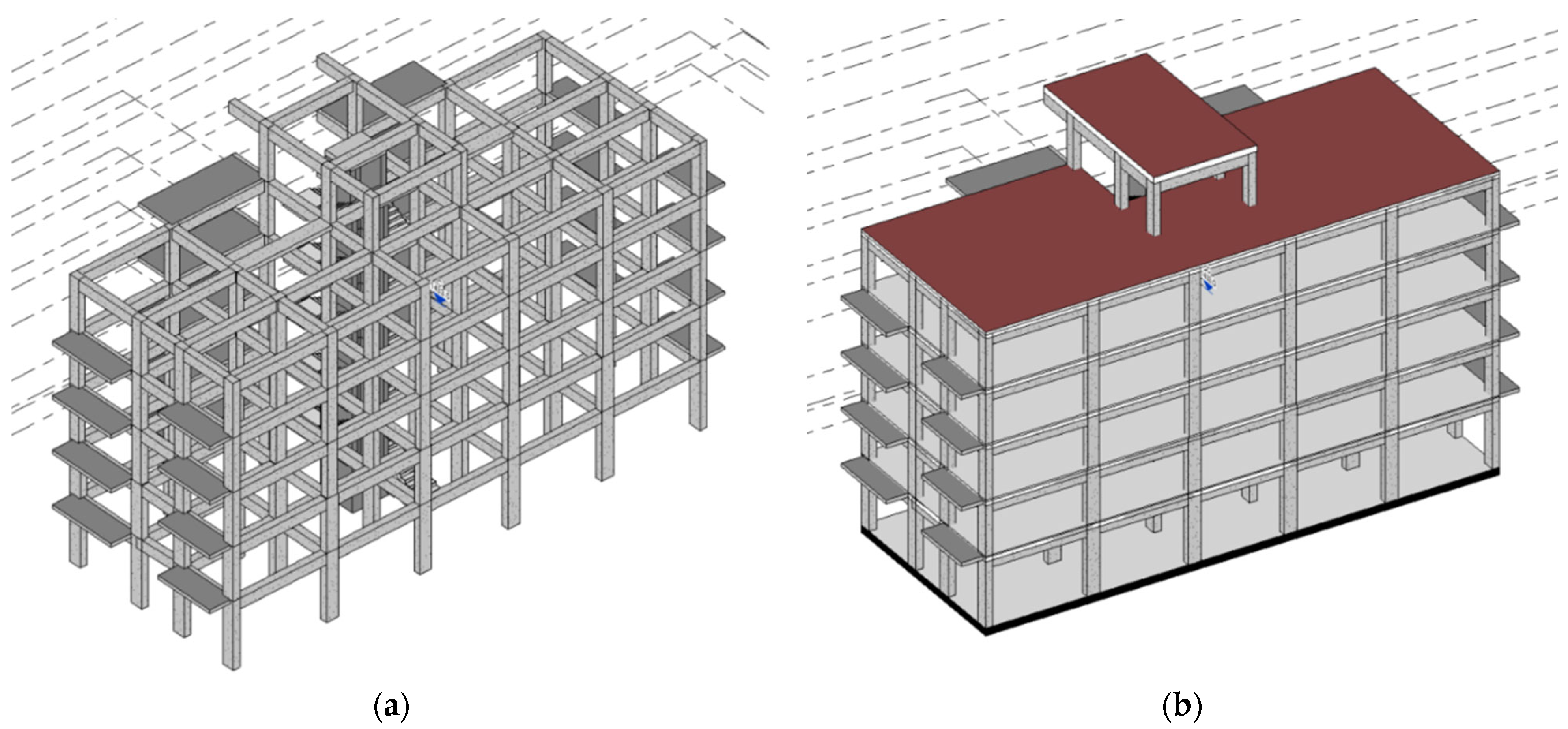

The architectural–structural design workflow of the building was characterized by a cyclic process, starting with the construction of a preliminary architectural model. In this model, grids were set up and infill walls and partitions were inserted, following the architectural concept guidelines. Subsequently, the architectural file was imported as a link into the structural file in Revit®, providing the initial references necessary for the construction of the structural model. For the structural Modeling, it was necessary to generate the insertion levels. Starting from the plan and elevation references, the first operation for constructing the structural model in Revit was the creation of column families and their insertion in a plan view. In the parameterization of the reinforced concrete column families, only the information strictly necessary for the analyses was included, namely the material (CLS C25/30) and the approximate dimensions obtained through preliminary sizing.

5.1.1. Information Transfer with Native Files

Starting from the same structural objects inserted in the model (

Figure 3a), Revit

® v.2021 software allows the automatic generation of the analytical model corresponding to the various modeled structural elements (

Figure 3b). This functionality enables the insertion of constraints, loads, and load combinations, as well as the verification of the congruence of the generated model. However, the analytical model automatically generated by Revit

® presents some significant limitations. It is important to note that the analytical instabilities and misinterpretations observed during the BIM-to-FEM transfer are partly attributable to the LOD/LOI adopted in the structural model. The use of LOD C elements, appropriate for design coordination, does not always provide sufficient analytical-specific attributes to support a fully automated conversion to FEM entities, particularly for elements requiring advanced connectivity rules or parametric discretization.

One of the main limitations encountered is the absence of information regarding cast-in-place hollow core slabs and stairs, despite these elements being present in the structural model. As suggested by Gomes et al. [

17], to include stairs in the analysis model, inclined solid concrete slabs could be inserted. This solution, however, would require subsequent manual insertion of the correct reinforcement, increasing the complexity and time required for modeling.

