Behavior of Nonconforming Flexure-Controlled RC Structural Walls Under Reversed Cyclic Lateral Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

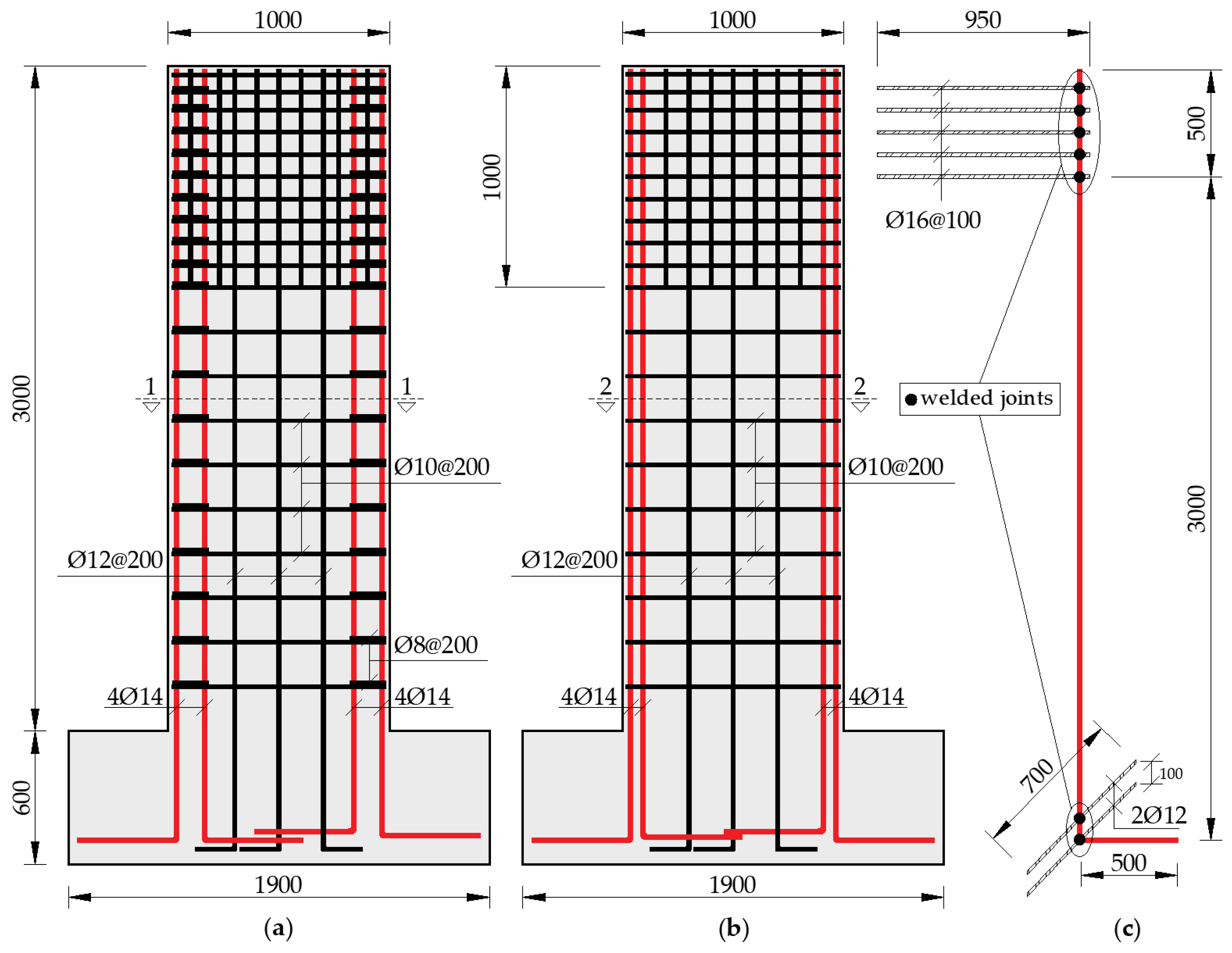

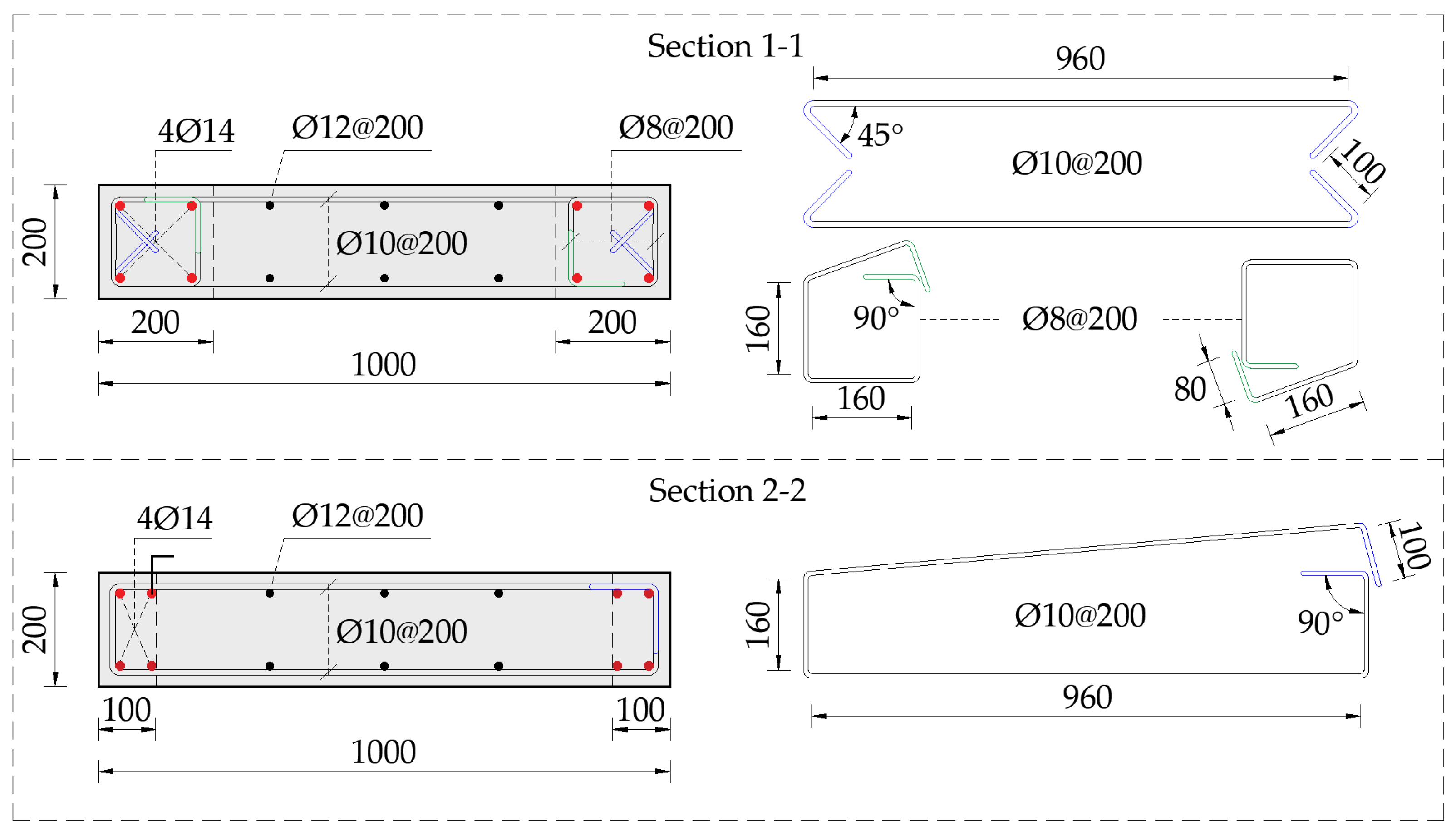

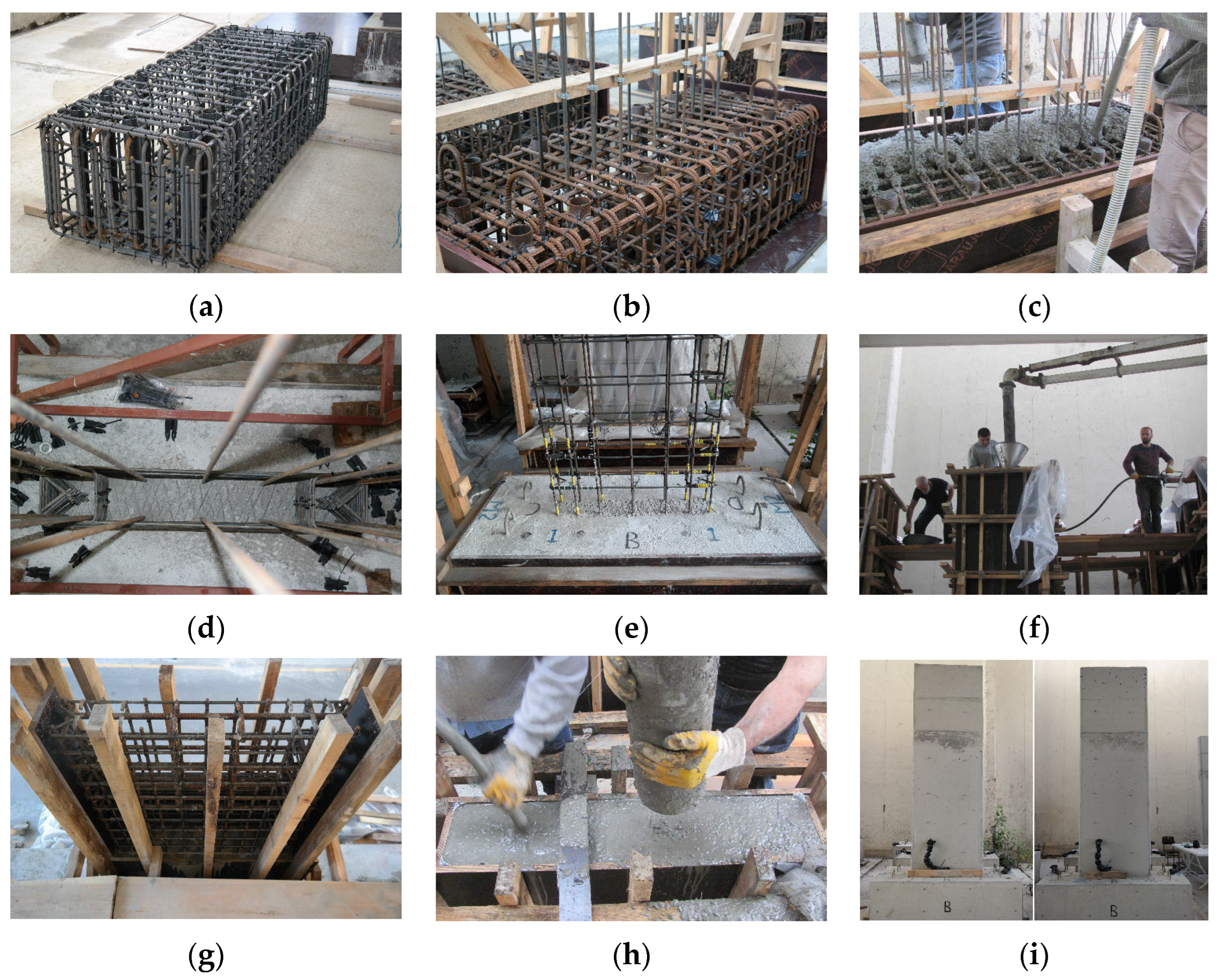

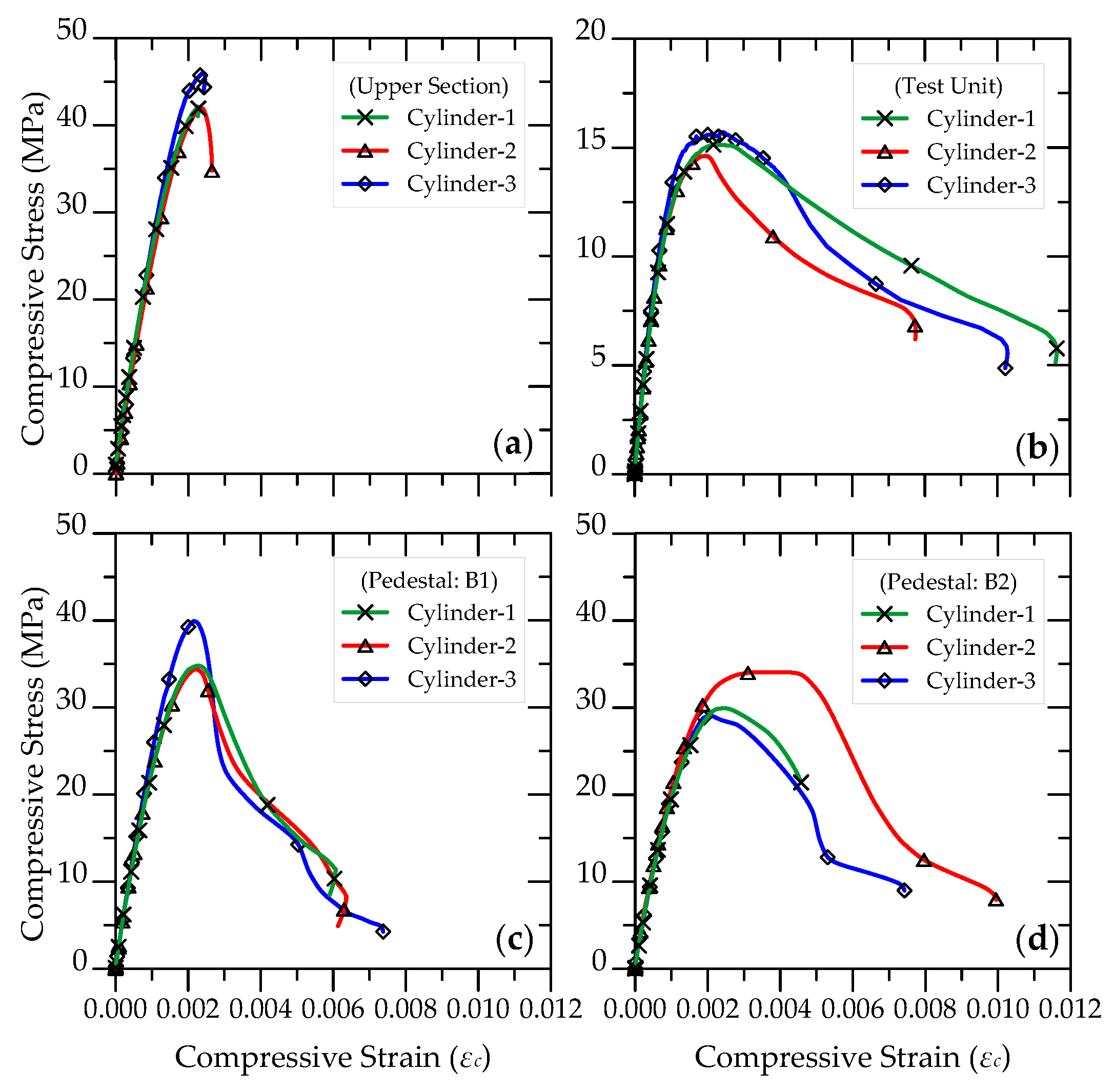

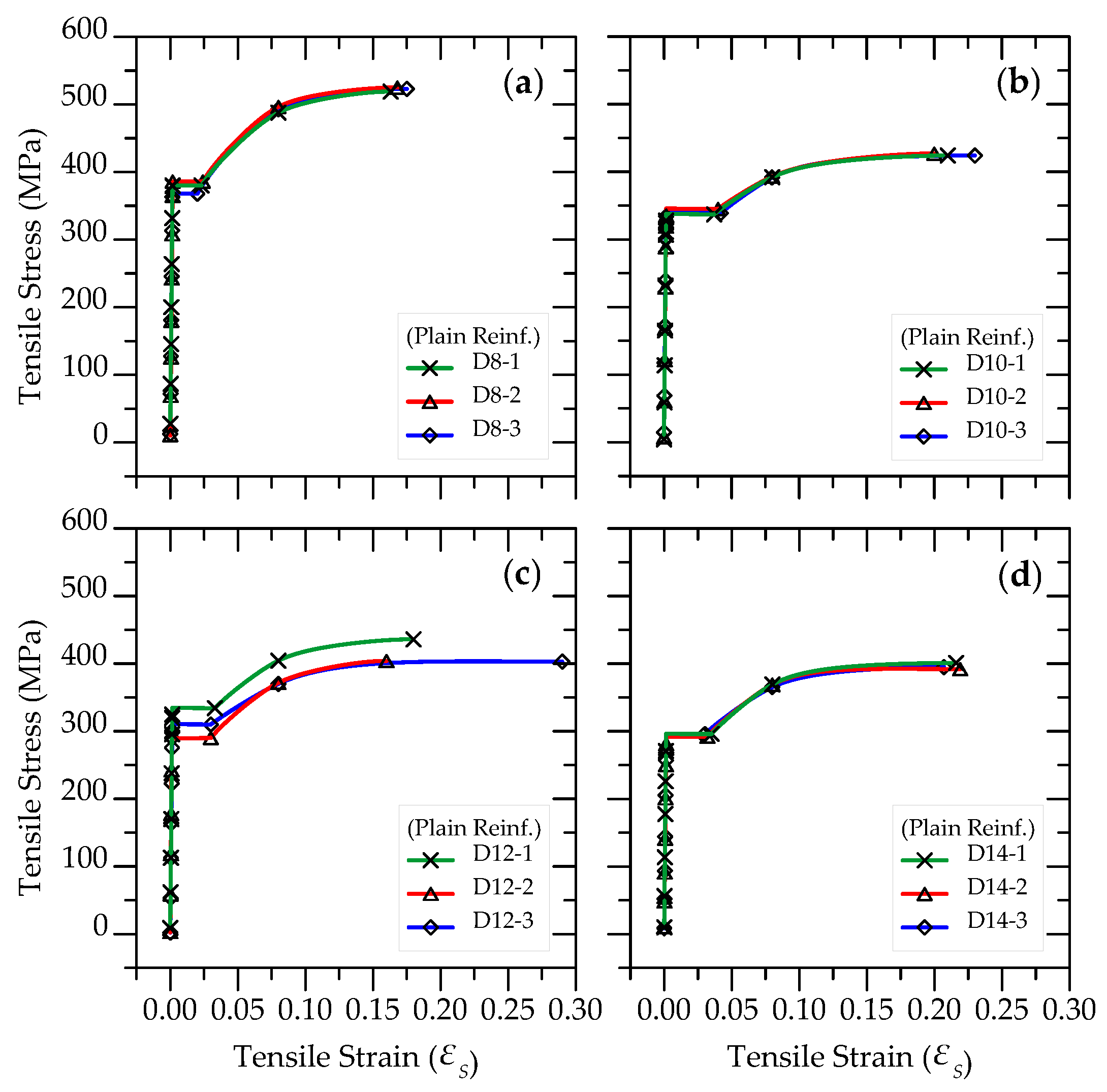

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Description of the Wall Specimens

