Comparative Sensitivity Analysis of Cooling Energy Factors in West- and South-Facing Offices in Chinese Cold Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

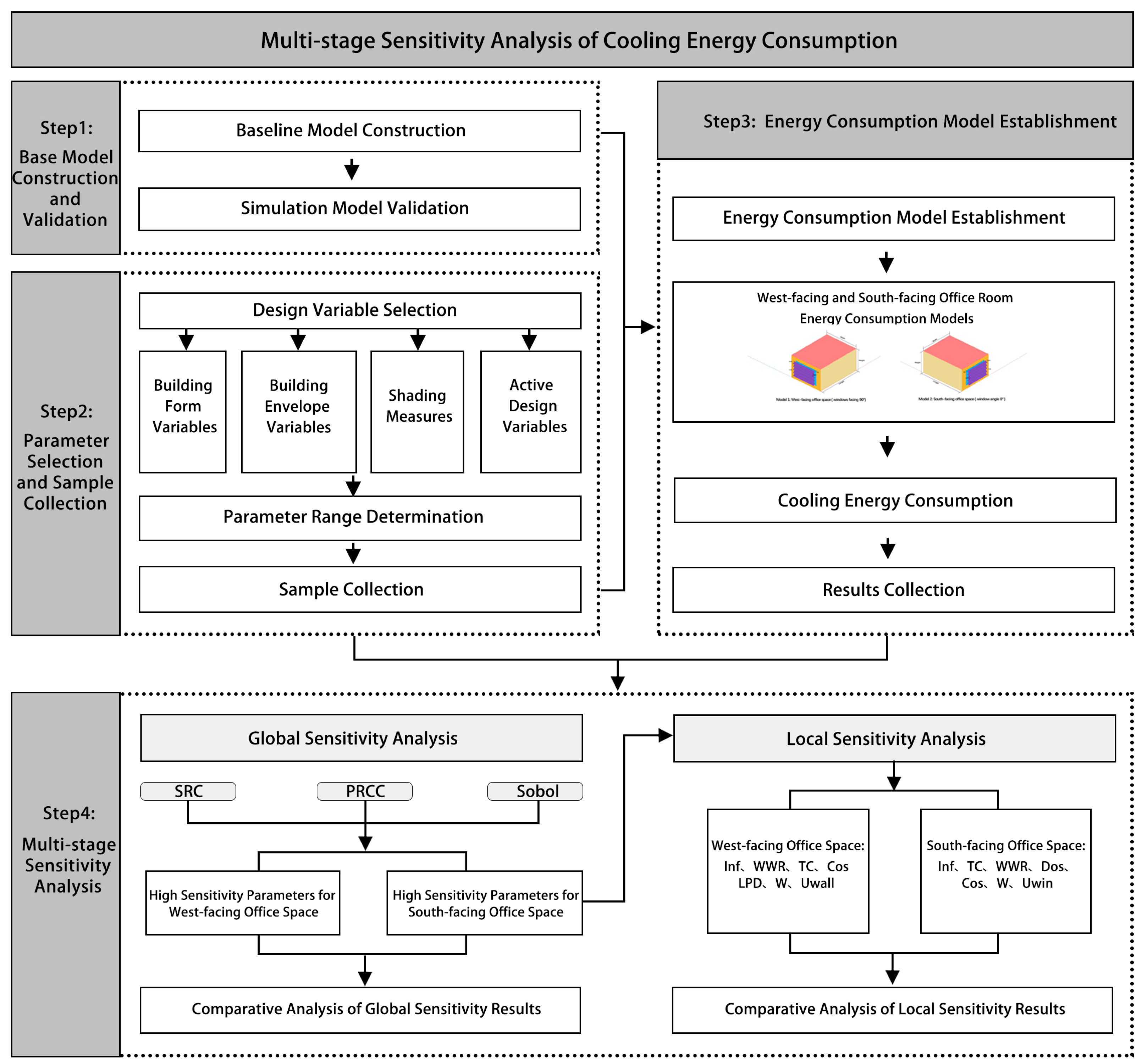

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Research Framework

