Model Modeling the Spatiotemporal Vitality of a Historic Urban Area: The CatBoost-SHAP Analysis of Built Environment Effects in Kaifeng

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Historic Urban Areas Vitality and Measurement Methods

2.2. Relationship Between Built Environment and Historic Urban Areas Vitality

2.3. Methods for Analyzing Built Environment and Historic Urban Areas Vitality

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Spatial Units

3.2. Research Framework

3.3. Data Sources and Processing

3.4. Research Methods

3.4.1. Vitality Assessment of the Historic Urban Area

- (1)

- Hourly kernel density estimation (KDE): KDE was applied to hourly population heatmap data to generate spatially continuous raster population density surfaces. KDE smoothed heatmap values and reflected the spatial distribution intensity of population activity, serving as the mainstream technical approach for dynamic vitality measurement.

- (2)

- Raster-to-point conversion and spatial association with 100 m grids: To unify the scale of vitality analysis, hourly KDE raster results were converted to point features via raster-to-point operations, with each pixel’s density value stored as an attribute field. The point data were spatially joined with a pre-constructed 100 m × 100 m regular grid, assigning each raster pixel’s density value to its corresponding grid cell. This yielded hourly vitality values for each grid cell within the historic urban area.

- (3)

- Construction of multi-temporal average vitality levels: To reflect the temporal rhythms of daily life, tourism activities, and consumption behaviors in the historic urban area, this study divided the hourly vitality data from 8:00 to 23:00 daily into four typical periods: morning (8:00–12:00), afternoon (13:00–18:00), evening (19:00–23:00), and all-day (8:00–23:00). The vitality value for each spatial unit was then averaged across each time period, as shown in Equation (1):where represented the KDE vitality value for the grid at hour , denoted the average vitality value for the period , and indicated the number of hours within the period.

- (4)

- Weekday and weekend vitality sample processing: After hourly per-grid vitality values were calculated, all grid vitality data from 2 to 8 September 2024 were treated as independent samples for the model. Given that weekday (Monday to Friday) exhibited consistent urban vitality rhythms, while weekends (Saturday and Sunday) shared similar leisure and tourism characteristics, this study separately integrated the grid vitality data from the five weekdays and the two weekend days into two independent sample sets. Specifically, for each typical time period (e.g., 8:00–12:00 in the morning), the sample sizes for weekday and weekend were defined in Equations (2) and (3), respectively.

