scientific literature-new measure of relationship between 2 documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1973, 24, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.L.; Ma, R.G.; Hu, Z.H. Review of Urban Transportation Network Design Problems Based on CiteSpace. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5735702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ibekwe-SanJuan, F.; Hou, J. The structure and dynamics of cocitation clusters: A multiple-perspective cocitation analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1386–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.P.; Zhou, D. Knowledge Map of Urban Morphology and Thermal Comfort: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on CiteSpace. Buildings 2021, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azkarate, A.; Azpeitia, A. Paisajes urbanos históricos¿ Paradigma o subterfugio. In Alla Ric. Di Un Passato Complesso. Contrib. Onore Di Gian Pietro Brogiolo Per Il Suo Settantesimo Compleanno; Universidad de Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016; pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik, J.B.; Zhou, Y. Are historic districts a backdoor for segregation? Yes and no. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2023, 41, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. Tourism development of historic and cultural district based on tourists’ experience. Econ. Res. Guide 2010, 109, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, S.K. Urban development in post-reform China: Insights from Beijing. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. J. Geogr. 2005, 59, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. World Heritage Site inscription and waterfront heritage conservation: Evidence from the Grand Canal historic districts in Hangzhou, China. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 16, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Nobuo, A.; Ruoran, W.; Xu, S. Development of cultural heritage conservation planning in China. Plan. Perspect. 2024, 39, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzarly, M.; Houbart, C.; Teller, J. The Historic Urban Landscape approach to urban management: A systematic review. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 999–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinberg, J. Bursty and hierarchical structure in streams. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 23–26 July 2002; pp. 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, M.; De la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Long, Y. Measuring visual quality of street space and its temporal variation: Methodology and its application in the Hutong area in Beijing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granda, S.; Ferreira, T.M. Assessing vulnerability and fire risk in old urban areas: Application to the historical centre of Guimarães. Fire Technol. 2019, 55, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Roders, A.P.; Van Wesemael, P. Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities 2020, 96, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, Y. Effects of soundscape perception on visiting experience in a renovated historical block. Build. Environ. 2019, 165, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban conservation. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, J. Revitalizing historic districts: Identifying built environment predictors for street vibrancy based on urban sensor data. Cities 2021, 117, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chiou, S.-C. A study on the sustainable development of historic district landscapes based on place attachment among tourists: A case study of Taiping old street, Taiwan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Malek, M.I.A.; Jaàfar, N.H.; Sima, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, Z. Unveiling the potential of space syntax approach for revitalizing historic urban areas: A case study of Yushan Historic District, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xin, J. Green Spaces and the Spontaneous Renewal of Historic Neighborhoods: A Case Study of Beijing’s Dashilar Community. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Qin, S.; Su, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q. Development of evaluation index model for activation and promotion of public space in the historic district based on AHP/DEA. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6590699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Xu, D.; Wang, T.; Wang, B. Analysis of Multi-Dimensional Layers in Historic Districts Based on Theory of the Historic Urban Landscape: Taking Shenyang Fangcheng as an Example. Land 2024, 13, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S. Conservation for sustainable development: The sustainability evaluation of the xijie historic district, dujiangyan city, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District - Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S.H.; Iqbal, N.; Van Cleempoel, K. Saddar bazar quarter in Karachi: A case of British-era protected heritage based on the literature review and fieldwork. Heritage 2023, 6, 3183–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderheggen, S. Four Decades of Local Historic District Designation: A Case Study of Newport, Rhode Island. Public Hist. 2010, 32, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, S.T.; Lombardi, A.; Korkmaz, K.A. Condition Assessment of Cultural Heritage Buildings in the Historic Strand District of Galveston. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Protection of Historical Constructions (PROHITECH), Athens, Greece, 25–27 October 2021; pp. 816–827. [Google Scholar]