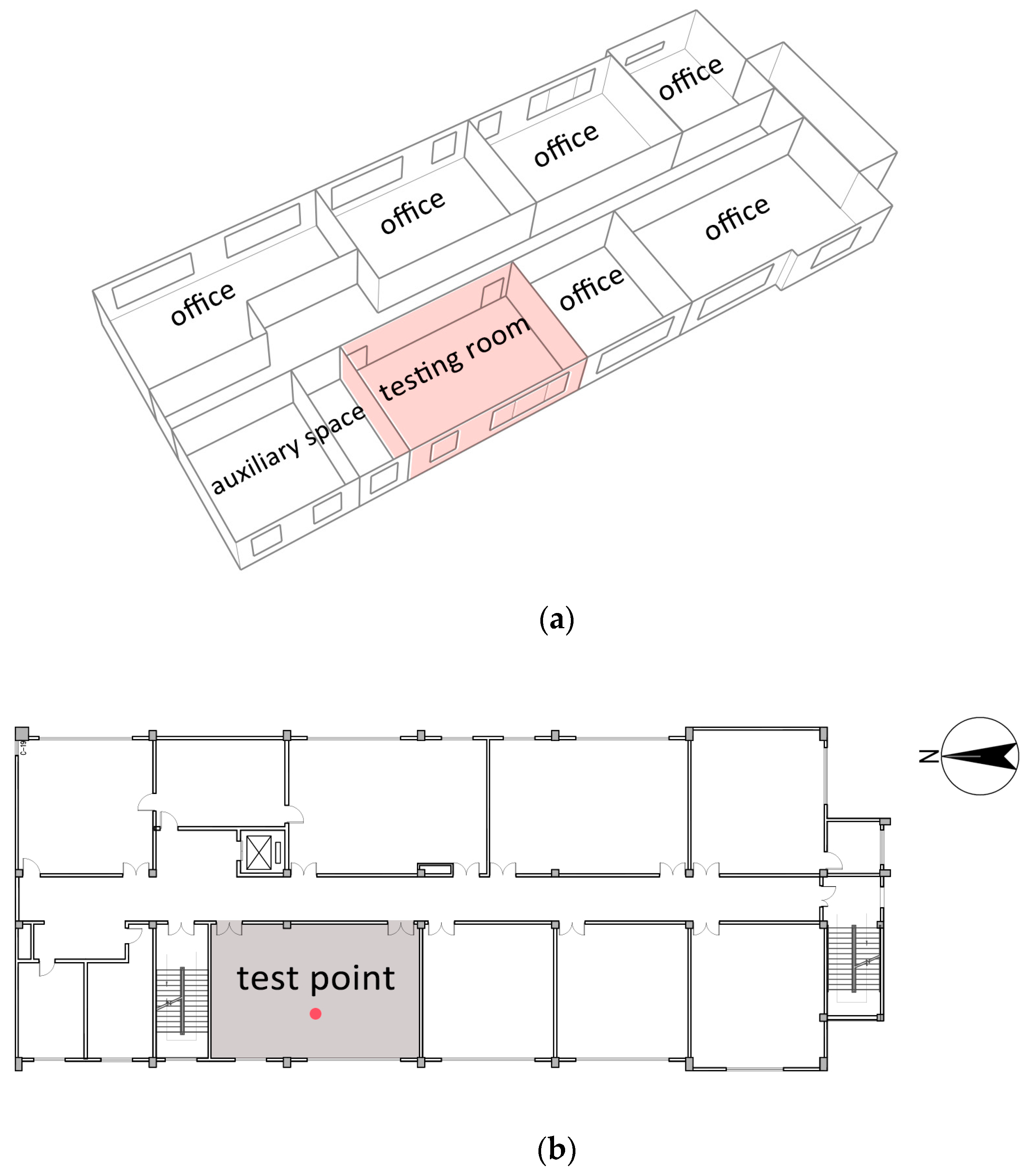

2.2. Baseline Model Construction and Validation

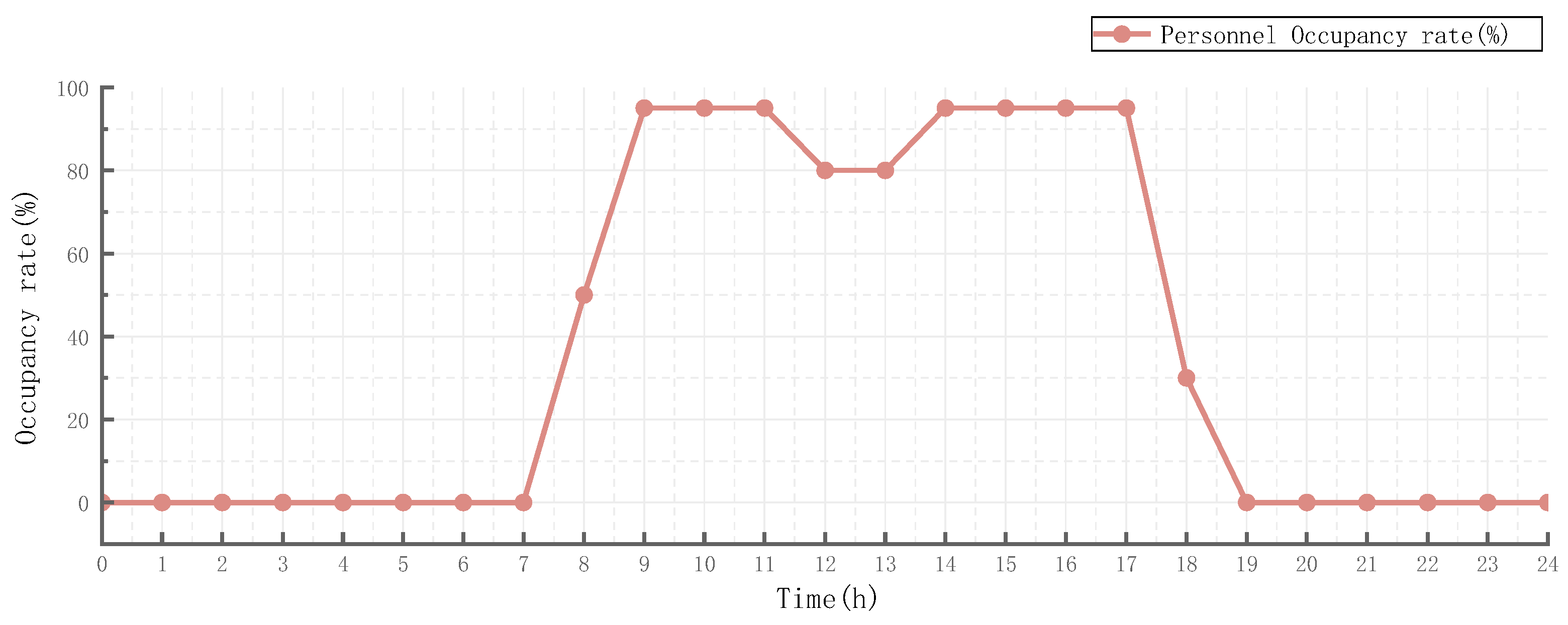

2.3. Parameter Selection and Sample Collection

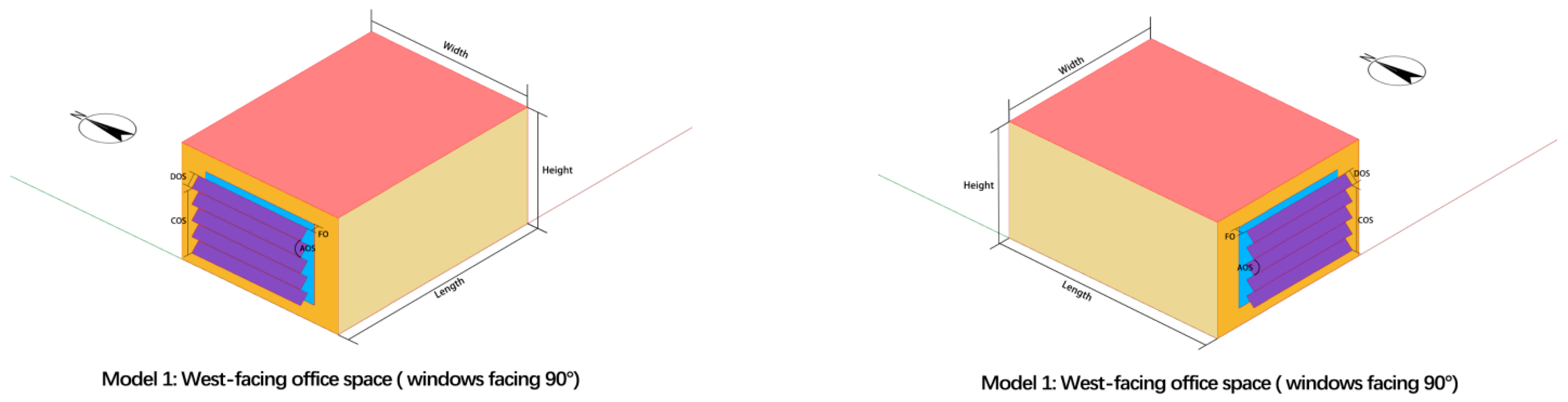

2.4. Energy Consumption Model Establishment

2.5. Multi-Stage Sensitivity Analysis Method

2.5.1. Global Sensitivity Analysis

- (1)

- Standardized Regression Coefficient and Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient

- (2)