These limitations highlight the need to develop advanced methodologies and modeling tools that can overcome such deficiencies, ensuring a more accurate and complete representation of structural elements. The integration of detailed information on cast-in-place hollow core slabs and stairs in the analytical model is crucial to improve the precision of structural analyses and the consistency of information transferred between different design and calculation software.

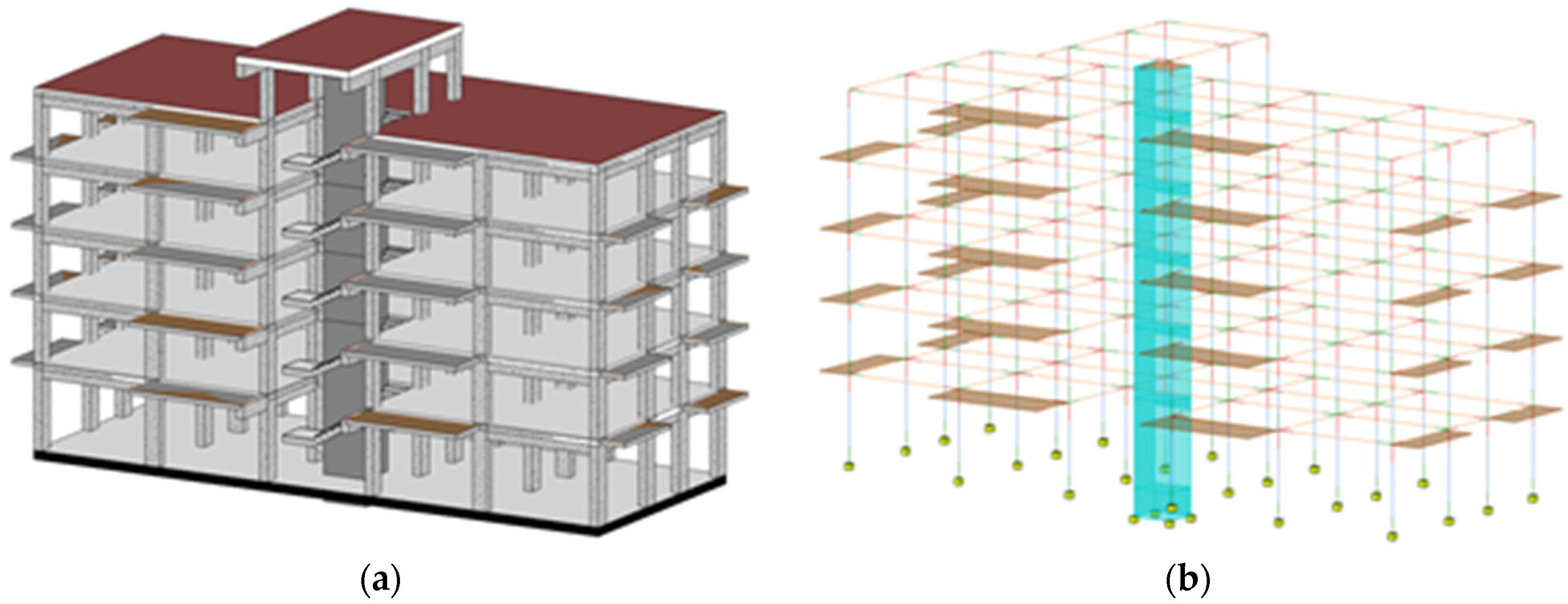

For the first test of information transfer from the structural model to the calculation model, a direct link using native files was employed, utilizing Revit

® v.2021 and Robot Structural Analysis

® software, both developed by Autodesk

® (

Figure 4).