- Septianto, E.; Poerbo, H.W.; Firmansyah; Martokusumo, W. Understanding the attractiveness of types of historic districts in Bandung: Implementing heritage conservation based on public perception. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Marzuki, A.; Rong, W.; Ran, X. An empirical application of the consumer-based authenticity model in heritage tourism of the George Town historic district, Penang, Malaysia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, X. A 3D spatial diagnostic framework of sustainable historic and cultural district preservation: A case study in Henan, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Wang, F. Cultural Identity and Continuity-Case Study of Authentic Conservation of Xi’an Bei Yuan Men Historic District. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 357, 1840–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.; Shi, T.; Zhao, J. Study on Authenticity Protection and Restoration of Residential Historic District. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 357, 1886–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, J.; Huo, X.W.; Zheng, W.H.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, M.M. Research on the positioning of protection and utilization of historic districts under big data analysis. In Proceedings of the 26th International Symposium of ICOMOS/ISPRS-International-Scientific-Committee-on-Heritage-Documentatio n (CIPA) on Digital Workflows for Heritage Conservation, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 28 August–1 September 2017; pp. 731–735. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.C.; Liu, S.; Wei, B.; Zhu, Z.N.; Wang, S.S. Using Wi-Fi Probes to Evaluate the Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Tourist Preferences in Historic Districts’ Public Spaces. Isprs Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; He, Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Lu, Y. Interplay between auditory and visual environments in historic districts: A big data approach based on social media. Environ. Plan. B-Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 1245–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Nik Hashim, N.H.; Goh, H.C. Public perception of cultural ecosystem services in historic districts based on biterm topic model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, R. Area-based protection mechanisms for heritage conservation: A European comparison. J. Archit. Conserv. 2002, 8, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl, M.H.; Sheta, S.A.; ElGizawi, L. Application of BIM/GIS-based Integrated Models on the Historic Urban Districts of Rosetta City, Egypt. Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2023, 13, 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, F.; Ren, Y.Y.; Goudos, S.; Zhao, Y. Analysis of Public Space in Historic Districts Based on Community Governance and Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81021–81032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.M. The Spatial Form of Traditional Taiwanese Townhouses: A Case Study of Dihua Street in Taipei City. In Proceedings of the 7th European-Mediterranean International Conference (EuroMed), Nicosia, Cyprus, 29 Octber–3 November 2018; pp. 322–333. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Ahmad, Y.; Mohidin, H.H.B. Spatial form and conservation strategy of Sishengci historic district in Chengdu, China. Heritage 2023, 6, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Q.; Sun, J.J.; Fu, J.Y. Research on Mixed Vitality of Historic District and Space Mode Optimization: A Comparison between Hefang Street and Xinyifang in Hangzhou. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 357–360, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. Variability of Land Surface Temperatures in Beijing’s Historic Districts. Sens. Mater. 2024, 36, 3147–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.B.; Li, X.M. Exploration on Traditional Courtyard Micro-Climate Characteristics and Improvement Method-Case Study of No. 6 Courtyard of Chang’anxue Alley in Xi’an Sanxuejie Historic District. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 357, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkova, A.; Krupenski, I.; Kovtunova, N.; Hlebnikov, A.; Masatin, V.; Ledvanov, A. Converting Tallinn’s historic centre’s (Old Town) heating system to a district heating system. Energy 2023, 275, 127429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.L.; Xu, B.X.; Wu, B.H. Assessing sustainable development of a historic district using an ecological footprint model: A case study of Nanluoguxiang in Beijing, China. Area 2017, 49, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Lückerath, D.; Zorita, S.; Silverton, S.; Garcia, G.; Servera, E.; Bonazza, A.; Garcia, I.; Kalis, A. Paving the way for climate neutral and resilient historic districts. Open Res. Eur. 2023, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; Li, J.Q.; Wang, Y.Z.; Liu, L. Thinking Critically through Key Issues in Improving the Effectiveness of Waterlogging Prevention and Control System in China’s Historic Districts. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahoon, D.M.; Abdel-Fattah, N.A.; Hegazi, Y.S. Social vulnerability of historic Districts: A composite measuring scale to statistically predict human-made hazards. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lou, S.J. The Road of Complexity, The Road of Rehabilitation-Discussion of Detailed Planning for Protection and Renovation of the Southeast Area in the Ancient City of Liaocheng. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 174–177, 2440–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J. Urban design of historic districts based on action planning. Open House Int. 2018, 43, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Revitalising Historic Urban Quarters; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 13–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, N. Planning for urban heritage places: Reconciling conservation, tourism, and sustainable development. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.R. Observing the Frame of Creative Clusters/Groups: A Case Study of Historic Districts in Tainan City. In Proceedings of the 2018 1st IEEE International Conference on Knowledge Innovation and Invention (ICKII), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 23–27 July 2018; pp. 168–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner, J.K. The past and future of Pioneer Square: Historic character and infill construction in Seattle’s First Historic District. Change Over Time 2017, 7, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Yang, J.Y. “Embedding” Updating Strategy Research of Urban Historic district-Taking South Historical District of Nanjing as example. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 397-400, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.H.; He, N.; Zhan, C.H. Evaluation of tree shade effectiveness and its renewal strategy in typical historic districts: A case study in Harbin, China. Environ. Plan. B-Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.Q.; Lu, A.D. How Diversity and Accessibility Affect Street Vitality in Historic Districts? Land 2023, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renne, J.L.; Listokin, D. Transit-oriented development and historic preservation across the United States: A geospatial analysis. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 10, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N. A preliminary study of slow traffic system to activate the vitality of historic districts take Wuhan Tanhualin historic district as an example. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Chongqin, China, 20–22 November 2020; p. 012206. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Chen, D.; Qin, X.; Wang, S. Comprehensive assessment to residents’ perceptions to historic urban center in megacity: A case study of Yuexiu District, Guangzhou, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2021, 20, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, Y.H. Research on the evaluation model of non-motorized tavel environment in historical districts considering riding speed. Civ. Eng. J. Staveb. Obz. 2024, 33, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, T.; Iseki, H. Transportation Impacts on Cityscape Preservation: Spatial Distribution and Attributes of Surface Parking Lots in the Historic Central Districts. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.H.; Zhao, J.T.; Li, M.Z. A Study on the Influencing Factors of the Vitality of Street Corner Spaces in Historic Districts: The Case of Shanghai Bund Historic District. Buildings 2024, 14, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Shu, B.; Chang, H.T. Exploring Architectural Shapes Based on Parametric Shape Grammars: A Case Study of the “Three Lanes and Seven Alleys” Historic District in Fuzhou City, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z. Sustainable Development of Historic Districts: From Cultural Resources to Cultural Narrative. In Proceedings of the IEEE Eurasia Conference on Biomedical Engineering, Healthcare and Sustainability (IEEE ECBIOS), Okinawa, Japan, 31 May–3 June 2019; pp. 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Been, V.; Ellen, I.G.; Gedal, M.; Glaeser, E.; McCabe, B.J. Preserving history or restricting development? The heterogeneous effects of historic districts on local housing markets in New York City. J. Urban Econ. 2016, 92, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilderbloom, J.I.; Hanka, M.J.; Ambrosius, J.D. Historic preservation’s impact on job creation, property values, and environmental sustainability. J. Urban. 2009, 2, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, R.; Jonas, K.; Kovacs, J.F. Heritage Conservation Districts Work: Evidence from the Province of Ontario, Canada. Urban Aff. Rev. 2011, 47, 611–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahirovic-Herbert, V.; Gibler, K.M. Historic district influence on house prices and marketing duration. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2014, 48, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzelman, M.D.; Altieri, J.A. Historic preservation: Preserving value? J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2013, 46, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.M.; Coulson, N.E.; Listokin, D. Historic preservation and residential property values: An analysis of Texas cities. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 1973–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winson-Geideman, K.; Jourdan, D.; Gao, S. The Impact of Age on the Value of Historic Homes in a Nationally Recognized Historic District. J. Real Estate Res. 2011, 33, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhao, J.; Xu, J.; Guo, J.; Shi, L. Understanding tourism development of historic districts from a representational perspective. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2016, 14, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Tourism Revitalization of Historic District in Perspective of Tourist Experience: A Case Study of San-Fang Qi-Xiang in Fuzhou City, China. In Global Hospitality and Tourism Management Technologies; de Pablos, P.O., Zhao, J., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.-F.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.-D.; Sun, X.-P.; Zhang, Y.-J. Sustainable Tourism-Oriented Conservation and Improvement of Historical Villages in the Urbanization Process: A Case Study of Nan’anyang Village, Shanxi Province, China. In Urbanization and Locality: Strengthening Identity and Sustainability by Site-Specific Planning and Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Chiou, B.-S. Framing the hierarchy of cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts under the premise of landscape conservation. Land 2021, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, A.; Naoi, T.; Iijima, S. The Effects of Westerners’ Presence on Japanese Evaluations of a Historic District: The Case of Takayama City. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Conversation on saving historical communities: A participatory renewal and preservation platform. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; p. 082053. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-F. Development and Construction of Public Awareness of Community Characteristics Kaohsiung City’s Historic District Industrial Recycling Case. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on the Modern Development of Humanities and Social Science, Hong Kong, China, 1–2 December 2013; pp. 420–422. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, H.R.; van Ommeren, J.N.; Rietveld, P. Historic amenities, income and sorting of households. J. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 16, 203–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, L.A.R.; Appler, D.R. Building a Local Preservation Ethic in the Era of Urban Renewal: How Did Neighborhood Associations Shape Historic Preservation Practice in Lexington, Kentucky? J. Urban Hist. 2020, 46, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. Examining urban design strategies in historic districts: A systematic literature review. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2024, 177, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardowli, M.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Aram, F.; Mosavi, A. Survey of Sustainable Regeneration of Historic and Cultural Cores of Cities. Energies 2020, 13, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Duangputtan, P.; Mishima, N. Adapting the Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Study Slums in a Historical City: The Mae Kha Canal Informal Settlements, Chiang Mai. Buildings 2024, 14, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhzoumi, J.; Al-Harithy, H.; Bazzi, M. Contextualizing UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape Approach: A Framework for Identifying Modern Heritage in Post-Blast Beirut. Land 2024, 13, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Lv, L.; Peng, X.; He, J. Sustainable Urban Regeneration with Wind and Thermal Environment Optimization: Design Roadshow of a Historic Town in China. Coatings 2024, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Albornoz, P.; López, M.I.; Carmona, P.; Rubio-Manzano, C. Digitalization and Spatial Simulation in Urban Management: Land-Use Change Model for Industrial Heritage Conservation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Frequency | Country | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 165 | China | 0.41 |