- Sobol Sensitivity Analysis Method

2.5.2. Local Sensitivity Analysis (LSA)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. GSA Results and Discussion

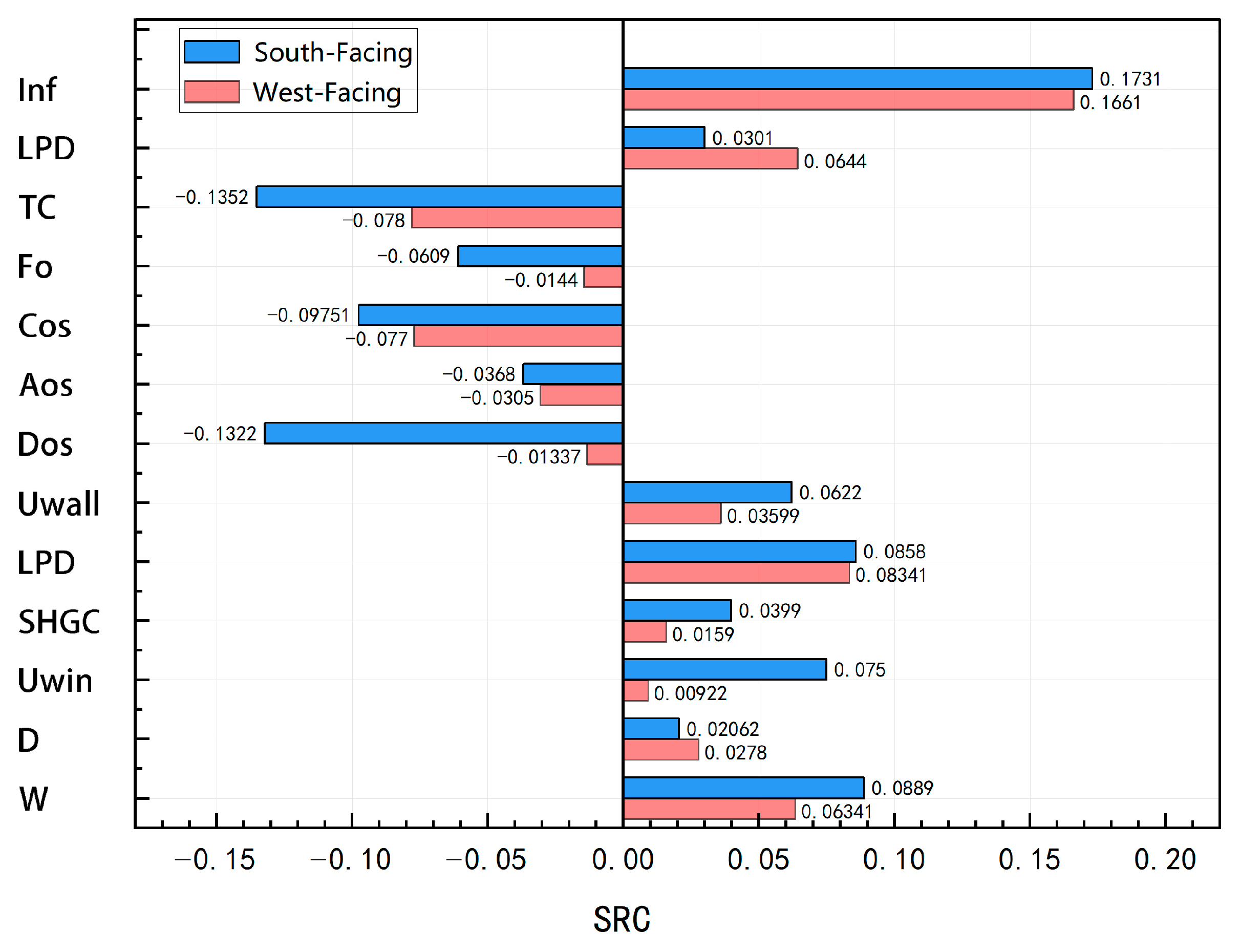

3.1.1. SRC, PRCC, and Sobol Sensitivity Analysis Results for West-Facing Buildings

3.1.2. SRC, PRCC, and Sobol Sensitivity Analysis Results for South-Facing Buildings

3.1.3. Comparative Analysis of the GSA Results for West- and South-Facing Office Spaces

3.2. LSA Results and Discussion

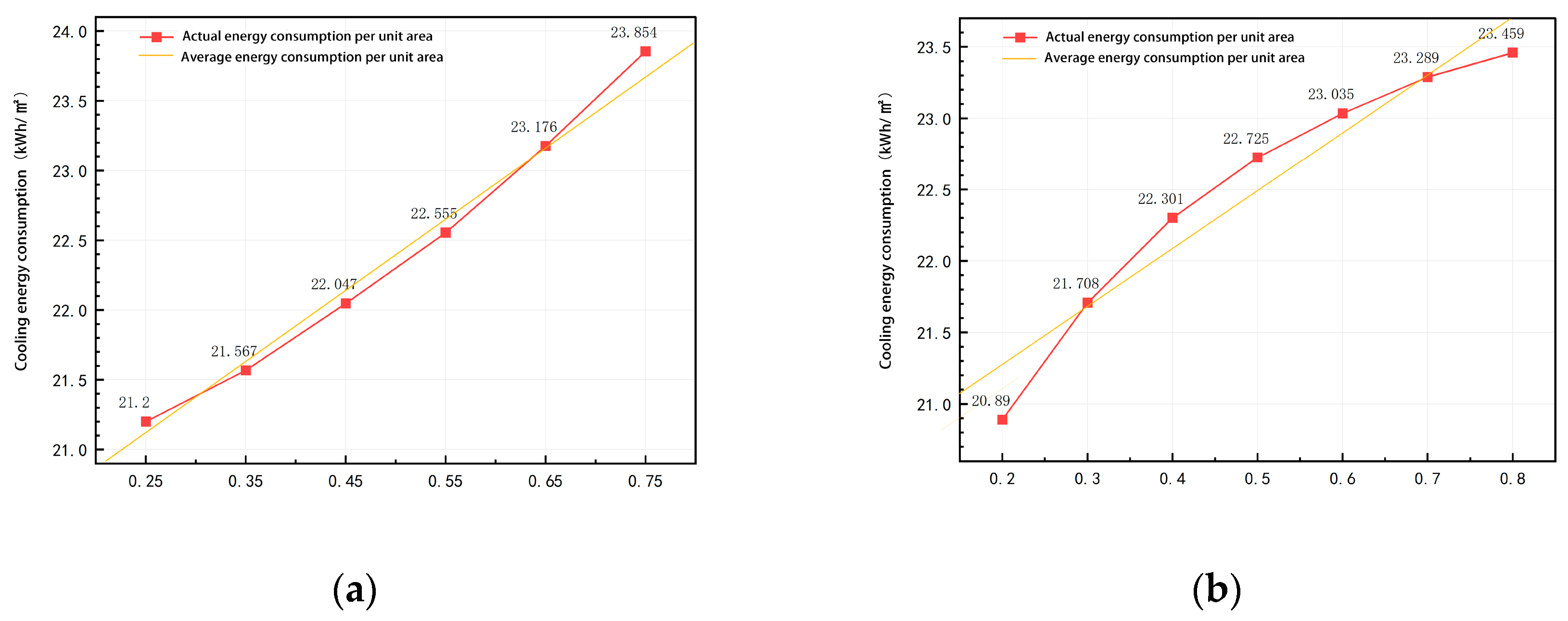

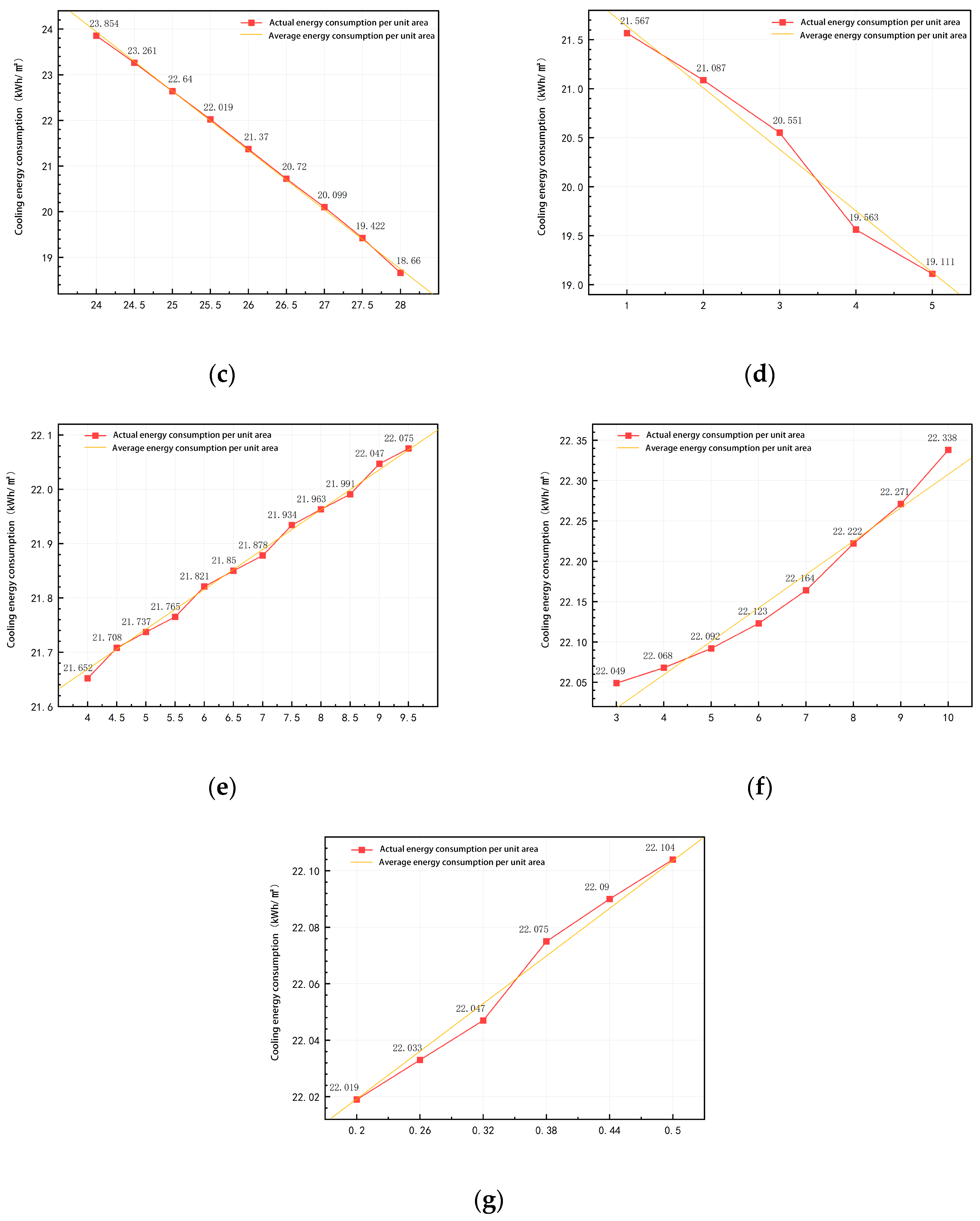

3.2.1. LSA of High-Sensitivity Parameters for West-Facing Office Spaces

3.2.2. LSA of High-Sensitivity Parameters for South-Facing Office Spaces

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis of the Results Under West- and South-Facing Conditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, X.; Dai, X.; Liu, J. Building energy-consumption status worldwide and the state-of-the-art technologies for zero-energy buildings during the past decade. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberts, R.; Hensen, J.L. Building Performance Simulation for Design and Operation; Spoon Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.X. Performance Optimization Design for Office Buildings in Cold Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F.; Chu, H.L.; Zhang, J.G.; Fu, L.X.; Zheng, R.J. The Influence of Window Systems on Energy Consumption of Public Buildings using Orthogonal Experiment Method. Bull. Sci. Technol. 2009, 25, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.Y. Research on Multi-Objective Optimization Design of Xi’an University Student Activity Center Based on Energy Consumption and Thermal Comfort. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; Hou, S.; Liu, C.; Jones, P. Effect of geometric factors on the energy performance of high-rise office towers in Tianjin, China. Build. Simul. 2017, 10, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuanyuan, P.S.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yao, J.; Zheng, R.Y. Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization of Energy-Saving Measures for Office Building in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Regions. Energies 2024, 17, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.B. Sensitivity Analysis of Energy Performance for Office Building in Severe Cold Climate. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Zhu, X.Z.; Yan, Z.X.; Cao, M.Y. Evaluation of energy retrofits for existing office buildings through uncertainty and sensitivity Analyses: A case study of Tianjin, China. Energy Build. 