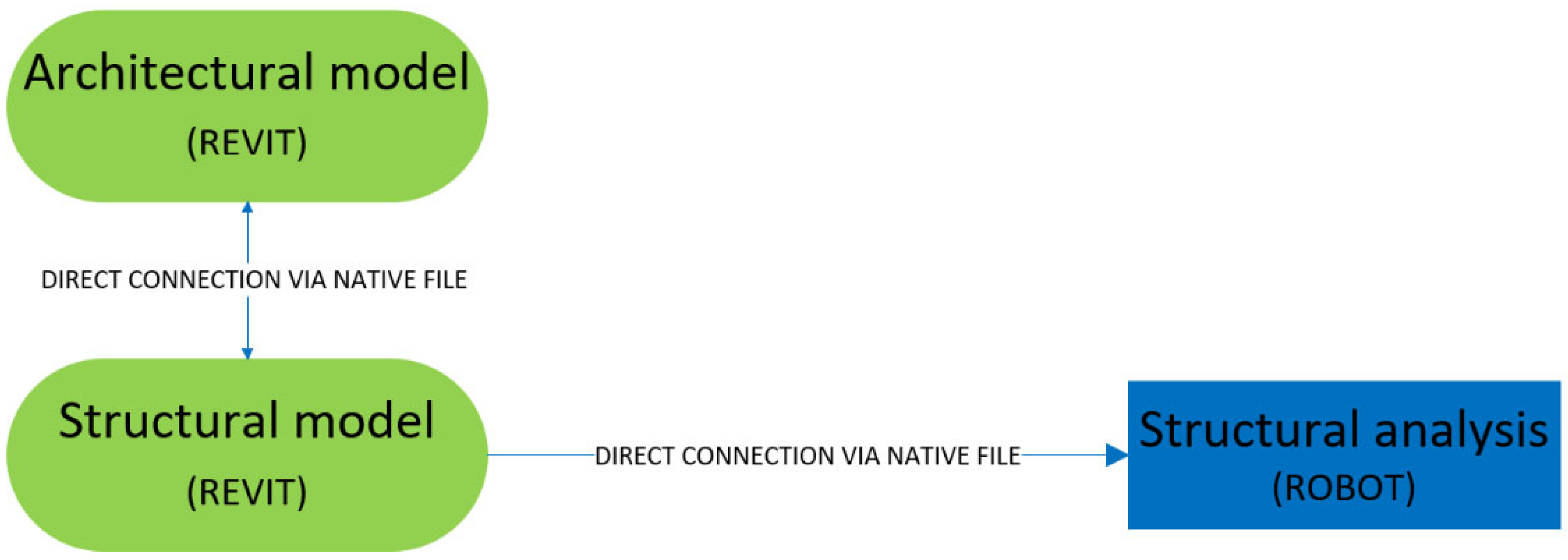

During the information transfer between Revit

® and Robot

® software, inconsistencies regarding the non-orthogonality of the analytical model axes were detected (

Figure 5), confirming the findings of Gomes et al. [

17]. This interpretation issue is due to Revit

® automatically recognizing the central points of structural elements as nodes in the calculation model. Such inconsistencies, occurring in complex design situations typical of BIM applications, can lead to the generation of erroneous analytical models which, if directly imported into the analysis software, can cause severe errors in the design of structural components. Among the main benefits of native Revit-Robot file exchange (2022 versions), the bidirectional transfer of information stands out, enabling efficient modifications without duplication. However, some limitations remain, such as the inability to transfer the reinforcement of slabs and certain foundations from Robot

® to Revit

® [

4].

In the 2021 version of Revit®, some commands are available to make corrections to the analytical model before its transfer to the analysis software. However, the workflow of automatic generation and correction of the model, when working with complex models, might lead the designer to lose control of the analytical model. Additionally, any modification of the structural model elements requires further operations to modify or check the entire analytical model.

With the 2024 version of Revit

®, several modifications have been made to the software to address these issues. The analytical model is no longer automatically generated with the insertion of the structural element; instead, a specific automation command has been introduced. This command allows the generation of an analytical model from the structural model and vice versa, enabling the insertion of interpretation inputs for information conversion. However, the tests of information transfer with this new functionality did not achieve satisfactory results (

Figure 6a). The analytical model created with this procedure presented numerous node disconnections (

Figure 6b,c), also detected in the information transfer to Robot

®.

The issues related to the automatic conversion of data between the structural model and the structural analysis model are still present. The software developers have taken this aspect into consideration, introducing a command in the 2024 version of Revit

® that allows the manual creation of the analytical model. This manual generation method offers many advantages, as the insertion always starts from the references of the individual structural elements, leaving the interpretation of the analytical model entirely to the designer. Despite the advantages offered by this type of information transfer, thorough validation of the structural analysis model by users remains essential, along with the partial remodeling of missing or incorrectly interpreted elements. A quantitative assessment was carried out based on the percentage of structural elements correctly imported after each transfer workflow (

Table 2). The metric was defined as the ratio between correctly interpreted objects and the total number of modeled objects for each category (columns and beams), as well as for the geometric characteristics of the model (alignments and nodes). The results show that information related to columns and beams is transferred with complete reliability in both versions, whereas the geometric attributes associated with alignments exhibit noticeable precision losses. The 30% reduction in alignment accuracy observed in the Revit–Robot v.2021 workflow is attributable to nodes where beams with different cross-sectional dimensions intersect. Despite resolving these alignment issues, node connectivity emerges as the most critical parameter in the Revit–Robot v.2024 transfers. Even after testing multiple settings for the semi-automated generation of the analytical model, the new analytical model generation logic introduces significant instability, with correct import rates for this feature not exceeding 20%.

5.1.2. Information Transfer with IFC Files

For an additional test of information transfer from the structural model to the calculation model, an indirect link using IFC format was employed, utilizing Revit

® v.2021 and the calculation software PRO_SAP

® v.22.5.2 (

Figure 7). The first step of this process involved exporting the structural model from Revit in IFC format, using the preset configuration IFC2x3 Coordination View 2.0. The structural model was exported in IFC format in two variants: one with slabs (

Figure 8a) and one without slabs (

Figure 8c).

The IFC files exported from Revit

® were subsequently imported into the FEM calculation software PRO_SAP

®. During the import phase, the software identifies the elements of the IFC file and offers options for importing these elements into the calculation software. However, the elements imported into PRO_SAP

® presented node disconnections and slabs detached from other elements of the structural frame (

Figure 8b,d). To resolve these inconsistencies, the software provides semi-automatic commands that allow individual correction of various issues present in the calculation model imported as IFC. The correction of connections between structural elements can be performed in semi-automatic mode, by setting an influence radius within which the software should restore the connection, or in automatic mode. Despite the availability of these tools, satisfactory results in the analytical model were not achieved, as persistent disconnections in nodes and slabs were detected. Additionally, the issue of non-transfer of some structural elements was encountered (

Figure 8e). The incorrect importation of some elements into PRO_SAP

® was also verified in the “Log file” generated during the import, where problems related to the importation of elements are indicated. Furthermore, with this type of transfer, it was not possible to export information on constraints, loads, and stairs.

This import test highlights that the transfer of information from the structural model to the structural analysis model requires manual adjustments or reconstruction of the model to ensure the accuracy and reliability of structural analyses. Similar results were obtained when using the IFC4 Reference View (structural subset), which did not resolve the disconnections nor improve the completeness of the imported model.