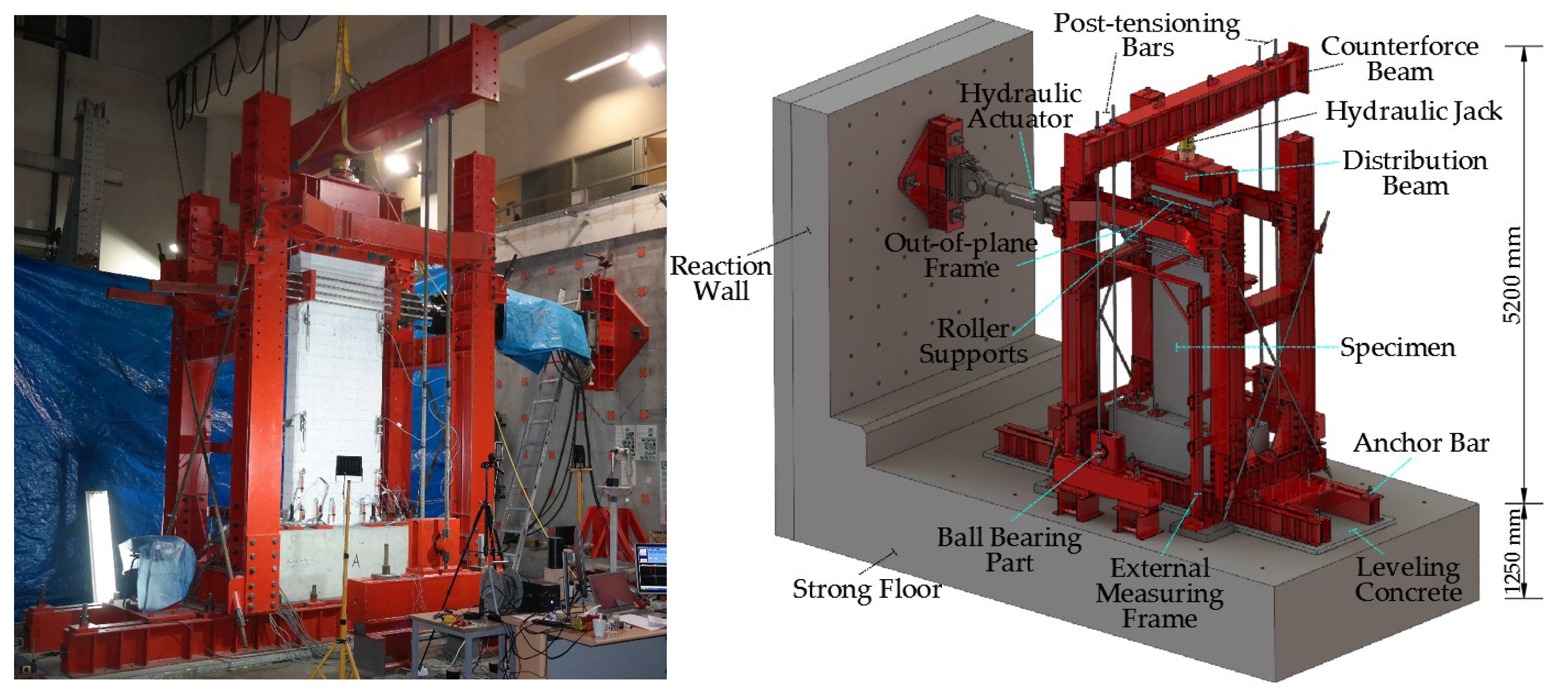

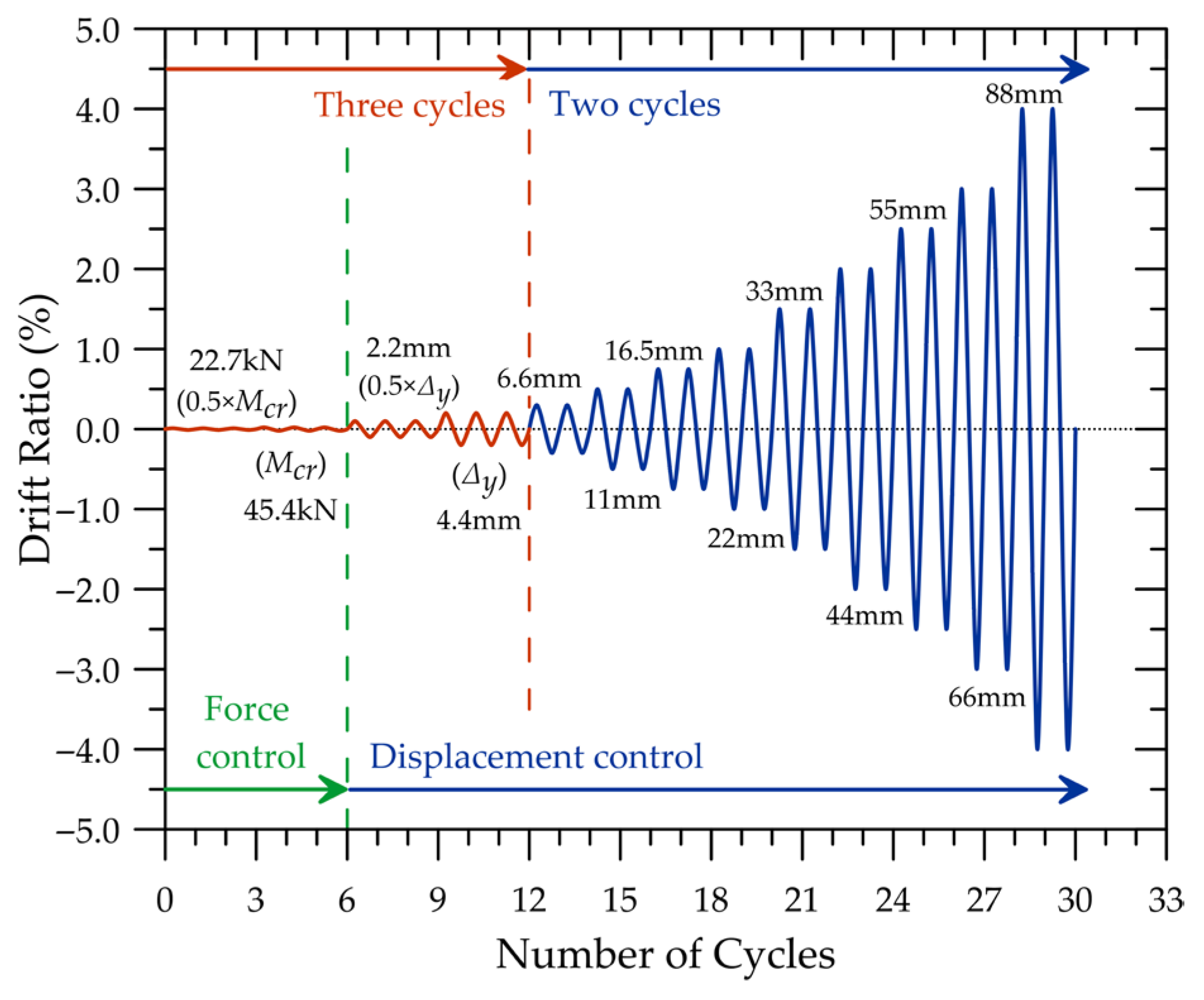

2.2. Experimental Setup and Loading History

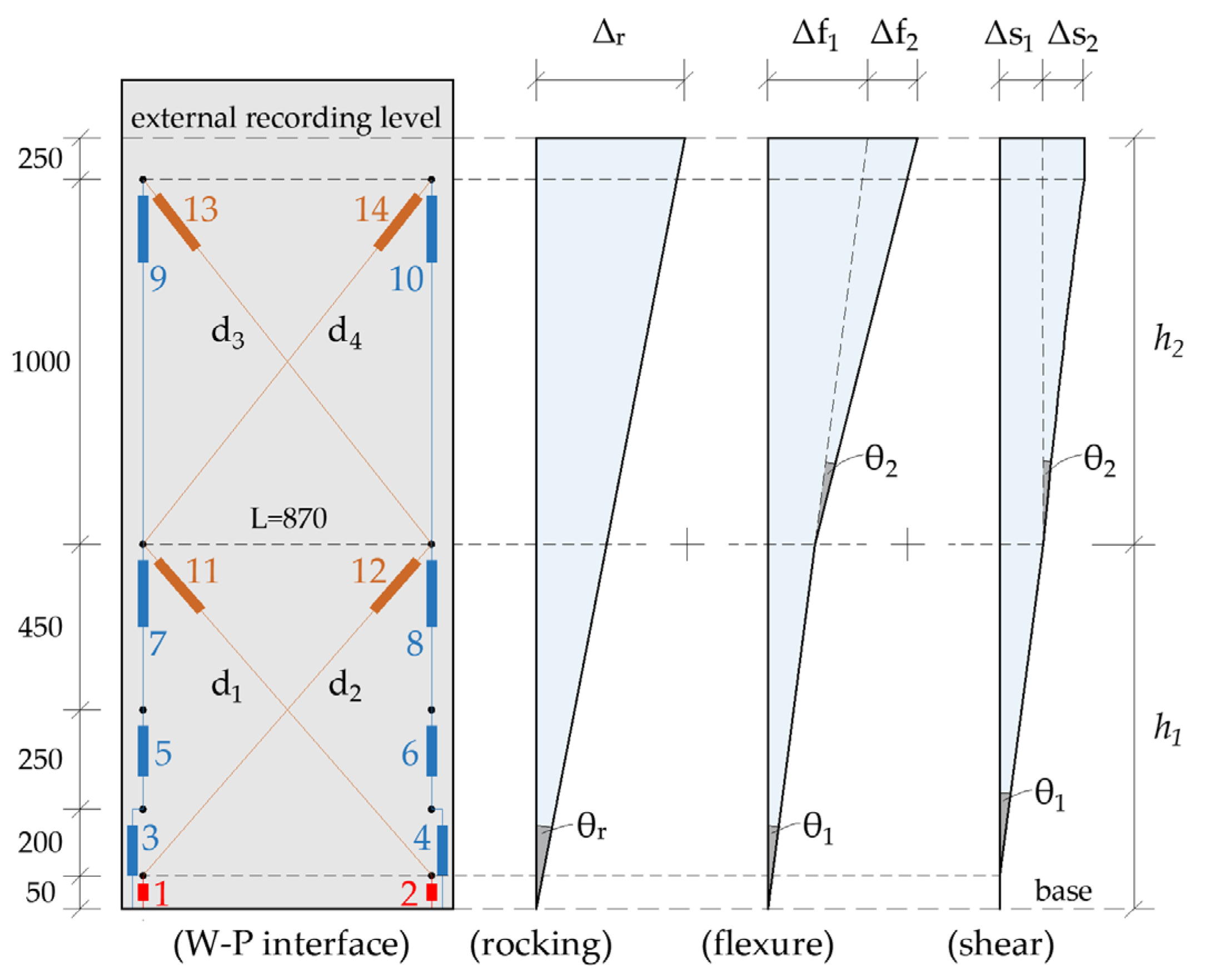

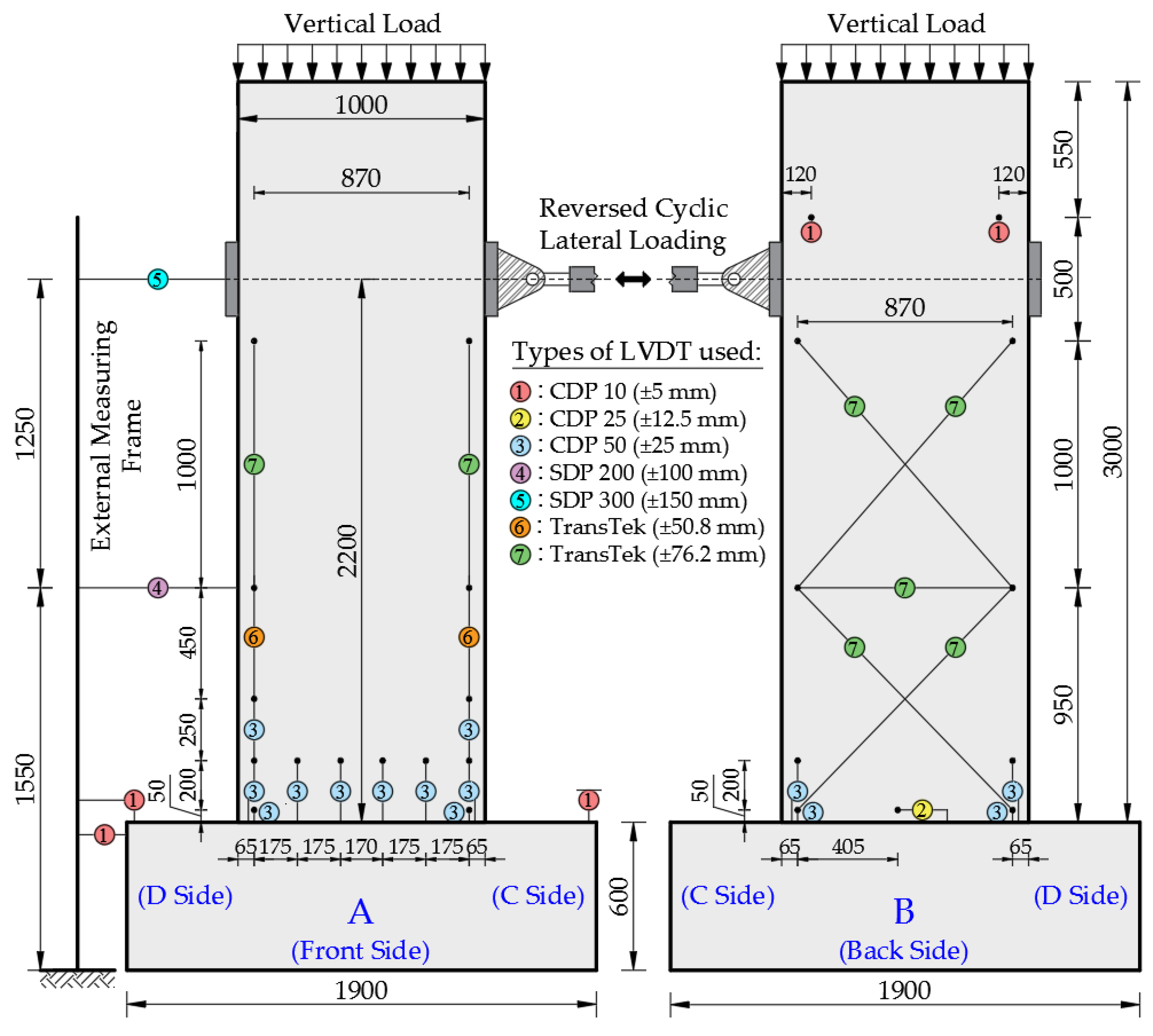

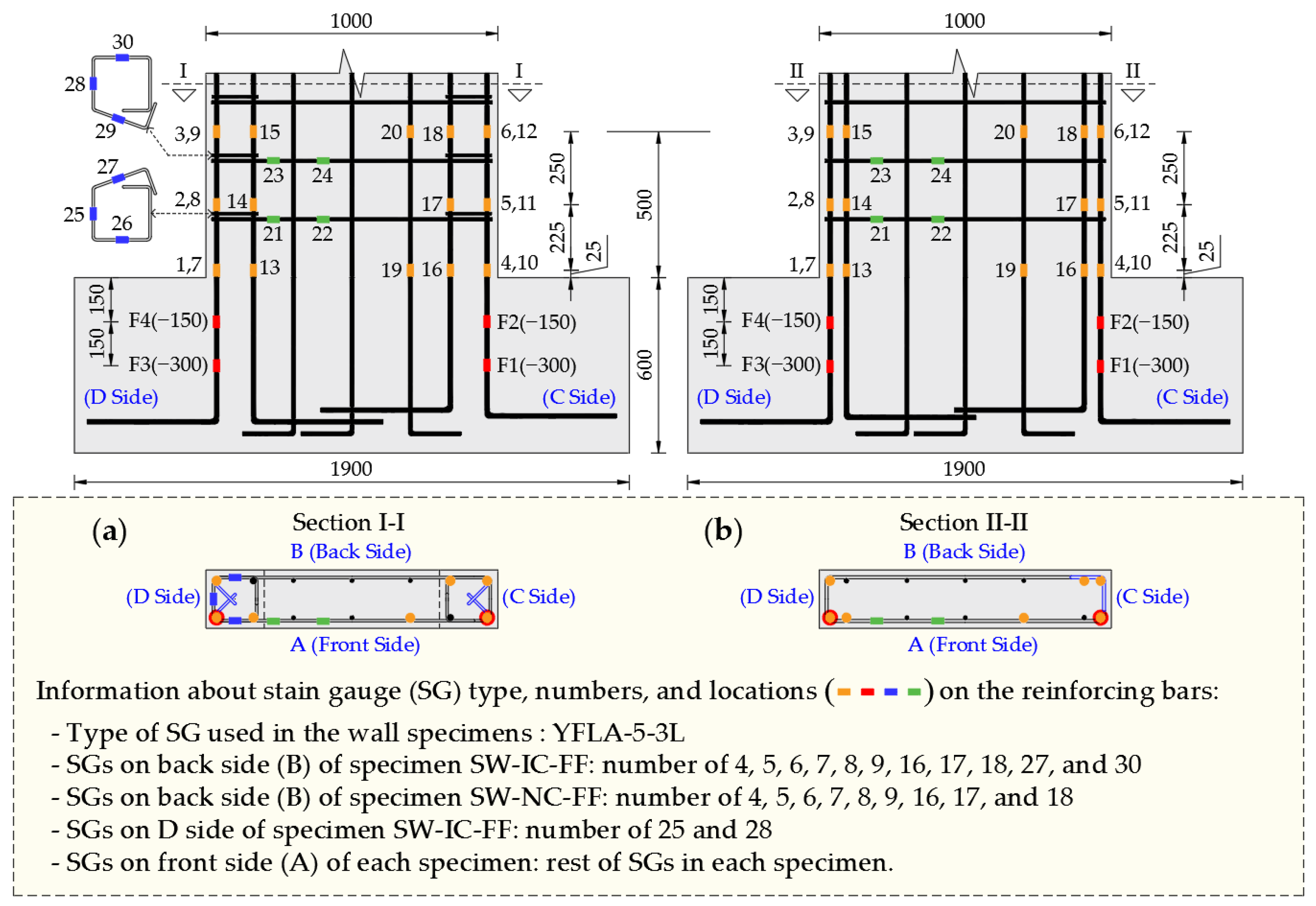

2.3. Instrumentation

3. Experimental Results

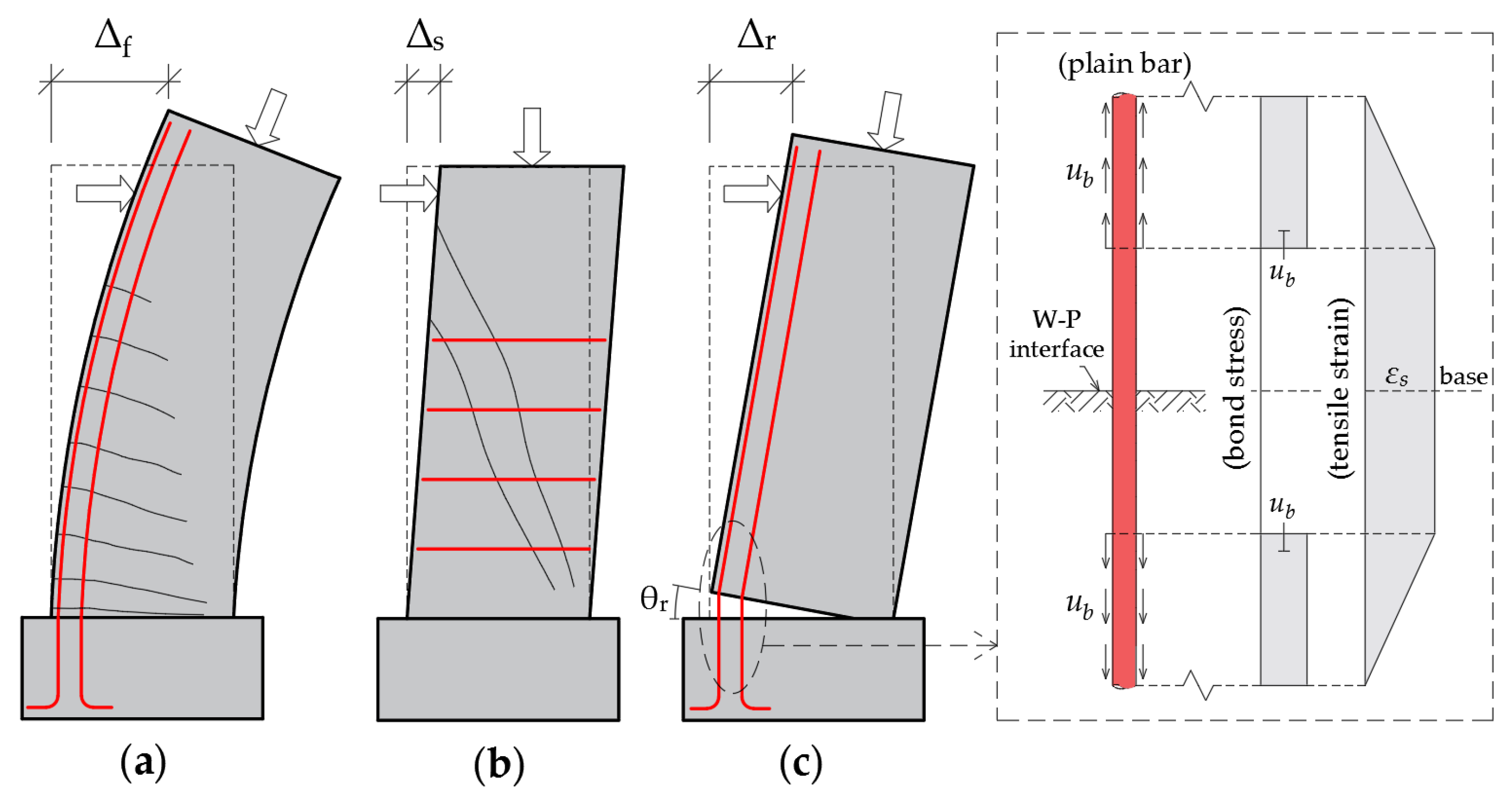

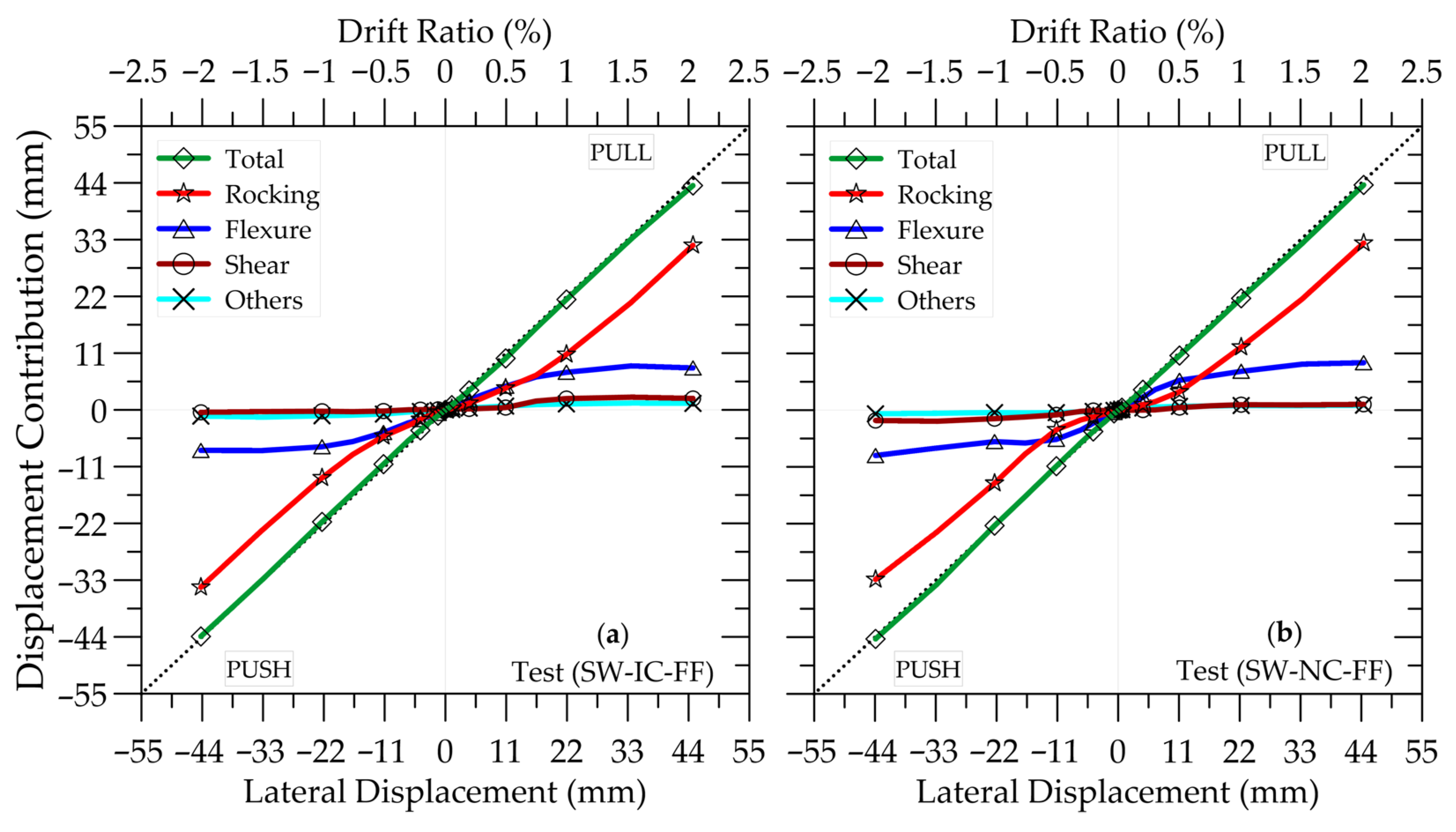

4. Discretizing of Deformation Contributions to Wall Displacements