2025, 325, 115363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Tsay, Y.S. An Integrated Sensitivity Analysis Method for Energy and Comfort Performance of an Office Building along the Chinese Coastline. Buildings 2021, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, A.; Mandev, E.; Ersan, O.; Muratçobanoğlu, B.; Ceviz, M.A.; Kara, Y.A. Thermal performance evaluation of PCM-integrated interior shading devices in building glass facades. J. Energy Storage 2025, 113, 115614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.R.; Xu, L.J. Analysis of the Distribution and Evolution Characteristics of Office Space in Zhengzhou Central Urban Area. J. Cap. Norm. Univ. 2017, 38, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.K.; Kumar, N.; Lamba, R.; Mehta, K. Multi-objective optimization of glazing and shading configurations for visual, thermal, and energy performance of cooling dominant climatic regions of India. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 4909–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgarm, N.; Sajadi, B.; Azarbad, K.; Delgarm, S. Sensitivity analysis of building energy performance: A simulation-based approach using OFAT and variance-based sensitivity analysis methods. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 15, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W. A Review of Sensitivity Analysis Methods in Building Energy Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 20, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsath, T.L.; Bandhosseini, K.A. Sensitivity Analysis Evaluating Building Geometry’s Effect on Energy use. Renew. Energy 2015, 76, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.H.; Petersen, S. Choosing the appropriate sensitivity analysis method for building energy model-based investigations. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, A.; Jonsson, C.J.; Appelfeld, D.; Ward, G.; Lee, E.S. A Validation of a Ray-Tracing Tool Used to Generate Bi-Directional Scattering Distribution Functions for Complex Fenestration Systems. Sol. Energy 2013, 98, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, S.; Cheung, H. Sensitivity analysis of design parameters and optimal design for zero/low energy buildings in subtropical regions. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, R.; Gosselin, L.; Decker, S. Sensitivity analysis of energy performance and thermal comfort throughout building design process. Energy Build. 