The tests conducted, both with native file transfer and via open IFC format, highlight that the transfer of information from the structural model to the structural analysis model does not occur smoothly and is subject to various issues. Similarly to what was observed for the native Revit–Robot file transfer, a quantitative analysis based on the percentage of correctly imported structural elements was also conducted for the IFC-based transfer from Revit to PRO_SAP (

Table 3). The results show that the geometric information of the model, specifically alignments and nodes, is transferred with complete reliability, whereas information related to columns and beams exhibits noticeable losses. The 65% accuracy obtained for columns is primarily attributable to the non-transfer of some elements and to incomplete information in others. The 80% value reported for beams, on the other hand, is solely due to missing information, such as material properties, despite all elements being geometrically present in the imported model.

The use of automation tools requires conscious modeling, which includes the application of a series of manual adjustments by the designer on the generated model. Manual adjustments may involve the modeling or reconstruction of missing structural members, the realignment of non-orthogonal elements, the reconnection of misaligned or fully disconnected nodes, as well as the insertion or correction of boundary conditions, the reassignment of material properties, and the application of loads that were not transferred or were incorrectly interpreted by the analysis software. These operations are often essential to restore geometric–structural consistency and ensure a reliable analytical model. After each information transfer, it is essential to perform a careful analysis of the errors and warnings generated, intervening where possible to resolve them. Additionally, a systematic check of the information transferred to the calculation software is necessary, considering parameters such as geometry, constraints, loads, and other relevant structural aspects. Even with this type of information transfer, a thorough validation of the structural analysis model by users is necessary, along with the possible re-modeling of missing or incorrectly interpreted elements.

5.1.3. Information Transfer with DXF Files and Partial Model Reconstruction

An additional verification of data transmission was conducted by developing the reverse flow of information through an indirect link based on the Industry IFC format. Specifically, the transfer was analyzed starting from the calculation software towards BIM Authoring tools.

A possible alternative to reorganizing the model after transfer involves the independent development of the structural calculation model, leveraging the capabilities of the IFC format for exporting executive information related to the structure into the architectural and federated model. Given the importance of structural calculation in the design process, a more rigorous control of input and output data of the model could compensate for the increased burden of constructing an additional calculation model. For structural modeling and analysis, the finite element software Jasp®, version 7.5, was used, which can generate output files in IFC format containing information on the structure and reinforcements. Jasp® is a commercial software for structural design, allowing verification and design at ultimate and service limit states for reinforced concrete, steel, and wood structures, in accordance with Italian NTC-2018 standards and Eurocodes.

However, Jasp® currently supports data import only through DXF files and does not allow IFC loading. Consequently, the transferred information is limited to geometric references, while semantic and structural data are lost, requiring additional manual reconstruction of the analytical model. Despite this limitation, it can currently be considered acceptable. In fact, even in structural analysis software that supports IFC data import, difficulties have been encountered in the correct exchange of architectural–structural information, still necessitating the reconstruction of the structural model from scratch for analysis. This approach is applicable to most of the commercially available software currently in use. Although the reconstruction of the analysis model may be required, it enables the generation of a comprehensive BIM model of the structure, ensuring that structural designers retain full control throughout the entire process.

The export of the structural model in IFC format allowed further tests of data interpretation and the development of a federated model of the building, including information on structural reinforcements.

Figure 9 illustrates the conceptual workflow of data transfers between the software used in the analysis. This type of workflow is compatible with most structural analysis software currently available on the market. Thanks to its flexibility, it can easily adapt to different platforms, optimizing calculation and simulation processes. In this way, it is possible to achieve precise results and efficiently manage data, improving the overall effectiveness of the project.

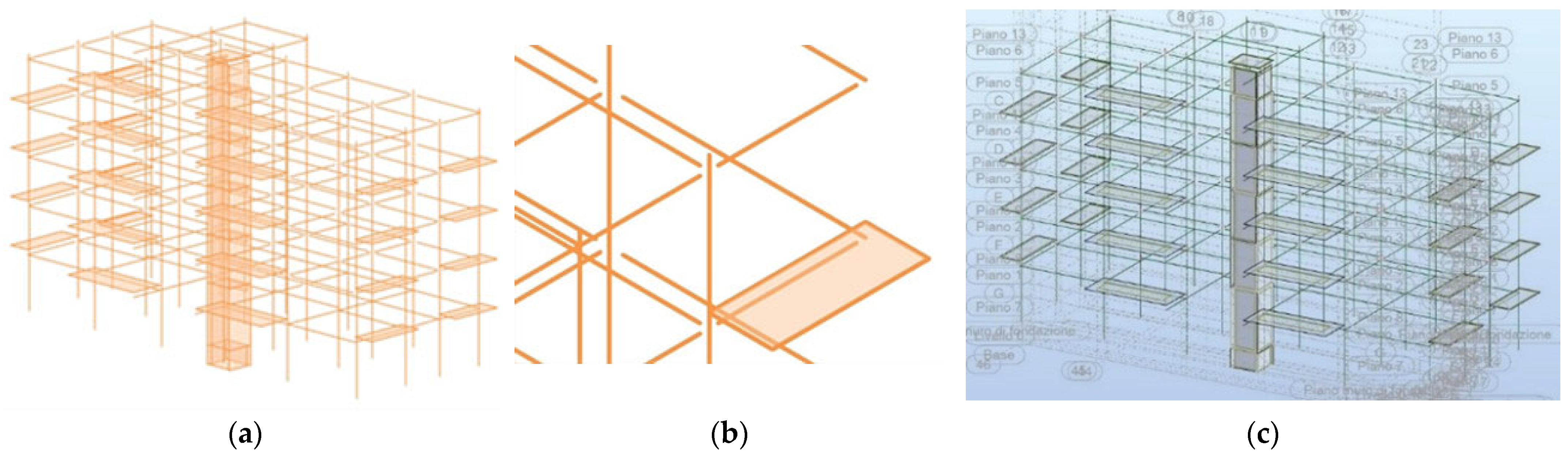

The definition of the structural model began with the export from Revit® of a DXF file containing architectural references, then imported into Jasp, a finite element analysis (FEM) software.