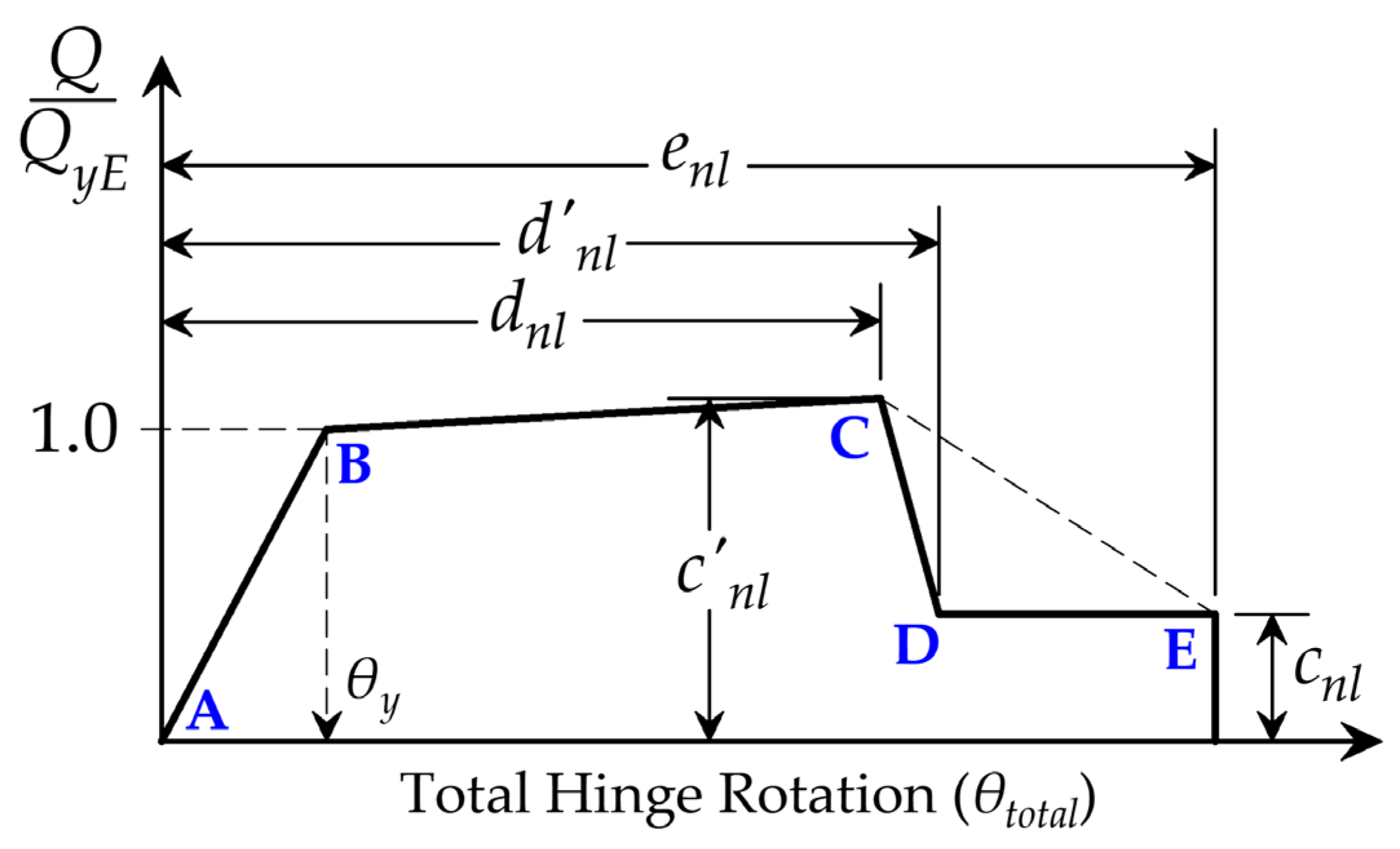

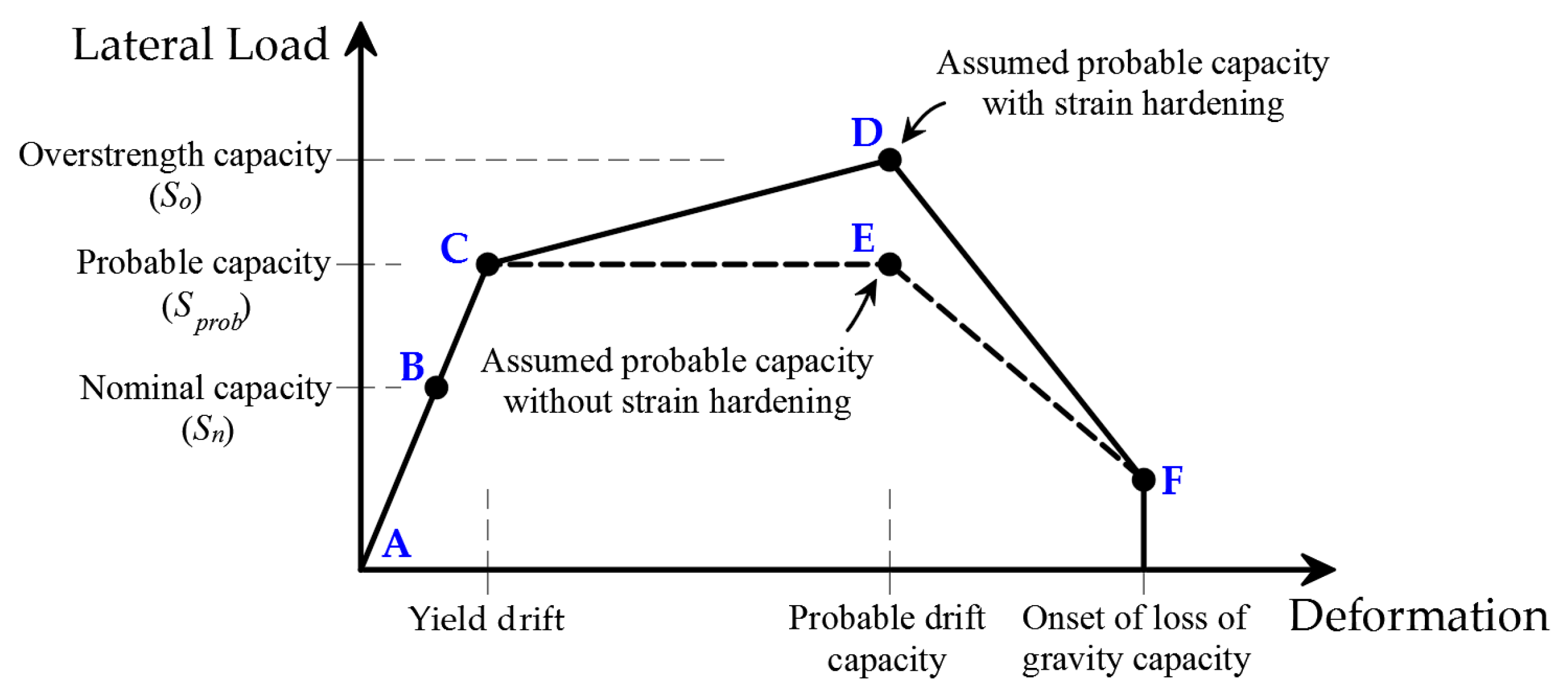

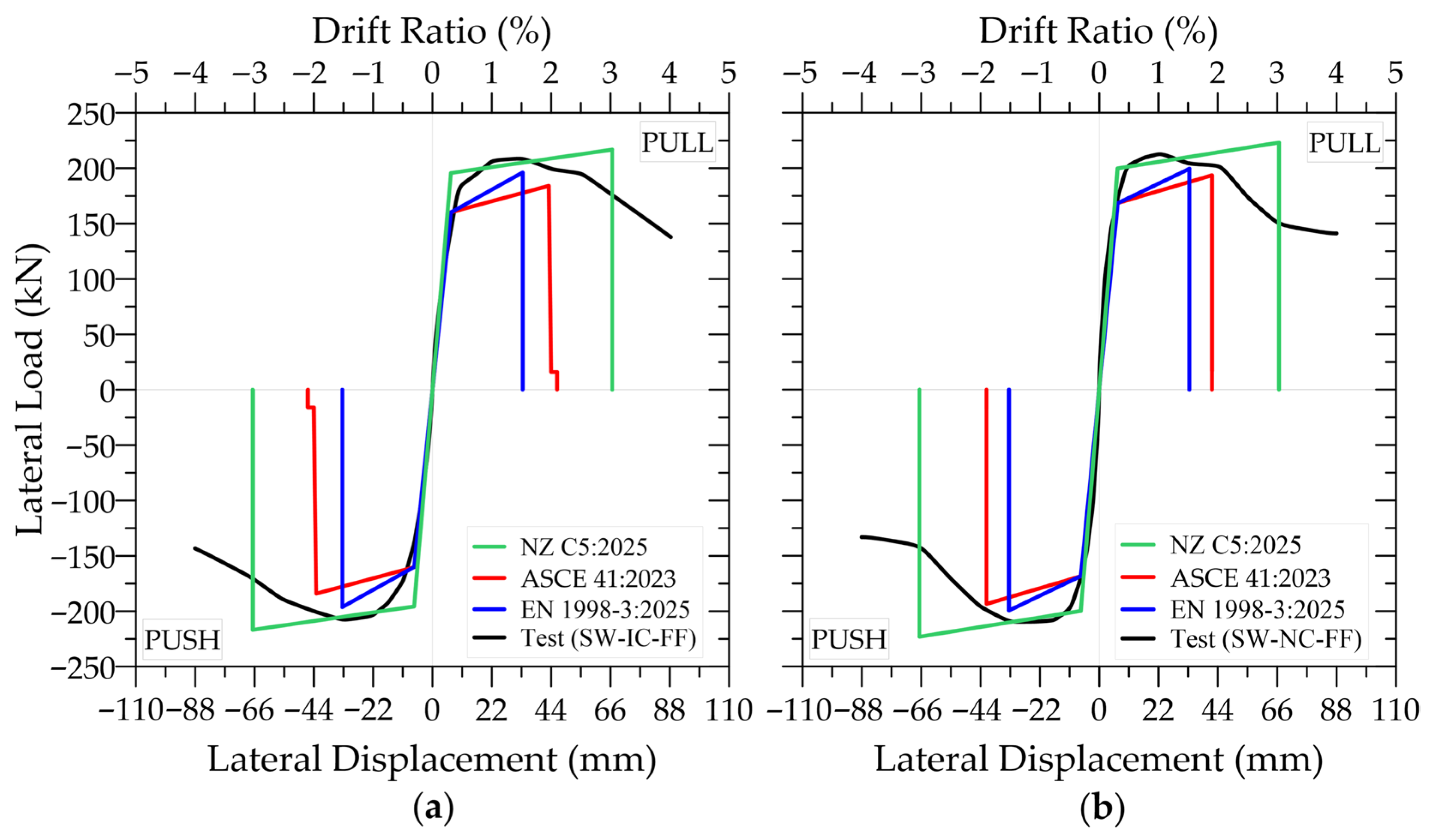

5. Comparison of Test Results with Backbone Curves Defined in Assessment Guidelines

6. Summary and Conclusions

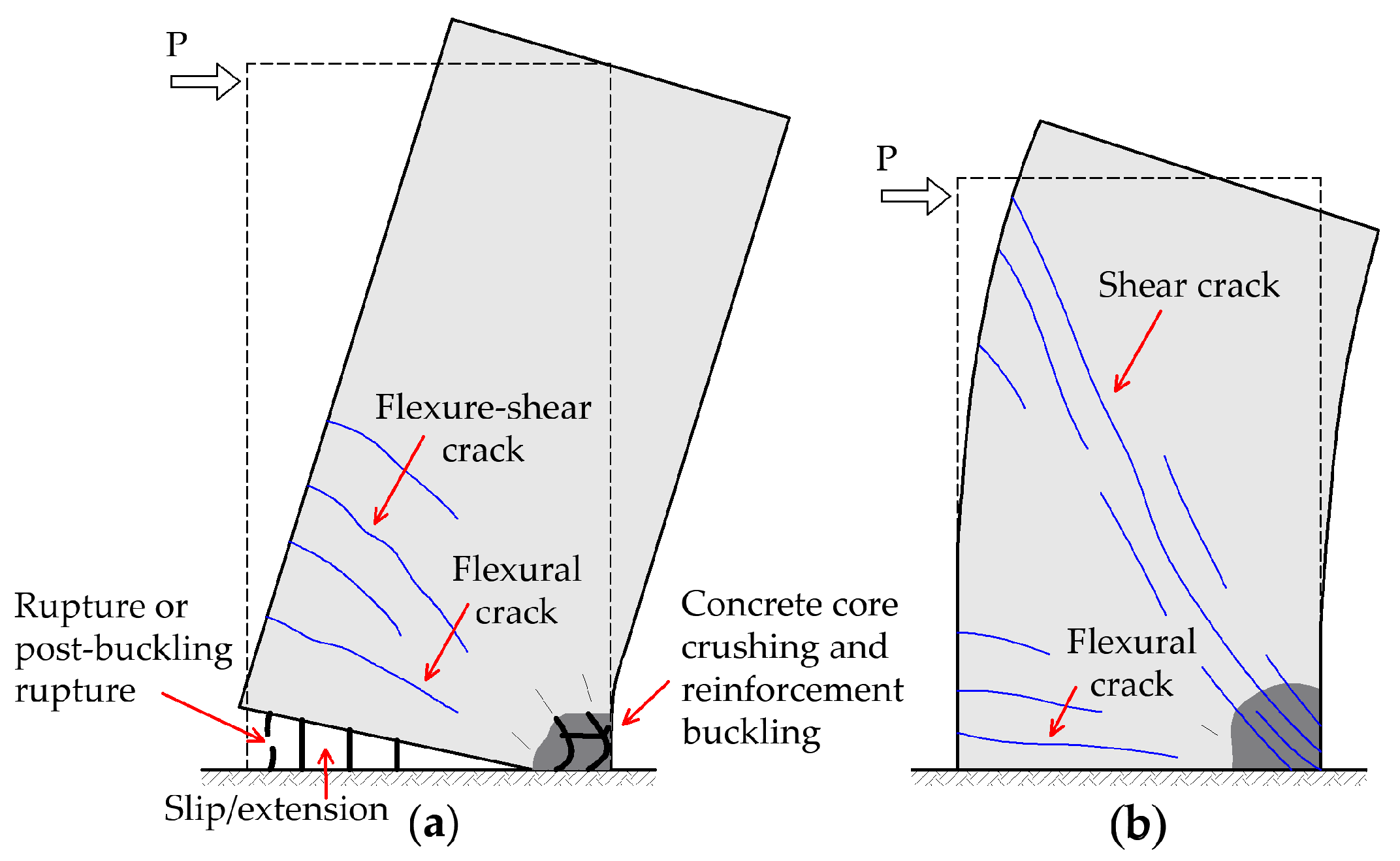

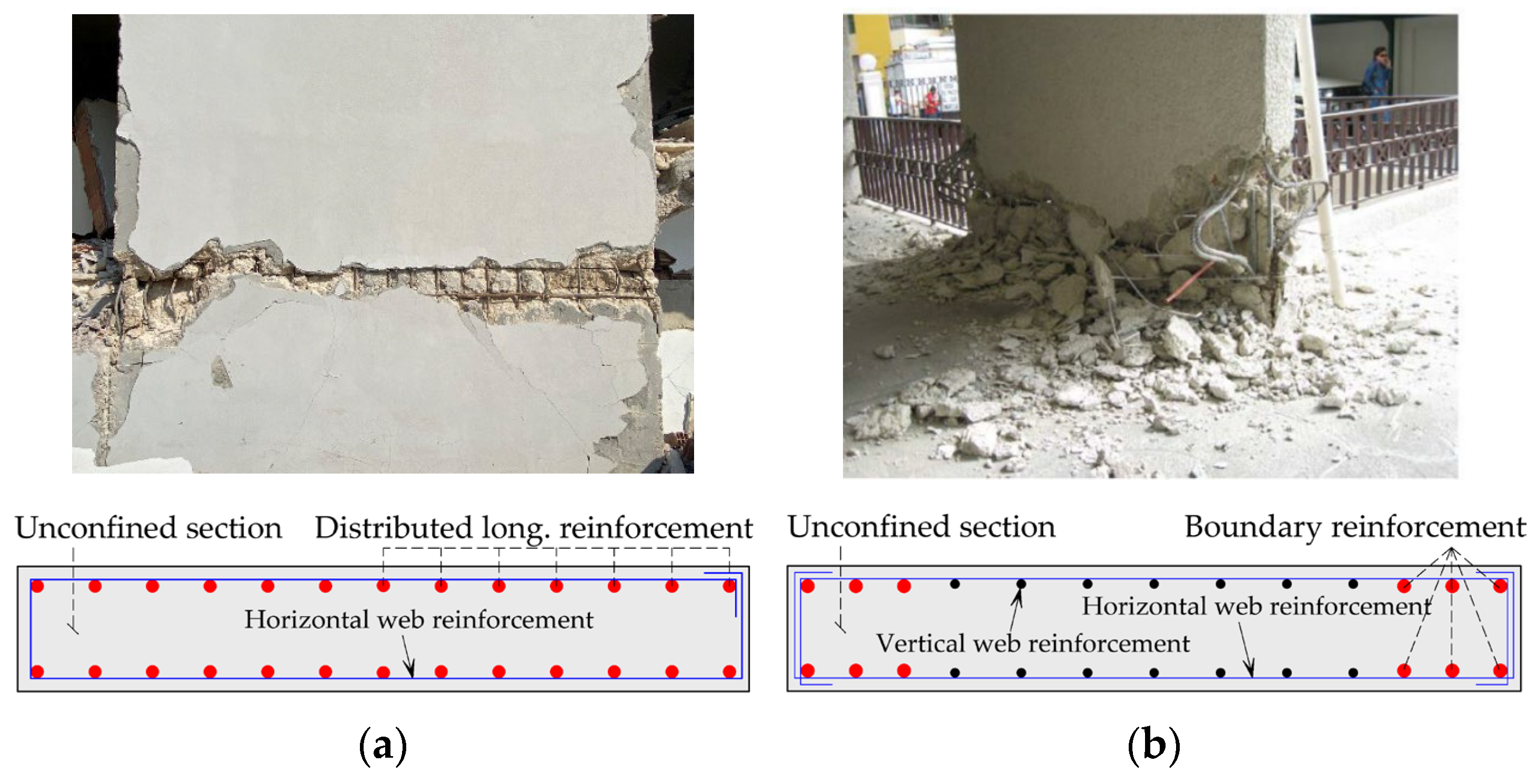

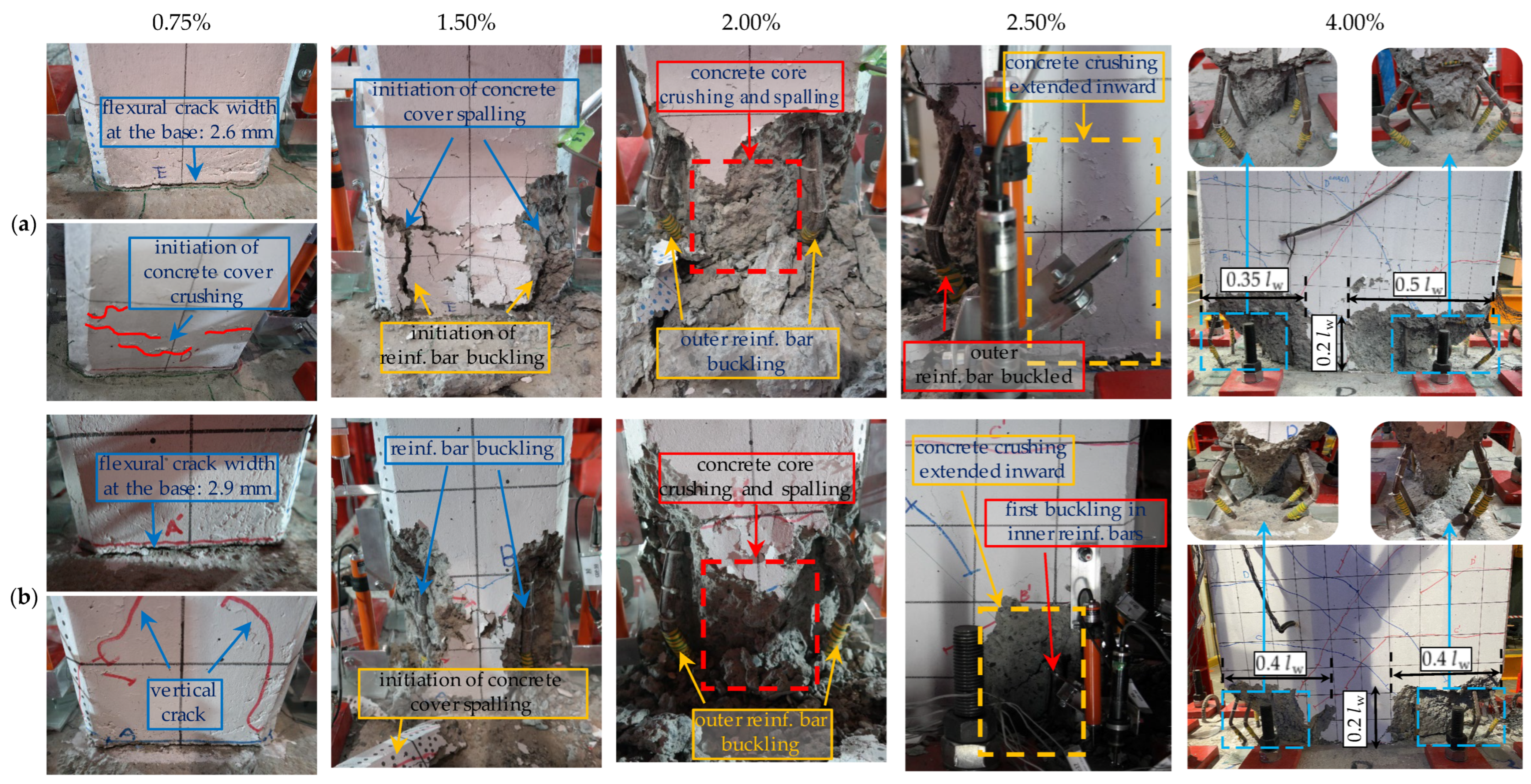

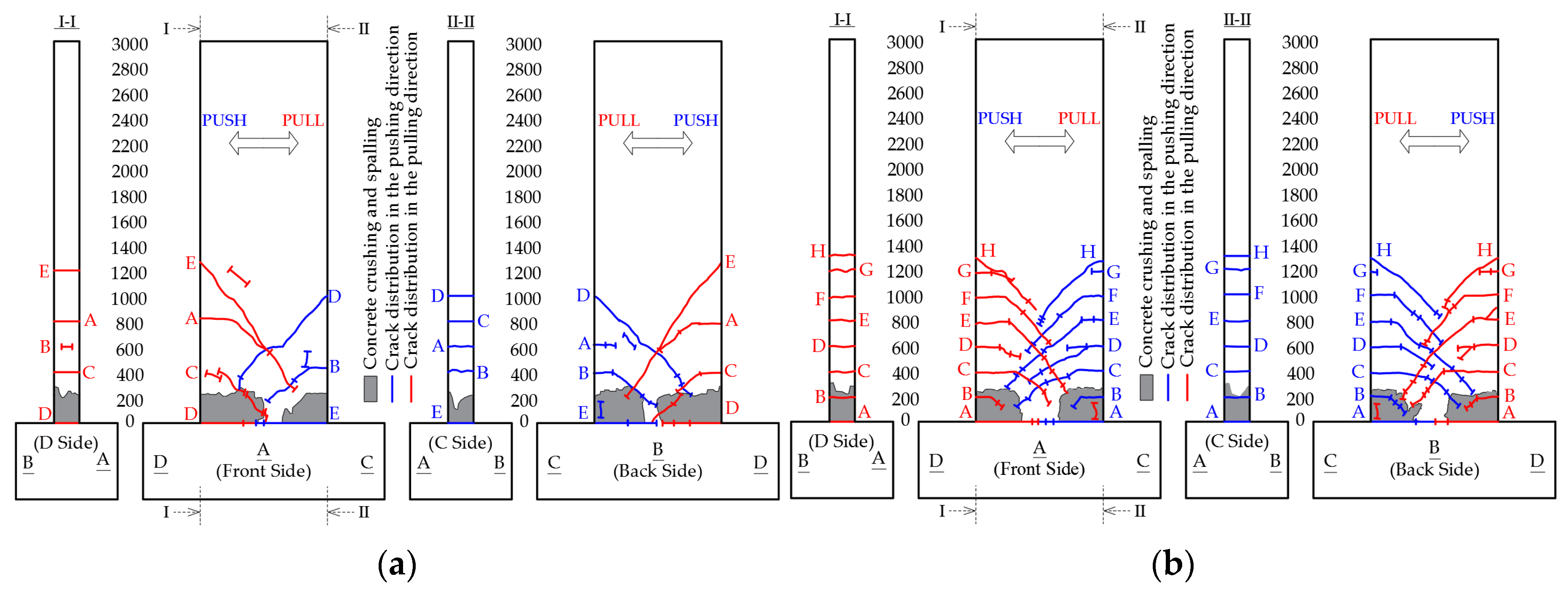

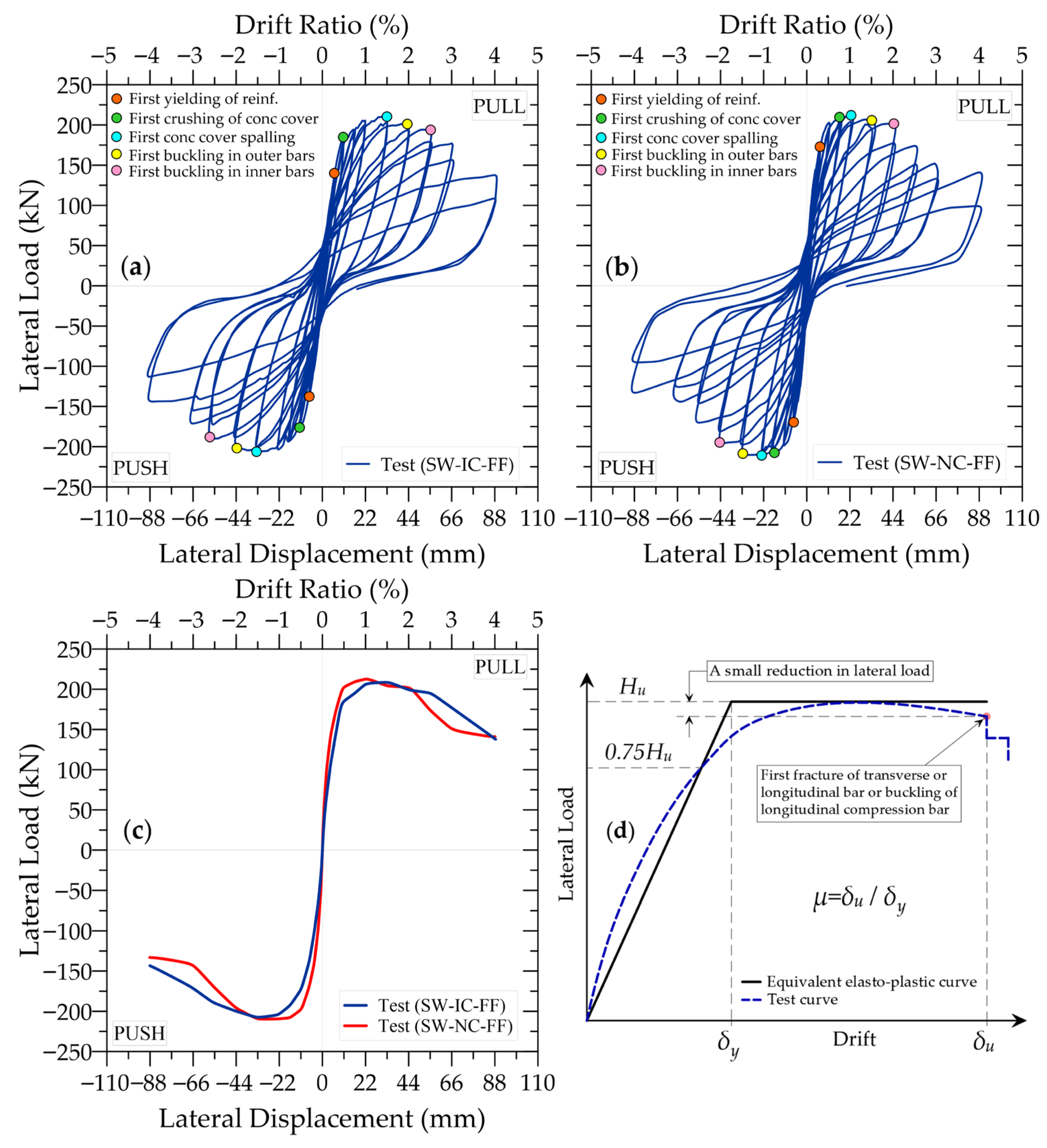

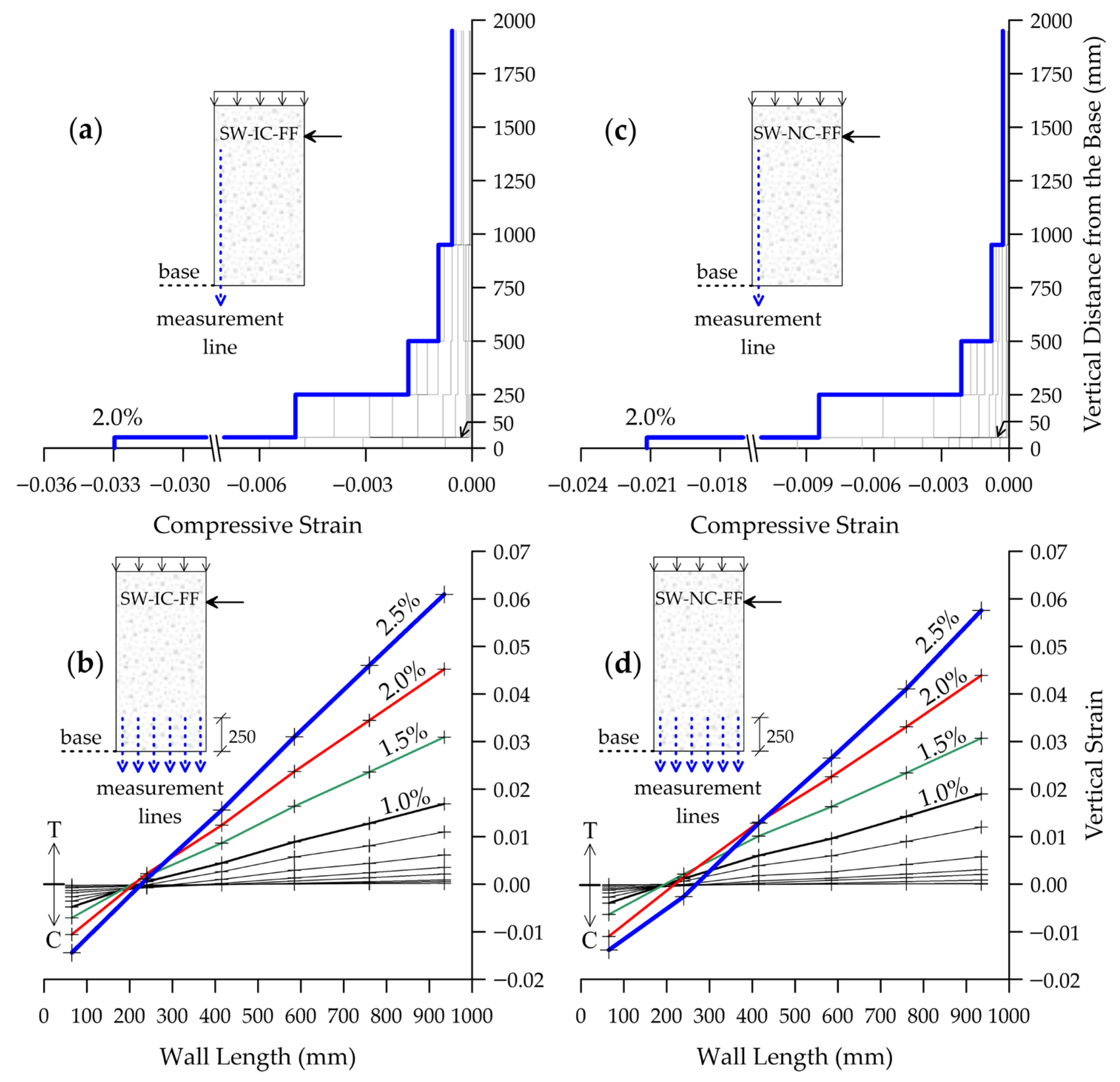