2018, 164, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.M. Research and Application of Operation Monitoring and Optimization for Near-Zero Energy Office Buildings in Zhengzhou. Master’s Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, B.X. Parametric design of photovoltaic louver integrated shading devices for west facade windows of office buildings in central China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ/T 177-2009; Standard for Energy Efficiency Test of Public Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Pan, Y.Q.; Zhu, M.Y.; Lv, Y.; Yang, Y.K.; Liang, Y.M.; Yin, R.X.; Yang, Y.T.; Jia, X.Y.; Wang, X.; Zeng, F.; et al. Building energy simulation and its application for building performance optimization: A review of methods, tools, and case studies. Adv. Appl. Energy 2023, 10, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernetti, R.; Prada, A.; Baggio, P. On the influence of several parameters in energy model calibration: The case of a historical building. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Building Simulation Applications, Bolzano-Bozen, Italy, 30 January–1 February 2013; pp. 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE 14-2014; Measurement of Energy, Demand and Water Savings. ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Yu, C.; Pan, W.; Bai, Y.F. Sensitivities of energy use reduction in subtropical high-rise office buildings: A Hong Kong case. Energy Build. 2024, 311, 114117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T. Multi-Objective Optimization-Based Study on the Design of Near-Zero Energy Consumption Office Buildings in Shandong Province. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bagholizadeh, M.; Rostamzadeh-Renani, M.; Rostamzadeh-Renani, R.; Toghraie, D. Multi-objective optimization of Venetian blinds in office buildings to reduce electricity consumption and improve visual and thermal comfort by NSGA-II. Energy Build. 2022, 265, 112639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qi, Z.X.; Ran, S.L.; Ma, Q.S. A Study on the Effect of Dynamic Photovoltaic Shading Devices on Energy Consumption and Daylighting of an Office Building. Buildings 2024, 14, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimazari, M.; Baghoolizadeh, M.; Sajadi, S.M.; Kheiri, P.; Moghaddam, M.Y.; Rostamzadeh-Renani, M.; Rostamzadeh-Renani, R.; Hamooleh, M.B. Multi-objective optimization of daylight illuminance indicators and energy usage intensity for office space in Tehran by genetic algorithm. Energy Rep. 2024, 10, 3324–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ/T 67-2019; Standard for Design of Office Building. China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2019.