3.4.2. Measurement of Built Environment Indicators

3.4.3. CatBoost Model

3.4.4. Optuna Hyperparameter Tuning and Model Performance Comparison

3.4.5. SHAP Explainable Method

4. Results

4.1. Dynamic Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of the Historic Urban Area

4.2. The Impacts of the Built Environment on the Vitality of the Historic Urban Area

4.2.1. Feature Importance of Built Environment Factors Across Different Time Periods

4.2.2. Nonlinear Effects of the Built Environment on the Vitality of the Historic Urban Area

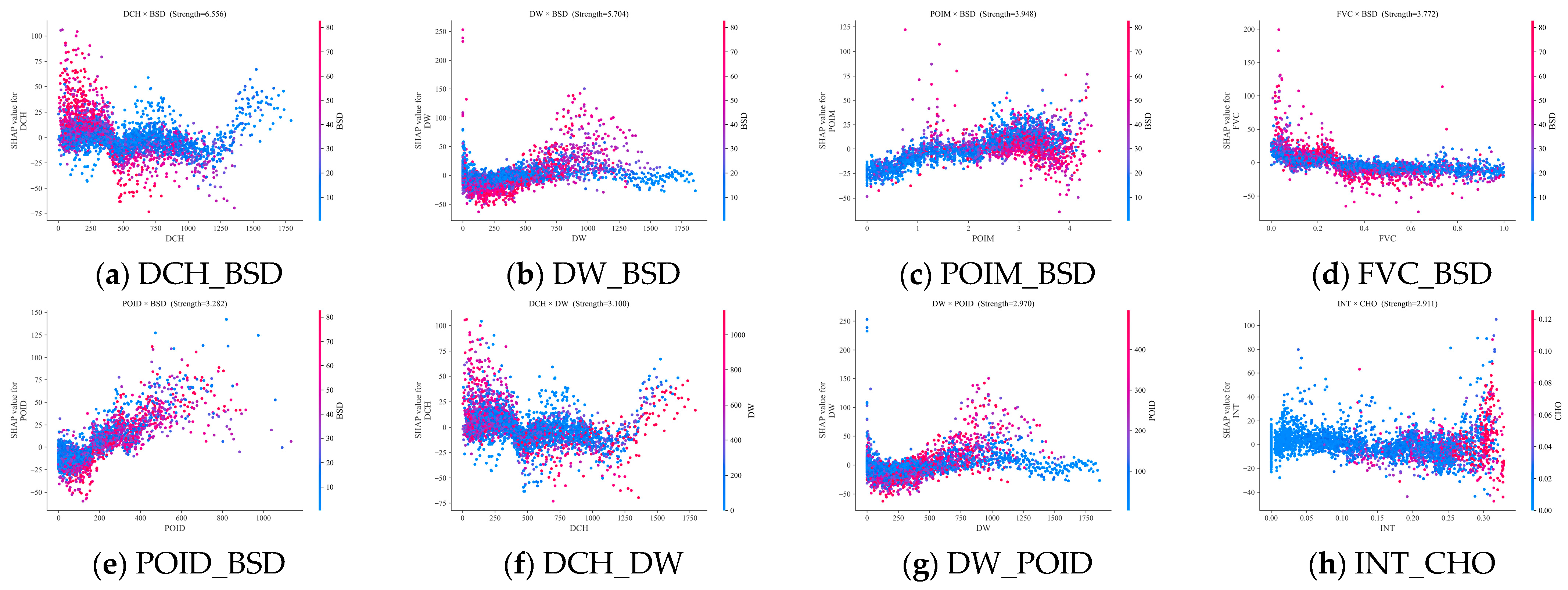

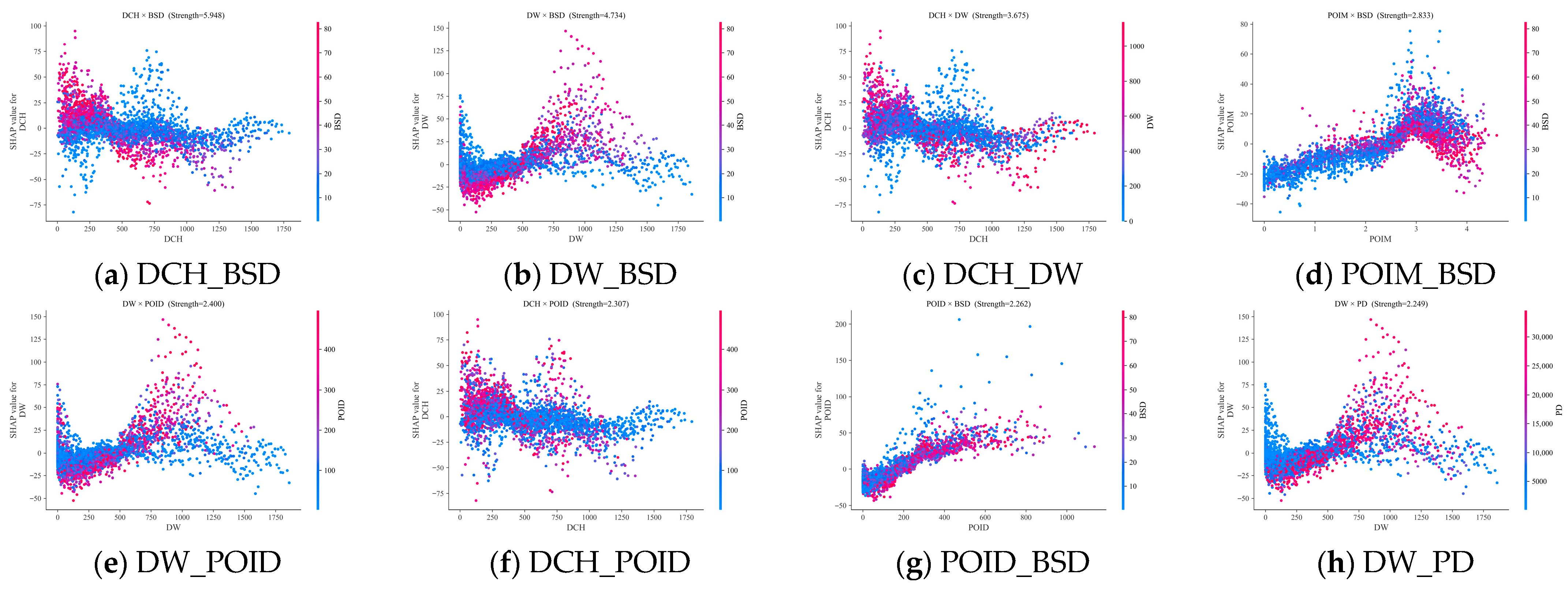

4.2.3. Interaction Effects of the Built Environment on the Vitality of the Historic Urban Area

5. Discussion

5.1. Characteristics of the Vitality of the Historic Urban Area Across Multiple Time Scales

5.1.1. Spatial Patterns of Vitality in the Historic Urban Area

5.1.2. Temporal Dynamics of Vitality in the Historic Urban Area

5.2. Analysis of the Impacts of the Built Environment on the Vitality of the Historic Urban Area

5.2.1. Interpreting the Feature Importance of Built Environment Factors

5.2.2. Interpreting Nonlinear and Threshold Effects of Built Environment Factors

5.2.3. Interpreting the Interactive Mechanisms of Built Environment Factors

5.3. Planning Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Zuo, X.; Han, X. Spatial Quality Optimization Analysis of Streets in Historical Urban Areas Based on Street View Perception and Multisource Data. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Pan, Y. Are cities losing their vitality? Exploring human capital in Chinese cities. Habitat Int. 2020, 96, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Xu, W.; Tan, S.B.; Foster, M.J.; Chen, C. Ghost cities of China: Identifying urban vacancy through social media data. Cities 2019, 94, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Problems and solutions in the protection of historical urban areas. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wang, G. Investigating the Spatiotemporal Pattern between Street Vitality in Historic Cities and Built Environments Using Multisource Data in Chaozhou, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gong, P.; Wang, S.; White, M.; Zhang, B. Machine Learning Modeling of Vitality Characteristics in Historical Preservation Zones with Multi-Source Data. Buildings 2022, 12, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, S. Influencing Factors of Street Vitality in Historic Districts Based on Multisource Data: Evidence from China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Basha, M.S. Urban interventions in historic districts as an approach to upgrade the local communities. HBRC J. 2021, 17, 329–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Wang, X. Will World Cultural Heritage Sites Boost Economic Growth? Evidence from Chinese Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. Dark Age Ahead: Author of the Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. Making a city: Urbanity, vitality and urban design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.-G.; Go, D.-H.; Choi, C.G. Evidence of Jacobs’s street life in the great Seoul city: Identifying the association of physical environment with walking activity on streets. Cities 2013, 35, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Lee, S. Residential built environment and walking activity: Empirical evidence of Jane Jacobs’ urban vitality. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 41, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ta, N.; Song, Y.; Lin, J.; Chai, Y. Urban form breeds neighborhood vibrancy: A case study using a GPS-based activity survey in suburban Beijing. Cities 2018, 74, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunecke, M.G.H.; Mora, R. The layered city: Pedestrian networks in downtown Santiago and their impact on urban vitality. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 336–353. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Lin, Y.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Ren, F.; Wu, C. Exploring the influence of urban form on urban vibrancy in shenzhen based on mobile phone data. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Xing, H. Exploring the relationship between landscape characteristics and urban vibrancy: A case study using morphology and review data. Cities 2019, 95, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ye, X.; Ren, F.; Du, Q. Check-in behaviour and spatio-temporal vibrancy: An exploratory analysis in Shenzhen, China. Cities 2018, 77, 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Huang, Y.; Shi, C.; Yang, X. Exploring the associations between urban form and neighborhood vibrancy: A case study of Chengdu, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Lian, Y. A review of social media-based public opinion analyses: Challenges and recommendations. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Long, Y.; Sun, W.; Lu, Y.; Yang, X.; Tang, J. Evaluating cities’ vitality and identifying ghost cities in China with emerging geographical data. Cities 2017, 63, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhou, M. Urban human activity density spatiotemporal variations and the relationship with geographical factors: An exploratory Baidu heatmaps-based analysis of Wuhan, China. Growth Change 2020, 51, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Tan, X.; Jia, T.; Senousi, A.M.; Huang, J.; Yin, L.; Zhang, F. Nighttime vitality and its relationship to urban diversity: An exploratory analysis in Shenzhen, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 15, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.; Gong, X.; Da, H.; Wen, H. How do population inflow and social infrastructure affect urban vitality? Evidence from 35 large-and medium-sized cities in China. Cities 2020, 100, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Zhu, X. Exploring the relationship between urban vitality and street centrality based on social network review data in Wuhan, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Yeh, A.G.-O.; Zhang, A. Analyzing spatial relationships between urban land use intensity and urban vitality at street block level: A case study of five Chinese megacities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 193, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Wei, M.; Liu, X. Investigating the spatiotemporal dynamics of urban vitality using bicycle-sharing data. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cui, C.; Liu, F.; Wu, Q.; Run, Y.; Han, Z. Multidimensional urban vitality on streets: Spatial patterns and influence factor identification using multisource urban data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, F.; Diao, M.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Ferreira, J.; Ratti, C. Understanding individual mobility patterns from urban sensing data: A mobile phone trace example. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 26, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.H.; He, Y.Q.; Lu, T.; Wang, F.; Huang, Y.J.; Leng, B.R.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.Q. Unveiling urban vitality and its interactions in mountainous cities: A human behaviour perspective on community-level dynamics. Cities 2025, 159, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.T.; Zhao, G.W. Revealing the Spatio-Temporal Heterogeneity of the Association between the Built Environment and Urban Vitality in Shenzhen. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Deng, Y.; Guo, S.D. Association between park vitality and commercial vitality: A case study in Chengdu. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 3127–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.W.; Cao, J.; Zhou, Y.F. Elaborating non-linear associations and synergies of subway access and land uses with urban vitality in Shenzhen. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 144, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.M.; Tang, Y.F.; Zeng, Y.K.; Feng, L.Y.; Wu, Z.G. Sustainable Historic Districts: Vitality Analysis and Optimization Based on Space Syntax. Buildings 2025, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.M.; Zhang, R.X.; Yin, B. The impact of the built-up environment of streets on pedestrian activities in the historical area. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, P. The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P.L.; Handy, S.L. Do changes in neighborhood characteristics lead to changes in travel behavior? A structural equations modeling approach. Transportation 2007, 34, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, F. Developments in urban design practice in Montreal: A morphological perspective. Urban Morphol. 2016, 20, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yeh, A.G.; Xie, J.-Y.; Ma, C.-L.; Li, Q.-Q. Measurements of POI-based mixed use and their relationships with neighbourhood vibrancy. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 658–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Cai, J.; Tu, W. Evaluating and characterizing urban vibrancy using spatial big data: Shanghai as a case study. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, X. How block density and typology affect urban vitality: An exploratory analysis in Shenzhen, China. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Qi, L. Study on the assessment of street vitality and influencing factors in the historic district—A case study of Shichahai historic district. Chin. Landsc. Arch. 2019, 35, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Niu, X. Influence of built environment on urban vitality: Case study of Shanghai using mobile phone location data. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2019, 145, 04019007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Jia, T.; Zhou, L.; Hijazi, I.H. The six dimensions of built environment on urban vitality: Fusion evidence from multi-source data. Cities 2022, 121, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, W.; Wu, J.; Lin, J.; Chu, J.; Xia, C. How can the urban landscape affect urban vitality at the street block level? A case study of 15 metropolises in China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 1245–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C. Research on Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Urban Vitality at Multiple Scales Based on Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Qingdao. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Liu, R.; Cheng, W.; Lei, J.; Ge, J. The Association between Street Built Environment and Street Vitality Based on Quantitative Analysis in Historic Areas: A Case Study of Wuhan, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, B.; Shu, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, R. Exploring the spatiotemporal patterns and correlates of urban vitality: Temporal and spatial heterogeneity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 91, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pan, J. Assessment of influence mechanisms of built environment on street vitality using multisource spatial data: A case study in Qingdao, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangbao, L. Spatial impact of the built environment on street vitality: A case study of the Tianhe District, Guangzhou. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 966562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lo, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q. Nonlinear and synergistic effects of TOD on urban vibrancy: Applying local explanations for gradient boosting decision tree. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Cao, X.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y. Examining pedestrian satisfaction in gated and open communities: An integration of gradient boosting decision trees and impact-asymmetry analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 185, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Xiao, L. Non-linear associations between built environment and active travel for working and shopping: An extreme gradient boosting approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 92, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Li, R.; Wang, A.; Huang, S.; Li, Q.; Qi, H.; Liu, M.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Z. A novel framework for high resolution air quality index prediction with interpretable artificial intelligence and uncertainties estimation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wu, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Yu, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhou, H. Evaluation of CatBoost method for prediction of reference evapotranspiration in humid regions. J. Hydrol. 2019, 574, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Yan, Z. Predicting the short-term electricity demand based on the weather variables using a hybrid CatBoost-PPSO model. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zhang, H.J.; Chen, Y.Q.; Xie, Y.F.; Yin, H.L.; Xu, Z.X. City scale urban flooding risk assessment using multi-source data and machine learning approach. J. Hydrol. 2025, 651, 132626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Lei, Y. Nonlinear associations between urban vitality and built environment factors and threshold effects: A case study of central Guangzhou City. Prog. Geogr. 2023, 42, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Wang, N.; Rao, L. Capturing gender-age thresholds disparities in built environment factors affecting injurious traffic crashes. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 30, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; Tong, Z.; An, R. Nonlinear relationship between urban vitality and the built environment based on multi-source data: A case study of the main urban area of Wuhan City at the weekend. Prog. Geogr. 2023, 42, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lo, S.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. Predicting vibrancy of metro station areas considering spatial relationships through graph convolutional neural networks: The case of Shenzhen, China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 2363–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaomin, T.; Rui, A.; Yaolin, L. Impact of the built environment on residents’ commuting mode choices: A case study of urban village in Wuhan City. Prog. Geogr. 2021, 40, 2048–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.X.; Zheng, X.H.; Chen, Y.B.; Qian, Q.L.; Zheng, Z.H.; Meng, X.X.; Kuang, J.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Yang, N.; Shi, X.H. The Nonlinear Relationship and Synergistic Effects between Built Environment and Urban Vitality at the Neighborhood Scale: A Case Study of Guangzhou’s Central Urban Area. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, A.B.; Ge, Y.Y.; Zhang, S.Y. Spatial Characteristics of Multidimensional Urban Vitality and Its Impact Mechanisms by the Built Environment. Land 2024, 13, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursa, M.B.; Rudnicki, W.R. Feature Selection with the Boruta Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speiser, J.L.; Miller, M.E.; Tooze, J.; Ip, E. A comparison of random forest variable selection methods for classification prediction modeling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 134, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.-M.; Yin, Z.-Y. Flood susceptibility prediction using tree-based machine learning models in the GBA. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J. CatBoost: A new approach for estimating daily reference crop evapotranspiration in arid and semi-arid regions of Northern China. J. Hydrol. 2020, 588, 125087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarkhani, N.; Kazemi, F.; Jankowski, R.; Formisano, A. Dynamic ensemble-learning model for seismic risk assessment of masonry infilled steel structures incorporating soil-foundation-structure interaction. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 267, 111839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Zhang, S. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for Flood Susceptibility Assessment in Seoul: Leveraging Evolutionary and Bayesian AutoML Optimization. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Kadkhodaei, M.H.; Zhou, J. Development of the Optuna-NGBoost-SHAP model for estimating ground settlement during tunnel excavation. Undergr. Space 2025, 24, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanev, R.; Tanev, T.; Efthymiou, V.; Charalambous, C. Modeling of Battery Storage of Photovoltaic Power Plants Using Machine Learning Methods. Energies 2025, 18, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. Explaining a series of models by propagating Shapley values. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Dang, A.R. Creating Engines of Prosperity: Spatiotemporal Patterns and Factors Driving Urban Vitality in 36 Key Chinese Cities. Big Data 2022, 10, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.W.; Xie, C.X.; Zhang, A.P.; Zhao, T.H.; Cao, J.Z. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Urban Vitality and Its Drivers from a Human Mobility Perspective. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Li, X.; Tan, X.; Ma, Z.; Wei, Y. Spatial and Temporal Pattern Characteristics and Influence Mechanisms of Urban Vitality: A Qualitative Empirical Study of Changchun City, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 05025019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Guo, R.; Yang, Y. Exploring the Relationship Between Visual Perception of the Urban Riverfront Core Landscape Area and the Vitality of Riverfront Road: A Case Study of Guangzhou. Land 2024, 13, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cho, N. Nonlinear and interaction effects of multi-dimensional street-level built environment features on urban vitality in Seoul. Cities 2025, 165, 106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qian, Y.S.; Zeng, J.W.; Wei, X.T.; Guang, X.P. The Influence of Strip-City Street Network Structure on Spatial Vitality: Case Studies in Lanzhou, China. Land 2021, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, E. Exploring the Nonlinear Impacts of Built Environment on Urban Vitality from a Spatiotemporal Perspective at the Block Scale in Chongqing. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, S.; Kong, N.; Ke, Y.; Zeng, J.; Chen, J. Nonlinear and Synergistic Effects of Built Environment Indicators on Street Vitality: A Case Study of Humid and Hot Urban Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ye, R.H.; Hong, X.J.; Tao, Y.M.; Li, Z.R. What Factors Revitalize the Street Vitality of Old Cities? A Case Study in Nanjing, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhu, L. Urban vitality transfer: Analysis of 50 factors based on 24-h weekday activity in Nanjing. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 1249–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Yang, Z.; Gui, C.; Li, G.; Xu, H.Y. Investigating the Nonlinear Relationship Between the Built Environment and Urban Vitality Based on Multi-Source Data and Interpretable Machine Learning. Buildings 2025, 15, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.J.; Liu, K.; Feng, J.L. Understanding the impact of modifiable areal unit problem on urban vitality and its built environment factors. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Source | Acquisition Period | Original Spatial Resolution/Type | Preprocessing Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baidu Huiyan Population Location Data | https://huiyan.baidu.com (accessed on 15 September 2024) | 2 September to 8 September 2024 | Approximately 160 m Accuracy/Point Data | Through coordinate projection, hourly data underwent kernel density analysis. The resulting raster was converted to points and spatially aggregated onto a 100 m grid, generating hourly vitality values for each grid cell. |