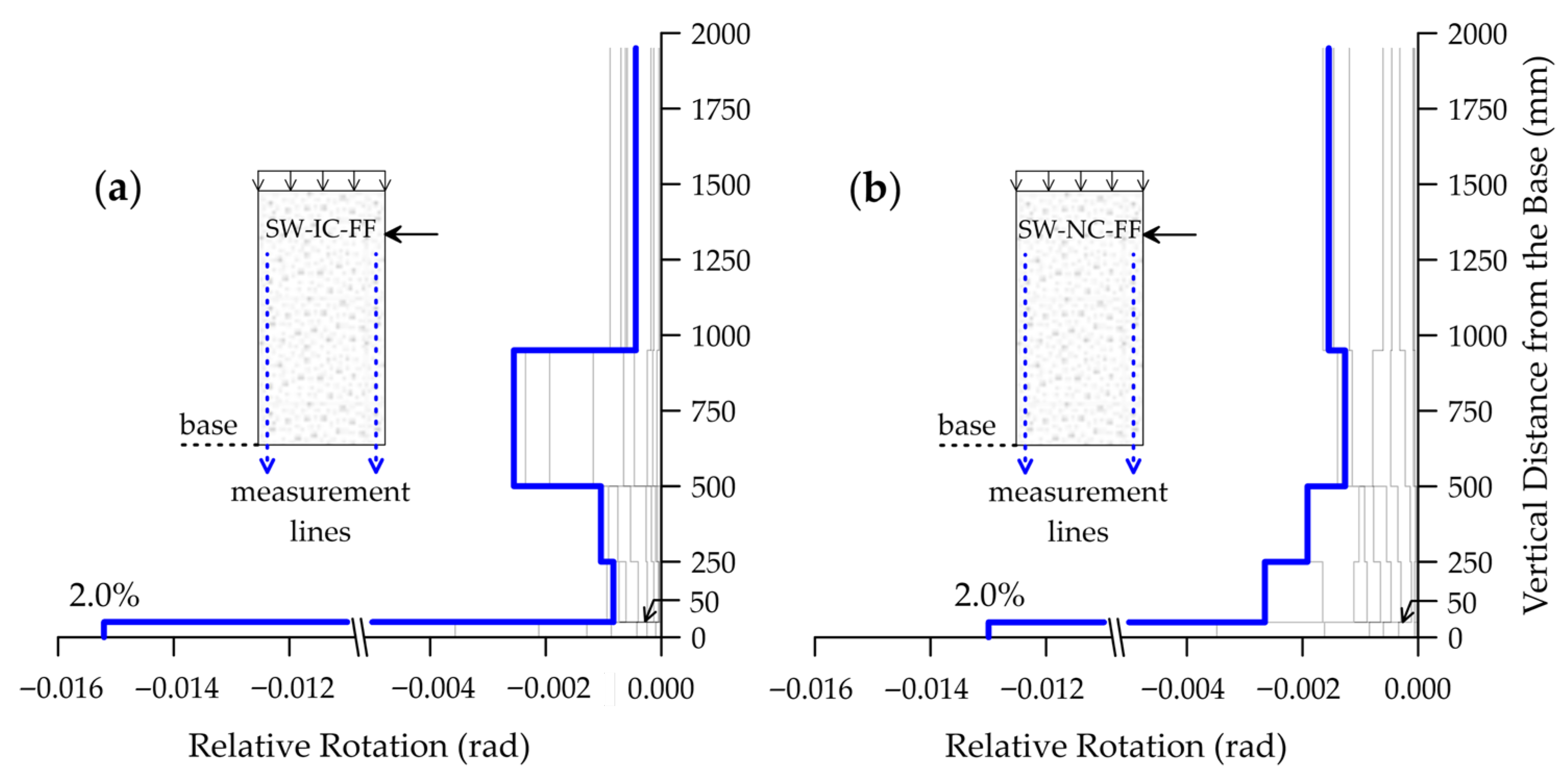

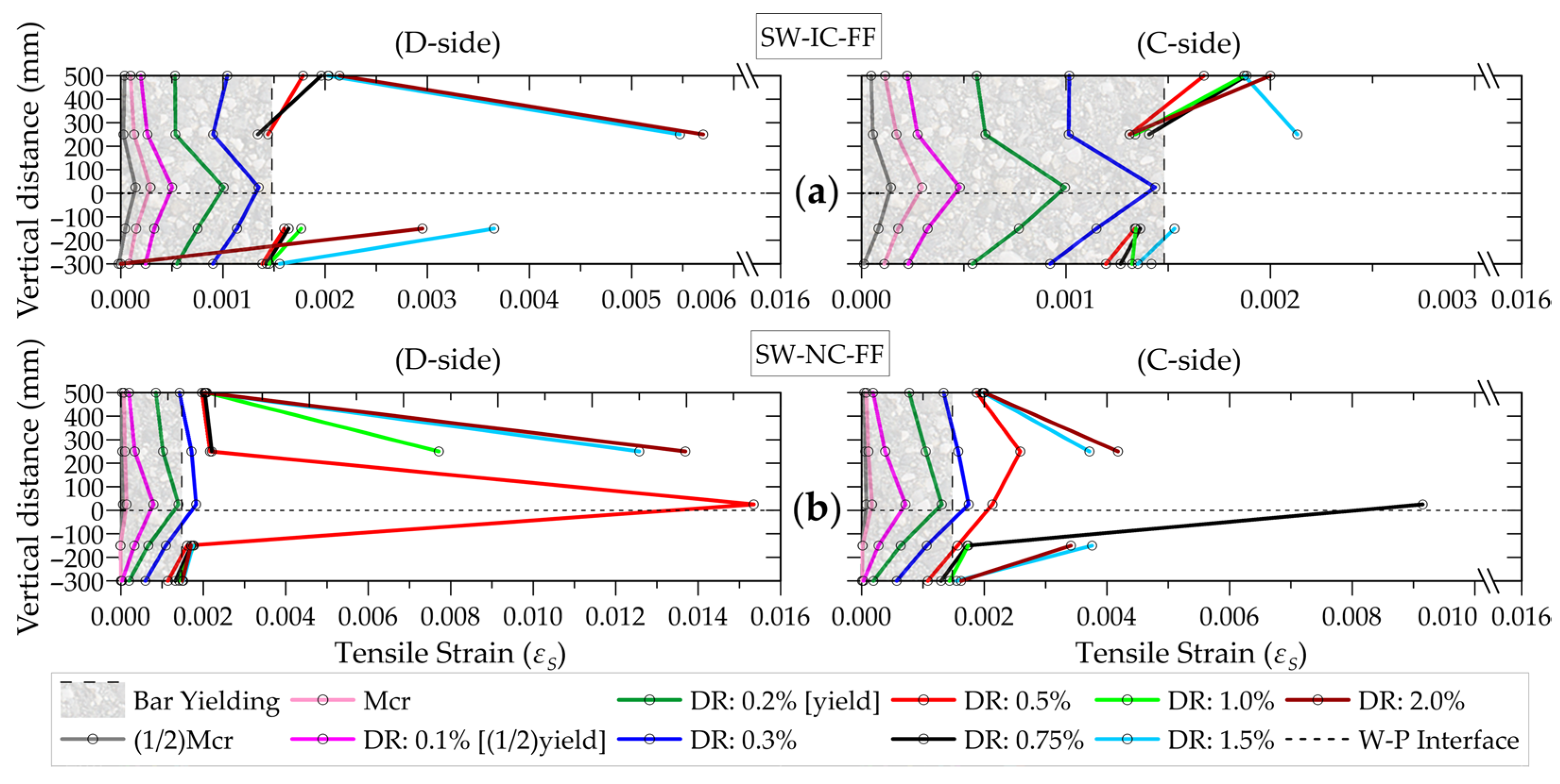

- Both the SW-IC-FF and SW-NC-FF specimens predominantly exhibited flexural-dominated behavior. In each specimen, a principal crack initiated at the W–P interface and progressively widened as the drift ratio increased during the test. Yielding of the longitudinal boundary reinforcement was observed at approximately 0.30% drift ratio, with maximum tensile strains