Study of Liquefaction Characteristics of Saturated Sand–Rubber Mixture Under Cyclic Torsional Shear Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Methods

2.1. Test Materials

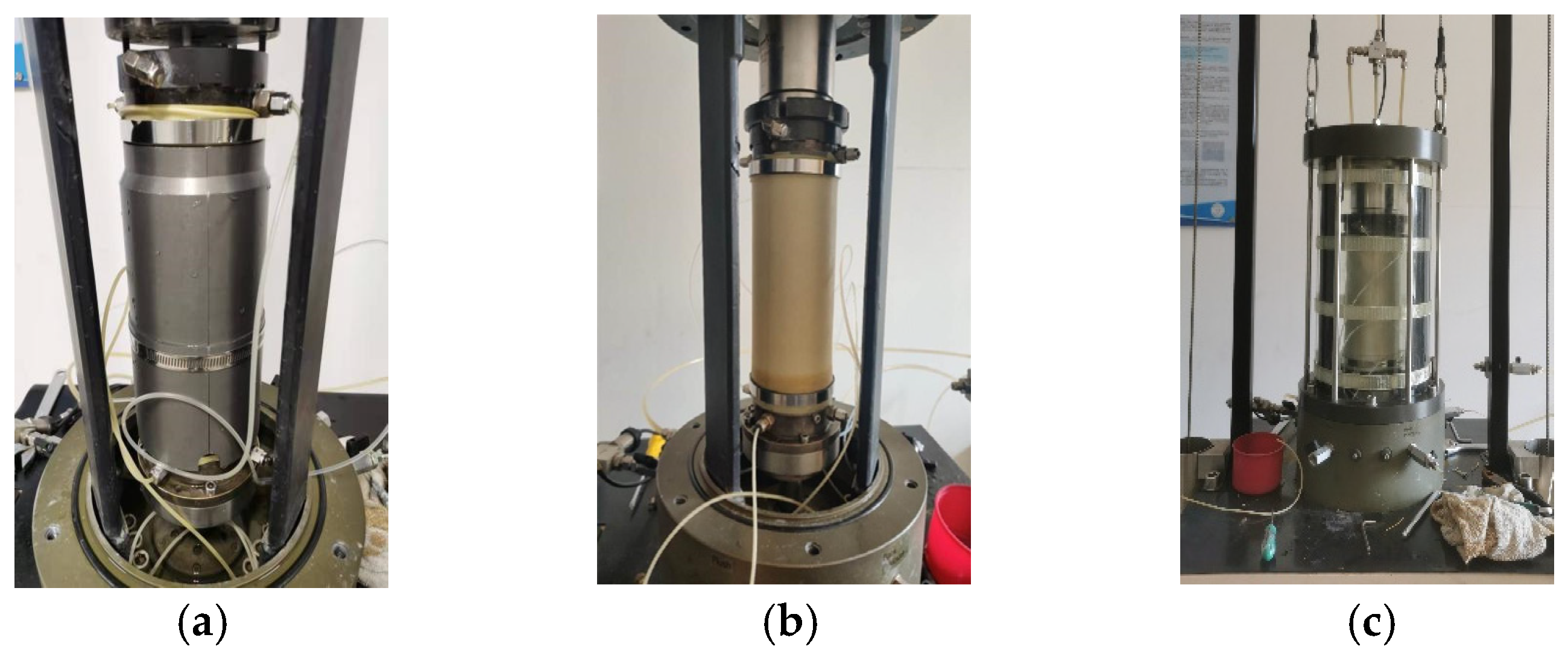

2.2. Test Equipment and Specimen Preparation

2.3. Testing Procedure

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

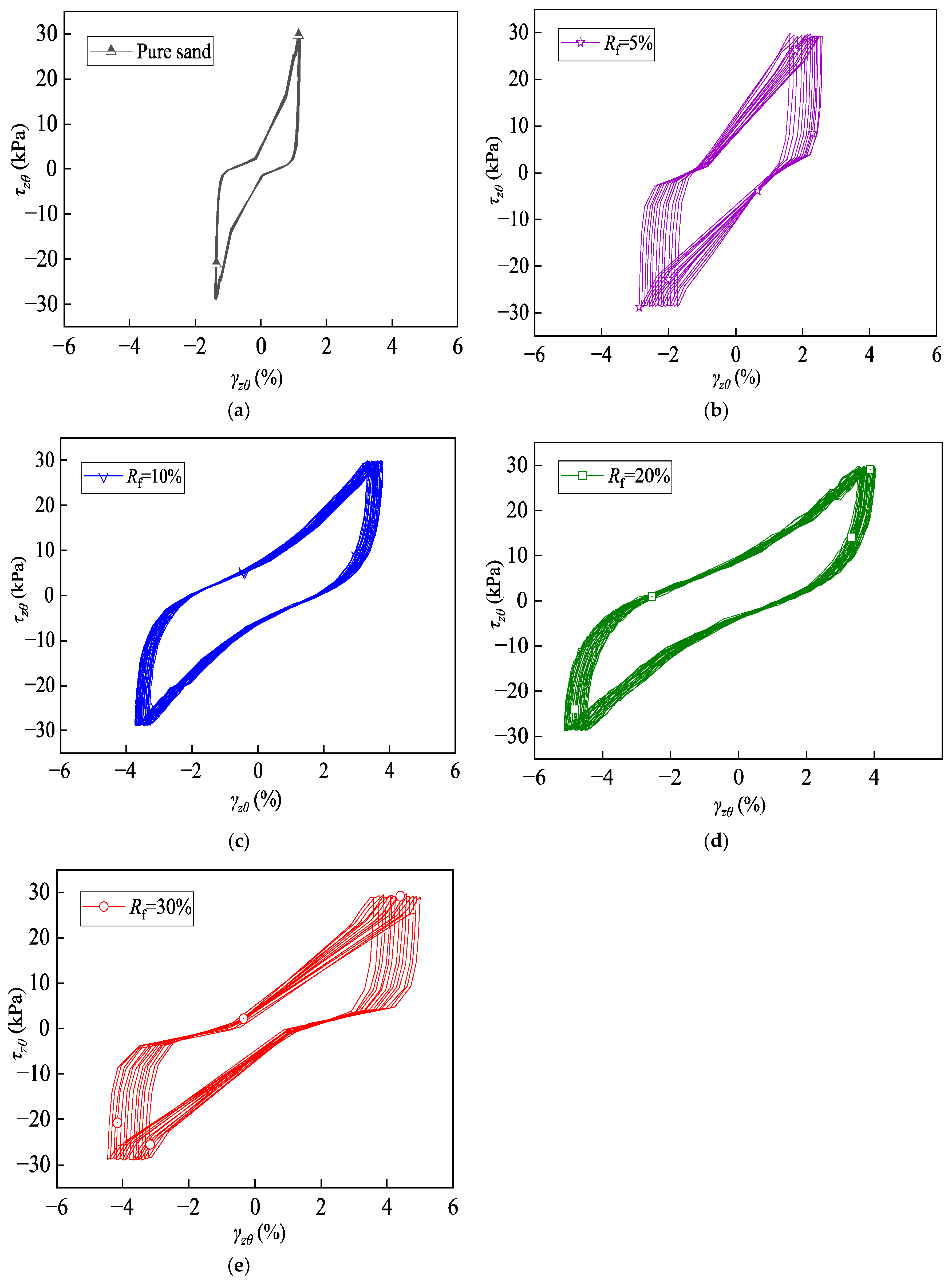

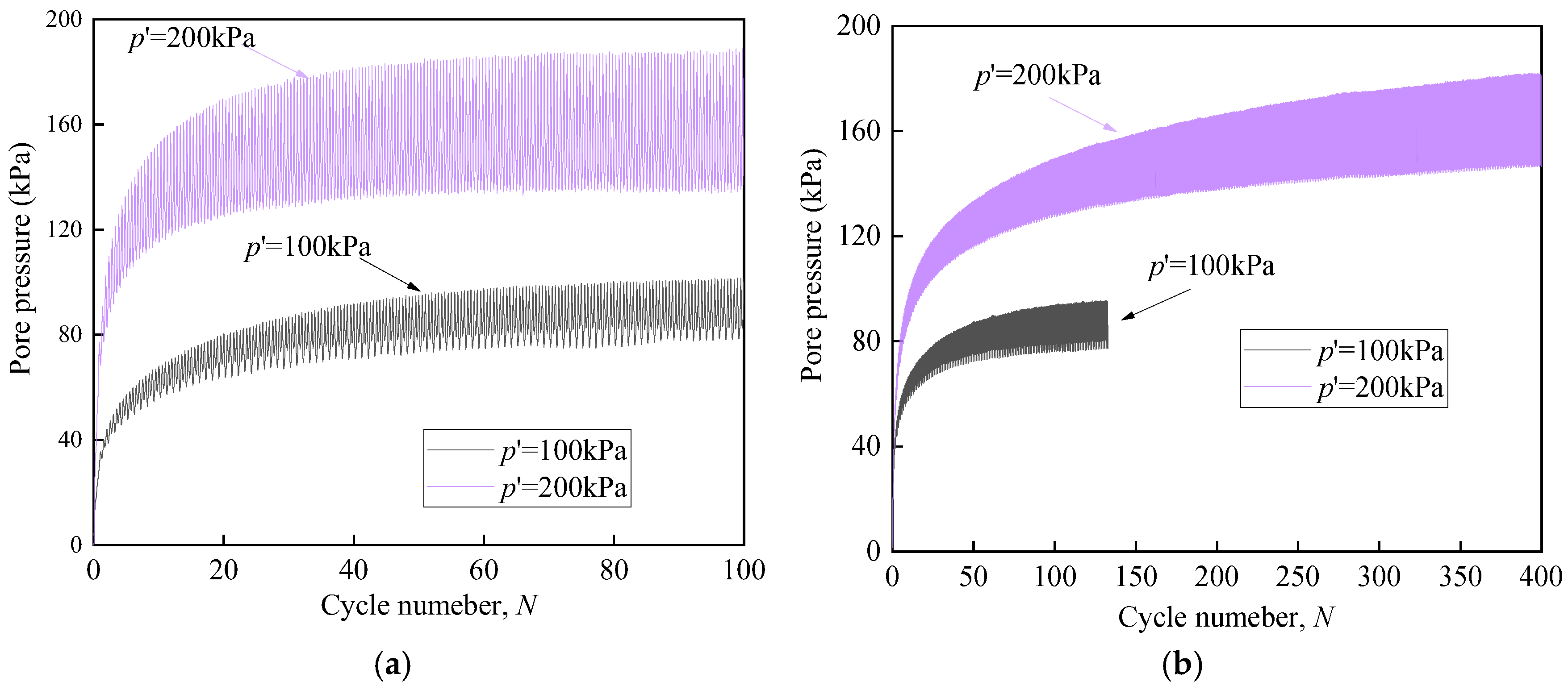

3.1. Liquefaction Response

3.2. Effective Stress Path

3.3. Liquefaction Based on Energy Concept

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaneda, K.; Hazarika, H.; Yamazaki, H. The numerical simulation of earth pressure reduction using tire chips in backfll. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Scrap Tire Derived Geomaterials—Opportunities and Challenges, Yokosuka, Japan, 23–24 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi, W.Y.; Lee, K.M. Mechanical properties of cemented scrap rubber tyre chips. Geotechnique 2011, 61, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalar, A.F.; Karabash, Z.; Mustafa, W.S. Stabilising a clay using tyre bufngs and lime. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2014, 15, 872–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeskar, T. Use of Tyre Shreds in Civil Engineering Applications-Technical and Environmental Properties. Ph.D. Dissertation, Division of Mining and Geotechnical Engineering, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Lulea University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, D.N. Tire derived aggregate as lightweight fill for embankments and retaining walls. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Scrap Tire Derived Geomaterials—Opportunities and Challenges, Yokosuka, Japan, 23–24 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.N.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, G.Y.; Zhang, F.; Mariani, S. Investigation of the microstructure, mechanical properties and thermal degradation kinetics of EPDM under thermo-stress conditions used for joint sealing of floating prefabricated concrete platform of offshore wind power. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 485, 141897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, H.; Edil, T.; Bosscher, P. Engineering Properties of Tire Chips and Soil Mixtures. ASTM Geotech. Test. J. 1994, 17, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, D.; Sandford, T. Tire Chips as Lightweight Subgrade Fill and Retaining Wall Backfill. In Proceedings of Recycling Ahead; US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration: Denver, CO, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Bhowmik, D. Small-Strain Dynamic Behavior of Sand and Sand–Crumb Rubber Mixture for Different Sizes of Crumb Rubber Particle. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmokar, A. Use of scrap tire derived shredded geomaterials in drainage application. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Scrap Tire Derived Geomaterials—Opportunities and Challenges, Yokosuka, Japan, 23–24 March 2007; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zeybek, A.; Eyin, M. Experimental Study on Liquefaction Characteristics of Saturated Sands Mixed with Fly Ash and Tire Crumb Rubber. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, A.; Chiaro, G. Pore Water Pressure Generation and Energy Dissipation Characteristics of Sand–Gravel Mixtures Subjected to Cyclic Loading. Geotechnics 2024, 4, 1282–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhara, K. Recent Japanese experiences on scrapped tires for geotechnical applications. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Scrap Tire Derived Geomaterials—Opportunities and Challenges; Hazarika, H., Yasuhara, K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2007; pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kawata, S.; Hyodo, M.; Orense, P.; Yamada, S.; Hazarika, H. Undrained and drained shear behavior of sand and tire chips composite material. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Scrap Tire Derived Geomaterials—Opportunities and Challenges, Yokosuka, Japan, 23–24 March 2007; pp. 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika, H.; Yasuhara, K.; Kikuchi, Y.; Karmokar, A.K.; Mitarai, Y. Multifaceted potentials of tire derived three dimensional geosynthetics in geotechnical application and their evaluation. Geotext. Geomembr. 2010, 28, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, H.; Pasha, S.M.K.; Ishibashi, I.; Yoshimoto, N. Tire chips reinforced foundation as liquefaction countermeasure for residential buildings. Soils Found. 2020, 60, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H.; Lo, S.H.; Xu, X.; Sheikh, M.N. Seismic isolation for low-to-medium-rise buildings using granulated rubber–soil mixtures: Numerical study. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 41, 2009–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H.; Tran, D.P.; Hung, W.Y.; Pitilakis, K.; Gad, E.F. Performance of geotechnical seismic isolation system using rubber-soil mixtures in centrifuge testing. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 50, 1271–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senetakis, K.; Anastasiadis, A.; Pitilakis, K. Dynamic properties of dry sand/rubber (SRM) and gravel/rubber (GRM) mixtures in a wide range of shearing strain amplitudes. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2012, 33, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitilakis, K.; Karapetrou, S.; Tsagdi, K. Numerical investigation of the seismic response of RC buildings on soil replaced with rubber–sand mixtures. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 79, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitilakis, D.; Anastasiadis, A.; Vratsikidis, A.; Kapouniaris, A. Confguration of a gravel-rubber geotechnical seismic isolation system from laboratory and feld tests. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 178, 108463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Fiamingo, A.; Massimino, M.R. FEM investigation of full-scale tests on DSSI, including gravel-rubber mixtures as geotechnical seismic isolation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 172, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaro, G.; Palermo, A.; Banasiak, L.; Tasalloti, A.; Granello, G.; Hernandez, E. Seismic response of low-rise buildings with ecorubber geotechnical seismic isolation (ERGSI) foundation system: Numerical investigation. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 3797–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vratsikidis, A.; Pitilakis, D. Field testing of gravel-rubber mixtures as geotechnical seismic isolation. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 3905–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.Y.; Sutter, K.G. Dynamic Properties of Granulated Rubber/Sand Mixtures. ASTM Geotech. Test. J. 2000, 23, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamukcu, S.; Akbulut, S. Thermoelastic enhancement of damping of sand using synthetic ground rubber. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2006, 132, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, A.; Senetakis, K.; Pitilakis, K. Small-strain shear modulus and damping ratio of sand-rubber and gravel-rubber mixtures. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2012, 30, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edincliler, A.; Baykal, G.; Saygili, A. Infuence of diferent processing techniques on the mechanical properties of used tires in embankment construction. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edincliler, A.; Yildiz, O. Effects of processing type on shear modulus and damping ratio of waste tire-sand mixtures. Geosynth. Int. 2022, 29, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarayani, P.; Cazacliu, B.; Ibraim, E.; Artoni, R.; Richard, P. Sand Rubber Mixtures under Oedometric Loading: Sand-like vs. Rubber-Like Behavior. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lyu, H.M.; Zhang, R. Water-swelling behavior and self-reinforcing mechanical properties of joint sealing material in underground prefabricated structure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, D.V.; Umu, S.U. Dynamic Properties of Clean sand Modified with Granulated Rubber. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5209494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.H.; Pitilakis, K. Mechanism of geotechnical seismic isolation system: Analytical modeling. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 122, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiavos, A.; Alexander, N.A.; Diambra, A.; Ibraim, E.; Vardanega, P.J.; Gonzalez-Buelga, A.; Sextos, A. A sand-rubber deformable granular layer as a low-cost seismic isolation strategy in developing countries: Experimental investigation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 125, 105731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyodo, M.; Yamada, S.; Orense, R.P.; Okamoto, M.; Hazarika, H. Undrained Cyclic Shear Properties of Tire Chip-Sand Mixtures. In Proceedings of the International Workshop IW-TDGM2007, Yokosuka, Japan, 23–24 March 2007; Taylor and Francis: London, UK; pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, K.; Orense, R.P.; Hyodo, M.; Yoshimoto, N. Seismic Response Characteristics of Saturated Sand Deposits Mixed with Tire Chips. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 139, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiri, M.S.; Vinod, J.S.; Sheikh, M.N. Liquefaction potential and dynamic properties of sand-tyre chip (stch) mixtures. Geotech. Test. J. 2016, 39, 20150031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promputthangkoon, P.; Hyde, A. Compressibility and liquefaction potential of rubber composite soils. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Scrap tire Derived Geomaterials—Opportunities and Challenges, Yokosuka, Japan, 23–24 March 2007; Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK; pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y. Experimental investigation on static and dynamic characteristics of granulated rubber-sand mixtures a new railway subgrade filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarajpoor, S.; Kavand, A.; Zogh, P.; Ghalandarzadeh, A. Dynamic behavior of sand-rubber mixtures based on hollow cylinder tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 251, 118948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, K.; Tatsuoka, F.; Yasuda, S. Undrained deformation and liquefaction of sand under cyclic stresses. Soils Found. 1975, 15, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokusho, T.; Kaneko, Y. Energy evaluation for liquefactioninduced strain of loose sands by harmonic and irregular loading tests. Soil Dyn. Earthquake Eng. 2018, 114, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokusho, T. Energy-based liquefaction evaluation for induced strain and surface settlement–evaluation steps and case studies. Soil Dyn. Earthquake Eng. 2021, 143, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokusho, T.; Tanimoto, S. Energy capacity versus liquefaction strength investigated by cyclic triaxial tests on intact soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2021, 147, 04021006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen | Particle Size Range (mm) | Specific Gravity | Mean Particle Size (mm) | Uniformity Coefficient, Cu | Curvature Coefficient, Cc | Maximum Dry Density (g/cm3) | Minimum Dry Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | 0.075~1.0 | 2.66 | 0.23 | 3.64 | 0.92 | 1.61 | 1.32 |