With regard to the DXF-based transfers, only the correspondence of nodes and grids was evaluated (

Table 4). The correct transfer of this information was verified through the subsequent overlay of the elements modeled in JASP with those re-imported into Revit. Although the geometric references imported via DXF fully match, this condition still generates measurable impacts, as it requires additional time for the complete reconstruction of the structural model. This phase, although facilitated by the availability of correctly transferred alignments and nodes, results in increased modeling time and, consequently, higher rework costs.

From the DXF references, fixed lines were generated for the construction of the calculation model. Subsequently, the floors, materials, and sections for beams, columns, walls, and slabs were defined. Beams and columns were inserted by floors, while walls were modeled to represent the elevator shaft, to which a ramp slab staircase with three flights is anchored. Finally, slabs, balconies, and infill walls were added, considering preliminary sizing considerations.

Upon completion of the modeling, the three-dimensional structure model was obtained (

Figure 10). Nodes were left free, except those on the ground floor, which were constrained as fixed supports. Additionally, a foundation slab was inserted in the elevator shaft, although it was not subject to structural verification. The definition of the structural model began with the export from Revit

® of a DXF file containing architectural references, then imported into Jasp, a finite element analysis (FEM) software. Upon completion of the geometric modeling, in which materials and constraints were defined, the definition of actions was carried out, assigning the intended use of the structure. Subsequently, verification and design criteria were set and assigned to each element, essential for reinforcement sizing, geometric verification of elements, and section verification.

After setting the actions and analysis criteria, the structural analysis was initiated, including options for seismic analysis and load combinations. The numerical analysis was conducted using the displacement method, assuming linear-elastic behavior of the elements. The finite element technique was adopted, with connections defined at discrete points called nodes. The design and analysis phase concluded only after verifying all criteria and regulatory conditions, obtaining stress diagrams and structure verification.

The structural model was subsequently exported from the FEM software Jasp in IFC2x3 format, with an unspecified MVD. An analysis of the buildingSMART

® certified IFC software database confirmed the absence of IFC certification for Jasp

®, making it impossible to determine the export requirements adopted. During the export, it was possible to filter the elements, generating two distinct IFC models: one containing only the reinforced concrete structural elements and slabs, and another containing only the reinforcements. An important limitation of the workflow concerns the use of structural analysis software that is not officially certified for IFC import or export, such as JASP

®. The absence of IFC certification prevents verification of the actual implementation of the exchange schema and the supported entity set against the buildingSMART

® requirements. As a result, the IFC output generated by such software may differ from standard-compliant formats in terms of property mapping, element classification, and geometric interpretation. This lack of standardization can lead to partial or inconsistent transfer of information, requiring additional checks and manual adjustments during the coordination process. Moreover, the non-certified nature of the software reduces the predictability and repeatability of interoperability results, limiting the generalizability of the workflow for industry applications where certified openBIM procedures are expected. Nevertheless, given that several widely used FEM tools in professional practice still lack IFC certification, the proposed workflow retains practical relevance by demonstrating how reliable coordination can still be achieved through systematic validation, selective filtering of IFC elements, and rigorous model checking across multiple platforms. Before use, both models were subjected to information transfer checks through visual and content analysis, performed by importing the IFC files into various software. The models were analyzed using IFC viewers BIMvision

® and Solibri Anywhere

®, as well as Revit

® software (versions 2021 and 2024, in both structural and architectural domains) and Navisworks

® (versions 2021 and 2024). The checks revealed significant discrepancies in data interpretation, particularly for the model containing the reinforced concrete structural elements and slabs (

Figure 11a–h). Both IFC viewers correctly interpreted the model (

Figure 11a–c). However, in the architectural domain of Revit

® 2021, the slabs and balconies of the linked IFC model were incorrectly represented (

Figure 11c), while no interpretation errors were found in Revit

® 2024 (

Figure 11d). In the structural domain of Revit

® 2021, in addition to interpretation issues for slabs and balconies, there was a complete loss of information regarding the columns (

Figure 11e). However, this information was still present in the side views of the model. In Revit

® 2024, the interpretation of slabs, balconies, and beams was correct, but the information on columns was still absent (

Figure 11f). The import of the IFC model into Navisworks Manage

® showed results similar to those in the architectural domain of Revit

® (

Figure 11g,h). This could be due to the use of common exchange requirements between Revit

® and Navisworks Manage

® for data import. However, the lack of official IFC certification for Navisworks Manage

® prevented verification of this hypothesis. In the buildingSMART

® database, it was confirmed that Revit

® uses the MVD Coordination View 2.0 for importing IFC2x3 files, both for the structural and architectural domains, but this did not explain the interpretation differences found between the different domains. The software version updates showed a general improvement in IFC information interpretation, suggesting a positive evolution in data interoperability between different platforms.