- DBJ41/T 075-2016; Henan Province Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings. Zhengzhou University Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2016.

- GB/T 51350-2019; Technical Standard for Nearly Zero Energy Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- GB 55015-2021; General Code for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Application in Buildings. China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB 50736-2012; Design Code for Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB/T 50034-2024; Standard for Lighting Design of Buildings. China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Levy, S.; Steinberg, D.M. Computer experiments: A review. AStA Adv. Stat. Anal. 2010, 94, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.J.; Liu, F.; Li, H.L.; Zhang, X.M.; Wang, K.; Tian, C.S. Passive solar sunspace in a Tibetan buddhist house in Gannan cold areas: Sensitivity analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50189-2015; Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Pudleiner, D.; Colton, J. Using sensitivity analysis to improve the efficiency of a Net-Zero Energy vaccine warehouse design. Build. Environ. 2015, 87, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurbayeva, A.; Memon, S.A.; Kim, J. Sensitivity analysis and optimization of PCM integrated buildings in a tropical savanna climate. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 64, 105603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, I.M. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Math. Comput. Simul. 2001, 55, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.S.; Ghisi, E. Estimating the sensitivity of design variables in the thermal and energy performance of buildings through a systematic procedure. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Material | Thickness (mm) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m2 K) | Specific Heat (J/kg K) | Thermal Resistance (m2·K)/W | Heat Transfer Coefficient (W/m2 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exterior Wall | Cement mortar | 3 | 0.930 | 1050.0 | 0.003 | 0.486 |

| Aerated concrete block | 200 | 0.220 | 1158.0 | 0.909 | ||

| Polystyrene board | 62 | 0.063 | 1100.0 | 0.984 | ||

| Cement mortar | 8 | 0.930 | 1050.0 | 0.008 | ||

| Brick | 10 | 1.740 | 2916.0 | 0.006 | ||

| Interior Wall | Cement mortar | 5 | 0.930 | 1074.4 | 0.006 | 0.868 |

| Mixed mortar | 15 | 0.930 | 1050.0 | 0.017 | ||

| Aerated concrete block | 200 | 0.220 | 1158.0 | 0.909 | ||

| Roof | Cement mortar | 25 | 0.930 | 1050.0 | 0.027 | 0.124 |

| C20 fine stone concrete | 40 | 1.510 | 920.0 | 0.026 | ||

| Extruded polystyrene foam plastic board | 230 | 0.030 | 1380.0 | 7.667 | ||

| Waterproof layer | 4 | 0.170 | 1470.0 | 0.024 | ||

| Cement mortar | 20 | 0.930 | 1050.0 | 0.022 | ||

| Lightweight aggregate concrete | 30 | 0.300 | 1091.0 | 0.067 | ||

| Reinforced concrete | 120 | 1.740 | 920.0 | 0.069 | ||

| Floor | Brick | 10 | 1.740 | 920.0 | 0.006 | 4.462 |

| Cement mortar | 20 | 0.930 | 1050.0 | 0.022 | ||

| Reinforced concrete | 80 | 1.740 | 920.0 | 0.046 | ||

| Window | 6 + 12 + 6 double-glazed hollow glass with a steel frame | 24 | - | - | - | 2.800 |