| POI Data | https://www.91weitu.com (accessed on 3 December 2024) | December 2024 | Point Data | After being deduplicated, cleaned, and reclassified into 17 categories, the data were spatially aggregated onto a 100 m grid to calculate POI density and functional diversity indices. |

| Bus Stop Data | https://www.91weitu.com (accessed on 3 December 2024) | December 2024 | Point Data | After being topologically corrected, the Bus Stop Data were used to perform density analysis. The resulting raster was converted to points and spatially joined to a 100 m grid to obtain bus stop density. |

| Building Data | https://zenodo.org/records/8174931 (accessed on 20 October 2024) | October 2024 | Area Data | After topological cleanup and verification against high-resolution imagery, spatial intersection with a 100 m grid was performed. Building footprint areas within each grid cell were then calculated to derive building density. |

| Road Network Data | https://www.91weitu.com (accessed on 15 October 2024) | October 2024 | Line Data | After topological correction and image-based adjustment, line density and point density analyses were performed on roads and road intersections. The raster results were converted to points and then linked to the 100 m grid to calculate road network density and road intersection density. Spatial syntax metrics were extracted. |

| Water System Data | https://www.91weitu.com (accessed on 3 December 2024) | December 2024 | Area Data | After topographic correction and image-based adjustment, the distance from each grid center point to the nearest water body was calculated. |

| Population Data | https://figshare.com/s/d9dd5f9bb1a7f4fd3734 (accessed on 20 December 2024) | December 2024 | 100 m Accuracy/Raster Data | After reprojection and cropping to the study area, the population raster could be used directly for calculating population density. |

| Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery Data | https://dataspace.copernicus.eu (accessed on 15 October 2024) | October 2024 | 10 m Accuracy/Multispectral Raster | After band 4 (red) and band 8 (near-infrared) were extracted using ENVI 5.6.3 and processed into TIFF format, the data were imported into ArcGIS 10.8.1 to calculate NDVI. FVC was then computed based on a 100 m grid. |

| Historical and Cultural Heritage Data | http://zrzyhghj.kaifeng.gov.cn/kfszrzyhghjwz/cyjzj/pc/content/content_1795302456640720896.html, http://www.gis9.com (accessed on 14 September 2024) | September 2024 | Point Data | Kaifeng’s cultural heritage sites, immovable cultural relics, and historic buildings were integrated. Latitude and longitude coordinates were obtained using Xomap_Excel software (http://www.gis9.com, accessed on 14 September 2024), imported into ArcGIS for coordinate projection, and used to calculate the distance from each grid center point to the nearest cultural heritage site. |

| Dimension | Influencing Factors | Symbol | Variable Explanation | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | ||||

| Density | Building Density (%) | BD | Building Footprint Area per Unit/Total Area per Unit | 1.309 | 1.308 |

| Population Density (persons/km2) | PD | Total Population per Unit/Total Area per Unit | 1.564 | 1.554 | |

| Functional diversity | POI Density (points/km2) | POID | Number of POIs per unit/Total area per unit | 1.803 | 1.803 |