of 0.006 in SW-IC-FF and 0.015 in SW-NC-FF. In both specimens, the horizontal web reinforcement did not yield, as expected.

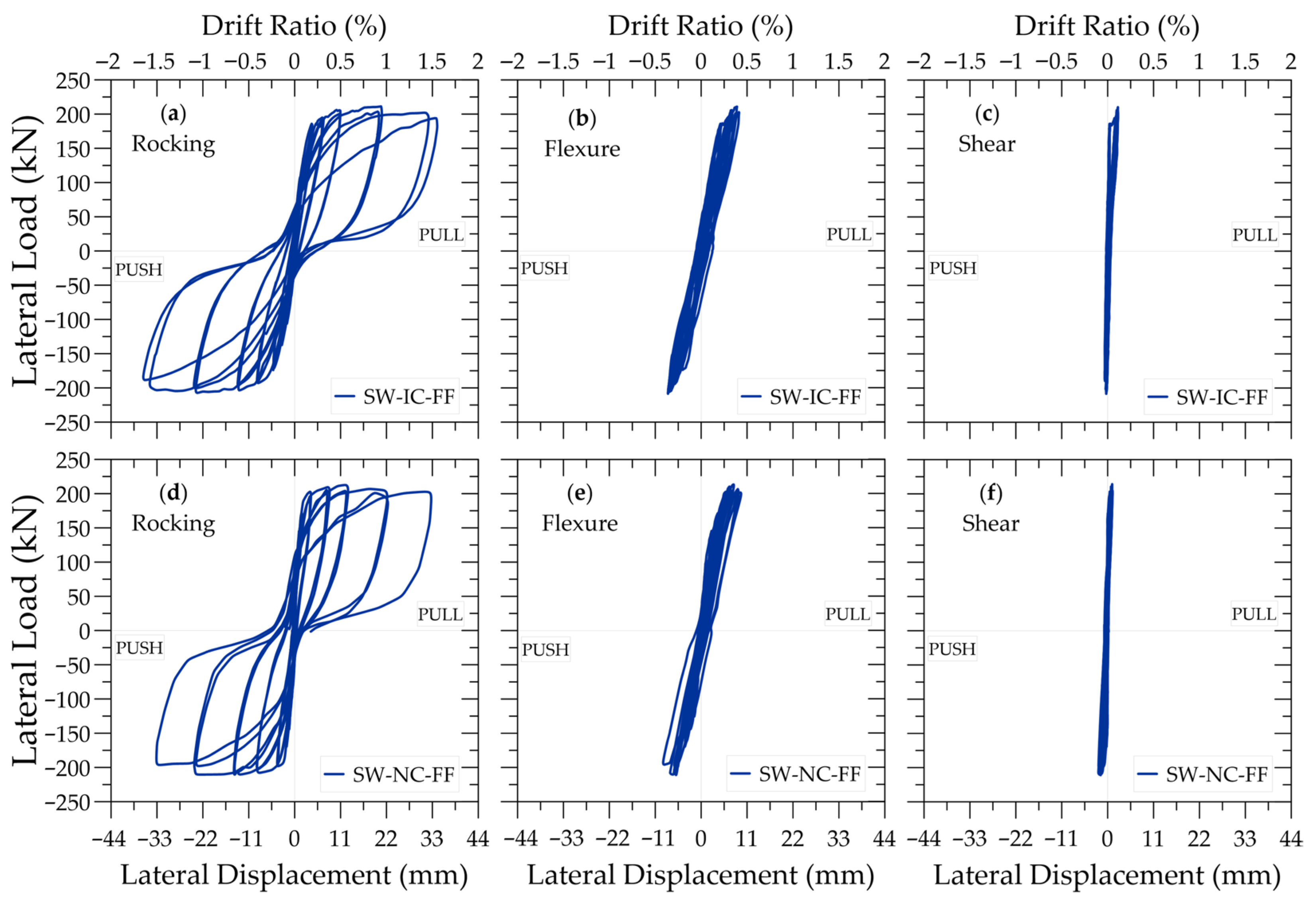

- Rocking response was identified as the predominant mechanism governing both the lateral displacements of the walls and their overall behavior. This response was primarily attributed to the progressive debonding of plain longitudinal reinforcement, occurring not only in the pedestal but also along the wall height. Large W–P interface crack widths, significant interface rotations, and higher concrete tensile strains recorded by LVDTs compared to the reinforcement strains measured by SGs collectively substantiated this mechanism. The pronounced pinching observed in the hysteresis loops further confirmed the self-centering behavior induced by reinforcement debonding and the associated rocking.

- Failure in both specimens occurred through longitudinal bar buckling accompanied by crushing of the concrete core. Ultimate drift ratios were 2.0% for SW-IC-FF and 1.50% for SW-NC-FF, corresponding to displacement ductility values of 4.0 and 4.3, respectively. The SW-IC-FF specimen, detailed with insufficient boundary transverse reinforcement, exhibited a slightly greater drift capacity. Concrete crushing in each specimen began in the form of toe crushing just above the W–P interface and subsequently propagated upward.