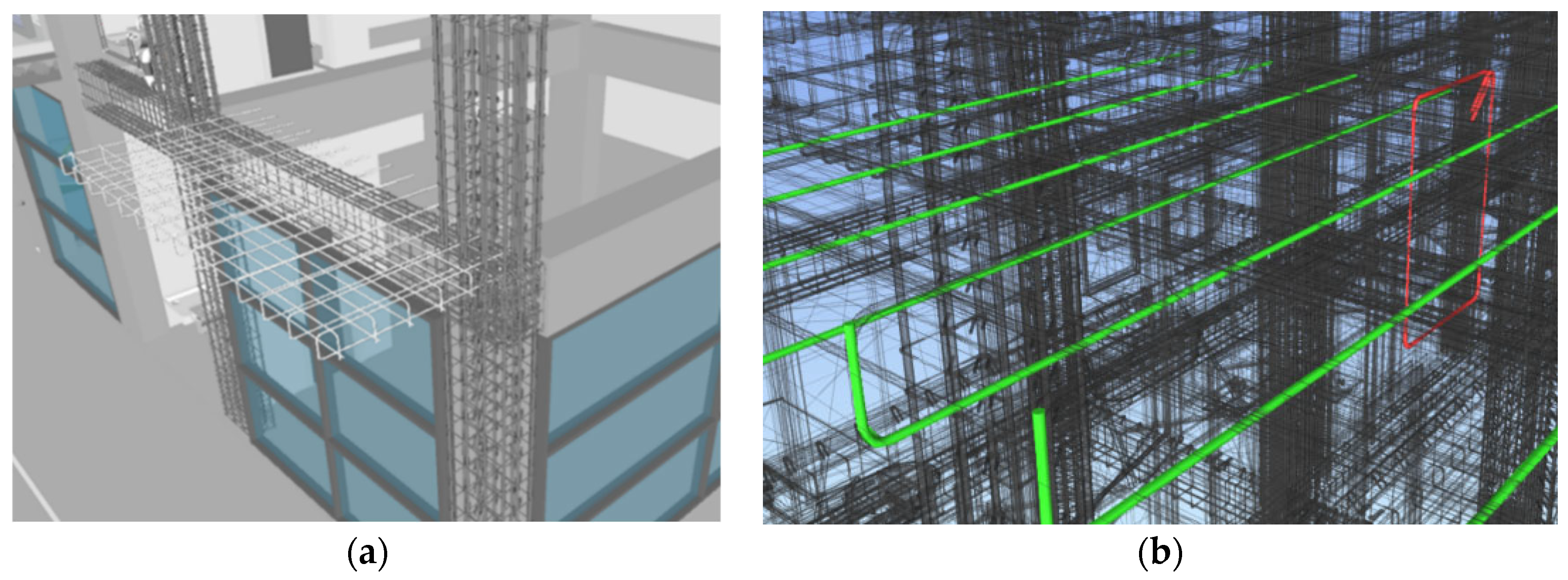

The comparative analysis of the IFC model containing exclusively the reinforcements did not reveal any discrepancies in the interpretation of information among the different software used. Specifically, all the tools employed, including the IFC viewers BIM Vision

® and Solibri Anywhere

®, as well as the 2021 and 2024 versions of Revit

® in the architectural and structural domains and Navisworks Manage

®, correctly processed and represented the reinforcement information without import anomalies or data loss. This result indicates greater robustness and reliability in managing the IFC format for reinforcements compared to reinforced concrete structural elements and slabs, for which interpretative issues had been identified (

Figure 12a–h).

The analysis of the information contained in the IFC files was conducted using the functionalities offered by the Solibri Anywhere® viewer. Within the IFC model related to reinforcements, in addition to geometric information, the material characteristics were also correctly transferred. The reinforcement bars were defined as IfcReinforcingBar entities within the IFC2x3 schema and classified under the architectural discipline. Additional information correctly imported into the IFC model includes the diameter, belonging plane, function, and positioning specifications of each reinforcement bar.

Similarly to the analysis of reinforcements, the information contained in the IFC file of the concrete components of the structure was examined. In this model, four categories of entities were generated: IfcColumn for columns, IfcBeam for beams, IfcWall for reinforced concrete walls, and IfcSlab for slabs, balconies, and plates. For the IFC model of the concrete structural components, the material information was also correctly transferred, except for slabs and balconies. The plate element, although classified with the same IfcSlab entity as slabs and balconies, retained the material information. This result could be attributed to the modeling methods adopted in the finite element software. Specifically, in the Jasp® software, the plate was generated as a Shell element and was not defined within the load section, unlike slabs and balconies.

A quantitative evaluation was also carried out for the BIM-to-FEM transfers from the JASP software using the IFC2x3 format, based on the percentage of structural elements correctly imported after each workflow (

Table 5). The metric was again defined as the ratio between correctly interpreted objects and the total number of modeled objects for each category (columns and beams), as well as for the main geometric characteristics of the model (alignments and nodes). To verify correct importation, the results were compared with the imports performed in the BIMVision and Solibri viewers, where all elements were transferred completely and manually validated. The results show that information related to reinforcement elements and beams is transferred with full reliability across all tested versions, as are the geometric attributes associated with nodes. Information related to columns, however, was entirely absent after the transfer from JASP to Revit, when imported under the structural domain; this condition leads to a proportional loss of accuracy in alignments, which depend on the correct interpretation of column geometry. Information related to slabs was transferred correctly, except in imports performed with Revit 2021, where interpretation anomalies were observed. Finally, regarding the interpretation of information by the Enscape rendering software, the data were also processed correctly, as the transfer was carried out through Revit v.2024 configured in the structural domain.