| 2 | 46 | USA | 0.14 |

| 3 | 37 | England | 0.17 |

| 4 | 31 | Spain | 0.14 |

| 5 | 27 | Italy | 0.03 |

| 6 | 21 | Turkey | 0.00 |

| 7 | 20 | Japan | 0.13 |

| 8 | 15 | Netherlands | 0.06 |

| 9 | 14 | Portugal | 0.08 |

| 10 | 14 | Australia | 0.18 |

| No. | Freq | Centrality | Cited Journal | Quartile Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 159 | 0.05 | Sustainability | Q1 |

| 2 | 157 | 0.16 | Cities | Q1 |

| 3 | 130 | 0.21 | Landscape and Urban Planning | Q1 |

| 4 | 94 | 0.14 | Habitat International | Q1 |

| 5 | 82 | 0.07 | Urban Studies | Q1 |

| 6 | 81 | 0.03 | International Journal of Heritage Studies | Q1 |

| 7 | 75 | 0.02 | Land Use Policy | Q1 |

| 8 | 69 | 0.04 | Journal of Cultural Heritage | Q1 |

| 9 | 69 | 0.03 | Sustainable Cities and Society | Q1 |

| 10 | 61 | 0.03 | Land | Q1 |

| No. | Freq | Centrality | Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 155 | 0.38 | Environmental Studies |

| 2 | 90 | 0.42 | Environmental Sciences |

| 3 | 73 | 0.14 | Green/Sustainable Science/Technology |

| 4 | 72 | 0.24 | Urban Studies |

| 5 | 53 | 0.04 | Construction/Building Technology |

| 6 | 51 | 0.26 | Geography |

| 7 | 51 | 0.03 | Architecture |

| 8 | 43 | 0.01 | Regional/Urban Planning |

| 9 | 43 | 0.02 | Engineering, Civil |

| 10 | 24 | 0.03 | Humanities, Multidisciplinary |

| No. | Freq | Centrality | Keywords | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 62 | 0.32 | historic district | 2008 |