| POI Mix Degree | POIM | POI Information Entropy Within the Unit | 1.871 | 1.876 | |

| Transportation Accessibility | Road Network Density (km/km2) | RND | Road Length Within the Unit/Total Area of the Unit | 3.288 | 3.260 |

| Road Intersection Density (intersections/km2) | RID | Number of road intersections inside the unit/Total area of the unit | 2.424 | 2.421 | |

| Bus Stop Density (stops/km2) | BSD | Number of bus stops within the unit/Total area of the unit | 1.378 | 1.373 | |

| Spatial Accessibility | Integration | INT | Average street integration within the unit | 2.565 | 2.534 |

| Choice | CHO | Street selectivity within the unit | 1.503 | 1.490 | |

| Space Environment | Distance to Waterbody (m) | DW | The shortest distance between the unit’s center point to the water body | 1.160 | 1.160 |

| Fractional Vegetation Cover (%) | FVC | Average Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) within the unit | 1.166 | 1.162 | |

| History and Culture | Distance to Cultural Heritage Site (m) | DCH | The shortest distance from the unit’s center point to the historical and cultural heritage site | 1.184 | 1.177 |

| Period | Model | R2 | RMSE | MAE | Best Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default | Optuna-Tuned | Default | Optuna-Tuned | Default | Optuna-Tuned | |||

| Weekday | Random Forest | 0.9465 | 0.9476 | 29.543 | 29.237 | 17.272 | 17.135 | n_estimators = 823, max_depth = 30, min_samples_split = 2, min_samples_leaf = 1, max_features = sqrt |

| XGBoost | 0.9332 | 0.9487 | 33.002 | 28.912 | 21.735 | 16.701 | n_estimators = 771, max_depth = 8, learning_rate = 0.08, subsample = 0.992, colsample_bytree = 0.924, reg_lambda = 5.644, reg_alpha = 1.427 | |

| CatBoost | 0.8956 | 0.9488 | 41.245 | 28.885 | 28.6251 | 16.674 | Iterations = 797, learning_rate = 0.225, depth = 8, l2_leaf_reg = 3.299, random_strength = 1.621, bagging_temperature = 0.639, border_count = 183 | |

| Weekend | Random Forest | 0.8466 | 0.8561 | 36.635 | 35.485 | 23.429 | 22.761 | n_estimators = 562, max_depth = 27, min_samples_split = 2, min_samples_leaf = 1, max_features = log2 |

| XGBoost | 0.8626 | 0.8893 | 34.668 | 31.125 | 22.343 | 18.926 | n_estimators = 1245, max_depth = 9, learning_rate = 0.027, subsample = 0.62, colsample_bytree = 0.911, reg_lambda = 9.251, reg_alpha = 0.512 | |

| CatBoost | 0.831 | 0.8916 | 38.449 | 30.788 | 27.076 | 18.368 | Iterations = 1829, learning_rate = 0.088, depth = 9, l2_leaf_reg = 8.898, random_strength = 1.537, bagging_temperature = 0.275, border_count = 154 | |

| Dimension | Influencing Factors | Weekday | Weekend | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning | Afternoon | Evening | All Day | Morning | Afternoon | Evening | All Day | ||

| Density | BD | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| PD | 9 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Functional diversity | POID | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| POIM | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| Transportation Accessibility | RND | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| RID | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| BSD | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Spatial Accessibility | INT | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| CHO | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | |

| Space Environment | DW | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| FVC | 6 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| History and Culture | DCH | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Shen, Y. Model Modeling the Spatiotemporal Vitality of a Historic Urban Area: The CatBoost-SHAP Analysis of Built Environment Effects in Kaifeng. Buildings 2025, 15, 4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244499

Zhang J, Shen Y. Model Modeling the Spatiotemporal Vitality of a Historic Urban Area: The CatBoost-SHAP Analysis of Built Environment Effects in Kaifeng. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244499

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Junfeng, and Yaxin Shen. 2025. "Model Modeling the Spatiotemporal Vitality of a Historic Urban Area: The CatBoost-SHAP Analysis of Built Environment Effects in Kaifeng" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244499

APA StyleZhang, J., & Shen, Y. (2025). Model Modeling the Spatiotemporal Vitality of a Historic Urban Area: The CatBoost-SHAP Analysis of Built Environment Effects in Kaifeng. Buildings, 15(24), 4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244499