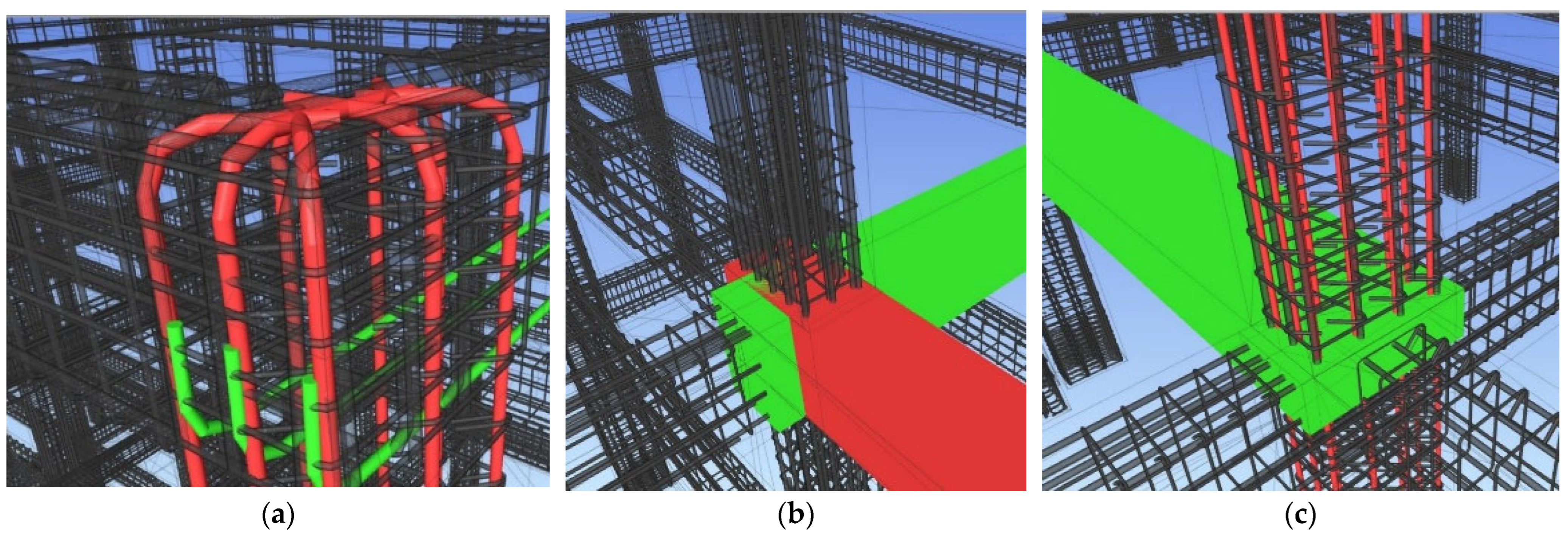

After verifying the correct transfer of information in the structural IFC models, further tests were conducted to evaluate their integration into coordination, clash detection, and analysis software. For this purpose, a geometric clash detection analysis was conducted on the structural IFC models using Navisworks Manage

® v.2024 software. The analysis did not reveal any data interpretation errors in the generated structural IFC models. Structural IFC files were simultaneously imported into Navisworks

®, allowing the creation of a federated structural model. The integration of the two models enabled the verification of the correct placement of the reinforcements within the concrete structure (

Figure 13).

The analysis carried out demonstrated the effectiveness of IFC models in identifying geometric clashes. However, many of the clashes detected by the software do not represent actual geometric conflicts but are instead the result of the IFC model generation algorithm used by the FEM software (

Figure 14). In the examined case, “real” clashes refer exclusively to intersections between different elements, such as two reinforcement bars belonging to separate groups or interferences between unrelated structural components. These situations require design correction or model refinement. Conversely, several clashes reported as geometric conflicts should not be interpreted as errors, as they represent physiological intersections inherent to structural modeling. These include, for example, intersections between concrete components at structural nodes, or the apparent interference between the reinforcement of one beam and the concrete of another connected beam. These events arise from the natural overlapping of different structural node elements and do not constitute real design problems. The classification of real clashes is currently entrusted to BIM Coordinators or BIM Managers, who manage them through the functionalities available in Navisworks

®. However, to further improve the accuracy of the verification process, a potential future development of coordination software could include the implementation of specialized algorithms capable of automatically filtering these non-critical geometric intersections, thereby distinguishing more effectively between permissible intersections and genuine design conflicts. An even more advanced evolution could involve the use of artificial intelligence algorithms for the automatic classification of clashes, capable of learning from recurring patterns in structural models and progressively improving the accuracy of clash identification.

The tests conducted have demonstrated that the creation of a structural model in IFC format allows for the correct identification of potential construction interferences already in the design phase. Additionally, structural IFC models offer the possibility to visualize the model even on-site, proving particularly useful in complex situations where the interpretation of 2D executive drawings may generate doubts. This approach optimizes the computation of reinforcement and structural quantities, enhancing both time efficiency and accuracy. The quantities of structural elements and reinforcement requirements can be automatically extracted from the digital model, reducing manual intervention and minimizing the risk of errors. Furthermore, it facilitates more precise project planning and optimized resource management, contributing to greater efficiency and streamlining of construction processes [

35].