| 2 | 44 | 0.18 | historic urban landscape | 2014 |

| 3 | 27 | 0.14 | cultural heritage | 2008 |

| 4 | 22 | 0.29 | conservation | 2008 |

| 5 | 21 | 0.25 | historic preservation | 2001 |

| 6 | 18 | 0.1 | sustainable development | 2020 |

| 7 | 18 | 0.05 | China | 2015 |

| 8 | 14 | 0.19 | heritage | 2009 |

| 9 | 13 | 0.01 | space syntax | 2018 |

| 10 | 13 | 0.14 | urban conservation | 2003 |

| 11 | 12 | 0.06 | urban renewal | 2013 |

| 12 | 12 | 0.01 | urban morphology | 2021 |

| 13 | 12 | 0.18 | sustainability | 2009 |

| 14 | 12 | 0.24 | geographical information systems | 2001 |

| 15 | 12 | 0.08 | urban regeneration | 2011 |

| 16 | 12 | 0.01 | heritage conservation | 2015 |

| 17 | 11 | 0.01 | historic urban area | 2015 |

| 18 | 11 | 0.01 | historic building | 2014 |

| 19 | 11 | 0.03 | cultural landscape | 2006 |

| 20 | 10 | 0.04 | urban planning | 2022 |

| 21 | 7 | 0.02 | urban heritage | 2020 |

| 22 | 7 | 0.05 | built environment | 2019 |

| 23 | 7 | 0.06 | heritage tourism | 2015 |

| 24 | 7 | 0.02 | historic city | 2012 |

| 25 | 6 | 0.02 | urban development | 2006 |

| NO. | Count | Year | Method | Cited Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 2019 | Desk work | The Historic Urban Landscape approach to urban management: a systematic review [35]. |

| 2 | 7 | 2017 | Territorial paradigm | Cultural Heritage and Urban Tourism: Historic City Centres under Pressure [37]. |

| 3 | 7 | 2019 | Visual measuring | Measuring visual quality of street space and its temporal variation: Methodology and its application in the Hutong area in Beijing [38]. |

| 4 | 7 | 2020 | Morphological investigation | Pingyao: The historic urban landscape and planning for heritage-led urban changes. |

| 5 | 6 | 2019 | Fire Risk Index Method | Assessing Vulnerability and Fire Risk in Old Urban Areas: Application to the Historical Centre of Guimarães [39]. |

| 6 | 6 | 2020 | Desk work | Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices [40]. |

| 7 | 6 | 2019 | Field research and structural equation modeling | Effects of soundscape perception on visiting experience in a renovated historical block [41]. |

| 8 | 6 | 2016 | Desk work | The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban conservation [42]. |

| 9 | 5 | 2021 | Urban sensor data | Revitalizing historic districts: Identifying built environment predictors for street vibrancy based on urban sensor data [43]. |

| 10 | 5 | 2015 | Questionnaire surveys and partial least squares structural equation modeling | A Study on the Sustainable Development of Historic District Landscapes Based on Place Attachment among Tourists: A Case Study of Taiping Old Street, Taiwan [44]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geng, L.; Xue, M.; Li, J.; Ma, J. Historic District Conservation: A Critical Review of Global Trends, Development in the 21st Century, and Challenges Through CiteSpace Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081232

Geng L, Xue M, Li J, Ma J. Historic District Conservation: A Critical Review of Global Trends, Development in the 21st Century, and Challenges Through CiteSpace Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(8):1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081232

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Lin, Minghui Xue, Jia Li, and Jiaoguo Ma. 2025. "Historic District Conservation: A Critical Review of Global Trends, Development in the 21st Century, and Challenges Through CiteSpace Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 8: 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081232

APA StyleGeng, L., Xue, M., Li, J., & Ma, J. (2025). Historic District Conservation: A Critical Review of Global Trends, Development in the 21st Century, and Challenges Through CiteSpace Analysis. Buildings, 15(8), 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081232