| Statistical Indicator | Calculated Results | Standards |

|---|---|---|

| 2–3 August | ASHRAE Standards | |

| NMBE | 5.1% | <10% |

| CVRMSE | 6.4% | <30% |

| Category | Parameter | Symbol | Parameter Variation Range | Data Type | Unit | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building Form | Building width | W | 3–10 | Continuous | m | JGJ/T 67-2019 [32] |

| Building depth | D | 5–10 | Continuous | m | [21] | |

| Envelope Structure | Window heat transfer coefficient | Uwin | 1.3–3 | Continuous | (W/m2 K) | |

| Window solar heat gain coefficient | SHGC | 0.30–0.9 | Continuous | - | DBJ41/T 075-2016 [33] | |

| Window-to-wall ratio | WWS | 0.20–0.8 | Continuous | - | GB/T 51350-2019 [34] | |

| Exterior wall heat transfer coefficient | Uwall | 0.2–0.5 | Continuous | (W/m2 K) | GB 55015-2021 [35] | |

| Shading Elements | Shading board width | Dos | 0.1–0.5 | Continuous | m | JGJ/T 67-2019 [21,29,30,32] |

| Shading board inclination angle | Aos | 0, 15, 30, 45 | Discrete | ° | ||

| Number of shading boards | Cos | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Discrete | - | ||

| Distance from the shading board to the window | Fo | 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 | Discrete | m | ||

| Active Design | Cooling setpoint temperature | TC | 24–28 | Continuous | °C | GB 50736-2012 [36] |

| Lighting power density | LPD | 4–9.5 | Continuous | W/m2 | GB 55015-2021 | |

| Infiltration rate | Inf | 0.25–0.75 | Continuous | ac/h | GB/T 50034-2024 [37] |

| Parameter | Regression | Sobol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRC | PRCC | Total Order | |

| Building width (W) | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Building depth (D) | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Window heat transfer coefficient (Uwin) | 13 | 9 | 13 |

| Window solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Window-to-wall ratio (WWS) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Exterior wall heat transfer coefficient (Uwall) | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Shading board width (Dos) | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Shading board inclination angle (Aos) | 8 | 13 | 8 |

| Number of shading boards (Cos) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Distance from shading board to window (Fo) | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Cooling setpoint temperature (TC) | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Lighting power density (LPD) | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Infiltration rate (Inf) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Parameter | Regression | Sobol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRC | PRCC | Total Order | |

| Building width (W) | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Building depth (D) | 13 | 11 | 13 |

| Window heat transfer coefficient (Uwin) | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| Window solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Window-to-wall ratio (WWS) | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Exterior wall heat transfer coefficient (Uwall) | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Shading board width (Dos) | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Shading board inclination angle (Aos) | 11 | 13 | 11 |

| Number of shading boards (Cos) | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Distance from shading board to window (Fo) | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| Cooling setpoint temperature (TC) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lighting power density (LPD) | 12 | 9 | 12 |

| Infiltration rate (Inf) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sort | West-Facing Office Space | South-Facing Office Space | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Sensitivity Parameters | 1 | Infiltration rate (Inf) | Infiltration rate (Inf) |

| 2 | Window-to-wall ratio (WWS) | Cooling setpoint temperature (TC) | |

| 3 | Cooling setpoint temperature (TC) | Shading board width (Dos) | |

| 4 | Number of shading boards (Cos) | Number of shading boards (Cos) | |

| 5 | Lighting power density (LPD) | Building width (W) | |

| 6 | Building width (W) | Window-to-wall ratio (WWS) | |

| 7 | Exterior wall heat transfer coefficient (Uwall) | Window heat transfer coefficient (Uwin) | |

| 8 | Shading board inclination angle (Aos) | Exterior wall heat transfer coefficient (Uwall) | |

| 9 | Building depth (D) | Distance from shading board to window (Fo) | |

| 10 | Window solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) | Window solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) | |

| 11 | Distance from shading board to window (Fo) | Shading board inclination angle (Aos) | |

| 12 | Shading board width (Dos) | Lighting power density (LPD) | |

| 13 | Window heat transfer coefficient (Uwin) | Building depth (D) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Sun, B. Comparative Sensitivity Analysis of Cooling Energy Factors in West- and South-Facing Offices in Chinese Cold Regions. Buildings 2025, 15, 4545. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244545

Zhang H, Wang X, Li K, Sun B. Comparative Sensitivity Analysis of Cooling Energy Factors in West- and South-Facing Offices in Chinese Cold Regions. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4545. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244545

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hua, Xueyi Wang, Kunming Li, and Boxin Sun. 2025. "Comparative Sensitivity Analysis of Cooling Energy Factors in West- and South-Facing Offices in Chinese Cold Regions" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4545. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244545

APA StyleZhang, H., Wang, X., Li, K., & Sun, B. (2025). Comparative Sensitivity Analysis of Cooling Energy Factors in West- and South-Facing Offices in Chinese Cold Regions. Buildings, 15(24), 4545. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244545