The structural IFC model of reinforcements, generated with the FEM analysis software Jasp, is not completely accurate as it does not include the reinforcements of all types of structural elements, such as balconies. This situation is common in professional practice, where it may be necessary to perform structural analyses with different software and subsequently integrate the results into a complete structural model. To simulate this circumstance, the reinforcements of the balconies were modeled with Revit

® software, in order to verify the model checking functionalities between reinforcement elements from different software (

Figure 15). From the clash detection analysis performed on the federated model, which includes both the structural model created with Revit and the structural IFC model generated with Jasp, it emerges that the information from the two structural models is correctly combined and interpreted. This process allows for the identification of all possible interferences between the balcony reinforcement group and the beam reinforcements. The integration of structural models into a single federated model allows for a more precise evaluation of geometric interferences, improving project quality and reducing the risk of errors during the construction phase. The ability to detect geometric interferences between structural elements from different software is essential to ensure project consistency and reliability, facilitating collaboration among the various professionals involved. Furthermore, the use of advanced clash detection tools, such as those offered by Navisworks

®, allows BIM Coordinators and Managers to effectively manage the detected interferences, optimizing the project review and approval process. This integrated approach helps improve communication between design and construction teams, ensuring that all issues are addressed promptly and accurately.

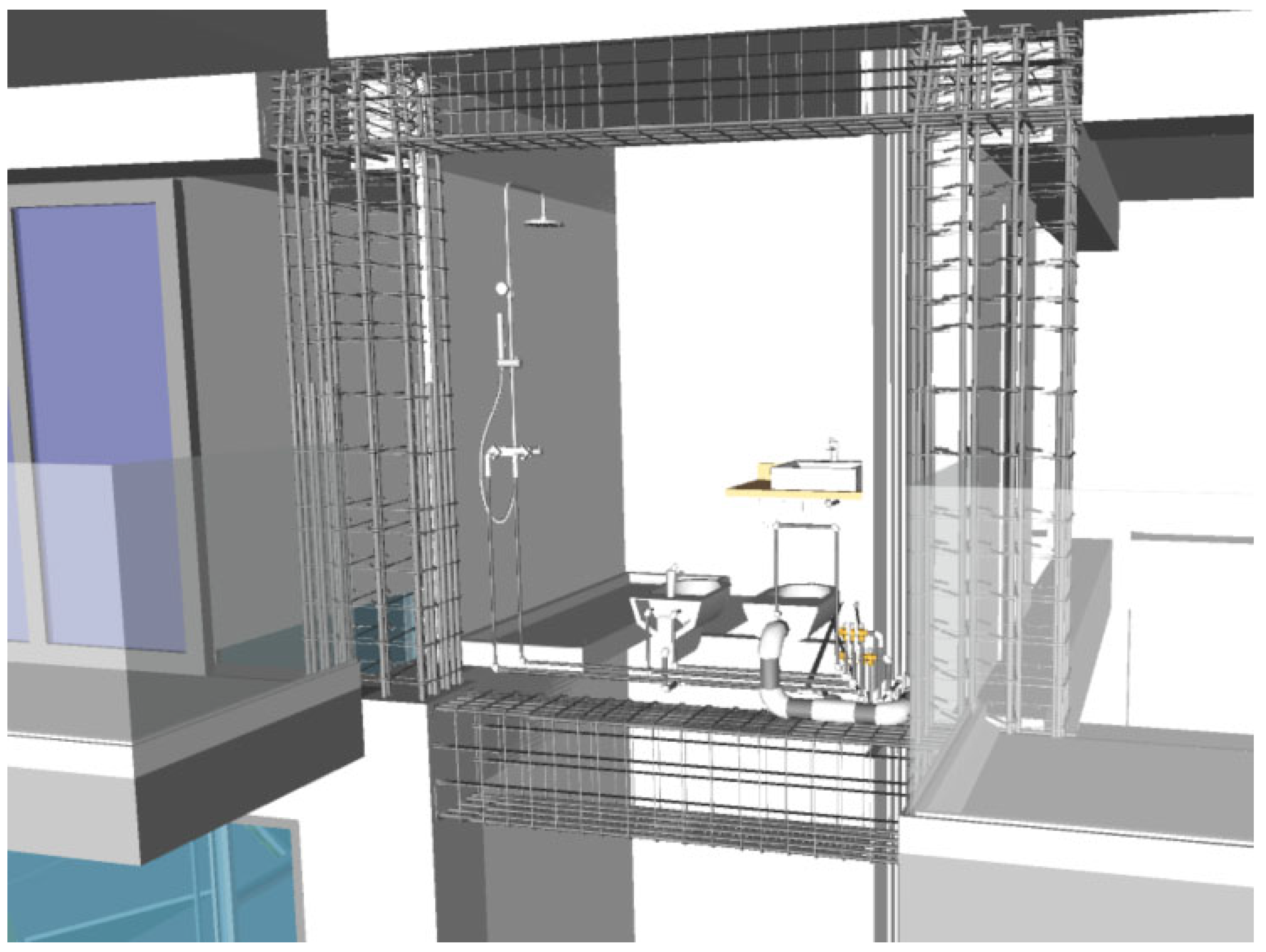

An additional test for the interpretation of information was conducted to verify whether the data from the structural IFC model, imported into Revit

®, were correctly interpreted by the plug-ins installed on Revit

®. In this case, the test was limited to the use of the Enscape plug-in, which allows for rendering and virtual reality (VR) visualizations of the models. From the tests conducted, it emerged that the information from the imported IFC model is perfectly combined and visualized together with the Revit model data. This allowed for the generation of photorealistic views of the structural IFC model and navigation within it in VR mode using appropriate headsets (

Figure 16). The integration of IFC model information with Revit

® model data, even using plug-ins like Enscape

®, represents a significant advancement in the visualization and interpretation of structural data. This approach allows for greater precision in model representation and facilitates the understanding of complex structures, improving project quality and construction process efficiency.