| Granulated rubber | 2~4 | 1.16 | 3.27 | 1.40 | 1.13 | 0.67 | 0.41 |

| Rf (%) | ρdmin (g·cm−3) | ρdmax (g·cm−3) | ρd (g·cm−3) | Dr | mS (g) | mR (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (pure sand) | 1.32 | 1.61 | 1.51 | 0.7 | 1469.5 | 0 |

| 5 | 1.28 | 1.57 | 1.47 | 0.7 | 1412.3 | 41.4 |

| 10 | 1.26 | 1.54 | 1.45 | 0.7 | 1355.6 | 67.4 |

| 20 | 1.20 | 1.52 | 1.41 | 0.7 | 1241.5 | 138.8 |

| 30 | 1.15 | 1.41 | 1.32 | 0.7 | 1091.7 | 209.3 |

| Rf (%) | p’ (kPa) | Dr (%) | CSR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Pure sand) | 100 | 0.7 | 0.15, 0.2 |

| 5 | 100 | 0.7 | 0.15, 0.2 |

| 10 | 100 | 0.5, 0.7 | 0.15, 0.2 |

| 20 | 100 | 0.5, 0.7 | 0.15, 0.2 |

| 30 | 100, 200 | 0.5, 0.7 | 0.15, 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Study of Liquefaction Characteristics of Saturated Sand–Rubber Mixture Under Cyclic Torsional Shear Loading. Buildings 2025, 15, 4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244486

Zhu X, Li W, Wang Y. Study of Liquefaction Characteristics of Saturated Sand–Rubber Mixture Under Cyclic Torsional Shear Loading. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244486

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Xiaojun, Wenshuai Li, and Yabin Wang. 2025. "Study of Liquefaction Characteristics of Saturated Sand–Rubber Mixture Under Cyclic Torsional Shear Loading" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244486

APA StyleZhu, X., Li, W., & Wang, Y. (2025). Study of Liquefaction Characteristics of Saturated Sand–Rubber Mixture Under Cyclic Torsional Shear Loading. Buildings, 15(24), 4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244486