- All three guidelines capture the initial stiffness and yield rotation of the substandard wall specimens with commendable fidelity; however, their predictions of rotation capacity diverge significantly. NZ C5 provides the closest agreement with the experimental results, yet this arises from predicting the same rotation capacity for both specimens, which leads to a distinctly unconservative estimate for specimen SW-NC-FF. ASCE 41 is the only procedure that reflects the slight differences between the specimens, whereas EN 1998-3 remains the most conservative. These findings highlight the need for development of improved assessment procedures that explicitly incorporate the rocking-dominated deformation mechanisms governing walls reinforced with plain longitudinal bars.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Gross cross-sectional area of the wall specimen | |

| ALR | Constant axial compressive load corresponding to 20% of the wall cross-sectional area multiplied by concrete compressive strength |

| Provided boundary transverse reinforcement | |

| Required boundary transverse reinforcement | |

| BB/CCC | Observed failure mode defined by bar buckling (BB) and concrete core crushing (CCC) |

| Tension shift in the bending moment diagram | |

| Width of compression zone | |

| Neutral axis depth | |

| Diameter of longitudinal boundary bar | |

| Original length of the ith diagonal sensor | |

| Modulus of elasticity for concrete | |

| Modulus of elasticity of the reinforcing bar | |

| Mean compressive strength of concrete | |

| Maximum tensile stress of reinforcing bar | |

| Probable overstrength of reinforcing bar | |

| Yield stress of reinforcing bar | |

| Ultimate lateral load | |

| Height of the wall at the ith instrumented segment | |

| Wall height | |

| Moment of inertia of the gross concrete section, excluding reinforcement | |

| Coefficient that accounts for the effect of shear span-to-effective depth ratio on deformation capacity | |

| Horizontal distance between the sensors | |

| Plastic hinge length | |

| Linear variable differential transformer | |

| Wall length | |

| Cracking moment of the wall section | |

| Yield moment, defined as the moment when either the reinforcement reaches its yield strain or the concrete reaches a compressive strain of 0.002, whichever occurs first, based on expected material properties | |

| Axial compressive load | |

| Reinforced concrete | |

| Strain gauge | |

| Nominal lateral strength | |

| Overstrength lateral capacity | |

| Probable lateral capacity | |

| SSDR | represents the effective shear span |

| Transverse reinforcement spacing | |

| Wall thickness | |

| Bond stress between concrete and reinforcing steel bar | |

| Nominal shear strength per ACI 318 | |

| Average peak lateral load from tests | |

| Nominal flexural load capacity per ACI 318 | |

| Wall–pedestal interface | |

| Angle between the longitudinal axis of a wall and the diagonal compression strut | |

| ≤1 is a reduction factor accounting for the type of bars (ribbed vs. smooth) and lap-splices, if any | |

| Two-thirds of the height of the ith instrumented segment | |

| Dimensionless parameter reflecting the combined effects of shear span-to-effective depth ratio and axial load on the flexural component of yield deformation | |

| Calculated lateral displacement at the top of the wall section for the ith instrumented segment due to flexural deformation | |

| Calculated horizontal displacement at the actuator level due to slip-induced rocking | |

| Calculated shear displacement at the ith instrumented segment | |

| Yield displacement | |

| Ultimate drift ratio | |

| Drift ratio at the onset of longitudinal boundary reinforcement yielding | |

| Tensile strain at the onset of strain hardening | |

| Tensile strain corresponding to the maximum stress | |

| Tensile strain at rupture stress | |

| Tensile strain in reinforcing steel bar | |

| Nominal ultimate tensile strain of reinforcing steel bar | |

| Tensile strain at yield stress | |

| Longitudinal strain | |

| Rotation of the ith instrumented segment | |

| Basic value of plastic chord rotation capacity of a rectangular wall | |

| Probable inelastic rotation capacity | |

| Rotation at the wall base due to slip-induced rocking | |

| Total rotation capacity | |

| Plastic part of the ultimate chord rotation | |

| Yield rotation | |

| Curvature ductility capacity | |

| Correction factor for an axial force different than zero | |

| Correction factor for concrete strength different than 25 MPa | |

| Correction factor taking into account the confinement of concrete due to transverse bars | |

| Ductility-class factor | |

| Correction factor for asymmetrical reinforcement | |

| Correction factor for a shear span-depth ratio different than 2.5 | |

| Cross-sectional slenderness parameter | |

| Ductility ratio | |

| Ratio of longitudinal boundary reinforcement area to the gross concrete area of each boundary region | |

| Volume ratio of boundary transverse reinforcement to the confined concrete core, measured using outer hoop dimensions | |

| is the reinforcement area | |

| is the reinforcement area | |

| Stress corresponding to 40% of ultimate load | |

| Overstrength factor | |

| Yield curvature |

References

- Park, R.; Paulay, T. Reinforced Concrete Structures; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1975; ISBN 9780471659174. [Google Scholar]

- Paulay, T.; Priestly, M.J.N. Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete and Masonry Buildings; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shiu, K.N.; Daniel, J.I.; Aristizabal-Ochoa, J.D.; Fiorato, A.E.; Corley, W.G. Earthquake Resistant Structural Walls—Tests of Walls with and without Openings; Technical Report; National Science Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1981.

- Oesterle, R.G. Inelastic Analysis for In-Plane Strength of Reinforced Concrete Shear Walls; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lefas, I.D.; Kotsovos, M.D. Strength and Deformation Characteristics of Reinforced Concrete Walls Under Load Reversals. ACI Struct. J. 1990, 87, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefas, I.D.; Kotsovos, M.D.; Ambraseys, N.N. Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Structural Walls: Strength, Deformation Characteristics, and Failure Mechanism. ACI Struct. J. 1990, 87, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilakoutas, K.; Elnashai, A. Cyclic Behavior of RC Cantilever Walls, Part I: Experimental Results. ACI Struct. J. 1995, 92, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnimi, A. Strength and Deformation of Mid-Rise Shear Walls under Load Reversal. Eng. Struct. 2000, 22, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Seismic Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Shear Walls Subjected to High Axial Loading. ACI Struct. J. 2000, 97, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Han, S.W.; Lee, L. Effect of Boundary Element Details on the Seismic Deformation Capacity of Structural Walls. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2002, 31, 1583–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, P.; Meda, A.; Giuriani, E. Cyclic Behaviour of a Full Scale RC Structural Wall. Eng. Struct. 2003, 25, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, J.H.; Wallace, J.W. Displacement-Based Design of Slender Reinforced Concrete Structural Walls—Experimental Verification. J. Struct. Eng. 2004, 130, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Effect of Concrete Strength on the Response of Ductile Shear Walls. Master’s Thesis, McGill Universty, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Su, R.K.L.; Wong, S.M. Seismic Behaviour of Slender Reinforced Concrete Shear Walls under High Axial Load Ratio. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 1957–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazio, A.; Beyer, K.; Bachmann, H. Quasi-Static Cyclic Tests and Plastic Hinge Analysis of RC Structural Walls. Eng. Struct. 2009, 31, 1556–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escolano-Margarit, D.; Klenke, A.; Pujol, S.; Benavent-Climent, A. Failure Mechanism of Reinforced Concrete Structural Walls with and without Confinement. In Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Lisboa, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.A.; Wallace, J.W. Experimental Study of Nonlinear Flexural and Shear Deformations of Reinforced Concrete Structural Walls. In Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Lisboa, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.M.; Lu, X.L.; Duan, Y.F.; Zhu, Y. Experimental Study on Failure Mechanism of RC Walls with Different Boundary Elements under Vertical and Lateral Loads. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2014, 17, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, C.; Hube, M.A.; de la Llera, J.C. Effect of Axial Loads in the Seismic Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Walls with Unconfined Wall Boundaries. Eng. Struct. 2014, 73, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hube, M.A.; Marihuén, A.; de la Llera, J.C.; Stojadinovic, B. Seismic Behavior of Slender Reinforced Concrete Walls. Eng. Struct. 2014, 80, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Hussain, K.; Warnitchai, P. Seismic Evaluation of Flexure–Shear Dominated RC Walls in Moderate Seismic Regions. Mag. Concr. Res. 2015, 67, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Henry, R.S.; Gultom, R.; Ma, Q.T. Cyclic Testing of Reinforced Concrete Walls with Distributed Minimum Vertical Reinforcement. J. Struct. Eng. 2017, 143, 04016225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, E.; Escolano-Margarit, D.; Ramírez-Márquez, A.L.; Pujol, S. Seismic Response of Reinforced Concrete Walls with Lap Splices. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 15, 2079–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandón, C.; Bonett, R. Thin Slender Concrete Rectangular Walls in Moderate Seismic Regions with a Single Reinforcement Layer. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Fang, Z.; Xu, B. Cyclic Behavior of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete Shear Walls with Different Axial-Load Ratios. ACI Struct. J. 2022, 119, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastami, M.; Salehi, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Moghadam, A.S. Performance of Special RC Shear Walls under Lateral Cyclic and Axial Loads. Eng. Struct. 2023, 295, 116813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massone, L.M.; Jara, S.; Rojas, F. Experimental Study on Displacement Capacity of Reinforced Concrete Walls with Varying Cross-Sectional Slenderness. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Valero, E.; Hube, M.A.; Santa María, H. Seismic Performance of Damaged Slender Reinforced Concrete Walls with Unconfined Boundaries. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 101, 111819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCE 41-23; Seismic Evaluation and Retrofit of Existing Buildings. American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2023; ISBN 9780784416112.

- NZ C5:2025; Joint Committee for Seismic Assessment and Retrofit of Existing Buildings (2025) Non-EPB Seismic Assessment Guidelines—Part C5: Concrete Buildings. Version 2A. Design Resilience NZ: Wellington, New Zealand, 2025.

- EN 1998-3:2025; Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance—Part 3: Assessment and Retrofitting of Buildings. BSI Standards Limited: London, UK, 2025; ISBN 9780539229516.

- Gallo, P.Q.; Bonelli, P.; Pampanin, S.; Carr, A. Seismic Design of RC Walls in Chile: Observed Damage and Identified Deficiencies after the 2010 Maule Earthquake; Research Report 2020-01; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C39/C39M-24; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM C469/C469M; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM A370-24; Standard Test Methods and Definitions for Mechanical Testing of Steel Products. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ACI 374.2R-13; Guide for Testing Reinforced Concrete Structural Elements under Slowly Applied Simulated Seismic Loads. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2013.

- Park, R. Ductility Evaluation from Laboratory and Analytical Testing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th world conference on earthquake engineering, Tokyo-Kyoto, Japan, 2–9 August 1988; pp. 605–616. [Google Scholar]

- Massone, L.M.; Wallace, J.W. Load-Deformation Responses of Slender Reinforced Concrete Walls. ACI Struct. J. 2004, 101, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACI 318-19; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781641950565.

- FprEN 1998-1-1:2024; Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance—Part 1-1: General Rules and Seismic Action. BSI Standards Limited: London, UK, 2023.

| Specimen | Horizontal Web Reinf. | Boundary Length Ratio a (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchorage Pattern | Hook Angle | ||||||

| SW-IC-FF | straight | 135° | 20 | 1.54 | 0.39 | 0.57 | 0.63 |

| SW-NC-FF | closed hoop | 90° | 10 | 2.37 | 0.39 | 0.57 | NC |

| Reinf. Bar | (GPa) | (MPa) | (%) | (%) | (MPa) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ϕ8 | 224.8 | 378 | 0.168 | 2.23 | 522 | 16.9 | 37.7 |

| ϕ10 | 216.6 | 340 | 0.157 | 3.97 | 425 | 21.3 | 43.7 |

| ϕ12 | 230.3 | 311 | 0.135 | 3.10 | 414 | 21.0 | 47.0 |

| ϕ14 | 198.6 | 294 | 0.148 | 3.20 | 396 | 21.4 | 41.3 |

| Specimen | ALR (%) | SSDR | (kN) | (kN) | (kN) | (%) | (%) | Governing Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW-IC-FF | 20 | 2.2 | 209.3 | 196.5 | 399.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | BB/CCC |

| SW-NC-FF | 20 | 2.2 | 211 | 199.8 | 399.4 | 0.3 | 1.5 | BB/CCC |

| Specimen | Condition | Flexural Rigidity | Shear Rigidity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. | Pred. | Exp. | Pred. | ||

| SW-IC-FF | Uncracked | ||||

| Cracked | |||||

| SW-NC-FF | Uncracked | ||||

| Cracked | |||||

| Specimen | Conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detailing | ||||||

| SW-IC-FF | ≤10 | and | 0.0196 | |||

| SW-NC-FF | ≤10 | NC | 0.0190 | |||

| Specimen | Conditions | |||||

| SW-IC-FF | ≤10 | ≥0.20 | 0.10 | 1.15 | 0.020 | 0.021 |

| SW-NC-FF | ≤10 | ≥0.20 | 0.019 | 0.019 | ||

| Source of Reference | Type of Bar | Yield Rotation (Rad) | Rotation Capacity (Rad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EN 1998-3:2025 [31] | Deformed | ||

| Plain | |||

| NZ C5:2025 (v2A) [30] | Deformed | ||

| Plain | |||

| ASCE 41:2023 [29] | Deformed | 0.0030 | 0.0190–0.0196 a |

| Experimental | Plain | 0.0030 | 0.0250–0.0300 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Şahinkaya, Y.; Binbir, E.; Orakçal, K.; İlki, A. Behavior of Nonconforming Flexure-Controlled RC Structural Walls Under Reversed Cyclic Lateral Loading. Buildings 2025, 15, 4501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244501

Şahinkaya Y, Binbir E, Orakçal K, İlki A. Behavior of Nonconforming Flexure-Controlled RC Structural Walls Under Reversed Cyclic Lateral Loading. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244501

Chicago/Turabian StyleŞahinkaya, Yusuf, Ergün Binbir, Kutay Orakçal, and Alper İlki. 2025. "Behavior of Nonconforming Flexure-Controlled RC Structural Walls Under Reversed Cyclic Lateral Loading" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244501

APA StyleŞahinkaya, Y., Binbir, E., Orakçal, K., & İlki, A. (2025). Behavior of Nonconforming Flexure-Controlled RC Structural Walls Under Reversed Cyclic Lateral Loading. Buildings, 15(24), 4501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244501